ABSTRACT

Social functioning and reading proficiency are critical for success in school and society. Therefore, identifying children with such problems is important. This study had 2 parts: first, a random sample of 234 elementary schools was surveyed about which instruments they use to assess reading proficiency and social functioning. Second, a systematic review of the quality of these instruments was conducted using international standards for examining the quality of assessment instruments. The survey showed that schools more often assessed and had more instruments available for reading than for social functioning. The systematic review of the assessment instruments used revealed that the psychometric qualities of many was weak or undocumented, while the dimensions of test material quality were generally good. The findings demonstrate a need for a more thorough examination of the psychometric properties of assessment instruments to be used in school.

Everyday decisions that impact children’s social and academic development are based on information derived from a variety of educational assessments conducted in schools. Such decisions can influence children’s curricula and whether a child receives additional support to prevent and ameliorate difficulties or receives a referral to educational psychology services for further diagnostics and special education. Thus, assessments are important for instructional decisions that may have a great impact on children’s learning and wellbeing.

It is reported that 15–20% of Norwegian children in Grades 1 to 10 are facing social emotional (i.e., anxiety, conduct disorders, depression) and/or academic (i.e., reading, math) difficulties that impact their academic success (Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education], Citation2009, Citation2017). Moreover, 20% of children have a special requirement for more intensive support than their peers to succeed socially and/or academically (Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education], Citation2017). Because social functioning and reading proficiency are strongly related to future life outcomes for students at risk, promoting such skills is crucial (Durlak, Weissberg, Dymnicki, Taylor, & Schellinger, Citation2011; Gustafsson et al., Citation2010; OECD, Citation2015).

Compared with the USA and the UK, Norway began using systematic assessments in schools relatively recently. Additionally, Norway, like many other European countries, faces a disadvantage in regard to the development of educational assessment instruments because it has a small population that uses its own language. However, as noted above, schools make many important decisions – based on the assessment instruments they use – that may affect children’s lives. Additionally, to prevent difficulties in children’s social functioning and/or reading, difficulties should be identified early and targeted interventions should be implemented (Elliott, Huai, & Roach, Citation2007). When such an approach is followed, less intensive support is needed (Merrell, Citation2001).

Assessing and identifying at-risk students at an early stage requires that teachers have access to assessment instruments which not only are easy to use and quick to administer but of high quality. To examine this important issue, we present a study in which the aim was twofold. First, we examined, by survey, a random sample of Norwegian elementary schools to determine what instruments they actually use to assess children’s social functioning and reading proficiency. Second, we evaluated the quality of the assessment instruments that the schools reported using.

Social Functioning, Reading Proficiency and Their Relationship

Social functioning in a school setting is often defined as how children behave and interact with others, relying on their social skills (Beauchamp & Anderson, Citation2010). A number of studies show that social skills are required for the development of good social relations, emotional and academic engagement, and school motivation (Beauchamp & Anderson, Citation2010; Cordier et al., Citation2015; Gresham, Citation2007). Reading proficiency refers to the process of learning to decode words accurately and fluently and to comprehend the meaning of text (Hoover & Gough, Citation1990). Being a proficient reader and being able to extract meaning from text is crucial for academic achievement in most theoretical school subjects (García-Madruga, Vila, Gómez-Veiga, Duque, & Elosúa, Citation2014; National Assessment Governing Board, Citation2013). Thus, together, social functioning and reading proficiency are important for a child’s wellbeing and academic performance (McIntosh, Reinke, Kelm, & Sadler, Citation2012; OECD, Citation2015). Mastering the skills of social functioning and reading will not only allow children to develop social and academic competence in school (Durlak & Weissberg, Citation2011; Stewart, Benner, Martella, & Marchand-Martella, Citation2007), but also prepare them for successful participation in society and the workplace (Heckman, Citation2000, Citation2011; NOU, Citation2015:Citation8).

Research has also demonstrated that reading skills and social skills are highly related (Algozzine, Wang, & Violette, Citation2011; DeRosier & Lloyd, Citation2011). For instance, a study of children from low-income homes showed that relatively poor literacy achievement in Grade 1 was significantly correlated with relatively high aggressive behaviour in Grade 3 (r = −.32; p < .01) and Grade 5 (r = −.28; p < .01) (Miles & Stipek, Citation2006). The study also demonstrated that prosocial behaviour in Grade 1 was significantly correlated with literacy achievement in Grades 3 and 5 (r = .24; p < .05). Furthermore, the results from a longitudinal study indicated that children’s academic achievement directly influenced their social functioning from Grades 1 to 2 and from Grades 2 to 3 and that children’s social functioning was reciprocally related to academic achievement from Grades 2 to 3 (Welsh, Parke, Widaman, & O’Neill, Citation2001). Early difficulties in language and reading are risk factors for later social behavioural disorders (Stewart et al., Citation2007).

The co-occurrence of social behavioural disorders and reading difficulties (i.e., dyslexia, poor reading comprehension) has been documented in several studies (see, e.g., Boada, Willcutt, & Pennington, Citation2012; Dahle, Knivsberg, & Andreassen, Citation2011; Terras, Thompson, & Minnis, Citation2009; Undheim, Wichstrøm, & Sund, Citation2011). In a study of children’s social and literacy abilities in Grades 2–5, teachers reported concerns about more than 50% of the children who were struggling in one or both of these domains (Arnesen, Meek-Hansen, Ottem, & Frost, Citation2013). Thus, children who struggle in one of these domains are more likely to struggle in the other domain (Elliott et al., Citation2007; Rivera, Al-Otaiba, & Koorland, Citation2006). In summary, the literature supports the importance of the early identification of children who are struggling in one or both of these two domains to promote positive development.

Methods of Assessing Social Functioning and Reading Proficiency

Differences in the constructs of social functioning and reading proficiency require different approaches in terms of assessment methods. Whereas measures of social functioning are commonly based on informal teachers’ ratings and students’ self-reports, reading proficiency is measured based on summative formal tests or formative informal assessments and teacher ratings. Findings from systematic reviews show large variations in the methods that schools use to assess children’s development in social skills and reading (Cordier et al., Citation2015; Floyd et al., Citation2015; Gotch & French, Citation2014; OECD, Citation2015; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment], Citation2014; Standards & Testing Agency, Citation2015). Altogether, these reviews show that the educational assessment instruments used in schools vary with respect to a number of dimensions: (1) the level of informal or formal structure (e.g., open notes of teacher ratings versus criterion-based tests); (2) the level of interactivity (e.g., static versus dynamic); (3) whether the assessment is summative or formative (e.g., assessment of learning versus assessment for learning); (4) the assessment structure (e.g., presentation of the items to the test-taker); (5) the response formats (e.g., selected or constructed items); and (6) the item scoring (e.g., hand scoring versus computer-based scoring). Furthermore, the instruments also varied regarding the purpose of the educational assessment, as different types are used for screening, monitoring progress, and diagnosis.

Quality of Educational Assessment Instruments

In the wake of Cronbach and Meehl’s (Citation1955) seminal paper on the validity of psychological assessment instruments, researchers have developed a number of systems and criteria for judging the validity of a measurement. Some criteria seem to be agreed upon and are considered critical to the quality of an instrument, independent of whether the assessment’s purpose is summative or formative.

Validity refers to whether an instrument’s scores have systematic measurement error. There are different types of validity, but those most commonly used in evaluations of educational assessment instruments (see, e.g., Evers, Hagemeister, & Hostmaelingen, Citation2013; Evers, Muñiz et al., Citation2013) are construct validity (whether the items represent the theoretical constructs that they are designed for), criterion-related validity relating to concurrent and predictive validity (whether the assessment instruments correlate with other relevant valid instruments used for the same purpose to predict future or current performance), and content validity in terms of face validity and logical validity (whether the items are representative and are an accurate assessment covering the broad range of variation within children’s social skills and reading skills). Note that criterion validity also concerns how cut-off points (specificity and sensitivity) and norms are developed as well as how the norming sample represents the population the instrument is designed to assess in regard to age, socioeconomic background, gender, language background, and other important characteristics (Thorndike & Thorndike-Christ, Citation2014).

Furthermore, reliability refers to the extent to which an instrument produces random measurement errors. Reliability is crucial if an assessment is to be useful, as a test that is not reliable can never be a valid instrument (Thorndike & Thorndike-Christ, Citation2014). Reliability is commonly assessed in terms of internal consistency reliability (the degree to which different test items that probe the same construct produce similar results), test–retest reliability (stability over time), and inter-rater reliability (the degree to which different observers or raters agree).

Recent systematic reviews evaluating the quality of educational assessment instruments have revealed a lack of studies of psychometric properties for many of the instruments used in schools (see, for instance, Cordier et al., Citation2015; Floyd et al., Citation2015; Gotch & French, Citation2014; Siddiq, Hatlevik, Olsen, Throndsen, & Scherer, Citation2016; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment], Citation2014). Although several of the reviewed measures demonstrated good psychometric qualities, many others showed weak or lacking evidence. In a review of 13 measures of social skills, Cordier et al. (Citation2015) found excellent reliability scores overall, but none of the measures were found to exhibit validity. Additionally, Floyd et al. (Citation2015) demonstrated that most of the 14 behaviour scales they reviewed had adequate or inadequate norming data. These scales were associated with a mix of adequate, inadequate or not-reported reliability, as well as inadequate overall validity. Furthermore, Gotch and French (Citation2014) found weak psychometric evidence for the 36 educational literacy measures they reviewed. Siddiq et al. (Citation2016) reviewed 38 educational assessment instruments that aim to measure students’ literacy in information and communication technology; they found that the documentation and reporting of test quality were lacking overall. In Norway, however, there has been (to our knowledge) only one previous systematic review of educational assessments. It reviewed the quality of eight language assessment instruments used in kindergarten and found that none met the required criteria (Kunnskapsdepartmentet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education], Citation2011b). Moreover, a Swedish review of assessments of reading and literacy measures found that evidence was lacking overall in more than 50 of the reviewed tests (Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment], Citation2014).

Given the above-mentioned reviews, we might expect similar findings in the educational assessments of social functioning and reading used in Norwegian schools. Therefore, the current study is important to document the needs to improve the quality of assessments instruments in Norwegian schools, so that decisions regarding instruction based on such instruments can have a valid foundation.

The Current Study

Social functioning and reading proficiency provide the foundation for both academic performance and social wellbeing. To have valid instruments in schools to identify children who are struggling in one or both of these domains is vital for the development of instruction Despite ongoing discussions of educational policy, principles, and practice with regard to the assessment of children’s learning in Norwegian schools (Kunnskapsdepartmentet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education], Citation2011b, Citation2017), there are no systematic studies of the quality and use of educational assessment instruments for social functioning and reading proficiency. Therefore, we investigated the following research questions:

To what extent do Norwegian elementary schools use educational assessment instruments targeting children’s social functioning and reading proficiency and to what extent do schools use these to lead instructions and interventions?

What is the quality of the educational assessment instruments used to measure children’s social functioning and reading proficiency in Norwegian elementary schools in terms of descriptions and documented psychometric properties?

Methods

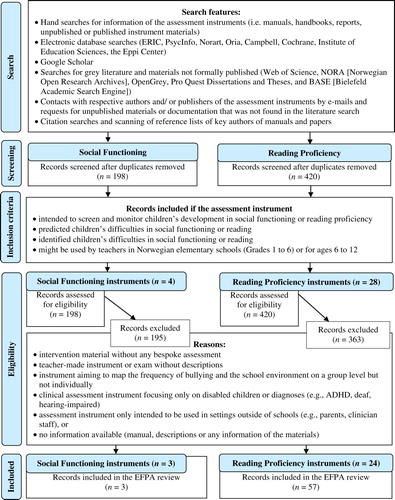

The current study has two parts: First, a survey was conducted in a random sample of approximately 15% of Norwegian elementary schools to provide an overview of all current assessment instruments that are used and the extent to which they are used to make decisions about interventions. Second, based on the survey, we conducted a systematic review of literature documenting the quality of the assessment instruments (i.e., validity studies published either in the test materials/manuals for the instruments or in research articles/reports) that met the inclusion criteria for the study (see ). Then, we used the European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations (EFPA) “Review Model for the Description and Evaluation of Psychological and Educational Tests” (Evers, Hagemeister et al., Citation2013; Evers, Muñiz et al., Citation2013 [http://www.efpa.eu/professional-development]) to examine the quality of the test materials (i.e., explanation of the rationale; adequacy of documentation and information provided; paper-pencil-, computer- and web-based tests; and computer-generated reports) and psychometric properties of the identified documented instruments.

Figure 1. Flow chart for the search and inclusion of studies and materials of the assessment instruments to be included for the European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations review (modified after Moher et al., Citation2009). Records refer to the identified publications on the instruments.

Part 1: Survey

A random sample of 410 elementary schools across Norway was invited (by email) to complete an electronic questionnaire about the assessment instruments used to measure children’s proficiency in social functioning and reading. A total of 234 (57%) of the invited schools completed the questionnaire in the spring of 2015. The schools were located in both urban and rural districts across Norway, covered all regions of the country, and enrolled students from a variety of socioeconomic backgrounds. The schools that did not respond to the survey came from the same random sample of municipalities as those that did respond. Additionally, some of the non-respondent schools replied that they not could find time to complete the survey, while others replied that they had nothing to report other than their use of national compulsory assessments and national tests.

Part 2: Systematic Literature Review and Quality Evaluation of Assessment Instruments

Based on the results of the survey, 4 of the social functioning assessment instruments and 28 of the reading assessment instruments that were reported as being used in the schools (see and ) were identified for inclusion in the systematic literature review (see and ). Notably, the schools also reported the use of several instruments that were intervention materials rather than assessments developed by the teachers for informal classroom use, clinical instruments to be used only by certified educational psychologists, and group-based reports on the school environment. Therefore, some of the materials reported by the schools were excluded from the quality evaluation (EFPA review) for the reasons listed in .

Figure 2. Percentage of schools (n = 234) reported use of social functioning assessment instruments.

Table 1. Assessment instruments identified for inclusion or exclusion in the systematic literature review.

The purpose of the systematic literature search was to identify publications on the above-mentioned instruments to be included in the EFPA review. Typically, this information was reported in the assessment materials (manuals, information materials). However, it was also possible that validation studies published as research reports/articles existed in addition to these materials. Therefore, to supplement the information, we conducted an additional systematic literature search using the PRISMA guidelines (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, Citation2009).

Systematic Literature Search Procedures

We applied an extensive search strategy that combined keywords with all relevant synonyms and alternative expressions widely used in the literature for each domain (i.e., social functioning and reading proficiency). shows details of the search and the flow of records of documentation on the assessment instruments and the eligibility criteria used in our study.

In addition to searching for each label or acronym of the instruments listed by the schools (see and ), we identified keywords to search for documentation of the two types of instruments targeting social functioning and reading. We identified the following keywords based on the terms Educational assessment instruments, Social functioning and Reading proficiency as defined in the introduction: Social; Reading; Assessment; Psychometric; Elementary school; and At risk. The search keywords, with accompanying synonyms and alternative expressions for each of the two types of assessment instruments, are listed in Appendices A and B. The OR operator was used between synonyms and the alternative expressions for each keyword, and the AND operator was used between the different keywords. The truncation function * was used to capture different forms of the search words (for instance, assessment vs. assessments or assessing was truncated to assess*; measurement vs. measurements or measuring or measure or measures was truncated to measure*).

The search was conducted in two waves during the period from March 3 2016 to June 30 2016. One search was conducted for the social functioning instruments and one for the reading instruments. To avoid limiting our hits of studies or our documentation of the assessment instruments, we did not restrict the search to any starting point. Furthermore, the literature included materials written in English, Norwegian, Danish, Swedish, and Finnish. Developers and researchers in the field of national assessments and tests initiated by the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training were contacted by email and asked to share studies or technical reports that we might have missed and that pertained to the instruments. In addition, we contacted by email the authors and publishers of assessment instruments in which materials were lacking or not published to obtain as much information as possible for the EFPA review. and show overviews of the assessments with non-available information and those with obtained publications, respectively.

Table 2. Assessment instruments and connected publications included in the European Federation of Psychologists’ Associations review.

and shows that 3 of the 4 social functioning instruments and 24 of the 28 reading instruments met the inclusion criteria for the EFPA review. The 3 social functioning instruments appeared in 3 records, which included published test materials (manuals, information materials) derived from the publishers and/or authors. The 24 included reading assessments appeared in a total of 57 records in which publications of both test materials (manuals, information materials) and studies were included.

EFPA Review Model for the Description and Evaluation of the Assessment Instruments

We used the EFPA review model to evaluate the quality of the assessment instruments that the schools reported using and that met the inclusion criteria described in (Evers, Hagemeister et al., Citation2013; Evers, Muñiz et al., Citation2013; PsykTestBarn, Citation2016). The review model has two parts: One part for the description of the instrument and one part for the evaluation of the instrument. The description consists of the following elements: (1) General description (e.g., instrument name, authors, publisher, date of publication); (2) Classification (e.g., content domains, populations, scales and variables measured, response mode, demands on the test-taker, item formats, intended mode of use, administration mode, time required for administering); (3) Measurement and scoring (e.g., scoring procedure, scales used, transformation for standard scores; (4) Computer-generated reports (e.g., availability, media, complexity, structure, sensitivity to context, modifiability, transparency, style and tone, intended recipients); and (5) Conditions and costs (e.g., documentation, methods of publication, start-up and recurrent costs, prices for reports, test-related and professional qualifications required for use of the instrument).

The evaluation part of the EFPA review form consists of the following elements to be reviewed: (1) quality of the explanation of the rationale, adequacy of documentation, and provided information; (2) quality of the test materials used (e.g., paper-and-pencil tests, computer- and web-based tests); (3) norms (e.g., norm-referenced interpretation, criterion-referenced interpretation); (4) reliability (e.g., data provided, internal consistency, test-retest, equivalence in terms of parallel or alternative forms, item response theory-based method [IRT], inter-rater reliability); (5) Validity (e.g., construct validity, criterion-related validity, overall adequacy); (6) Quality of computer-generated reports (e.g., scope or coverage, reliability, relevance or validity, fairness, acceptability, length, overall adequacy); and (7) final evaluation (e.g., conclusions, recommendations). All reviewed elements in the evaluation part of the form use a rating system with scores of 0 (not possible to rate or insufficient information provided), 1 (inadequate), 2 (adequate), 3 (good), or 4 (excellent). Additionally, 9 (not applicable) was used but not for the reliability or validity elements.

EFPA reviewing procedure

One of the authors completed the EFPA review form for all the included assessment instruments. As a verification check to ensure the consistency and quality of the review, half of the documented instruments were randomly selected for review by an additional reviewer. The additional reviews were distributed equally between two of the other authors, who evaluated the assessment instruments independently of each other and of the main reviewer. The National Assessments and The National Test of Reading Proficiency (NTRP) were chosen as benchmarks and were reviewed by all three reviewers. Initial and follow-up meetings between the three authors responsible for completing the EFPA review form were arranged to discuss the review criteria. An inter-rater variance component analysis to highlight potential review disagreements was used to inform a final meeting, which was organised to establish the final consensus evaluation of all assessment instruments shown in .

A variance component analysis of the overall indicator ratings on the six evaluation elements was conducted to better understand the sources driving differences in ratings and disagreements among the three raters. The average score across the overall indicator ratings on the six evaluation elements was 1.20, with a standard deviation of 1.21; 79% of the ratings were below or equal to 2 (adequate). The largest source of rating differences was accounted for by the main effect of the evaluated tests (36%), indicating relatively large variation in quality among the reviewed tests. The second largest source of rating differences was accounted for by the main effect of the evaluation elements (27%), with highest ratings for the quality of the material (average rating = 2.29) and the lowest ratings for both reliability and validity of the tests (average rating = .56 and .34, respectively). The test-by-element interaction accounted for only 7% of the rating variation, which implies that the tests tended to be rated at a rather homogeneous quality level across the six evaluation elements (i.e., if a test was relatively bad, it tended to be relatively bad in every aspect).

Results

The results are reported in two sections: (1) The results of the survey concerning the elementary schools’ use of educational assessment instruments for social functioning and reading proficiency and (2) the EFPA review of the instruments’ characteristics and the quality of their test materials and psychometric properties.

Use of Social Functioning and Reading Proficiency Assessment Instruments

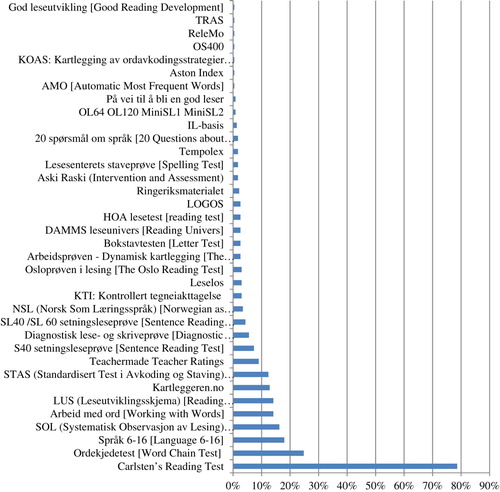

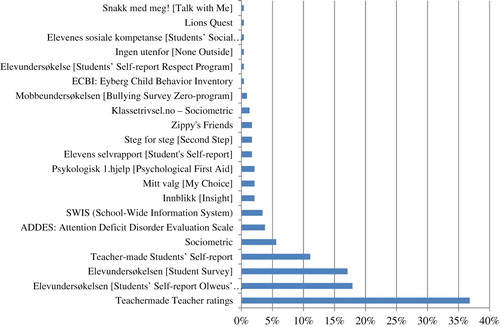

The survey showed that the schools used 21 different social functioning assessment instruments and 36 reading assessment instruments. and show the percentage of Norwegian elementary schools (n = 234) that reported their use of the different instruments. Because the use of national compulsory assessments in reading is required in all Norwegian elementary schools, we did not include them in . We did, however, include them in the review of the descriptions and documented psychometric properties (Research Question 2).

shows that the most frequently used assessments of social skills are those described as “Teacher-made,” followed by “Olweus’ Students’ Self-report on Bullying” and “Students’ Survey of Self-assessment of Learning and Well-being.” Among these, only the informal “Teacher-made” ratings are, as reported by the schools, intended to target social functioning. Regarding the reading assessment instruments (see ), the most frequently used is “Carlsten,” a group-administered reading test without any reported psychometric properties (see and ). Notably, the majority of the reading assessments had a more explicit target focus on specific reading skills (e.g., spelling, decoding, phonological awareness, letter knowledge, graphemes, morphemes, fluency) than on reading comprehension.

shows the total number of schools that reported using educational assessment instruments for children’s social functioning and reading proficiency. Notably, as many as 68.8% of the schools did not use any instruments to assess children’s social functioning, but only 11.1% did not use any instruments to assess reading. Additionally, 9.4% of the schools reported that they did not use any assessment instruments for children’s social functioning or reading proficiency (except the national compulsory assessments in reading for Grades 1 to 3 and the national reading test for Grade 5).

Table 3. Number of elementary schools using Educational Assessment Instruments (EAI) for children’s social functioning and reading proficiency.

The majority of schools reported that they assessed children’s social functioning and reading proficiency either two or more than three times per year (see ). Furthermore, the schools reported whether they used the information derived from the assessments when making decisions to further promote children’s social and reading skills.

Table 4. Assessing frequencies of social functioning and reading in number of elementary schools.

shows that as many as 91.5% of the schools used the results derived from assessments of children’s social functioning. However, as seen in , only 31.2% reported that they used any assessment instrument for social functioning. Additionally, there is a discrepancy between the percentage of schools (88.9%) that reported using reading assessment instruments (see ) and the percentage of schools (98.7%) that used information derived from the results of the assessments to make decisions about reading instruction (see ).

Table 5. Number of Norwegian elementary schools using information derived from the results of assessing children to lead decisions to promote children’s social and reading skills.

In summary, the most frequently used measure was “Teacher-made” for social functioning and the “Carlsten” for reading (when the national mandatory tests are excluded). Notably, the “Teacher-made” and “Carlsten” measures had no documented psychometric properties. Additionally, the findings demonstrated that a lower percentage of the schools reported the use of assessment instruments (31.2% assessed social function and 88.9% assessed reading proficiency) than the use of the results derived from these assessments to promote the development of students’ skills (91.5% used information on social functioning and 98.7% used the results from reading assessments). Furthermore, the descriptive data analyses did not find any relations between the schools’ use of the assessment instruments and their use of information derived from assessing children when making decisions about interventions to promote either social skills or reading skills.

Evaluation of Instruments’ Characteristics, Test Material Quality and Psychometric Properties

The documentation of the instruments included in the EFPA review consisted of manuals, articles, and master’s theses (see ). We were able to use the EFPA review model to assess descriptions of the characteristics and to evaluate the quality and documented psychometric properties of 3 of the social functioning instruments and 24 of the reading instruments that were reported used in Norwegian elementary schools.

Descriptions of the Assessment Instruments’ Characteristics

shows the descriptions of characteristics for the assessment instruments of social functioning and reading proficiency. All reviewed instruments contained some descriptions of their purpose and target group. One of the social functioning instruments was published 17 years ago (1999), whereas the evaluated versions of two others were published within the last year. The reading instruments were published between 1980 and 2016. The two types of instruments were either individually or group administered and took three different forms: teacher ratings, students’ self-reports, and performance assessments or tests. None of the social functioning instruments and only seven of the reading instruments were defined as screening instruments. Two social functioning instruments (Student Survey and Students’ Social Competence) and one type of reading instrument (NTRP) were distributed by the Norwegian Directorate of Education. The Student Survey is compulsory for Grade 7, and the NTRP are compulsory for Grades 1 to 3 and Grade 5 in all Norwegian schools. These have to be completed annually.

Table 6. Descriptions and characteristics for the assessment instruments of social functioning and reading proficiency.

Regarding the response mode, the majority reported the use of paper-pencil as an option either similar to or in addition to direct observation or/and computer-based assessment. Three measures reported the use of computer-based assessment as the only response mode, and one used both direct observation and computer-based options. The item formats of the social functioning measures were Likert scales, open questions, and oral interviews. The majority of the reading measures reported multiple choice (MC) tasks, a similar item format, or MC in addition to Likert scales, open questions, and/or dictation; and 3 of the MC were administered with a time-limit. Two reading instruments (Leseutviklingsskjema [LUS] and Systematisk observasjon av lesing [SOL]) reported the use of a teacher’s observation form, and one (Leselos) used a teacher’s check-form. The majority of scorings were raw scores based on the number of dichotomous responses (right or wrong, yes or no). In addition, 2 of the social functioning measures and 10 of the reading measures reported the use and interpretation of teachers’ observational notes. Furthermore, 6 reading instruments reported the use of cut-off scores, whereas 3 instruments had norms for the cut-off scores based on raw scores or z-scores. Additionally, 7 reading measures used normed scores based on raw-scores, z-scores, or stanines. Of the reading assessment instruments, 10 reported the time required to administer them, whereas none of the social functioning assessments reported this. Moreover, 7 of the reading instruments required test-related qualifications. None of the 3 social functioning instruments reported any validation studies, while 11 of the 24 reading instruments did report such studies. Of these studies, 6 were presented in a single publication, typically the manual, whereas 5 instruments were reported in two or more publications. Two measures reported on studies conducted in other countries in addition to those conducted with Norwegian samples (Nielsen et al., Citation2008; Sutherland & Smith, Citation1991).

Quality of Test Materials and Psychometric Properties

Information from the EFPA review of the assessment materials and documented psychometric properties is shown in . The detailed evaluation criteria are described in the EFPA manual (see Evers, Hagemeister et al., Citation2013; Evers, Muñiz et al., Citation2013). First, we judged the quality of the explanation of the rationale and the adequacy of the documentation and provided information. We found that one of the social functioning measures (Student’s Self-Report) was adequately explained, whereas the other two had no information that we could rate. Regarding the explanations contained in the reading instrument materials, one was rated as excellent (Language 6–16), eight were rated as good, six were rated as adequate, and nine had inadequate explanations.

Table 7. Overview of material quality and documented psychometric properties of the assessment instruments of social skills and reading skills.

Second, in rating the quality of the applicable paper-and-pencil test materials, 1 measure was rated as excellent (Language 6–16), 12 were rated as good, 7 were adequate, 4 were inadequate, and 3 had no applicable information. Regarding the applicable computer-based or web-based materials, 2 met the criteria for excellence (Kartlegging av ordavkodingsstrategier [KOAS] and LOGOS), 3 were rated as good (Student Survey, kartleggeren.no and SOL), 2 instruments had no information available for rating (Aski Raski and LUS), and there were no applicable materials for 20 of the instruments. The quality of the applicable computer-generated reports (e.g., scope or coverage, reliability, relevance or validity, fairness, acceptability, length, overall adequacy) was rated as good for the Student Survey and LOGOS, adequate for kartleggeren.no and KOAS, and inadequate for Aski Raski; for LUS and SOL, there was no information that could be rated.

Finally, we reviewed the instruments’ documented psychometric properties in terms of norms (e.g., norm-referenced interpretation, criterion-referenced interpretation), reliability (e.g., data provided, internal consistency, test-retest, equivalence in terms of parallel or alternative forms, item response theory-based method (IRT), inter-rater reliability, and validity (e.g., construct validity, content validity, criterion-related validity, overall adequacy). Of the 27 instruments, 11 had no applicable norms, 6 had no information that could be rated, 4 had good norms, 1 was adequate, and 5 were inadequate. The majority of the instruments (none of the social functioning and 18 of the 24 reading instruments) had no documented information on reliability. The overall adequacy of the reported reliability of the six reading measures was rated as good for 3 (Lesesenterets Spelling Test, Word Chain Test, and Language 6–16), adequate for 2 and inadequate for 1. Regarding the overall adequacy of validity, only 5 instruments had any documentation available to rate. Of these, 2 had good validity (Word Chain Test and Language 6–16), while 1 was adequate and 2 were rated as inadequate.

In summary, although the quality of most of the test materials (i.e., explanation of rationale; adequacy of documentation and provided information; paper-pencil-, computer- or web-based materials; and computer-generated reports) was good or adequate, there was no evidence to support the overall quality of the psychometric properties for the majority of the reviewed assessment instruments. Although most of the instruments may be of practical use for experienced teachers, further development and research are required to ensure their quality for use in practice. Additionally, it is noteworthy that the authors and developers of the instruments provided as qualitative or dynamic observation assessments (e.g., SOL, The Working Test) explained that reliability and validity were irrelevant.

Discussion

Our study reveals important information about the use of educational assessments in Norwegian schools and the quality of the assessment instruments used; this information is relevant to both future research and policy development. First, our study demonstrates that Norwegian elementary schools typically assessed children’s reading proficiency more often than they assessed social functioning, and they used a wider variety of reading assessment instruments than of social functioning instruments. This large difference in use may not only reflect very different traditions of assessment in the domains of social and academic achievements but also the recency of interest in measuring social skills compared to reading skills. The most frequently used measures in the two domains, with the exceptions of national compulsory tests and assessments, were teacher-made social functioning assessments and the “Carlsten” reading test, neither of which has documented psychometric properties. The majority of schools used information derived from assessments of children’s skills to make decisions about interventions, but this seems to be based more on informal teacher ratings than on the educational assessment instruments that the schools report using.

Our evaluation of the quality of the instruments revealed that the vast majority of the reviewed applicable materials had good descriptions of their purpose and content. However, our findings regarding the explanation of the rationale, the adequacy of the documentation and information provided, and the evidence of psychometric properties demonstrated, with very few exceptions, an overall weakness and lack of applicable quality (see ). This is highly troublesome, and addressing these problems should be a priority in both educational research and policy in the years to come.

Similar to the findings of previous studies (e.g., Cordier et al., Citation2015; Merrell, Citation2001; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment], Citation2014), our findings demonstrate that the documented educational assessment instruments that were reported as being used in schools to assess children’s social functioning and reading proficiency varied with respect to the informal or formal structure of their assessment methods (e.g., open notes of teacher ratings versus criterion-based tests), the level of interactivity (e.g., static versus dynamic), whether they were summative or formative (e.g., assessment of learning versus assessment for learning), the assessment structure (e.g., presentation of the items to the test-taker), the response formats (e.g., selected or constructed items), and the item scoring (e.g., hand scoring versus computer-based scoring). However, our view is that assessments and interventions are often intertwined and that schools use what is readily available. Considering the lower percentage of schools reporting that they used educational assessment instruments compared to the percentage of schools reporting the use of information derived from the results of such assessments, the answer to the first research question seems somewhat inconsistent. This may be interpreted as indicating that schools are using information derived from informal assessments of children’s social functioning and reading proficiency more than they are using formal assessment instruments. Moreover, we do not know from these answers whether and how schools actually use the assessments for their intended purpose. Our understanding is that schools have extensively used teacher-made assessments and informal classroom observations to assess and design interventions to promote students’ skills. Furthermore, this may be because the available educational assessments are time-consuming and not efficient for teachers to use in practice (Elliott et al., Citation2007; Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education], Citation2011a). However, arbitrary and inaccurate measures may misinterpret children’s needs for additional support to prevent or minimize difficulties, and such measures may also initiate interventions that do not meet students’ needs.

Although the quality of the test materials (i.e., explained rationale, adequacy of documentation, provided information, paper-pencil and computer- or web-based test materials, computer-generated reports) was rated as good or adequate for approximately half of the reviewed measurement materials, our findings regarding the quality of the documented psychometric properties contrast this judgement. Thus, our findings support the conclusions of other systematic reviews of assessment measures, namely, that the psychometric evidence is weak or lacking (e.g., Cordier et al., Citation2015; Floyd et al., Citation2015; Gotch & French, Citation2014; Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment], Citation2014). That said, we did not analyse the measurements’ original data but rather reviewed the information and the documented materials of the instruments provided to us by the authors and publishers and obtained through the literature search. Moreover, we like to note that the lack of psychometric studies of an assessment instrument does not imply that the psychometric properties are weak. However, it is troubling that we lack knowledge about the psychometric properties of the majority of the reported instruments. This means that we cannot be sure when using these assessment instruments that the inferences and judgments we make are valid. If the conclusions drawn based on these instruments are erroneous this can lead to negative consequences for students at risk.

Limitations

Two features of this study limit the conclusions we can draw about schools’ use of educational assessment instruments that measure social functioning and reading proficiency. First, the response rate (57%) to the electronic survey sent to schools regarding their use of educational assessments might limit the representativeness of the sample. However, surveys of organisations (e.g., schools) are expected to have a lower response rate than data collected from individuals (Baruch & Holtom, Citation2008). Additionally, electronic data collection efforts resulted in response rates as high as or higher than traditional methods of data collection (e.g., mail and phone call interviews). In fact, there is no scientifically proven minimally acceptable response rate. However, a response rate of 60% has been used as a “rule of thumb” (Johnson & Wislar, Citation2012). Based on research presented above, the response rate covered 234 elementary schools, which is assumed to be an acceptable sample of a representative group of Norwegian elementary schools. Although the response rate was not optimal, the responses offer an interesting picture of the variance in the schools’ use of assessment instruments. Additionally, it might be assumed that the non-respondent schools do not use any other assessment instruments beyond those used by the schools that responded. Second, due to the response rate, we do not know if there are other assessment instruments that are used in the schools that did not participate in this study. However, the initial search of the systematic literature review did not obtain any hits of available measurements, except of those not included in the current study.

Moreover, the question of schools’ use of educational assessments of social functioning and reading proficiency is limited to which such assessments are used and how they are used, rather than detailed information regarding whether the assessments are actually used for their intended purpose. This said, this study focused on a general overview rather than on differences between assessments in each of the two areas and therefore, did not address whether the assessments were used as intended. Thus, we have no guaranties of how the assessments are used in practice.

Implications of this Study for Practice, Research and Policy

Several implications arise from the findings of this study. Assessing children’s social functioning and reading proficiency in an educational context is complex. It requires measurements that use differentiated methods and address children’s growth in both social and academic learning. Measurements must also provide reliable and valid information about what they intend to measure. One reason for the lack of documentation and evidence of educational assessments might simply be that there is no general expectation that the quality of assessments will be explicitly stated. As an example, for mandatory national tests and assessments, this information exists only as internal documents or technical reports. Consequently, important information about the assessments’ quality is hidden from the end-users for some instruments, while it is communicated for others. To improve this situation, standards or checklists for tests comprising essential quality characteristics could be established. Consequently, suggestions for better documentation of assessment quality might challenge test developers and raise awareness of the schools’ use of evidence-based educational assessment instruments.

To improve the practice of screening and monitoring children’s learning and development in the domains of social functioning and reading, there is a need for more differentiated assessment instruments that are easy and efficient for teachers to use. Additionally, social functioning and reading proficiency should be assessed simultaneously within and across school years to guide instruction, monitor children’s responses to instruction, and monitor children’s progress in the two domains to obtain a basis for analysing variations and mutual causal influences. Additionally, because we do not know whether schools are using assessment instruments for decision making to lead instructions and whether the assessments are actually used as intended, more research in this field is needed. Given the present findings regarding assessments of children’s social functioning and reading proficiency, an extended and explicit evaluation of the quality of educational assessment instruments in terms of constructs, materials, and psychometrics should be prioritised in educational policy and practice. This could ensure more appropriate use of teachers’ time and efforts to identify struggling children early and provide them with less intensive support, which is effective when implemented early.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the participating schools’ staff for information to the study.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

ORCID

Anne Arnesen http://orcid.org/0000-0001-8356-9195

References

- Algozzine, B., Wang, C., & Violette, A. S. (2011). Reexamining the relationship between academic achievement and social behavior. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 13(1), 3–16. doi: 10.1177/1098300709359084

- Allard, B., Rudqvist, M., Sundblad, B., Corneliussen, G. G., Smeland, O. I., & Moen, S. (2006). Den nye LUS-boken : Leseutviklingsskjema – LUS : en bok om leseutvikling. Oslo: Cappelen akademisk forlag. Publications included in the evaluation review are marked with an asterisk (*).

- Arnesen, A., Meek-Hansen, W., Ottem, E., & Frost, J. (2013). Barns vansker med språk, lesing og sosial atferd i læringsmiljøet: En undersøkelse basert på lærervurderinger og leseprøver i grunnskolens 2.-5.trinn. Psykologi i kommunen, 6, 41–56.

- Asbjørnsen, A. E., Obrzut, J. E., Eikeland, O.-J., & Manger, T. (2010). Can solving of Wordchains be explained by phonological skills alone? Dyslexia, 16, 24–35. doi: 10.1002/dys.394

- Aschim, A. K. (2006). Damms leseunivers 1 Ressursperm. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Ask, I. (2016, August, 30). Aski Raski [Software and WebApplication]. Unpublished instrument. Retrieved from http://www.askiraski.no/index.cfm

- Baruch, Y., & Holtom, B. (2008). Survey response rate levels and trends in organizational research. Human Relations, 61(8), 1139. doi: 10.1177/0018726708094863

- Beauchamp, M. H., & Anderson, V. (2010). Social: An integrative framework for the development of social skills. Psychological Bulletin 2010, 136(1), 39–64.

- Boada, R., Willcutt, E. G., & Pennington, B. F. (2012). Understanding the comorbidity between dyslexia and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Topics in Language Disorders, 32(3), 264–284. doi: 10.1097/TLD.0b013e31826203ac

- Carlsten, C. T. (2016). Carlstenprøvene. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- Cordier, R., Speyer, R., Chen, Y., Wilkes-Gillan, S., Brown, T., Bourke-Taylor, H., … Leicht, A. (2015). Evaluating the psychometric quality of social skills measures: A systematic review. PLoS One, 10(7), doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0132299

- Cronbach, L. J., & Meehl, P. E. (1955). Construct validity in psychological tests. Psychological Bulletin, 52, 281–302. doi: 10.1037/h0040957

- Dahle, A. E., Knivsberg, A.-M., & Andreassen, A. B. (2011). Coexisting problem behaviour in severe dyslexia. Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs, 11(3), 162–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-3802.2010.01190.x

- DeRosier, M. E., & Lloyd, S. W. (2011). The impact of children’s social adjustment on academic outcomes. Reading & Writing Quarterly, 27(25-22), 25–47. doi: 10.1080/10573569.2011.532710

- Duna, K. E., & Frost, J. (1999). Elevens selvrapport: Systematisk kartlegging av elevens subjektive forståelse av egen livssituasjon. Jaren: PP-tjenestens materiellservice. Retrieved from http://www.aspergerbedriftene.no/materiellservice/butikk/elevens-selvrapport/1-laererveiledning-20-noteringshefter-56-kort-3-esker-m-m/

- Duna, K. E., Frost, J., Godøy, O., & Monsrud, M.-B. (2003). Kartlegging av barn og unges lese- og skrivevansker med Arbeidsprøven. Oslo: Bredtvet kompetansesenter.

- Durlak, J. A., & Weissberg, R. P. (2011). Promoting social and emotional development is an essential part of students’ education. Human Development, 54(1), 1–3. doi: 10.1159/000324337

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x

- Elliott, S. N., Huai, N., & Roach, A. T. (2007). Universal and early screening for educational difficulties: Current and future approaches. Journal of School Psychology, 45(2), 137–161. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.11.002

- Engen, L., & Helgevold, L. (2012). Leselos: Veiledningshefte. Stavanger: Lesesenteret, Universitetet i Stavanger. Retrieved from www.lesesenteret.no ISBN: 978-82-7649-071-8

- Evensen, K. B. (2011). Forebygging av lesevansker: En beskrivelse av IL-basis sitt potensial til å predikere barns leseferdighet i 2. klasse (Master’s Thesis). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/10852/31428

- Evers, A., Hagemeister, C., & Hostmaelingen, A. (2013). EFPA review model for the description and evaluation of psychological and educational tests (Tech. Rep. Version 4.2. 6). Brussels: European Federation of Psychology Associations.

- Evers, A., Muñiz, J., Hagemeister, C., Høstmælingen, A., Lindley, P., Sjöberg, A., & Bartram, D. (2013). Assessing the quality of tests: Revision of the EFPA review model. Psicothema, 25(3), 283–291.

- Fagbokforlaget. (2016). Kartleggeren.no: [Computer software]. Unpublished material. Retrieved from http://kartleggeren.no/

- Floyd, R. G., Shands, E. I., Alfonso, V. C., Phillips, J. F., Autry, B. K., Mosteller, J. A., … Irby, S. (2015). A systematic review and psychometric evaluation of adaptive behavior scales and recommendations for practice. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 31(1), 83–113. doi: 10.1080/15377903.2014.979384

- Frost, J., & Nielsen, J. C. (2000). IL-basis – et prøvemateriell for å beskrive og vurdere barns leseforutsetninger og tidlige leseutvikling. Norsk psykologforening.

- Gallefoss, B. S. (1996). ASTON INDEX, en test for observasjon og vudering av lese/skrive/språkvansker : en analyse av testresultat, med hovedvekt på utføringsdelen (54 elever, pluss 6 voksne) (Master’s Thesis). Oslo: University of Oslo.

- García-Madruga, J. A., Vila, J. O., Gómez-Veiga, I., Duque, G., & Elosúa, M. R. (2014). Executive processes, reading comprehension and academic achievement in 3th grade primary students. Learning and Individual Differences, 35(0), 41–48. doi:http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.07.013

- Gjesdal kommune. (2011). SOL: Systematisk observasjon av lesing. [Computer software]. Retrieved from http://www.sol-lesing.no/

- Gotch, C. M., & French, B. F. (2014). A systematic review of assessment literacy measures. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 33(2), 14–18. doi: 10.1111/emip.12030

- Gresham, F. (2007). Response to intervention and emotional and behavioral disorders: Best practices in assessment for intervention. Assessment for Effective Intervention, 32(4), 214–222. doi: 10.1177/15345084070320040301

- Gustafsson, J.-E., Allodi Westling, M., Åkerman, A., Eriksson, C., Eriksson, L., Fischbein, S., … Ogden, T. (2010). School, learning and mental health: A systematic review. Stockholm: The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, The Health Committee.

- Heckman, J. J. (2000). Policies to foster human capital. Research in Economics, 54(1), 3–56. doi:http://doi.org/10.1006/reec.1999.0225

- Heckman, J. J. (2011). The economics of inequality: The value of early childhood education. American Educator, 35(1), 31–35.

- Hoover, W. A., & Gough, P. B. (1990). The simple view of reading. Reading and Writing, 2(2), 127–160. doi: 10.1007/bf00401799

- Høien, T. (2007). Håndbok til LOGOS: Teoribasert diagnostisering av lesevansker. Bryne: Logometrica.

- Høien, T., & Lundberg, I. (1988). Stages of word recognition in early reading development. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 32(4), 163–182. doi: 10.1080/0031383880320402

- Høien, T., & Lundberg, I. (1991). KOAS: Kartlegging av ordavkodingsstrategiene. Stavanger: Senter for leseforsking.

- Høien, T., & Tønnesen, G. (2008a). Instruksjonshefte til Ordkjedetesten. Bryne: Logometrica.

- Høien, T., & Tønnesen, G. (2008b). S40: Setningsleseprøven. Lesesenteret, Universitetet i Stavanger; Logometrica.

- Johnsen, K. (1980). Noteringshefte med rettledning til Diagnostisk lese/skriveprøve 1 (1-3.trinn) og 2 (3. – 9.trinn). Drammen: PP-tjenestens materiellservice. Retrieved from http://www.materiellservice.no/produktkategori/lese-og-skriveprover/

- Johnson, T. P., & Wislar, J. S. (2012). Response rates and nonresponse errors in surveys. (viewpoint essay). JAMA, The Journal of the American Medical Association, 307(17), 1805. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3532

- Klinkenberg, J. E., & Skaar, E. (2003). STAS. Manual. Brandbu: PP-tjenestens Materiell Service.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet. [The Norwegian Ministry of Education]. (2009). Rett til læring. NOU 2009:18. Oslo: Departementenes servicesenter.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education]. (2011a). Meld. St. 18 (2010-11). Læring og fellesskap. Tidlig innsats og gode læringsmiljøer for barn, unge og voksne med særlige behov. In Kunnskapsdepartementet (Ed.), (Vol. 18). Oslo.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education]. (2011b). Vurdering av verktøy som brukes til å kartlegge barns språk i norske barnehager.

- Kunnskapsdepartementet [The Norwegian Ministry of Education]. (2017). Meld. St. 21 (2016–2017). Lærelyst – tidlig innsats og kvalitet i skolen.

- Lundberg, I., & Herrlin, K. (2008). God leseutvikling: kartlegging og øvelser. Oslo: Cappelen akademisk forlag.

- Lyster, S.-A. H., & Tingleff, H. (2002). Ringeriksmaterialet kartlegging av språklig oppmerksomhet hos barn i alderen 5-7 år. Test/kopieringsoriginaler. Oslo: Cappelen Damm.

- McIntosh, K., Reinke, W. M., Kelm, J. L., & Sadler, C. A. (2012). Gender differences in reading skill and problem behavior in elementary school. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions. doi: 10.1177/1098300712459080

- Merrell, K. W. (2001). Assessment of children’s social skills: Recent developments, best practices, and New directions. A Special Education Journal, 9(1-2), 3–18. doi: 10.1080/09362835.2001.9666988

- Miles, S. B., & Stipek, D. (2006). Contemporaneous and longitudinal associations between social behavior and literacy achievement in a sample of Low-income elementary school children. Child Development, 77, 103–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00859.x

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS Medicine, 6(6), e1000097. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed1000097 doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- National Assessment Governing Board. (2013). Reading framework for the 2013 national assessment of educational progress. US Department of Education. Washington, DC: Author. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED542063.pdf

- Nielsen, J. C. (2010). Beskrivelse og vurdering af elevernes læsning og stavning: Vejledende materialer og diagnostiske prøver med henblik på målfastsættelse og planlægning. København: Danmarks Pædagogiske Universitet.

- Nielsen, J. C., Kreiner, S., Poulsen, A., & Søegård, A. (1995). Lærerveiledning til setningsleseprøvene SL60 og SL40. Senter for leseforsking.

- Nielsen, J. C., Kreiner, S., Poulsen, A., & Søegård, A. (2008). Lærerveiledning til leseprøvene OL64, OL120, MiniSL1 og MiniSL2. Norsk versjon: Monsrud, M.-B., Godøy, O., Heller, A. K., & Thurmann-Moe, A. C. Oslo: Cappelen Akademisk.

- NOU 2015:8 (Official Norwegian Reports). The school of the future renewal of subjects and competences. Oslo: The Norwegian Ministry of Education and Research.

- OECD. (2015). Skills for social progress: The power of social and emotional skills. OECD Skills Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Oslo kommune. (2012). LUS-håndboken: Bruk av leseutviklingsskjema i grunnskolen. Oslo: Oslo kommune, Utdanningsetaten.

- Ottem, E., & Frost, J. (2005). Språk 6-16. Screening test. Oslo: Bredtvet kompetansesenter.

- PsykTestBarn. (2016). EFPA review model for the description and evaluation of psychological and educational tests. Test Review Form and Notes for Reviewers. Version 4.2.6. Retrieved from http://www.psyktestbarn.no/CMS/ptb.nsf

- Rivera, M., Al-Otaiba, S., & Koorland, M. (2006). Reading instruction for students with emotional and behavioral disorders and At risk of antisocial behaviors in primary grades: Review of literature. Behavioral Disorders, 31(3), 323–339. doi: 10.1177/019874290603100306

- Siddiq, F., Hatlevik, O. E., Olsen, R. V., Throndsen, I., & Scherer, R. (2016). Taking a future perspective by learning from the past – A systematic review of assessment instruments that aim to measure primary and secondary school students’ ICT literacy. Educational Research Review, 19, 58–84. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2016.05.002

- Sivertsen, R. (1990). Aston Index. Prøve for observasjon og vurdering av lese-, skrive- og språkvansker. Brandbu: Skolepsykologi-materiellservice.

- Skaathun, A. (2013). Lesesenterets staveprøve. Stavanger: Universitetet i Stavanger. Retrieved from http://lesesenteret.uis.no/boeker-hefter-og-materiell/boeker-og-hefter/lesesenterets-staveprove-article85269-12686.html. ISBN: 978-82-7649-079-4

- Solheim, O. J. (2015a). Kartleggingsprøven i lesing for 1. trinn. Rapport basert på ordinær gjennomføring våren 2015. Stavanger. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Solheim, O. J. (2015b). Kartleggingsprøven i lesing for 2. trinn. Rapport basert på ordinær gjennomføring våren 2015. Stavanger: Universitetet i Stavanger. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Solheim, O. J. (2015c). Kartleggingsprøven i lesing for 3. trinn. Rapport basert på ordinær gjennomføring våren 2015. Stavanger: Universitetet i Stavanger. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Standards & Testing Agency. (2015). Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/standards-and-testing-agency

- Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment]. (2014). Dyslexi hos barn och ungdomar - tester och innsatser. En systematisk litterauröversik [Dyslexia in children and adolescence – Tests and efforts: A systematic review]. Stockholm: Statens beredning för medicinsk utvärdering [Swedish Council on Health Technology Assessment].

- Stewart, R. M., Benner, G. J., Martella, R. C., & Marchand-Martella, N. E. (2007). Three-Tier models of reading and behavior: A research review. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 9(4), 239–253. doi: 10.1177/10983007070090040601

- Støle, H., Mangen, A., & Stangeland, E. B. (2015). Den nasjonale prøven i lesing på 5.trinn 2015. Stavanger: Universitetet i Stavanger. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Sutherland, M. J., & Smith, C. D. (1991). Assessing literacy problems in mainstream schooling: A critique of three literacy screening tests. Educational Review, 43(1), 39–48. doi: 10.1080/0013191910430104

- Terras, M. M., Thompson, L. C., & Minnis, H. (2009). Dyslexia and psycho-social functioning: An exploratory study of the role of self-esteem and understanding. Dyslexia, 15(4), 304–327. doi: 10.1002/dys.386

- Thorndike, R. M., & Thorndike-Christ, T. (2014). Measurement and evaluation in psychology and education (8th ed). Harlow: Pearson.

- Topstad, I. (2000). Leseklar? Kartlegging av språklig bevissthet i 1. – 2. Klasse. Kristiansand: Arbeid med ord læremidler A/S.

- Topstad, I. (2001). Kartlegging av leseferdighet 2. klasse. Kristiansand: Arbeid med ord Læremidler A/S.

- Undheim, A. M., Wichstrøm, L., & Sund, A. M. (2011). Emotional and behavioral problems among school adolescents with and without reading difficulties as measured by the youth self-report: A one-year follow-up study. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 55(3), 291–305. doi: 10.1080/00313831.2011.576879

- Utdanningsdirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training]. (2011). Rammeverk for kartleggingsprøver på barnetrinnet. Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training]. (2015). Nasjonale prøver. 2015. Lesing 5. Trinn [National Tests. Reading Grade 5]. Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet. Received on request from the Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training.

- Utdanningsdirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training]. (2016, February 23). Elevundersøkelsen. [Student Survey]. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/tall-og-forskning/brukerundersokelser/elevundersokelsen/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training]. (2016, March 30). Elevenes sosiale kompetanse - hva kan du som lærer gjøre? Kartlegging av klassens sosiale kompetanse [Students’ Social Competence]. Retrieved from http://www.udir.no/laring-og-trivsel/laringsmiljo/psykososialt-miljo/sosial-kompetanse/struktur-og-regler/

- Utdanningsdirektoratet [The Norwegian Directorate for Education and Training]. (2016). Metodegrunnlaget for nasjonale prøver. Oslo: Utdanningsdirektoratet.

- Welsh, M., Parke, R., Widaman, K., & O’Neill, R. (2001). Linkages between children’s social and academic competence: A longitudinal analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 39(6), 463–482. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(01)00084-X