Summary

There are several professional competences involved in the creation of a museum exhibition. This article investigates the collaboration between the artist/scenographer and the museum. Further, it seeks to contribute to a historical understanding of such collaborations by exploring the work created by the Swedish artist/scenographer Lennart Mörk in the 1960s and 1970s. It analyses the arguments used to justify the involvement of an artist/scenographer, and looks more closely at the nature of the collaborative work that ensued when the two exhibitions Oskuld – Arsenik (1966/67) at Nordiska museet and Gustaf III (1972/73) at Nationalmuseum were created. The article argues that the recruitment of a theatre decorator/stage artist, as this group of professionals were referred to at the time, was part of a strategy that allowed the museum to realize complex exhibition concepts, while also making the display more emotionally engaging and accessible, something that was increasingly demanded of the museums at the time. Moreover, it challenged a traditional museum exhibition format, placing less focus on the authentic museum objects and more focus on sensory experience and aesthetics.

Introduction

Artistic interventions have gained in significance within the fields of exhibition and museum design worldwide. Today, collaborations with artist and scenographers are often initiated by museums in order to shake things up, to open up for new, lost, and denied stories, and to create dynamic dialogue between the past and the present. Fred Wilson’s exhibition Mining the Museum (1992–1993) at Maryland Historical Society spurred numerous collaborative projects between artists and museum institutions. Another, more recent example is the painter and film-maker Peter Greenaway who is active as a curator and installation artist. He integrates different media, mainly film and sound, creating atmospheres and telling stories based on artworks and histories, for example in his Paintings revisited series, which includes well-known works such as Rembrandt’s Nightwatch and Veronese’s The Wedding at Cana. In this article, I argue that the work done by artists such as Wilson and Greenaway should be seen as part of a long tradition where artistic/scenographic practices offer a strategy, helping museums to respond to new demands. At the end of the 1960s and beginning of the 1970s, the period covered in this article, museums were encouraged to find new ways of working and many museums wanted to produce more visually striking and emotionally engaging exhibitions.Footnote1 Per Bjurström, working at Nationalmuseum, commented on these demands in 1973: “The tendency has increased nowadays to produce exhibitions which demonstrate historic and artistic relationships and ideas rather than simply to present different bits and pieces as more or less individual aesthetic objects.”Footnote2 In order to respond to this, and other requests, the know-how of experts outside the museum sector was integrated into the production of exhibitions. Despite a growing academic interest for intermedial relationships, there have so far been few studies specifically exploring the relationship between artistic/scenographic practices and the museum exhibition, or what has motivated these collaborations. This article contributes with a historicized understanding of this type of collaboration.

The two exhibitions discussed in this article, Oskuld – Arsenik (1966/67) and Gustaf III (1972/73) presented controversial and ambiguous historical characters, the writer Carl Jonas Love Almqvist (1793–1866) and the king Gustaf III (1746–1792). According to the curators, both of them were individuals that had reclaimed their relevance. In addition, the exhibitions observed the fact that it was 100 years since Almqvist died in 1866 and 200 years since the coup d’etat of Gustaf III in 1772. The artist and scenographer Lennart Mörk (1932–2007) was well–established in the world of theatre and art but less so in the museum world. The article explores the arguments used to justify the involvement of Mörk, the collaborative work that ensued, and the reception of the two exhibitions. What were the qualities that an artist/scenographer was expected to bring into the exhibition? Were there any controversies or critique against it? What was the nature of the collaboration? How and to what effect did the scenography integrate museum objects?

Scenography and museum practice

Several researchers have pointed out that the staging an exhibition in many ways resemble the work done in a theatre production. The curator/scenographer Frank den Oudsten describes theatres and exhibitions as “narrative environments” and claims that they share techniques and strategies – he even maintains that they share a common ancestry.Footnote3 Scenography has repeatedly been presented as a new contribution to museum exhibition, a practice that will help revitalize the crisis of curatorship and help open up curatorial possibilities – however, I would argue that it is far from a new phenomenon.Footnote4 Rather the relationship between the two practices has long historical roots. The two have inspired each other, in the sense that museums and archives have provided a source of inspiration for the stage and in return set designers/scenographers have offered visual and choreographic solutions for museums. Their solutions have occasionally challenged our preconception of what a museum is.

Pamela Howard suggests in What Is Scenography? (2009) that the museum concept could move into the theatre, as a way of making the actors more aware of the scenographer’s contribution to the play.Footnote5 By posting visual information in the rehearsal room, the scenographer places visual art firmly on the daily agenda. Howard refers to this suggested museum-like display, which might change and to which the actors can contribute, as a “living museum”.Footnote6 Block buster exhibitions, on the other hand, she refers to as “a reverse kind of theatre”, the static exhibits as “performers” and the visitors as “moving performers”.Footnote7 In Beyond Scenography (2019), Rachel Hann explores the theory of scenographics and what scenography does. She discusses the crafting of temporary spaces and explains that we should not limit scenography to being only a visual practice since a narrow definition negates the complexities of a scenographic experience.Footnote8 This need for a holistic approach, where you integrate a number of elements to create a synthesis, is also relevant when considering exhibitions. Other important similarities between the two mediums concern audience reception and interaction. Carole Charnow, President and CEO of Boston Children’s Museum, has reflected on the similarities of production in Creating Exhibitions: Collaboration in the Planning, Development and Design of Innovative Experiences (2013):

As a producer of opera and theater (…) I recognized the parallel process of production. We first decide upon an opera or play to produce, which is similar to the exhibition content or subject matter. (…) the advocacy positions of the creative team, each of which has a direct counterpart in operatic production: the project advocate assembles the team (the opera producer); the curator advocates for the subject matter (as does the conductor); the exhibit developer/educator advocates for the visitor/audience (just like the opera director); and both exhibits and operatic production employ designers and production managers. Both projects proceed in a similar way, navigating the turbulent shoals of creative collaboration.Footnote9

Lennart Mörk started his career as a window dresser at Nordiska kompaniet in Stockholm, which would later prove useful when working in a museum context. Window dresser is a profession positioned between advertising and retail as well as between the artistic and the commercial.Footnote12 Moreover, the profession is positioned between a high-profile creative profession and a low-profile service occupation, similar to hierarchies existing also in a museum context. In an article published May 7, 1967, the journalist Åsa Wall described how a “theatre decorator” (teaterdekoratör) had to be a skillful artist, sculptor and architect, as well as practical and knowledgeable in crafts, while also understanding how to collaborate creatively with a director.Footnote13 At the time, only a short course was offered students at the Royal Institute of Art, and the aspiring theatre decorator had to find other ways of learning the basics and developing their skills, often by assisting more senior colleagues. However, both the job title and the opportunities to educate yourself to become a theatre decorator/stage artist, or a scenographer as it later would be called, were about to change.Footnote14 Mörk was one of seven professionals featured in Wall’s article.Footnote15 Wall quoted him saying that he believed that the theatre decorator would gain more influence in the future, and that the décor would stop being treated like a cake that is carried on and off the stage.Footnote16 However, it was not only the profession of the theatre decorator that was changing at the time, so was the museum profession.

In 1998, Dansmuseet presented Mörk’s long career as an artist, window dresser, scenographer and costume designer in the retrospective – Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater. The exhibition catalogue included a number of articles covering different aspects of Mörk’s career. One of the articles was written by the art historian, artist and museum curator Ragnar von Holten who has also written two articles (1989, 1994) about Mörk’s sketches in the collections of Nationalmuseum and his work on the play Vintersagan, performed at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in (1994).Footnote17 In addition to these texts, Mörk is briefly mentioned in several articles and books because of the work he did together with the director Ingmar Bergman.Footnote18 For instance, art historian Magdalena Holdar investigated eight theatre productions staged by the Swedish director between 1984 and 1998 in her dissertation Scenography in Action (2005), and Mörk was the scenographer in two of these productions. Holdar and von Holten’s texts present Mörk primarily as an artist and scenographer in the theatre, while this article focuses on Mörk’s less known, but no less innovative, work in the museum.

Method and material

An exploration of the relationship between scenography and museum practice is inevitably multidisciplinary in its character. This study is based on critical heritage studies and incorporates art history, cultural-historical media research, exhibition studies, theatre, scenography and performance studies. Museum exhibitions as well as theatre productions are expressions of choices made, related to functional assessment and aesthetic considerations, and the design can be studied as the result of artistic, scenographic and curatorial intent, an intent that also reflects deeper changes in society.Footnote19 The aim of this article is to describe and analyse the exhibition process and exhibition itself by studying archival, textual and visual material, for example, letters, memos and photographs. Newspaper articles provide important material helping us understand how the exhibitions were received, but also how they were to some extent the result of interaction with critics and audiences. The database of digitized Swedish daily newspapers at the National Library of Sweden has been specifically useful for this purpose. In the archives of Nationalmuseum and Nordiska museet we also find documentation, including photographs, designs, letters, notes, contracts and press material (). However, Mörk’s preparatory work is only partially documented in the archives, and only a few notes, letters and drawings reveal the intentions and creative process behind the display. The work he did for the theatre stage has been better preserved, for example, the designs for Drottningens juvelsmycke (1957) which can be found in the archives of the Swedish Museum of Performing Arts (Scenkonstmuseet) and Musikverket. The designs for the exhibition Ararat are preserved in the collections of Skissernas museum.Footnote20

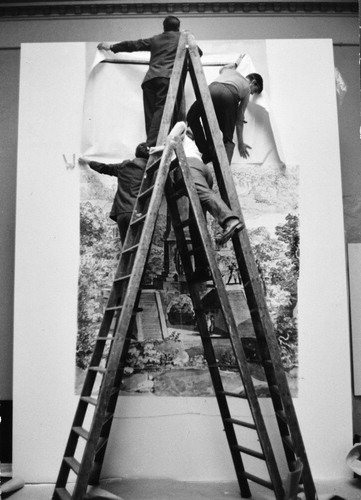

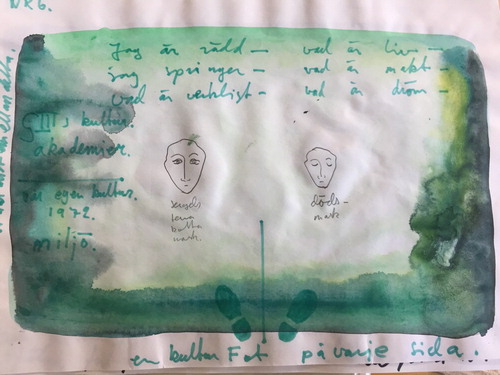

Fig. 1. Parts of the exhibition process are well documented. In the archives, we find informative photographs of the set-up of Gustaf III at Nationalmuseum in 1972 as well as Oskuld-Arsenik at Nordiska museet in 1966. (1972, Nationalmuseums bildarkiv).

The article is structured as follows: The first part introduces Lennart Mörk, and then each exhibition is described and analysed, focusing on specific segments in each display as well as the reception of the exhibitions and specifically the scenography. Finally, the article concludes with a discussion about scenography and artistic practice in the museum.

Renewing the exhibition medium

At the end of the 1960s, the media, politicians and museum staff debated democracy and equality in museums and how to make museums more accessible and relevant. There was a shift of focus from collecting and research towards the visitor and the exhibition medium.Footnote21 The actor Thommy Berggren tapped into the debate when criticizing cultural institutions and museums for being elitist. Nationalmuseum responded to Berggren’s critique by inviting a journalist from Dagens Nyheter to an evening event when seventy cleaners were given a guided tour of the Gustaf III exhibition.Footnote22 A result of the museum debate in the 1960s was the two commission reports that were published shortly after the two exhibitions discussed in this article; Museerna (1973) and Utställningar (1974: 43) by 1965 års musei- och utställningssakkunniga (MUS 65). Around the same time, the government agency Riksutställningar (Swedish Exhibition Agency) began to produce travelling exhibitions and explored new ways to work and collaborate. Starting in 1970, for example, several productions were aiming to integrate museum exhibitions with theatre productions, generally with the intent to provide the plays with a context and to support discussions about imperialism and environmental issues.Footnote23 The productions were generally the result of a group effort that involved a producer, a director, a scenographer and actors.Footnote24 Occasionally the stage set itself acted as an exhibition, for example in the 1971 production of Den saktmodiga revolutionen which toured 40 theatres.Footnote25 These collaborations between Swedish theatres and museums have been discussed in Olle Näsman’s dissertation Samhällsmuseum efterlyses. Svensk museiutveckling och museidebatt 1965–1990 (2014), however a more comprehensive study of these specific projects would be interesting.

Lennart Mörk

Mörk moved from Falköping to Stockholm in 1947 and started as an aspiring window dresser at the large department store Nordiska kompaniet the following year. He was also training to become an artist at Konstfackskolan and combined evening classes with his work at Nordiska Kompaniet.Footnote26 In 1955 he began his training at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts. Only two years later, in 1957, Mörk was able to make his debut as a scenographer at the Royal Dramatic Theatre (Dramaten), in Alf Sjöberg’s adaption of the play Drottningens juvelsmycke written by Carl Jonas Love Almqvist. The play is set in the Gustavian period and circles around the murder of Gustav III. When Mörk learned that they were planning a production of Drottningens juvelsmycke at Dramaten, he contacted the director Sjöberg and showed him the designs for stage sets he had made without knowing about the upcoming production. According to the professor of literature Sverker R. Ek, Mörk felt a close affinity to Almqvist.Footnote27 Sjöberg liked the designs and hired Mörk.Footnote28 The work [Mörk did for Drottningens juvelsmycke] helped him finance his further studies at the Royal Institute of Art.

Mörk was active as a scenographer for fifty years, 1957–2007 and collaborated with museums in 1966, 1972 and in 1998. Apart from Nationalmuseum and Nordiska museet, he worked for Historiska museet in collaboration with dancer and choreographer Donya Feuer. Together they produced the dance concert Ett spel för museet. Feuer and Mörk also worked at the Royal Dramatic Theatre and both collaborated with director Ingmar Bergman. In addition, Mörk expressed himself as an artist and highlighted current issues in a number of solo projects, which could be considered a mix of exhibition and art installation. The travelling exhibition/installation, Vår verklighet – Divina Commedia (1973) dealt with the city, life, aging and sexuality. In the project Ararat (1976) Mörk worked with environmental issues in a visual debate about the subject, which was shown at Moderna museet and the Venice biennale.Footnote29 Some of Mörk’s art can be found in the collections of Nationalmuseum and he received two large commissions for public artworks, the exterior walls of Riksteatern’s workshops in Hallunda (1988) and the work Elementen och naturlagarna (1973) in the metro station Tekniska högskolan in Stockholm (). When Mörk’s career was portrayed in a retrospective at Dansmuseet in Stockholm in 1998, Mörk made the exhibition design himself and Ragnar von Holten, who had followed his career from the start, was involved in the process.Footnote30 What was it that attracted Mörk to work with museum exhibitions to start with? In a 1966 interview about his work in Göteborgs handel- och sjöfartstidning, Mörk commented that it was really fun to engage the fantasy of the scholarly museum staff – who were there, gnawing at their stone axes.Footnote31

Oskuld – Arsenik (1966)

A century after the death of writer and journalist Carl Jonas Love Almqvist (1793–1866), Nordiska museet decided to create the exhibition Oskuld – Arsenik. The exhibition opened September 15, 1966, and due to its popularity, it was prolonged from November until January 1967. Almqvist worked as a clerk, teacher, and headmaster and was ordained a pastor before starting to write full time. In addition to his journalistic work he wrote novels, short stories and poetry. Almqvist actively supported social reforms concerning marriage and the punishment of criminals. However, in a dramatic turn of events, he fled Sweden for USA in 1851, escaping accusations of fraud and attempts to poison a man he owed money. He tried to return to Sweden but died in Bremen in 1866. Nordiska museet has a close connection to Almqvist since the writer was a good friend of the father of Arthur Hazelius, the founder of the museum. This relationship motivated the author’s sister Maria to donate several of her brother’s belongings to the museum, such as letters, documents and manuscripts.

Tableaux morts-vivant

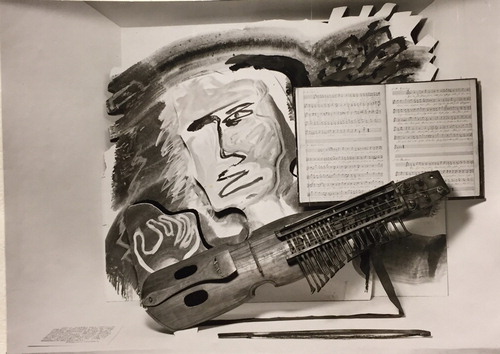

Sten Lundvall, an archivist at Nordiska museet, came up with the concept of the exhibition and wrote an outline of the project. The text was reworked by exhibition curator/art historian Elisabeth Stavenow-Hidemark and published in a small pamphlet and later included as an article by Lundvall in the yearbook of the museum, Fataburen. Lundvall wanted to create an exhibition that portrayed both the history and the imagination of the writer, and the idea was to keep those two dimensions separated by a thin veil, a gossamer, which was a recurring theme in Almqvist’s writing.Footnote32 In order to do this, he developed the well-known concept of the tableau. The tableau feature was inspired by Almqvist’s poems collected in Songes and relates to the concept of tableaux morts-vivant which the author discussed in the text.Footnote33 Mort is added since, despite the people in tableaux vivants being very much alive, they stood still, immobile as if they were dead. This use of the tableau reminds us of Howard’s idea of the exhibition as “a reverse kind of theatre”, the static exhibits as “performers” and the visitors as “moving performers”.Footnote34 Lundvall recognized the connection between Almquist’s tableaux morts-vivant and the tableaux-like displays Hazelius created with mannequins at Drottninggatan, the first home of what would later become Nordiska museet.Footnote35 The art historian Gerd Reimers described the thematic tableaux in Oskuld – Arsenik as “snabba presens-glimtar” – quick glimpses of the present.Footnote36 Sverker R. Ek would later describe Mörk’s work in Oskuld – Arsenik as “bildteater” – image theatre.Footnote37 These attempts to find the appropriate words to describe Mörk’s displays suggest that they appeared as something new or unusual although there were strong historical connections to earlier displays at Nordiska museet and Skansen ( and ). The tableaux morts-vivant seem to have worked on the border between literature and reality, between now and then. Different media came together, interacting with the rest of the exhibition, creating an atmosphere that made the visitor part of the worlds imagined by Almquist, rather than just looking at them.Footnote38

Fig. 3. Mörk combined his skills as an artist and scenographer when creating Oskuld-Arsenik and Gustaf III. The display “Vargens dotter” in Oskuld- Arsenik included music sheets, a nyckelharpa (keyed fiddle) and Mörk’s painting of a man playing the instrument. Photo: 1966, Nordiska museets arkiv.

Fig. 4. The stage costume of the mechanical character “le mannequin/la mannequinne” in Almqvist’s Drottningens juvelsmycke was veiled by a golden bar taken from the old Gustavian opera house, torn down in the 1890s. The golden bar was there to indicate a transfer between fiction and reality to the visitor. Photo: 1966. Nordiska museets arkiv.

Lundvall needed someone who could turn the tableau concept into a working exhibition. He spoke to the director Sjöberg at Dramaten who suggested creating tableaux in varying scales and then recommended his colleague, Mörk, to do the actual work.Footnote39 Stavenow-Hidemark acted as project manager and Mörk collaborated with her throughout the process. In 1966 Mörk was also working on the scenography for Waiting for Godot and Pinnochio at Dramaten (the Royal Theatre) in Stockholm.Footnote40 Still, in the exhibition catalogue Stavenow-Hidemark refers to Mörk as an artist (konstnär), rather than “stage artist”, “theatre decorator” or “scenographer”, reminding us of the changing job titles and the changeable position of the profession at the time. Using Mörk’s skills in the exhibition production, meant that the museum could create an exhibition at the intersection of art, literature and theatre. As a student, Mörk had been fascinated by Almqvist’s play Drottningens juvelsmycke, and as I mentioned earlier, the play became Mörk’s entry ticket to working professionally in the world of scenography.Footnote41

The museum published a book for the exhibition – sju röster om Almqvist (1966) which contained seven (fictive) voices belonging to people contemporary to Almqvist, telling their stories about the author. The texts were compiled and dramatized by Bengt af Klintberg, who was employed by the museum while maintaining a parallel career within the world of theatre. Not surprisingly, Mörk was responsible for the scenography when sju röster om Almqvist was staged 12 October 1966. The book was illustrated with photographs of the exhibition taken by the photographer Beata Bergström, otherwise employed by numerous theatres in Stockholm, among them the Royal Dramatic Theatre (). Since then, theatre performances have become more established in a museum context, in the same way, we see how objects and installations support the narrative in the theatre, in addition to the spoken work.Footnote42

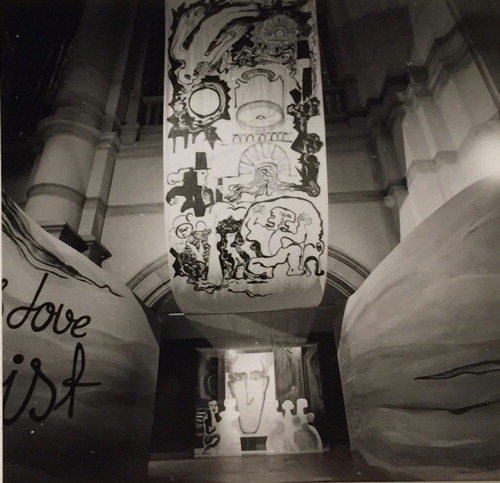

Fig. 5. The entrance of the exhibition pulls the visitor into the exhibition – or is it the exhibition that pours out into the large hall? Photograph by Beata Bergström, November 1966, Nordiska museets arkiv.

The exhibition space consisted of a long rectangular room divided into a number of tableaux with mannequins and painted figures. The scale of the displays varied and the visitor walked between large landscapes and intimate rooms. Artificial light played an important role in the exhibition and there were no windows. Adding to the ambience of the display, there was music from the period played from loudspeakers in the exhibition. The exhibition was thematic, portraying the worlds Almqvist created in his books and poems, as well as major events in his life. One of the thematic displays, “The Prison and the Madhouse”, was inspired by Almqvist’s interest in the (mis)treatment of prisoners. The founder of Nordiska museet, Arthur Hazelius, likewise had been interested in collecting objects that related to earlier forms of punishment of criminals, and the museum collections still include iron chains and an executioner’s sword. In 1893 Hazelius had created a tableau with a costumed doll tied to a pillory, staging the punishment of Ankarström who murdered Gustav III in 1792.Footnote43 The archival material suggests that Mörk was able to influence which objects were included in the exhibition. Some of them added ambience rather than authenticity. For example, a straightjacket was borrowed from the Museum of Medical History in Stockholm, and on the cover of Svenska Dagbladet in September 1966 the readers could see Mörk lifting the heavy chains included in the display, emphasizing the sensory aspects of it (). At the time, Stavenow-Hidemark stated in an interview that it would not have been enough to exhibit Almqvist’s pens and hats, which were valued objects in the collection.Footnote44

Fig. 6. The chains are part of one of the thematic displays, “The Prison and the Madhouse”. Stavenow-Hidemark is on the left and Mörk is standing on the right. Photo: 1966, Nordiska museets arkiv.

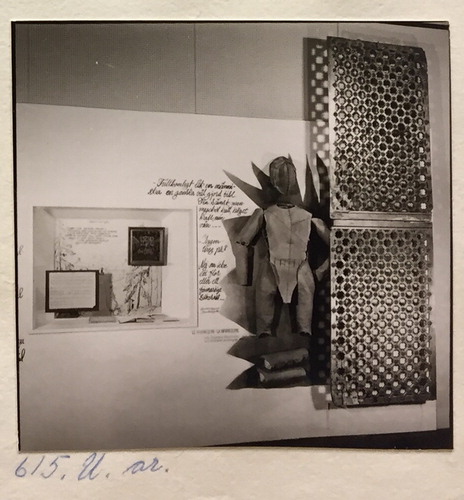

In fact, there were few objects with direct links to Almqvist; instead words and written documents had a prominent place, as quotes were taken from Almqvist’s writing and placed on the walls. After trying different options, Mörk and Stavenow-Hidemark decided to use varying styles of handwriting on the walls, styles that were “animated, yet easy to read” while also reflecting the content.Footnote45 These texts were executed by professionals trained in the art of hand lettering, employed by Dohrns reklambyrå, an advertising agency which had started as a business in 1925 (). The company was usually hired to create advertising for cinemas and theatres, displays cases, signs and window dressing. The texts proved to be a success, and in her feedback to Dohrns reklambyrå Stavenow-Hidemark stated that the visitors “read and read and most of them read it all”.Footnote46 She expressed a particular satisfaction with the “nervous aggressiveness in every word” created by the skilled sign writer Kjell Rosdahl.Footnote47 The careful design and craftsmanship turned the text into something solid and material. Mörk and Stavenow-Hidemark even described the written quotes as objects, and the objects as symbols.Footnote48 The display also included maps, letters, documents from the court, newspapers, photographs, costumes and a few purpose-made objects that were “props” illustrating the narrative, including iron chains and a sheaf of oats. Decoration painters from Dramaten helped build the exhibition and the firm Emelie Åquist AB provided artificial flowers. Contemporary artworks were also included, illustrations of poems and parts of stage sets, for example Mörk’s work on Drottningens juvelsmycke (1957) and Ann Margret Dahlquist-Ljungberg and Sven Ljungberg’s linoleum prints that had been projected as a backdrop on the set of Amorina in 1951 ().

Fig. 7. After trying different options, Mörk and Stavenow-Hidemark decided to use varying styles of handwriting on the walls, styles that were “animated, yet easy to read” while also reflecting the content. The texts were created by professional sign writers at Dohrns reklambyrå. Photo: 1966, Nordiska museets arkiv.

The response in the press varied, and according to the critic “Veronica”, most likely Veronica Andréasson, the new exhibition design shocked many museum workers.Footnote49 Ethnologist, curator and museum director Stefan Carlén claims in his dissertation Att ställa ut kultur (1990) that the involvement of a scenographer caused a divide between ethnologists and art historians at the museum, where the latter group were more positive, appreciating the (increasingly) aesthetic dimension of the display. Admittedly, Oskuld – Arsenik was far from a conventional display, which some critics, for example, the art historian Gerd Reimers, considered suitable for the subject.Footnote50 Reimers described it as a conceptual exhibition filled with facts and fascinating objects, carefully selected and dramatically arranged.Footnote51 The reviews tended to focus specifically on Mörk’s contribution, which was considered visionary and different from the traditional exhibitions offered at museums. Göteborg Handels och Sjöfartstidning even referred to it as a completely new type of exhibition, where chronology and authenticity had been tossed aside in favour of an artistic expression and where “dead stuff” was placed in a light that brought life into the objects and to Almqvist.Footnote52

Gustaf III (1972/73)

The exhibition Gustaf III at Nationalmuseum ran from 9 November 1972 until 31 March 1973.Footnote53 There were several reasons why the museum decided to produce an exhibition about the king Gustav III in 1972, one of them being the long historical connection between the museum and the king. It was Gustav III’s collections that formed the basis of Kongl. Museum that opened in 1794, and constituted the origin of Nationalmuseum. Still, the catalogue, work notes and interviews reveal some of the ambivalence that the curators seem to have felt towards Gustav III in 1972. The museum director Bengt Dahlbäck explained in a letter to his colleague Gustaf Näsström that the king is controversial, and people feel that he is none of our business or to be avoided.Footnote54 When addressing the staff during the production, Dahlbäck emphasized that the exhibition needed to find the right voice.Footnote55 He later explained in the catalogue that the museum’s ambition was to avoid a static portrayal of Gustav III – rather it was the complexity of the king as a person that set the tone of the exhibition.Footnote56

The exhibition was the result of a collaboration that involved all departments and the production relied on a group of nine curators: Ulf Abel, Per Bjurström, Stig Fogelmarck, Ulf G. Johnsson, Helena Lutteman, Eva Nordenson, Gustaf Näsström, Lars Sjöberg and the director of the museum Bengt Dahlbäck. Carin Levin-Svensson and Katja Waldén dealt with media relations, while Märta Sahlberg was in charge of the secretariat. The design was the responsibility of Mörk who worked in close dialogue with Dahlbäck. At the time the museum tried a radically new way of working, inviting the staff to general meetings (stormöten), which some of the older members of staff refused to attend.

When marketing the exhibition, Nationalmuseum collaborated with Mörk’s former employers – the large department stores Nordiska Kompaniet and PUB. Both stores agreed to organize displays on the theme Gustav III. In addition to lending objects from the collections, the museum proposed that PUB would display one of Mörk’s drawings of the king during the coup d’état, wearing a white band around his upper arm. Nordiska Kompaniet, on the other hand, was offered photographs of two paintings by the eighteenth century artist Pehr Hilleströms sr.Footnote57 In this way, the museum could create a buzz around the exhibition in a public and commercial setting.

Surprisingly, Mörk’s important contribution to the Gustaf III exhibition was not recognized in the retrospective at Dansmuseet in 1998. At the time, however, his work received a great deal of attention in the press. The end result of the collaborative production could have been a fragmented exhibition; however, this does not seem to have been the impression among visitors and critics, instead Mörk’s strong visual language seem to have brought the exhibition together.Footnote58 The exhibition encompassed six large rooms and ten smaller cabinets. The design carefully created effective narrative spaces and spatial choreographies. The spaces all had a different character; on the one hand the more “scenographic” spaces, designed by Mörk, and on the other hand the reconstructed rooms (such as Ekolsundsrummet), put together by curators. Mörk’s work can be traced in notes and designs in the archives of Nationalmuseum. However, all rooms are not included in this material and the photographic documentation is vital for understanding Mörk’s design (, , and ).

Fig. 9. The display included original theatre décor lit with electric candles, costumes and masques from the eighteenth century. Photo: 1972, Nationalmuseums bildarkiv.

Fig. 10. The Revolution room presented the king’s 1772 coup d’etat and was dominated by a headless king on a mounted horse on loan from the Royal Armoury. Gustaf III 1972/73. Photo: Nationalmuseums arkiv.

Mörk was interested in marbling and this is a recurring motif in his work. It is there in the entrance to the Oskuld-Arsenik exhibition, and in 1973 he covered the walls of the metro station Tekniska högskolan with marbling in strong colours.Footnote59 It is also one of the main motives in the Gustaf III exhibition where large marbled screens covered walls and sectioned off parts of the rooms, some of them with marble columns ( and ). The colours of the marble elements were inspired by historical buildings and chinesoire, according to one of the critics.Footnote60 However, Mörk’s dark marbled walls were not to everyone’s liking. It was not the right type of aesthetic according to Eugene Wretholm who compared it to what he saw as the more refined taste of Gustaf III, which the museum normally sanctioned.Footnote61 In other rooms the walls were covered with blown-up photographs of drawings, maps and paintings used in the exhibition, creating a dramatic, stage-like effect (). Another striking feature was the reopening of six large windows facing the Royal Palace on the other side of the water. Dahlbäck strongly promoted that the windows should be opened for the exhibition, claiming that it would add a valuable dimension.Footnote62 The windows had been covered for over 50 years and when they were reopened a stunning view was revealed.Footnote63 The new vista included the Royal Palace, Tobias Sergel’s statue of Gustav III and a large obelisk donated to the burgers by the king, thus creating a visual link to monuments relating to the king. The windows were covered up after the exhibition and would not be restored until the renovation of the museum in 2014–2018.

A theatre-like exhibition

In a leaflet the museum expressed that it wished to stage the king’s experiences and creations, balancing on a fine line between fantasy and reality.Footnote64 This feeling of continuously crossing that line can also be found in the Oskuld-Arsenik exhibition. Carin Levin-Svensson referred to the Nationalmuseum exhibition in her notes as “theatre-like”.Footnote65 The journalist and critic Kurt Bergengren also commented on the theatrical aspects of the display. “Here experts play a theatre of objects and paintings.”Footnote66 The link between the theatre and Gustav III was firmly established through a number of authentic objects, and the display included original theatre décor lit with electric candles, costumes and masques from the eighteenth century (). Moreover, I believe that the fact that Mörk never tried to hide the constructional elements of the design strongly contributed to the feeling of theatricality. Instead of upholding the traditional museum exhibition format conventions, he consciously allowed the visitor to see the back of paintings and screens.

Similarly, to the exhibition at Nordiska museet, there were theatrical performances during the exhibition period. In collaboration with the Opera and Riksteatern, the museum hosted three performances of the ballet God afton vackra mask, produced by Cramérbaletten. The ballet portrayed the murder of the king at a masked ball at the opera in 1792. During the performance, the audience moved around in the exhibition, experiencing “an unreal masked ball with electronic sounds”.Footnote67 The exhibition was slightly adapted during the performances, and the light was cleverly used to choreograph the movement of the audience and enhance the experience of the rooms and the performance.Footnote68 Other events during the period included fireworks on the waters outside the museum to celebrate the anniversary of the king Gustav VI Adolf, four lectures about the king and the Gustavian period and three screenings of the two-hour silent film Två konungar made in 1925.

In a letter to the press, Levin-Svensson described how the ambition of the museum was to offer the visitors an active, emotionally engaging experience instead of a passive viewing of individual objects.Footnote69 This ambition was also explicitly expressed in the exhibition folder and reminds us of the Oskuld – Arsenik exhibition. Still, there were plenty of authentic objects in the exhibition. However, according to the museum the objects were primarily there to evoke emotions related to the life and spirit of Gustav III, only secondly to tell about historical events.Footnote70 According to Margareta Romdahl’s review in Dagens Nyheter Mörk consciously positioned museum objects so that they would empower one another.Footnote71 In the final room, for example, he placed the death mask of the king next to Sergel’s portrait of the living king, and when telling about the conspiracy to kill the king he placed eighteenth century portraits of the conspirators on the wall ().

Fig. 11. Lennart Mörk’s conceptual design for the final room which included the death mask of the king, 1972, F1a 205, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

Mörk and Dahlbäck were very conscious of how easily the exhibition could turn into a traditional art exhibition. In order to avoid this Mörk argued that the focus should be on the king as a person of culture.Footnote72 In July 1972, Mörk sent his ideas for the final room in the exhibition to Dahlbäck and Nordenson. The design of the room was based on a theme focusing on the end and the resumption, and as in Oskuld-Arsenik, authentic objects from the opera were used to indicate a transfer between fiction and reality, between now and then. The visitors entered the room through the entrance doors taken from the old opera where the king was shot.Footnote73 In addition, the cabinet where the king was taken after the shot was reconstructed in the room.Footnote74 In this way, Mörk uses the final room to literally set the stage for the final hours of the king’s life.

The revolution room

The exhibition must be put in relation to the commemorations of the coup d’état staged by the king in 1772. A few months before the opening of the exhibition in 1972, Sergel’s statue of Gustaf III at Skeppsbron, visible from the reopened windows, had become the site of a disruptive and violent commemoration of the king. On 22 August 1972 supporters of the extreme right, Sveriges Nationella Förbund (SNF), Nordiska Rikspartiet and Nysvenska rörelsen, gathered to celebrate the 200th anniversary of the coup.Footnote75 A wreath was placed at the foot of the statue. Demonstrators from the far left, Revolutionära Marxisters förbund, confronted the group, threw the wreath in the water and the police intervened.Footnote76

The apparent political dimension of the exhibition was received with mixed feelings. The Revolution room presented the king’s 1772 coup d’etat and was dominated by a headless king on a mounted horse on loan from the Royal Armoury. Presenting a mounted horse with a headless king in the exhibition was a very effective way of questioning the power of the king and the motivation behind the coup d’etat, thus collapsing a potentially strong monarchical and nationalist symbol. Today Mörk’s installation reminds us of the headless mannequins of Yinka Shonibare MBE’s art, which often relates to the eighteenth century and in one case even to Gustav III who is the protagonist in the video Un ballo in maschera (2004). The headless king in the Revolution room attracted a lot of attention at the time. The art critic Eugene Wretholm found the exhibition and the headless horse a bit too left-leaning – the curators were the ones who had lost their head according to him.Footnote77 Others argued that the political aspects of the exhibition were the best, making history relevant to contemporary politics.Footnote78

Conclusion

Scenography is not restricted to the traditional space of the theatre. This article shows that the recruitment of the artist/scenographer can be seen as part of a strategy that allows museums to realize complex exhibition concepts, while also making the display more emotionally engaging and accessible.

The two exhibitions Oskuld-Arsenik and Gustaf III were created at a time when scenography received more attention in its own right. Mörk, defining himself as an artist and freelance decorator, was a temporary addition to the production team, working in close dialogue with museum curators and bringing his competence as artist/scenographer into the museum. To include Mörk in the production seem to have been dually motivated, firstly by a wish to experiment in order to make the exhibition different and more emotionally engaging, and secondly his conceptual design offered a way of addressing topics that were in some ways complex and difficult. However, once he was involved in the projects, his work expanded and became more closely related to the holistic practice of a scenographer. Light, sound, choreography and actors were added to the display. In addition, he was encouraged to bring his artistic interpretation into the exhibition, helping the museum to solve conceptual dilemmas. Mörk’s use of “non-authentic” objects such as props in 1966 challenged the traditional museum exhibition format and made the display less credible, according to the critics, who still relied on the power of the object to make people relate and learn.Footnote79

The exhibitions were organized at a time when museums were trying to find new ways of creating emotionally engaging and effective displays. The government agency Riksutställningar (Swedish Exhibition Agency) had only just started their efforts to develop travelling exhibitions and new ways of working, collaborating with different cultural groups. Both exhibitions aimed for a less static understanding of the persons portrayed in the exhibitions, and were consciously exploring the boundaries between fantasy and reality and the history of two ambiguous and complex men. It is possible that this ambition prompted the addition of a scenographer, familiar with the staging of narrative, in this case the narrative of the life of a historical character. The result was two generally acclaimed exhibitions that attracted many visitors. Most critics appreciated that art and theatre were brought into the museum, turning the exhibition into an artwork.Footnote80 Mörk’s scenography for Oskuld – Arsenik and Gustaf III challenged the traditional museum exhibition format by placing less focus on the authentic museum objects and more focus on emotion and aesthetics. The critic Ragnhild Prim described Oskuld-Arsenik as an experience in itself, which left you captivated and upset, partly because of Almquist’s life but also because of how it came alive in front of your eyes.Footnote81 Further, she stated that she would not be surprised if Oskuld-Arsenik was the beginning of a new era of exhibition design. In hindsight, we can agree with her prediction. Similar to how scenography works on stage, exhibition design can act as an instrument of focus and association production in a museum exhibition.Footnote82 However, as these two exhibitions show, scenography can do more, since it offers solutions not only to spatial, visual and chorographical dilemmas but also to conceptual ones, helping the museum to invite ambiguity as well as complex emotions.

Notes

1 Elin Nystrand von Unge, Samla samtid: insamlingspraktiker och temporalitet på kulturhistoriska museer i Sverige, Vulkan.se, Diss. Stockholm: Stockholms universitet, 2019, pp. 67–71. The Swedish Exhibition Agency (Riksutställningar) was founded in 1965 and in 1974 an ambitious commission report about Swedish museums was published. (1965 års musei- och utställningssakkunniga, Utställningar [E-Resource] betänkande, Allmänna förl., Stockholm, 1974, http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kb:sou-8350741.)

2 Per Bjurström, “From the Vienna Exhibition to ‘Gustaf III’”, in Abel, Ulf (red.), Det gamla museet och utställningarna: en konstbok från Nationalmuseum, Rabén & Sjögren, Stockholm, 1973, p. 109.

3 Frank den Oudsten, space.time.narrative, Ashgate, Farnham, 2011, p. 1.

4 Margaret Choi Kwan Lam, Scenography as New Ideology in Contemporary Curating and the Notion of Staging in Exhibitions [E-resource], 2015, p. 5.

5 Pamela Howard, What Is Scenography? [E-book], 2nd ed., Routledge, London, 2009, p. 66.

6 Ibid., p. 66.

7 Ibid., p. 80.

8 Rachel Hann, Beyond Scenography [E-book], Routledge, Abingdon, 2019, p. 49.

9 Charnow, Carole, Foreword, in P. McKenna-Cress et al., Creating Exhibitions: Collaboration in the Planning, Development and Design of Innovative Experiences, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2013, p. viii.

10 Astrid von Rosen and Viveka Kjellmer (eds.), Scenography and Art History: Performance Design and Visual Culture, Bloomsbury, London, 2021.

11 Angela Dalle Vacche (ed.), In the Anthology Film, Art, New Media: Museum Without Walls? [E-book], Palgrave Macmillan, Basingstoke, 2012.

12 Klara Arnberg, Orsi Husz, Stockholms universitet, et al. “From the Great Department Store with Love: Window Display and the Transfer of Commercial Knowledge in Early Twentieth-Century Sweden”, History of Retailing and Consumption, Vol. 4, No. 2, 2018, pp. 126–155.

13 Å. Wall, “Vad finns bakom skådespelaren? Sju scenkonstnärer berättar om ‘världens omöjligaste jobb’”, Svenska Dagbladet 1967-05-07.

14 The job title has changed over time, as has the idea of what it includes, moreover the meaning of titles such as scenographer and set designer varies in different national or local contexts. Scenographer was firmly implemented in Swedish theatre practice and the academy already from the late 1960s. In an English-speaking context, however, the word was less successfully introduced in the 1960s referring to an increasingly holistic content of the practice. The various uses and “second adaption” of “scenography” and “scenographer” is further discussed by Rachel Hann in Beyond Scenography (2019). The empirical material used in this article shows a wealth of terms in circulation in the 1960s and 1970s, which reveals a tension between different views of the practice at the time. Mörk worked both a visual artist, window dresser and as a scenographer, which further complicates how we should understand and define his work. I will use the titles “scenographer” and artist/scenographer unless the empirical material (mainly in Swedish) specifically refers to Mörk as an artist (konstnär), theatre decorator (teaterdekoratör) or stage artist (scenkonstnär).

15 Lennart Mörk describes himself as an artist and freelance decorator in 1967. Å. Wall, “Vad finns bakom skådespelaren? Sju scenkonstnärer berättar om ‘världens omöjligaste jobb’”, Svenska Dagbladet 1967-05-07.

16 Å. Wall “Vad finns bakom skådespelaren? Sju scenkonstnärer berättar om ‘världens omöjligaste jobb’”, Svenska Dagbladet 1967-05-07.

17 Ragnar von Holten and Nationalmuseum, “Shakespeare då och nu: John Boydell och the Shakespeare Gallery 1789–1804 – Lennart Mörk och ‘Vintersagan’ på Dramaten 1994”, Volume 576, Stockholm, Nationalmuseum, 1994, Ragnar von Holten, “Lennart Mörks teaterskisser i Nationalmusei teckningssamling”, Bulletin / Nationalmuseum, Vol. 13, No. 3, 1989, pp. 120–129.

18 E.g. Egil Törnqvist, Between Stage and Screen: Ingmar Bergman Directs, 1st ed., Amsterdam University Press, Amsterdam, 1995, Henrik Sjögren, 2002, Lek och raseri: Ingmar Bergmans teater 1938–2002, Carlsson, Stockholm, 2002.

19 Bill Hillier and Kali Tzortzi, “Space Syntax: The Language of Museum Space”, in Macdonald, Sharon (ed.), A Companion to Museum Studies, Wiley-Blackwell, Malden, MA, 2011, p. 282.

20 Skissernas museum, Oförtecknat 4 volymer – Gäddviken – A 224.

21 Elin Nystrand von Unge, Samla samtid: insamlingspraktiker och temporalitet på kulturhistoriska museer i Sverige, Vulkan.se, Diss. Stockholm : Stockholms universitet, 2019, p. 70.

22 Anna-Maria Hagerfors, et al, “Tungt arbete i motvind”, Dagens nyheter, 1972-12-12.

23 1965 års musei- och utställningssakkunniga, Utställningar [E-resource] betänkande, Allmänna förl., Stockholm, 1974, http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:kb:sou-8350741, p. 101.

24 Ibid., p. 102.

25 Ibid., p. 274.

26 Lennart Mörk and Constance af Trolle, Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater, Dansmuseet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 22.

27 Sverker R. Ek, “Bildteater eller totalteater”, in Lennart Mörk, and Constance af Trolle, Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater, Dansmuseet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 28.

28 “Veronica”, “Teaterdekoratör intar museum Lennart Mörk ger Almqvist liv”, Göteborgs handels- och sjöfartstidning, 27, October 1966.

29 Lennart Mörk, and af Constance Trolle, Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater, Dansmuseet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 17.

30 Ibid., p. 9.

31 -Att väcka till liv fantasin hos dessa lärda museimänniskor som gick där och knaprade på sina stenyxor, det var verkligt kul säger Mörk. “Veronica”, “Teaterdekoratör intar museum Lennart Mörk ger Almqvist liv”, Göteborgs handels- och sjöfartstidning, 27, October 1966.

32 “Genom floret kunde man säga att detta var någonting avskilt från de historiska dokumenten, någonting som inte var klar verklighet utan ‘songes’”. Sven Lundvall, P.M. rörande utställningen över C.J.L. Almqvist, 27, January, 1966 Nordiska museets arkiv.

33 Sten C.J.L. Lundvall, “Almqvist i nordiska museet”, in Fataburen: Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok. 1966, Nordiska museet, Stockholm, 1967, p. 112.

34 Howard, 2009, p. 80.

35 Lundvall, 1967, pp. 19–20.

36 “Utställningen skärmar av ett rum och ger med välberäknad dramatisk effekt hela den fantastiska historien i snabba presens-glimtar.” Gerd Reimers, Almqvistutställningen ett konstverk Fylld av fakta och fascinerande ting, Svenska Dagbladet, 1966- 09-16.

37 Sverker R. Ek, “Bildteater eller totalteater?” in Lennart Mörk, and Constance af Trolle (eds), Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater, Dansmuseet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 20.

38 Hann, 2019, p. 134.

39 Sven Lundvall, P.M. rörande utställningen över C.J.L. Almqvist, 27, January, 1966, Nordiska museets arkiv.

40 Dramaten, Arkivet rollboken, https://www.dramaten.se/medverkande/rollboken/Person/1249, accessed 2, July 2019.

41 “För honom har fascinationen inför törnrosdiktaren betytt att han halkat iväg från staffliet in i teaterns och museernas värld.” “Veronica”, “Teaterdekoratör intar museum Lennart Mörk ger Almqvist liv”, Göteborgs handels- och sjöfartstidning, 27, October 1966.

42 den Oudsten, 2011, p. 3.

43 Sten Lundvall, C.J.L. “Almqvist i nordiska museet”, in Fataburen: Nordiska museets och Skansens årsbok. 1966, Nordiska museet, Stockholm, 1967, p. 14.

44 Anon, Almqvist i sitt eget museum, Dagens Nyheter, 1966-09-07.

45 “levande och ändå lättlästa” Hidemark-Stavenow, E., 23 September 1966, Letter to Herr Bengt Dohrn, Nordiska museets arkiv.

46 “Vi får kolossalt mycket beröm för dem och vad mera är, människor läser och läser och de flesta läser alltihop. Bara detta är märkvärdigt och en stor framgång.” Hidemark-Stavenow, E., (23 September 1966) Letter to Herr Bengt Dohrn, Nordiska museets arkiv.

47 “en nervös agressivitet i varje ord”, Hidemark-Stavenow, E., (23 September 1966) Letter to Herr Bengt Dohrn, Nordiska museets arkiv.

48 “Ord som utställningsföremål, föremål som symbol”, Medelius, Hans, Utställningarna, in Medelius, Hans, Nyström, Bengt and Stavenow-Hidemark, Elisabet (ed.), Nordiska museet under 125 år, Nordiska museet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 306.

49 “ … denna nya utställningsteknik, som redan fått många museimän att chockerad knyta näven i byxfickan.” “Veronica”, “Teaterdekoratör intar museum Lennart Mörk ger Almqvist liv”, Göteborgs handels- och sjöfartstidning, 27, October 1966.

50 “ … en ytterst okonventionell och föremålet värdig utställning … ‘Rinman, Sven, Almqvistiana, Göteborgs handel och sjöfartstidning, 5 April, 1967,’ Det känns naturligt att ett av våra mest fascinerande genier skall kunna inspirera till en ovanlig utställning.” Reimers, Gerd, Almqvistutställningen ett konstverk Fylld av fakta och fascinerande ting, Svenska Dagbladet, 16 September, 1966.

51 “ … en idéutställning som är fylld av fakta och fascinerande föremål, kräset valda och dramatiskt arrangerade”, Gerd Reimers, Almqvistutställningen ett konstverk Fylld av fakta och fascinerande ting, Svenska Dagbladet, 1966- 09-16.

52 “ … ge döda grejor en spännande belysning (…)ge liv åt föremålen. Och åt Almqvist.” ”Veronica”, “Teaterdekoratör intar museum Lennart Mörk ger Almqvist liv”, Göteborgs handels- och sjöfartstidning, 27, October 1966.

53 Nationalmuseum can trace its history back to the Kongl. Museum, which was founded in 1792 and opened in 1794, at the Royal Palace. In 1866 Nationalmuseum opened in new premises at Blasieholmen, Stockholm. It is a museum of art and design as well as a government authority working to preserve cultural heritage and promote art. The collections include painting, sculpture, drawings and prints from 1500–1900, as well as applied arts, design and portraits from the middle ages until today.

54 “G III är kontroversiell. För många är han den lille gossen i Hauptbyrån, som egentligen inte angår oss eller som vi bör hålla oss borta ifrån.” Dahlbäck, Bengt, 1971-11-22, Letter adressed to Gustaf Näsström, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

55 “Jag tror fortfarande att sal 1 är helt avgörande för helheten, att man där måste få tillräckligt klara antydningar om det problematiska i kungens karaktär och beteende. Lyckas inte det blir det hela en konst- och kulturhistorisk översikt under Gustaf III:s namn.” Dahlbäck, Bengt 1971-12-21, Gustaf III – Några flikar klarskinn för mina och andras tankar, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

56 Dahlbäck, Bengt, Gustaf III, i Frendel, Yvonne (ed.), Gustaf III: i samverkan med Kungliga biblioteket, Kungliga husgerådskammaren, Kungliga livrustkammaren och Kungliga myntkabinettet: Nationalmuseum, Stockholm 9 november 1972 – 31 mars 1973, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm, 1972, p. 8.

57 Nationalmuseum unsigned letter to Ulf Karlsson at NK, 26 October 1972, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

58 “Uställningens (sic) arkitekt Lennart Mörk binder ihop det hela genom suggestiva bilder och former”, Romdahl, Margareta, Då romantik och upplösning präglade tiden, Dagens nyheter, 1972-11-08.

59 Lennart Mörk, and Constance af Trolle, Lennart Mörk retrospektivt: 40 år i bild och teater, Dansmuseet, Stockholm, 1998, p. 13.

60 “Sakerna har arrangerats av konstnären Lennart Mörk på en fond av lejonfärg, hämtad från de stockholmska husfasaderna och från gustavianernas kinesiska kuriosa.” Bergengren, Kurt, Maskerad för hjärtat, Aftonbladet, 9, November, 1972.

61 “Tvivelsutan hade han dock uttalat sin förvåning över den ‘simpla gout’ Lennart Mörk utvecklat i sin färgsmutsiga och symbolklumpiga scenografi.” Wretholm, Eugen, Utställt – Fyra utstpel kring Hjärter Kung, Vecko-Journalen.

62 “Jag tror fortfarande, att väggens öppnande blir en ny dimension i utställningen”, Dahlbäck Bengt 1971-12-21, Gustaf III – Några flikar klarskinn för mina och andras tankar, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

63 This view was fully restored in the latest renovation of the museum which reopened in 2018.

64 “Utställningen (…) är en iscensättning av de mest dramatiska handlingar och händelser som denna skapande person utförde, upplevde eller själv gestaltade i gränslandet mellan fantasi och verklighet.” Exhibition folder Gustaf III, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

65 “Teatern är det han lever i, en teatermässig utställning”, Levin-Svenson, Carin, undated, Notes, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

66 “Här leker experter fram en tingens och tavlornas teater.” Bergengren, Kurt, Maskerad för hjärtat, Aftonbladet, 9 November 1972.

67 Cramérbaletten, Proposed text for invitation cards, undated, F1a 205, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

68 Signed “Torsten”, Cramerbaletten, undated, F1a 205, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

69 “Den vill undvika det passiva tittandet på enskilda föremål och istället ge en emotionell upplevelse.” Levin-Svenson, Carin, Letter to the press, Exhibition folder Gustaf III, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

70 “Det har blivit en ovanlig utställning, där föremålen mer vill locka till känslomässig upplevelse av Gustaf III:s liv och väsen, än visa ett historiskt förlopp och en historisk miljö”, Exhibition folder Gustaf III, F1a 206, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

71 “Mörk har laddat upp föremålen mot varandra.” Margareta Romdahl, Då romantik och upplösning präglade tiden, Dagens nyheter, 1972-11-08.

72 “ … måste göra allt för att häva känslan av konst utställning – utan återkomma till GIII som (kultur)person.” Lennart Mörk, undated, post stamp 9 July 1972, Letter addressed to Bengt Dahlbäck and Eva Nordenson including sketches for Gustaf III, F1a 205, Nationalmuseums arkiv.

73 In the collections of Nordiska museet.

74 After the exhibition it was in 1976 placed, on suggestion from Bengt Dalbäck, in the new opera building. Mårdh H. Minnet är ett eko-Gustavianska fetischer och återskapade rum. UtställningsEstetiskt Forum [Internet]. 2018;(3).

75 Heléne Lööw, Nazismen i Sverige 1924–1979: pionjärerna, partierna, propagandan, Ordfront, Stockholm, 2004, p. 59.

76 Anon, Nazisternas hyllningskrans åkte i sjön!, Aftonbladet, 20.08.1972.

77 “ … i skepnad av en dekapiterad docka iförd den vita armbindeln på sin uppstoppade häst Kaulbars får rida fram över en röd matta försedd med en demagogisk inskription tycker man dock att arrangörerna tittat väl långt till vänster. Att huvudlösheten helt är på deras sida.” Wretholm, Eugen, Utställt – Fyra utstpel kring Hjärter Kung, Vecko-Journalen.

78 “Utställningens bästa partier är de där Gustaf IIIs politiska avsikter med sitt handlande kommer fram. Idag är det gudskelov endast några få individer på yttersta högerkanten, som känner sig inspirerade av Gustaf IIIs statskupp. Svenska fascister och nazister firade 200-årsdagen av statskuppen vid kungens staty. Där endades (sic) de om att bilda front mot social- och andra demokrater. Här i landet är fascisterna tämligen harmlösa än så länge, men inte längre bort än i sydeuropa är fascistiska statskupper en realitet. Är inte detta något vi borde tänka på, då vi tar ställning till en kung, som genom en kupp skaffade sig diktatorisk makt?” Hans Hjälte, “Till minne av en statskupp?”, Skogsindustriarbetaren, 1972, No 24, p. 21.

79 “Det är ändå föremålens egen kraft som ska verka på åskådarens inlevelse och kunskapsförmåga.” Bergengren, Kurt, Maskerad för hjärtat, Aftonbladet, 9 November, 1972.

80 “ … en utställning som i sig är ett konstverk.” Gerd Reimers, Almqvistutställningen ett konstverk Fylld av fakta och fascinerande ting, Svenska Dagbladet, 16 September 1966.

81 “Utställningen är i sig själv en upplevelse och det skulle inte förvåna om den kom att bilda inledningen till en ny epok i utställningsteknikens historia. Man går där fängslad och upprörd, inte bara över det livsöde som skildras utan väl så mycket över sättet på vilket detta öde blir levande inför ens ögon.” Ragnhild Prim, Fascinerande och dramatiskt om Love Almqvist, Medborgaren, 1966-10-12.

82 “Scenografin fungerar som fokuseringsinstrument och associationsapparat.” Astrid von Rosen, Knut Ströms scenografi och bildvärld: visualisering i tid och rum, Acta universitatis Gothoburgensis, Diss. Göteborg: Göteborgs universitet, 2010, Göteborg, 2010, p. 15.