Abstract

Death of a parent during childhood has become rare in developed countries but remains an important life course event that may have consequences for family formation. This paper describes the link between parental death before age 18 and fertility outcomes in adulthood. Using the large national 2011 French Family Survey (INSEE–INED), we focus on the 1946–66 birth cohorts, for whom we observe entire fertility histories. The sample includes 11,854 respondents who have lost at least one parent before age 18. We find a strong polarization of fertility behaviours among orphaned males, more pronounced for those coming from a disadvantaged background. More often childless, particularly when parental death occurred in adolescence, some seem to retreat from parenthood. But orphaned men and women who do become parents seem to embrace family life, by beginning childbearing earlier and having more children, especially when the deceased parent is of the same sex.

Introduction

The death of a parent in childhood or adolescence has become rare (Uhlenberg Citation1980) but no less important. In fact, it may be even more important due to the reduced visibility of orphanhood in contemporary societies and the greater frailty of the orphaned population, which is why studies of its consequences are particularly welcome (Leopold and Lechner Citation2015). In the United States in 2014, around 9 per cent of adults aged 20–24 had lost at least one parent (Scherer and Kreider Citation2019), and in France this was the case for around 6 per cent of those aged 18–24 in the 2000s (Monnier and Pennec Citation2005; Flammant Citation2019). Losing a father occurs much more frequently than losing a mother, and the loss of both parents in childhood/adolescence is very rare (involving 5 per cent of all orphans). The specificity of the orphaned population and their experience of loss makes them particularly likely to experience different trajectories for their own family later in life (Kiernan Citation1992; Blanpain Citation2008; Reneflot Citation2011; Dahlberg Citation2020).

The importance of family structure in early life has been identified as fundamental for later-life outcomes in the literature on divorce (McLanahan and Bumpass Citation1988; Wu and Schimmele Citation2003; Lyngstad and Jalovaara Citation2010). Like the children of separated parents, orphans (who, in this paper, we define as children who have lost one or both parents) experience parental absence and can be exposed to diminished economic resources or differences in parenting. The death of one or both parents at an early age has short- and long-term financial, psychological, and developmental repercussions for the child (see e.g. Stikkelbroek et al. Citation2012) and makes orphans a particularly fragile group (Marks et al. Citation2007; Flammant Citation2020). In particular, adults who have experienced the death of a parent in early life seem to be more vulnerable than those who have experienced parental divorce, and this calls for a specific study of orphans and their later-life family experiences (Mack Citation2001).

Up to now, the literature linking parental loss in childhood to fertility has focused mainly on early adult stages. Orphaned individuals generally seek economic and household independence earlier than non-orphans (Kiernan Citation1992; Kane et al. Citation2010; Shenk and Scelza Citation2012), and they also enter partnership and parenthood earlier (Hepworth et al. Citation1984; Kiernan Citation1992; Blanpain Citation2008; Reneflot Citation2011; Shenk and Scelza Citation2012). Little is known about their subsequent reproductive lives. On one hand, some orphaned adults may, implicitly or explicitly, try to counterbalance the early loss of a parent or a shorter perceived life expectancy (Geronimus Citation1996) by forming a new family earlier and having more children than non-orphaned adults, in other words, they more often embrace family life. On the other hand, those who experience parental loss in childhood may be more reluctant to form a family, for instance because they perceive themselves as more vulnerable to the deaths of relatives (Mireault and Bond Citation1992) or tend to avoid intimacy (Hepworth et al. Citation1984). This could result in a retreat from parenthood for some orphaned individuals, notably in the form of childlessness or postponement of parenthood.

We investigate here the link between parental death before age 18 and fertility behaviour in adulthood among women and men, specifically by considering a variety of fertility indicators: timing of entry into parenthood; permanent childlessness; and average number of children, both for those who become parents and overall (including the childless).

The lack of large data sources offering a long-term perspective has prevented in-depth studies of the link between orphanhood and future family construction. We use here the very large French data set from the most recent Family and Housing Survey, in 2011, and focus particularly on the 1946–66 birth cohorts (N = 130,170), the most recent cohorts for whom we can observe entire fertility histories and calculate completed fertility. We study men and women separately, given their differential reactions to parental death (Leopold and Lechner Citation2015) and their distinct childbearing and family behaviours (Koropeckyj-Cox and Pendell Citation2007; Winkler-Dworak and Toulemon Citation2007). We distinguish between non-orphaned and orphaned adults, while also detailing for the latter their age when the parent died and the sex of the deceased parent. We also control several possible confounding factors and study possible heterogeneity in behaviour linked to level of education and socio-economic background.

Background

Context and past results

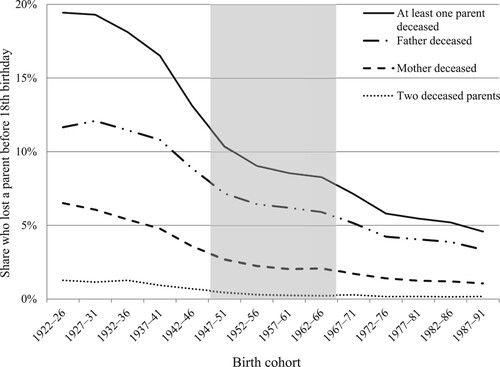

Losing a parent during childhood or adolescence was a common event for the generations whose parents went through the First or Second World Wars. More than 19 per cent of French people born in the 1920s and still alive in 2011 had lost at least one parent before reaching age 18 (). Note that the real proportions of orphans at that time may have been higher, given the higher chances of orphans dying at early ages (see Data subsection). The death of parents in early life largely became less common for cohorts over the century: 5 per cent of adults born in the late 1980s had lost at least one parent by age 18. The greyed zone in highlights the cohorts selected for our study (1946–66), namely those born after the Second World War and aged 45–65 at the time of the survey. In these cohorts, the share of adults who had lost at least one parent during childhood or adolescence was still relatively high, stabilizing at around 9 per cent among adults born around 1960 before decreasing anew, as also observed by Flammant (Citation2019) using older data (for which attrition due to early mortality was more limited). The most recent slowdown can be attributed to the plateauing mortality gains at adult ages and is reinforced by childbearing postponement: being born to older parents increases the risk of losing a parent at an early age (Flammant Citation2020).

Figure 1 Percentage of individuals born between 1922 and 1991 who were alive in France in 2011 and had experienced the death of a parent by their 18th birthday

Source: French Family and Housing Survey 2011 (INSEE–INED); authors’ calculations using sample weights.Notes: The grey zone highlights the cohort selected for our study.

Orphans constitute such a small group that data representative of this population are scarcely available for studying their behaviour later in life. On one hand, Reneflot (Citation2011) showed earlier entry into parenthood in Norway for both women and men who had lost a parent before age 16: they were more likely to have a child before age 23. This was only partially explained by their lower educational level. Blanpain (Citation2008), on the other hand, explained the association between father’s death and early parenthood in France by the earlier completion of education. Finally in the UK, although age at first intercourse did not differ much for women who had lost a parent by age 16 compared with those from an intact family, the former were more likely to have a child before age 20 (Kiernan Citation1992; Kiernan and Hobcraft Citation1997). No significant association was found among men.

These studies focused on entry into parenthood but generally lacked the time window to study the effects of orphanhood over the whole reproductive lifespan. Dahlberg (Citation2020) recently focused on the experience of parental death in adulthood in Sweden and found that those who had lost a parent during reproductive ages were more likely to remain childless at age 45, with this effect being stronger among men. However, he considered parental loss only at adult ages. The limited scope of study in the literature further highlights the need for a comprehensive study of orphaned adults’ childbearing behaviour over the whole life course, particularly one based on a large data set.

Mechanisms behind childbearing outcomes

We next describe mechanisms—beyond unobserved characteristics of the environment in childhood and adolescence—that might lead to divergent fertility behaviours among the orphaned themselves and to their differences from the non-orphaned. Parental death is usually considered as a ‘critical event’ in the life course (McLeod and Almazan Citation2003; Jost Citation2012). Although the first studies on the topic may have largely overstated the effect on depression because they were based mostly on selected samples of hospital patients (Tremblay and Israel Citation1998), parental death clearly causes psychological distress (Stikkelbroek et al. Citation2012; Berg et al. Citation2016; Bergman et al. Citation2017). Adults who had lost at least one parent to death during their childhood or adolescence perceived themselves as more vulnerable to the death of a relative (Mireault and Bond Citation1992); they more often experienced specific anxieties and substance use disorders (Stikkelbroek et al. Citation2012); their suicide rates were higher (Guldin et al. Citation2015; Saarela and Rostila Citation2019); and they were more frequently hospitalized for mental health issues (Serratos-Sotelo and Eibich Citation2021).

Literature on human stress response highlights the variability in behavioural reactivity to stressful life events, such as death of a loved one. According to the stress–vulnerability model, notably used to understand depression (Monroe and Simons Citation1991) or self-injury (Brodsky Citation2016), genetic predispositions reinforce the risk of individuals developing a disorder when exposed to stress (Quaedflieg and Smeets Citation2013). Reaction to stress also depends on the childhood environment, and this explains, for instance, why psychosocial stress can have either an inhibiting or an accelerating effect on pubertal development (Ellis Citation2004). These strands of psychiatry and evolutionary literature on stress vulnerability suggest that the responses to parental death can be very diverse (Boyce and Ellis Citation2005). In the specific case of family life, we expect some individuals who experience early parental death to retreat from parenthood and others to embrace family life, while still others may show no specific reaction.

Retreat from parenthood associated with parental loss in childhood or adolescence may result indirectly from a reaction to stress leading to social withdrawal or negative affect (Luecken Citation2008; Rubin et al. Citation2009), which corresponds to foregoing childbearing, possibly via decreased partnership formation. Some orphans also develop a more insecure attachment style, which may result in more unstable partnerships and eventually a lower number of children (Luecken and Roubinov Citation2012). For other individuals, a predisposition against parenthood may be exacerbated by parental death, leading to lower transition into parenthood. Finally, health problems potentially related to the parent’s premature death may be genetically transmitted to the child (Luecken and Roubinov Citation2012). Orphaned adults’ childlessness propensity could then be increased due to potential health issues or from their reluctance to plan long-term projects, knowing that they could transmit these health issues to their children. Orphaned individuals in these situations may experience a lower likelihood of having any children, as well as later childbearing and a lower total number of children.

In contrast, the experience of a parent’s death may magnify a predisposition for family life. In some orphans, this stressful event may reinforce family values and the desire to form their own family, thus resulting later in a greater likelihood of having a child, less delay in entering parenthood, and larger family size. A positive relationship could stem from a greater appreciation for loved ones and a stronger belief that life is precious, a feeling often shared by adults who have lost a parent in childhood (Greene and McGovern Citation2017). In addition, orphans who have reached adulthood may demonstrate a better ability to cope with adverse events (Finkelstein Citation1988), develop a positive image of the missing parent (Miller and Barbara Citation1971; Cournos Citation2001), and be more prone to having large families because of their greater appreciation for life (Greene and McGovern Citation2017). Orphanhood can also trigger a need for creating family links that were not experienced in childhood or for recreating links that were suddenly interrupted by the parent’s death (Hetherington Citation1972). To compensate for parental loss, the orphaned may want to have children in order to experience for themselves a full family life.

Also, higher childhood adversity and exposure to death seem to motivate earlier fertility and larger family sizes (McAllister et al. Citation2016). The evolutionary perspective on behavioural development associated with early-life stress suggests that children who encounter high levels of stress because of the loss of parental attention or time may experience earlier ages at menarche, sexual activity, and parenthood (Belsky et al. Citation1991; Chisholm et al. Citation2005). Health uncertainty and a shorter prospective lifespan may also trigger a perception among some orphaned adults that they should have children faster (Geronimus Citation1996). Overall, these effects would lead a larger share of these survivors to start a family earlier and have more children, or in other words, to embrace family life.

Orphanhood may include many additional dimensions that are indirectly associated with future fertility behaviour (i.e. mediators). Research has shown that orphanhood triggers early life transitions (Blanpain Citation2008; Shenk and Scelza Citation2012) and that orphaned young adults achieve lower educational levels (Kane et al. Citation2010; Serratos-Sotelo and Eibich Citation2021), reach lower occupational positions (Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge Citation2019), and leave the parental home earlier (Kiernan Citation1992). This could be due to the parental loss itself, to (negative) selection into orphanhood, to diminished parental investment, or to the absence of a parent in the household (Scherer and Kreider Citation2019; Serratos-Sotelo and Eibich Citation2021). Notably, those who have ever lived in a single parent family show lower educational and socio-economic attainment (Amato and Keith Citation1991; Ermisch and Francesconi Citation2001). Because of their shorter period in education, orphaned individuals are likely to form a family at an earlier age and to have their first child earlier (Kiernan Citation1992; Blanpain Citation2008; Reneflot Citation2011). This earlier family formation schedule may ultimately lead to their having more children, because those who form a family earlier tend to have more children (Tomkinson Citation2019).

Finally, parental loss may be associated with a higher risk of child poverty (Flammant Citation2020) due to the loss of one parental income. While dedicated public transfers that have existed since 1970 (first called Allocation orphelin and since 1984 Allocation de Soutien Familial) may help the family of the surviving parent, the living standards of orphans are surely negatively affected. In addition, orphans are a particularly select group. Because of the socio-economic gradient in mortality risk among young adults (Luy et al. Citation2011), orphans more often come from disadvantaged families (Monnier and Pennec Citation2005; Flammant Citation2019; Scherer and Kreider Citation2019). Studies have found unfavourable family circumstances, whether related to socio-economic status or conflict within the home, to be associated with early termination of schooling, as well as couple formation, marriage, and pregnancy at younger ages (Cherlin et al. Citation1995; Bereczkei and Csanaky Citation2001; Blanpain Citation2008). Independent of socio-economic status, orphans’ families may have other specific characteristics that potentially affect a child’s development and their adult behaviour, many of which remain unobserved. Although we cannot control for all selection issues in our models, we do take into account a range of observed characteristics that contribute to the heterogeneity of the group.

We summarize here our two main hypotheses:

H1: Parental loss in early life may correspond to a retreat from parenthood, with orphaned adults: (a) more often being childless; and (b) delaying entry into parenthood.

Conversely,

H2: orphaned individuals may embrace family life by: (a) accelerating timing of entry into parenthood; and (b) having more than the average number of children among those who do form a family, independent of the timing.

Own sex, age at parental death, and sex of the deceased parent

The reaction to the death of a parent appears to be gendered and also depends on the sex of the deceased parent (Hetherington Citation1972). This is the case in several domains of observation. For instance, at adult ages, life satisfaction was found to drop most among women who had lost their mother (Leopold and Lechner Citation2015). In contrast, boys were more likely to die than girls after they had lost a parent—with the mother’s death being more detrimental than the father’s death for both—and men remained more vulnerable to their mother’s death later in life (Rostila and Saarela Citation2011). Furthermore, although the risk of self-injury increased for young men and women in cases of parental loss, maternal loss before school age had an effect only on men (Rostila et al. Citation2016). Kane et al. (Citation2010) found that educational attainment diminished only when the parent who had died was of the same sex as the child. We thus expect effects to differ by sex and also to depend on the sex of the deceased parent. We also anticipate possibly finding different effects depending on whether one or both parents have died.

The age at which the parent dies may also determine later behaviour (Serratos-Sotelo and Eibich Citation2021). On one hand, there is some evidence that parental death at very young ages is more detrimental to children’s development and well-being (Hetherington Citation1972). Cerniglia et al. (Citation2014) showed that psychological welfare was higher in adolescence when the parent had died after the child was three than if they died before the child was three. Moreover, socio-economic outcomes in adulthood were significantly reduced when the parent (and particularly the mother) had died before the child reached age 10 (Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge Citation2019). On the other hand, if the parent dies while the child is still young, the parent will possibly find a new partner, who may function as the child’s substitute parent (Graham Citation2010). If the parent dies while the child is in their teens, they will have known the deceased parent very well and be fully conscious of the loss. Overall, we expect the effect of the loss to vary with age and more specifically depending on whether parental death occurred during childhood or adolescence. Following the previous observations on the socio-economic situations of orphans, we also explore whether the link between parental death and fertility timing and level differs by cultural and socio-economic background.

Data and method

Data

We use the most recent nationally representative French Family and Housing Survey (Enquête Famille et Logements), run by the French National Institute of Statistics and Economic Studies (INSEE) and French Institute for Demographic Studies (INED) in 2011 and conducted by adding a self-completion paper questionnaire on family and housing to the 2011 Census core questionnaire for about 0.5 per cent of the adult population aged 18 years and older. Women were purposely oversampled to facilitate fertility studies; this is accounted for in the weighting and by studying men and women separately. The response rate was 84 per cent and weights were implemented by INSEE (Citation2013) to adjust for non-response, sampling, and cluster effects. The 360,000 respondents provided information about their mother and father: country of birth; citizenship at birth; employment and activity status (past or present); whether the parent was still alive; and, if not, their year of death. Although respondents were asked specifically about their mothers and fathers, they were given the possibility of answering about the person who had raised them. Children adopted at very early ages may thus more often have declared the date when one or both of their ‘social’ parents died (rather than their biological parents). As Flammant (Citation2019) found an overall good fit between the number of orphans in this survey and numbers found in other longitudinal data and in series of cross-sectional French data sets, this suggests that most parental deaths before age 18 were declared and indeed concerned a biological parent.

To focus on regular generations in which the death of a parent is not linked to other confounding events (such as wars and their consequences), we limit our sample to respondents born after the Second World War (from 1946 onwards). This limit also implies that we do not observe respondents who are too old (maximum age of 65 years at survey) and we thus partly avoid bias in survival due to differential mortality, which can be of particular concern in studies of orphans. Indeed, orphaned individuals are more likely to die early than others in a population (Rostila and Saarela Citation2011; Li et al. Citation2014) for several reasons (genetic disease, intergenerational transmission of health or risky behaviours, and poverty). Thus, life expectancy may be shorter for respondents who have lost a parent at an early age than for those who have not, hence respondents from older cohorts may not be observed in the data set. This might also be the case in the cohorts studied, although in a more limited way, and we cannot exclude underestimation and potential biases linked to differential mortality.

In addition, we deal only with individuals who have reached the end of their fertile years, by selecting those aged at least 45 at the time of the survey. Stopping the observation of fertility at age 45 should not bias the fertility indicators, because few children were born after that age. In most European countries around 1990 (when these cohorts were of childbearing age), less than 0.1 per cent of women’s completed fertility was attributed to children born after age 45, while for men it was around 2.5 per cent (authors’ calculations from Human Fertility Database Citation2021). In the questionnaire, respondents filled in a grid with the name plus month and year of birth of all their own children. When no information about date of birth was available, INSEE matched these declarations to the census household grid to recover missing birthdates and imputed the remaining missing years of birth (INSEE Citation2014). Fertility indicators used as outcomes in the study are calculated based on this full birth calendar.

Overall, in the 1946–66 generations under study (N = 130,170), around one in ten respondents had experienced the death of at least one parent before age 18 (11,854 orphaned adults).

Method

Our study focuses on indicators of timing and level of fertility in order to compare the orphaned and non-orphaned populations. More precisely, for men and women we calculate total number of children by age 45, as well as the proportion childless and number of children conditional on being a parent. We also calculate mean age at first birth and the proportions of those who became parents early: before age 23 for men and before age 21 for women. After an initial descriptive exploration of these indicators, we model the most relevant to our analysis to observe whether the difference in fertility behaviour depending on parental loss before age 18 persists once observable differences are accounted for.

Models

We use methods that are widely applied in modelling lifetime fertility, to compare orphaned with non-orphaned populations. Linear regressions (ordinary least squares, OLS) are used to model completed fertility (for all respondents and for parents only). We also tested a count model (Poisson regression), often used in completed fertility studies because it accounts for the fact that the total number of children is a discrete and non-negative variable (Wu and Schimmele Citation2003), and obtained very similar results to those obtained with linear regressions, both for all respondents and for parents only. Childlessness is modelled using probit regressions. For timing, we use linear regressions of age at first birth. As we can observe the entire fertility period, there is no censorship and thus no need to use survival analysis in this case. Finally, as we expect different results for men and women theoretically, we systematically perform separate models. We also tested full models with an interaction of parental death with sex of respondent, and results were unchanged.

Variable of interest

We use the date of parental death indicated in the survey to calculate the age of respondent at the time of the death. From this, we consider that the respondent was an orphan if one of their parents died before they turned 18. We differentiate between those where neither parent died, the father only or the mother only died, or both died. Note that orphaned respondents who lost both parents are in a separate category because they theoretically show different behaviours from those who have lost only one parent. However, the size of this group is not always large enough for the results to be significant, especially for men, so we rarely mention them in the results. Finally, we show an interaction of sex of the parent with age of the respondent when their parent died.

Other controls

We control for birth cohort, first because there was a drop in fertility and a rise in childbearing postponement in the cohorts under study and, second, because the reaction to parental death may have changed over time. We then control for parental characteristics: each parent’s country of birth and occupation. The parent’s occupational category was also asked when the parent was retired or dead, hence this information is available for orphaned as well as non-orphaned respondents. It is coded by INSEE using the French Classification of Professions and Socioprofessional Categories. There was little professional mobility in these cohorts and occupation was measured in seven wide groups (Chapoulie Citation2000), ensuring that the parental occupation declared for orphaned vs non-orphaned adults should not suffer a bias linked to the younger age of the deceased parent when their occupation was last observed. Still, it remains likely that orphaned individuals less often knew or declared their deceased parent’s socio-economic status. We code this instance separately in a ‘not available’ category but also tried to impute missing values. Although possibly correlated with the death of the parent (because there is less time for further births if the death occurs in early childhood), the number of siblings (including step- and full siblings) is relevant, as the reorganization of the household after parental death probably differs depending on the number of siblings, many children meaning wider age differences and thus more potential to care for each other. In addition, it is necessary to control for siblings in models of fertility, since future fertility depends on own sibship size (Murphy Citation2013). In our preferred specification (Model 4), we control for this set of family and parental characteristics.

Other determinants of fertility exist but may also mediate the effect of parental loss on fertility, hence we include them in additional models as possible mechanisms of fertility behaviours. We consider three. First, when modelling total number of children conditional on being a parent, we include age at first birth, as this will mediate the relationship between orphanhood and family size. Second, level of education is a usual correlate of fertility levels and, in addition, may be a mediator for the timing of childbearing (because those who finish their education earlier tend to start having children earlier). We thus include respondents’ level of education (last diploma obtained) at time of survey as a mechanism in all models; in most cases, this corresponds to the educational level at time of family formation, because in France in the cohorts under study most people were having their first child after completing their education (Ní Bhrolcháin and Beaujouan Citation2012). A third possible mechanism through which orphanhood may affect fertility is couple formation, for instance if orphaned adults are less likely than the non-orphaned to form a couple (see Appendix ). We thus include a variable about experience of a past co-resident relationship when modelling childlessness and completed fertility. No information is available on relationship timing, hence models of childbearing timing do not include this potential additional mechanism. Appendix describes the characteristics of the non-orphaned and orphaned populations, which are used as control variables hereafter.

Results

Childbearing timing for orphaned adults

describes all five fertility outcomes (weighted) for men and women separately, depending on experience of parental death in early life. Like past studies, our results show earlier timing of entry into parenthood for orphaned individuals. Orphaned women had their first child around one year earlier than non-orphaned women, and for men it was four to six months earlier. Orphaned individuals also more frequently experienced childbirth early in their life course. The share of first births occurring before age 21 was 16 per cent among non–orphaned women and around 23–26 per cent among orphaned women. For men, the share before age 23 also increased in cases of parental loss but to a lesser extent and with the difference being significant only when the father had died.

Table 1 Fertility outcomes by parental death during childhood (means and proportions): French men and women born 1946–66

The models on timing of first birth () confirm the earlier arrival of a first child among those who had lost a parent, particularly among women. The addition of step-by-step controls diminishes this effect and, for men, the earlier birth timing remains (slightly) significant only in the case of maternal loss. Among orphaned women, the acceleration of childbearing was of larger magnitude when the mother had died than when the father had died, and it was strongest when both parents had died. The changes after adding the control variables show that part of the timing differences originally observed was due to the socio-economic and cultural background of the orphaned. As mentioned earlier and shown in Appendix , the orphaned individuals in our sample ended their studies sooner and thus possibly had children earlier for that reason. Nonetheless, the association of orphanhood with the timing of childbearing decreases but persists after controlling for the level of education (, column 5).

Table 2 OLS regression of age at first birth by parental death during childhood, with gradual introduction of control variables: French men and women born 1946–66 who are parents

The earlier timing we observe for women and only partly for men is in line with the family life embracement hypothesis (H2), whereby these cohorts manifested their desire to build a new family as soon as possible. We next investigate whether orphaned adults have more children than others once they have started a family and the link between number of children and their earlier childbearing.

Family size for orphaned adults who become parents

If we consider only adults who had started a family and thus exclude childless people, the descriptive results () show that individuals who had lost at least one parent before age 18 had larger families than those who had not. The average number of children observed for parents in the cohorts studied was often higher for orphaned individuals (2.4 for men and women who had lost their father, 2.5 for women who had lost their mother) than for the non-orphaned (2.3 children per person). Once again, the difference was larger among women.

presents model results for the number of children conditional on being a parent. After controlling for cohort, socio-economic background, and siblings (Model 4), the coefficients become smaller. Only women who had lost a mother and men who had lost a father eventually had more children than the non-orphaned: respectively 0.155 and 0.061 more children (less significant for men). An alternative model using Poisson regression (Appendix ) gives very similar results. This larger family size could be due to the earlier timing of births among orphaned individuals, which allowed them a longer span to have children during their fertile period. That is why we control for age at first birth in column 5 () as a possible mediating mechanism. The link with loss of a parent of the same sex becomes even smaller and only persists significantly among mothers. The inclusion of respondents’ level of education (column 6) only marginally changes these results. Overall, earlier parenthood among the orphaned, whether linked to shorter time in education or not, was one mechanism leading to their higher fertility. Still, it was not the only one among orphaned women who had lost their mother, who still had slightly more children on average (0.083) after taking these two possible mechanisms into account.

Table 3 OLS regression of number of children, by parental death during childhood, with gradual introduction of control variables: French men and women born 1946–66 who are parents

Share of orphaned adults remaining childless

This picture of early and high fertility among the orphaned is mitigated when looking at their likelihood of remaining childless. In descriptive terms, while 17 per cent of non-orphaned men in the generations studied were childless, this percentage reached almost 20 per cent for those who had lost their mother and 19 per cent for those who had lost their father, but the differences were only significant at the 10 per cent level (). Orphaned women remained childless in nearly the same proportion as non-orphaned women (around 13 per cent). Probit regressions () show the higher likelihood of childlessness among men whose father or mother had died (significant at 5 per cent), while there is no significant effect for orphaned women (Model 4). Regarding the mechanisms, among men, controlling for level of education diminishes the contrast between the orphaned and non-orphaned (column 5), and controlling further for past couple experience completely cancels the effect (column 6). This means that lower education and less couple formation among orphaned adults probably partly drive childlessness among men. Appendix indeed shows that men who were orphaned as children acquired less education and were less likely to have ever been in a relationship.

Table 4 Probit regression of childlessness, by parental death during childhood, with gradual introduction of control variables: French men and women born 1946–66

The bidirectional nature of the previous results (i.e. lower likelihood of becoming parents for orphaned men but accelerated timing and larger families among the orphaned—particularly women—who do become parents) warrants two further investigations. First, do orphaned individuals have more offspring than the non-orphaned overall? Second, is the fertility response to parental death common across the orphaned population or do they display heterogeneity? We consider these questions next.

Completed fertility

The descriptive results () show that women who had lost only one parent before age 18 had more children overall themselves once they were adults: 2.19 children if they had lost their mother or 2.09 if they had lost their father, against 2.01 children for the non-orphaned. , which includes both parents and non-parents, uses linear regressions to show the extent to which the total number of children is sensitive to the death of a parent after controlling step by step for several characteristics. Men’s completed fertility does not differ in the case of parental death (Model 4). Note however that after controlling for the two main mechanisms—education and the absence of a couple relationship—the coefficient becomes significant for men who had lost their father, confirming the previously observed polarized behaviours among orphaned men who managed to form a family and those who did not. Among women, the death of the mother has a persistent effect in all models: women who had lost their mother had 0.12 more children than non-orphaned women on average (Model 4). These results go into the same direction as the previous ones but are less clear cut. This highlights that completed fertility gives an incomplete picture of the difference between the orphaned and non-orphaned, and it was necessary to use indicators that make the distinction between the likelihood of becoming a parent and the number of offspring.

Table 5 OLS regression of completed fertility, by parental death during childhood, with gradual introduction of control variables: French men and women born 1946–66

Heterogeneity among the orphaned population

We have already pointed out that the fertility reaction to parental loss before age 18 differs for men and women and by the sex of the parent who died. It could differ in other dimensions, and we explore two of them here: age at parental loss and socio-economic status.

shows the same models presented earlier (number of children among parents in and childlessness in ), but it includes age at parental death (during childhood (ages 0–12) or adolescence (ages 13–17)) interacting with the sex of the deceased parent. Among individuals who became parents, the link between death of a parent and number of children is rather uniform across age at parental loss in models with controls. It reflects the relationship found in the general models, with some loss of significance probably due to the smaller size of the age groups. In contrast, age effects clearly stand out in the case of childlessness, with men who had lost a parent in adolescence more likely to be childless. The coefficients are of similar magnitude whether teenage boys had lost a father or a mother (but significant only at 5 per cent after controls in the case of maternal death, possibly because the sample size is smaller). Consistent with the results on childlessness for the orphaned population who lost a parent at any age, no significant effect is found for women.

Table 6 Models of number of children (among parents) and childlessness, by age at parental death, without and with control variables: French men and women born 1946–66

We approach socio-economic situation by means of orphaned adults’ educational level. However, as educational level may be reduced in cases of parental death (Appendix shows that education levels are lower among orphaned individuals), we also use an alternative definition of disadvantaged background, based on the father’s professional situation (i.e. where the father never worked or was a manual worker). In , we present results without (columns 3 and 4) and with (columns 5 and 6) imputations for this family background variable.

Table 7 Models of (a) number of children (among parents) and (b) childlessness, by orphaned adults’ educational level and family background: French men and women born 1946–66

Regardless of how we define socio-economic situation, we observe that for men, it was mostly in less advantaged socio-economic settings that parental loss mattered for fertility (). Low-educated men and women had larger families (when becoming parents) if the same-sex parent had died, whereas this is not observed for the more highly educated. Larger family size is also observed only for men coming from a disadvantaged family background, whether we use the imputed or non-imputed version of the variable. In contrast, mothers had significantly more children in the case of mother’s death regardless of their socio-economic background.

The higher likelihood of remaining childless for men whose mother had died was confirmed when they came from a disadvantaged background or were less educated. In the models based on father’s occupation, men from a non-disadvantaged background who had lost their father appear more likely to be childless than the non-orphaned. In that particular case, a larger share of non-disadvantaged orphaned men remained childless, which shows the diversity in reaction to a critical event such as parental death. The findings among women are consistent with previous results in that: (1) the probability of being childless was much less affected by parental loss (with the exception of more highly educated women who had lost a mother, who were somewhat more likely to remain childless than the non-orphaned, a result not confirmed by the models based on father’s occupation, however); and (2) no specific direction emerges for socio-economic background.

Thus, the fertility patterns of both female and males in the orphaned population are sensitive to their individual educational attainment, which can reflect their different timing of entry into adulthood. However, orphaned men’s fertility behaviour is more related to their family background than orphaned women’s.

Discussion

This study has provided more clarity about the link between parental death during childhood or adolescence and fertility at adult ages, specifically by using a large sample and fertility indicators covering entire childbearing histories. Because of the stronger polarization of family sizes among orphaned adults, particularly men, we saw that limiting the study to cohort completed fertility was not sufficient for understanding the substantive differences between orphaned and non-orphaned individuals. It is crucial to use alternative indicators on the timing of parenthood, childlessness likelihood, and number of children once a first child is born. The study has brought forth a very clear link between parental loss and childbearing behaviour among the French 1946–66 birth cohorts.

Childlessness was more frequent among orphaned men who had lost either their father or their mother than among non-orphaned men in our study. These results support for men the assumption that some orphaned individuals experience a retreat from parenthood (H1). Lower educational attainment and overall a lower likelihood of ever forming a couple are important drivers of this parenthood retreat among men. Orphaned adults’ lower qualifications possibly lead them more often to be unemployed or to hold insecure jobs. Since stable employment is often a precondition for both couple formation and entry into parenthood for men (Régnier-Loilier and Solaz Citation2010), this may be one of the mechanisms of higher childlessness among orphaned men. In contrast, orphaned women in our study did not encounter a higher likelihood of remaining single or childless. This is in line with gender role theories, where labour market patterns play much more on family decisions for men than women. Women are more likely to ‘invest’ in the family sphere than men if their work situation is unsatisfactory. We are unfortunately unable to check this interpretation, as it would require retrospective data on professional trajectories.

Like past studies, we found that those who had lost a parent before age 18, especially women, accelerated childbearing in most cases and were more often early parents. This did not seem to be entirely mediated by their characteristics or their lower level of education (i.e. earlier termination of schooling), since the difference persisted after controls. On becoming parents, the orphaned had larger family sizes than the non-orphaned (both before and after basic controls), particularly among women who had lost a mother and somewhat among men who had lost a father. Our hypothesis that orphaned adults are more likely to embrace parenthood by having a large and/or early family (H2) thus seems valid. Interestingly, such an effect was observed mainly in the case of losing the same-sex parent; this might come from a possible need as an adult to take on the missing role of the lost parent to compensate for their loss. The effect weakened, but persisted only among women, when controlling for age at first birth and level of education. Not only did orphaned women have children sooner, but those who started a family also had more children. However, the earlier birth schedule was not the only reason for a larger family, as the difference persisted after controlling for age at first birth.

Our results are in line with evolutionary explanations suggesting that exposure to death leads to adoption of alternative reproductive strategies (Chisholm et al. Citation1993). They are also strongly gendered: orphaned women do not retreat from parenthood but instead have particularly large families, more consistently taking up their presumed role to perpetuate the family, regardless of their family background or age at parental death. The polarized fertility behaviour of orphaned men is consistent with the polarization also found for the formation of intimate relationships (Hepworth et al. Citation1984), in which two opposite patterns among undergraduate orphaned adults emerged: avoidance of intimate relationships or, on the contrary, accelerated entry into a committed relationship. Possibly, orphaned children and teenagers internalize gender socialization practices differently from the non-orphaned (Endendijk et al. Citation2018). The gendered results, the importance of partnership formation and education as mechanisms, and the different behaviours depending on the sex of the parent who died and age of the child at the loss, lead us to believe that the dominating cause of different fertility behaviours among orphaned adults is mostly social and that selection into orphanhood plays only a minor role.

Orphaned men (but not women) displayed social heterogeneity, and their fertility levels and likelihood of not becoming a parent were both more sensitive to parental loss among those from disadvantaged families. Polarized family size was thus amplified for orphaned men belonging to a more disadvantaged group, whereas it was almost absent for those from wealthier families. The additional stress brought on by parental death may resonate more in poorer children’s life outcomes due to their exposure to a more deprived and stressful environment (Prior Citation2021). By comparison, children from more favourable socio-economic settings may be more able to recover after parental loss, possibly because there is less economic insecurity in their household after the death or because they have access to better infrastructure and psychological care. As suggested by the stress–vulnerability model, aspects such as childhood environment may thus reinforce or mitigate reactions to parental loss, especially for men (Endendijk et al. Citation2018).

It is striking that orphaned adults’ fertility profiles contrasted with those of the rest of the population in the same way that low-educated individuals contrast with the rest of the population in most industrialized countries: namely, in their earlier childbearing schedules (Winkler-Dworak and Toulemon Citation2007; Nicoletti and Tanturri Citation2008), larger families (Wood et al. Citation2014), and higher childlessness, principally among men (Robert-Bobée Citation2006). This could correspond to a ‘pattern of disadvantage’ (Perelli-Harris and Gerber Citation2011), that is, a fertility pattern that appears mostly among those who are less integrated into society.

The literature on parental separation submits additional arguments about the possible effects of parental loss. A common argument for explaining the link between parental break-up and future family behaviours is socialization, whereby parental models and supervision are critical for explaining future family behaviours (McLanahan and Bumpass Citation1988). However, the hypothesis that the same family structure (lone parenthood after divorce vs after parental death) should lead to the same outcome has not been verified for a number of family transitions, limiting the possibility of generalization (Kiernan Citation1992; Cherlin et al. Citation1995; Reneflot Citation2011). Applying the theoretical framework of parental separation to parental death is also difficult because the natures of the events differ in many ways (Hepworth et al. Citation1984; McLanahan et al. Citation2013). Parental death is less predictable than parental separation and is less associated with pre-event conflicts. The end of the child–parent relationship is obvious in the case of death, whereas the relationship with parents has to be redefined after a parental separation. Further research is thus necessary to deepen our understanding of orphaned adults’ family behaviour and possibly to extend this acquired insight to the absence of one parent, whatever the reason.

One limitation of our study was the lack of information about possible recovery mechanisms after parental loss, such as the remaining parent remarrying or repartnering. Reneflot (Citation2011) found no significant differences in the odds of having a child by age 23 if the remaining parent had remarried after bereavement or not, but found significant differences in the family context of first births, with marriage being more favoured than cohabitation when the parent had remarried. Also, those whose parent had remarried tended to leave the parental home earlier (Villeneuve-Gokalp Citation2005; Berg et al. Citation2021). Investigation from a life course perspective of the events that take place after bereavement would bring important complementary information. In addition, the set-up of our study did not allow us to establish causally the effects on adult outcomes from losing a parent early in life. As mentioned previously, specific behaviour among orphaned adults could arise from unobserved characteristics of the parent who died early that influenced the childhood environment and of the transmitted poorer health or genetic disease.

The description of the mechanisms behind possible differences between orphaned and non-orphaned adults nonetheless enriches the understanding of the orphaned population and paves the way for future studies able to deal with this endogeneity issue. A promising avenue would be, for instance, to obtain more information on the causes of parental death. We established in this study that in addition to the psychological consequences of parental loss in childhood or adolescence, some orphaned adults display specific short- and long-term fertility behaviour that reflects greater vulnerability. Orphaned women much more often have a child before they are 21, which may be of concern for the child’s future, given that parents’ financial resources are also likely to be limited at this young age. The fact that orphaned men are especially likely to be childless also raises concerns about continued loneliness and the consequences of mental health issues on social and family life. These specificities call for careful policy provisions—particularly, economic support for orphans of disadvantaged backgrounds—and long-term health follow-up for children who have lost a parent.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Éva Beaujouan is based at the Wittgenstein Centre for Demography and Global Human Capital (IIASA, OeAW, University of Vienna). Anne Solaz is based at INED, the French Institute for Demographic Studies.

2 Please direct all correspondence to Anne Solaz, INED—French Institute for Demographic Studies, 9 Cours des Humanités, 93300 Aubervilliers. France; or by Email: [email protected]

References

- Amato, Paul R. and Bruce Keith. 1991. Separation from a parent during childhood and adult socioeconomic attainment, Social Forces 70(1): 187–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/2580068

- Belsky, Jay, Laurence Steinberg, and Patricia Draper. 1991. Childhood experience, interpersonal development, and reproductive strategy: An evolutionary theory of socialization, Child Development 62(4): 647–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131166

- Bereczkei, T. and A. Csanaky. 2001. Stressful family environment, mortality, and child socialisation: Life-history strategies among adolescents and adults from unfavourable social circumstances, International Journal of Behavioral Development 25(6): 501–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250042000573

- Berg, Lisa, Mikael Rostila, and Anders Hjern. 2016. Parental death during childhood and depression in young adults – A national cohort study, Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 57(9): 1092–1098. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12560

- Berg, Lonneke van den, Matthijs Kalmijn, and Thomas Leopold. 2021. Stepfamily effects on early home-leaving: The role of conflict and closeness, Journal of Marriage and Family 83(2): 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12700

- Bergman, Ann Sofie, Ulf Axberg, and Elizabeth Hanson. 2017. When a parent dies - A systematic review of the effects of support programs for parentally bereaved children and their caregivers, BMC Palliative Care 16(1): 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12904-017-0223-y

- Blanpain, Nathalie. 2008. Perdre Un Parent Pendant l’enfance : Quels effets sur le parcours scolaire, professionnel, familial et sur la santé à l’âge adulte ? [Losing a parent in childhood: What effects on education, employment, family and health in adulthood?], Etudes et Résultats 668.

- Boyce, W. Thomas and Bruce J. Ellis. 2005. Biological sensitivity to context: I. An evolutionary-developmental theory of the origins and functions of stress reactivity, Development and Psychopathology 17(2): 271–301. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579405050145

- Brodsky, Beth S. 2016. Early childhood environment and genetic interactions : The diathesis for suicidal behavior, Current Psychiatry Reports 18 (9). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0716-z

- Cerniglia, Luca, Silvia Cimino, and Giulia Ballarotto. 2014. Parental loss during childhood and outcomes on adolescents’ psychological profiles: A longitudinal study, Current Psychology 33: 545–556. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9228-3

- Chapoulie, Simone. 2000. Une nouvelle carte de la mobilité professionnelle [A new professional mobility Map], Economie et Statistique 331(1): 25–45. https://doi.org/10.3406/estat.2000.6788

- Cherlin, Andrew J., Kathleen E. Kiernan, and P. Lindsay Chase-Lansdale. 1995. Parental divorce in childhood and demographic outcomes in young adulthood, Demography 32(3): 299–318. https://doi.org/10.2307/2061682

- Chisholm, James S., Peter T. Ellison, Jeremy Evans, P. C. Lee, Leslie Sue Lieberman, Zdenek Pavlik, et al. 1993. Death, hope, and sex: Life-history theory and the development of reproductive strategies [and comments and reply], Current Anthropology 34(1): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1086/204131

- Chisholm, James S., Julie A. Quinlivan, Rodney W. Petersen, and David A. Coall. 2005. Early stress predicts age at menarche and first birth, adult attachment, and expected lifespan, Human Nature 16(3): 233–265. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12110-005-1009-0

- Cournos, Francine. 2001. Mourning and adaptation following the death of a parent in childhood, Journal of the American Academy of Psychoanalysis 29(1): 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1521/jaap.29.1.137.17189

- Dahlberg, Johan. 2020. Death is not the end: A register-based study of the effect of parental death on adult children’s childbearing behavior in Sweden, OMEGA - Journal of Death and Dying 81(1), 80–106. https://doi.org/10.1177/0030222818756740

- Ellis, Bruce J. 2004. Timing of pubertal maturation in girls : An integrated life history approach, Psychological Bulletin 130(6): 920–958. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.130.6.920

- Endendijk, Joyce J., Marleen G. Groeneveld, and Judi Mesman. 2018. The gendered family process model : An integrative framework of gender in the family, Archives of Sexual Behavior 47(4): 877–904. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10508-018-1185-8

- Ermisch, John and Marco Francesconi. 2000. The increasing complexity of family relationships: Lifetime experience of lone motherhood and stepfamilies in Great Britain, European Journal of Population 16(3): 235–249. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026589722060

- Ermisch, John and Marco Francesconi. 2001. Family matters: Impacts of family background on educational attainments, Economica 68(270): 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0335.00239

- Finkelstein, Harris. 1988. The long-term effects of early parent death: A review, Journal of Clinical Psychology 44(1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(198801)44:1<3::AID-JCLP2270440102>3.0.CO;2-1

- Flammant, Cécile. 2019. Approche démographique de l’orphelinage en France [Demographic approach to orphanhood in France], Ph.D. Thesis in Demography, INED-CRIDUP. https://orphelins.site.ined.fr/fr/la-recherche/

- Flammant, Cécile. 2020. An ongoing decline in early orphanhood in France, Population & Societies 580. https://www.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/30356/580.orphanhood.population.societies.august.2020.ang_web.en.pdf

- Geronimus, Arline T. 1996. What teen mothers know, Human Nature 7(4): 323–352. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02732898

- Graham, R. K. 2010. The stepparent role: How it is defined and negotiated in stepfamilies in New Zealand. http://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/handle/10063/1552

- Greene, Nathan and Katie McGovern. 2017. Gratitude, psychological well-being, and perceptions of posttraumatic growth in adults who lost a parent in childhood, Death Studies 41(7): 436–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481187.2017.1296505

- Guldin, Mai Britt, Jiong Li, Henrik Søndergaard Pedersen, Carsten Obel, Esben Agerbo, Mika Gissler, Sven Cnattingius, et al. 2015. Incidence of suicide among persons who had a parent who died during their childhood: A population-based cohort study, JAMA Psychiatry 72(12): 1227–1234. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.2094

- Hepworth, Jeri, Robert G. Ryder, and Albert S. Dreyer. 1984. The effects of parental loss on the formation of intimate relationships, Journal of Marital and Family Therapy 10(1): 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1752-0606.1984.tb00567.x

- Hetherington, E. Mavis. 1972. Effects of father absence on personality development in adolescent daughters, Developmental Psychology 7(3): 313–326. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0033339

- Human Fertility Database. Retrieved January 2021, www.humanfertility.org

- INSEE. 2013. Calcul des pondérations de l’enquête famille et logements [Calculation of the weights for the family and housing survey]. Paris.

- INSEE. 2014. Apurements et imputations dans l’Enquête famille et logements 2011 [Data cleaning and imputations in the 2011 family survey]. https://lili-efl2011.site.ined.fr/fichier/s_rubrique/20511/apurements.et.imputations.dans.la.enqu.te1.fr.pdf

- Jost, Gerhard. 2012. Biographical structuring through a critical life event: Parental loss during childhood, in K. B. Hackstaff, F. Kupferberg, and C. Négroni (eds), Biography and Turning Points in Europe and America. Bristol: The Policy Press, pp. 123–142.

- Kane, John, Lawrence M. Spizman, James Rodgers, and Rick R. Gaskins. 2010. The effect of the loss of a parent on the future earnings of a minor child, Eastern Economic Journal 36: 370–390. https://doi.org/10.1057/eej.2010.25

- Kiernan, Kathleen E. 1992. The impact of family disruption in childhood on transitions made in young adult life, Population Studies 46(2): 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000146206

- Kiernan, Kathleen E. and John Hobcraft. 1997. Parental divorce during childhood: Age at first intercourse, partnership and parenthood, Population Studies 51(1): 41–55. https://doi.org/10.1080/0032472031000149716

- Koropeckyj-Cox, Tanya and Gretchen Pendell. 2007. The gender gap in attitudes about childlessness in the United States, Journal of Marriage and Family 69: 899–915. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2007.00420.x

- Leopold, Thomas and Clemens M. Lechner. 2015. Parents’ death and adult well-being: Gender, age, and adaptation to filial bereavement, Journal of Marriage and Family 77(3): 747–760. https://doi.org/10.1111/jomf.12186

- Li, Jiong, Mogens Vestergaard, Sven Cnattingius, Mika Gissler, Bodil Hammer Bech, Carsten Obel, and Jørn Olsen. 2014. Mortality after parental death in childhood: A nationwide cohort study from three Nordic countries, PLoS Medicine 11: e1001679. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1001679

- Luecken, Linda J. 2008. Long-term consequences of parental death in childhood: Psychological and physiological manifestations, in M. S. Stroebe, R. O. Hansson, H. Schut, and W. Stroebe (eds), Handbook of Bereavement Research and Practice: Advances in Theory and Intervention. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1037/14498-019

- Luecken, Linda J. and Danielle S. Roubinov. 2012. Pathways to lifespan health following childhood parental death, Social and Personality Psychology Compass 6(3): 243–257. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2011.00422.x

- Luy, Marc, Paola Di Giulio, and Graziella Caselli. 2011. Differences in life expectancy by education and occupation in Italy, 1980-94: Indirect estimates from maternal and paternal orphanhood, Population Studies 65(2): 137–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2011.568192

- Lyngstad, Torkild Hovde and Marika Jalovaara. 2010. A review of the antecedents of union dissolution, Demographic Research 23: 257–291. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2010.23.10

- Mack, Kristin Yagla. 2001. Childhood family disruptions and adult well-being: The differential effects of divorce and parental death, Death Studies 25(5): 419–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/074811801750257527

- Marks, Nadine F., Heyjung Jun, and Jieun Song. 2007. Death of parents and adult psychological and physical well-being A Prospective U.S. National Study, Journal of Family Issues 28(12): 1611–1638. https://doi.org/10.1177/0192513X07302728

- McAllister, Lisa S., Gillian V. Pepper, Sandra Virgo, and David A. Coall. 2016. The evolved psychological mechanisms of fertility motivation: Hunting for causation in a sea of correlation, Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 371(1692). https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2015.0151

- McLanahan, Sara and Larry Bumpass. 1988. Intergenerational consequences of family disruption, American Journal of Sociology 94(1): 130–152. https://doi.org/10.1086/228954

- McLanahan, Sara, Laura Tach, and Daniel Schneider. 2013. The causal effects of father absence, Annual Review of Sociology 39: 399–427. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-071312-145704

- McLeod, Jane D. and Elbert P. Almazan. 2003. Connections between childhood and adulthood, in J. T. Mortimer and M. J. Shanahan (eds), Handbook of the Life Course. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, pp. 391–411.

- Miller, Menes and Jill Barbara. 1971. Children’s reactions to the death of a parent: A review of the psychoanalytic literature, Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association 19(4): 697–719. https://doi.org/10.1177/000306517101900405

- Mireault, Gina C. and Lynne A. Bond. 1992. Parental death in childhood: Perceived vulnerability, and adult depression and anxiety, American Jounal of Orthopsychiatry 62(4): 517–524. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079371

- Monnier, Alain and Sophie Pennec. 2005. Orphelins et orphelinage [Orphans and orphanhood], in C. Lefèvre and A. Filhon (eds), Histoires de Familles, Histoires Familiales : Les Résultats de l’enquête Famille de 1999. Paris: Ined, pp. 367–385.

- Monroe, Scott M. and Anne D. Simons. 1991. Diathesis-stress theories in the context of life stress research: Implications for the depressive disorders, Psychological Bulletin 110(3): 406–425. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.110.3.406

- Murphy, Michael. 2013. Cross-national patterns of intergenerational continuities in childbearing in developed countries, Biodemography and Social Biology 59(2): 101–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/19485565.2013.833779

- Ní Bhrolcháin, Máire and Éva Beaujouan. 2012. Fertility postponement is largely due to rising educational enrolment, Population Studies 66(3): 311–327. https://doi.org/10.1080/00324728.2012.697569

- Nicoletti, Cheti and Maria Letizia Tanturri. 2008. Differences in delaying motherhood across European countries: Empirical evidence from the ECHP, European Journal of Population - Revue Européenne de Démographie 24(2): 157–183. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-008-9161-y

- Perelli-Harris, Brienna and Theodore P. Gerber. 2011. Nonmarital childbearing in Russia: Second demographic transition or pattern of disadvantage?, Demography 48(1): 317–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-010-0001-4

- Prior, Lucy. 2021. Allostatic load and exposure histories of disadvantage, International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 18(14). https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147222

- Quaedflieg, C. W. E. M. and T. Smeets. 2013. Stress vulnerability models, in M. D. Gellman and J. R. Turner (eds), Encyclopedia of Behavioral Medicine. New York: Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4419-1005-9_65

- Régnier-Loilier, Arnaud and Anne Solaz. 2010. La décision d’avoir un enfant : Une liberté sous contraintes, Politiques Sociales et Familiales 100. http://doi.org/10.3406/caf.2010.2526

- Reneflot, Anne. 2011. Childhood family structure and reproductive behaviour in early adulthood in Norway, European Sociological Review 27(1): 56–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcp055

- Robert-Bobée, Isabelle. 2006. Ne pas avoir eu d’enfant : Plus fréquent pour les femmes les plus diplômées et les hommes les moins diplômés [Remaining childless: More frequent for most educated women and less educated men], in France, Portrait Social: 2006. Paris: Insee, pp. 181–196.

- Rosenbaum-Feldbrügge, Matthias. 2019. The impact of parental death in childhood on sons’ and daughters’ status attainment in young adulthood in the Netherlands, 1850–1952, Demography 56(5): 1827–1854. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13524-019-00808-z

- Rostila, Mikael, Lisa Berg, Arzu Arat, Bo Vinnerljung, and Anders Hjern. 2016. Parental death in childhood and self-inflicted injuries in young adults-a national cohort study from Sweden, European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 25(10): 1103–1111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0833-6

- Rostila, Mikael and Jan M. Saarela. 2011. Time does not heal all wounds: Mortality following the death of a parent, Journal of Marriage and Family 73(1): 236–249. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00801.x

- Rubin, Kenneth H., Robert J. Coplan, and Julie C. Bowker. 2009. Social withdrawal in childhood, Annual Review of Psychology 60: 141–171. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.60.110707.163642

- Saarela, Jan, and Mikael Rostila. 2019. Mortality after the death of a parent in adulthood: A register-based comparison of two ethno-linguistic groups, European Journal of Public Health 29(3): 582–587. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/cky189

- Scherer, Zachary, and Rose M. Kreider. 2019. Exploring the link between socioeconomic factors and parental mortality, SEHSD Working Paper 2019-12; SIPP Working Paper 288. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/working-papers/2019/demo/sehsd-wp2019-12.pdf

- Serratos-Sotelo, Luis and Peter Eibich. 2021. Lasting effects of parental death during childhood: Evidence from Sweden, MPIDR Working Paper WP 2021-00.

- Shenk, Mary K. and Brooke A. Scelza. 2012. Paternal investment and status-related child outcomes: Timing of father’s death affects offspring success, Journal of Biosocial Science 44(05): 549–569. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0021932012000053

- Stikkelbroek, Yvonne, Peter Prinzie, Ron de Graaf, Margreet ten Have, and Pim Cuijpers. 2012. Parental death during childhood and psychopathology in adulthood, Psychiatry Research 198(3): 516–520. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.024

- Tomkinson, John. 2019. Age at first birth and subsequent fertility: The case of adolescent mothers in France and England and Wales, Demographic Research 40: 761–798. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2019.40.27

- Tremblay, George C. and Allen C. Israel. 1998. Children’s adjustment to parental death, Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 5(4): 424–438. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2850.1998.tb00165.x

- Uhlenberg, Peter. 1980. Death and the family, Journal of Family History 5(3): 313–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/036319908000500304

- Villeneuve-Gokalp, Catherine. 2005. Conséquences des ruptures familiales sur le départ des enfants, in C. Lefèvre and A. Filhon (eds), Histoires de Familles, Histoires Familiales : Les Résultats de l’enquête Famille de 1999. Paris: Ined, pp. 235–250.

- Winkler-Dworak, Maria and Laurent Toulemon. 2007. Gender differences in the transition to adulthood in France: Is there convergence over the recent period?, European Journal of Population - Revue Européenne de Démographie 23(3-4): 273–314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10680-007-9128-4

- Wood, Jonas, Karel Neels, and Tine Kil. 2014. The educational gradient of childlessness and cohort parity progression in 14 low fertility countries, Demographic Research 31(46): 1365–1416. https://doi.org/10.4054/DemRes.2014.31.46

- Wu, Zheng and Christoph M. Schimmele. 2003. Childhood family experience and completed fertility, Canadian Studies in Population 30(1): 221–240. https://doi.org/10.25336/P6F01D

Appendix

Table A1 Description of control variables by parental death during childhood: French cohorts born 1946–66

Table A2 Models of level of education and couple experience by parental death during childhood: French men and women born 1946–66

Table A3 Poisson regression of number of children (among parents) by parental death during childhood: French men and women born 1946–66