Summary

This study examines painted copies from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to gain a richer understanding of the phenomenon of copies and of copying as a common artistic practice. The study findings suggest that copies painted in Sweden in the seventeenth century were, in general, free copies. In that century, the Swedish economy was booming, and a semi-regulated art market had developed, and many of the paintings commissioned by the monarchy and nobility were copies of portraits. This phenomenon is analysed here in light of the new iconology and its focus on image circulation and transformation in and between different media, as well as regarding the increasing interest in the last decades in pre-modern copies within art history and visual studies. Special attention is given to the portraits of Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa) from 1528, the free copies of her portrait made in the seventeenth century and the copy of The Sun Dog Painting from 1636. Three known portrait multiples are known of Margareta Eriksdotter, and they are thought likely to represent part of the same commission and to have been painted in Lübeck in 1528 by Hans Kemmer, a student of Lucas Cranach the Elder. The phenomenon of free copies painted in the seventeenth century is interpreted as combining artistic alterations and improvements, while the visual content that was considered significant for preservation from the previous image had to be copied faithfully.

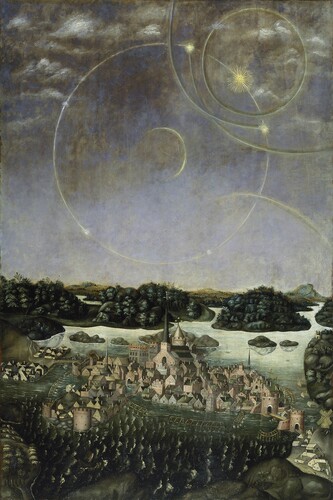

One of the earliest pictures painted in Sweden is believed to be the so-called Vädersolstavlan, or ‘The Sun Dog Painting’, depicting a halo phenomenon observed in the sky above Stockholm on 20 April 1535. At the time, this unexpected and rare phenomenon was considered an astrological sign with eschatological meanings, and the painting’s purpose was to serve as a visual documentation and memory for the future. It has been attributed to a painter known as Urban Målare (‘Urban [the] Painter’), who is the only painter known to have been active in Stockholm in the late 1530s. However, although The Sun Dog Painting is best-known today as part of a chronological narrative about Swedish art history, as well as the first depiction of Stockholm, the original painting no longer exists. It was most likely eliminated in 1636 after it had been copied in the same year by the painter Jacob Heinrich Elbfas on commission from the parish of the Church of St. Nicholas in Stockholm.Footnote1 Previously, the original picture had been on display in the Church of St. Nicholas since at least 1608.Footnote2 The copy from 1636 that replaced the earlier picture has remained on display in the same church ever since. However, whether The Sun Dog Painting was a sixteenth-century original or a later copy was unknown until a dendrochronological analysis of the panel was made in 1998. The year of origin of the first painting was further complicated: Peter Gillgren has suggested that the composition of The Sun Dog Painting could partly be a montage constructed from different recycled motifs. Gillgren has explained that the sun dogs in the painting closely resemble a printed woodcut of a halo found in the scholar Olaus Magnus’s book from 1555 that, in English, translates as A Description of the Nordic Peoples.Footnote3 If the halo was copied from A Description of the Nordic Peoples, that would indicate that the first picture was made sometime after 1555. Either way, no written documentation of this picture, such as some documentation of it being commissioned, exists before 1608.

This study examines painted copies made in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries to gain a richer understanding of the phenomenon of copies and of copying as a common artistic practice. In the last few decades, there has been an increasing interest within art history and visual studies on pre-modern copies.Footnote4 The motivations behind this interest are many and span from adding historical perspectives on the topic of Walter Benjamin’s famous essay, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility’ (1936) to the many attempts made in postmodern and contemporary art to deconstruct the notion of unique artworks.Footnote5 Two central theoretical references for this study are the new iconology represented by, among others, W.J.T. Mitchell, and the massive interest in Aby Warburg in the last decades, as well as the turn towards materiality and the analytical potential of considering art works as objects represented by, among others, Michael Yonan.Footnote6 Mitchell explains the difference between an image and a picture in the sense that ‘you can hang a picture, but you can’t hang an image’, and following this distinction between pictures as material objects and images as immaterial entities, ‘painted copies’ are pictures.Footnote7 A painted copy is thus the material support of an image that has been replicated or paraphrased. Studying copies is equivalent to studying the history of moving images, as circulating, migrating, and replicating entities travelling across media, time, and borders.Footnote8

The term ‘copy’ is primarily useful as an art-historical, overarching blanket term but is, by itself, analytically insufficient without also considering media specificity and different kinds of pre-modern copies. It is also important to distinguish between etymology and art-historical terminologies for terms such as ‘copy’, ‘fake’, ‘forgery’, ‘replica’ and ‘original’. Some of these words used today were not used in pre-modern times or had other meanings from those they have come to have in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, and they also bear modern connotations that are anachronistic to the time of study.Footnote9 However, the concepts that these words have come to represent in modern times began to take shape in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. To distinguish the different kinds of painted copies made in the early modern period, Ariane Mensger has proposed the use of the terms ‘replicas’, ‘free copies’, and ‘exact copies’. Replicas are faithfully duplicated images made not long after the first image, most probably by the same individual artist or by an apprentice or assistant working at the same workshop where the first image was made. The term ‘free copies’ describes images where the purpose seems not to have been to copy the previous image in its entirety as precise as possible. Instead, creative alterations and additions have been made. Parts of the first image might have been copied closely, while other parts might have been excluded or subjected to interpretation, so that, for instance, new iconography or stylistic characteristics can be added to the rendering. Most copies from the early modern period were free copies. Mensgers’ third categorisation of ‘exact copies’, however, reflects the expectations raised with the advent of photography—copies so identical to the original that they cannot be distinguished using the naked eye and would therefore take a technical analysis to determine which painting was made first.Footnote10

From the sixteenth century onwards, successful artists who were active in the artistic centres of Europe, such as Albrecht Dürer and Hieronymus Bosch, were copied by other artists during and after their lifetimes.Footnote11 The making of copies and forgeries after a few praised artists who had gained a strong brand followed an increasing market demand combined with a lack of supply of originals during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote12 The difference between a copy and a forgery is a question of context and intent. Besides an evolving open market, where paintings were made for assumed buyers and without the need for pre-existing, agreed-upon commissions, forgeries also presuppose an accelerated appreciation of artists’ authorship as well as a concept of artistic copyright. It is when copying is considered a problem or even criminalised, and when the making of a copy is motivated by a malicious intent, that it becomes a forgery.Footnote13 However, these reasons behind making a copy had not yet reached Sweden in the early seventeenth century. There is no reason to believe that anyone in the parish of the Church of St. Nicholas considered it important who the painter of the original picture had been – the only artist who was acknowledged for his achievement was Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, the painter of the copy. His name is mentioned in the archival holdings of the parish from 1636, where the commission of the copy was described as that ‘he [Elbfas] has renewed the picture upon which is depicted the sign on the sky that was visible one hundred years ago’.Footnote14 Elbfas was born in the historical region of Livonia, trained in Strasbourg and active in Stockholm as a painter from c. 1628 until his death in 1664. He was also Alderman of the painters’ guild in Stockholm from 1628, six years after it was founded, until his death in 1664. From 1634 until the 1640s, he received commissions from Queen Maria Eleonora and from the court, and in a poem from 1639 (the first example of an artists’ biography written in Sweden), he was praised for his accomplishments as a portrait painter.Footnote15 This made him one of the most successful painters in Sweden in the first half of the seventeenth century.

Christopher Wood and Alexander Nagel have suggested a theory of substitutability to understand the production and reception of copies in pre-modern times.Footnote16 Wood have also developed this hypothesis further in his Forgery, Replica, Fiction (2008).Footnote17 The theory of substitution explains how people in late medieval and early modern Germany thought about time, the past, the present, artworks and authenticity. A model of substitution explains how one artefact could easily stand in for another artefact, provided that it was trusted to transmit the content intact. A newly-made copy could substitute an artefact made in the past, provided that the copy was perceived to communicate the same meaning. In terms of temporality and the fifteenth- and sixteenth-century way of thinking about the past and the present, a later copy could thus be considered as authentic and authoritative as the first picture if it pointed back to the same origin as the original artefact.Footnote18 Following Wood’s substitutional model to understand the making and historical reception of the copy of The Sun Dog Painting in 1636, the purpose of the image was to refer back to a specific event when an omen in the form of strange signs in the sky had been observed in 20 April 1535. A copy of The Sun Dog Painting was commissioned to substitute the first picture. According to this way of thinking, throwing away the earlier picture after it had been substituted and replaced with a new copy was nothing more than a ‘renewal’ of the picture—which is also how the commission of the copy was described in 1636. Even if the previous picture was replaced with a new one, the original image had still been preserved in the copy.

Repeated images

Copies behave like chameleons. They blend in and adapt so well to the narratives of art history they are inserted in that they are barely visible, but look closer and they are there. Little would be known about painting in Sweden in the sixteenth century if it was not for preserved copies made in the seventeenth century. The Sun Dog Painting is a case in point. There are a handful of portraits known to have been painted in the sixteenth century, but most of them are now gone. Their likenesses, however, are preserved through copies. Among them are a portrait copy attributed to Cornelius Arendtz from the 1620s depicting King Gustav I (1496–1560) where the lost original is believed to have been painted around 1558, and a portrait copy of the nobleman Nils Sture (1543–1567) painted sometime at the beginning of the seventeenth century ().Footnote19 Together, they testify to the increased demand for copies in the seventeenth century.

Fig. 1. Jacob Heinrich Elbfas, The Sun Dog Painting, 1636. Copy after a lost original. Oil on panel, 163 × 110 cm. Church of St. Nicholas, Stockholm. Photo: Mats Halldin.

Fig. 2. Cornelius Arendtz, Gustav I, 1620s. Copy after a lost original from the sixteenth century. Oil on canvas, 100 × 74 cm. Private collection. Photo: Nordiska museet.

Fig. 3. Unknown artist, Nils Sture (1543–1567), seventeenth century. Copy after a lost original from the sixteenth century. Oil on canvas, 112 × 94 cm. Nationalmuseum. Photo: Erik Cornelius / Nationalmuseum.

My hypothesis is that copies painted in Sweden in the seventeenth century were, in general, free copies. This hypothesis will be tested by comparing and examining the portraits and portrait copies of Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), sister to King Gustav I of Sweden, since all the copies refer to the same image prototype but were painted on different occasions and by different painters. The following comparison considers the three nearly identical portraits known to exist. According to the coat of arms, and the Latin text on both sides of the woman in the image, the identity of the sitter is Margareta Eriksdotter, and the portrait was painted in 1528. The provenance of any of these portraits regarding origin, ownership and whereabouts could not be traced back to the sixteenth century. One of them can be traced back to the late seventeenth century and the inventories of Bystad manor in the province of Närke in Sweden. Today it is kept in a private collection.Footnote20 () Another one is part of the Swedish National Portrait Collection and has been on display at Gripsholm Castle in the province of Södermanland since 1822, when it was donated as a gift from the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities.Footnote21 () The Royal Academy of Letters acquired the portrait in 1770, but where it had been before then is unknown.Footnote22 The Gripsholm portrait is the most well-known and the one usually reproduced and referred to in textbooks and other contexts. The third portrait has been in the collections of Nationalmuseum since 1872, when the State bought it from the estate of King Charles XV after his death.Footnote23 () Charles XV, in his reign, had brought the portrait to Ulriksdal Palace as part of his collections, but that is as far back in history that the life of this portrait can be traced.Footnote24

Fig. 4. Attributed in this article to Hans Kemmer, Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), ca. 1528. Oil on panel, 67 × 48 cm. Private collection. Photo: Sofie Eriksson.

Fig. 5. Attributed in this article to Hans Kemmer, Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), ca. 1528. Oil on oak panel, 68 × 47 cm. The Swedish National Portrait Collection. Photo: Nationalmuseum.

Fig. 6. Attributed in this article to Hans Kemmer, Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), ca. 1528. Oil on oak panel, 64 × 43.5 cm. Nationalmuseum. Photo: Erik Cornelius / Nationalmuseum.

In the three portraits, Margareta Eriksdotter is depicted wearing jewellery, an extravagant dress and a hat decorated with gold, lace, and swansdown. The flat, black background enhances the luxurious impression of the outfit.Footnote25 The details that differ between the portraits are not easy to recognise at first sight. They are all painted in oil on rectangular panels, and the length and width of the panels are also very similar. Both and have undergone dendrochronological examinations showing that both panels are made of oak, but in neither case has the wood been possible to date.Footnote26 A visual comparison between them easily becomes a ‘spot the difference’ game. The golden tassels hanging from the swansdown decorating the hat in and are missing in , while the small pearls hanging from the tight necklace in and are missing in . Whether these details are alterations that have been added or erased alongside restorations at some point is hard to tell, except for the interlocked fingers in . They were repainted as part of a restoration of the picture around 1955; previously the three left-hand fingers were depicted in parallel as in the two other portraits.Footnote27 The restoration in the 1950s seem to have been quite far-reaching, which would explain why the style of for instance the face looks a bit more perfect and idealised than in the other two images. Overall, and are especially hard to distinguish – the colour of the paint, brushstrokes, the shape of the ear, the shadows under the eyes and the style of the letters look nearly identical.

There is a danger in falling into a default mode of enquiry and need to label one of these portraits as ‘the original’ and the rest as ‘copies’, because it builds upon the assumption that there had to be a distance in time between when they were made, and that the first portrait was copied later by other painters. There are no written sources that either support or contradict this since no letters of commission for the portrait of Margareta Eriksdotter from 1528 (or earlier) exist.Footnote28 Neither are there any other known commissions for copies of a portrait of Eriksdotter from the sixteenth century. This portrait’s ‘original’ has sometimes been attributed to a painter – Hillebrandt – about whom nothing is known except that he was active in Stockholm in 1528. However, Eriksdotter could not have met Hillebrandt in Stockholm in 1528 since it is documented that she and her husband, Count Johann von Hoya, spent most of their time in Lübeck that year, so although this attribution has been repeated until today, it is most probably incorrect.Footnote29 Lübeck had been an artistic centre for altarpieces, but the Reformation changed this completely, and in 1528 there were only two painters active in Lübeck who could have painted Eriksdotter’s likeness. One of them was Jacob von Utrecht, the only painter known to have painted portraits in the 1520s until he probably passed away in 1530. The other option would be the painter Hans Kemmer, a follower of Lucas Cranach the Elder, who also had been a student and assistant at Cranach’s workshop in Wittenberg before moving to Lübeck.Footnote30 Only religious paintings are known to have been made by Kemmer in the 1520s – the first portraits known to have been painted by him are from 1534.Footnote31 Nevertheless, I would like to attribute all three portraits to Hans Kemmer and suggest that they were all painted around 1528 and part of the same commission, based on the observation that these portraits are stylistically similar to other paintings by Kemmer and less elaborated, detailed and in different format than the typical half-figure portraits, with resting hands on tables in the foreground, that van Utrecht painted in the 1520s. This attribution has previously been suggested by Margareta von Ajkay in an unpublished bachelor thesis from 1971, but only for one of the portraits () that she considered to be the original. Based upon the notion that only single paintings should be labelled as originals, the other two were assumed to be later sixteenth-century copies by unknown painters.Footnote32

The portraits are painted in the style of Cranach, which, of course, also reinforces the supposition that they are workshop replicas painted by Cranach’s student, Kemmer. The workshop model for learning the profession was based on the adoption of the master’s painting methods by his students, which would also explain why the three portraits look so similar. Cranach’s workshop is well known for its voluminous production of paintings characterised by recycling of motifs and standardised formats. In Cranach’s workshop, several kinds of replication techniques to speed up the working procedures were also practiced, such as the use of stencils.Footnote33 Examples of this are the many nearly identical portraits of Martin Luther from Cranach’s workshop, which would not have been possible without the help of stencils. Great formal correspondence is evident between the linear contours in the portraits of Eriksdotter, making it unlikely that they were copied freehand; rather, Kemmer likely used stencils, the same drawing, or both. There are also other known instances of where Kemmer is known to have painted repetitions, variations, and versions of an already existing design, which of course also supports the claim presented here that were all painted by Kemmer as part of the same commission.Footnote34 Moreover, with a few exceptions all pictures known to have been painted by Kemmer after moving from Wittenberg to Lübeck in 1522 were painted on the same type of material support (oak panel) as and (and probably as well, even though the type of wood in the panel has not been examined).Footnote35

The most important observation to be made here is not technical or stylistic but conceptual, even though it is aided by formal analysis. Enquiries into resemblance and which of these portraits was made first is less interesting than the observation that they have been made with the intention to look as identical as possible. Marion Heisterberg, Susanne Müller-Bechtel and Antonia Putzger have proposed describing these types of copies as ‘faithful copies’, because, to paraphrase W.J.T. Mitchell’s question, ‘What do images want?’, they consider the primary objective of a faithful copy as to create nothing new.Footnote36 Regardless of the painter’s individual artistic and technical accomplishment, the intention was to achieve faithful resemblance and repeat the image according to the prototype and without any creative alterations. This purpose is historically more interesting than how well they achieved it. The portraits of Eriksdotter could also be described as ‘multiples’, a term suggested by Walter Cupperi instead of ‘copies’ to avoid the modern, cultural connotations that accompany the term ‘copy’ when they do not correspond to the historical circumstances in which they were made. The term ‘multiple’ is helpful since it instead points to a non-hierarchical, horizontal relationship between undifferentiated, artistically executed artefacts.Footnote37 It is also historically more accurate to describe this type of serially made portraits as multiples since it emphasises that the commissioner and historical beholders of these portraits did not care about which picture was made first. The dichotomy between original and copy is a mode of anachronistic thinking for paintings during this time and in this geographical area. In fact, assuming that the three portraits of Eriksdotter were painted within a short period and in the same workshop, it would make more sense to label all three originals.

A question left unresolved is why at least three closely associated portraits of Margareta Eriksdotter were made, whereas no pendant portraits are known of her husband Johann von Hoya. The couple resided in the town of Vyborg (today in Russia, but in the sixteenth century a part of Sweden), and it would have made more sense that they would have seized the opportunity of commissioning both their portraits while in Lübeck in 1528.

It has been suggested that the identity of the sitter could not be Eriksdotter. If so, the argument presented here would not hold. However, in the inventory of her estate written after her death in 1548 are listed garments, jewellery and a hat that from the description matches that depicted in the portraits.Footnote38 In the 1570s, the head and chest in the first portrait was copied onto the wooden panelling of the wall of a room at Rydboholm Castle, close to Stockholm.Footnote39 The wall painting is a copy of the head in the first image and was made as part of a small portrait gallery in memory of Vasa ancestors, proving that half a century later the portrait(s) from 1528 were known as depicting Eriksdotter. Moreover, many of the paintings by Kemmer have Latin or German texts as part of the motif. In several of his other paintings, the texts are stylistically very similar to the text on the portraits. The possibility that this text would be a later, and possibly incorrect, addition therefore seems unlikely.

Free copies made in the seventeenth century

Free copies are copies that are usually made later than the first image and by another artist – there is a distance in time and place between them and the first image. Contrary to faithful copies and multiples, they do not strive to repeat the exact design, content and subject matter – format and materiality can differ, and some parts of the motif can be copied more closely, while other parts can be removed, added or changed.Footnote40 At least six free copies of the portrait of Margareta Eriksdotter exist.Footnote41 In the following, two of them will be analysed further, as they are also generally representative of the many copies of portraits made in Sweden in the seventeenth century.

The seventeenth century was an important period of transition in Europe towards a modern concept of art, and the status of painters rose gradually from artisans to artists.Footnote42 This transition can be traced in Sweden as well, as the economy was booming following Sweden’s success in the Thirty Years’ War. Artists like Elbfas, who saw promising career opportunities, immigrated to Sweden from other Northern European countries, and a semi-regulated market for art was established.Footnote43

Queen Hedwig Eleonora and queen Christina were both important patrons for art and architecture, and with David Klöcker Ehrenstrahl, the kingdom got a court painter who embodied a new, modern concept of the artist.Footnote44

Portrait galleries also came into vogue. The monarchy and nobility had become wealthy from the constant warfare, and they wanted to decorate the walls of their residences with portraits of themselves, their ancestors and (to prove their loyalty) portraits of members of the Swedish monarchy, past and present. With this increased demand for portraits, there followed an increased production of copies, even though they were not conceived as copies then. To list some examples, in 1649, Count Magnus Gabriel De La Gardie commissioned 27 full-length portraits of Swedish royalty and members of the nobility from Elbfas, and, in 1667, Queen Hedwig Eleonora commissioned 29 full-length portrait copies of sixteenth-century rulers from the painter David Frumerie to form a portrait gallery at Gripsholm Castle.Footnote45 The purpose of commissions like this was to serve functional and representative purposes by instigating a series of likenesses, which could be achieved by copying the likeness from earlier portraits. Since the portraits had to conform to a sameness in size and style, format and poses could be altered, and bodies, clothing, iconography and setting added (which would be needed if, for example, the copy of a half-figure portrait had to be a full-figure portrait).

The documented provenance of the first painting under analysis () begins in the nineteenth century with the Swedish collector Christian Hammer. Hammer must have bought the painting for a never-to-be-realised national museum of art and antiquities. After Hammer had given up on his museum dreams, the painting, together with the rest of his collections, was sold at an auction in Cologne in 1893, only to be brought back to Sweden to be included in the collections of the Nordiska Museet in Stockholm.Footnote46 Judging from the style, however, the portrait was very likely painted in the first half of the seventeenth century. The portrait is painted with a standard iconographical and stylistic repertoire characteristic of most portraits painted in Sweden during this time. This repertoire usually comprised one or two draperies with fringes that seem to be hanging from the top of the painting (rather than being part of the interior of the same room as the depicted subject), chequered flooring and a table drawn at an odd, ‘flat’ angle covered with a tablecloth in either the same or a matching colour as the hanging drapery. Additional props or iconography were also sometimes included.

Fig. 7. Unknown painter, Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), seventeenth century. Oil on canvas, 200 × 115 cm. Nordiska museet. Photo: Peter Segemark / Nordiska museet.

The second painting () was also painted as part of a larger commission for a series of portraits, probably sometime in the 1630s or 1640s. In this case, the identity of the painter is known. Johan Johansson Werner Jägerdorfer (the Elder) was probably born around 1600 in the historical region of Silesia and immigrated to Vadstena in Sweden to work as a painter until his death in 1656. He and his son, Johan Werner, painted many portraits and copies of portraits on commission for Count Per Brahe who resided at Visingsborg Castle, not far from Vadstena.Footnote47 In fact, portraits of Margareta Eriksdotter are listed in the inventories of several Swedish castles owned by members of the Brahe family in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Eriksdotter had been married to Joakim Brahe in her first marriage and, through their son Per Brahe the Elder, she was considered an important ancestor for the Brahe family, which also explains why copies of her portrait were commissioned after her death.Footnote48

Fig. 8. Johan Johansson Werner Jägerdorfer, Margareta Eriksdotter (Vasa), 1630–40s. Oil on canvas, 199 × 132 cm. Nordiska museet. Photo: Nationalmuseum.

Pictures painted in Sweden during the seventeenth century were, in general, unsigned; consequently, many of the portraits in Swedish collections painted in the style described above have traditionally been attributed to Jacob Heinrich Elbfas or a so-called ‘school of Elbfas’. ‘The school of Elbfas’ has sometimes served as an umbrella term for many unsigned portraits from the seventeenth century where the artist has been unknown but, judging from the style, it would nevertheless be likely that was painted by him, and possibly also part of the above-mentioned commission by Magnus Gabriel de la Gardie. The two portraits analysed here have in common that the painters have copied the likeness of Margareta Eriksdotter – they repeat the three-quarter profile of the head, the facial features, the hair parted in the middle, the wide hat, the jewellery, and the white collar. The painter of has also copied the pose with the folded hands and more of the garment. The substitutional mode of thinking came into expression to preserve the likeness of the individual in the portrait, by copying the facial features, hair, and to some extent the style of her clothing. These were the prioritised aspects of the previous picture that needed to be copied more closely for the new portrait to be accepted as representing Eriksdotter. This was how the authority of the new portraits was guaranteed. However, in neither of these portraits is the likeness copied exactly. The main reason for this was probably that this was not considered important for the commissioners, the painters or any of those that these portraits were painted for to see. In contrast, the creative paraphrasing combined with modern, baroque props such as the draperies, the baroque clock and classicist square column in , the modern updates of the dresses in both portraits and the softening of the unrealistic triangular body-shape were probably perceived and valued as artistic improvements compared with the style of the older portraits. The outfits in the seventeenth-century copies are combinations of fashionable clothing and jewellery, both of that period and historic. For a seventeenth-century beholder, the outfits must have been perceived as quite peculiar creations, without equivalence in their reality. The long shirtsleeves copied in were not in fashion in the seventeenth century, and neither was the wide hat. However, besides representing the sitter, these attributes helped to estrange the seventeenth-century beholder from the individual in the image, to entice the historical imagination and to establish a difference between the present and the past.

Conclusions

The making of copies in the early modern period needs to be treated as an independent phenomenon, and there are many art histories left to be written if copies are treated as expressions of the historical context in which they were made. The copy of The Sun Dog Painting was painted in 1636, and regardless of whether the original picture was already made in 1535 or much later, the fact that the parish of the Church of St. Nicholas commissioned a copy testifies to an emerging historical consciousness at the beginning of the seventeenth century. Notably, whereas the elite in the society principally expressed a historical interest in genealogy and how their lineage could be traced back in time, the purpose of The Sun Dog Painting – both the original picture and the copy – was to serve the collective memory of the parish members. Contrary to portraits of the societal elite, the image represented an event in the town’s history, so it probably contributed to a sense of community for church visitors. It was visual evidence that a halo phenomenon had been seen in the sky above Stockholm in 1535. This is the meaning that had to be preserved and transferred to the new picture by copying the key features of the image, just as the purpose of the free copies of portraits examined here was to preserve the likeness of Margareta Eriksdotter. Since the original picture of The Sun Dog Painting is now lost, a side-by-side comparison to judge if the copy from 1636 is an exact copy or a free copy is not possible. However, based on what is known about the production of other copies in Sweden in the seventeenth century, the primary objective would have then been to closely copy the sun dogs, and to copy the image of Stockholm so that the parish members could recognise the town as theirs. In a close visual analysis of The Sun Dog Painting, archaeologist Margareta Hallerdt has been able to identify some of the depicted buildings and structures in the image as likely being realistic depictions of how they are believed to have looked in 1535.Footnote49

As mentioned at the beginning of this article, Peter Gillgren has reason to question whether the original painting was not made as early as 1535. Nevertheless, enough of the cityscape specific to the sixteenth-century landscape is depicted in The Sun Dog Painting to indicate that at least these parts were copied closely. For the copy of The Sun Dog Painting to hold authority as a replacement of the previous painting that had been hanging in the same church, the parish members needed to recognise a resemblance between them. This does not exclude the possibility that Elbfas chose to improve the image by updating the style, altering the composition and adding details and a background to his version, but the visual content considered to represent the message of the image needed to be copied faithfully.

Copying practices for producing multiples, such as the use of stencils, as well as techniques for transferring an image from one surface to another, such as pouncing or the use of grids, were extensively used in the commercial art centres in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries.Footnote50 This study argues that the three portrait multiples of Eriksdotter were all part of the same commission and painted in Lübeck around the year 1528 by Hans Kemmer, probably by using replication techniques he had learned as a journeyman in the workshop of his master, Lucas Cranach the Elder. Previous studies on ‘the original portrait’ of Eriksdotter followed the conventional art-historical path of analysing the content and meaning of a single image, thus overlooking that there are three distinct pictures. Methodologically speaking, recognising this plurality also generates new knowledge about the historical context in which they were made. The main reasons for striving for close formal correspondence and for creating exact copies were tied to specific phenomena – such as the emergence of a new concept of art and artistic authorship and effective serial production motivated by commercial purposes.Footnote51

For Sweden in the seventeenth century, however, an artistic semi-periphery without painters commercially successful enough to be copied for their ‘brand’, artistic creativity and stylistic novelty came into expression in the making of free copies. The design of the seventeenth-century copies treated here was probably created by freehand drawing, which should not be interpreted negatively as a lack of technical knowledge and skill, but rather that creative interpretation and paraphrasing in the making of copies could offer a possibility for painters to add improvements. Simultaneously, creativity regarding new additions and alterations of some parts of the motifs had to be negotiated with a growing concern for historical authenticity as the significant visual content of the first image had to be faithfully copied to the new image.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 John Rothlind, “Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan: Konservering och teknisk analys”, Sankt Eriks Årsbok, Stockholm, 1999. On The Sun Dog Painting, see also Peter Gillgren, Vasarenässansen: Konst och identitet i 1500-talets Sverige, Stockholm, 2009, pp. 170–182 and Margareta Weidhagen-Hallerdt, “Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan: Analys av stadsbild och bebyggelse”; Andrea Hermelin, “Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan: En målning i reformationens tjänst. Historik enligt skriftliga källor”; Jan Svanberg, “Vädersolstavlan i Storkyrkan: Det konsthistoriska sammanhanget”, all in Sankt Eriks Årsbok, Stockholm, 1999.

2 The original was first mentioned in Sigfrid Arno Forsius, Een liten underwijsning, Stockholm, 1608.

3 Gillgren, 2009, pp. 173, 178–179; Olaus Magnus, Historia de gentibus septentrionalibus, Rome, 1555.

4 Maddalena Bellavitis (ed.), Making Copies in European Art, 1400–1600: Shifting Tastes, Modes of Transmission, and Changing Contexts, Leiden, 2018; Marion Heisterberg, Susanne Müller-Bechtel & Antonia Putzger (eds.), Nichts neues schaffen: Perspektiven auf die treue Kopie 1300–1900, Berlin/Boston, 2018; Walter Cupperi (ed.), Multiples in Pre-Modern Art, Zürich-Berlin, 2014; Markwart Herzog et al. (eds.), Fälschung – Plagiat – Kopie: Künstlerische Praktiken in der Vormoderne, Petersberg, 2014; Andrea Bubenik, Reframing Albrecht Dürer: The Appropriation of Art, 1528– 1700, Farnham, 2013; Ariane Mensger, “Die exakte Kopie Oder: die Geburt des Künstlers im Zeitalter seiner Reproduzierbarkeit”, Nederlands kunsthistorisch jaarboek, Vol. 59, 2009; Tatjana Bartsch et al. (eds.), Das Originale der Kopie: Kopien als Produkte und Medien der Transformation von Antike, Berlin, 2010; David Ganz & Felix Thürlemann (eds.), Das Bild im Plural. Mehrteilige Bildformen zwischen Mittelalter und Gegenwart, Berlin, 2010; Wolfgang Augustyn & Ulrich Söding (eds.), Original – Kopie – Zitat. Kunstwerke des Mittelalters und der Frühen Neuzeit: Wege der Aneignung – Formen der Überlieferung, Passau, 2010; Christopher S. Wood, Forgery, Replica, Fiction: Temporalities of German Renaissance Art, Chicago, 2008.

5 For a recent English translation, see Walter Benjamin, The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, Cambridge, 2008.

6 Andreas Beyer et al. (eds.), Bilderfahrzeuge: Aby Warburgs Vermächtnis und die Zukunft der Ikonologie, Berlin, 2018; W. J. T. Mitchell, Image Science: Iconology, Visual Culture, and Media Aesthetics, Chicago, 2015; Michael Yonan, “Technical Art History and the Art Historical Thing”, Materia: Journal of Technical Art History, Vol. 1, No. 1, 2021.

7 Mitchell, 2015, p. 16.

8 See Chapter 4, “Migrating Images”, in Mitchell, 2015.

9 On the etymology and art historical terminologies of copies (and the related term original), see Wolfgang Augustyn & Ulrich Söding, “Original – Kopie – Zitat. Versuch einer begrifflichen Annäherung”, in Augustyn & Söding (eds.), 2010.

10 Mensger, 2009, pp. 197–198. As a comparison, Andrea Bubenik has suggested the term ‘appropriation’, which is close to the meaning of what Mensger terms ‘free copies’, with the difference that ‘appropriation’ indicates an interest by the copyist to compete with or to pay an artistic homage to the artist behind the original design. See Bubenik, 2013, p. 2. Even though the term ‘free copy’ might be based more on formal qualities, it has the advantage that it is not related to artistic intentions.

11 Christine Göttler, “Die Fruchtbarkeit der Bilder: Kopieren nach Dürer um 1600”, Kulturwissenschaftliche Zeitschrift, Vol. 4, No. 3, 2019; Nils Büttner, “Fälschung. Plagiat und Kopie nach – Hieronymus Bosch”, in Herzog et al. (eds.), 2014; Bubenik, 2013.

12 See for instance Maria H. Loh, “Originals, Reproductions, and a ‘particular taste’ for Pastiche in the Seventeenth-Century Republic of Painting”, in Neil De Marchi & Hans J. van Miegroet, Mapping Markets for Paintings in Europe, 1450–1750, Turnhout, 2006.

13 On pre-modern forgeries, see Herzog et al. (eds.), 2014; Wood, 2008, pp. 109–184; Alexander Nagel & Christopher S. Wood, “Toward a New Model of Renaissance Anachronism”, The Art Bulletin, Vol. 87, No. 3, 2005, p. 413.

14 ‘renoverat anno 1636’, ‘han [Elbfas] hafuer förnyat den taffla huar upå ståår thet himmelsteckn som syntes för hundrade Åhr sedann’, see Rothlind, 1999, pp. 8, 15.

15 ‘Elbfas, Jacob Heinrich’, 1953; Petrus Pachius, Missus, Miscellanea, Epithalamia, Epigrammata, Anagrammata, Epicedia, alia item, Missus 87, Stockholm, 1639. On the Painters’ Guild in Stockholm, see Jan Brunius, ‘Stockholms målareämbete intill 1700-talets mitt’, RIG, Vol. 48, 1965, pp. 171–184.

16 Nagel & Wood, 2005, p. 413; Alexander Nagel & Christopher S. Wood, Anachronic Renaissance, New York, 2010, pp. 29–34.

17 Wood, 2008.

18 Wood, 2008, pp. 15–24, 32–42, 51–59.

19 Gillgren, 2009, pp. 64–66; Karl Erik Steneberg, “Den äldsta traditionen inom svenskt porträttmåleri”, Årsbok 1934, Vetenskapssocieteten i Lund, Lund, 1934, pp. 104–106.

20 Margareta von Ajkay, “Margareta Vasas porträtt: Ikonografi”, Stockholm University, 1971, p. 29, n. 71.

21 Minutes of meeting from the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities, 5 November 1822, The Antiquarian-Topographical Archives, Swedish National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet), Stockholm.

22 Inventory 1599–1801 from the Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History, and Antiquities, The Antiquarian-Topographical Archives, Swedish National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet), Stockholm.

23 According to catalogue entry for this portrait (inventory number NMGrh 451) published at Nationalmuseum’s website, www.nationalmuseum.se, accessed 30 June 2021.

24 Gustaf Upmark, Konung Carl XV:s tafvelsamling: Beskrivande förteckning, Stockholm, 1882, p. 90.

25 The Latin text is ‘IMAGO NOBILISSIME PIE AC VENE ROSE DNE DOMINE MARGARETE FILIE NOBILITATIS AC EQVITIS AV RATI ERICI IOHANNIS QVE SVB HONESTO TITVLO VIXIT RYBOHOLM ET DEPICTA EST HÆC MEMORIA ANNO ETC. 1528’, which in translation would mean ‘Image of the noble, pious, and honored Lady Margareta, daughter of the noble knight Erik Johansson who has lived a respectable life at Ryboholm and was painted in memory 1528.’

26 A dendrochronological analysis of Fig. 5 was performed in 1998 and of Fig. 6 in 2000 for Nationalmuseum by the Institute of Wood Science at the University of Hamburg. Documentation available online at Netherlands Institute for Art History (RKD) technical database, www.rkd.nl/en/, entry ‘Master Hillebrandt’, accessed 31 May 2021.

27 von Ajkay, 1971, p. 22.

28 W. Hodenberg (ed.), Hoyer Urkundenbuch, Hannover, 1856.

29 That Hillebrandt could not have painted the portrait since he was in Stockholm and Margareta Eriksdotter in Lübeck was first pointed out in Karl Erik Steneberg, Vasarenässansens porträttkonst, Stockholm, 1935, p. 19.

30 On Hans Kemmer, see Dagmar Täube (ed.), Lucas Cranach der Ältere und Hans Kemmer: Meistermaler zwischen Renaissance und Reformation, exh.cat., St. Annen-Museum, Lübeck, Munich, 2021; Christoph Emmendörffer, Hans Kemmer: Ein Lübecker Maler der Reformationszeit, Leipzig, 1997. On the artistic production in Lübeck in the early sixteenth century, see also Jan Friedrich Richter (ed.), Lübeck 1500: kunstmetropole im Ostseeraum, exh.cat., Museumsquartier St. Annen, Lübeck, Petersberg, 2015.

31 The three portraits by Hans Kemmer from 1534 are known as ‘Portrait of Hans Sonnenschein’ (‘Porträt des Hans Sonnenschein’), Portrait of a Lady’ (‘Porträt einer Dame’), and ‘Portrait of a Man’ (‘Porträt eines Herrn’). Täube (ed.), 2021, pp. 180–183.

32 von Ajkay, 1971, p. 12–14. Von Ajkay’s bachelor thesis is the most in-depth study that has been made on the portrait(s) of Margareta Eriksdotter, and it has been a source for later publications on renaissance art in Sweden where the portrait has been included (see i.e. Boo von Malmborg, Svensk porträttkonst under fem århundraden, Malmö, 1978, p. 22). Von Ajkay is also the only one who has acknowledged that it exists more versions than just the one single portrait of Margareta Eriksdotter.

33 Katharina Frank, Die biblischen Historiengemälde der Cranach-Werkstatt: Christus und die Ehebrecherin als lehrreiche ‘Historie’ im Zeitalter der Reformation, Heidelberg, 2018, pp. 28–35; Gunnar Heydenreich, Lucas Cranach the Elder: Painting Materials, Techniques, and Workshop Practice, Amsterdam, 2007.

34 See Andreas Tacke, “Cranach-on-Demand: Zu Wiederholungen in der Malerei”, in Täube (ed.), Munich, 2021, p. 88. Hans Kemmer’s ‘Death painting of Hermann Bonnus’ (‘Totenbild des Hermann Bonnus’) from 1548 was painted as duplicates, and Kemmer also painted several versions of ‘Jesus and the Woman taken in Adultery’ (‘Christus und die Ehebrecherin’ 1530, 1535) based upon the same design. Täube (ed.), Munich, 2021, p. 176, 234–237.

35 Gunnar Heydenreich, “Hans Kemmer: Spuren künstlerischer Gestaltungsprozesse. Teil II: Wittenberg”, in Täube (ed.), Munich, 2021, p. 67.

36 Heisterberg, Müller-Bechtel & Putzger (eds.), 2018, pp. 17, 20; W.J.T. Mitchell, What do Pictures want? The Lives and Loves of Images, Chicago, 2005.

37 Walter Cupperi, “Introduction: Never Identical. Multiples in Pre-Modern Art?” in Walter Cupperi (ed.), 2014, pp. 7–28.

38 More specifically, a dress in black velvet decorated with gold weaves, four gold chains, four buckles of gold decorated with gems and jewels, golden rings with gems, and a hat in black velvet decorated with gold on the edges. (‘schwarzseidener Rock mit Goldgewebe besetzt’, ‘Goldgegenstände: 4 Ketten, 4 Spangen mit Edelsteinen und Klenodien, goldene Fingerringe mit Edelsteinen’ and a ‘Schwarzseidener Hut mit Verzierungen aus Unzengold verbrämt’). According to the estimated economical value listed in the inventory, these garments and jewellery were her most expensive belongings, so it makes sense that they would also have been depicted in her portrait. Gotthard von Hansen, Aus Baltischer Vergangenheit: Miscellaneen aus dem Revaler Stadtarchiv, Reval, 1894, pp. 13–14.

39 Mereth Lindgren, “Måleriet”, in Göran Alm (ed.), Renässansens konst, Signums svenska konsthistoria, vol. 5, Lund, 1996, p. 244.

40 Augustyn & Söding (eds.), 2010, p. 4; Mensger, 2009, p. 197.

41 A copy of Fig. 5 has been part of the art collections of Uppsala University since 1835, when it was donated there by the antiquarian and collector Adolf Ludvig Stierneld. The painting is unsigned and undated, but it was probably painted in the early nineteenth century on commission from Stjerneld. Adolf Ludvig Stjerneld, Samling, tillhörande öfver-kammarherren, friherre Stjerneld., Johan Hörberg, Stockholm 1835, p. 8. I would like to thank art historian Per Widén for his expertise on Stierneld and his antiquarian activities. In the collections of Skokloster Castle can be found a half-figure portrait that is a combination of a cropped copy from the copy painted by Jägerdorfer in the 1630–40s, together with an added coat of arms representing the Vasa family copied from one of the 1528 portraits. Like the rest of the copies treated in this text, the portrait is unsigned and undated, but it is first mentioned in the inventories of Skokloster in 1823 and was probably painted in the early nineteenth century. Two more portraits in private collections are mentioned in von Ajkay 1971. I have neither seen them nor any images of them but, judging from the descriptions of the motifs in von Ajkay 1971, they are free copies of the 1528 portrait(s) from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

42 Larry Shiner, The Invention of Art: A Cultural History, Chicago & London 2001, pp. 57–74.

43 See Kristoffer Neville, The Art and Culture of Scandinavian Central Europe, 1550–1720, Pennsylvania, 2019.

44 See Kristoffer Neville & Lisa Skogh (eds.), Queen Hedwig Eleonora and the Arts: Court Culture in Seventeenth-Century Northern Europe, London, 2017; Karl Erik Steneberg, Kristinatidens måleri, Malmö, 1955.

45 ‘Elbfas, Jacob Heinrich’, Svenskt konstnärslexikon, Malmö, 1953; Lisa Skogh, Material Worlds: Queen Hedwig Eleonora as Collector and Patron of the Arts, diss. Stockholm, Stockholm, 2013, pp. 75–78.

46 Anna Womack, “Christian Hammer och Nordiska museet”, in Christina Westergren (ed.), Brokiga samlingars bostad, Fataburen, Stockholm, 2007; Katalog der Schwedischen Portraits-Sammlung des Museums Christian Hammer in Stockholm, Cologne, 1893, p. 1.

47 The portrait is mentioned in a 1651 inventory of Wisingsborg, so it could not have been painted later than that. ‘Werner (Wernich), Johan Johansson (Jägerdorfer)’, Svenskt konstnärslexikon, Malmö, 1967; Wilhelm Nisser, Konst och hantverk i Visingsborgs grevskap på Per Brahe d.y.s tid, Stockholm, 1931, pp. 157–168.

48 Portraits of Margareta Eriksdotter are listed in the inventories of Västanå Manor (1648), Bogesund Castle (1655), and Rydboholm Castle (1728) according to von Ajkay, 1971, pp. 32–33, n. 47.

49 Weidhagen-Hallerdt, 1999.

50 See for instance Megan Holmes, “Reproducing Sacred Likeness in Early Modern Italy”, in Heisterberg, Müller-Bechtel & Putzger (eds.), 2018; Anita Jansen, Rudi Ekkart & Johanneke Verhave, De portretfabriek van Michiel van Mierevelt (1566–1641), Delft, 2011; Megan Holmes, “Copying Practices and Marketing Strategies in a Fifteenth-Century Florentine Painter’s Workshop”, in Stephen J. Campbell & Stephen J. Milner (eds.), Artistic Exchange and Cultural Translation in the Italian Renaissance City, Cambridge, 2004. Pouncing is a technique for creating copies by laying a semi-transparent paper over an image and then tracing the lines with a pouncing wheel. The technique is similar to how carbon paper is used to copy text. Pouncing wheels (also known as tracing wheels) are still used today to, for instance, transfer markings from patterns when sewing.

51 Mensger, 2009, p. 199.