ABSTRACT

The aim of the study is to investigate trends in academic L1 Swedish and L2 English reading comprehension ability among Swedish adolescents, with a specific focus on 18- to 20-year-olds in the period 2012–2018. The material consists of results from regular tests and anchor tests in the spring administrations of the Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test (SweSAT) 2012–2018, allowing an analysis of trends in reading comprehension ability among a subset of the adolescent population. The results show two highly significant but opposite trends, with a substantial decrease in academic Swedish reading comprehension and an equally substantial increase in academic English reading comprehension. The results are discussed from the perspective of a changing media landscape, and related to results of the PISA-studies as well as to research on extramural English in Swedish society.

1. Introduction

The level of L1 reading comprehension ability among Swedish adolescents has long been a much debated topic among teachers, researchers and the general public in Sweden, where a commonly expressed view has been that reading and writing skills are steadily decreasing (cf. the summary in Nilsson Citation2013). The large-scale PISA-studies, focused on 15-year-old students in a large number of countries, have provided mixed results with regard to Swedish students, with a negative trend in L1 reading comprehension up until 2012 followed by a positive trend between 2012 and 2018 (OECD Citation2019). Turning to L2 (foreign language) English, a changing media landscape has led to an increase in extramural English-related activities among many young people in Sweden, where research has found connections between such activities and for example English vocabulary knowledge. Increased English input in activities such as digital gaming and increasing possibilities of social interaction in on-line environments have been suggested to have positive effects on English language learning (Sundqvist & Wikström Citation2015, Sylvén Citation2019, Sundqvist Citation2019, Warnby Citation2021, etc.). However, to what extent there are any longitudinal trends with regard to L1 or L2 reading comprehension ability among Swedish adolescents has not yet been empirically determined. The aim of the present study is to investigate such trends in academic L1 Swedish and L2 English reading comprehension ability more systematically, with a specific focus on 18- to 20-year-olds during the period 2012–2018.

The material in the study consists of results from regular tests and anchor tests in the spring administrations of the Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test (CitationSweSAT), 2012–2018. Although the anchor items in this test are regularly used to calibrate results from different test administrations, no systematic large-scale investigation of longitudinal trends in the data has been carried out to date. With a specific focus on adolescent test-takers, the present study aims to investigate whether such trends exist by carrying out a detailed statistical analysis of the different subsections of the verbal part of the SweSAT. More specifically, the study attempts to answer the following research questions:

RQ1: What trends (if any) exist between 2012 and 2018 in the average level of the test-takers’ academic English and Swedish reading comprehension ability?

RQ2: What trends (if any) exist between 2012 and 2018 in the relation between test-takers’ L1 (Swedish) and L2 (English) reading comprehension ability?

2. Theoretical Foundation

Since one of the aims of this study concerns the relationship between L1 and L2 reading comprehension, the selected theoretical foundation needs to cover several different kinds of reading processes. Thus, the study is based on the component skills approach to reading (Carr & Levy Citation1990), as discussed for example in Grabe (Citation2009) and Koda (Citation2005). In this theoretical approach, a distinction is made between lower-order and higher-order reading processes, where the latter in particular are often regarded as largely transferable between languages. Lower-order processes refer to reading processes such as word recognition, vocabulary knowledge, syntactic parsing and semantic-proposition encoding, which are often related to linguistic features of individual languages. In turn, higher-order processes involve for example a text model of comprehension and a situation model of interpretation, where the former refers to the ability to make inferences and to integrate information from different parts of a text, while the latter refers to the ability to relate the text to background information and to understand the text in the context of broader perspectives. Although the reality of higher- and lower-order reading comprehension skills is generally assumed in the literature (cf. Koda Citation2005, Grabe Citation2009, Khalifa & Weir Citation2009, etc), these processes are often difficult to separate from each other in empirical studies due to their highly integrated nature (cf. for example the construction-integration model, Kintsch Citation1998).

With regard to the relationship between reading comprehension ability in L1 and L2, it is generally acknowledged that learning several languages helps learners to develop competences across languages (the interdependence hypothesis, Cummins Citation1979). Grabe (Citation2009:123) lists a number of universal aspects of cognitive and linguistic processing, which in principle have the potential to allow transfer of reading comprehension ability between one’s L1 and other languages. These abilities involve (1) carrying out phonological processing while reading, (2) using syntactic information to determine text meaning and text comprehension, (3) setting goals and engaging in reading strategies, (4) applying some level of metacognitive awareness to text comprehension, (5) engaging a capacity-limited working-memory system, (6) drawing on background knowledge to interpret text meaning, and (7) carrying out very rapid pattern recognition and automatic processing skills. Koda (Citation2005:140) argues that “many non-linguistic skills developed in L1, such as distinguishing thematic and peripheral information and identifying underlying semantic relationships among propositions, should facilitate L2 coherence building, because these skills are not language specific – once developed in one language, they can, in principle, be applied to another”. Presumably, this kind of transfer goes in both directions, so that L1 and L2 reading comprehension skills may facilitate each other, both in terms of higher-order processing of text and in terms of increased motivation for learning languages (Brevik & Doetjes, Citation2020). On the other hand, as pointed out in Grabe (Citation2009:144), such transfer effects occur less frequently with vocabulary knowledge and morphosyntactic knowledge, although this depends on the nature of the relationship between vocabulary forms in the two languages.

The separation between language-specific lower-level skills and more general higher-order skills allows us to analyze relationships in reading comprehension ability across languages. As will be clear below, this type of theoretical perspective is needed in order to understand and interpret trends in Swedish (L1) and English (L2) reading comprehension ability among Swedish adolescents.

3. Previous Research

Arguably, the most detailed and systematic investigations of young people’s reading comprehension ability are carried out within the PISA framework, normally taking place every third year, with a special focus on reading comprehension every ninth year (OECD, Citation2019). These tests are used both to compare reading comprehension ability of 15-year-olds in a large number of countries around the world, and to investigate longitudinal trends within each of these countries.

With regard to the Swedish results, PISA 2018 indicated a statistically significant improvement in comparison with 2012 (OECD Citation2019). However, it should be pointed out that the main improvement (17 score points) occurred between 2012 and 2015 and coincided with a shift from paper-based to computer-based testing. This complicates the interpretation of this trend, since it is possible that Swedish 15-year-olds were better adapted to the computer-based than to the paper-based format. The results of the PISA-study in 2018 indicated that the average level of L1 reading comprehension ability among Swedish 15-year-olds had increased by 6 additional score points between 2015 and 2018, although this improvement was not statistically significant (OECD, Citation2019:121, 336). The PISA-report of the tests carried out in 2018 states the following concerning the Swedish results (OECD, Citation2019: 336):

After a rapid decline until 2012, mean reading, mathematics and science performance in Sweden recovered fully or almost fully between 2012 and 2018, returning to a level similar to that observed in the early PISA assessments. / … / Sweden’s improvement in mean performance since PISA 2012 was observed over a period of rapid increase in the proportion of immigrant students, who tended to score below non-immigrant students. It could be estimated that, if the student population in 2009 had had the same demographic profile as the population in 2018, the average score in reading would have been nine points lower than what was observed that year / … / and the recent trends would have been even more positive.

While the PISA material provides very useful empirical data for trends regarding L1 reading comprehension ability among young adolescents, large-scale studies focused on older adolescents are more scarce. While several studies of the SweSAT material have previously been carried out, few have been directly aimed at analyzing long-term trends in the different sections of the verbal part of the test. A study by Gustafsson & Håkansson (Citation2017) investigated the development of vocabulary knowledge during the period 2000–2011 based on the vocabulary section in the SweSAT, by comparing the results of a number of selected vocabulary items in pretest versions and subsequent regular tests. Their conclusion is that there was a general decrease in vocabulary knowledge among younger test-takers throughout this period. In particular, the decrease concerned words of Scandinavian or German origin, while the development with regard to vocabulary related to Romance or English word forms was often positive (2017: 126). However, a weakness of their study is that the analysis does not take into account the huge increase in the number of young SweSAT test-takers between 2008 and 2011 (due to changes in the Swedish application system), possibly leading to a shifting demographic pattern during the investigated period. For this reason, it is difficult to know to what extent the negative trend was caused by an increase in the proportion of weaker students among the test-takers.

While these studies focused on trends in reading comprehension ability, other studies have focused on changes in reading habits among young people in Sweden. A recent study by Vinterek et al (Citation2020), for example, investigated trends in school-related reading among young people between 2007 and 2017. The result was a negative trend with regard to the number of whole pages of school-related texts (in books, on the Internet, or from other sources) students read each day in both of the investigated age groups (grades 4–6 and grades 7–9). This result is also in line with the results of PISA and other studies with regard to general reading habits, where a clear negative trend is seen between 2012 and 2018 (Statens Medieråd Citation2019, Skolverket Citation2019).

Turning to L2 English language ability among young people in Sweden, studies such as the First European Survey of Language Competences (European Commission Citation2012) have shown that Swedish 15-year-olds appear to be among the top performers in Europe in reading comprehension as well as in listening comprehension and writing. Some factors that have been suggested as explanations for these strong results are related to the status of English in Sweden, linguistic similarities between the two languages and the rich amount of extramural English input in Sweden (Skolverket Citation2012, Sundqvist Citation2009). While extramural English activities have been common in Swedish society for a long time, the changing media landscape in the last ten years has led to an increase in many types of internet-based activities (Internetstiftelsen Citation2015). For example, in the category of 13- to 15-year-olds, those who spent time watching Youtube videos on a daily basis increased from 54% in 2013 to 69% two years later. During this period there were also certain gender-related patterns, where on-line gaming and watching Youtube was more common among males while social networking was more common among females.

Although it has not yet been established to what extent various types of extramural activities have improved English language skills in the adolescent population more generally, research has shown a connection between the use of English-related on-line activities and English language ability (Sylvén & Sundqvist Citation2012, Sundqvist & Wikström Citation2015, Sundqvist & Sylvén Citation2016, Sylvén Citation2019, Sundqvist Citation2019, Warnby Citation2021). However, it should be noted that many of these activities are associated with oral rather than written language, as in the case of young adolescents’ frequent engagement with Youtube videos (Internetstiftelsen Citation2015). Thus, to what extent there has been an increase in English on-line reading activities is less clear. In particular, this concerns exposure to longer and more academic texts, which are the focus in the present study. In other words, although there is reasonable evidence of a connection between extramural English activities and English language learning, there is little direct evidence of a general increase in academic English reading comprehension skills among Swedish adolescents.

4. Method and Material

For the purposes of this study, there are three characteristics of the material in particular that need to be described; these are (1) the test formats and the construct of the test, (2) the specific population of SweSAT test-takers, and (3) the possibility of linking tests from different years with each other.

4.1. SweSAT Test Formats

The Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test (CitationSweSAT) is a test that partly decides admission to higher education in Sweden, administered twice a year and taken by roughly 100,000 Swedish people annually. The majority of the test-takers are under 25 years of age, but the test is taken by people of all ages. The test consists of eight sections, four belonging to a “verbal” and four belonging to a “quantitative” part, where the verbal part consists of 60 items focused on Swedish and 20 items focused on English.

For the present purposes, the relevant sections are those in the 80 item verbal part of the SweSAT, labeled in the test as “ORD” (WORD/Swedish vocabulary), “LÄS” (READ/Swedish reading comprehension), “MEK” (SEC/Swedish sentence completion) and “ELF” (ERC/English reading comprehension), each consisting of 20 items. The theory of validity and reliability of the SweSAT reading comprehension tests are based on assessment theories as described in Bachman (Citation1990) and Alderson (Citation2000), and the sections are based on traditional multiple choice formats similar to those described in for example Khalifa & Weir (Citation2009). However, while the SweSAT tests are theoretically aligned with component skills approaches, the general construct associated with these tests is considered to be verbal reasoning in a wider sense (Stage & Ögren, Citation2010), and separate items are not specifically aimed at measuring different reading comprehension subskills. The anchor test items used for trend analysis in the present study are Swedish vocabulary items, Swedish sentence completion items, Swedish content question items based on 300–1000 word texts, and English content question items based on 100–800 word texts.

With regard to the English section of the test, Stage & Ögren (Citation2004:7) state that “the ERC items are aimed towards identifying essential information in the text rather than isolated details and towards central arguments and conclusions”, and that “each ERC-test contains authentic texts within a broad spectrum of subjects, arts/social science as well as technology/natural science”. The following is a short-text item exemplifying the type of format and style used for content questions in the ERC section of the SweSAT:

Cleopatra (SweSAT, ERC, 2014B)

More than two millennia after it took place, the story of Cleopatra has lost none of its grip on the world’s imagination. It has inspired great plays, novels, poems, movies, works of art, musical compositions both serious and silly, and of course histories and biographies. Yet, for all this rich documentation and interpretation, it remains at least as much legend and mystery as historical record, which has allowed everyone who tells it to play his or her own variations on the many themes it embraces.

Which of the following statements is most in line with the text?

A Cleopatra has been characterized as a beautiful and imaginative woman.

B The artistic works about Cleopatra keep close to historical facts.

C Cleopatra appears in many cultural genres due to her intriguing life. [Correct]

D Recent documentaries on Cleopatra tend to focus on unknown aspects of her life.

Ever since these four sections were introduced in 2011, the correlations between them have been consistently strong. For example, corrected for attenuation, the correlations between the English and Swedish reading comprehension sections (ERC and READ) between 2010 and 2015 were consistently around r = .85 (Löwenadler, Citation2019), which could be taken as evidence of an underlying ability associated with verbal reasoning (cf. Stage & Ögren, Citation2010). Still, in light of the theoretical assumptions of the component skills approach, it can be assumed that the tests in the verbal section of the SweSAT are associated with slightly different constructs, at least with regard to the English and the Swedish sections (cf. Löwenadler Citation2019 for an analysis of the constructs within the ERC-section). However, although the three Swedish sections involve somewhat different formats, the correlations between them are strong, suggesting that they all measure a common underlying verbal ability. Since statistical analyses of the Swedish anchor items show no significantly different trends if the three sections are measured separately, these are merged into a single more reliable set for the purposes of this study (see 4.3).

4.2. SweSAT Test-Takers

First of all, it is important to point out that the population of SweSAT test-takers is not a random sample of the population of Swedish adolescents, but mainly includes those aiming for higher education. For example, between 2012 and 2018, 10–20% of the students leaving compulsory school were not eligible to apply to high school education (Skolverket Citation2018), and this category of students is clearly underrepresented in the SweSAT material. Background data on the SweSAT group show that at the time of administration, around 90% of the test-takers in the youngest age category (<20 years old) studied or had previously studied at a university preparatory high school program (Science/Technology, Social Science/Humanities or Arts, see ). This can be compared with the pattern in the total population of high school students during the same period, where the share of students in university preparatory programs was around 60% (Skolverket Citation2021).

Table 1. Test-taker background data.

An informative study carried out by Graetz & Karimi (Citation2019) provides some additional background data concerning the SweSAT test-takers, in particular with regard to gender differences in SweSAT scores and school grades. Using administrative data on the Swedish population, Graetz and Karimi show that, on average, females outperform males on both compulsory school and high school GPAs by about a third of a standard deviation, while they underperform by a third of a standard deviation relative to males in the SweSAT. Graetz and Karimi also show that this pattern is consistent across the different cohorts in their data. Summarizing their findings, they state the following with regard to the differences between the general population of Swedish adolescents and the SweSAT group, as measured by school grades and various large-scale tests on cognitive and non-cognitive traits (2019:16):

Females outperform males on cumulative compulsory school GPA and on high school GPA, by about a third of a standard deviation in both cases. At the same time females under-perform by about a third of a standard deviation in the Swedish SAT. Our results suggest that differences in the endowments of non-cognitive traits – in particular, motivation and effort – account for a sizeable portion of the female advantage in school performance. In contrast, motivation has no predictive power for SAT scores. Turning to cognitive skills, we account for 40 percent of the male advantage in SAT scores by observing gender gaps in the endowments of inductive, spatial, and verbal skills among SAT takers. The latter can, however, be fully explained by differential self-selection into taking the SAT across the genders.

Thus, in comparison with the general population of high school students in Sweden, there is an overrepresentation in the SweSAT of male test-takers with strong cognitive skills, due to the fact that this category of students is especially likely to take the test. In turn, this is argued to be the main reason why males tend to perform better than females in the SweSAT, while females tend to perform better in school (as measured by school grades).

However, even though the group of SweSAT test-takers is not fully representative of the Swedish adolescent population as a whole, its composition appears to be stable across the period. For example, a background analysis of the whole set of 18- to 20-year-old test-takers in each SweSAT test 2012–2018 shows no significant trends with regard to the number of test-takers, male/female distribution, share of test-takers with previous education in a foreign country (essentially corresponding to first generation immigrants)Footnote1, and proportion of test-takers in different high school programsprograms (). The only cohorts where the proportions appear to deviate somewhat from the general pattern are those in 2012 and 2013, where the number of test-takers studying social science is slightly lower and the number of test-takers in the “Other” category is slightly higher than later in the period. However, these proportions essentially mirror the pattern of the high school population as a whole, which in turn can be explained by changes in the program structure introduced at that time. Thus, statistical data (Skolverket Citation2021) show that while the total number of high school students in a science or technology program was stable across the period, the number of students in a social science program was lower than average at the beginning of the period, roughly corresponding to the pattern among the SweSAT test-takers (). Furthermore, the total number of students in vocational programs dropped by more than 25 percent between 2013 and 2014, which is consistent with the smaller proportions in the “Other” category from 2014 and onwards. In other words, the composition of the sample does not show any irregularities that cannot be explained by corresponding patterns in the total high school population.

Note that the study focuses on the spring tests each year, since these tests are likely to be the most consistent in terms of test-taker characteristics. For example, the spring tests are those involving the largest group of test-takers, and they are the most important tests for students that wish to apply to higher education, taking place at the end of their high school studies. The larger group of test-takers also provides more reliable data from the anchor tests (described below), making the spring tests more suitable for trend analyses. All in all, in light of the background data discussed above and without obvious external reasons for expecting changes in the demographic profile of the SweSAT group, the compared samples will be assumed here to represent a consistent subset of Swedish 18- to 20-year-olds for the purposes of this study.

4.3. Test Equating and General Procedure

The anchor items (also known as common items or link items) in the SweSAT are part of a section taken by a subset of test-takers across the different age groups, in the youngest group around 800–1600 people. The role of these items is to allow comparisons between the results of different cohorts of test-takers. The particular version of the anchor test analyzed in the present study was used between 2012 and 2018, thereby setting a natural starting- and end-point for the analysis. Just like the regular test, the anchor test includes all of the four sections (WORD, READ, SEC, ERC) with ten items in each section. However, due to some changes in the anchor test in 2016, there are only six identical items in the READ section through the whole investigated period. Thus, the potential set of anchor items consists of 36 items in total. An important property of the anchor test is that it forms a separate section in the SweSAT, which means that the items always occur in the same order, minimizing the effect of unwanted variance related to different item positions. Also, due to the design of the SweSAT, the test-takers are unaware of which items belong to the regular test and which belong to the pretests/anchor tests, thereby providing reliable anchor test data.

The analyses were carried out using Item Response Theory (1PL, one-parameter logistic item response model), SPSS version 24 with the SPIRIT macro, version 1.0 (DiTrapani et al Citation2018). Fit statistics were checked and found to be satisfactory for the usefulness of the model (Wright & Linacre Citation1994), with mean square infit and outfit values between 0.8 and 1.1 for 34 out of 36 potential anchor items in the verbal section of the test. Analyses of differential item functioning (DIF) showed that with the exception of the two misfitting items (in the WORD section), all anchor items were within the 0.5 logit deviation from the expected value, suggested as a reasonable cut-off point by Wu et al (2016:212-215). Since the two misfitting anchor items also showed evidence of DIF, they were removed, resulting in a final set of 34 items. These were divided into two separate sets, with a 10 item set focused on English reading comprehension (ERC) and a merged 24 item set consisting of the three tests measuring Swedish verbal ability (WORD, READ and SEC). This merged set will be referred to as the SRC (Swedish reading comprehension) in the rest of this paper. The point-biserial correlations of the items within these sets were all above 0.30 and all except five items showed values above 0.40. The suitability of the 1PL item response model is demonstrated by the small spread among the infit and outfit values, which also supports the general claim of unidimensionality in the English and Swedish sections of the SweSAT (Stage & Ögren, Citation2010).

The equating procedure was carried out using a variant of the shift method (Wu et al, Citation2016:234). In this method, the means of the anchor item difficulty values in the separate calibrations are aligned, while the specific difficulty parameters of the individual items to some degree are allowed to vary. First, the mean theta-values for the anchor groups in the different tests were estimated by IRT analysis. Second, these means were shifted by equating the means of the item difficulty values in the anchor tests, in line with the principles of the selected method. Third, following the same procedure but using the regular test (with scores from the whole population of test-takers, including the anchor group), the mean theta-values of the anchor groups were compared with the mean theta-values of random samples of 1,300 test-takers from the whole population each year. By carrying out this additional procedure, the mean ability scores reflect the whole population of test-takers each year rather than the anchor groups only.Footnote2 Finally, the estimated mean theta-values of the whole population of test-takers each year were analyzed by pairwise comparison as well as simple linear regression. For easier interpretation, the theta-values were transformed into a scale similar to that used in PISA, with a baseline value at year 2012 set to 500 and an average pooled SD of test-taker ability set to 100. These transformed ability values will be referred to as “score points” in the rest of this paper.

5. Results

Using the procedure described above, the estimated ability scores of the whole population of test-takers in 2012 were directly compared with those in 2018. In addition to the standard errors associated with the sampling procedure, it is also appropriate to take into account the linking errors introduced by the equating process (Wu et al Citation2016, OECD Citation2019).Footnote3 This concerns both in the linking of the anchor groups in different cohorts (referred to here as external linking error) and in the linking of the anchor groups and the whole group of test-takers within each cohort (internal linking error). Note that since the baseline value of “500” assigned to the 2012 test is fixed (and therefore free of error), the confidence intervals of the 2018 mean ability scores refer to the difference from the baseline value. Thus, since the total error of the 2012 mean scores is set to 0, the total measurement error in the mean ability scores in 2018 also includes all sampling errors and linking errors transferred from the tests in 2012 (indicated by arrows in and ).

Table 2. English reading comprehension (2012 versus 2018).

Table 3. Swedish reading comprehension (2012 versus 2018).

As indicated by the confidence intervals, this comparison shows highly significant (p < .001) and quite large differences between the two cohorts, both with regard to English and to Swedish reading comprehension. However, even more striking is that these differences indicate completely opposite trends. Thus, in this comparison, the mean ability among adolescent test-takers increased by around 38 score points in English reading comprehension, while the mean ability in Swedish reading comprehension in the same period decreased by around 46 score points.

In order to assess the stability of these patterns and determine to what extent the differences between 2012 and 2018 form part of more consistent trends, all the tests between 2012 and 2018 were compared using simple linear regression, with time as the independent variable and ability score as the dependent variable. and show the mean scores, standard deviations and standard errors after the equating process.

Table 4. Trend in English reading comprehension ability (2012-2018).

Table 5. Trend in Swedish reading comprehension ability (2012-2018).

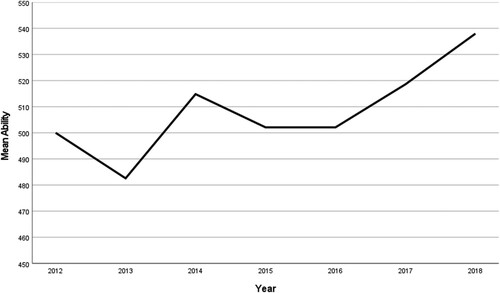

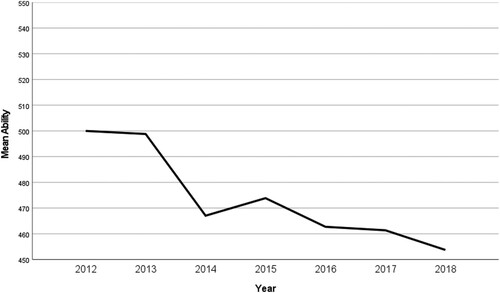

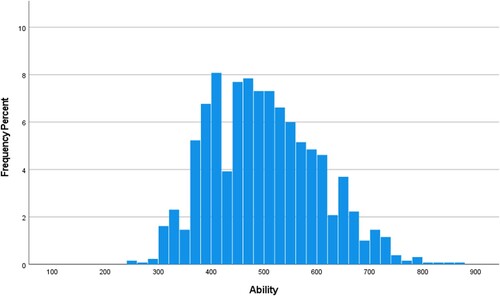

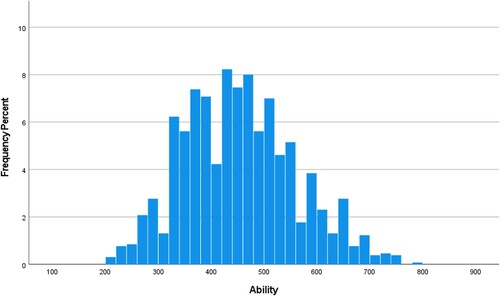

In and these trends are represented graphically, with the first graph showing the trend with regard to English reading comprehension ability and the second showing the trend with regard to Swedish reading comprehension ability. The graphs show seemingly strong but directly opposite trends in the two languages, and simple linear regressions confirm this picture (see ). These regressions were carried out using the IRT-estimated ability scores of each individual in the 1300 test-taker samples from all the Swedish and English reading comprehension tests throughout the period (9100 testtakers in total), and as above the regression B-values are expressed in terms of score points.

Table 6. Trends in English and Swedish reading comprehension ability (2012-2018).

The results presented in thus confirm that the result of the direct comparison between the cohorts in 2012 and 2018 is basically representative of two general trends across the period, and that these trends are both highly significant and quite strong. The regression B-value using the information from the English reading comprehension tests confirms that there was a yearly mean increase in English reading comprehension ability by around 6 score points, or an improvement of around 37 score points across the whole period 2012–2018. With the average standard deviation set to 100, this therefore represents more than a third of a standard deviation over six years, which must be regarded as quite a substantial improvement. By contrast, the trend in Swedish reading comprehension ability shows a yearly decrease by around 8 score points, or 47 score points across the whole period. In other words, the direct comparison between the tests in 2012 and 2018, and the regression based on all the tests between 2012 and 2018 give essentially the same result.

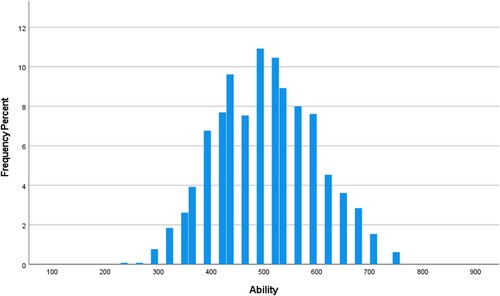

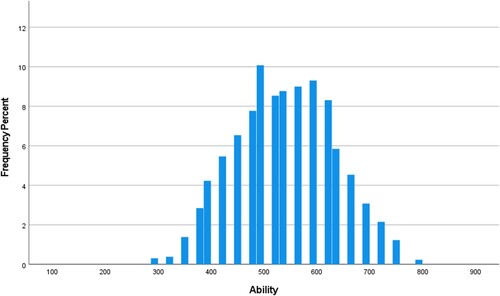

It should also be pointed out that the positive trend in English and the negative trend in Swedish are found across the whole distribution of test-takers, as seen for example in the randomly varying standard deviations in and . Similarly, disregarding the observed differences in mean ability, graphic comparisons between the test-taker distributions in 2012 and 2018 show no obvious patterns that point to a widening or narrowing of the ability gap within each cohort of SweSAT test-takers ().

Finally, it is informative to consider the separate trends associated with male and female test-takers. As previously noted in for example Graetz & Karimi (Citation2019), male test-takers tend to outperform female test-takers in the SweSAT, which is also true in the sections studied here.Footnote4 However, since this difference to a great extent can be explained by different patterns of self-selection between the genders, a more interesting comparison is to investigate the relative change in each gender category throughout the period (). In Swedish reading comprehension, there is no difference in development between the male and the female groups, both showing a similar decrease in ability of almost half a standard deviation. In English reading comprehension, both male and female test-takers show a substantial improvement during this period, and although the improvement in the male group is estimated to be 8 score points higher than in the female group, the difference is not statistically significant.

Table 7. Male and female changes in mean ability scores (2012 versus 2018).

In light of the study of the SweSAT population (Graetz & Karimi Citation2019), this not only shows that the negative trend in Swedish reading comprehension and the positive trend in English reading comprehension are not significantly different between the genders, but also indicates that the result is not specifically associated with any of the typical characteristics of these particular groups of test-takers, such as average level of cognitive ability. In other words, even though the male and female subsets of SweSAT test-takers are not completely representative of the population of Swedish male and female adolescents as a whole, the trends with regard to Swedish and English reading comprehension ability appear to be similar across the board.

6. Discussion

The two research questions posed at the beginning of the paper concerned trends between 2012 and 2018 in Swedish adolescents’ academic English and Swedish reading comprehension ability, and the analyses show some quite striking patterns. The focus of the discussion in this section will be the distinct trends in English and Swedish as well as differences between the trends in Swedish reading comprehension seen in the SweSAT and in PISA.

Starting with the positive trend in English reading comprehension ability, a well-developed general English language ability among specific groups of young Swedish students has previously been noted, suggesting a connection between exposure to extramural English and language ability. Sundqvist (Citation2019), for example, studies the relation between digital gameplay and vocabulary knowledge among Swedish teenagers, finding indications of a connection between the two (see also Sylvén & Sundqvist Citation2012, Sundqvist & Wikström Citation2015, Sundqvist & Sylvén Citation2016, Sylvén Citation2019). However, the extent to which English reading comprehension ability has increased among Swedish adolescents has not been empirically determined. Specifically, a large part of Swedish adolescents’ extramural English activities can be associated either with informal communication in on-line social networks or with listening activities in the form of music or Youtube videos (Internetstiftelsen Citation2015, Sylvén Citation2019). While the increased use of and exposure to English in such settings can be expected to have an effect on informal listening and speaking skills, a connection to increased academic English reading comprehension ability is less obvious.

However, there are studies indicating that academic vocabulary and multi-word units may be more prevalent than often thought in for example gaming-related on-line activities (Sundqvist Citation2019, Warnby Citation2021, Sylvén & Löwenadler, Citationin press). Furthermore, strong correlations between listening comprehension and reading comprehension are generally found in studies of second language learning (cf. the meta study in Jeon & Yamashita Citation2014)Footnote5, and the close connection between the two modes even forms the basis of certain theories of reading, such as the simple view of reading (cf. Grabe Citation2009 for discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of this theory). While Grabe (Citation2009:98) points out that this view of reading may generally be more relevant in L1 than in L2, since L2 readers “seldom achieve word-recognition fluency levels evident among good L1 readers”, it does not seem unreasonable that Swedish adolescents have a sufficient command of English for strong transfer effects to occur between listening and reading. In this light, it seems quite plausible that the increasing ability in academic reading is a direct consequence of increasing extramural English listening activities, although other factors may obviously be involved as well.

Turning to the negative trend in Swedish reading comprehension ability, note that the PISA-studies indicated a 17 point improvement among Swedish 15-year-olds between 2012–2015 and a slight (although non-significant) 6 point increase between 2015 and 2018. Since the SweSAT test-takers investigated here are 3–5 years older than those studied in PISA, certain similarities could be expected to show up in PISA 2012/SweSAT 2015 and PISA 2015/SweSAT 2018. Yet, no similar improvement could be seen among Swedish 18- to 20-year-olds in the present study. Instead, what was found here was a strong negative trend across this period, with substantially weaker results in 2018 than in 2012 (almost half a standard deviation or 47 score points). While studies of reading habits point to a general decrease in time spent on reading among young Swedish speakers (Vinterek et al Citation2020, Statens Medieråd Citation2019, Skolverket Citation2019) and claims have sometimes been made in the public debate of decreasing reading and writing ability among students at Swedish universities (see discussion in Nilsson Citation2013), this has not been clearly supported by reading comprehension studies. However, as in the study by Gustafsson & Håkansson (Citation2017) where the results appeared to show a negative trend with regard to Swedish vocabulary knowledge in 2000–2011, the present study shows a negative trend in Swedish academic reading comprehension ability between 2012 and 2018.

A simplistic conclusion based on these results could be that the negative trend in Swedish reading comprehension is a direct consequence of the increasing exposure to English outside school among Swedish adolescents. However, previous large scale studies investigating school contexts where part of the education is carried out in a second language have shown that such language mixing has no general negative effect on the first language; in fact, the opposite often seems to be true, so that L2 language learning facilitates L1 language learning. Thus, as described in section 2, there is substantial evidence that learning several languages helps learners to develop competences across the languages, for example by increased cognitive development, transfer effects related to higher-order processing and increased motivation for language learning (Cummins Citation1979, Koda Citation2005, Grabe Citation2009, Navarro-Pablo & Gándara Citation2020, Brevik & Doetjes Citation2020). While such transfer of competences concerns higher-order skills in particular, some lower-order skills may also be transferred, for example if the languages are historically related or share loanwords with each other.

Nevertheless, it is possible that Swedish adolescents’ knowledge of low-frequency vocabulary has been affected by a relative increase in their exposure to English within more academic domains. Thus, from the perspective of the component skills approach described in section 2 (Grabe Citation2009), what might have changed is their relative ability with regard to language-specific lower-level processes in the two languages, while the trend with regard to higher-order reading comprehension skills may have remained stable throughout this period. In other words, with regard to universal aspects of cognitive and linguistic processing, such as distinguishing between thematic and peripheral information or identifying underlying semantic relationships among propositions (Koda Citation2005), the results found in this study are entirely consistent with a constant mean reading comprehension ability throughout the period. As for the difference between the trend presented in this study and the trend seen in the PISA-studies, this could then be explained if the negative trend in reading comprehension in the SweSAT mainly concerns lower-level skills associated with Swedish academic vocabulary and phrases, which is not as prominent in the PISA-test designed for 15-year-old students.

It is perfectly possible, therefore, that the general Swedish reading comprehension ability of Swedish adolescents is indeed positively affected by increasing English reading comprehension ability, but that the lack of exposure to academic language in Swedish has had a negative effect on their knowledge of Swedish-specific academic vocabulary and multi-word units. Due to the integrated nature of higher-order and lower-order skills in reading (Kintsch Citation1998), the result is a negative trend specifically with regard to academic reading comprehension ability in Swedish. In fact, an improvement among the SweSAT test-takers with regard to the knowledge of Swedish words with English cognates was observed in the study by Gustafsson and Håkansson (Citation2017) while a negative trend was found for infrequent words of native and Germanic origin, which is consistent with the above interpretation. From a pedagogical perspective, the results presented here could therefore be taken as evidence that the negative trend in Swedish reading comprehension ability during the period has more to do with a decrease in knowledge of Swedish academic vocabulary and multi-word units than in the ability to process higher-order features of academic texts. Thus, it could be argued that specifically lower-level features of Swedish academic language should receive relatively more attention in Swedish high school education.

Finally, although this study is based on tests with high reliability and a very large number of test-takers, there are some limitations with regard to the interpretation of the results. First of all, as discussed in section 4.2, while the population of SweSAT test-takers is assumed here to have remained stable across the period in terms of its composition, it is not entirely representative of the Swedish adolescent population as a whole. This means that there may be trends among other subsets of adolescents that are not captured in this study. Second, while the trend analysis is based on a reasonably large number of anchor items, it still represents a restricted set of items and texts. This means that different anchor items or texts could have yielded slightly different results. However, due to the highly significant and very strong trends seen with regard to both Swedish and English reading comprehension ability, it seems unlikely that different anchor items would have changed the result in any significant way. Third, although the study is based on a very large collection of quantitative data, it is observational rather than experimental in nature. This means that the material and method used here do not allow us to draw any direct conclusions with regard to the causes of these trends, although such causes may be hypothesized based on previous studies. Thus, determining more specifically what lies behind these trends is arguably an important task for future research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Note that although the number of first generation immigrants in Sweden increased during the investigated period (OECD Citation2019), these students apparently did not take the CitationSweSAT in any significant numbers. For this reason, the results presented here can be regarded as reflecting trends concerning students that have attended school in Sweden from the start of their education.

2 This procedure is necessary since those who take the anchor test come from different parts of Sweden each year.

3 As in the recent PISA-analyses, this linking error is computed as the standard deviation of the differences between the linked tests in item difficulty values divided by the square root of the number of items. The linking error thus reflects the amount of variation in item parameters across two tests (Wu et al Citation2016:240).

4 In 2018, for example, male test-takers outperformed female test-takers by roughly 28 score points in the ERC and 27 score points in the SRC material.

5 As shown in data from Swedish adolescents taking the Swedish National Tests in English, the correlation between listening comprehension and reading comprehension is in many cases just as high as between different reading comprehension tests (Löwenadler & Hoff Citation2018).

References

- Alderson, J. (2000). Assessing reading. Cambridge University Press.

- Bachman, L. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford University Press.

- Brevik, L. M., & Doetjes, G. (2020). Tospråklig opplæring på fagenes premisser. Rapport fra evaluering av tospråklig opplæring i skolen (ETOS-projektet). Institutt for lærerutdanning og skoleforskning, Det utdanninsvitenskaplige fakultet, universitetet i Oslo.

- Carr, T., & Levy, B. (eds.). (1990). Reading and its development: Component skills approaches. Academic Press.

- Cummins, J. (1979). Linguistic interdependence and the educational development of bilingual children. Review of Educational Research, 49(2), 222–251. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543049002222

- DiTrapani, J., Rockwood, N. J., & Jeon, M. (2018). Explanatory IRT analysis using the SPIRIT macro in SPSS. The Quantitative Methods for Psychology, 14(2), 81–98. https://doi.org/10.20982/tqmp.14.2.p081

- European Commission. (2012). First European survey of language competences. Final report. Publications Office of the European Union.

- Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language. Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Graetz, G., & Karimi, A. (2019). Explaining gender gap variation across assessment forms. IFAU Working Paper 2019/8. Swedish ministry of employment, Uppsala.

- Gustafsson, A., & Håkansson, D. (2017). Ord på prov: En studie av ordförståelse i högskoleprovet. Lundastudier i nordisk språkvetenskap, Nr. A75. Språk- och litteraturcentrum, Lunds universitet.

- Internetstiftelsen. (2015). Eleverna och internet 2015. www.svenskarnaochinternet.se.

- Jeon, E. H., & Yamashita, J. (2014). L2 reading comprehension and its correlates: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 64(1), 160–212. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12034

- Khalifa, H., & Weir, C. (2009). Examining reading. Research and practice in assessing second language reading. Cambridge University Press.

- Kintsch, W. (1998). Comprehension: A paradigm for cognition. CUP.

- Koda, K. (2005). Insights into second language reading. A cross-linguistic approach. Cambridge University Press.

- Löwenadler, J. (2019). Patterns of variation in the interplay of language ability and general reading comprehension ability in L2 reading. Language Testing, 36(3), 369–390. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265532219826379

- Löwenadler, J., & Hoff, I. (2018). Usage i kursprovet för engelska 7. In Att bedöma språklig kompetens. Rapporter från projektet nationella prov i främmande språk (pp. 119–137). Göteborgs universitet.

- Navarro-Pablo, M., & Gándara, Y. L. (2020). The effects of CLIL on L1 competence development in monolingual contexts. The Language Learning Journal, 48(1), 18–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/09571736.2019.1656764

- Nilsson, A. (2013). Protestering! Så skriver studenterna. Språktidningen, 2013(6), https://spraktidningen.se/artiklar/2013/08/sa-skriver-studenterna.

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 results (volume 1): what students know and Can Do. OECD Publishing.

- Skolverket. (2012). Internationella språkstudien 2011. Elevernas kunskaper i engelska och spanska. Rapport 375. Fritzes.

- Skolverket. (2018). Fler elever behöriga till gymnasiet. Retrieved 4 October, 2021. https://www.skolverket.se/om-oss/press/pressmeddelanden/pressmeddelanden/2018-09-27-fler-elever-behoriga-till-gymnasiet.

- Skolverket. (2019). PISA 2018. 15-åringars kunskaper i läsförståelse, matematik och naturvetenskap.

- Skolverket. (2021). Statistik om förskola, skola och vuxenutbildning: Elever på program redovisade efter typ av huvudman och årskurs. Retrieved 4 October, 2021. https://www.skolverket.se/skolutveckling/statistik/sok-statistik-om-forskola-skola-och-vuxenutbildning?sok=SokC&verkform=Gymnasieskolan&omrade=Skolor%20och%20elever&lasar=2017%2F18&run=1.

- Stage, C., & Ögren, G. (2004). The Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test (SweSAT). developments, results and experiences. Umeå universitet.

- Stage, C., & Ögren, G. (2010). Ett nytt högskoleprov. Bakgrund och konsekvenser. Umeå universitet.

- Statens Medieråd. (2019). Ungar och medier 2019.

- Sundqvist, P. (2009). Extramural English matters: Out-of-school English and its impact on Swedish ninth graders’ oral proficiency and vocabulary. Karlstad University.

- Sundqvist, P. (2019). Commercial-off-the-shelf games in the digital wild and L2 learner vocabulary. Language Learning & Technology, 23, 87–113.

- Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2014). Language-related computer use: Focus on young L2 English learners in Sweden. ReCALL, 26(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0958344013000232

- Sundqvist, P., & Sylvén, L. K. (2016). Extramural English in teaching and learning: From theory and research to practice. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Sundqvist, P., & Wikström, P. (2015). Out-of-school digital gameplay and in-school L2 English vocabulary outcomes. System, 51, 65–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.04.001

- SweSAT. The Swedish Scholastic Assessment Test. English Reading Comprehension, Swedish Reading Comprehension, Sentence Completion, WORD. Universitets och högskolerådet.

- Sylvén, L. K. (2019). Extramural English. In L. K. Sylvén (Ed.), Investigating content and language integrated learning. Insights from Swedish high schools (pp. 152–169). Multilingual Matters.

- Sylvén, L. K., & Löwenadler, J. (in press). Let’s play videos and L2 academic vocabulary. In New directions in digital game-based language learning. Routledge.

- Sylvén, L. K., & Sundqvist, P. (2012). Gaming as extramural English L2 learning and L2 proficiency among young learners. ReCALL, 24(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095834401200016X

- Vinterek, M., Winberg, M., Tegmark, M., Alatalo, T., & Liberg, C. (2020). The decrease of school related reading in Swedish compulsory school. Trends between 2007 and 2017. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research.

- Warnby, M. (2021). Receptive academic vocabulary knowledge and extramural English involvement – is there a correlation? International Journal of Applied Linguistics.

- Wright, B. D., & Linacre, M. (1994). Reasonable mean-square fit values. Rasch Measurement Transactions, 8, 370.

- Wu, M., Tam, H.P. & Jen, T-H. (2016). Educational measurement for applied researchers. Theory into practice. Springer.