ABSTRACT

Based on different theories in media research (3AM, catalyst model of violent crime, reinforcing spirals model), we further explore the relationship between pornography use, sexual fantasy, and behavior. We suggest that pornography use appears so persistent across time and culture because it is related to a human universal, the ability to fantasize. Consequently, pornography use seems to be an opportunity to acquire media-mediated sexual fantasies, and we believe that pornography use interacts with sexual fantasies and, to a much weaker extent, with sexual behavior. To assess our assumptions, we conducted a network analysis with a large and diverse sample of N = 1338 hetero- and bisexual participants from Germany. Analyses were done separately for men and women. Our network analysis clustered parts of the psychological processes around the interaction of sexual fantasies, pornography use, and behavior into communities of especially strong interacting items. We detected meaningful communities (orgasm-centered intercourse, BDSM) consisting of sexual fantasies and behavior, with some containing pornography. However, pornography use was not part of communities we perceive to account for mainstream/everyday sexuality. Instead, our results show that non-mainstream behavior (e.g., BDSM) is affected by pornography use. Our study highlights the interaction between sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and (parts of) pornography use. It advocates for a more interactionist view of human sexuality and media use.

Introduction

Research about the (potential) effects of pornography use is thriving in the field of sexual science but is mostly neglected in mainstream media psychology and communication science (Grubbs & Kraus, Citation2021; Kohut et al., Citation2020). The term pornography refers to “any type of sexually explicit material that has the intent of producing arousal in those who consume it” (Lehmiller, Citation2017, p. 402). A possible reason for this lack of scientific attention is a fear of stigmatization, which porn researchers are often confronted with (Kohut et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, the field is underfunded (Grubbs & Kraus, Citation2021).

However, given the reach and widespread use of pornography (e.g., Hald & Mulya, Citation2013; Martyniuk & Dekker, Citation2018; Price et al., Citation2016), it is a genuine mass media content whose clicks surpass even those of the most prominent news outlets. BBC.co.uk is the world’s most clicked news outlet, and in its most successful month ever (March 2020), it had about 1.5 billion page views (BBC, Citation2020). In comparison, the pornographic content provider Pornhub, which is not even the largest provider on the Internet, attracts about 130 million visits every day, accumulating to an average of 3.9 billion views per month (Pornhub Insights, Citation2021). This shift in perspective – highlighting pornography as mass media content – allows us to apply different theories about media use and effects originating from communication science and media psychology research on mass media (Ferguson et al., Citation2008; Slater, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020). Given that pornography reaches a global audience (e.g., Hald & Mulya, Citation2013), its use (and production) appears to be motivated by something universal to human nature. For instance, even the combination of very strict anti-pornography legislation and widespread Islamic faith did not make its use disappear in Indonesia (Hald & Mulya, Citation2013). Instead, erotic cultural output, which can reasonably be perceived as being created with the intent of causing sexual arousal in its users and therefore classifies as pornography, frequently (re-)appears independent of time or culture (Lehmiller, Citation2017; Schmidt & Voss, Citation2000). The Turin erotic papyrus drawn in old Egypt displays sex scenes so vividly that it gained attention from urology (Shokeir & Hussein, Citation2004). This is only one example of a potentially endless amount of historical sexually explicit findings (Schmidt & Voss, Citation2000). Recognizing these findings, humans seem to have always tended to externalize their sexual fantasies through communication and, subsequently, mediated communication (Ohler & Nieding, Citation2005; Shokeir & Hussein, Citation2004). The phenomenon of “modern” pornography might only be molded but not caused by today’s culture because it is driven by the basic human need for sexuality (e.g., Lippa, Citation2009) and shaped by a universal human capability, which is to fantasize. If this is the case, we may be able to observe reciprocal interactions between sexual behavior, sexual fantasies, and pornography use. Relations between these dimensions have been described both in theories about the development of sexual behavior (e.g., Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014) as well as in theories of broader communication science and media psychology (e.g., Ferguson et al., Citation2008; Slater, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020).

Different Perspectives on the Complex Reciprocal Interaction of Pornography Use, Sexual Fantasies, and Sexual Behavior

Different scholars have emphasized the relations between sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use (Slater, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020; Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014). The script acquisition, activation, application model (3AM; Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014) mentions the impact of sexual fantasies on the relations between pornography use and sexual behavior. It argues that pornography provides its users with socially constructed behavior scripts (acquisition), can activate prior acquired scripts (activation), and encourages them to utilize scripts by depicting certain sexual behaviors to be appropriate and rewarding (application; Wright et al., Citation2021). According to the 3AM, sexual fantasies can support the acquisition of behavior scripts by pornography use because the media sparks fantasies that allow rumination and rehearse the pornographic content used (Wright, Citation2011). Furthermore, these fantasies may be accompanied by masturbation, a form of enactive rehearsal that will increase the accessibility of related scripts because the fantasies yield rewarding outcomes in the form of an orgasm. However, pornography users do not automatically acquire or apply all behavior scripts they encounter. All three processes of script acquisition, activation, and application depend on different audience, content, accessibility, and situational variables (Wright, Citation2011).

This assumption of mediators being present for a media effect to occur is reflected in another model that formalizes media use and effects. The catalyst model of violent crime (CMVC; Ferguson et al., Citation2008) assumes that adverse media effects are small and have only minor, almost negligible effects on an audience’s behavior. According to the CMVC, media use is never the root of specific behavior but acts as an indirect influence, altering the visual display of how behavior is conducted. For instance, a person with a disposition for acting violently (exemplarily caused by a troubled upbringing or a lot of proximate life strain) might be interested in violent pornography and, due to the mediation of this disposition, acquire and apply adverse scripts of sexual behavior previously encountered in pornography. In the original CMVC, fantasies would be hypothesized to predispose this only stylistic influence of media use on behavior, which Ferguson et al. (Citation2008) called a stylistic catalyst.

Contrary to this, we do not assume a predisposition of fantasy to pornography use and behavior but rather a reciprocal interaction between sexual fantasies and pornography use and behavior. However, fantasies are very volatile and diverse and might depend on less impactful, if any, mediator variables (Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014) to interact with pornography use compared to actual behavior (Joyal et al., Citation2015; Lehmiller, Citation2018; K. M. Williams et al., Citation2009). Therefore, fantasies should occur more often in reciprocal relations with pornography use than actual sexual behavior.

We assume an interaction between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and behavior. Sexual fantasies might not only be a rumination of pornography use, as described by Wright (Citation2011, Citation2014). Pornography use might as well be a rumination of sexual fantasies. This exchange could lead to a potentially long-lasting interaction where fantasies and previous behavioral experiences trigger the demand for novel pornography use, and the use of novel pornographic content triggers more fantasies, leading to a renewed demand for pornography. To formalize this process, the reinforcing spirals model (RSM; Slater, Citation2007, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020) comes to mind, which theoretically supports such an interaction between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and (possibly) subsequent behavior. It proposes that people tend to select communication sources and content that best matches their own beliefs and social identity, and in turn, beliefs and behaviors are reinforced by such communication selectivity. In the long run, this can lead to a strong attachment to the respective communication sources and content. Applying the RSM to pornography use in the terminology of the 3AM, users would be initially prone to select pornographic content that matches their existing fantasies and behavioral scripts. Their pornography use may then act as a source of inspiration, possibly reinforcing a particular style of sexuality-inclusive coherent behavior and fantasies (e.g., Bondage-Dominance-Sadism-Masochism [BDSM] enthusiast, fetishists) in the long run.

In summary of our assumptions, we perceive pornography use at its core as a mass media-mediated way to use externalized sexual fantasies. Pornography use can both spark sexual fantasies and, in rare cases, “inspire” behavior or will be more often a reaction to fantasies “outsourcing” parts of the cognitive processes around sexual fantasies into media content. These processes will create a reciprocal interaction between an individual’s fantasies and pornography use and possibly (if only slightly) affect the audience’s behavior (Ferguson et al., Citation2008; Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014).

The Network Approach

We use a network approach to examine the amount of interaction between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and behavior (e.g., Newman, Citation2018). The approach provides excellent potential for a more nuanced view of pornography usage and effects than previously possible. Different elements of interest are conceptualized within a system of pairwise interactions. In contrast to directed relations, pairwise interactions in networks are considered reciprocal and do not bear a causal meaning. Thus, networks represent a complex system of elements influencing each other. From the network perspective, sexual behavior is neither caused by sexual fantasies nor pornography consumption. Instead, the examined variables influence each other. In this way, a network allows modeling our assumed reciprocal relations between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and sexual behavior. If our data should yield evidence for complex interactions between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and behavior, then a network analysis should provide an accurate and stable network.

In network terminology, the elements of a network that represent the variables of interest are called nodes, and the reciprocal interactions between the nodes are called edges. An edge connects two nodes in a network, and the set of all edges forms it. The edges represent the pairwise interaction between the nodes. From a statistical perspective, edges are represented by partial correlation (cf., D. R. Williams et al., Citation2019). The edges represent the degree of association between two variables (nodes) with the effects of the other variables in the network controlled for. Thus, the edges describe the interactions between a pair of nodes indeed. Edges are typically judged according to their strength and if the edge represents a positive or negative relation.

Typically, in a network, there are subsets of nodes that are more closely related to each other than other nodes. In other words, the distribution of edges is inhomogeneous, i.e., there are groups of nodes so that the frequency of edges within a group of nodes is high, whereas the frequency of edges between the group’s nodes and nodes belonging to other groups is low. Such groups with a high number of internal connections are called communities. All communities form the community structure of a network. Communities contain nodes that probably share common properties and play similar roles within the network (Fortunato, Citation2010). Regarding the reciprocal interaction between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and behavior, one can ask if pornography use, fantasies, and behaviors belong to the same style of sexuality, e.g., BDSM, and should form a community. In sum, the network perspective allows conceptualizing broad patterns of psychological phenomena as properties that emerge from the interactions among certain behaviors and cognitions (Costantini et al., Citation2019).

Network analyses have recently been used in media research to show that active and passive social media use is, on average, very weakly related to depressive symptoms (e.g., Rodriguez et al., Citation2022) though, associations differed substantially among individuals, highlighting differences in the susceptibility for a negative media influence to occur. This importance of individual differences is comparable to our assumptions about weak media effects derived from the 3AM and the CMVC. A comparable general but crucial individual difference variable would be sex. Men appear at a higher risk for adverse effects of pornography use as they show an, on average, higher disposition for violence (Ferguson et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, one of the most replicated findings in pornography research is that men use on average more pornography, show different usage patterns and prefer different content types than women (Hald & Štulhofer, Citation2016; Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010; von Andrian-Werburg et al., Citation2022). Adding this to our reasoning about pornography use, sexual fantasies, and behavior, we asked separately for each sex:

RQ1: Can sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use be modeled in a network?

RQ2: Can we detect different communities (in the networks) of reciprocally interacting sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use pointing toward a meaningful interpretable style of sexuality?

Method

We advertised an online questionnaire exclusively for adult participants in social media groups and online forums in Germany. Previous results of Hald and Štulhofer (Citation2016) showed different pornographic content preferences depending on sex and sexual orientation. Therefore, we decided to address our research question separately by sex and only to choose participants who were at least somewhat sexually attracted to the opposite sex (self-labeled hetero- and bisexuals). The analysis required a large sample size, and the prevalence of participants with an exclusively homosexual orientation for a separate analysis appeared too low in a convenience sample (e.g., Greaves et al., Citation2017).

The questionnaire was initially clicked 28,457 times, which resulted in 1496 complete questionnaires. After a first data screening, we excluded 38 participants that reported to be younger than 18 years, as this is the legal age in Germany to consent for participating in scientific studies. This yielded a sample size of 1458 participants. Of these, we excluded the fastest 2.5%, who answered the questionnaire in less than 11 minutes as it took more than 20 minutes on average to complete the questionnaire. Of the remaining 1448 participants, we excluded 11 participants who did not identify as male or female. Furthermore, we excluded 81 participants who did not disclose their sexual orientation and 25 who exclusively identified as homosexual. 1342 participants remained. After these steps, further screening was conducted, separated by sex. The male sample contained 546 participants, and the female sample contained Nfemale = 796 participants. In the male sample, three participants had more than 18 consecutive missing values on the scales relevant for this paper, and one participant had five missing values spread over all relevant scales. We excluded all cases with five or more missing values on all items in our analysis, resulting in a new sample with Nmale = 542 participants. For the remaining participants, missing individual values were replaced with the median. No participant in the female group had more than five missing values, and all participants remained part of the sample. All assessed demographic characteristics of the final sample are displayed in .

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Measures

A professional translator who was not informed about the research objective translated the English scales into German. The same 5-point intensity scale was used for the scales assessing pornography preferences, sexual fantasies, and behavior described in this section. Its labels started with the minimum 1 = never, 2 = rarely, 3 = occasionally, 4 = often, to the maximum 5 = always. We treated all items as ordinal because many items in the sex fantasy questionnaire (Wilson, Citation1988, Citation2010) and of the 27 different types of pornography (Hald & Štulhofer, Citation2016) assess comparable uncommon pornography use and sexual acts. For instance, the Sex Fantasy Questionnaire (SFQ) asks if participants had ever had or fantasized about a sexual encounter with an animal (Wilson, Citation1988, Citation2010). Consequently, many items are strongly skewed by nature, and this skewness leads to a severe variance reduction for them.

Sexual Orientation

We assessed sexual orientation with a continuous scale ranging from 0 = exclusively homosexual to 100 = exclusively heterosexual to allow participants to express nuances regarding their inclination toward a sexual orientation.

Types of Pornography

We assessed 26 of the 27 types of pornography (TOP; Hald & Štulhofer, Citation2016). These types were empirically derived and initially clustered by Hald and Štulhofer (Citation2016) to obtain a more differentiated view on pornography use. They denominate pornographic content categories or genres and range from “mainstream content” (e.g., “amateur,” “oral sex”) to what Hald and Štulhofer (Citation2016) called “non-mainstream/ paraphilic” content (e.g., “Bondage and dominance,” “sadomasochism”). We excluded the type labeled “other” as its ambiguity did not suit our analysis. Before carrying out the TOP assessment, we asked: “How often do you watch movies from the following porn categories?”

Sexual Fantasy and Behavior Questionnaire

To assess sexual fantasies and behavior, we used the 40 labels of the SFQ (Wilson, Citation1988, Citation2010). Daytime fantasies and actual sexual behavior are reported on the same 40 items originally distinguished into four factors subsuming ten items each: Exploratory sexual fantasies & behavior (e.g., “Sex with two other people”), intimate sexual fantasies & behavior (e.g., “Making love outdoors in a romantic setting like a field of flowers or a beach at night”), impersonal sexual fantasies & behavior (e. g., “Intercourse with an anonymous stranger”), and sadomasochistic sexual fantasies & behavior (e. g., “Being forced to do something”). Equal to the TOP items, all items were treated to be single items for the analysis. To introduce the assessment of sexual fantasies, we asked: “Please indicate how often you fantasize about the statements below on an average day.” To introduce the assessment of sexual behavior, we asked: “Please indicate how often you act out the statements below in reality.”

Network Analysis

To analyze the possible reciprocal relations between the items from the TOP and SFQ data, we used a network analysis (e.g., Borsboom & Cramer, Citation2013; Epskamp & Fried, Citation2018; Epskamp et al., Citation2017). All TOP and SFQ items were used as single items. Because networks describe pairwise interactions between variables in partial correlations, they correspond to a Gaussian graphical model described by the precision matrix, i.e., the inverse of the variables’ correlation matrix (cf, Epskamp et al., Citation2017; D. R. Williams et al., Citation2019). The precision matrix is a standardized matrix in which the entries with reversed signs correspond to a partial correlation matrix. These partial correlations describe the pairwise interactions between the variables, i.e., the edges in the network.

Network Estimation, Accuracy, and Stability

Concerning RQ 1, we considered the estimation of the network as well as its accuracy and stability. If pornography use and the corresponding sexual fantasy and behaviors form reciprocal interactions, it should be possible to find networks that are firstly accurate, i.e., not affected by sampling variability, and secondly stable, i.e., their interpretation remains stable. To estimate the network structure, we used a nonregularized estimation (D. R. Williams et al., Citation2019) that draws on significance tests of the partial correlations representing the edges to determine which edges are included in the network.

We used Spearman correlations to deal with the ordinal characteristic of the rating scale belonging to the TOP and SFQ items. For this correlation matrix, the precision matrix is estimated that represents the partial correlation between the variables. For each partial correlation, a significance test is conducted to determine if the edges are kept in the network or are removed. Because of the exploratory nature of this study, we used a nominal α = .05 level. Those edges where α is larger than the significance level are discarded from the network.

We examined the accuracy of the resulting edge weights. Accuracy indicates how prone the estimated edge weights are to sampling variation. The bootstrap method is a way to assess this accuracy (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). To be accurate, the bootstrap mean of the edge weights should be close to the estimated edge weight value. The number of bootstrap samples we drew was 5000.

We also evaluated the stability of the network. Stability indicates how similar the interpretation remains when there are fewer observations (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). A method to examine the stability is the case-dropping subset bootstrap. In each bootstrap, a certain proportion of the cases is dropped from the analysis, and the correlation between the original estimates and those obtained from the bootstrap sample is calculated (Epskamp et al., Citation2018). The CS(τ) coefficient represents the maximum proportion of cases that can be dropped so that the correlation between the original estimate and the bootstrap estimate from the case-dropping subset exceeds a given threshold τ. Epskamp et al. (Citation2018) suggested that CS(τ) should at least be greater than 0.25 and preferably greater than 0.50. The parameter τ indicates how strong the correlation between the original estimates and those obtained from the bootstrap sample should be. We computed the CS(τ) coefficient for our analysis of the edge weight. We chose a τ = .50 because, according to Cohen (Citation1988), a correlation of at least .50 indicates a strong effect. However, Epskamp et al. (Citation2018) chose a τ = .70. Therefore, we considered the CS(τ) coefficients in the range from τ = .50 to τ = .70 to assess the stability of our networks. The number of case-dropping subset bootstrap samples we drew was 5000.

Community Detection and Graphical Display

To answer RQ 2, we examined if there were communities in the network. To detect communities in the networks, we used the Spinglass algorithm (e.g., Yang et al., Citation2016). The basic principle of the Spinglass algorithm is that nodes belonging to the same community should be connected, whereas nodes belonging to different communities should not be connected. A node can only be in one community. Thus, the Spinglass algorithm provides communities in which the nodes belonging to the same communities are more interconnected with each other than with nodes belonging to other communities. Because the Spinglass algorithm is not stable, i.e., it provides different results in different runs, we first calculated the number of resulting communities for 100 different runs, each having a different and unique seed (Briganti et al., Citation2018). For the 100 runs, we determined the number of communities detected in each run, computed the median for the number of communities, and selected this number as the final number of communities.

Finally, the networks were plotted with grouped and color-coded nodes belonging to a community. Nodes are represented by circles, and edges are represented by lines where blue lines indicate a positive pairwise interaction and red lines indicate a negative pairwise interaction.

For all computations, we used the R software (R Core Team, Citation2020). We used the igraph package (Csardi & Nepusz, Citation2006) for community detection and the package qgraph (Epskamp et al., Citation2012) to plot the networks. The networks were estimated and bootstrapped with the bootnet package (Epskamp et al., Citation2018).

Final Data Screening

Despite our ordinal approach, we recognized that some of the items did not show any reasonable amount of variation. Therefore, we implemented a final screening procedure before we included the items in the network analysis to ensure a minimum variability in the data. Thus, we set the exclusion criterion that all items must have an interquartile range (IQR) greater than zero.

Results

Descriptive statistics of all items can be found in Online supplementary Table 1 for male and Table 2 for female participants. Excluded items are crossed out in respective tables. In this way, from the total of 106 items originally used, 82 items fulfilled this criterion for the male sample, and 62 items fulfilled the criterion for the female sample.

Table 2. Interpretation table of the male network including communities, node abbreviations and item-labels.

Network for Males

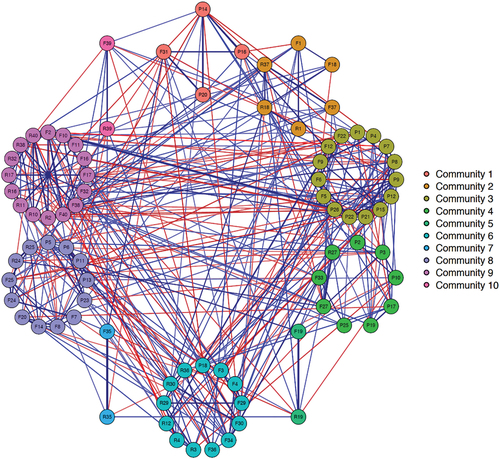

The network for the male sample is shown in . There are 10 Spinglass communities in the network. The communities are ordered in a counterclockwise direction on a fictive circle. The colored dots represent the nodes. The letters F, R, or P denominate if the respective node is either fantasy, behavior (in reality: R), or pornographic content, followed by a number to denominate a respective item label displayed in online supplementary Table 3.

Figure 1. Network for the male sample with color-coded communities. Blue edges represent positive relations and red edges negative relations.

Additionally, the communities are marked by equally colored nodes and are also grouped in the form of fictive geometric shapes. For instance, Community 1 at the noon position is represented by the orange nodes in a diamond shape, Community 2, approximately at the 1 o’clock position, is represented by the brown nodes in a hexagon shape, and Community 3, approximately at the 2 o’clock position, is represented by the tan nodes ordered in a circle. In general, shows connections between the nodes belonging to a community. However, the figure also shows many connections between nodes belonging to different communities.

We provide the interpretation of the communities below, but first, we look at the stability analysis results. Bootstrap results are shown in . The plot shows estimates of the edges on the horizontal axis and the absolute value of the difference between the estimate and its bootstrap mean on the vertical axis. The differences are relatively small for almost all estimates of edge weights. In particular, for the positive edge weights that are greater than .15, the difference is below 0.01. For the negative edge weights that are smaller than about −.15, the difference is below 0.01. Another obvious result is the tail on the right side of the graph, indicating a number of edges with large positive edge weights that are not mirrored on the side of the edges with negative edge weights.

Figure 2. Bootstrap results for accuracy estimation of the male network. The x-axis displays the size of the estimated partial correlation. The y-axis displays the estimates deviation from the bootstrap mean (m = 5000).

Given the results in general, the estimates are accurate. Please note that the “vast area” between the negative and positive edge weight estimates results from the exclusion of these edges due to them not being statistically significant. In this way, the plot also shows that the minimal partial correlation in the network is a little bit below ± .10 and that there is generally a wider range of positive partial correlation than negative partial correlation. Concerning the stability, the stability coefficients are CS(.50) = .59, CS(.60) = .52, and CS(.70) = .44. Moreover, the plot indicates that the absolute difference between the estimate and its bootstrap mean is generally greater for smaller partial correlation coefficients than for the larger ones. However, the absolute difference is rather small, marginally exceeding 0.03, and in sum, the network estimates are stable.

Regarding RQ1 for the male network, we can sum up that for men, the relation between pornography use, sexual fantasies, and sexual behavior can be modeled in the form of a stable and accurate network.

Community Interpretation of Men’s Network

For the male sample, there was indeed a community structure. An interpretation table containing the communities, abbreviations, and labels of the items can be found in . The table indicates the community number in the first column. The following columns contain the item number depicted in the nodes and the meaning of the individual item

Community 1 (noon position, orange nodes in a diamond shape) of the male network is maturity-centered with fantasies and pornography use relating to female sex partners’ post-juvenile age and appearance. The pornography nodes physiognomically form an overweight mature female body with big breasts. Matching behavior was excluded in the final data screening.

Community 2 (approx. 1 o’clock position, brown nodes in a hexagon shape) is about stimulating objects and places like outside a bed or using objects to possibly further increase sexual pleasure. Subsuming the items, one would imagine a vivid sex scene at a beach or in a house outside the bedroom. For this community, we suspect the absence of pornography use is caused by TOPs, not including fitting pornography types (e.g., outdoor).

Community 3 (approx. 2 o’clock position, tan nodes in a circle shape) is about an orgiastic setting with mate swapping, group sex, watching others have sex, homo- and bisexual activities, bukkake, and cumshots. These labels compose scenes of intercourse during an orgy. Of the matching behavior, four of the five items were excluded in the final data screening. Therefore, most men seem not to act out on such behavior. It should be mentioned that R12 (watching others have sex) is attached to community 6 (promiscuous and diverse sexuality).

Community 4 (approx. 4 o’clock position, green nodes in a circle shape) is about non-mainstream coprophilic sexual acts, including pornography use about fisting, anal sex, and golden showers/enemas. Men whose questionnaire reports fit this community tended to expose themselves provocatively in fantasy and behavior. Behavior that matched the fantasy of being seduced as an “innocent” was screened out prior to analysis.

Community 5 (approx. 5 o’clock position, only two light-green nodes in a bar shape) represents the fetish of “being excited by material or clothing” with the matching fantasy and behavior nodes. We assessed potentially fitting pornography use with P11 (Fetish [including latex]). However, this node is attached to community 8 (BDSM).

Community 6 (6 o’clock position, turquoise-green nodes in a circle) is about promiscuous and diverse sexuality. It seems to reflect the desire and enactment of promiscuous sex with younger partners who are pictured as inexperienced and partners of varying physical appearance. Given the appearance of R12 in this community, it appears that watching others have sex (R12) creates a stronger attachment through its impersonality compared to its “natural” cooccurrence when participating in an orgy (community 3).

Community 7 (approx. 7 o’clock position, only two blue nodes in a bar shape) is about sexual failure containing two matching fantasy and behavior nodes labeled “being embarrassed by failure of sexual performance.” In our sample, we interpret this community as related to fears and experiences of failing during intercourse.

Community 8 (approx. 8 o’clock position, blue-gray nodes in a circle) is about BDSM. The fantasies (whipping or spanking someone, hurting a partner) and pornography use (violent sex [simulated rape, aggression, and coercion]) appear to be more extreme compared to actual behavior reported, such as being tied up or tying someone up. The remaining behaviors that match those fantasies were screened out prior to analysis.

Community 9 (approx. 10 o’clock position, violet nodes in a circle) appears to be men’s “vanilla” community with nodes about sexual fantasies like receiving oral sex, taking someone’s clothes off, or having intercourse with a loved partner. The fantasy nodes are perfectly reflected by their eight behavioral counterparts. It is worth mentioning that assessed pornography use was not associated with these “every day” sexual behaviors and fantasies. Potentially matching pornography use (e.g., P1: Amateur, P21: Oral Sex, P26: Vaginal Sex) was included in the network but attached to different communities.

Community 10 (approx. 11 o’clock position, only two rose nodes in a bar shape) is about looking at obscene pictures or films. Therefore, it assesses the frequency of pornography use. It should be mentioned that the community does not include any of the TOP nodes.

Regarding RQ2 for the male network, we can state that it was possible to detect meaningful communities of reciprocally interacting sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use of the same style of sexuality. However, one should bear in mind that due to the exclusion of some items, not all corresponding sexual fantasies, behaviors, and types of pornography have corresponding elements in the communities.

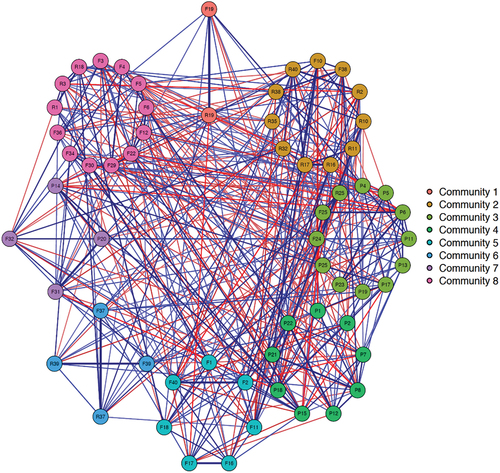

Network for Females

The network for the female sample is shown in . There are 8 Spinglass communities in the network. The structure of the figure is comparable to . As in the male network, there are not only edges between the nodes of a community but also edges between the nodes belonging to different communities. The results of the bootstrap are shown in . The absolute values of the difference between the estimate and the bootstrap means are smaller for the female network than the male network, indicating an even higher accuracy. Like in the male network, the differences for the edge weights larger than 0.20 have a minimal difference not exceeding 0.005. Additionally, the same pattern of a set of positive edges with a distinct small difference also emerged in the female network, i.e., the tail on the right side. Therefore, the estimated edge weights for this network are accurate, too. Concerning the stability, the stability coefficients are CS(.50) = .67, CS(.60) = .59, and CS(.70) = .44. As for the male network, the estimates for the female network seem stable.

Figure 3. Network for the female sample with color-coded communities. Blue edges represent positive relations and red edges negative relations.

Figure 4. Bootstrap results for accuracy estimation of the female network. The x-axis displays the size of the estimated partial correlation. The y-axis displays the estimates deviation from the bootstrap mean (m = 5000).

Comparable to the male sample, females’ sexual fantasies, pornography use, and sexual behavior result in an accurate and stable network so that we can positively answer RQ1 for the female sample.

Community Interpretation of the Women’s Network

We now turn to the communities of the female network and their interpretation. An interpretation table of their eight communities can be found in .

Table 3. Interpretation table of the female network including communities, node abbreviations and item-labels.

Community 1 (noon position, only two orange nodes in a bar shape) of the female sample consists of two nodes representing the Fetish of being excited by material or clothing in fantasy and behavior. Comparable with community 5 of the male sample (Fetish), none of the pornography use assessed was related to the community, even though suitable types remained in the analysis (e.g., P11 Fetish (including latex)).

Community 2 (approx. 1 o’clock position, brown nodes in a circle) centers around orgasm-focused “vanilla” intercourse. It is worth mentioning that women reported having fewer fantasies regarding this community compared to the male sample (community 9). Women reported being embarrassed by the failure of sexual performance, which in our interpretation, reflects the pressure to orgasm during intercourse. Again, potentially proper pornography use was part of the analysis but did not attach to the community. It subsumes in community 4 (penetration-centered group sex).

Community 3 (3 o’clock position, green nodes in a circle) is centered around BDSM. A rough interplay of pornography use (e.g., violent sex, sadomasochism, bondage, and dominance) accompanies the fantasies of “being tied up” and “tying someone up.” Interestingly, only the active action of “tying someone up” is part of this community as the only behavior. The passive action of “being tied up” was excluded in the final data screening.

Community 4 (approx. 5 o’clock position, light green nodes on a circle) is a community exclusively consisting of pornography nodes that center on the interaction around penetration-centered group sex with TOP labels like orgy, large penises, gang bang, and bukkake. Potentially matching fantasies (e.g., giving oral sex) and behavior were assessed but did not attach to this community.

Community 5 (6 o’clock position, turquoise nodes in a heptagon shape) reflects the desire to have passionate outdoor sex consisting of sexual fantasy nodes only about making love outside the bedroom or outdoors and having intercourse with a loved partner. Potentially matching pornography use was, as for the men, not part of the TOP items.

Community 6 (approx. 6 o’clock position, blue nodes in a diamond shape) is masturbation centered revolving around masturbation with objects while looking at obscene pictures or films. The community assesses (parts of) the frequency of pornography consumption and females’ masturbation behavior. Interestingly, no specific TOP items are attached to the community, comparable to the male sample.

We interpret community 7 (9 o’clock position, violet nodes in a diamond shape) to be centered around our participants’ wish of being desired in the post-juvenile age. In the interaction of all nodes, the community represents a mature woman with big breasts that is attractive and much sought after by men.

Community 8 (approx. 11 o’clock position, rose nodes in a circle) is about orgiastic and impersonal sexuality and centers around fleeting encounters and orgies with various sex partners. What is noteworthy is that the fantasies seem much more diverse than the actual behavior.

Regarding RQ2 for the female network, we can state the same as for the male network: It was possible to detect meaningful communities of reciprocally interacting sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use of the same style of sexuality. Again, one should bear in mind that due to the exclusion of some items, not all corresponding sexual fantasies, behaviors, and types of pornography have corresponding elements in the communities.

Discussion

We asked if pornography use, sexual behavior, and fantasies could be modeled in a network (RQ 1). Additionally, we asked if communities of reciprocally interacting sexual fantasies, sexual behavior, and pornography use exist in these networks (RQ 2).

Regarding RQ1, networks exist that subsume the assessed sexuality in our sample. In line with previous studies (e.g., Hald & Štulhofer, Citation2016; Martyniuk & Dekker, Citation2018; Price et al., Citation2016), men and women are different in terms of the frequency of pornography use but also differ in the content of their networks. The network’s heterogeneity indicates sex/gender-specific differences in how sexuality is lived. These differences are not only caused by different behavioral or usage frequencies (e.g., Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010) but account for qualitative differences in the sexuality of men and women. In this study, we did not align toward a cultural (e.g., Eagly & Wood, Citation2012) or evolutionary (e.g., Buss & Schmitt, Citation1993) explanation approach for these differences and made no predictions regarding them. However, a key message from the network’s heterogeneity might be that univariate differences in sexuality might often be small (Petersen & Hyde, Citation2010), but these single differences affect a larger behavioral structure which causes, in its sum, completely different outcomes. Therefore, a more multivariate perspective regarding sex/gender should be considered in future research about sexuality (e.g., Del Giudice, Citation2022).

Related to RQ 2, men had ten communities of matching sexual fantasies, behavior, and pornography use, and women had eight communities. These communities are established along all three, two, or even one aspect of sexuality. Pornography use can be an integral part of these communities, together with behaviors and fantasies, but it does not have to be like in women’s community 4 in . It centers only around pornography use unrelated to fantasies or behavior. We advanced Hald and Štulhofer’s (Citation2016) results. The authors ran an EFA on pornography use items to see which types of pornography did cluster. Our approach also included fantasy and behavior items and used a superior method compared to an exploratory factor analysis, which appears unsuitable for the often non-normal distributions of pornography use items.

The communities are strongly interrelated. This high degree of community interaction is reflected in many connections between the nodes belonging to one community. However, our analysis shows many connections between nodes belonging to different communities. These interactions between nodes of different communities demonstrate that many detected patterns show interactions with other communities of sexual fantasies, pornography usage reports, and behaviors. This interconnectedness may be caused by basic mental structures (motives, emotions, instincts) that partly influence these relations between communities or by cultivated narrative structures staged in pornographic content (e.g., reciprocal interaction between nodes of fetish and BDSM). Since we assume that pornographic content is the externalization of sexual fantasies in humans, it is most plausible that communities’ interconnections result from human mental nature and (co-evolved) cultivated pornographic narrative structures (Ohler & Nieding, Citation2005). Their reciprocal interactions lead to a structured, complex web of drafts of sexual scripts that is neither completely random nor predetermined in fixed action patterns.

For men and women, the communities we labeled “vanilla” for men (community 9 in ) or orgasm-centered “vanilla” intercourse for women (community 2 in ) did not include any pornography items at all. Additionally, the more extreme forms of sexual behavior (e.g., forms of violent sex) remained exclusively in the domain of fantasy and pornography use without any large-scale occurrence of a (reported) behavior (for instance, community 8 in ). We think these results align with our assumption that pornography use affects sexual fantasies but not behavior to the same extent. The fact that sexual fantasies tend to be more extreme and volatile has been shown in previous research (Joyal et al., Citation2015; Lehmiller, Citation2018; K. M. Williams et al., Citation2009).

Given our theoretical considerations, the cross-sectional nature of our data only allows for a brief snapshot of our assumptions regarding the 3AM, RSM, and CMVC (Ferguson et al., Citation2008; Slater, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020; Wright, Citation2011, Citation2014). The networks show clear interactions. Still, much stronger longitudinal data would be necessary to test the assumption that pornography use plays a role in a reinforcing spiral process and that interaction occurs over time between sexual fantasies, pornography use, and sexual behavior. However, the reported pornography use very often matched up with the fantasies and behavior in our detected communities well, which is in line with the 3AM and the RSM. From a mere 3AM perspective, one could interpret a rumination of pornography use and fantasies. Regarding the RSM, media use complements a user’s behavior, beliefs, and attitudes. Including the CMVC, we see “escapist” handling of fictional media messages or fantasies. These findings contradict a mandatory behavior-causing effect, which is in line with the basic assumptions of the CMCV (Ferguson et al., Citation2008). Furthermore, the variables in the network affect each other as we expected.

Having mapped out crucial parts of the sexuality of a large and diverse German sample, the result that appears problematic to us from a health policy point of view is that many women seem to put themselves under pressure to orgasm during intercourse. If they do not, this pressure may accompany a related feeling of shame (see also: Lavie-Ajayi & Joffe, Citation2009). This finding made us pause and think about problematic sexual scripts (Gagnon & Simon, Citation2017) and how strongly some participants seem to have internalized these. However, not a single assessed variable about pornography use was related to this phenomenon.

Limitations

We tried to obtain the best grasp on our arguments with the data available. This study was exploratory by nature, but we are the first to use a network approach to map the relations between human sexual fantasies, behavior, and pornography use. Still, it was limited in evaluating the actual theoretical reasoning. For instance, the Sexual Behavior Sequence (Byrne, Citation1976) would describe pornography use as some vent where unfulfilled sexual desires are lived out only in (externalized) thought. Before data collection, we did not assume pornography could be used this way. However, if pornography use would indeed be a vent for unfulfilled desires, we would assume that there should be close to no matching behavior items in our communities where pornography use is included, which is not the case. Still, it is arguable if assessed pornography use and behavior items matched indeed enough in participants’ interpretation to rule out this conclusion.

Because we surveyed the use of pornographic movies only, our results cannot be applied to other distribution channels for pornography. This exclusive focus is a limitation of scope and constrains the transferability of our results to video-based pornography only.

Another limitation of this study was the lack of assessment of covariates for pornography use, for instance, sexual desire or sexual sensation seeking (e.g., Esplin et al., Citation2021), whose potential influence on the networks should be put greater emphasis on in future research.

Furthermore, the use of a convenience sample is problematic. Though our participants had a comparably diverse educational background, our data had limitations in generalizability. Moreover, the questionnaire method is prone to a social desirability bias, especially when applied to porn research (Kohut et al., Citation2020; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018; Willoughby & Busby, Citation2016). However, recent findings of von Andrian-Werburg et al. (Citation2022) suggest that major findings of pornography research can be replicated with web tracking data. At least in Germany, social desirability appears not to be a considerable issue in questionnaire-based research about sexuality. Our results show that “socially undesirable” topics like being ashamed due to a (self-perceived) lack of sexual functioning because of not having an orgasm during intercourse appeared in the female network. Furthermore, comparing men’s and women’s networks showed that the communities matched each other well.

Despite our efforts to control for skewed distributions and the ordinal nature of the TOP and SFQ data (Hald & Štulhofer, Citation2016; Wilson, Citation1988, Citation2010), methodological biases remain. The items used to measure fantasy and behavior were assessed with the same labels. This considerable similarity may cause some artificial relations. Furthermore, we cannot assess the whole variety of human sexuality and therefore cannot rule out that some unassessed pornographic content or sexual fantasy and behavior might exist that would have been detrimental to our networks. However, many items in both the SFQ and TOP already yielded extremely skewed distributions because their labels applied only to very few participants.

Study Implications

In sum, our networks provide a snapshot that allows the assumption that pornography use is in reciprocal relations with a user’s fantasies and behavior. Different communities are detectable that seem to be in line with common assumptions about ways to engage in sexuality (e.g., Vanilla, BDSM, Fetishism). Pornography use plays a role in some of these communities. However, the assessed types more strongly affect the more “uncommon” communities and are no part of mainstream sexuality. The presented analysis can only be the first step toward a methodologically sound cartography of the interactions between pornography use and human sexual fantasy and behavior. In future research, longitudinal data are urgently needed, ideally without the possibility of a social desirability bias (e.g., longitudinal web-tracking data). Furthermore, the next step should include the assessment of vulnerabilities (Ingram & Luxton, Citation2005) that might be intertwined with the adverse effects of pornography use.

Despite these limitations, we think a good starting point is detailed cartography when the aim is to sail through tricky waters. The explored landscape of communities can be read as empirical sedimentation of one’s sexual identity produced by self-reinforcing spirals (RSM; Slater, Citation2015; Slater et al., Citation2020), like footsteps in the sand, as a snapshot of rumination processes as described by Wright (Citation2011, Citation2014) or as a cue about potential (unassessed) mediator variables as suggested by Ferguson et al. (Citation2008). Moreover, hypothesis-driven research on the matter is urgently needed.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (376.5 KB)Acknowledgments

We would like to thank our colleague Dr. Michael Brill for critically reading the manuscript’s draft and for his well-reasoned comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2023.2170964.

References

- BBC. (2020, May 18). New data shows BBC is the world’s most visited news site. BBC Media Centre. https://www.bbc.co.uk/mediacentre/worldnews/2020/worlds-most-visited-news-site

- Borsboom, D., & Cramer, A. O. (2013). Network analysis: An integrative approach to the structure of psychopathology. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9(1), 91–121. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185608

- Briganti, G., Kempenaers, C., Braun, S., Fried, E. I., & Linkowski, P. (2018). Network analysis of empathy items from the interpersonal reactivity index in 1973 young adults. Psychiatry Research, 265, 87–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2018.03.082

- Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual strategies theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.100.2.204

- Byrne, D. (1976). Social psychology and the study of sexual behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 3(1), 3–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616727600300102

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Erlbaum.

- Costantini, G., Richetin, J., Preti, E., Casini, E., Epskamp, S., & Perugini, M. (2019). Stability and variability of personality networks: A tutorial on recent developments in network psychometrics. Personality and Individual Differences, 136(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.011

- Csardi, G., & Nepusz, T. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research. InterJournal, Complex Systems, 1695(5), 1–9. https://igraph.org

- Del Giudice, M. (2022). Measuring sex differences and similarities. In D. P. VanderLaan & W. I. Wong (Eds.), Gender and sexuality development: Contemporary theory and research (pp. 1–38). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-84273-4_1

- Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. (2012). Social role theory. In P. Van Lange, A. Kruglanski, & E. Higgins (Eds.), Handbook of theories of social psychology (pp. 458–476). Sage Publications Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446249222.n49

- Epskamp, S., Borsboom, D., & Fried, E. (2018). Estimating psychological networks and their accuracy: A tutorial paper. Behavior Research Methods, 50(1), 195–212. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0862-1

- Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Qgraph: Network visualizations of relationships in psychometric data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04

- Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

- Epskamp, S., Rhemtulla, M., & Borsboom, D. (2017). Generalized network psychometrics: Combining network and latent variable models. Psychometrika, 82(4), 904–927. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11336-017-9557-x

- Esplin, C. R., Hatch, H. D., Hatch, S. G., Braithwaite, S. R., & Deichman, C. L. (2021). How are pornography and sexual sensation seeking related? Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681994.2021.1937977

- Ferguson, C. J., Rueda, S. M., Cruz, A. M., Ferguson, D. E., Fritz, S., & Smith, S. M. (2008). Violent video games and aggression: Causal relationship or byproduct of family violence and intrinsic violence motivation? Criminal Justice and Behavior, 35(3), 311–332. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854807311719

- Fisher, W. A., & Barak, A. (2001). Internet pornography: A social psychological perspective on internet sexuality. The Journal of Sex Research, 38(4), 312–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490109552102

- Fortunato, S. (2010). Community detection in graphs. Physics Reports, 486(3–5), 75–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.physrep.2009.11.002

- Gagnon, J. H., & Simon, W. (2017). Sexual conduct. The social sources of human sexuality. Routledge.

- Greaves, L. M., Barlow, F. K., Lee, C. H., Matika, C. M., Wang, W., Lindsay, C.-J., Case, C. J., Sengupta, N. K., Huang, Y., Cowie, L. J., Stronge, S., Storey, M., De Souza, L., Manuela, S., Hammond, M. D., Milojev, P., Townrow, C. S., Muriwai, E., Satherley, N., … Sibley, C. G. (2017). The diversity and prevalence of sexual orientation self-labels in a New Zealand national sample. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 46(5), 1325–1336. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-016-0857-5

- Grubbs, J. B., & Kraus, S. W. (2021). Pornography use and psychological science. A call for consideration. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 30(1), 68–75. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721420979594

- Hald, G. M., & Mulya, T. W. (2013). Pornography consumption and non-marital sexual behaviour in a sample of young Indonesian university students. Culture, Health & Sexuality, 15(8), 981–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2013.802013

- Hald, G. M., & Štulhofer, A. (2016). What types of pornography do people use and do they cluster? Assessing types and categories of pornography consumption in a large-scale online sample. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(7), 849–859. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1065953

- Ingram, R. E., & Luxton, D. D. (2005). Vulnerability-stress models. In B. L. Hankin & J. R. Z. Abela (Eds.), Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective (pp. 32–46). Sage.

- Joyal, C. C., Cossette, A., & Lapierre, V. (2015). What exactly is an unusual sexual fantasy? Journal of Sexual Medicine, 12(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsm.12734

- Kohut, T., Balzarini, R. N., Fisher, W. A., Grubbs, J. B., Campbell, L., & Prause, N. (2020). Surveying pornography use: A shaky science resting on poor measurement foundations. The Journal of Sex Research, 57(6), 722–742. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2019.1695244

- Lavie-Ajayi, M., & Joffe, H. (2009). Social representations of female orgasm. Journal of Health Psychology, 14(1), 98–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105308097950

- Lehmiller, J. J. (2017). The psychology of human sexuality. Wiley Blackwell.

- Lehmiller, J. J. (2018). Tell me what you want. Da Capo Press.

- Lippa, R. A. (2009). Sex differences in sex drive, sociosexuality, and height across 53 nations: Testing evolutionary and social structural theories. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 38(5), 631–651. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-007-9242-8

- Martyniuk, U., & Dekker, A. (2018). Adult pornography use in Germany: Results of a pilot study. Zeitschrift für Sexualforschung, 31(3), 237–249. https://doi.org/10.1055/a-0664-4441

- Newman, M. (2018). Networks: An introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Ohler, P., & Nieding, G. (2005). Sexual selection, evolution of play and entertainment. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology, 3(2), 141–157. https://doi.org/10.1556/jcep.3.2005.2.3

- Petersen, J. L., & Hyde, J. S. (2010). A meta-analytic review of research on gender differences in sexuality, 1993–2007. Psychological Bulletin, 136(1), 21–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017504

- Pornhub Insights. (2021, April 8). The pornhub tech review. Pornhub Insights. https://www.pornhub.com/insights/tech-review

- Price, J., Patterson, R., Regnerus, M., & Walley, J. (2016). How much more XXX is generation X consuming? Evidence of changing attitudes and behaviors related to pornography since 1973. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(1), 12–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2014.1003773

- Rasmussen, K. R., Grubbs, J. B., Pargament, K. I., & Exline, J. J. (2018). Social desirability bias in pornography-related self-reports: The role of religion. The Journal of Sex Research, 55(3), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2017.1399196

- R Core Team. (2020). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing. https://www.R-project.org/

- Rodriguez, M., Aalbers, G., & McNally, R. J. (2022). Idiographic network models of social media use and depression symptoms. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 46(1), 124–132. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10608-021-10236-2

- Schmidt, R. A., & Voss, B. L. (2000). Archaeologies of sexuality: An introduction. Routledge.

- Shokeir, A. A., & Hussein, M. I. (2004). Sexual life in pharaonic Egypt: Towards a urological view. International Journal of Impotence Research, 16(5), 385–388. https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijir.3901195

- Slater, M. D. (2007). Reinforcing spirals: The mutual influence of media selectivity and media effects and their impact on individual behavior and social identity. Communication Theory, 17(3), 281–303. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2885.2007.00296.x

- Slater, M. D. (2015). Reinforcing spirals model. Conceptualizing the relationship between media content exposure and the development and maintenance of attitudes. Media Psychology, 18(3), 370–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2014.897236

- Slater, M. D., Shehata, A., & Strömbäck, J. (2020). Reinforcing spirals model. In J. van den Bulck, D. Ewoldsen, M.-L. Mares, & E. Scharrer (Eds.), The international encyclopedia of media psychology (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119011071.iemp0134

- von Andrian-Werburg, M. T. P., Siegers, P., & Breuer, J. (2022). A reevaluation of online pornography use in Germany using a combination of web tracking and survey data. PsyArxiv. https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/ehqgv

- Williams, K. M., Cooper, B. S., Howell, T. M., Yuille, J. C., & Paulhus, D. L. (2009). Inferring sexually deviant behavior from corresponding fantasies: The role of personality and pornography consumption. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 36(2), 198–222. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854808327277

- Williams, D. R., Rhemtulla, M., Wysocki, A. C., & Rast, P. (2019). On nonregularized estimation of psychological networks. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 54(5), 719–750. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1575716

- Willoughby, B. J., & Busby, D. M. (2016). In the eye of the beholder: Exploring variations in the perceptions of pornography. The Journal of Sex Research, 53(6), 678–688. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2015.1013601

- Wilson, G. D. (1988). Measurement of sex fantasy. Sexual and Marital Therapy, 3(1), 45–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/02674658808407692

- Wilson, G. D. (2010). The sex fantasy questionnaire: An update. Sexual and Relationship Therapy, 25(1), 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681990903505799

- Wright, P. J. (2011). Mass media effects on youth sexual behavior assessing the claim for causality. Annals of the International Communication Association, 35(1), 343–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/23808985.2011.11679121

- Wright, P. J. (2014). Pornography and the sexual socialization of children: Current knowledge and a theoretical future. Journal of Children and Media, 8(3), 305–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2014.923606

- Wright, P. J., Paul, B., & Herbenick, D. (2021). Preliminary insights from a U.S. probability sample on adolescents’ pornography exposure, media psychology, and sexual aggression. Journal of Health Communication, 26(1), 39–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2021.1887980

- Yang, Z., Algesheimer, R., & Tessone, C. (2016). A comparative analysis of community detection algorithms on artificial networks. Scientific Reports, 6(1), 30750. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep30750