Abstract

Altered childbearing behaviour has been observed in many settings of violent conflict, but few studies have addressed fertility control. This is the first study to investigate empirically the relationship between local conflict and uptake of sterilization, the only contraceptive method that reflects a definitive stop to childbearing. The study is based on Colombia, a middle-income, low-fertility, and long-term conflict setting. It builds on a mixed methods approach, combining survey and conflict data with expert interviews. Fixed effects regressions show that local conflict is generally associated with an increased sterilization uptake. The interviews suggest that women may opt for sterilization when reversible methods become less accessible because of ongoing violence. Since sterilization is a relatively available contraceptive option in Colombia, it may represent a risk-aversion strategy for women who have completed their fertility goals. These findings can enlighten research and programmes on fertility and family planning in humanitarian contexts.

Introduction

Since the Second World War, altered fertility behaviour has been observed in many settings of armed conflict. The results have been mixed, suggesting both positive and negative effects on childbearing (Lindstrom and Berhanu Citation1999; Agadjanian and Prata Citation2002; Blanc Citation2004; Woldemicael Citation2008, Citation2010; Schindler and Brück Citation2011; Van Bavel and Reher Citation2013; Cetorelli Citation2014; Islam et al. Citation2016; Verwimp et al. Citation2020; Castro Torres and Urdinola Citation2018; Torrisi Citation2020). Proximate determinants of fertility, such as family planning, have gained less attention in empirical research. Observing women’s fertility control during conflict may indicate how a violent social context shapes both reproductive autonomy and fertility desires.

Two previous studies have directly measured exposure to armed conflict violence in order to understand fertility control responses, in settings that vary considerably in terms of contraceptive and conflict profiles. During the Nepalese civil war 1996–2006, uptake of first contraception increased in relation to violent and political events of conflict (Williams et al. Citation2012). In Colombia, exposure to local conflict was linked to a decrease in the use of short- and long-term reversible modern contraception, partially reflecting increased fertility demand but possibly also a reduction in access to contraception due to health system failure (Svallfors and Billingsley Citation2019).

Whereas use of other modern contraceptive methods may reflect changes in postponement, spacing, or stopping, women’s sterilization (hereafter called sterilization; men’s sterilization is referred to as vasectomy) is the only contraceptive method that reflects a definitive and virtually irreversible stop to fertility. This study is the first to explore stopping behaviour during conflict, by measuring how local violence relates to the uptake of sterilization. This is done for the case of Colombia, a middle-income country where contraceptive knowledge is well established and contraceptive use generally socially accepted. Sterilization is the most common family planning method, but past literature has studied only the use of reversible methods (Svallfors and Billingsley Citation2019), an approach that omits an important part of family planning decisions and opportunities during war.

The study focuses on Colombia, which is a useful case study for four primary reasons. First, Colombia has a unique history of long-term conflict, ongoing since the 1960s, with extensive tempo-spatial variation in conflict violence intensity. Second, women’s experiences from war were given an unprecedented focus in the Havana peace accords adopted in 2017 between the Colombian government and the left-wing guerrilla group FARC (las Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia—Ejército del Pueblo; the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia—People’s Army) (Salvesen and Nylander Citation2017; Gindele et al. Citation2018), but there is still little research about how war has affected women’s reproductive health and rights. Third, analysing Colombia helps us to understand better the relationship between war and family planning in a replacement-fertility context (Colombia’s total fertility hovers around two children per woman on average (DHS Citation2017)), whereas much of the existing literature has focused on high-fertility settings. Fourth, Colombia is one of the few settings where collection of nationally representative survey data has continued virtually uninterrupted despite ongoing conflict.

Relationships between conflict and sterilization uptake

Uptake of sterilization, as a means of fertility control, may be linked both positively and negatively to armed conflict, and uptake may be either voluntary or coerced. The combinations of these yield four separate hypotheses for the study, as outlined next.

Hypothesis 1: Reduced demand for sterilization

Hypothesis 1 suggests that the voluntary uptake of sterilization declines in armed conflict.

Conflict tends to increase mortality, including infant and child mortality (O’Hare and Southall Citation2007; Elveborg Lindskog Citation2016). Losing family members may lead to a substitution effect by which women want to have more children (Rutayisire et al. Citation2013), hence reducing the demand for sterilization.

Women’s demand for sterilization may also decrease if sexual unions are interrupted. Men’s morbidity, mortality, and migration related to conscription in conflict could disrupt unions, strengthen fertility intentions, or increase the urgency to have a child. In violent areas women’s fertility trajectories may be altered in anticipation of the violent death of a partner (Jok Citation1999; Navarro Valencia Citation2009). Repartnering is often linked to parity progression to ‘confirm’ the relationship (Vikat et al. Citation1999; Schmeer and Hays Citation2017). Women who anticipate repartnering due to partner loss may avoid sterilization to enable future childbearing (Bumpass et al. Citation2000; Godecker et al. Citation2001). Childbearing across partnerships may follow a ‘marriage squeeze’ due to conflict-driven excess mortality among men (Jones and Ferguson Citation2006).

Evidence from Colombia suggests a positive fertility response to local violence in rural areas during 2000–10, possibly reflecting higher mortality levels and reduced access to healthcare and protection (Castro Torres and Urdinola Citation2018). Past research has also shown a remarkable stability in fertility preferences despite local violence (Svallfors Citation2020). Svallfors and Billingsley (Citation2019) found that conflict reduced the probability of using reversible modern contraception, partially because women wanted more children soon, which may reflect a replacement effect or union uncertainty. But they noted it was also likely that healthcare system deterioration decreased access to contraceptive goods.

Hypothesis 2: Increased demand for sterilization

Hypothesis 2 suggests that the voluntary uptake of sterilization increases in armed conflict.

Women faced with conflict may want to be sterilized instead of using reversible contraception so that they can definitely and permanently stop childbearing because of deteriorating social conditions, such as losses of security, certainty, economic opportunities, family, relationships social support, etc. (Speizer Citation2006; Calderón et al. Citation2011; Chi et al. Citation2015a, Citation2015b). This does not, however, necessarily reflect a change in women’s childbearing preferences (Svallfors Citation2020).

In contexts of protracted violence, poverty, and gender inequality, sterilization can be an instrument for reducing the risk of additional births and can be seen as a grasp for control in a position of vulnerability (Dalsgaard Citation2004), not least since predicting access to healthcare, as well as the costs and benefits of children, may be more difficult due to the threat of harm and instability (Montgomery Citation2000; Rangel et al. Citation2020). Women may opt for sterilization to avoid unintended births if access to reversible contraception becomes more unstable (Svallfors and Billingsley Citation2019); this has been linked to post-partum uptake of long-term and permanent contraceptive methods in Colombia (Batyra Citation2020). Exposure to conflict-related sexual violence has been substantial in Colombia (Kreft Citation2020) and may also create a demand for sterilization. When choosing between different contraceptive methods, sterilization may be perceived as the most reliable option in an otherwise uncertain situation.

The evidence from psychological and economic research on risk preferences after political and natural catastrophes is mixed, suggesting both risk-averse responses (Sacco et al. Citation2003; Cameron and Shah Citation2014; Kim and Lee Citation2014; Cassar et al. Citation2017) and risk-tolerant ones (Eckel et al. Citation2009; Voors et al. Citation2012). Post-crisis risk preferences tend to vary by sex, with men being more risk tolerant and women more risk averse (Weber et al. Citation2002; Lerner et al. Citation2003; Hanaoka et al. Citation2018). Women’s contraceptive choices could thereby reflect a risk-averse response to violent conflict.

Health system failures may occur during conflict if resources are relocated to military expenses (O’Hare and Southall Citation2007) or because of damaged infrastructure, limited human resources, weak management, increased difficulties in coordination among non-governmental organizations (Iqbal Citation2010; McGinn et al. Citation2011), and direct attacks on healthcare professionals, facilities, and shipments (Franco et al. Citation2006; ICRC Citation2011). If women’s access to healthcare and reversible contraception diminishes, they may opt for sterilization, which requires only one visit to a healthcare facility. The same may follow if women’s economic prospects worsen, since conflict tends to create poverty traps (Ibáñez and Moya Citation2010).

Previous literature shows support for an increase in overall fertility control due to conflict. According to Potter et al. (Citation1976), the rapid fertility transition in Colombia during the 1960s may have been driven by conflict-related migration from rural to urban areas. Williams et al. (Citation2012) found that exposure to conflict had a positive effect on uptake of first contraception in Nepal, attributed to a decreased desire for children. Evidence from sub-Saharan Africa indicates that women want to take up contraception if it is made available in conflict or post-conflict environments (Casey et al. Citation2013; Orach et al. Citation2015; Casey and Tshipamba Citation2017).

Hypothesis 3: Involuntary decline in sterilization; and Hypothesis 4: Increase in coerced sterilization

Hypothesis 3 postulates an involuntary decline in sterilization uptake, while Hypothesis 4 suggests an increase in coerced sterilization. The mechanisms behind why we might expect reductions in women’s reproductive autonomy in a way that affects sterilization either positively or negatively are largely the same for both directions of the relationship, except that the reduced access to healthcare already described may also create an involuntary decline in uptake if women cannot choose sterilization as their preferred method.

Multiple forms of gender-based violence (GBV) tend to increase in war (Wirtz et al. Citation2014; La Mattina Citation2017; Østby et al. Citation2019; Kreft Citation2020; Svallfors Citationforthcoming). GBV is strongly associated with reproductive events, such as contraceptive discontinuation, parity progression, unwanted pregnancy, miscarriage, and induced abortion (Kishor and Johnson Citation2004; Cripe et al. Citation2008; Gomez Citation2011; Pallitto et al. Citation2013). GBV has been linked to a reduced use of reversible contraception in Colombia (Svallfors and Billingsley Citation2019). It could, thus, affect sterilization uptake positively or negatively through reductions in women’s reproductive autonomy: positively if women are forced to undergo the procedure (Hypothesis 4), or negatively if women are hindered by partners or others from choosing sterilization when it is their preferred method (Hypothesis 3).

Sterilization in Colombia and elsewhere has not always been well informed or voluntary (Rizo and Roper Citation1986; Hollerbach Citation1989; Folch et al. Citation2017; Jadhav and Vala-Haynes Citation2018). Although eugenic sterilization practices have largely ceased, forced and coerced sterilizations are still performed in many parts of the world, targeting ethnic minorities, the disabled, and HIV-positive people (Miranda and Yamin Citation2004; Zampas and Lamačková Citation2011; Asdown Colombia Citation2013; CDR Citation2014; Kendall and Albert Citation2015; Reilly Citation2015). In Colombia, female soldiers in the FARC ranks have reported forced sterilization as a measure of reproductive control in exchange for participating in the guerrilla group (Herrera and Porch Citation2008). Forced sterilization is one form of GBV that could increase in tandem with other forms of abuse against women.

Sterilization in Colombia

Sterilization has played an important part in the development of family planning programmes in Colombia. It was considered illegal and immoral in most countries until 1969, when Singapore and the US state of Virginia introduced the first non-eugenic, non-restrictive laws. During the 1970s, sterilization programmes were introduced worldwide through national family planning initiatives, often motivated by high levels of fertility and maternal mortality. Sterilization was portrayed as a good option for women in settings with low access to reversible contraception (Nortman Citation1980). It was first introduced in Colombia in 1972 by the private, non-profit family planning organization Profamilia, when two medical doctors were sent to train in the US. This initiative followed the introduction of a vasectomy programme two years earlier. Both were widely available but especially aimed at the poor as a cost-effective and permanent form of avoiding unwanted pregnancies. While religious, medical, and target group opposition hindered the success of the vasectomy programme, the uptake of sterilization grew high (Hollerbach Citation1989; Williams et al. Citation1990).

The Colombian government sponsored its first free-of-charge sterilization programme in 1979, largely as a response to the high maternal mortality rate. The programme explicitly targeted women at risk of high-risk pregnancies in terms of both morbidity and mortality. A points system was introduced through which factors such as a woman’s age, number of children, pregnancy intervals, nutritional status, and number of people in the household determined her risk level. Women needed to be at least 25 years old and have at least three living children to be eligible. Women at lower or medium risk were instead offered reversible methods. Colombia’s then 1,200 rural health centres and 800 local hospitals referred eligible women to one of the country’s 108 regional hospitals, where obstetricians, surgeons, and operating room nurses newly trained by Profamilia performed outpatient laparoscopic sterilization (Guttmacher Citation1979; Rizo and Roper Citation1986).

The sterilization rate among fecund married women was estimated to be 16 per cent in 1982 (Trias et al. Citation1987) and 18.3 per cent as of 1986, at that point becoming the most frequently used method in Colombia (Hollerbach Citation1989). Profamilia provided 599,018 sterilizations to women between 1972 and 1988, compared with only 19,590 vasectomies (Williams et al. Citation1990). By 1986, 19 per cent of women in Colombia had been sterilized, with this method representing one-third of all contraceptive use (Rutenberg and Landry Citation1993). Between 1977 and 1995, the share of women who had been sterilized rose from 6 to 37 per cent (Parrado Citation2000). By the mid-1990s, sterilization was the most common contraceptive method in the whole of Latin America. Among fecund married women aged 20–45 in Colombia, about 16 per cent used sterilization, compared with 10 per cent in Peru and 40 per cent in Brazil and the Dominican Republic. All else being equal, among Colombian women aged 20–29 or above 40 the propensity to undergo sterilization was lower than for those aged 30–34. Uptake increased with number of children and was highest for those who had been married for five to nine years compared with shorter and longer marriage durations. There was no statistical difference between urban and rural women (Leite et al. Citation2004). Leite and colleagues also observed that in the mid-1990s women with higher levels of education were more prone to becoming sterilized, whereas Folch et al. (Citation2017) found that women of lower educational and wealth levels in 2005 and 2010 were more likely to undergo sterilization than to use reversible long-acting methods. The difference between these two studies could be due to different sample selections of the population at risk and does not necessarily indicate a period change.

From the outset, the private and public sterilization programmes in Colombia specifically targeted poor women (Guttmacher Citation1979), and observed differences have led to allegations of coercive sterilization, particularly among disadvantaged groups such as the young, the poor, rural women, and Afro-Colombian or Indigenous women (Folch et al. Citation2017). Since those groups were also more affected by local conflict, it is probable that their uptake of sterilization differed from that of more affluent women with respect to conflict exposure as well as access to healthcare.

Conflict dynamics in Colombia

Colombia has experienced an unusually long-standing internal armed conflict since 1964, involving the government, paramilitary groups, organized crime groups, and left-wing guerrillas, such as the FARC mentioned earlier and el Ejército de Liberación Nacional (ELN, the National Liberation Army).

The conflict has its roots in a decade-long unofficial civil war known as La Violencia, which started in 1948 over ownership, clientelism, corruption, and socio-economic inequality dating back to colonial times. Responding to a governmental vacuum in remote geographic areas, the existence of clientelism and socio-economic injustices, and the exclusion of other political views, various left-wing guerrilla movements were born in the mid-1960s. During the 1970s drug trafficking emerged in Colombia as an economic alternative to rising poverty, political corruption, and insufficient public services. Left-wing guerrillas turned to drug trafficking, extortion, and kidnapping for economic and political purposes. In the 1980s, large landowners and drug traffickers created their own right-wing paramilitary groups. Most of these groups were part of las Autodefensas Unidas de Colombia (AUC, the United Self-Defence Forces of Colombia) until it disbanded in 2006. The conflict has grown more complex over time because of state corruption and illegitimacy, protracted socio-political instability and intolerance, widespread drug trafficking, and judicial impunity (De Roux and Francisco Citation1994; Bergquist et al. Citation2001; Jansson Citation2008).

Widespread violence—in the forms of homicide, disappearances, forced displacements, use of anti-personnel mines, and kidnapping—has gravely affected the Colombian people (Franco et al. Citation2006; Alzate Citation2008). Colombia’s overall mortality level has long been the highest in the Western hemisphere, due to conflict (Garfield and Llanten Morales Citation2004). More than 3,600,000 Colombians were forcefully displaced during 1985–2005, half of whom were younger than 18 years. Over the 1975–2004 period, 554,008 homicides were committed in Colombia, representing a mean of one homicide every half an hour and 10–15 per cent of the total mortality rate. Homicide rates vary significantly across the regions of the country, reflecting the level of regional state presence (Franco et al. Citation2006). The Colombian armed conflict has, in other words, been tremendously detrimental to the health of the population.

Mixed methods rationale

This study used a mixed methods approach to generate a more comprehensive understanding of sterilization uptake during the Colombian armed conflict. The use of mixed methods provides strengths that offset the respective weaknesses of qualitative and quantitative methods, offers a wider choice of data collection methods, helps to answer research questions that cannot be answered with only one method, and increases the validity of the study. In the case of contraceptive uptake, quantitative analyses of survey data are appropriate for identifying general patterns at the population level and statistical relationships net of confounding factors, while qualitative interview material is useful for creating a richer understanding of why these relationships exist. I used an explanatory sequential approach: the quantitative models were developed first, after which interviews were conducted to contextualize and interpret the results (Tembo Citation2014; Curry and Nunez-Smith Citation2015; Tashakkori and Teddlie Citation2016). This is also the order in which the two components are presented next.

Quantitative methods

Two sets of data were combined in this study to address the uptake of sterilization during the Colombian armed conflict quantitatively.

First, six pooled rounds of the Colombian Demographic and Health Survey (DHS) conducted every fifth year from 1990 to 2015 offer long-term information on women’s reproductive behaviour and characteristics. The sample is nationally representative of Colombia’s female population aged 13–49, with response rates above 86 per cent in all rounds. The sampling has included all regions and departments of Colombia since 2005, but the first three rounds excluded the island department San Andrés y Provincia in the Caribbean and departments in the Amazonía and Orinoquía regions. Women aged 15–49 were sampled for interview in all survey rounds, and since 2005 women aged 13–14 have also been included. DHS data are primarily cross-sectional, but some indicators may be used longitudinally (DHS Citation1991, Citation1995, Citation2000, Citation2005, Citation2011, Citation2017). As in other studies of war-affected populations, there is likely a survivorship bias in the DHS sample, due to mortality, emigration, and internal displacement. This could lead to misestimation of effects since the worst-off women are not in the sample.

Second, the Uppsala Conflict Data Program Georeferenced Event Dataset (UCDP-GED) contains information for 1989–2017 about events of violent conflict in which at least one person was killed, including when and where each event occurred and an estimation of how many casualties there were. The information is based on sources such as news media, reports, and books (Sundberg and Melander Citation2013; Croicu and Sundberg Citation2017). The data do not account for all homicides, but include violence perpetrated by the organized crime groups that have played an important role in the Colombian conflict.

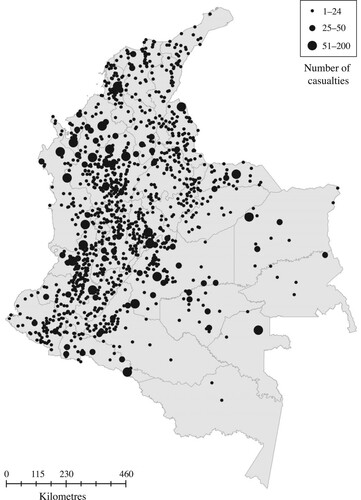

The geography of violence in Colombia is illustrated in . It shows that some departments have been severely affected by conflict, whereas others have not.

Figure 1 Prevalence of conflict events across Colombia, 1989–2016

Note: Each dot is an event and a bigger size indicates more casualties in that event. Events in 2017 (n = 9) were excluded because they could not be linked to DHS data.

Source: Author’s analysis of UCDP-GED data.

The data sets were combined spatially by the lowest geographical level available in all survey rounds: the department where the respondent resided and the conflict events occurred. Events without information on monthly timing (n = 42), events without information about administrative unit (n = 217), and events in 2017 (n = 9) were dropped, since they could not be linked to the DHS data. In total, 2,515 out of 4,309 valid observations were matched to sampled women.

Dependent variable

The outcome variable was women’s month of sterilization at any time between age 13 and their interview. Women were asked whether they had undergone an operation to avoid childbearing and to recall the month and year of the operation. This information may suffer from recall bias, especially among older women who underwent the procedure many years ago, but recall is aided by the interviewers asking women about their birth histories.

Independent variables

The independent variables in this study captured department-level violence related to armed conflict. Departments were the finest geographical level available in the DHS across all waves of data. Each woman-month was matched to conflict exposure in the woman’s department of residence during observation. Since there is no a priori standard to guide how conflict is measured, a data-driven approach was used. Numerous specifications for conflict were tested to explore the relationships with sterilization uptake: functional form (continuous, categorical, or dummy measures), aspect of conflict (casualties or events), and temporality (three-, six-, twelve-, and 24-month time lags). Coefficients, p-values, and Akaike information criterion (AIC) tests were used to assess indicator performance. The focal independent variables measured conflict continuously as the number of events, with all four time frames of conflict included in the main models.

Model and sample

A discrete-time model is useful for estimating the time-specific risk of an event (sterilization) in relation to a social phenomenon (conflict) when these occur grouped in time, in this case at month level. Since the dependent variable was measured dichotomously (either a woman was sterilized or she was not), linear probability regression models were used. Linear models were preferred over logit models to enable comparisons across models (Mood Citation2010). The unit of analysis was woman-months.

Observation started in January 1991 to enable measurement of conflict exposure in the preceding 24 months. Women were included in the sample from the age of 13. To assign exposure correctly, respondents were observed only from when they moved to their current residence, since the DHS does not offer information about where they had lived previously. Because this information is only available on a yearly basis, the observation began in January of the year following relocation. Women sterilized before observation were excluded from the analysis. The observation ended at the event, at age 49 or at interview; women sterilized after this time point were right-censored. This data structure created 11,648,913 woman-month observations from 113,403 women during the period 1991–2016.

The model estimated, for each month, whether a woman would ‘survive’ without being sterilized. Unlike other contraceptive methods, (successful) sterilization cannot generally be reversed for women, and in most cases there can be no discontinuation after method uptake. Transition into sterilization is therefore an absorbing state: uptake can only happen once in the life course.

Single-level regressions assume that women behave independently from one another, but this is not the case when observations of women within the same area are likely to be mutually dependent. Since exposure to conflict is not randomized in Colombia but is stratified by socio-geographic factors, the method used must consider variation within country subdivisions. I used a fixed effects linear regression and clustered standard errors to account for regional heterogeneity, using variation within clusters to generate estimates in a multilevel structure. The cluster variable department measured which of Colombia’s 33 departments the respondent resided in. The department-specific error term represented the effects of omitted department characteristics. This approach compensated for contextual omitted factors that could co-determine women’s uptake of sterilization and the magnitude of local violence. Fixed effects are advantageous over random effects, as the assumption of the latter is that the unobserved factors captured in the department-specific error term are independent of all the measured indicators (Stock and Watson Citation2008; Allison Citation2009; Angrist and Pischke Citation2009; Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal Citation2011).

Covariates

The models included relevant control variables that could be constructed as time-varying retrospectively. Year accounted for period changes. Respondents’ characteristics were represented by age; whether respondent was in education; level of education (approximated from in education, the age at which women would typically start and finish school in Colombia, and the highest level at interview); parity; and sex composition of children. Respondents’ type of place of residence (whether lived in an urban residence) at the time of interview was included, since women were observed only during the time they lived at their current residence.

Descriptive statistics

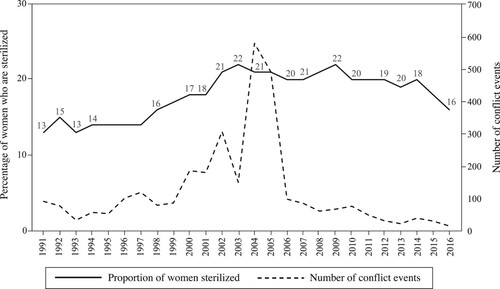

The share of the sample population that were using sterilization as their contraceptive method in each year during the observation period is illustrated in with a solid line (left-hand y-axis). It shows that the sterilization prevalence hovered around one-fifth or one-sixth of all women throughout the observation period, with a slight increase after the turn of the millennium. This information was retrieved from multiple pooled DHS rounds. The number of conflict events annually in Colombia is shown with a dashed line (right-hand y-axis). It displays how conflict was most intense in the early twenty-first century.

Figure 2 Share of women aged 13–49 who are sterilized and number of conflict events in Colombia, 1991–2016

Note: The solid line shows the proportion of women sterilized (left-hand y-axis); the dashed line shows the number of conflict events (right-hand y-axis). Observation starts in 1991 to allow for a 24-month time lag in exposure to conflict.

Source: Author’s analysis of DHS and UCDP-GED data.

Descriptive statistics of the sample population are displayed in . It shows both the prevalence of sterilization among women at risk and the incidence (number of sterilizations per woman-month). Around 19 per cent of women included in the sample had been sterilized at the time of interview, corresponding to sterilization occurring in 0.18 per cent of the sampled woman-months under observation. The study sample was predominantly young, urban, and of below-replacement parity, with secondary or lower education that was not ongoing at observation.

Table 1 Descriptive statistics of sample population: women aged 13–49 in Colombia

Summary statistics of women’s exposure to conflict are displayed in . With longer time lags the mean, standard deviation, and maximum values increase, but all four time frames include woman-months unexposed to conflict.

Table 2 Summary statistics of women’s exposure to conflict events

Around 45 per cent of women who had been sterilized had experienced the procedure in the same month as their last birth and around 60 per cent within two months after the birth, indicating that sterilization surgery is most often carried out immediately post-partum or shortly after. There was no differential pattern, however, of sterilization timing in relation to last birth between women who were exposed to zero, low, or high conflict. A department fixed effects linear regression of the amount of time between last birth and sterilization showed no significant relationship with exposure to violent conflict, suggesting that conflict does not affect the timing of sterilization in relation to last birth. Since past research has shown that conflict does not greatly impact overall fertility in Colombia (Castro Torres and Urdinola Citation2018), I did not investigate the link between birth and sterilization uptake further.

Substantial variation in both conflict and sterilization exists across Colombian departments, strengthening the case for a fixed effects model. At first glance, the patterns seem unrelated. For example, among sampled women in the more conflict-exposed departments, Cauca and Caquetá, shares sterilized were lower than average, while Valle del Cauca and Arauca’s were higher. Summary statistics on the population size and area of each department and also the distribution of women’s sterilization uptake and exposure to conflict across departments can be found in the supplementary material (Tables A1–A3).

Quantitative results

displays the key results from a large number of department fixed effects models that were run to evaluate the effect and model contribution of various indicators of armed conflict at the department level on the uptake of sterilization. Estimates for control variables are presented only for the first model, since their differences across models were infinitesimal.

Table 3 Department fixed effects linear probability models of women’s uptake of sterilization in relation to armed conflict in Colombia

Only the specifications measuring number of conflict events (for four different time frames) are statistically significant and hence are presented here. These indicators also contribute most to model fit according to AIC. The linear estimates of the effect of conflict events on uptake of sterilization are consistently positive and statistically significant, ranging from the highest probability of sterilization (0.000012 percentage points when measuring conflict events in the past three months; Model 1) to the lowest (0.000003 points for the past 24 months; Model 4) per conflict event for each woman-month. In other words, the effects are stronger when the extent of conflict is measured in the most recent period. This suggests that conflict does indeed alter women’s fertility choices and/or autonomy. It is possible that the negative mechanisms are still operative, but they are not stronger than the positive effect of conflict on sterilization. The social significance of these findings is discussed shortly using predicted probabilities.

Additional measurements of conflict, defined dichotomously, categorically, or continuously as number of deaths (as opposed to events), were consistently insignificant as the confidence intervals overlapped with zero. Those models are available on request. This suggests that neither the intensity of conflict in terms of fatalities, nor whether there were any deaths in the department, nor whether levels of conflict were zero, low, or high are statistically related to variation in women’s sterilization uptake within a region. This could reflect the fear of violence being more important than the magnitude.

Covariates are discussed for all models together since the differences were infinitesimal. Uptake of sterilization has increased over time (year variable) and is lower at the oldest and higher at the youngest ages. This unexpected finding for the youngest age group is due to controlling for whether the respondent was still in school and their educational level, since women’s educational careers are so closely related to age. When I excluded either or both education variables, the relationship was also negative for the youngest age group and the overall age pattern was inversely U-shaped, but the coefficients for violent conflict did not change (Table A4, supplementary material). There is no statistical difference between the reference group—women aged 24–29—and those aged 25–34.

Sterilization uptake is highest after parity two and with a mixed sex composition of children, confirming the hegemonic status of the ‘one-of-each’ two-child norm in Colombia. There seems to be no son preference in Colombia, but rather women tend to have one child of each sex before sterilization. Further, uptake is greater among urban residents, the highly educated, and those not currently in education, suggesting that women in higher socio-economic positions are more prone to become sterilized. These are arguably the most empowered groups of women, pointing towards an increase in the demand for sterilization after the goal of two children is met, rather than a reduction in women’s reproductive autonomy.

When parity was excluded from the model, the effect of whether the respondent was in education in that month changed direction, possibly because women in education have fewer children.

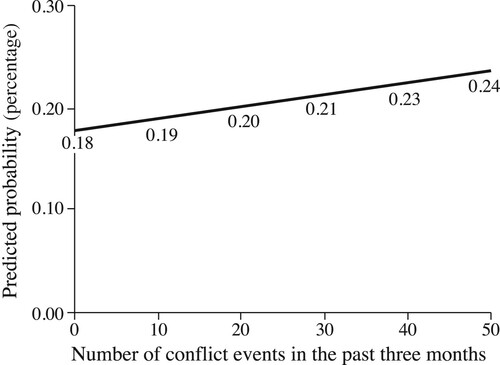

To assess the social significance of the relationship between sterilization and conflict, I calculated the predicted probabilities of becoming sterilized at each woman-month, fixed at different levels of exposure to violence in the past three months (). The predictive margins were derived from the linear probability model described earlier, adjusted for controls at their mean values. The predicted probability of sterilization is 0.18 per cent in woman-months unexposed to conflict, and 0.24 per cent in woman-months with the highest conflict exposure observed in the sample (50 events). The predicted probabilities for the other time frames for conflict events measured linearly (not shown) spanned similar ranges from minimum to maximum as the three-month time lag.

Figure 3 Predicted probabilities of becoming sterilized according to number of conflict events in the past three months, women aged 13–49 in Colombia, 1991–2016

Note: Observation starts in 1991 to allow for a 24-month time lag in exposure to conflict.

Source: As for .

These numbers may appear small at first glance, since they reflect the probability of sterilization in each month a woman is observed. But the results show that women exposed to the highest level of conflict are one-third more likely to become sterilized compared with those who are unexposed to conflict during observation (0.24 / 0.18 = 1.33). Because almost one-fifth of women in Colombia have undergone sterilization and this evidence shows that conflict may have been a driving factor for this contraceptive uptake, the findings are not socially insignificant.

The findings were largely robust to excluding women who had ever changed residence and observing only a subset of never-movers, except for a loss of significance for conflict within the past three months (p = 0.08; the coefficient remained the same). The results were also robust to using logistic instead of linear regression.

Qualitative methods

The qualitative segment of this study builds on expert interviews carried out with a total of 15 representatives, from civil society, government, and international development organizations specializing in women’s rights, sexual and reproductive health and rights, and/or the peace process from a gender perspective in Colombia. This purposeful sample of experts was found via mutual contacts, word-of-mouth recommendations, and chain referral. Experts were chosen on their knowledge of the field and willingness to participate (Bogner and Menz Citation2009).

Semi-structured interviews were conducted from November 2019 to February 2020, two on video call and the rest face to face in Bogotá. The interviews lasted between 30 minutes and two hours.

Participants were informed both at initial contact and the start of the interview about their full confidentiality and right to cancel the interview or not answer certain questions at any point without any consequences. Participants gave verbal consent to participate and for the interviews to be recorded. Names or descriptions of participants and organizations were not disclosed in the manuscript to safeguard their anonymity. Because there is no specific procedure in Colombia (Rivillas and Ingabire Citation2018) and Swedish legislation does not regulate data collection abroad, no ethical approval was sought for the data collection.

The interviews were analysed thematically using NVivo. I began the analysis by taking notes during data collection and transcription, then listening to and transcribing the interviews in full in the original language (English and/or Spanish). Next, the material was coded inductively by categorizing sentences with shorthand labels to describe their content and condense the information. Codes originated either from key domains from the interview guide or in vivo from the transcripts. Codes were then either aggregated into broader themes or discarded as irrelevant. The themes identified as pertinent for this study related to women’s reproductive health in relation to violent conflict in Colombia. The quality and accuracy of the codes and themes were checked with the transcriptions, while also exploring the range of and interrelationships between the codes. Finally, representative quotations were chosen to illustrate the material (Ayres Citation2012).

Qualitative results

The stakeholders considered the Colombian healthcare system to be in a state of crisis. The areas most affected by conflict also suffer from a chronic absence of state services, including healthcare. Even though coverage has increased over time, quality of care is often very poor, especially in remote areas. Access to care is restrictive and stratified: the most vulnerable and marginalized groups face barriers that more affluent groups do not. The role that conflict has played is to exacerbate the lack of access to healthcare for women who are already underserved.

For example, a woman living in a rural area who requests an abortion on one of the legal grounds (the life or health of the woman is threatened; foetal malformation; the pregnancy resulted from rape or incest) may have to wait months for a decision, even though the process is legally required to take a maximum of five days. Sometimes the closest clinic may not even have a pregnancy test in stock. Additionally, women in rural areas may need to spend hours or even days travelling to the nearest health clinic. When conflict violence intensifies and/or it obstructs economic prospects, women may not be able to access care whatsoever. Poverty and remoteness make sterilization the preferred contraceptive method for many women, as one interviewee noted:

In Colombia in the very poor regions, like near to the Pacific Coast for instance, most of the women decide their favourite method is sterilization because it’s cheap, because you only do it once. You don’t have to pay constantly. You don’t have access to nearby health care, so you go to a hospital to sterilize yourself and it’s okay.

Stakeholders also noted that activities of armed groups have impeded women’s reproductive autonomy. The armed groups controlling certain areas have often imposed their own view of sexual and reproductive health and rights, and have limited women’s access to contraception and abortion as part of a broader control of the population’s everyday life. Healthcare workers in those areas have been forced to perform services, prevented from going to certain areas, and attacked by armed groups. Forced contraception and sterilization have been reported among female FARC recruits and perhaps some women in relationships with FARC members, but the experts did not believe this reproductive control had spread to the civilian population, since those policies were instated to ensure the military capacity of their recruits.

Conflict has obstructed development in every form in the communities most affected by violence, not least when it comes to healthcare. The protracted lack of security makes medical doctors reluctant to spend their residency in such areas and there are no educational or labour market opportunities, creating a perpetual cycle of barriers to accessing services. In terms of commodities, roadblocks and closed drug stores have limited women’s access to contraceptive goods. Pharmaceutical shipments have been obstructed and unreliable, resulting in difficulties for women in knowing whether their contraceptive method will be available the next time they need it.

Regarding whether it is likely that forced sterilization has increased in light of conflict, one interviewee described the situation as follows:

If you understand economic constraint as an element in consent, you could say that they were forced. I mean, there is definitely a failure by the state to guarantee all of the contraceptive methods that are available and accessible and not only five-hours-train accessible but really accessible. But I’m not sure if I would qualify them as forced because they are willingly going, even if it’s in the lack of other options. As opposed to forced sterilization when you think about women with disabilities for instance, that is clearly forced. Like against your will. If it’s a woman who is just poor and she doesn’t want any more children, but she doesn’t see any more options or it’s too expensive to buy another type of contraception, I would say that it’s not so clear.

The multiple barriers that conflict-affected women may face to access sexual and reproductive healthcare in Colombia—especially if they also live in poor rural areas—point towards the increased sterilization uptake being a result of lack of other options, rather than a result of coercion. There may be exceptions in some subgroups of the population, but these are most likely not represented in the survey data.

Discussion

Results from linear probability regressions showed that local conflict generally increased women’s uptake of sterilization in Colombia. The effects of recent conflict were stronger than for long-term conflict, which could reflect women opting for permanent contraception when access to reversible methods becomes more unstable. Since uptake was largest among more affluent women with more than two children of mixed sex composition, it is likely that the results were driven by women’s increased demand for sterilization after completion of their fertility career rather than by coerced sterilization. The results are corroborated by Colombian experts in sexual and reproductive health, who reported that because the healthcare system had been so heavily affected by conflict, women may have been opting for sterilization in the absence of other options. Although it was not possible to test statistically whether sterilizations were coerced, this evidence suggests neither a reduced demand (Hypothesis 1), nor an involuntary decline (Hypothesis 3), nor an involuntary surge (Hypothesis 4) in sterilization uptake. Instead, the combined results indicate support for Hypothesis 2: conflict is linked to an increase in the voluntary uptake of sterilization. This adds to previous research reporting a reduction in the use of reversible contraceptive methods in relation to local violence in Colombia (Svallfors and Billingsley Citation2019) and provides novel insight into women’s fertility decisions in response to crises and violence.

Without reports of individual women’s perceptions, it is not possible to establish what the increased uptake of sterilization in relation to conflict truly represents: a desire to stop births permanently, a grasp for control in an inherently unstable and dangerous situation, or a reduction in access to reversible contraception. The available survey data did not allow these mechanisms to be evaluated, but the expert interviews provided some initial guidance. Their reports pointed towards the most socio-economically deprived women having the least contraceptive autonomy, whereas the regression models showed net averages over the whole population. The only (quasi) time-varying quantitative measures of socio-economic status available in the DHS were whether the respondent lived in a rural or urban area and the amount of time she had lived there, as well as whether she was still in education and her level of education at interview. Interaction terms between conflict and residence or education showed no statistically significant patterns (results available on request), which may be reflective of variation and statistical power being too low rather than a true null effect. Due to the limited number of time-varying variables available, it was not possible to address other socio-demographic characteristics, such as relationship status. Additionally, the DHS offers no data on availability of contraceptive goods and services. It was therefore not possible to confirm or reject the expert reports statistically.

Another limitation is that since no information about conflict intensity was available prior to January 1989, it is possible that any increases in sterilization uptake driven by conflict prior to observation would depress the estimates if a substantial proportion of women were already sterilized. As previously mentioned, assignment to treatment is unstable since women may self-select out of the most conflict-intense areas. Even if women are observed only in their residence at interview (to assign exposure correctly) and findings are largely robust to selecting women who never changed residence, this remains a limitation. Additionally, the estimations presented in this paper should be considered floor effects, given that the real levels of violence are likely underestimated due to reporting bias and the lack of sampled women to match with many conflict events.

The increase in sterilization uptake points to a relative resilience of family planning programmes in Colombia. Despite multiple decades of conflict, women are still able to access some methods, although not all and not necessarily their preferred one. Part of the explanation likely lies in Colombia’s programmes having been developed alongside conflict, but the findings also echo those from other settings where uptake—in particular of long-lasting methods—has increased after emergencies (Williams et al. Citation2012; Bietsch et al. Citation2020). Other studies have reported lower uptake of contraception and changes to the method mix post crisis (Kissinger et al. Citation2007; Hapsari et al. Citation2009; Leyser-Whalen et al. Citation2011; Behrman and Weitzman Citation2016). These disparities may reflect the varying robustness of different healthcare systems, emphasizing the need for family planning programmes and research efforts to distinguish between different forms of contraceptive autonomy. While women faced with conflict may be able to make an informed contraceptive choice based on accurate knowledge about different methods, they may be restricted from making a free choice of their preferred contraceptive method (Senderowicz Citation2020).

Women living in conflict-affected settings often face a routinized state of uncertainty characterized by livelihood insecurity and household instability; this calls for reproductive choices that reduce the risk of unwanted pregnancy (Schwarz et al. Citation2019). Even the most marginalized women still manoeuvre with whatever means they have at hand (Enloe Citation2000), and health-seeking behaviours can be a way to create order in the face of uncertainty (Steffen et al. Citation2005). Wanting or not wanting children is not an isolated event, but is connected to the woman’s perception of herself and others, present conditions, and future outcomes. Women’s fertility control may be the only form of agency they can exert in a situation with extremely limited choices: a pivotal strategy for managing risk (Dalsgaard Citation2005).

This study suggests that women choose sterilization more often when exposed to more conflict events. The tentative interpretation is that since sterilization is a low-cost, socially accepted, and highly effective option for family planning in Colombia, it may be the preferred method for women who have completed their fertility goals. Given how conflict disrupts everyday life, it is reasonable to believe that women will opt for more secure and reliable contraceptive choices. This represents an embodiment of war: whatever their circumstances, women will make choices on reproductive matters based on what they perceive will be most beneficial. Sterilization may represent a risk-aversion strategy of fertility regulation when other aspects of life turn more uncertain during armed conflict.

Considering these results, it is imperative that healthcare initiatives in Colombia ensure that women have access to any contraceptive method of their choosing, not only sterilization. Such efforts should focus particularly on rural areas with poor access to healthcare and high intensity of conflict. Further, the Colombian government must take all necessary steps to end violence in Colombia decisively, including fully implementing the Havana peace accords and assuming peace negotiations with remaining armed actors.

Supplementary Material

Download PDF (265.6 KB)Notes

1 Please direct all correspondence to Signe Svallfors, Department of Sociology, Stockholm University, Universitetsvägen 10 B, 10691 Stockholm, Sweden; or by Email: [email protected]

2 I am indebted to the research participants who generously shared their expertise with me. The interview data collection in Colombia was made possible by financial support from The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences under Grant SO2018–0042.

3 The material collected for this study is not publicly available to protect the confidentiality of participants, but some information could be made available on reasonable request. The quantitative data sets are available online at https://dhsprogram.com/ and Stata do-files can be requested from the author.

References

- Agadjanian, Victor and Ndola Prata. 2002. War, peace, and fertility in Angola, Demography 39(2): 215–231. doi:10.1353/dem.2002.0013

- Allison, Paul. 2009. Fixed Effects Regression Models. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Alzate, Mónica M. 2008. The sexual and reproductive rights of internally displaced women: The embodiment of Colombia’s crisis, Disasters 32(1): 131–148. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7717.2007.01031.x

- Angrist, Joshua D. and Jörn-Steffen Pischke. 2009. Mostly Harmless Econometrics: An Empiricist’s Companion. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Asdown Colombia. 2013. From Forced Sterilization to Forced Psychiatry: Report on Violations of the Human Rights of Women with Disabilities and Transgender Persons in Colombia. Available: https://www.madre.org/press-publications/human-rights-report/forced-sterilization-forced-psychiatry-report-violations (accessed: 17 September 2018).

- Ayres, Lioness. 2012. Thematic coding and analysis, in Lisa M. Given (ed), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, pp. 867–868.

- Batyra, Ewa. 2020. Contraceptive use behavior change after an unintended birth in Colombia and Peru, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 46: 9–19. doi:10.1363/46e8420

- Behrman, Julia Andrea and Abigail Weitzman. 2016. Effects of the 2010 Haiti earthquake on women’s reproductive health, Studies in Family Planning 47(1): 3–17. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4465.2016.00045.x

- Bergquist, Charles, Ricardo Peñaranda, and Gonzalo Sánchez G. 2001. Violence in Colombia, 1990–2000: Waging War and Negotiating Peace. Wilmington: SR Books.

- Bietsch, Kristin, Jessica Williamson, and Margaret Reeves. 2020. Family planning during and after the West African ebola crisis, Studies in Family Planning 51(1): 71–86. doi:10.1111/sifp.12110

- Blanc, Ann K. 2004. The role of conflict in the rapid fertility decline in Eritrea and prospects for the future, Studies in Family Planning 35(4): 236–245. doi:10.1111/j.0039-3665.2004.00028.x

- Bogner, Alexander and Wolfgang Menz. 2009. The theory-generating expert interview: Epistemological interest, forms of knowledge, interaction, in Alexander Bogner, Beate Littig, and Wolfgang Menz (eds), Interviewing Experts. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 43–80.

- Bumpass, Larry L., Elizabeth Thomson, and Amy L. Godecker. 2000. Women, men, and contraceptive sterilization, Fertility and Sterility 73(5): 937–946. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(00)00484-2

- Calderón, Valentina, Margarita Gáfaro, and Ana María Ibáñez. 2011. Forced migration, female labour force participation, and intra-household bargaining: Does conflict empower women? MICROCON Research Working Paper 56. Brighton: MICROCON.

- Cameron, Lisa and Manisha Shah. 2014. Risk-taking behavior in the wake of natural disasters, Journal of Human Resources 50(2): 484–515. doi:10.3368/jhr.50.2.484

- Casey, Sara E., Shanon E. McNab, Clare Tanton, Jimmy Odong, Adrienne C. Testa, and Louise Lee-Jones. 2013. Availability of long-acting and permanent family-planning methods leads to increase in use in conflict-affected Northern Uganda: Evidence from cross-sectional baseline and endline cluster surveys, Global Public Health 8(3): 284–297. doi:10.1080/17441692.2012.758302

- Casey, Sara E. and Martin Tshipamba. 2017. Contraceptive availability leads to increase in use in conflict-affected Democratic Republic of the Congo: Evidence from cross-sectional cluster surveys, facility assessments and service statistics, Conflict and Health 11(2).

- Cassar, Alessandra, Andrew Healy, and Carl von Kessler. 2017. Trust, risk, and time preferences after a natural disaster: Experimental evidence from Thailand, World Development 94: 90–105. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2016.12.042

- Castro Torres, Andrés Felipe and B. Piedad Urdinola. 2018. Armed conflict and fertility in Colombia, 2000–2010, Population Research and Policy Review 38: 173–213. doi:10.1007/s11113-018-9489-x

- CDR. 2014. Organizaciones de Varios Países Rechazan Decisión de La Corte Constitucional Colombiana Que Avala Esterilización de Menores Con Discapacidad Sin Su Consentimiento [Organizations from Several Countries Reject Decision of the Colombian Constitutional Court Endorsing Sterilization of Minors With Disabilities Without Their Consent]. Centro de Derechos Reproductivos. Available: https://www.reproductiverights.org/es/comunicados-de-prensa/Organizaciones-de-varios-paises-rechazan-decision-de-la-Corte-Constitucional-colombiana%20 (accessed: 16 September 2018).

- Cetorelli, Valeria. 2014. The effect on fertility of the 2003–2011 war in Iraq, Population and Development Review 40(4): 581–604. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2014.00001.x

- Chi, Primus Che, Patience Bulage, Henrik Urdal, and Johanne Sundby. 2015a. A qualitative study exploring the determinants of maternal health service uptake in post-conflict Burundi and Northern Uganda, BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 15(18).

- Chi, Primus Che, Patience Bulage, Henrik Urdal, and Johanne Sundby. 2015b. Perceptions of the effects of armed conflict on maternal and reproductive health services and outcomes in Burundi and Northern Uganda: A qualitative study, BMC International Health and Human Rights 15(7).

- Cripe, Swee May, Sixto E. Sanchez, Maria Teresa Perales, Nally Lam, Pedro Garcia, and Michelle A. Williams. 2008. Association of intimate partner physical and sexual violence with unintended pregnancy among pregnant women in Peru, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 100(2): 104–108. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.08.003

- Croicu, Mihai and Ralph Sundberg. 2017. UCDP Georeferenced Event Dataset Codebook Version 17.1. Uppsala University: Department of Peace and Conflict Research. Available: http://www.ucdp.uu.se/downloads/ged/ged171.pdf (accessed 28 May, 2018).

- Curry, Leslie and Marcella Nunez-Smith. 2015. Mixed Methods in Health Sciences Research: A Practical Primer. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Dalsgaard, Anne Line. 2004. Matters of Life and Longing: Female Sterilisation in Northeast Brazil. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Dalsgaard, Anne Line. 2005. Birth control, life control: Female sterilisation in Northeast Brazil, in Vibeke Steffen, Richard Jenkins, and Hanne Jessen (eds), Managing Uncertainty: Ethnographic Studies of Illness, Risk and the Struggle for Control. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- De Roux, S. J. and J. Francisco. 1994. The impact of drug trafficking on Colombian culture, in Kumar Rupesinghe and Marcial Rubio Correa (eds), The Culture of Violence. Tokyo: United Nations University Press, pp. 92–118.

- DHS. 1991. Colombia Encuesta de Prevalencia, Demografía y Salud 1990 [Colombia Survey of Prevalence, Demography and Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR9-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- DHS. 1995. Colombia Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 1995 [Colombia National Survey of Demography and Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR65-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- DHS. 2000. Colombia Salud Sexual y Reproductiva [Colombia Sexual and Reproductive Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR114-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- DHS. 2005. Colombia Salud Sexual y Reproductiva [Colombia Sexual and Reproductive Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR172-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- DHS. 2011. Colombia Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2010 [Colombia National Survey of Demography and Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR246-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- DHS. 2017. Colombia Encuesta Nacional de Demografía y Salud 2015 [Colombia National Survey of Demography and Health]. Bogotá: Profamilia. Available: http://dhsprogram.com/publications/publication-FR334-DHS-Final-Reports.cfm (accessed: 20 December 2017).

- Eckel, Catherine C., Mahmoud A. El-Gamal, and Rick K. Wilson. 2009. Risk loving after the storm: A Bayesian-network study of Hurricane Katrina evacuees, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 69: 110–124. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2007.08.012

- Elveborg Lindskog, Elina. 2016. Effects of violent conflict on women and children: Sexual behavior, fertility, and infant mortality in Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. PhD dissertation. Stockholm: Department of Sociology, Stockholm University.

- Enloe, Cynthia. 2000. Maneuvers: The International Politics of Militarizing Women’s Lives. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Folch, Beatriz M., Sarah Betstadt, Dongmei Li, and Natalie Whaley. 2017. The rise of female sterilization: A closer look at Colombia, Maternal and Child Health Journal 21: 1772–1777. doi:10.1007/s10995-017-2296-x

- Franco, Saúl, Clara Mercedes Suarez, Claudia Beatriz Naranjo, Liliana Carolina Báez, and Patricia Rozo. 2006. The effects of the armed conflict on the life and health in Colombia, Ciência & Saúde Coletiva 11(2): 349–361. doi:10.1590/S1413-81232006000200013

- Garfield, Richard and Claudia Patricia Llanten Morales. 2004. The public health context of violence in Colombia, Revista Panamericana de Salud Pública 16(4): 266–271. doi:10.1590/S1020-49892004001000006

- Gindele, Rebecca, Madhav Joshi, Louise Olsson, Jason Quinn, Elise Ditta, and Rebecca Méndez. 2018. Implementing the Final Colombian Peace Agreement, 2016–2018. Oslo: PRIO.

- Godecker, Amy L., Elizabeth Thomson, and Larry L. Bumpass. 2001. Union status, marital history and female contraceptive sterilization in the United States, Family Planning Perspectives 33(1): 35–49. doi:10.2307/2673740

- Gomez, Anu Manchikanti. 2011. Sexual violence as a predictor of unintended pregnancy, contraceptive use, and unmet need among female youth in Colombia, Journal of Women’s Health 20(9): 1349–1356. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2518

- Guttmacher. 1979. Colombia initiates voluntary sterilization program for women imperiled by poverty, poor health, International Family Planning Perspectives 5(2): 87–88. doi:10.2307/2948021

- Hanaoka, Chie, Hitoshi Shigeoka, and Yasutora Watanabe. 2018. Do risk preferences change? Evidence from the great East Japan earthquake, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics 10(2): 298–330. doi:10.1257/app.20170048

- Hapsari, Elsi Dwi, Wenny Artanty Nismanb Widyawatib, Lely Lusmilasarib, Rukmono Siswishantoc, and Hiroya Matsuo. 2009. Change in contraceptive methods following the Yogyakarta earthquake and its association with the prevalence of unplanned pregnancy, Contraception 79: 316–322. doi:10.1016/j.contraception.2008.10.015

- Herrera, Natalia and Douglas Porch. 2008. ‘Like going to a fiesta’ – The role of female fighters in Colombia’s FARC-EP, Small Wars & Insurgencies 19(4): 609–634. doi:10.1080/09592310802462547

- Hollerbach, Paula. 1989. The impact of national policies on the acceptance of sterilization in Colombia and Costa Rica, Studies in Family Planning 20(6): 308–324. doi:10.2307/1966434

- Ibáñez, Ana María and Andrés Moya. 2010. Do conflicts create poverty traps? Asset losses and recovery for displaced households in Colombia, in Rafael Di Tella, Sebastian Edwards, and Ernesto Schargrodsky (eds), The Economics of Crime: Lessons for and from Latin America, A National Bureau of Economic Research conference report. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, pp. 137–172.

- ICRC. 2011. Health Care in Danger: Making the Case. Geneva: International Committee of the Red Cross. Available: https://www.icrc.org/en/publication/4072-health-care-danger-making-case (accessed: 10 March 2020).

- Iqbal, Zaryab. 2010. War and the Health of Nations. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Islam, Asadul, Chandarany Ouch, Russell Smyth, and Liang Choon Wang. 2016. The long-term effects of civil conflicts on education, earnings, and fertility: Evidence from Cambodia, Journal of Comparative Economics 44: 800–820. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2015.05.001

- Jadhav, Apoorva and Emily Vala-Haynes. 2018. Informed choice and female sterilization in South Asia and Latin America, Journal of Biosocial Science: 1–17.

- Jansson, Oscar. 2008. The cursed leaf: An anthropology of the political economy of cocaine production in Southern Colombia. PhD dissertation. Uppsala University: Department of Cultural Anthropology and Ethnology.

- Jok, Jok Madut. 1999. Militarism, gender and reproductive suffering: The case of abortion in Western Dinka, Africa: Journal of the International African Institute 69(2): 194–212. doi:10.2307/1161022

- Jones, James Holland and Brodie Ferguson. 2006. The marriage squeeze in Colombia, 1973–2005: The role of excess male death, Social Biology 53(3–4): 140–151.

- Kendall, Tamil and Claire Albert. 2015. Experiences of coercion to sterilize and forced sterilization among women living with HIV in Latin America, Journal of the International AIDS Society 18(19462).

- Kim, Young-Il and Jungmin Lee. 2014. The long-run impact of a traumatic experience on risk aversion, Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization 108: 174–186. doi:10.1016/j.jebo.2014.09.009

- Kishor, Sunita and Kiersten Johnson. 2004. Profiling Domestic Violence: A Multi-Country Study. Calverton: ORC Macro.

- Kissinger, Patricia, Norine Schmidt, Cheryl Sanders, and Nicole Liddon. 2007. The effect of the Hurricane Katrina disaster on sexual behavior and access to reproductive care for young women in New Orleans, Sexually Transmitted Diseases 34(11): 883–886. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318074c5f8

- Kreft, Anne-Kathrin. 2020. Civil society perspectives on sexual violence in conflict: Patriarchy and war strategy in Colombia, International Affairs 96(2): 457–478. doi:10.1093/ia/iiz257

- La Mattina, Giulia. 2017. Civil conflict, domestic violence and intra-household bargaining in post-genocide Rwanda, Journal of Development Economics 124: 168–198. doi:10.1016/j.jdeveco.2016.08.001

- Leite, Iúri Da Costa, Neeru Gupta, and Roberto Do Nascimento Rodrigues. 2004. Female sterilization in Latin America: Cross-national perspectives, Journal of Biosocial Science 36(6): 683–698. doi:10.1017/S0021932003006369

- Lerner, Jennifer S., Roxana M. Gonzalez, Deborah A. Small, and Baruch Fischhoff. 2003. Effects of fear and anger on perceived risks of terrorism: A national field experiment, Psychological Science 14(2): 144–150. doi:10.1111/1467-9280.01433

- Leyser-Whalen, Ophra, Mahbubur Rahman, and Abbey B. Berenson. 2011. Natural and social disasters: Racial inequality in access to contraceptives after Hurricane Ike, Journal of Women’s Health 20(12): 1861–1866. doi:10.1089/jwh.2010.2613

- Lindstrom, David P. and Betemariam Berhanu. 1999. The impact of war, famine, and economic decline on marital fertility in Ethiopia, Demography 36(2): 247–261. doi:10.2307/2648112

- McGinn, Therese, Judy Austin, Katherine Anfinson, Ribka Amsalu, Sara E. Casey, Shihab Ibrahim Fadulalmula, Anne Langston, Louise Lee-Jones, Janet Meyers, Frederick Kintu Mubiru, Jennifer Schlecht, Melissa Sharer, and Mary Yetter. 2011. Family planning in conflict: Results of cross-sectional baseline surveys in three African countries, Conflict and Health 5(11).

- Miranda, J. Jaime and Alicia Ely Yamin. 2004. Reproductive health without rights in Peru, The Lancet 363: 68–69. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15175-6

- Montgomery, Mark R. 2000. Perceiving mortality decline, Population and Development Review 26(4): 795–819. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2000.00795.x

- Mood, Carina. 2010. Logistic regression: Why we cannot do what we think we can do, and what we can do about it, European Sociological Review 26(1): 67–82. doi:10.1093/esr/jcp006

- Navarro Valencia, Martha Cecilia. 2009. Uniones, maternidad y salud sexual y reproductiva de las Afrocolombianas de Buenaventura: Una perspectiva antropológica [Unions, motherhood, and sexual and reproductive health of Afro-Colombian women from Buenaventura: An anthropological perspective], Revista Colombiana de Antropología 45(1): 39–68. doi:10.22380/2539472X.984

- Nortman, Dorothy L. 1980. Sterilization and the birth rate, Studies in Family Planning 11(9/10): 286–300. doi:10.2307/1966366

- O’Hare, Bernadette A. M. and David P. Southall. 2007. First do no harm: The impact of recent armed conflict on maternal and child health in Sub-Saharan Africa, Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 100: 564–570. doi:10.1177/0141076807100012015

- Orach, Christopher Garimoi, George Otim, Juliet Faith Aporomon, Richard Amone, Stephen Acellam Okello, Beatrice Odongkara, and Henry Komakech. 2015. Perceptions, attitude and use of family planning services in post conflict Gulu District, Northern Uganda, Conflict and Health 9(24).

- Pallitto, Christina C., Claudia García-Moreno, Henrica A. F. M. Jansen, Lori Heise, Mary Ellsberg, and Charlotte Watts. 2013. Intimate partner violence, abortion, and unintended pregnancy: Results from the WHO multi-country study on women’s health and domestic violence, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 120: 3–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2012.07.003

- Parrado, Emilio A. 2000. Social change, population policies, and fertility decline in Colombia and Venezuela, Population Research and Policy Review 19(5): 421–457. doi:10.1023/A:1010676303313

- Potter, Joseph E., G. Myriam Ordóñez, and Anthony R. Measham. 1976. The rapid decline in Colombian fertility, Population and Development Review 2(3/4): 509–528. doi:10.2307/1971628

- Rabe-Hesketh, Sophia and Anders Skrondal. 2011. Multilevel and Longitudinal Modeling Using Stata. College Station: Stata.

- Rangel, Marcos A., Jenna Nobles, and Amar Hamoudi. 2020. Brazil’s missing infants: Zika risk changes reproductive behavior, Demography 57: 1647–1680. doi:10.1007/s13524-020-00900-9

- Reilly, Philip R. 2015. Eugenics and involuntary sterilization: 1907–2015, Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics 16: 351–368. doi:10.1146/annurev-genom-090314-024930

- Rivillas, Juan and Marie-Gloriose Ingabire. 2018. Seeking ethics approval in Colombia: A health systems research case study, Canadian Journal of Bioethics 1(1): 28–30. doi:10.7202/1058311ar

- Rizo, Alberto and Laura Roper. 1986. The role of sterilization in Colombia’s family planning program: A national debate, International Family Planning Perspectives 12(2): 44–48. doi:10.2307/2947949

- Rutayisire, Pierre Claver, Annelet Broekhuis, and Pieter Hooimeijer. 2013. Role of conflict in shaping fertility preferences in Rwanda, African Population Studies 27(2): 105–117. doi:10.11564/27-2-433

- Rutenberg, Naomi and Evelyn Landry. 1993. A comparison of sterilization use and demand from the Demographic and Health Surveys, International Family Planning Perspectives 19(1): 4–13. doi:10.2307/2133376

- Sacco, Katiuscia, Valentina Galletto, and Enrico Blanzieri. 2003. How has the 9/11 terrorist attack influenced decision making?, Applied Cognitive Psychology 17: 1113–1127. doi:10.1002/acp.989

- Salvesen, Hilde and Dag Nylander. 2017. Towards an Inclusive Peace: Women and the Gender Approach in the Colombian Peace Process. NOREF Norwegian Center for Conflict Resolution. Available: https://noref.no/Publications/Regions/Colombia/Towards-an-inclusive-peace-women-and-the-gender-approach-in-the-Colombian-peace-process (accessed: 5 May 2019).

- Schindler, Kati and Tilman Brück. 2011. The effects of conflict on fertility in Rwanda, The World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5715. Available: https://ssrn.com/abstract=1875421 (accessed: 28 May 2021).

- Schmeer, Kammi K. and Jake Hays. 2017. Multipartner fertility in Nicaragua: Complex family formation in a low-income setting, International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health 43(1): 29–38. doi:10.1363/43e3317

- Schwarz, Joëlle, Mari Dumbaugha, Wyvine Bapolisia, Marie Souavis Ndorered, Marie-Chantale Mwaminie, Ghislain Bisimwac, and Sonja Merten. 2019. “So that’s why I’m scared of these methods”: Locating contraceptive side effects in embodied life circumstances in Burundi and Eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo, Social Science & Medicine 220: 264–272. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.030

- Senderowicz, Leigh. 2020. Contraceptive autonomy: Conceptions and measurement of a novel family planning indicator, Studies in Family Planning 51(2): 161–176. doi:10.1111/sifp.12114

- Speizer, Ilene S. 2006. Using strength of fertility motivations to identify family planning program strategies, International Family Planning Perspectives 32(4): 185–191. doi:10.1363/3218506

- Steffen, Vibeke, Richard Jenkins, and Hanne Jessen (eds). 2005. Managing Uncertainty: Ethnographic Studies of Illness, Risk and the Struggle for Control. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Stock, James H. and Mark W. Watson. 2008. Heteroskedasticity-robust standard errors for fixed effects panel data regression, Econometrica 76(1): 155–174. doi:10.1111/j.0012-9682.2008.00821.x

- Sundberg, Ralph and Erik Melander. 2013. Introducing the UCDP georeferenced event dataset, Journal of Peace Research 50(4): 523–532. doi:10.1177/0022343313484347

- Svallfors, Signe. 2020. The remarkable stability of fertility desires during the Colombian armed conflict 2000–2016, Stockholm Research Reports in Demography 2020(50). Available: https://su.figshare.com/articles/preprint/The_Remarkable_Stability_of_Fertility_Desires_during_the_Colombian_Armed_Conflict_2000_2016/13353224 (accessed: 28 May 2021).

- Svallfors, Signe. Forthcoming. Hidden casualties: The links between armed conflict and intimate partner violence in Colombia, Politics & Gender.

- Svallfors, Signe and Sunnee Billingsley. 2019. Conflict and contraception in Colombia, Studies in Family Planning 50(2): 87–112. doi:10.1111/sifp.12087

- Tashakkori, Abbas and Charles Teddlie. 2016. SAGE Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social & Behavioral Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications.

- Tembo, Doreen. 2014. Chapter 8: Mixed methods, in Dawn-Marie Walker (ed), An Introduction to Health Services Research. London: SAGE Publications, pp. 115–126.

- Torrisi, Orsola. 2020. Armed conflict and the timing of childbearing in Azerbaijan, Population and Development Review 46(3): 501–556. doi:10.1111/padr.12359

- Trias, Miguel, J. E. Anderson, Gabriel Ojeda, and M. W. Oberle. 1987. A lifetable analysis of sterilization failure: Data from the Profamilia clinic, Bogota, Colombia, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 25: 235–240. doi:10.1016/0020-7292(87)90240-2

- Van Bavel, Jan and David S. Reher. 2013. The baby boom and its causes: What we know and what we need to know, Population and Development Review 39(2): 257–288. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00591.x

- Verwimp, Philip, David Osti, and Gudrun Østby. 2020. Forced displacement, migration, and fertility in Burundi, Population and Development Review 46(2): 287–319. doi:10.1111/padr.12316

- Vikat, Andres, Elizabeth Thomson, and Jan M. Hoem. 1999. Stepfamily fertility in contemporary Sweden: The impact of childbearing before the current union, Population Studies 53(2): 211–225. doi:10.1080/00324720308082

- Voors, Maarten J, Eleonora E. M. Nillesen, Philip Verwimp, Erwin H. Bulte, Robert Lensink, and Daan P. Van Soest. 2012. Violent conflict and behavior: A field experiment in Burundi, American Economic Review 102(2): 941–964. doi:10.1257/aer.102.2.941

- Weber, Elke U., Ann-Renée Blais, and Nancy E. Betz. 2002. A domain-specific risk-attitude scale: Measuring risk perceptions and risk behaviors, Journal of Behavioral Decision Making 15: 263–290. doi:10.1002/bdm.414

- Williams, Nathalie E., Dirgha J. Ghimire, William G. Axinn, Elyse A. Jennings, and Meeta S. Pradhan. 2012. A micro-level event-centered approach to investigating armed conflict and population responses, Demography 49(4): 1521–1546. doi:10.1007/s13524-012-0134-8

- Williams, Timothy, Gabriel Ojeda, and Miguel Trias. 1990. An evaluation of Profamilia’s female sterilization program in Colombia, Studies in Family Planning 21(5): 251–264. doi:10.2307/1966505

- Wirtz, Andrea L., Kiemanh Pham, Nancy Glass, Saskia Loochkartt, Teemar Kidane, Decssy Cuspoca, Leonard S Rubenstein, Sonal Singh, and Alexander Vu. 2014. Gender-based violence in conflict and displacement: Qualitative findings from displaced women in Colombia, Conflict and Health 8(10).

- Woldemicael, Gebremariam. 2008. Recent fertility decline in Eritrea: Is it a conflict-led transition?, Demographic Research 18: 27–58. doi:10.4054/DemRes.2008.18.2

- Woldemicael, Gebremariam. 2010. Declining fertility in Eritrea since the mid-1990s: A demographic response to military conflict, International Journal of Conflict and Violence 4(1): 149–168.

- Zampas, Christina and Adriana Lamačková. 2011. Forced and coerced sterilization of women in Europe, International Journal of Gynecology & Obstetrics 114: 163–166. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2011.05.002

- Østby, Gudrun, Michele Leiby, and Ragnhild Nordås. 2019. The legacy of wartime violence on intimate-partner abuse: Microlevel evidence from Peru, 1980–2009, International Studies Quarterly 63(1): 1–14. doi:10.1093/isq/sqy043