Abstract

Problem-solving skills are often considered to be the key skills in today’s world, and their importance in geography education is widely recognized. However, empirical evidence analyzing whether and how teachers develop problem-solving skills during geography lessons is especially scarce in the context of preservice teachers. Accordingly, we conducted a questionnaire survey with 256 respondents. The survey analyzed preservice teachers’ experience with problem-solving skills and different teaching styles in their pre-college (upper secondary) geography education. The results show that preservice geography teachers prevailingly perceive that they were not exposed to problem-solving skills even passively, let alone actively developing them. The insufficient development is in line with the prevalence of teacher-centered styles. The article concludes with a discussion of possible causes and recommendations for improvement.

Introduction

The importance of geography education is currently being challenged. The last two decades have seen vast discussions about the decreasing image and weakened position of geography in education (e.g., Bednarz, Heffron, and Solem Citation2014; Chang Citation2014; van der Schee Citation2014; Béneker, Palings, and Krause Citation2015; Lane and Bourke Citation2017; Virranmäki, Valta-Hulkkonen, and Pellikka Citation2021). While geography offers a unique perspective on fundamental problems such as climate change, sustainability, global pandemics, migration, inequality, etc., it is still often perceived as the simple knowledge of facts about different world regions (Favier and van der Schee Citation2012; Bendl and Marada Citation2021). However, in accordance with general scientific consensus in geography education research, we believe that geography education should pave the way toward powerful knowledge (Young Citation2009; Solem, Lambert, and Tani Citation2013; Maude Citation2016), thinking geographically (Jackson Citation2006; Geographical Association Citation2009), or being a geographically informed/proficient person (NGS Citation2012). In light of current constructivist discourse, geography should be considered as an “activity that students can engage in” rather than a space for the memorization of simple place-related facts (Virranmäki, Valta-Hulkkonen, and Pellikka Citation2021). This article builds upon the premise that one possible and highly effective way to reach these goals is by fostering problem-solving skills, especially in the context of geography’s content.

Developing problem-solving skills positively influences knowledge acquisition across various disciplines. While using these skills, students are oriented toward meaning making over memorizing facts, and they gain new cognitive schemes that are geared toward adoption in new situations (Pawson et al. Citation2006). It can also encourage learners’ interest in the topic and their general engagement. Additionally, vast evidence exists on how a problem-based learning environment improves students’ deep approach to learning and their problem-solving skills (Sawyer Citation2006; Abraham et al. Citation2008; Raath and Golightly Citation2017). Furthermore, the development of problem-solving skills often leads to well-desired educational outcomes such as critical thinking, creative thinking, and decision making (Bendl and Marada Citation2021). According to Weiss (Citation2017), learners using problem-solving skills show higher levels of comprehension and awareness about real-life problems and lifelong learning. He also argues that the successful implementation of problem-solving activities (1) prevents students from experiencing passive learning, (2) prepares them for their professional, social, and personal lives, and (3) “evokes the intrinsic willingness to seek solutions actively and independently” (Weiss Citation2017, p. 2).

In accordance with Caesar et al. (Citation2016), Weiss (Citation2017), and Golightly (Citation2021), we argue that all the evidence provided above is especially relevant for the field of geography education. Since the subject of geography deals with complex human-environment relationships and various issues of the world around us, it provides a highly convenient platform for developing problem-solving skills.

Problem solving plays a crucial role in several learner-centered approaches that emerged in geography education in previous decades, such as the Thinking Through Geography project (Leat Citation2001; Nichols, Kinninment, and Leat Citation2003), problem-based learning (Spronken-Smith Citation2005), enquiry-based learning (Roberts Citation2017), and inquiry-based learning (Spronken-Smith et al. Citation2008). Furthermore, it is considered to be a key component of the main geography education goals, whether it is thinking geographically (Jackson Citation2006; GA Citation2009; Bendl and Marada Citation2021), powerful knowledge (Lambert in Stoltman, Lidstone, and Kidman Citation2015; Maude Citation2018), geographical literacy (Schoenfeldt Citation2002; NGS Citation2012), or being proficient in geography (Bednarz, Heffron, and Huynh Citation2013). Problem solving is considered a key part in all of them, and its relevance in geography is therefore immense.

It is thus highly surprising that despite its crucial importance, empirical research that focuses on whether and how problem-solving skills are being developed during geography lessons is scarce. Several studies related to implementing, enhancing, or evaluating problem-solving skills exist in various geographic academic journals (e.g., Ratinen and Keinonen Citation2011; Tonts Citation2011; Weiss Citation2017). In fact, Spronken-Smith (Citation2005), Pepper (Citation2009), Rakhudu (Citation2011), and Golightly (Citation2018) even studied students’ perceptions of the problem-solving approach. However, the fundamental question as to whether preservice teachers were led by their teachers toward problem solving during geography lessons at individual educational levels and to what extent remains unclear.

We seek to shed some light on this gap, specifically by asking preservice geography teachers about their experiences during upper secondary education. We believe that preservice geography teachers will have a fundamental role in recontextualizing geography education and shaping its image in the future (Knecht, Spurná, and Svobodová Citation2020). Understanding how their problem-solving skills were developed during their previous upper secondary studies is therefore crucial, among other things, given the necessity to adapt their university preparation to it, especially in case their problem-solving skills were not sufficiently and systematically developed. According to Bandura’s social learning theory that emphasizes the importance of role modeling (Bandura Citation1977) and other researchers’ related ideas (e.g., Alexandre Citation2009), it is also crucial to identify the teaching styles that preservice teachers were exposed to as they are likely to incline toward the same once they start teaching.

Therefore, this study aims to identify how preservice geography teachers perceive the development of their problem-solving skills during their upper secondary geography lessons and how the teaching style of their geography teacher corresponds with this development. Based on this aim, we formulated four research questions:

To what extent were preservice geography teachers, from their perspective, passively exposed to problem-solving skills in geography lessons?

To what extent were preservice geography teachers, from their perspective, actively developing problem-solving skills?

To what type of teaching style were preservice geography teachers prevailingly exposed?

How might the teaching styles that preservice geography teachers were exposed to have supported/hindered the development of their problem-solving skills?

In conclusion, based on our findings, we proposed several recommendations for geography preservice teachers’ educators and their courses.

Theoretical background

Problem-solving deconstruction and conceptual framework

While several different approaches toward defining problem solving exist (e.g., Funke Citation2003; Greiff Citation2012; Dunbar Citation2017), they usually agree that there must be a problem at the beginning of the whole process. In accordance with Mayer and Wittrock (Citation2012, p. 287) we understand problem solving as “cognitive processing directed at achieving a goal when no solution or method is obvious to the problem solver.” This way of defining problem solving allows its deconstruction into a partial set of skills that can be further operationalized and measured.

To solve a problem, the problem solver has to employ several cognitive skills. Again, there is no clear consensus as to which specific set of skills shapes the problem-solving process. For example, Golightly and Raath (Citation2015) claim that problem solving consists of comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Mayer and Wittrock (Citation2012) apply a different approach that consists of representing, planning, and executing. According to Greiff (Citation2012), problem solving consists of generating information, integrating this information into a mental model, and forming a prognosis.

In geography education, the widely accepted and domain-specific approach consists of five key skills: asking geographical questions, acquiring geographic information, organizing geographic information, analyzing geographic information, and answering geographical questions (e.g., NGS Citation2012; Bednarz, Heffron, and Huynh Citation2013). This model is in accordance with A Road Map for 21st-Century Geography Education: Geography Education Research Recommendations (2013), in which the authors added the skill “communicating geographic information” and united acquiring, organizing, and analyzing geographic information into one compound skill (Bednarz, Heffton, and Huynh 2013). For the purposes of this article, we hold on to the original version of the five skills mainly because of their already existing adaptation in the context of Czech geographical education research (Řezníčková Citation2013). A further explanation of the selected skills and their specification in geography is available in .

Table 1. Problem-solving skills in geography.

As this study focuses on the problem-solving skills development in geography education, it is also necessary to reflect on the role of the teacher in this process. Since the teacher is one of the key factors in developing these skills, it is crucial to pay attention to different teaching styles that students are exposed to and to link these styles to previously deconstructed problem-solving skills.

Different teaching styles in geography education

Many researchers have sought to examine teachers’ teaching styles, and thus, several different classifications exist (e.g., Wood 1995; Grasha Citation1996, Cooper Citation2001). These studies often function as a cornerstone of contemporary research on various teaching styles (e.g., Genc and Ogan-Bekiroglu Citation2004; Barrett, Bower, and Donovan Citation2007; Baleghizadeh and Shakouri Citation2017; Chan, Maneewan, Koul Citation2021; Fadaee et al. Citation2021). Many of these classifications share a common ground with the distinction often used by the public: “traditional” and “progressive.” This distinction is a cause of heated and polarized educational debates not only by the public but also in research (Matczynski et al. Citation2000; Meier Citation2005; Samuelsson et al. Citation2021). However, this classification has been widely contested and, by some, even disproved for its flaws, such as creating ill-defined dichotomy, oversimplification, and being too abstract. For instance, Biddulph, Lambert, and Balderstone (Citation2015) point out that one could declare “traditional” teaching to be old-fashioned, autocratic, and lacking creative opportunities, but another could praise its reliability and effectiveness in maintaining academic standards.

In the field of geography education, one of the most common classifications is Catling’s typology of teachers (2004). Researchers have applied it throughout different school levels (e.g., Puttick, Paramore, and Gee Citation2018; Knecht, Spurná, and Svobodová Citation2020; Preston Citation2015). This typology is, however, primarily concerned with teachers’ conceptions of geographical content. Since this article deals with developing problem-solving skills, a classification of teachers mainly in terms of developing these skills is required. Such a classification would allow for clearly linking the problem-solving skills development within different teaching styles of geography.

Therefore, we employ Roberts’s (Citation2006) classification of teaching styles in geography (see also Biddulph, Lambert, and Balderstone 2015). This typology is based on Roberts’s framework for looking at styles of teaching and learning in geography, and it directly frames the development of problem-solving skills within different teaching styles. This theoretical framework allows to classify the teaching styles of geography into three categories in terms of using problem-solving skills: closed, framed, and negotiated (Roberts Citation2017).

The closed style shares a common ground with many “traditionalist” traits as it emphasizes teacher-centered learning (for more, see Oyler and Becker Citation2015; Samuelsson et al. Citation2021). The teacher is considered an ultimate authority, the fount of wisdom, the leader, and the grader. The teacher is the main source of information and decides on the lesson’s organization and its content. According to Roberts (Citation2006), students are not expected to challenge what is presented. There is little space for problem-solving skills development.

Even in the framed style, the role of the teacher is still crucial as they frame the whole lesson. Nevertheless, the teacher also gives the students enough space to formulate their own questions and to interpret the presented results. In terms of the potential for problem-solving skills development, the framed style lies between the closed and negotiated ones.

The third and most student-centered style of teaching is the negotiated style. In many aspects, this style has a significant overlap with the “progressive” style of teaching (see Matczynski et al. Citation2000; Chicoine Citation2004; Meier Citation2005; Samuelsson et al. Citation2021). The emphasis during the lesson is on the students’ activity, including problem-solving skills development. The teachers function mainly as facilitators and guides, and they employ a different mixture of methods. The problem areas that the students find important can be considered as starting points for teaching rather than traditionally taught content, and thus, learners might be actively involved in determining the content of education. The emphasis is on fostering desired skills, attitudes, and values.

Problem-solving skills and different teaching styles in Czech geographical education: A brief overview

Twenty years ago, a key change in the Czech curriculum was introduced to redirect from memorizing big amounts of facts toward acquiring competencies, skills, attitudes, and values (Řezníčková Citation2009). This reform thus aimed to implement competency-based curricula, in which each subject should contribute to the acquisition of key competencies of a common interdisciplinary character, such as problem solving (Research Institute of Education Citation2007). The Czech curriculum has undergone several changes since then, but the emphasis on competencies as the main interdisciplinary educational outcome of education, including problem solving, has stayed intact. In fact, this emphasis is currently strengthening under the ongoing “big revisions” of the curriculum (MEYS Citation2021).

Although all Czech curricular documents emphasize problem-solving skills, their development in the classroom seems to be unsatisfactory. Based on the scant available data about the state of Czech geography education, it is possible to claim that encyclopedism and memorizing facts still prevail over developing skills and competencies such as problem solving (Czech School Inspectorate CSI Citation2019; Bendl and Marada Citation2021). Thus, the closed teaching style prevails over the negotiated one.

According to Bandura (Citation1977), Park and Ertmer (Citation2007), Alexandre (Citation2009), and others, it is short-sighted to ask geography preservice teachers to lead their future students toward geographical thinking and problem solving if they were not exposed to it themselves. Thus, it is crucial to map how and the extent to which preservice geography students have been developing their problem-solving skills during upper secondary education.

Methods

Respondents

The sample comprised 256 early preservice teachers from first- and second-year bachelor’s degree programs in geography education. It included students from two Czech universities: (names of universities anonymized for the purposes of peer-review process). This study focused on early preservice teachers as they are more likely to remember their upper secondary geography lessons. provides the basic demographics of the respondents. All the respondents took geography lessons during their upper secondary studies, even though the average number of geography lessons per week varied from two hours per week during all four years to two hours per week during only one year. This number depends on the type of school and its inner-school educational program.

Table 2. Overview of the sample (n = 256).

Research tool

To answer the research questions stated above, we developed a 32-item questionnaire that consists of three main parts.

The first part consisted of 10 items collecting key demographic and introductory information about the sample (). The second (main) part of the questionnaire consisted of 10 statements. These statements were created in accordance with NGS (Citation2012), Bednarz, Heffron, and Huynh (Citation2013), and Řezníčková (Citation2013) as all these sources thoroughly characterize each problem-solving skill (NGS Citation2012) in the context of geography education. Based on the study of Řezníčková (Citation2013), the authors translated and operationalized the five problem-solving skills into specific statements in the questionnaire (see examples in ). Given a substantial difference between developing the problem-solving skills passively and actively (CSI Citation2019), each statement consisted of two variations: one for the passive development of the specific problem-solving skill and the other for the active development of the skill (). For instance, there is a difference if the students only watch the teacher analyze information from a map and learn from it or if they are given the chance to analyze the information themselves. It is essential to explore this difference as several studies suggest that active development is being widely untapped/unemployed, especially in the Czech educational context (PISA Citation2018; CSI Citation2019). It was crucial that the respondents could differentiate between these distinctions, and therefore, the first author always explained it when introducing the questionnaire.

Table 3. An example of statements comprising specific problem-solving skill.

The respondents were asked to agree or disagree with the given statements using a six-point Likert scale (). An even-numbered forced-choice scale was adopted as we wanted the respondents to choose either an agreement or a disagreement option. In addition, we wanted to avoid the situation in which the midpoint is being used by the respondents as a “dumping ground” (Chyung et al. Citation2017).

To obtain more complex information, it was crucial to ask not only about the exposure to problem-solving skills but also about the teachers’ teaching style. We believe that the identification of different teaching styles would provide deeper insights into how the problem-solving skills are developed. For that reason, we added a third (explanatory) part of the questionnaire, asking about various teaching styles that students were exposed to. These teaching styles were linked with specific problem-solving skills within Roberts’s (Citation2006) classification.

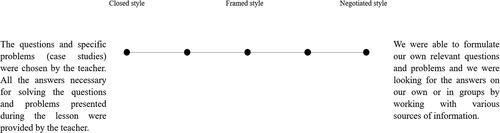

The explanatory part of the questionnaire comprised eight items related to the teaching styles defined in the theoretical part. The teaching style of the respondents’ geography teacher was identified based on items related to the teaching form, methods, content of the lessons, and students’ evaluation. There were two statements within each item, and the respondents had to choose an option on a five-point Likert scale that would reflect their teacher’s teaching style the most (see an example in ). In this part, the respondents could express a neutral opinion as we knew from the pilot study that the respondents were familiar with the topic and they clearly understood the statements and thus were not expected to misuse the midpoint (Chyung et al. Citation2017). Each statement on the left stood for the closed style of teaching geography, while each statement on the right symbolized the negotiated teaching style ().

Figure 1. An example of one item comprising “content of learning.” Note: The names of the styles were not incorporated in the questionnaire.

To ensure the research tool’s validity, four geography education experts from different Czech universities reviewed the content of the questionnaire (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). The questionnaire content was repeatedly adjusted based on the received comments. Furthermore, we conducted a pilot study followed by interviews with 15 respondents. This helped identify the problematic aspects of the research tool; specifically, a few items were modified because of low comprehensibility and general difficulty. The Cronbach’s alpha reliability statistics of the items on the questionnaire yielded a high coefficient of 0.87. The study was carried out in accordance with the recommendations provided by the ethical committees of both universities with which the authors are affiliated. Participation in the study was voluntary, and the anonymity of the acquired data was guaranteed.

Data collection and analysis

The data was collected between October and November 2022. The first author explained the instructions to the respondents in person as he distributed the questionnaire during their university lectures.

The collected data was subjected to descriptive and inferential analysis; namely, paired t-tests and cluster analysis were performed. Furthermore, the latter was employed to classify the preservice geography teachers according to the different teaching styles they had been exposed to. In the first step, we determined an appropriate number of clusters based on the theoretical background (three). In the second step, we employed a hierarchical cluster analysis based on the “between-groups linkages” method and squared Euclidean distance. The analysis was held in accordance with the study of Aldenderfer and Blashfield (Citation1985). The statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25.0 (IBM).

Results

Perceived development of problem-solving skills

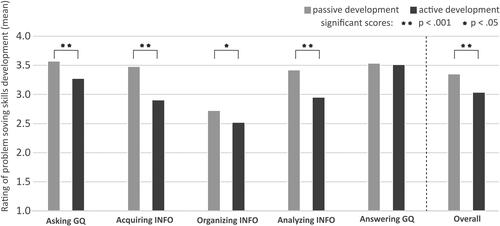

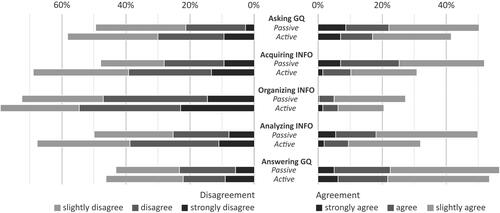

In all the problem-solving skills, the preservice teachers’ perception of active development scored lower than that of their passive development (see ). In total, only 52 out of the 256 respondents reported that they have been exposed to the active development of problem-solving skills, slightly more than to their passive development. A significant difference in the average scores for the passive and active development of all five problem-solving skills (M = 3.44, SD = 0.94, and M = 3.02, SD = 0.92, respectively) was identified t(255) = 7.48, p < 0.001.

Regarding individual problem-solving skills, our study found a statistically significant difference between passive and active development within the skills of asking geographical questions, acquiring information, organizing information, and analyzing information. Therefore, only in the “answering geographical questions” the difference between its passive (M = 3.56, SD = 1.27) and active (M = 3.53, SD = 1.34) development was not statistically significant, t(255) = 0.44, p > 0.05.

In general, the skill “organizing information” obtained the lowest scores among the five monitored problem-solving skills. This applies for both its passive and active development (). On the other hand, the respondents expressed the strongest agreement within the passive exposition to the skill “asking geographical questions.” While this is the highest agreement among the problem-solving skills, the value is still rather low considering the selected scale (see ). The results also suggest that while the respondents were exposed to asking geographical questions, more frequently, it was the teacher who asked and formulated them.

Figure 2. Difference between passive and active development of problem-solving skills from the perspective of preservice geography teachers.

To gain deeper insights into preservice teachers’ perceptions of their problem-solving skills development, we compared the percentages of preservice teachers choosing the given option on the Likert scale (see ). For example, while the means for asking and answering geographical questions were almost identical (), the percentage of preservice teachers who at least slightly agreed that they had been exposed to the skill of answering geographic questions is higher than that for asking geographic questions. Nevertheless, when comparing preservice teachers with definite opinions (strongly dis/agree), the results are in favor of the skill of asking geographic questions. In general, the least frequently used option in terms of the Likert scale was “strongly agree,” especially for active development, while the majority of respondents oscillated between the middle options (“slightly disagree” and “slightly agree”). Only in the case of the skill of organizing information, the majority of preservice teachers disagreed with both the passive and active development of this skill during upper secondary education, which supports the previously mentioned results.

The development of problem-solving skills within different teaching styles

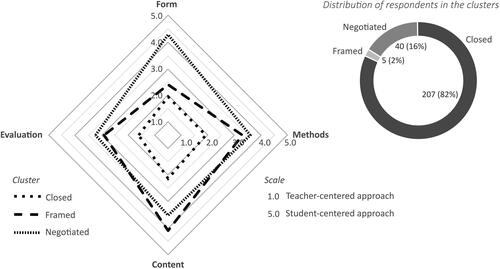

To address the third research question, we aimed to classify and further analyze the respondents based on the teaching style they were predominantly exposed to. The cluster analysis divided the respondents into three predetermined clusters (teaching styles)—i.e., negotiated, closed, and framed. The distribution of the respondents in these clusters provided empirical evidence for the persisting dominance of the closed style of teaching geography (see ). The respondents reported that they had been exposed mainly to teacher-centered teaching with an emphasis on description, encyclopedism, and the plain learning of facts, while the development of problem-solving skills remained rather idle.

We further interpreted these teaching styles (meaning clusters) in regard to four investigated key aspects of teaching: the form of teaching, methods, content, and evaluation. In terms of these aspects, the identified difference between the closed and negotiated clusters of preservice teachers was crucial, while the framed cluster oscillated between them ().

Cluster 1, representing the negotiated teaching style, consists of 40 respondents. Thus, only 16% of the sample claimed they had dominantly experienced the negotiated style of teaching geography. Based on the results, the form of these lessons was highly constructivist as the teacher emphasized their students’ work. The respondents reported that they were often asked to formulate their own research questions and to work with the data and information on their own or in groups. They also claimed that the teacher spent more time in the role of facilitator than lecturer and that they used various teaching methods. In terms of evaluation, the respondents’ answers indicated that it also focused on providing feedback on skills and values.

Cluster 2 consists of 207 respondents and is thus dominant in terms of the respondents’ distribution (). It is an example of a teacher-centered, closed style of teaching geography. The results indicate that during these lessons, the students were predominantly sitting and listening to the teacher lecturing about topics and regions, and the teacher did not require any active involvement from them. The respondents reported that the teacher functioned as the main source of information and that they were asked to memorize/learn it. The teacher was using normative means of assessment for the students.

The smallest identified cluster is Cluster 3, the framed teaching style. This cluster had rather low scores in the form of teaching (similar to the closed style), while the scores of methods and content were rather high (comparable with the negotiated teaching style; see ). This means that these preservice teachers experienced mainly a frontal form of teaching during their upper secondary geography education. Thus, mainly the teachers framed the whole lesson, but it was through engaging issues and case studies rather than through a classical regional approach. While the respondents reported that they often faced the frontal forms of teaching, they simultaneously agreed that the teacher gave them enough time to actively work on their own or in groups. They claimed that they were given plenty of time to work with various resources to answer questions framed by the teacher.

The final research question investigated the impact of the teaching style to which preservice geography teachers were exposed on the development of their problem-solving skills. The results suggest that while the negotiated cluster slightly agreed that their problem-solving skills were being developed, the most populous (closed) cluster disagreed (). Furthermore, the negotiated cluster showed almost no difference between passive and active development, t(39) = 0.50, p > 0.05, while the closed one did, and the difference was significant, t(206) = 8.58, p < 0.001. No difference was also found between the active and passive development of the framed style, which, in terms of its means, oscillated between the closed and negotiated styles (see ). However, the results related to the framed style need to be interpreted with caution as this cluster consists of a small number of respondents. The biggest difference among the clusters in individual skills categories development was in the active development of asking geographical questions, while the smallest was in the passive development of answering geographical questions.

Table 4. Problem-solving skills development in the identified clusters.

Since 82% of the students claimed that they had faced the closed style of teaching geography and because the majority of them believed that their problem-solving skills were not being developed, it is necessary to discuss possible solutions to this unfavorable situation.

Discussion, recommendations, and limitations

For further discussion and future inquiry two findings from this study are crucial: (1) preservice geography teachers’ perception of the insufficient development of problem-solving skills during upper secondary geography education and (2) the influence of the prevailing closed teaching style on this development.

Insufficient development of problem-solving skills in the context of prevalent closed teaching style

Despite the articulated importance of problem-solving skills, our findings suggest that preservice geography teachers perceive that their problem-solving skills during upper secondary schooling are not being developed accordingly and that once they encounter problem solving, they are more often in the role of a passive audience. The teacher asks questions and then provides the information and solutions. The only exception in this study was the skill of answering geographical questions, where the difference between its passive and active development was not statistically significant. Given the respondents’ answers related to the teaching style they were exposed to, they might have stated that they actively developed this skill as they were used to answering the teacher’s questions. However, these questions may not have been problem oriented; thus, their answers did not require any problem-solving process but only previously memorized knowledge.

Although active development is more effective than mere passive exposure to skills learning (Bednarz, Heffron, and Huynh Citation2013), only one-fifth of the sample reported that they actively developed problem-solving skills slightly more than they were passively exposed to them. The explanatory part of the questionnaire supports these findings, given that most of the sample believe they were exposed to the closed style of teaching geography. This means having fewer opportunities to practice and develop the desired problem-solving skills (Roberts Citation2017). These results provide partial empirical evidence to often articulated concerns (Alexandre Citation2009; van der Schee Citation2014; Knecht and Hofmann Citation2020) that geography is still being taught as a plain descriptive subject about different regions and states in the world. The results also support the general findings from CSI (Citation2019) stating that Czech students are exposed mainly to teacher-centered approaches to learning.

Several explanations for the prevalence of the closed style of teaching in Czechia exist. First, the conception of geography as a descriptive subject based on memorization has deep roots in the history of the Czech schooling system (Řezníčková Citation2015). These conceptions were strengthened during the Communist era (1948–1989), in which understanding geography as a school subject offering space for the discussion of various problems and developing students’ problem-solving skills was in direct contradiction with the regime’s ideology.

To put things in a broader perspective, the majority of geography teachers in Czechia (whose average age is relatively high, 50 years) experienced the closed style of teaching, which repressed the concept of geography as a subject challenging students’ minds with various problems. According to Bandura (Citation1977), Alexandre (Citation2009), Brooks (2016), and others, these teachers would naturally tend to use the same conceptions of geography they themselves were exposed to.

Furthermore, recent studies have proven that lessons taught by qualified teachers show significantly higher student activity (CSI Citation2019). Despite this, 25% of geography teachers at Czech upper elementary schools still do not have the appropriate subject approbation (CSI Citation2019). In addition to this, teachers nowadays face many new challenges that require a lot of time and effort, such as a desire to save some time; it is simply much less time-consuming to prepare a lesson based on the closed style of teaching. Even though this discussion focused on the Czech context, a similar state of problem-solving skills can be expected in other countries as well, especially in countries where descriptive and teacher-centered approaches to teaching geography prevail.

All the abovementioned aspects might, to some extent, contribute to early preservice teachers’ conceptions of geography as a mainly descriptive discipline based on the plain memorization of different places and regional characteristics. Surprisingly, the respondents reported high personal interest in these descriptive geographies. The fact that they enjoy the subject despite its descriptive character might even strengthen these conceptions. However, these deeply rooted conceptions are far from curriculum designers’ and geography education experts’ and educators’ conceptions. When students join the university to become geography teachers, their expectations are severely challenged (Knecht, Spurná, and Svobodová Citation2020). This creates a wide gap that needs to be bridged.

Recommendations

To enhance the development of problem-solving skills during upper secondary geography education and consequently shift the conceptions of geography as a simple descriptive discipline toward a respected discipline fostering desired problem-solving skills, we suggest several recommendations:

Future educators need to be aware of who their students are—e.g., which conception of geography teaching is the most appealing to them and what teaching style is the most familiar to them.

Many research tools and course methods diagnosing students’ conceptions of geography and geography teaching exist (e.g., Catling Citation2004; Mitchell Citation2018; Knecht, Spurná, and Svobodová Citation2020). The content of the university courses as well as the forms and methods used in them should be, to some extent, tailored to these diagnostic tests’ results. For example, if the research tool diagnoses high exposure to the closed style, it is the educator’s task to familiarize their students with the other styles.

During their university studies, preservice geography teachers should experience constructivist strategies of teaching (e.g., the negotiated style of teaching) to better understand its benefits and to accept it on their own as well as to various conceptions of geography teaching.

This study provides empirical evidence that once preservice teachers join the university, they often perceive geography as a solely descriptive academic subject. In many cases, preservice teachers even face the purely closed style of teaching throughout their whole university studies, and they have no impulse to think about different approaches (see also Mitchell Citation2018). Thus, there is no stimulus for change. We believe that students need to be properly introduced to different teaching styles and conceptions of geography teaching as well as experience them during various courses. Most importantly, educators should provide them with enough time to explore and try out these styles on their own.

Relevant lifelong courses should be offered, various policy makers should emphasize their importance and motivate the current teachers to attend them.

To improve the situation, rather than wait for preservice teachers to slowly bring the necessary changes to geography education in the future, current teachers must be encouraged to attend meaningful lifelong courses. This recommendation, unlike the previous two, requires serious systematic and institutional changes in some countries. Universities and the private sector already often provide such courses, however, secondary and elementary teachers are generally not motivated and encouraged enough to attend them (e.g., Kolenc-Kolnik Citation2010; Nabhani and Bahous Citation2010; Wermke Citation2011). Moreover, teachers need bigger institutional support as there is often no time for them to attend these lifelong courses.

We believe that following these recommendations will lead to higher development of problem-solving skills and consequently to improving the image of geography as a school subject.

Limitations of the study

Despite the sufficient size of the research sample (Israel Citation1992), it is important to note other limitations that come with the selected research design. First and foremost, the results of this study are based on preservice geography teachers’ perceptions of problem-solving skills development and not the reality of such development. On the other hand, analyzing students’ perceptions of problem-solving skills development is crucial as it can influence how they will develop these skills once they are teachers themselves. Furthermore, the employed research tool can be used in future research, especially for comparing the perceptions of problem-solving skills development with the school reality. It is also important to acknowledge the reduction that occurred when we operationalized each problem-solving skill into two brief and comprehensible statements. However, this was necessary to obtain a sufficient number of respondents willing to answer the questionnaire. The results should also be interpreted in the context of the solely quantitative design of the study. A challenge for future research will be to analyze the perceptions of preservice geography teachers’ development of problem-solving skills in terms of qualitative methods as this would provide a deeper understanding of our findings.

Conclusion

Despite the crucial importance of fostering problem-solving skills, this article provides empirical evidence that preservice geography teachers perceive that their problem-solving skills were insufficiently developed during their upper secondary education. Furthermore, future geography teachers believe they have mainly experienced the closed teaching style. While these thoughts might not be new to the community of geography education, they are a reality in many countries, especially in the context of the currently declining image of geography as a school subject. Thus, it is crucial to address this situation and take the necessary action to improve it. This will not be an easy task since the respondents who were dominantly exposed to the closed style of teaching geography with no or few signs of problem-solving skills development actually showed such a high personal interest in these geographies that they decided to become teachers of this subject. We hope that these research findings related to future geography teachers will stimulate and deepen the conversation that goes beyond the opinion of one person or group to consider the future of geography education.

Acknowledgments

We would like to express our thanks to the peer reviewers and editors of this journal for valuable suggestions that helped us to improve this manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomáš Bendl

Tomáš Bendl is a PhD candidate in geography education at Charles University in Prague and a future geography teachers educator at the Technical University of Liberec. His major research interests concern geographical thinking and problem solving in geography education.

Miroslav Marada

Miroslav Marada is a docent at Charles University in Czechia. His teaching and research activities are focused mainly on conceptions and content of curricular reforms and on skills development in geography education.

Lenka Havelková

Lenka Havelková is an assistant professor at Charles University in Czechia. Her teaching and research activities are centered on educational cartography. She has developed a particular research interest in students’ strategies for solving tasks with maps and misconceptions that influence students’ understanding and use of maps. Moreover, she enjoys exploring and employing various methodological approaches from which geographical education research can benefit, such as eye-tracking experiments and conceptual tests.

References

- Abraham, R. R., P. Vinod, K. Kamath, K. Asha, and K. Ramnarayan. 2008. Learning approaches of undergraduate medical students to physiology in a non-PBL and partially PBL-oriented curriculum. Advances in Physiology Education 32 (1):35–37. doi: 10.1152/advan.00063.2007.

- Aldenderfer, M. S., and R. K. Blashfield. 1985. Cluster analysis: Quantitative applications in the social sciences. California: SAGE.

- Alexandre, F. 2009. Epistemological awareness and geographical education in Portugal: The practice of newly qualified teachers. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 18 (4):253–259. doi: 10.1080/10382040903251067.

- Baleghizadeh, S., and M. Shakouri. 2017. Investigating the relationship between teaching styles and teacher self-efficacy among some Iranian ESP university instructors. Innovations in Education and Teaching International 54 (4):394–402. doi: 10.1080/14703297.2015.1087329.

- Bandura, A. 1977. Social learning theory. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

- Barrett, K., L. B. Bower, and N. C. Donovan. 2007. Teaching styles of community college instructors. American Journal of Distance Education 21 (1):37–49. doi: 10.1080/08923640701298738.

- Bednarz, S. W., S. Heffron, and N. T. Huynh. 2013. A road map for 21st-century geography education: Geography education research. Washington DC: Association of American Geographers.

- Bednarz, S. W., S. G. Heffron, and M. Solem. 2014. Geography standards in the United States: Past influences and future prospects. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (1):79–89. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2013.858455.

- Bendl, T., and M. Marada. 2021. Kritické myšlení v geografickém vzdělávání: Je geografické myšlení kritické? Geografie 126 (4):371–391.

- Béneker, T., H. Palings, and U. Krause. 2015. Teachers envisioning future geography education at their schools. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (4):355–370. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2015.1086102.

- Biddulph, M., D. Lambert, and D. Balderstone. 2015. Learning to teach geography in the secondary school: A companion to school experience. London: Routledge.

- Caesar, M. I. M., R. Jawawi, R. Matzin, M. Shahrill, J. H. Jaidin, and L. Mundia. 2016. The benefits of adopting a problem-based learning approach on students’ learning developments in secondary geography lessons. International Education Studies 9 (2):51–65. doi: 10.5539/ies.v9n2p51.

- Catling, S. 2004. An understanding of geography: The perspectives of English primary trainee teachers. GeoJournal, 60 (2):149–158

- Chan, S., S. Maneewan, and R. Koul. 2021. Teacher educators’ teaching styles: Relation with learning motivation and academic engagement in pre-service teachers. Teaching in Higher Education, 22 pp. doi: 10.1080/13562517.2021.1947226.

- Chang, C. H. 2014. Is Singapore’s school geography becoming too responsive to the changing needs of society? International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 23 (1):25–39. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2013.858405.

- Chicoine, D. 2004. Ignoring the obvious: A constructivist critique of a traditional teacher education program. Educational Studies 36 (3):245–263. doi: 10.1207/s15326993es3603_4.

- Chyung, S. Y., K. Roberts, I. Swanson, and A. Hankinson. 2017. Evidence-based survey design: The use of a midpoint on the Likert scale. Performance Improvement 56 (10):15–23. doi: 10.1002/pfi.21727.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research methods in education. New York: Routledge.

- Cooper, T. C. 2001. Foreign language teaching style and personality. Foreign Language Annals 34 (4):301–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2001.tb02062.x.

- CSI. 2019/. Rozvoj přírodovědné gramotnosti na základních a středních školách ve školním roce Prague: Czech School Inspectorate.

- Dunbar, K. 2017. Problem solving. In A companion to cognitive science, ed. W. Bechtel and G. Graham, 289–298. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Fadaee, E., A. Marzban, S. N. Karimi, and Y. Khajavi. 2021. The relationship between autonomy, second language teaching styles, and personality traits: A case study of Iranian EFL teachers. Cogent Education 8 (1):1–27. doi: 10.1080/2331186X.2021.1881203.

- Favier, T. T., and J. van der Schee. 2012. Exploring the characteristics of an optimal design for inquiry-based geography education with geographic information systems. Computers & Education 58 (1):666–677. doi: 10.1016/j.compedu.2011.09.007.

- Funke, J. 2003. Problemlösendes Denken. Stuttgart: Kohlhammer.

- Genc, E., and F. Ogan-Bekiroglu. 2004. Patterns in teaching styles of science teachers in Florida and factors influencing their preferences. Reports-Research, 22 pp.

- Geographical Association. 2009. A different view: A manifesto from the geographical association. Sheffield: Geographical Association.

- Golightly, A. 2018. The influence of an integrated PBL format on geography students’ perceptions of their self-directedness in learning with the implementation of integrated problem-based learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (3):460–478. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2018.1463974.

- Golightly, A. 2021. Self- and peer assessment of preservice geography teachers’ contribution in problem-based learning activities in geography education. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 30 (1):75–90. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2020.1744242.

- Golightly, A., and S. Raath. 2015. Problem-based learning to foster deep learning in pre-service geography teacher education. Journal of Geography 114 (2):58–68. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2014.894110.

- Grasha, A. 1996. Teaching with Style: A Practical Guide to Enhancing Learning by Understanding Teaching and Learning Styles. Pittsburgh: Alliance Publishers.

- Greiff, S. 2012. Individualdiagnostik komplexer Problemlösefähigkeit. Münster: Waxmann.

- Israel, G. D. 1992. Determining sample size. Fact sheet PEOD-6 in program evaluation and organizational development. Florida: University of Florida.

- Jackson, P. 2006. Thinking geographically. Geography 91 (3):199–204. doi: 10.1080/00167487.2006.12094167.

- Knecht, P., and E. Hofmann. 2020. Jak dál ve výuce regionální geografie na základních školách? Informace ČGS 39 (2):14–23.

- Knecht, P., M. Spurná, and H. Svobodová. 2020. Czech secondary pre-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 44 (3):458–473. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2020.1712687.

- Kolenc-Kolnik, K. 2010. Lifelong learning and the professional development of geography teachers: A view from Slovenia. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 34 (1):53–58.

- Lane, R., and T. Bourke. 2017. Possibilities for an international assessment in geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 26 (1):71–85. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2016.1165920.

- Leat, D. 2001. Thinking through geography. Cambridge: Chris Kington Publishing.

- Matczynski, T. J., J. F. Rogus, T. J. Lasley, and E. A. Joseph. 2000. Culturally relevant instruction: Using traditional and progressive strategies in urban schools. The Educational Forum 64 (4):350–357. doi: 10.1080/00131720008984780.

- Maude, A. 2016. What might powerful geographical knowledge look like? Geography 101 (2):70–76. doi: 10.1080/00167487.2016.12093987.

- Maude, A. 2018. Geography and powerful knowledge: A contribution to the debate. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 27 (2):179–190. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2017.1320899.

- Mayer, R., and M. Wittrock. 2012. Problem solving. In: Handbook of educational psychology, ed. A. P. Alexander, and H. P. Winne, 287–305. New York: Routledge.

- Meier, C. 2005. The development and application of progressive education in the Netherlands and some implications for South Africa. Africa Education Review 2 (1):75–90. doi: 10.1080/18146620508566292.

- MEYS. 2021. Strategy for the education policy of the Czech Republic up to 2030+. Praha: Ministry of Education, Youth and Sports.

- Mitchell, J. T. 2018. Pre-service teachers learn to teach geography: A suggested course model. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 42 (2):238–260. doi: 10.1080/03098265.2017.1398719.

- Nabhani, M., and R. Bahous. 2010. Lebanese teachers’ views on continuing professional development. Teacher Development 14 (2):207–224. doi: 10.1080/13664530.2010.494502.

- NGS. 2012. National geography standards: Geography for life. Washington: National Council for Geographic Education.

- Nichols, A., D. Kinninment, and D. Leat. 2003. More thinking through geography. Cambridge: Chris Kington Publishing.

- Oyler, C., and J. Becker. 2015. Teaching beyond the progressive–traditional dichotomy: Sharing authority and sharing vulnerability. Curriculum Inquiry 27 (4):453–467.

- Park, S. H., and P. A. Ertmer. 2007. Impact of problem-based learning (PBL) on teachers’ beliefs regarding technology use. Journal of Research on Technology in Education 40 (2):247–267. doi: 10.1080/15391523.2007.10782507.

- Pawson, E., E. Fournier, M. Haigh, O. Muniz, J. Trafford, and S. Vajoczki. 2006. Problem-based learning in geography: Towards a critical assessment of its purposes, benefits and risks. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 30 (1):103–116. doi: 10.1080/03098260500499709.

- Pepper, C. 2009. Problem-based learning in science. Issues in Educational Research 19 (2):128–141.

- PISA. 2018. Mezinárodní šetření PISA 2018. Praha: Česká školní inspekce.

- Preston, L. 2015. Australian primary in-service teachers’ conceptions of geography. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (2):167–180.

- Puttick, S., J. Paramore, and N. Gee. 2018. A critical account of what “geography” means to primary trainee teachers in England. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 27 (2):165–178.

- Raath, S., and A. Golightly. 2017. Geography education students’ experiences with a problem-based learning fieldwork activity. Journal of Geography 116 (5):217–225. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2016.1264059.

- Rakhudu, M. A. 2011. Experiences of North-West University nursing students in problem-based learning (PBL). Journal of Social Sciences 29 (1):81–89. doi: 10.1080/09718923.2011.11892958.

- Ratinen, I., and T. Keinonen. 2011. Student-teachers’ use of Google Earth in problem-based learning. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 20 (4):345–358. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2011.619811.

- Research Institute of Education. 2007. Framework education programme for secondary general education. Praha: Research Institute of Education.

- Roberts, M. 2006. Geographical enquiry. In: Secondary geography handbook, ed. D. Balderstone. Sheffield: The Geographical Association.

- Roberts, M. 2017. Planning for enquiry. In: The handbook of secondary geography, ed. M. Jones, 48–59. Sheffield: The Geographical Association.

- Řezníčková, D. 2009. The transformation of geography education in Czechia. Geografie 114 (4):316–331. doi: 10.37040/geografie2009114040316.

- Řezníčková, D. 2013. Dovednosti žáků ve výuce biologie, geografie a chemie. Praha: Nakladatelství P3K.

- Řezníčková, D, et al. 2015. Didaktika geografie: Proměny identity oboru. In: Oborové didaktiky: Vývoj, stav, perspektivy, ed. I. Stuchlíková, and T. Janík, 259–280. Brno: Masarykova univerzita.

- Samuelsson, J., N. Gericke, C. Olin-Scheller, and Å. Melin. 2021. Practice before policy? Unpacking the black box of progressive teaching in Swedish secondary schools. Journal of Curriculum Studies 53 (4):482–499. doi: 10.1080/00220272.2021.1881166.

- Sawyer, R. K. 2006. The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Schoenfeldt, M. 2002. Geographic literacy and young learners. The Educational Forum 66 (1):26–31. doi: 10.1080/00131720108984796.

- Solem, M., D. Lambert, and S. Tani. 2013. GeoCapabilities: Toward an international framework for researching the purposes and values of geography education. Review of International Geographical Education Online 3 (3):204–219.

- Spronken-Smith, R. 2005. Implementing a problem-based learning approach for teaching research methods in geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 29 (2):203–221. doi: 10.1080/03098260500130403.

- Spronken-Smith, R., J. Bullard, R. Waverly, C. Roberts, and A. Keiffer. 2008. Where might sand dunes be on Mars? Engaging students through inquiry-based learning in geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education 32 (1):71–86. doi: 10.1080/03098260701731520.

- Stoltman, J., J. Lidstone, and C. Kidman. 2015. Powerful knowledge in geography: IRGEE editors interview Professor David Lambert, London Institute of Education, October 2014. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 24 (1):1–5. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2015.987435.

- Tonts, M. 2011. Using problem-based learning in large undergraduate fieldwork classes: An Australian example. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education 20 (2):105–119. doi: 10.1080/10382046.2011.564784.

- van der Schee, J. 2014. Looking for an international strategy for geography education. Journal of Research and Didactics in Geography 3 (1):9–13.

- Virranmäki, E., K. Valta-Hulkkonen, and A. Pellikka. 2021. Geography curricula objectives and students’ performance: Enhancing the student’s higher-order thinking skills? Journal of Geography 120 (3):97–107. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2021.1877330.

- Weiss, G. 2017. Problem-oriented learning in geography education: Construction of motivating problems. Journal of Geography 116 (5):206–216. doi: 10.1080/00221341.2016.1272622.

- Wermke, W. 2011. Continuing professional development in context: Teachers’ continuing professional development culture in Germany and Sweden. Professional Development in Education 37 (5):665–683. doi: 10.1080/19415257.2010.533573.

- Young, M. 2009. Education, globalisation, and the “voice of knowledge.” Journal of Education and Work 22 (3):193–204. doi: 10.1080/13639080902957848.