Abstract

Parent’s beliefs about intelligence can influence children’s learning through parenting practices. It is unclear how parents’ perceptions of the child’s ability may affect these processes. This experimental study explored the joint effects of mothers’ growth mindset and perceptions of child competence on their learning involvement. Children (N = 121, 52% female, ages 9–15) completed a set of problem-solving tasks, and mothers were told that their children had either performed well or poorly; or received no feedback. In a subsequent problem-solving task, mothers’ growth mindset positively predicted supportive behaviors, and mothers’ low competence beliefs positively predicted unsupportive and controlling behaviors. No interactions were found. Findings suggest parental growth mindset may help foster positive parenting practices, regardless of their children’s academic competence.

ABUNDANT RESEARCH SUPPORTS the idea that children’s implicit beliefs about intelligence uniquely contribute to their academic success. Endorsement of a growth mindset, the belief that intelligence is malleable, has been shown to predict numerous educational advantages, including greater academic engagement (Dweck, Citation2006), persistence (Good et al., Citation2012), and achievement (Aronson et al., Citation2002; Blackwell et al., Citation2007; Good et al., Citation2003; Yeager & Dweck, Citation2012). Consequently, fostering a growth mindset has become of increasing interest to researchers, educators, and parents alike. For parents, it is often advised that the first step in cultivating a growth mindset in their children is to evaluate and transform their own mindsets (Dweck, Citation2006; Ricci & Lee, Citation2016). However, past literature has failed to detect a direct link between parents’ and children’s mindsets (Gunderson et al., Citation2013, but see also Matthes & Stoeger, Citation2018) and alternatively suggests parents’ beliefs about intelligence socialize children’s mindsets indirectly via parenting practices, such as parental encouragement and involvement (Jose & Bellamy, Citation2012; Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010).

When parents do not practice behaviors reflective of their own growth mindset beliefs, what accounts for this discrepancy? One of the factors impacting this transaction could be parents’ perceptions of their children’s ability. With regard to academic achievement, it is well established in the literature that teacher and parent practices are influenced by their beliefs about the child, which subsequently affect the child’s learning outcomes (Bleeker & Jacobs, Citation2004; Rosenthal & Jacobson, Citation1968; Yeager et al., Citation2022). Additionally, in line with genotype-environment effects theory (Scarr & McCartney, Citation1983), a child’s demonstration of competence in the academic arena may evoke parental behaviors more conducive to the child’s future academic success. Both mindset and perceptions of child ability figure largely in the educational literature, yet despite this, scant research has examined these two prominent topics concurrently. To bridge this gap, this study examined the interplay between parental mindset and perceptions of child ability and its implications for mothers’ involvement in the academic arena.

Mindset theory

Mindset theory has its roots in children’s achievement goal orientations and how these goals impact children’s response to challenge (Dweck & Leggett, Citation1988; Elliot & Dweck, Citation1988). Children with fixed mindsets believe intellectual ability is innate and unchangeable. These children tend to ascribe to performance goals, wherein they aim to showcase their ability through successful performance. Because they do not believe intelligence can be improved, their main motivation when working on an activity is to prove their ability to themselves and to others. They engage readily in easy tasks but shirk difficult ones, as challenge poses the threat of failing and no longer “looking smart” (Mueller & Dweck, Citation1998). On the other hand, children with growth mindsets believe intelligence can be improved through practice and effort and ascribe to mastery or learning goals. Because they are not concerned with appearing smart, they readily embrace challenge as a chance to improve their skills (Dweck, Citation2000). Ample studies, including interventions, provide support for the role of growth mindset in children’s increased engagement, academic achievement, and other educational outcomes (Blackwell et al., Citation2007; Paunesku et al., Citation2015; Wilkins, Citation2014; Yeager et al., Citation2019, but see also Fabert, Citation2014), though it is important to acknowledge the need for further research into potential moderators of mindset training effectiveness, including student achievement level and SES (Miller, Citation2019; Sisk et al., Citation2018; Yeager & Dweck, Citation2020).

Along with intervention efforts aimed at increasing students’ mindsets directly, other researchers have focused their efforts on increasing growth mindset in teachers and parents under the assumption that these belief systems will be passed down to children (Andersen & Nielsen, Citation2016; Rowe & Leech, Citation2019; Seaton, Citation2018). However, research has shown that children do not necessarily adopt the mindsets of their parents (Gunderson et al., Citation2013; Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017). This suggests that this type of indirect mindset transmission may not be so straightforward, and is likely affected by other variables, such as explicit behaviors. Thus, changing the mindsets of children’s social agents may not have the intended effect without consideration of the accompanying behaviors in these agents’ practices.

Growth mindset and parenting practices

Regarding the weak correspondence between children’s and parents’ mindsets (Gunderson et al., Citation2013; Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017), emerging evidence supports the notion that, rather than direct mindset transmission, children’s mindsets are nurtured indirectly through parenting practices (Gunderson et al., Citation2013; Kim et al., Citation2017; Pomerantz & Kempner, Citation2013; Schiffrin, et al., Citation2019). As such, some research has examined the subsequent effects of parental mindset on parent behavioral outcomes (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010; Muenks et al., Citation2015; Rowe & Leech, Citation2019; Schleider et al., Citation2016). For example, when mothers were induced to endorse a fixed mindset about their children’s ability, they in turn showed dampened quality of involvement when assisting their children with a problem-solving task (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010). Parents’ endorsement of a fixed mindset may especially affect their controlling parenting behaviors, which can negatively impact their children’s motivation and learning (Grolnick, Citation2002; Matthes & Stoeger, Citation2018). In the learning context, controlling behaviors often consist of parental actions aimed at directing their children’s academic success, such as interfering with their children’s learning activities when they are not needed, instead of allowing children to figure out solutions on their own (Pomerantz et al., Citation2007). Past research indicates that parental self-reported endorsement of a fixed mindset positively predicted performance-oriented and controlling type behaviors with their children (Muenks et al., Citation2015), whereas inducing a growth mindset in parents negatively predicted controlling behaviors (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010). Echoing these findings, Matthes and Stoeger (Citation2018) found that parents’ growth mindsets predicted children’s academic grades, and this relationship was mediated by parental learning-constructive behaviors and less controlling behaviors. In another study, Schiffrin et al. (Citation2019) found that reports of controlling parenting behaviors (i.e., “helicopter parenting”) in fathers, but not mothers, mediated the relationship between parents’ failure mindset endorsement and emerging adults’ fixed mindset endorsement. Failure mindset is similar to a growth mindset, but refers specifically to the notion of failure as conducive to learning as opposed to detrimental to learning (Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017). These studies reveal the importance of understanding the role of parents’ mindsets. However, there is limited research on the dynamic nature of parent–child interactions and the evocative effects children may have on their parents’ perceptions and subsequent parenting behaviors (Bell, Citation1979; Scarr & McCartney, Citation1983). In the learning context, such perceptions may include the parents’ impression of their child’s competence—which can reflect a child-driven effect (e.g., children’s actual competence) in the socialization process.

Parental perceptions of children’s competence

Parents’ perceptions of their children’s ability play a large part in socializing their children’s own perceptions of competence and in their children’s achievement and learning outcomes (Benner & Mistry, Citation2007; Bleeker & Jacobs, Citation2004; Halle et al., Citation1997; Jodl et al., Citation2001). Like growth mindset, parents’ competence perceptions may also implicitly affect their children’s learning outcomes through associated parental behaviors (Englund et al., Citation2004). Past research indicates that children’s academic competence and parents’ perceptions of their children’s competence mutually reinforce one another, and parents’ perceptions of their children’s competence may even be more predictive of their children’s achievement than children’s own competence perceptions (Frome & Eccles, Citation1998; Halle et al., Citation1997). When parents perceive their children to be low in academic competence, this may evoke behaviors that hamper children’s learning, such as increased controlling behaviors, in an effort to help their child succeed. This is consistent with past research on parents’ behavior under conditions of threat, such as evaluative pressure, which have been shown to increase controlling behaviors (Grolnick et al., Citation2007). For parents who are actively involved in their children’s learning, it may be the case that knowledge that their child is not doing well is indeed threatening.

How might perceptions of child ability affect the impact of parental growth mindset? Scant research has examined this question, though there is some support for interactive effects. In a longitudinal study of 9- to 12-year-old children, Pomerantz and Dong (Citation2006) found that mothers’ positive perceptions of their children’s academic competence predicted their children’s increased academic functioning over time, whereas negative perceptions predicted decreased academic functioning over time. This relationship was moderated by mothers’ entity, or fixed, mindset beliefs, such that the relationship only held for mothers with strong entity mindsets. Consequently, children of mothers who perceived them as having low ability in the academic domain and endorsed an entity mindset showed increased depressive symptoms and dampened academic functioning over time. According to Pomerantz and Dong (Citation2006), these findings support the notion that mothers’ entity, or fixed, mindsets, work together with their perceptions of their children’s competence to create a type of self-fulfilling prophecy, affecting the ways in which mothers interact with their children in the learning context. However, it remains unclear whether the associations between mothers’ perceptions of child ability and their mindset about intelligence are indeed channeled through their behaviors. To address this gap, the current study focused on the evocative effects of perceptions of child competence on parental behaviors, and how mindset may interact with this process. As discussed above, parental mindset has been shown to impact parents’ behavior with their children in the learning context (Matthes & Stoeger, Citation2018; Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010; Muenks, et al., Citation2015). Through these interactions, parents’ views of their children’s competence may fluctuate as a result of receiving feedback regarding their children’s progress (e.g., a school report card, grade on a test). Precisely how mindset and perceptions of child competence interact with one another to influence parental behavior is a question that has yet to be investigated.

Overview of the present study

The current study examined the relationship between mothers’ growth mindset, reported parenting practices, and perceptions of child competence on subsequent mother involvement when interacting with her child in a learning context. We chose to focus on mothers with children ages 9––15 because this represents a developmental period in which intrinsic motivation to learn declines as children become more aware of their own abilities and the relationship between effort and ability (Harter, Citation1990; Nicholls, Citation1978), making it an optimal time for growth mindset influence. We also chose to focus on autonomy support and controlling parenting behaviors as outcomes of interest, given the past research on their association with parental mindset (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010; Muenks et al., Citation2015). The current experimental study manipulated mothers’ beliefs about their children’s ability, such that some were led to believe their children performed very well on a problem-solving task, while others were led to believe their children performed poorly. Given the past literature on parental mindset and child involvement (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010; Muenks et al., Citation2015), we expected that mothers’ growth mindset would positively predict learning-supportive behaviors, such as parental involvement and autonomy support, and negatively predict unsupportive/controlling behaviors during a parent–child interaction. We chose to focus on mothers’ growth mindset endorsement as opposed to their fixed mindset endorsement due to the antagonistic nature of fixed mindsets on parent–child learning interactions (Moorman & Pomerantz, Citation2010). Additionally, we were interested in examining positive influences of mindset beliefs on mothers’ behaviors and how these might buffer the negative learning-related impacts of their perceptions of their children’s competence. In line with past findings on parental perceptions of their children’s competence (Englund et al., Citation2004), we also hypothesized that mothers in the low child competence condition would demonstrate fewer learning-supportive involvement and greater controlling behaviors during a parent–child interaction relative to mothers in the high child competence and control conditions. Lastly, we explored possible interactions between mothers’ growth mindset and perceptions of child competence on parental behaviors during the parent–child interaction. In accordance with past findings on parental entity mindsets and children’s competence perceptions on children’s academic outcomes (Pomerantz & Dong Citation2006), we predicted that the relationship between mother growth mindset and autonomy supportive/controlling behavior would be stronger when mothers perceived their children as low in competence compared to when they perceived their children as high in competence or when no competence feedback was given.

Method

Participants

Participants were 121 children (63 females, 58 males) and their mothers recruited from a large public university participant pool in the Southwest region of the United States. Children ranged in age from 9 to 15 (average age = 11.67) and were 34% Latinx/Hispanic, 22% European American, 9% African American, 5% Asian American or Pacific Islander, 24% multiracial, and 6% other. Mothers ranged in age from 29 to 64 (average age = 40.45) and were 38% Latinx/Hispanic, 35% European American, 9% African American, 5% Asian American or Pacific Islander, 7% multiracial, and 7% other. Mothers also varied in their education levels, with over half (55%) reporting an associate’s degree or higher and 45% reporting a high school diploma or less. Mothers were told that the study would involve a single visit to a research laboratory, during which time they and their children would complete brief questionnaires and their child would also complete several problem-solving tasks. An opt-in procedure was used, such that parents must provide consent and children must provide assent. The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of California, Riverside.

Procedure

Upon arriving to the laboratory, the participants were greeted by two researchers and seated in the survey room together. The researcher then distributed a consent form to the mothers and a corresponding assent form to the children. These forms described that the study goal was to “understand how parents’ practices can contribute to children’s learning.” Both mothers and children were informed that the study was completely voluntary and that if they wished to withdraw from it, at any time they were free to do so without consequence. In addition, participants were informed that they would be videotaped at selected time points during the study. The researcher explained that the videos were completely confidential and would be shown for research purposes only. Participants were given the option of consenting to being videotaped or of participating in the study without being videotaped. Of all participants, 19% declined to be videotaped. These participants were compared against participants who agreed to be videotaped but did not significantly differ on any of the variables under study. The video data sample was also slightly reduced by video technical issues, resulting in a final video sample of 76.85% of all participants, with 33, 28, and 32 participants in the high competence, low competence, and control conditions, respectively. After verifying that both mothers and children had completed the consent and assent forms, respectively, the researcher reiterated the study procedure and answered any questions. Another researcher then led the children to the observation room to complete the first set of Raven’s progressive matrices on their own, while the mothers remained in the survey room. The first Raven’s set contained 10 problems, each of which consisted of a series of pictures with one missing piece and 8 choices, one of which corresponded to the overall pattern. Items were of varying difficulty levels, ranging from easy to challenging. Children were given 15 minutes to complete the first Raven’s set.

While the child participants completed the first Raven’s matrices in a separate room, the researcher explained the nature of the Raven’s progressive matrices to the mothers, and informed mothers that the Raven’s “reliably assesses children’s abstract logical reasoning skills, which are key to a variety of the tasks that children are faced with in school as well as later in life.” We included this statement to ensure mothers’ beliefs in the validity of the task as a learning activity. In this way, mothers equate the Raven’s matrices with real-world learning activities they might assist their child with, such as homework, as opposed to viewing the Raven’s matrices as a fun game or puzzle activity. Scoring and performance on the Raven’s task were not emphasized. Mothers were told that after their children had completed the first set of Raven’s matrices, they would be shown some of their work, and their children would then be completing a second set of Raven’s matrices, during which time they could join them. In the meantime, mothers completed the first questionnaire packet.

After mothers had completed the first questionnaire packet and children had completed the first set of Raven’s matrices (see Appendix A for an example item), the researcher returned to the survey room and told mothers their children had just completed the first set of Raven’s and their work had been scored. During this time, the experimental manipulation took place, which manipulated mothers’ perceptions about their children’s competence on the Raven’s task. Participants were randomly assigned to three conditions: high perceived competence, low perceived competence, and control. Mothers in the high perceived competence condition were told “the average score for other children who have been in this study is 70%. As you can see here, your child has scored 90%.” Mothers in the low perceived competence condition were read an identical sentence but were told their children had scored 50%. To illustrate this information visually, the researcher showed mothers a bar graph with percentages along the y axis, a red line indicating the “normed average,” and an arrow indicating their children’s performance (either 90% or 50%). Participants in the control condition were not shown this image and were told “You will have an opportunity to see some of your child’s work later.”

Before reuniting the mother–child dyads, mothers first completed a brief manipulation check questionnaire, which assessed whether mothers’ perceptions of their children’s performance on the Raven’s task were consistent with the manipulation. Then, mothers were led to the observation room to join their children. There, the second set of Raven’s matrices was distributed, and mothers were told that they could help their children “as much or as little” as they wished. Mother–child dyads were given 10 minutes to complete this second set of 15 Raven’s matrices problems. Items in the second set were equivalent to the first set in terms of the difficulty level. After time was up, mothers were led back to the survey room where they completed a second questionnaire packet. Children remained in the observation room and were given 5 minutes to complete a third set of Raven’s matrices on their own. This last set contained 10 problems of lesser difficulty than the previous set so that children could end the study feeling positive about their performance. Upon completion of the last questionnaire and set of Raven’s matrices, the researcher then led the child participants back to the survey room to join their mothers for the debriefing. Mothers were told of the purpose of the study and were informed that any information regarding their children’s performance was in no way reflective of their actual performance on the Raven’s matrices. As compensation for their time, each mother–child dyad received $50.

Measures

Mothers completed two questionnaire packets throughout the duration of the study. The first mother questionnaire packet was administered prior to the experimental manipulation, and the second mother questionnaire was administered after the manipulation. Mothers were also given a brief manipulation check survey that measured how well they thought their child did on the Raven’s matrices, and whether they believed the Raven’s matrices was a valid measure of children’s abstract logical reasoning. Measures of mother–child interactions during completion of the second Raven’s matrices were taken via coding of the videos by trained research assistants.

Survey before competence manipulation

Mindset

Ten items adapted from Dweck’s (Citation2000) literature on implicit theories of intelligence were used to assess beliefs about the malleability of children’s intelligence. Mothers indicated the extent to which they agreed with statements about the nature of intelligence (1 = Not at all true to 5 = Very True). The measure attained acceptable internal consistency, α = .91. Example items include “Children have a certain amount of intelligence, and they can’t do much to change it" (reverse coded) and “Children can learn new things, but they can’t change their basic intelligence” (reverse coded). Two of the 10 items were included by the researchers to emphasize the process of intelligence malleability: “By studying hard, children can change how intelligent they are” and “By working hard to learn new things, children can change their basic intelligence.”

Child academic ability beliefs

To assess mothers’ beliefs about their children’s general academic competence, an 8-item measure adapted from Frome and Eccles (Citation1998) was used. Mothers responded to items regarding their children’s ability in school (1 = Not at all to 5 = Very much, α = .91). Example items include “My daughter is just as smart as other kids her age” and “My daughter has trouble figuring out the answers in school” (reverse coded).

Mothers’ parenting practices

Mothers’ reports of parenting behaviors were assessed using a 48-item measure adapted from Wang et al. (Citation2007) to reflect their practices in the academic domain (Cheung et al., Citation2016). Mothers indicated how often (1 = Never to 5 = Very Often) they engaged in specific behaviors reflecting three indices: general academic involvement, psychological control, and autonomy support. Twenty items captured mothers’ general academic involvement with their children (e.g., “I talk to my daughter about things related to what she is studying in school,” α = .84), 8 items captured autonomy supportive behaviors (e.g., “I allow my daughter to make choices about her studying whenever possible,” α =.82), and 10 items captured mothers’ psychological control (e.g., “When it comes to schoolwork I let my daughter know what I want her to do is the best for her and she shouldn’t question it,” α =.83).

Measures after competence perception manipulation

Manipulation check

Six items captured mothers’ beliefs about the Raven’s Progressive Matrices task they worked on with their children. These items were designed to gauge the efficacy of the competence manipulation. Mothers reported on their perceptions of their child’s competence at the Raven’s matrices (4 items, α = .77), and trust of the Raven’s as a valid measure (2 items, α = .86). Mothers indicated the extent to which they agreed with each statement, 1 = Not at all true to 5 = Very true. Example items include “My daughter will do pretty well on the problems” (perceived competence), and “The Raven’s Progressive Matrices are a good assessment of children’s abstract logical reasoning skills” (measurement trust).

Coding of mother behavior

Mothers’ behavior during the 10-minute interaction with their children was coded by a team of four trained research assistants. The interaction videos were coded in 30-second intervals for a total of 20 time-points per interaction. During each time-point, the research assistants coded mothers’ behavior as either 1 = present or 0 = absent on a variety of dimensions using a coding system adapted by Grolnick et al. (Citation2002, Citation2007). Scores for each dimension constituted the average of the presence of behaviors across the 20 coded segments during the 10-minute dyadic interaction. All four coders worked together during the training phase, coding several of the same videos and comparing discrepancies in codes until they reached 80% agreement. Thereafter, the coders divided the task and worked in pairs. Each pair of coders independently coded their assigned videos, compared codes, and consolidated any discrepancies. A total of 14 discrete behaviors were observed and coded.Footnote1 Due to low frequencies of many behaviors, these coded behaviors were subsequently collapsed and reduced to two higher-order categories of behaviors: supportive parental behaviors and unsupportive/controlling parental behaviors. Supportive behaviors included instances of mothers’ general provision of instructions (e.g., mother points to the pattern and explains it), provision of other information or asking questions (e.g., mother discusses strategies, hints, asks questions in the context of allowing the child to take the initiative), and by instances of mothers’ being available for the child (e.g., mother sits patiently observing child). Unsupportive/controlling behaviors were indexed by instances of intrusive behaviors (e.g., mother tells child the answer without being requested), leading the child during the activity (e.g., mother tells child what to do), and taking over the task (e.g., mother takes the worksheet and begins working on the activity alone). Appendix B presents the coding system for the six coded behaviors included in the analyses. Reliability for the coded behaviors was calculated with Cohen’s kappa. Because of the large number of coded units (over 28,000 segments), reliability was assessed based on 30 randomly selected cases, representing 33.33% of all coded segments. All coded behaviors included in the analysis had excellent reliability, κ’s = 0.97–1.00.

Demographics

Mothers completed several demographics measures in the second questionnaire packet. These included measures of mothers’ age, education level (1 = Professional degree to 6 = Less than a high school diploma), race/ethnicity, and gross annual household income. Gross annual household income was assessed on a scale of 1–10 in increments of $10,000 for the two lowest values (1 = $0–9,999, 2 = $10,000–19,000) and in increments of $20,000 for all higher values (3 = $20,000–39,000, 4 = $40,000–59,000 to 10 = $160,000 and above).

Results

Overview of analyses

A series of analyses were performed to examine the associations of mothers’ growth mindset and parenting behaviors and the interplay of mothers’ growth mindset and perceptions of competence on their involvement. First, we examined correlations between mothers’ growth mindset and self-reported parental involvement, autonomy support, and psychological control prior to the experimental manipulation. Second, a randomization check was conducted to determine the fidelity of the random assignment of participants across the three conditions, followed by a manipulation check, which was conducted to ensure the experimental manipulation of mothers’ perceptions about their children’s competence was successful. Finally, regression analyses were conducted to examine the direct and interaction effects of mothers’ growth mindsets and perceptions of their children’s competence on parenting behaviors when working with their child on the problem-solving task.

Growth mindset and reported parenting practices

Correlation analyses were conducted to gauge the associations between growth mindset and preexisting parental practices. Descriptive statistics for these pre-manipulation self-reported behaviors are shown in . Consistent with hypotheses, mothers with heightened growth mindset reported more involvement in their children’s learning (r = .36, p < .001). However, mothers’ growth mindset was not significantly associated with self-reported autonomy support (r = .06, p = .534) nor psychological control (r = −.02, p = .833).

Table 1. Correlations and descriptive statistics for mothers’ growth mindset and reported behaviors and beliefs prior to the manipulation.

Randomization check

Next, one-way ANOVAs were used to check for differences across groups on a variety of pre-manipulation measures, including child gender, performance on the first Raven’s task, mothers’ education, gross annual household income, beliefs about child’s academic ability, mothers’ growth mindset, and reports of parenting practices (general involvement, autonomy support, and psychological control). Results of the one-way ANOVAs revealed no significant differences across groups for any of these variables (see ). These results indicate that the randomization of participants into the high competence, low competence, and control conditions was effective. Hence, any subsequent differences observed across groups could not be due to any preexisting differences among the participants.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics by condition on pre-manipulation variables.

Manipulation check and test of group differences

To assess the effectiveness of the manipulation, a one-way ANOVA test was conducted to check for group differences in mothers’ self-reports of their perceptions of their children’s competence after the experimental manipulation. Consistent with expectations, results indicated significant between-group differences on perceptions of competence, F(2, 118) = 9.05, p < .001. Post hoc analyses revealed that mothers in the high competence condition believed their children to be higher in ability at the Raven’s matrices compared to those in both the control condition and the low competence condition. The mean trends in the low competence and control conditions indicate that mothers in the low competence condition had lower perceptions of child competence compared to mothers in the control condition, although this difference was not statistically significant. No differences were evident across groups in terms of mothers’ measurement trust. These results indicate that the manipulation of mothers’ beliefs about their children’s competence was successful. Descriptive statistics and group differences for all post-manipulation variables are presented in .Footnote2

Table 3. Descriptive statistics by condition on post-manipulation variables.

The role of mothers’ perceptions of child competence and growth mindset

Regression analyses were conducted to test the main effects of mothers’ growth mindset endorsement and induced perceptions of competence (i.e., condition) on mothers’ behaviors during the parent–child interaction, and to explore possible interactions between these two variables. Results are presented in . All models included mothers’ age, ethnicity, education, and gross annual household income as covariates, as these factors have significant effects on parental practices related to children’s learning (Grolnick et al., Citation1997; Hornby & Blackwell, Citation2018; Toldson & Lemmons, Citation2013). Additionally, children’s performance on the first Raven’s task and mothers’ perceptions of their children’s general academic competence were included as covariates to control for children’s ability and mothers’ preexisting competence perceptions. Regarding mothers’ growth mindset, a significant main effect was found on providing instructions, β = 0.32, p = .010. Mothers who endorsed growth mindset were more likely to provide supportive instructional guidance during the task. Regarding the effects of the competence perceptions manipulation, a significant main effect was found for mothers’ unsupportive/controlling behaviors (i.e., tells answer, β = −0.24, p = .038), and a marginally significant effect was found for mothers’ supportive behaviors (i.e., waits to be needed, β = 0.22, p = .054).Footnote3 Mothers who were led to believe that their children did poorly were more likely to intervene even when assistance was not required. There were no significant effects of growth mindset or condition on mothers’ provision of other information/asking questions, leading the child, or taking over. Notably, although past research has shown interactive effects between growth mindset and perceptions of competence on children’s academic outcomes (Pomerantz & Dong, Citation2006), no significant interaction effects between mothers’ growth mindset and perceptions of child competence on parenting behaviors were found.Footnote4

Table 4. Effects of condition and mothers’ growth mindset on mothers’ behaviors and beliefs.

Discussion

The present study examined the direct and interactive effects of mothers’ growth mindset and perceptions of child competence on mothers’ involvement with their children, in the context of a logical reasoning task in the laboratory. As expected, prior to the experimental manipulation, mothers’ endorsement of growth mindset was positively associated with reports of general involvement. However, contrary to expectations, there was no association between mothers’ growth mindset and reports of autonomy support or psychological control. After the experimental manipulation, main effects of mindset and competence perceptions were found. Specifically, regardless of the experimental condition, mothers’ growth mindset was associated with greater supportive parental behaviors (providing instructions) during the problem-solving task. Mothers who believed their children had performed poorly engaged in less supportive behaviors and more intrusive behaviors, such as increased instances of telling their children the answers.

Growth mindset and mothers’ reports of parenting practices

Consistent with past research (Muenks et al., Citation2015), mothers’ growth mindset was positively associated with parental involvement, a substantial indicator of child academic success that is well established in parenting literature (for a review, see Pomerantz & Moorman, Citation2010). This suggests that growth mindset-oriented mothers, who believe that their children’s intelligence can be improved through practice and effort, may see more value in actively participating in their children’s academic lives. In contrast, mothers with fixed mindsets may not fully appreciate the need for involvement in children’s learning because they regard these efforts as irrelevant to improving their children’s ability. Increased involvement in their children’s learning may allow growth mindset mothers more opportunity to model attitudes and behaviors that foster academic achievement and communicate to their children the value of effort and persistence, both tenets of growth mindset endorsement (Dweck, Citation2000).

Growth mindset and perceptions of child competence on parenting behaviors

In evaluating the effects of perceptions of child competence and mothers’ growth mindset, we found that mothers with high growth mindsets displayed higher instances of a key supportive behavior, provision of constructive instructions, in their children’s learning. This finding corresponds to the above association of mothers’ growth mindset and reports of parental involvement. If a parent endorses a growth mindset, it follows that they will likely invest effort in helping their child continue to improve their ability, regardless of the child’s past performance.

As expected, there were main effects of condition (i.e., perceptions of child competence) on controlling behavior. Mothers who believed their children had performed poorly were less likely to wait to be needed and more likely to tell their children the correct answer when not requested to do so compared to mothers who believed their children had performed well. This was expected and aligns with past literature demonstrating the relationship between children’s academic performance and parenting practices (Grolnick et al., Citation2002; Pomerantz & Eaton, Citation2001). As shown in a longitudinal study by Pomerantz and Eaton (Citation2001), mothers of low achieving children engaged in increased intrusive behaviors, which subsequently hampered children’s later achievement. Controlling parental behaviors are related to parents’ threat perceptions and ego involvement (Grolnick et al., Citation2002; Gurland & Grolnick, Citation2005). Although the present study’s intention was not to manipulate these constructs in the mothers, the instrument used to manipulate mothers’ beliefs about their children’s competence and experimental environment may have inadvertently done so. For example, telling mothers their children performed far below the “normed average” of other children may have elicited feelings of worry and uncertainty about their children’s future performance, the mechanisms through which child academic achievement affects controlling parental behavior (Pomerantz & Eaton, Citation2001). Furthermore, mothers’ awareness of their participation in the second problem-solving activity with their children, coupled with the emphasis of the Raven’s as a valid measure of children’s logical reasoning skills, may have intensified situational pressure, such that mothers felt increased personal investment in improving their children’s performance. In this case, the effects would be present across conditions but perhaps stronger in the low competence condition, in which mothers may have felt more pressure to help their child improve their score. Whether it be for their children’s or their own benefit, such controlling parental behaviors are counterproductive to children’s learning.

Notably, although there was a main effect of condition (i.e., competence beliefs manipulation) on controlling behavior, mothers’ growth mindset was not predictive of any controlling behaviors. This result was surprising, given the association between parental fixed mindset and greater controlling behaviors (Grolnick, Citation2002; Matthes & Stoeger, Citation2018). It is well established that controlling parenting practices, such as leading the child or taking over the task, are detrimental to learning because these behaviors do not allow the child the autonomy to work through a problem and solve it on their own (Englund et al., Citation2004; Grolnick, Citation2002). However, it may be the case that parents’ self-reported perceptions of their controlling practices differ from their actual behaviors and intentions. Past research indicates a weak correspondence between parent and observer reports of parenting practices, particularly for controlling behaviors (Hendriks et al., Citation2018), with social desirability often claimed as the culprit. Perhaps for some mothers high in growth mindset, behaviors deemed controlling were simply misapplied attempts at increased parental involvement in their children’s learning, as was found in the parent reported associations with growth mindset.

The present study showed no interaction of mothers’ growth mindset with condition on any of the behaviors. These results suggest that, regardless of the type of feedback parents receive regarding their children’s competence, growth mindset remains important in sustaining parents’ positive behaviors, such as their provision of guidance for children to succeed in the Raven’s task. However, it is important to note that growth mindset may not mitigate the influence of competence perceptions on controlling behaviors. Rather, when perceiving their children as having high competence on the Raven’s task, mothers were less likely to engage in controlling practices such as telling answers, irrespective of their mindset beliefs. The lack of interactive effects between mothers’ growth mindset and competence perceptions may be due to the brevity of the experimental manipulation and mother–child interaction. It is possible that parents’ perceptions about children’s general competence at school, which may be garnered through longer periods of observation and various sources, can alter the ways through which mindset beliefs impact their parenting behaviors. Interestingly, these general competence perceptions were related to mothers’ perceptions of their children’s competence at the Raven’s task (see Supplementary Table 1). General competence perceptions did not differ across conditions and were controlled for in the present analyses. They did not interact with mother endorsement of growth mindset to affect mothers’ behavioral outcomes. Perhaps it is the case that the brief Raven’s activity, though emphasized as relevant to children’s academics, did not elicit the types of parental involvement that would be evoked from a real world parent–child learning interaction (e.g., homework, daily tasks, extracurricular learning). Future research examining how these general competence perceptions may interact with mothers’ growth mindset to affect real world learning interactions, with longitudinal follow-ups, could be informative.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations warrant caution in the interpretation of this study’s results. The first limitation concerns the nature of its experimental design. This study was conducted during a one-time visit to a laboratory. Mothers’ perceptions of their children’s competence were manipulated via feedback and were not representative of children’s actual performance. Although manipulation check measures indicated mothers considered the Raven’s task to be a credible assessment and believed that the information provided to them regarding their children’s performance was true, the effects of their perceptions of their children’s competence were limited to this specific task. As such, the findings do not capture the effects of growth mindset on real life academic experiences of mother–child dyads. Second, it must be acknowledged that the manipulation of perceptions of children’s competence was significantly different only for the high competence condition, and although trending, there was no significant difference in competence perceptions between the low competence and control conditions. This result may be due to the control condition design, which included a total absence of feedback on the Raven’s matrices task. Past research indicates that negative feedback may only modestly decrease perceived competence compared to no feedback at all, and a lack of feedback may actually be detrimental to motivation and self-perceptions because it does not provide information to help individuals verify their abilities and understand how to achieve their goals (Fong et al., Citation2019). Thus, it may be the case that the control condition was not as neutral as intended, and may have unintentionally led mothers to have decreased perceptions of their children’s competence, similar to that of the low competence condition.

Our results also may have been affected by mothers’ growth mindset scores. The average mindset score was quite high (M = 4.09 on a scale of 1–5). Only 10% of participants scored below 3, which would represent a fixed mindset endorsement. This indicates that the mothers in our sample were largely growth-mindset oriented, which corresponds to prior research by Pomerantz and Dong (Citation2006) in which there was also a growth mindset bias among mothers. It is possible the effects of mothers’ growth mindset would have been stronger had our sample contained more variation and more fixed mindset-oriented mothers. Last, it must be acknowledged that rates of controlling behavior displayed by the mothers were low (e.g., M = .05 for leading the child in the low competence condition, which translates to an average of only one instance of leading behavior throughout the interaction). These rates were likely affected by the experimental design in which observations of mothers’ behaviors were drawn from a brief, 10-minute interaction during which mothers were aware of being videotaped. For this reason, it is possible that social desirability bias may have precluded mothers from behaving the way they would have with their child in a more naturalistic, private setting.

Conclusion

This study expands the current body of literature on growth mindset by focusing on parents, who serve as prominent social agents in their children’s lives, and their endorsement of growth mindsets, and by including parental perceptions of their children’s competence, a related variable often overlooked in mindset research. In accordance with past studies, the results indicate that parental growth mindset and perceptions of their children’s competence appear to play independent roles in parental behavior and attitudes conducive to children’s learning. Regardless of their children’s academic circumstances, parental endorsement of a growth mindset may help foster their provision of supportive instructions, but it is important that parents be made aware of how their perceptions of their children’s competence may also affect the extent to which they provide unconstructive assistance in the learning context.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (20.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The 14 coded behaviors included providing instructions, working in parallel, initiating off task behaviors, waiting to be needed, treating the child as expert, providing general feedback, providing information or asking a question, explaining the task at the child’s level, checking the answer at the child’s request, writing the answer at the child’s request, checking the answer when not requested, telling the child the answer, leading the child, and taking over.

2 See Supplementary Materials Tables 1 and 2 for correlations between variables and correlations by condition.

3 All models were estimated with and without covariates. Models without covariates showed similar results as models with covariates. In models without covariates, a significant main effect of mother growth mindset was found for providing instructions, β = 0.24, p = .024, and significant main effects of the competence perceptions manipulation were found for tells answer, β = −0.24, p = .021 and waits to be needed, β = 0.21, p = .043.

4 Post hoc power analysis using G*Power (Erdfelder et al., Citation1996) indicated a range of 72%–99% power for all regression models, with the majority of models (5 of 6) exceeding 90% power. As such, most of the models meet the recommended 80% power level (Cohen, Citation1988).

References

- Andersen, S. C., & Nielsen, H. S. (2016). Reading intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s skills. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113(43), 12111–12113. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1607946113

- Aronson, J., Fried, C. B., & Good, C. (2002). Reducing the effects of stereotype threat on African American college students by shaping theories of intelligence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 38(2), 113–125. https://doi.org/10.1006/jesp.2001.1491

- Bell, R. Q. (1979). Parent, child, and reciprocal influences. American Psychologist, 34(10), 821–826. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.821

- Benner, A. D., & Mistry, R. S. (2007). Congruence of mother and teacher educational expectations and low-income youth’s academic competence. Journal of Educational Psychology, 99(1), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.99.1.140

- Blackwell, L. S., Trzesniewski, K. H., & Dweck, C. S. (2007). Implicit theories of intelligence predict achievement across an adolescent transition: A longitudinal study and an intervention. Child Development, 78(1), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.00995.x

- Bleeker, M. M., & Jacobs, J. E. (2004). Achievement in math and science: Do mothers’ beliefs matter 12 years later? Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.1.97

- Cheung, C. S., Pomerantz, E. M., Wang, M., & Qu, Y. (2016). Controlling and autonomy‐supportive parenting in the United States and China: Beyond children’s reports. Child Development, 87(6), 1992–2007. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312023001129

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavior science (2nd ed.). Erlbaum.

- Durbin, C. E., & Wilson, S. (2012). Convergent validity of and bias in maternal reports of child emotion. Psychological Assessment, 24(3), 647–660. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026607

- Dweck, C. S. (2000). Self-theories: Their role in motivation, personality, and development. Psychology Press.

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House Incorporated.

- Dweck, C. S., & Leggett, E. L. (1988). A social-cognitive approach to motivation and personality. Psychological Review, 95(2), 256–273. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.95.2.256

- Elliot, E. S., & Dweck, C. S. (1988). Goals: An approach to motivation and achievement. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(1), 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.1.5

- Englund, M. M., Luckner, A. E., Whaley, G. J. L., & Egeland, B. (2004). Children’s achievement in early elementary school: Longitudinal effects of parental involvement, expectations, and quality of assistance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 96(4), 723–730. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.96.4.723

- Erdfelder, E., Faul, F., & Buchner, A. (1996). GPOWER: A general power analysis program. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 28(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03203630

- Fabert, N. S. (2014). Growth mindset training to increase women’s self-efficacy in science and engineering: A randomized-controlled trial [Doctoral dissertation]. Arizona State University.

- Fong, C. J., Patall, E. A., Vasquez, A. C., & Stautberg, S. (2019). A meta-analysis of negative feedback on intrinsic motivation. Educational Psychology Review, 31(1), 121–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-018-9446-6

- Frome, P. M., & Eccles, J. S. (1998). Parents’ influence on children’s achievement-related perceptions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 435–452. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.435

- Good, C., Aronson, J., & Inzlicht, M. (2003). Improving adolescents’ standardized test performance: An intervention to reduce the effects of stereotype threat. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 24(6), 645–662. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2003.09.002

- Good, C., Rattan, A., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Why do women opt out? Sense of belonging and women’s representation in mathematics. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 102(4), 700–717. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0026659

- Grolnick, W. S. (2002). The psychology of parental control: How well-meant parenting backfires. Psychology Press.

- Grolnick, W. S., Benjet, C., Kurowski, C. O., & Apostoleris, N. H. (1997). Predictors of parent involvement in children’s schooling. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 538–548. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.538

- Grolnick, W. S., Gurland, S. T., DeCourcey, W., & Jacob, K. (2002). Antecedents and consequences of mothers’ autonomy support: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 38(1), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.38.1.143

- Grolnick, W. S., Price, C. E., Beiswenger, K. L., & Sauck, C. C. (2007). Evaluative pressure in mothers: Effects of situation, maternal, and child characteristics on autonomy supportive versus controlling behavior. Developmental Psychology, 43(4), 991–1002. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.43.4.991

- Gunderson, E. A., Gripshover, S. J., Romero, C., Dweck, C. S., Goldin‐Meadow, S., & Levine, S. C. (2013). Parent praise to 1‐to 3‐year‐olds predicts children’s motivational frameworks 5 years later. Child Development, 84(5), 1526–1541. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12064

- Gurland, S. T., & Grolnick, W. S. (2005). Perceived threat, controlling parenting, and children’s achievement orientations. Motivation and Emotion, 29(2), 103–121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-005-7956-2

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children’s growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

- Halle, T. G., Kurtz-Costes, B., & Mahoney, J. L. (1997). Family influences on school achievement in low-income, African American children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(3), 527–537. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.89.3.527

- Harter, S. (1990). Causes, correlates and the functional role of self-worth: A life-span perspective. In R. J. Sternberg & J. Kolligan (Eds.), Competence considered (pp. 67–97). Yale University Press.

- Hendriks, A. M., Van der Giessen, D., Stams, G. J. J. M., & Overbeek, G. (2018). The association between parent-reported and observed parenting: A multi-level meta-analysis. Psychological Assessment, 30(5), 621–633. https://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000500

- Hornby, G., & Blackwell, I. (2018). Barriers to parental involvement in education: An update. Educational Review, 70(1), 109–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1388612

- Jodl, K. M., Michael, A., Malanchuk, O., Eccles, J. S., & Sameroff, A. (2001). Parents’ roles in shaping early adolescents’ occupational aspirations. Child Development, 72(4), 1247–1265. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8624.00345

- Jose, P. E., & Bellamy, M. A. (2012). Relationships of parents’ theories of intelligence with children’s persistence/learned helplessness: A cross-cultural comparison. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 43(6), 999–1018. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022111421633

- Kim, J. J., Fung, J., Wu, Q., Fang, C., & Lau, A. S. (2017). Parenting variables associated with growth mindset: An examination of three Chinese-heritage samples. Asian American Journal of Psychology, 8(2), 115–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/aap0000064

- Maccoby, E. E. (1994). The role of parents in the socialization of children: An historical overview. In R. D. Parke, P. A. Ornstein, J. J. Rieser, & C. Zahn-Waxler (Eds.), A century of developmental psychology (pp. 589–615). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10155-021

- Matthes, B., & Stoeger, H. (2018). Influence of parents’ implicit theories about ability on parents’ learning-related behaviors, children’s implicit theories, and children’s academic achievement. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 54, 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2018.07.001

- Miller, D. I. (2019). When do growth mindset interventions work? Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 23(11), 910–912. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2019.08.005

- Moorman, E. A., & Pomerantz, E. M. (2010). Ability mindsets influence the quality of mothers’ involvement in children’s learning: An experimental investigation. Developmental Psychology, 46(5), 1354–1362. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0020376

- Mueller, C. M., & Dweck, C. S. (1998). Praise for intelligence can undermine children’s motivation and performance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(1), 33–52. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.1.33

- Muenks, K., Miele, D. B., Ramani, G. B., Stapleton, L. M., & Rowe, M. L. (2015). Parental beliefs about the fixedness of ability. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 41, 78–89. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2015.08.002

- Nicholls, J. G. (1978). The development of the concepts of effort and ability, perception of academic attainment, and the understanding that difficult tasks require more ability. Child Development, 49(3), 800–814. https://doi.org/10.2307/1128250

- Paunesku, D., Walton, G. M., Romero, C., Smith, E. N., Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2015). Mind-set interventions are a scalable treatment for academic underachievement. Psychological Science, 26(6), 784–793. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615571017

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Dong, W. (2006). Effects of mothers’ perceptions of children’s competence: The moderating role of mothers’ theories of competence. Developmental Psychology, 42(5), 950–961. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.5.950

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Eaton, M. M. (2001). Maternal intrusive support in the academic context: Transactional socialization processes. Developmental Psychology, 37(2), 174–186. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.37.2.174

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Kempner, S. G. (2013). Mothers’ daily person and process praise: Implications for children’s theory of intelligence and motivation. Developmental Psychology, 49(11), 2040–2046. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031840

- Pomerantz, E. M., & Moorman, E. A 2010 Parents’ involvement in children’s schooling. In J. Meece and J. Eccles (Eds.), Handbook of research on schools, schooling, and human development (pp. 398–416). New York: Routledge.

- Pomerantz, E. M., Moorman, E. A., & Litwack, S. D. (2007). The how, whom, and why of parents’ involvement in children’s academic lives: More is not always better. Review of Educational Research, 77(3), 373–410. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430305567

- Ricci, M. C., & Lee, M. (2016). Mindsets for parents: Strategies to encourage growth mindsets in kids. Sourcebooks, Inc.

- Rosenthal, R., & Jacobson, L. (1968). Pygmalion in the classroom. The Urban Review, 3(1), 16–20. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02322211

- Rowe, M. L., & Leech, K. A. (2019). A parent intervention with a growth mindset approach improves children’s early gesture and vocabulary development. Developmental Science, 22(4), e12792. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12792

- Scarr, S., & McCartney, K. (1983). How people make their own environments: A theory of genotype→ environment effects. Child Development, 54(2), 424–435. https://doi.org/10.2307/1129703

- Schiffrin, H. H., Yost, J. C., Power, V., Saldanha, E. R., & Sendrick, E. (2019). Examining the relationship between helicopter parenting and emerging adults’ mindsets using the consolidated Helicopter Parenting Scale. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28(5), 1207–1219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01360-5

- Schleider, J. L., Schroder, H. S., Lo, S. L., Fisher, M., Danovitch, J. H., Weisz, J. R., & Moser, J. S. (2016). Parents’ intelligence mindsets relate to child internalizing problems: Moderation through child gender. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3627–3636. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0513-7

- Seaton, F. S. (2018). Empowering teachers to implement a growth mindset. Educational Psychology in Practice, 34(1), 41–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/02667363.2017.1382333

- Sisk, V. F., Burgoyne, A. P., Sun, J., Butler, J. L., & Macnamara, B. N. (2018). To what extent and under which circumstances are growth mind-sets important to academic achievement? Two meta-analyses. Psychological Science, 29(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797617739704

- Toldson, I. A., & Lemmons, B. P. (2013). Social demographics, the school environment, and parenting practices associated with parents’ participation in schools and academic success among Black, Hispanic, and White students. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 23(2), 237–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2013.747407

- Wang, Q., Pomerantz, E. M., & Chen, H. (2007). The role of parents’ control in early adolescents’ psychological functioning: A longitudinal investigation in the United States and China. Child Development, 78(5), 1592–1610. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467‐8624.2007.01085.x

- Wilkins, P. B. (2014). Efficacy of a growth mindset intervention to increase student achievement [Education Dissertations and Projects]. 24. https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/education_etd/24

- Yeager, D. S., Carroll, J. M., Buontempo, J., Cimpian, A., Woody, S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Murray, J., Mhatre, P., Kersting, N., Hulleman, C., Kudym, M., Murphy, M., Duckworth, A. L., Walton, G. M., & Dweck, C. S. (2022). Teacher mindsets help explain where a growth-mindset intervention does and doesn’t work. Psychological Science, 33(1), 18–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/09567976211028984

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2012). Mindsets that promote resilience: When students believe that personal characteristics can be developed. Educational Psychologist, 47(4), 302–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2012.722805

- Yeager, D. S., & Dweck, C. S. (2020). What can be learned from growth mindset controversies? The American Psychologist, 75(9), 1269–1284. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000794

- Yeager, D. S., Hanselman, P., Walton, G. M., Murray, J. S., Crosnoe, R., Muller, C., Tipton, E., Schneider, B., Hulleman, C. S., Hinojosa, C. P., Paunesku, D., Romero, C., Flint, K., Roberts, A., Trott, J., Iachan, R., Buontempo, J., Yang, S. M., Carvalho, C. M., … Dweck, C. S. (2019). A national experiment reveals where a growth mindset improves achievement. Nature, 573(7774), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-019-1466-y

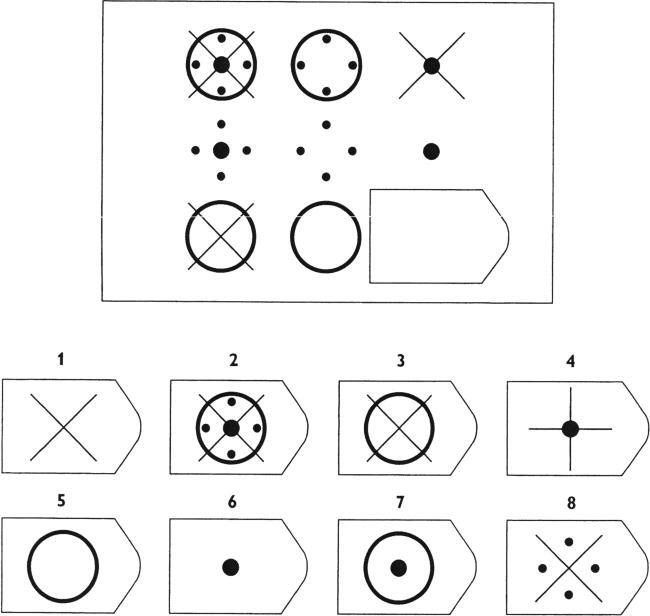

Appendix A

Example Raven’s Progressive Matrices Item

Appendix B

Coding system for mother behaviors