ABSTRACT

Perceptual assessment is the basis for diagnosis and evaluation of treatment in speech–language pathology (SLP). Students need to practise assessment skills. A web-based platform with cases and expert feedback in cleft palate disorders was developed in national collaboration. The aim of the study was to evaluate the results of individual training on assessment skills in SLP students and their perception of e-learning. Forty-five students performed tests using a pre- and post-test set-up. Perceptual assessments were demonstrated and instructions provided during teacher-led activities in ongoing fully scheduled courses; students were then individually trained in their free time. Reference samples were available. A significant improvement was found in rating and phonetic transcriptions after training. Positive comments concerned accessibility and practice time.

Introduction

In this paper we present a tool for e-learning of perceptual assessment in speech–language pathology (SLP) and the results of an initial evaluation of the skill of using e-learning exercises for training of auditory perceptual assessment. This tool is expected to ensure that training in standardized procedures for documentation and analysis will be nationally uniform in clinical education in SLP.

Auditory and visual perceptual assessment of speech, voice, language, and swallowing disorders are central as the basis for diagnosis and evaluation of treatment of communication and swallowing disorders. Such assessments are performed daily by speech–language pathologists (SLPs). Assessment skills must be practised in order to reach the goal of making highly reliable clinical assessments. However, while practice and repetition improve learning outcomes, a blended approach that is characterized by a diversity of activities has been reported to be well-received by students (Phillips, Citation2015). In SLP education, skills training is traditionally carried out using demonstrations and teacher-led exercises. However, while teaching resources may limit such training to a few occasions, teacher-led activities still seem useful for introduction and discussion of the area focused upon.

Speech assessment skills are enhanced by an understanding of the features of the relevant speech deviances and repetition of assessment performance (Howard & Heselwood, Citation2002). Achieving the necessary skills takes considerable time and lack of availability of high-quality material may hamper the process. However, the considerable amount of time given to perceptual analysis is worthwhile as it saves time in the management that follows (Perkins & Howard, Citation1995). With the use of computer-based material, increased availability of training possibilities is expected (Howard & Heselwood, Citation2002).

Web-based e-learning by students conducting activities independently, and for which they are responsible, covers skills training of various kinds and supports the integration of knowledge and skills in clinical education (Kahn, Citation2005, p. 3). Also, e-learning has the advantage that students can utilize educational materials and exercises to different degrees while studying the same course and attain the same learning outcomes, although their pathways to success are different (Arkorful & Abaidoo, Citation2015).

Reliability refers to the extent to which a method for assessment provides the same result in repeated measurements. Training has been found to improve reliability of perceptual speech assessment (Iwarsson & Reinholt Petersen, Citation2012; Lee, Brown, & Gibbon, Citation2008). Unwanted variability in perceptual assessment arises from variations in listeners’ perceptions of speech and in the assessment task itself. Listeners’ references are shaped by their previous experience of different voices (Keuning, Wieneke, & Dejonckere, Citation1999; Kreiman, Gerratt, Kempster, Erman, & Berke, Citation1993). Language background can also be a source of systematic error variation (Lee, Brown, & Gibbon, Citation2008; McAllister, Flege, & Piske, Citation2002). Attention deficits when listening may affect both intra- and inter-listener reliability (Kreiman, Gerratt, Precoda, & Berke, Citation1992). Factors pertaining to the assessment task can also affect reliability. For example, listening to several dimensions in the speech signal at the same time is difficult (Kent, Citation1996), and may lead listeners to base their assessment on different perceptual aspects of the speech signal (Kreiman et al., Citation1992; McAllister, Citation2003).

Reliability can be improved through definitions of perceptual terms (Keuning et al., Citation1999), anchor stimuli (Eadie & Kapsner-Smith, Citation2011; Shrivastav, Sapienza, & Nandur, Citation2005), reference voices (Granqvist, Citation2003), standardization of the speech material (Klintö, Salameh, Svensson, & Lohmander, Citation2011), and recording medium (Klintö & Lohmander, Citation2017). Thus, methodological knowledge and skills training are crucial for reliable perceptual assessments.

Although perceptual assessments can be supplemented by acoustic analysis of the speech signal or visualization of the vocal tract, physical measurements do not necessarily reflect what the ear and the brain perceive (Howard & Heselwood, Citation2002; Kent, Citation1996), and therefore lack perceptual validity. The people listening to the speaker determine whether or not they perceive an individual’s speech as different. Thus, in the clinical setting, speech should primarily be perceptually assessed (Shuster, Citation1993).

Previous research on effectiveness of multimedia design principles refers to cognitive theories on load and dual coding (e.g., Issa et al., Citation2011). While the optimal use of and connection between two pathways in working memory to process verbal and visual information, respectively, are highlighted as beneficial for learning, a cognitive load caused by instructions may inhibit the effect. For SLPs, the auditory signal is the main component in perceptual speech assessment and one crucial factor for the development of a reliable skill seems to be access to repetitive presentation of the samples (Issa et al., Citation2011). By offering a selection of assessment tasks, a website platform provides flexibility in terms of both when and where training in perceptual assessment can be performed. Students take responsibility for their own training, while at the same time the educational institution is required to check their acquired knowledge and practical skills according to course and examination objectives. It is important to balance education control and the student’s freedom to take responsibility, as too much control can hamper creativity and the drive to learn (McAllister et al., Citation2014). A website providing perceptual assessment training enables self-directed learning and also support in developing professional skills. It also provides a model for reliability analysis.

Within the SLP programme, perceptual training is carried out within the practicum, laboratory sessions, and seminars. As the need for training differs among the students, it is considered beneficial if each student can decide on her/his own need for training and is able to take responsibility for that training (Kahn, Citation2005, p. 3). An interactive website, fulfilling these requirements, has thus been developed. The website, PUMA – Project Utilizing Multimedia Applications – was originally developed for training in assessment of cleft palate speech, in order to support learning within a specific course on the SLP programme at the University of Gothenburg, Sweden (Lohmander et al., Citation2000). The development of methods for speech assessment and results from research projects in the area of cleft palate formed a base for implementation of agreed routines for speech data collection and analysis within the cleft palate teams. The procedures were implemented within the SLP programmes in Sweden, with agreed learning goals and activities (Lohmander, Eliasson, & Larsson, Citation2010).

To date, the elaborated version of the PUMA website – Practical education Using Multimedia Application – consists of a main page and sub-categories in the area of speech and communication disorders related to cleft palate. Short, basic information about the condition or sub-categories is given, followed by information and exercises within the different domains of assessment. Recommendations on documentation are given, as well as opportunities to perform analysis from audio files and video clips and interactive forms with answers. The answers, hereafter “expert consensus”, are based on national agreement of assessment by the 12 trained expert SLPs in the Swedish cleft palate teams. In consensus, the same experts assessed audio samples for the occurrence, degree, and amount of different cleft speech errors. The reference samples, with different error types, degree or amount of deviances, are included to familiarize students with the error types, to calibrate, and, ultimately, to enable reliable assessments. Reference samples, i.e., anchor stimuli, providing clear examples of specific traits, have been shown to reduce variation and increase agreement between listeners (Eadie & Kapsner-Smith, Citation2011).

The interactive activities include both perceptual and instrumental analysis of speech production (phonetic transcription, rating of speech variables, evaluation of instrumental registrations). The tools for interactive good practice in speech assessment, in the area of speech disorders related to cleft palate, consist of audio and video clips of typical situations, cases, or problems. A series of questions on facts is also provided. Elements of the exercises should be completed within the course. An immediate response based on expert consensus is received on some elements of the exercises, whereas others should be discussed at seminars. The remaining material can be used by the individual student, according to his/her own choice, to fulfil the requirements of the course as well as the overall learning outcomes of the SLP programme.

The aim of the project was to evaluate the result of individual training with an e-learning tool on assessment skills related to cleft palate speech in SLP students, and to evaluate students’ perception of e-learning. Two research questions were posed:

Can self-controlled student training in auditory perceptual assessment, by phonetic transcription and scale rating of speech deviances related to cleft palate (hypernasality, hyponasality, audible nasal air leakage, reduced pressure on consonants), improve assessment skills in SLP students?

To what extent do the students use the e-learning tool and how useful do they think it is?

As the most significant tool for professional work and research in the area of speech–language pathology is perceptual assessment; a skill that has to be learned and sedulously practised, the goal is available and reliable material for skill training in the different relevant areas. An additional aim within the project was therefore to organize an expansion of the content of the web-based platform to include other sub-areas within SLP where perceptual assessment is the core procedure in diagnosis and evaluation of treatment. These areas include neuromotor speech disorders, voice disorders, and swallowing disorders.

Materials and Method

Evaluation of Skills Training

Pilot Study

A pilot study was carried out with five students on the SLP programme at Linköping University in Sweden. Materials and instructions conducted for the main study were used (see below). The results revealed an improvement in assessment skills in terms of a higher number of judgements that were in accordance with the experts after training than before training. The access to and logistics of the audio files were satisfactory. Suggestions on how to make the instructions and forms clearer were given. Amendments were carried out accordingly.

Informants

In the main study 55 students, on two different SLP programmes in Sweden, participated, together with their respective course leaders. Ten students who completed only the pre- or post-test were excluded. A total number of 45 students performed pre- and post-tests and training, 26 at Karolinska Institutet (semester five) and 19 at Lund University (semester three).

Test Material

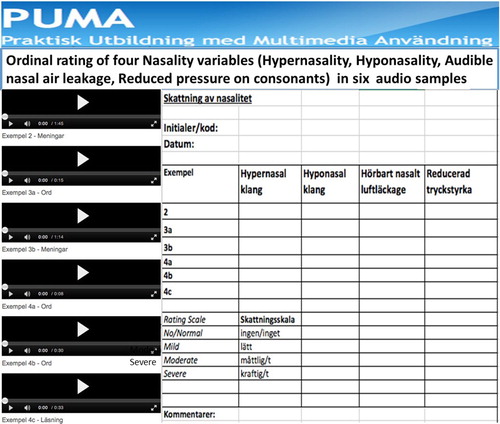

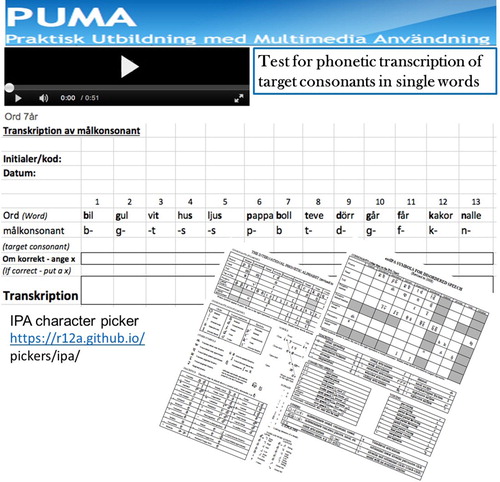

Detailed instructions for the test, together with two forms, one for the phonetic transcription, () and one for the scale rating (), were distributed. The test for phonetic transcription contained one audio file with the speech material, 13 single words, elicited by picture naming from a seven-year-old child with a speech disorder related to cleft palate. Each word contained a target consonant, i.e., a consonant known to be vulnerable for cleft palate speech deviances, and the task was to perform a narrow phonetic transcription of each target consonant. Charts with the International Phonetic Alphabet and the extended version for disordered speech (IPA, Citation2015a, Citation2015b) were distributed in paper form and links to the IPA website were available from the PUMA website. For the test of scale rating, six different samples from speakers with different degrees or amounts of nasality symptoms were used. A four-point ordinal scale, whereby 0 = normal resonance/no deviance and 3 = severe, was used for assessment of the four variables: hypernasality, hyponasality, audible nasal air leakage (ANA), and reduced pressure on consonants (RPC).

Figure 1. Material on the PUMA website (in Swedish) for the pre- and post-tests for phonetic transcription of target consonants. The International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA) and Extended IPA are available as charts at https://r12a.github.io/pickers/ipa/, as is the web tool, Character Picker.

Training

The students were instructed to begin the training on the PUMA cleft palate website by listening to reference audio files, providing examples of different types and degrees of speech deviance related to cleft palate. Thereafter, they were recommended to perform phonetic transcriptions of target consonants in a single word test from a video clip, and to compare the transcriptions with expert consensus. Finally, ordinal scale rating of hypernasality, hyponasality, ANA, and RPC, in five audio samples, was recommended and also comparison with expert consensus.

Procedure

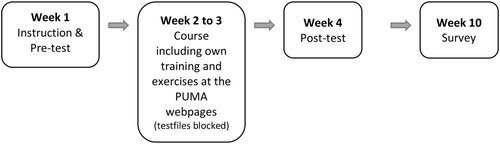

The main study was carried out during autumn (2016), when a relevant course or course modules (speech disorders related to cleft palate) were running on the two SLP programmes. The procedure was first carried out at Karolinska Institutet and then at Lund University. Each course leader received documents with instructions well in advance and was contacted for further information and clarification if needed. The courses at these universities were running for two and three weeks, respectively, according to the regular course structure, and included lectures, seminars, and laboratory work. A pre-test was carried out at the beginning of the course (). The test was 30–45 minutes in length and was performed by each student, individually, during a group session. The students were not allowed to converse during the test. The course leader was available in the room to provide clarification if needed. In the following weeks of the courses, the test audio files were blocked on the PUMA website. During the course, specific speech features related to cleft palate were presented. Training in perceptual assessment was carried out according to instructions within relevant course activities and in students’ free time. Neither the number of training sessions nor the amounts of time given for the training were specified. The students could decide to perform the training individually or together. One video clip with expert consensus was suggested for training phonetic transcription and a second was available for further training. Reference audio files (n = 19) with different types and degrees of deviance related to cleft palate and another four audio samples with expert consensus for scale rating training were available on the website. The test procedure was repeated after the training, i.e., at the end of the course ().

Analysis

The change in skills was measured in terms of agreement between students’ assessments and expert consensus before and after training. The McNemar test was used to assess accuracy in phonetic transcription and detection of consonant errors and the Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used to analyse effects pertaining to ratings of speech deviances related to cleft palate before and after scale rating training on the deviances. The significance level was set to p < 0.05 throughout.

Evaluation of Usage and Student Opinion

Streaming length of each audio and video clip was calculated separately for each student group from automatic time-logs during the training period. Individual logging was not possible but was estimated as mean per student from the group mean. Shortly after the course, a survey was sent out to the students regarding their use of the different parts of the PUMA website as well as their opinion on strengths and weaknesses of the website, examples, and exercises.

Expansion

Organization of the expansion was carried out by working groups of clinical SLPs, led by SLP researchers, and formed in the three sub-areas of neuromotor speech disorders in adults, voice disorders, and swallowing disorders. Within these three sub-areas, patient data were collected according to established clinical standards for assessment and analysis in the three sub-areas. The aim was to collect typical examples of motor speech disorders, voice disorders and swallowing disorders, respectively. Documentation included audio and/or video recordings and expert consensus analyses or individual expert analyses using standard clinical assessment protocols for each disorder. Two experts provided individual assessments of motor speech disorders using the Swedish dysarthria test (Hartelius, Citation2015). Five experts participated in the consensus assessment of voice disorders, whereby the samples were first rated individually by the experts using the Stockholm Voice Evaluation Approach (SVEA; Hammarberg, Citation2000). This was followed by a consensus discussion during which outlier ratings were discussed.

Six experts participated in the consensus assessment of swallowing disorders from the video recordings of fiberoptic endoscopic evaluations of swallowing (FEES) of patients with neurological swallowing disorders. Inefficient and unsafe swallowing, overall degree of dysphagia, and oral intake recommendations were rated using standardized scales (Groher & Crary, Citation2016). Next, three groups of two SLPs performed a consensus assessment. The consensus ratings were followed by a discussion of factors in the video clips that may have affected the ratings.

Ethical Considerations

The PUMA website has the highest level of security using RapidSSL-certificate and time-restricted passwords. Written informed consent was provided by all participants regarding the use of audio and video recordings in education. The streaming is encrypted and files cannot be saved on personal computers. The website is registered according to the Personal Data Act/General Data Protection Regulations.

Results

Training

Transcription

The whole student group showed mean activity of 16.5 hours of training per student (KI-group: mean of 15 hours per student; LU-group: mean of 18 hours per student) on the available samples for phonetic transcription on the PUMA website. Only the streaming activity per group was measured due to the group log-in set-up.

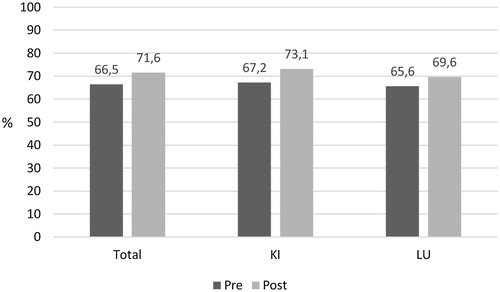

For the whole group, a significantly higher number of answers were in agreement with the expert transcriptions after the training compared to the answers before the training (McNemar test: p = 0.021) (). The difference was also statistically significant in the KI-group (p = 0.024), whereas the difference in the LU-group was not statistically significant (p = 0.332).

Rating

For the whole student group, a mean of 8.5 hours training per student on the available samples for rating of nasality variables was noted (KI-group: mean of 5 hours per student; LU-group: mean of 12 hours per student).

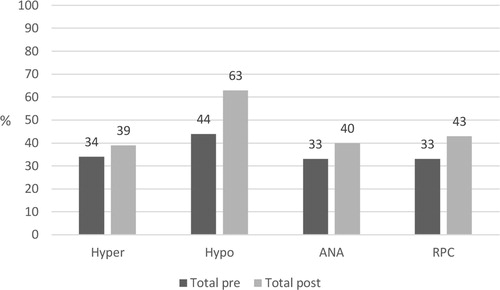

For the whole group, a significantly higher number of answers were in agreement with the expert ratings after the training compared to the answers before training for the variables hyponasality and reduced pressure on consonants (Wilcoxon signed-rank test, ; see also ).

Figure 5. Percentage agreement with expert consensus before and after training for the whole group (n = 45) regarding the variables hypernasality (Hyper), hyponasality (Hypo), audible nasal air leakage (ANA), and reduced pressure on consonants (RPC).

Table 1. Result of test of differences (Wilcoxon signed-rank test) in student group performance compared to expert consensus, pre- and post-test training of ordinal scale rating of nasality variables.

The differences in number of answers in agreement in the separate student groups were also tested for the nasality variables and revealed a statistically significant difference in the KI-group for hyponasality and reduced pressure consonants and a trend for hypernasality (). No statistically significant differences were found for the nasality variables in the LU-group ().

Students’ Opinion

Of all students, 57.8% responded to the questionnaire. All respondents considered their computer skills to be good enough for this purpose. They visited the PUMA website a mean number of 5.3 times (SD: 2.9). Almost all respondents had used the website for cases training and for analysis. The other domains, that is, information on how to perform standardized documentation regarding, for example, ages, speech material and recording, velopharyngeal function (VPF), cleft palate teams (CLP-Team), and a self-test with short questions and answers, had been used by approximately half of the respondents.

Written comments from the students concerned positive thoughts about practical training and time to practise. The opportunities for practical training and practising in one’s own time were mentioned most often. The website was found to be accessible, clear, well-organized, and easy to use according to some students, whereas others found it somewhat difficult to find information and described it as possibly a bit messy. The students appreciated the audio and video clips, although some also observed that the sound quality could have been better. Students noted in particular that the website was educational and contained useful information and material. The negative comments were related to some problems with latency and bugs.

Expansion

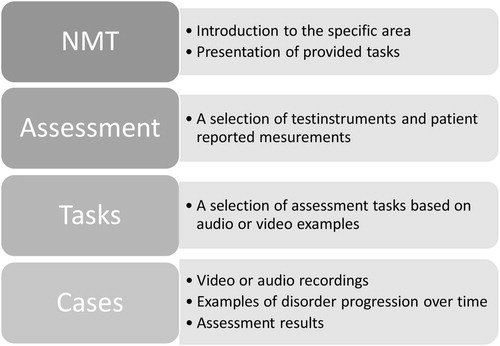

Sub-areas were structured under three headings: Assessment, Tasks, and Patient Cases (). The results of the assessments in the different sub-areas are used as reference values.

Figure 6. Overview of organization for the sub-areas. Here, neuromotor speech disorders (NMT) is used as an example.

In the neuromotor speech disorders (NMT) sub-area, audio and video clips of individuals with motor speech disorders of various etiology are provided. A clinical protocol for the perceptual assessment of structure, function, and activity plus a self-report questionnaire are also provided. Examples of different types of dysarthria due to various neurological conditions at one point in time are used as a basis for the exercises given under the heading Tasks. The two other sub-areas are constructed in a similar manner. Audio files are provided for the perceptual assessment of voice disorders in the voice disorders sub-area, including recordings before and after therapy. Results of the perceptual assessments are presented as figures, with consensus ratings of each perceptual parameter for each patient. In the dysphagia sub-area, the results of the perceptual consensus ratings of each parameter regarding inefficient and unsafe swallowing, overall degree of dysphagia, and oral intake recommendations for different patients are provided.

Discussion

A tool for e-learning of perceptual assessment in speech–language pathology was presented, as well as an initial evaluation of the results of e-learning exercises for auditory perceptual assessment training. The results showed improved performance regarding phonetic transcription, as well as assessment of different aspects of nasality, i.e., hyper- and hyponasality and reduced pressure on consonants. In research, as well as in clinical work, speech parameters related to nasality are considered particularly difficult to assess reliably (Lohmander & Olsson, Citation2004; Sell, Citation2005). Indeed, Watterson, Lewis, Allord, Sulprizio, and O’Neill (Citation2007) claim that, of all perceptual dimensions used to distinguish normal from abnormal speech, the most difficult to judge reliably is hypernasality.

Training has been shown to improve reliability (Lee, Whitehill, & Ciocca, Citation2009) and the present study indicates that a significant effect of training could be experienced during undergraduate education. The students may develop a routine for continuous training and the web-based material allows for recurrent calibration activity in order to perform reliable speech assessments. Multimedia, referring to the presence of visual and auditory material used to support learners’ new knowledge or skills (Issa et al., Citation2013), has a special capacity – interactivity – and allows one to proceed at one’s own pace (Arulsamy, Citation2012). In the current project, the students highlighted in particular the opportunities for practical training and to practise in their own time.

Interestingly, the number of training hours was not the crucial factor for improvement in the present study, as the somewhat higher number of training hours at one university did not result in a significant improvement. Unfortunately, log-on activity was not measured per se, only the streaming activity for the group. This had to do with password administration at that time, which was connected to a group log-in. Thus, it was not possible to use a measure of individual activity based on log-in time in this study. However, one can speculate on whether the number of semesters of completed SLP training may be additionally important. The student group with the highest number of training hours participated during an earlier programme semester (the third) and were not as academically prepared as the other student group, who participated during their fifth semester. The PUMA website, in line with constructivism learning theory, allows for flexible knowledge construction based on students’ previous experience (Hung & Nichani, Citation2001). Indeed, a number of factors are significant in terms of individual results or benefits accruing from use of e-learning tools, as concluded by Voutilainen, Saaranen, and Sormunen (Citation2017). Based on their findings from a systematic review and meta-analysis, the authors stated that, “the effect of e-learning is, most likely, affected by many, probably confounding, factors which vary between different learning methods, subjects, and outcomes” (p. 102).

Appropriate assessment tasks should be used to provide students with opportunities to demonstrate understanding of the specific problems involved (Jimaa, Citation2011). Through the actual patient cases and analyses of speech, the website provided the students with realistic problems requiring consideration and understanding of associated speech variables. These might have suited the students in the fifth semester better than the students in the third. Nevertheless, the cases and analyses were particularly highlighted in the survey by both student groups as valuable for e-learning of perceptual speech assessment. A result of the facilitating effect of multimedia is that difficult processes, such as perceptual assessment of significant speech features, may become easier. Simultaneously, the cognitive load increases as a result of the necessary instructions (Starbek, Starcic Erjavec, & Peklaj, Citation2010). Therefore, the organization and presentation of the material is important in terms of helping students maintain a low enough cognitive load to allow them to concentrate and thereby promote successful learning (DiGiacinto, Citation2007). The deliberately limited material on the PUMA cleft palate website is used for multiple purposes and thereby easily managed. Repetitive presentation is facilitated by the streaming function, even though students reported some problems with latency and a few bugs.

The tool for e-learning, with standardized procedures for perceptual assessment together with reference examples, was found to be well-suited to expansion to other areas within SLP. Using the same platform structure, the policy regarding deliberately limited material was applied for the new sub-areas as well. Further development regards quality of the material and will include both high quality recordings and reliable assessment from standardized procedures, rather than more material. This limitation in amount of material is assumed to help students to maintain a low enough cognitive load to allow them to focus on the assessment task (Starbek et al., Citation2010). Furthermore, a new layout and improved design of the material and instructions have been implemented and are expected to facilitate students’ cognitive learning processes (Issa et al., Citation2011). When comparing e-learning to conventional learning, Voutilainen et al. (Citation2017) found a risk of performance bias. The authors also pointed to the difference between assessing e-learning interventions aimed at improving knowledge versus those aimed at improving specific skills. In the present study, the focus was on students acquiring specific perceptual skills.

Unfortunately, the questionnaire received a mere 58% response rate. In general, the comments received from students were positive; however, there were also a few negative comments and it is unclear how the students who did not respond experienced use of the e-learning tool. Although response rate to the questionnaire was rather low, important comments and suggestions on the organization of the material and quality of the audio and video clips were received, which will be taken into account in the further development of the website, which will also include technical issues such as reduced lagging and bugs. The clinical- and researchbased content of the PUMA website was developed by SLPs in the relevant sub-areas and national usage is expected to promote the implementation of knowledge and skills of and consensus between new SLPs.

Thus, use of the PUMA website for continuous training throughout students’ education will ensure that assessment skills are developed and strengthened, extending into post-graduate clinical practice. Standardized procedures for assessing speech, language, and communication are essential for SLP clinical practice as well as in research and evidence-based practice, and these assessment skills need to be updated and calibrated continuously (Dollaghan, Citation2007). In addition, the website provides an opportunity to evaluate the reliability of groups and individual assessors for professional SLPs who need to develop their perceptual assessment skills. It also provides research-based learning by involving participants in the process of determining and improving reliability.

The PUMA website project has proven useful for the implementation of a standardized method for perceptual speech assessment (Lohmander, Lundeborg, & Persson, Citation2017). This is of utmost value for reliable collaboration in clinical and research projects. Processes for documentation and analysis of treatment and learning activities can be maintained, as well as the necessary ongoing training of perceptual assessment for optimal reliability. A corresponding international website, CLISPI (CLeft palate International SPeech Issues), offers the same possibilities for international collaboration. Also, recommendations for cross-linguistic data collection are included, as analysis of speech disorders is language dependent. Elaboration and expansion of CLISPI – CLinical International SPeech Issues – is currently being considered in a similar manner to that applied to the PUMA website.

In conclusion, despite the short duration of the project, including training of speech assessment, the results showed that e-learning may improve students’ skills in relation to auditory perceptual assessment through phonetic transcription and scale rating of speech deviances related to cleft palate. However, the programme stage of students also seemed to influence results. The students experienced the e-learning tool as useful in their learning process but this finding needs to be interpreted with caution due to the low response rate to the questionnaire. They also made suggestions for improvement, which were taken into account in the design of the expansion of the website. The project is expected to ensure that standardized procedures for documentation and perceptual analysis are promoted in clinical education and practice in SLP. Finally, the project facilitates coordination of education within the specific sub-areas and promotes collaboration in research.

Acknowledgements

We extend our appreciation to SLP Hanna Wahlsö for help with administration of the pilot study; SLP Katarina Holm for help with analysis; clinical SLPs for help with expansion material; Niels Agerskov for administration of the website, test audio files, and the questionnaire; and Karin Söderholm for help with administration of expansion issues.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arkorful, V., & Abaidoo, N. (2015). The role of e-learning, advantages and disadvantages of its adopation in higher education. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 12, 29–42.

- Arulsamy, S. (2012). Multimedia in medical education. Journal of Medical Science, 1, 7–11.

- DiGiacinto, D. (2007). Using multimedia effectively in teaching learning process. Journal of Allied Health, 36, 176–179.

- Dollaghan, C. A. (2007). The handbook for evidence-based practice in communication disorders. Baltimore: Paul H. Brookes Publ.

- Eadie, T. L., & Kapsner-Smith, M. (2011). The effect of listener experience and anchors on judgments of dysphonia. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 54, 430–447. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2010/09-0205)

- Granqvist, S. (2003). The visual sort and rate method for perceptual evaluation in listening tests. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 28, 109–116. doi: 10.1080/14015430310015255

- Groher, M. E., & Crary, M. A. (2016). Dysphagia: Clinical management in adults and children (2nd ed.). St. Louis, MO: Elsevier.

- Hammarberg, B. (2000). Voice research and clinical needs. Folia Phoniatrica et Logopaedica, 52, 93–102. doi: 10.1159/000021517

- Hartelius, L. (2015). Dysartri – bedömning och intervention (eng. Dysarthria – assessment and intervention) [in Swedish]. Lund: Studentlitteratur.

- Howard, S. J., & Heselwood, B. C. (2002). Learning and teaching phonetic transcription for clinical purposes. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 16, 371–401. doi: 10.1080/02699200210135893

- Hung, D., & Nichani, M. (2001). Constructivism and e-learning: Balancing between the individual and social levels of cognition. Educational Technology, 41(2), 40–44.

- IPA. (2015a). extIPA Symbols for Disordered Speech [Internet]. International Phonetic Association. Retrived from https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/sites/default/files/extIPA_2016.pdf

- IPA. (2015b). The International Phonetic Alphabet [Internet]. International Phonetic Association. Retrived from https://www.internationalphoneticassociation.org/content/full-ipa-chart

- Issa, N., Mayer, R. E., Schuller, M., Wang, E., Shapiro, M. B., & DaRosa, D. A. (2013). Teaching for understanding in medical classrooms using multimedia design principles. Medical Education, 47, 388–396. doi: 10.1111/medu.12127

- Issa, N., Schuller, M., Santacaterina, S., Shapiro, M., Wang, E., Mayer, R. E., & DaRosa, D. A. (2011). Applying multimedia design principles enhances learning in medical education. Medical Education, 45, 818–826. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.03988.x

- Iwarsson, J., & Reinholt Petersen, N. (2012). Effects of consensus training on the reliability of auditory perceptual ratings of voice quality. Journal of Voice, 26, 304–312. doi: 10.1016/j.jvoice.2011.06.003

- Jimaa, S. (2011). The impact of assessment on students learning. Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences, 28, 718–721. doi: 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.133

- Kahn, B. (2005). Managing e-learning strategies: Design, delivery, implementation and evaluation. Hershey, PA: idea group Inc.

- Kent, R. D. (1996). Hearing and believing: Some limits to the auditory-perceptual assessment of speech and voice disorders. American Journal of Speech–Language Pathology, 5, 7–23. doi: 10.1044/1058-0360.0503.07

- Keuning, K. H. D., Wieneke, G. H., & Dejonckere, P. H. (1999). The intrajudge reliability of the perceptual rating of cleft palate speech before and after pharyngeal flap surgery: The effect of judges and speech samples. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 36, 328–333. doi: 10.1597/1545-1569_1999_036_0328_tirotp_2.3.co_2

- Klintö, K., & Lohmander, A. (2017). Does the recording medium influence phonetic transcription of cleft palate speech? International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 52, 440–449. doi: 10.1111/1460-6984.12282

- Klintö, K., Salameh, E.-K., Svensson, H., & Lohmander, A. (2011). The impact of speech material on speech judgement in children with and without cleft palate. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 46, 348–360.

- Kreiman, J., Gerratt, B. R., Kempster, G. B., Erman, A., & Berke, G. S. (1993). Perceptual evaluation of voice quality: Review, tutorial, and a framework for future research. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 36, 21–40. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3601.21

- Kreiman, J., Gerratt, B. R., Precoda, K., & Berke, G. S. (1992). Individual differences in voice quality perception. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 35, 512–520. doi: 10.1044/jshr.3503.512

- Lee, A., Brown, S., & Gibbon, F. E. (2008). Effect of listeners’ linguistic background on perceptual judgements of hypernasality. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 43, 487–498. doi: 10.1080/13682820801890400

- Lee, A., Whitehill, T. L., & Ciocca, V. (2009). Effect of listener training on perceptual judgement of hypernasality. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 23, 319–334. doi: 10.1080/02699200802688596

- Lohmander, A., Eliasson, H., & Larsson, P. (2010, March). Take charge of learning - using a web-based interactive multimedia application for training assessment of speech and communication. Paper presented at the Karolinska Institutet’s 12th Educational Congress, Stockholm, Sweden.

- Lohmander, A., Ergic, Z., Lillvik, M., Henningsson, G., Hutters, B., & Wigforss, E. (2000, August). PUMP-CLEFT PALATE; a web-based multimedial application for education and description of speech production produced by individuals with cleft palate. Poster session presented at the 8th Meeting: International Clinical Phonetics and Linguistics, Edinburgh, UK.

- Lohmander, A., Lundeborg, I., & Persson, C. (2017). SVANTE – the Swedish Articulation and Nasality Test – normative data and a minimum standard set for cross-linguistic comparison. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 31, 137–154. doi: 10.1080/02699206.2016.1205666

- Lohmander, A., & Olsson, M. (2004). Methodology for perceptual assessment of speech in patients with cleft palate: A critical review of the literature. Cleft Palate-Craniofacial Journal, 41, 64–70. doi: 10.1597/02-136

- McAllister, A. (2003). Voice disorders in children with oral motor dysfunction: Perceptual evaluation pre and post oral motor therapy. Logopedics Phoniatrics Vocology, 28, 117–125. doi: 10.1080/4302002000014

- McAllister, A., Aanstoot, J., Hammarström, I. L., Samuelsson, C., Johannesson, E., Sandström, K., & Berglind, U. (2014). Learning in the tutorial group: A balance between individual freedom and institutional control. Clinical Linguistics & Phonetics, 28, 47–59. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2013.809148

- McAllister, R., Flege, J. E., & Piske, T. (2002). The influence of L1 on the acquisition of Swedish quantity by native speakers of Spanish, English and Estonian. Journal of Phonetics, 30, 229–258. doi: 10.1006/jpho.2002.0174

- Perkins, M. R., & Howard, S. J. (1995). Principles of clinical linguistics. In M. R. Perkins & S. J. Howard (Eds.), Case studies in clinical linguistics (pp. 10–38). London: Whurr.

- Phillips, J. A. (2015). Replacing traditional live lectures with online learning modules: Effetcts on learning and students perceptions. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 7, 738–744. doi: 10.1016/j.cptl.2015.08.009

- Sell, D. (2005). Issues in perceptual speech analysis in cleft palate and related disorders: A review. International Journal of Language and Communication Disorders, 40, 103–121. doi: 10.1080/13682820400016522

- Shrivastav, R., Sapienza, C. M., & Nandur, V. (2005). Application of psychometric therory to the measurement of voice quality using rating scales. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 48, 323–335. doi: 10.1044/1092-4388(2005/022)

- Shuster, L. I. (1993). Interpretation of speech science measures. Clinics in Communication Disorders, 3, 26–35.

- Starbek, P., Starcic Erjavec, M., & Peklaj, C. (2010). Teaching genetics with multimedia results in better acquisition of knowledge and improvement in comprehension. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 26, 214–224. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00344.x

- Voutilainen, A., Saaranen, T., & Sormunen, M. (2017). Conventional vs. E-learning in nursing education: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Nurse Education Today, 50, 97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2016.12.020

- Watterson, T., Lewis, K., Allord, M., Sulprizio, S., & O’Neill, P. (2007). Effect of vowel type on reliability of nasality ratings. Journal of Communication Disorders, 40, 503–512. doi: 10.1016/j.jcomdis.2007.02.002