Abstract

Media bias is an important and underexplored feature of the economics of information. In this article, the author outlines two models that can be used to illustrate media bias in a policy-oriented undergraduate economics or public policy course. The models rely on relatively simple and intuitive underlying assumptions and draw on related empirical research. They do not require extensive mathematical derivations, although the models can easily be extended for more mathematically-inclined students. The models are useful in linking economic theory and empirical research in a context that undergraduate students can relate to and in which they often have direct experience. The models also can be used to motivate a range of discussions on media and competition policy.

One goal of a policy-oriented economics course is to introduce students to the sheer breadth of public policy issues to which economic models and concepts can be applied. There are a plethora of standard examples that feature in most policy-oriented and public policy courses. However, media bias is rarely a feature of such courses. This is in spite of the potential importance of media in information dissemination, framing discussion of public policy issues, and alongside social media, providing one of the main platforms for policy debate. Understanding how media bias may arise using economic theory not only provides students with an additional example of economic theory and models in action but helps them to better understand the contemporary media environment, where public policy is promoted and debated. In this article, I provide key resources and models that can be used to facilitate discussion of media bias in a policy-oriented economics course or public policy course. The details in this article should enable an instructor to motivate and present the key models in under an hour, leaving ample time for extension or further discussion.

The inclusion of content that is highly relevant to students is particularly important in policy courses. Such courses may be compulsory components of degree programs or fulfill general education requirements, in which case the student body in such courses can be incredibly diverse (Cameron and Lim Citation2015). Some students have completed significant and relatively detailed studies of economics in high school, whereas others enter class with no background at all or may have an aversion to or anxiety about studying economics. Students also differ in their aspirations and motivations for studying economics. Some intend a future career in economics or plan to complete an economics major, whereas others are completing the economics course only because it is a compulsory component of their program of study.

Teaching a class comprising students with widely differing backgrounds and motivations is challenging (Cameron and Lim Citation2015). In particular, teaching necessary basic economics concepts and models to students who are already familiar with them through prior study requires an approach that extends their understanding while simultaneously engaging students with no prior experience in economics. To achieve this, in my policy-oriented introductory microeconomics class, I explicitly link concepts and theories to the work of past winners of the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences and the John Bates Clark medal. This approach has the advantage of demonstrating to students the importance and relevance of the concepts and models they are learning and how they relate to the most important work in economics. Thus, my class includes substantive topics on public choice theory (referencing the work of Arrow and Buchanan), the economics of information (referencing the work of Spence and Stiglitz), the economics of education (referencing the work of Becker and Heckman), and the economics of social security (referencing the work of Friedman, Tobin, and Sen). All topics have consideration of substantive policy issues embedded, associated readings from mainstream media, economics blogs, and/or peer-reviewed research, and all topics lead to meaningful (albeit short) writing assignments.

As far as I am aware, no undergraduate economics textbook covers media bias in any detail. Thus, there are no extant graphical models available for instructors to use in teaching this material. However, Mullainathan and Shleifer (Citation2005) outline a theoretical model of media bias that provides the foundation for the models I describe in this article, which can be used to introduce the topic of media bias to students, leading to potentially fruitful discussions of the policy implications of media bias.

Specifically, I describe two models that illustrate how the economist’s toolkit can be used to understand how media bias may arise through the “normal” operation of a media market. Both models start with a simple assumption that media consumers prefer to consume media stories that are aligned with their current beliefs. This “confirmation bias” is well-established in the psychology literature (Nickerson Citation1998; Oswald and Grosjean Citation2004). Interestingly, both models are based on earlier models developed by Hotelling (Citation1929, Citation1931) for use in other contexts. Hotelling’s models are frequently used in introductory or intermediate microeconomics courses and are readily understood by students. Their application to this new context represents a novel extension.

The economics literature on media bias

Media bias (or media slant) can be defined as “systematic differences in the mapping from facts to news reports—that is, differences which tend to sway naive readers to the right or left on political issues” (Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Stone Citation2015, 625). Essentially, news media firms, when presenting the same factual information, do so in ways that convey different normative interpretations of the facts (Scheufele and Tewksbury Citation2007). The measurement of media bias can be operationalized as the difference between the average ideological stance (however measured) of the media (when considered either collectively or as individual firms) and the average ideological stance of the voting public, or the news-consuming public.

The investigation of media bias by economists is a relatively recent development. Mullainathan and Shleifer (Citation2005) were the first to outline a theoretical model of media bias that may arise where media firms cater to the preferences of their readers. In their model of two profit-maximizing media firms, the two firms both report biased news to readers who are willing to pay for news that confirms their beliefs. Moreover, the two firms will present news with opposing biases. When there are three or more media firms, the firms segregate the population to a greater extent, leading to greater bias in individual news firms. Gentzkow and Shapiro (Citation2006) extended this model to consider news consumers’ preferences for the accuracy of reporting. Unlike Mullainathan and Shleifer (Citation2005), Gentzkow and Shapiro’s (Citation2006) model leads to less rather than more bias as competition and the number of media firms increases. This is because inaccurate reporting damages news media firms’ reputations, leading them to prefer more accurate (and less biased) reporting in the long run.

In an early empirical contribution, Groseclose and Milyo (Citation2005) computed “ideological scores” for several major media news outlets (newspapers and television) in the United States based on a count of the times that a media outlet cites various think tanks and other policy groups, compared with the number of times those groups are cited by members of Congress (see also Groseclose, Levitt, and Snyder Citation1999). They found a strong liberal bias overall but substantial diversity, with some news outlets far to the left and others more centrist. Gentzkow and Shapiro (Citation2010) took this methodology a step further, using text-based analysis to categorize newspapers based on the similarity of the language they used with the language used by members of Congress. They also showed substantial diversity in the ideological positions of the newspapers. They then used data on newspaper circulation and voting patterns to show that a large proportion of the media bias in newspapers was explained by the underlying bias in voters. They also showed that, after controlling for the newspaper audience, the identity of the newspaper owner did not affect bias. Somewhat in contrast to the theoretical implications of Gentzkow and Shapiro (Citation2006), Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (Citation2014) find that competition drives diversity in ideological viewpoints, increasing the bias of individual media outlets. The motivation for ideological diversity is to reduce competition among media outlets for advertisers and readers. Their analysis was based on data on all U.S. newspapers in the presidential election years from 1872 to 2004.

In sum, the economics literature on media bias demonstrates that bias arises from the normal operation of media markets. For a useful summary highlighting the contributions of Matthew Gentzkow in particular, see Shleifer (Citation2015).

Introducing students to media bias

An important learning objective of my policy-oriented introductory economics class is understanding how economics concepts and theories can be used to understand the discussion of policy issues in mainstream media stories. As part of that goal, I introduce students to the economics of media bias, drawing on the work of the 2014 John Bates Clark Medal winner, Matthew Gentzkow, as described in the previous section. Shleifer (Citation2015) is a very accessible summary that I have assigned as an additional reading in my class, which provides key insights from the empirical literature on media bias (albeit, as can be expected, with a particular focus on the work of Matthew Gentzkow). This content is included in a topic on the economics of information (along with information asymmetry, adverse selection and signaling, and moral hazard).

However, motivating the study of media bias from an economic and policy perspective is relatively straightforward. Students can easily be presented in class with headlines from online news sources with different political biases (e.g., liberal, conservative). If more detail is required in order to suitably motivate the exploration of media bias, examples of such apparent bias abound (e.g., see the collection of essays in Nelson [Citation2020]). Almost any casual comparison of Fox News and MSNBC on major political or economic news stories will reveal a substantial difference in the elements that are emphasized, the tenor of reporting, the experts who are interviewed, and the conclusions of the experts and reporters.

Moreover, in our increasingly concentrated and polarized media landscape (Picard Citation2014; Wilson, Parker, and Feinberg Citation2020), students are frequently confronted with accusations of media bias on social media or in their everyday lives. For instance, President Donald Trump and other Republican politicians have repeatedly accused U.S. mainstream and social media organizations of exhibiting an anti-conservative bias (Bond Citation2020). Moreover, the media have faced accusations of bias from both right-wing and left-wing advocates and industry insiders (Alterman Citation2003; Goldberg Citation2001). The prominence of these claims and counterclaims makes media bias a particularly salient topic for students. In my experience, students have no trouble recognizing the importance of understanding media bias.

Including consideration of media bias within a policy-focused economics or public policy course serves as a useful “touch point” for students, connecting the theory and concepts from class with the real world that they observe around them. That some of the seminal work on this topic was recognized by Matthew Gentzkow’s John Bates Clark Medal in 2014 further illustrates its importance and relevance to students, particularly students of economics.

Two economic models to illustrate media bias

In this section, I describe two economic models that I use to illustrate media bias in my introductory economics class for social science students. As noted previously, both models rely on the assumption of confirmation bias by media consumers. The models also assume that consumers’ preferences for news items can be defined along a single dimension (e.g., liberal or conservative). Higher dimensionality could be considered as an extension of these simple models, but that would entail the loss of the simplicity apparent in the graphical representations of the models that follow.

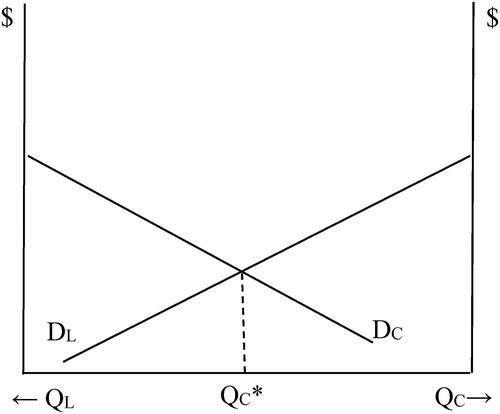

In the first model, we assume that there is a single profit-maximizing firm serving the market for media stories and only two types of content—liberal stories and conservative stories. The firm has limited “space” available for content—this could be interpreted as a limited number of newspaper pages or columns, a limited amount of time within a news program on radio or television, or a limited amount of consumer attention in the case of news Web sites or social media. The quantity of liberal content is QL, the quantity of conservative content is QC, and, for simplicity, we set QL + QC = 1, so that QL and QC represent the proportions of the media content that is devoted to each type. The space for these stories is represented as the x-axis in , where QC is measured from left to right, QL is measured from right to left, and the axis is a width equal to 1.

Next, we assume that the firm must use all of the available space in each time period (or news cycle) and that the costs of news stories of the two types are the same. That ensures that the profit-maximizing firm will maximize profits by maximizing revenue, which also involves maximizing the total benefits for news consumers of their news consumption. The demand curve for conservative news content (DC) represents the marginal benefits that news consumers with conservative news preferences receive from consuming conservative news stories. It is downward-sloping from left to right, representing diminishing marginal utility from consuming additional conservative news stories. Symmetrically, the demand curve for liberal news content (DL) represents the marginal benefit that news consumers with liberal news preferences receive from consuming liberal news stories and is downward-sloping from right to left.

The optimal share of news content of each type is determined by the intersection of the two demand curves (QC* in ). At this point, QC* of the available media space is devoted to conservative content, and 1 − QC* is devoted to liberal content. The optimality of this solution can be established intuitively by reference to the marginal benefit and marginal cost of each type of content. As there are only two types of content, the opportunity cost of an item of one type of content is the marginal benefit forgone from an item of the other type of content. Thus, the demand curve for liberal content is also the marginal cost curve for conservative content. The quantity of conservative content that equates marginal benefit and marginal cost of conservative content is therefore QC*. Symmetrically, the same result holds for liberal content, where the demand curve for conservative content is simultaneously the marginal cost curve for liberal content. It is relatively straightforward to demonstrate this optimality result mathematically, if desired.

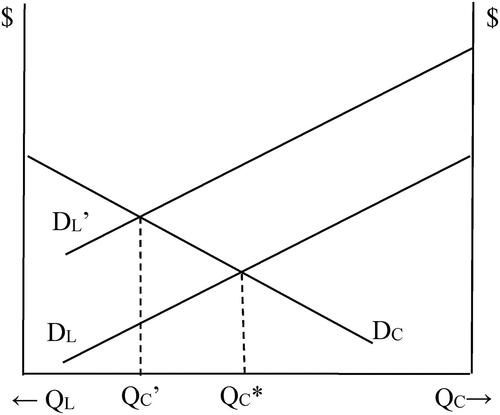

Now consider an alternative market where the number of liberal news consumers exceeds the number of conservative news consumers, such that the demand for liberal content, DL′, is greater than that shown in . This situation is illustrated in . In , the optimal distribution of news content (QC′) lies further to the left. The profit-maximizing media firm responds to greater demand from liberal news consumers by providing more liberal news content. Thus, in this model, news media bias arises through the “normal” operation of the market for news content and is a result of an underlying bias in the distribution of preferences of the news-consuming public.

This first model illustrates key results from the media bias literature, notably Gentzkow and Shapiro’s (Citation2010) finding that demand is much more influential in shaping content than supply. That is, media bias reflects an underlying bias in the news-consuming public more so than reflecting bias in the journalists, editors, or news media owners. This also may help to explain differences in the median political position of media firms across different countries. For example, students who have traveled abroad and/or read international news sites may be able to contrast the positioning of news in a relatively more left-leaning country, such as France, with that in the United States. Note that this model closely resembles Hotelling’s (Citation1931) two-period model of intertemporal exploitation of a nonrenewable resource and can be developed mathematically in a similar fashion, if desired (e.g., see Pindyck and Rubinfeld [Citation2018] for a textbook treatment of Hotelling’s two-period model).

Two obvious limitations of the first model are that it relies on the assumptions that there is a single media-producing firm and that consumers have dichotomous preferences (liberal or conservative). In the second model, we instead assume that consumers’ preferences lie along a continuum from hardcore conservative (C0) to hardcore liberal (L0), as shown in . For simplicity, assume that news consumers are uniformly distributed along the continuum from L0 to C0, but the remainder of the key results are not contingent on this assumption. Each news media firm also locates on the continuum. A particular news media firm’s location on the continuum reflects the mix of stories (liberal or conservative, whether at the extremes or somewhere in between), which, in turn, may be determined by the editorial and ideological preferences of the media firm owners, editorial staff, and journalists (although, see the earlier point on the primacy of demand-side factors in determining the balance of content).

Next, assume that consumers will prefer to consume news stories from a news media firm that is most closely aligned with their preferences and that consumers will consume news stories from a single news media firm. In the model, the consumer will choose to consume news content from the news media firm that is closest to their location, minimizing the straight-line distance along the continuum between the location of the consumer and the location of their preferred news media firm.

This model is, of course, a traditional Hotelling location choice model (Hotelling Citation1929). If there were a single media firm, it could locate anywhere along the continuum, and all news consumers would consume from that media firm. With the additional assumption that there are only two types of news content, the firm’s optimal location would be determined by its share of news stories, as shown in the first model above. However, that assumption is unnecessary here; therefore, the location choice of a single firm is not constrained in that way. When there are two news media firms, the sole Nash equilibrium is for both firms to locate in the center of the continuum (i.e., at X0). If either firm were located away from the center, it would be better off moving slightly closer to the center, capturing more of the total market of news consumers.

In contrast, when there are three news media firms, as shown by Lerner and Singer (Citation1937), there is no pure-strategy Nash equilibrium (see also, Eaton and Lipsey [Citation1975] and Shaked [Citation1982]). If all three firms were located in the center, they would split the market of news consumers equally. However, any of the firms could move a slight amount to the left (or right) along the continuum and capture nearly one-half of the market rather than one-third. Each firm, then, initially has an incentive to move slightly outside the firm that is nearest to the center, thereby capturing more of the market. The model also has no Nash equilibrium for four or more media firms. A useful illustration of this model is to apply a classroom experiment (e.g., Anderson et al. Citation2010).

This second model also illustrates key results from the media bias literature, notably Gentzkow and Shapiro’s (Citation2010) finding that many newspapers exhibit partisan bias but that there are newspapers on both sides of the political spectrum. As noted earlier, Groseclose and Milyo (Citation2005) found similar results for both newspapers and television news, as did Gentzkow, Shapiro, and Sinkinson (Citation2014). This model makes clear that media bias arises in the normal operation of a media market where there are three or more firms because each firm does best by differentiating itself (even if only slightly) from the other firms in terms of their location along the continuum. In other words, individual media firms would appear biased to a neutral observer, with some firms biased toward conservative content and others biased toward liberal content. Still other firms may be more centrist in their content. Students should be able to readily recognize that there are media firms in the local market (alternatively, in the U.S. market) that are located at different points across the continuum, catering to news consumers with different viewpoints. As noted earlier, a casual comparison of Fox News and MSNBC on any particular issue should readily demonstrate this point. Moreover, additional extensions of the Hotelling location model also can be applied (e.g., see Nicholson and Snyder [Citation2010] for a textbook treatment of the Hotelling location model).

Assessing student understanding of the media bias models

There are many options for assessing student learning. In my class, I rely on a mix of short weekly writing assignments and a final examination. The final examination entirely comprises constructed response questions (i.e., no multiple choice), and the weekly writing assignments are designed in part to help students develop the skills necessary to write good constructed-response answers (as well as, obviously, learn the material they have been assigned). The weekly writing assignments are each less than one page in length and cover multiple concepts or models from the week’s content. Each question is linked to a mainstream media article, which provides context for the particular question that is being asked. For example, in 2021, one weekly writing assignment asked:

Read the New Zealand Herald article “A question of balance” (available from the ECONS102 Readings list). What are the three ways the writer identifies as evidence that the New Zealand media is biased against Māori voices? (Hint: This is not the “three levels” discussed on the first page of the article.) What do economic models tell us about the reasons why this bias will arise?

Questions on the final examinations are typically more abstract and involve applying the model to a given context (but without an associated reading, for which there would be insufficient time in the examination). A recent example of a question requiring a short answer is:

Is news media bias likely to increase, or decrease, when there are more media firms? Explain carefully with the aid of an appropriate economic model. (Hint: What happens when there is only one firm? Two firms? Three or more firms?)

Say that an authoritarian government is concerned about news media bias and limits the quantity of one particular type of content that the local news media may distribute. Assuming, for simplicity, that there is only one media firm and two types of content, carefully explain with the aid of an appropriate diagram why this policy will reduce allocative efficiency in the news media market.

Detailed marking schemes or rubrics for the questions described above, and additional examples of suitable questions, are available from me on request.

Conclusion

Media bias is a real-world phenomenon of which almost all students will be aware. Many of them will have seen claims of bias in the mainstream media or on social media. The models outlined in this article demonstrate how economic theory and concepts can be used to illustrate how media bias may arise from the “normal” operation of a media market. In my experience, having taught this topic using these models for more than 10 years, the realization that it is almost natural for some bias to be apparent in media markets leads many students to first examine their normative views of media bias. In some classes, this has led to interesting discussions of how optimal societal outcomes might best be achieved in the presence of persistent media bias. What sorts of policy tools are available to the government, and does applying those tools lead to perverse outcomes? For instance, based on the second model, policies that limit media concentration or encourage the formation of a large number of small media firms would actually lead to more biased media organizations. By connecting students with these real-world questions, we can open students’ eyes to the importance of economic models for understanding important issues that matter to them, encouraging highly motivated and reluctant economics students alike.

Acknowledgments

The models described in this article have developed over the last decade or more of teaching. The author thanks the students and tutors in ECON110 and ECONS102 for their questions and comments, which have helped clarify key aspects of the models over the years. The author is also grateful to Brian Silverstone for comments on an earlier draft of the article and to the associate editor, William Bosshardt, and two anonymous reviewers, whose comments and suggestions improved the clarity and contribution of the article.

References

- Alterman, E. 2003. What liberal media?: The truth about bias and the news. New York: Basic Books.

- Anderson, L. R., B. A. Freeborn, J. Holmes, M. Jeffreys, D. Lass, and J. Soper. 2010. Location, location, location! A classroom demonstration of the Hotelling model. Perspectives on Economic Education Research 6 (1): 48–71.

- Bond, S. 2020. Trump accuses social media of anti-conservative bias after Twitter marks his tweets. National Public Radio, May 27. All things considered. Podcast. https://www.npr.org/2020/05/27/863422722/trump-accuses-social-media-of-anti-conservative-bias-after-twitter-marks-his-twe (accessed December 11, 2020).

- Cameron, M. P., and S. Lim. 2015. Recognising and building on freshman students’ prior knowledge of economics. New Zealand Economic Papers 49 (1): 22–32.

- Eaton, B. C., and R. G. Lipsey. 1975. The principle of minimum differentiation reconsidered: Some new developments in the theory of spatial competition. Review of Economic Studies 42 (1): 27–49.

- Gentzkow, M., and J. M. Shapiro. 2006. Media bias and reputation. Journal of Political Economy 114 (2): 280–316.

- Gentzkow, M. 2010. What drives media slant? Evidence from U.S. daily newspapers. Econometrica 78 (1): 35–71.

- Gentzkow, M., J. M. Shapiro, and M. Sinkinson. 2014. Competition and ideological diversity: Historical evidence from US newspapers. American Economic Review 104 (10): 3073–114.

- Gentzkow, M., J. M. Shapiro, and D. F. Stone. 2015. Media bias in the marketplace. In Handbook of media economics, ed. S. P. Anderson, J. Waldfogel, and D. Strömberg, 623–45. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

- Goldberg, B. 2001. Bias: A CBS insider exposes how the media distort the news. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing.

- Groseclose, T., S. D. Levitt, and J. M. Snyder. 1999. Comparing interest group scores across time and chambers: Adjusted ADA scores for the U.S. Congress. American Political Science Review 93 (1): 33–50.

- Groseclose, T., and J. Milyo. 2005. A measure of media bias. Quarterly Journal of Economics 120 (4): 1191–237.

- Hotelling, H. 1929. Stability in competition. Economic Journal 39 (153): 41–57.

- Hotelling, H. 1931. The economics of exhaustible resources. Journal of Political Economy 39 (2): 137–75.

- Lerner, A., and H. Singer. 1937. Some notes on duopoly and spatial competition. Journal of Political Economy 45 (2): 145–86.

- Mullainathan, S., and A. Shleifer. 2005. The market for news. American Economic Review 95 (4): 1031–53.

- Nelson, M., ed. 2020. The elections of 2020. Charlottesville, VA: University of Virginia Press.

- Nicholson, W., and C. Snyder. 2010. Intermediate microeconomics and its application. 11th ed. Mason, OH: Cengage Learning.

- Nickerson, R. S. 1998. Confirmation bias: A ubiquitous phenomenon in many guises. Review of General Psychology 2 (2): 175–220.

- Oswald, M. E., and S. Grosjean. 2004. Confirmation bias. In Cognitive illusions: A handbook on fallacies and biases in thinking, judgement and memory, ed. R. F. Pohl, 79–96. Hove, UK: Psychology Press.

- Picard, R. G. 2014. Twilight or new dawn of journalism? Evidence from the changing news ecosystem. Digital Journalism 2 (3): 273–83.

- Pindyck, R., and D. Rubinfeld. 2018. Microeconomics. 9th ed. New York: Pearson.

- Scheufele, D. A., and D. Tewksbury. 2007. Framing, agenda setting, and priming: The evolution of three media effects models. Journal of Communication 57 (1): 9–20.

- Shaked, A. 1982. Existence and computation of mixed strategy Nash equilibrium for 3-firms location problem. Journal of Industrial Economics 3 (1–2): 93–97.

- Shleifer, A. 2015. Matthew Gentzkow, winner of the 2014 Clark Medal. Journal of Economic Perspectives 29 (1): 181–92.

- Wilson, A., V. Parker, and M. Feinberg. 2020. Polarization in the contemporary political and media landscape. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences 34 (August): 223–28.