ABSTRACT

Internal and external factors influence teachers’ daily assessment decisions. The purposes of teachers’ assessments are crucial, as these purposes guide the assessment process. Still, little is known about teachers’ assessment purposes. The aim of this study is to identify and describe the different purposes of assessments that Civics teachers describe. Thirteen Civics teachers in Swedish upper secondary school were interviewed about their assessment practices. A thematic analysis generated four main themes about teachers’ purposes: enacting policy, improving learning, pulling for students and handling administration. There are tensions between different purposes, and teachers need to balance these in their assessment decisions and when validating. Specific Civics subject matter also influences purposes and tensions. This study contributes to the understanding of the influence of internal and external factors on teachers’ assessment practices in Civics, and to the understanding of the complexity of validity with multiple purposes in the school context.

Introduction

In this article, we investigate qualitatively different purposes that Civics teachers express when talking about their assessment practices in upper secondary school in Sweden. This area of research needs further development, since only a few studies have empirically explored the complexity of purposes behind teachers’ daily assessment decisions (McMillan, Citation2013). Some authors discuss assessment purposes from a theoretical perspective (Brown, Citation2004; Newton, Citation2007), but empirical studies about teachers’ assessment purposes are rare. This is also true in Sweden and as teachers’ decision making is a social and cultural experience, assessment practices need to be investigated in different national contexts (Klenowski, Citation2013). Further, previous studies indicate that the subject influences teachers’ assessment and grading practices (Biberman-Shalev et al., Citation2011; McMillan, Citation2001; Prøitz, Citation2013). Still, knowledge about how the subject, especially in Civics, affects assessments, including purposes, is limited (Torrez & Claunch-Lebsack, Citation2014). Drawing on data from interviews about Swedish Civics teachers’ assessment practices, this study contributes knowledge about how assessment purposes and the subject matter might influence teachers’ assessment decision making.

Purposes can relate to assessments on an aggregated or an individual level, depending on which stakeholders will use the results (Newton, Citation2007). The aggregated level uses assessments outside the classroom, for example to evaluate schools or entire educational systems. Several studies discuss purposes at an aggregated level, including high-stakes tests, but few explore the purposes of classroom assessments (Forsberg & Lindberg, Citation2010). This article focuses only on teachers’ assessment purposes.

Many studies relate to formative and summative purposes (Hirsh & Lindberg, Citation2015), for example discussing the distinction between formative and summative. Newton (Citation2007) defines summative assessment as summing up student knowledge, which can be used in different ways, such as to support learning or for monitoring. He therefore argues that there is no summative purpose, but different purposes depending on the intended use of the summative information. Newton also argues that grading is not a purpose, but only a summative evaluation that can be used for different purposes. Other authors, though, define summative assessment as a purpose, like Leong (Citation2014), who found that teachers’ intentions of enacting a particular assessment practice can be either formative-oriented, focusing on supporting student learning, or summative-oriented, emphasising grades and scores. In this article, summative assessment refers to teachers’ activities intended to justify certain grades. But like Newton (Citation2017), we do not limit purposes to summative and formative, teachers might have other purposes, which are interesting to explore.

In their daily work, teachers make assessments to judge if students have reached the learning goals, to give feedback to promote learning, to obtain evidence for grading etc. (Newton, Citation2007; Stiggins, Citation2001). Ideally, depending on the purposes, teachers choose accurate measurement methods, decide on the criteria for evaluation, and how to use the results (McMillan, Citation2003). Assessments also need to be valid according to their purposes (Bonner, Citation2013; Newton, Citation2017). The rationales for validity are different depending on the purposes. Summative assessments place rather high demands on validity (e.g. alignment), while formative assessments have rationales other than validity. But with multiple purposes, validity in classroom assessments is complicated (Newton, Citation2017).

The aim of this study is to identify and describe the different purposes of assessments that Civics teachers in Swedish upper secondary school ascribe. The study will contribute to the understanding of the influence of internal and external factors on teachers’ assessment decision making in Civics, to how the subject matter influences assessment practices, and to the ongoing discussions about validity.

Purposes in the assessment process

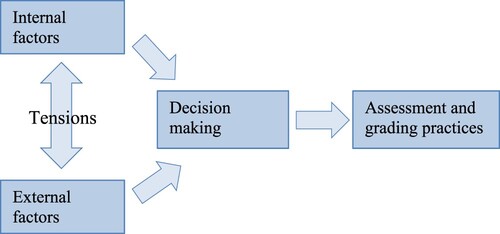

Assessment processes involve a lot of decisions: about what content and which skills to measure, with which methods, how to evaluate these skills, and how the results will be used. The purposes guide these decisions. McMillan (Citation2003) uses a model with two major sources influencing the decision making (). One source, teacher beliefs and values, lies within the teacher and thus relates to internal factors (see also Liu et al., Citation2021): philosophy of teaching/learning, pulling for students’ success, accommodating individual differences, enhancing student engagement and motivation, and promoting student understanding. The other source lies external to the teacher, with different demands and conditions that need to be considered: policies about grading, parents’ expectations, high-stakes tests and teacher evaluation. McMillan (Citation2003) found that these sources were in constant tension, and teachers need to balance internal and external factors in their decisions about assessments. There are tensions between summative and formative assessment, for example giving grades and forwarding feedback (Brookhart, Citation2009; Gioka, Citation2009; Leong, Citation2014). Further, interpreting policy, planning and using varying forms of assessments within time constraints are found challenging (Lumadi, Citation2013). Internal and external factors generate different purposes, which motivate the decisions that all together form an assessment and grading practice, and it is interesting to study the purposes of teachers’ assessments in relation to internal and external factors.

Figure 1. A model of teachers’ classroom assessment decision making (modified from McMillan, Citation2003).

The assessment process is influenced by teachers’ conceptions about assessment (Brown, Citation2004; Harris & Brown, Citation2009). Brown describes four theoretically generated conceptions about purposes of assessment: to improve learning, make students accountable for learning, accountability for schools, and that assessment should be rejected as irrelevant and negative. These are, however, purposes at a system level, not a classroom level. In an Australian interview study, Harris and Brown (Citation2009) found seven categories of teacher conceptions about purposes of assessments: (1) compliance, (2) external reporting, (3) reporting to parents, (4) extrinsically motivating students, (5) facilitating group instruction, (6) teacher use for individual learning, and (7) joint teacher and student use for individualising learning. These purposes correspond to three of their four conceptions, all but student accountability. They also describe tensions between purposes, mainly between school accountability and student needs, but also between compliance and improvement, which teachers need to handle to fulfil the educational goal of improving learning. They conclude that “teachers see assessment as having a range of diverse purposes aligned with different practices” (p. 379). Different purposes of assessments may also complicate validity.

Validity in assessments

The purposes of assessments are important to validity, as validation is in many ways an evaluation of how fit for purpose the test is (Shepard, Citation2016). The definition of validity has long been debated. A common definition is that validity is about the appropriateness of the inferences and uses (for example to give feedback or grades) that result from assessments (Kane, Citation2016; Messick, Citation1989).

Theories of validity can, however, be problematic in the classroom context, as validity theories and validation methods were developed for large-scale standardised tests (Bonner, Citation2013; Cizek, Citation2009; Kane & Wools, Citation2020). Teachers’ classroom assessments are situated, often complex, tasks testing multiple abilities, and are mostly not needed to be standardised and compared with others. Therefore, validity needs to be adapted to the school contexts. Kane and Wools (Citation2020) suggest that classroom assessments should emphasise a functional perspective on validity, which focuses on the utility of assessment for their purposes, rather than a measurement perspective focusing on accuracy and precision. But still, teachers’ multiple purposes may complicate the validity in the school context.

Multiple assessment purposes need to be accepted, even though they both complement and conflict with each other (Newton, Citation2017). Shepard (Citation2016) argues that tests should be evaluated for each of their purposes. Koch and DeLuca (Citation2012) suggest validation as a narrative case description in which all different purposes, contexts and theoretical constructs need to be identified and then evaluated to judge the degree to which evidence supports them. However, this is probably too time-consuming for teachers. Instead, test designers need to prioritise the purposes and compromise between them (Kane, Citation2016; Newton, Citation2017). The argument-based approach to validity could be useful (Kane, Citation2016), whereby the formulation, and weighting, of the arguments (purposes) determines which evidence is most relevant. “A testing programme would not be held accountable for claims it does not make” (Kane, Citation2016, p. 208).

The school context in Sweden

Upper secondary school, “gymnasium”, in Sweden is optional, though most young people attend (Skolverket, Citation2011). There are two main categories of programmes: higher education preparatory and vocational. Subjects are studied in one or more courses. The first course in some subjects, of which one is Civics, is universal for all programmes. In Civics, students in preparatory programmes study a more extensive course, Civics 1b, than students in vocational programmes, who do half as much in the course Civics 1a1. Course syllabuses have three parts: the aim of the subject, core content (including subject skills), and knowledge requirements for grades. The first Civics courses have a broad content, covering for example democracy, government, international politics, economics, and social policies. This article studies both Civics 1b and 1a1.

The Swedish grading system is criterion-referenced with a scale A-F, where A-E are passing grades and A is the highest (Skolverket, Citation2017). The knowledge requirements are both criteria and standards, as they express a skill or property and then different levels of quality (Sadler, Citation2009). These knowledge requirements are not aims, but required and expected outcomes (Skolverket, Citation2017).

The curriculum reform of 2011 emphasised summative assessments, mainly grading, “despite a strong discourse advocating formative assessment” (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015, p. 1). In Sweden the teacher is responsible for assessing and grading the students, which is rather unique by international standards (Lundahl et al., Citation2017). There are external national tests in other subjects, but not in Civics. An effect of this is that all formal assessments can be seen as high-stakes tests, as students get grades in each course, based on the teachers’ assignments. Recent decades have seen an increase in the administrative burden on teachers, including documentation of assessments (Samuelsson et al., Citation2018).

Assessments in civics

There is extensive literature on how assessments should be done in Civics, but Torrez and Claunch-Lebsack (Citation2014) claim empirical research concerning assessment in Civics is absent. American literature emphasises that as Civics has civic competence goals, instruction and assessment in Civics should be oriented towards inquiry rather than rote memorisation of facts. Civics in Sweden has also been focused on citizenship and characterised by reasoning and critical thinking, ever since it was introduced in 1919 (Englund, Citation1986). Wahlström et al. (Citation2020) found that in the Swedish Civics syllabus, the subject’s character involves not only transmission of citizenship, civics, and reflective inquiry, but also performance-based generic competences. This means Civics is also about generic skills built into the logic of pedagogy and curriculum. They found the generic skills are more emphasised than the subject content. Still, these skills are strong frames “because of the focus of knowledge requirements and the demand on the students to make their knowledge visible for the teacher” (p. 80).

In practice, assessing factual knowledge seems to be common in Civics, and use of performance-based assessments is rare in both the USA and Sweden (Brookhart & Durkin, Citation2003; Curry & Smith, Citation2017; Jansson, Citation2011; Mattson, Citation1989; Odenstad, Citation2011). For example, Jansson (Citation2011) found that in Swedish Civics teachers’ written tests, factual knowledge was most assessed, ranging from 50% to 90% of the items, and Odenstad (Citation2011) describes similar results. The six teachers in Jansson’s (Citation2011) study used their assignments mainly for summative purposes, not formative ones (other purposes were not explored).

The subjects’ characteristics affect teachers’ grading practices and different subjects face different challenges, including the curriculum, when coming to grading (Prøitz, Citation2013). Perceptions of the subject matter influence assessment practices. Biberman-Shalev et al. (Citation2011) found that Hebrew/Arabic and Science teachers have a perception of an open/flexible subject, with weak framing in Bernstein’s (Citation1975) vocabulary, and tend to regard effort more in grading than Maths teachers, who perceive their subject as closed/hierarchical, with strong framing, and give more regard to performance. Civics is also regarded as open/flexible, with weak framing, and McMillan (Citation2001) found in a survey study that Civics teachers focused more on effort, class participation and homework than English and Maths teachers.

Method

Setting, participants and ethical considerations

Since the focus is on teachers’ purposes of assessments, semi-structured interviews were conducted (Bryman, Citation2016). Initially, 108 random Civics teachers in upper secondary schools were contacted and asked for their written assessment assignments in the first Civics courses (1b/1a1). From these, 16 teachers, with a variation between them in assignments used, were asked for interviews and 13 agreed to participate. The teachers also differed in their backgrounds and settings. They comprised 7 men and 6 women, and all but one were of Swedish origin. All were experienced, and graduated as teachers, though one was not educated in Civics but in other subjects. Ten worked in public schools and three in private schools, differing in size and located in both large cities and small towns. The individual interviews were conducted during spring 2019 and lasted between 46 and 106 minutes.

In the semi-structured interviews, the teachers were asked about their assessment practices, including purposes. Broad main questions were asked (e.g. “Tell me about how you do your assessment in the course Civics 1a1/1b?”, “Tell me about how you reason when choosing between different assessment methods”), allowing the teachers to talk freely about their assessment practice. Follow-up questions concerned, for example, factors influencing the choice of methods, relations between content and methods, different kinds of knowledge and methods, the syllabus and assessment, adaptation of assessments, and information and feedback given to students. Specific questions were also asked about the assignments they sent before the interview.

The teachers were informed both in advance and during the interview about the aim of the study, that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time. They were also guaranteed they would be anonymised. Therefore, pseudonyms are used for the interviewees in the excerpts to maintain privacy. This is in accordance with the ethical principles from the Swedish Research Council (Citation2017).

Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The aim is to identify and describe different purposes, and therefore a thematic analysis was performed (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006). In the process, the interviews were listened to, and transcriptions read and re-read to become familiarised with the content. Then initial codes relating to expressions of intentionality were generated, which were made inductively, very close to the empirical data. After that, themes were searched for, and codes were collated into these potential themes. As the aim is to identify qualitatively different purposes, all potential themes and sub-themes were included with no regard to frequency. The themes were reviewed and also compared to theory, mainly the decision-making model (McMillan, Citation2003), to obtain clear definitions and names, until the final four themes, with several sub-themes, emerged. Finally, vivid and compelling extracts were chosen and translated.

Results – teachers’ purposes of assessments

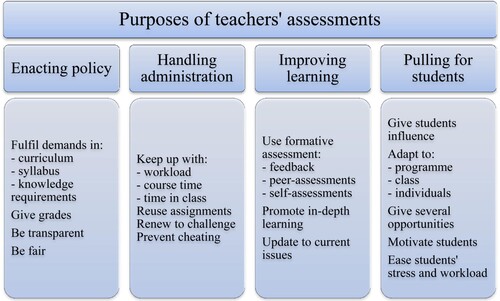

The thematic analysis of the interviews resulted in four main themes for the purposes of teachers’ assessments: enacting policy, improving learning, pulling for students, and handling administration ().

Enacting policy

The theme “enacting policy” is where teachers express the main purpose of assessments being to fulfil requirements in different formal policy documents (external factors), mainly the syllabus and the grades’ knowledge requirements, but also the national curriculum. Almost all teachers mention the importance of policy documents for assessments.

Well, first you do a course plan, then I look at the core content, what the course is about. Then I construct assessment evidence, assignments, which are aligned with core content and parts of the knowledge requirements. (John)

The strong focus on knowledge requirements stated in the curriculum clearly drives teachers to a summative assessment practice. The teachers often refer to the curriculum requiring teachers to give grades at the end of the courses. Teachers need to gather evidence to support grading through different assessments, to have a broad basis or to ensure they are safeguarded in grading. In contrast to Newton (Citation2007), teachers express a purpose to support grading, to justify grades to students and by extension to protect one’s own professional integrity.

Some teachers talk about the importance of recurrent communication about grades, which should not come as a shock. This and the emphasis on the knowledge requirements, are probably the reasons that teachers often talk about clarifying the course goals, and especially the knowledge requirements, to the students. The purpose is to make assessments transparent; the students should know what is being assessed. The knowledge requirements are explained, often several times during a course: at the start of the whole course, at the start of a specific subject area, and/or in connection with specific assessment tasks. Teachers often specify which knowledge requirements are assessed in the specific task, either by printing them in the task description or linking the task to a rubric, mostly digital, but sometimes on paper.

In this summative assessment practice, several teachers also use grades in their feedback to students on individual assignments or even individual task items. Sometimes they use both grades and the formulated knowledge requirements for the grade in their feedback.

I also usually write comments about it, and then, the feedback they get is first these comments I write and then this grade. (Tomas)

Some parts of the Civics syllabus and the curriculum can be problematic. Several teachers state that they do some things because the curriculum demands it, even though they can be troublesome. For example, Alva speaks about a demand that students must show their knowledge in different forms of assessments, both written and oral, a demand found both in the curriculum and in the knowledge requirements in Civics:

But then there will be a problem with it because it is enshrined that it must be both oral and written, so I can’t like not use them, these must be included. (Alva)

I […] have always had a slight issue with the personal finances because this knowledge requirement is so decisive for everything else, a subject area that we only do once and depending on how the student performs there it can be decisive for the grade. (Rebecka)

In summary, an important purpose of assessments, referring to external factors, is that they are done because the formal policy demands them, especially the national curriculum and the subject syllabus. Teachers have to evaluate students’ knowledge progress in regard to the knowledge requirements and they have to give grades. They also need to justify grades to students and parents, who are external stakeholders. Therefore, gathering evidence for grading is an important purpose, and grading is done in correspondence to the knowledge requirements, which are crucial for teachers’ assessment practice. Another purpose is that assessments need to be transparent, and students should know what is measured in each assignment. Fair assessments are also a purpose and teachers want to assess each standard at least twice, though this is difficult for some specific Civics knowledge requirements.

Handling administration

The next theme is a purpose of handling administration. Teachers need to plan and administrate assessments and teachers state that choices between different assessment formats can depend upon how they affect the teacher’s workload. The purpose of choosing certain formats can be to ease administration, like Tomas says:

As always it has to do with teachers’ workload. I could easily say: ‘We’ll do a report on everything, write three pages each!’ But then I will get a great deal of marking to do, and your worktime only extends so far. You also need to live outside your work. (Tomas)

Another purpose is to fit all the assessments within the limited time of the Civics course, as expressed by Hanna:

Now I have Civics 1a1 which has a lot of content, many knowledge requirements […] so due to time I can’t test them twice. (Hanna)

In summary, purposes of handling administration are mostly influenced by conditions like time and schedule, which are external factors. Teachers must handle assessments practically, planning, administering, and evaluating assessments within limited time (Lumadi, Citation2013). Teachers also need to ease administration and reduce their workload. Reusing well-tested assignments facilitates teachers’ work, but they are also renewed with the purpose of making work more challenging. Finally, cheating and plagiarism need to be prevented.

Improving learning

The theme “improving learning” is about teachers expressing the purpose that assessments should promote students’ learning. The teachers talk a lot about formative assessment, and they describe a practice giving formative feedback. For example, when Simon talks about students working on an assessment task, he gives feedback with the purpose of helping students develop their knowledge:

I think this is absolutely the most important part as a teacher, driving the students on in their work, continuing to inspire, but also being formative so they continue to develop. (Simon)

In formative assessment, peer-assessment and self-assessment are important (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009). A few of the interviewed teachers mention that they use peer-assessment and let students evaluate their own work. For example, Simon uses exit tickets as self-assessments with the purpose of improving students’ metacognitive skills and he sometimes lets students evaluate earlier performance before doing new tasks measuring the same abilities.

Teachers also have mastering purposes, wanting students to not just perform when doing the tasks, but to retain their knowledge.

If students know something during a paper-and-pencil test in October and they know nothing about it in April, then I feel I have failed. (Simon)

Civics is about current issues and the Civics teachers have the purpose that students should learn about such topics. Teachers express a need to renew assessments, relating them to current topics. This is mainly about the content of the task items, not the skills to be performed. When Rebecka talks about a task about human rights, she says:

In Civics I think it’s important to look around, like this: ‘what is happening right now when we are in class?’ So, this assignment is very different each year as it is based on a specific topic. (Rebecka)

In summary, a purpose of assessments is improving students’ learning. Policy, an external factor, stipulates that students should learn, but teachers clearly express a wish to promote learning, so this is mainly affected by internal factors. McMillan (Citation2003) also consider “improving learning” an internal factor. The teachers talk widely about formative assessment strategies, mainly in giving feedback. Most teachers tend to use both formative feedback and summative comments, either grades or the knowledge criteria, though combining formative and summative feedback will reduce the effect on learning (Shute, Citation2008). Another purpose is to promote in-depth learning and the teachers have a purpose of preparing for life, for upcoming upper secondary courses, and for higher education. Finally, a specific subject purpose is that students should learn about current issues, as this is central in Civics.

Pulling for students

Another purpose is pulling for students to succeed in assessments. Success can be both that students learn and that they get a passing grade. Therefore, this is considered a separate theme. Teachers use several strategies for this. One is letting students influence assessments with the purpose that students will perform better when they can choose when and how assessments are done, as Samuel express:

And sometimes they make their own choice […] the gain is that they can perform at their best all the time if they may choose. (Samuel)

Another important strategy is adapting assessments with the purpose of helping students to succeed. Teachers make accommodations for the programme, class and individuals. Teachers can use different assessment methods depending on the programme, with the main distinction made between preparatory programmes (studying Civics 1b) and vocational (studying Civics 1a1). Teachers adapt content, choosing topics they think are relevant for different programmes, as they believe it motivates students in doing the assignments. Sometimes teachers adapt the difficulty level, mainly simplifying items for vocational students, as they think they are under-achievers.

Teachers also adapt assessments to the performance level in a class or to their interests, with the purpose of helping students to succeed. Simon says:

I think you constantly need to decide which assignments to use, which assessment format, according to which class you have, […] to how the class works best. (Simon)

Further, assignments are adapted to individuals. As mentioned above, students can sometimes choose assignments at the end of a course to improve their grade. Tasks are also adapted to students with special needs, who can get individual assignments. For example, some students cannot present in front of class and instead can perform in a small group or record their presentation. Teachers make accommodations to help students with difficulties in reading or writing to succeed. For example, Esther says:

First, they write, […], when it is very difficult, I usually say: ‘But write short paragraphs, you don’t need to think about “fancy” wording. Write key points to me and later we’ll talk based on these.’ But others only need more time to finish, and then they get that. (Esther)

Another way of pulling for students to succeed is to give students several opportunities to perform. Esther refers to the specific content knowledge requirements and says:

Well, they are expressed once and then students can supplement that subject area afterwards if they are not satisfied with their result. But we attempt to assess the other topics at least twice and some are assessed more often. (Esther)

Some teachers also say that a purpose of tasks is to motivate, for example, stating that an assignment will be evaluated should encourage students to get something done, as Erik says:

Then you say: ‘but know that I will be assessing this’, even though it won’t be so heavily weighted when I do the grading. But it is a way to get them alert, maybe false advertising, but also a trick to sharpen their attention. (Erik)

Finally, teachers talk about a purpose of decreasing students’ stress and workload, as this will also promote success. Teachers try to spread assignments equally over the course, to give enough time to finish tasks, make students feel comfortable, reuse assignments, and sometimes have students avoid over-elaborate tasks. Sometimes teachers cooperate with teachers in other subjects to decrease the workload.

In summary, teachers’ purpose is to give students the best possible conditions to succeed. Like improving learning, this is mainly influenced by internal factors as this is expressed as the teachers’ wish, although some of these sub-purposes, like adaptations and student influence, are also demanded in policy. McMillan (Citation2003) also consider pulling for students an internal factor. Students are given influence over how and when assessments are done to help them perform better. Assessments are adapted to individuals, the class and the programme to help them succeed. Another purpose is to motivate students to make efforts, which should promote success. In contrast to McMillan (Citation2003), we consider accommodating and motivating as sub-themes to pulling for students, because teachers adapt and motivate with the main purpose of helping students to succeed. Further, teachers give students several occasions to perform and let them supplement tasks to enhance performance. Finally, teachers promote success by easing stress and workload.

Discussion

Teachers make a lot of decisions in the assessment process, they choose content and methods, and they need to adapt to their students’ abilities as well as to formal policy demands and claims on validity. The purposes of their assessments are crucial when they decide which content and methods are most relevant to use (Newton, Citation2017). This study, in line with other studies (Harris & Brown, Citation2009; McMillan, Citation2001), implies that teachers have multiple and diverse purposes for their assessments, which they need to balance. Some of the findings are recognised in previous research, while others are new.

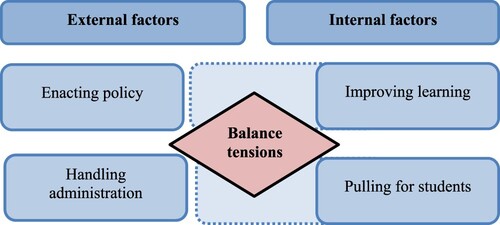

The thematic analysis found four main themes in teachers’ purposes influencing teachers’ decision making in the assessment process. The purposes are related to both internal and external factors (). Enacting policy and handling administration are influenced mainly by external factors. Improving learning and pulling for students are mainly influenced by internal factors as they are wanted by teachers, even though these are also demanded in policy.

In the end teachers need to balance all these different purposes and the tensions between some of them, which is in line with earlier findings (Harris & Brown, Citation2009; McMillan, Citation2001). Like earlier research (Brookhart, Citation2009; Gioka, Citation2009), we found tensions between learning goals and grading, between summative and formative assessments. Giving grades for single tasks often means that students do not read formative feedback (Shute, Citation2008). Thus, there is a tension between the purposes of enacting policy and improving learning. In Sweden, this tension is enhanced by summative grading demands in policy and the strong discourse advocating formative assessment (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015). Further, the teachers have the purpose of pulling for students to succeed and they therefore adapt assignments accordingly. Both writing formative feedback and making adaptations can be time-consuming and teachers must balance these purposes with administrative demands as part of the teacher’s workload (Lumadi, Citation2013; Samuelsson et al., Citation2018). Also, as the teachers want assessment to be fair, they give students several opportunities to perform, but again limited time makes this difficult.

The subject matter influences teachers’ assessment purposes (Prøitz, Citation2013). The teachers have the purpose of enacting the syllabus, especially the knowledge requirements. These are, however, considered problematic as some standards are very content-specific, but these can only be assessed once, conflicting with teachers’ purpose of assessing at least twice to help students succeed. The Civics syllabus also stipulates that different kinds of assessments should be used, both written and oral, but some students do not perform well in some kinds of assessments. This causes tensions between the purposes of enacting policy and pulling for students. Another issue in the explored Civics courses is that the content is comprehensive and therefore not everything is assessed. Further, as Civics is about covering current issues, assignments need to be updated. Both these may cause tension between the purposes of enacting policy and handling administration.

Earlier findings (Biberman-Shalev et al., Citation2011; McMillan, Citation2001) showed that teachers in open/flexible subjects with weak framing, such as Civics, tend to take effort into account in grading. The teachers in this study, however, do not mention effort, attending class or homework in regard to assessment. This thus seems to be different in the Swedish context. Further, Civics in Sweden is not all open/flexible and weakly framed. Regarding the subject’s specific content knowledge requirements, teachers describe Civics partly as closed with strong framing, which restricts their assessment and grading practices. Further, the Swedish Civics syllabus has been described as focusing on generic skills (Wahlström et al., Citation2020). But when teachers talk about assessment, they express skills in connection with subject content. For example, a skill like analysing is described as different in Civics than in other subjects, or students can be told to use a specific social science model in an analysis.

Teachers need to balance between different purposes in the decisions about assessments. As teachers differ in beliefs and values, they balance the diverse purposes differently, resulting in different assessment practices (Liu et al., Citation2021; McMillan, Citation2003). For example, emphasising enacting policy may give a summative-oriented practice, and emphasising improving learning and pulling for students gives a formative-oriented practice (Leong, Citation2014). However, the rationales for teachers’ assessment decision making seems to be individual and idiosyncratic, influenced by a hodgepodge of factors and based on on-the-job experiences (McMillan, Citation2003) and there is still more to explore about this.

The model of assessment decision making (McMillan, Citation2003) can be developed from the results in this study. New external factors not mentioned in the model are administrative conditions (time, schedule etc.). In the Swedish context, the demands in the national curriculum and syllabus strongly affect teachers’ assessment practices. High-stakes testing is not much of an influence, and not at all in Civics at upper secondary school as there are no national tests in Civics, and Swedish teachers are not evaluated based on test results. The factor pulling for students is found to be more nuanced, with aspects such as student influence, giving several opportunities and easing students’ stress and workload. Further, improving learning in Civics includes updating assignments to current topics.

Our themes are somewhat similar to earlier findings (Brown, Citation2004; Harris & Brown, Citation2009). New findings in our study are the purpose of handling administration and some sub-themes. Improving learning is similar to their same conception and the summative assessment part of enacting policy relates to making students accountable for learning. On the other hand, teachers in our study do not relate to accountability for schools or to irrelevance of assessments. Regarding the seven purposes found by Harris and Brown (Citation2009), there are similarities in the purpose of enacting policy (compliance), but Australian teachers viewed this as inaccurate and negative, while Swedish teachers can be both negative and positive. Reporting to parents is also found in our study, but the Swedish teachers talk about this in relation to grading mandated in the curriculum. Our theme of pulling for students includes their purposes of extrinsically motivating students, facilitating group instruction, teacher use for individual learning, and joint teacher and student use for individualising learning. We argue that all these have the common purpose of helping students to succeed. Their purpose of external reporting is not found among the Swedish teachers. Our findings emanate from data, unlike the theoretically constructed conceptions in Brown’s studies (Brown, Citation2004; Harris & Brown, Citation2009) and Newton (Citation2007). Also, they mix purposes about both classroom assessments and assessment systems. Our study focuses only on teachers’ purposes regarding their own assessment tasks, which may explain differences between our themes and theirs. Differences may also be due to teachers’ assessment practices being influenced by social and cultural experiences (Klenowski, Citation2013).

Furthermore, we agree with Newton (Citation2007) that grading on an aggregated level can have different purposes, but in the classroom, to teachers, supporting grading is clearly an explicit purpose per se. In Sweden, the use of grades for certification and selection, together with teachers' responsibility for grading (Lundahl et al., Citation2017), make gathering evidence to justify grades an important purpose to teachers, heavily influencing teachers’ assessment decisions. Also, the strong emphasis on summative assessments in the national curriculum (Wahlström & Sundberg, Citation2015) likely forces Swedish teachers to become more explicit and transparent about their decisions than in many other national contexts.

This study strengthens the need for an adapted validity process for the complex school context (Bonner, Citation2013; Cizek, Citation2009; Kane & Wools, Citation2020). This, in combination with multiple and often diverse purposes, makes it difficult to validate (Newton, Citation2017). An assignment cannot be valid for all the diverse purposes teachers seem to have and teachers need to compromise on validity. Meaningful validation of teachers’ assessments necessitates a simplified validating process, which is practical for teachers to handle (Bonner, Citation2013). A moderated argument-based approach to validity could be useful (Kane, Citation2016). Teachers should identify their purposes and prioritise between them, focusing on the main purposes of assessments, keeping in mind the limited validity regarding other purposes (Kane, Citation2016; Newton, Citation2017). Also, validity demands are different depending on the purpose. For example, validity is more important if the main purpose is to obtain evidence for grading than if the main purpose is formative. Ideally, different skills should be tested on several occasions and using different methods (Messick, Citation1989), which is something that the teachers also want. Still, time limits teachers’ work, and the content-specific standards in Civics are especially difficult to handle. In practice, to keep up, teachers need to make superficial evaluations of validity, focusing on the utility of the assessments for their purposes and not measurement aspects (Kane & Wools, Citation2020).

This study is limited to a few Swedish Civics teachers in upper secondary school. The different backgrounds and settings of the participants should have captured most of the variation in the purposes of assessments, at least in the Swedish Civics context, and enabled qualitatively distinct themes, which may be used for “generalisation through recognition of patterns” (Larsson, Citation2009). We believe most of the purpose themes should be applicable in more subjects, except for the specific Civics themes, but further studies need to be conducted in other subjects and contexts. There is still little knowledge about teachers’ decision-making and assessment practices, including how these are influenced by multiple and diverse purposes. There is a need for further studies about these decisions, and about how teachers handle tensions between diverse purposes.

In summary, Swedish Civics teachers in upper secondary school have multiple and diverse purposes of their assessments. In their daily work, they need to balance these different purposes in their decisions about assessment tasks, which form their assessment and grading practices. They also need to validate their assessments, using a simplified and superficial validity, focusing on their main purpose regarding the specific task. With a better understanding of the complexity in the assessment process, including diverse purposes, teachers are hopefully better equipped to make appropriate decisions about their assessments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bernstein, B. (1975). Class, codes and control. Routledge.

- Biberman-Shalev, L., Sabbagh, C., Resh, N., & Kramarski, B. (2011). Grading styles and disciplinary expertise: The mediating role of the teacher’s perception of the subject matter. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(5), 831–840. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.01.007

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-008-9068-5

- Bonner, S. M. (2013). Validity in classroom assessment: Purposes, properties, and principles. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), Sage handbook of research on classroom assessment. SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218649.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brookhart, S. M. (2009). Mixing it up: Combining sources of classroom achievement information for formative and summative purposes. In H. Andrade & G. J. Cizek (Eds.), Handbook of formative assessment [eBook] (pp. 279–296). Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203874851.

- Brookhart, S. M., & Durkin, D. T. (2003). Classroom assessment, student motivation, and achievement in high school social studies classes. Applied Measurement in Education, 16(1), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15324818AME1601_2

- Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers’ conceptions of assessment: Implications for policy and professional development. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 11(3), 301–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000304609

- Bryman, A. (2016). Social research methods (5th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Cizek, G. J. (2009). Reliability and validity of information about student achievement: Comparing large-scale and classroom testing contexts. Theory into Practice, 48(1), 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1080/00405840802577627

- Curry, K., & Smith, D. (2017). Assessment practices in social studies classrooms: Results from a longitudinal survey. Social Studies Research and Practice, 12(2), 168–181. https://doi.org/10.1108/SSRP-04-2017-0015

- Englund, T. (1986). Samhällsorientering och medborgarfostran i svensk skola under 1900-talet. Pedagogiska institutionen, Uppsala University.

- Forsberg, E., & Lindberg, V. (2010). Svensk forskning om bedömning: En kartläggning. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Gioka, O. (2009). Teacher or examiner? The tensions between formative and summative assessment in the case of science coursework. Research in Science Education, 39(4), 411–428. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11165-008-9086-9

- Harris, L. R., & Brown, G. T. L. (2009). The complexity of teachers’ conceptions of assessment: Tensions between the needs of schools and students. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 16(3), 365–381. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940903319745

- Hirsh, Å, & Lindberg, V. (2015). Formativ bedömning på 2000-talet – en översikt av svensk och internationell forskning. Vetenskapsrådet.

- Jansson, T. (2011). Vad kommer på provet?: Gymnasielärares provpraxis i samhällskunskap. Karlstad University.

- Kane, M. T. (2016). Explicating validity. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 23(2), 198–211. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1060192

- Kane, M. T., & Wools, S. (2020). Perspectives on the validity of classroom assessments. In S. M. Brookhart & J. H. McMillan (Eds.), Classroom assessment and educational measurement (pp. 11–26). Routledge, Taylor & Francis Group.

- Klenowski, V. (2013). Towards improving public understanding of judgement practice in standards-referenced assessment: An Australian perspective. Oxford Review of Education, 39(1), 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.764759

- Koch, M. J., & DeLuca, C. (2012). Rethinking validation in complex high-stakes assessment contexts. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 19(1), 99–116. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2011.604023

- Larsson, S. (2009). A pluralist view of generalization in qualitative research. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 32(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437270902759931

- Leong, W. S. (2014). Knowing the intentions, meaning and context of classroom assessment: A case study of Singaporean teacher’s conception and practice. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 43, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2013.12.005

- Liu, J., Gao, R., Guo, S., Haynes, A., Ni, S., & Tang, H. (2021). Examining the associations between educators’ ethics position and ethical judgment in student assessment practices. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 70, 101024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2021.101024

- Lumadi, M. W. (2013). Challenges besetting teachers in classroom assessment: An exploratory perspective. Journal of Social Sciences, 34(3), 211–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/09718923.2013.11893132

- Lundahl, C., Hultén, M., & Tveit, S. (2017). The power of teacher-assigned grades in outcome-based education. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 3(1), 56–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/20020317.2017.1317229

- Mattson, H. (1989). Proven i skolan sedda genom lärarnas ögon. Pedagogiska institutionen, Umeå university.

- McMillan, J. H. (2001). Secondary teachers’ classroom assessment and grading practices. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 20(1), 20–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2001.tb00055.x

- McMillan, J. H. (2003). Understanding and improving teachers’ classroom assessment decision making: Implications for theory and practice. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 22(4), 34–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2003.tb00142.x

- McMillan, J. H. (2013). Why we need research on classroom assessment. In J. H. McMillan (Ed.), Sage handbook of research on classroom assessment (pp. 2–16). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781452218649.n1.

- Messick, S. (1989). Validity. In R. L. Linn (Ed.), Educational measurement (3rd ed., pp. 13–103). American Council on Education & Macmillan.

- Newton, P. E. (2007). Clarifying the purposes of educational assessment. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 14(2), 149–170. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940701478321

- Newton, P. E. (2017). There is more to educational measurement than measuring: The importance of embracing purpose pluralism. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 36(2), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/emip.12146

- Odenstad, C. (2011). Prov och bedömning i samhällskunskap: En analys av gymnasielärares skriftliga prov. Karlstad University.

- Prøitz, T. S. (2013). Variations in grading practice – subjects matter. Education Inquiry, 4(3), 22629. https://doi.org/10.3402/edui.v4i3.22629

- Sadler, D. R. (2009). Indeterminacy in the use of preset criteria for assessment and grading. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 34(2), 159–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930801956059

- Samuelsson, J., Brismark Östlin, A., & Löfgren, H. (2018). Papperspedagoger – lärares arbete med administration i digitaliseringens tidevarv (Report 2018:5). IFAU.

- Shepard, L. A. (2016). Evaluating test validity: Reprise and progress. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 23(2), 268–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2016.1141168

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654307313795

- Skolverket. (2011). Läroplan, examensmål och gymnasiegemensamma ämnen för gymnasieskola 2011. Author.

- Skolverket. (2017). Swedish grades. Author.

- Stiggins, R. J. (2001). The unfulfilled promise of classroom assessment. Educational Measurement: Issues and Practice, 20(3), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3992.2001.tb00065.x

- Swedish Research Council. (2017). Good research practice. Author.

- Torrez, C. A., & Claunch-Lebsack, E. A. (2014). The present absence: Assessment in social studies classrooms. Action in Teacher Education, 36(5–6), 559–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/01626620.2014.977756

- Wahlström, N., Adolfsson, C.-H., & Vogt, B. (2020). Making social studies in standards-based curricula. JSSE – Journal of Social Science Education, 19(SI), 66–81. https://doi.org/10.4119/JSSE-2361

- Wahlström, N., & Sundberg, D. (2015). Theory-based evaluation of the curriculum Lgr 11. IFAU (Working Paper).