ABSTRACT

The ownership of sex dolls has become an increasingly controversial social issue over the last five to ten years, with many in society (and academia) calling for the criminalization of such dolls. At the root of these calls is the implicit (and often explicit) assumption that sex doll ownership contributes to increases in negative social attitudes toward women, and sexual offense risk among doll owners. However, there are yet to be any empirical examinations of these claims. In this work we compared the psychological characteristics and comparative sexual aggression proclivities of sex doll owners (n = 158) and a non-owner comparison group (n = 135). We found no substantive differences in most psychological traits. Doll owners scored lower than comparators in relation to sexual aggression proclivity. They were, however, more likely to see women as unknowable, the world as dangerous, and have lower sexual self-esteem. They also had more obsessive and emotionally stable personality styles. We conclude that there is no evidence that sex doll owners pose a greater sexual risk than a non-owning comparison group, before highlighting the need for more evidence-informed social debates about the use of sex dolls in modern society.

The ownership of realistic silicone dolls for sexual purposes (‘sex dolls’) is a controversial topic that is gaining an increasing amount of public and academic attention. According to some reports, the global market for sex dolls is a multi-million dollar industry (Valverde, Citation2012). Dolls are typically realistic and can be made as a true likeness of real models, with adult film stars already seeing this as an additional business opportunity (Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018). While the ownership and use of toys and non-human objects for the purposes of sexual gratification is not new, the vast majority of research to date has focused on women’s uses and experiences of toys in masturbation and sexuality exploration (Döring & Pöschl, Citation2018; Fahs & Swank, Citation2013; Lieberman, Citation2017). In this paper, we present the first analysis of the personality, sexual interest, and risk-related characteristics of sex doll owners. In doing so, we have two primary aims:

To identify some of the potential psychological factors that may distinguish sex doll owners from a comparison group of non-owners.

To empirically test the theoretical and social assumption that sex doll ownership is a risk factor for sexual aggression.

We feel the need to stress from the outset that our aim in this paper is not to advocate for any particular argument for doll legalization or criminalization. Instead, we hope our exploratory analyses will inform further longitudinal and experimental work in this area, such that future policy proposals and legislative developments are based on empirical evidence rather than moral positioning. Ultimately, our hope is that this work begins to move both academic and social discussions about sex doll ownership in a more evidence-based direction.

Why Might People Want to Own Sex Dolls?

When referring to ‘sex dolls,’ we are principally concerned with realistic (but inanimate) silicone dolls, or models made from synthetic materials such as thermoplastic elastomer, which mimic the feel and motion of the human body to produce realistic sexual experiences for owners. However, we realize that for some people a ‘sex doll’ may conjure images of unrealistic inflatable items at one end of the realism spectrum, through to interactive sexualized robots with embedded artificial intelligence and the ability to learn at the other. The emergence of realistic dolls, however, has led to an explosion of philosophizing about the ethics of such materials (Carvalho Nascimento et al., Citation2018; Danaher et al., Citation2017; Eskens, Citation2017; Facchin et al., Citation2017; Kubes, Citation2019; Lancaster, Citation2021; Richardson, Citation2019), particularly when these dolls ostensibly represent children (Chatterjee, Citation2020; Cox-George & Bewley, Citation2018; Danaher, Citation2017a, Citation2019b; Maras & Shapiro, Citation2017; Strikwerda, Citation2017). Indeed, there have been some convictions for the importation of sex dolls that resemble children (Brown & Shelling, Citation2019; Danaher, Citation2017a, Citation2019b; Strikwerda, Citation2017), with those prosecuted for such offenses also commonly being found to possess child sexual exploitation material (Brown & Shelling, Citation2019; Cox-George & Bewley, Citation2018). In spite of the rapid increase in theorizing about the ethics of doll ownership, there has been no empirical exploration of the characteristics of individuals who own sex dolls (Harper & Lievesley, Citation2020).

The limited evidence that is currently available suggests that motivations for sex doll ownership are overwhelmingly sexual. In small-scale surveys of owners, up to 70% of participants suggest that sexual gratification is the primary purpose of a doll (Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018; Valverde, Citation2012). However, it has been suggested that sex is just one of a number of reasons for doll ownership among this subgroup (Ferguson, Citation2014; Valverde, Citation2012). Even discounting this non-exclusivity of motivations, these statistics indicate that approximately one-in-three doll owners have a doll for primarily nonsexual reasons. Common alternatives are often linked to relationships, such as interpersonal connection and emotional intimacy (Ferguson, Citation2014; Su et al., Citation2019; Valverde, Citation2012), while others own dolls purely for artistic pursuits (e.g., photography; Su et al., Citation2019). This all being said, there is currently a lack of empirically derived knowledge about who sex doll owners are, or how they present from a psychological perspective. As such, a principal aim of our work was to provide some baseline data about the kinds of psychological factors which may differentiate those who own sex dolls from those who do not.

Sex Dolls as a Precursor to Sexual Risk?

As summarized in recent reviews, there is a wealth of philosophical theorizing about the potential for sex doll ownership to indicate an increased risk of sexual aggression, but very little in the way of empirical data to support or refute this (Harper & Lievesley, Citation2020). In light of the lack of data in this area, there remains the possibility that doll ownership could be risk-enhancing, risk-reducing, or risk-neutral, depending upon the philosophical or theoretical positions adopted by individual writers or research teams. We endeavor to outline these possible positions below.

Model one: Dolls as protective. The first potential model of the effects of sex doll ownership is one of dolls being a protective factor for sexual aggression, in that doll ownership could reduce the incidence of sexual aggression among those who have a proclivity toward this form of offending behavior. Theoretical support for this premise hinges on the role of catharsis. That is, it could be that those with a propensity toward sexual aggression reduce their risk by engaging with a sex doll instead of living people. Although this possibility has not ever been explored empirically among sex doll owners, there is a relatively large and consistent literature supporting this view in relation to mainstream pornography (for reviews, see Ferguson & Hartley, Citation2009, Citation2022).

The use of explicit materials (pornography in the traditional sense, and dolls within the current context) may operate as a form of safe sexual outlet in that these stimuli allow for the seeking out of sexual stimuli and the expression of sexual interests that, on their face, might be offense-supportive, but without the need for a living partner and/or victim (Fisher & Barak, Citation2001). For many individuals there is safety in the expression of sexual interests – even those which are associated with sexual offending – via pornography. For example, Williams et al. (Citation2009) found that a hypothesized link between both sexual fantasy pornography use with sexually deviant behavior was only present among individuals scoring highly on an index of psychopathy, suggesting that those with lower levels of this personality trait might be safe to engage in fantasizing and pornography consumption. Similarly, a series of meta-analytic reviews found an inverse relationship between societal levels of sexually explicit materials and levels of sexual aggression (Ferguson & Hartley, Citation2009, Citation2022; Fisher & Barak, Citation2001). That is, as rates of pornography consumption have risen in many western societies, rates of sexual violence have fallen. Although causation cannot be inferred from correlational data at the societal level, this suggests that there is, as a minimum, no direct effect of consuming sexually explicit material on rates of sexual violence at the societal level. To go further, Ferguson and Hartley (Citation2022) have suggested that individual studies that find cross-sectional data in favor of an argument supporting adverse effects of pornography consumption are theoretically or methodologically flawed, and/or suffer from citation biases. Similar trends have been found in relation to child sexual exploitation material, whereby a clear and direct link between consuming sexually explicit materials depicting children and engaging in sexual offending has not been reported (Diamond et al., Citation2011; Seto & Eke, Citation2005; Seto et al., Citation2011).

Applying this literature to the sex doll context, it is plausible that individuals who own dolls have atypical sexual interest patterns, or paraphilic fantasies that they may struggle to enact with other (consenting) individuals. As such, they might purchase dolls (alongside other forms of sexual or masturbatory aid) to help them to achieve sexual satisfaction and reduce the risk of them acting on such paraphilic interests in coercive ways.

Model two: Dolls as risky. On the opposite end of the risk spectrum, a common theme within the existing literature on sex doll ownership focuses on the effects that the commercial availability of realistic sex dolls has on broad-scale social attitudes toward women (Carvalho Nascimento et al., Citation2018; Cassidy, Citation2016; Danaher, Citation2017a, Citation2017b, Citation2019a; Kubes, Citation2019; Puig, Citation2017; Richardson, Citation2019; Shokri & Asl, Citation2015). Such claims relate to the process by which sex dolls reinforce the objectification of women, and bolsters a culturally-constructed sexual beauty standard (Cassidy, Citation2016; Ciambrone et al., Citation2017; Danaher, Citation2017b; Puig, Citation2017; Ray, Citation2016; Richardson, Citation2019). This was the basis for the claim that we should abandon the “unsophisticated” porn star design of sex dolls and robots, and to instead create “robots that are more realistic in their representations (both physical and behavioral) of women” (Danaher, Citation2019a, p. 142). However, the physical features of popular sex doll models (e.g., larger breasts, combined with a waist-to-hip ratio of approximately 0.70; Kock et al., Citation2008; Valverde, Citation2012) correspond to evolutionary cues that men find sexually attractive across a range of cultures and measurement approaches (Brooks et al., Citation2010; Buss, Citation2021; Del Zotto & Pegna, Citation2017; Dixson et al., Citation2011; Griffith et al., Citation2016; Saad, Citation2008, Citation2017; Singh et al., Citation2010).

Irrespective of the origins of perceptions of female sexual attractiveness (evolution or social construction), there is a wealth of evidence that viewing women as sexual objects is associated with sexual aggression. For instance, this has been identified as one of five implicit theories that underpin thought patterns and post-offense justifications among individuals with sexual convictions (Polaschek & Gannon, Citation2004; Polaschek & Ward, Citation2002; for reviews of offense-supportive cognition, see Helmus et al., Citation2013; Szumski et al., Citation2018). Other implicit theories include sexual entitlement (viewing sexual access as a right), viewing the male sex drive as uncontrollable (i.e., arousal inevitably needing to lead to orgasm), judging women as unknowable (i.e., the view that women are manipulative or dangerous to men), and viewing the world as a generally dangerous, threatening, or hostile place. It might also be that the on-demand nature of sex with dolls increases a sense of sexual entitlement, with a subsequent effect being an increase in the view that male sexual arousal should always result in orgasm, enhancing the presence of the aforementioned implicit theories among sex doll owners. Sexual entitlement is also linked to a preference for sadistic and/or coercive sex, which is also referred to as biastophilia in sexuality research (Richardson et al., Citation2017; Seto et al., Citation2012). Recent work has also found an association between biastophilic fantasizing and a proclivity for engaging in sexual activity with submissive (i.e., sleeping) partners (Deehan & Bartels, Citation2021), for which sex dolls could act as a surrogate. As a collective of findings, a network of relationships thus begins to develop that might suggest a self-fulfilling cycle of implicit theories supportive of rape, preferences for coercive sex, and a proclivity for passive sexual partners which, at least theoretically, could apply to sex doll ownership.

Implicit theories are considered under the umbrella of offense-supportive attitudes and cognitions, with such beliefs being empirically established as meaningful predictors of recidivism among those convicted of sexual offenses (Brankley et al., Citation2021; Mann et al., Citation2010). In community settings, sexual objectification has been associated with higher levels of rape myth acceptance (Samji & Vasquez, Citation2020), lenient attitudes about rape (Bernard et al., Citation2015), and a proclivity toward violence toward women (Vasquez et al., Citation2018). Relatedly, having a lifelike doll on-hand for sexual activity and gratification can plausibly be linked to (or said to serve) a sense of sexual entitlement, which in turn is predictive of recidivism (Brankley et al., Citation2021; Pemberton & Wakeling, Citation2009). With these past empirical data in mind, it is important to explore whether moralistic claims about sex doll ownership are borne out in responses provided by this population to test the validity of broad-scale policy recommendations related to doll bans and criminalization. Here we do not use ‘moralistic’ in a pejorative sense, but rather use this to highlight the non-empirical and rhetorical nature of publications emerging from legal and sociological spheres in relation to sex doll owners. In doing so, we wish to highlight that these publications typically contain no data but rely on a form of legal argumentation that sets out a potential for sexual aggression stemming from sex doll ownership. Nonetheless, the framework for exploring whether doll ownership contributes to negative attitudes toward women, sexualization, and thus increased propensities for sexual aggression is theoretically plausible and deserving of empirical evaluation.

Model three: Dolls as functional, motivations as interactive. Although not widely studied, there are a range of non-coercive paraphilias that are seemingly neither risk-enhancing nor risk-reducing, but are simply related to the function of sexual (or related) gratification. The etiological origins of such paraphilias are debated, but recent commentaries have appeared to favor conditioning-based accounts. That is, sexual interests in non-human objects can emerge through their pairing with normatively sexually arousing stimuli (for a review, see Pfaus et al., Citation2020; for a contradictory view, see Hsu & Bailey, Citation2020). Our concern here is not to engage, per se, with the academic debate about whether paraphilias are conditioned or not, but rather to highlight that some individuals are interested in engaging with ostensibly nonsexual objects for sexual gratification.

Early exposure to media, particularly pornography, might set a template for the types of bodies, objects, and activities an individual finds sexually exciting, with such templates acting as an implicit guide in partnered sexual activity (Bridges et al., Citation2016; Riemersma & Sytsma, Citation2013). Where partners are able (or willing) to live out paraphilic fantasies, there exists no discordance, meaning that individuals can appear to have normative relationship experiences even in the presence of paraphilic sexual interests. However, when partners are unable (or unwilling) to indulge paraphilic fantasies, discordance may arise, leading to relationship dissatisfaction and dissolution. It is in this theoretical place that we might see some application to the ownership of sex dolls that is unrelated to sexual risk, and more related to sexual and romantic gratification. That is, given that sex dolls typically embody a ‘porn star’ female appearance (Danaher, Citation2019a), and doll owners report both sexual and nonsexual reasons (Ferguson, Citation2014; Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018; Su et al., Citation2019; Valverde, Citation2012), it could be that those who own dolls are seeking a surrogate relationship that they are craving, but cannot achieve due to unrealistic expectations or a lack of relational ability. Within this model we might expect doll owners to have a series of unsuccessful relationships in their histories, or perhaps specific sexual interests that could be off-putting to potential intimate partners.

Linked to this are potentially functional emotional effects of doll ownership. As noted by other authors, some individuals who own sex dolls suggest that they do so in order to achieve a sense of interpersonal connection and emotional intimacy (Ferguson, Citation2014; Su et al., Citation2019; Valverde, Citation2012). If we accept the premise that this might be related to a lack of successful relationships in the past, it may be that such individuals (typically men) come to see living potential partners (typically women) as unknowable, and thus unsuitable for opening up to and forging close connections with. Viewing women as unknowable (an implicit theory related to rape proclivity; Beech et al., Citation2013) might lead to a retreat from the standard mating market, and contribute to the development of insecure attachment patterns that are prevalent in men who have poor quality relationships (Molero et al., Citation2016; Péloquin et al., Citation2014), or engage in frequent pornography use (Szymanski & Stewart-Richardson, Citation2014). There is also a rich literature on men using sex as a coping strategy for low indices of mental wellbeing or emotional stability (Berdychevsky et al., Citation2013; Gillespie et al., Citation2021; for a review in the forensic context, see Gunst et al., Citation2017). This opens up the possibility that sex doll ownership is not necessarily an exclusively sexual phenomenon, though it clearly possesses some sexual elements. Instead, dolls may become functional surrogates for living partners, providing owners with a safe outlet for obtaining a form of emotional closeness with a human-like companion, with subsequent effects of increasing positive emotion and mental wellbeing.

A testable model of the link between doll ownership and sexual aggression. The predominant sexual motivation for sex doll ownership (Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018; Ray, Citation2016; Valverde, Citation2012) may be useful in formulating a theoretical model of how doll ownership is linked to sexual aggression, if such a relationship exists. While we do not advocate for or against a link at this stage, it is necessary to formulate a hypothesized path from doll ownership to sexual aggression, which can then either be statistically supported or rejected by data that are obtained using empirical methods. All major multifactorial explanatory models of sexual offending contain some reference to sexual arousal or sexual scripts (Finkelhor, Citation1984; Hall & Hirschman, Citation1991; Marshall & Barbaree, Citation1990; Seto, Citation2019; Ward & Beech, Citation2006; Ward & Siegert, Citation2002), and it may be useful to begin from this position in light of the aforementioned sexual motivations for doll ownership. We also believe that the application of existing frameworks for sexual aggression represents a more defensible way of understanding how currently underexplored phenomena (e.g., sex doll ownership) might be linked to sexual offending, if indeed they are. In the most recent, and perhaps most parsimonious, of these existing frameworks, Seto (Citation2019) suggested that sexual offending occurs as a result of motivational and facilitating factors. In this model, motivators provide an initial impetus or interest in a potentially criminal sexual behavior. The most commonly discussed motivator of sexual offending is pedophilia (Finkelhor, Citation1984; Seto, Citation2019; Ward & Siegert, Citation2002), but having a sexual arousal pattern that involves interests in coercive sex (biastophilia), watching others engaged in sexual activity (voyeurism), or exposing oneself to unsuspecting others (exhibitionism) may also translate into an interest in engaging in their accompanying behaviors (Joyal & Carpentier, Citation2021; Seto et al., Citation2021). However, according to the motivation-facilitation model, these motivating sexual interests will only be translated into action or behavior when accompanied by facilitators. These can be measured at the trait level (e.g., antisociality and psychopathy, or general behavioral disinhibition) or the state level (e.g., temporary intoxication through substances, stress, or depressed mood).

Applying Seto’s (Citation2019) model to the sex doll context, it may be that any main effect (either a significant effect, or a null effect) of owning a sex doll on indices of sexual aggression is potentially moderated by other psychological factors. That is, it may be that sex doll ownership is associated with an increased proclivity for sexual aggression (a significant direct effect), but that this effect is not present among doll owners with low levels of psychopathy, or more positive or egalitarian attitudes toward women (as examples of potential moderators). In contrast, it may equally be the case that sex doll ownership is not linked to sexual aggression proclivity when considered in isolation (a null direct effect) but becomes significant among doll owners with higher levels of offense-supportive cognition (e.g., sexual entitlement). It is this type of question that we sought to answer in the current study. In doing so, we do not suggest that sexual offending is inevitable among doll owners. Indeed, there is an alternative school of thought that doll ownership for sexual motivations might be cathartic, offering a safe sexual outlet to those with potentially atypical or offense-related paraphilias (for a brief presentation of this argument about a potential cathartic effect in relation to pornography use, see Fisher et al., Citation2013). However, we are testing the moralistically-expressed assumption that doll ownership could be associated with a proclivity for sexual aggression (Danaher, Citation2017b; Eskens, Citation2017; Puig, Citation2017; Richardson, Citation2019), and whether any such relationship is enhanced or mitigated by other moderating variables.

The aim of the current study was to explore the psychological characteristics of sex doll owners, both in comparison to a sample who do not own dolls, and in relation to any risk that they may pose in terms of sexual aggression. To our knowledge, this is the first such project examining these themes in an empirical manner. As such, we ran exploratory analyses to test for differences between sex doll owners and non-owners on constructs that have been identified as potentially important in previous theorizing (Cassidy, Citation2016; Danaher, Citation2017b; Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018; Puig, Citation2017; Shokri & Asl, Citation2015; Su et al., Citation2019; Valverde, Citation2012). Constructs that we specifically measured were sexual aggression proclivity, offense-supportive cognitions (i.e., implicit theories supportive of rape), aggressive paraphilias, disordered personality styles, attachment styles, and sexual self-esteem. Irrespective of outcomes of these tests of between-groups differences, we also tested the moderating effects of potential constructs that facilitate sexual aggression (in line with Seto, Citation2019).

In light of the exploratory nature of this project, and the lack of existing research with sex doll owners, we made no specific hypotheses at the outset of the study. Similarly, we did not make any adjustments to our stated alpha in our analysis (i.e., we retained the standard p < .05 threshold as a potential indicator for statistical significance). This is because our tests represent tests of different questions (e.g., “do doll owners and a comparison group differ in relation to their levels of X?” or “to what extent does X predict sex doll ownership?”). From a philosophical perspective these represent different tests, with Rubin (Citation2017) suggesting that exploratory research of this kind does not require adjustments to alpha in such cases. We return to this issue in the Discussion of the paper. However, in line with moves to improve the replicability of psychological research, we did not exclusively rely on p-values to indicate meaningful differences and relationships (Cumming, Citation2014), and urge readers to focus more on effect sizes than on arbitrary p-value thresholds as a basis for thinking through the psychology of sex doll ownership, and when planning subsequent confirmatory research.

Method

Participants

We first sampled sex doll owners in order to make sure that our comparison group was of an approximately equal size. This group was invited to take part through advertisements placed on prominent online discussion forumsFootnote1 for doll owners and individuals with niche/fetishized sexual interests. Advertisements stated the aims of the survey, which were framed as a direct examination of the accuracy of social beliefs and perceptions about sex doll ownership. Our only exclusion criteria were an age of less than 18 years and a lack of fluency in English. In the initial round of recruitment (January 2019 to November 2020), 270 people clicked on the survey link, of which five did not disclose whether or not they owned a sex doll. Examining doll ownership status, 22 individuals suggested that they exclusively owned child-like sex dolls. Owing to this small subsample size and anticipating a lack of power in planned analyses, we did not include these participants in any analyses, and instead focused only on owners with adult-like dolls. This also meant that we excluded 11 participants who self-declared exclusive sexual interest in children (operationalized as declaring no adult attraction, or an age of attraction which did not span above 18 years). However, we did retain participants who suggested that they owned both child-like and adult-like dolls (n = 21) due to them owning at least one adult-like doll.Footnote2 We also excluded the small number of women who completed the survey (n = 20) due to the gendered nature of sex doll ownership, the claims made in previous theorizing about doll owners, and the subsequent framing of our measures. We then explored the qualitative responses to the free text boxes contained within the survey and excluded one person for apparent insincere responding (i.e., declaring ownership of 300 dolls for the function of “food”). A further 32 participants did not provide any sexual aggression proclivity data (our key outcome variable, see below) and were subsequently excluded from the dataset.

We then set a target of recruiting a comparison sample of 150 participants who did not own a sex doll via the crowdsourcing platform Prolific. These participants responded to a survey task exploring psychological predictors of sexuality and sexual behavior. Although doll owners were not compensated for their time, participants in the control sample received £2.40 (approximately $3 at the time of data collection) in line with website reimbursement guidelines. Complete responses were obtained from everybody who took part via Prolific (n = 135). No exclusions were necessary. This data collection took place in February 2021.

As such, the analyses that follow are based on a final sample of 293 male participants. Of these, 158 were sex doll owners (Mage = 38.00 years, SD = 12.47) and 135 were non-owners (Mage = 34.23 years, SD = 12.70).

Measures

Demographics

We asked participants to provide information about their sex, age, educational level (years completed), sexual orientation, and relationship status. Demographic information for each sample is presented in .

Table 1. Participant demographics by group.

Doll Ownership Questions

Aside from asking about doll owning status (yes/no), we asked about how many dolls owners had. We also enquired about the function of participants’ doll ownership by asking participants to rate sexual reasons (e.g., sexual gratification), emotional reasons (e.g., a surrogate relationship or companionship), and other reasons (for which participants were asked to specify their motivations) using a 1–10 scale (high scores indicating greater motivations on each respective index). That is, we were able to explore whether a greater relative emphasis was placed on sexual, emotional, or other motivations for doll ownership using these single-item measures. We also asked participants how many times (on average) they engage in sexual activity with their doll(s). If participants suggested that they did not own a sex doll, we asked about their level of interest in doing so using a binary yes/no forced choice.

Sexual Aggression Proclivity

We used an adapted version of Bohner et al.’s (Citation1998) rape proclivity measure to tap into a construct of sexual aggression proclivity. In the original measure, five rape scenarios are presented to participants, who are asked to place themselves in the position of the perpetrator. After reading each scenario, participants are asked to rate how aroused they would be, whether they would behave in the same way, and how enjoyable the situation would be using seven-point scales (where high scores indicate greater levels of arousal, enjoyment, and behavioral propensity). We adapted this measure by writing scenarios that not only depict rape, but also non-penetrative forms of sexual assault and sexual harassment. Full wording of the scenarios is available at https://osf.io/7nsuh/. We computed an average score across all 15 responses on this measure to calculate a composite score for sexual aggression proclivity (possible average score range = 1–7, with higher scores indicating greater proclivities for sexual aggression; doll owners α = 0.94; comparison α = 0.89).

Sexual Fantasies

In addition to sexual aggression proclivity, we also wanted to measure paraphilic sexual fantasies that may be associated with such aggression. To do this we used the paraphilia questionnaire created by Seto et al. (Citation2012), using only the items related to biastophilia (two items; e.g., “You are forcing someone into sexual activity”; doll owners α = 0.84; comparison α = 0.85) and sadism (six items; e.g., “You are controlling or dominating someone”; doll owners α = 0.85; comparison α = 0.87) in our analyses. No contextual information (e.g., related to sexual consent, or a lack thereof) was provided for each item, in line with the scale’s original composition. Each item was rated using a seven-point scale, anchored from “very repulsive” to “very arousing” (scored from −3 to +3). Average scores were computed for each fantasy domain, with high scores indicating a greater presence of biastophilic and sadistic sexual fantasies, respectively.

Offense-Supportive Cognition

In line with Seto’s (Citation2019) motivation-facilitation model, it may be that any potential relationship between doll ownership and sexual aggression is moderated by other facilitating factors. Theories of sexual offending cite offense-supportive cognitions in the form of implicit theories as being potential candidates for these facilitators. To measure these, we used Butler and Bartels’ (Citation2018) implicit theory measure, which was developed to examine respondents’ endorsement of the implicit theory domains established in previous work (Polaschek & Gannon, Citation2004; Polaschek & Ward, Citation2002). That is, seven items for each of the five implicit theories were rated using a five-point scale, anchored from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (scored 1–5). An average score was calculated for each implicit theory domain:

Women as sex objects (e.g., “If a woman wears revealing clothes, she is trying to arouse men”; doll owners α = 0.82; comparison α = 0.79)

Sexual entitlement (e.g., “I am free to do what I like with a woman in the bedroom”; doll owners α = 0.51; comparison α = 0.48)

Dangerous world (e.g., “People are so unpredictable and untrustworthy”; doll owners α = 0.84; comparison α = 0.82)

Women as unknowable (e.g., “Most women cannot be trusted”; doll owners α = 0.84; comparison α = 0.83)

Uncontrollability of the male sex drive (e.g., “The male sex drive can turn a good man bad”; doll owners α = 0.88; comparison α = 0.87)

Personality Styles Inventory

We used Hain et al.’s (Citation2016) Personality Styles Inventory to measure traits that are associated with disordered personality traits. This is a 36-item scale within which each item is rated using a four-point scale, ranging from “does not apply at all” to “fully applies” (scored 1–4). An average score was calculated for each personality style. The personality styles that were measured were:

Schizotypal (e.g., “I often have sudden inspirations”; α = 0.75; comparison α = 0.79)

Borderline (e.g., “My feelings often change abruptly and impulsively”; α = 0.77; comparison α = 0.87)

Narcissistic (e.g., “Being the center of attention really appeals to me”; α = 0.67; comparison α = 0.64)

Avoidant (e.g., “Criticism hurts me quicker than it does others”; α = 0.66; comparison α = 0.62)

Obsessive-compulsive (e.g., “Even under time pressure, I cannot stop being thorough”; α = 0.64; comparison α = 0.74)

Antisocial (e.g., “I prefer to attack, rather than letting others attack me”; α = 0.80; comparison α = 0.84)

Emotional Functioning

We also asked participants to respond to the 20-item Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS; Watson et al., Citation1988). This measure contains a list of emotions and asks participants to state how often they have experienced each of these within the past seven days. There were ten positive items (e.g., excited, strong, proud; doll owners α = 0.87; comparison α = 0.89) and ten negative items (e.g., upset, guilty, ashamed; doll owners α = 0.84; comparison α = 0.88). Each item was rated using a seven-point scale ranging from “very slightly or not at all” to “extremely” (scored 1–7). An average score was calculated separately for positive and negative feelings, with higher scores indicating a greater presence of each. After computing these values, we subtracted the negative affect score from the positive affect score to produce a composite ‘affect’ variable, where positive scores equated to more positive affect, and a negative score equated to more negative affect. It is this composite score that we included in our analyses.

We also measured sexual self-esteem using this subscale of Snell and Papini’s (Citation1989) measure of sexuality. This subscale is comprised of ten items (e.g., “I am a good sexual partner”; doll owners α = .95; comparison α = 0.91) scored using a five-point scale anchored from “disagree” to “agree” (scored 1–5). An average score was computed, with higher values indicating greater levels of sexual self-esteem.

Attachment Styles

The State Adult Attachment Measure (Gillath et al., Citation2009) was used to examine attachment styles. This is a 21-item scale that measures the extent to which respondents exhibit traits associated with a secure attachment style (e.g., “I feel like I have someone to rely on”; doll owners α = 0.91; comparison α = 0.92), an insecure-anxious attachment style (e.g., “I wish someone would tell me they really love me”; doll owners α = 0.85; comparison α = 0.87), and an insecure-avoidant attachment style (e.g., “The idea of being emotionally close to someone makes me nervous”; doll owners α = 0.83; comparison α = 0.83). There were seven items per attachment style, which were each rated using a seven-point scale anchored from “disagree strongly” to “agree strongly” (scored 1–7). An average score for each attachment style was computed, with higher scores indicating a greater presence of each style.

Unreported Measures

In an earlier iteration of this work, we reported our analyses with some additional variables. These were psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and narcissism (as measured using the Short Dark Triad Scale; Jones & Paulhus, Citation2014), hostility toward women (as measured using the Hostility Toward Women scale; Lonsway & Fitzgerald, Citation1995), the sexual objectification of women (as measured using the Interpersonal Sexual Objectification Scale – Perpetrator Version; Gervais et al., Citation2018), and propensities for emotional reappraisal and emotional suppression (as measured using the Emotional Regulation Questionnaire; Gross & John, Citation2003). During the peer review process, concerns were raised about the number of variables that were measured and used in our analysis. We chose to remove these variables from the paper to address these concerns, owing to their overlap with other scales. For example, ‘dark triad’ traits were covered in the Personality Styles Questionnaire (particularly in relation to narcissism and antisociality), hostility toward women and sexual objectification were covered in the offense-supportive cognition measure, and emotional functioning was covered in relation to attachment and general affective experiences. We also removed sadistic fantasizing from our statistical models owing to its conceptual similarity to biastophilia (which we retained as a fantasy version of sexual aggression proclivity). The removal of these specific measures did not substantively impact the results reported in either versions of this work.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using the aforementioned advertising routes. Those who were interested in taking part in the survey clicked on the link, which presented the information sheet for the study. Participants then affirmed their consent, before providing demographic information and answering questions about their doll ownership. Based on their response to the “age” of their doll, owners then received either the sexual aggression proclivity scale (for owners of adult-like dolls), an interest in child molestation scale (for owners of child-like dolls), or both proclivity measures (for owners of both types of dolls).Footnote3 Following this, all other questionnaires were presented in a random order. The debrief information contained all information about the measures used in the study and provided links to help and support for people experiencing emotional wellbeing issues, or troubling thoughts about their sexuality and sexual interests. The average completion time for the survey was 25 minutes.

This procedure was approved by the Nottingham Trent University School of Social Sciences Research Ethics Committee prior to data collection and followed the guidelines of the British Psychological Society code of ethics.

Results

We retained all previously reported participants, irrespective of the extent to which they completed the entirety of the survey.Footnote4 To maintain clarity in the paper, the sample sizes for all completed measures, broken down by group, are provided in the statistical output files at https://osf.io/7nsuh/.

We present our results in three sections. First, we compared the two groups (sex doll owners vs. non-owners) on all measured variables. This initial comparison allowed us to explore whether doll owners were statistically different to non-owners on each of these variables, as might be suggested via past academic and popular discourses. Second, we present a binary logistic regression aimed at predicting group membership. That is, while controlling for the other measured variables we sought to understand whether there were particular constructs that might distinguish doll owners from the comparison group. Finally, in response to the extant theoretical literature on doll ownership and sexual aggression risk we offer results from a series of moderation analyses that explored the application of Seto’s (Citation2019) motivation-facilitation model within the context of sex doll ownership’s suggested relationship to sexual offending.

Between-Groups Analyses

To establish whether any differences existed between sex doll owners and a non-owning comparison group, we ran a series of 18 independent-groups t-tests to compare the scores of each group on each of our measured variables. We chose to conduct a series of t-tests in order to maintain the independence of each variable under investigation, rather than aggregating and weighting them within a multivariate analysis of variance (MANOVA; for a discussion, see Huang, Citation2020). Descriptive and inferential statistics can be found in . We used Lovakov and Agadullina’s (Citation2021) guidance for determining the magnitude of effect sizes in line with norms in psychological science:

Small effects: d = ±0.15

Moderate effects: d = ±0.36

Large effects: d = ±0.65

Table 2. Average scores on measured variables, by doll ownership group.

Using these benchmarks, we determined a “smallest effect size of interest” (SESOI) of d = 0.26 using the mid-point of the small-to-moderate range. We did this so as to not be subject to the arbitrary nature of the p < .05 threshold for statistical significance, while also not classifying particularly small effects as definitively meaningful.

Demographic Differences

We began by looking at demographic differences between sex doll owners and those in the comparison group. Descriptive statistics can be found in . On average, doll owners were moderately older than non-owners, t(290) = 2.55, p = .011, d = 0.30. They were also moderately less likely to have partnered sexual activity on a monthly basis, t(231) = −2.33, p = .020, d = −0.31. However, this lower level of partnered sex might be attributable to doll owners being substantially less likely to be in relationships (i.e., having lower rates of current marriage or intimate partner, and higher rates of separation and divorce), χ2 (5) = 58.50, p < .001, Cramer’s V = 0.45. There was no difference in educational level between the two groups, t(279) = 0.59, p = .554, d = 0.07. A small difference existed in the prevalence of non-heterosexuality between the two groups, with non-owner comparators being slightly more likely to express homosexual (i.e., androphilic) sexual attractions than doll owners, χ2 (2) = 12.60, p = .002, Cramer’s V = 0.21

Psychological Differences

As demonstrated in , there were very few differences between the two groups. Doll owners were no more or less prone to sexual aggression proclivity, fantasizing about coercive sex, or to having issues with emotion and attachment than those in the comparison group. We did see some important differences, though. Sex doll owners were significantly more likely to see women as sex objects, to report greater sexual entitlement, and to see women as unknowable than non-owners. Doll owners also self-reported lower levels of borderline personality traits than non-owners. In each of these cases the magnitude of the difference between the groups was above our SESOI threshold.

Predicting Group Membership

To identify predictors of sex doll ownership, we ran a binary logistic regression with 20 predictors. We entered all measured variables as predictors and used the binary “sex doll owner” variable as the dependent variable. Predictors were entered as continuous scores in this analysis. In general, all variables were normally distributed with some notable exceptions in relation to sexual aggression proclivity and biastophilia (the distribution histograms are available on the project’s OSF page at https://osf.io/7nsuh/). We used all measured variables in the model (rather than only those meeting our SESOI in the between-groups analyses above) to explore whether different predictors of doll ownership emerged when controlling for other variables.

The regression model was statistically significant, χ2(20) = 61.10, p < .001, Nagelkerke’s pseudo R2 = 0.32. Model coefficients are presented in . The model correctly classified 73.3% of participants into either the “doll owner” or “comparison” groups and was more successful when classifying participants in the comparison group (79.2%) than sex doll owners (66.3%). In addition to the standard p < .05 threshold for statistical significance for identifying potentially discriminating variables, we used Sánchez-Meca et al.’s (Citation2003) calculation for determining the magnitude of odds ratios (using the aforementioned psychological norms of Cohen’s d as a guide; Lovakov & Agadullina, Citation2021), leading to the following guidelines for negative and positive associations, respectively:

Small effects: OR < 0.76 or OR > 1.31

Moderate effects: OR < 0.52 or OR > 1.92

Large effects: OR < 0.31 or OR > 3.25

Table 3. Binary logistic regression predicting sex doll ownership categorization.

Using the SESOI justification previously mentioned, we determined an effect to be potentially meaningful if the OR was either less than 0.62 (associated with not owning a doll), or more than 1.60 (associated with owning a doll). These thresholds were determined via an online effect size converter (https://escal.site) and using d = 0.26 as the SESOI.

Within this model there were relatively few predictors of doll ownership status at the coefficient level. However, those variables that did seem to distinguish between owners and non-owners seem to paint the picture of an emerging profile of doll ownership. That is, doll ownership was predicted by lower levels of a behavioral proclivity for sexual aggression (OR = 0.52, p = .012) that may be indicative of doll ownership having a cathartic effect on coercive sexual fantasies when they are present (importantly, biastophilic fantasies did not predict doll ownership, though the relationship was inverse to that of sexual aggression proclivity). From a relational perspective, viewing women as unknowable (OR = 1.79, p = .053) and having lower levels of sexual self-esteem (OR = 0.60, p = .012) were meaningfully associated with, though not always statistically significantly, being a doll owner. This potentially suggests that dolls can act as a safe surrogate for relationships with living people due to doll owners’ concerns about their own sexual performance, or a lack of understanding of the opposite sex. Such safety might be maintained by using a doll to maintain order within a relationship, with doll owners scoring higher on obsessive-compulsive traits than those in the comparison group (OR = 2.14, p = .027). This might also explain the perception that women are unknowable, particularly if their needs are viewed as being in competition with those of doll owners. Evidence for dolls potentially contributing to a sense of safety is provided in the possible relationship between lower propensities for seeing the world as dangerous among the doll owner sample (OR = 0.53, p = .052). We mention some of these associations as their effect sizes suggest a psychologically meaningful (being small-to-moderate in relative magnitude) despite them not meeting the arbitrary p < .05 threshold for statistical significance in the current sample. From an emotional perspective, doll owners were less likely to express borderline personality traits than participants who did not own a doll (OR = 0.34, p < .001), suggesting that their emotional condition is more stable than non-owners.

Potential Moderators of Sexual Aggression Proclivity

As a direct test of the applicability of Seto’s (Citation2019) motivation-facilitation model, we ran a series of exploratory moderated regression analyses. These were conducted using Hayes (Citation2018) PROCESS macro for SPSS, running Model 1, which tests for a simple moderation of the relationship between a focal predictor (X) on an outcome (Y) by a third variable (W). Here, we tested whether sex doll ownership was associated with sexual aggression proclivity at different levels (−1 SD, M, +1 SD) of each of our measured variables. All predictors were mean-centered within the analyses by the PROCESS macro.

All models were statistically significant, but only two modelsFootnote5 produced a significant interaction between doll ownership status and the moderator. For clarity within this paper, we only report these below, but the output files for all analyses are available at https://osf.io/7nsuh/. The model coefficients for each of the three models with a significant interaction are presented in . As per Hayes’ (Citation2018) instructions, all b-values are unstandardized.

Table 4. Significant interactions for moderated regression analyses.

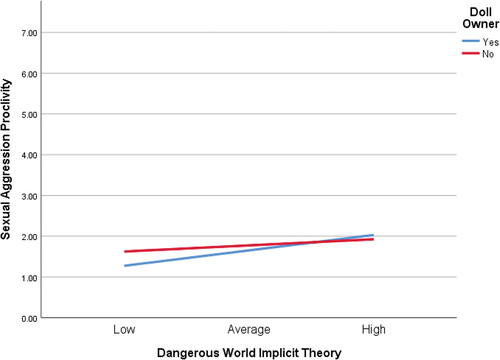

The model that included the dangerous world implicit theory as a moderator was statistically significant and explained approximately 11% of the variance in sexual aggression proclivity, F(3, 242) = 10.07, p < .001, R2 = .111. Within the model, sex doll ownership was not significantly associated with sexual aggression proclivity, b = 0.12 [95% CI: −0.09, 0.34], p = .261. However, holding an implicit theory about the world being dangerous was associated with a greater tendency to self-report a proclivity for sexual aggression, b = 0.33 [95% CI: 0.20, 0.47], p < .001. There was a significant interaction between doll ownership and dangerous world implicit theory endorsement, b = −0.29 [95% CI: −0.57, −0.02], p = .038. This is depicted in .

Figure 1. Associations between sex doll ownership and sexual aggression proclivity, by dangerous world implicit theory level.

Breaking down this interaction, there is a significant effect of sex doll ownership on sexual aggression proclivity at low levels of the dangerous world implicit theory, b = .35 [95% CI: 0.05, 0.65], t(245) = 2.28, p = .024. Here, sex doll ownership was associated with lower levels of sexual aggression proclivity. At mean levels of dangerous world implicit theory endorsement there was no effect of doll ownership on sexual aggression proclivity, b = 0.12 [95% CI: −0.09, 0.34], t(245) = 1.13, p = .261. This was also the case among those endorsing the dangerous world implicit theory to the greatest degree, b = −0.11 [95% CI: −0.41, 0.20], t(245) = −0.68, p = .495.

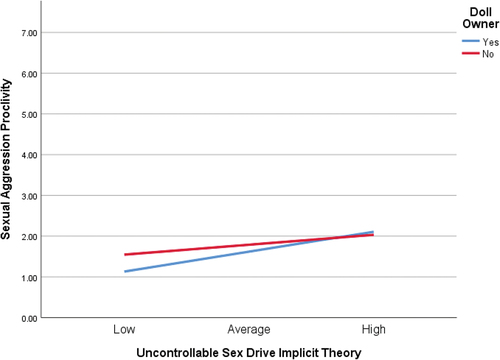

The model that included the uncontrollable sex drive implicit theory as was moderator was statistically significant and explained 20% of the variance in sexual aggression proclivity, F(3, 242) = 20.11, p < .001, R2 = .200. Within this model, sex doll ownership was unrelated to sexual aggression proclivity, b = 0.17 [95% CI: −0.03, 0.37], p = .100. However, endorsing an implicit theory about the male sex drive being uncontrollable was related to enhanced self-reported sexual aggression proclivity, b = 0.41 [95% CI: 0.29, 0.53], p < .001. There was a significant interaction between doll ownership and uncontrollable sex drive implicit theory endorsement, b = −0.28 [95% CI: −0.51, −0.05], p = .019. The interaction is shown in .

Figure 2. Associations between sex doll ownership and sexual aggression proclivity, by uncontrollable sex drive implicit theory level.

At low levels of the uncontrollable sex drive implicit theory there was a significant effect of sex doll ownership on sexual aggression proclivity, b = .42 [95% CI: 0.13, 0.70], t(245) = 2.84, p = .005. Here, sex doll ownership was associated with lower levels of sexual aggression proclivity. At mean levels of seeing the male sex drive as uncontrollable there was no effect of sex doll ownership on sexual aggression proclivity, b = 0.17 [95% CI: −0.03, 0.37], t(245) = 1.65, p = .100. This was also the case among those who scored high in terms of their view about the male sex drive being uncontrollable, b = −0.08 [95% CI: −0.36, 0.21], t(245) = −0.51, p = .611.

Taken together, these results appear to suggest some applicability of the motivation-facilitation model to the sex doll context. However, this application is not necessarily as expected. That is, doll ownership does not appear to be associated with proclivities for sexual offending, nor do doll owners demonstrate a greater proclivity toward sexual aggression than people in our comparison group of non-owners when they score high on indices of known correlates of sexual offending. However, sex doll ownership emerged as a potentially protective factor when owners possessed low levels of various moderating psychological traits, such as implicit theories about the world being dangerous and the male sex drive being uncontrollable. These findings converge with the between-groups comparisons and logistic regression results above to suggest that the ownership of a sex doll does not appear to indicate an increased risk of sexual offending in the current sample.

Discussion

In this work we have presented the first systematic psychological examination of sex doll owners by comparing their psychological characteristics to a comparison sample and exploring any potential links between sex doll ownership and a proclivity for sexual aggression. At the outset of our discussion, we must re-state that our data relate only to male doll owners of adult-like dolls, and as such no inferences should be drawn in relation to female doll owners, or those who exclusively own child-like sex dolls.

Although we found very few differences between doll owners and the comparison sample, a small number of variables did appear to vary between the two groups. Doll owners were older and less likely to be in relationships (particularly following divorce or separation) than non-owners. This relationship status finding is likely an explanation for the lower levels of partnered sexual activity among doll owners than among those in the comparison group. Exploring simple between-groups differences, we found that doll owners scored higher than non-owners on indices of sexual entitlement, viewing women as unknowable, and seeing women as sexual objects. In contrast, they scored lower in relation to borderline (i.e., emotionally unstable) personality traits. It is important to note that in each of these cases, average score differences appear to be negligible (approximately 0.2–0.3 scale points on four- and five-point scales). However, in psychological terms these differences were of a moderate magnitude, and so may be deserving of further exploration.

In spite of these between-groups differences, only a small number of constructs distinguished doll owners from the comparison group when controlling for all other variables. From a personality perspective, doll owners were distinguishable by their higher levels of obsessive-compulsive traits, as well as the aforementioned lower levels of borderline traits. It may be that these trait clusters interact in some functional way, with obsessively controlling one’s environment helping to maintain a sense of emotional stability. A similar interacting relationship might be at play with regard to implicit theories pertaining to viewing women as unknowable and viewing the world as dangerous, particularly in the context of both histories of poor-quality relationships (observed through comparatively high rates of divorce and separation among doll owners) and a lack of current relationships. That is, it is plausible that a history of relationship breakdowns leads doll owners to have a lack of understanding about female psychology, leading to the belief that women are fundamentally unknowable, and possibly threatening. In the context of not being in relationships, though, such beliefs about women are not activated, leading to reduced beliefs about the world being a dangerous or threatening place. Although these implicit theory clusters were not statistically significantly associated with doll ownership, the magnitude of their association with doll ownership was meaningful (i.e., above our stated SESOI) and are worthy of consideration here.

Arguably the most pivotal variable in relation to ongoing social discussions about sex doll ownership is that of sexual aggression proclivity. In the current sample, those who owned sex dolls were less likely to report a proclivity for sexual aggression. In a test of Seto’s (Citation2019) motivation-facilitation model, we found that doll ownership (as a proposed motivator) was not related to sexual aggression proclivity. In fact, sex doll ownership emerged as a potentially protective factor when owners possessed low levels of various moderating psychological traits, including implicit theories about the world being dangerous and the male sex drive being uncontrollable. At high levels of these traits (where sexual aggression proclivity may be at a higher level) we found no differences between doll owners and non-owners. To recap the premise of Seto’s (Citation2019) model, the effect of a motivating construct (here, sex doll ownership as a potential paraphilic interest) on sexual aggression proclivity will only be present when accompanied by offense facilitators. In our data, we found the relationship between doll ownership and sexual aggression proclivity to be moderated by two facilitating constructs: the dangerous world implicit theory, and the uncontrollable sex drive implicit theory. In each of these cases, higher scores on each of these moderating variables strengthened the positive relationship between doll ownership and aggression proclivity, consistent with Seto’s (Citation2019) model. However, there is an important caveat to this point. At high levels of these moderators (operationalized as +1 SD and above of the sample mean) there were no differences between doll owners and non-owners in their self-reported proclivities for sexual aggression. However, at low levels (operationalized as −1 SD and below of the sample mean) doll owners were significantly less likely to express a proclivity for sexual aggression. We are confident that describing these cutoff scores as being “low,” “moderate” and “high” on each moderator is broadly accurate (even if not exactly precise), given the average scores being close to the scale mid-points (2.59 for dangerous world implicit theory; 2.04 for the uncontrollability of sex drive implicit theory).

In general, our data suggest that men who own sex dolls are not notably different to non-owner comparators in many important ways. Although we set out to specifically provide preliminary data about personality profiles and risk, is it interesting to note this lack of differences, particularly when we might expect some of these variables to vary between the groups. For example, some theorists have posited that issues with attachment style might lead some men to withdraw from dating real women and instead focus on obtaining sexual and relational pleasure from dolls (Ciambrone et al., Citation2017). We found no effect of attachment, calling this conclusion into question. The lack of differences between the two groups in this study might suggest that studying sex doll ownership through a lens that assumes psychopathology or atypicality might be misguided. Instead, we advocate more functional analyses of doll ownership (akin to studying doll ownership using model three that we briefly set out in our Introduction), with the goal not being to explore why men might be interested in doll ownership, but how dolls are used and the effects that this ownership has on the lives of those who buy them.

Our data are potentially indicative of an emergent profile of sex doll ownership that might serve to inform a more reasoned and evidence-informed social discussion of this issue. Far from being dangerous individuals at a potentially high risk for sexual offending and objectification, as has been suggested in theoretical sociological and legal work (Carvalho Nascimento et al., Citation2018; Danaher, Citation2017b, Citation2017a; Kubes, Citation2019; Lancaster, Citation2021; Puig, Citation2017; Shokri & Asl, Citation2015), the data paint a perhaps more vulnerable picture rooted not in a hatred or contempt of women, but in a confusion or insecurity about them. These data are also at odds with the arguments presented by legal scholars who call for the criminalization of sex dolls or robots on the grounds that they potentially lead to an increase in sexual offending risk (Carvalho Nascimento et al., Citation2018; Danaher, Citation2017b, Citation2017a; Eskens, Citation2017; Puig, Citation2017). On the contrary, these data are indicative of a potentially attenuating effect of doll ownership on offending proclivity, with doll owners being less likely to express a behavioral willingness to engage in sexual aggression. Of course, our results are correlational and so causation cannot be suggested. However, any causal hypotheses stemming from our work would preclude the possibility of a direct effect of doll ownership due to the direction of the correlations between doll ownership and sexual aggression proclivity within our data.

Limitations and Future Directions

A key limitation of this work was the reliance on self-report methodologies, particularly in relation to contentious topics such as sexual objectification, sexual aggression proclivity, and implicit beliefs that might be supportive of sexual offending. Although we guaranteed anonymity by not tracking IP addresses or collecting any identifiable information, it is possible that participants responded in socially desirable ways to avoid increased perceptions of risk. This is particularly the case among the doll owning sample, who came to the study from a place of preexisting stigmatization from both social and professional angles (Harper & Lievesley, Citation2020). Future work might look to incorporate more indirect assessments of such constructs, such as implicit association tests built into online surveys (Carpenter et al., Citation2019), or direct behavioral observations within laboratory settings.

Our choice to not adjust our stated alpha level could be said to potentially lead to an increase in the Type I error rate (i.e., false positive results). However, Rubin (Citation2017) argued that alpha adjustments are unnecessary in exploratory research, unless tests are conducted that explore the same hypothesis within the same sample. This is not the case in the current study, where each variable represents an independent research question, in philosophical terms (e.g., whether attachment styles and paraphilic fantasies correlate with sex doll ownership are independent questions). Indeed, it is also plausible that there are changes to the probabilities of correctly or incorrectly accepting or rejecting any potential hypothesis. Alpha adjustment in such circumstances, from this perspective, make sense only if the complete collection of tests represent an examination of a universal null hypothesis. As Rubin (Citation2017) argued:

“it remains the case that the more hypotheses that a researcher tests, the greater probability that they will make a Type I error. However, this increased probability is distributed across the entire collection of hypotheses that are tested rather than localized to any one specific hypothesis. Consequently, it does not threaten the validity of any single test. If (a) researchers are interested in determining whether evidence supports or falsifies specific hypotheses rather than amorphous collections of hypotheses (i.e., universal null hypotheses), and (b) the probability that one hypothesis is true does not influence the probability that another hypothesis is true, then there is no need to adjust alpha levels for single tests of multiple hypotheses.” (p. 272)

Nonetheless, we have sought to limit our discussion of the data to those effects that are statistically meaningful from the perspective of their relative effect sizes, rather than relying on arbitrary p-values as a guide. In doing so, we believe that the results that we have highlighted represent some of the most viable candidates for predictors of sex doll ownership.

The data that we collected were cross-sectional and correlational in nature, meaning that causality is difficult to prove. Although we have made arguments within this paper about the ordering of psychological states in relation to sex doll ownership (e.g., when viewing negative affect as a precursor to ownership), these inferences cannot be conclusively supported by the data. Indeed, it might be that the societal stigma about sex doll ownership causes negative affect to increase among doll owners after they purchase a doll. The directional nature of these relationships can only be fully established in prospective longitudinal designs, and as such future research should look to explore this as a possibility. One approach might be for researchers to partner with doll manufacturers or vendors to capture baseline data at the time a new owner purchases a doll, and to then follow up these customers at regular time points to track change over time. Such an approach might also open up the possibility to explore dynamic variables that might predict changes in risk levels over time, such as motivations for doll ownership, sexual activity with dolls, and changes in social conditions (e.g., relationship status). This kind of naturalistic creation of an experimental condition may also be more feasible in the context of increasingly risk-averse ethical review committees in sex research, where the randomization of non-owning participants into a “doll owner” condition may lead to concerns about potential future risks. It may also be useful to explore the qualitative accounts of doll owners’ experiences in an explanatory manner to deepen our understanding of what our decontextualized quantitative data might be reflecting.

Although we sampled sex doll owners in a broad sense, we did not target any particular subgroup based on the function or circumstances of their doll ownership. Previous qualitative work has reported many motivations for owning a sex doll, including sexual gratification, physical or emotional intimacy, and medical treatment (Eichenberg et al., Citation2019; Fosch-Villaronga & Poulsen, Citation2020; Langcaster-James & Bentley, Citation2018; Morgan, Citation2009; Valverde, Citation2012). It might be that those owning a doll specifically for sexual gratification (vs. emotional companionship or health reasons) have a different psychological profile, but our sample was not large enough to conduct such an analysis. Future research might look to explore this further by recruiting doll owners from different places, such as health settings, to look at this potentially moderating effect. We also recruited participants by advertising the study as a test of the veracity of societal views about doll ownership. Although a specific analysis of explicitly defined myths was not possible in this work, we meant for this to reflect the over-arching aims of the work. However, it might also be that this primed participants to provide socially desirable answers. Although we do not believe this to be the case, replications of this work using different recruitment strategies might support our confidence in the authentic nature of the associations reported in this paper.

In this study we only focused on those who owned adult-like dolls due to the limited sample size for those whose dolls exclusively resemble children. Although we could have presented a comparison of the small number of child-like doll owners (n < 25) any analyses would have been substantially imbalanced. As such, targeted work continues to increase this number for comparative work to be undertaken in relation to this population. This is of particular importance, though, when considering that a large proportion of the existing theoretical literature targets child-like doll ownership for particular stigmatization (Brown & Shelling, Citation2019; Chatterjee, Citation2020; Danaher, Citation2017b, Citation2019b; Rutkin, Citation2016; Strikwerda, Citation2017). None of the conclusions drawn from the current study should be applied to this broader social discussion about the legal or moral status of child-like sex doll ownership.

Relatedly, we asked participants whether they owned a “sex doll,” which inherently possesses a lack of specificity. For example, some people might interpret this label as meaning inflatable dolls, others may have inferred that we meant realistic objects made from silicone or thermoplastic elastomer, and others might have thought that we were studying those who own models that possess artificial intelligence, or technologies that allow some degree of interaction between the doll and the owner. We did not ask for a description of the type of “doll” that was owned, meaning that it is plausible that each of these categories of doll are represented in our owner sample. Future work should look to explore differences in the psychological profiles of those who own unrealistic inflatables, realistic inanimate dolls, and interactive sex robots in as separate groups, as it remains possible that motivations, uses and effects of each of these types of doll will differ.

Conclusions

To conclude, this first psychological investigation of sex doll owners appears to support the view that doll ownership is a functional response to a history of poor quality or broken relationships, which in turn are possibly attributable to various beliefs about the unknowability of potential sex partners, less secure attachment styles, and poorer than average levels of sexual self-esteem. Contrary to sociological and legal arguments about the increased risk of sexual aggression, we found no evidence of an increased risk of sexual aggression among the sex doll owners in our sample. This is in spite of comparatively higher levels of offense-supportive cognitions, suggesting a potential protective quality to doll ownership in relation to sexual aggression. In sum, we hope that our data can advance a more evidence-informed social conversation about sex doll ownership, shifting the focus away from blanket criminalization and stigmatization and toward a functional analysis of how, why, and under what conditions dolls are incorporated into healthy sexual expression.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 To preserve participant anonymity, we have decided to refrain from explicitly naming the online forums used for data collection.

2 We are not aware of any theoretical or practical reason to handle non-exclusivity of attractions differently here than in other areas of sex research. That is, we are not aware of a reason to exclude somebody who may be incidentally attracted to children (on the basis of their doll ownership) from this sample, but retain somebody who may be incidentally attracted to adults in studies about people with pedophilic sexual attractions (a practice that is commonplace). In any case, we cannot make claims about sexual orientations for age in the data that we have available, and ‘child like’ doll ownership might be related to a host of factors, including cost of shipping or practicality. As such, we decided to exclude only those who we could make a defensible assumption of sexual attractions to children (either self-reported, or via exclusive child-like doll ownership).

3 Due to the small subsample of participants who owned child-like sex dolls, we only report data pertaining to the sexual aggression proclivity scale in this paper.

4 This was consistent with our ethical approval and the informed consent procedure, whereby study withdrawal followed a specific process of contacting the research team and quoting a unique participant code.

5 A further model produced a significant moderation by “sexual objectification” (i.e., behaviors that objectify women, such as cat-calling and leering at sexual body parts). This is not reported in text as this scale was omitted from earlier parts of the paper, but the model outputs can be found on the project’s OSF page (https://osf.io/7nsuh/).

References

- Beech, A. R., Bartels, R. M., & Dixon, L. (2013). Assessment and treatment of distorted schemas in sexual offenders. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 14(1), 54–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524838012463970

- Berdychevsky, L., Nimrod, G., Kleiber, D. A., & Gibson, H. J. (2013). Sex as leisure in the shadow of depression. Journal of Leisure Research, 45(1), 47–73. https://doi.org/10.18666/jlr-2013-v45-i1-2942

- Bernard, P., Loughnan, S., Marchal, C., Godart, A., & Klein, O. (2015). The exonerating effect of sexual objectification: Sexual objectification decreases rapist blame in a stranger rape context. Sex Roles, 72(11–12), 499–508. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-015-0482-0

- Bohner, G., Reinhard, M.-A., Rutz, S., Sturm, S., Kerschbaum, B., & Effler, D. (1998). Rape myths as neutralizing cognitions: Evidence for a causal impact of anti-victim attitudes on men’s self-reported likelihood of raping. European Journal of Social Psychology, 28(2), 257–268. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-0992(199803/04)28:2<257::AID-EJSP871>3.0.CO;2-1

- Brankley, A. E., Babchishin, K. M., & Hanson, R. K. (2021). STABLE-2007 demonstrates predictive and incremental validity in assessing risk-relevant propensities for sexual offending: A meta-analysis. Sexual Abuse, 33 (1) 34–62. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219871572

- Bridges, A. J., Sun, C. F., Ezzell, M. B., & Johnson, J. (2016). Sexual scripts and the sexual behavior of men and women who use pornography. Sexualization, Media, & Society, 2(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1177/2374623816668275

- Brooks, R., Shelly, J. P., Fan, J., Zhai, L., & Chau, D. K. P. (2010). Much more than a ratio: Multivariate selection on female bodies. Journal of Evolutionary Biology, 23(10), 2238–2248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1420-9101.2010.02088.x

- Brown, R., & Shelling, J. (2019). Exploring the implications of child sex dolls. Australian Institute of Criminology.

- Buss, D. M. (2021). When men behave badly: The hidden roots of sexual deception, harassment, and assault. Little, Brown Spark. https://www.hachettebookgroup.com/titles/david-buss-phd/when-men-behave-badly/9780316419352/

- Butler, L., & Bartels, R. M. (2018). Development of a rape-related implicit theories measure. [ Unpublished master’s thesis]. University of Lincoln.

- Carpenter, T. P., Pogacar, R., Pullig, C., Kouril, M., Aguilar, S., LaBouff, J., Isenberg, N., & Chakroff, A. (2019). Survey-software implicit association tests: A methodological and empirical analysis. Behavior Research Methods, 51(5), 2194–2208. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-019-01293-3

- Carvalho Nascimento, E. C., da Silva, E., & Siqueira-Batista, R. (2018). The “use” of sex robots: A bioethical issue. Asian Bioethics Review, 10(3), 231–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41649-018-0061-0

- Cassidy, V. (2016). For the love of doll(s): A patriarchal nightmare of cyborg couplings. ESC: English Studies in Canada, 42(1), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1353/esc.2016.0001

- Chatterjee, B. B. (2020). Child sex dolls and robots: Challenging the boundaries of the child protection framework. International Review of Law, Computers & Technology, 34(1), 22–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600869.2019.1600870

- Ciambrone, D., Phua, V., & Avery, E. (2017). Gendered synthetic love: Real dolls and the construction of intimacy. International Review of Modern Sociology, 43(1) 59–78 . https://cupola.gettysburg.edu/socfac/32

- Cox-George, C., & Bewley, S. (2018). I, sex robot: The health implications of the sex robot industry. BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, 44(3), 161–164. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2017-200012

- Cumming, G. (2014). The new statistics: Why and how. Psychological Science, 25(1), 7–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797613504966

- Danaher, J., Earp, B. D., & Sandberg, A. (2017). Should we campaign against sex robots? In J. Danaher & N. McArthur (Eds.), Robot sex: Social and ethical implications (pp. 47–72). MIT Press.

- Danaher, J. (2017a). Robotic rape and robotic child sexual abuse: Should they be criminalised? Criminal Law and Philosophy, 11(1), 71–95. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11572-014-9362-x

- Danaher, J. (2017b). The symbolic-consequences argument in the sex robot debate. In J. Danaher & N. McArthur (Eds.), Robot sex: Social and ethical implications (pp. 103–132). MIT Press.

- Danaher, J. (2019a). Building better sex robots: Lessons from feminist pornography. In Y. Zhou & M. H. Fischer (Eds.), AI love you: Developments in human-robot intimate relationships (pp. 133–147). Springer.

- Danaher, J. (2019b). Regulating child sex robots: Restriction or experimentation? Medical Law Review, 27(4), 553–575. https://doi.org/10.1093/medlaw/fwz002

- Deehan, E. T., & Bartels, R. M. (2021). Somnophilia: Examining its various forms and associated constructs. Sexual Abuse, 33(2), 200–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/1079063219889060

- Del Zotto, M., & Pegna, A. J. (2017). Electrophysiological evidence of perceived sexual attractiveness for human female bodies varying in waist-to-hip ratio. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 17(3), 577–591. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-017-0498-8

- Diamond, M., Jozifkova, E., & Weiss, P. (2011). Pornography and sex crimes in the Czech Republic. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(5), 1037–1043. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-010-9696-y

- Dixson, B. J., Grimshaw, G. M., Linklater, W. L., & Dixson, A. F. (2011). Eye-tracking of men’s preferences for waist-to-hip ratio and breast size of women. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 40(1), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-009-9523-5

- Döring, N., & Pöschl, S. (2018). Sex toys, sex dolls, sex robots: Our under-researched bed-fellows. Sexologies, 27(3), e51–e55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sexol.2018.05.009

- Eichenberg, C., Khamis, M., & Hübner, L. (2019). The attitudes of therapists and physicians on the use of sex robots in sexual therapy: Online survey and interview study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 21(8), e13853. https://doi.org/10.2196/13853

- Eskens, R. (2017). Is sex with robots rape? Journal of Practical Ethics, 5(2), 62–76 https://www.jpe.ox.ac.uk/papers/is-sex-with-robots-rape/.