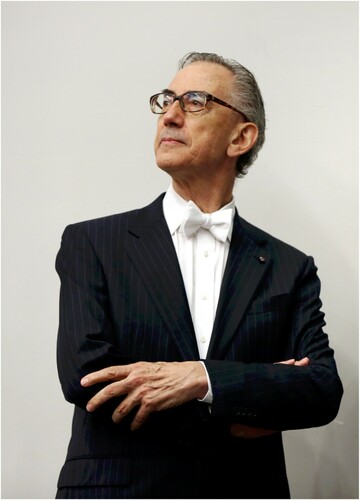

The Editors of Molecular Physics are delighted to introduce this special issue of the journal honouring and celebrating the scientific achievements of Michael L. Klein (see ). The original contributions by his collaborators, colleagues, and friends collected in this issue are but a small testament of the highest regard and esteem in which Mike is held in the broad field of Computational Materials Science.

Figure 1. Michael L. Klein FRS as Dean of the College of Science and Technology, Temple University (2013).

As a true Cockney, Mike was born to Julius and Bessie (née Bloomberg) Klein on City Road in London, within the sound of the bells of St. Mary-le-Bow church, on 13 March 1940. He remained in London during most of the Second World War; the London Blitz made a lasting impact on him. Mike regularly visited his grandmother in South Kensington and often passed by Imperial College of Science and Technology, something which will surely have rubbed off an early interest of science on him.

In the autumn of 1951 Mike attended the Orange Hill Boys Grammar School in Edgware, where he remained until he started reading Chemistry (with a strong self-inflicted dose of Physics) at the University of Bristol in 1958. Mike was awarded a State Scholarship in 1961 to undertake a PhD with Hugh Barron in the area of the thermophysical properties of lattices, which he completed in 1964: the Barron and Klein papers dealing with the elastic behaviour of solids under stress continue to be cited today. Earlier he had married Brenda May Woodman in 1962, whom he had met on arriving in Bristol.

After his PhD Mike spent some time with George Horton in Rutgers working on the theory of highly anharmonic solids and then with Giovanni Boato and his group in Genoa working on physical adsorption. On the birth of the Klein’s daughter Paula in 1965, Mike returned to Bristol as an ICI Fellow, joining the newly created Department of Theoretical Chemistry headed by David Buckingham. There he published his first sole paper (in Molecular Physics) on the quantum second virial coefficient of a two-dimensional Lennard-Jones gas. In 1967, discouraged by the lack of computational resources, Mike left the UK with Brenda and Paula to once again join George Horton at Rutgers, working with Victor Goldman on self-consistent phonon theory.

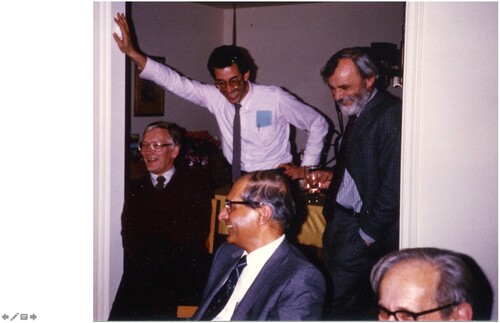

A year later Mike moved to the National Research Council of Canada (NRCC) in Ottawa with the mission of setting up a computational chemistry group. The Kleins' second daughter Rachel was born shortly afterwards in 1969. Mike’s years in Canada were very productive allowing him freedom in broad areas of independent research and collaborative assignments at the Centre Nationale de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) in Paris, one of NRCC’s sister organisations. In Paris Mike established life-long collaborations with Jean-Pierre Hansen, Dominique Levesque, Jean-Jacques Weis, and other visitors such as Ian McDonald (see ) in the burgeoning field of molecular simulation. These visits also enabled him to interact closely with researchers associated with the Centre Européen de Calcul Atomique et Moléculaire (CECAM), including Giovanni Ciccotti, Daan Frenkel, Jean-Paul Ryckaert, and others, starting a productive relationship that continues to the present time. In the 1970s Mike became an Adjunct Professor of Physics at the University of Waterloo and Professor of Chemistry (part time) at McMaster University, a position he held for more than 10 years. In the 1980s, a difficult time for research in Canada, Mike was able to hire brilliant research associates such as Michiel Sprik and Shuichi Nosé, whose pioneering works on electron solvation with path integrals and simulation algorithms have stood the test of time. Roger Impey played a critical role in the group, being responsible for code development and bringing an informatics component. This time at the NRCC also included fruitful collaborations with David Chandler, Ian McDonald, and John Tse. In 1984 Mike was elected as a Fellow of the Royal Society of Canada (RSC).

Figure 2. Mike Klein (standing in the white shirt) with from left to right Herman Berendsen, Aneesur Rahman, Ian McDonald, and Konrad Singer (1984).

Attracted by the vibrant community of theoretical chemists (including Hans Andersen, Bruce Berne, David Chandler, Bill Miller, Peter Rossky, Frank Stillinger, John Tully, and Peter Wolynes, to name but a few), Mike moved to the University of Pennsylvania in 1987. This allowed him to initiate new fields of research, tackling problems in the emerging field of molecular biophysics and the molecular-dynamics simulations of chemical reactions, with a parallel career as director of the Laboratory for Research on the Structure of Matter (LRSM) in 1993 and founder of the Center for Molecular Modeling (CMM) in 1995. At this point of his career Mike built on his collaboration with Michele Parrinello working on studies of small vacuum systems and the acid–base chemistry (proton transfers) of aqueous solutions and other hydrogen-bonded solvents, moving to the study of enzyme catalysis and ion channels. With the Penn CMM researchers, Mike embarked on an ambitious and challenging programme involving coarse-grained models for very large scale biosystems. Their experience and vast database of results of atomistic simulations on amphiphilic systems formed a perfect point of departure and a testing ground for the parametrization of coarse-grained potentials.

During his time at Penn, Mike was showered with honours and awards including: the Aneesur Rahman prize in 1999, the highest award from the American Physical Society (APS) for work in computational physics; Fellowship of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences (AAAS) in 2003; Fellowship of the Royal Society (FRS) in 2003; the Peter Debye Award in Physical Chemistry from the American Chemical Society (ACS) for outstanding research in 2008; his election to United States National Academy of Sciences (NAS) in 2009. In 2009 Mike left Penn for Temple University (see ) to take up the position of Carnell Professor (and now Dean) in the College of Science & Technology and Director of the Institute for Computational Molecular Science (ICMS) where he remains to date.

It is amply apparent from this preamble that Mike is one of the most influential chemical physicists in the field of Computational Materials Science: no single person has contributed more, longer, and on a broader front, to the application of molecular-dynamics and Monte Carlo simulations to practical problems in diverse areas of molecular science. Together with the late Aneesur Rahman (Argonne) and Michele Parrinello (ETH-Zürich), Mike belongs to the small group of brilliant scientists who transformed Molecular Dynamics from a tool in theoretical physics to the workhorse of what is now known as ‘Computational Materials Science’.

Mike’s scientific output is truly phenomenal: he has made important contributions to almost all recent developments in computational materials science. He was the first to apply computer simulation to study the structure and dynamics of crystalline solids at a time when the prevalent opinion was that there was no need for numerical simulation in this field. As a consequence of the leading research carried out by Mike and his collaborators this paradigm has been completely reversed.

His paper with Jorgensen and co-workers on the development of simple potential models to simulate water and aqueous systems remains highly relevant: the paper is the second most cited of all papers published in the Journal of Chemical Physics since 1970 with ∼26,800 citations to date (Web of ScienceTM).

Other examples of areas where Mike has made a lasting impact are path-integral simulations, glasses, and self-assembly in surfactant systems, but for every topic mentioned, we are at risk of omitting a number of others that have been equally important.

This is also true when one considers the seminal contributions that Mike has made to the methodology of computer simulations (many of which have been published in Molecular Physics): his group has been at the forefront in the development and widespread application of constant-pressure and constant-temperature MD (with Nosé), and staging algorithms for path-integral simulations (with Sprik and Chandler). His paper with Nosé on isothermal-isobaric simulations is the sixth most cited of all papers published in Molecular Physics since 1970 with ∼1,950 citations to date (Web of ScienceTM). The fact of the matter is that Mike has been involved in almost all important technical innovations in molecular-dynamics simulations.

In recent years Mike’s research has focused on the numerical simulation of the structural and dynamical properties of biological molecules under realistic conditions. His numerical studies again set standards that other scientists in this field cannot ignore: molecular biologists have already had to revise their view of membrane-protein assembly in the light of the findings from Mike Klein’s simulations.

Equally important is Mike Klein’s role as mentor: he has trained a very large number of early-stage researchers, many of whom have since become leaders in their field. His role was not limited to North America, or Europe. His influence on the emergence of computational materials science in India cannot be overstated.

Computer simulations are transforming the physical sciences. This development is the culmination of half a century of pioneering work. More than anybody else, Mike has played a key role in this process. His impact is lasting and the scope of his work astounding.

Mike is not just a great scientist: he is an avid collector of Japanese ceramics and he is passionate about good food, but even more about good wine, as all those who have had to good fortune to be hosted by him and his late wife Brenda can attest.