Abstract

This cross-cultural study compared the prosocial behaviors of 101 Dutch, 37 urban Indian and 91 urban Chinese preschoolers, investigated (potential) cultural differences on their mothers’ values and goals, and examined how mothers’ values and goals relate to preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors. Preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors were observed in three standardized, behavioral assessments. Mothers reported on their own values and socialization goals for their children. Results showed no cultural difference in prosocial behaviors. However, Indian and Chinese mothers rated self-enhancement values as more important than Dutch mothers, and Indian mothers rated self-transcendence values and relational goals as more important than the Chinese and Dutch mothers. No difference was found on autonomous goals. These findings suggest that current cultural differences on parental socialization processes are beyond the individualistic-collectivistic dichotomy often used to classify cultures and are more reflective of the independence of these two dimensions. Mothers in urban Indian and urban Chinese societies can be categorized into an autonomous-relatedness cultural model. Additionally, there might be an ongoing shift toward an independence model in the urban, Chinese societies. Furthermore, culture moderated the association between autonomous goals and observed prosocial behaviors, with this association being significant within the Dutch sample only. No other associations between values or goals and children’s prosocial behavior were found. Overall, these findings support the ecocultural model of children’s prosocial development, and further suggest that young preschoolers from different cultures are more alike than different in prosocial behaviors.

Young children exhibit different types of prosocial behaviors (e.g., helping and sharing, for reviews, see Dunfield, Citation2014; Warneken & Tomasello, Citation2009), which can be refined by socialization factors such as parental instruction or the internalization of norms (Warneken, Citation2016). On reaching preschool age, children become particularly receptive to external influences and begin to internalize cultural norms and orientations handed down by agents of socialization (Schuhmacher & Kärtner, Citation2015). One way to examine how children’s prosocial behaviors are shaped through socialization experience is to compare prosocial behaviors in different sociocultural backgrounds, and examine whether culture-specific values or parental socialization goals are related to the children’s prosocial behaviors. Nevertheless, to date only a handful of studies have used standardized behavioral assessments to examine cultural differences in prosocial behaviors (Kärtner, Citation2018). Moreover, in theory, even if children across cultures show similar level of prosocial behaviors, these behaviors may be cultivated by cultural-specific values and socialization processes toward these values through parental goals (e.g., Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Greenfield, Keller, Fuligni, & Maynard, Citation2003; Kärtner, Keller, & Chaudhary, Citation2010; Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013). Thus, the current study aimed to further examine the role of cultural contexts in understanding individual and cultural differences in prosocial behaviors at the young preschool age. In doing so, we first compared preschoolers’ observed prosocial behaviors (using three standardized behavioral assessments: instrumental helping, sharing and empathic helping) across three cultural contexts (Dutch, Indian, and Chinese). We next examined whether and how mothers’ values and goals differ from one culture to another. Finally, we examined whether there are any associations between maternal values/goals, and their children’s prosocial behaviors, for all samples combined and per sample.

Cultural differences in prosocial behaviors – evidence based on the I-C spectrum

Researchers often emphasize the importance of the individualism-collectivism (I-C) spectrum in framing and explaining between-cultural differences in (prosocial) behaviors (Carlo, Roesch, Knight, & Koller, Citation2001). This spectrum places cultures along a continuum, based on the extent to which each culture promotes certain values (de Guzman, Do, & Kok, Citation2014). While individualistic cultures (e.g., Western Europe) tend to place more value on independence and autonomy, collectivistic cultures (e.g., Asian) tend to place more value on interdependence and relatedness (Triandis, Citation2001). Accordingly, children from more collectivistic societies are likely to exhibit prosocial behaviors more often than those from individualistic societies (e.g., Rao & Stewart, Citation1999; Stewart & McBride-Chang, Citation2000; for a review, see Eisenberg, Fabes, & Spinrad, Citation2006). However, the empirical evidence is inconsistent regarding whether cultural differences are already visible at such early ages. Supporting the aforementioned proposal (Rao & Stewart, Citation1999), Indian toddlers showed more instrumental helping than their peers from Germany (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017). Also, 3- and 5-year-olds from collectivistic (e.g., traditional) societies showed less self-interest (more fairness) than their peers in individualistic (e.g., modern) societies in sharing (Rochat et al., Citation2009). However, other researchers found no differences on prosocial behaviors between children from individualistic and collectivistic cultures. For instance, in another study on Indian and German toddlers, similar levels of prosocial responses to others’ emotional distress were noted (Kärtner et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, preschoolers from small-scale rural villages of a non-Western culture (Tanna, Vanuatu) showed similar helping levels as their peers from urban, industrialized cities of a western culture (Boston, United States) (Aime, Broesch, Aknin, & Warneken, Citation2017). In light of these inconsistent findings, the first aim of the current study was to examine whether there are cultural differences in prosocial behaviors.

The inconsistent findings also imply that the over-simplification of classifying societies as either ‘individualistic’ or ‘collectivistic’ may be insufficient in explaining the (potential) cultural influences on prosocial behaviors. Specifically, individualism and collectivism may coexist within cultures, particularly those experiencing rapid changes in urbanization, globalization or technological advancements (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007). In the past 50 years, the chasm between cultures has shrunken, with elements of individualism seeping into some societies that have long been described as collectivistic (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007), such as Indian (Sinha & Tripathi, Citation1994) and Chinese societies (Lu, Citation1998; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007). Nevertheless, the Chinese culture is still recognized as less individualistic than the Indian, and the Indian culture is recognized as less individualistic than the Dutch culture (Insights, Citation2019). In addition, cultural models that go beyond the I-C spectrum may be warranted when speaking to the cultural differences of young children’s prosocial behaviors nowadays. In the current study, we examined the eco-cultural model as an alternative to the I-C spectrum.

The ecocultural model of development

Rather than classifying cultures along a continuum, the ecocultural model of development (e.g., Keller, Citation2007; Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013; Keller et al., Citation2006) consider these dimensions to represent two independent dimensions upon which cultures vary. Drawing from the work of Kağitçibaşi (Citation1996), Keller et al. (Citation2006) derived three cultural models that purportedly should capture most cultures around the world. These models combine the dimensions of interpersonal distance, which consists poles of relatedness and separateness, and dimensions of agency, which consists poles of autonomy and heteronomy (Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Keller et al., Citation2006). More specifically, the independence model prioritizes personal separateness and autonomous, and portrays urban, educated families in industrialized societies. In this model, socialization processes on self-enhancement and self-maximization are emphasized (Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Keller et al., Citation2006). The interdependence model prioritizes personal relatedness and heteronomy, and portrays rural, subsistence-based families in traditionally farming societies. Socialization processes on self-transcendence and group harmony are emphasized (Greenfield et al., Citation2003; Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996). The autonomous-relatedness model prioritizes both personal autonomy and relatedness, and portrays urban, educated families in societies that are traditionally characterized as interdependent (e.g., urban Indian and Chinese families). Socialization processes on both self-enhancement and self-transcendence are emphasized (Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Keller et al., Citation2006; Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007). Although empirical studies confirmed the classification of these three models (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Greenfield et al., Citation2003; Kärtner et al., Citation2010; Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013), a further, nuanced examination on how and which aspects of the socialization processes differ between and within these models are needed (Keller et al., Citation2006). Thus, the second aim of the current study was to examine cultural differences in socialization processes (i.e., mothers’ values and their socialization goals for their children). The Dutch families are likely to be characterized into the independence model, while the urban Indian and urban Chinese families could be characterized into the autonomous-relatedness model (Keller et al., Citation2006).

Parents’ values, goals, and their associations with prosocial behavior

In addition to explaining cultural differences, the ecocultural model also helps in understanding cultural differences in promoting children’s prosocial behavior. Culture refers to a shared system of meaning, which is situated in everyday contexts and behaviors (Greenfield & Keller, Citation2004; Keller, Citation2007), and influence children’s developmental pathways (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Kärtner et al., Citation2010). In addition, the dynamic and adaptive changes in parental values/goals that occur in the process of a cultural shift can lead to changes in children’s developmental outcomes (e.g., Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013; Keller et al., Citation2006). Following this logic, the third aim of the current study was to examine how socialization processes are related to individual differences in young preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors. We examined how these processes were related to children’s prosocial behaviors for the whole sample (combining children from different cultures) and for the Dutch and the Chinese sample separately, in order to examine whether there were culture-specific processes. Parents are core conduits for perpetuating systems of cultural priorities, and they transmit their personal and socio-cultural values to their child through socialization processes (Bornstein, Citation2012; Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Roccas & Sagiv, Citation2010). In accordance with the cultural value systems in which they are embedded, parents establish socialization goals for their children, and these processes may come to be reflected in their children’s behaviors.

Values

The current study focused on self-enhancement and self-transcendence values (Schwartz, Citation1973, Citation2006), which, according to Schwartz’s value theory, relate to prosocial behavior most frequently (Schwartz, Citation2006). Self-enhancement values emphasize personal success, achievement, status and dominance in the society, while self-transcendence values stress the welfare of others (Schwartz, Citation2006, Citation2010). Empirical research on adolescents and adults has shown that self-transcendence values are positively associated, while self-enhancement values are negatively associated with prosocial behaviors (for a review, see Schwartz, Citation2010). However, it is less clear whether and how parents’ values may relate to their children’s prosocial behaviors at early ages (Eisenberg, Wolchik, Goldberg, & Engel, Citation1992).

The existing body of research on values has two major limitations, which the present study addresses. First, previous research is mainly based on how the personal values of adolescents and adults relate to their own prosocial behaviors (e.g., Caprara & Steca, Citation2007). The socialization of these values from an older to a younger generation and its impact on the latter’s behavior has not been extensively researched. Second, these associations among younger children remain understudied. To our knowledge, only two studies examined the link between parental values and children’s prosocial behaviors. Hoffman (Citation1975) was the first to study the parental value of altruism, similar to Schwartz’s self-transcendence value, in relation to fifth-grade children’s prosocial behavior and found that its salience as a personal value of the parents was positively related to children’s prosocial behavior. In the second study (and perhaps the only such study with young children of 1–2 years), Eisenberg and her colleagues (1992), failed to find any association. Children that young may not be able to perceive and accept their parental values (Grusec & Goodnow, Citation1994). The current study focused on preschool children, who more likely have the social and cognitive skills needed to perceive parental values.

Goals

The socialization goals parents set for their children translate cultural-specific values into particular goals on shaping children’s prosocial behaviors (e.g., Kärtner et al., Citation2010; Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013). Socialization goals set for their children are largely based on, but not necessarily consistent with parental own personal values, because what is good for one generation may not be good for the next generation (Barni, Ranieri, Scabini, & Rosnati, Citation2011). This is especially the case for Chinese and Indian societies, which are experiencing rapid cultural changes. Thus, studies are needed to examine the contribution of parental values and goals separately on children’s early prosocial development.

The current study focused on parents’ autonomous and relational socialization goals that are central to the cultural models (e.g., Keller et al., Citation2006). When comparing the independence and the autonomous-relatedness models, cultural differences have been found to be more pronounced on relational than autonomous goals. No cultural differences on autonomous goals were found when comparing mothers from samples reflecting the independence model (e.g., Germany, North-American) and from the autonomous-relatedness model (e.g., urban India, Cameroon and Brazil), whereas mothers from the autonomous-relatedness model still emphasized relational socialization goals more than those in the independence model (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Kärtner et al., Citation2007, Citation2010; Köster, Schuhmacher, & Kärtner, Citation2015). In addition, within the autonomous-relatedness model, the urban, Chinese mothers emphasized autonomous goals more than the urban, Indian mothers, whereas no difference was found on the relational socialization goals (Keller et al., Citation2006).

Young children’s prosocial behaviors might be cultivated by different goals, depending on the culture in which children reside (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Kärtner, Citation2018; Kärtner et al., Citation2010). For instance, parents from Germany might regard prosocial behavior as a personal choice, whereas parents from India might regard prosocial behavior as a moral obligation toward other social members (Kärtner et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, prosocial behaviors may be guided by autonomous goals in the former whereas relational goals in the latter culture. However, the empirical evidence for this claim is limited. Only one study (Kärtner et al., Citation2010) directly examined the relations between parental goals and young children’s (19-month-olds’) prosocial behaviors in different cultures (Germany and India). A positive association between relational goals and toddlers’ prosociality was found across cultures, but not within each culture (Kärtner et al., Citation2010), implying that the association is not cultural-specific. Also, in this study no association was found between autonomous goals and toddlers’ prosociality, either within each culture or when both cultures were combined. Nevertheless, the lack of association between autonomous goals and prosocial behavior may be due to the young age of the children. From infancy to toddlerhood, parents gradually place more emphasis on children’s independence than dependence (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007). Accordingly, autonomous goals may become important for children’s prosocial behaviors when children are older.

Another remaining question is, which type of goals are more strongly related to prosocial behaviors in the autonomous-relatedness model. Because urban Indian and Chinese parents emphasize both autonomous and relational socialization goals for their children to a similar degree (e.g., Keller et al., Citation2006), there are three potential pathways. First, despite the cultural shift, Indian and Chinese parents might still regard prosocial behaviors as moral obligations and thus only relational goals would positively contribute to prosocial behaviors. Second, in line with the cultural shift, Indian and Chinese parents might regard prosocial behaviors as both moral obligations and a personal choice. Thus, both relational and autonomous goals would positively relate to prosocial behaviors. Third, because of the cultural shift, some parents might regard prosocial behavior as a moral obligation whereas others might view it as a personal choice. These heterogeneities would even out or cancel the contribution of either of these goals, leaving non-significant associations for each goal within each culture.

The current study

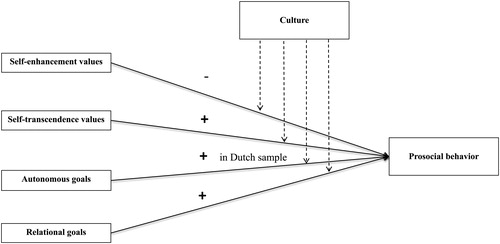

The aims of the current study were threefold. First, we explored whether young preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors differed from one culture to another. If cultural differences exist, then based on literature (for a review, see Eisenberg et al., Citation2006), we expected that the Chinese preschoolers would exhibit more prosocial behaviors than their Indian peers, who would, in turn, exhibit more prosocial behaviors than their Dutch peers (Hypothesis 1). Second, we explored the (potential) cultural differences on mothers’ values and goals. Based on the I-C spectrum, we would expect that mothers from the less individualistic/more collectivistic cultures deem self-transcendence values as more important, self-enhancement values as less important, have higher relational goals and lower autonomous goals for their children, compared to parents from more individualistic/less collectivistic cultures. However, based on the definitions of the three eco-cultural models (Keller et al., Citation2006) and the potential for continued change in values and goals in the urban Indian and urban Chinese samples based on recent studies, we took a more dynamic, exploratory approach. In light of previous studies (e.g., Kärtner et al., Citation2010; Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013; Schwartz, Citation2006, Citation2010), we expected that both Chinese and Indian mothers have lower self-enhancement values (Hypothesis 2a), higher self-transcendence values (Hypothesis 2 b), and higher relational goals (Hypothesis 2c) than the Dutch parents. In addition, we expected that both Dutch and Chinese mothers have higher autonomous goals than the Indian parents (Hypothesis 2d). Third, we examined how mothers’ values and goals uniquely predicted children’s prosocial behaviors and how these associations may vary across cultural contexts. We expected that self-transcendence values would be positively (Hypothesis 3a), while self-enhancement value negatively (Hypothesis 3 b) related to preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors in all samples (e.g., Schwartz, Citation2010). We expected relational goals would be positively (Hypothesis 3c) related to prosocial behaviors in all samples (Kärtner et al., Citation2010). Thus, for values and relational goals these associations should be found in all cultures, though the size of the associations may vary (e.g., Schwartz, Citation2010), and thus were explored them further (e.g., culture as a potential moderator) in the current study. Furthermore, the association between autonomous goals and prosocial behavior is exploratory and two alternatives are most likely (Hypothesis 3d). Although we expected that autonomous goals would not be related to children’s prosocial behavior given the findings of Kärtner et al. (Citation2010), autonomous goals might positively predict prosocial behaviors when parents emphasize children’s independence (Tamis-LeMonda et al., Citation2007). That is, this might be especially the case for mothers whose values reflect the independence model (i.e., the Dutch sample in the current study), in which prosocial behaviors are guided by a sense of autonomy (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017) ().

Figure 1. The conceptual mode in the current study. Note. This figure illustrates the conceptual model of the association between mother’s values, goals, and their children’s prosocial behaviors, based on previous empirical evidence and eco-cultural models of parenting (e.g., Keller et al., Citation2006; Schwartz, Citation2010). We explore the role of culture in these associations; for autonomous goals we expect a positive the link between mother’s autonomous goals and children’s prosocial in the Dutch sample, whereas this association could be either negative, non, or positive in the Indian and Chinese samples.

For these aims, we focused on young preschoolers, an age at which where children begin to incorporate cultural norms in their behaviors (Schuhmacher & Kärtner, Citation2015). The children were drawn from three cultures (i.e., Dutch, Indian and Chinese), which vary from one another in terms of their value systems. Specifically, the Dutch sample is characterized by the independence model, while the urban Indian and urban Chinese families are characterized by the autonomous-relatedness model. Preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors were examined through observation on three standardized behavioral assessments (i.e., sharing, instrumental helping, and empathic helping). Furthermore, mother’ values and goals were examined through mother-reports.

Method

The Dutch participants were 101 young preschoolers (M = 34.11 months, SD = 3.94 months, 55 boys) who participated in the last wave of a 3-wave longitudinal study concerning prosocial development from early toddlerhood (mean age: 22 months at wave 1, 28 months at wave 2) to early preschool age (34 months at wave 3). In the present study we focused on wave three as this is the age where culture may begin to contribute to prosocial behaviors (Schuhmacher & Kärtner, Citation2015). Their mothers reported on their own values (Wave 1 & 3), and socialization goals (all waves), with 30.53% of missing values on average across all parental measurements and waves. For all waves parental data was missing at random, p = 1.00, and was imputed by using an expectation-maximization algorithm (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, Citation1977). The Indian and Chinese participants joined the study for the third wave. The Indian participants were 37 preschoolers (M = 34.71 months, SD = 7.82 months, 15 boys), recruited through 2 daycares in Delhi, with 32 mothers completing the parental questionnaire on values and goals. The Chinese participants were 91 preschoolers (M = 48.54 months, SD = 6.15 months, 44 boys), recruited through 2 daycares in Shanghai. In addition, 76 mothers filled in the questionnaire. All three samples belonged to middle to upper class, educated backgrounds, with 83%, 100% and 80% of parents having either a university or professional degree for the Dutch, Indian, and Chinese samples, respectively. This research was approved by the Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Utrecht University. Informed written consent was obtained from all the parents of the children who participated in this study.

Procedure

All experiments were conducted by a main experimenter and an assistant experimenter at the participants’ daycare, either in a single play room or a semi-closed off area, and videotaped. Neither teachers nor parents were present during the testing. Preschoolers in the Chinese and Dutch samples participated in three tasks (sharing, instrumental helping and empathic helping) with the sharing task first, followed by the instrumental and empathic helping tasks in counterbalanced order. Indian preschoolers participated in two tasks (in order: sharing and instrumental helping). Parental questionnaires (i.e., mother-report on parental values and goals) were translated to Dutch/Chinese and back-translated for the parents in the Netherlands/China, and the original English versions were used in the Indian sample. All questionnaires were distributed to and returned by consenting parents through daycare teachers. Supplementary materials, summarizes the measurements (i.e., experimental tasks and questionnaires) employed in each sample.

Table 1. Descriptive information for preschooler’s observed prosocial behaviors, mothers’ values and goals.

Preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors

The preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors were observed in standardized behavioral assessments (sharing, instrumental helping and empathic helping), and then preschoolers’ performance in these tasks were transformed into two prosocial measures (i.e., a total prosocial score, and a mean prosocial readiness score).

Sharing task

The sharing task (based on Aknin, Hamlin, & Dunn, Citation2012) was conducted in all three samples. During a warm-up phase, the experimenter showed the child how to share treats with four stuffed animals. In the test phase the experimenter (a) introduced a monkey who had an empty bowl. Then the experimenter (b) found and gave eight, four, or two treats (for Dutch and Chinese sample), and either eight or two treats (for Indian sample) to the child.Footnote1 The next three phases of the experiment were counterbalanced across participants. These phases included (c) the experimenter finding a treat and giving it to the monkey, (d) the experimenter finding an additional treat and asking the child to give it to the monkey, and (e) the experimenter asking the child to share a treat with the monkey out of his/her own bowl. If the child ate the treat, or shared spontaneously before the phase/instruction (e), then the experimenter replaced the treat to make sure the child had a fixed number of resources when asked to share. The number of treats the child shared out of their own bowl, and how many treats they received in total in the task were coded. Two aspects of sharing were coded in the current study: (1) whether the preschooler shared in the experiment (0 = did not share, 1 = shared); (2) the total proportion of treats shared (i.e., number of treats shared/total number of treats received) by the child during the experiment.

Instrumental helping task

The instrumental helping task (based on Svetlova, Nichols, & Brownell, Citation2010) was conducted in all three samples. The experimenter showed five blocks to the child, each of which needed to be wrapped in a napkin. The experimenter then goes on to wrap four out of five blocks successfully and runs out of napkins. The child could help by handing the experimenter a napkin which was put within their reach, but beyond the experimenter’s. A set of eight cues were given to alert the child to the experimenter’s need of a napkin (see supplementary materials, ), ranging from facial/bodily/vocal expression of the need to a specific verbal request. The responses were coded from zero to eight, with a higher score indicating a higher level of helping (i.e., the child need fewer cues before helping). This coding was then transformed into a new dependent variable the likelihood of instrumental helping (whether the preschooler helped or not). Accordingly, two aspects of instrumental helping were coded: (1) whether the preschooler engaged in instrumental helping in the experiment (0 = did not help, 1 = helped); and (2) the readiness to help (i.e., steps needed before instrumental helping, 0 = did not help, 8 = helped after the first clue).

Empathic helping task

The empathic helping task (based on Svetlova et al., Citation2010) was conducted only in the Dutch and Chinese samples. The experimenter showed a blanket and stated, “It makes me warm.” Then, the experimenter put the blanket within the reach of the child but not the experimenter herself. Next, the experimenter gave the participant a distractor (toy bear) to play with. As the child played with the toy, the experimenter pretended to feel cold. The child could show empathic helping by handing the blanket to the experimenter. Similar to instrumental helping, a set of eight cues were given. Empathic helping was then coded and transformed in a similar manner as instrumental helping (see supplementary materials, ). The task was not conducted in the Indian sample, as the data collection was done during the peak of summer, which would have compromised the face validity of the task.

Inter-rater reliability for coding

For each sample, two independent research assistants who were blind to the research questions coded the videos (one coded all videos and another coded 20%). The inter-rater agreement (ICC) was high in all three samples with an average of 0.96 in the Indian sample, 0.91 in the Dutch and 0.98 in Chinese sample.

The resource and order effect on the observed prosocial tasks

We examined the effect of number of resources, the order for sharing tasks (for counterbalancing phase c to e, in total 6 possible orders) on observed sharing behavior; and the order in helping tasks (for counterbalancing instrumental helping and empathic helping) on observed instrumental helping and empathic helping behaviors. None of the effects were significant, ps > .140. Thus, the combined measures can be used and considered un-confounded by order effects.

Transformation into the two dependent variables of prosocial behaviors

We transformed the coding into two dependent variables of prosocial behaviors in the current study. First, we created a total prosocial score indicating the frequency of prosocial behavior as indicated by the number of tasks in which the child showed prosocial behavior (i.e., whether the preschooler shared/engaged in instrumental helping/engaged in empathic helping across, ranging from (0 = did not engage in any prosocial tasks to 3 = engaged in all three prosocial tasks). Second, we also created a mean prosocial readiness score indicating the degree to which the child readily performed each behavior. This was done by converting the readiness indicators for each task to z-scores and then calculating a mean of the three scores (i.e., we combined the z scores for the total proportion of treats shared, the readiness to help instrumentally, and the readiness to help empathically).

Measurements on mothers’ values and goals

Values

Mothers completed the self-enhancement and self-transcendence subscales of the 21-item Portraits Value Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz et al., Citation2001), which has been shown to be valid across countries and cultures (Schwartz, Citation2003), including Dutch (Krystallis, Vassallo, Chryssohoidis, & Perrea, Citation2008), Indian (Christopher & Reddy, Citation2014), and Chinese cultures (Feldman, Chao, Farh, & Bardi, Citation2015) samples. The questionnaire consists of portraits or statements about a person and the respondents answers the degree to which the portrait describes themselves on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (“very much like me”) to 6 (“not like me at all”).Footnote2 That is, these portraits implicitly indicate the importance of the value associated with each statement for the respondent. In this way, the responses were less likely to be affected by social desirability. The Self-enhancement subscale contained 4 items (e.g., “Being very successful is important to her. She likes to impress other people”), and the Self-transcendence subscale comprised 5 items (e.g., It's very important to her to help the people around her. She wants to care for their well-being). These portraits implicitly indicate the importance of the value associated with each statement. Therefore, a lower score means the value is more important. The scales were re-coded in the reverse direction for analyses, with higher scores indicating that the value is more important to the participants. The reliability of self-enhancement and self-transcendence scale in the present study was found to be low to moderate (see ), although comparable to previous studies (e.g., Schwartz, Citation2003), and should not be an issue because the items are supposed to tap different values, and even different concepts within the same value (Schwartz, Citation2003).

Goals

Mothers’ goals were measured by the Socialization Goals Questionnaire (Kärtner et al., Citation2010), which consisted of two subscales. This questionnaire shows good structural equivalence across cultures (Kärtner et al., Citation2010) and has been used in comparing parental goals between parents from individualistic (e.g., Germany) and collectivistic cultures (e.g., Indian) (e.g., Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Kärtner et al., Citation2010). The autonomous subscale contained 4 items (i.e., during the first 3 years of life, children should develop: self-confidence; assertiveness; a sense of self-esteem; a sense of self). The relational socialization goals subscale contained 5 items (i.e., learn to help others; care for the well-being of others; cheer up others, learn to obey parents; learn to obey older persons). Parents reported how important these goals are for them on a 6-point Likert scale, ranging from 1 (not important at all) to 6 (extremely important). The reliability of the parent-reports was found to be high in all samples ().

Measurement invariance across cultures

Given the small sample sizes, we examined the structure equivalence across cultures per subscale, in AMOS 24.0. For each subscale, we compared two models, including (A) a baseline model with no constraints on the factor loadings, and (B) an equal measurement weights model, in which the factor loading of each item was constrained to be the same (i.e., equal) across three cultures (Byrne, Citation2004). If the model fit of model B was not significantly worse than Model A (using Chi-square comparisons), the subscale was interpreted as showing measurement invariance across three cultures. Otherwise, we checked item one by one, by freeing the item loading in Model B. If this new model was no longer worse than model A, then it meant the item we free cannot be interpreted in the same way across cultures. We repeated the comparisons until all the items that could not be constrained as equal were identified. These items were later deleted in calculating the mean score for the subscale. Based on this logic, one item for parental autonomous goals, “develop a sense of self-esteem” was dropped. For other subscales, the model comparison results showed no significant difference between Model A (baseline model) and Model B, ps > .05.

Results

Analysis plan

Preliminary analyses were conducted to (1) examine the effect of age and gender on young preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors. (2) In addition, because the Indian preschoolers participated in two prosocial tasks (sharing and instrumental helping) whereas the Dutch and the Chinese preschoolers participated in three (sharing, instrumental helping and empathic helping), we investigated whether the combined measures would be comparable between the Indian scores (based on 2 tasks) and the Chinese/Dutch scores (that were based on 3 tasks). More specifically, we examined the associations between the measures in the empathic helping task and in sharing/instrumental helping tasks (report in supplementary materials). If these variables were not highly associated (r < .50), then we think the Indian prosocial score was not comparable to the Dutch/Chinese score, and thus we dropped the Indian sample in examining the (potential) cultural difference on prosocial behaviors in the main analyses. (3) Furthermore, we examined the differences of three observed prosocial behaviors per sample (report in supplementary materials).

Three main sets of analyses were conducted. First, we examined the potential cultural differences on prosocial behaviors (aim 1). We used Kruskal–Wallis H test (or the Mann-Whitney U test if the preliminary analyses showed the Indian sample has to be dropped) for the ordinal variable (i.e., a total prosocial score), and used one-way, between-subject ANOVA (or independent sample t-test) for the continuous variable (i.e., a mean prosocial readiness score). In addition, we controlled for age/gender if the preliminary analyses showed its effect.

Second, we examined cultural differences on mothers’ values and goals (aim 2), by using one-way, between-subject ANOVA on each type of values (i.e., self-enhancement and self-transcendence values) and goals (autonomous and relational goals).

Third, we examined the general and cultural-specific associations between mothers’ values/goals and children’s prosocial behaviors (aim 3). Because the Indian sample was small (n = 32), we did not include this sample in this set of analyses. We used ordinal regression analyses for a total prosocial score, and hierarchical multiple regression analyses for a mean prosocial readiness score. Three sets of analyses were conducted for each dependent variable. First, in order to examine the associations across cultures, we combined samples and put culture in step 1 (one dummy variable, Dutch = −1 and Chinese culture = 1), and all mothers’ measures (values and goals) in step 2. Second, to examine whether culture moderated the associations between mothers’ values/goals and their children’s prosocial behaviors, we further put culture by mothers’ measure interactions in step 3. It should be noted that for each moderator analysis, we only included one interaction at a time. Third, in order to examine culture-specific associations, we re-analyzed the data per sample by putting all mothers’ measures in the regression at once.

Preliminary analysis

We found age was significantly associated with two prosocial measures, ps < .028 (), with older children engaged in more prosocial tasks, and being more readily than younger children. Thus, we controlled for age in the following analyses. In addition, among the Chinese and Dutch samples, we found very low correlations between empathic helping and sharing (r = .15 and r = .14, for the Dutch and Chinese samples, Supplementary materials, ); and only modest correlations between empathic helping and instrumental helping (r = .32 and r = .39, for the Dutch and Chinese samples). Overall, these results indicate that the combined scores drew from two tasks (i.e., the Indian prosocial scores) was not comparable to the score drew from the three tasks (i.e., the Dutch/Chinese prosocial scores), and thus the Indian data were dropped in examining potential cultural difference on prosocial behaviors in the main analyses.

Table 2. Correlations among variables.

Cultural differences in young preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors

Descriptive information is provided in . There was no cultural difference on the prosocial measures, ps > .059. Thus, Hypothesis 1 was not supported.Footnote3

Cultural differences in mothers’ values and goalsFootnote4

Values

Cultural differences were found on self-enhancement values, F(2, 209) = 24.13, p <.001. Post-hoc analyses (using Bonferroni corrections) showed that both Indian and Chinese mothers rated self-enhancement values as more important than Dutch parents, ps < .001, with no differences between Indian and Chinese mothers, p = 1.00. These findings were contrast to the Hypothesis 2a (i.e., Indian and Chinese mothers have lower self-enhancement values than the Dutch mothers). Also, there was a cultural difference on self-transcendence values, F(2, 209) = 16.03, p < .001. Post-hoc analyses showed that Indian mothers rated self-transcendence values as more important than both Dutch and Chinese mothers, ps < .001, with no differences between Dutch and Chinese mothers, p = .452. These findings partly supported Hypothesis 2b (i.e., both Chinese and Indian mothers have higher self-transcendence values than Dutch mothers).

Goals

There was a cultural difference on relational goals, F(2,209) = 7.83, p =.001. Post-hoc analyses showed that Indian mothers endorsed relational goals for their children more than Dutch and Chinese mothers, ps < .001, with no difference between Dutch and Chinese mothers, p = 1.00. These findings partly supported Hypothesis 2c (i.e., both Chinese and Indian mothers have higher relational goals than the Dutch mothers). However, no cultural differences were found on the autonomous goals, F(2,209) = 0.21, p = .813, leading to no support for the Hypothesis 2d (i.e., both Dutch and Chinese mothers have higher autonomous goals for their children than Indian mothers).

Mothers’ values and goals, and young preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors

Results for the bivariate correlation analyses found that (), when all samples were combined, the dependent variable, a total prosocial score, negatively associated with mother’s self-transcendence values, r = −.20, p = .003. For the Dutch sample, a mean prosocial readiness score was positively associated with autonomous goals, r = .21, p = .040. For the Indian and the Chinese samples, no associations were found. In order to further take correlations between predictors into account, we conducted hierarchical regression analyses. Please note that we only included the Dutch and Chinese samples in the following analyses, because the Indian sample was too small (n = 32), and because the preliminary analyses found dependent variables on observed prosocial behaviors were not comparable between the Indian and the Dutch/Chinese sample.

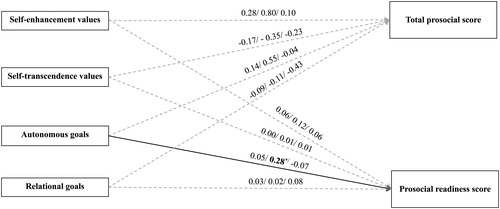

For each dependent measure, we first examined the associations when both samples were combined. Culture (Dutch = −1, Chinese = 1) was entered in the step 1 and mother’s values and goals were entered in the step 2. No significant associations were found ().

Table 3. Regressions for relations between mothers’ measurements and observed prosocial behaviors (including the Dutch and Chinese samples).a

Second, we ran the moderator analyses. Only for the dependent variable, a mean prosocial readiness score, the interaction term (culture by autonomous goals) was significant, B = −0.11, p = .043.

Third, we further conducted the analyses within the Dutch and Chinese culture for a better understanding of the association within each sample. In the Dutch sample, autonomous goals were positively associated with a mean prosocial readiness score, B = 0.28, p = .040. That is, Dutch mothers who reported autonomous goals as more important for their children have children who engaged in prosocial behaviors more readily ().Footnote5 In the Chinese sample, no significant associations was found.Footnote6 Overall, we found evidence that supports Hypothesis 3d (association between autonomous goals and prosocial behaviors). However, Hypothesis 3a (positive association between self-transcendence values and prosocial behaviors), 3 b (negative association between self-enhancement values and prosocial behaviors), or 3c (positive association between relational goals and prosocial behaviors) were not supported ().

Figure 2. Summary of hierarchical regression results for the conceptual model. Note. This figure demonstrates the results to the conceptual model. The significant coefficient was shown in bold, and the significant association was shown in solid line. * = p < .05. For each association, the numbers represent the coefficient (B) in the following order: Dutch and Chinese samples combined/Dutch sample/Chinese sample. The Indian data was not included in the regression analyses.

Discussion

The current study (1) compared the prosocial behaviors of young preschoolers from India, China and the Netherlands, (2) explored whether there were cultural differences on socialization processes (i.e., mothers’ values and goals), and (3) investigated whether they contributed to individual differences in prosocial behaviors. These associations were examined for the Chinese and Dutch samples separately, and when both samples were combined.

Cultural differences

Drawing from past research on cultural differences in children’s prosocial behavior (Eisenberg et al., Citation2006; Insights, Citation2019) as well as the ecocultural model of development (e.g., Keller et al., Citation2006), we expected that Chinese preschoolers would show more prosocial behaviors than Indian preschoolers, who would in turn show more prosocial behaviors than Dutch preschoolers. We also expected that both Chinese and Dutch mothers have lower self-enhancement values, higher self-transcendence values, higher relational goals than the Dutch mothers, and the Dutch and Chinese mothers have higher autonomous goals than the Indian mothers.

Contrary to our expectations, results showed no cultural differences on prosocial behaviors, neither in the amount of prosocial behaviors nor the readiness to be prosocial. Also, we found no cultural difference on any specific prosocial measures (reported in the supplementary materials). A potential explanation based on the ecocultural model is that, the similarities in prosocial behaviors among cultures may result from the different, cultural-specific associations between socialization processes and prosocial behaviors(Kärtner et al., Citation2010), and we further examine this explanation in the following.

The current study found cultural differences on mothers’ values and goals that go beyond the I-C spectrum in categorizing the cultures, and instead support eco-cultural models (Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Keller et al., Citation2006). Specifically, although mothers in the Indian sample rated self-transcendence values (e.g., welfare of others) as more important and had higher relational goals for their children than did mothers in the Dutch and Chinese samples, unexpectedly, Indian and Chinese mothers rated self-enhancement values (e.g., dominance in the society) as more important than the Dutch mothers. In addition, there were no differences across cultures in the degree to which mothers emphasized autonomy as a goal for their children. Thus, mothers in both the Indian and Chinese samples may be showing a substantial shift in their own valuing of self-enhancement and, in the Chinese sample, a shift away from relatedness. In addition, these findings further add to the debate as to whether the autonomous-relatedness model indeed reflects a distinct cultural category in its own right or whether it reflects a transitory stage between dependence and independence (see Kağitçibaşi, Citation1996; Keller et al., Citation2006). Given that our samples were studied at least 12 years after those of the Keller et al. (Citation2006), the difference between the Indian and the Chinese sample on relational goals may reflect a shift from an autonomous-related cultural model to an independence model in describing the current urban Chinese society. However, more empirical research across time and age cohorts is needed to see whether these differences are replicated and the shift continues.

Values and goals in relation to individual differences in prosocial behaviors

Our next aim was to examine whether parental values and goals were related to individual differences in children’s prosocial behaviors. Only the Dutch and the Chinese sample were included in these analyses for methodological reasons. Unexpectedly, no associations were found between parental values and children’s observed prosocial behaviors. These findings, however, are in line with the previous findings in 1- and 2-year-olds (Eisenberg et al., Citation1992), further suggesting that before age four, children may not be able to perceive or accept parental values (Grusec & Goodnow, Citation1994).

As for parental goals, culture moderated the association between autonomous goals and prosocial readiness. Only in the Dutch sample, mothers’ emphasis on autonomous goals (e.g., self-esteem) was (positively) related to toddlers’ readiness to be prosocial. As a complement to this cross-sectional finding (at wave 3, age 34 months), the association was found longitudinally (from goals at wave 2 predicting prosocial readiness at wave 3, age 28 to 34 months). Together, results in the current Dutch sample repetitively support the theoretical proposal that young children’s prosocial behavior may likely reflect a personal choice in Western cultures (e.g., Kärtner et al., Citation2010). Approaching age three, a sense of autonomy (or in this case mother’s encouragement of autonomy vis a vis their goals for autonomy) would be important for children to take initiative in prosocial behaviors. Nevertheless, these associations have not been found at younger ages, neither at 19 months (Kärtner et al., Citation2010), nor in the current sample at 22 and 28 months. Accordingly, solely trying to foster autonomous behavior may not be sufficient for eliciting children’s prosocial behavior around age two.

Unexpectedly, no association was found between parental relational goals and prosocial behaviors, within the Dutch or Chinese sample or when the two samples were combined. There are at least two implications from these results. First, although relational goals have been found to predict 2 year olds’ prosocial responding to a person in distress, (Kärtner et al., Citation2010), by age three autonomous decision making may be driving this behavior – at least in the Dutch sample. The lack of an association between relational goals and children’s prosocial behavior in the Chinese sample is more perplexing. Although prosocial behaviors are often regarded as moral obligations in traditional, collectivistic cultures (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017), and thus should predict prosocial behaviors in these cultures, the cultural values and parenting goals represented in the current sample of urban Chinese mothers may represent a transition toward independent model that is not yet attained. The rapid cultural transformation in urban Chinese settings that has occurred over the past 20 years could have resulted in heterogeneities in socialization goals, with some but not all mothers having autonomy as a strong goal for child rearing whereas others may find relational goals as more important, and still other parents may have both autonomy and relational goals for their children. These heterogeneities may even out the contribution of either goal. Thus, studies are needed that can further tease apart how these competing goals are combined both within parents and across parents within each culture (e.g., Keller et al., Citation2006).

Overall, these findings provide some evidence on the ecocultural model (Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013). Together with the previous findings (e.g., Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Kärtner et al., Citation2007, Citation2010; Köster et al., Citation2015), finding from the current study imply that which socialization goals are needed to attain prosocial behavior may not only depend on the cultural contexts, but child age. In addition, a cultural shift toward independence in societies that traditionally are viewed as interdependent potentially requires more scrutiny on the coexistence of autonomous and relational goals, and how their coexistence changes over time in predicting children’s prosocial development.

Limitations and future directions

Several limitations should be addressed in further research. First, the motivation demands in the prosocial tasks were low (i.e., to push forward or give an object by their side in order to help or share) which could have masked finding cultural differences. Indeed, toddlers from India were more likely to help than their peers from Germany when the motivation demands of prosocial behavior were higher (Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017). Thus, more studies that manipulate motivational demands (e.g., toddlers have to walk across the room to fetch the object for the experimenter in helping, or to share spontaneously) are needed. Second, due to practical reasons we recruited children from daycares with the result that the Chinese participants were older than the Dutch and Indian participants because Chinese daycares only enroll children who are at least 3 years old by September of that academic year. Nevertheless, age was controlled for in the analyses. Third, in the sharing task we assigned participants into three treat conditions (i.e., 2, 4, 8 treats), which may affect their sharing behavior. For example, in 2-treat condition, the proportion of items shared would be at 50% once they shared. Also, limited by number of participants, in the Indian sample only 2 or 8 treats conditions were assigned. Nevertheless, the treat condition did not affect preschooler’s performance in the sharing task in the current study. Fourth, the moderation effect and the association between autonomous goals and prosocial behaviors within the Dutch sample were not significant after correcting for multiple testing (although it was replicated in the longitudinal analyses). Whether these correlations still hold in additional, larger samples needs to be investigated. Fifth, the current study only focused on parental values and goals. According to the eco-cultural models (e.g., Keller & Kärtner, Citation2013; Keller et al., Citation2006) and relevant studies (e.g., Giner Torréns & Kärtner, Citation2017; Köster et al., Citation2015), a more comprehensive examination is needed to include specific parental behaviors that might provide further insights into the specific motivations underlying prosocial behaviors. Sixth, the current study only focused on mother’s, rather than father’s socialization processes. Knowledge on fathers’ early parenting is underdeveloped (Kochanska, Aksan, Prisco, & Adams, Citation2008), though fathers may contribute to children’s prosocial behavior uniquely (Hammond & Carpendale, Citation2015; LaBounty, Wellman, Olson, Lagattuta, & Liu, Citation2008). Thus, more studies are needed to examine fathers’ role in children’s prosocial development.

Conclusions

The current study contributes to the knowledge of whether and how culture plays a role in children’s prosocial behaviors. Despite finding cultural differences on some parental values and goals related to the socialization of prosocial behavior among Dutch, Indian and Chinese mothers, we did not find any cultural differences in children’s prosocial behaviors. Moreover, based on eco-cultural models, mothers in the urban, Chinese societies may be shifting toward valuing independence over relatedness. Although parental values did not contribute to prosocial behavior in these young children, for Dutch children, their mother’s autonomous goals predicted their prosocial behavior. The lack of associations between maternal goals and children’s prosocial behavior among the Indian and Chinese samples suggest there are culture-specific pathways for fostering young children’s prosocial behavior but the challenge for research is to identify what these pathways might be for societies undergoing significant cultural change. Despite these differences in pathways, young preschoolers from various cultures may be more alike in their prosocial behavior than different.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (44.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, Yue Song (email: [email protected]). The data are not publicly available due to restrictions under the ethical committee of [blinded for review]. In the data, there is information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Yue Song

Yue Song received her Doctoral degree at November 22, 2019. She is interested in the development of prosocial behaviors among toddlers and preschoolers, the links between these behaviors and happiness, and the socialization effects on these relationships. Her recent studies focus on the impact of different cultural backgrounds on sharing and helping behaviors during toddlerhood.

Srishti Malhotra

Srishti Malhotra is a research master student. She is interested in the development of prosocial behaviors and her studies focus on the impact of different cultural backgrounds on sharing and helping behaviors during toddlerhood.

Martine Broekhuizen

Dr. Martine Broekhuizen studies child care quality and young children’s social and emotional development. Current projects relate to child care quality in the Netherlands and Norway, investigating the early origins of educational inequalities, and improving parent-preschool involvement and the home learning environment.

Yan Wang

Yan Wang is professor of Psychology at Fudan University. Her research fields include children’s social behavior development, parenting, and social adaptive behavior of college students.

Bin-Bin Chen

Bin-Bin Chen is an associate professor of Psychology at Fudan University. His research areas are child development and evolutionary psychology. Specific topics include parenting behaviors, parent-child attachment, romantic attachment, peer relationships, social skills, risk taking behaviors, and rural-to-urban migrant children’s social development.

Judith Semon Dubas

Judith Semon Dubas is professor of Developmental Psychology at Utrecht University. She uses an evolutionary developmental perspective to study the early development of prosocial behavior, adolescent risk taking and parental investment.

Notes

1 The purpose for assigning different treats was for another paper examining the resource effect (2, 4, or 8 treats) on sharing behavior in the Dutch sample. In that paper we found the number of treats received did not affect the proportion of treats shared. In order to have comparable conditions, we also varied the number of treats in the Chinese and Indian samples. Due to the small sample size in the Indian sample, we only used 2- and 8-treat condition. In addition, in the current study we found that treat condition did not affect the likelihood of sharing, or the total proportion of treats shared.

2 Twenty-one questionnaires given out to a school in India had a typing error in the values scale, wherein response category 5, “not like me” was labeled the same as category 2, that is “like me.” No significant differences (p > .05) were found in the endorsement of any of the six response categories between the questionnaires with and without the typing error, and therefore, all were retained for analyses.

3 We also compared cultural difference per prosocial task among the Dutch, Indian and Chinese cultures (i.e., compared the sharing and instrumental helping among the three cultures, and compared the empathic helping between the Dutch and Chinese cultures). Again no cultural difference was found (report in supplementary materials).

4 Because the Indian sample was small, we conducted Bayesian analyses and the conclusions remained the same for the between-cultural difference on mother reported values and goals.

5 Because the Dutch data include three waves, we conducted supplementary analyses to further investigate how mothers’ socialization processes contribute to children’s prosocial behavior longitudinally. Specifically, we conducted three sets of regression analyses that examined whether mothers’ values/goals at wave 1 predicted children’s prosocial behaviors at wave 2 (set 1) and wave 3 (set 2), also whether mothers’ values/goals at wave 2 predicted children’s prosocial behaviors at wave 3 (set 3), with the respective prosocial behavior in the same wave as maternal behavior controlled (that is, wave 1 prosocial behavior for set 1 and set 2, and wave 2 prosocial behaviors for set 3). In set 1 and set 2, none of the predictors were significant, ps > .067. In set 3 (from wave 2 to wave 3), maternal autonomous goals at wave 2 positively predicted preschoolers’ prosocial behaviors (a prosocial readiness score) at wave 3, B = 0.28, p = .049. It should be noted that prior to the regression analyses, measurement invariance tests were conducted on all measures.

6 To test the robustness of these significant results, we used Bonferroni correction with the regression coefficients (Abdi, Citation2010). The interaction term (culture by autonomous) was no longer significant after Bonferroni correction (p < .050/7 = .007). However, the interaction effects are generally underestimated and difficult to detect (Kärtner et al., 2010), and it is suggested to use a p < .10 to indicate significance for moderator analyses (Aiken & West, Citation1991; Pedhazur, Citation1997). Thus, the current finding is informative for further directions, though must be interpreted with caution. Also, the association within the Dutch sample was no longer significant, p < .050/5 = .010.

References

- Abdi, H. (2010). Holm’s sequential Bonferroni procedure. Encyclopedia of Research Design, 1, 1–8.

- Aiken, L. S., & West, S. G. (1991). Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Aime, H., Broesch, T., Aknin, L. B., & Warneken, F. (2017). Evidence for proactive and reactive helping in two- to five-year-olds from a small-scale society. PLoS One, 12(11), e0187787. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0187787

- Aknin, L. B., Hamlin, J. K., & Dunn, E. W. (2012). Giving leads to happiness in young children. PLoS One, 7(6), e39211. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0039211

- Barni, D., Ranieri, S., Scabini, E. & Rosnati, R. (2011). Value transmission in the family: Do adolescents accept the values their parents want to transmit? Journal of Moral Education, 40(1), 105–121. doi:10.1080/03057240.2011.553797

- Bornstein, M. H. (2012). Cultural approaches to parenting. Parenting, Science and Practice, 12(2-3), 212–221. doi:10.1080/15295192.2012.683359

- Byrne, B. M. (2004). Testing for multigroup invariance using AMOS Graphics: A road less traveled. Structural Equation Modeling, 11, 272–300.

- Caprara, G. V., & Steca, P. (2007). Prosocial agency: The contribution of values and self–efficacy beliefs to prosocial behavior across ages. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 26(2), 218–239. doi:10.1521/jscp.2007.26.2.218

- Carlo, G., Roesch, S. C., Knight, G. P., & Koller, S. H. (2001). Between- or within-culture variation?: Culture group as a moderator of the relations between individual differences and resource allocation preferences. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 559–579. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973. (01)00094-6 doi:10.1016/S0193-3973(01)00094-6

- Christopher, P. B., & Reddy, B. D. (2014). Influence of culture in handling conflict situation-with special reference to Indian sub cultural diversity. Asian Social Science, 10(4), 31–37. doi:10.5539/ass.v10n4p31

- Dempster, A. P., Laird, N., & Rubin, D. (1977). Maximum likelihood for incomplete data via the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (Methodological), 39(1), 1–38. doi:10.1111/j.2517-6161.1977.tb01600.x

- de Guzman, M. R. T., Do, K. A., & Kok, C. M. (2014). The cultural contexts of children’s prosocial behaviors. In L. M. Padilla-Walker & G. Carlo (Eds.), Prosocial development: A multidimensional approach (pp. 2220–2235). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Dunfield, K. A. (2014). A construct divided: Prosocial behavior as helping, sharing, and comforting subtypes. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 958. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00958

- Eisenberg, N., Fabes, R. A., & Spinrad, T. L. (2006). Prosocial development. In W. Damon, R. M. Lerner, & N. Eisenberg (Eds.). Social, emotional, and personality development. Handbook of child psychology: Vol. 3 (6th ed., pp. 646–718). New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- Eisenberg, N., Wolchik, S. A., Goldberg, L., & Engel, I. (1992). Parental values, reinforcement, and young children's prosocial behavior: A longitudinal study. The Journal of Genetic Psychology, 153(1), 19–36. doi:10.1080/00221325.1992.10753699

- Feldman, G., Chao, M. M., Farh, J. L., & Bardi, A. (2015). The motivation and inhibition of breaking the rules: Personal values structures predict unethicality. Journal of Research in Personality, 59, 69–80. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2015.09.003

- Giner Torréns, M., & Kärtner, J. (2017). The influence of socialization on early helping from a cross-cultural perspective. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 48(3), 353–368. doi:10.1177/0022022117690451

- Greenfield, P. M., & Keller, H. (2004). Cultural psychology. In C. Spielberger (Ed.), Encyclopedia of applied psychology (pp. 545–553). Oxford, UK: Elsevier.

- Greenfield, P. M., Keller, H., Fuligni, A., & Maynard, A. (2003). Cultural pathways through universal development. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 461–490. http://doi/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145221

- Grusec, J. E., & Goodnow, J. J. (1994). Impact of parental discipline methods on the child's internalization of values: A reconceptualization of current points of view. Developmental Psychology, 30(1), 4–19. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.30.1.4

- Hammond, S. I., & Carpendale, J. I. (2015). Helping children help: The relation between maternal scaffolding and children's early help. Social Development, 24(2), 367–383. doi:10.1111/sode.12104

- Hoffman, M. L. (1975). Developmental synthesis of affect and cognition and its implications for altruistic motivation. Developmental Psychology, 11(5), 607– 622. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.11.5.607

- Insights, H. (2019). Compare countries. Retrieved from Hofstede Insights: https://www.hofstede-insights.com/product/compare-countries

- Kağitçibaşi, C. (1996). Family and human development across cultures: A view from the other side. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc., Publishers.

- Kärtner, J. (2018). Beyond dichotomies-(m)others' structuring and the development of toddlers' prosocial behavior across cultures. Current Opinion in Psychology, 20, 6–10. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.07.040

- Kärtner, J., Keller, H., & Chaudhary, N. (2010). Cognitive and social influences on early prosocial behavior in two sociocultural contexts. Developmental Psychology, 46(4), 905–914. doi:10.1037/a0019718

- Kärtner, J., Keller, H., Lamm, B., Abels, M., Yovsi, R. D., & Chaudhary, N. (2007). Manifestations of autonomy and relatedness in mothers' accounts of their ethnotheories regarding child care across five cultural communities. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 38(5), 613–628. doi:10.1177/0022022107305242

- Keller, H. (2007). Cultures of infancy. Mahwah, NJ: Erlbaum

- Keller, H., & Kärtner, J. (2013). Development: The cultural solution of universal developmental tasks. Advances in Culture and Psychology, 3, 63–116. doi:10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780199930449.001.0001.

- Keller, H., Lamm, B., Abels, M., Yovsi, R., Borke, J., Jensen, H., … Chaudhary, N. (2006). Cultural models, socialization goals, and parenting ethnotheories: A multicultural analysis. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 37(2), 155–172. doi:10.1177/0022022105284494

- Kochanska, G., Aksan, N., Prisco, T. R., & Adams, E. E. (2008). Mother-child and father-child mutually responsive orientation in the first 2 years and children's outcomes at preschool age: Mechanisms of influence. Child Development, 79(1), 30–44. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01109.x

- Köster, M., Schuhmacher, N., & Kärtner, J. (2015). A cultural perspective on prosocial development. Human Ethology Bulletin, 30(2), 71–82. doi:10.1080/09578819608426662

- Krystallis, A., Vassallo, M., Chryssohoidis, G., & Perrea, T. (2008). Societal and individualistic drivers as predictors of organic purchasing revealed through a portrait value questionnaire (PVQ)‐based inventory. Journal of Consumer Behaviour, 7(2), 164–187. doi:10.1002/cb.244

- LaBounty, J., Wellman, H. M., Olson, S., Lagattuta, K., & Liu, D. (2008). Mothers' and fathers' use of internal state talk with their young children. Social Development, 17(4), 757–775. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00450.x

- Lu, X. (1998). An interface between individualistic and collectivistic orientations in Chinese cultural values and social relations. Howard Journal of Communications, 9(2), 91–107. doi:10.1080/106461798247032

- Pedhazur, E. J. (1997). Multiple regression in behavioral research. Fort Worth, TX: Harcourt Brace College.

- Rao, N., & Stewart, S. M. (1999). Cultural influences on sharer and recipient behavior: Sharing in Chinese and Indian preschool children. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 30(2), 219–241. doi:10.1177/0022022199030002005

- Rochat, P., Dias, M. D., Liping, G., Broesch, T., Passos-Ferreira, C., Winning, A., & Berg, B. (2009). Fairness in distributive justice by 3-and 5-year-olds across seven cultures. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 40(3), 416–442. doi:10.1177/0022022109332844

- Roccas, S., & Sagiv, L. (2010). Personal values and behavior: Taking the cultural context into account. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(1), 30–41. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00234.x

- Schuhmacher, N., & Kärtner, J. (2015). Explaining interindividual differences in toddlers' collaboration with unfamiliar peers: Individual, dyadic, and social factors. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 493. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00493

- Schwartz, S. H. (1973). Normative explanations of helping behavior: A critique, proposal, and empirical test. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 9(4), 349–364. https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-1031. (73)90071-1 doi:10.1016/0022-1031(73)90071-1

- Schwartz, S. H. (2003). A proposal for measuring value orientations across nations. In Questionnaire development report of the European Social Survey (chaper. 7). Retrieved from http://naticent02.uuhost.uk.uu.net/questionnaire/chapter_07.doc

- Schwartz, S. H. (2006). A theory of cultural value orientations: Explication and applications. Comparative Sociology, 5(2-3), 137–182. doi:10.1163/156913306778667357

- Schwartz, S. H. (2010). Basic values: How they motivate and inhibit prosocial behavior. In M. Mikulincer & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Prosocial motives, emotions, and behaviour: The better angels of our nature (pp. 221–241). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Schwartz, S. H., Melech, G., Lehmann, A., Burgess, S., Harris, M., & Owens, V. (2001). Extending the cross-cultural validity of the basic human values with a different method of measurement. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 32(5), 519–542. doi:10.1177/0022022101032005001

- Sinha, D., & Tripathi, R.C. (1994). Individualism in a collectivistic culture: A case of coexistence of opposites. In K. Uichol, H. Triandis, Ç. Kağitçıbaşi, S. Choi, & G. Yoon (Eds.), Individualism and collectivism: Theory, method, and applications (pp. 123–136). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Stewart, S. M., & McBride-Chang, C. (2000). Influences on children’s sharing in a multicultural setting. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 31(3), 333–348. doi:10.1177/0022022100031003003

- Svetlova, M., Nichols, S. R., & Brownell, C. A. (2010). Toddlers' prosocial behavior: From instrumental to empathic to altruistic helping. Child Development, 81(6), 1814–1827. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01512.x

- Tamis-LeMonda, C. S., Way, N., Hughes, D., Yoshikawa, H., Kalman, R. K., & Niwa, E. Y. (2007). Parents' goals for children: The dynamic coexistence of individualism and collectivism in cultures and individuals. Social Development, 17(1), 183–209. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9507.2007.00419.x

- Triandis, H. C. (2001). Individualism-collectivism and personality. Journal of Personality, 69(6), 907–924. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.696169

- Warneken, F. (2016). Insights into the biological foundation of human altruistic sentiments. Current Opinion in Psychology, 7, 51–56. doi:10.1016/j.copsyc.2015.07.013

- Warneken, F., & Tomasello, M. (2009). The roots of human altruism. British Journal of Psychology, 100(Pt 3), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1348/000712608X379061.