ABSTRACT

This article addresses study programme leadership, a still-emerging phenomenon in European higher education (HE). Given its novelty, descriptions and insights into study programme leadership remain sparse. Therefore, this study aims to describe and critically explore health profession study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities as they appear in institutional mandates. A qualitative hermeneutical interpretative text analysis is conducted using data derived from 14 Norwegian HE institutions. This research focuses on expectations of study programme leadership actions as expressed through the verbs used in the sentences of the mandates. Accordingly, we reveal that the verbs reflect diverse directions: controlling, facilitating, coordinating, and advising. To obtain our findings, we draw on a reflexive leadership approach. We demonstrate that diverse study programme leadership actions require different modes of organising. Thus, this study reveals the tensions among the various leadership actions constructed in HE mandates.

Introduction

Study programme leadership has emerged as a new phenomenon in European higher education (HE) in the last decade. In HE, leadership at all organisational levels is considered essential to enhance quality (Helseth et al., Citation2019). Thus, study programme leadership is deemed crucial to ensure educational quality, including the development of complete, coherent, and relevant study programmes (Stensaker et al., Citation2018), to influence teaching and learning culture (Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016) and enhance student learning (Cahill et al., Citation2015; Gibbs et al., Citation2008; Ramsden et al., Citation2007).

The international literature lacks research on general leadership in academia (Bryman, Citation2007; Buller, Citation2013). Additionally, it advocates more research on educational leadership (Stensaker et al., Citation2018), particularly at the local levels closest to students (Irving, Citation2015; Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013; Stensaker et al., Citation2018). However, some studies have specifically explored study programme leadership. HE studies from the UK describe how study programme leaders’ are expected to undertake a complex range of conflicting activities (Cahill et al., Citation2015; Irving, Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2015; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013). Several of these studies recommend that study programme leadership focuses more on pedagogical development work than on administration in the future and conclude with a need to specify the study programme leaders’ mandate and role (Cahill et al., Citation2015; Mitchell, Citation2015; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013). Indeed, Mitchell (Citation2015) encourages HE institutions to more clearly articulate their expectations for study programme leadership.

Study programme leaders at a Swedish university describe how they manage their mid-level leadership role, balancing between an external mandate from their formal organisation and an internal mandate formed by teachers’ expectations. The study indicates that these leaders emphasise their internal mandates regarding their pedagogical development work, but it does not evaluate their institutions’ external mandates. The authors conclude that further research of study programme leaders’ mandates is needed (Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016).

Accordingly, the present study explores study programme leadership in Norwegian HE. Study programme leadership has recently gained increased attention. Currently, it is one of seven objectives for the commitment to Norwegian HE quality. The Ministry of Education (White Paper Citation16 (Citation2016-Citation2017), Citation2017) indicates that study programme leaders should have a clear mandate to ensure educational quality and sufficient strategic space to develop complete, coherent, and relevant programmes. These leaders, therefore, play an essential role in initiating and leading development processes at the study programme level.

Internationally, different titles for study programme leaders are used (Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016; Mitchell, Citation2015; Stensaker et al., Citation2019). In this study, we use study programme leader, which is the most common title in Norwegian HE (Aamodt et al., Citation2016) and in national guidelines (White Paper Citation16 (Citation2016-Citation2017), Citation2017). We define a study programme leader as a local-level academic employee who is closest to the students and is primarily responsible for planning, implementing, evaluating, and developing one or several study programmes at an HE institution (Aamodt et al., Citation2016; Grepperud et al., Citation2017; Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016).

In 2016, the first major survey of all individuals in a study programme leadership position was conducted (Aamodt et al., Citation2016). Interestingly, these leaders reported inadequate and ambiguous mandates (Aamodt et al., Citation2016). Recent articles have been published using the same survey (Stensaker et al., Citation2018, Citation2019) with findings consistent with international research. Initially, it reports that the role of a study programme leader is perceived more as a coordinator than an authoritative leadership role. Moreover, this leadership position is complex because it is framed by a number of administrative guidelines, routines, and expectations. A newly published doctoral thesis has confirmed these findings and suggests that new public management (NPM) is the prevailing educational policy ideology that influences study programme leadership (Johansen, Citation2020).

Aamodt and co-authors’ report on study programme leadership (Aamodt et al., Citation2016) and subsequent publications (Stensaker et al., Citation2018, Citation2019) have contributed to the topic's dual, political- and research-oriented focus. Indeed, in 2017, increased political attention sparked changes in HE regulations (Forskrift om tilsyn med utdanningskvaliteten i høyere utdanning, Citation2017). These new regulations outline a novel direction in study programme leadership that is more pedagogical oriented and extends beyond coordination and quality assurance (Forskrift om tilsyn med utdanningskvaliteten i høyere utdanning, Citation2017; White Paper Citation16 (Citation2016-Citation2017), Citation2017). To our knowledge, no one has investigated the content of Norwegian HE institution mandates in light of this regulatory change. Therefore, we find it interesting to explore how HE institutions describe their study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities. Furthermore, this study intends to focus focuses on health profession study programmes. Thus far, we have not identified studies that examine study programme leadership in these specific programmes.

To summarise, the abovementioned literature indicates a need to clarify expectations regarding study programme leaders’ responsibilities and work tasks. Moreover, the political expectations for these leaders responsibilities are high, and a new direction in study programme leadership is advocated. Yet, there are limited descriptions of and insights into what this leadership actually entails. How institutions translate political expectations and articulate study programme leadership can provide valuable insights into how this leadership is framed. Therefore, this study aims to describe and critically explore study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities in health profession study programmes as they appear in institutional mandates.

In the next section, we present our theoretical perspective. We have chosen a reflexive leadership approach to describe and critically explore study programme leadership. The methods section describes our data extraction and analysis of the institutional mandates. Our research uses a hermeneutical approach and is inspired by Ricoeur's (Citation1991b) descriptions of interpreting and understanding a text. Thus, our findings reveal how the expectations for study programme leaders’ actions are expressed through the verbs in the mandates’ sentences. Finally, following elements in Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) reflexive leadership thinking concept, we discuss what modes of organising are reflected in our interpretation of the mandates.

Theoretical perspective on leadership

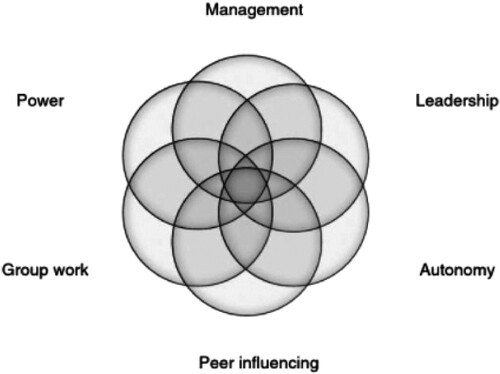

The current article employs elements from Alvesson et al. (Citation2017) reflexive leadership approach. Reflexivity is: “[…] the ambition to carefully and systematically take a critical view of one's own assumptions, ideas, and favoured vocabulary and to consider if alternative ones make sense” (Alvesson et al., Citation2017, p. 14). Alvesson et al. (Citation2017) and Alvesson and Blom (Citation2019) argue for reflexive leadership thinking because it is often unclear what leadership entails in different situations and contexts. They have developed a framework describing leadership as one of six modes of organising. The framework consists of three vertical modes: leadership, management, and power, and three horizontal modes: group work, peer influencing, and autonomy (Alvesson et al., Citation2017) The three vertical (hierarchical) modes of organising express an asymmetric relationship where leaders have more influence than employees. In comparison, the three horizontal modes express an equal relationship and distributed influence between colleagues, i.e., a team. Below, we briefly describe this framework's diverse modes of organising.

Leadership is vertical, depends on voluntary followers and is closely linked to social context and local culture: “[…] influencing ideas, meanings, understandings and identities of others within an asymmetrical (unequal) relational context” (Alvesson et al., Citation2017, p. 3). This definition mainly considers leadership an amalgam of communication, relationship, understanding, and sensemaking. Leadership is often confused with management, i.e., administration and control that requires subordinates and is exemplified by planning, budgeting, resource allocation, procedures, and rules. The last vertical mode is power, a way of performing “coercive force” (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). Power requires political skills and authority, instantiated in rewards, sanctions, group pressures, and control over critical resources.

Conversely, the horizontal modes work without a top-down impact. The first, group work, is characterised by no member having formal leadership responsibility; group or team members share their commitments, and influence is exerted through discussions and collegial processes where experience and knowledge are shared. Peer influencing is another horizontal mode, network-based, where respected peers in the same occupation but outside their respective workgroup are invited to offer advice for an ongoing work process. Autonomy, “non-following” and “self-directed at work,” is the last horizontal mode (Alvesson et al., Citation2017, p. 18). Autonomous employees are often well-educated, independent thinkers who can manage themselves. Thus, minimising hierarchical influence is central.

Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) argue that their six modes of organising are essential theoretical distinctions for a more reflective approach to leadership. However, the authors point out that both vertical and horizontal modes will be found in almost all organisations and two or more will typically overlap, as they illustrated below in : “Modes of organizing as overlapping coordination mechanisms”.

Figure 1. Alvesson, Blom and Sveningsson's (Alvesson et al., Citation2017, p. 23, .1) “Modes of organizing as overlapping coordination mechanisms”.

As described above, study programme leadership is considered a solution for developing HE quality, yet descriptions and insights into what this leadership entails are sparse. We also know little about the expected actions of study programme leaders. We, therefore, deem Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) framework relevant for gaining insights into HE institutions’ expectations of study programme leadership. This paper will return to the alternative modes of organising in the discussion section to critically explore our findings.

Methods

The study has a descriptive and exploratory qualitative design with a hermeneutical approach. According to Alvesson and Sköldberg (Citation2018, p. 115) hermeneutics is both theory or method - or “sometimes science of interpretation”. Moreover, Ricoeur (Citation1991a) states that hermeneutics “is the theory of the operations of understanding in their relation to the interpretation of texts”. Thus, since our analysis intended to interpret study programme leaders’ written mandates in a HE context, a hermeneutical analysis approach inspired by Ricoeurs description of “What is a text” was chosen (Ricoeur, Citation1991b)

Data selection

This study is part of a PhD project that focuses on health profession study programmes in HE. The data are selected from formal, written public documents from 14Footnote1 Norwegian HE institutions’ education quality systems, including eight universities and six university colleges that offer a health profession bachelor's programme (180 ECTS credits) or a professional study programme in medicine (MB degree). National laws require HE institutions to have an internal system for quality assurance that is public and outlines the quality of its goals, roles, tasks, and responsibilities (Forskrift om tilsyn med utdanningskvaliteten i høyere utdanning, Citation2017). The selected documents thus describe study programme leaders’ work tasks, and responsibilities hereafter named mandates (mandates; n = 14). Data selection and electronic searches for mandates were carried out in January and February 2020. In the selection process, we discovered that the institutions use the same mandate for study programme leadership regardless of size, profession, or discipline. Therefore, the documents selected in this study are generic for all HE study programmes and are not specific to health profession study programmes.

Data analysis

A hermeneutical analysis approach was conducted inspired by Ricoeur's (Citation1991b) descriptions of interpreting and understanding a text. This approach was chosen because it is based on text interpretation (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2018; Ricoeur, Citation1991a). Here, our texts comprise written mandates about study programme leadership in a HE context, and we sought to interpret the mandates and create meaning from them. Ricoeur (Citation1991b, p. 105) defines a text as “any discourse fixed by writing.” A written text is, however, more than just an author's intention; it becomes independent and lives its own life. Hence, a hermeneutical text understanding in this tradition aims to understand the meaning of an actual text by how the receiver interprets the text. When interpreting a text, a reader allows a text to be a voice. Thus, when we read the written mandates about study programme leadership, we explain, understand, and interpret the meaning of their text i.e., we can derive new meanings from the mandates, and therefore, these texts can contribute to an opening up of our understanding of study programme leadership as an HE phenomenon.

In the first phase of the analysis, a naive reading of each mandate was conducted to “let the texts speak” to us (Ricoeur, Citation1991b, p. 108). We read the mandates multiple times to form an overall impression and familiarise ourselves with their content. Taking departure from a hermeneutical approach, the analysis aims to search for the meaning of the text; in other words, we search for the meaning expressed in the mandates. Throughout this process, we focused on the following questions: What work tasks are study programme leaders expected to perform? How are their responsibilities described? The mandates are relatively short and condensed texts with a particular structure and use of language and give the study programme leaders the direction to act a certain way. Accordingly, our rereading identified verbs as the keywords in the texts as they describe expectations of a study programme leader's actions. Grammatically, the verbs of a sentence are essential for describing how something is done in relation to whatever the aim or object of the sentence expresses (i.e., an overall study programme with a description of learning outcome). Verbs in a sentence express actions and describe what someone is doing, is going to do, or has done through various tenses. In the mandates, the verbs thus became essential, expressing what specific actions are expected of study programme leaders. Additionally, since our research question scrutinised the expectations for a study programme leader's actions as work tasks and responsibilities, the sentences’ verbs became our point of departure for the analysis.

According to Ricoeur (Citation1991b), reading and interpreting comprise explanation and understanding. In the explanatory phase, the reader performs an analysis that intends to bring out the structure of the text. In our structural analysis, the individual verbs were therefore first manually highlighted and collected as open codes. The first author then inserted the open codes (the verbs) in NVivo12 (QSR International, Citation2020). Here, 72 different verbs were registered as open codes in NVivo12. The verbs were initially grouped so that those belonging to each particular group were merged ().

To capture the meaning of the verbs, the mandates were again reviewed systematically. The underlying questions in this phase were as follows: What directions do the verbs point in? What kinds of actions and work tasks are connected to the verbs? In this focused rereading, we searched for sentences or parts of sentences that were linked to each individual verb that expressed the responsibilities and work tasks to be performed. These sentences were then coded into each single verb as a unit of meaning. Next, verbs with these units of meaning were categorised into thirteen descriptive subthemes that were based on similar content. Finally, the subthemes were abstracted into four main themes. An example of this analysis is shown in .

Table 1. Example of analysis.

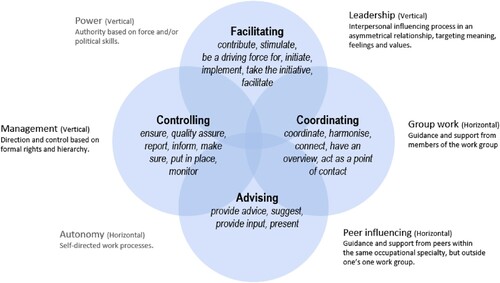

Ricoeur (Citation1991b, p. 116) considers the purpose of structural analysis as “ […] carrying out the segmentation of text, then to establish the various levels of integration of the parts in the whole.” Accordingly, we repeatedly developed subthemes and then abstracted them into main themes several times through our structured analysis to ensure that the themes were grounded in the data. Ultimately, the themes from different levels were integrated into the whole. The structural analysis was inductive and developed a model to describe study programme leadership (). After completing the analysis, we selected Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) theoretical framework to further explore and discuss our findings.

Findings

The data analysis revealed four main themes. Each consists of two to four subthemes, as illustrated in .

We captured the expectations for different actions of study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities by analysing the verbs. These leadership actions are reflected in the main theme headings: controlling, facilitating, coordinating, and advising.

Controlling

We named the first main theme controlling. Certain verbs, ensure, quality assure, report, make sure, put in place, and monitor, suggest that study programme leadership should be controlling. Study programme leadership encompasses governance, administration, quality assurance, and control. A study programme leader should be task-oriented and deliver results following deadlines. This main theme also comprises four subthemes: ensure the programme's completeness and coherence, monitor compliance with external regulations and internal quality system, ensure procedures for student involvement, and report in accordance with requirements.

Ensure the programme's completeness and coherence

A study programme leader is assigned clear responsibilities for ensuring a study programme's coherence, progression, and relevance. This entails the overarching responsibility for ensuring high educational quality and teaching methods that contribute to student learning. A course coordinator directs each course, but the study programme leader is responsible for ensuring quality across courses. One main task for a study programme leader is thus to monitor that courses sufficiently contribute to students achieving the programme's learning outcomes. In the mandates, verbs such as ensure, quality assure, monitor, make sure and put in place are used, but the mandates do not express what actual decision-making authority a study programme leader must make decisions and changes that affect the overall coherence of a programme. For example, there are no descriptions of whether they have the authority to make decisions that affect course coordinators, teachers, or administrative staff.

Monitor compliance with external regulations and internal quality system

To ensure that those involved in a programme comply with external regulations and the internal rules that are defined by an institution's quality system, certain verbs are highlighted in the mandates: ensure, put in place, monitor, and follow up. Some examples of these include monitoring teaching staff competence, ensuring the quality student learning outcomes, and following up on a student's suitability for a profession. This responsibility is delegated from top-level leadership and entails managing and controlling a study programme's daily operations following correct procedures. Noncompliance must be reported to line leadership: “report any quality non-conformances to the department head or the dean.” (m2)

Ensure procedures for student involvement

A study programme leader is specifically responsible for ensuring that students participate in a programme's quality assurance and development processes. In particular, to ensure that the extant procedures regarding student involvement accord with legislation and an institution's quality system. Some examples of student involvement include student feedback, collected through course evaluations, elections of student representatives, and student representation in processes and decisions that impact student learning and learning environments. The responsibility of a study programme leader is to arrange for student involvement to be maintained and to monitor and ensure that this is realised. Student involvement procedures can be delegated to other teachers in a programme, such as course coordinators, but some mandates indicate that a study programme leader is expected to directly contact and continually collaborate with student representatives.

Report in accordance with requirements

Reporting in accordance with external requirements and the internal deadlines defined by an internal quality system is required. Writing an annual study programme report is a highlighted task for a study programme leader. Furthermore, several mandates provide a detailed description of the content of this report. Evaluations from course coordinators, feedback from teachers, and student surveys are mentioned. Moreover, each report should include analyses, i.e., plans for implementing improvement measures to enhance a programme's quality. Depending on how an educational institution is organised, such a report is submitted to a department head, dean, or other leaders.

Facilitating

The second main theme derived from the verbs indicates that study programme leadership is about facilitating; a study programme leader should contribute to, stimulate, be a driving force for, initiate, implement, take initiative, and facilitate. These verbs suggest that study programme leadership is meant to be a driving force in study programmes, which entails influencing others to take actions, i.e., facilitating. Furthermore, a study programme leader is responsible for developing a robust academic culture to help inculcate a sense of ownership among academic staff and students and their joint commitment to the study programme. Additionally, interaction, dialogue, relationship, and network building are recurrent concepts in the mandates. A study programme leader is thus expected to build both internal and external relationships, e.g., in practical fields and international communities. The theme of facilitating consists of four subthemes: contribute to a good learning culture and professional fellowship, promote collaboration with the field of practice, facilitate international experience in the programme, and be a driving force for development and change.

Contribute to a good learning culture and professional fellowship

Clear expectations regarding the development of a good learning culture and a professional academic community that includes teachers and students are expressed. Study programme leadership must contribute to a quality culture that is characterised by dialogues, good relationships, and collaborations. Learning and improvement are priorities, involving “the whole academic faculty so that they feel a sense of ownership of the programme” (m5). A study programme leader must establish meeting arenas and facilitate dialogues among both the teaching staff affiliated with the programme and students. Moreover, study programme leaders are expected to foster a robust learning culture for students and include them in an academic community. Encouraging students to play an active role in the learning process and participate in the development of the programme is underscored. Furthermore, “to contribute to students develop a strong and independent identity within the knowledge areas of the programme.” (m8)

Promote collaboration with the field of practice

A study programme leader holds the particular responsibility to promote collaboration with the field of practice. Facilitating interprofessional education activities to strengthen student interprofessional competencies is highlighted. Although facilitating interdisciplinarity is expected, there is no detailed description of how to achieve this. Rather, it is more generally expressed as facilitating interdisciplinary interactions with the field of practice, a labour market, and general society.

Facilitate international experience in the programme

Internationalisation is part of the portfolio of tasks. Study programmes are expected to maintain an international academic profile through emphasised collaborations with relevant international partners. A study programme leader must contribute to, facilitate, and work for an international focus and collaborations. Furthermore, they are responsible for “facilitating exchange opportunities in the study programme for both staff and students.” (m6)

Be a driving force for development and change

As the fourth area of responsibility, a study programme leader is expected to initiate the academic and pedagogical development of an existing study programme and prepare new courses. Verbs such as facilitate, stimulate, initiate, and be a driving force are used in the mandates to describe these tasks. The description of a study programme leader as a driving force for development and change regarding the academic content of a study programme is underscored via the specific responsibility to develop “the academic content, profile, and relevance of the study programme” (m6) and facilitate that “teaching, learning, and assessment methods are research-based” (m1). Developing student-active, digital teaching, and relevant learning methods should be prioritised; a study programme leader “must be a driving force for the implementation and use of digital tools in teaching and learning, and assessment by all the academic fellowship” (m4). Moreover, stimulating research and development work in an academic fellowship is accomplished, for example, through collaborative projects in a practical field.

Coordinating

The third main theme is coordinating. A study programme leader is expected to coordinate, harmonise, connect, have an overview, and act as a point of contact. Thus, study programme leadership entails coordination. The mandates indicate that a leader acts as an important nexus for a programme's different internal and external actors. In other words, a point of contact in professional processes. This main theme entails three subthemes: coordinate daily operation of the programme, maintain an overview of academic resources, and be a nexus for different actors.

Coordinate daily operation of the programme

A study programme leader is expected to coordinate the daily operations of a study programme, for example, by coordinating semester plans, teaching timetables, and exam schedules. Collaboration with administrative staff in these daily operations indicates that some administrative support is associated with study programme leadership.

Maintain an overview of academic resources

Helping coordinate academic resources in a programme by maintaining an overview of academic competences and resources within the programme is repeatedly emphasised in the mandates: “In collaboration with the faculty's management, the study programme leader coordinates the resources in the programme and the distribution of work tasks to the academic staff” (m7). Most study programme leaders have no other formal responsibilities for employees involved in their study programme. Only one of the mandates designates a study programme leader with formal line management of teaching staff.

Be a nexus for different actors

The mandates state that the development of study programme quality is a collective task for the academic fellowship linked to a study programme, but a study programme leader plays an essential coordinating role in this process. Specifically, the coordination of collaborations across courses and between course coordinators is a prominent task for a study programme leader. The mandates stress that many actors are involved in a study programme including students, teaching staff, administrative staff, course leaders, and various internal and external committees and partners. This necessitates someone who maintains oversight and coordinates the different professional development processes. This function is assigned to study programme leaders, and their responsibility is primarily to coordinate and ensure coherence and progression in their study programme, as described above. This relates to both quality assurance (and monitoring compliance with rules and regulations) and quality development. A study programme leader does not independently perform coordination work; it occurs in collaboration with a dean, course coordinators, and administrative staff. Maintaining contacts and coordinating processes that involve students comprise another area of responsibility; a study programme leader should “act as a point of contact for academic assessments of international mobility, leaves of absence, specific recognition of study abroad and exemptions, etc.” (m7).

Advising

The fourth main theme, advising, expresses a study programme leader's advisory responsibility through verbs such as provide advice, suggest, provide input, and present. This theme contains two subthemes: obtain internal and external inputs to improve the programme and provide advice to the next leadership level.

Obtain internal and external inputs to improve the programme

Study programme leadership is relational work that involves dialogues and collaborations with various actors and networks, as described above. Through different processes, a study programme leader must obtain the input and advice needed to develop and improve a programme's quality, for example, through dialogues with course coordinators or collegial processes including consulting teaching staff, student evaluations, and meetings with partners in the field of practice. Some study programmes have organised a programme committee that is chaired by their study programme leader. Such a committee is a council comprising representatives from students, teaching staff, administrative staff, and the field of practice.

Provide advise to the next leadership level.

According to the mandates, study programme leaders provide advice and recommendations to the next leadership level. For example, they can recommend developments for and changes to a programme owner. Advising on marketing, recruiting, and networking in a practical field is also expected. Some mandates indicate that a study programme leader has advisory responsibility. Moreover, final decision-making regarding necessary changes is addressed and decided at a higher leadership level.

Discussion

This study aims to describe and critically explore study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities in health profession study programmes as they appear in institutional mandates. In the analysis, we focused on the expectations of a leader's actions, expressed through the verbs used in the mandates. We revealed that these verbs point to various actions: controlling, facilitating, coordinating, and advising. Accordingly, we develop the following overarching question to stimulate further discussion: What modes of organising are reflected in our interpretation of the mandates? Thus, using Alvesson et al.'s framework (Citation2017, p. 23, Figure 2.1) as a theoretical lens to explore our findings, we have developed as follows:

Figure 4. Our findings seen through Alvesson, Blom and Sveningsson' (Citation2017, p. 23, Figure 2.1): “Alternative modes of organizing”.

demonstrates that the verbs point to various actions that may require different modes of organising. Using Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) framework as a theoretical lens, we can identify examples of management, leadership, group work, and peer influence in our findings. In contrast, power and autonomy are mostly absent in the mandates. These modes are thus blurred in . In addition, our discussion of the main findings reflects both Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) framework and previous research on study programme leadership.

In the current study, study programme leadership is, notably, not assigned a formal power. We describe study programme leadership as controlling, facilitating, coordinating, and advising. We do not, however, find verbs that describe these leaders’ exertion of power or decision-making authority, which agrees with other studies that describe how these leaders lack the power and authority to make administrative and pedagogical decisions (Aamodt et al., Citation2016; Cahill et al., Citation2015 Irving, Citation2015; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013;; Stensaker et al., Citation2019). Nevertheless, our study reveals how study programme leadership is framed in institutional mandates and adds new insights by disclosing that these leaders are not assigned formal power as an organising mode.

According to Alvesson et al.’s (Citation2017), power is essential for organisations to get things done. It is linked to authority and exists as a kind of coercion to influence and effect changes. Moreover, power is often mixed with leadership or management that intends to vertically influence subordinates. Traditionally, a HE institution is considered an organisation with a relatively horizontal structure where academic freedom, expertise, and collegial processes influence decision-making structure (Sahlin & Eriksson-Zetterquist, Citation2016). Thus, study programme leadership takes place in a context where autonomy is emphasised in the professional fellowship (Mårtensson, Citation2014). Horizontal modes of organising must therefore be accounted for in study programme leadership, since cooperation and dialogue seems to be more important than formal power (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). Accordingly, Sahlin and Eriksson-Zetterquist (Citation2016) suggest that individual HE leaders should not be given power; they are expected to make decisions based on their knowledge of collegial processes. Stensaker et al. (Citation2019) affirm that decisions regarding, for example, learning outcomes and teaching methods, are primarily made through cooperation among colleagues. Moreover, they state that informal influence can be as crucial as formal power, given HE's traditionally collegial decision-making processes. Nevertheless, we can assume that a lack of power can lead to dilemmas in study programme leadership, particularly when decisions are needed. For example, our findings show that study programme leaders are responsible for coordinating resources and teacher competences. Most leaders, however, do not have line management authority over the teaching staff involved in their programme. Furthermore, there is no description of how these leaders should interact during disagreements or conflicts. Consistent with the literature, we can thus assume that study programme leadership must balance employee needs for autonomy and academic freedom (Alvesson et al., Citation2017; Sahlin & Eriksson-Zetterquist, Citation2016) with collaboration to weigh and pursue common strategic objectives (Rasmussen, Citation2014).

Overall, it seems to us that decision-making is outside the area of responsibility of study programme leadership. Several of the mandates underline that a study programme leader must advise both upwards and downwards in an organisation. However, the next leadership level makes the final decisions. Study programme leaders, therefore, seem to have limited space to work independently. Alvesson et al. (Citation2017) suggest that such a lack of autonomy and power can limit a leader's ability to make quick decisions when needed. Therefore, we assume that decision-making processes will require extended time in study programme leadership. Although we emphasise that descriptions of power are lacking in the mandates, we argue that this may be intentional. This means that mandates are not meant to be fixed directives but dynamic spaces that open a space for actions. Thus, we also advocate further explorations of the power that study programme leaders are assigned at individual institutions or locally in particular study programmes.

Another finding implies that study programme leadership is controlling, based on verbs such as secure, ensure, monitor, put in place, and report. Using Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) framework as a lens entail that these verbs indicate a vertical mode of organisation, i.e., management, through impersonal structures, systems, and formal obligations. Our findings demonstrate that study programme leadership is expected to focus on the following rules: exercising control and reporting. Hence, study programme leadership implies accountability and top-down management. Based on this, we can say that a management logic lays premises for study programme leadership. This management thinking can also be identified in our findings of coordinating and advising. For example, in coordinating, a central work task is to coordinate the daily operations of a study programme, such as timetable management. Given our previous descriptions, it follows that these leaders must perform management vertically and horizontally. However, this must be accomplished without the power to follow up, beyond quality assurance and coordination.

It is well described that study programme leadership is framed by a high administrative workload (Aamodt et al., Citation2016; Mitchell, Citation2015; Stensaker et al., Citation2018), which is also expressed as “bureaucratic burdens” (Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013, p. 41). Moreover, studies state that political quality reforms in HE is often influenced by NPM ideology, resulting in excessive bureaucracy and control regarding, for example, implementations of performance-based funding and quality education systems (Johansen, Citation2020; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013; Stensaker et al., Citation2018). In light of this, our findings describing controlling are not surprising, but our identification of the numerous administrative work tasks in the mandates shows that institutions consider management essential. The extant literature also underlines that management is necessary for planning and controlling organisational activities (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). For example, quality assurance is an expected part of a study programme leader's responsibilities (Stensaker et al., Citation2018; Vilkinas & Ladyshewsky, Citation2012). In Mitchell's study, (Citation2015) administration and paperwork completion are also described as helpful for ensuring educational quality. Moreover, establishing quality assurance routines is requisite to handle an increasingly large student body and complex study programmes while preventing fragmentation and inadequate student progression (Solbrekke & Stensaker, Citation2016). This aligns with our findings and shows that the control of study programmes is meant to ensure a coherent programme.

Although management-oriented study programme leadership may be necessary at times, its implications are notable. According to Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017), understanding, a study programme leadership that emphasise management logic can ultimately prioritise checklists rather than the relational processes that involve a professional community's knowledge and ideas. Furthermore, interestingly, Johansen (Citation2020) found that NPM can affects leaders’ thinking and practice without them being aware of it. The same study indicates that control-based, instrumental thinking can challenge fundamental HE values, such as trust and collegiality, and provide limited space for development work. An NPM logic in study programme leadership can therefore be a barrier to enhancing educational quality (Johansen, Citation2020). These findings align with Alvesson et al.s’ (Citation2017) management descriptions, which entail that rule-based work must be considered meaningful to provide positive results to both leaders and followers. Therefore, they suggest that management should be combined with other modes of organising, such as leadership. Accordingly, horizontal modes, such as group work and peer influence, are also important for study programme leadership not to be dominated by controlling.

In addition, our findings suggest that study programme leadership is complex and consists of more than management. If we take a closer look at the verbs contribute, stimulate, facilitate, be a driving force for and initiate, they point leaders in another direction, which we call facilitating. Here, a strong emphasis is placed on the leadership that can drive pedagogical processes forwards. Facilitating emphasises interaction, dialogue, and relationship building. Thus, our findings turn toward Alvesson et al.’s (Citation2017) perspective on leadership. Moreover, our findings related to facilitating also show that study programme leaders are responsible for developing an educational culture where teachers and students feel a sense of belonging. These also calls for leadership (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). In contrast to management, which emphasises controlling, we are now pointing to leadership represented by trust-building exercises, discussions, and other actions that can provide a direction and meaning among people in an organisation. Thus, Mårtensson and Roxå (Citation2016) demonstrate that study programme leadership, following Alvesson et al. (Citation2017), is crucial to the development processes at the study programme level. Mitchell (Citation2015) also affirms that this kind of study programme leadership is particularly necessary to navigate difficult times.

Based on the previous discussion on management, we can assume that dilemmas during the balancing of management and leadership logics, for example, when programme leaders must prioritise rule-following with facilitating development processes. To our knowledge, few studies have examined how study programme leaders experience their leadership positions. Further explorations of study programme leadership from the perspective of study programme leaders are thus needed.

Our findings show that the mandates emphasise horizontal modes of organising; we can identify both group work and peer influencing. Moreover, these horizontal modes seem to operate in combination with both management and leadership. A programme committee can be read as a kind of network-based peer influencing body, where the study programme leader is responsible for coordinating inputs and advice to control programme quality and facilitate developing processes. Group work with course coordinators is another example of a horizontal mode, which is, for example, considered essential to coordinating a study programme's learning outcomes and activities and its assessment forms. Moreover, our findings regarding facilitating show that study programme leaders are expected to find ways to stimulate academic fellowship to foster engagement in programme development. Horizontal group work can contribute to this, since group work entails that members are in an equal relationship and participate in discussions at the same level. Group members can agree on a shared understanding and direction, which can be sufficiently powerful to influence and effect change (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). On the other hand, it can be challenging to establish a group that functions well. Conflicts of interest often arise in a group, and members may become more concerned with protecting their own interests than with working towards a common goal (Alvesson et al., Citation2017). According to Cahill et al. (Citation2015), study programme leaders will perceive such challenges, especially when there is disagreement in a group and decisions must be made to progress. Therefore, as previously described, we can assume that facilitating and coordinating group work without any decision-making power can lead to dilemmas in study programme leadership.

Finally, we want to highlight our finding that study programme leadership is coordinating. Study programme leadership functions as a nexus for development processes that involve many actors. This indicates that leadership that emphasises collaboration, dialogue, and collegiality is needed. These aspects of leadership are consistent with prior studies (Cahill et al., Citation2015 Johansen, Citation2020; Mårtensson & Roxå, Citation2016; Murphy & Curtis, Citation2013;). Therefore, we suggest that study programme leadership needs to be performed through horizontal work that emphasises team-based and collegial processes. Moreover, as Stensaker et al. (Citation2019) argue, study programme leaders have a critical coordinating responsibility, because these leaders (…) “are a connection point between pedagogical work and the organisational context in which study programme leaders operate in.” Our findings show that the mandates foster both horizontal and vertical coordination. However, we also support Stensaker et al.s’ (Citation2019) recommendation for future research on whether study programme leaders themselves are aware of how important their coordinating roles are.

Methodological considerations

Document analysis is usually one of several methods in a research study. However, it can be an authoritative “stand-alone method” in qualitative interpretive studies akin to the present study, which conducted a hermeneutic analysis of the institutions’ mandates (Bowen, Citation2009, p. 29). We consider it a strength that data (mandates) are selected from both universities and university colleges. Furthermore, 14 of 16 relevant institutions are included in the material. Finally, the selected mandates are recent (2020), and the relevant institutional boards approved the mandates before they were published in the quality system.Footnote2

In this study, the data (mandates) are selected from Norwegian HE institutions that offer health profession study programmes. However, the selection process revealed that the mandates for study programme leadership are generic for all HE study programmes and not specific to health profession study programmes. Based on this, we can argue that our findings are transferable to study programme leadership in general. Nevertheless, our findings have limitations since we have not included all HE institutions in Norway.

The lack of dialogue with the authors of the mandates may be considered a limitation. However, this study aimed to describe and explore study programme leadership as it appears in these institutional mandates. Therefore, our research contributes insights and knowledge about how institutions frame this leadership. Inspired by Ricoeur (Citation1991b) we are able to divide author intention from a text's verbal meaning. This division allows us, as readers, to interpret a text without focusing on author intention. Hence, we can describe and explore the phenomenon of study programme leadership as it appears in the mandates.

In this study, we chose a qualitative design and a hermeneutical analysis approach that emphasises subjective interpretations and a quest for meaning and understanding rather than objectivity and independence (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2018; Ricoeur, Citation1991a). According to Alvesson and Sköldberg (Citation2018), reflexivity means awareness of how our background and preconception affect our research. This is described as the researcher's continuously questioning his stance vis-à-vis his empirical material, analysis, and theorising. Moreover, it implies that through the research process, we must be able to, again and again, ask ourselves questions such as ‘Why? Why if?’ (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2018; Gabriel, Citation2017). In this study, the entire research group were actively involved in all the parts of the research process. The research group also participated in critical reflection and discussion throughout the analysis to ensure reflexivity and varied analytical perspectives. Additionally, the research group is interdisciplinary, which we consider a strength to ensure reflexivity thorough the discussions in the research process. Furthermore, we have described the analysis in detail to ensure transparency and trustworthiness. However, the function of reading is interpretation (Alvesson & Sköldberg, Citation2018; Ricoeur, Citation1991b). Readers can thus interpret the mandates subjectively based on their preunderstandings. In other words, this can lead to alternative interpretations. Accordingly, it could be interesting to further explore how study programme leaders interpret these mandates and what implications such interpretation has for leaders’ daily work, for example within health profession study programmes.

Conclusion

This study contributes new knowledge by describing how HE institutions express their expectations to study programme leaders’ work tasks and responsibilities. By analysing the verbs in study programme leaders’ mandates, we identified divergent aspects of study programme leadership, i.e., controlling, facilitating, coordinating, and advising. Our discussion builds on elements from Alvesson et al.'s (Citation2017) framework to illustrate how diverse modes of organising are reflected in our interpretation of the mandates. Interestingly, power and autonomy are mostly absent from the mandates. Moreover, we found that study programme leadership extends from a management that focuses on control to a leadership based on trust. Although management through control is emphasised, we found that leadership combining horizontal peer influence and group work is highlighted, thus leadership primarily relates to facilitating development processes and contributing to a good learning culture. Study programme leadership is therefore likely pedagogically oriented and extends beyond quality assurance. Furthermore, our findings verify that study programme leadership is a crucial nexus of vertical and horizontal processes and of the different actors involved in study programmes in HE.

Study programme leaders are expected to undertake a complex range of sometimes conflicting activities, and our analysis provides new insights regarding these by revealing the tensions among the various leadership actions constructed in the mandates. Although the mandates do not describe how to practically resolve these dilemmas, we can imagine that study programme leadership can be challenging.

Finally, although there is a growing interest in the field, more knowledge about study programme leadership in HE is needed. Specifically, there is a lack of research that focuses on how leadership is experienced by study programme leaders. Therefore, we recommend that future research explores study programme leadership from this perspective.

Acknowledgements

We want to thank our colleague Hans Martin Lilleby, Norwegian University of Science and Technology (NTNU), Department of Health Sciences in Gjøvik, who has given technical support with the design of the figures.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 16 institutions were initially identified as relevant participants, but 2 institutions were excluded as they did not offer open access to their quality systems.

2 We did not need the ethical approval of Norwegian Social Science Data Services (NSD) since the study did not include personal data.

References

- Aamodt, P. O., Hovdehaugen, E., Stensaker, B., Frølich, N., Maassen, P., & Dalseng, C. F. (2016). Utdanningsledelse: En analyse av ledere av studieprogrammer i høyere utdanning [Educational leadership: An analysis of leaders of study programs in higher education]. NIFU Nordisk institutt for studier av innovasjon, forskning og utdanning [Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education].

- Alvesson, M., & Blom, M. (2019). Beyond leadership and followership: Working with a variety of modes of organizing: Working with a variety of modes of organizing. Organizational Dynamics, 48(1), 28–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2017.12.001

- Alvesson, M., Blom, M., & Sveningsson, S. (2017). Reflexive leadership: Organising in an imperfect world. Sage.

- Alvesson, M., & Sköldberg, K. (2018). Reflexive methodology: New vistas for qualitative research (3rd ed). SAGE.

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Bryman, A. (2007). Effective leadership in higher education: A literature review. Studies in Higher Education, 32(6), 693–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070701685114

- Buller, J. L. (2013). Positive academic leadership. How to stop putting out fires and start making a difference. Jossey-Bass.

- Cahill, J., Bowyer, J., Rendell, C., Hammond, A., & Korek, S. (2015). An exploration of how programme leaders in higher education can be prepared and supported to discharge their roles and responsibilities effectively. Educational Research, 57(3), 272–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131881.2015.1056640

- Forskrift om tilsyn med utdanningskvaliteten i høyere utdanning (Studietilsynsforskriften) FOR-2017-02-07-137. (2017). Regulations on supervision of the quality of education in higher education. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from, https://lovdata.no/dokument/SF/forskrift/2017-02-07-137

- Gabriel, Y. (2017). Interpretation, reflexivity and imagination in qualitative research. In M. Ciesielska & D. Kozminski (Eds.), Qualitative methodologies in organization studies (Vol. 1 Theories and New Approaches, pp. 137–157). Springer Nature.

- Gibbs, G., Knapper, C., & Piccinin, S. (2008). Disciplinary and contextually appropriate approaches to leadership of teaching in research-intensive academic departments in higher education. Higher Education Quarterly, 62(4), 416–436. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00402.x

- Grepperud, G., Danielsen, Å, & Holen, F. (2017). Ledelse av studieprogrammer. Erfaringer og utfordringer. [Leadership of study programmes. Experiences and challenges].

- Helseth, I. A., Alveberg, C., Ashwin, P., Bråten, H., Duffy, C., Marshall, S., Oftedal, T., & Reece, R. I. (2019). Developing educational excellence in higher education. NOKUT – The Norwegian Agency for Quality Assurance in Education.

- Irving, K. (2015). Leading learning and teaching: An exploration of ‘local’ leadership in academic departments in the UK. Tertiary Education and Management, 21(3), 186–199. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-65217-7

- Johansen, M. B. (2020). Studieprogramledelse i høyere utdanning: i spenningsfelt mellom struktur og handlingsrom [Study program leadership in higher education: In tension between structure and agency]. Norwegian University of Science and Technology.

- Mårtensson, K. (2014). Influencing teaching and learning microcultures [Doctoral dissertation]. Lund University.

- Mårtensson, K., & Roxå, T. (2016). Leadership at a local level – Enhancing educational development. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 44(2), 247–262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143214549977

- Mitchell, R. (2015). ‘If there is a job description I don’t think I’ve read one’: A case study of programme leadership in a UK pre-1992 university. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 39(5), 713–732. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.895302

- Murphy, M., & Curtis, W. (2013). The micro-politics of micro-leadership: Exploring the role of programme leader in English universities. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 35(1), 34–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2012.727707

- QSR International. (2020). Nvivo qualitative data analysis (Version 20.3.0.535). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Ramsden, P., Prosser, M., Trigwell, K., & Martin, E. (2007). University teachers’ experiences of academic leadership and their approaches to teaching. Learning and Instruction, 17(2), 140–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.004

- Rasmussen, S. B. (2014). Potentiale ledelse. Om strategisk ledelse i fagprofessionelle organisationer [Potential leadership. About strategic leadership in professional organizations]. Barlebo Forlag.

- Ricoeur, P. (1991a). From text to action: Essays in hermeneutics, II. Northwestern University Press.

- Ricoeur, P. (1991b). What is a text. In P. Ricoeur (Ed.), From text to action: Essays in hermeneutics, II (pp. 105–124). Northwestern University Press.

- Sahlin, K., & Eriksson-Zetterquist, U. (2016). Collegiality in modern universities - The composition of governance ideals and practices. Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy, 2016(2–3), 1–10 . https://doi.org/10.3402/nstep.v2.33640

- Solbrekke, T. D., & Stensaker, B. (2016). Utdanningsledelse - stimulering av et felles engasjement for studieprogrammene? [Educational leadership - Stimulating a collective engagement to the study programs?]. Uniped [elektronisk ressurs]: tidsskrift for universitets- og høgskolepedagogikk, 39(2), 144–157.

- Stensaker, B., Elken, M., & Maassen, P. (2019). Studieprogramledelse – et spørsmål om organisering? [Study program management - a question of organization?]. Uniped, 42(01), 91–105. https://doi.org/10.18261/issn.1893-8981-2019-01-07

- Stensaker, B., Frølich, N., & Aamodt, P. O. (2018). Policy, perceptions, and practice: A study of educational leadership and their balancing of expectations and interests at micro-level. Higher Education Policy, 2020(33), 735–752. doi:10.1057/s41307-018-0115-7

- Vilkinas, T., & Ladyshewsky, R. K. (2012). Leadership behaviour and effectiveness of academic program directors in Australian universities. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 40(1), 109–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143211420613

- White Paper 16 (2016-2017). (2017). Kultur for kvalitet i høyere utdanning [Quality culture in higher education]. Ministry of Education and Research.