Abstract

Instagram is increasingly used in advertising, yet little is known about the unintended consequences of Instagram advertising on women’s and girls’ body image. Also largely unexplored is if and how curvy models (large breasts and buttocks, wide hips, and small waist) used in this advertising affect women’s and girls’ body image. We drew on social comparison and cultivation theories to explore if exposure to thin and curvy models through Instagram advertising is associated with late-adolescent girls’ willingness to take action to be thinner or curvier, respectively. Two mediation models examined the mechanisms through which any such effects occur. A sample of 284 17-19 year old girls completed self-administered online questionnaires. Results revealed that exposure to thin and curvy models was positively associated with willingness to take action to be thinner and curvier, respectively. These associations were mediated by thin/curvy body preference (model 1), and by thin/curvy body preference, upward physical appearance comparisons, and body dissatisfaction (model 2). Results suggest that although exposure to different body types may be associated with different types of unhealthy (body-altering) actions, the processes underlying these effects are similar. This research highlights possible cultural shifts toward more diverse body ideals and informs tailored body concern interventions and media literacy programs.

Keywords:

Introduction

Advertising is commonly used to generate sales, and physically attractive models are often used to capture audiences’ attention and enhance product preference, resulting in increased purchase intention and actual purchase. However, in addition to promoting products, advertisements play an important role in establishing beauty standards, which, in turn, can affect how viewers evaluate themselves and their self-assessed worthiness (Sohn & Youn, Citation2013). Until recently, thin models have been featured in most traditional media advertising, with advertisers operating on the notion that “‘thinness’ sells, whereas ‘fatness’ does not” (Halliwell & Dittmar, Citation2004, p. 105). Researchers have found that exposure to thin model advertising predicts increased body dissatisfaction (e.g., Bury et al., Citation2017), which in turn may be associated with dieting, disordered eating, or a compulsive need for excessive exercise (Johnson & Wardle, Citation2005; Stice, Citation2002; White & Halliwell, Citation2010). More recently, Instagram has emerged as a popular advertising vehicle where brands feature diverse model body types, possibly more so than traditional media advertisements. Reflecting a possible cultural shift toward the appreciation of curvaceous bodies as an ideal by women (Hunter et al., Citation2021), “curvy” models (large breasts and buttocks, wide hips, and a small waist) are gaining popularity in Instagram advertising, with fashion brands such as Fashion Nova and Missy Empire featuring them.

Despite the rising popularity and visibility of curvy models, little research has explored the associations between curvy model exposure on image-based interactive social media platforms such as Instagram and adolescent girls’ body-related variables such as body preferences and body (dis)satisfaction. To supplement the current literature, we examined the associations between exposure to thin and curvy models through Instagram advertising and late-adolescent girls’ willingness to take actions (dieting and exercising) to be thinner and actions (surgical modifications) to be curvier. Our study focused on girls aged 17-19 years because research on late-adolescence (Colarusso, Citation1992) and the partially overlapping period that follows, “emerging adulthood” (18-25 years: Arnett, Citation2000), indicates that body dissatisfaction (Bucchianeri et al., Citation2013), and harmful behaviors such as dieting and disordered eating (e.g., Neumark-Sztainer et al., Citation2011), may intensify in girls as they transition into young adulthood. During this same developmental period, Instagram use is increasingly common, with many young women spending long periods of time viewing and following others such as peers, celebrities, and models, thus allowing for continuous exposure to unrealistic and edited images of attractive others (Baker et al., Citation2019).

Instagram as an Advertising Vehicle

Instagram has recently become one of the most popular social media platforms, currently hosting over 1.2 billion users Worldwide (Statista, Citation2022). Due to its visual appeal and broad reach, Instagram is one of the most preferred channels for companies to carry out marketing activities, with a growing number of brands using this platform to establish a presence, communicate with consumers (Bashir et al., Citation2018), and showcase their products through photos, videos and stories (Casaló et al., Citation2020). Instagram reportedly earned approximately $20 billion in advertising revenue in 2019 (Frier & Grant, Citation2020).

Several features distinguish Instagram as an advertising vehicle from its traditional media counterparts. First, on digital media (e.g., Instagram), users can not only decide whether to receive advertising, but they can also actively seek it out (Dahlen & Rosengren, Citation2016). Recent statistics suggest that 90% of Instagram’s one billion user accounts “follow” at least one business (Instagram, Citation2021). Second, unlike other traditional and social media platforms where large amounts of text accompany images, Instagram is a highly-visual social media (Marengo et al., Citation2018). It operates on the “image first, text second” rule (Lee et al., Citation2015, p. 552), hence placing great emphasis on the images. As images convey information that can be easily comprehended (Mei et al., Citation2008), advertisements on Instagram may be more effective at communicating specific beauty and body ideals. Finally, unlike conventional media, Instagram is interactive, allowing users to “like” and comment on images (in this case, advertisements), with their likes and comments, which are then viewed by other users (Tiggemann & Velissaris, Citation2020). Through these activities, users publicly express their thoughts, not only about advertised products but also about the models’ appearances. These features may reinforce the target’s (e.g., model’s) attractiveness and persuade users to adopt attitudes consistent with other users, affecting viewers’ perceptions of how ideal particular bodies are (e.g., Fardouly et al., Citation2017; Kim, Citation2021). Thus, models featured in Instagram advertisements may be instrumental in defining body image ideals.

Research has shown that exposure to various content on Instagram is associated with negative body-related outcomes in women and girls. For example, Brown and Tiggemann (Citation2016) found that exposure to attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram increased body dissatisfaction (relative to travel images) in female undergraduate students, and Prichard et al. (Citation2020) found that exposure to fitspiration images led to significantly higher body dissatisfaction (relative to exposure to travel images) in women. Though many studies have explored the effects of exposure to various types of Instagram images/content on women’s and girls’ body image (e.g., Casale et al., Citation2021; Cha et al., Citation2022; Tiggemann & Anderberg, Citation2020), the associations between exposure to Instagram advertising images and adolescent girls’ body-related outcomes are largely unexplored.

Thin Models in Advertising

For long, thinness has been linked to attractiveness in many cultures (Andersen & Paas, Citation2014) and has been regarded as the “cultural ideal for females” (Killen et al., Citation1994, p. 228). Previous research suggests that media often emphasize and encourage individuals to achieve a thin ideal through advertising or appearance-related products (Yu, Citation2014). Much evidence suggests that exposure to thin models (e.g., in advertising) may lead to negative body-related consequences in women, such as body-focused anxiety, poor appearance and body satisfaction, and negative body image (Clayton et al., Citation2017; Groesz et al., Citation2002; Halliwell & Dittmar, Citation2004; Mulgrew et al., Citation2020).

Cultivation and social comparison theories may explain these negative effects of thin model exposure. Developed by George Gerbner in the 1960s and later expanded by Gerbner and Gross (Citation1976), cultivation theory is based on the premise that reality perceptions are cultivated by media content that individuals are exposed to over time (Nabi & Sullivan, Citation2001). The theory proposes that the more individuals are exposed to particular media content, the more likely they are to adopt attitudes, beliefs, and perceptions consistent with the media messages embedded in this content. Thus, the theory predicts that repeated exposure to a specific body type leads viewers to over-estimate the prevalence of such bodies and to develop a false sense of reality in which these bodies are perceived to be normative, expected, central to female attractiveness, and worthy of attention. The viewing of one’s own body as not measuring up to such ideals could contribute to body dissatisfaction and the willingness to engage in appearance-altering practices to meet such ideals (Grabe et al., Citation2008).

According to social comparison theory (Festinger, Citation1954), individuals engage in comparisons with others to develop an accurate evaluation of the self on some attributes for which objective criteria are lacking. Contemporary versions of the theory maintain, first, that comparisons are made not only against people similar to oneself but also against individuals who are much different, and second, that social comparisons against others is often based on aspects of physical appearance. While social comparisons can be upward (comparisons with better-off others), downward (comparisons with worse-off others), or lateral (comparisons with similar others) (Festinger, Citation1954; Morrison et al., Citation2004; Taylor & Lobel, Citation1989), typically women compare their appearances upwardly to other women (e.g., models in advertising) whom they perceive to be thinner and more physically attractive than themselves (Hendrickse et al., Citation2021). Research has demonstrated that such appearance comparisons can increase body dissatisfaction as such appearances are largely unachievable (Diedrichs & Lee, Citation2011). Other research suggests that individuals who subscribe to a thin body ideal may choose to diet or exercise (Markey & Markey, Citation2005; Strelan et al., Citation2003) as a means to achieve a thinner body. While numerous studies have explored how exposure to thin models can, through social comparison processes, negatively affect women’s and girls’ body image, the consequences of exposure to thin models through Instagram advertising have been less commonly explored.

Curvy Models in Advertising

Recently a curvy body type, characterized by a small waist, large butt, breasts, and thighs, has been popularized in White-centered mainstream media (McComb & Mills, Citation2022b). The preference for a curvy ideal may have stemmed from the prominence of this body type in pop culture, with famous media personalities such as Rihanna, Kim Kardashian, and Beyoncé all having curvy bodies (Hunter et al., Citation2021). As Aniulis et al. (Citation2021) note, the media and advertising tend to make use of whatever is the current iconic body types or those with a similar esthetic, and, as exposure to these body types increases, conceptualization of what is considered an ideal body narrows.

While some researchers have explored the curvy body ideal in the body image context, the number of studies exploring this ideal is few compared to studies exploring the thin ideal. A database search conducted by Hunter et al. (Citation2021) found that while the term “thin ideal” returned 741 articles published between 1986 and 2019, the term “curvy ideal” returned just six articles (2001- 2017), “curvy body” returned 32 articles (1997-2018), and “curvaceous body” returned fourteen articles (1987-2017). The authors contrasted this to a Google search on “how to get a curvier body”, which returned 1,720,000 results demonstrating that the desire for a curvy body shape is prevalent in popular culture (Hernández et al., Citation2021).

The limited research published on the curvy ideal suggests that the desire for this body shape may be related to a range of negative consequences. For instance, Hernández et al. (Citation2021) found women’s subscription to an hourglass body shape ideal was correlated with measures of appearance orientation, overweight preoccupation, and body dissatisfaction. Moreover, McComb and Mills (Citation2022a) found that there were no differences between women who aspire to the curvy (referred to as “slim-thick”) ideal and those who aspire to the thin ideal in terms of factors such as weight and shape concerns, appearance-ideal internalization, physical appearance perfectionism, or body image investment, thus suggesting that women who aspire to the curvy body ideal may be just as at risk of negative outcomes as those who aspire to the thin ideal. Furthermore, Overstreet et al. (Citation2010) demonstrated that for women who desired curvaceous body shapes, when their bodies did not match their ideal, there was a high rate of body dissatisfaction.

The negative outcomes associated with the curvy ideal may be explained by social comparison processes. For instance, an experiment by Betz et al. (Citation2019) found that for women who have a tendency to socially compare, exposure to curvy ideals increased state social comparison and was negatively associated with body image outcomes. The authors argue that such findings suggest that women who engage in social comparisons may suffer from similar negative impacts on body image after exposure to curvy ideals as when exposed to thin ideals. Moreover, a recent experiment by McComb and Mills (Citation2022b) found that forced social comparison to curvy (referred to as “slim-thick”) bodies resulted in significantly more weight and appearance dissatisfaction, and less body satisfaction, than did comparisons with thin-ideal imagery. The authors concluded that the drive to achieve body ideals is shifting to a curvier body, and that this may be more detrimental to women’s body image than thin-ideal imagery.

As Instagram is a relatively new platform through which appearance ideals permeate (Prichard et al., Citation2020) and curvy models are featured, women’s and girls’ body image may face new challenges as a thin, toned body with a small waist paired with large breasts and buttocks is unachievable for most women (Hernández et al., Citation2021). For instance, because a curvy body requires fat to be distributed to specific body parts and not others (Romo et al., Citation2016), individuals may resort to surgical modifications to achieve a curvaceous body (Overstreet et al., Citation2010). Many celebrities who emulate the curvy ideal have had surgery to achieve this body type (McComb & Mills, Citation2022b). Data from the American Society of Plastic Surgeons (ASPS., Citation2020) suggest that procedures such as abdominoplasties and buttock lifts have increased exponentially since 2000, and procedures such as buttock implants have increased by over 20% since 2019. Such data call for concern not only because body-altering procedures through surgical modification have become more accessible and common (Hernández et al., Citation2021), but also because of the physical (e.g., scarring, nerve damage, necrosis, arthritis, death) and psychological (e.g., depression, body dysmorphic disorders) risks associated with such procedures (Wen et al., Citation2017).

Several studies have linked various media use and online practices with desires for cosmetic surgery or body modification. For instance, Di Gesto et al. (Citation2022) found that Instagram image-based activities (e.g., posting or watching photos, videos, and stories) related to self and celebrities were directly and indirectly (i.e., mediated through Instagram appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction) related to acceptance of cosmetic surgery among women. Chen et al. (Citation2019) measured the association between social media and photo editing use and attitudes toward cosmetic surgery and found that the use of social media platforms such as Snapchat and Tinder were associated with increased acceptance of cosmetic surgery. Other studies have found that selfie behavior (i.e., taking and posting individual selfies on social networking sites) and selfie editing were associated with cosmetic surgery consideration (Lyu et al., Citation2022; Citation2022; Sun, Citation2021). While several studies have explored possible predictors of cosmetic surgery acceptance, the associations between exposure to ideal body types (i.e., curvy model bodies) through Instagram advertising and individuals’ willingness to engage in specific surgical modification practices have not been investigated.

The Current Study

With the increasing visibility of curvy models in Instagram advertising, it is important to explore whether exposure to thin and curvy models through this advertising are similarly associated with late-adolescent girls’ body-related perceptions and preferences. We expected this exposure to be related to willingness to engage in actions to be thinner or curvier, and we aimed to examine the mechanisms through which such effects occur. To our knowledge, this is the first study to do so in relation to curvy body ideals.

We tested two mediation models. In the first model, preference for a thin (/curvy) body shape was posited to mediate the effects of thin (/curvy) model exposure through Instagram advertising on willingness to take actions to be thinner (/curvier). This model was based on three premises: 1. not all individuals internalize appearance standards to the same degree, and only those who strongly internalize and prefer unrealistic ideals feel compelled to achieve the ideal (Piccoli et al., Citation2022); 2. consistent with cultivation theory, and Stein et al. (Citation2021), frequent exposure to a body ideal (for example, through Instagram advertising) leads viewers to believe that such an ideal is representative of the societal norm, thus leading to its internalization and a preference for one’s own body to match this ideal, and 3. discrepancies between this ideal and their own appearance entice viewers to adopt measures to close this gap (Stein et al., Citation2021). Accordingly, we predicted the following indirect effects:

H1: Thin body preference mediates the positive effect of thin model exposure on willingness to take action to be thinner.

H2: Curvy body preference mediates the positive effect of curvy model exposure on willingness to take action to be curvier.

Figure 1. Hypothesized serially mediated model.

Note. For clarity, paths from BMI to all endogenous variables have been omitted.

H3: Thin body preference, upward appearance comparisons, and body dissatisfaction serially mediate the positive effect of thin model exposure on willingness to take action to be thinner.

H4: Curvy body preference, upward appearance comparisons, and body dissatisfaction serially mediate the positive effect of curvy model exposure on willingness to take action to be curvier.

To ensure that the results did not vary with participants’ body size, we controlled for the effects of body mass index (BMI) in all models.

Materials and Methods

Participants

A priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Citation2009) indicated that a total sample size of 279 is needed to detect small-to-medium effect sizes (f22 ∼ .05), assuming an alpha level of .05, power of .80, and multiple regression analyses involving six predictors (i.e., two body exposure variables, two body preference variables, and two additional mediators). The current sample consisted of 284 adolescent girls enrolled in an undergraduate psychology course (Mage = 18.29 years, SD = 0.60) recruited through a research participant pool at an Australian University. Inclusion criteria included identifying as female aged 17-19, being a “regular” Instagram user (defined as spending on average two hours or more on Instagram per week), and not having a diagnosed eating disorder and/or body dysmorphia. Most participants self-identified as White/Caucasian (77.5%), mixed-race (8.8%), or Asian (4.6%). Most (81%) were born in Australia. The mean BMI was 23.21 (SD = 4.12), suggesting that, on average, participants were in the “normal” BMI range (BMI of 18.5–24.9 kg/m2) according to World Health Organization BMI cutoffs (Ottesen et al., Citation2021). Participants received course credits as an incentive for their participation.

Measures

Exposure to Thin and Curvy Models in Instagram Advertising

Participants responded to two original items developed through pilot testing to determine the extent of their exposure to thin and curvy models through Instagram advertising. The items were “How often do you see thin female models featured in Instagram advertisements?” and “How often do you see curvy female models featured in Instagram advertisements?”. Instagram advertising was broadly defined as “any photo or video posts from brands/companies promoting their products, even if the product description/image does not include a price tag, a direct purchase link, an “order now” option, or similar”. Response options ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very frequently). To anchor these response options and provide greater consistency in their interpretation, instructions clarified that “Never” referred to 0% of the advertisements viewed, and “Very frequently” referred to at least 75% of the advertisements viewed. Three example Instagram advertisements featuring models with that body type were provided with each question.

Thin and Curvy Body Preference

Participants’ body type preference was measured through two original items: “I would prefer to have a thin body” and “I would prefer to have a curvy body (large breasts, small waist, and large hips and buttocks)”. Response options ranged from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree).

Upward Physical Appearance Comparisons on Instagram

To measure participants’ upward physical appearance comparison tendencies in response to Instagram, three items from the 10-item Upward Physical Appearance Comparison Scale (UPACS: O’Brien et al., Citation2009) were selected based on (a) relevance to the current study, (b) ease of adaptation, and (c) desire not to overly burden the participants. For example, the original scale item, “I tend to compare my own physical attractiveness to that of magazine models”, was both relevant and easily adaptable for this study. The three items used in this study were “I compare myself to those on Instagram who are better looking than me rather than those who are not”, “I compare my body to people on Instagram who have a better body than me”, and “I tend to compare my own physical attractiveness to that of Instagram models”.

To match responses used elsewhere in the questionnaire, response options ranged from 1 (Never) to 5 (Very frequently). Instructions clarified that “Never” referred to 0% of the occasions participants used Instagram, and “Very frequently” referred to at least 75% of the occasions. Item responses were averaged, with higher scores indicating a greater tendency to compare oneself with targets considered (more) physically attractive on Instagram. The original scale was normed on a sample of Australian male and female University students following established scale development procedures, including conducting a focus group, using a panel of experts, and analyses demonstrating construct validity and test-retest reliability. The scale authors report that the original scale is internally consistent (Cronbach alpha (α) = .94).

Body (Dis)Satisfaction

Three of the six items from the Body Image States Scale (BISS: Cash et al., Citation2002) were selected, based on relevance to the body image focus of the study, to measure participants’ levels of body (dis)satisfaction. The items were “Right now, I feel…with my physical appearance”, “Right now, I feel…with my body size and shape”, and “Right now, I feel…with my weight” on a 9-point scale ranging from 1 (Extremely dissatisfied) to 9 (Extremely satisfied). The scale was normed using a sample of male and female students from a large mid-Atlantic University following standard scale development procedures, including demonstrating its test-retest reliability and concurrent and construct validity. Higher mean scores indicated greater body satisfaction. The scale authors reported the full scale to be internally consistent (neutral condition women’s α = .77).

Willingness to Engage in Different Appearance-Altering Practices

Inspired by items used by Harrison (Citation2003) to measure approval of body-alteration methods, six items were developed to explore participants’ willingness to engage in appearance-altering practices. Participants were asked, “When you think about your appearance, and your body generally, how willing do you think you would be to”, followed by items specifying body shape-altering practices. Response options ranged from 1 (Not at all willing) to 5 (Very willing).

Responses to the six items were subjected to principal components analysis with direct oblimin rotation. As intended, this analysis confirmed a two-factor solution: both eigenvalues > 1.0, with three items loading on each factor > .5. The factors were labeled willingness to take actions to be thinner (shortened to act to be thinner [ATBT]) and willingness to take actions to be curvier (shortened to act to be curvier [ATBC]), respectively. The three ATBT items pertained to a willingness to exercise to lose at least 5% of current body weight, exercise to change body shape, and diet to lose at least 5% of current body weight. The three ATBC items pertained to a willingness to undergo surgery to increase breast size, surgery to increase buttocks size, and surgery to reduce waist size. The factors explained 39.6% (ATBT) and 26.2% (ATBC) of the total variance. Composite scores were created for the two factors by averaging responses to the items that had their primary loadings on each factor. Higher scores indicated a greater willingness to engage in appearance-altering practices to be thinner or curvier, respectively.

Procedure

A pilot study (N = 77), with participants drawn from the population to be sampled in the main study, was conducted to pretest the adapted items and scales. The main study, titled “Instagram advertising and young women’s body image and ideals,” was conducted following the University’s research guidelines and the (Australian) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. The study was announced through a university-operated, online sign-up website. Participants were provided with an access link to a secure hosting website (Lime Survey), where they read an information sheet outlining the details of the study, including the risks involved, their rights to discontinue their participation at any time before questionnaire submission, and relevant support sources. Participants provided online acknowledgement of informed consent and then completed the questionnaire anonymously. The pilot and main studies were completed over a 25-week period beginning in late 2020. The study was part of a larger project that included measures of variables not currently discussed. The median main study questionnaire completion time was approximately 12 min.

Data Analysis

Missing data analysis revealed that five data points were missing in total, with each belonging to a different item across four of the eight study variables. Missing data were imputed using Expectancy Maximization procedures in the case of a single BISS item, and using regression in AMOS with respect to the remaining variables. Descriptive statistics and correlations were computed using SPSS 25.0. Measurement and structural models were tested using AMOS 28. In all structural models, the four multi-item variables were latent, and the four single-item variables were treated as manifest. Model fit was evaluated using the values of chi-square, root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Tucker-Lewis index (TLI) and Bentler’s comparative fit index (CFI). A small and non-significant chi-square value (although in large samples, chi-square will almost always be significant: Hox & Bechger, Citation1998), and an RMSEA < .08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999), are considered acceptable. For CFI (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999) and TLI (Hox & Bechger, Citation1998), a value >.90 indicates adequate fit, and >.95 indicates good fit. To test the significance of the indirect effects, 95% bias-corrected confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using a 5000-sample bootstrapping procedure.

Results

Preliminary Analyses

displays the descriptive statistics and correlations between the study variables. All scales demonstrated adequate or higher levels of internal consistency. While participants reported greater exposure to thin than to curvy models, t(283) = 17.04, p = .000, the mean scores for the two body preference variables did not differ, t(283) = 0.80, p = .425. As expected, significant positive correlations were found between exposure to thin and curvy models through Instagram advertising and late-adolescent girls’ willingness to engage in actions to be thinner or curvier, respectively. Furthermore, significant positive associations were observed between thin model exposure and thin body preference, and between curvy model exposure and curvy body preference. Both thin and curvy body preferences were significantly positively associated with UPACS (upward physical appearance comparison). UPACS was significantly negatively correlated with BISS (body satisfaction). Finally, BISS was significantly negatively correlated with ATBT (act to be thinner) and ATBC (act to be curvier). Thus, all correlations were as expected.

Table 1. Descriptive Statistics and Correlations among All Research Variables.

Measurement Model

Prior to testing the hypothesized mediation models, a measurement model capturing the four latent variables (UPACS, BISS, ATBT, and ATBC) and the 12 observed indicators of these variables was evaluated. The standardized factor loadings for all items were significant and above .6, except one item each from ATBT (exercise with the aim of changing the shape of certain body part/s) and ATBC (undergo surgery to increase breast size), which had loadings of .33 and .37, respectively. These two items were retained in accord with the three-indicator rule (Kline, Citation2005) and because they tapped into important and unique content, thus providing better operationalizations of the constructs.

While the fit of the hypothesized measurement model was acceptable, χ2(48) = 153.31, p < .001, CFI = .95, TLI = .94, RMSEA = .088, examination of the item content suggested that the errors associated with two ATBC items (undergoing surgery to increase breast size and undergoing surgery to increase buttocks size) may be susceptible to a common error, possibly related to an aversion to surgically implanting extraneous body mass. The correlation between the two errors was .30 (p = .001), and the modification index exceeded 10.0. Thus, the measurement model was rerun with this single error covariance freed. The revised model revealed a good fit to the data, χ2(47) = 132.71, p < .001, Δχ2(1) = 20.60, p < .05, CFI = .96, TLI = .95, RMSEA = .080. All structural models retained this error covariance.

Structural Models

The first structural model tested was the hypothesized simple model, in which thin body preference was predicted to mediate the association between thin model exposure and ATBT, and curvy body preference was expected to mediate the connection between curvy model exposure and ATBC. While this model did not provide an adequate fit, χ2(37) = 124.28, p < .001, CFI = .88, TLI = .82, RMSEA = .091, the path coefficients for all hypothesized direct effects were positive and significant. Thin model exposure had a positive direct association with thin body preference (B = .39, β = .25, p < .001) and thin body preference was positively related to ATBT (B = .14, β = .38, p < .001). Conversely, curvy model exposure had a positive direct association with curvy body preference (B = .23, β = .18, p = .011), and curvy body preference was positively related to ATBC (B = .25, β = .07, p = .019). BMI was positively related to ATBT (B = .04, β = .45, p < .001) and negatively related to ATBC (B = −0.04, β = −0.04, p = .015), but was unrelated to thin and curvy body preference. Importantly, there was a positive indirect effect of thin model exposure on ATBT, via thin body preference, thus supporting hypothesis 1. A positive indirect effect of curvy model exposure on ATBC, through curvy body preference, was also found, supporting hypothesis 2. Details of the indirect effects for all models can be found in .

Table 2. Indirect Effects for All Hypothesized and Alternative Models.

To check that the model cannot be improved by including additional paths, two alternatives to the hypothesized simple mediation model were then evaluated. First, paths from thin model exposure to curvy body preference and from curvy model exposure to thin body preference were added. As expected, model fit did not improve χ2(35) = 124.23, p < .001, Δχ2(2) = 0.05 (ns), ΔCFI = .00, ΔTLI = −0.02, and RMSEA = .095, with the direction of the change in the latter two indices indicating a poorer fit. Neither of the added direct paths was significant (ps > .80), while both the originally hypothesized indirect paths remained significant. See . In the second alternative model, direct paths from thin model exposure to ATBT and from curvy model exposure to ATBC were added to the hypothesized model. Model fit improved marginally when chi-squared values were compared, χ2(35) = 117.50, p < .001, Δχ2(2) = 6.78, p < .05, but showed no improvement using the other fit statistics, ΔCFI = .00, ΔTLI = .00, ΔRMSEA = .000. While a positive direct relation was found between curvy model exposure and ATBC (B = .14, β = .06, p = .049), thin model exposure was not directly associated with ATBT (B = .04, β = .07, p = .16). The originally hypothesized indirect paths remained significant.

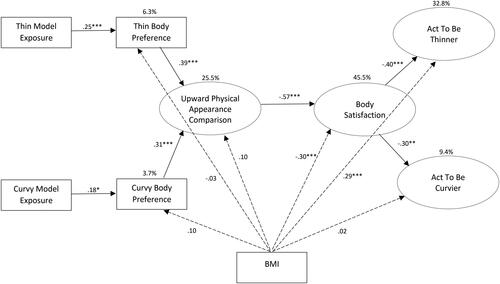

We then tested the serial mediation model. Unlike the first hypothesized model, this model demonstrated an adequate fit to the data, χ2(107) = 312.45, p < .001, CFI = .92, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .08. presents the standardized path coefficients. As shown, all hypothesized direct paths were significant. BMI was positively related to ATBT (act to be thinner) and negatively related to BISS (body satisfaction), but was unrelated to thin and curvy body preference, UPACS (upward physical appearance comparison), and ATBC (act to be curvier). Importantly, there was a significant indirect effect (see ) from thin model exposure to ATBT via thin body preference, UPACS, and BISS, thus confirming our third hypothesis. A significant indirect effect of curvy model exposure on ATBC via curvy body preference, UPACS, and BISS was also found, confirming our fourth hypothesis.

Figure 2. Serial mediation model with standardized path coefficients and percentages of explained variance.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001; p-values were obtained from bias-corrected bootstrap sampling.

Three alternatives to the hypothesized serial mediation model were evaluated. First, paths from thin model exposure to curvy body preference and from curvy model exposure to thin body preference were added. As expected, model fit did not improve, χ2(105) = 312.40, p < .001, Δχ2(2) = 0.05 (ns), ΔCFI = .00, ΔTLI = −0.01, RMSEA = .084 (an increase of .002). Neither of the two added paths was significant (ps > .80), while both the originally hypothesized indirect paths remained so. In the second alternative model, direct paths from thin model exposure to ATBT and from curvy model exposure to ATBC were added to the hypothesized model. Model fit improved marginally when chi-squared values were compared, χ2(105) = 306.11, p < .001, Δχ2(2) = 6.34, p < .05, but showed no improvement using the other fit statistics, ΔCFI = .00, ΔTLI = .00, ΔRMSEA = .00. There was no direct association between curvy model exposure and ATBC (B = .07, β = .10, p = .25) or between thin model exposure and ATBT (B = .07, β = .11, p = .07). The originally hypothesized indirect paths remained significant.

In the third alternative model, direct paths from thin body preference to ATBT and from curvy body preference to ATBC were added to the hypothesized serial mediation model. To achieve an admissible converged solution for this model, the covariance between the errors in the two ATBC indicators was fixed at the value (.317) obtained in the hypothesized model. Model fit improved, χ2(106) = 279.15, p < .001, Δχ2(1) = 33.31, p < .05, ΔCFI = .01, ΔTLI = .01, ΔRMSEA = .006. There was a direct association between thin body preference and ATBT (B = .12, β = .31, p < .001), although not between curvy body preference and ATBC (B = −0.02, β = −0.05, p = .21). The originally hypothesized indirect path from thin model exposure on ATBT (act to be thinner), via thin body preference, UPACS (upward physical appearance comparison), and BISS (body satisfaction) was significant, but there was no indirect effect of curvy model exposure on ATBC (act to be curvier) through curvy body preference, UPACS, and BISS. See .

Discussion

We drew on social comparison and cultivation theories to explore if and how exposure to thin and curvy models depicted in Instagram advertising is associated with late-adolescent girls’ willingness to engage in actions to be thinner or curvier, respectively. Previous studies have demonstrated that exposure to advertising featuring thin models may have negative body-related consequences for women and girls. The current study extends that literature in three ways: 1) by focusing on advertising shown on a highly visual and interactive social media platform, Instagram, 2) by identifying correlates of exposure to two body types, that is, curvy models and thin models, and 3) by investigating an under-researched consequence of curvy model exposure, namely, willingness to accept surgical interventions targeting the curvy ideal.

Exposure to thin and curvy models was positively associated with the willingness to take action to be thinner and curvier, respectively. This finding suggests that individuals exposed to Instagram advertisements, particularly those featuring thin and curvy models, may feel emboldened to pursue a potentially self-destructive course in pursuit of a potentially unattainable goal. The results pertaining to thin models, and those pertaining to curvy models, are equally important. First, the finding suggesting that exposure to thin models may contribute to late-adolescent girls’ willingness to engage in acts such as dieting is of concern as disordered eating behaviors, including dietary restrictions, are common symptoms of eating disorders (Zhang et al., Citation2021). Second, despite various risks associated with cosmetic surgery, its popularity as a form of beautification is growing (Bonell et al., Citation2021). Researchers are seeking to discover factors that help explain the widespread acceptance of this surgery (e.g., Di Gesto et al., Citation2022), and current findings suggest that exposure to curvy models through Instagram advertising may be one such factor.

The study also found that greater exposure to thin and curvy models was related to a greater preference for that body type. This finding is interesting in light of research showing that preference for body ideals differs with ethnicity, with Black and Latina women and girls often preferring curvaceous bodies (Kelch-Oliver & Ancis, Citation2011; Romo et al., Citation2016), and White women generally preferring thinner ideals (e.g., Perez & Joiner, Citation2003). In contrast, the findings from this study’s predominantly White sample, especially the non-significant difference between preferences for thin and curvy models, add weight to the argument that ideals may be shifting and that body types other than thin ones may be valued by girls in contemporary society regardless of race/ethnicity. This outcome is consistent with central propositions of cultivation theory, that is, repeated exposure to curvy models in Instagram advertising may serve to build and reinforce attitudes toward such bodies (Kinnally & Van Vonderen, Citation2014) becoming increasingly popular, attractive, and desired.

A key finding was that while thin body preference mediated the connection between thin model exposure and the willingness to engage in actions to be thinner, curvy body preference mediated the connection between curvy model exposure and the willingness to take actions to be curvier. This finding is consistent with the argument that while most individuals may be aware of beauty standards, only those who strongly internalize these standards feel compelled to achieve these ideals (Piccoli et al., Citation2022). This finding can help inform future educational and prevention programs to reduce girls’ internalization of unrealistic ideals, which in turn can combat other potential negative body-related consequences.

We proposed an extended mediation model in which upward physical appearance comparisons and body dissatisfaction served as additional mediators of the associations between model exposure and late-adolescent girls’ willingness to take appearance-modifying actions. Findings pertaining to this hypothesized model showed that (thin/curvy) body preference, upward physical appearance comparisons, and body dissatisfaction serially mediated the connections between exposure and willingness to take actions to modify one’s appearance. This extended mediation pathway was confirmed in all models when exposure was to thin bodies, and in all but one model when exposure was to curvy bodies. These results suggest that although exposure to varying body types (possibly including athletic and plus-size bodies) may lead to different unhealthy behaviors, the processes underlying these relations may be the same.

Implications

There are several implications of this research. The study draws attention to the need for policies and practices that address challenges arising from the proliferation of newer advertising vehicles and body ideals. In particular, the study highlights the need for future prevention and intervention efforts related to body image and eating disorders to reference curvy and other body types featured in advertising on Instagram and other social media platforms. While these interventions may draw on past efforts that focused on the thin ideal, relying too heavily on these precedents could narrow thinking regarding ways to effectively intervene and treat problems arising from different body ideal conceptualizations (Hunter et al., Citation2021). Similarly, intervention strategies that draw on approaches that have worked in the past to counter messages presented via traditional media, while potentially offering useful starting points, may need to be reconsidered given the opportunities for user interaction, visual immersion, and the self-selection of content provided by newer media. Psycho-educational and media literacy programs must teach girls to critically interpret and negotiate unrealistic ideas about female beauty, including ideas about unrealistically curvy bodies, and help build more positive self-images and appearance management behavior. Unrealistic perceptions of normality that have been formed through repeated exposure to brands and images that promote the curvy body ideal, and that are reinforced through upward physical appearance comparisons, need to be challenged, and vulnerable individuals may need help in developing realistic views of normal and ideal bodies (Glauert et al., Citation2009). Finally, a fundamental point underpinning this study is that, while advertisements on Instagram are designed to sell particular products and services, they may, through their inadvertent promotion of extreme body ideals, change patterns of consumption and create demand for a range of “body-related” products and services, including food and beverages, surgical and non-surgical medical and beauty treatments, exercise equipment, gym memberships, and licit and illicit drugs, all in search of a body ideal. Thus, this study has clear implications for the maintenance or strengthening of relevant advertising standards.

Limitations and Future Research

As with any study, the present findings should be interpreted in the context of some limitations. First, as participants were young, predominantly White Australian University students, the results may not generalize to other populations. Future researchers should recruit more diverse samples varying in identity and demographic factors such as age, race, ethnicity, and education, to more fully explain susceptibilities to Instagram advertising. Second, the measures of ATBT and ATBC currently used have not been validated, and could potentially be refined and strengthened in future studies. Third, having used a cross-sectional design that generated correlational data only, claims of causation cannot be made. Nonetheless, the study was useful in documenting associations between body image variables and frequency of exposure over time to different body types via Instagram advertising. To identify body-related consequences of shorter-term exposure, studies should experimentally manipulate user exposure to Instagram advertisements that feature thin or curvy models. Similarly, cross-sectional designs have well-known limitations as a source of evidence regarding mediation, although, to partly overcome this weakness, in the present study, we controlled for BMI and we tested the robustness of our hypothesized mediation models by comparing their fit with that of several alternative models. Finally, participants’ responses may have been subject to a range of response and recall biases. Participants may, for example, have over-estimated the frequency with which they were exposed to images that are particularly vivid or recent and/or may not have been able to correctly remember how often they saw advertisements featuring less salient body types. While efforts were made to counteract these problems by providing participants with clear instructions, definitions, and example images, future researchers should make use of daily diaries or similar approaches to facilitate accurate recall.

Conclusions

This research is the first known study to investigate the potential consequences of exposure to Instagram advertising featuring thin and curvy models on late-adolescent girls’ body image. The study contributes to ongoing discussions regarding if and how advertising exposure contributes to late-adolescent girls’ body image. Importantly, it extends advertising research into Instagram, a visually based social media platform with limited current research in this context. This study indicates that regardless of the model body type represented in advertisements (thin or curvy), if the body type is preferred (internalized) and upward comparisons are made to it, this could lead to feelings of body dissatisfaction and willingness to take unhealthy body-altering actions. If borne out in future research, the finding that this process unfolds in similar ways in response to different body types does not bode well for the idea that adding diversity in advertising will counteract negative outcomes.

Ethical Approval Statement

Research was conducted following Griffith University’s research guidelines and the (Australian) National Statement on Ethical Conduct in Human Research. [GU ref no: 2021/212].

Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all participants of the study. Participants were informed that completion and submission of the questionnaire would be taken as their informed consent to participate in the study.

Author notes

Jannatul Shimul Ferdousi is currently a Ph.D. candidate in the School of Applied Psychology at Griffith University (Queensland, Australia), where her research combines marketing and psychology to explore the association between exposure to Instagram advertisements and the female body image. She has a BCom in marketing (University of Pretoria, South Africa), an MBA (American International University Bangladesh), and an MSc in Marketing (Stockholm Business School, Sweden). She also has experience working with branding and advertising.

Graham Bradley is an associate professor in the School of Applied Psychology, Griffith University. Many of his research interests relate to psychosocial development during the second and third decades of life. Recent studies have focused on social media influences on body image and body concerns. His work has been published in the Journal of Adolescence, Journal of Youth and Adolescence, Body Image, and Psychology of Women Quarterly.

Dr Joan Carlini is a senior lecturer within the Department of Marketing in the Griffith Business School, Griffith University. Her work specializes in the intersection of business, government, and society, with a particular focus on consumer behavior and social responsibility. She has extensive research experience and focuses on high impact projects resulting in social and economic benefits. Her work appears in the Journal of Marketing Management, Journal of Brand Management, Event Management, and Journal of Clinical Nursing.

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, [JSF], upon reasonable request.

Funding

This research did not receive any grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- Andersen, K., & Paas, L. J. (2014). Extremely thin models in print ads: The dark sides. Journal of Marketing Communications, 20(6), 447–464. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2012.723027

- Aniulis, E., Sharp, G., & Thomas, N. A. (2021). The ever-changing ideal: The body you want depends on who else you’re looking at. Body Image, 36, 218–229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.12.003

- Arnett, J. J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. The American Psychologist, 55(5), 469–480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469

- ASPS. (2020). Plastic surgery statistics report. American Society of Plastic Surgeons. https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf

- Baker, N., Ferszt, G., & Breines, J. G. (2019). A qualitative study exploring female college students’ Instagram use and body image. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 22(4), 277–282. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0420

- Bashir, A., Wen, J. T., Kim, E., & Morris, J. D. (2018). The role of consumer affect on visual social networking sites: How consumers build brand relationships. Journal of Current Issues & Research in Advertising, 39(2), 178–191. https://doi.org/10.1080/10641734.2018.1428250

- Betz, D. E., Sabik, N. J., & Ramsey, L. R. (2019). Ideal comparisons: Body ideals harm women’s body image through social comparison. Body Image, 29, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.004

- Bonell, S., Barlow, F. K., & Griffiths, S. (2021). The cosmetic surgery paradox: Toward a contemporary understanding of cosmetic surgery popularisation and attitudes. Body Image, 38, 230–240. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.04.010

- Brown, Z., & Tiggemann, M. (2016). Attractive celebrity and peer images on Instagram: Effect on women’s mood and body image. Body Image, 19, 37–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.08.007

- Bucchianeri, M. M., Arikian, A. J., Hannan, P. J., Eisenberg, M. E., & Neumark-Sztainer, D. (2013). Body dissatisfaction from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Body Image, 10(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2012.09.001

- Bury, B., Tiggemann, M., & Slater, A. (2017). Disclaimer labels on fashion magazine advertisements: Does timing of digital alteration information matter? Eating Behaviors, 25, 18–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eatbeh.2016.08.010

- Casale, S., Gemelli, G., Calosi, C., Giangrasso, B., & Fioravanti, G. (2021). Multiple exposure to appearance-focused real accounts on Instagram: Effects on body image among both genders. Current Psychology, 40(6), 2877–2886. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00229-6

- Casaló, L. V., Flavián, C., & Ibáñez-Sánchez, S. (2020). Influencers on Instagram: Antecedents and consequences of opinion leadership. Journal of Business Research, 117, 510–519. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.005

- Cash, T. F., Fleming, E. C., Alindogan, J., Steadman, L., & Whitehead, A. (2002). Beyond body image as a trait: The development and validation of the Body Image States Scale. Eating Disorders, 10(2), 103–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/10640260290081678

- Cha, H. S., Mayers, J. A., & Stutts, L. A. (2022). The impact of curvy fitspiration and fitspiration on body dissatisfaction, negative mood, and weight bias in women. Stigma and Health, 7(2), 226–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000367

- Chen, J., Ishii, M., Bater, K. L., Darrach, H., Liao, D., Huynh, P. P., Reh, I. P., Nellis, J. C., Kumar, A. R., & Ishii, L. E. (2019). Association between the use of social media and photograph editing applications, self-esteem, and cosmetic surgery acceptance. JAMA Facial Plastic Surgery, 21(5), 361–367. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamafacial.2019.0328

- Clayton, R. B., Ridgway, J. L., & Hendrickse, J. (2017). Is plus size equal? The positive impact of average and plus-sized media fashion models on women’s cognitive resource allocation, social comparisons, and body satisfaction. Communication Monographs, 84(3), 406–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637751.2017.1332770

- Colarusso, C. A. (1992). Adolescence (ages 12-20). In Child and adult development: A psychoanalytic introduction for clinicians (pp. 91–105). Plenum Press.

- Dahlen, M., & Rosengren, S. (2016). If advertising won’t die, what will it be? Toward a working definition of advertising. Journal of Advertising, 45(3), 334–345. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.2016.1172387

- Di Gesto, C., Nerini, A., Policardo, G. R., & Matera, C. (2022). Predictors of acceptance of cosmetic surgery: Instagram images-based activities, appearance comparison and body dissatisfaction among women. Aesthetic Plastic Surgery, 46(1), 502–512. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00266-021-02546-3

- Diedrichs, P. C., & Lee, C. (2011). Waif goodbye! Average-size female models promote positive body image and appeal to consumers. Psychology & Health, 26(10), 1273–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2010.515308

- Fardouly, J., Pinkus, R. T., & Vartanian, L. R. (2017). The impact of appearance comparisons made through social media, traditional media, and in person in women’s everyday lives. Body Image, 20, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2016.11.002

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Buchner, A., & Lang, A.-G. (2009). Statistical power analyses using G* Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behavior Research Methods, 41(4), 1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

- Festinger, L. (1954). A theory of social comparison processes. Human Relations, 7(2), 117–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872675400700202

- Frier, S., Grant, N. (2020). Instagram brings in more than a quarter of Facebook sales. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-02-04/instagram-generates-more-than-a-quarter-of-facebook-s-sales

- Gerbner, G., & Gross, L. (1976). Living with television: The violence profile. Journal of Communication, 26(2), 172–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-2466.1976.tb01397.x

- Glauert, R., Rhodes, G., Byrne, S., Fink, B., & Grammer, K. (2009). Body dissatisfaction and the effects of perceptual exposure on body norms and ideals. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 42(5), 443–452. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.20640

- Grabe, S., Ward, L. M., & Hyde, J. S. (2008). The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychological Bulletin, 134(3), 460–476. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460

- Groesz, L. M., Levine, M. P., & Murnen, S. K. (2002). The effect of experimental presentation of thin media images on body satisfaction: A meta-analytic review. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 31(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10005

- Halliwell, E., & Dittmar, H. (2004). Does size matter? The impact of model’s body size on women’s body-focused anxiety and advertising effectiveness. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(1), 104–122. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.1.104.26989

- Harrison, K. (2003). Television viewers’ ideal body proportions: The case of the curvaceously thin woman. Sex Roles, 48(5-6), 255–264. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022825421647

- Hendrickse, J., Clayton, R. B., Ray, E. C., Ridgway, J. L., & Secharan, R. (2021). Experimental effects of viewing thin and plus-size models in objectifying and empowering contexts on Instagram. Health Communication, 36(11), 1417–1425. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2020.1761077

- Hernández, J. C., Gomez, F., Stadheim, J., Perez, M., Bekele, B., Yu, K., & Henning, T. (2021). Hourglass Body Shape Ideal Scale and disordered eating. Body Image, 38, 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.03.013

- Hox, J. J., & Bechger, T. M. (1998). An introduction to structural equation modeling. Family Science Review, 11, 354–373.

- Hu, L.-T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

- Hunter, E. A., Kluck, A. S., Ramon, A. E., Ruff, E., & Dario, J. (2021). The Curvy Ideal Silhouette Scale: Measuring cultural differences in the body shape ideals of young U.S. women. Sex Roles, 84(3-4), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01161-x

- Instagram. (2021). Instagram business. Instagram for Business. https://business.instagram.com/

- Johnson, F., & Wardle, J. (2005). Dietary restraint, body dissatisfaction, and psychological distress: A prospective analysis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), 119–125. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.119

- Kelch-Oliver, K., & Ancis, J. R. (2011). Black women’s body image: An analysis of culture-specific influences. Women & Therapy, 34(4), 345–358. https://doi.org/10.1080/02703149.2011.592065

- Killen, J. D., Taylor, C. B., Hayward, C., Wilson, D. M., Haydel, K. F., Hammer, L. D., Simmonds, B., Robinson, T. N., Litt, I., Varady, A., & Kraemer, H. (1994). Pursuit of thinness and onset of eating disorder symptoms in a community sample of adolescent girls: A three-year prospective analysis. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 16(3), 227–238. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-108X(199411)16:3 < 227::AID-EAT2260160303 > 3.0.CO;2-L

- Kim, H. M. (2021). What do others’ reactions to body posting on Instagram tell us? The effects of social media comments on viewers’ body image perception. New Media & Society, 23(12), 3448–3465. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444820956368

- Kinnally, W., & Van Vonderen, K. E. (2014). Body image and the role of television: Clarifying and modelling the effect of television on body dissatisfaction. Journal of Creative Communications, 9(3), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1177/0973258614545016

- Kline, R. B. (2005). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Lee, E., Lee, J.-A., Moon, J. H., & Sung, Y. (2015). Pictures speak louder than words: Motivations for using Instagram. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18(9), 552–556. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2015.0157

- Lyu, Z., Jiao, Y., Zheng, P., & Zhong, J. (2022). Why do selfies increase young women’s willingness to consider cosmetic surgery in China? The mediating roles of body surveillance and body shame. Journal of Health Psychology, 27(5), 1205–1217. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105321990802

- Lyu, Z., Wang, Y., Chen, C., & Zheng, P. (2022). Selfie behavior and cosmetic surgery consideration in adolescents: The mediating roles of physical appearance comparisons and facial appearance concern. Psychology, Health & Medicine, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13548506.2022.2148699

- Marengo, D., Longobardi, C., Fabris, M. A., & Settanni, M. (2018). Highly-visual social media and internalizing symptoms in adolescence: The mediating role of body image concerns. Computers in Human Behavior, 82, 63–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.01.003

- Markey, C. N., & Markey, P. M. (2005). Relations between body image and dieting behaviors: An examination of gender differences. Sex Roles, 53(7-8), 519–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-005-7139-3

- McComb, S. E., & Mills, J. S. (2022a). Eating and body image characteristics of those who aspire to the slim-thick, thin, or fit ideal and their impact on state body image. Body Image, 42, 375–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.07.017

- McComb, S. E., & Mills, J. S. (2022b). The effect of physical appearance perfectionism and social comparison to thin-, slim-thick-, and fit-ideal Instagram imagery on young women’s body image. Body Image, 40, 165–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.12.003

- Mei, T., Hua, X.-S., & Li, S. (2008, October). Contextual in-image advertising [Paper presentation]. In MM ‘08: Proceedings of the 16th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada pp. 439–448. https://doi.org/10.1145/1459359.1459418

- Morrison, T. G., Kalin, R., & Morrison, M. A. (2004). Body-image evaluation and body-image investment among adolescents: A test of sociocultural and social comparison theories. Adolescence, 39(155), 571–592.

- Mulgrew, K. E., Schulz, K., Norton, O., & Tiggemann, M. (2020). The effect of thin and average-sized models on women’s appearance and functionality satisfaction: Does pose matter? Body Image, 32, 128–135. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.12.004

- Nabi, R. L., & Sullivan, J. L. (2001). Does television viewing relate to engagement in protective action against crime? A cultivation analysis from a theory of reasoned action perspective. Communication Research, 28(6), 802–825. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365001028006004

- Neumark-Sztainer, D., Wall, M., Larson, N. I., Eisenberg, M. E., & Loth, K. (2011). Dieting and disordered eating behaviors from adolescence to young adulthood: Findings from a 10-year longitudinal study. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 111(7), 1004–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jada.2011.04.012

- O'Brien, K. S., Caputi, P., Minto, R., Peoples, G., Hooper, C., Kell, S., & Sawley, E. (2009). Upward and downward physical appearance comparisons: Development of scales and examination of predictive qualities. Body Image, 6(3), 201–206. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2009.03.003

- Ottesen, T. D., Bagi, P. S., Malpani, R., Galivanche, A. R., Varthi, A. G., & Grauer, J. N. (2021). Underweight patients are an often under looked “At risk” population after undergoing posterior cervical spine surgery. North American Spine Society Journal, 5, 100041. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xnsj.2020.100041

- Overstreet, N. M., Quinn, D. M., & Agocha, V. B. (2010). Beyond thinness: The influence of a curvaceous body ideal on body dissatisfaction in Black and White women. Sex Roles, 63(1-2), 91–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9792-4

- Perez, M., & Joiner, T. E.Jr, (2003). Body image dissatisfaction and disordered eating in black and white women. The International Journal of Eating Disorders, 33(3), 342–350. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.10148

- Piccoli, V., Carnaghi, A., Grassi, M., & Bianchi, M. (2022). The relationship between Instagram activity and female body concerns: The serial mediating role of appearance-related comparisons and internalization of beauty norms. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 32(4), 728–743. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.2586

- Prichard, I., Kavanagh, E., Mulgrew, K. E., Lim, M. S. C., & Tiggemann, M. (2020). The effect of Instagram #fitspiration images on young women’s mood, body image, and exercise behaviour. Body Image, 33, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.02.002

- Romo, L. F., Mireles-Rios, R., & Hurtado, A. (2016). Cultural, media, and peer influences on body beauty perceptions of Mexican American adolescent girls. Journal of Adolescent Research, 31(4), 474–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/0743558415594424

- Sarwer, D. B. (2019). Body image, cosmetic surgery, and minimally invasive treatments. Body Image, 31, 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.01.009

- Sohn, S. H., & Youn, S. (2013). Does she have to be thin? Testing the effects of models’ body sizes on advertising effectiveness. Atlantic Journal of Communication, 21(3), 164–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/15456870.2013.803109

- Statista. (2022). Number of Instagram users worldwide from 2020 to 2025 [Infographic]. https://www.statista.com/statistics/183585/instagram-number-of-global-users/

- Stein, J.-P., Krause, E., & Ohler, P. (2021). Every (Insta)Gram counts? Applying cultivation theory to explore the effects of Instagram on young users’ body image. Psychology of Popular Media, 10(1), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000268

- Stice, E. (2002). Risk and maintenance factors for eating pathology: A meta-analytic review. Psychological Bulletin, 128(5), 825–848. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.128.5.825

- Strelan, P., Mehaffey, S. J., & Tiggemann, M. (2003). Self-objectification and esteem in young women: The mediating role of reasons for exercise. Sex Roles, 48(1-2), 89–95. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022300930307

- Sun, Q. (2021). Selfie editing and consideration of cosmetic surgery among young Chinese women: The role of self-objectification and facial dissatisfaction. Sex Roles, 84(11-12), 670–679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-020-01191-5

- Taylor, S. E., & Lobel, M. (1989). Social comparison activity under threat: Downward evaluation and upward contacts. Psychological Review, 96(4), 569–575. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.96.4.569

- Tiggemann, M., & Anderberg, I. (2020). Social media is not real: The effect of ‘Instagram vs reality’ images on women’s social comparison and body image. New Media & Society, 22(12), 2183–2199. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444819888720

- Tiggemann, M., & Velissaris, V. G. (2020). The effect of viewing challenging “reality check” Instagram comments on women’s body image. Body Image, 33, 257–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2020.04.004

- Wen, N., Chia, S. C., & Xiaoming, H. (2017). Does gender matter? Testing the influence of presumed media influence on young people’s attitudes toward cosmetic surgery. Sex Roles, 76(7-8), 436–447. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-016-0680-4

- White, J., & Halliwell, E. (2010). Examination of a sociocultural model of excessive exercise among male and female adolescents. Body Image, 7(3), 227–233. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2010.02.002

- Yu, U.-J. (2014). Deconstructing college students’ perceptions of thin-idealized versus nonidealized media images on body dissatisfaction and advertising effectiveness. Clothing and Textiles Research Journal, 32(3), 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X14525850

- Zhang, J., Wang, Y., Li, Q., & Wu, C. (2021). The relationship between SNS usage and disordered eating behaviors: A meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 641919. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.641919