In the 1890 manifesto of painting Définition du néo-traditionnisme, Maurice Denis compared those paintings he held in high esteem with »haute tapisserie«.Footnote 1 The modernist theory of the »carpet paradigm« notwithstanding, it was first and foremost tapestry – not carpets – that functioned as a paradigm for the Nabis, a group of painters working in Paris during the last decade of the nineteenth century, of which Maurice Denis and Paul Sérusier were the theoretical foremen. In 1894, the Nabi Edouard Vuillard noted in his journal how around 1890, Denis and Sérusier had taught their fellow artists that a painting should simply be a blow-up of a tapestry fragment.Footnote 2 Besides the formal aspect of this model function, concerning the juxtaposition of colours and short, interrupted brushstrokes in a two-dimensional field, for Denis and Sérusier, the tapestry paradigm also included values related to narrative and content. With Charles Baudelaire, they saw the medieval tapestries that were rediscovered in France from Romanticism onwards as expressing the »great visions« of Gothic Catholicism.Footnote 3 In the context of the late nineteenth-century Gothic revival, the frequent textile metaphors in Symbolist art criticism are to be read as referring to both formal and narrative aspects. In 1892, for example, Georges-Albert Aurier described Sérusier's figurative, primitivist Breton paintings as »magnificent tapestries of high-warp«,Footnote 4 a comment betraying a general familiarity in the circle of the Nabis both with the craft of tapestry weaving and with its aesthetic and poetic medievalist, »neotraditionist« connotations.

However, only formal and material aspects became central to later twentieth-century modernist comparisons between paintings and the textile arts. They are the focal points of Joseph Masheck's 1976 prolegomena to a theory of the »carpet paradigm«.Footnote 5 Departing from Clement Greenberg's ideas on medium-specificity, Masheck forwarded the idea that the emphasis on flatness in modernist painting can be traced back to the final decades of the nineteenth century, when decorative values entered painting from the realm of the applied arts and design theory. While it is true that texture and surface are emphasised in post-impressionist painting, Masheck's retroactive motivation of late modernism's pictorial flatness through the decorative leaves aside all narrative, poetic and religious aspects of the nineteenth-century tapestry paradigm. It is the aim of this article to enlarge the theoretical figure of the carpet paradigm, by looking at the ways in which a decorative pictorial vocabulary has been thought to create meaning in art. This is particularly relevant for Symbolist painting, itself theorised as a visual form of language. Paul Gauguin, the Nabis’ mentor, had stated that ideas and feelings derived from nature should be communicated through simple forms. His synthetic, non-mimetic pictorial vocabulary of flattened and simplified forms, distinct (contour) lines and pure colours was often called »decorative«. The critic Georges-Albert Aurier, probably through contact with Gauguin's disciple Sérusier, developed Gauguin's ideas on decorative painting into a neoplatonic system. He identified line, colour and form as »directly signifying elements« of the pictorial sign language.Footnote 6 The artwork itself was theorised as a symbol, that is, as a complex image expressing ideas beyond the literal objects depicted. In semiotic terms, the signified of the Symbolist symbol is constitutively elusive – and most often situated in a metaphysical realm. Theorised in the nineteenth century as pertaining to a formal language, the decorative ornament appealed to Symbolists precisely for its suggestive potential and for the open-ended array of references it implies.Footnote 7 Equally rejecting mimetic representation (especially in its contemporaneous form of Naturalism), the Symbolist poet and theoretician Stéphane Mallarmé habitually mobilised decorative images in his poetry.Footnote 8

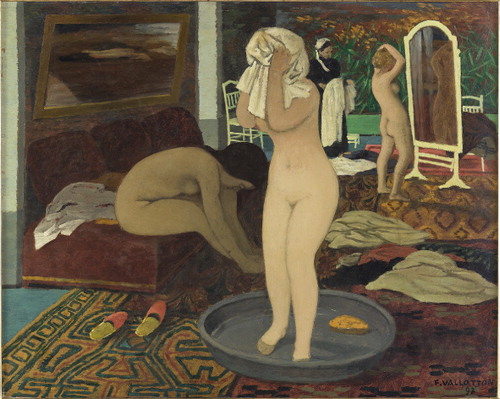

Like his fellow Nabis, the painter and printmaker Félix Vallotton depicted several »decorative« interiors, among which, notably was, Femmes à leur toilette (). This painting, in which carpets and rugs figure prominently, brings together questions of form and meaning in the decorative pictorial sign language. As a »symbol«, the objective of this and similar paintings could not be the depiction of a realist scene or story. Nevertheless, as shifting and elusive signifiers, the depicted ornamental rugs and carpets play with the idea of narrativity in painting. In his woodcuts from the early 1890s, Vallotton, an illustrator of works of fiction and journals, developed different strategies of story-telling. In his subsequent Nabi painting Femmes à leur toilette (1897), depicting several figures in a carpeted interior, the mobilisation of a distinctly decorative type of narrativity, in which the creation of a definitive and final meaning is continually thwarted, begs for a comparison with a contemporaneous work of fiction: Henry James's novella The Figure in the Carpet, first published in 1896. Both in the novella and in the painting, narrativity is not treated as a thing or a class, but, in line with post-classical narratology, as a property or a set of properties inspiring a narrative response in an audience.Footnote 9

Vallotton between Nabis and La Revue blanche

Swiss artist Félix Vallotton, nicknamed »le nabi étranger«, was not a member of the Nabi group from its inception in 1889.Footnote 10 He first exhibited alongside the Nabis in 1893, but his ties with especially Vuillard, Pierre Bonnard and Kerr-Xavier Roussel were affirmed from 1894 onwards, when all four of them became so closely involved with the Symbolist journal La Revue blanche that, together with Toulouse-Lautrec and a few others, they were later dubbed »the painters of the Revue blanche«.Footnote 11 By 1894, Vallotton's black-and-white woodcut prints enjoyed a considerable reputation in Symbolist circles ( and ). Arriving in the group at a later time, he escaped the direct pictorial and theoretical influence of Denis and Sérusier, who disseminated their lessons at the beginning of the 1890s during weekly Nabi meetings. These lessons were based on Sérusier's understanding of the painting of Gauguin and were built upon the aesthetics put forth around 1889 by the Synthetists, who further included Vincent van Gogh and Louis Anquetin. Vallotton, for his part, rather absorbed Nabi aesthetics visually and through discussions with less dogmatically inclined members of the original group. Thus the honorary title »Nabi«, the Hebrew word for prophet, in his case implied, first, a shared aesthetics, visible in his painting from 1893 onwards. Only secondly did it refer to the membership of a group that was by then already slowly disintegrating and fusing into the larger and amorphous group of Symbolist painters. A group portrait of Vallotton and his closest painterly allies from 1902 includes only three of the former Nabis: Vuillard, Bonnard and Roussel, and furthermore Charles Cottet.Footnote 12 At the turn of the twentieth century, Maurice Denis too noted a schism among the Nabis and identified two subgroups.Footnote 13 On the one side, he placed Sérusier, Paul-Elie Ranson and himself, and on the other side, there were Vuillard, Bonnard and Vallotton – and to them must be added Roussel. Among the differences Denis noted was his own subgroup's focus on bright and unmixed colours, a neat design of figures and large formats, whereas he saw the other subgroup producing mostly smaller paintings suitable for sparsely lit domestic interiors. Although several of Denis's categories are debatable, Vuillard, Bonnard and Vallotton indeed often depicted small indoor scenes, into which chiaroscuro was reintroduced – which had been banned from vanguard painting since Impressionism.

Photo: MAH-CdAG.

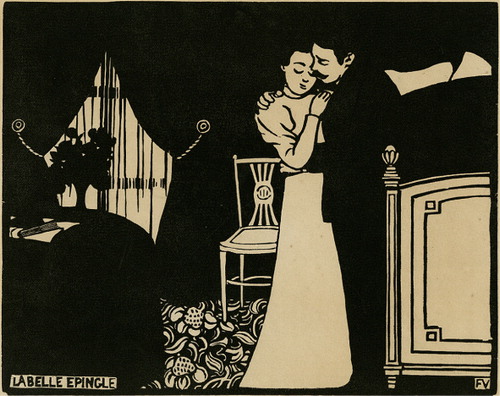

Having started out as a fairly naturalistic painter, the bulk of Vallotton's artistic production between 1892 and 1896 is made up of black-and-white woodcut prints; of a considerable number of woodcut portrait vignettes that later figured as illustrations for Remy De Gourmonts's Book of Masks and of black-and-white book illustrations for authors such as Jules Renard, whose work, like that of many other Naturalists, focused on the exposure of the untruthfulness of bourgeois life. When his woodcuts were coming to their height in the second half of the 1890s, Vallotton gradually returned to painting, abandoning the production of woodcut prints almost entirely in the twentieth century.Footnote 14 During the second half of the fin de siècle, Vallotton's pictorial approach drew heavily on Nabi pictorial aesthetics and Symbolist poetics, as well as on his woodcut experiences, praised by Julius Meier-Graefe for their painterliness.Footnote 15 Significantly, Vallotton's Nabi membership was consecrated in the context of a Symbolist literary journal. At the offices of the Revue blanche, aesthetic discussions were mixed with discussions of poetics under the auspices of »the prince of poets«, Stéphane Mallarmé. The importance of Mallarmé's poetics for the work of Vallotton, Vuillard and Roussel cannot be underestimated. In 1898, a series of 10 woodcut prints entitled Intimacies from 1897 to 1898 were printed by the Revue blanche, and it can be seen as the culmination of Vallotton's artistic involvement with the journal and of his interest in Symbolist narrative strategies.

Symbolist narrativity in the album Intimacies (1897–1898)

The album of 10 prints making up Intimacies depicts a man and a woman acting out various scenes of married or amorous life in domestic interiors ().Footnote 16 While the prints share formal and thematic qualities, the presentation of different scenes in a certain order does not imply the linear unfolding of a story, as in a comic strip or theatre performance. Nonetheless, the imposed sequential reading entails a gradual discovery of the central theme of the series: feminine infidelity. The sequence can thus be understood as comprised of variations on a theme.

Vallotton's interest in the theme of the battle between the sexes is contextualised by fin-de-siècle discourses on the relationship between the sexes, for which the Revue blanche functioned as a regular platform. In the journal's male-centred discussions, as elsewhere, more often than not woman was described as profoundly other to man, be it positively or negatively. In 1896, for example, one critic tried to refute »the old cliché of woman's inferiority« by stating that a considerable labour is necessary for ovulation and reproduction and by citing the »enormous expenditure of protoplasmic energy in the creation of female beauty«, adding further strength to his plea by noting that »all artistic things are very expensive«.Footnote 17 One of the strongest statements of woman's ‘inferiority’ was the Swedish playwright August Strindberg's pamphlet »On the Inferiority of Woman«, published in the Revue blanche in 1895.Footnote 18 Recent studies have nuanced Strindberg's misogyny, but the images of woman in his writings that were introduced in French Symbolist circles were invariably negative. In his play The Father, performed at the Symbolist Théâtre de l’Œuvre in December 1894, the leading female character is a dangerous and manipulative creature. In this play, a married couple fights over the upbringing of their daughter. The wife triumphs, but only after insinuating that her husband might not be the girl's father.Footnote 19 The Nabis were closely involved in the stage and programme decoration of the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, and the only illustrated playbill by Vallotton was that for The Father. Whether or not inspired by his reading of Strindberg, a marked and lifelong misogyny comes to the fore both in Vallotton's personal and in his public writings.Footnote 20

The theme of feminine infidelity was also omnipresent in fin-de-siècle literature, and it is inscribed in a larger »unmasking« trend, prevalent from the 1880s onwards.Footnote 21 Aiming at exposing the lies of bourgeois life and penetrating what is hidden, this branch of literature paralleled late nineteenth-century developments in dynamic psychiatry, the forerunner of psychoanalysis that focused on the hidden dimension of the human psyche and aimed to uncover secret motivations and drives.Footnote 22 Vallotton's series Intimacies presents a visual example of this »unmasking« trend. The title of the series is brilliantly chosen. The word »intimate« has two meanings: first, what is interior and private and, therefore, has a hidden, secretive dimension, and second, a close unison or the most private of interpersonal relationships. Here, too, what is exposed is that it is woman who cheats and woman who triumphs.

With their »attack« on the falseness of bourgeois life, Vallotton's prints parallel the psychologist literary trend not only thematically but also structurally. The plays of both Strindberg and Henrik Ibsen, the preferred playwright of the Théâtre de l’Œuvre, are characterised by a gradual uncovering of a hidden truth, which is in many cases ugly. The fact that this process of gradual revelation and analytical interpretation is simultaneously unfolded for the audience and for the characters on stage makes especially Ibsen's works »exemplary psychological dramas«.Footnote 23 The unmasking project of the Intimacies series is announced in the title or caption of the first print: The Lie. This »lie« of course, refers to the insincerity and mendacity of bourgeois love, acted out in Intimacies in different scenes. Narrative affinities between Vallotton's Intimacies and Strindberg's pessimist literary and theatrical writings have led Eugene Glynn to describe the series as »a Strindbergian study of bourgeois marriage«.Footnote 24 More importantly, Vallotton situated his exposure of the bourgeois lie inside the domestic interior, thus redoubling the notion of the »interior« as the locus of secret, hidden drives. Walter Benjamin was the first to point out the close relationship between the late nineteenth-century carpeted domestic interior and the detective story, also based on the uncovering of hidden clues: textiles and upholstery guard traces of human presence and activity.Footnote 25

Besides literary sources, it has been suggested that a painting now entitled Married Life (ca. 1896, private collection) by Vuillard functioned as a starting point for Vallotton's Intimacies.Footnote 26 In Vuillard's painting, emotional content is conveyed by the expressive use of the formal means of painting, colour, line and form. In Nabi theory, which approached painting as a language of signs, decorative, stylised forms were ascribed the quasi-linguistic potential of conveying meaning, albeit musically – that is, by provoking an emotional reaction on the part of the receiver. In addition to this emphasis on expression through the emancipated, stylised and deformed »material« of painting – to use Denis's terms – Footnote 27 , the distribution of figures and objects in the pictorial space of Married Life contributes to create a dire mood. A marked distance between a man and a woman in an interior, combined with their detuned bodily postures, expresses their emotional distance. Similarly, in Intimacies Vallotton mobilised simplified formal means, figure-poses and decoration to create an emotionally charged domestic scene. As was the habit on the Symbolist stage, for which Vuillard helped devise the lighting plan, Vallotton employed light and dark zones as expressive means. His use of black in particular conveys the idea of a dead-end situation and seems indicative of some menacing, ominous dark force or fate looming over the figures. In several of the prints, the black-and-white contrast calls forth a secretive atmosphere, as the dark zones hamper an immediate grasp of the situation.

Furthermore, the choice and disposition of interior accessories provide us with clues to decode Vallotton's »message« (of feminine infidelity). A narrative use of decoration is especially evident in the one print depicting a carpet, with a design of exotic fruits, flowers and leaves, The Fine Pin (). Leaving aside the voluptuous metaphor of the motifs, they also signal a serious flaw in interior design. Nineteenth-century design reformers argued that because a carpet is the ground from which the furniture rises, it cannot represent anything three-dimensional or unfitting, like a flowerbed.Footnote 28 By deduction, the bourgeoisie is here associated with bad taste, which in turn mirrors the falsity of bourgeois domestic life. The scene that we witness is quite dubious: the exchange of a valuable gift in a bedroom suggests that a woman's love is for sale – or comes with a certain price.

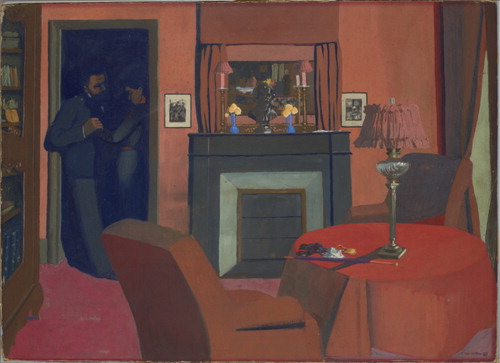

The narrative use of decorative carpets returns in a series of paintings that Vallotton produced in 1897 and 1898 including The Red Room (). These works depict scenes of adulterous love in impersonal bourgeois interiors and are closely associated with the theme and compositions of the Intimacies prints.Footnote 29 In Felix Krämer's analysis, a zigzag stripe on a carpet in one of these paintings functions as a metaphorical boundary line: once the woman entering a gentleman's apartment crosses this line and takes off her coat, she will be on her way to committing adultery.Footnote 30

Photo: Nora Rupp.

As in the interior paintings connected to the album of prints, Vallotton ended the plotless »stories« of Intimacies with the uncovering of a hidden, inner hypocrisy within human psychology. His works do not propose a solution, or, as in other Symbolist works that are more metaphysically oriented, a »deliverance« of the beholder in the aesthetic experience. Thus, Intimacies remains close to the ‘fumiste’ Montmartre attacks on social hypocrisy and to the bourgeois entertainment of Parisian Boulevard theatre, with its predilection for the subject of adultery.Footnote 31 With this dire end point, Vallotton's interiors are indeed related to Strindberg's pessimism and also to the Naturalist aesthetics of a dissection of life (Emile Zola), but now applied to the psyche, as in the psychological novels of Paul Bourget.Footnote 32 However, even if the series Intimacies comes very close to presenting a story, its narrative strategy is characterised primarily by the Symbolist aesthetic notion of suggestion. Formally, this is achieved through the expressive use of line, colour and form, notably the distribution of black and white which both directs and thwarts a narrative interpretation. On the level of the presentation of subject matter, Vallotton's Intimacies thus follow the definition that Mallarmé gave of the symbol's central operational feature, suggestion, in Jules Huret's 1891 Enquête sur les tendances littéraires in an unexpected manner. It is altogether possible to apply the second part of Mallarmé's definition to Vallotton's artistic process of a gradual unveiling of a hidden truth of psychological order:

C'est le parfait usage de ce mystère qui constitue le symbole: évoquer petit à petit un objet pour montrer un état d’âme, ou, inversement, choisir un objet et en dégager un état d’âme, par une série de déchiffrements.Footnote 33

Figures, carpets and decorative narrativity: Vallotton's Femmes à leur toilette (1897)

Juliet Simpson has shown how the strong relationship between image and text in Symbolist aesthetics and poetics centred on decorative precepts.Footnote 34 While Symbolist poets and Mallarmé in particular explored the decorative form, a sign of ambiguity and indeterminacy, as a means of expressing the in-between in poetry, painters like Seurat, Gauguin and the Nabis built their theories of pictorial style and expression through simplified, abstract forms upon theories of the decorative arts.Footnote 35 Since both a decorative form and a decorative use of language imply a certain degree of abstraction, we are at this point reminded of the modernist discourse linking ‘flat’ abstract painting with decorative theories. However, none of these painters would venture into abstraction. Vallotton's Femmes à leur toilette from 1897 () and the painting to which it very likely reacted, Vuillard's Large Interior with Six Figures (), also from 1897, represent figurative scenes.Footnote 36 The significance of Vuillard's painting for the Swiss painter is attested by the fact that it came into his possession in 1897, probably as a gift.Footnote 37 Moreover, Vallotton cited Vuillard's painting twice in his own work: once depicted hanging on a wall in the interior painting Femme en robe violette sous la lampe (1898, private collection) and once partially reflected in a mantelpiece mirror in The Red Room (), which is part of the group of interior paintings related to the Intimacies prints.Footnote 38 Both Vuillard and Vallotton depicted an interior with several figures and an arrangement of carpets on the floor. The carpets not only introduce a plethora of patterns but also a quickly receding perspective, creating the impression of a flattened, decorative picture surface. Vuillard's panoramic composition cleverly stages a sequence of four scenes within a single interior (). From left to right, we see an elderly female figure in conversation with a younger female figure seen from behind; a male figure behind a table absorbed in reading and flanked by a female figure standing behind him; a female figure (the same as the one to the far left?) standing by a door to the back of the room, and finally, to the far right and cut off by the picture frame, a female figure bending over, perhaps rummaging through a drawer of a cabinet outside the picture frame.Footnote 39

While Vallotton's Femmes à leur toilette () also depicts several figures absorbed in different activities in a carpeted interior, the nudity of three of these figures shifts the subject from a domestic interior to a semi-public brothel scene. For a number of years, the painting carried the title Le Gynécée, which was bestowed upon it by the gallery owner Eugène Druet in 1910.Footnote 40 This title situates the painting elsewhere than in the nineteenth-century tradition of orientalist harem paintings: the gynaeceum was the ancient Greek and Roman women's quarters in the house. More significant is the medieval use of the word, where it designated a weaving and spinning house that was often also a brothel. Druet's reading of the carpets as not necessarily referring to the Orient is confirmed by a close inspection of their patterns: with the exception of the one to the front on the left-hand side of the painting, all floor carpets have indeterminate decorative patterns, perhaps vaguely orientalist, but more likely a modern spin-off.Footnote 41 Since it was Nabi practice to paint from memory and not after nature, these patterns could be composite or even wholly imaginary. Their stylistic indeterminacy suggests that rather than to look for narrative »clues« in the patterns, it is the abundance of ornamental carpets and textiles itself that contains »meaning« and contributes to the narrative atmosphere of the presented scene. Even more than in Intimacies, Vallotton's strategies of narrativity here follow the Symbolist mobilisation of the ambiguity of decorative signs.

Photo: MAH-CdAG.

In this painting, even the human figures become mere decorative signs among others. In contrast with the fleshly or psychological allurement of most harem paintings, the self-absorbed postures of Vallotton's nudes, the absence of faces and gazes and the simplified body features frustrate the (male) spectator's engagement with the depicted scene. The imposed voyeurism is far less erotic than that of Degas's bathing scenes, for example. This is in part due to the resistance to tactility in the treatment of the pictorial surface – even if this is one of the rare paintings in which Vallotton tried to emulate Vuillard's »woolly« textile paintings.Footnote 42 Whereas Vuillard treated his figures with the same attention as their surroundings (), the massive brightness of skin tone makes Vallotton's nude in the foreground of the painting stand out against the ornamental ground and the patterned wall. This brightness is accentuated by the white cloth in the hands of the servant, which, on the picture's surface, seems to almost caress the central bather's back. If we let our eyes follow the direction from the bright foreground figure to the servant's white cloth, the next stop is the illuminated back of the fair-haired nude examining herself in the mirror. The upward viewing direction from left to right is further stimulated by the disposition and patterns of the carpets and is pointed out by the pair of slippers in the foreground of the painting. But once our eyes arrive at the nude in the background of the scene, they are directed back to the frontal nude in two ways. The first is through the mirror, which is turned towards the nude in the tub, although it does not show her – and neither does it give us a good look at the bust of the fair-haired nude. The second redirection of our gaze is provoked by the colour distribution across the pictorial surface: if we try and follow the path of brightly coloured patches laid out for us in the painting, the next bright objects we find after the backside of the mirrored nude are two discarded cloths on the carpets, painted in the same hues as the skin of the bathers. Our eyes thus follow a clockwise circular movement through the pictorial space, which could include the seated nude to the left-hand side of the painting, only to be frustratingly quickly brought back to the foreground that is dominated by the upright nude in the tub. And while the spectator is placed up close to her, even looking slightly down in a voyeuristic manner so that the ceiling is cut off from view, there is not much sensory satisfaction to be had.

With the exception of the enticingly fleshy pink nipple of the standing bather, the painting's resistance to sensuality is entirely in line with the Nabi rejection of academism and Naturalism in painting. In an anecdote recounted in the Définition du néo-traditionnisme, Maurice Denis singled out the female body as a topos in the battle between nineteenth-century Academic, mimetic painting and Symbolist, decorative painting:

À l'un des jeunes néo-traditionnistes, alors à l’École, à propos d'une femme très blanche qu'il avait peinte, où la lumière se jouait en frissons d'arc-en-ciel, – et c’était cette couleur qui l'intéressait, il l'avait cherchée toute une semaine, – un maître moderne disait, que »c’était pas nature, vous ne coucheriez pas avec cette femme-là!«Footnote 43

Vallotton's interest in carpets could have something to do with Holbein, whose frequent depictions of a specific type of Ottoman carpets gave rise to the art-historical term »Holbein carpet«. A lesson learned both from Vuillard and from Holbein is the compositional use of the carpets’ geometric patterns as an element of perspective. However, the combination of a Vuillardesque decorative and material textile quality of the pictorial surface, on the one hand, and simplified female figures recalling especially Maurice Denis's early Nabi paintings, on the other hand, apparently did not provide Vallotton with a new direction in painting. Femmes à leur toilette rather represents a »Böcklinian« experimental step in Vallotton's search for a pictorial style that would reflect Nabi aesthetics: in his 1897 review of Böcklin's retrospective, Vallotton singled out the high artistic aims and tenacity of the »tormented« Böcklin who »experiments, tries, starts over, makes mistakes and finally triumphs, but with a singular triumph, which is not decisive and must leave intimate fears in the depths of this superior soul«.Footnote 48

It is well known that Vallotton had literary aspirations.Footnote 49 The Symbolist literary milieu provided him with an incentive to integrate a certain type of narrativity in his visual work. Shortly after or even during the creation of this painting, he found the perfect combination between Symbolist poetics and his interest in psychology, culminating in the Intimacies album and the ensuing group of interior paintings ( and ). The clear-cut style of these works mirrors the sharpness of their thematic content, thus creating a harmonious whole. The »story« or theme of the painting Femmes à leur toilette () is much more confused, due to the many open-ended references in the work. It is particularly the use of ornamental carpets that contributes to the painting's adherence to Symbolist poetics.

In the aesthetic context of decorative abstraction, informing both Symbolist painting and literature, the ornamental carpet functioned as a paradigm for painting in the same way as figurative medieval tapestry had done. In spite of later modernist theories emphasising the transposition of decorative flatness and physicality from the carpet into painting, ornamental carpets, again, functioned as a model for narrativity – albeit for a decorative narrativity, in which the signifier generates an excess of signification. The abundance of patterned carpets and textiles in Femmes à leur toilette is the clearest sign of the Symbolist project of the painting, and it is embedded in and reinforced by several other Symbolist, decorative narrative strategies that generate a »meaning« that is unstable, ambiguous and indeterminate: repetition, framing and mirroring.

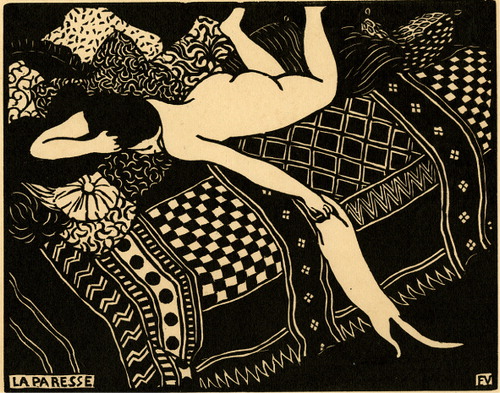

According to Nabi aesthetics, the painting does not represent a realistic brothel scene, but a dream-like »pure ornamental fiction«, to borrow a key-phrase describing the stage sets of Symbolist theatre.Footnote 50 The fictionality of the depicted scene is emphasised by the patches of plain blue floor underneath the carpets, as well as by the apparition of unornamented grey and white walls or beams demarcating the left-hand wall of the room, that is thus revealed to be a mere décor. The walls of the room are carpeted or painted with motifs that recall outdoor scenes. The introduction of other framed fictional spaces within the picture frame can be interpreted as a mise en abyme of the idea of the painting as a window. But the most obvious Symbolist decorative strategy is the ironic play with the Symbolist practise of seeing mirrors as reflectors of the noumenal: in Symbolist art and literature, mirrors reflect not the human body but the human soul, understood as a portal to a transcendent realm. A similar »truth« cannot be revealed by the mirrors in this painting, since the figures they mirror are themselves decorative and fictional. It is rather the fictionality of the artwork itself that is revealed by the unexpected reflections in the mirrors. First, the opacity of the reflection of the nude in the background in the standing mirror could signal a preference for the dream or memory version of the more dangerous and banal real-life sexual encounter that is evoked by the depicted scene. The second mirror, hanging on the wall above the seated nude, depicts an even more confusing scene that is difficult to make out but does not seem to reflect the pictorial space of the bathers. I would like to suggest that the shapes hinted at in this mirror evoke a puppet-like or dead figure lying on its back, with its legs pointing towards the beholder. This pictorial device was again used one year later in The Red Room (). In Felix Krämer's analysis, the glove, wallet and handkerchief lying on the table in this painting together suggest the shape of a kobold-like figure.Footnote 51 In addition, we may note that if the two dehumanised mirror reflections count as figures, Vallotton actually depicted six figures in an interior – inter-iconically referring to Vuillard's Large Interior with Six Figures (). It is even possible to include the emphasis on flatness of the picture's surface in this enumeration of decorative narrative strategies, for it too points to the artwork's fictionality. A print entitled La Paresse (), depicting a nude and a cat splayed on a bed with a patterned bedspread, shows how Vallotton experimented during this time with the creation of an impression of pictorial flatness by an accelerated recession of the perspectival lines in the patterns of textiles. Of course, Maurice Denis had opened his 1890 Définition du néo-traditionnisme with a now famous phrase that equally insists on the fictionality and self-referentiality of the picture surface:

Se rappeler qu'un tableau – avant d’être un cheval de bataille, une femme nue, ou quelconque anecdote – est essentiellement une surface plane recouverte de couleurs en un certain ordre assemblées.Footnote 52

The Figure in/on the Carpet

The painterly path that Vallotton chose directly after Femmes à leur toilette and to which he more or less stuck throughout his career was based on the harmonious or confronting juxtaposition of large fields of colour, a classicist use of line and simplified figures that are more monumental, more harsh and also slightly more realist than the decorative nudes in his »gynaeceum«.Footnote 53 Vallotton transposed his woodcut technique to painting to create an idiosyncratic type of stylised classicism to which many critics, failing to see its Nabi roots, have referred as deficient or shortcoming.Footnote 54 However, in his artistic dialogue with Vuillard around 1897, Vallotton approached his fellow Nabi's pictorial exploration of the relationships between painting and textiles. But while this research amounted to a profound interest in surface tactility in the painting of Vuillard, Vallotton's mobilisation of the decorative focused on its narrative potential. In Femmes à leur toilette, the combination of carpets and the archetypal human figure, the nude, here »abstracted« from nature to become a pictorial sign, raises the question of the relationship between »figure« and carpet. It is a revealing coincidence that Henry James's novella The Figure in the Carpet was printed in 1896 in a well-known international journal in the circle of La Revue blanche: Cosmopolis.Footnote 55 It was in this same trilingual platform that Mallarmé first published his Un coup de dés jamais n'abolira au hasard.Footnote 56 The structural affinities between Vallotton's painting and James's novella are striking. The Figure in the Carpet revolves around the quest of a literary critic to discover the hidden »secret« in the work of a famous novelist. The novella gives form to the aforementioned artistic concern typical for the turn of the nineteenth century: the desire to unravel a hidden truth, to unlock the »secret« of an artwork. But while Naturalist aesthetics prescribed a »scientific« dissection of an object in order to uncover its final »truth«, the fin-de-siècle artist's »secret« was not of a technical or a material order.Footnote 57 »Is it something in the style or something in the thought? An element of form or an element of feeling?«, James's critic desperately asks the novelist.Footnote 58 The critic compares this supposed »secret« driving the oeuvre of the novelist to a »complex figure in a Persian carpet« and he tries in vain to identify and unravel it.Footnote 59 But as in Vallotton's painting Femmes à leur toilette, the figures in, as well as in Vallotton's case those on the carpet, cannot be deciphered as allegorical signs with codified meanings. Neither do they function as the indexical clues of the detective story, which point to events from daily reality. Rather, both James's and Vallotton's insistence on the decorative and its signifying apparatus of suggestion is part of a strategy that resists traditional narrative and exposes the narrative impulse of the reader/beholder. In his interpretation of The Figure in the Carpet, Wolfgang Iser argued that the novella's key message is that if meaning is perceived as something that »can be subtracted from the work«, then »the very heart of the work [...] can be lifted out of the text, [and] the work is then used up – through interpretation«.Footnote 60 In The Figure in the Carpet, according to Iser, this process is made apparent to the reader, who »gradually realizes the inadequacy of the perspective offered him«.Footnote 61 Similarly, Vallotton used decorative strategies of narrativity to thwart a mimetic interpretation and to emphasise painting's fictionality, by making the beholder aware of his or her desire to discover a narrative meaning. Both in the novella and in the painting, the exposure of the beholder's mimetic impulse opens the way for a collaborative creation of meaning.Footnote 62 The decorative sign, producing complexity, excess and ambiguity, was thus perfectly suitable for an aesthetics whose ultimate aim was to transcend logos and to leave a significant part of responsive engagement to the beholder in the process of creating meaning in art.Footnote 63

Summary

In the second half of the 1890s, Nabi artist Félix Vallotton made a definitive transition from woodcut prints to painting. The carpets and wall hangings depicted in his interior paintings from this transitional phase are to be read as decorative, abstract signs in a Symbolist pictorial language of signs. Vallotton's use of carpets parallelled not only his fellow Nabi Edouard Vuillard's interest in textiles as a paradigm for painting, but, more importantly, the Symbolist exploration of a specific type of narrativity by mobilising the abstract potential of the decorative. Vallotton's narrative strategies can be compared with those employed by Henry James in his contemporaneous novella »The Figure in the Carpet«.

Notes

1. Maurice Denis, »Définition du Néo-traditionnisme«, Art et Critique, No 65, 23 August 1890, pp. 540–542, and No 66, 30 August 1890, pp. 556–558. Reprinted in Le Ciel et l'Arcadie, Jean-Paul Bouillon (ed.), Hermann, Paris, 1993, p. 21.

2. Vuillard, Carnets, 1894, quoted in Françoise Alexandre, »Édouard Vuillard. Carnets intimes. Édition critique«, diss., Université de Paris VIII, Paris, 1998, p. 350.

3. Charles Baudelaire, »Richard Wagner et Tannhaüser à Paris«, in Claude Pichois (ed.), Œuvres complètes (Vol. II), Gallimard, Paris, 1976, p. 791.

4. Georges-Albert Aurier, »Deuxième Exposition des Peintres Impressionnistes et Symbolistes«, Mercure de France, No 31, Vol 5, 1892, p. 262.

5. Joseph Masheck, »The Carpet Paradigm. Critical Prolegomena to a Theory of Flatness«, Arts Magazine, Vol 51, No 1, 1976, pp. 82–109. The early Nabi »tapestry paradigm« differs from Joseph Masheck's »carpet paradigm« for painting in two obvious ways: first, tapestry is destined to ornate walls, like painting but unlike carpets, and second and more importantly, carpets have decorative, even abstract designs, whereas tapestry is characterised by figurative representation.

6. Georges-Albert Aurier, »Le Symbolisme en peinture: Paul Gauguin«, Mercure de France, Vol. 2, No. 15, 1891, pp. 155–165.

7. Especially Charles Blanc's Grammaire des arts décoratifs, first published in Paris in 1882, was a primary source for many Symbolist painters, among whom Paul Seurat and Paul Gauguin.

8. See Juliet Simpson, »Symbolist Aesthetics and the Decorative Image/Text«, French Forum, No 2, Vol. 25, 2000, pp. 177–204, here pp. 177–181.

9. See Marie-Laure Ryan, »On the Theoretical Foundations of Transmedial Narratology«, in J. Ch. Meister (ed.), Narratology beyond Literary Criticism: Mediality, Disciplinarity, Berlin, De Gruyter, pp. 1–23. For a general overview of theories of narrativity, see H. Porter Abbott, »Narrativity«, in The Living Handbook of Narratology, Hamburg University Press, wiki.sub.uni-hamburg.de [last accessed 17 March 2014].

10. See Claire Frèches-Thory, »Le nabi étranger«, in Le Très singulier Vallotton, exh. cat., RMN, Paris, 2001, pp. 34–47. See also Katia Poletti, »Le regard de Vallotton critique d'art sur ses contemporains«, in Rudolf Koella and Katia Poletti (eds.), Félix Vallotton critique d'art, 5 Continents, Milan, 2012, pp. 206–208.

11. Artists of La Revue blanche: Bonnard, Toulouse-Lautrec, Vallotton, Vuillard, Memorial Art Gallery of the University of Rochester, Rochester, New York, 1984; Les Peintres de la Revue blanche, Maeght, Paris, 1966.

12. Félix Vallotton, Les Cinq peintres, 1902–1903, Kunstmuseum Winterthur.

13. Maurice Denis, journal entry for March 1899, in Journal, Vol. 1, La Colombe, Paris, 1957, p. 150.

14. In 1898, Julius Meier-Graefe already remarked that »Was Vallotton in der Malerei anstrebt, hat er auf bescheidenerem Niveau erreicht. Die Malerei ist seine letzte Phase; die Vorschule, in der er alles das fand, war ihm der Holzschnitt. Man kann sagen »war«; denn wenn wir auch hoffen dürfen, dass Vallotton noch manches neue Blatt in die Welt hinausschickt, schwerlich kann er seiner Art, wie sie sich in diesen Gravüren äussert, noch viele neue Noten hinzufügen«. Julius Meier-Graefe, Félix Vallotton. Biographie des Künstlers nebst dem wichstigsten Teil seines bisher publicierten Werkes und einer Anzahl unedierter Originalplatten, Berlin, Stargardt, and Paris, Sagot, 1898, pp. 10–11.

15. Meier-Graefe, 1898, p. 11ff.

16. Several preliminary designs did not make it into the album. See Christian Rümelin et al., Félix Vallotton. De la gravure à la peinture, Benteli, Zurich, 2010. Only thirty albums were printed, after which the original blocks were destroyed, of which a cancellation sheet testified. The destruction of the blocks is discussed by Dario Gamboni in The Destruction of Art. Iconoclasm and Vandalism since the French Revolution, Reaktion Books, London, 1997, p. 124.

17. Jean de Beauvais, review of Cesare Lombroso's La femme criminelle et la prostituée (1896), La Revue blanche, Vol. 11, second semester, 1896, p. 277.

18. August Strindberg, »Sur l'infériorité de la femme«, La Revue blanche, No 8, 1895, pp. 1–20.

19. The Annales du théâtre et de la musique of 1894 (ed. Noël and Stoullig), p. 545, describe the »effect of terror« with which the play had been received in Denmark: »On raconte en outre que, lors d'une tournée de Père, en Danemark, dans une des premières villes, une dame mourut au cours de la représentation; dans une autre une spectatrice accoucha […] Si bien que la pièce dut être interdite comme fournissant matière à trop d'incidents tragiques«.

20. See Felix Krämer, »Ort der Heimlichkeit. Félix Vallotton Das rote Zimmer«, in Das unheimliche Heim. Zu Interieurmalerei um 1900, Böhlau, Cologne, Weimar, Vienna, 2007, p. 141.

21. According to Henry Ellenberger, the project to unveil man's self-deceptive nature and his inclination to deceive others originates with Schopenhauer's and Nietzsche's idea that consciousness is based on lies. Henry Ellenberger, The Discovery of the Unconscious. The History and Evolution of Dynamic Psychiatry, Basic Books, New York, 1970, pp. VIII and 273–277. The idea was concurrently developed in literature by Dostoevsky and later Ibsen.

22. Ellenberger, 1970, p. 273.

23. Frantisek Deák, Symbolist Theater. The Formation of an Avant-Garde, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1993, p. 196. In Ibsen's Ghosts, for example, performed by the Naturalist Théâtre Libre in Paris in May 1890, the secret gradually uncovered is the transmission of a hereditary venereal disease from father to son.

24. Eugene Glynn, »The Violence within: The Woodcuts of Félix Vallotton«, ARTnews, No 3, Vol. 74, 1975, p. 39.

25. »He [the Parisian bourgeois] has marked preference for velour and plush, which preserve the imprint of all contact. In the style characteristic of the Second Empire, the apartment becomes a sort of cockpit. The traces of its inhabitant are moulded into the interior. Here is the origin of the detective story, which inquires into these traces and follows these tracks«. Walter Benjamin, »Paris, Capital of the Nineteenth Century« (Exposé of 1939), in Walter Benjamin, The Arcades Project, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, MA, 1999, pp. 19–20.

26. Lise Marie Holst was the first to propose this lineage in her M.A. thesis »Félix Vallotton's Intimités: Le Cauchemar d'un érudit«, Oberlin College, 1980, quoted in Richard S. Field, »Exteriors and Interiors: Vallotton's Printed OEuvre«, in Sasha M. Newman (ed.), Félix Vallotton. A Retrospective, Abbeville Press, New York, 1991, p. 78.

27. »La matière de l’œuvre d'art«, Maurice Denis, »Notes d'Art et d'Esthétique. Le Salon du Champ-de-Mars. L'Exposition de Renoir«, La Revue blanche, 25 June 1892 [signed Pierre L. Maud], pp. 360–367, reprinted in Maurice Denis, Théories. 1890-1910. Du symbolisme et de Gauguin vers un nouvel ordre classique, Rouart et Watelin, Paris, 1920, p. 17.

28. Joseph Masheck cites a paragraph from Charles Dickens's Hard Times (1854) discussing the impossibility of representing flowers on a floor carpet. In this scene, Henry Cole, one of the defenders of »good« design and the Superintendant of British design institutions, is transformed into a very strict school inspector. Masheck, 1976, p. 84.

29. The Red Room (1898, Lausanne, Musée Cantonal des Beaux-arts); Five O'Clock (1898, private collection); L'Attente (1899, private collection); Interior. Red Chair and Figures (1899, Zurich, Kunsthaus); The Visit (1899, Zurich, Kunsthaus); Sentimental Discussion (1899, Genève, Musée d'art et d'histoire).

30. Krämer, 2007, pp. 128–129. The title of this painting is The Visit (1899, Zurich, Kunsthaus).

31. Following the Hydropathe composer Georges Fragerolle's definition, Philip Dennis Cate has described fumisme as »an art form that rested on scepticism and humour, of which the latter was often a black variety … the function of fumistes was to counteract the pomposity and hypocrisy they perceived as characterising so much of society«. In Philip Dennis Cate and Mary Shaw (eds.), The Spirit of Montmartre. Cabarets, Humor, and the Avant-Garde, 1875–1905, Jane Voorhees Zimmerli Art Museum, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ, 1996, p. 23.

32. Richard S. Field and Sasha M. Newman develop the relationships between Vallotton's Intimités and the novels of Paul Bourget in Newman (ed.), 1991, pp. 139–140, p. 277 n. 12, 278 n. 35.

33. »This is the perfect use of the mystery that constitutes the symbol: gradually to evoke an object in order to show a state of mind, or, inversely, to choose an object and, by a series of decipherments, to abstract from it a state of mind«. In Jules Huret, Enquête sur les tendances littéraires, Charpentier, Paris, 1891, p. 60.

34. Simpson, 2000, pp. 177–204. For a broader discussion of the close ties between Symbolist literature and painting, see Dario Gamboni, »Le ‘symbolisme en peinture’ et la littérature«, Revue de l'art, No 96, 1992, pp. 13–23.

35. Simpson, 2000, p. 178.

36. In line with the Symbolist emphasis on the importance of the état d’âme, Nabi paintings usually did not carry narrative titles. These two titles too are apocryphal and merely descriptive.

37. See Marina Ducrey (ed.), Félix Vallotton 1865–1925. L'oeuvre peint. II, Catalogue raisonné, 5 Continents, Milan, 2005, pp. 147–149.

38. See Ducrey (ed.), 2005, pp. 147–149 and Krämer, 2007, pp. 136–141.

39. According to some scholars, Vuillard's painting was inspired by a theme similar to that of Vallotton's interior scenes, namely »the tragedy of adultery played out in his sister's home«. See Isabelle Cahn, »Repression and Lies«, in Félix Vallotton, Fire Beneath the Ice, exh. cat., Van Gogh Museum, Lecturis, 2014, p. 98.

40. Ducrey (ed.), 2005, pp. 126–127.

41. The carpet that is best visible, the one to the lower left side of the painting, is framed with a geometric rim often seen in Chinese carpets, but its central pattern and earthly colour scheme rather bring to mind Pre-Columbian weavings. Unfortunately, I have not been able to find out if and where Vallotton might have been able to see such weavings.

42. Already in 1893, the critic Gustave Geffroy remarked that Vuillard's picture surfaces were reminiscent of »the woolly rear side of tapestries«. Geffroy, »Vuillard, Bonnard, Roussel«, in La Vie artistique, Vol. 6, Floury, Paris, 1900, p. 296.

43. »To one of the young neotraditionists, still in school, referring to a very white woman that he had painted, on whom the light played in fluttering rainbow hues, – and it was this colour that interested him, he had been looking for it for an entire week, – a modern master said that »this wasn't nature, you wouldn't sleep with this woman!«, Maurice Denis, Définition, in Denis, 1993, p. 11. The reinsertion of the anecdote in the article »L'enseignement sur le dessin«, in 1917, confirms that the young painter in the story was Denis himself.

44. Vallotton had learned to cultivate this preference from a young age and shared it with his friend and teacher Charles Maurin. In 1888, after a trip to the Netherlands, the latter wrote to Vallotton: »My hatred of Italian paintings has increased, also of our French painting […] long live the north and merde to Italy«. In Félix Vallotton. Documents pour une biographie et pour l'histoire d'une œuvre, Vol. I., 1884–1899, Bibliothèque des arts, Paris, 1973, p. 44. English translation in Julian Barnes, »Better with their clothes on«, The Guardian, Saturday 3 November 2007. Paul Signac believed that Vallotton erred with his new direction in painting, on view in the gallery of Ambroise Vollard in Paris in 1898: »[…] as to the Vallottons, they are the most anti-artistic pictures that can be. This intelligent boy errs completely. He is not a painter in the least! He believes he is following the tracks of Holbein and Ingres by being precise and dry but, unfortunately, he only brings to mind the worst pupils of Bougereau. It is ugly … and stupid. And certainly Vallotton has a feeling for beauty and intelligence; his woodcuts prove it«. Signac, April 1898, »Extraits du Journal inédit de Paul signac II, 1897–1898«, published and translated by John Rewald, Gazette des beaux-arts, No 39, 1952, pp. 302–303.

45. »C'est le premier peintre de son époque, dit-on dans les gazettes«. Félix Vallotton, »L'Exposition Holbein, à Bâle«, Gazette de Lausanne, 1897, p. 3.

46. »…a great education and a lesson that will not be lost«. Vallotton, 1897, p. 3.

47. Julius Meier-Graefe discussed Vallotton's relationship to Ingres in the following terms: »By going back to Ingres, Vallotton seeks to reconquer these [classicist] elements of painting. But with this, he does not go back to Ingres's time, rather seeking to fuse them into modern expressive forms in order to make them into bearers of artistic sensation occupying us today«. Meier-Graefe, 1898, p. 10 [author's translation: »Indem Vallotton auf Ingres zurückgeht, sucht er diese Elemente der Malerei zurückzuerobern. Aber er geht mit ihnen nicht in ide Zeit Ingres zurück, sondern sucht sie zu modernen Ausdrucksformen umzugiessen und sie zu Trägern der künstlerischen Empfindungen zu machen, die heute in uns lebendig sind«.]

48. Félix Vallotton, »L'Exposition Boecklin à Bâle«, La Revue blanche, 1897, p. 280.

49. Vallotton wrote 28 articles and essays on art, 3 novels and 10 plays – all of them unpublished during his lifetime.

50. Pierre Quillard, »De l'inutilité absolue de la mise en scène exacte«, Revue d'art dramatique, Vol. 22, 1891, p. 181.

51. Krämer, 2007, p. 134.

52. »Remember that a picture, before being a battle horse, a nude, an anecdote or whatnot, is essentially a flat surface covered with colors assembled in a certain order«. Denis, 1993, p. 5.

53. Vallotton's later nudes have been called »appalling«, »ugly«, »distorted«, »joyless«, etc.

54. See, for example, Alberto Martini, »Félix Vallotton: Classicist Manqué«, Apollo, No. 78, 1963, pp. 416–417. René Jullian identified Ingres’ influence on Vallotton's nudes as visible in »the concentrated density and the monumental permanence of form, which with him as with Ingres are not in contradiction with the »flatness« of the painting«. Jullian, »Ingrisme et nabisme«, Bulletin du Musée Ingres, Nos 47–48, 1980, pp. 47–53, here p. 53.

55. The Figure in the Carpet appeared in the first issue of Cosmopolis in January and February 1896.

56. March 1897.

57. On the history of painter's »secrets«, see Marc Gotlieb, »The Painter's Secret: Invention and Rivalry from Vasari to Balzac«, The Art Bulletin, No. 3, Vol. 84, 2002, pp. 469–490.

58. Henry James, The Figure in the Carpet, Martin Secker, London, 1916, [electronic book], Project Gutenberg, 2013, n.p., http://www.gutenberg.org/files/645/645-h/645-h.htm

59. »For himself, beyond doubt, the thing we were all so blank about was vividly there. It was something, I guessed, in the primal plan, something like a complex figure in a Persian carpet«. James, 1916/2013, n.p.

60. Wolfgangs Iser, The Act of Reading. A Theory of Aesthetic Response, Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, 1978, p. 4. Iser's interpretation is cited and analysed in David Liss, »The Fixation of Belief in The Figure in the Carpet: Henry James and Peircean Semiotics«, The Henry James Review, No 1, Vol. 16, 1995, p. 37.

61. Iser, 1978, p. 8, and Liss, 1995, p. 37.

62. Marcel Duchamp's insistence on the role of the beholder in the »creative act« can be seen as a heritage of Symbolist aesthetics.

63. »Confusion« and »complexity« are two of the principles of decorative form identified by Charles Blanc in his Grammaire des Arts décoratifs, Renouard, Paris, 1882, pp. 16–18 and pp. 27–28. Cf. Simpson, 2000, pp. 179–181. John L. Sweeney has noted how suggestion (and its transmitting) is a term that seems to come forth from James's discussion of paintings in his critical writings. »Introduction«, in John L. Sweeney (ed.), The Painter's Eye: Notes and Essays on the Pictorial Arts by Henry James, Hart-Davis, London, 1956, pp. 13, 15, 17.