Abstract

Objective: One way healthcare organisations can support their staff is through supervision. Supervision is typically defined as a process in which professionals receive support and guidance from more experienced colleagues. In this brief review we propose a tailored protocol for supporting support workers during a pandemic. Method: We collected narrative data from difference sources including a systematic meta ethnography and used expert advise in order to tailor the protocol. Results: This protocol can be used by management teams (e.g., senior support workers, team leaders, registered managers, and operation managers) without any prior experience of supervision. The protocol suggested includes a template with easy-to-follow instructions. Conclusions: It provides an easy step-by-step guide that simplifies the process whilst maintaining the depth needed to ensure effective supervision.

BACKGROUND

Supervision

During the COVID-19 pandemic, it has become apparent that healthcare professionals worldwide (e.g., doctors, nurses, and allied healthcare professionals) need additional organisational support (e.g., from senior management) to cope and deal with a number of work-related and personal demands. Furthermore, the consequences of the pandemic have been experienced differentially across the globe due to national health policies, prevalence of COVID-19, population-wide vaccination uptake rates, and availability of personal protective equipment (PPE; World Health Organisation [WHO], Citation2022).

One way healthcare organisations can support their staff is through supervision. Supervision is typically defined as a process in which professionals receive support and guidance from more experienced colleagues (Gennis & Gennis, Citation1993; Lee et al., Citation2019). Supervision is an activity that is fundamentally interlinked with the training and professional development of supervisees with many international countries such as the UK, Canada, the USA, and New Zealand adopting this approach in order to monitor, support, and enhance employee performance (Baines et al., Citation2014; Lee et al., Citation2019; Martin et al., Citation2022).

Supervision protocols and policies vary from organisation to organisation. The purpose of the supervision is generally to establish the accountability of the worker to the organisation and to promote the worker’s professional development (Martin et al., Citation2017).

Supervision within the Healthcare Sector

Supervision within health care is a developmental process in which experienced staff members guide and support less experienced staff aiming to improve their overall performance and quality of care (Snowdon et al., Citation2017).

The effectiveness of healthcare supervision is measured by the effectiveness of the quality of care delivered, the value of supervision, skills improvement, and the quality of support from the supervisor (Gardner et al., Citation2022; Kilbertus et al., Citation2019). Clinical supervision is associated with more effective care (Snowdon et al., Citation2017), health workers’ motivation (Brown et al., Citation2020), and also reduces patient complications (Tomlinson, Citation2015). A core driver for this reduction seems to be the link between supervision and reflective practice. Reflections on critical events and situations such as dissatisfied patients, outcomes that did not go well, well-managed cases, and patient thank you letter (Koshy et al., Citation2017) allow health professionals to improve their own work experience. A study conducted by Natchaba (Citation2020) in the USA suggested that both care coordinators and their supervisors agreed on supervision elements such as (1) importance and value of supervision, (2) finding time, (3) trust and rapport, and (4) supporting remote care coordination. Positive outcomes of the supervision in health care are also discussed by Shklarski and Abrams (Citation2021) with the primary findings suggesting reduced susceptibility to stress during challenging times when supervision is conducted in a positively and timely manner.

A Definition of Supervision

Clinical supervision is essential for professional development and is particularly needed to support staff in a number of key domains including effectiveness at work, physical and mental health, job satisfaction, and personal development (Mclaughlin et al., Citation2019).

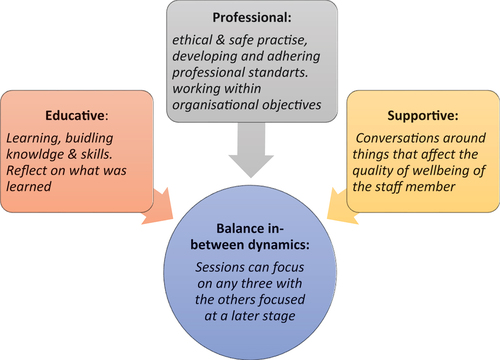

The most widely accepted purpose of clinical supervision in health care established by Proctor in 1986 (Driscoll et al., Citation2019; Lee et al., Citation2019) suggesting that supervision has three main functions: (1) normative (management), (2) formative (educational) and (3) restorative (supportive; Lee et al., Citation2019; Martin et al., Citation2017).

Normative function explores the ethical principles of someone’s work and makes sure that the individual delivers and adheres to quality practices (Lee et al., Citation2019). Formative function is concerned with individual upskilling, including seeking knowledge to increase one’s self-worth and personal development (Brunero & Stein-Parbury, Citation2008). Schultz et al. (Citation2021) reviewed supervision of Canadian healthcare staff during the COVID-19 pandemic focusing on formative functions such as assessing supervisee’s effective use of virtual care platforms, integration of consent in their care, confidentiality aspects, and good communication with patients. Restorative function seeks to prevent or improve signs of exhaustion and emotional burnout in addition to creating a relationship (e.g., supervisor – supervisee) in which the supervisee is valued and understood (O'Donovan et al., Citation2011).

Milne (Citation2007) conducted a systematic review to explore the meaning of clinical supervision. The reason behind this was that the current literature explaining the meaning of supervision was unsatisfactory with no challenge towards the meaning. Therefore, Milne (Citation2007) decided to update the meaning of clinical supervision (see ). The systematic review followed two steps: (1) logical review, where the necessary criteria for an empirical definition were created, and (2) the systematic review. The search revealed 24 studies concerning clinical supervision. The four necessary concepts of a good definition were as follows: precision, specification, operationalisation, and corroboration. Therefore, Milne (Citation2007) was able to propose the definition of clinical supervision according to the studies found:

The formal provision by senior/qualified practitioners of an intense relationship based education and training that is case focused and which supports, directs and guides the work of colleagues (supervisees).

TABLE 1. Analysis of the definition of clinical supervision as outlined by Milne (Citation2007)

MANAGEMENT AND CLINICAL SUPERVISION

The difference between clinical supervision and management supervision lies within the topics and focus of discussion during the supervision. This can be explained further examining the differences outlined in . For example, clinical supervision focuses on specific case discussion, how things went with the patient/service user, any interventions used including their effectiveness, and risk appraisal and management regarding the case. On the other hand, management supervision focuses on any discharge from services, training compliance, overall caseload, annual leave requests etc.

TABLE 2. Clinical and line management supervision

CURRENT SUPERVISION MODELS

The National Health Service (NHS) in the United Kingdom recommends two models of supervision within its organisational policies. The first one is as outlined by Proctor in the chapter “training for the supervision alliance” (Proctor, Citation2010; see ).

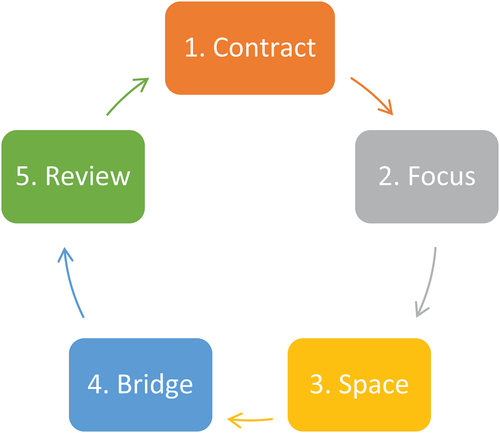

The second model (see ) is proposed by Van Ooijen (Citation2000). Van Ooijen describes supervision as a sequence of stages that have a natural flow starting with:

Contract. Agreement between supervisors (normally, this will be under HR employment contract) and supervisees

Focus. Establishing the issues that the supervisee wishes to discuss. This is when clarification and structure of the supervision take place

Space. Where supervision takes place

Bridge. How to get back to work after or whilst resolving the issues

Review. How to approach future sessions

However, there is no clear evidence that Health and Social Care organisations follow either the above-mentioned or any other models of supervision within their policies or approach.

During the pandemic, it became very crucial to both conduct and receive good-quality supervision in order to support staff at all levels with their coping, offer support, and build a trusting environment during this very difficult time. According to Schultz et al. (Citation2021) during a pandemic, good-quality supervision should include assessing supervisee experience with virtual care, assessing depth of supervision needed, adapting to the right supervision approach, reviewing outcomes of patient care, and creating documentation to assess the learner.

WHAT IS THE PANDEMIC SUPPORT WORKER’S PROTOCOL AND HOW IT WAS DEVELOPED

Supervision in the Health and Social Care is when a line manager (e.g., team leader and registered manager) has a dyadic communication with a member of staff. These structured meetings can be of a generic or specific nature addressing matters around workload (e.g., working hours, care plans, risk assessments, and behavioural incidents), work well-being (e.g., anxiety and pressure), shared information flow (e.g., updates on new policies and communication around contracts), or set key performance indicators (e.g., completing training, updating support plans, and no missing signatures on the Medication Administration Record (MAR) sheet). Supervision is mandatory for regulated providers as set out by the Health and Social Care Act 2008 and for support workers that comprise a combination of management and clinical supervision.

This current protocol is developed as part of ongoing research on social health and particularly support workers (Kasdovasilis et al., Citation2023; Kasdovasilis, Cook, Montasem, et al., Citation2022). Initially, we conducted a meta-ethnography review of qualitative studies that explored the support worker’s experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kasdovasilis, Cook, Montasem, et al., Citation2022). This involved the critical appraisal and synthesis of the available literature on this topic, allowing us to produce a higher-order interpretation, an overarching view that goes beyond the content of each individual study while ensuring thoroughness and rigour (Fernández-Basanta et al., Citation2021; Sattar et al., Citation2021; Snyder, Citation2019).

From the meta-ethnography, we identified eight key themes from four synthesized studies in the UK and the USA. The eight themes identified were as follows: (1) job role; (2) marginalised profession; (3) impact of work; (4) concerns surrounding PPE; (5) transportation challenges; (6) level of support and guidance; (7) a higher calling and self-sacrifice; and (8) adaptation strategies (Kasdovasilis, Cook, Montasem, et al., Citation2022).

Our second piece of evidence is related to a complete qualitative study exploring the lived experiences of support workers during the COVID-19 pandemic (Kasdovasilis et al., Citation2023). We conducted semi-structured interviews using an interpretative phenomenology (IP) framework. The use of a qualitative methodology allowed us to explore experiences and contexts that, according to Khankeh et al. (Citation2015), fit well in the in-depth exploration of human experiences.

The interview questions were formulated from themes identified from the meta-ethnography (Kasdovasilis, Cook, Montasem, et al., Citation2022) and previous studies of the same nature, such as White et al. (Citation2021), Chung et al. (Citation2005), Raven et al. (Citation2018), Ivbijaro et al. (Citation2020), and Moradi et al. (Citation2020). These were used as the basis for questions, with adjustments being made to fit the context of the qualitative study.

Fifteen (15) support workers were interviewed, while all COVID-19 restrictions from the government were still in place. We identified five main themes: (1) challenging experiences; (2) coping mechanisms; (3) emotions and behaviours arising from the COVID-19 pandemic; (4) external interest on support worker’s health; (5) take-home message from the COVID-19 pandemic (Kasdovasilis et al., Citation2023).

This pandemic support worker’s protocol aims at complementing and improving the normal supervisory meetings by supporting management teams to explore the core areas identified as having an impact on the support worker’s life during a pandemic.

By using our clinical expertise within the Health and Social Sector and the previously mentioned studies, we were able to turn part of the identified themes into a protocol that follows the structure of a normal supervision model, however tailoring the conversational topics towards a simple yet meaningful conversational topic to explore the on-point issue experienced during a pandemic. The protocol can be utilised in line with the per se organisational policies and procedures.

Based on the findings in the meta-ethnographic and qualitative studies, we identified a gap in knowledge with regard to support workers' protocols during pandemic times. As a result, we suggest a new supervisory protocol that can be deployed during pandemic periods (see Appendix A).

THE HOW TO

This guidance is intended for team leaders, managers, registered managers, operational managers, and quality team members working within the Health and Social Care, and it is aimed at supporting them to provide an in-depth supervisory protocol during a pandemic. The supervisory protocol is targeted at UK health-care support workers working in the context of a pandemic. Healthcare support workers offer direct services to users. They may offer services such as personal care, emotional and social support, domestic support, respite care, and they collaborate with professionals and other carers. Notably, their role is different from that of clinical healthcare professionals (e.g., nurses and doctors) since support workers work directly with service users Herber and Johnston (Citation2013) and Rossiter and Godderis (Citation2020). They do this even at patients’ homes and are responsible for the service user’s day-to-day tasks, working in shifts and moving from one home to another Chen et al. (Citation2021). Additionally, unlike doctors and nurses, they do not work in structured environments (Herber & Johnston, Citation2013). Being in unstructured environments and working on the frontline, support workers are more likely to experience the full effects of a pandemic. Lastly, support workers, for the purpose of this protocol, can be distinguished from healthcare professionals (including trainees and interns) on the basis of qualifications and job description. Support staff, extending on the discussion by Herber and Johnston (Citation2013), only need (1) a basic training, (2) to have a clean background check, and (3) to have satisfactory references. This is in contrast to health-care professionals, particularly doctors and nurses, who hold relatively higher qualifications recognized and approved by a professional body (e.g., General Medical Council, American Medical Association Nursing, and Midwifery Council) in comparison to support workers who do not have a registered body.

This guidance complements the existing supervisory protocols that exist within the respective organisations and is not intended to be used as a standalone document.

What Questions Do We Ask?

The questions asked will focus on the main experiences identified during the pandemic, specifically:

Explore how they feel within the current situation

Challenges within the professional and the personal domain

Coping styles the staff member is using (old and new)

What the organisation can do to support them through this journey of change

Initially, the question that should be asked and that will open the conversation is:

“How are you feeling?”

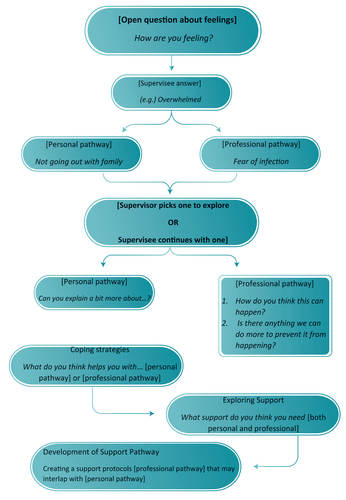

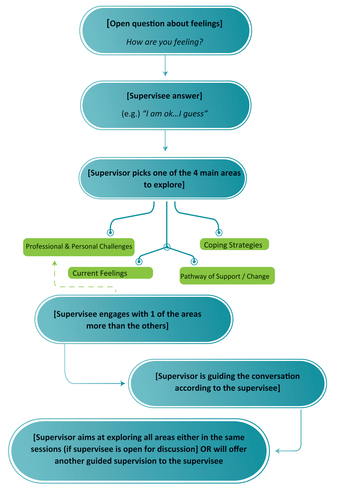

Once the supervisee starts describing his/her experiences, the supervisor can then start formulating the pathway of the conversation.

Example:

“How are you feeling?”

“I don’t know really…I guess, I am overwhelmed…”

“What is it that overwhelms you?”

“This is hard…I can’t go outside with my family, and I am only coming to work and I am afraid in case I get infected.”

In this example, the response allows the supervisor to explore different topics:

The family dynamics and the fact that they can’t go out.

The fact that the supervisee is going outside only for work.

The supervisee is afraid of getting infected.

How Do We Formulate the Questions for a Pandemic? (With Example)

Not all managers or supervisors inherently know how to perform a supervision. Even though there is clear research evidence on how to perform a supervision, organisations normally have their own Human Resources (HR) related policies on how to conduct one.

The supervision policy is normally developed by an HR professional, however within the Health and Social Care, limited psychological education can lead to a “dry” supervision model/template that lacks the necessary depth and instead focuses only on compliance (e.g., conducting a supervision is a legal requirement). Additionally, the regulatory body (CQC) under Regulation 18: Staffing under section (2)(a) quotes that staff should:

receive such appropriate support, training, professional development, supervision and appraisal as is necessary to enable them to carry out the duties they are employed to perform.

without stating what supervision is, who it is performed, or what is included.

Additionally, no information could be found on the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services in the USA (equivalent body to CQC) apart from general articles linked to supervision (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Citation2023).

Below (see ) we present real examples from our previous study as well as suggest based on previous research (Kasdovasilis et al., Citation2023) and our own expertise working within the Health and Social Care sector what a potential follow-up conversation with supervisees could be.

TABLE 3. Supervisee interviews and proposed approach from supervisor

Within the table, we present the domain:

personal challenges,

professional challenges,

coping mechanisms,

support

followed by a subcategory under the main domain:

isolation,

lack of support staff

followed by what the support workers said.

Additionally, if supervisee is engaging with the process of supervision, we present a diagram (see ) of how supervision flows naturally without any input-prompt from the supervisor by using the template (see Appendix A).

However, we present a guided diagram (see ) for supervisors that require an additional support for supervisees that do not wish to engage with the supervision process.

In the implementation of this new supervisory protocol, it is important to distinguish between supervision and therapy. As discussed by Hiebler‐Ragger et al. (Citation2021), while therapy (e.g., counselling) targets a supervisee via using a qualified practitioner offering a psychological approach, supervision aims at improving and addressing work-related outcomes from a supervisor, team leader, or a manager who is not qualified to deliver therapy.

Therefore, the protocol is meant to help the supervisee (support worker) with their professional and work-related challenges. In addition, while the supervisor might address some personal issues that affect work (e.g, stress), they must always follow best practices and recommend therapy to support workers that need it. The managers’ focus should be to offer assistance within the scope of the organisation’s resources and expertise. The protocol is a medium between management and clinical supervision, making it distinct from psychological therapies and other employee assistance programmes (EAPs). The protocol does not offer generalised advice, such as EAP or therapy, but rather suggests a model that can be used during a pandemic. The topics are specifically tailored for a pandemic and therefore even though the questions are open ended, the aim is to maintain the conversation following the particular themes in contrast to therapy or EAP interventions where the themes are quite open and broad and the individual is able to discuss freely whatever s/he wants.

CONCLUSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first time a support worker’s pandemic protocol is presented in such a way that it offers clarity in relation to what supervision is as well as a step-by-step guide on how to perform it.

This protocol can be used by supervisors without previous supervisory experiences, and it can be used in such a way that it ensures both the quality of supervision and the regulatory requirements.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Pavlos Kasdovasilis

Pavlos Kasdovasilis: After spending approximately 10 years working within the industry (e.g., Charities, Private Hospitals, Mental Health Wards, NHS) Pavlos still works as a consultant within the industry with various hospitals and private healthcare organisations assessing their services and providing input in order to improve the overall quality of services offered to service users or staff members. He is also a Health Psychologist in Training.

Neil Cook

Neil Cook: Neil teaches research methods, critical appraisal and public health across a number of our dental courses as well as supervising Master's dissertations. He has extensive experience a wide range of research projects covering quantitative, qualitative and systematic review methodologies.

Alexander Montasem

Alexander Montasem: is a trained behavioural and health promotion practitioner and Chartered Psychologist (CPsychol) with the British Psychology Society (BPS). He has built over the last fifteen years a strong expertise in medically related topics including psychological health, well-being and behaviour change. He led for over six years as Senior Lecturer and Theme Lead the Social, Behavioural and Population Health theme in the School of Medicine at the University of Central Lancashire. During this time, he also played a strategic role as research lead for two newly established University centres.

REFERENCES

- Baines, D., Charlesworth, S., Turner, D., & O’neill, L. (2014). Lean social care and worker identity: The role of outcomes, supervision and mission. Critical Social Policy, 34(4), 433–453. https://doi.org/10.1177/0261018314538799

- Brown, O., Kangovi, S., Wiggins, N., & Alvarado, C. S. (2020). Supervision strategies and community health worker effectiveness in health care settings. NAM Perspectives, 2020. https://doi.org/10.31478/202003c

- Brunero, S., & Stein-Parbury, J. (2008). The effectiveness of clinical supervision in nursing: An evidenced based literature review. Australian Journal of Advanced Nursing, 25(3), 86–94.

- Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. (2023). Retrieved July 17, 2023, from https://www.cms.gov/

- Chen, K., Lou, V. W., Tan, K. C., Wai, M., & Chan, L. (2021). Burnout and intention to leave among care workers in residential care homes in Hong Kong: Technology acceptance as a moderator. Wiley.

- Chung, B. P. M., Wong, T. K. S., Suen, E. S. B., & Chung, J. W. Y. (2005). SARS: Caring for patients in Hong Kong. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 14(4), 510–517. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2702.2004.01072.x

- Downe, S., Walsh, D., Simpson, L., & Steen, M. (2009). Template for metasynthesis. [email protected]

- Driscoll, J., Stacey, G., Harrison Dening, K., Boyd, C., & Shaw, T. (2019). Enhancing the quality of clinical supervision in nursing practice. Nursing Standard, 34(5), 43–50. https://doi.org/10.7748/ns.2019.e11228

- Fernández-Basanta, S., Lagoa-Millarengo, M., & Movilla-Fernández, M.-J. (2021). Encountering parents who are hesitant or reluctant to vaccinate their children: A meta-ethnography. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(14), 7584. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18147584

- Gardner, M. J., McKinstry, C., & Perrin, B. (2022). Effectiveness of allied health clinical supervision following the implementation of an organisational framework. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 261. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-07636-9

- Gennis, V. M., & Gennis, M. A. (1993). Supervision in the outpatient clinic: Effects on teaching and patient care. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 8(7), 378–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02600077

- Herber, O. R., & Johnston, B. M. (2013). The role of healthcare support workers in providing palliative and end‐of‐life care in the community: A systematic literature review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 21(3), 225–235. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01092.x

- Hiebler‐Ragger, M., Nausner, L., Blaha, A., Grimmer, K., Korlath, S., Mernyi, M., & Unterrainer, H. F. (2021). The supervisory relationship from an attachment perspective: Connections to burnout and sense of coherence in health professionals. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 28(1), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2494

- Ivbijaro, G., Brooks, C., Kolkiewicz, L., Sunkel, C., & Long, A. (2020). Psychological impact and psychosocial consequences of the COVID 19 pandemic Resilience, mental well-being, and the coronavirus pandemic. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62(9), S395–S403. https://doi.org/10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_1031_20

- Kasdovasilis, P., Cook, N., & Montasem, A. (2023). UK healthcare support workers and the COVID-19 pandemic: an explorative analysis of lived experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Home health care services quarterly, 42(1), 14–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2022.2123757

- Kasdovasilis, P., Cook, N., Montasem, A., & Davis, G. (2022, July). Healthcare support workers’ lived experiences and adaptation strategies within the care sector during the COVID-19 pandemic. A meta-ethnography review. Home Health Care Services Quarterly, 27, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621424.2022.2105771

- Khankeh, H., Ranjbar, M., Khorasani-Zavareh, D., Zargham-Boroujeni, A., & Johansson, E. (2015). Challenges in conducting qualitative research in health: A conceptual paper. Iranian Journal of Nursing and Midwifery Research, 20(6), 635–641. https://doi.org/10.4103/1735-9066.170010

- Kilbertus, S., Pardhan, K., Zaheer, J., & Bandiera, G. (2019). Transition to practice: Evaluating the need for formal training in supervision and assessment among senior emergency medicine residents and new to practice emergency physicians. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine, 21(3), 418–426. https://doi.org/10.1017/cem.2019.8

- Koshy, K., Limb, C., Gundogan, B., Whitehurst, K., & Jafree, D. J. (2017). Reflective practice in health care and how to reflect effectively. International Journal of Surgery: Oncology, 2, 20. https://doi.org/10.1097/ij9.0000000000000020

- Lee, S., Denniston, C., Edouard, V., Palermo, C., Pope, K., Sutton, K., Waller, S., Ward, B., & Rees, C. (2019). Supervision training interventions in the health and human services: Realist synthesis protocol. BMJ Open, 9(5), e025777. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2018-025777

- Martin, P., Kumar, S., & Lizarondo, L. (2017). When I say … clinical supervision. Medical Education, 51(9), 890–891. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.13258

- Martin, P., Kumar, S., Tian, E., Argus, G., Kondalsamy-Chennakesavan, S., Lizarondo, L., Gurney, T., & Snowdon, D. (2022). Rebooting effective clinical supervision practices to support healthcare workers through and following the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 34(2), mzac030. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzac030

- Mclaughlin, Á., Casey, B., & Mcmahon, A. (2019). Planning and implementing group supervision: A case study from homeless social care practice. Journal of Social Work Practice, 33(3), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/02650533.2018.1500455

- Milne, D. (2007). An empirical definition of clinical supervision. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 46(4), 437–447. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466507X197415

- Moradi, Y., Mollazadeh, F., Karimi, P., Hosseingholipour, K., & Baghaei, R. (2020). Psychological disturbances of survivors throughout COVID-19 crisis: A qualitative study. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-03009-w

- Natchaba, N. (2020). Evaluating the effectiveness of clinical supervision in the care coordination workforce (paper 455) [ doctoral dissertation, St. John fisher college]. Fisher Digital Publications]. https://fisherpub.sjfc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1464&context=education_etd

- O'Donovan, A., Halford, W. K., & Walters, B. (2011). Towards Best Practice Supervision of Clinical Psychology Trainees. Australian psychologist, 46(2), 101–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00033.x

- Proctor, B. (2010, October 4). Training for the supervision alliance. In J. R. Cutcliffe, K. Hyrkäs & J. Fowler (Eds.), Routledge handbook of clinical supervision (p. 24). Routledge.

- Raven, J., Wurie, H., & Witter, S. (2018). Health workers’ experiences of coping with the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone’s health system: A qualitative study. BMC Health Services Research, 18(1), 251. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-018-3072-3

- Rossiter, K., & Godderis, R. (2020). Essentially invisible: Risk and personal support workers in the time of COVID‐19. Sociology of Health & Illness, 42(8), e25–e31. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.13203

- Sattar, R., Lawton, R., Panagioti, M., & Johnson, J. (2021). Meta-ethnography in healthcare research: A guide to using a meta-ethnographic approach for literature synthesis. BMC Health Services Research, 21(1), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-020-06049-w

- Schultz, K., Singer, A., & Oadansan, I. (2021). Seven tips for clinical supervision in the time of COVID 19. Canadian Medical Education Journal, 12(1), e81–e84. https://doi.org/10.36834/cmej.70203

- Shklarski, L., & Abrams, A. (2021). A contemporary approach to clinical supervision: The supervisee perspective (pp. 1–165).

- Snowdon, D. A., Leggat, S. G., & Taylor, N. F. (2017). Does clinical supervision of healthcare professionals improve effectiveness of care and patient experience? A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2739-5

- Snyder, H. (2019). Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines. Journal of Business Research, 104, 333–339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2019.07.039

- Tomlinson, J. (2015). Using clinical supervision to improve the quality and safety of patient care: A response to Berwick and Francis. BMC Medical Education, 15(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-015-0324-3

- Van Ooijen, E. (2000). Clinical supervision: A practical guide. Churchill Livingstone.

- White, E. M., Wetle, T. F., Reddy, A., & Baier, R. R. (2021). Front-line nursing home staff experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(1), 199–203. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.11.022

- World Health Organisation. (2022). Health workers and administrators. Retrieved August 21, 2022, from https://www.who.int/teams/risk-communication/health-workers-and-administrators

APPENDIX

Appendix A. Enhanced Supervision Protocol

Introduction

This supervision protocol should be used in complement to your organisation original policies and procedures. This protocol is not to be used as a standalone tool but rather as a complementary one. The basis of this protocol is to offer management a guided tool to navigate supervision during the times of a pandemic exploring the four areas of importance that have the most significant impact.

For the supervisor

I understand that:

I will guide the supervisee according to the template and within reason

I will maintain confidentiality according to my organisations policies and procedures

I will offer advice/guidance/pathways of recovery after I make sure the plan of change advised is realistic OR in case I cannot, I will seek appropriate support from management/quality department/experts in order to advise the supervisee accordingly

For the supervisee

I understand that:

These sessions are confidential according to the organisation policies and procedures

The supervisor may seek additional support from management/quality department/experts in order to build a guidance to advise me appropriately

These records may be accessed for audit purposes from internal (e.g., Quality Department) or external parties (e.g., CQC, NHS trust, and local council) depending on the area of work

Signed: [Supervisor] … … … … … … … … Date: … … … … … … … …

Signed: [Supervisee] … … … … … … … … Date: … … … … … … … …

AREAS TO DISCUSS DURING SUPERVISION:

□ Current Feelings □ Professional Challenges □ Personal Challenges

□ Coping Strategies □ Pathway of Support / Change

Current Feelings

Professional Challenges

Personal Challenges

Coping Strategies

Pathway of Support / Change