Abstract

Expressive cultural activities, such as viewing visual art, drama, or dance, are perceived as beneficial to individuals and societies, justifying public funding. However, not everyone benefits and participates equally. We intentionally sampled infrequent and frequent attendees among young adults in the Netherlands. Results indicated that infrequent and frequent attendees differed in expressive cultural activity constraints and socialization, though not on demographic background. Their cultural, social, and emotional experience through self-report and physiological data revealed no significant differences between the groups’ experience of a dramatic performance. These outcomes suggest that, as an example of expressive cultural activity, a dramatic performance experience can be equally emotionally beneficial to frequent and infrequent attendees, an important prerequisite to broader appeal and intergroup contact. Implications of the use of physiological data in leisure experience research are discussed.

In recent decades there has been a strong focus on the benefits of leisure activities for the development of young people, both in academic literature and in government policy (e.g., Driver et al., Citation1991; Shaw & Dawson, Citation2001). Participation in leisure activity domains such as sports and arts is believed to foster health and social inclusion (Ekholm & Lindström Sol, Citation2019; Long & Bianchini, Citation2019). The acclaimed positive social impact of expressive cultural activities, such as viewing visual art, drama or dance, for individuals and society has become institutionalized in European policies and continues to fuel public subsidies (Belfiore & Bennett, Citation2008).

However, not everyone benefits equally from these policies. Socio-economic influences partly determine participation, and some groups participate significantly less in expressive cultural activities than others (Falk & Katz-Gerro, Citation2016; Feder & Katz-Gerro, Citation2012). Floyd (Citation2014) asserts that leisure researchers have a moral imperative to address these differences in a way that reduces barriers to leisure participation. In the social psychological approach to leisure, researchers are concerned with individuals’ perceptions of their social environment in leisure contexts. One of the main lines of inquiry within this approach has been the relationship between barriers to leisure participation (Godbey et al., Citation2010), usually conceptualized as leisure constraints, and behavioral outcomes such as involvement and loyalty (Alexandris, Citation2013; Carroll & Alexandris, Citation1997; Godbey et al., Citation2010; Hubbard & Mannell, Citation2001). Missing from this literature is the link between constraints and the experience itself, especially emotions, which are argued to be at the core of leisure experiences (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019). If a leisure experience is not emotionally valuable, higher-order constraints may not be negotiated (Godbey et al., Citation2010), ultimately calling public funding of such experiences into question.

Our study compares frequent and infrequent participants in expressive cultural activities in terms of their past behavior, constraints, and experiences, at dramatic performances in a theater, and uncovers the specific constraints, if any, that affect their experiences. Within their experiences, we triangulate self-report measures of emotion with psychophysiological measures, an approach that is relatively novel in leisure research. To frame this inquiry, we review three theoretical areas: intergroup contact theory, which served as an inspiration for the topic of our study; hierarchical leisure constraints and socialization explanations of leisure activity participation, and the theory of structured leisure experiences.

Literature review

The practical impetus for our study is the political debate around public funding of expressive cultural activities. In the Netherlands, as in many European countries, this funding is substantial. As European countries undergo accelerating demographic change, there is pressure on institutions that design and provide expressive cultural activities––theaters, music halls, and museums––to remain broadly relevant to rapidly changing populations. Furthermore, social groups which do not feel addressed by public institutions may become marginalized, leading to social fragmentation and polarization. In the social psychology literature this distinction in social groups is often referred to as in- versus out-groups (Kleiber et al., Citation2011). According to Volker et al. (Citation2014) members of separate social groups need to have opportunities to interact with each other to gain mutual understanding. The importance of intergroup interaction is highlighted by intergroup contact theory (Pettigrew & Tropp, Citation2008). This theory states that “intergroup contact typically diminishes intergroup prejudice” (p. 922). Through intergroup contact, prejudice is reduced by increased knowledge of, and empathy for, the out-group (Pettigrew & Tropp, Citation2008). In other words, social interaction between different groups fosters mutual understanding and can help reduce social fragmentation.

Continued public funding for expressive cultural activities in the Netherlands is based on an assumption that they offer widely relevant leisure experiences, and as a result, create a context for intergroup contact (Kuipers & Van den Haak, Citation2014; Ministry of Education Culture & Science, Citation2014; Van den Broek, Citation2013). This is not necessarily the case, however. A study on football sport participation in the Netherlands produced a contradictory finding, wherein contact caused social fragmentation to blossom into all-out conflict (Krouwel et al., Citation2006). This apparent contradiction implies that contact between social groups may have divergent consequences, and it is the experience which matters (Hewstone, Citation2015). If the experiences of participants who infrequently attend expressive cultural activities are not positive, then the most fundamental category of leisure constraints––not wanting to, or finding any appeal, in the activities––will prevent participation. Thus, policy goals of reaching broad audiences, let alone intergroup contact, must be informed by the experiences of frequent as well as infrequent participants. The quality of these experiences is a prerequisite to fulfilling the stated goals of public funding for expressive cultural activities.

Unfortunately, research comparing in- and out-groups’ experiences of expressive cultural activities are scarce and inevitably retrospective in nature (Shinew et al., Citation1995) and thus subject to substantial recall biases (Zajchowski et al., Citation2017). Such research is altogether lacking in the Netherlands, where extant studies have addressed only the fundamentally different context of sport, specifically football, which has a regrettable history of fomenting intergroup confrontation in Europe (Krouwel et al., Citation2006). The existing literature thus fails to resolve an important prerequisite of productive intergroup contact in the context of attending expressive cultural activities––whether different groups, namely frequent and infrequent participants, experience such an activity similarly. To frame this question, we first explore the literature for elements that distinguish frequent and infrequent participants focusing on socialization and leisure constraints; and for elements that define and characterize structured leisure experiences, specifically emotions.

Explaining participation by socialization and constraints

There is extensive literature that attempts to explain why some persons undertake a particular category of leisure activities while others do not. Two of the most widely cited explanations are socialization theory and hierarchical leisure constraint theory. We review the pathways that both of these theories posit to expressive cultural (non-) participation, noting that neither has been linked to the experience itself in both frequent and infrequent participant populations.

Socialization during youth is a foundational influence on expressive cultural activity participation and experience. According to Shaw and Dawson (Citation2001), parents motivate their children to participate in leisure activities that might be advantageous for their child’s future. Many studies focus on the effects of participation in expressive cultural activities on a child’s cultural capital (e.g., Kisida et al., Citation2014) or educational achievement (e.g., Whitesell, Citation2016). However, few studies have researched whether participation in expressive cultural activities at a younger age predicts participation in adult life. Data from the 1992 Survey of Public Participation in the Arts in the United States suggested that school-based arts instruction had a significant positive effect on museum and performing arts attendance in adulthood (Kracman, Citation1996). More recently, a longitudinal study in the Netherlands by Nagel et al. (Citation2010) evaluated a secondary school course that compels adolescents to attend cultural activities. The authors measured students’ participation in, and attitude toward the arts 2, 4, and 6 years after they completed the course. Results showed no effects on increased participation, nor positive attitude toward the arts in early adulthood while controlling for cultural socialization by parents. From these studies, it seems that parental and educational socialization could each partly predict continued participation in expressive cultural activities when growing up.

Besides socialization, the theory of hierarchical leisure constraints has been extensively researched as an explanation of why some individuals participate in certain categories of leisure activities, while others do not. A summary of this extensive literature is beyond the scope of this article, for which we refer the reader to Godbey et al. (Citation2010). Rather, we briefly summarize the theory and explain how the relevant constructs have been operationalized in the expressive cultural activity context of the Netherlands.

According to hierarchical leisure constraints theory, constraints to a particular leisure activity type may be categorized as intrapersonal, which reside within the individual; interpersonal, which have to do with an individual's (lack of) relationships; and structural, which have to do with an individual's context, touching on common factors such as time and money. These are hierarchical, as there is some evidence that they must be dealt with in the order above for an individual to participate.

According to Godbey et al. (Citation2010), research on barriers to recreation predated and partly inspired hierarchical leisure constraints theory. Coincidentally, policy research on constraints in the Netherlands also uses the term "barriers." A large-scale survey by the Dutch Cultural Planning Office focused on potential barriers for participating in expressive cultural activities (Van den Broek, Citation2013). The study identified social, financial, temporal, and information constraints. The first category imperfectly corresponds to interpersonal constraints, whereas the latter three categories mostly fit with structural constraints. Among individuals who considered participating but didn’t actually participate, the main reason was that “it just didn’t happen,” which may be seen as intrapersonal, followed by “I’d rather not go alone,” which corresponds to descriptions of interpersonal constraints (Godbey et al., Citation2010). These reasons not to visit did not differ for the type of cultural activity, nor individual characteristics (gender, age, life stage, or level of education).

The (structured) dramatic performing arts experience

Experience is a crucial concept in the social psychology of leisure (Kleiber et al., Citation2011), though there has been much debate about what a leisure experience exactly is (Kivel et al., Citation2009). Within myriad definitions of experience in the literature, attending a dramatic performing arts event may be seen as a structured experience (Duerden et al., Citation2015; Ellis et al., Citation2019). The present study adopts Duerden et al.’s (Citation2015) definition of structured experiences. They define a structured experience as “the objective, interactive encounter between participants and provider manipulated frameworks and the resulting subjective participant outcomes of experiences” (Duerden et al., Citation2015, p. 603). Provider manipulated frameworks are described as stimuli during the experience which the provider intentionally manipulates. In the present study, these are the performance itself and the venue in which the performance takes place. Also important is the social context in which the experience occurs (Kivel et al., Citation2009), which suggests that frequent and infrequent expressive cultural activity attendees may experience a dramatic performance differently.

Ellis et al. (Citation2019) extend Duerden et al.’s (Citation2015) definition of structured experiences as also having clearly defined beginning and end points, lasting a few seconds to a few hours, being uninterrupted by other activities, and featuring planned encounters between provider and participant. In principle, a dramatic art performance fits this definition. The experience beginning and ending is marked by the house lights dimming and illuminating, it usually lasts 1–2 h, is normatively prevented from being interrupted, and features a planned presentation of actors to the audience of participants. If the experience is taken to also include the overall visit to the theater, the fit becomes somewhat looser. Nevertheless, the door of the theater forms a spatial boundary marking the beginning and end of the experience, the duration is rarely radically longer than the performance, and the theater and its staff plan their encounter with the audience as they make their way to and from the performance. The moments in the theater before and after the performance may be susceptible to interruption, however, if checking one's smartphone or visiting the bathroom are seen as “interruptions” to the theater visit experience. Thus, we focus our measurements of participants' experiences on the performance itself, while some of our self-response sub-scales account for the entire theater visit. While Duerden et al.’s (Citation2015) and Ellis et al.’s (Citation2019) definitions emphasize that providers plan an experience for their participants, and both provider and participant perspectives are part of the structured experience framework, our original impetus to compare frequent to infrequent participants' experiences led us to focus on participant perspectives, not those of providers.

Duerden et al.’s (Citation2015) and Ellis et al.’s (Citation2019) definitions fit with the consensus in psychological research that our lived experience is continually divided in so-called experiential episodes (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019) of which some are structured by an external source (for example, actors in a dramatic performance) and others are spontaneous (for example, an afternoon of painting). Note, however, that Duerden et al. (Citation2015) characterize a majority of leisure experiences as structured rather than spontaneous.

Multiple authors stress the importance of emotions in experiential episodes (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Duerden et al., Citation2015; Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009). As not every experiential episode is remembered (Kahneman, Citation2011), emotions are the key element that make an experience memorable and therefore meaningful (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019). While the emotional processes of leisure experiences have been measured in, for example, tourism contexts (e.g., Mitas et al., Citation2012), such measurements have never compared infrequent and frequent attendee experiences of expressive cultural activities, nor been linked to constraints and socialization in individuals' backgrounds.

Measuring experience and emotions

Traditionally in leisure research, measuring experience has mostly employed self-report surveys or in-depth interviews. Although surveys and interviews can provide valuable information about individuals’ experiences, attitudes, and motivations in a leisure context, there are disadvantages to self-report. Measuring experience and emotions using self-report is by definition an after-the-fact, cognitive evaluation of experience and emotion (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Tröndle et al., Citation2014). In fact, responses to experience questions on questionnaires can be seen as behaviors rather than experiences (Kivel et al., Citation2009).

New methods to measure emotions using wearable physiological measurement instruments are becoming more common in our field (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Mitas et al., Citation2020; Shoval et al., Citation2018; Tschacher et al., Citation2012). The use of these physiological measurements has a long history in clinical research (Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009; Wilhelm & Grossman, Citation2010). Physiological measurement approaches are becoming rapidly available through wearable consumer electronics (Birenboim et al., Citation2019). It is argued that measurements of physiological signals through wearables can provide fine-grained temporal detail of emotions while they unfold in an ecologically valid leisure context (Birenboim et al., Citation2019; Tröndle et al., Citation2014). There are various ways to obtain measurement of emotions through physiological signals. It is not our goal to discuss these, as excellent reviews are provided by Mauss and Robinson (Citation2009) and Bastiaansen et al. (Citation2019). According to these works, one commonly used metric is electrodermal activity, also termed skin conductance (Boucsein, Citation2012). This measure refers to changes in the skin’s ability to conduct electricity. As the sweat glands on feet and hands open in response to an emotional stimulus, the conductivity of the skin increases, resulting in a skin conductance response (SCR). These sweat glands are controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, part of the autonomic nervous system, which is activated by emotional arousal (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009). For an elaborate review of skin conductance, see Boucsein (Citation2012).

Most scholars agree that autonomic measures of emotion, such as skin conductance, do not translate to discrete emotions but rather to emotional arousal (Kreibig, Citation2010; Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009). Nonetheless, for measuring the succession of emotions in structured experiences, skin conductance affords fine-grained temporal detail of emotional arousal without the cognitive biases that limit self-response methods. Furthermore, psychophysiological methods have not yet been used to address issues of participation frequency and constraints in any leisure context. Therefore, the present study includes skin conductance measurement as a complement to conventional self-response measures. Thus, our findings offer a unique level of detail and triangulation in understanding participants’ experiences and address Floyd's (Citation2014) call for increasing methodological diversity in research on social inclusion in leisure.

The present study

In the present study, we address the broad relevance of publicly funded expressive cultural activity experiences. Understanding how frequent and infrequent participants may differ in their experiences is a prerequisite to engaging broad audiences. Furthermore, it is not well known if these experiences may be related not only to the frequency of participation but the constraints and socialization underlying participation frequency.

We invited frequent and infrequent participants in expressive cultural activities to attend a dramatic performing arts experience. We then measured their dispositions toward expressive cultural activities and their actual experiences on a cultural, social, and emotional level. To measure experiences, we use physiological measures in addition to self-report, as we chose to prioritize methodological triangulation of experience measurement. This choice limited our sample size, to the extent that multivariate analyses were not possible. Thus, our research questions are limited to bivariate relationships.

Research questions address relationships between participation frequency as well as socialization and constraints on one hand, and experiences on the other hand.

To what extent do infrequent and frequent expressive cultural activity attendees differ in terms of background variables, cultural socialization, participation in expressive cultural activities and constraints?

How do experiences of infrequent and frequent expressive cultural activity attendees differ while attending a dramatic performance?

How are constraints and socialization to previous expressive cultural activity participation related to experiences of a dramatic performance?

Methods

Study context

Data collection took place between September 14th and December 21st of 2018 in a theater in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Data were collected at two plays over five occasions. The first play (performance A) was a traditional drama, depicting struggles in the life of a young couple. The second play (performance B) was a more experimental performance which was played without spoken words, using gestures, ambient music, and visually engaging props to tell a story. These performances were selected by the theater based on their accessibility for novice performing arts attendees, thus ensuring that lacking previous dramatic performing art experience would not necessarily or inherently limit potential emotional responses of infrequent attendees.

Participants

We aimed to create a bimodal diversity sample wherein approximately half of participants attended expressive cultural activities frequently, whereas half did not. Young adults, aged 20–34, participated the least in dramatic performing arts in the Netherlands (Tiessen-Raaphorst & Van den Broek, Citation2016). As the continued public funding for expressive cultural activities in the Netherlands is based on an assumption that they offer widely relevant leisure experiences for all inhabitants (Ministry of Education Culture & Science, Citation2014), we selected young adults as our population for this research, As it proved to be difficult to reach out to infrequently participating young adults, we employed a buddy-selection technique, a type of snowball sampling. The strengths and weaknesses of this buddy-selection technique are reviewed in the discussion. Young adults were contacted via mailing lists of frequent regular dramatic performing arts attendees and were asked to select a friend who rarely or never attends dramatic performing arts events for participation. Requirements to participate in the latter sub-sample comprised (1) attending performing arts rarely or not at all, and (2) being between 18 and 35 years old. Out of the 41 participants that took part in the study, five participants did not meet these requirements, resulting in a final sample of 36 participants. The two subsamples each consisted of 18 individuals.

The infrequent dramatic performing arts participants consisted of three males and 15 females with ages ranging from 18 to 29 (M = 23.22, SD = 3.25). The frequent attendees consisted of eight males and 10 females with ages also ranging from 18 to 29 (M = 23.89, SD = 3.50). The two groups did not significantly differ in terms of the background variables age (t34 = −0.59 p = 0.557), gender (χ1 = 3.27, p = 0.070), level of education (Likelihood Ratio(3) = 1.11, p = 0.786), living situation (χ1 = 0.45, p = 0.502), main occupation (χ1 = 0.11, p = 0.735), relationship status (Likelihood Ratio(1) = 0.15, p = 0.700) and whether they had children or not.

Measurements

A pre-experience questionnaire measured cultural socialization, participation in expressive cultural activities, constraints, and demographic variables. Cultural socialization items were adopted from De Rooij (Citation2013) and consisted of three items: active childhood participation in expressive cultural activities, childhood participation in expressive cultural activities with school, and, childhood participation in expressive cultural activities with parents. These items were measured with a 5-point Likert-type scale. Expressive cultural activity participation was measured with two items, number of visits to dramatic performing arts in the past 12 months, and the number of visits to expressive cultural activities in general in the past 12 months. The latter item listed music festivals, museum visits, and concerts as examples of expressive cultural activities. We opted for the perceived barriers to participation items as used in policy research in the Netherlands over an established leisure constraints scale. Multiple leisure constraints scales exist and are generally validated using context-dependent approaches (Godbey et al., Citation2010). Many developed scales are mostly focused on sports and outdoor recreation (e.g., Carroll & Alexandris, Citation1997; Hubbard & Mannell, Citation2001). The perceived barriers items as used in a study by the Dutch Cultural Planning Office (Van den Broek, Citation2013) were aimed at participation in the arts and cultural activities in the Netherlands and also included items relating to interpersonal, intrapersonal and structural constraints. We, therefore, argued that the perceived barriers to participation items, as used in policy research in the Netherlands, fit best to the research context and, to some degree, reflect leisure constraints. The perceived barriers scale comprised six items which were measured on a 5-point Likert scale. Three items focused on intrapersonal constraints (“I didn’t know what I could do there,” “It just didn’t happen,” “It’s not for people like me”), one item on interpersonal constraints (“I’d rather not go alone”), and two items focused on the structural constraints of distance and costs.

A post-experience questionnaire measured seven dimensions of performing arts experience based on De Rooij and Bastiaansen (Citation2017): artistic value, beauty, cultural relaxation, cultural stimulation, social attraction, social bonding, and social distinction. Each of these dimensions was measured with three items on a 5-point Likert-scale. Furthermore, the post-questionnaire measured 11 self-reported experienced emotions with word-triplets based on the consumption emotion scale (CES) by Richins (Citation1997) and the modified differential emotion scale (mDES) by Fredrickson et al. (Citation2003). Two semantic differential scale items were used for self-reported valence (very negative—very positive) and arousal (calm—excited). The complete item list can be found in Appendix A.

During the performance, physiological data were recorded with the Empatica E4. This wearable wristband records, amongst other signals, skin conductance and acceleration data. Skin conductance is continuously sampled at 4 Hz and stored on the device.

Procedure

On the day of the performance, participants were informed about the study, and gave their written informed consent. They filled out the first questionnaire, and the Empatica E4 wristbands were put on their wrists. Subsequently, the researcher marked the time of the start of the performance. In addition, time-stamped field notes were made about time of entering the hall, start of performance, end of the performance, and exiting the hall. After the performance ended, the researcher collected the wristbands, and participants filled out the second questionnaire.

Data analysis

Questionnaire data

Averages were computed for the different scales in the pre- and the post-experience questionnaires, and Cronbach’s alphas were computed for each scale. Independent samples t-tests were performed to analyze differences between the frequent and infrequent participants for each of the scales.

Physiological data

Signal processing. Skin conductance data and accelerometer data were extracted from the Empatica devices and stored on a PC. Subsequent signal processing and statistical analysis was done with the software environment Matlab. The data was time-synchronized for each participant with the start and end of each of the performances. For performance A, this analysis yielded a data segment of approximately 115 min; for performance B, 65 min.

Next, motion artifacts (Taylor et al., Citation2015) were removed from the skin conductance data. Motion artifacts are high-amplitude, short-lived spikes (Boucsein, Citation2012; Taylor et al., Citation2015) and result from movement of the sensors relative to the skin. For detecting and correcting motion artifacts in skin conductance data we moved a 20-s time window over the skin conductance data, applied a z-transformation within the window, and visualized the data whenever a z-value in the time-window exceeded the value of ±4. A visualization of accelerometer data in the same time-window assisted the researcher in determining whether a true motion artifact was found. When the researcher identified a motion artifact, it was replaced by linearly interpolated values connecting the two edges of the motion artifact. In case of ambiguity, the data were not corrected to avoid removing potential true skin conductance responses. The data could therefore contain residual motion artifacts. In the present data, motion artifacts were detected in each participant’s skin conductance signals and were typically, though not exclusively, found when the audience was applauding, supporting the criterion validity of the artifact removal procedure.

Subsequently, skin conductance data were normalized through a z-transform, after which we applied continuous deconvolution to separate phasic responses (the true skin conductance response, SCR) from tonic skin conductance levels (for details, see Benedek & Kaernbach, Citation2010). The open-source Matlab toolbox Ledalab (Benedek & Kaernbach, Citation2010) was used. SCRs are most closely related to emotional arousal and this signal is therefore used in all subsequent analyses (Benedek & Kaernbach, Citation2010; Boucsein, Citation2012).

Finally, although we aligned the data as closely as possible between different plays of the same performance when segmenting the data, a perfect alignment of different plays proved to be impossible, as the plays differed slightly in length (2–3 min). In order to accommodate for this in the data analysis, we smoothed the SCRs using a moving average of 120 s.

Statistical analysis. Two independent samples t-tests were performed on the SCR data for each performance: (1) SCRs of each participant were averaged over the whole duration of the performance, and mean SCR was compared between the frequent and infrequent participant groups; and (2) independent-samples t-tests were performed on each SCR data point in time for the frequent and infrequent participant groups, controlling for multiple comparisons using false discovery rate correction. Finally, linear regressions predicted the individual behavioral measures of overall emotional valence and arousal from the individual mean SCRs.

Results

Questionnaire data

Significantly different groups

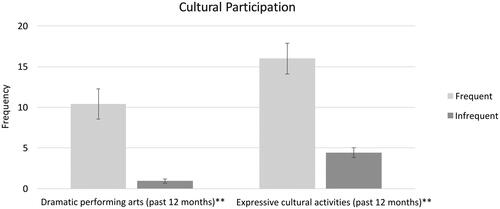

Participants from the infrequent dramatic performing arts attendee group scored significantly lower not just on their performing arts attendance (t34 = 5.06, p < 0.001), but also on participation in expressive cultural activities in general (t34 = 5.81, p < 0.001; ). This finding confirmed that the buddy-technique successfully yielded participant subsamples that differed in dramatic performing arts and expressive cultural activity behavior. Furthermore, the lack of difference between the two groups on multiple sociodemographic measures suggested that they comprise appreciably matched sub-samples for exploring the effects of differences in participation frequency on experiences.

Group differences in cultural socialization

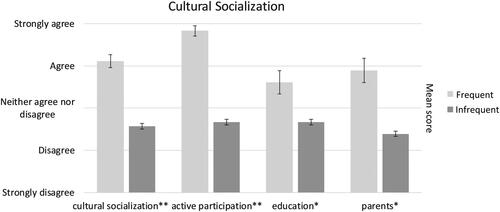

We observed significant differences between both groups in terms of cultural socialization (t34 = 5.65, p < .001; Cronbach’s alpha of 0.75 for this three-item scale). On the single-item level there are significant differences between the groups on all items. The frequent participation group scored significantly higher (t34 = 5.96, p < 0.001) on active participation in their childhood, and on cultural socialization in their education (t34 = 2.82, p = 0.008) and by their parents (t34 = 3.64, p = 0.001), compared to the infrequent participants ().

Group differences in constraints to performing arts participation

Infrequent participants in dramatic performing arts perceived constraints that frequent participants did not. The two groups differed on the items “It just didn’t happen,” “I didn’t know what I could do there,” and “It’s not for people like me.” On average, infrequent participants agreed with the statements “It just didn’t happen,” whereas the frequent participants did not (Minfrequent = 3.95, SD = 0.921; Mfrequent = 2.41, SD = 1.185). This is also the case for “I didn’t know what I could do there” and “it’s not for people like me” ().

Table 1. Comparing means of frequent and infrequent participants on perceived barriers to visit (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree).

Evaluation of experience

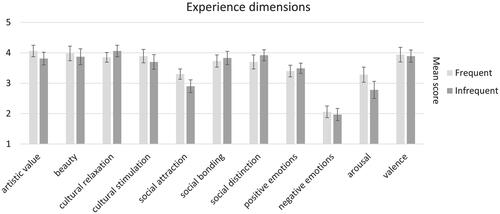

The participants were asked to rate their experience afterwards on seven different experience dimensions, positive emotions, negative emotions, valence, and arousal (). The first four dimensions, artistic value, beauty, cultural relaxation, and cultural stimulation focused on the performance itself. These sub-scales’ reliability ranged from reasonable (0.67 for cultural relaxation) to strong (0.94 for beauty). No statistically significant differences between the groups were observed on these dimensions; artistic value (t34 = 0.84, p = 0.410), beauty (t34 = 0.31, p = 0.757), cultural relaxation (t34 = −0.82, p = 0.417), and cultural stimulation (t34 = 0.57, p = 0.572). On average, both groups agreed that the performance has artistic value and is beautiful. Furthermore, both groups experienced the performance as a "relaxing cultural activity" and felt intellectually stimulated by the performance.

Figure 3. Between group differences on averaged experience sub-scales (1 = strongly disagree, 5 = strongly agree) and emotions Likert-scales (1 = not at all, 5 = extremely), and semantic differential scales for arousal (1 = calm, 5 = excited) and valence (1 = very negative, 5 = very positive). Error bars represent standard errors. *p < .05. **p < .001.

The social dimension of the dramatic performing arts experience was measured with three sub-scales ( and Appendix A). It is important to note that unlike the sub-scales discussed above, which address the phase of the experience from the beginning to the end of the performance itself, sub-scales addressing social dimensions measured the experience from the moment participants entered the theater to when they exited. Anecdotally, we assessed the difference between the overall theater visit and the performance itself as rather modest and, in fact, comprising mostly filling in the intake and exit questionnaires for the present study. Participants did not arrive early and did not linger after the performance. Filling out our consent forms and questionnaires absorbed whatever little time they spent at the theater before and after the performance.

The sub-scales for social attraction and for social bonding were reliable (Cronbach’s alpha values of 0.76 and 0.71, respectively). However, the reliability of the scale for social distinction was low (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.50). When the item “people from my social network appreciate a visit to cultural activities” was removed from the scale, the Cronbach’s alpha is a sufficient 0.71. Therefore, for this subscale the average was computed for the remaining two items only. Again, both groups did not differ significantly on any of the sub-scales; social attraction (t34 = 1.48, p = 0.149), social bonding (t33 = −0.36, p = 0.720) and social distinction (t34 = −0.77, p = 0.448).

We computed the average of the six positive emotion (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.83) and the five negative emotion (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.74) items. Both groups experienced more positive than negative emotions, however they did not differ significantly from each other on positive (t33 = −0.34, p = 0.734) and negative emotions (t33 = 0.33, p = 0.742), emotional valence (t34 = 0.18, p = 0.857) and emotional arousal (t34 = 1.34, p = 0.190).

Skin conductance data

Comparing the frequent and infrequent groups’ SCRs

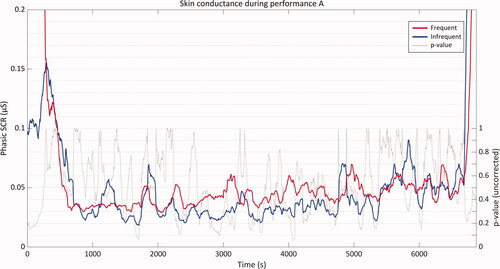

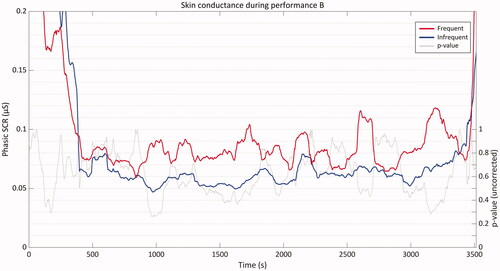

Grand averages of phasic SCR separately for the frequent and infrequent participants are represented in for performance A and for performance B. These Figures show the SCRs of both groups from the start of the performance until the end. In general, the SCR was larger for the infrequent than the frequent participants, though not significantly so. Both figures show that SCRs reached very high values at the start of the performance (for about 300 s) and the end of the performance (for about 60 s). These high values were produced by an abundance of motion artifacts due to the applause at the beginning and the end of the performance, which was impossible to reliably correct for using our artifact detection and correction procedure.

Figure 4. Grand average phasic skin conductance for the in-group (n = 8) and the out-group (n = 8) during performance A. Gray line corresponds to the uncorrected p-values (right-hand y-axis) from the independent samples t-test on each sampling point.

Figure 5. Grand average phasic skin conductance for the in-group (n = 10) and the out-group (n = 10) during performance B. Gray line corresponds to the uncorrected p-values (right-hand y-axis) from the independent samples t-test on each time point.

An independent samples t-test on the SCRs of frequent and infrequent individuals averaged across all the time points for performance A indicated that there was no significant difference between the two groups and their emotional arousal as measured through SCR (t14 = −0.991, p = 0.355). Furthermore, independent samples t-tests comparing the SCR values between the two groups at each time point, did not show a statistical difference between the groups, even without the intended false discovery rate correction for multiple comparisons (c.f., the gray line in ). Uncorrected p-values rarely reached below 0.10, and never lower than 0.056.

Although strongly suggests that SCR values throughout performance B were larger for infrequent participants than for frequent participants, an independent samples t-test on the time-averaged SCR values of the frequent and infrequent participants revealed that there was no significant difference in SCR between the groups (t18 = 0.384, p = 0.721). In the continuous comparison of the SCRs of both groups we again did not find any significant differences in the averaged emotional arousal (cf. the gray line in Figure 6).

Predicting self-reported emotions from averaged SCRs

Regression analyses showed that time-averaged SCRs did not predict retrospective self-reported emotion dimensions of valence and arousal. When predicting overall emotional arousal from the time-averaged SCRs the R2 value is low (0.004) and the regression model is not significant (F1, 35 = 0.125, p = 0.726). The same holds when predicting overall valence from the mean SCR (R2 = 0.002, F1, 35 = 0.058, p = 0.811).

Relationships between constraints, socialization and experience

We analyzed the relationship between constraints and socialization and the experience dimensions. Bivariate Pearson correlations showed some significant relationships. Most of these were between the constraint item “It’s not for people like me” and experience dimensions (). The correlation coefficients (r) vary between −0.400 and −0.490, indicating a significant negative relationship between this constraint and the experience dimensions of artistic value, beauty, cultural stimulation, and social attraction. The only two other constraints that correlated with the experience dimensions were distance and “I didn’t know what I could do there.” None of the socialization items correlated significantly with any of the experience dimensions. Furthermore, for correlations between constraints and emotions, only “It’s not for people like me” correlated significantly with SCR (). No significant correlations between constraint items and self-reported emotions were found.

Table 2. Correlations between constraints, socialization, experience evaluation and emotions.

Discussion and conclusion

Participation in expressive cultural activities is often regarded as beneficial on an individual and societal level. Therefore, participation in expressive cultural activities has an important role in policymaking and is subsidized in many Western countries (Belfiore & Bennett, Citation2008). However, not all members of society participate equally (Falk & Katz-Gerro, Citation2016; Feder & Katz-Gerro, Citation2012). Furthermore, expressive cultural activities may act as markers of boundaries between social groups than as an invitation for interaction (Kuipers & Van den Haak, Citation2014). According to Dutch policy research, these boundaries are self-reinforcing and evident in decreasing expressive cultural activity participation of young adults (Tiessen-Raaphorst & Van den Broek, Citation2016; Van den Broek, Citation2013). This pattern suggests that intergroup contact in this context (Hewstone, Citation2015) is an urgent need, but requires at an absolute minimum for both frequently and infrequently attending participants to have engaging experiences. A comparison of experiences of infrequent and frequent participants had previously not been recorded in detail in this context and population.

Therefore, we assessed whether the experience of frequently attending young adults differed from the experience of those who do not attend expressive cultural activities frequently. Specifically, we measured the cultural, social, and emotional experience of infrequent and frequent attendee young adults during two performances in a theater in Rotterdam, the Netherlands. In addition, we measured whether these groups significantly differed from each other on constraints and socialization aspects thought to influence participation in expressive cultural activities. Results of self-report data showed that the two groups did not differ in terms of background variables. Infrequently participating young adults differed significantly from the frequently participating young adults on all socialization and some constraints items that were measured in this study. Surprisingly, the self-report data showed no significant difference on any of the experience dimensions measured. In addition, physiological data measuring the experience through emotional arousal showed a pattern that seems to suggest that the infrequent attendee subsample is slightly more emotionally aroused by the performance than the frequent attendee subsample. However, this difference was not statistically significant.

When examining relationships between constraints and socialization on the one hand, and experience on the other, several significant effects were found. The more participants reported that performances like the one they viewed are "not for people like them," the lower they rated the artistic value and beauty of the performance, and the less they found it culturally stimulating. There was a positive and significant correlation with SCR, which indicates that those who feel the performance was not for people like them had a stronger emotional response (higher arousal levels) to the performance.

Our findings extend existing literature in three ways. First, our study contributes to inclusion policy and to knowledge on social psychology of expressive cultural activities by demonstrating how constraints and socialization influence the experience of a dramatic performance. Second, we establish an important prerequisite for broad audience relevance and intergroup contact in expressive cultural activities by showing that similar emotions may be experienced by two different subsamples at a dramatic performance. Third, we extend knowledge on structured experiences by showing that the general patterns present in momentary experience measurements are congruent with, though not identical to, recollected experiences.

Importance of constraints and socialization

We investigated if frequent and infrequent attendees of expressive cultural activities differed in their background demographics and two alleged predictors of participation—socialization and constraints. The data provide a clear answer to our first research question: To what extent do infrequent and frequent performing arts attendees differ in terms of background variables, cultural socialization, participation in expressive cultural activities and constraints? Our sampling strategy aimed to create a bimodal sample in terms of frequency of expressive cultural activity participation.

Results showed that frequent and infrequent attendees did not differ on the background variables. On the contrary, the infrequent and frequent attendees differed significantly on cultural socialization and on most constraints, as well as on the outcome behaviors of interest—participation in expressive cultural activities.

Thus, as suggested in previous studies on leisure participation, both socialization (Shaw & Dawson, Citation2001) and constraints (Godbey et al., Citation2010) were related to participation in cultural activities. That is far from saying that frequent and infrequent attendance at performing arts events represents a boundary between cultural groups (Chick et al., Citation2007). Rather, the findings demonstrate that the two sub-samples we recruited may move in overlapping social circles in parts of life such as work, family, or recreational sports, but do not intersect in the expressive cultural activity social milieu.

Our findings also showed relationships between constraints and experience, but not between socialization and experience, thereby answering the third research question: How are constraints and socialization to previous expressive cultural activity participation related to experiences of a dramatic performance? While constraints have been linked to outcomes such as participation, satisfaction, and involvement (Alexandris, Citation2013; Carroll & Alexandris, Citation1997; Godbey et al., Citation2010; Hubbard & Mannell, Citation2001) connections to an experience—especially a time-mapped continuous experience measurement—was lacking from this literature. We found that one specific intrapersonal constraint—seeing the dramatic performance as "not for people like me"—was negatively related to numerous judgments of the performance. This finding could indicate that participants with this constraint do not appreciate the performance as much as participants who do think dramatic performing arts are for people like them, though both self-reported a similar emotional experience.

On the other hand, this constraint was positively related to SCR. This finding could be explained by the novelty of the experience (Mitas & Bastiaansen, Citation2018; Skavronskaya et al., Citation2020), or perhaps the anticipation of experiencing something that participants normally do not experience (Gilbert, Citation2009). The connection between emotional arousal and the constraint “not for people like me” merits exploring in future research. In sum, understanding that some constraints but not others are predictive of emotions during a leisure experience comprises a novel contribution to research on leisure constraints. No such links between socialization and experience were found.

Participation background and experience

Although infrequent and frequent attendees did indeed differ in terms of socialization and constraints, their experience of the performance did not. These results answer our second research question: How do experiences of infrequent and frequent expressive cultural activity attendees differ while attending a dramatic performance? Both groups valued the cultural experience dimensions positively. This finding indicates that the cultural experience was as good for infrequent participants as for the frequent participants. This interpretation is supported by the self-report and physiological data on participants' emotional responses to the experience. It is surprising that these groups, which differ so robustly in their expressive cultural activity backgrounds, have such a similarly positive experience. The findings show that an experience of dramatic performing arts—in this case novel for the infrequent and familiar for the frequent group—can be relatively similar for both groups.

Interestingly, the self-report data shows that frequent and infrequent attendees also do not differ in terms of the social experience. On average, participants seem to be indifferent about social attraction but are positive about social bonding and social distinction. These results seem to suggest that it is important to both groups to be with friends or family and to be able to tell friends and family about their performing arts experience.

Thus, our findings support an important prerequisite to intergroup contact within expressive cultural activities, namely that these activities have to provide similarly positive experiences to infrequent attendees. It could be questioned if social interactions between different groups actually happen during a dramatic performing arts experience, and whether intergroup contact is facilitated by the performing arts. Thus, we add a note of caution to the societal debate on whether cultural activities can function as an instrument to diminish social fragmentation (Belfiore & Bennett, Citation2008). It is clear that to facilitate intergroup contact, expressive cultural activities must be structured accordingly. Furthermore, while some constraints affect their experience, background expressive cultural activity socialization does not. Thus, potential for broader audience appeal and, potentially, intergroup contact exists in dramatic performing arts.

Emotions during structured experiences

Literature on leisure experiences (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Duerden et al., Citation2015; Ellis et al., Citation2019) suggests that emotions are a key variable in measuring experiences. Accordingly, our study triangulated self-report and physiological measures of emotion to capture participants' reactions to a dramatic performance. We found that emotions did not differ between infrequent and frequent expressive cultural activity attendees, in self-report as well as in physiology.

We did not find direct relationships between self-report and physiological emotion data, however, validating a growing body of literature that firmly states that these emotion components are independent (Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009; Mitas et al., Citation2020; Zajchowski et al., Citation2017). Although SCRs reflect emotional arousal (Bastiaansen et al., Citation2019; Mauss & Robinson, Citation2009), SCRs did not significantly predict the self-reported overall evaluation of emotional arousal, nor the self-reported overall emotional valence. According to Mauss and Robinson (Citation2009), different techniques for measuring emotions share little common variance, which limits convergence across measures. This view could explain why our physiological measures do not significantly predict behavioral measures. Additionally, Mauss and Robinson (Citation2009) argue that correlations between different measures of emotion are moderate at best, but typically low, which is consistent with our findings.

Suggestions for further research

Social fragmentation

Our results suggest that when young adults who rarely attend the performing arts join frequently participating young adults at a dramatic performance, they will have similar experiences. However, our results do not indicate whether our infrequent attendee participants will now participate in expressive cultural activities more often in the future. Furthermore, our results also suggest that infrequent participants mostly interacted with the frequent participant friends who recruited them for the study. While these participant pairs did not share a common background in the social milieu of expressive cultural activities, their lives clearly intersected in other areas. Moreover, the influence of frequently participating friends on the experience of infrequent participant could not be controlled for. Thus, several future studies may be designed to further explore the potential of intergroup interaction in the expressive cultural activity context. First, some expressive cultural activities are specifically designed to foster interaction among attendees, which was not the case in the performances we studied. The effects of these two types of activity—with and without interactions—may be contrasted in future research. Second, our approach may be replicated with a different, ideally larger sample, in which infrequent and frequent participants do not know each other from other contexts. Furthermore, future research should consider taking the anticipation or expectation aspect of the experience into account, as previous research has shown that this aspect can have a profound influence on the experience (Gilbert, Citation2009; Wirtz et al., Citation2003). Also, measuring intentions to revisit or revisit behavior within a longitudinal design to determine to what extent benefits of experiences or interactions endure should be considered.

Physiological measurements in leisure research

Based on the methodological challenges we encountered using physiological measures of experience, we have five suggestions for researchers that want to use skin conductance to measure leisure experiences. First, we suggest that physiological approaches are most informative when studying highly structured experience with a clear start and end time, or clear, fixed time segments. Especially when comparing between participants with high temporal detail, the duration of the participants’ experiences should be equal. Second, to reduce motion artifacts in the data, we suggest a well-controlled experience where the likelihood of the electrodes moving relative to the skin is reduced to a minimum. Even then, using an artifact removal algorithm, of which several are now freely available, is indispensable. Third, researchers should consider that wearable devices such as the Empatica E4 measure skin conductance on the wrist, unlike in lab studies where electrodes are placed on the palm or fingertips. Thus, there are substantial genetic differences in how much individuals respond to emotion in this skin area, and researchers have to count on 20% data loss due to non-responders (Boucsein et al., Citation2012). Fourth, some authors in our field have not yet distinguished between phasic and tonic components of skin conductance, which seriously degrades results. This step in the data processing should absolutely not be neglected (Benedek & Kaernbach, Citation2010; Shoval et al., Citation2018). Finally, physiological measures of emotion should not be used in isolation from self-report measures, as these two approaches have been repeatedly demonstrated to measure independent components of emotion. For capturing temporal and qualitative nuance of emotion during structured experiences, qualitative and qualitative-to-quantitative approaches such as experience reconstruction (Strijbosch et al., Citation2019) are promising. The limitations and costs of physiological emotion measurement are outweighed by the advantages of capturing the fine-grained temporal detail of emotional arousal in leisure experiences. We, therefore, encourage leisure scholars to incorporate physiological measurements in their future research designs.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexandris, K. (2013). Segmenting recreational tennis players according to their involvement level: A psychographic profile based on constraints and motivation. Managing Leisure, 18(3), 179–193. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13606719.2013.796178

- Bastiaansen, M., Lub, X. D., Mitas, O., Jung, T. H., Ascenção, M. P., Han, D.-I., Moilanen, T., Smit, B., & Strijbosch, W. (2019). Emotions as core building blocks of an experience. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 31(2), 651–668. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-11-2017-0761

- Belfiore, E., & Bennett, O. (2008). The social impact of the arts: An intellectual history. In E. Belfiore & O. Bennett (Eds.), The social impact of the arts: An intellectual history. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Benedek, M., & Kaernbach, C. (2010). A continuous measure of phasic electrodermal activity. Journal of Neuroscience Methods, 190(1), 80–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jneumeth.2010.04.028

- Birenboim, A., Dijst, M., Scheepers, F. E., Poelman, M. P., & Helbich, M. (2019). Wearables and location tracking technologies for mental-state sensing in outdoor environments. The Professional Geographer, 71(3), 449–461. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2018.1547978

- Boucsein, W. (2012). Electrodermal activity (2nd ed.). Springer.

- Boucsein, W., Fowles, D. C., Grimnes, S., Ben-Shakhar, G., Roth, W. T., Dawson, M. E., & Filion, D. L. (2012). Publication recommendations for electrodermal measurements. Psychophysiology, 49(8), 1017–1034. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8986.2012.01384.x

- Carroll, B., & Alexandris, K. (1997). Perception of constraints and strength of motivation: Their relationship to recreational sport participation in Greece. Journal of Leisure Research, 29(3), 279–299. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1997.11949797

- Chick, G. E., Li, C. L., Zinn, H. C., Absher, J. D., & Graefe, A. R. (2007). Ethnicity as a construct in leisure research: A rejoinder to Gobster. Journal of Leisure Research, 39(3), 554–566. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2007.11950122

- De Rooij, H. P. G. M. (2013). Customer loyalty to performing arts venues: Between routines and coincidence. Tilburg University.

- De Rooij, H. P. G. M., & Bastiaansen, M. (2017). Understanding and measuring consumption motives in the performing arts. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society, 47(2), 118–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10632921.2016.1259132

- Driver, B., Brown, P., & Peterson, G. (1991). Benefits of leisure. Venture.

- Duerden, M. D., Ward, P. J., & Freeman, P. A. (2015). Conceptualizing structured experiences: Seeking interdisciplinary integration. Journal of Leisure Research, 47(5), 601–620. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2015-v47-i5-6096

- Ekholm, D., & Lindström Sol, S. (2019). Mobilising non-participant youth: Using sport and culture in local government policy to target social exclusion. International Journal of Cultural Policy, 26(4), 510–523.

- Ellis, G. D., Freeman, P. A., Jamal, T., & Jiang, J. (2019). A theory of structured experience. Annals of Leisure Research, 22(1), 97–118. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2017.1312468

- Falk, M., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2016). Cultural participation in Europe: Can we identify common determinants? Journal of Cultural Economics, 40(2), 127–162. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10824-015-9242-9

- Feder, T., & Katz-Gerro, T. (2012). Who benefits from public funding of the performing arts? Comparing the art provision and the hegemony-distinction approaches. Poetics, 40(4), 359–381. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2012.05.004

- Floyd, M. F. (2014). Social justice as an integrating force for leisure research. Leisure Sciences, 36(4), 379–387. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2014.917002

- Fredrickson, B. L., Tugade, M. M., Waugh, C. E., & Larkin, G. R. (2003). What good are positive emotions in crises? A prospective study of resilience and emotions following the terrorist attacks on the United States on September 11th, 2001. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 84(2), 365–376. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.84.2.365

- Gilbert, D. (2009). Stumbling on happiness. Random House USA.

- Godbey, G., Crawford, D. W., & Shen, X. S. (2010). Assessing hierarchical leisure constraints theory after two decades. Journal of Leisure Research, 42(1), 111–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2010.11950197

- Hewstone, M. (2015). Consequences of diversity for social cohesion and prejudice: The missing dimension of intergroup contact. Journal of Social Issues, 71(2), 417–438. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/josi.12120

- Hubbard, J., & Mannell, R. C. (2001). Testing competing models of the leisure constraint negotiation process in a corporate employee recreation setting. Leisure Sciences, 23(3), 145–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/014904001316896846

- Kahneman, D. (2011). Thinking, fast and slow. Macmillan.

- Kisida, B., Greene, J. P., & Bowen, D. H. (2014). Creating cultural consumers: The dynamics of cultural capital acquisition. Sociology of Education, 87(4), 281–295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040714549076

- Kivel, B. D., Johnson, C. W., & Scraton, S. (2009). (Re)theorizing leisure, experience and race. Journal of Leisure Research, 41(4), 473–493. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.2009.11950186

- Kleiber, D., Walker, G., & Mannell, R. (2011). A social psychology of leisure (2nd ed.). Venture.

- Kracman, K. (1996). The effect of school-based arts instruction on attendance at museums and the performing arts. Poetics, 24(2-4), 203–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-422X(96)00009-5

- Kreibig, S. D. (2010). Autonomic nervous system activity in emotion: A review. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 394–421. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.03.010

- Krouwel, A., Boonstra, N., Duyvendak, J. W., & Veldboer, L. (2006). A good sport?: Research into the capacity of recreational sport to integrate Dutch minorities. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 41(2), 165–180. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690206075419

- Kuipers, G., & Van den Haak, M. (2014). De cultuurkloof? Cultuurverschillen en sociale afstand in Nederland. In B. Mark, P. Dekker, & W. Tiemijer (Eds.), Gescheiden Werelden? Een verkenning van sociaal-culturele tegenstellingen in Nederland (pp. 193–215). Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau & Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid.

- Long, J., & Bianchini, F. (2019). New directions in the arts and sport? Critiquing national strategies. Sport in Society, 22(5), 734–753. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2018.1430484

- Mauss, I. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2009). Measures of emotion: A review. Cognition & Emotion, 23(2), 209–237.

- Ministry of Education Culture and Science. (2014). Culture at a glance.

- Mitas, O., & Bastiaansen, M. (2018). Novelty: A mechanism of tourists’ enjoyment. Annals of Tourism Research, 72, 98–108. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2018.07.002

- Mitas, O., Cuenen, R., Bastiaansen, M., Chick, G. E., & van den Dungen, E. (2020). The war from both sides: How Dutch and German visitors experience an exhibit of Second World War stories. International Journal of the Sociology of Leisure, 3(3), 277–303. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s41978-020-00062-3

- Mitas, O., Yarnal, C., Adams, R., & Ram, N. (2012). Taking a “peak” at leisure travelers’ positive emotions. Leisure Sciences, 34(2), 115–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2012.652503

- Nagel, I., Damen, M. L., & Haanstra, F. (2010). The arts course CKV1 and cultural participation in the Netherlands. Poetics, 38(4), 365–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2010.05.003

- Pettigrew, T. F., & Tropp, L. R. (2008). How does intergroup contact reduce prejudice? Meta-analytic tests of three mediators. European Journal of Social Psychology, 38(6), 922–934. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.504

- Richins, M. L. (1997). Measuring emotions in the consumption experience. Journal of Consumer Research, 24(2), 127–146. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/209499

- Shaw, S. M., & Dawson, D. (2001). Purposive leisure: Examining parental discourses on family activities. Leisure Sciences, 23(4), 217–231. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400152809098

- Shinew, K. J., Floyd, M. F., McGuire, F. A., & Noe, F. P. (1995). Gender, race, and subjective social class and their association with leisure preferences. Leisure Sciences, 17(2), 75–89. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409509513245

- Shoval, N., Schvimer, Y., & Tamir, M. (2018). Real-time measurement of tourists’ objective and subjective emotions in time and space. Journal of Travel Research, 57(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0047287517691155

- Skavronskaya, L., Moyle, B., & Scott, N. (2020). The experience of novelty and the novelty of experience. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, Article 322. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00322

- Strijbosch, W., Mitas, O., van Gisbergen, M., Doicaru, M., Gelissen, J., & Bastiaansen, M. (2019). From experience to memory: On the robustness of the peak-and-end-rule for complex, heterogeneous experiences. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, Article 1705. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01705

- Taylor, S., Jaques, N., Chen, W., Fedor, S., Sano, A., Picard, R. (2015). Automatic identification of artifacts in electrodermal activity data. Proceedings of the 37th Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine and Biology Society (EMBS) (pp. 1934–1937). IEEE.

- Tiessen-Raaphorst, A., & Van den Broek, A. (2016). Sport en cultuur: Patronen in belangstelling en beoefening. Den Haag.

- Tröndle, M., Greenwood, S., Kirchberg, V., & Tschacher, W. (2014). An integrative and comprehensive methodology for studying aesthetic experience in the field: Merging movement tracking, physiology, and psychological data. Environment and Behavior, 46(1), 102–135. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013916512453839

- Tschacher, W., Kirchberg, V., van den Berg, K., Greenwood, S., Wintzerith, S., & Tröndle, M. (2012). Physiological correlates of aesthetic perception of artworks in a museum. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts, 6(1), 96–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023845

- Van den Broek, A. (2013). Kunstminnend Nederland? Interesse en bezoek, drempels en ervaringen. Den Haag.

- Volker, B., Andriessen, I., & Posthumus, H. (2014). Gesloten werelden? Sociale contacten tussen lager-en hogeropgeleiden. In M. Bovens, P. Dekker, & W. Tiemijer (Eds.), Gescheiden Werelden? Een verkenning van sociaal-culturele tegenstellingen in Nederland (pp. 217–234). Sociaal Cultureel Planbureau & Wetenschappelijke Raad voor het Regeringsbeleid.

- Whitesell, E. R. (2016). A day at the museum: The impact of field trips on middle school science achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 53(7), 1036–1054. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.21322

- Wilhelm, F. H., & Grossman, P. (2010). Emotions beyond the laboratory: Theoretical fundaments, study design, and analytic strategies for advanced ambulatory assessment. Biological Psychology, 84(3), 552–569. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biopsycho.2010.01.017

- Wirtz, D., Kruger, J., Scollon, C. N., & Diener, E. (2003). What to do on spring break? The role of predicted, on-line, and remembered experience in future choice. Psychological Science, 14(5), 520–524. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9280.03455

- Zajchowski, C. A. B., Schwab, K. A., & Dustin, D. L. (2017). The experiencing self and the remembering self: Implications for leisure science. Leisure Sciences, 39(6), 561–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1209140

Appendix A: Item list

Table A1. Pre-experience questionnaire.

Table A2. Post-experience questionnaire.