ABSTRACT

The purpose of the article is to explore the role of participation in organized leisure activities in young teenagers’ emotional place relations. Data from a survey of students in lower secondary schools were analysed using multivariate linear regression models to address the research questions concerning whether participation in organized leisure activities was associated with more positive community assessments in youths in line with early Nordic welfare theory and the role played by socio-economic hardships and gender in the association. The results showed that for boys there were no indications of a general positive association between participation in organized leisure activities and community assessments, while for girls the association was modest. Students who experienced socio-economic hardships had more negative assessments of community compared with well-off students, even when they participated in organized leisure activities. The author discusses the results according to a welfare theory approach to emotional place relations, supplemented by other theoretical perspectives. From a theoretical perspective, the findings point to social exclusion and inclusion dynamics instead of early Nordic welfare theory approaches to leisure participation. The author concludes that gender, class and school relations are strongly associated with young teenagers’ emotional place relations.

Introduction

The way people think and feel about places has been an essential concern of human geography and other social sciences for decades (Holloway & Hubbard Citation2001; Antonsich Citation2010; Lewicka Citation2011; Williams Citation2014; Berg Citation2016). People–place relationships cover a variety of practical, social and psychological dimensions, from educational and occupational links to emotions relating to places or the way meaning applies to places. Emotional place relations vary in both intensity and value (Williams Citation2014; Vestby Citation2015), but it is often assumed that participation in leisure activities strengthens place relations and renders them more positive (Bæck Citation2004; Sinkkonen Citation2012; Hixson Citation2013).

In this article I explore the role of leisure in emotional place relations by using an indicator of young teenagers’ assessments of their local community, and specifically address the question of whether their participation in organized leisure activities is associated with positive community assessments. Furthermore, I explore the roles of socio-economic hardships and gender in the associations. Previous studies have revealed that young people from families with lower socio-economic status are less satisfied with their local surroundings compared with others (Bakken et al. Citation2016), and girls in general tend to have more negative emotional place relations compared with boys (Frønes Citation1993; Bæck Citation2004; Dallago et al. Citation2009; Øia & Fauske Citation2010).

As everyday life encounters, leisure activities contribute to youths’ place experiences and social experiences (Trell et al. Citation2012). The links between leisure and welfare have been supported by customary thinking among scholars and the wider public (Allardt Citation1975; Øia & Fauske Citation2010; Barne-, likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet Citationn.d.). Since World War II, the dominating approach to Nordic childhood has been that outdoor leisure (preferably in natural environments) evokes positive emotional place relations (Gullestad Citation1997). The welfare policy of ensuring leisure participation for vulnerable groups of youths is frequently mentioned in the literature (Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson Citation2014; Fløtten & Hansen Citation2018; Barne-, likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet Citationn.d). The rationale is that young people who participate in organized leisure activities become embedded in their community and in turn are protected against the negative impacts of poverty in their youth. Accordingly, in a cross-sectional study of young teenagers, I examined whether there were indications of the beneficial effects of leisure and, if so, under what conditions.

The target population in the study was young teenagers in the age range 13–16 years who were living in an old industrial stronghold in south-east Norway. The analysis drew on data from standardized school surveys in two neighbouring municipalities (N = 2284): ‘Ung i Skien’ conducted in 2011 and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’ conducted in 2012. The surveys formed part of a national data collection system (Ungdata) organized and conducted by the Norwegian Social Research Institute, NOVA,Footnote1 and were jointly financed by the Norwegian Directorate of Health, the Ministry of Children, Equality and Social Inclusion, and the Ministry of Justice and Public Security.

A place-based approach to community

The Dictionary of Human Geography defines community as a group of people who share culture, values and/or interests based on social identity and/or territory (Gregory et al. Citation2009, 103). The term ‘community’ is often used interchangeably with ‘neighbourhood’ or it is prefixed with the word ‘local’ to underline proximity, and many scholars see community as a dimension of place (Silk Citation1999; Latham et al. Citation2009).

Community is a controversial concept within the social sciences (Latham et al. Citation2009), and part of the controversy relates to the fact that groups who share culture, values or interests may be scattered all over the globe and do not share the same territory. In addition, the connotation of clear-cut borders, whether cultural or territorial, is difficult to combine with relational understandings of place as well as culture. According to Massey (Citation1994), community and place are incompatible: community can never be place-based. A related problem concerns social bonds and conflicts. The static nature of the concept of community makes it difficult to incorporate processes of social exclusion in analyses, in common with emotional contrasts such as belonging and ambivalence (Berg Citation2016). Historically, the concept of community rests in the idea that social organizations were characterized by harmony and cooperation in tight-knit fellowships, in contrast to modern urban society (Latham et al. Citation2009).

Despite the conceptual challenges, in this article I adopt a place-based approach to community. As place-based, a community encompasses the social, the built and the natural environment, including landscapes and institutions such as schools and leisure organizations. Community extends beyond the immediate neighbourhood, but it has relative borders (Berg Citation2016). The integration of the social and the territorial can be useful as an operationalization of the context of children’s and young people’s everyday lives (Vestby Citation2003; Dallago et al. Citation2009; Coulton & Spilsbury Citation2014; Brattbakk & Andersen Citation2017). Furthermore, children’s well-being is affected both by objective characteristics and subjective experiences of their local surroundings (Coulton & Spilsbury Citation2014).

Emotional place relations in a welfare perspective

Community perceptions represent an important welfare dimension in youth and the topic is in need of further research (Coulton & Spilsbury Citation2014; Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson Citation2014). Accordingly, in this article I use young teenagers’ community assessments as subjective indicators of their welfare. In doing so, I employ a welfare perspective on emotional place relations.

I define welfare as a paramount concept for living a good life in a broad sense, including both objective and subjective aspects of life (Sletten Citation2011, 7; Barstad Citation2014, 15). To treat emotional place relations as welfare is in accordance with tradition in Nordic welfare theory (Allardt Citation1975; Barstad Citation2014).The approach can also be linked to the quality of life tradition within welfare research (Sletten Citation2011), in which both well-being in local communities and satisfaction with local communities are important specifications. In this tradition, positive community assessments represent emotional resources. Allardt (Citation1975) describes an individual’s social relations in community as a basic human need and includes that need in his tripartite model of welfare (‘to have, to love, to be’) as part of the love dimension: the need for fellowship and belonging.

Research on emotional place relations among youths

In cutting across the distinct theoretical and methodological traditions of human geography and environmental psychology, research on emotional place relations centres on a few main concepts: sense of place, place identity, place attachment, and place belonging (Antonsich Citation2010; Lewicka Citation2011; Williams Citation2014; Vestby Citation2015; Berg Citation2016). Berg (Citation2016, 35) describes the concepts as interrelated and partly overlapping dimensions of emotional place relations, specifically in the case of ‘place belonging’. Thus, key concepts used to describe emotional place relations seem to reflect a scale of emotional intensity, ranging from general awareness and meaning-making in a sense of place, identification with a place, to affective feelings of being bonded and of being at home and at ease in place attachment and belonging (Lewicka Citation2011; Vestby Citation2015). According to Vestby (Citation2015), such emotions can be directed towards different place types: natural, physical and social. This corresponds closely with the place-based understanding of community applied in this article. I treated young teenagers’ community assessments as here-and-now encounters, which Williams (Citation2014) calls evaluative judgments, with regard to what it is like to live where they live.

In empirical research on people–place relations, both definitions and measures of emotional relations vary (Lewicka Citation2011). One of the consequences of the variation is that it is difficult to establish causal directions in associations between different types. Subjective experiences of community, place attachment and belonging are generally interwoven (Vestby Citation2003; Citation2015; Bæck Citation2004; Lewicka Citation2011). Furthermore, equality and cohesion are important elements in community attachment (Vestby Citation2015).

Additionally, community perceptions of satisfaction and attachment are associated with both subjective well-being, which is a subdomain of quality of life (Theodori Citation2001; Næss Citation2011; Coulton & Spilsbury Citation2014), and perceived safety (Dallago et al. Citation2009). People who experience places as safe tend to develop emotions of a sense of belonging towards those places (Lewicka Citation2011; Vestby Citation2015). With regard to associations between emotional place relations and other aspects of everyday life for young people, Sinkkonen (Citation2012) found that attachment to the home district in Finland had four dimensions: family and roots in the district; sense of participation, especially in the home municipality; enjoyment of school; and a tendency to prioritize future place of residence over choice of profession. Sinkkonen’s findings are supported by findings from qualitative research on youths and place relations (Paulgaard Citation2012; Citation2016; Trell et al. Citation2012). However, negative or ambivalent emotional place relations may also occur in situations characterized by emotional stress, poverty or social problems (Manzo Citation2014).

Proximity is a dimension of young people’s access to social arenas. For example, Trell et al. (Citation2012) found that distance affected young people’s attachment to place in Estonia. Furthermore, both objective and subjective aspects of school are known to be important for young people’s sense of local belonging (Sinkkonen Citation2012; Gulløy Citation2017). Also, young people tend to develop increasingly more negative place relations as they grow older (Dallago et al. Citation2009; Bakken et al. Citation2016).

It is generally acknowledged that young girls have weaker and less positive place relations compared with boys, at least to the places where they grow up (Frønes Citation1993; Bæck Citation2004; Dallago et al. Citation2009; Øia & Fauske Citation2010; Sinkkonen Citation2012; Bakken et al. Citation2016). However, Norwegian studies of residential preferences and mobility in youth have added more specific nuances to this picture. Villa (Citation2005) found that girls in rural contexts were more ambivalent toward rural living, while Bæck (Citation2004) found differences in how girls and boys perceived cities and the lifestyle they offered. The gendered pattern of place relations is often explained within a theoretical framework drawing on theories of globalization or late modern placeless identities, in which girls come to customize cosmopolitan attitudes and values more often than boys do (Paulgaard Citation2016). The female drive for education and welfare services, as well as what Bæck (Citation2004) calls the urban ethos, are important elements in the scepticism towards the local observed among girls and young women.

Place images play an important role in emotional place relations, as does place identity, which concerns the extent to which a person’s identity is constructed in relation to their place experiences and sentiments (Lewicka Citation2011; Ruud Citation2015; Berg Citation2016). Shared social identities are developed through social relations, but geographers are concerned about also the process of identification with or belonging to a particular place (Ruud Citation2018). In her works on young people and place, Paulgaard questions evolutionary perspectives on both globalization and youths’ transition to adulthood, a way of thinking that apparently leads to inevitable outcomes of diminishing place identities (Paulgaard Citation2012; Citation2015; Citation2016). In building on thinkers such as Bourdieu, Massey and Simonsen, she combines a constructivist approach to place with a focus on learning communities (Paulgaard Citation2012; Citation2015). Social participation involves learning in a broad sense outside educational institutions – the process whereby young people adopt ways of thinking and doing from family, friends, neighbours, and relatives. An example of such learning processes is the development of skills for dealing with the local natural environment. Paulgaard (Citation2012) adopts the idea from Massey (Citation1994) that places are hierarchical and vertically linked together, and the sum of history shines through onto place relations. In line with this thinking, functional and emotional place relations can be termed a specific type of localized social capital (Paulgaard Citation2012; Citation2015). The point is that certain social networks, family relations or ways of living represent potentially valuable resources, a point that has been explored by Middleton et al. (Citation2005) and other scholars. The value of the resources depends on where young people live.

To study stability and change is challenging in terms of identity conceptualizations, both in persons and in places (Ruud Citation2018). Constructive approaches to place comprise studies of how young people do place, belonging and identity through relations of inequality and power, and most of the studies are based on qualitative research strategies. The way descriptions construct in-place groups and out-of-place groups within different types of arenas is important (Vestby Citation2003; Ruud Citation2018). Furthermore, place relations intersect with educational positions (Fosso Citation2004) and gender (Paulgaard Citation2016).

To summarize, place experiences during leisure time are important elements in place-making (Holloway & Hubbard Citation2001). However, is interesting to explore from both a theoretical perspective and a welfare perspective whether leisure participation moderates or strengthens social and gender differences in place relations. In the next section, I restrict my references to participation in leisure arenas to voluntary organizations.

Leisure as arena for integration and welfare

Leisure organizations centre on voluntary, pleasure-driven activities: structured, regular, and adult-supervised, with a more or less prominent focus on skills building (Mahoney et al. Citation2005). Almost all young Norwegians have been involved in leisure organizations at one point in time during their youth, and approximately two-thirds of Scandinavian youngsters participate in leisure activities regularly, although the degree of their participation tends to decrease during their teenage years (Bakken et al. Citation2016; Olsen et al. Citation2016). In the Nordic countries, boys more often become involved in sports, whereas girls have higher attendance rates in arts and other cultural forms of leisure activities as well as religious organizations (Øia Citation1998; Bakken et al. Citation2016; Olsen et al. Citation2016).

Both recruitment to and dropout from leisure organizations is socially skewed in Norway and elsewhere in the Global North. Young people who grow up in families that experience economic problems exercise or participate in organizations less often than other young people (Fløtten & Kavli Citation2009; Sletten Citation2010; Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson Citation2014; Sheerder & Vandermeerschen Citation2016; Epland & Kirkeberg Citation2017). With regard to sports, recent Norwegian research has indicated that social differences probably increase due to a combination of increased costs, professionalization of leisure sports for youths, and high demands in terms of parents’ involvement (Å. Strandbu et al. Citation2017).

The idea that there is a positive association between participation in organized leisure activities and emotional place relations can be traced to the capability approach to welfare: individual welfare accumulation is a result of access to various arenas (Sletten Citation2011). Within early Nordic welfare theory, the two main activity spheres were leisure and neighbourhood (Ringen Citation1976). Thinking in terms of arenas provides a powerful picture that combines the idea of a social stage (a social ‘arena’) with the idea of a physically constituted stage (a local ‘arena’). The concept of social capital partly applies to this perspective, namely the idea that leisure arenas provide people with individual resources in the form of social networks (Sletten Citation2011). Friendship and companionship are important dimensions of leisure participation. Furthermore, leisure organizations introduce children and young people to the wider community and provide a base from which they can establish localized social capital (Øia & Fauske Citation2010; Paulgaard Citation2015).

A theoretical distinction exists between leisure arenas as capability structures for individual resource accumulation and leisure arenas as centres for integration into society (Coleman Citation1961; Gjerustad & Sletten Citation2005). Leisure is widely assumed to have an integrative function (Fløtten & Kavli Citation2009; Øia & Fauske Citation2010), whereby young people become socialized into full-grown members of society. Furthermore, leisure is a source of enjoyment, well-being, improved psychological health, and school performance (Coleman Citation1961; Øia & Fauske Citation2010; Bakken et al. Citation2016; Olsen et al. Citation2016). Thus, in some cases, leisure participation may have a decisive impact on young people’s lives, as demonstrated by the potential of mass sport to transform ‘slum kids’ into billionaires.

Within social work and social pedagogy, it is common to see leisure as enabling, with the potential for transformative self-development at the individual level (Fuglestad et al. Citation2015; A. Strandbu et al. Citation2016). In contrast to work or school, leisure represents an arena for development of alternative forms of competence and skills (Mahoney et al. Citation2005; Furlong Citation2013). Leisure participation may affect individual psychological processes that are closely linked to identity construction in youth (Fosso Citation2004; Blackshaw Citation2013; Coulton & Spilsbury Citation2014). It is difficult to draw a sharp distinction between individual and social dimensions of identity work (Holloway & Hubbard Citation2001). In youth research, the identity concept traditionally relates to transition and subculture (Furlong Citation2013), with connotations of ideas of universal human development. However, Jenkins (Citation2014) argues that identity is both about being and becoming; it is never static but is always interacting with similarities and differences in relation to something other.

Thus, a range of theories hold that participation in organized leisure activities is positive for participants, both personally and socially. This is confirmed by the results of studies in which young participants voiced their own reasons for participation (Smette Citation2015; A. Strandbu et al. Citation2016; Å. Strandbu et al. Citation2016). Phenomenological approaches to place build on the same way of thinking, whereas knowing surroundings well and reacting emotionally to them initiate a sense of place (Holloway & Hubbard Citation2001; Vestby Citation2015). This model forms the basis for the analyses reported in the Results section of this article.

Other theoretical approaches have led to alternative understandings of leisure and place relations. Critical leisure theories see participation as potentially oppressive. Leisure organizations, in particular sports organizations, are accused of upholding class and ethnic inequalities (Furlong Citation2013; Å. Strandbu et al. Citation2017). According to Massey (Citation1994), power and divisions of gender and social inequality are fundamental to the way people experience place (Ruud Citation2015; Berg Citation2016). In this article, I discuss findings from the analyses reported in the Results section according to critical theory as well as according to a welfare approach.

The case region: an industrial stronghold in Norway

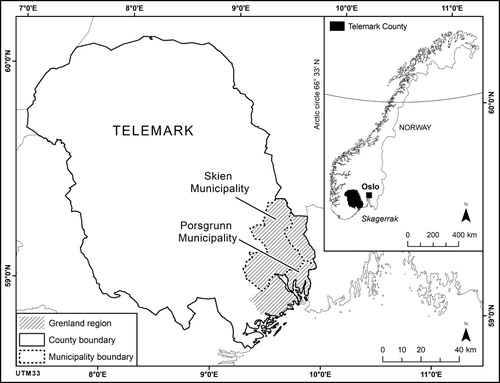

The case region comprised two neighbouring municipalities, Skien and Porsgrunn, within the industrial region of Grenland, in the county of Telemark, in south-east Norway (). Grenland is a semi-urban agglomeration that extends from the surrounding hinterland of a fiord towards the Skagerrak, a strait between Norway, Sweden and Denmark. The two municipalities have a joint population of 90,600 and the Grenland region has a population of 107,100 (Statistics Norway Citation2019). For more than a century, traditional process manufacturing dominated Grenland, which is now marked by a process of deindustrialization (Kjelstadli Citation2014; Underthun et al. Citation2014). In a Nordic context, the case region is representative of many middle-sized local communities with structural problems. Welfare payments are relatively high, as is the share of children living in low-income households and households in receipt of social benefits (Epland & Kirkeberg Citation2017; Statistics Norway Citation2017).

Fig. 1. Location of Skien Municipality, Porsgrunn Municipality and the Grenland region in the county of Telemark, Norway

Grenland has a rich supply of voluntary leisure organizations, and the local culture reflects its position as one of the largest industrial regions in the country (Kjelstadli Citation2014). Many leisure organizations in the region have a long local history, and sports organizations in particular are referred to as important contributors to place-based identity (Schrumpf Citation2006). Sport’s integrative power at the local level in Grenland is highlighted in historical sources dating from 1880 onwards (Schrumpf Citation2006). It is generally accepted that in first half of the 20th century sports clubs were venues where young people from different social classes could meet and develop friendships and social networks (Schrumpf Citation2006; Olstad Citation2014). Local sports clubs had specific integration programmes for marginalized youths as early as the 1950s (H. Mæland, personal communication 2016). For this reason, I regarded Grenland a suitable setting for a study of youths’ participation in leisure activities and their place relations. Voluntary organizations in Grenland have developed strategies to meet the challenges of childhood and youth poverty (Hagen Citation2018). Currently, the question is whether participation provides welfare gains in the form of improved place relations for all or leads to welfare gains primarily for the well-off.

Data and methods

The majority of lower secondary school students (aged 13–16 years) in Skien Municipality and Porsgrunn Municipality were invited to participate in the school surveys conducted by NOVA in February and March 2011 and November 2012 respectively. The response rates were high: 84% in Skien Municipality and 88% in Porsgrunn Municipality. After data cleaning (removal of incomplete questionnaires, students with implausible answers and students with missing values on main variables), the net sample comprised 2284 students, which represented 68% of the gross student population in the two municipalities.

The surveys were approved by the Norwegian Data Protection Authority. Prior to the surveys, parents and students had received a letter that included information about the survey, implementation procedures and precautions to protect privacy. To protect the students’ privacy when they filled in the web-based questionnaire, the school staff were requested to ensure that there was adequate space around each computer. The surveys were voluntary and parents or guardians had the right to refuse to allow their child to participate.

Analytical approach

The purpose of analysing the survey participants’ responses to NOVA’s survey questions was to find associations between the participants’ community assessments and leisure, and identify indications of social processes that might have affected the way they (i.e. the young teenagers) experienced community as a concrete and specific context for everyday life, such as through participation in organized leisure activities and attendance at school. Other elements were biographical, such as the family’s local history, social problems, or social resources in young people’s lives that might have been constraints or assets in difficult life situations, as well as in young people’s everyday experiences of well-being.

I analysed the results relating to the survey questions by using multivariate linear regression (ordinary least squares, OLS). Five different assessments were included as items in the community assessment index which made up the dependent variable of the analyses. In this section I describe how each assessment reflects dimensions of the main place concepts of sense of place, place identity, place attachment, and place belonging. To explore the association between leisure and the dependent variable of community assessments, participation in organized leisure activities, self-perceived poverty and gender were used as key independent variables. The software used for the analyses was SPSS version 25, and STATA version 15.0 for the regression model included in .

Table 4. Robustness checks (Based on data from the projects ‘Ung i Skien’ and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’, conducted by NOVA in 2011 and 2012 respectively)

For Model 1, an indicator for participation in organized leisure activities was used to determine whether there were any positive associations between that type of activity and community assessments. According to Lewicka, using activity as a predictor of subjective indicators such as emotional place relations introduces the possibility of selection effects, as those who give comparatively more positive community assessments may be more active in organized leisure pursuits, which in turn may cause variations in the dependent variable (Lewicka Citation2011). One way of handling such effects in cross-sectional data is to control for variations in the dependent variable according to certain theoretical patterns. In my study, selection effects were neutralized partly by differentiating between subgroups (poor/non-poor and girls/boys) and partly by introducing significant control variables.

In Model 2, the effects on the dependent variable were calculated from variables that represented socio-economic hardships, specifically the students’ perceptions of such hardships. To explore this issue, I also included corresponding interaction variables for different levels of self-perceived poverty in combination with participation in organized leisure activities. In Model 3, gender was introduced, along with an interaction variable for being a girl and participation in organized leisure activities in order to compare associations between such activities and community assessments for girls and boys.

A number of other factors are known to play important roles in defining young people’s community assessments and in this respect school relations and proximity to friends and family are of particular relevance (Lewicka Citation2011; Sinkkonen Citation2012; Gulløy Citation2017). For that reason, I added to Model 4 control variables for school satisfaction and school problems, proximity to friends and family, single-parent households, age, psychological health, immigrant background, and municipality.

Finally, as robustness checks, I ran two regression models as alternatives to Model 4. The first regression model was an OLS, in which I replaced the subjective indicator for poverty with an objective indicator of socio-economic status, and the second was a median regression model.

Dependent variable: an index for community assessments

The dependent variable was constructed as an additive index consisting of five items, all of which referred to the local area in which the participant lived: questions about satisfaction and well-being in the community, the wish to see their children grow up in the same area as they lived, disposition to stay or to move, and perceived safety. The combined measure covered different affective dimensions of the young teenagers’ emotional place relations, as advised for place attachment and quality-of-life research (Næss Citation2011; Williams Citation2014). Evaluative judgments have an element of elective choice, whereas bonds reflect deeper, more intuitive feelings towards places (Williams Citation2014). An immediate experience of feeling well in the local residential area was indicative of well-being and a sense of place. A cognitive appraisal of a local area’s qualities for a young person reflected that person’s sense of place, as well as being a subdimension of global life satisfaction. Perceived security at night reflected a security dimension and sense of place; emotional and/or cognitive assessments of a person’s inclination to remain living in that place reflected attachment and belonging. Lastly, a local area’s suitability for raising children reflected place attachment and a sense of belonging. Thus, the index measured young people’s attitudes and preferences towards the places where they lived, but also deeper emotional bonds.

All items were coded from 0 (very negative) to 4 (very positive); the mid-value of 2 was assigned to the response neither positive nor negative or similar. The higher the value on the additive index (0–20), the more positive was the student’s community assessments. The frequency distributions for single items included in the index are listed in .Footnote2

Table 1. Frequency distributions for single items in the additive index for community assessments (N = 2284) (Based on data from the projects ‘Ung i Skien’ and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’, conducted by NOVA in 2011 and 2012 respectively)

Single items correlated well with the combined index (Cronbach’s alpha 0.75), and all items correlated in the same direction with the included independent variables. To a large extent, the index was an acceptable approximation of the students’ emotional relations to the places where they lived,Footnote3 although the rough measure required careful interpretation of the distances between scores.

Key independent variables for participation in organized leisure activities, self-perceived poverty and gender

Frequency distributions, mean values and standard deviations for key independent and control variables are presented in . None of the independent variables correlated strongly with the dependent variable; the strongest was r = 0.44 for school satisfaction.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for all independent and control variables: percentage, N, and M and SD on the dependent variable (N = 2284) (Based on data from the projects ‘Ung i Skien’ and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’, conducted by NOVA in 2011 and 2012 respectively)

A combined measure was constructed for participation in organized leisure activities, based on questions about activity levels in the following types of organized youth leisure settings: sports clubs or organizations, motor clubs, cultural clubs or organizations, bands, choirs, orchestras, and other organizations. The leisure types represented different traditions in terms of place and community relations, and while some correlated more highly than others, the combined measure appeared to be quite effective, given the analytical focus on organized leisure activities as social participation in contrast to isolation.

For all items, the question was: How many times during the last month have you participated in activities, meetings or rehearsals in the following organizations, clubs or teams? The response alternatives were: ‘Never’, ‘1–2 times’, ‘3–4 times’, or ‘5 times or more’. Each participant’s maximum value among the single items was chosen for the combined measure. The results of the bivariate analyses showed deviational response patterns among vulnerable subgroups.Footnote4 Therefore, the regression analysis included participation in organized leisure activities as a dummy variable, for which 1 represented a threshold level of monthly participation, while the reference group comprised students who were more or less inactive.

The proxy variable for self-perceived poverty was constructed on the basis of the following question: Has your family been well-off or poor in the last two years? Response alternatives were constructed as a set of dummy variables, with 0 assigned to students who considered themselves well-off in the entire period (i.e. ‘the last two years’).Footnote5 For each dummy variable, a corresponding interaction variable was included, representing students in each group who were active in organized leisure activities at the same time. The aim was to address the research question concerning the role of socio-economic hardships in community assessments.

Gender was measured by a dummy variable, with 1 assigned to being a girl. I also included an interaction variable for being a girl and participating in organized leisure activities.

Control variables

To measure school-related problems, a combined variable was constructed from the following items: During the last year (i.e. the last 12 months), have you done or experienced any of these: 1. Had a severe quarrel with your teacher? 2. Been expelled from the classroom? 3. Been sent to the headteacher because you did something wrong? In the analyses, a dummy variable was constructed, with 1 assigned to students who answered ‘two times’ or more to at least one of the questions, and 0 assigned to all other students.

School satisfaction was measured by the following question in relation to questions on different aspects of student life: How satisfied or dissatisfied are you with your school? In the regression analyses, the values ranged from ‘Very dissatisfied’ (0) to ‘Very satisfied’ (4).

A variable for travel distance to friends was constructed from the question: When you are at home, can you walk or bicycle to meet friends or do you need to be driven? If you live with your mother and father separately, please think about the place you spend most of your time. A dummy variable was used, with 1 assigned to students who had to be driven to be with their friends, while the reference group comprised all other students.

A variable for proximity to extended family members was measured by the question: Other than your mother, father or grandparents, do you have any adult relations living in [municipality name]? A dummy variable was constructed, with 1 assigned to those who responded ‘Yes’.

A variable for living with either one parent or neither parent was constructed from the question: Do you live with both of your parents? The dummy variable of 1 was assigned to students who responded ‘No’.

Age was measured by using school grades in a set of two dummy variables for being in the 9th and 10th grade respectively. The reference group was the 8th grade.

A dummy variable was used to control for indications of depressive moods, with 1 assigned to students who responded ‘quite a bit bothered’ or ‘extremely bothered’ to all of the following questions relating to emotions, which NOVA based on Kandel & Davies (Citation1982): During the last week, have you been bothered by any of these: 1. Felt too tired to do things; 2. Felt unhappy, sad, or depressed; 3. Felt hopeless about the future; 4. Felt tense or keyed up; 5. Worried too much about things. The reference group comprised students who lacked indications on all five questions.

I further controlled for immigrant background by assigning 1 to students who responded ‘Yes’ to the following question: Were both your parents (mother and father) born outside Norway? A final control related to municipality. To check for any possible effects of locality or survey timing, I included a dummy variable for students from Porsgrunn Municipality, with students from Skien Municipality as the reference group.

Results

In this section, I present the results relating to associations between participation in organized leisure activities and young teenagers’ community assessments. The results for Model 1 () showed that the estimate for the young teenagers’ (i.e. students) community assessments became more positive when they regularly participated in organized leisure activities. Model 2 provided estimates for effects of self-perceived poverty. In addition, interaction terms provided estimates of community assessments for the students who participated in organized leisure settings and perceived their families as mainly well-off, neither well-off nor poor, or poor. The effect of these additions was to boost the estimate of well-off students who participate in organized activities. For inactive students, there was a negative association between the dependent variable and perceptions of not being well-off: the more those students perceived their families as having been poor during the previous two years, the more negative were their assessments of community. Inactive students who perceived themselves as poor exhibited more negative community assessments at more than four points on the dependent variable, which was a surprisingly strong effect.

Table 3. Hierarchical linear regression results (ordinary least squares), and effects of participation in organized leisure activities on community assessment index (0–20: higher = more positive) before and after control for self-perceived poverty (Model 2), gender (Model 3) and control variables (Model 4), with unstandardized coefficients, standard errors and significance levels (Based on data from the projects ‘Ung i Skien’ and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’, conducted by NOVA in 2011 and 2012 respectively)

With regard to the possible interaction between participation and poverty, the coefficient for students who were mainly from well-off families and active in leisure organizations showed a significant negative association, which reduced the initially positive effect of the coefficient for activity on community assessments. The two remaining interaction variables, which represented active students who did not perceive themselves as well-off, proved insignificant. However, it should be emphasized that some of the subgroups were quite small, and that interactions between poverty and participation should be tested in larger samples. To summarize, Model 2 showed that inactivity was generally associated with more negative assessments of community, with a corresponding pattern for self-perceived poverty, while participation seemed to correspond to improve assessments only when students considered themselves well-off. In Model 2, R2 rose to 0.08, which was significantly stronger than in Model 1 (F change value in Model 2: 25.07, p < 0.001).

When gender was introduced into Model 3, community assessments were less positive for girls than for boys. The coefficient for inactive well-off girls was negative, indicating that inactive girls exhibited more negative assessments than inactive boys. The observed change in community assessments for active well-off girls was not powerful enough to be classified as a significant positive association. When taking gender into account, I noted that variables representing self-perceived poverty were reduced. Associations between poverty and community assessments were to a certain degree mediated by differences between girls and boys. R2 rose to 0.12, indicating that the introduction of gender contributed to explanations of the variance in Model 3 (F change value: 43.53, p < 0.001).

After including the control variables in Model 4, the main coefficient for boys’ participation in organized leisure activities became insignificant, with a similar tendency for all interaction variables representing active boys who were not well off. Boys who participated did not exhibit significantly stronger positive community assessments than boys who were inactive when all other variables were taken into account. The positive coefficient for being a girl who participated in organized leisure activities thus became significant, indicating that only girls who participated in such activities had expressed more positive assessments, all other things being equal. However, the coefficient for girls’ participation in organized leisure activities rose only modestly. To a large extent, inactive girls reported fewer positive community assessments compared with boys. The negative coefficients for self-perceived poverty were reduced in Model 4, although to a less extent than might be assumed, given the huge increase in R2 (from 0.12 to 0.33) (F change value in Model 4: 65.66, p < 0.001). Students who perceived themselves as poor exhibited a strong negative turn in their assessments.

Additionally, Model 4 showed that several of the control variables exerted significant effects on the dependent variable. Students who experienced serious conflicts at school exhibited more negative community assessments compared with students who had not experienced such problems: the more satisfied students were with their school, the more positive were their assessments. When students had to be driven to meet their friends, their assessments were weaker, and this was also the case for those who lacked an extended family in the same municipality or lived in single-parent households. Students with indications of depressive moods exhibited substantially more negative community assessments compared with students with no such indications.

Potential interactions and reverse causations

The results indicated that some of the control variables interacted with gender in a fundamental way. Furthermore, reverse causation seemed possible in relation to two control variables with relatively strong effects: school satisfaction and depressive moods. With regard to the former, students might have been more satisfied with their school because they were initially more positive towards the local area and tended to participate more often in organized leisure activities. The bivariate analyses revealed no gender differences in the measured activity levels or in satisfaction with school. For a more detailed check, I replicated Model 3 and introduced one control variable at a time. The indicator for school satisfaction introduced major changes in the relationships between participation, gender and community assessments: associations between participation and assessments became significant for girls only. The gender effect revealed in Model 4 concerned how participation, school satisfaction and community assessments were related, for both boys and girls. As the study design did not allow for further analyses, no conclusions could be drawn about possible reverse causation, although it seemed likely that reverse causation could have occurred.

Community assessments that were more negative than others might have contributed to the results relating to the students’ depressive moods. The bivariate correlation between variables for participation and depressive moods was insignificant. When the indicator for depressive moods was removed from Model 4, the association between participation in organized leisure activities and community assessments persisted. I could not rule out reversed causality for this particular association in the sample, but in the model, participation in organized leisure activities had an independent positive effect on community assessments, while indicators of depressive mood had an independent negative effect. The results for boys and the results for girls were almost similar.

Finally, students from Porsgrunn Municipality made slightly more negative community assessments than did students from Skien Municipality. To explore whether this might have been caused by measurement errors or substantial differences between students in the two municipalities, I compared bivariate and multivariate regression models (results not shown). The observed difference in community assessments between the two municipalities in the multivariate regression model reflected differences in school satisfaction: students in Porsgrunn were substantially more satisfied with school compared with those in Skien, thus creating a spurious association between municipality and community assessments. Even when school satisfaction was included in Model 4, a major share of the total variation in the dependent variable remained unknown.

Robustness checks

To check whether the main results from the OLS regression model were replicated in other specifications, I ran two alternative regression models. First, I ran the regression model with objective measures of poverty rather than subjective ones, to confirm the validity of using a subjective indicator of poverty (, Column ‘Test of poverty measure’). Three different variables indicating household payment problems yielded the same main results as the analyses described in the Results section (repeated in , Column ‘Model 4’). I concluded that the subjective indicator of poverty was an acceptable indicator of socio-economic hardship.

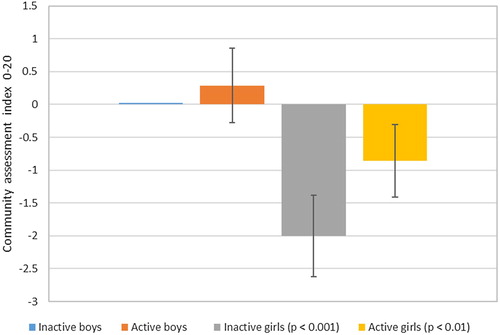

To address the challenges of non-normality and heteroscedasticity, I ran a median regression model to estimate the dependent variable in terms of median values rather than means. Variables that yielded insignificant results in Model 4 were removed. The results presented in the column ‘Test of regression slope’ in show that the main conclusions drawn from Model 4 were strengthened by the results obtained from the median regression model. Furthermore, participation in organized leisure activities showed a general positive association with community assessments when measured as median scores, but an interaction effect was observed between participation and gender. When controlling for school satisfaction, I found that boys who participated in organized leisure activities did not return significantly higher median values on the community assessment index than did non-participant boys. Girls were initially more negative but returned significantly higher median values on the assessment index for joining organized leisure activities compared with boys who did not join them. It was noteworthy that the confidence intervals between active and inactive girls barely overlapped (). By implication, while the substantial difference in community assessments between girls and boys held regardless of participation, the difference in assessments between those inside and outside organized leisure activities was sensitive to model specifications.

Fig. 2. Effects of participation in organized leisure activities for young teenage boys and girls, with reference to inactive boys

Underrepresentation of vulnerable groups might have contributed to a certain positivity bias on the dependent variable. Alternative regression models (not shown) to Models 1–4, with dummy variables for missing observations, returned insignificant p-values and produced only minor changes in key coefficients and t-values compared with the original models.

Discussion

The results and their significance can be summarized as follows:

For the students (young teenagers in the age range 13–16 years) in the Grenland region who participated in organized leisure activities, the bivariate analyses showed that they exhibited more positive community assessments compared with the students who did not participate in such activities, which is in line with common thinking as well as a number of theoretical perspectives. However, in the multivariate analyses the association was unstable and it related both to gender and to subjective experiences of school. When school satisfaction was taken into account, the general positive association between participation and community assessments was valid only for girls. The association was quite modest and vulnerable to model specifications.

Students who experienced socio-economic hardships provided more negative assessments of the community compared with well-off students. The more often students felt relatively poor, the more negative they were.

Girls gave more negative assessments of community compared with boys, but reported slightly improved assessments when they participated in organized leisure activities. In the case of boys, the association between participation and community assessments was spurious according to a model specification that controlled for socio-economic hardships, school relations, proximity to family and friends, and indications of depressive moods.

Gender moderated the negative association between community assessments and being poorer. Girls perceived themselves as poor slightly more often compared with boys.

School relations and proximity to friends and family seemed to have played an important role in the students’ community assessments in terms of both direct and indirect effects.

Main findings according to a welfare approach

My study findings support the results from recent analyses of Ungdata survey material from Norway concerning social differences in young people’s community satisfaction (Bakken et al. Citation2016). I found that students who experienced poverty and students who lived in single-parent households had more negative community assessments compared with other students.

Furthermore, the results relating to participation in organized leisure activities did not show an unconditional positive relationship with welfare of the type analysed in my study, although a basic idea in welfare theories is that leisure participation is associated with increased welfare (Sletten Citation2011; Barstad Citation2014). The finding implies some element of causality. Although cross-sectional survey data cannot be used to confirm causal mechanisms, I designed the study to expose expected theoretical patterns. Variables representing the school arena were more strongly associated with students’ positive assessments of community, compared to variables representing the leisure arena. This finding is in line with those of previous studies (including one of my own) for which the researchers concluded that subjective experiences of school were very important elements in young people’s emotional place relations (Sinkkonen Citation2012; Gulløy Citation2017). However, it is not particularly closely in line with ideas from Nordic welfare theories of individual resource accumulation in leisure arenas (Ringen Citation1976), strengthened fellowship and belonging (Allardt Citation1975), or more general societal integration through organized leisure activities (Øia & Fauske Citation2010). Instead, the findings point to the relevance of a social exclusion approach to welfare (Sletten Citation2011).

Community assessments, place identity, and belonging

Popular culture often refers to a time in the past when young people in marginalized positions expressed a strong sense of place identity, such as when rival groups of youths came into conflict over their territorial ambitions regarding different parts of industrial inner cities, as in the film West Side Story (Wise & Robbins Citation1961). In my view, such representations reflect economic and cultural conflicts over place, but also a sense of pride and belonging.

In a classic study of banlieues (suburbs) in Paris and ghettos in Chicago, Wacquant reflects on ‘spatial alienation and the dissolution of “place”’ (Wacquant Citation2008, 241), namely the loss of a humanized, culturally familiar and socially filtered locale with which marginalized urban populations identify, feel at home, and live in relative security. Wacquant’s explanations for the ‘dissolution of place’ focus on both the resigned state, deindustrialization and a lack of organized leisure opportunities for the young people from the marginalized areas in the two cities. There is a tremendous difference between the environments he studied and semi-urban locations in Norway, yet his point has some relevance with respect to my study. Students who reported subjective poverty had more negative community assessments and vice versa, and their participation in organized leisure activities was not associated with significantly higher values on the community assessment index. The first of the aforementioned two conclusions is interesting because it suggests a loss of shared meaning or shared emotions, and the second conclusion is interesting because the historically integrative power of leisure organizations from the Grenland region evidently failed to materialize.

In line with theories of individualization and globalization (Paulgaard Citation2015; Ruud Citation2018), loss of meaning can indicate a process of general local disengagement. The changed role of youths’ leisure activities in late modernity has important implications for their opportunities to build positive emotional place relations. More indoor life, fewer informal activities and institutionalization of childhood are well-documented trends that restructure everyday life for all young people (Øia Citation1998; Furlong Citation2013; Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson Citation2014), with social and psychological dimensions. In a phenomenological perspective, leisure activities have the potential to influence various aspects of emotional place relations such as community assessments, but also deeper emotions such as belonging and place attachment. One possible implication is that, as a source of childhood memories and belonging, place experiences fade.

However, my findings do not support a general conclusion of diminishing place relations, since school relations and community aspects such as proximity to friends and family played an important role in the students’ emotional place relations. Holloway & Pimlott-Wilson (Citation2014) found that class-based differences in access to enrichment activities fundamentally changed the landscapes of children’s play and informal learning environments, with implications for educational geographies. School is a crucial setting for peer socialization. However, social differences in school relations and school outcomes are severe, and for young people who experience both difficult school relations and a lack of organized leisure activities, the consequences can be grave and possibly lead to them experiencing increased social inequalities or social exclusion.

Paulgaard (Citation2016) found that place was more important than class and ethnicity in the social construction of identity among youths in certain parts of Northern Norway. Place identity was linked to the practical ways of life in the coastal communities of the region, and particularly boys often had a strong sense of belonging. Building on Bourdieu’s concept of habitus (Bourdieu Citation1989, 18), the latter finding saw local learning contexts as anchored in different practices, languages, and ways of life (Paulgaard Citation2016). Apart from the gender difference, it is difficult to find indications of a similar pattern in the Grenland region. The groups with the most positive community assessments in Grenland were boys, well-off students, and students who were very satisfied with their school (). Local learning contexts in Grenland can be described as semi-urban and/or conventional, yet with a certain disposition to industrial work in vocational education. If there is a distinct Grenland place identity, the poorest students in my study seemed to miss it.

Sletten (Citation2010) argues that poverty affects young people’s subjective experiences through intricate processes of stigma and shame. It seems likely that such processes take place in arenas for organized leisure activities. Also, stigma experiences may colour emotional place relations. Difficulties in overriding social divisions may bring about outsider experiences instead of access to enjoyment and social capital. Smette (Citation2015) describes how school community members mark insider and outsider statuses through symbolic actions that continuously establish borders.

Furthermore, the results of my study point to power processes in leisure. Leisure organizations may appear as arenas under majority rule, dominated by cultural and social homogeneity. Community can be a powerful channel for social exclusion (Latham et al. Citation2009). Read in this way, the results of my study are in line with those of previous studies of young people’s place constructions through relations of inequality (Vestby Citation2003; Fosso Citation2004; Paulgaard Citation2016; Ruud Citation2018). Negative assessments may represent considerations of being ‘out of place’. Through this lens, the survey responses may be seen as individual acts of either identification with the community in question or coming up against it, in line with what Silk (Citation1999) terms a discursive approach to community.

Gender and community assessments among youths

The reported increase in depressive symptoms among young people, especially girls, often points to processes of individualization and high performance demands (Hegna et al. Citation2017). The role of social arenas in such processes has been relatively underexplored, although depressive mood symptoms have been associated with inactivity in terms of organized leisure activities (Sletten Citation2010). Leisure approaches within social work and social pedagogy offer alternative interpretations. While gender differences in psychological distress in late modern societies tell a story of sensitive, feeble girls, the enabling potential in leisure may provide girls with a more immediate strengthening of their place relations compared with boys. Purported positive effects of participation in organized leisure activities, such as self-confidence, enhanced skills and social contact with peers, may be especially important for girls, as a break from the demands of self-representation.

Although many leisure activities have a strong educational aspect, in which skills acquisition plays an integral part, the education is pleasure-driven (at least, theoretically). Whether it represents another brick in the wall of a future career or real time out, leisure can be seen as an alternative way of being in the world. In line with this enabling view, girls’ experiences of leisure may lead to a strengthening of their place relations, perhaps more so than for boys, as girls in the age range 13–16 years generally adapt more easily than boys to educational or structured settings (Frønes Citation1993).

The findings from my analyses indicate that with regard to place relations boys’ are less sensitive to where they spend their leisure time and/or the matter of participation in itself compared with girls, which can be understood in at least two ways. First, boys’ emotional place relations are initially more positive and perhaps also more stable, meaning that how they feel and think about the places where they live is more or less unaffected by their leisure activities. Second, the latter can indicate that, compared with girls, boys initially have a stronger sense of place identity, regardless of their leisure participation, which is partly in line with Paulgaard’s conclusion about local ideologies of masculinity being linked to place attachment (Paulgaard Citation2016).

However, it is worth noting that my analyses were confined to young teenagers and, according to Frønes (Citation1993), at that age boys are less physically and psychologically mature compared with girls. For this reason, compared with boys, girls may have more strained relationships with their community, family and friends, and the welfare benefits of their participation in leisure organizations are more evident. In this interpretation, positive experiences from one social context may spill over to other contexts.

A certain gender pattern in leisure participation might have affected the results of my analyses, as organizations vary in terms of their functional, cultural and symbolic links to communities (Bæck Citation2004; Øia & Fauske Citation2010). In Norway, compared with girls, boys are typically more often involved in sports (Øia & Fauske Citation2010; Bakken et al. Citation2016), for which costs are generally high (e.g. fees, travel, camps, and equipment), which may indicate that the tags of poverty are more difficult to override for boys than for girls. However, sports tend to have a strong local base (Schrumpf Citation2006) and it is possible that participation in sports lead to more explicit place relations than do other types of organized leisure activities (Hixson Citation2013). These findings can be interpreted in a number of ways and it is difficult to draw conclusions about gender differences until future studies have clarified the role of gender and subjective school relations. There also remains the possibility that young people who are initially more positive in their assessments dominate organized leisure contexts. Similar patterns have been identified in studies of place attachment (Lewicka Citation2011) and social capital (Middleton et al. Citation2005).

Theoretical implications

From a welfare theory perspective, my findings support social exclusion approaches that highlight not only the meaning and significance of participation, but also dynamics of inclusion and exclusion in social relations (Sletten Citation2011). The subjective nature of community assessments is probably sensitive towards ‘in place’ and ‘out of place’ experiences, including those experienced at school.

The findings from my study also highlight the problem of seeing place relations as a straightforward derivations from everyday activity or being in place. In a welfare theory perspective, this is contrary to the theoretical expectation that participation in organized leisure activities generates individual welfare in terms of well-being, happiness, or experiences of belonging to the community. Moreover, it does not support phenomenological approaches to place, whereby a sense of place grows out of place experiences. Instead, gender, class and school relations are strongly associated with young people’s emotional place relations, possibly reflecting power relations that exist between different youth groups in their struggles over place (Holloway & Hubbard Citation2001).

Policy implications

In line with the welfare approach used in my study, the negative community assessments represent a welfare problem and the findings have implications for policies intended to strengthen young people’s emotional place relations and render them more positive. Leisure contexts need better strategies to counter the invisible ways in which social differences are played out among participants and leaders, and this has been recognized as crucial but also difficult in a recent evaluation of government policies in this field (Fløtten & Hansen Citation2018). Leisure organizations should strive to strengthen their local presence and activities in ways that contribute to participants having more positive place relations. School authorities need to acknowledge schools’ importance in developing young people’s emotional place relations. The findings presented in this article should not be interpreted as evidence that participation in organized leisure activities is irrelevant for youth policy, as they may strengthen other aspects of welfare, such as quality of life or the extent and quality of social networks.

Lastly, more consideration should be paid to housing and urban policies. Young people from vulnerable families increasingly depend on alternative social relations and are more sensitive to place as a welfare dimension in their lives than are young people from less vulnerable families (Brattbakk & Andersen Citation2017). Proximity is a key factor in local political processes and local welfare monitoring frameworks may reflect challenges facing the welfare of children and youths in a more direct and sensitive way compared with national systems. That would also be in line with what Coulton & Spilsbury (Citation2014) call a place-based understanding of child well-being.

Conclusions

The purpose of the study was to explore the role of organized leisure activities in young people’s emotional place relations. The results of the analyses showed that the association between participation in organized leisure activities and community assessments was conditional on gender and school satisfaction. For boys, there were no such indications of a general positive association, while for girls, the association was modest and vulnerable to model specifications. Girls were initially more negative in their community assessments compared with boys. However, when they participated in organized leisure activities, their assessments became more positive; for boys, this was not the case when subjective school relations were taken into account. The findings also showed that students who experienced socio-economic hardships provided more negative assessments of community compared with well-off students, even when they participated in organized leisure activities. The main conclusion is that gender, class and school relations are strongly associated with young teenagers’ emotional place relations. In a theoretical perspective, the findings point to social exclusion–inclusion dynamics instead of early Nordic welfare theory approaches to leisure participation.

Further research on associations between gender, socio-economic hardships, leisure, and emotional place relations is necessary. More sophisticated multilevel techniques than used in my study would also be of use, to differentiate between individual and municipality-level factors associated with emotional place relations.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the participants of NOVA’s surveys ‘Ung i Skien’ (2011) and ‘Ung i Porsgrunn’ (2012), and to NOVA for access to the survey data. Terje Wessel, University of Oslo, and Geir H Moshuus, University of South-Eastern Norway, are thanked for comments and support during the writing process. Shea Allison Sundstøl, University of South-Eastern Norway, is thanked for an earlier version of the map that now appears in . I am very grateful to Ulrike Bayr, Norwegian Institute of Bioeconomy Research (NIBIO), for producing .

ORCID

Elisabeth Gulløy http://orcid.org/0000-0003-1238-1675

Notes

1 NOVA was not responsible for any part of the analysis or conclusions reported in this article.

2 The questions in and hereafter in this article were translated from Norwegian by the author.

3 I considered transformation by the natural logarithm due to violation of assumptions of normality and homoscedasticity, but the original index yielded more intuitive results. I also checked whether similar results appeared in the median regression.

4 Although different transformations (logged and squared) were explored, the problem of non-normal distributions persisted.

5 The two response alternatives for poorer students were combined to increase the size of that subgroup.

References

- Allardt, E. 1975. Att Ha Att Älska Att vara. Lund: Argos förlag.

- Antonsich, M. 2010. Meanings of place and aspects of the self: An interdisciplinary and empirical account. GeoJournal 75(1), 119–132. doi: 10.1007/s10708-009-9290-9

- Bæck, U.-D. 2004. The urban ethos: Locality and youth in north Norway. Young 12(2), 99–115. doi: 10.1177/1103308804039634

- Bakken, A., Frøyland, L.R. & Sletten, M.A. 2016. Sosiale forskjeller i unges liv: Hva sier Ungdata-undersøkelsene? NOVA-rapport 3/16. Oslo: Velferdsforskningsinstituttet NOVA.

- Barne-, likestillings- og inkluderingsdepartementet. n.d. Barn som lever i fattigdom: Regjeringens strategi mot barnefattigdom 2015 - 2017. https://www.regjeringen.no/no/dokumenter/barn-som-lever-i-fattigdom/id2410107/ (accessed 26 February 2018).

- Barstad, A. 2014. Levekår og livskvalitet: Vitenskapen om hvordan vi har det. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Berg, N.G. 2016. Lokalsamfunn som sted - hvordan forstå tilknytning til bosted? Villa, M. & Haugen, M.S. (eds.) Lokalsamfunn, 34–52. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Blackshaw, T. 2013. Two sociologists: Pierre Bourdieu and Zygmunt Bauman. Blackshaw, T. (ed.) Handbook of Leisure Studies, 164–178. London: Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. 1989. Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory 7(1), 14–25. doi: 10.2307/202060

- Brattbakk, I. & Andersen, B. 2017. Oppvekststedets betydning for barn og unge: Nabolaget som ressurs og utfordring. AFI-rapport 2017:02. Oslo: Arbeidsforskningsinstituttet.

- Coleman, J.S. 1961. The Adolescent Society: The Social Life of the Teenager and its Impact on Education. New York: The Free Press.

- Coulton, C.J. & Spilsbury, J.C. 2014. Community and place-based understanding of child well-being. Ben-Arieh, A., Casas, F., Frønes, I. & Korbin, J.-E. (eds.) Handbook of Child Well-being: Theories, Methods and Policies in Global Perspective, 1307–1334. Dordrecht: Springer Link.

- Dallago, L., Perkins, D.D., Santinello, M., Boyce, W., Molcho, M. & Morgan, A. 2009. Adolescent place attachment, social capital, and perceived safety: A comparison of 13 countries. American Journal of Community Psychology 44(1–2), 148–160. doi: 10.1007/s10464-009-9250-z

- Epland, J. & Kirkeberg, M.I. 2017. Barn i lavinntektshusholdninger: Ett av ti barn tilhører en husholdning med vedvarende lavinntekt. http://www.ssb.no/inntekt-og-forbruk/artikler-og-publikasjoner/ett-av-ti-barn-tilhorer-en-husholdning-med-vedvarende-lavinntekt (accessed 1 April 2017).

- Fløtten, T. & Kavli, H. 2009. Barnefattigdom og sosial deltakelse. Fløtten, T. (ed.) Barnefattigdom, 92–118. Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk.

- Fløtten, T. & Hansen, I.L.S. 2018. Fra deltakelse til mestring: Evaluering av tilskuddsordningen mot barnefattigdom. FAFO-rapport 2018:04. Oslo: Fafo.

- Fosso, E.J. 2004. Unges flytting - et spørsmål om identitet og myter om marginale og sentrale steder? Berg, N.G., Dale, B., Lysgård, H.K. & Löfgren, A. (eds.) Mennesker, steder og regional endring, 119–135. Trondheim: Tapir Akademisk Forlag.

- Frønes, I. 1993. Blant likeverdige: Om sosialisering og jevnaldrendes betydning. Rapport 34/1993. Oslo: Insitutt for sosiologi, Universitetet i Oslo.

- Fuglestad, S., Grønning, E. & Storø, J. 2015. Aktivitetsfaget i barnevernspedagogutdanningen. Bjørknes, L.-E. (ed.) Sommerfugl, fly! En artikkelsamling av barnevernspedagoger 2015, 32–52. Oslo: Fellesorganisasjonen.

- Furlong, A. 2013. Youth Studies: An Introduction. New York: Routledge.

- Gjerustad, C. & Sletten, M.A. 2005. Nordiske surveyundersøkelser av barn og unges levekår 1970–2002. NOVA Skriftserie 7/05. Oslo: NOVA.

- Gregory, D., Johnston, R., Pratt, G., Watts, M.J. & Whatmore, S. 2009. The Dictionary of Human Geography. 5th ed. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Gullestad, M. 1997. A passion for boundaries: Reflections on connections between the everyday lives of children and discourses on the nation in contemporary Norway. Childhood 4(1), 19–42. doi: 10.1177/0907568297004001002

- Gulløy, E. 2017. Skole + tilhørighet = lokal tilhørighet? Bunting, M. & Moshuus, G.H. (eds.) Skolesamfunnet: Kompetansekrav og ungdomsfellesskap, 124–153. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Hagen, D. 2018. Søker om millioner for å bekjempe barnefattigdom. Telemarksavisa TA, 16 February, p. 7. https://www.ta.no/nyheter/skien/skien-kommune/soker-om-millioner-for-a-bekjempe-barnefattigdom/s/5-50-489229 (accessed 15 February 2020).

- Hegna, K., Eriksen, I.M., Sletten, M., Strandbu, Å. & Ødegård, G. 2017. Ungdom og psykisk helse - endringer og kontekstuelle forklaringer. Bunting, M. & Moshuus, G.H. (eds.) Skolesamfunnet: Kompetansekrav og ungdomsfellesskap, 75–94. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Hixson, E. 2013. Developing young people’s sense of self and place through sport. Annals of Leisure Research 16(1), 3–15. doi: 10.1080/11745398.2013.768156

- Holloway, L. & Hubbard, P. 2001. People and Place: The Extraordinary Geographies of Everyday Life. Harlow: Pearson Education.

- Holloway, S.L. & Pimlott-Wilson, H. 2014. Enriching children, institutionalizing childhood? Geographies of play, extracurricular activities, and parenting in England. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104(3), 613–627. doi: 10.1080/00045608.2013.846167

- Jenkins, R. 2014. Social Identity. 4th ed. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Kandel, D.B. & Davies, M. 1982. Epidemiology of depressive mood in adolescents: An empirical study. Archives of General Psychiatry 39(10), 1205–1212. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1982.04290100065011

- Kjelstadli, K. 2014. De tre samfunn: Arbeid, næringsliv og hverdagsliv etter 1905. Rovde, O. & Skobba, I. (eds.) Telemark historie 3: Etter 1905, 15–84. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Latham, A., McCormack, D., McNamara, K. & McNeill, D. 2009. Key Concepts in Urban Geography. London: SAGE.

- Lewicka, M. 2011. Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology 31(3), 207–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Mahoney, J.L., Larson, R.W. & Eccles J.S. 2005. Organized activities as developmental contexts for children and adolescents. Mahoney, J.L., Larson, R.W. & Eccles, J.S. (eds.) Organized Activities as Contexts of Development: Extracurricular Activities, After-school and Community Programs 3–22. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

- Manzo, L.C. 2014. Exploring the shadow side: Place attachment in the context of stigma, displacement, and social housing. Manzo, L.C. & Devine-Wright, P. (eds.) Place Attachment: Advances in Theory, Methods and Applications, 178–190. London: Routledge.

- Massey, D. 1994. Space, Place and Gender. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Middleton, A., Murie, A. & Groves, R. 2005. Social capital and neighbourhoods that work. Urban Studies 42(10), 1711–1738. doi: 10.1080/00420980500231589

- Næss, S. 2011. Språkbruk, definisjoner. Næss, S., Moum, T. & Eriksen, J. (eds.) Livskvalitet: Forskning om det gode liv, 15–51. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Øia, T. 1998. Oppvekst i Skien: Et forebyggende perspektiv. Oslo: NOVA.

- Øia, T. & Fauske, H. 2010. Oppvekst i Norge. 2nd ed. Oslo: Abstrakt forlag.

- Olsen, T., Hyggen, C., Tägtström, J. & Kolouh-Söderlund, L. 2016. Unge i risiko - overblik over situationen i Norden. Wulf-Andersen, T., Follesø, R. & Olsen, T. (eds.) Unge, udenforskab og social forandring: Nordiske perspektiver, 39–68. Frederiksberg: Frydenlund Academic.

- Olstad, F. 2014. Telemarkidrett. Rovde, O. & Skobba, I. (eds.) Telemarks historie 3: Etter 1905, 303–321. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Paulgaard, G. 2012. Geography of opportunity: Approaching adulthood at the margins of the northern European periphery. Bæck, U.D.K. & Paulgaard, G. (eds.) Rural Futures? Finding One’s Place within Changing Labour Markets, 189–215. Stamsund: Orkana akademisk.

- Paulgaard, G. 2015. Oppvekst i tid og rom: Om betydningen av sted i studiet av ungdom. Aure, M., Berg, N.G., Cruickshank, J. & Dale, B. (eds.) Med sans for sted: Nyere teorier, 117–132. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Paulgaard, G. 2016. Geographies of inequalities in an area of opportunities: Ambiguous experiences among young men in the Norwegian High North. Geographical Research 55(1) [2017], 38–46. doi: 10.1111/1745-5871.12198

- Ringen, S. 1976. Den sosiale forankring. Arbeidsnotat 82. http://www.nb.no/nbsok/nb/fdb8e780ee14f6635fffbe87a35c5a5b.nbdigital?lang=no#0 (accessed 14 December 2014).

- Ruud, M.E. 2015. Stedskonstruksjoner og stedstilknytning i boligområder under endring. Aure, M., Berg, N.G., Cruickshank, J. & Dale, B. (eds.) Med sans for sted: Nyere teorier, 179–193. Bergen: Fagbokforlaget.

- Ruud, M.E. 2018. Strategier for stedstilhørighet blant ungdom i byer og tettsteder i endring. Seim, S. & Sæter, O. (eds.) Barn og unge: By, sted og sosiomaterialitet, 39–57. Oslo: Cappelen Damm Akademisk.

- Schrumpf, E. 2006. Porsgrunns historie: Byen ved elva. Bind II. 1840–1920. Porsgrunn: Porsgrunn kommune.

- Sheerder, J. & Vandermeerschen, H. 2016. Playing an unequal game? Youth sport and social class. Green, K. & Smith, A. (eds.) Routledge Handbook of Youth Sport, 265–286. New York: Routledge.

- Silk, J. 1999. The dynamics of community, place, and identity. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 31(1), 5–17. doi: 10.1068/a310005

- Sinkkonen, M. 2012. Attachment of young people to their home district. Youth & Society 45(4) [2013], 523–544. doi:10.1177/0044118 × 11423014 doi: 10.1177/0044118X11423014

- Sletten, M.A. 2010. Social costs of poverty: Leisure time socializing and the subjective experience and social isolation among 13–16-year old Norwegians. Journal of Youth Studies 13(3), 291–315. doi: 10.1080/13676260903520894

- Sletten, M.A. 2011. Å ha, å delta, å være en av gjengen: Velferd og fattigdom i et ungdomsperspektiv. Oslo: NOVA.

- Smette, I. 2015. The Final Year: An Anthropological Study of Community in Two Secondary Schools in Oslo, Norway. PhD thesis. Oslo: University of Oslo.

- Statistics Norway. 2017. [Tabell] 05074: Brutto utbetalt økonomisk sosialhjelp, etter stønadens art (K) 1997–2016. https://www.ssb.no/statbank/table/05074/ (accessed 1 April 2017).