ABSTRACT

The management of patients with chronic pain is one of the most important issues In medicine and public health. Chronic pain conditions cause substantial suffering for patients, their significant others and society over years and even decades and increases healthcare utilization resources including the cost of medical care, loss of productivity and provision of disability services. Primary care providers are at the frontline in the identification and management of patients with chronic pain, as the majority of patients enter the healthcare system through primary care and are managed by primary care providers. Due to the complexity of chronic pain and the range of issues involved, the accurate diagnosis of the causes of pain and the formulation of effective treatment plans presents significant challenges in the primary care setting. In this review, we use the classification of pain types based on pathophysiology as the template to guide the assessment, treatment, and monitoring of patients with chronic pain conditions. We outline key methods that can be used to efficiently and accurately diagnose the putative pathophysiological mechanisms underlying chronic pain conditions and describe how this information should be used to tailor the treatment plan to meet the patient’s needs. We discuss methods to evaluate patients and the impact of treatment plans over a series of consultations, with a particular focus on strategies to improve the patient’s ability to self-manage their pain and related symptoms and perform daily functions despite persistent pain. Finally, we introduce the mnemonic RATE (Recognize, Assess, Treat, and Evaluate) as a general strategy that healthcare providers can use to aid their management of patients presenting with chronic pain.

1. Introduction

Pain is defined as ‘an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with, or resembling that associated with, actual or potential tissue damage’ [Citation1]. Pain is a personal experience that is influenced to varying degrees by biological, psychological, and social factors [Citation1]. Based on data from the 2016 National Health Interview Survey, an estimated 20.4% of the adult United States (US) population (50 million people) reported experiencing chronic pain, defined as having ‘pain on every day or most days over the past six months.’ An estimated 8% of US adults (19.6 million people) reported ‘high impact chronic pain,’ defined as pain ‘limiting life or work activities on most days or every day during the past six months’ [Citation2]. In 2011, the economic cost of chronic pain was estimated to range from $560–$635 billion/year for medical care, lost productivity, and disability services, making it one of the most important issues in medicine and public health [Citation3]. These figures, however, do not do justice to the incalculable human suffering for both patients and their significant others caused by the presence of persistent pain that extends over years and even decades.

It is estimated that chronic non-cancer pain accounts for 57% of all healthcare encounters [Citation4] and for 16.2% of all adult outpatient visits in 2014, increasing from 11.3% in 2000 [Citation5]. The majority of patients with pain as their presenting symptom enter the healthcare system through primary care, with over half of all patients with chronic pain conditions being managed by primary care providers (PCPs) [Citation6]. Thus, PCPs are at the frontline in the identification and management of patients with chronic pain. The accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of pain and formulation of effective treatment plans present significant challenges given the complexity of chronic pain, the multitude of issues that must be addressed by PCPs, and the constraints posed by the time limitations of visits and the availability of resources [Citation7–9].

The diagnostic criteria for chronic pain were defined by the Analgesic, Anesthetic, and Addiction Clinical Trial Translations, Innovations, Opportunities, and Networks (ACTTION) and the American Pain Society (APS), who developed the ACTTION-APS Pain Taxonomy (AAPT) [Citation10]. The AAPT outlines 5 dimensions that should be considered when assessing patients with chronic pain conditions: (1) core diagnostic criteria; (2) common features; (3) common medical and psychiatric comorbidities; (4) neurobiological, psychosocial, and functional consequences; and (5) putative neurobiological, and psychosocial mechanisms, risk factors, and protective factors.

In this article, we focus on the putative neurobiological and psychosocial mechanisms, risk factors, and protective factors outlined in the fifth dimension of the AAPT. However, it should be noted that each of the other 4 dimensions are equally important and should be included in consideration of patients presenting with chronic pain and associated symptoms. We use the classification of pain types based on pathophysiology, first introduced by Stanos et al [Citation11], as the template to guide the assessment, treatment, and ongoing monitoring of patients with chronic pain. We outline key methods that are used to efficiently and accurately diagnose and categorize the diverse pain mechanisms involved and describe how this information should be used to customize a treatment plan to meet the patient’s needs. We also discuss methods used to evaluate the impact of treatment plans over the course of multiple consultations. In the absence of a cure, we particularly emphasize strategies to improve the patient’s ability to self-manage their pain and related symptoms and perform daily functions despite persistent pain. Finally, we introduce the mnemonic RATE (Recognize, Assess, Treat, and Evaluate) as a general strategy that PCPs can use to aid their management of patients presenting with chronic pain.

2.0 Classification of pain types based on putative mechanisms

The perception of pain is typically initiated by the activation of specific receptors, termed nociceptors, located along peripheral sensory neurons. If the stimulation of nociceptors is sufficient to cross the threshold for sensory neuron activation, nociceptive signals are transmitted from the periphery to the central nervous system (CNS) via peripheral nerves to the spinal cord. Ascending pathways transmit the signals to the higher centers of the CNS, where they are processed and perceived by the individual as pain. Descending signals from higher CNS regions act to balance the nociceptive input at the level of the spinal cord, ensuring the system retains its ability to perceive novel stimuli and preventing chronic activation [Citation12,Citation13].

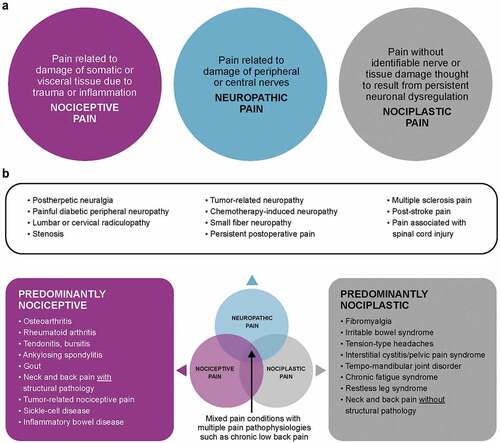

A critical factor in the treatment of patients with chronic pain is the correct diagnosis of the type of pain associated with their condition. Originally proposed by Stanos et al [Citation11], the classification of pain types by putative pathophysiology (i.e. nociceptive, neuropathic, nociplastic or sensory hypersensitivity, and mixed; ) provides insights into the most likely underlying causes of pain and guides PCPs to determine the most appropriate treatments. It is important to acknowledge that although these classifications are based exclusively on physical features, they also involve a range of psychosocial and behavioral factors that may mediate or moderate patients’ presentation and experience, and are incorporated in the biopsychosocial model and the 5 dimensions outlined in the AAPT classification [Citation10].

Nociceptive pain is defined by damage to somatic or visceral tissue due to trauma or inflammation, which leads to the acute activation of peripheral nociceptors [Citation11]. Chronic activation of peripheral nociceptors in conditions such as osteoarthritis (OA) and low back pain (LBP) may modify the activity of sensory neurons. This results in a decreased threshold for sensory neuron activation and/or an increase in their response to a given stimuli, increasing the perception of pain [Citation14].

Neuropathic pain is characterized by damage to peripheral or central nerves, identified by either objective means or inferred [Citation11]. Damage to the peripheral nervous system in conditions such as postherpetic neuralgia and painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy increases the activity of the pain pathway at the level of spinal cord integration. Central nerve damage in conditions such as spinal cord injury and radiculopathy drives activity of the pain pathway within the CNS. The increased activation of the pain pathway is coupled with a loss of inhibition from higher CNS regions, leading to the increased perception of pain [Citation15].

Nociplastic pain, also known as sensory hypersensitivity, is believed to arise from the altered perception of pain despite the absence of any clear evidence of peripheral nociceptor activation or damage to the nervous system [Citation16]. A common feature of nociplastic conditions such as fibromyalgia, irritable bowel syndrome, and tension-type headaches is the amplified processing of and/or decreased inhibition of pain signals in the nervous system, which leads to persistent neuronal dysregulation, an increase in pain perception, and lowering of pain thresholds [Citation17,Citation18].

In many instances, chronic pain is caused by a combination of more than one pathophysiological mechanism, and thus are termed mixed pain states. Common causes of mixed pain states include conditions traditionally thought of as largely nociceptive, such as chronic LBP and OA [Citation11].

3. Assessment and treatment of patients with chronic pain conditions

3.1 Step 1 – recognizing the type of pain by pathophysiological mechanisms and psychosocial factors

Evaluation of patients with chronic pain conditions requires a multimodal, comprehensive approach. Careful consideration of all comorbidities and social and historical determinants of health are essential. Pain conditions are rarely presented in isolation, and these may be secondary to, or exacerbated by, other underlying physiological and psychosocial problems, diagnosed or otherwise. Moreover, patients reside within broader social and environmental contexts that may influence their experiences, responses to symptoms, responses to treatments, and the impact of chronic pain on physical and emotional functioning. Specific psychosocial characteristics, such as distress, trauma, fear or catastrophizing, confer vulnerability for the perception of pain, the transition from acute to chronic pain states, and for the development of pain related disability in chronic pain conditions [Citation19,Citation20]. Knowledge of the presence of these factors should be acknowledged by PCPs and discussed with patients. Depending on the severity, providers should consider referral to trained professionals who can target these psychological factors. Consequently, the role of psychological factors should be considered for patients throughout the pain continuum from acute pain, subacute pain, and to chronic pain conditions and addressed as appropriate by PCPs or by referral to professionals with training in the use of evidence based targeted interventions [Citation19,Citation20]

3.1.1 Patient history as a diagnostic tool

In addition to determining the general health status of the patient and their medical history, a basic pain assessment detailing the location of pain, severity, duration, description, exacerbating and mitigating factors, impact, as well as patient understanding and expectations for their condition and treatment should be conducted [Citation11]. In particular, the patient’s description of their experience of pain may be informative for the diagnosis of pain type (). Understanding how pain affects the patient’s ability to perform daily functions and activities and its emotional impact should be a focus of the consultation. Discussion of treatments prescribed by other healthcare professionals as well as the measures taken by the patient to manage his or her pain, and their success using these methods, are important aspects of assessment [Citation21]. Although previous diagnosis may be informative, healthcare providers should focus on their independent assessments as many patients carry forward incorrect diagnoses, which perpetuates an inappropriate treatment cycle.

Table 1. Diagnosis of pain type from patient’s description of symptoms.

3.1.2 Tools for the identification of pathophysiological subtypes of pain

In addition to detailed histories, physical examinations should be used to initially assess the patient. Laboratory and imaging tests may be considered to confirm diagnoses as appropriate. To complement these assessments, a number of patient self-report measures have been developed to identify and describe the type of pain experienced by patients with chronic pain. Several brief validated clinical tools have been developed and can be used to provide a structure to the consultation with the patient ()[Citation22–27]. Many of these tools can be completed independently by the patient, providing the opportunity to maximize the available consultation time spent on the discussion of the patient’s wellbeing and treatment options [Citation22–24]. Diagnostic tools that combine a patient interview, self-report questionnaires, and a brief structured clinical examination may be particularly appropriate for PCPs who are experiencing difficulty in diagnosing the specific type of pain the patient may experience [Citation25,Citation27]. The examples of self-report tools noted in have been validated for clinical use, their results should be integrated with the patient’s history, physical examination, and diagnostic tests to develop a comprehensive diagnosis and guide treatment planning.

Table 2. Examples of tools for the diagnosis of pain type.

3.2 Step 2 – assessing the effect of pain on the patient

As noted, a central focus of the assessment of patients with chronic pain should be the effect that the condition has on their physical and emotional functioning [Citation28]. In addition to the information gathered from detailed patient histories, a number of self-report measures have been developed to quantify the effect of chronic pain on physical function ()[Citation29–34]. Specific measures have been developed to assess functional impairments in common chronic pain conditions, such as OA [Citation29], fibromyalgia [Citation32], LBP [Citation30,Citation31], and neck pain [Citation33]. These instruments can be completed in a few minutes and do not require provider administration. Similarly, PCPs should aim to determine the effect of chronic pain conditions on the emotional functioning, coping, and the health-related quality of life of their patients using brief self-report measures that have been validated for use in practice, several of these are included in [Citation21,Citation35–46]. Measures such as those listed in should be used to provide important information that complements patient histories and examinations, allowing PCPs to identify the aspects of physical and emotional functioning, patient beliefs, and ability to cope that are particularly affected. The use of these measures during the first patient consultations provides a baseline against which to document the progress of interventions.

Table 3. Examples of tools to assess physical functioning, emotional functioning, patients’ beliefs and coping, and multidimensional measures.

3.3 Step 3 – treating according to pain type

Over a series of consultations, PCPs should come to understand the type of pain experienced by patients and the impact it has on their daily life. This information should be used to inform a personalized treatment plan, which aims to reduce the intensity and perception of pain, reduce emotional distress, restore physical function, and improve health-related quality of life using a combination of non-pharmacological therapies and the most appropriate drug treatments [Citation48–50].

3.3.1 Self-management of chronic pain based on the needs of the individual patient

Providing patients with education about their condition and the role of their beliefs and expectations of progress are crucial, as these factors will impact the acceptance and response to treatment in the absence of a cure. Patients should be encouraged and supported in the self-management of their condition [Citation48,Citation49]. By understanding how patients have tried to manage their pain and how successful these measures have been, PCPs can acknowledge these efforts and establish and encourage goal-setting strategies to manage physical activity and emotional functioning despite symptoms and limitations posed by pain conditions. This may include encouraging breaking up daily tasks to prevent overexertion and reduce flare-ups, while also providing a goal-based structure to gradually increase physical function and increase pleasant activity planning. In addition to managing physical activity, developing and monitoring a plan to improve sleep hygiene may be beneficial, as lack of sleep is common in patients with pain [Citation51,Citation52].

3.3.2 Non-pharmacological therapies

A range of individual and team-based, non-pharmacological therapies should be considered for inclusion in the plan to complement the patient’s self-management efforts [Citation48,Citation53].

The measures included in , sections b and c can be particularly useful in helping to understand patients’ emotional functioning, how they cope with pain, and their beliefs regarding how able they are to manage their symptoms and their lives despite the presence of chronic pain. Patients identified as experiencing emotional distress or pain catastrophizing may particularly benefit from interventions specifically designed to address the underlying psychological factors, improve the perception of their condition, and provide strategies to cope with the associated symptoms and limitations. These measures may include cognitive and behavioral therapies, including coping skills training in relaxation and distraction methods, and education in goal setting, activity pacing, and problem-solving strategies. As discussed previously, these treatments provide an opportunity to address the psychological basis of pain maintenance and the development of pain related disability [Citation19,Citation20].

In addition to psychologists, research has demonstrated that nurses and physical therapists can successfully incorporate these approaches within their patient interactions [Citation54–57].

Experienced practitioners can deliver a range of noninvasive nonpharmacological treatments, many of which have been shown to reduce pain and restore physical function in patients with diverse chronic pan conditions. For example, a recent comparative effectiveness review of 233 randomized controlled trials by the US Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality demonstrated that exercise, cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness practices, massage and multidisciplinary rehabilitation consistently improved physical function and pain in primarily musculoskeletal and nociplastic chronic pain conditions [Citation58]. Specifically, exercise was shown to be beneficial for patients with LBP, neck pain, OA of the hip or knee and fibromyalgia [Citation58]. Additionally, at least one of cognitive-behavioral therapy, mindfulness, psychological therapy, or mind-body practices were shown to be effective for each of these conditions [Citation58]. Several reviews of non-pharmacological therapies for patients with neuropathic pain conditions concluded that the evidence for these interventions was weak, limited, or insufficient, suggesting that further research is required for patients with these conditions [Citation15,Citation59–61].

3.3.3 Pharmacological treatments to target pain pathophysiology

The pharmacological treatment of chronic pain conditions should be initially guided by the severity of pain reported and the diagnosis of pain type ().

Table 4. Pharmacological treatments based on pain classification.

Commonly prescribed medications for primarily nociceptive pain include nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and acetaminophen [Citation11]. In certain cases, NSAIDs and acetaminophen may be used in combination with corticosteroids or biologics targeted to mediators of the inflammatory response [Citation11]. These medications function to reduce the inflammatory environment caused by tissue damage, reducing the sensitization of nociceptors and decreasing the perception of pain [Citation11].

The most commonly recommended treatments for neuropathic and nociplastic pain conditions include antiepileptic drugs, serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, and tricyclic antidepressants. These drugs restore the balance of excitation and inhibition in the pain pathway, thereby reducing the effects of primary nerve damage on altered pain perception [Citation15,Citation62]. Traditional analgesics such as muscle relaxants, NSAIDs, acetaminophen and opioids have been shown to be less effective for nociplastic pain conditions than pain caused by other mechanisms [Citation18].

The recommended treatments for common mixed pain conditions such as chronic LBP [Citation48] and OA [Citation49,Citation63] are NSAIDs, reflecting the contribution of nociceptive pathophysiology in these conditions. Patients with mixed pain conditions may also benefit from combination drug therapy to target the underlying pathophysiologies identified [Citation64].

In all cases, the efficacy and safety of treatments initiated should be assessed on an individual basis and the treatment plan should be modified according to the patient’s response.

3.4 Step 4 – evaluating patient response to treatment

3.4.1 Tools for assessing pain and pain reduction

Since complete elimination of pain is rarely possible, a primary outcome of the treatment plan is the reduction of pain intensity and the management of patients’ expectations on this important goal [Citation65,Citation66]. Many tools have been developed to quickly and reliably quantify the perception of acute pain severity, including the Numerical Pain Rating Scale (NPRS; e.g. 0 [none] to 10 [worst possible]) [Citation67], Visual Analog Scale (VAS; e.g. 0–10 cm line with anchors at each end) [Citation68], and the Verbal Rating Scale (VRS; e.g. None, Mild, Moderate, Severe) [Citation69]. It is important to acknowledge that these scales have limitations for quantification of chronic pain; they are subjective and rely on the patient’s ability to accurately and reproducibly report their pain over the course of several consultations [Citation70,Citation71]. Factors such as context (at home vs in provider’s office), activity levels (at rest vs during movement), timing (morning vs evening), as well as the wording (pain on average, pain right now, pain when worst) may influence the patient’s responses. Measures to assess pain should be completed during the initial consultations and used as a baseline to evaluate the effectiveness of the treatment plan.

Large reductions in pain intensity scores are often not achievable in patients with chronic pain conditions, although this is what patients are typically seeking [Citation65,Citation66]. In order to be clinically meaningful, research suggests that an intervention should reduce the perception of pain by approximately 30%; however, many patients hold expectations for much greater pain reduction [Citation65,Citation66]. Given the limitations of treatments, patients should be educated on the inability to greatly reduce pain in chronic pain conditions and expectations for pain relief should be openly discussed both at the onset of and during treatment. Realistic pain reduction goals should be detailed in treatment plans and monitored regularly using the tools described above. Patients’ acceptance of the reality of these limitations is important to prevent discouragement.

3.4.2 Assessing the functional and health-related quality of life outcomes of treatment plans

In addition to the reduction in the perception of pain, the impact of the treatment plan on the restoration of the patient’s physical and emotional function should be an important focus for healthcare providers [Citation53,Citation72,Citation73]. As noted previously for pain reduction, realistic goals for improved physical function should be discussed with patients at the beginning of their treatment and regularly monitored through postintervention follow-up consultations. The functional goals of the treatment plan should be modified over time according to the patient’s response, in order to maximize the benefit of the interventions. Similarly, the goals for improving emotional functioning and quality of life should be discussed at the beginning of treatment and modified according to the patient’s response. Patients’ lack of improvement in emotional functioning and increased distress should be considered and might serve as the impetus for a consultation with a mental health professional.

A combination of interviews during treatment and brief self-report measures can be used to determine the impact of the treatment plan on the perception of pain and the physical and emotional functioning of the patient (). Healthcare providers should use this information to evaluate the effectiveness of their interventions and guide their strategy for progression and revision of treatment as needed. The modification of the treatment plan should initially focus on maximizing the benefit of self-managed and team-based non-pharmacological therapy, guided by the patient’s response, expectations, and goals.

Interventions should be reviewed according to their efficacy in pain reduction and the improvement of physical function and health-related quality of life, as well as the tolerability of the therapies. Progression to second- or third-line pharmacological treatments should be reserved for cases where appropriate non-pharmacological and first-line pharmacological treatments have been explored and provided inadequate benefit (). In particular, opioids should only be initiated for patients who have been appropriately assessed for risk of substance abuse, and after the expectations for treatment have been discussed [Citation11]. There are several brief measures that have been developed to assess the risk of opioid misuse, such as the Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain-Revised (SOAPP-R) [Citation74]. Opioids are potential third-line treatments for patients with nociceptive, neuropathic, and mixed pain but should be avoided in patients with nociplastic pain [Citation11,Citation15,Citation49,Citation62]. Regular monitoring of the effects of opioid medication should be performed throughout a trial period to determine the appropriateness for the patient and their specific condition [Citation11]. PCPs might consider using the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM) to monitor opioid use and misuse for patients who are placed on opioid therapy [Citation75]. The plan for initiating long-term opioid therapy should be discussed with patients as an initial trial that will be adapted and possibly terminated depending on the effects of the treatment, including potential adverse effects.

4.0 RATE, a general strategy for the treatment of patients with chronic pain

Based on what we have described above, we propose the use of the mnemonic RATE as a general strategy for healthcare providers to use during their consultations with patients with chronic pain (). This mnemonic prompts healthcare providers to firstly Recognize the type of pain a patient is experiencing by its pathophysiology, with an understanding of how the pain pathway might be affected and the key psychosocial mediators involved. Secondly, healthcare providers should Assess the patient using a combination of focused history taking, physical examination, and diagnostic tools to understand the patient’s perception of pain, its impact on mood and daily function, and their beliefs and expectations. This information should be used to Treat the patient, using a combination of self-management and non-pharmacological therapy delivered by specialists, in addition to the most appropriate pharmacological treatments. Finally, postintervention consultations should be used to Evaluate and reassess patient improvements in pain and physical and emotional functional outcomes with the brief measures described in and and postintervention patient histories. Monitoring patients’ progress throughout treatment is essential to inform the treatment plan and adaptations required based on pain, adverse effects, and physical and emotional functioning.

5. Conclusion

The management of patients with chronic pain is challenging and can be time-consuming. Developing a specific strategy is essential for the efficient and effective treatment of these patients. The practical guidance introduced here highlights the issues that PCPs should seek to address in their consultations with and treatment of patients with chronic pain. Initial consultations should focus on understanding the pathophysiological mechanisms that underlie the patient’s pain, how it affects their daily activities and emotional state, and if any self-management techniques are appropriate and likely to be effective. This information can be obtained by focusing patient interviews and history taking. Physical examinations and diagnostic tests should be used in combination with validated self-report measures to assist in the assessment of the type of pain and its impact on the patient. Although previous diagnoses may be informative, an independent clinical evaluation should be conducted to avoid continuation of an inappropriate treatment cycle.

The relevant information obtained from histories, examinations, and patient self-reports should inform and guide the initial treatment plan, which incorporates patient- and specialist-led non-pharmacological therapies in partnership with the most appropriate pharmacological treatment based on the underlying pathophysiology. The treatment plan should have clear goals for pain reduction and the improvement of physical and emotional functioning that are discussed with the patient to support the establishment of realistic goals, expectations for the patient central role in self-management, and the likely benefits of various treatments. Resources and appropriate referral sources that are available to supplement primary care should be identified in advance.

Regular monitoring and postintervention consultations should evaluate the impact of the treatment plan on the pain associated with the condition, its impact on physical and emotional function, and health-related quality of life. This information can be obtained during treatment, through postintervention histories and available measures that allow PCPs to efficiently quantify pain and physical and emotional functioning over time. Based on these evaluations and the progress observed, treatment plans should be revised and optimized for each patient, as appropriate.

The evolving team-based care model can and should benefit patients by augmenting in-person interactions with virtual consultations, where appropriate. Within this more comprehensive care model, additional resources and professional support also facilitate greater adherence to the behavioral, occupational, and physical therapies included in the treatment plan by delivering them in a setting that is convenient for the patient.

As PCPs are typically the first to evaluate patients with chronic pain, we propose the overview provided in this article including the use of the mnemonic RATE – Recognize, Assess, Treat, and Evaluate as a memory aid for use in guiding clinical practice.

Declaration of funding

Development of this manuscript was funded by Pfizer and Eli Lilly and Company.

Disclosure of any financial/other conflicts of interest

Kevin B. Gebke has no disclosures to report. Bill McCarberg has acted as an advisor for Eli Lilly and Company, Scilex and Averitas and holds stock in Johnson and Johnson. Erik Shaw received personal compensation from SPR Therapeutics for consultancy, Tera Sera, Boston Scientific, and BDSI for speaking and Pfizer and Eli Lilly and Company for serving on an advisory board. Dennis C. Turk has received research grants and contracts from the US Food and Drug Administration and US National Institutes of Health and has received compensation for consulting on clinical trial and patient preferences from AccelRx, Eli Lilly and Company, Flexion, Novartis/GlaxoSmithKline, and Pfizer. Wendy L. Wright has acted as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline and served on a speakers’ bureau for AbbVie, Biohaven, Pfizer, Merck and Sanofi. David Semel is an employee and stockholder of Pfizer. The authors have no other relevant conflicts of interest to disclose. Peer reviewers on this manuscript have no relevant financial or other relationships to disclose.

Biographical note

Kevin B. Gebke is the Chair of the Department of Family Medicine, Indiana University School of Medicine and President, IU Health Community Medicine.

Bill McCarberg is Founder of the Chronic Pain Management Program for Kaiser Permanente (retired) in San Diego, California. He is past president of the American Academy of Pain Medicine and president of the Western Pain Society. He is also Adjunct Assistant Clinical Professor at the University of California at San Diego School Medicine.

Erik Shaw is an interventional pain management specialist and Medical Director of the Shepherd Spine and Pain Institute in Atlanta, Georgia.

Dennis C Turk is the John and Emma Bonica Chair of Anesthesiology and Pain Research at the University of Washington Medical School in Seattle, Washington.

Wendy L Wright is an adult and family Nurse Practitioner and the owner of two, nurse practitioner owned and operated clinics within New Hampshire.

David Semel is the US tanezumab Senior Medical Director for Pfizer, he has worked in the pain therapeutic area for 22 years.

Acknowledgments

Medical writing support was provided by Steven Moore, PhD, of Engage Scientific Solutions and was funded by Pfizer and Eli Lilly & Company.

References

- Raja SN, Carr DB, Cohen M, et al. The revised international association for the study of pain definition of pain: concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain. 2020;161(9):1976–1982.

- Dahlhamer J, Lucas J, Zelaya C, et al. Prevalence of chronic pain and high-impact chronic pain among adults - United States, 2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(36):1001–1006.

- Institute of Medicine (US). Committee on advancing pain research, care, and education. relieving pain in America: a blueprint for transforming prevention, care, education, and research. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2011.

- St Sauver JL, Warner DO, Yawn BP, et al. Why patients visit their doctors: assessing the most prevalent conditions in a defined American population. Mayo Clin Proc. 2013;88(1):56–67.

- Rasu RS, Vouthy K, Crowl AN, et al. Cost of pain medication to treat adult patients with nonmalignant chronic pain in the United States. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2014;20(9):921–928.

- Breuer B, Cruciani R, Portenoy RK. Pain management by primary care physicians, pain physicians, chiropractors, and acupuncturists: a national survey. South Med J. 2010;103(8):738–747.

- McCarberg BH. Pain management in primary care: strategies to mitigate opioid misuse, abuse, and diversion. Postgrad Med. 2011;123(2):119–130.

- Mezei L, Murinson BB. Johns hopkins pain curriculum development team. pain education in North American medical schools. J Pain. 2011;12(12):1199–1208.

- O’Rorke JE, Chen I, Genao I, et al. Physicians’ comfort in caring for patients with chronic nonmalignant pain. Am J Med Sci. 2007;333(2):93–100.

- Dworkin RH, Bruehl S, Fillingim RB, et al. Multidimensional diagnostic criteria for chronic pain: introduction to the ACTTION–American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (AAPT). J Pain. 2016;17(9):T1–9.

- Stanos S, Brodsky M, Argoff C, et al. Rethinking chronic pain in a primary care setting. Postgrad Med. 2016;128(5):502–515.

- Yam MF, Loh YC, Tan CS, et al. General pathways of pain sensation and the major neurotransmitters involved in pain regulation. Int J Mol Sci. 2018;19(8):2164.

- Basbaum AI, Bautista DM, Scherrer G, et al. Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pain. Cell. 2009;139(2):267–284.

- Ji RR, Nackley A, Huh Y, et al. Neuroinflammation and central sensitization in chronic and widespread pain. Anesthesiology. 2018;129(2):343–366.

- Colloca L, Ludman T, Bouhassira D, et al. Neuropathic pain. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2017;3:17002.

- Kosek E, Cohen M, Baron R, et al. Do we need a third mechanistic descriptor for chronic pain states? Pain. 2016;157(7):1382–1386.

- Sluka KA, Clauw DJ. Neurobiology of fibromyalgia and chronic widespread pain. Neuroscience. 2016;338:114–129.

- Fitzcharles MA, Cohen SP, Clauw DJ, et al. Nociplastic pain: towards an understanding of prevalent pain conditions. Lancet. 2021;397(10289):2098–2110.

- Meints SM, Edwards RR. Evaluating psychosocial contributions to chronic pain outcomes. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2018;87(Pt B):168–182.

- Edwards RR, Dworkin RH, Sullivan MD, et al. The role of psychosocial processes in the development and maintenance of chronic pain. J Pain. 2016;17(9 Suppl):T70–92.

- Dansie EJ, Turk DC. Assessment of patients with chronic pain. Br J Anaesth. 2013;111(1):19–25.

- Portenoy R. Development and testing of a neuropathic pain screening questionnaire: ID Pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(8):1555–1565.

- Freynhagen R, Baron R, Gockel U, et al. painDETECT: a new screening questionnaire to identify neuropathic components in patients with back pain. Curr Med Res Opin. 2006;22(10):1911–1920.

- Wolfe F, Clauw DJ, Fitzcharles MA, et al. Fibromyalgia criteria and severity scales for clinical and epidemiological studies: a modification of the ACR preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia. J Rheumatol. 2011;38(6):1113–1122.

- Bouhassira D, Attal N, Alchaar H, et al. Comparison of pain syndromes associated with nervous or somatic lesions and development of a new neuropathic pain diagnostic questionnaire (DN4). Pain. 2005;114(1–2):29–36.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Revicki DA, et al. Development and initial validation of an expanded and revised version of the short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ-2). Pain. 2009;144(1–2):35–42.

- Bennett M. The LANSS pain scale: the leeds assessment of neuropathic symptoms and signs. Pain. 2001;92(1–2):147–157.

- Taylor AM, Phillips K, Patel KV, et al. Assessment of physical function and participation in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT/OMERACT recommendations. Pain. 2016;157(9):1836–1850.

- Bellamy N, Buchanan WW, Goldsmith CH, et al. Validation study of WOMAC: a health status instrument for measuring clinically important patient relevant outcomes to antirheumatic drug therapy in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee. J Rheumatol. 1988;15(12):1833–1840.

- Roland M, Morris R. A study of the natural history of back pain. Part I: development of a reliable and sensitive measure of disability in low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 1983;8(2):141–144. Phila Pa 1976.

- Fairbank JC, Pynsent PB. The oswestry disability index. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2000;25(22):2940–2952.

- Burckhardt CS, Clark SR, Bennett RM. The fibromyalgia impact questionnaire: development and validation. J Rheumatol. 1991;18(5):728–733.

- Vernon H, Mior S. The neck disability index: a study of reliability and validity. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 1991;14(7):409–415.

- Rose M, Bjorner JB, Gandek B, et al. The PROMIS physical function item bank was calibrated to a standardized metric and shown to improve measurement efficiency. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67(5):516–526.

- Cameron IM, Crawford JR, Lawton K, et al. Psychometric comparison of PHQ-9 and HADS for measuring depression severity in primary care. Br J Gen Pract. 2008;58(546):32–36.

- Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JB, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(10):1092–1097.

- McCracken LM, Dhingra L. A short version of the Pain Anxiety Symptoms Scale (PASS-20): preliminary development and validity. Pain Res Manag. 2002;7(1):45–50.

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532.

- Romano JM, Jensen MP, Turner JA. The chronic pain coping inventory-42: reliability and validity. Pain. 2003;104(1–2):65–73.

- Tait RC, Chibnall JT. Development of a brief version of the survey of pain attitudes. Pain. 1997;70(2–3):229–235.

- Woby SR, Roach NK, Urmston M, et al. Psychometric properties of the TSK-11: a shortened version of the tampa scale for kinesiophobia. Pain. 2005;117(1–2):137–144.

- Cleeland CS, Ryan KM. Pain assessment: global use of the brief pain inventory. Ann Acad Med Singap. 1994;23(2):129–138.

- Nicholas MK. The pain self-efficacy questionnaire: taking pain into account. Eur J Pain. 2007;11(2):153–163.

- Krebs EE, Lorenz KA, Bair MJ, et al. Development and initial validation of the PEG, a three-item scale assessing pain intensity and interference. J Gen Intern Med. 2009;24(6):733–738.

- Kroenke K, Yu Z, Wu J, et al. Operating characteristics of PROMIS four-item depression and anxiety scales in primary care patients with chronic pain. Pain Med. 2014;15(11):1892–1901.

- Obradovic M, Lal A, Liedgens H. Validity and responsiveness of EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) versus short form-6 dimension (SF-6D) questionnaire in chronic pain. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:110.

- Sullivan MJL, Bishop SR, Pivik J. The pain catastrophizing scale: development and validation. Psychol Assess. 1995;7(4):524–532.

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive treatments for acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain: a clinical practice guideline from the American college of physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(7):514–530.

- Kolasinski SL, Neogi T, Hochberg MC, et al. American college of rheumatology/arthritis foundation guideline for the management of osteoarthritis of the hand, hip, and knee. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(2):220–233. 2019.

- Arnold LM, Clauw DJ, Dunegan LJ, et al. A framework for fibromyalgia management for primary care providers. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012;87(5):488–496.

- Smith MT, Haythornthwaite JA. How do sleep disturbance and chronic pain inter-relate? Insights from the longitudinal and cognitive-behavioral clinical trials literature. Sleep Med Rev. 2004;8(2):119–132.

- Finan PH, Goodin BR, Smith MT. The association of sleep and pain: an update and a path forward. J Pain. 2013;14(12):1539–1552.

- Schneiderhan J, Clauw D, Schwenk TL. Primary care of patients with chronic pain. JAMA. 2017;317(23):2367–2368.

- Main CJ, George SZ. Psychologically informed practice for management of low back pain: future directions in practice and research. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):820–824.

- Broderick JE, Keefe FJ, Bruckenthal P, et al. Nurse practitioners can effectively deliver pain coping skills training to osteoarthritis patients with chronic pain: a randomized, controlled trial. Pain. 2014;155(9):1743–1754.

- Foster NE, Delitto A. Embedding psychosocial perspectives within clinical management of low back pain: integration of psychosocially informed management principles into physical therapist practice–challenges and opportunities. Phys Ther. 2011;91(5):790–803.

- Beissner K, Henderson CR Jr., Papaleontiou M, et al. Physical therapists’ use of cognitive-behavioral therapy for older adults with chronic pain: a nationwide survey. Phys Ther. 2009;89(5):456–469.

- Skelly AC, Chou R, Dettori JR, et al. Noninvasive nonpharmacological treatment for chronic pain: a systematic review update. AHRQ Comparative Effectiveness Reviews. Rockville (MD). 2020

- Boldt I, Eriks-Hoogland I, Brinkhof MW, et al. Non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in people with spinal cord injury. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014; 2014(11):CD009177

- Amatya B, Young J, Khan F. Non-pharmacological interventions for chronic pain in multiple sclerosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2018;12. CD012622.

- Dworkin RH, O’Connor AB, Kent J, et al. Interventional management of neuropathic pain: neuPSIG recommendations. Pain. 2013;154(11):2249–2261.

- Macfarlane GJ, Kronisch C, Dean LE, et al. EULAR revised recommendations for the management of fibromyalgia. Ann Rheum Dis. 2017;76(2):318–328.

- Towheed TE, Maxwell L, Judd MG, et al. Acetaminophen for osteoarthritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 2006(1):CD004257

- Freynhagen R, Parada HA, Calderon-Ospina Ca, et al. Current understanding of the mixed pain concept: a brief narrative review. Curr Med Res Opin. 2019;35(6):1011–1018.

- Farrar JT, Young JP Jr., LaMoreaux L, et al. Clinical importance of changes in chronic pain intensity measured on an 11-point numerical pain rating scale. Pain. 2001;94(2):149–158.

- Dworkin RH, Turk DC, Wyrwich KW, et al. Interpreting the clinical importance of treatment outcomes in chronic pain clinical trials: IMMPACT recommendations. J Pain. 2008;9(2):105–121.

- Childs JD, Piva SR, Fritz JM. Responsiveness of the numeric pain rating scale in patients with low back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2005;30(11):1331–1334. Phila Pa 1976.

- Hawker Ga, Mian S, Kendzerska T, et al. Measures of adult pain: visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken). 2011;63(11 Suppl):S240–252.

- Haefeli M, Elfering A. Pain assessment. Eur Spine J. 2006;15(1 Suppl):S17–24.

- Breivik H, Borchgrevink PC, Allen SM, et al. Assessment of pain. Br J Anaesth. 2008;101(1):17–24.

- Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I. Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1983;16(1):87–101.

- Turk DC, Dworkin RH, Revicki D, et al. Identifying important outcome domains for chronic pain clinical trials: an IMMPACT survey of people with pain. Pain. 2008;137(2):276–285.

- Smith TO, Hawker GA, Hunter DJ, et al. The OMERACT-OARSI core domain set for measurement in clinical trials of hip and/or knee osteoarthritis. J Rheumatol. 2019;46(8):981–989.

- Butler SF, Fernandez K, Benoit C, et al. Validation of the revised Screener and Opioid Assessment for Patients with Pain (SOAPP-R). J Pain. 2008;9(4):360–372.

- McCaffrey SA, Black RA, Villapiano AJ, et al. Development of a brief version of the Current Opioid Misuse Measure (COMM): the COMM-9. Pain Med. 2019;20(1):113–118.