Introduction

Innovation is a driving force of productivity and economic growth. However, it is simultaneously part of a techno-scientific paradigm (Benissa & Funtowicz Citation2015) in which innovation-fuelled economic growth also leads to increased risk and environmental degradation (Beck Citation1992; Giddens Citation1999). Recent research, such as that by Coad et al. (Citation2021) and Biggi & Guiliani (Citation2021), highlight these ‘dark sides of innovation’. A review by Biggi & Guiliani (Citation2021) identifies five strands of extant research comprising varying aspects of the harmful implications of innovation: (1) work-related consequences of technology acceptance, (2) unsustainable transitions, (3) innovation and growth downside effects, (4) the risks of emerging technologies, and (5) open innovation’s dark side.

Concomitant to the identification of the five strands extant research is the emergence of standardisation in contemporary innovation studies, policies, and practices. The ‘directionality’ of innovations and the methods by which mission-oriented policies aim to deal with ‘grand challenges’, such as the climate crisis and sustainable and inclusive growth (Mazzucato Citation2018), are prioritised. For example, innovation policies and practices, and their evolution have been categorised into three frames or phases (Schot & Steinmueller Citation2018). The first phase (dominant in the 1960s–1980s) focused on research and development (R&D), regulations and market failures; innovation processes were considered linear. The second phase (dominant from the 1990s and up to the present) designated innovation systems as an interaction between private, public, and R&D contributions and system failures, resulting in a dynamic and interactive focus on innovation. The third and current phase concentrates on normative innovation processes and policies and how they can induce ‘transformative change’. Therefore, ‘responsible research and innovation’ (RRI) has become an important framework towards increased sustainability or responsibility in the governance of science (Owen et al. Citation2012; Stilgoe et al. Citation2013; Stilgoe & Guston Citationn.d.). RRI focuses on the methods by which processes and practices can improve the ethical, inclusive, and sustainable components of innovation through the emphasis on four factors: anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013).

Despite the relevance of the RRI framework, RRI has been criticised by several authors (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019, Uyarra et al. Citation2019, L. Coenen & Morgan Citation2020) for having a narrow definition in terms of science and research, microscales, and instrumentality, as well as lacking clarity in relation to both theory and practice (Owen et al. Citation2013). Therefore, it is unclear whether, as a concept, RRI constitutes an ideal, strategy, discourse or discipline (Koops Citation2015). Moreover, the contextual underpinnings of RRI should be clarified, since it has mainly been applied to analyse ‘obvious’ controversial innovations and technologies, such as those of biotechnological and gene modifications, which often have a strong ‘top-down’ focus. A sharper focus on context can determine how RRI develops (e.g. technologically, economically, culturally, sociopolitically) in different geographies, the influences of different locations on RRI processes and outcomes, and the effects of RRI on these areas (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019). This leads to a wider conceptualisation of innovation processes through the ‘responsible innovation’ (RI) initiative (e.g. how responsibility should be practised or performed in real-world settings) (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; Thapa et al. Citation2019; L. Coenen & Morgan Citation2020).

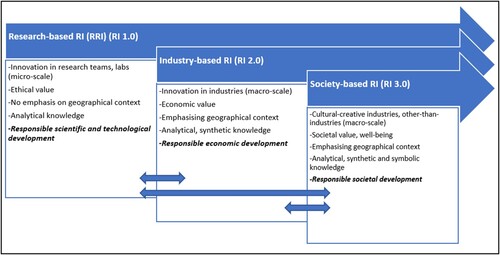

The aims of this extended editorial are to explore the various geographies of responsible innovation and identify pathways for RI that would allow for a richer understanding of the concept in order to educate policymakers regarding the development and implementation of more inclusive, creative, societally acceptable, and sustainable solutions. This discussion is intended to augment earlier conceptual work (such as that of Jakobsen et al. Citation2019), which describes the importance of a wider conceptualisation of RI. The presumption is that RI should not be viewed as an exclusively top-down approach with a narrow focus on research, but as a method that emphasises various innovations and processes, including those of bottom-up contributors (e.g. researchers, firms, public representatives, citizens). In addition, these processes can be influenced by a variety of contexts, such as ‘research and technological specificities, industry sector characteristics, spatial or regional conditions, institutional dimensions, policy regulations and socio-cultural dimensions’ (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019). We argue that the contextual dimension should be elaborated to include a stronger focus on contexts that are unrelated to industry or to industry contexts that are strongly associated with the production of social, cultural, and aesthetic values. Such contexts include innovation and innovation processes in the public sector, civil society and the cultural-creative sector, which involve innovations that are not necessarily or primarily focused on economic value creation. Generally, RRI has focused on the role of individuals and smaller networks, rather than on wider innovation systems and regional innovation processes and institutions (Thapa et al. Citation2019); therefore, the contribution of the latter should be addressed more thoroughly. Finally, we argue that the RI literature should specify how it incorporates the different forms of knowledge obtained by the various sources. This calls for a differentiated approach, since knowledge bases (Asheim et al. Citation2011) differ in importance with regard to science and research-driven innovation (drawing primarily on analytical knowledge), industry-driven innovation (drawing on analytical and synthetic knowledge), and societal innovation in ‘other-than-industry-contexts’, such as the public sector, civil society, and industries, in which social, cultural, and aesthetic values are equal in relevance to economic gains (drawing on analytical, synthetic, and symbolic knowledge). Thus, while Schot & Steinmueller (Citation2018) separate the three phases of innovation and innovation policy (linear, systemic, and normative), we ascertain contours of three phases within RI that correspond to the three framings presented by Schot & Steinmueller (Citation2018). These phases can be conceptualised as Responsible Innovation 1.0, Responsible Innovation 2.0, and Responsible Innovation 3.0, which are described in more detail in the following section.

The development of RI: from science to industry to society

Responsible Innovation 1.0

The original academic and policy-centred discussion relating to responsible research and innovation (RRI) (Von Schomberg Citation2011; Owen et al. Citation2012; Stilgoe et al. Citation2013), hereafter termed ‘Responsible Innovation 1.0’ (RI 1.0), refers to RRI as an academic concept that is heavily inspired by science and technology studies (STS) (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013). RRI was originally developed in association with science, technology, and innovation (STI) policy (Flink & Kaldewey Citation2018) and has since become prominent in EU policy circles and research councils in Europe in the last decade (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019). In general, RRI attempts to bridge the gap between science and society (de Hoop et al. Citation2016) and is defined as follows:

[a] transparent, interactive process by which societal actors and innovators become mutually responsive to each other with a view to the (ethical) acceptability, sustainability and societal desirability of the innovation process and its marketable products (in order to allow a proper embedding of scientific and technological advances in our society). (Von Schomberg Citation2011, 9)

RRI in science and research relies primarily on the production and use of analytical knowledge to generate scientific advances (Jensen et al. Citation2007). The nature of analytical knowledge allows it to traverse long distances, as opposed to that of tacit knowledge (Asheim et al. Citation2011). A focus on analytical knowledge has given rise to the science, technology, and innovation (STI) mode, in which innovation primarily unfolds in universities, research centres, and R&D departments within firms (Jensen et al. Citation2007). This allows for the successful investment and structuring/restructuring of scientifically skilled labour concomitantly with the advancement of specialised technologies and infrastructures relating to these microcontexts. Therefore, in terms of RRI, the STI mode of innovation could be conceived as narrow. Thus, a critical issue in relation to RRI is embedded in the missing connection and involvement of key stakeholders (e.g. in relation to the key dimensions of RRI, anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness (Stilgoe et al. Citation2013)). Moreover, RRI tends to concentrate on normative innovation processes and practices in more advanced industrial or technological contexts connected to the private sphere, as opposed to those within civil society, the public sector, and creative industries.

Responsible Innovation 2.0

While RRI has increased the awareness of innovation in terms of ethical, inclusive, and sustainable methods, it has been conceptualised as an ‘ideal, strategy, discourse and discipline’ (Koops Citation2015) and is therefore difficult to operationalise. In addition, RRI has an empirical focus on high-tech industries. The scientific literature on RRI is skewed towards controversial sectors and technologies, such as advances in biotechnology and gene technology, and the potential dark sides of IT technology (e.g. social media addiction, data management plans) Additionally, it has focused on ensuring R&D processes are responsible, while leaving actual innovation processes up to firms and industries (Fitjar et al. Citation2019).

Thus, we move beyond the above-discussed points and criticisms to observe how other types of industries engage with responsible innovation. A shift in the conceptualisation has been observed from RRI to RI (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; Owen & Pansera Citation2019; Daimer et al. Citation2021), which we term ‘Responsible Innovation 2.0’ (RI 2.0). This division is not new, but has to a large extent been ‘linked to the differentiation between RRI as a policy approach presented by the European Commission and Responsible Innovation (RI) as a broader concept discussed in the (mainly) academic literature’ (Daimer et al. Citation2021, 152). Moreover, Jakobsen et al. (Citation2019) state that these processes unfold differently in various technological, industrial, geographical, institutional, political, and sociocultural contexts. Thus, RI 2.0 ‘denotes an orientation toward anticipation, inclusiveness, responsiveness, and reflexivity concerning science and technology and innovation processes more broadly’ (van Oudheusden Citation2014, 68). As highlighted by van Oudheusden (Citation2014), RI 2.0 can be described in terms of its failure to incorporate anticipation, reflexivity, inclusion, and responsiveness, which leads to its inability to acknowledge societal needs and values. Therefore, van Oudheusden (Citation2014, 67) argue that RI (in this phase) is based on the following:

the idea that present modes of innovating with science and technology fail because they insufficiently take into account societal needs and values. Hence, proponents of RI solicit society’s opinions in an attempt to render science and technology developments, institutions, and policies more socially responsive.

Although RI 2.0 has widened the scope of what constitutes RI processes regarding actors, knowledge, and contexts, it may still focus on private sector-driven responsible economic growth and technological development with an emphasis on environmental and societal issues. However, both analytically and empirically, RI can be extended to contexts, other than those of industry, in which institutional logic and other understandings of value are prioritised.

Responsible Innovation 3.0

Recent contributions to the literature have, in addition to expanding their industrial focus within the private sector, reflected on RI in the public and the civil society sectors or its contribution to society, as opposed to economic value creation and competitiveness. For example, Albertson et al. (Citation2021) argue that the focus should be shifted from the contribution of RI to responsible transactional-based innovations to that of relational and ‘well-up’ innovations (well-being, low-/no-growth initiatives, redistribution, and social inclusion) rather than merely economic growth:

With over a decade of scholarship and policy making around responsible innovation, broadly understood […] the time is ripe to incorporate well-up and relational innovation alongside questions about who benefits from innovation and who is impacted, who is engaged and how. This will help align the values of care, stewardship, social welfare and sustainability with a vision of progress that promotes multiple forms of human and social affluence and that re-conceptualizes and re-organizes resource distribution to address the needs of the most marginalised groups. (Albertson et al. Citation2021, 297)

A hallmark of RI in the current phase (RI 3.0) is that conceptualisations of value and purpose (Mazzucato Citation2018) other than purely economic views should be included more explicitly in the literature and that there exist various actors operating according to different ‘institutional logics’ (Thornton et al. Citation2012) that contribute to shaping RI processes. RI has focused on sustainable and inclusive R&D processes and practices, and increasingly on sustainable and inclusive innovation processes and practices in industry. While the focus on ethical considerations is prevalent in these perspectives, the core ideals of RI in terms of anticipation, reflection, inclusion, and responsiveness have the potential to provide more concrete ‘models tools and guidelines’, which could aid in the implementation of, for example, transformative innovation policies (Haddad et al. Citation2022). However, social, cultural-creative innovations and other associated conceptualisations of value (social, cultural, environmental/ecological, and aesthetic) have been less pronounced within RI. Although this is increasingly recognised (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019), industrial rather than societal needs are the main concerns. As conceptualisations of value are embedded in various sociocultural normative and cognitive systems or institutions (Scott Citation1995) that are characterised by stability but are prone to change, RI in this phase can be subject to contextual variations, which can also be reflected in the geography of responsible innovation.

With regard to knowledge bases, RI 3.0 should include a wide range of participants (as suggested in the subsection ‘Responsible Innovation 2.0’), networks and forms of knowledge that emphasise societal values rather than merely profit and growth valuations. Thus, while the focus on analytical and synthetic knowledge remains important in RI 3.0, symbolic knowledge (Asheim & Hansen Citation2009; Asheim et al. Citation2011) must be included. Symbolic knowledge is defined as knowledge that is ‘applied in the creation of meaning and desire, as well as in the aesthetic attributes of products, producing designs, images, and symbols, and in the economic use of such forms of cultural artifacts’ (Asheim & Hansen Citation2009, 430). This type of knowledge should identify and specifically address the culture, aestheticism, and meaning embodied among those contributing to the temporary networks of knowledge exchange. While emphasising economic profitability, innovation processes realised through interactions between actors, new creative ideas, or knowledge do not necessarily occur with the objective of maximising economic profit (i.e. market-based innovation). Thus, concepts emerging from symbolic knowledge innovation processes can form a basis for innovations which in turn are based on conceptualisations of values other than those of economic growth, such as social, environmental, cultural, or aesthetical values. Finally, symbolic knowledge can aid in the creation and legitimisation of new societal values or attitudes (Meusburger Citation2005). Therefore, RI 3.0 has an expanded scope that includes relevant and knowledgeable actors associated with societal and cultural valuations, as opposed to ‘consultants’ for innovation processes related to responsible science, research, and industry.

Refining the conceptualisation of contextually embedded responsible innovation: research-based RI, industry-based RI, and society-based RI

Based on the discussion in the preceding subsections, the outlines of the three ‘phases’ of RI research appear (). We argue that the development and division of these three phases allow for further disentangling and understanding of RI. Moreover, it creates a more in-depth understanding of the strengths and shortcomings of RI than that of past discussions. This exercise provides a ‘common ground’ of knowledge and identifies possible avenues for future research. In addition, the description of the three phases can be used to improve the inadequacies of RI (and RRI) in terms of the lack of clarity and understanding of the concept, ideal, strategy, discourse, or discipline of RI (Koops Citation2015), to allow for a strengthened understanding of these factors in various contexts. Based on the gradual evolution of the RI concept, we propose a conceptual framework that divides RI into three phases: Research-based RI (RRI) (RI 1.0), Industry-based RI (RI 2.0), and Society-based RI (RI 3.0). Each of these phases emphasises different aspects of the understanding of RI, how it unfolds (and should unfold), and who are (and should be) the most important actors in RI processes. It also re-emphasises the importance of context in terms of technology, industry, geography, institutions, policy, and sociocultural aspects (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; L. Coenen & Morgan Citation2020).

In highlighting the three ‘phases’, we can observe that they are not completely separate. They must be understood as interwoven and not as distinctly independent phases that follow one after the other. Moreover, none of the phases carries more ‘normative weight’ than the others. Therefore, phase RI 3.0 is not an end or ideal towards which to strive, but a result of the addition of nuances to the current RI literature through an emphasis on innovations or innovation processes that are more strongly embedded in the social sphere, rather than the industrial or scientific sphere. RI 3.0 emphasises responsible innovation or innovation processes from other-than-industry sectors or industry contexts in which social, cultural, and aesthetic values are equal in importance to the production of economic value (i.e. the public sector, civil society, and the cultural-creative/arts sector).

To integrate the three phases, analysis of actual RI processes in real-world settings should not include allocating RI to one phase over another. RI processes that emphasise societal value or seek to solve societal challenges are not necessarily distinct from research-based and industry-based RIs, as they can incorporate knowledge, technologies, and actors associated with these phases. Moreover, different actors embedded in or working with RI can simultaneously adhere to different ‘institutional logics’ (Thornton et al. Citation2012). Therefore, society-based RI can incorporate values, knowledge, and technology related to economic value, as well as societal and aesthetic values. Thus, while the three phases are treated as ‘distinct’ in our framework, we acknowledge that certain elements within the phases overlap. For example, embedding science, research, and technology processes more strongly into society was the initial motivation to develop the RRI perspective (Von Schomberg Citation2011). Thus, in our conceptual model, RI is the outcome of dynamically interacting processes that in various ways combine research-based, industry-based, and society-based values, knowledge, and technologies. This dynamic interaction is additionally affected by context (technological, industrial, geographical, institutional, political, and sociocultural).

Integration of the special issue papers to our conceptual model

The papers in this special issue of Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography (Nagarajah Citation2022; K. Coenen Citation2023; Eriksen & Frivold Citation2023; Hopp et al. Citation2023) cover a wide array of topics relating to the exploration of the ‘geographies of responsible innovation’. In this section, we first present these contributions and then weave or reimagine them into our conceptual framework. The articles are presented in accordance with the different RI phases outlined above, and all contributions are associated with the different phases of our conceptual framework or with various combinations of them.

Joaquin Zenteno Hopp, Matthew Coffay and Emil Tomson Lindfors discuss responsible innovation with a focus on gene modifications in the Norwegian and Chilean salmon industry They address the different positions of the two countries on genetically modified soy as feed and describe that both can be understood as expressions of responsible innovation that result in differentiated, but responsible, directionalities. The authors primarily explore RI as a scientific ethics problem (thus placing themselves within the RI 1.0 phase) through analysis of the notion of responsibility and how it is formed independently of its connection to innovation. However, this approach differs from earlier work that mainly treats responsible innovation as a subfield of innovation. Therefore, Hopp et al.’s article provides a new way of framing RI and allows for critical reflection on the ethical assumptions regarding the factors that create specific directionalities for RI. Moreover, it consider the methods by which these ethical assumptions serve as a basis for creating and diffusing a specific type of knowledge. These aspects are then discussed in terms of differing notions towards genetically modified soy in the Norwegian and Chilean salmon farming industries, indicating differences in responsibilities for the same technology, which were created through STI. They also include a wider notion of the geographical context in science-based innovation in industries, which is introduced in the RI 2.0 framing.

Maren Songe Eriksen and Maria Tønnessen Frivold discuss regional industrial development towards greening in two historically fossil-dependent, but structurally differentiated, regions in Norway (Stavanger and Grenland) by applying perspectives on regional asset use, modification, and agency. The authors identify barriers to the development of green paths and suggest that the creation, reuse, and recombination of both material and immaterial assets at the firm level and regional level might enable green path development in the regions under study. Eriksen & Frivold examine resilient regions through the lens of agency and assets, and they highlight their cases through a focus on the components of geography and RI. Their approach is aligned with an industry-driven RI (RI 2.0) and a focus on the DUI mode of innovation. Although they do not specifically engage with RI literature, they identify the need for a change in regional and industrial directionality to ensure responsible innovation trajectories. Additionally, they draw attention to preserving workplaces and ensuring responsible transitions to these processes.

Nanthini Nagarajah combines theoretical perspectives on sustainability transitions with RI and challenged the Western-centric view upheld in many previous studies. Specifically, Nagarajah studies sustainable energy transitions in Sri Lanka and suggests that a greater emphasis on contextual sensitivity is required regarding RI processes in developing countries. Furthermore, she determines that different contextual narratives in Sri Lanka should be aligned with technological innovation processes in order for sustainable energy transitions to be successful. While recent contributions have focused on the contexts of responsible innovation, such as the practicality of responsibility in real-world settings (Jakobsen et al. Citation2019; Thapa et al. Citation2019; L. Coenen & Morgan Citation2020), it is important to understand RI also in non-Western geographical settings. RI has primarily centred on analyses in the Global North, and therefore comparative evaluations are required for RI in the Global South (Macnaghten et al. Citation2014; Hartley et al. Citation2019; Wakunuma et al. Citation2021). The Global South faces considerably different societal challenges than those in the Global North. Nagarajah aims to address some of the issues raised through a focus on the problems with the Western-centric view that has been prominent in extant work. The article therefore can be placed in the RI 2.0 category, although Nagarajah expands on the notion of context by identifying the Global South as a ‘meta context’ that exhibits different dynamics relating to RI in industry contexts than those in the Global North.

Finally, Karin Coenen discusses how creativity and geography should be increasingly integrated into studies of responsible innovation, and how artists’ initiatives can contribute to sustainable regional development in rural areas. Focusing on artist-led social innovation initiatives in rural Sweden (Bromölla) and Norway (Rjukan), she finds that this type of innovation can empower local actors and that social innovation processes can present alternative development visions and practices that can enable socially and environmentally sustainable development in rural areas. Specifically, Coenen (Citation2023, 49) describes how ‘art, art-based methods, and aesthetics serve as a powerful means to expand future imaginaries and develop new scenarios of transformative change. This indicates a stronger emphasis on symbolic knowledge, in which cultural meaning is produced, mediated, or appropriated through social innovation processes. These processes can lead to new sustainable or social innovations, as well as economically profitable innovations. In addition, they can initiate new perspectives to observe and solve problems through ‘artistic and creative imaginaries’, which do not necessarily lend themselves to economic tasks or actors. Therefore, Coenen has an approach that is similar to the RI 3.0 phase, which involves solving societal problems ‘bottom-up’ through artistic and aesthetic framings.

Conclusions

The aim of this extended editorial has been to discuss how different phases or framings of RI have developed, using the parallel phases of innovation and innovation policy described by Schot & Steinmueller (Citation2018). Thus, the further goal has been to identify pathways for RI that will allow for a richer understanding of the concepts involved. From both this and the work of previous authors (e.g. Jakobsen et al. Citation2019, Thapa et al. Citation2019; L. Coenen & Morgan Citation2020), we have drawn attention to various contextual conditions – ‘geographies of RI’ – and how they impact real-life responsible innovations and innovation processes.

First, we have discussed the concepts of RRI and RI, and more specifically how the engagement with responsible innovations and innovation processes has gradually shifted from a narrow, research-oriented understanding to that of a wider scope that includes a variety of actors, knowledge, and contexts. Second, we have introduced a novel conceptual framework that allows for a greater ‘societal conceptualisation’ of RI. In this framework, we highlight the distinctive features of each phase and emphasise that these phases overlap and intertwine. Third, and finally, we have introduced the research contributions of this special issue of Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography (Nagarajah Citation2022; K. Coenen Citation2023; Eriksen & Frivold Citation2023; Hopp et al. Citation2023), which address different RI phases and different geographies that are highlighted through our conceptual framework.

Although the contributions in this special issue on the geographies of responsible innovation address and highlight previously underexplored issues, they also indicate new pathways to pursue. Further disentangling of the mechanisms introduced in this special issue will include the extension of RI research to such areas as inclusion and diversity in workplaces (Solheim Citation2022) and inclusive innovation in cities (Lee Citation2023). Moreover, RI must be considered in terms of challenges connected to increasing regional divides (Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018) and economic, social, and political polarisation (Pike et al. Citation2007; Lee & Rodríguez-Pose Citation2016; Moss & Solheim Citation2022). This includes investigating the identification and inclusion or exclusion of stakeholders in RI processes (and outcomes) based on pre-existing power relations or structures when creating responsible, sustainable solutions and the contextual factors potentially affecting this association.

References

- Albertson, K., de Saille, S., Pandey, P., Amanatidou, E., Arthur, K.N.A., van Oudheusden, M. & Medvecky, F. 2021. An RRI for the present moment: Relational and ‘well-up’ innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation 8(2), 292–299.

- Asheim, B. & Hansen, H.K. 2009. Knowledge bases, talents, and contexts: On the usefulness of the creative class approach in Sweden. Economic Geography 85(4), 425–442.

- Asheim, B.T., Boschma, R. & Cooke, P. 2011. Constructing regional advantage: Platform policies based on related variety and differentiated knowledge bases. Regional Studies 45(7), 893–904.

- Beck, U. 1992. Risk Society: Towards a New Modernity. New Dehli: SAGE.

- Benessia, A. & Funtowicz, S. 2015. Sustainability and techno-science: What do we want to sustain and for whom? International Journal of Sustainable Development 18, 329–348.

- Biggi, G. & Giuliani, E. 2021. The noxious consequences of innovation: What do we know? Industry and Innovation 28(1), 19–41

- Bulkeley, H., Marvin, S., Palgan, Y.V., McCormick, K., Breitfuss-Loidl, M., Mai, L., von Wirth, T. & Frantzeskaki, N. 2019. Urban living laboratories: Conducting the experimental city? European Urban and Regional Studies 26(4), 317–335.

- Coad, A., Nightingale, P., Stilgoe, J. & Vezzani, A. 2021. The dark side of innovation. Industry and Innovation 28(1), 102–112.

- Coenen, L. & Morgan, K. 2020. Evolving geographies of innovation: Existing paradigms, critiques and possible alternatives. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 74(1), 13–24.

- Coenen, K. 2023. Creatively transforming periphery? Artists’ initiatives, social innovation, and responsibility for place. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 77(1), 47–61.

- Daimer, S., Havas, A., Cuhls, K., Yorulmaz, M. & Vrgovic, P. 2021. Multiple futures for society, research, and innovation in the European Union: Jumping to 2038. Journal of Responsible Innovation 8(2), 148–174.

- de Hoop, E., Pols, A. & Romijn, H. 2016. Limits to responsible innovation. Journal of Responsible Innovation 3(2), 110–134.

- Eriksen, M.S. & Frivold, M.T. 2023. Barriers to regional industrial development: An analysis of two specialised industrial regions in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 77(1), 21–34.

- Fastenrath, S. & Coenen, L. 2021. Future-proof cities through governance experiments? Insights from the resilient Melbourne strategy (RMS). Regional Studies 55(1), 138–149.

- Fitjar, R.D., Benneworth, P. & Asheim, B.T. 2019. Towards regional responsible research and innovation? Integrating RRI and RIS3 in European innovation policy. Science and Public Policy 46(5), 772–783.

- Flink, T. & Kaldewey, D. 2018. The new production of legitimacy: STI policy discourses beyond the contract metaphor. Research Policy 47, 14–22.

- Giddens, A. 1999. Runaway World. London: Profile Books.

- Haddad, C.R., Nakić, V., Bergek, A. & Hellsmark, H. 2022. Transformative innovation policy: A systematic review. Environmental Innovation and Societal Transitions 43, 14–40.

- Hansen, T. 2022. The foundational economy and regional development. Regional Studies 56(6), 1033–1042.

- Hartley, S., McLeod, C., Clifford, M., Jewitt, S. & Ray, C. 2019. A retrospective analysis of responsible innovation for low-technology innovation in the Global South. Journal of Responsible Innovation 6(2), 143–162.

- Hopp, J.Z., Coffay, M. & Lindfors, E.T. 2023. Inclusion in the global innovation system for CRISPR salmon in Norway. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 77(1), 10–20.

- Jakobsen, S.-E., Fløysand, A. & Overton, J. 2019. Expanding the field of responsible research and innovation (RRI) – from responsible research to responsible innovation. European Planning Studies 27(12), 2329–2343.

- Jensen, M.B., Johnson, B., Lorenz, E. & Lundvall, B.Å. 2007. Forms of knowledge and modes of innovation. Research Policy 36(5), 680–693.

- Koops, B.-J. 2015. The concepts, approaches, and applications of responsible innovation: An introduction. Koops, B.-J., Oosterlaken, I., Romijn, H., Swierstra, T., & van den Hoven, J. (eds.) Responsible Innovation 2: Concepts, Approaches, and Applications, 1–15. Cham: Springer.

- Lee, N. 2023. Inclusive innovation in cities: From buzzword to policy. Regional Studies. DOI: 10.1080/00343404.2023.2168637

- Lee, N. & Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2016. Is there trickle-down from tech? Poverty, employment, and the high-technology multiplier in US cities. Annals of the American Association of Geographers 106(5), 1114–1134.

- Macnaghten, P., Owen, R., Stilgoe, J., Wynne, B., Azevedo, A., de Campos, A. … Velho, L. 2014. Responsible innovation across borders: Tensions, paradoxes and possibilities, Journal of Responsible Innovation 1(2), 191–199.

- Mazzucato, M. 2018. Mission-oriented innovation policies: Challenges and opportunities, Industrial and Corporate Change 27(5), 803–815.

- Meusburger, P. 2005. Sachwissen und Orientierungswissen als Machtinstrument und Konfliktfeld. Zur Bedeutung von Worten, Bildern und Orten bei der Manipulation des Wissens. Geographische Zeitschrift 93(3), 148–164. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27819050 (accessed 14 April 2023).

- Moss, S.M. & Solheim, M.C.W. 2022. Shifting diversity discourses and new feeling rules? The case of Brexit. Human Arenas 5, 488–508

- Nagarajah, N. 2022. Determinants of responsible innovation for sustainability transition in a developing country: Contested narratives for transition in the Sri Lankan power sector. Norsk Geografisk Tidsskrift–Norwegian Journal of Geography 77(1), 35–46.

- Owen, R. & Pansera, M. 2019. Responsible innovation and responsible research and innovation. Simon, D., Kuhlmann, S., Stamm, J. & Canzler, W. (eds.) Handbook on Science on Science and Public Policy, 26–48. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- Owen, R., Macnaghten, P. & Stilgoe, J. 2012. Responsible research and innovation: From science in society to science for society, with society. Science and Public Policy 39, 751–760.

- Owen, R., Stilgoe, J., Macnaghten, P., Gorman, M., Fisher, E. & Guston, D. 2013. A framework for responsible innovation. Owen, R., Bessant, J. & Heintz, M. (eds.) Responsible Innovation, 27–50. https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.10029781118551424.fmatter (accessed 14 April 2023).

- Pike, A., Rodríguez-Pose, A., and Tomaney, J. (2007) What kind of local and regional development and for whom? Regional Studies 41(9), 1253–1269.

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. The revenge of the places that don't matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 11(1), 189–209.

- RRI Tools. n.d. Entering into RRI. https://www.rri-tools.eu/about-rri (accessed 10 April 2023).

- Schot, J. & Steinmueller, W.E. 2018. Three frames for innovation policy: R&D, systems of innovation and transformative change. Research Policy 47(9), 1554–1567.

- Scott, W.R. 1995. Institutions and Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Smith, A., Fressoli, M. & Thomas, H. 2014. Grassroots innovation movements: Challenges and contributions. Journal of Cleaner Production 63, 114–124.

- Solheim, M.C.W. 2017. Innovation, Space, and Diversity. PhD thesis. PhD thesis UiS, no. 327. Stavanger: University of Stavanger.

- Solheim, M.C.W. 2022. Making a thousand diverse flowers bloom: Driving innovation through inclusion of diversity in organisations. Callegari, B., Misganaw, B.A. & Sardo, S. (eds.) Rethinking the Social in Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 174–189. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781839108174.00018

- Stilgoe, J. & Guston, D.H. n.d. Responsible research and innovation. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10052401/1/Stilgoe_Guston_responsible_innovation_2017.pdf (accessed 10 April 2023).

- Stilgoe, J., Owen, R. & Macnaghten, P. 2013. Developing a framework for responsible innovation. Research Policy 42, 1568–1580

- Thapa, R.K., Iakovleva, T. & Foss, L. 2019. Responsible research and innovation: A systematic review of the literature and its applications to regional studies. European Planning Studies 27(12), 2470–2490.

- Thornton, P.H., Ocasio, W. & Lounsbury, M. 2012. The Institutional Logics Perspective. A New Approach to Culture, Structure, and Process. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Uyarra, E., Ribeiro, B. & Dale-Clough, L. 2019. Exploring the normative turn in regional innovation policy: Responsibility and the quest for public value. European Planning Studies 27(12), 2359–2375.

- van Oudheusden, M. 2014. Where are the politics in responsible innovation? European governance, technology assessments, and beyond. Journal of Responsible Innovation 1(1), 67–86.

- Von Schomberg, R. 2011. Towards responsible research and innovation in the information and communication technologies and security technologies fields. SSRN. https://ssrn.com/abstract=2436399 (accessed 10 April 2023).

- Wakunuma, K., de Castro, F., Jiya, T., Inigo, E.A., Blok, V. & Bryce, V. 2021. Reconceptualising responsible research and innovation from a Global South perspective. Journal of Responsible Innovation 8(2), 267–291.