?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

When reading texts mentioning past currencies, especially those that were in use in Ottoman and British Palestine and the first decade of the State of Israel, historians often remain puzzled as to the relative value of former legal tenders in particular historical periods (i.e. what a specific sum of money could buy), and more so how to interpret the value of specific currencies between these and later periods. Such an interpretation is not only the interest of historians, because there is a practical need to verify sums in obsolete currencies, such as in agreements and laws, in today’s money. Few experts are able to make even an inexact linkage from the Mandate period to present day Israel, while linkage from the Ottoman period remains too vague. The main aim of this article is to improve this situation by using applied history, to propose some rules of thumb for understanding the magnitude of such currencies, according to market values and/or laws, and to provide a provisional tool for linkage of former legal tenders – Ottoman Liras, Egyptian Pounds, British Pounds, Palestinian Pounds, Israeli Liras and old Shekels – to present monetary values.

The State of Israel was established in 1948 on the territories of Mandate Palestine, a British colonial territory previously ruled by the Ottoman Empire up to 1918. Continuity existed between these regimes. Specifically, in relation to the current study, financial transactions in one era were treated as accountable in following era/s. The Ottoman legal system gradually reformed from 1839 onwards, and for Palestine the relevant year is 1841 (between 1831 and 1841 the country was ruled by Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt). Even when modified, Ottoman laws became the foundation for British and later some Israeli laws; and the same is true of some laws in Israel that were initiated in the Mandate era.Footnote1 At the same time there was a significant discontinuity in what constituted official legal tenders. These were Ottoman Liras, Egyptian Pounds, British Pounds, Palestinian Pounds, Israeli Liras and old Shekels, whereas the only legal tender today is the New Israeli Shekel. And not only did currencies change, but inflation (the average increase in price of a basket of goods) or deflation (average decrease of the basket prices) could occur in any currency.

The way in which the value of money was dictated has changed considerably between 1841 and today (the era under examination), and the following periodization is proposed: (I) under the Ottomans, the value of money was fixed to the price of gold, in a ‘commodity money’ system. This continued under British rule until September 1931. Researchers had very little information on the relative value of money in this period, or, in simple terms, of the cost of a wide range of goods. Later, the legal tender in general use was no longer linked to gold,Footnote2 and a ‘fiat money’ system became dominant in which the value of money was dependent on the supply of, and demand for, the legal currency. Regardless of which regime ruled the country, the fiat era may be divided into two: (II) the period for which the information on the value of money is limited and/or inexact, in general from 1931-1954, and (III) the period for which comparatively much better information is available, from 1955 to date, with a general trend of greater accuracy within the latter category as the years passed. More information about this proposed categorization is given below.

Linkage – the exchange rate of a particular currency from one era into another currency and/or era – is an important factor in historical analysis. Without it, an economic perspective on continuity and change remains very limited. Linkage is relevant, for instance, in the interpretation of historical agreements, and in Israel linkage also has contemporary relevance because some sums mentioned in some old laws in outdated currencies may still be the reference for interpreting them in the present. In addition, students of history are often puzzled as to the magnitude of historical sums in pre-State Israel (i.e. which products a specified sum could buy in a particular currency; or how much a person used to earn in a former currency in, say, one month). The overall objective of this paper is to provide a tool for those seeking to make linkages across eras; and to create rules of thumb for understanding the magnitude of sums mentioned in formal legal tenders in pre-State Israel.

One major aim of this article is to facilitate conversions from fiat era II into fiat era III while noting the imperfect data and calling for further research towards greater accuracy. Although some data is available on changes in the value of money during most of the British Mandate years in Palestine, it is rarely connected to data from the State of Israel; instead, unconnected enclaves of periods are given with no clear understanding of the relative value of money across them. It is not difficult, for example, to find the value today of, say, 100 Israeli Pounds/Liras (IL) from 1955, because linkage for it is available from Israel’s Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS). But if one wishes to know today’s value of money from the Mandate era, say £P100 from 1945, there is no easily accessible information and few experts who know how to calculate it. Even then, some differences in calculations may be found.

A second major aim is to propose a possible solution for linking monetary values between the gold commodity money era examined here, 1841-September 1931, and the two fiat eras. Information on the value of different commodities in Palestine in the Ottoman era is scarce, more so than from the British Mandate era. Before September 1931, a certain amount of money would theoretically always buy the same amount of gold, although in practical terms this was not always the case, because the value of gold showed slight variations during the 1841-1931 era (see below). Since a reliable cost of living index for this era is missing, the suggestion in this paper for a workable linkage is fairly unconventional – to analyze the value of money in Palestine from that era as if it were the gold it was pegged to, and to follow its price in gold. More details on the reasons for this, and the limitations, are explained below. The suggestion for linkage both for era I and era II is far from perfect. Still, it is a much better compromise than indirectly assuming that a linkage is impossible. Waiting for perfect data that does not exist, and not turning to alternative data that could help to establish a generally reliable linkage, hinders knowledge. Perfect linkage, in this case, is the enemy of reasonable but imperfect linkage. At the same time, it has to be stressed that the suggestions for linkage made here are interim.

In sum, this brief opening section defines three major eras that are relevant to an examination of the value of money and are not strictly fixed to the dates of successive political regimes: (I) the era of gold commodity money, 1841-September 1931, discussed in the next section; (II) the intermediate era, from 1931 to 1954, where an improved, yet far from exact cost of living index is available; and (III) the era from the second half of the 1950s, which provides much better information on the value of money. Further information about the currencies and their value is available below in two formats: general rules of thumb that facilitate an understanding of the magnitude of pre-state formal legal tenders, Ottoman Liras, Egyptian Pounds, British Pounds, Palestinian Pounds; and practical guidelines that enable readers to establish a linkage with monies from the past, when that is possible, or roughly linking them when it is not. Finally, it should be made clear that this article does not deal with collectors’ values or with the sentimental value of ancient coins or bills, but with linkage value of currencies. It is also a first attempt at making such a long-term linkage, often based on limited information on prices, and will likely be improved and updated in due course.

Linkage and the era of gold commodity money, 1841-Sept.1931

Under the commodity money system that was in practice worldwide, metal coins were the accepted medium of exchange, and a coin’s type of metal and its weight – the meltable price and not the minting – primarily determined its value.Footnote3

Under the Ottomans, the value of gold and silver money was closely linked to the commodity they were made of, as emphasized in Şevket Pamuk’s highly detailed study:

Gold was used for large transactions and for the store of wealth while bronze and later copper dominated the small daily transactions. Silver coinage occupied the middle ground. As prime examples of commodity money, the value of gold and silver coins remained closely linked to the commodity value of the metals they contained. In contrast, bronze and copper coinage often circulated as fiat money at values attached to them by the state which was above their metal content.Footnote4

While the customary reference for Ottoman lira is to a gold coin with a value closely linked to its actual value if melted, a reference to Ottoman paper money is also needed to cover the subject fully. From the 1830s, in the Istanbul area, the Ottomans issued a paper money called kaime-i muteber-i nakdiyye (hereafter kaime), that was in practice a mixture of money and bond, because it also yielded interest. Such bonds continued to be issued later on.Footnote6 In 1881, the Ottomans committed to the international Gold Standard, so that any Ottoman lira issued in paper money could be transferable to the 7.216 grams of 22 carat gold contained in gold coin lira.Footnote7 However, the empire was already in a weak and unstable monetary condition (with a bankruptcy crisis in 1875)Footnote8 so that there was little security to holding such papers issued by the Ottoman government. The solution was found by granting to the Imperial Ottoman Bank, a private bank founded in 1863 by the British and French, the exclusive privilege of issuing gold-convertible banknotes. On the one hand, no gap in value was expected between notes and coins. On the other hand, the issue of these banknotes remained very small scale, as was revealed in a study by Ali Coşkun Tunçer.Footnote9 In addition, in the very last years of the empire, from 1915, the Ottoman government issued wartime paper bills that were regarded with increasing distrust in relation to the real exchange rates between notes and coins of 1.00:1.05 in 1915, 1.00:1.88 in 1916 and 1.00:4.70 in 1917.Footnote10 Such paper monies were also available in Palestine from 1915-1917, creating much uncertainty for those who received payments in them. However, as Sreemati Mitter commented:

Luckily for the Palestinians (who continued to hoard gold coins) and for the Ottoman Bank officials in Palestine (who continued to be unable to magically equate the paper to the gold), the situation came to a happy ending, of sorts, in November 1917, with the arrival of the British army in Palestine.Footnote11

The limited information that is available on commodity prices is not sufficient to create a cost of living index, yet it suggests that from 1860 the purchasing power of the Ottoman lira (i.e. the goods and services that a certain amount of gold liras could buy) remained fairly stable. In another study by Pamuk on prices in the empire between 1469-1914, which examines the price of 16 commodities (or less if any are missing) across the empire – such as between Istanbul, Damascus and Jerusalem – it was found that the prices were correlated, and that although there were fluctuations in the value of gold against these commodities (which was likely to occur when supply and demand changed, e.g. the wheat price could fluctuate according to a good or bad crop yield), there was an overall stability in the gold purchasing power: ‘the overall price level was relatively stable […] from1860 until World War I.’Footnote12

The above discussion may offer a rule of thumb for Palestine from 1841: any reference to lira in the examined period meant Ottoman gold lira unless explicitly identified otherwise (such as sums mentioned in wartime paper bills). The value of such lira was basically the melted value of 7.216 grams of 22 carat gold (equivalent to 6.615 grams of pure 24 carat gold), and during that period the relative purchasing power of the lira, i.e. the real value of the lira, was fairly stable.

The British conquered the country during the war years 1917-1918, after Great Britain had officially departed from the Gold Standard in 1914. In practical terms, as suggested by Michael Bordo and Finn Kydland, the Bank of England only began the abandonment in 1919, and delayed any activity to 1925Footnote13 when it announced the opposite of what was expected – a return to the prewar parity of the British Pound (£, aka GBP) to gold. This situation did not change until September 1931, when the Bank re-announced departure from the Gold Standard together with the devaluation of the GBP against gold and the imposition of foreign exchange controls.Footnote14

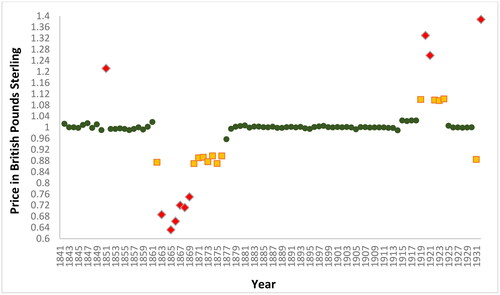

In fact, as can be seen in , the commitment of major economies to the Gold Standard during the 1870sFootnote15 restored a stable era in the value of GBP against gold. Between 1878-1914 £1 was worth 7.32 grams of pure gold (24 carats, in a minted £1 gold coin) with an insignificant 1 per cent fluctuation in the value of gold (between £0.99 and £1.01). More variations occurred in later years. During the war years of 1915-18, £1.024 could buy the said quantity of gold. In 1919 and 1922-24 about £1.1 was needed to buy the said grams, with an extremely different situation in 1920 and 1921 when £1.33 and £1.28 were needed. Stability restored between 1925-1930, with a small diversion in 1931. Hence, apart from a significant deviation in 1920-21, the price of £1 was fairly close linked to the price of its gold content for more than six decades, from 1870-1931:

Figure 1. The price of 7.32 grams of pure gold in £GBP.

Source: Data on gold prices has been obtained from the Chards online database (https://www.chards.co.uk/gold-price/gold-price-history).

Note: All the dots in this figure represent the same parameters. The green dots mark high stability years in the value of the pound against gold, the yellow squares fair stability, and the red diamonds instability.

Following the occupation of Palestine, on 12 December 1918, the British administration issued Public Notice 73 A designating certain currencies as legal tender in Palestine and fixing an exchange rate between them and the British-controlled Egyptian Pound (£E). The £E was unofficially marked as a leading currency, linked to the value of gold, with fixed exchange rates against other legal tenders – coins and banknotes from France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy, United States, Austria, Germany, India, Turkey and Britain. The use of £T in Ottoman money was allowed, with its exchange rate determined by the gold minting value (i.e. a continuation between the eras). Several months after his appointment as the first High Commissioner for Palestine, Sir Herbert Samuel issued Public Notice (no. 36) on 2 January 1921, designating only the Egyptian Pound and the British ‘gold sovereign’ (a gold coin with a nominal value of £1) as the country’s legal tender. Next, in 1927, the British administration’s Palestine Currency Board announced a new currency – the Palestinian Pound (£P)Footnote16 – with a pegged conversion rate of £E0.975 to £P1, which approximated to the differences in pure gold between the currencies. The same was true for pegging Palestinian Pounds as equal to GBP, with same amount of gold attached to the value of each currency:

A gold coin of one Palestine pound, containing 123’27447 grains of standard gold, and being otherwise of such composition and weight and subject to a remedy of such amount as may be approved.Footnote17

The above discussion suggests that in spite of some fluctuations in particular years, for nine decades from 1841 to 1931 gold was essentially stable and constituted the commodity money of the country. The currencies changed, but gold, the commodity that determined their value, remained the same. This also makes currency conversions fairly accurate and simple between the major legal tenders in the country, as their weight in gold closely resembles the conversion rate. shows the ratio of conversion between these currencies, and includes a very simple formula for easy conversion of sums in Ottoman and Egyptian liras into Palestinian Pounds.

Table 1. Currency conversion, 1841-Sept. 1931.

An exception to this conversion may be in unusual cases where sums are mentioned in speculative investment, such as in the aforementioned wartime paper bills that were, in practice, high-risk loans given to a non-creditworthy government during a war that it was constantly losing.

Even if the value of money is regarded as a specific amount of gold, as it was until 1931, the passage of the years and the fact that there is no adequate reference for the cost of living and for the relative cost of a variety of products may leave readers puzzled as to the relative value of sums of money mentioned in the gold commodity era. For example, the Ottoman Civil Procedure Law of 1879, which was adopted by the British in Palestine, states in Article 80 that any obligation for sums above £T10 has to be written into an agreement:

Claims relating to obligations, contracts or partnerships, collection of taxes or loans which are customarily recorded in a written document, and which exceed ten [Ottoman] liras, must be proven in a written document.Footnote18

What was the monetary value of such sums measured in working days in the gold commodity era of the Mandate? While reports on wages during the Mandate period are available especially from the late 1930s,Footnote20 Deborah Bernstein, in her study on Jewish and Arab workers in Mandate Palestine, examined some data for the earlier commodity (gold) market period. She refers to a government source from 1929 that assessed unskilled Arab wages as standing between 80 and 160 mils (1,000 mils = £P1), and a government commission in 1928 mentioning Arab unskilled labor as earning between 120 and 170 mils a day.Footnote21 If the same calculation is made here as for the Ottoman era, an Arab unskilled worker had to work between six and 12 days to earn £P1. For the sum mentioned in the law – remembering its conversion in £T and to multiply it by 0.909 in order to express it in £P (see ), the reference in the law is to a sum that could be earned in between 55 and 109 days (between 6*9.09 and 12*9.09). Namely, in both Ottoman and Mandate gold commodity money, the sum mentioned in the Ottoman Civil Procedure Law of 1879 was quite significant.

To make it even more inexact yet more simple, to get a general idea of the sums mentioned in documents, prior to – and not instead of – deeper investigation and more exact calculations it might helpful to have in mind that an unskilled worker had to work between one and three weeks to earn one lira/pound of any kind (£T, £E, £, £P) in the period from 1841 to 1931. This may still give only a rough guideline until the necessary in-depth research into the linkage is conducted.

Since there is no reliable knowledge of the purchasing power of the money in relation to the ability to buy a variety of non-gold commodities, there is also no way to create a reliable cost of living index to enable a historical currency conversion for the 1841-1931 period. Nevertheless, during that time, the purchasing power of currencies in the country was probably fairly stable. We have seen that the reality in this period was that gold commodity money governed the market and that a commitment to pay a specific sum, say in an agreement or in law, meant above all a commitment to provide a certain amount of gold. In this situation it seems reasonable to suggest that for linkage across eras, any sum of money mentioned until 1931 (apart from the above-mentioned exception) will be regarded as gold in specific amounts. For example, the sum of £T10 in conversion would equal 66.15 grams of pure gold.

Conducting such a conversion is simple. The historical and current values of gold may be easily accessed on several websites, with the UK’s Royal Mint particularly helpful for an orientation of current values, and Chards for historical values. All of the values are usually given in troy ounces of pure gold. Knowing that the value in hand (i.e. the ‘price of pure gold ounce’), and the relative value of 1 gold troy ounce to the currencies in (i.e. the ‘currency conversion value’), make it easy to calculate the value in the obsolete currency (i.e. ‘original sum’) as: . If one wishes to know, for example, the current value of £T12 and finds that the currency value in the Royal Mint website is GBP1,551 per one pure gold ounce; one then looks at to see that the currency conversion value for one ounce is £T4.7, so that the price of £T12 is GBP3,960 (

); and converting the sum into New Israeli Shekels can be easily done via the Bank of Israel website or that of the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS).

This section reviewed the era of gold-commodity money in the territory of Palestine/pre-state Israel from 1841, the post-Egyptian era, until it ended in 1931. A discussion of the historical facts and available data led to suggesting that the better option for conducting linkage in this case is by following the value of the specific amount of gold that would be received for particular currencies if a gold coin of this currency could or would be melted. Methods for calculating the values were discussed in this section. An exception to this conversion is unusual cases where sums pertain to speculative investments, such as wartime paper bills. In addition, it was suggested that a rule of thumb on the magnitude of money is that an unskilled worker had to work between one and three weeks to earn one lira/pound of any kind (£T, £E, £, £P) during the years 1841-1931.

On the possible need to re-interpret Ottoman laws in Israel

With the establishment of the State of Israel, the Currency Ordinance of 1948 stated that in any existing legislation from the British era where sums of money are mentioned in British or Palestinian Pounds (£ or £P), they have to be read as Israeli Pounds/Liras (IL). This law also made the £P in use under the British, legal tender in Israel until its replacement by the Israeli lira:

2. Wherever for any purpose, in the past or in the future, a reference to a pound or Palestine Pound or Lirah Eretz Israelith or Lirah E. I. or LP. or Lirah is, or has been, made, in writing or orally, or implied, such reference shall be deemed to be a reference to an Israel pound, unless the provisions hereof are expressly excluded.Footnote22

2. In any Ordinance or law which at the date of the commencement of this Ordinance is in force in Palestine, references to Egyptian pounds and Turkish pounds shall be read and interpreted as though they were references to Palestine pounds.Footnote23

More than three decades after the Israeli Currency Ordinance of 1948, the Interpretation Law of 1981 was issued in Israel. This law reduced the status of earlier translations of Ottoman laws by ruling that the original language in which a law was written – also if it was written in Ottoman Turkish – would be the binding language if any debate arises:

24. The binding text of any law is the text in the language in which it was enacted. However, in the case of a law enacted in English before the establishment of the State of which a new version has been introduced under section 16 of the Law and Administration Ordinance, 5708-1948, the new version shall be the binding text.Footnote28

The tendency to refer to Israeli liras and not to Ottoman gold liras is still strongly embedded. While writing these lines, an open debate continues as to whether the Israeli ‘Ottoman Association’ – controlled by the above law – extracted exorbitant fees from its members, or not. A class action lawsuit against a mega-sized non-governmental organization, the Histadrut General Organization of Workers, was rejected as being unrepresentative.Footnote31 But the seeds exist for further lawsuits following the plaintiffs’ argument that ‘Ottoman Associations’ (such as the Histadrut) cannot and could not levy from members more than IL 24, according to the Ottoman Association Law (1909), which in 2018 – according to the plaintiffs’ analysis – was worth between new Israeli shekels (NIS) 0.0024 (without linkage) or between NIS 245 and NIS 961 with linkage, so that the Histadrut allegedly levies too much.Footnote32 However, if we follow the translation of the original law (see above discussion and ), apply the method suggested above, and take into consideration that at the end of 2022 an ounce of gold was worth £1,479 and the conversion rate was £1 = NIS 4.24, it becomes apparent that at the end of 2022 the value of £T24 was equal to NIS 32,022 ; or to NIS 28,104

in 2018 prices – the year of the lawsuit.

Article 80 of the Ottoman Civil Procedure Law of 1879 decreed that an agreement had to be signed for any obligation in sums above £T10Footnote33 and that such a sum was very significant (as discussed, it was equivalent to between 55 and 170 days of work). In the pre-1981 era, such a law would probably be interpreted as referring to IL10. This reference, without linkage, means that a contract is necessary for every transaction because any transaction is higher than NIS 0.001 (as explained below), or if with linkage, that from 1948 to December 2022 a contract has to be signed for transactions from roughly above NIS 400 (calculated in the method explained in ). This means that currently a contract needs to be signed to take a taxi for the 60 kilometers from Jerusalem to Tel Aviv. This was not the law’s intention. However, its intention is much better maintained if the value of £T10 is associated with the suggested linkage to gold (NIS 13,342 in 2022). Preserving the law’s intention may be another reason for the preference to keep prices in gold, in regard to Ottoman laws.

It seems relevant to suggest with regard to laws from the Mandate period, that the Currency Ordinance (1948) requires reading them as if they were stated in Israeli Liras. Even so, a linkage would uphold the law’s intention much better. Take, for example, the Antiquities Ordinance (1929) which obtains in Israel lists a fine of £P1,000 for the illegal export of antiquities:

22 (5) Any person who exports or attempts to export an antiquity of which the exportation has been prohibited in accordance with section 16 is guilty of an offence and is liable to imprisonment for six months or a fine of one thousand pounds or the value of the antiquity whichever is the greater sum.Footnote34

Finally, it is worth mentioning that the suggested linkage of sums from Ottoman times – exchanging sums from the era of gold commodity money into gold prices for later period – was also adopted in Israeli courts as long as the issue was not the interpretation of sums mentioned in Ottoman laws. In a verdict from 2016, Judge Michal Woolfson reviewed earlier judgments on how to interpret loan agreements in obsolete currencies. The general view was that in cases where the loan was taken out in local currency, the expectation was for repayment in the same currency. In cases where loans were given in Palestinian Pounds when the pound was pegged to gold, the basis for calculating the value is that gold repayments have to be repaid in the current equivalent value of gold, while the value of 7.3223 grams of pure gold is exchanged with £P1 (to this may be added charges, such as for interest rates or fines for late payment). Interestingly the judgment mentions that loans pegged to gold or external currencies were permitted until 1941 when they became prohibited.Footnote36

In sum, the Interpretation Law of 1981 states that the original language in which a law was written is the binding language for interpreting that law. The problem, however, is that instead of translating the ‘Ottoman Liras’ (£T) mentioned in the laws, the most habitual translation is ‘lira’ – and the reference in courts was usually to Israeli liras, i.e. a wrong interpretation since the Ottoman laws essentially referred to the Ottoman currencies that were pegged to gold. This finding may call for Israeli courts to revisit the method of interpreting sums mentioned in Ottoman laws. In addition, to take into account the intention of the British legislation, it is also necessary to follow the linkages, or any given sum would become insignificant.

Linkage in the fiat money era, 1931-2023

Since September 1931, no linkage to gold has existed. The Palestinian Pound and later the Israeli Pound remained pegged to the GBP until 1954. It was an era of high intervention in foreign exchange and currency values,Footnote37 causing significant difficulties for creating indexes of prices and cost of living.

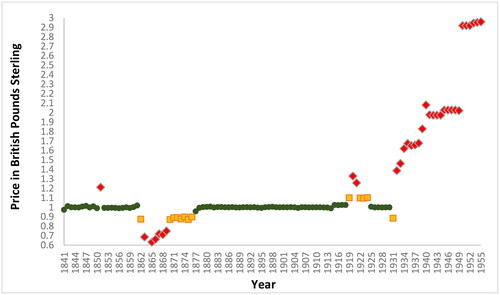

Still, since this intermediate era was significantly different from the previous one, not only did the linkage to gold as commodity money end, a significant gap emerges between gold and GPB values (see ), so that preference has to be given to more fiat-oriented cost of living indexes (and not gold) that are far from being exact in the intermediate era, yet are the best available.

Figure 2. The price of 7.32 grams of pure gold in £GBP (the longer period).

Source: Data on gold prices is from Chards online database (https://www.chards.co.uk/gold-price/gold-price-history).

The more information that is available on the price of a variety of commodities and on the habitual spending of consumers, the better the ability to construct an inclusive ‘basket’ that enables us to see changes in the purchasing power of money. Inclusive data of commodity prices (retail and wholesale) is needed to create comprehensive price indexes as first established by Etienne Laspeyres (1871) and later by Hermann Paasche (1875).Footnote38 Today, cost-of-living indexes are a significant tool for assessing changes in the value of money over time. Basically, such an index follows the amount of money needed for a variety of expenditures over the years, such as housing, food, taxes, and healthcare. In such an index, the value of a large number of goods and services is defined as the ‘basket’, and the changes over time in the value of the basket is thought to be representative of changes in the nominal value of the money. If the value of the basket is given the index number 100 as a reference year, and buying the same basket in the following year would cost 5 per cent more because of inflation, then the second year would be given the index number of 105. The focus of such an index is prices, not the availability of capital such as from wages, and from time to time it is called the ‘conditional’ cost-of-living index.Footnote39 There are criticisms of such indexes as failing to trace exact changes when consumers switch from more expensive to cheaper commodities and/or shops, as well as the problem of tracing the introduction of new goods and the quality changes in existing goods.Footnote40 Nevertheless, such indexes are acknowledged as enabling a fairly accurate overview of price changes and are used worldwide.

The first governmental attempt to create a cost-of-living index in Palestine was in 1942, based on available British data published in the Statistical Abstract of Palestine and in the General Monthly Bulletin of Current Statistics, which covered about thirty food commodities and a dozen miscellaneous items;Footnote41 but as the British themselves stated, not only was the data scant, but it was also very far from accurate, and there was much skepticism as to the accuracy of the prices because of government price controls and unrecorded black market prices:

Dissatisfaction generally arose from a widely held opinion that the cost of living index did not truly represent the position, owing to the non-availability of some of the commodities on which it is based and black-market operations in others.Footnote42

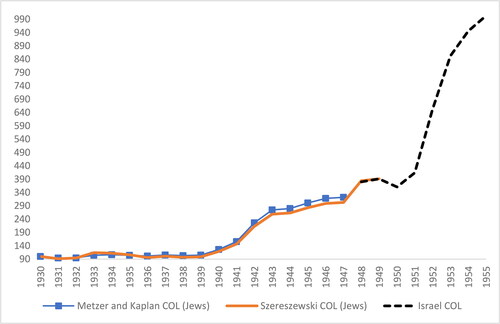

In addition, the State of Israel published an annual cost-of-living index from 1948. However, this too was far from exact until 1954, according to the Director of the Demography and Census Department of the Israel Central Bureau of Statistics, who said that until 1954 there was insufficient data ‘to form a solid basis for the consumer price index’.Footnote45 Added to this were the Israeli policy of austerity up to 1952 and the government’s linkage of the value of the Israeli Lira to the British Pound until 1954,Footnote46 so it seems we are left with inexact data until 1954. However, the three indexes described are presented in .

Figure 3. The reference indexes, 1930-1955.

Sources: Robert Szereszewski, Essays on The Structure of the Jewish Economy in Palestine and Israel (Jerusalem: The Maurice Falk Institutes, 1968), pp.52-57, 68, 77. Jacob Metzer and Oded Kaplan, The Jewish and Arab Economies in Mandatory Palestine: Product, Employment and Growth (Jerusalem: The Maurice Falk Institutes, in Hebrew, 1991). Five publications by the Government of Israel for the years 1949/50, 1950/51, 1952/53, 1953/54, 1954/55: Government of Israel, Statistical Abstract of Israel (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, various years).

Note: ‘COL’ in the Figure stands for ‘cost of living’.

Image 1. The Ottoman Association Law, 1909: a copy of the original law.

Source: The Ottoman Empire, The Ottoman Official Gazette (Takvim-i Vekayi), 10 Ağustos 1325 [23 August 1909], pp.11–13.Footnote30

Note: The original law in Ottoman Turkish states a sum of twenty-four gold coins (آلتونى تجاوز/altini tecavüz).

![Image 1. The Ottoman Association Law, 1909: a copy of the original law.Source: The Ottoman Empire, The Ottoman Official Gazette (Takvim-i Vekayi), 10 Ağustos 1325 [23 August 1909], pp.11–13.Footnote30Note: The original law in Ottoman Turkish states a sum of twenty-four gold coins (آلتونى تجاوز/altini tecavüz).](/cms/asset/a7d4394f-d5f0-4c61-a953-c2ecffad9c41/fmes_a_2237416_uf0001_c.jpg)

With all the limitations, currently these data seem to represent the best available and were therefore chosen to be used for the years 1931-1954. As can be seen in , there is much similarity between the cost of living indexes of Szereszewski and of Metzer and Kaplan. The fact that Szereszewski’s index includes data for the years 1948-1949, facilitated an easier connection between that index and the Israeli government’s indexFootnote47 and was therefore selected as a reference for the Mandate period. An index number for each year is presented in .

Table 2. Cost of living index (inaccurate).

How can the above index be used for linkage? Basically, in the following way: (1) remembering that the Israeli government dictated that sums in £P had to be converted to IL at the rate of 1:1, any sum mentioned in £P for early years may be regarded as in IL for the sake of currency exchange; (2) in order to convert money from an original year into a converted target year, the following formula may be used: .

Accordingly, if, for example, one wishes to know the value in 1955 prices of £P5.596 (5 pounds and 596 mils) from 1934, shows that the index number for 1934 is 122.51, and for 1955 it is 1094.58. Plotting these numbers in the above formula shows that £P5.596 from 1934 – with disclosure on the limitation of the index – was worth nearly IL 50 in 1955: ).

In the post-1954 era, with little fluctuation, the later the year, the less the government intervened in the marketsFootnote48 and the more information became availableFootnote49 – a situation that may provide a resource for a more accurate cost-of-living index.Footnote50

In 1980, following hyperinflation, Israel announced the replacement of the Israeli Pound (IL) by shekels in the ratio of IL 1,000 = 1 Shekel. Hyperinflation, however, continued and the New Israeli Shekel (NIS) was introduced in 1985, replaced the Shekel in the ratio of 1:10. This, together with the above-mentioned roles for the IL=£P, dictated a conversion ratio of £P10,000 = IL 10,000 = IS 10 = NIS 1. This conversion is for nominal prices, of course, and does not represent any linkage.

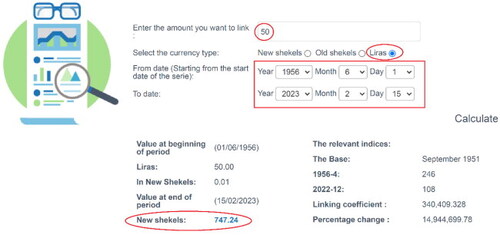

The CBS enables an easy online conversion of sums of money from October 1951 to date, with their ‘online linkage calculator’ using their cost of living index. Basically, any sum from a particular date can be linked to a different year, although there is a need to mark the original currency in which the sum was (IL/Shekel/NIS). The CBS states that the calculator’s ‘results are not binding. For calculations of financial or other importance, the calculation of linkage should be performed not by means of the calculator.’ In other words, the CBS recommends making an additional check of the results against their official publications.Footnote51 The calculation is very intuitive. For example, a linkage of IL 50 from mid-1956 to February 2023 (worth NIS 747) is presented in the next image:

Until now we have discussed linkage within each fiat period in a separated way, either 1931-1954/5 or 1955 up until today (2023). What if, however, one wished to find the value of a specific sum of money, such as the £P5.596 from 1934, in NIS in February 2023? This can be done in two combined stages, each of which was discussed in two earlier sections:

Stage I: Conversion of the original sum into 1955 prices, as conducted in the earlier page. In our example, it was found that £P5.596 from 1934 was worth IL 50 in 1955.

Stage II: Conversion via the CBS calculator of the same IL 50 from mid-1955 (i.e. 1 June 1955) into February 2023. This was conducted earlier (NIS 747, see ). The result is that a £P5.596 from 1934 is worth NIS 747 in February 2023.

Conclusion

A major aim of this article was to examine the changes in currencies over time and attempt to provide a tool for linking obsolete currencies – Ottoman Liras, Egyptian Pounds, Palestinian Pounds, Israeli Liras and Shekels – into the present day in Israel; as well as to facilitate an easy linkage between these obsolete currencies. The way to do so was explored in the article.

For the era of gold-commodity money, from 1841 until September 1931, the practical linkage offered is using the price of the exact amount of gold that was in specific gold coins. An exception to this conversion is the unusual cases of sums of money in speculative investments like wartime paper bills. Methods for calculating the values – today and in earlier years – was discussed in this article.

Calculating the conversion into today’s prices of fiat money from 1955 onward is recommended via the CBS website and its online calculator. For sums from 1841-1955 – which can be converted into CBS data – this article provides a practical tool for linkage, summarized in .

Table 3. Calculating the value of past currencies into NIS into present-day currency, or previous dates if selected (summary).

It was also noticed that currently in Israel the interpretation of Ottoman laws is to view them as Palestinian Pounds or Israeli Liras, while in practice, according to the Interpretation Law of 1981, the reference has to be to Ottoman Liras (£T), which also enables a much better linkage.

Another aim of this article, as stated at the outset, was to provide general rules of thumb for understanding the magnitude of obsolete currencies. In this respect the article provides only a half-way position, as the value of money remained fairly stable in the gold-commodity era examined, from 1841 to 1931. During that time, to earn one pound or lira from any kind of formal tender (£T1, £E1, £P1), an unskilled worker had to work between one and three weeks (full-time). For the fiat money, such a rule of thumb cannot be achieved as the value of money changed dramatically through the years.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted under an ISF grant (no.2692/20).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 David M. Sassoon, ‘The Israel Legal System’, The American Journal of Comparative Law Vol. 16, 3 (1968), pp.405–15. Daniel Friedmann, ‘The Effect of Foreign Law on the Law of Israel: Remnants of the Ottoman Period’, Israel Law Review Vol. 10, 2 (1975), pp.192–206. For an updated status of Israel laws, see https://www.nevo.co.il/HakikaSearch.aspx.

2 Şevket Pamuk, A Monetary History of the Ottoman Empire (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2000). Howard M. Berlin, The Coins and Banknotes of Palestine under the British Mandate, 1927-1947 (London: McFarland, 2005), pp.15–22. See more details below.

3 François R. Velde, ‘Lessons from the History of Money’, Economic Perspectives Vol. 22 (1998), pp.2–16.

4 Pamuk, A Monetary History, p.3.

5 Ibid., pp.206–24. Owen, The Middle East in the World Economy (London: I.B. Tauris, 1993), p.104.

6 Pamuk, A Monetary History, p.209.

7 Ibid., p.104.

8 Murat Birdal, The Political Economy of Ottoman Public Debt: Insolvency and European Financial Control in the Late Nineteenth Century (London: Tauris Academic Studies, 2010), p.6.

9 Ali Coşkun Tunçer, ‘The Black Swan of the Golden Periphery: The Ottoman Empire during the Classical Gold Standard Era’, Working Papers of the Department of Economic and Social History at the University of Cambridge 13 (2013).

10 Şevket Pamuk, ‘The Ottoman Economy in World War I’, in Stephen Broadberry and Mark Harrison (eds), The Economics of World War (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), pp.128–29. See also Ali Coşkun Tunçer, ‘Monetary Sovereignty during the Classical Gold Standard Era: The Ottoman Empire and Europe, 1880-1913’, Working Papers, LSE, Department of Economic History, No. 165/12 (July 2012).

11 Sreemati Mitter, ‘A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present’ (Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, 2014), p.28.

12 Şevket Pamuk, ‘Prices in the Ottoman Empire, 1469-1914’, International Journal of Middle East Studies Vol. 36, 3 (2004), pp.451–68 (see especially p.456, 565).

13 Michael D. Bordo and Finn E. Kydland, ‘The Gold Standard as a Rule: An Essay in Exploration’, Explorations in Economic History Vol. 32, 4 (October 1995), pp.436–40.

14 Ben Bernanke and Harold James, ‘The Gold Standard, Deflation, and Financial Crisis in the Great Depression: An International Comparison’, in Ben S. Bernanke (ed.), Essays on the Great Depression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), pp.36–37.

15 Richard N. Cooper, ‘The Gold Standard: Historical Facts and Future Prospects’, Brookings Papers on Economic Activity 1 (1982), p.4.

16 Howard M. Berlin, The Coins and Banknotes, pp.15–17. United Nations Conciliation Commission for Palestine, Note on Currency and Banking in Palestine and Transjordan (United Nations, AAC25W17, 18 July 1949).

17 Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics, Statistical Abstract of Palestine 1944-45 (Jerusalem: 1946), pp.85–86. Government of Palestine, ‘The Palestine Currency Order in Council, 1927’, Official Gazette 193 (16 August 1927), pp.590–92. Note that the reference to 123'27447 grains of standard gold expresses equality with 7.98805 grams composed of eleven parts of fine gold with one part of cheap alloy, i.e. 7.32238 grams of pure gold. See W. Stanley Jevons, Money and the Mechanism of Exchange (New York: Appleton, 1898), p.103.

18 Translation from Hebrew of M. Laniado, Kovetz ha-hukim ha-ʿothmanim ha-nehugim beeretz israel (Jerusalem: Refael Haim Cohen, 1929), p.204.

19 Süleyman Özmucur and Şevket Pamuk, ‘Real Wages and Standards of Living in the Ottoman Empire, 1489-1914’, The Journal of Economic History Vol. 62, 2 (2002), p.301.

20 See, for example, discussion in Government of Palestine, A Survey of Palestine: Prepared in December 1945 and January 1946 for the information of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, 1946), pp.734–45.

21 Deborah S. Bernstein, Constructing Boundaries: Jewish and Arab Workers in Mandatory Palestine (New York: SUNY Press, 2000), pp.29–30.

22 State of Israel, ‘Currency Ordinance No. 19 of 5708–1948’, Laws of the State of Israel: Authorized Translation from the Hebrew (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, various years), Vol. I, pp.43–44.

23 Government of Palestine, The Laws of Palestine in Force on the 31st Day of December 1933 (London: Waterlow & Sons, by Robert Harry Drayton – Legal Draftsman to the Government of Palestine, 1934), p.1036.

24 F. Ongley, The Ottoman Land Code: Translation from the Turkish (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1892). C. G. Walpole, The Ottoman Panel Code 28 Zilhijeh 1274: Translated from the French Text (London: William Clowes & Sons, 1888).

25 C.A. Hopper, The Civil Law of Palestine and Trans-Jordan, Vol. 1 (Jerusalem: Azriel, 1933).

26 M. Laniado, Kovetz ha-hukim ha-ʿothmanim ha-nehugim beeretz israel (Jerusalem: Refael Haim Cohen, 1929), p.3.

27 Ibid., p. xv. A free translation from the Hebrew text: ‘The Ottoman laws referred to in this book were translated into Hebrew from Arabic. Considerable effort has been made to provide a precise translation, and four translations of the Ottoman laws in Arabic, one in French and one in English were used to verify the accuracy of the Hebrew translation. When in doubt, the original source in Turkish was also consulted.’

28 State of Israel, ‘Interpretation Law, 5741 –1981’, Laws of the State of Israel: Authorized Translation from the Hebrew, Vol. 35, Prepared at the Ministry of Justice (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, 1980-1981), pp.276–370.

29 Laniado freely translated Article 8 of the Ottoman Association Law (1909) as stating that the fees to be paid by the members of an association shall ‘not be more than 24 liras from each of them’ – M. Laniado, Kovetz ha-hukim, p.204). The parallel Hebrew translation by Tzvi Preisler and Samuel Bizbhar suggests that such an association may levy ‘not more than 24 liras in gold coins per annum’ – Preisler and Bizbhar, Associations Law (undated translation available at PsakDin website). If we look at the translation in Arabic – the language predominantly spoken in the country when the Ottoman laws were issued – a similar translation may be found: ‘the payment shall not exceed twenty-four gold coins’ – Ghasan Mukhbiyr, Al-jamʿiyat fi lubnan – dirasa qanuniyya (Beirut: wizara al-shʾun al-jamʿiyya, 2002). But, most importantly, the original law in Ottoman Turkish states the maximum sum as twenty-four gold coins (آلتونى تجاوز /altini tecavüz), see .

30 A scanned version of the original law is available from the Turkish National Library Collection via Ankara Üniversitesi Gazeteler Veritabanı: http://gazeteler.ankara.edu.tr.

31 Class action (District Court of Jerusalem) 15544-05-18, Amir Weitmann and others against the Histadrut General Organization of Workers, verdict 2019: https://tl8.me/15544-05-18.

32 Details of the Kohelet Policy Forum’s lawsuit: ‘The Kohelet Policy Forum filed a class action lawsuit totaling more than NIS 4.7 billion against the Histadrut’, 8 May 2018 [in Hebrew].

33 See also Michal Tamir, ‘Overview of Legal Research in Israel’, GlobaLex (2006).

34 State of Israel, Antiquities Ordinances and Rules (Jerusalem: Hacohen Press, 1960), p.11.

35 State of Israel, Ministry of Economics and Industry, ‘Prices of Consumer Goods under Governmental Supervision’: https://www.gov.il/he/departments/dynamiccollectors/food-price-control-search?skip=0 (accessed Dec. 2022).

36 Civil case (Magistrate’s Court of Beersheba District) 23086-03-14, Al-Batal against Al-Ukbi and others, verdict 2016: https://tl8.me/23086-03-14-v-2.

37 Paul Rivlin, The Israeli Economy from the Foundation of the State through the 21st Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2011), pp.34–68.

38 Étienne Laspeyres, ‘Die Berechnung einer mittleren Warenpreissteigerung’, Jahrbücher für Nationalökonomie und Statistik Vol. 16 (1871), pp.296–314. Hermann Paasche, Die Geldentwerthung zu Halle an der Saale in den letzten Decennien dieses Jahrhunderts (University of Halle, 1875).

39 See discussion, for example, in Robert O’Neill, Jeff Ralph and Paul A. Smith, Inflation: History and Measurement (Huddersfield: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), pp.91–130.

40 Jerry Hausman, ‘Sources of Bias and Solutions to Bias in the Consumer Price Index’, Journal of Economic Perspectives Vol. 17, 1 (2003), pp.23–44.

41 Government of Palestine, Statistical Abstract of Palestine 1944-45, pp.112–18.

42 Government of Palestine, A Survey of Palestine, p.745.

43 Robert Szereszewski, Essays on The Structure of the Jewish Economy in Palestine and Israel (Jerusalem: The Maurice Falk Institute, 1968), pp.52–57, 68, 77.

44 Jacob Metzer and Oded Kaplan, The Jewish and Arab Economies in Mandatory Palestine: Product, Employment and Growth (Jerusalem: The Maurice Falk Institute, 1991) [in Hebrew].

45 Olivia Blum, Director of Demography and Census Department at the Israel Central Bureau of Statistic, The Establishment of the National Statistics System in Israel (United Nation: The Statistics Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Documents for the First World Statistics, 2010), p.8.

46 Rivlin, The Israeli Economy, pp.34–68.

47 State of Israel, The Central Bureau of Statistics and Economic Research, Statistical Abstract of Israel 1950/51 (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, 1952), p.72. State of Israel, The Central Bureau of Statistics and Economic Research, Statistical Abstract of Israel 1952/53 (Jerusalem: The Government Printer, 1953), p.95.

48 Rivlin, The Israeli Economy. Donald L. Losman, ‘Inflation in Israel: The Failure of Wage and Price controls’, Journal of Social and Political Studies Vol. 3, 1 (1978), pp.41–62.

49 Olivia Blum, The Establishment of the National Statistics System, p.8.

50 Rebecca Searle, ‘Is There Anything Real about Real Wages?’, The Economic History Review Vol. 68 (2015), pp.145–66.