ABSTRACT

There have been increasing calls within critical disability studies to move beyond ethnocentric Global North/Western interpretive lenses, especially when doing work in countries that have historically been oppressed by such cultures. These lenses rarely embrace the unique cultural nuances and social structures of different communities such that meaningful social justice is not possible. In this paper, we propose that cultural praxis (based on the work of Paulo Freire) could be a necessary paradigmatic shift toward amplifying disability research beyond ethnocentrism and toward culturally reflexive and relevant study. We show how we developed this methodological process through conceptual representations of our evolved thought, author reflections, and theoretical groundings. We invite dialogue from colleagues invested in socially-just research, and hope this approach begins further conversations and methods for doing meaningful, culturally specific work to achieve cultural praxis in physical education and wider realms of critical disability studies.

Introduction

A supposedly global movement, disability studies is rooted within an ethnocentric, Global North, Western perspective (Goodley, Citation2017; Meekosha, Citation2011) which has notable repercussions for doing inclusive work in other countries (Haslett & Smith, Citation2020). Ethnocentrism situates research within a hegemonic lens whereby knowledge and reality are shaped by White, Globally North, Globally Western, Judeo-Christian values (Ryba et al., Citation2013). Such epistemological and ontological underpinnings are not only ineffective but potentially harmful, particularly when used within cultures that have been oppressed and colonized by White, Western, Northern countries (Xu, Citation2002). Utilizing only Global North, Western paradigms to interpret disability and define what disability is negates the rich, historic legacies of culturally embedded languages, beliefs, faiths, values, and norms of countries outside these regions, resulting in underdeveloped, underused, and underappreciated paradigms of disability (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, Citation2009).

To address this, authors such as Ghai (Citation2012), Goodley (Citation2017), Grech (Citation2009), Kim (Citation2017), Meekosha (Citation2011), and Nguyen (Citation2018) contributed lenses and paradigms of Global South and Postcolonial Disability Studies to move understandings of disability “beyond the boundaries of the Gulf Stream” (Meekosha, Citation2004, p. 731). This scholarship provided insight into different values, histories, and beliefs of disability in respective locales such that critical disability studies (CDS) could expand beyond ethonocentric, hegemonic understandings. While Global South and Postcolonial paradigms are welcome additions, these lenses are still too wide to do meaningful, socially-just research in specific countries and contexts. For example, authors exploring disability inclusive physical education (PE) in Japan, Brazil, South Korea, and the United States concluded that to do appropriate and effective inclusive research and practice, the unique values, cultures, histories, languages, and infrastructures of each country must be considered (Haegele et al., Citation2017). Thus, a research approach focusing on more context-specific, culturally sensitive epistemologies and ontologies are required to truly anchor agendas of social justice within inclusive PE and, we dare say, CDS as a whole.

The following is a modest approach to address aforementioned gaps within CDS by conceptualizing culture as a central component for doing culturally sensitive, socially-just research. Such efforts have been advocated in sport and exercise psychology (e.g., Blodgett et al., Citation2015; McGannon & Smith, Citation2015; Ryba & Wright, Citation2005; Ryba et al., Citation2010, Citation2013; Schinke et al., Citation2012) and we were greatly influenced by these authors in our attempt to amplify specific cultures and contexts within CDS. Further, we acknowledge the work of authors who have highlighted the intersections of cultural studies and CDS (e.g., McRae, Citation2018), but we wish to move this work further to show how this may be done by sharing our novel methodological approach. This approach is but one way, not the way, to do more contextual and culturally nuanced inclusive work. We hope this paper triggers further debate and discussion regarding how to expand disability scholarship beyond ethnocentrism.

The objectives of this paper were threefold:

Describe in detail the methodological approach we crafted to address ethnocentrism in CDS;

Share our “critical moments” that shaped our decision making and how these influenced the research process;

Provide critical research-based, applied and theoretical implications for adopting this approach in CDS.

To achieve objectives 1 and 2, we have provided a methodological narrative beginning with our foundations and ending with a conceptualization of our process. Within this narrative, we provide what we have termed “critical moments” that significantly informed the development of our method. These moments contribute to a reflective journey regarding why and how we made decisions to change our initial research direction and ultimately designed an approach that, we believe, embraces cultural specificity. We wish readers to note that, though we present this in chronological fashion for clarity, this process was not at all linear or chronological, but an interactive, long, complex, difficult, frustrating, and messy development.

Methodological foundations

To set the scene for how and why our research approach was crafted, we first present (i) the positionality and cultural voices of the research team, and (ii) origins of the research.

Positionality and cultural voices of the research team

The research team were representative of multiple cultures, disciplines, and stages of research career. This was a boon to the development of the research process. Different cultural and disciplinary lenses, norms, views and experiences of the team provided a space where taken for granted notions regarding language, disability, PE, and theories could be challenged; we explore these throughout the paper. Emma Richardson had the most experience in English-language academic writing, CDS and leading research projects; she therefore took a leading role in the research team. However, she is a UK-based scholar that has worked only within Global North and Western countries. The other research team members are based in Japan and could speak to Emma’s gaps in knowledge as well as provide diverse, thoughtful, and important critiques regarding interpretations of data that were central to the development of a cultural praxis approach to CDS. We approached this research as an opportunity to support scholars, teachers, and students of inclusive PE in Japan in their knowledge and practice.

Our respective cultural and research backgrounds were essential for developing this approach. We could not (and would not) share our approach without giving due diligence to who we are and what we brought to the research process. We have therefore provided individual reflective statements in the Supplemental Materials stating how we influenced the research process. In summary, the team were representative of 2 Japanese born researchers (Shinichi and Shigeharu), 1 American researcher (Cindy) that has Japanese heritage who lives and studies in Japan, and a Scottish researcher (Emma) based in the UK. Of note, 3 researchers had studied postgraduate degrees in the United States, and 2 members of the team had experience living in the UK; thus, all had experienced different cultures. At the time of development, 2 researchers were in lecturing or full-time research roles and 2 were PhD students. All members were specializing, in some way, within inclusive disability and physical activity. We, as a group, seek to serve disabled communities and work toward facilitating more socially-just physical activity.

Origins of research

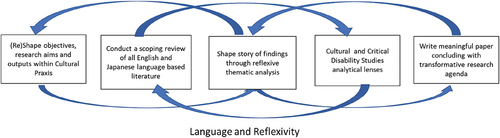

The University of Worcester and University of Tsukuba are collaborative international partners. Both institutes’ learning, teaching and research priorities are directed toward inclusive and equitable PE through applied research and sharing best practice. This particular research began as an endeavor to establish a research agenda that would focus on creating more (i) confident inclusive PE teachers in Japan, and (ii) inclusive PE content and curriculums in Japan. To do this, we needed to understand the current knowledge base of inclusive PE in this country. What has already been published? What policy and curriculum documents shape practice? We therefore designed a research study that would involve a scoping review of all English and Japanese language publications related to disability and Japanese PE. A conceptual representation of our initial design is presented in . The objectives of this research were to (1) establish the current knowledge base of inclusive PE in Japan, (2) identity gaps in teaching and learning practice, and (3) propose a longitudinal research agenda to address these gaps.

Developing a cultural praxis approach

In the following section we present how we developed our approach. We share our key decisive moments that built our research process from (i) a foundational scoping review, to include (ii) pluralistic analysis, (iii) a cultural praxis paradigm, (iv) reflexivity, (v) rigor, and (vi) nuances of language.

Foundational scoping review

The first step of our process was to conduct a scoping review. Scoping reviews lack a unified definition but are typically used to (i) map key concepts underpinning a research area (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005), (ii) synthesize and analyze a range of informational material (research and non-research based) to gain greater conceptual clarity, and (iii) use wide-ranging, heterogeneous sources rather than purely “best practice” evidence to better capture wider policy and application. The development of inclusive PE in Japan is still in its infancy (relative to other countries) with a cultural shift to integrated schools occurring 15 years ago. There are a limited number of publications exploring this phenomenon, and to craft a future research agenda it was necessary to include all information and knowledge currently available to scholars and practitioners. We followed the framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and improved upon by Levac et al. (Citation2010) that outlines steps to (i) identify the research question, (ii) identify relevant studies, (iii) select studies, (iv) chart the data, and (v) collate, summarize, and report the results.

Scoping review stage 1: Identify the research question

The first stage of a scoping review requires consideration of the question that will provide a shape and roadmap for subsequent stages (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). The question should be broad, but clearly articulate the target population and contextual scope to ensure an effective search strategy (Levac et al., Citation2010). To identify our research question, we reflected on our study purpose, and envisioned our desired outcome of an in-depth and appropriate research agenda. Our question was “What is the current landscape of inclusive PE in Japan?”

Scoping review stage 2: Identify relevant studies

The second stage involved developing a plan for where to search, which search terms to use, time span, team roles, and inclusion criteria (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). Levac et al. (Citation2010) further advised that the research question should inform decision making around the study’s scope, and that a team of “experts” regarding content and method be assembled (Levac et al., Citation2010). Our multicultural team from the UK and Japan specialized in inclusive PE in Japan, qualitative analytical methods, and CDS. Researchers that spoke English as a first language (Emma, Cindy) conducted a scoping review of relevant studies written in English, and researchers that spoke Japanese as a first language (Shinichi, Shigeharu) did the same for studies written in Japanese. The addition of Japanese language publications added knowledge beyond previous reviews in this area as these focused only on English language papers (e.g., Qi & Ha, Citation2012). We decided on an inclusion criteria where publications must (i) be written in English or Japanese, (ii) be published in 2007 or later reflecting the time when disabled and non-disabled children began being educated together – thereby reflecting contemporary education structure, (iii) focus on PE, and (iv) focus on disability. We did not exclude any population or impairment type. We used Google Scholar, ERIC, DOAJ, CiNii, J-Stage, Pubmed, Scopus and Science Direct as our first search engines. Other research techniques included specific journal searches such as the “International Journal of Disability, Development and Education” and the “Japanese Journal of Adapted Sport Science,” government documents, conference presentations, book chapters, and reference lists. Search terms were (initially) ‘Japan*ese; physical education; adapted physical education; disabil*ity*ities; adapted; inclusi*ve*ion; impair*ment*ed*s.

Scoping review stage 3: Study selection

The third stage required searching for and evaluating whether an article should be included (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). This is an iterative process involving refining the search strategy, reflecting on inclusion criteria, and continually searching for literature (Levac et al., Citation2010). Searching for literature lasted approximately 1 month. In total, the English-language search generated 10 studies and the Japanese-language search generated 14 documents (Table S1).

Scoping review stage 4: Charting the data

This stage required extracting data from the studies and organizing this into chart form (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005). To do this stage rigorously, the team collectively developed the chart and decided what information should be gleaned from the studies to answer the research question (Levac et al., Citation2010). We agreed upon a data chart that included the title of the article, authors, journal name, the study location, study design, population under exploration, type of impairment, school level, any intervention, outcome/findings and conclusions. Stage 5 required authors to collate, summarize and report results, but before this stage our first critical moment changed the direction of our research.

Pluralistic analysis through cultural studies and CDS lenses

As we reflected, publications identified in our scoping review had not considered the cultural nuances of Japanese education, disability, and social norms as a whole, thus we could not simply report findings as outlined by scoping review guidance. Instead, to ensure our goal of creating a research agenda that fit within Japanese cultural norms, educational structure, and teachers’ practice, and was therefore more meaningful to scholars and practitioners, we adopted pluralistic analytical lenses of cultural studies and CDS. This helped us contextualize and critique our findings within the boundaries of Japanese education and values, while still embracing an empowering and transformative lens toward disability. Pluralistic data analysis involves the application of two or more techniques, thereby affording the opportunity to create a more complex, nuanced, and multi-layered interpretive process that embraces complicated research contexts (Clarke et al., Citation2015). The adoption of pluralistic lenses also encourages theoretical eclecticism, which allowed us to analyze data beyond the ethnocentric theories that had been previously used. Further, this approach encourages researchers to consider implications from different perspectives (e.g., teachers, students, policy makers) and provide recommendations that could be useful for more than one party. Readers can then choose the implications or findings most relevant to their practice to guide action. This synthesizing of experiential and theoretical knowledge can help generate new ways of understanding reality that transforms inquiry from theory to praxis (Schinke et al., Citation2012). This is turn provided an opportunity for us as a research team to produce not just something that was intellectually interesting, but something that could be significantly transformative (Freire, Citation1970, 2007) for inclusive PE in Japan as a whole.

Cultural studies

Cultural studies explores how a society shapes the meaning and lived experiences of a phenomena (such as disability) through politics, power relations, history, values, norms, ways of doing and being, and symbols (Waldschmidt, Citation2017). Disability is lived and structured through culture and, vice versa, disability also restructures culture and understandings (Waldschmidt, Citation2017). Culture is therefore central to shaping disability and the lived experiences of individuals that identify as part of that community (Riddell & Watson, Citation2007). However, though a “cultural turn” in disability studies has been advocated (Garland-Thomson, Citation2002), a key argument made by numerous authors (e.g., McRae, Citation2018; Meekosha, Citation2004, Citation2011; Nguyen, Citation2018; Waldschmidt, Citation2017) is that this cultural element is too narrowly applied, or viewed merely as a periphery to the disabled experience rather than a central piece; some key arguments to this point were presented earlier in this paper. Cultural studies therefore provided an essential lens to critique how Japanese values, norms, and language of disability and education shaped teachers’ perceptions and experiences of inclusive PE. This led us to further analytical theories we could more meaningful utilize such as Eastern Philosophical ideas, the theory of conformity, and Confucianism.

CDS

CDS is a space where we can craft political, theoretical, and practical advancements for progressive social change (Goodley, Citation2017). We do this by disrupting commonly accepted norms, perceptions, inequalities, inequities, and oppressions of disabled people and communities by centering disability in local, national, and transnational contexts (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, Citation2009). We further consider disability as complex, culturally and socially relative, intersecting with other identities, and requiring social, psychological, cultural, and critical theories to try and understand (Goodley, Citation2017). Authors can extend CDS to a more geopolitical, socio-culturally appropriate context that respects unique cultures to create new, transformative agendas for social justice (Goodley, Citation2017). It is apparent there are numerous intersections regarding cultural studies and CDS, particularly with commitments to reflection, complexity, social constructionism, and transformative, emancipatory research (McRae, Citation2018). Forging links between these lenses may therefore open a door to more culturally specific, sensitive appreciations of disability, and direct us toward adopting a more culturally specific research paradigm.

Utilizing a cultural praxis approach

From Paulo Freire’s seminal work “Pedagogy of the Oppressed” (1970, 2007), praxis refers to a dynamic, dialogical, and cyclical process of critical “reflection and action upon the world in order to transform it” (p. 36). In other words, we reflect on current social injustices and suggest transformative action based on those critical reflections. This approach requires researchers to critique instances such as (dis)ableism, intersectionality, oppressed identities, and socio-culturally shaped marginalization and transform these into empowering, reflective, critical, co-produced knowledge. More than merely producing knowledge, however, cultural praxis calls researchers to challenge identified inequities by striving for social justice and advancing an agenda of positive change – something which strongly aligned to our desire to create a transformative research agenda. Ensuring engagement in cultural praxis throughout our process, and underpinning this transformative research agenda, were a cultural praxis paradigm, ontological relativism, and epistemological constructionism.

A cultural praxis paradigm

The underlying paradigm of this work became cultural praxis. Put simply, this worldview holds that there are injustices, inequalities, power differences, hegemony, and oppression of individuals that are deemed “other,” and that these oppressions are socio-culturally constructed, and reinforced through interactions with others and wider society (Freire, Citation1970, 2007). Cultural praxis allows researchers to undertake an active, reflective role by blending theory, culture, and social action together to challenge hegemonic ways of being and broaden the epistemic spectrum of a particular field (Ryba et al., Citation2010). The ultimate objective is to craft an agenda of positive change and social justice by highlighting oppressive socio-cultural issues within everyday life and broaden appreciation of difference to include alternate cultural identities, sites of belonging, and competing notions of “normalcy” (Ryba & Wright, Citation2010).

Ontological relativism

Ontological relativism holds that reality is multiple, fluid and ever changing, and rejects that culture or disability is something static or singular (Cluley et al., Citation2020). Instead, our perception of reality or “truth” is shaped by intersecting and overlapping discourses surrounding gender, sexuality, nationality, physicality, disability, and race, and which local, social, and cultural groups one has membership to (Ryba & Wright, Citation2010). We embrace the multiplicity and fluidity of identity and value different world “truths,” understanding such “truths” to be products of socio-cultural narratives and discourses (Blodgett et al., Citation2015). This relativist stance also situates “truths” and ways of being as things that can be challenged toward more inclusive and empowering realities. Relativism aligns to Freire’s (Citation1998b) own ontological argument regarding praxis; “human nature is expressed through intentional, reflective, meaningful activity situated within dynamic, historical, and cultural contexts that shape and set limits on that activity” (cited in Glass, Citation2001, p. 16). As such, this underpinning gave us support and direction through our research endeavor.

Epistemological constructionism

Epistemological constructionism holds that knowledge is subjective and socially, culturally situated (Krane, Citation2001). Further, this understanding of knowledge considers that researchers and the practice of research produces rather than reveals evidence (Willig, Citation2019). In other words, what we “know” about a phenomenon (e.g., inclusive PE in Japan) is constrained within the limits of its context and the beliefs of both the researchers and the participants involved in the research. In our practice, we considered that knowledge produced about inclusive PE in Japan was bounded by the cultural, structural realities of this country and context. In this way, knowledge of a phenomenon is itself a cultural artifact (Ryba et al., Citation2013), offering us meaning and opportunities to resist ethnocentric knowledge that oppresses colonized or unrepresented cultures and moves toward more empowering ways of knowing. This understanding of knowledge aligned to a cultural praxis paradigm, as Freire (Citation1998a) highlighted when people can reflect upon oppression within their culture and how it is crafted, they have the power to change it. Moreso, through rigorous reflection of how and why reality “is,” this can embolden a critical consciousness within a person or group to challenge what reality “can be” (Freire & Faundez, Citation1992); considering knowledge as something malleable and flexible provides space and opportunity for praxis-based transformation to occur. The adoption of cultural praxis as our paradigmatic underpinning again evolved our research design and gave us guidance to ensure we embraced cultural and contextual specificity.

Embracing reflexivity

We wanted to ensure transparency and celebrate reflexivity in our work and did so by (1) critically reflecting on our own backgrounds, and (2) utilizing reflexive thematic analysis (RTA) to support reflexivity throughout analysis.

Critical self-reflection using pluralism and cultural praxis

To achieve cultural praxis (and do culturally sensitive research), researchers must critically reflect on their own values, biases, cultural background and immersions, and self-identities to establish how these may impact and influence the research process, and interpretations of data (Schinke et al., Citation2012). We presented this earlier in the paper, however the addition of pluralism and cultural praxis helped ground our reflexivity not just at the beginning of our work but throughout the entire process. Pluralism and cultural praxis ask researchers to question different methods, theories, and purposes of doing research to recognize why they have used particular tools, how they influenced findings (North, Citation2013) and, in turn, this can problematize the ethnocentric focus of CDS. That is, by reflecting on one’s positionality while adopting a cultural praxis lens, researchers can sufficiently shift their own perspective to embrace different and multiple ways of knowing which expands their knowledge from known to unknown – such as drawing upon theories from Eastern Philosophy, Confucianism etc. Pluralism complements cultural praxis by drawing upon theories and lenses that “fit” within the context culture, or belief system of the community being explored thereby embracing diversity, authenticity and analytical dialogue required to do culturally respectful work. Thus, we chose to adopt an analytical framework that was rigorous and would help guide our multicultural, geographically distant team, while also embracing the importance of researchers as tools in the research process; reflexive thematic analysis (RTA).

Adopting RTA

RTA is achieved with researchers at the heart of the analytic process (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019) as researcher subjectivity is a resource for knowledge rather than something that must be contained (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a). The aim is to conceptualize shared meaning patterns across a data set with an organizing concept (e.g., cultural praxis) (Braun et al., Citation2016). We chose this approach as it “fitted” the purpose of our research, our philosophical assumptions, complemented other research methods (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021b; Willig, Citation2019) and allowed us to do reflexive, analytical work ascertaining the current state of inclusive PE in Japan. Further, the flexibility of this approach meant we could embrace different framings of language rather than be constrained by one definition (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a) (such as differences between Japanese and English language conceptions of disability). We used a deductive, semantic approach to our analysis. Deductively, we used existing research (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021a) generated from the scoping review as our data. We adopted a semantic lens to establish more surface level understandings of themes to capture the data, this then provided the focus for us to apply our pluralistic analytical lenses of cultural studies and CDS. We did this analysis by following the iterative and recursive 6 stage guide recommended by Braun et al. (Citation2016) and Braun and Clarke (Citation2021a).

Steps 1 to 4 (immersion, coding, theme generation, reviewing themes) were done iteratively with the team divided into two; those who spoke Japanese as a first language analyzed the Japanese papers and those who spoke English as a first language analyzed the English language papers. Coding and theming were applied to the results and discussion sections of the selected papers. Individually, we coded and themed those papers then met fortnightly via ZoomTM to discuss and reflect on our progress. When we had each created a thematic map, we combined these to create an overall story that encompassed the current

knowledge of inclusive PE in Japan and completed (our first!) naming of themes. These names changed repeatedly as we wrote, read, and reflected on our analysis as writing too is analysis (Richardson, Citation2000).

Ensuring rigor

To help guide us and ensure we maintained a high level of scholarship, we (i) adopted a methodological framework that complimented our pluralistic approach, and (ii) set relativistic rigor parameters that helped us ensure we maintained the highest standards of scholarship possible.

Ganzen’s methodological framework

The research framework we chose to help structure our complex methodology was Ganzen’s (Citation1984) systems approach. This is a methodological framework to investigate a complicated phenomenon considered to have different elements, structures, influences, and perspectives (Ganzen, Citation1984). This approach has previously been used to explore cultural praxis in sport and exercise psychology (e.g., Ryba et al., Citation2013), and we believed was an appropriate framework for our research purposes. This approach is divided into 3 steps; (i) rough synthesis providing a holistic, detailed, overview and surface level description about a particular phenomenon, (ii) analysis focusing on the patterns, complexity, diversity, influential factors, and nuances outlining why a phenomenon is perceived a certain way, and (iii) synthesis of a higher level whereby new knowledge is crafted that provide more variations, nuances, and different ways of meaning and being than previously supposed. The steps of Ganzen’s model aligned to our pluralistic methods; a scoping review as a rough synthesis, RTA to establish patterns and complexity, and further analysis shaped by cultural and CDS lenses to add a higher level of synthesis. This framework helped structure our approach and manage multiple analytical elements.

A relativist approach to rigor

A relativist approach to rigor embraces the different purposes, methods, analysis, and assumptions that underpin research to apply criteria that are appropriate for that research context (Sparkes & Smith, Citation2009). Researchers suggest characteristics by which they believe their research should be judged (Smith & McGannon, Citation2018). In this way, researchers can reflect on the nuances of their work, its integrity, and alignment with research purpose and methods. We strove for substantive contribution, coherence, and transparency. Substantive contribution relates to the impact that work may have accorded to understandings of a phenomenon, and how new knowledge contributes to a social science perspective (Richardson, Citation2000). By situating our work within a cultural praxis paradigm and the various intricate and interconnected ways we used different analytical techniques, we hope to have substantially contributed knowledge surrounding one potential way of doing disability research that is culturally and contextually specific, as well as working toward social justice in inclusive PE in Japan. Coherence in research seeks to present a complete and meaningful picture of how the work was conducted, and how it fits within wider research and practice (Lieblich et al., Citation1998). We sought to achieve this through our detailed paper outlining how we conducted our research, showing evidence of our process and providing reflective insights regarding how and why our process changed. Finally, we sought transparency by holding each member of the team to account, keeping detailed notes of meetings, ensuring each stage of analysis was conducted with integrity, documenting and sharing analyzes progress in a shared team folder and presenting our findings to two critical friends (Prof. Yukinori Sawae and Lerverne Barber) as theoretical sounding boards (Tracy, Citation2010). We hope these standards of quality are apparent throughout this paper and in our empirical paper (under review) where we present our findings.

Respecting language and nuances

To respect the important differences of language, we adapted our research design in the following ways. First, during searching for articles in the scoping review stage, the Japanese team noted that cultural reflexivity was required to amend some more Western search terms to Japanese discourse to find as many relevant studies as possible. Second, we openly stated our biases and backgrounds as researchers as well as the disability language we each use in the Supplemental Materials of this paper. Third, in our empirical paper, we did not change or translate any Japanese phrases or words. Finally, (also linking to cultural praxis underpinnings) we actively sought more holistic and/or culturally relevant theories and concepts to interpret results. Our final research design is shown in .

Concluding thoughts and contributions

To our knowledge, this is the first attempt to address ethnocentrism in CDS by providing a method to do more culturally sensitive and contextually specific, respectful disability scholarship. Further, we hope the rich detail we provided outlining why and how our research process and design evolved offer some transparency of the research project as well as clarity of how such an approach may be employed in other work. Indeed, Thambinathan and Kinsella (Citation2021) stated work seeking transformative praxis needs to show how this may be done rather than merely telling. By sharing the evolution of our process through our various “critical moments” we showed how our approach may be a useful method to do culturally sensitive, socially-just work within CDS, and in particular in the context of inclusive PE. We emphasize this is one way of engaging in cultural praxis-based work, we do not believe this is the only way. To achieve our last objective, we share some final reflections and implications of using this method going forward.

How ethnocentric is this method?

It did not elude us that the methodology we chose to do our cultural praxis approach may in itself be a Western, colonized way of doing things. Reflecting upon the methodological choices, as Emma led the research endeavor and was more embedded within CDS and qualitative inquiry than the rest of the team, her suggestions and background may indeed have led us to fall into the ethnocentric trap we so desperately wished to avoid. Throughout the development of this method, we did reflect on and discuss tension that scoping reviews, RTA, and analytical lenses of CDS and cultural studies were, and are, mainly used within the ethnocentric areas we highlighted. Through intense self and methodological reflection, we decided to still use these methods for the following reasons. First, the flexibility of RTA as a method and its embracing of author reflexivity does lend to a more cultural praxis-based research approach as authors (the majority in this case identifying as Japanese or being exposed to Japanese culture) can include their own cultural background and interpretations within the reflexive process and subsequent findings. We cannot be free from individual perspective (which though unstated is exhibited through ethnocentric underpinnings in previous literature), but in this paper we are trying to be honest about, and reflexive of, our biases and the RTA gave us a collective framework to do this. Rather than limiting or shaping interpretations to an ethnocentric belief system, RTA instead provided a platform for us to critically reflect on our cultural influences, lived experiences, and the area under investigation. Thus, our Japanese colleagues could embrace their Japanese heritage and apply Japanese cultural lenses onto a Japanese context. Further, we strove to explore more culturally specific interpretations using our analytical lenses such as being informed by collectivism, Confucianism, and more holistic disability theories that can be shaped and applied to different contexts. We also embraced cultural norms and roles of teachers and students in general, and how disability has been interpreted throughout Japan’s history, particularly after their own industrial boom of the 1950s. Thus, while we wrestled with using methods developed in a Globally North, Western countries, the flexibility of these methods allowed us to embrace the cultural-sensitivity and reflexivity required to engage in cultural praxis. We do however note that cultural praxis and cultural-sensitivity may be advanced utilizing methodological approaches, frameworks and underpinnings that are specific to the culture being explored, and strongly support decolonizing research methods (Thambinathan & Kinsella, Citation2021) as a way forward in CDS.

Theoretical, research(er) and applied implications

The addition of a cultural praxis approach adds theoretical significance to the field of CDS by contributing a new research approach that seeks to amplify disability experience within specific contexts and cultures. Our approach provides a more specific, flexible, and contextually nuanced addition to other lenses of disability that seek to challenge ethnocentric and hegemonic ways of being and knowing (e.g., Goodley, Citation2017; Meekosha, Citation2011; Nguyen, Citation2018). By situating this lens within a cultural praxis agenda, we also showed how a review or exploration of disability experience may be motivated by more than curiosity or knowledge finding, but transformative action toward social justice. In this way, theory to practice gaps may be bridged as an adoption of praxis in CDS can move scholars and practitioners closer to collaboration and partnerships (Schinke et al., Citation2012). By using the same social justice agenda as a roadmap, and focusing on different points of that agenda, scholars and practitioners can work toward inclusion and positive change in meaningful ways within their respective disciplines. Further, by adopting an approach embedded within other disciplines (cultural praxis originating within education), there are opportunities for inter, cross and multidisciplinary collaborations urgently needed within CDS (Ellis et al., Citation2019). Bringing together partners from education, sport, geography, policy, culture etc., under a transformative lens for social action can create a powerful network of skills, expertise and influence that progresses social justice efforts forward and more meaningfully than single disciplines alone (Watson & Vehman, Citation2020). Linked to this, bringing together research partners from different cultures also has significant implications for research, and researchers as essential tools of research, particularly in CDS (McRae, Citation2018).

From our experience, we highly encourage other researchers to create teams with different cultural backgrounds. We found this to be not only enlightening for the research process, but a thoroughly enjoyable, rewarding, and meaningful experience as people. The multicultural background of the team allowed taken-for-granted Japanese terms, policies, values etc., to be questioned by the non-Japanese members, and vice versa Japanese members could challenge potentially ethnocentric, hegemonic values and ideas proposed by the members from the Global North/West. We reflect that the depth, rigor, and complexity of our work would not have been possible without a research team that could supportively challenge each other’s assumptions, interpretations, worldviews, and frameworks in a way that embodied cultural praxis as not only a method but a way of being. Going forward, the adoption of a multicultural team has implications for CDS and the need for further methods and lenses to do culturally and contextually nuanced work. As noted in this paper, the method presented is not the way, but a way of doing CDS in a more culturally specific way. By adopting cultural praxis (or other lens that embraces cultural respect), researchers can propose and show methods, theories, measures of rigor, interpretations and agendas for praxis that are embedded in their backgrounds, languages, faiths, social norms, cultures and social structures. This will expand knowledge of disability to a more global scale than dominant Northern or Western lenses, and also amplify ways of knowing and doing research beyond traditional colonized methods (such that we have adopted in our approach). Indeed, “decolonizing” research methods is thankfully a growing discipline (e.g., Hollinsworth, Citation2013), but we would go further that researchers may also need to be “decolonized.” By this we mean educated and informed of methods, rigors, techniques, theories, frameworks, concepts etc., outside their own cultural views that fit the contexts and cultures they are working within. Further, researchers can be “decolonized” by reflecting upon their own biases regarding how and why they have made certain theoretical and methodological choices. In this way, we are not advocating for Global North or Western disability researchers to stop what they are doing, but to “stop” and consider their place in the world, in CDS, in the research, and wider agendas of social justice. Indeed, those striving to do research aligning with cultural praxis must ensure their work is “socially constituted, intricate and nuanced analysis of culture, self-identity and personal experience of the researcher and participants” (McGannon & Smith, Citation2015, p. 80); this requires complexity.

While the bringing together of so many methodologies were complicated, difficult, and required a lot of reflexivity to manage, we encourage others to embrace complexity in their work. Methodological variation is strongly encouraged in CDS and cultural praxis, as well as critical reflections of which methodology best aligns with underlying assumptions and the purpose of the research (Ryba & Schinke, Citation2009). The evolution from our initial research design to our final design shows why this is necessary. Our adoption of pluralism allowed us to capture a multi-layered understanding of inclusive PE in Japan by choosing different underpinnings, methods, and interpretive lenses to achieve our goal of a transformative social justice agenda. Our findings (under review) would have been inherently different, probably ethnocentric, lacking criticality, and without transformative action had we not adopted multiple, intricate, iterative, and complex approaches. This brings us back, again, to the importance of reflection, changing design, exploring new and emerging theories, methods, and lenses, analyzing the ontological and epistemological congruence of different methods together, and crafting a meaningful ending that serves disabled communities, scholars and practitioners through praxis.

We of course recognize the limitations to our approach – especially potentially ethnocentric methods and colonized standards of rigor – but we hope this paper is a starting point for better, creative, innovative and meaningful approaches to CDS. We encourage others to engage in cultural praxis as a paradigm for doing culturally sensitive, transformative work and share their own approaches, reflections and “critical moments” to expand discussion and knowledge that will help the movement toward socially just CDS as a whole.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (23.9 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2023.2188600

References

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Blodgett, A. T., Schinke, R. J., McGannon, K. R., & Fisher, L. A. (2015). Cultural sport psychology research: Conceptions, evolutions, and forecasts. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 8(1), 24–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2014.942345

- Botha, M., Hanlon, J., & Williams, G. L. (2021). Does language matter? Identity-first versus person-first language use in autism research: A response to vivanti. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-020-04858-w

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021a). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. Sage.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021b). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 18(3), 328–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun, V., Clarke, V., & Weate, P. (2016). Using thematic analysis in sport and exercise research. In B. Smith & A. Sparkes (Eds.), Routledge handbook of qualitative research in sport and exercise (pp. 213–227). Routledge.

- Clarke, N. J., Willis, M. E. H., Barnes, J. S., Caddick, N., Cromby, J., McDermott, H., & Wiltshire, G. (2015). Analytical pluralism in qualitative research: A meta-study. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 182–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.948980

- Cluley, V., Fyson, R., & Pilnick, A. (2020). Theorising disability: A practical and representative ontology of learning disability. Disability & Society, 35(2), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2019.1632692

- Ellis, K., Garland-Thompson, R., Kent, M., & Robertson, R. (2019). Interdisciplinary approaches to disability. Looking towards the future (Vol. 2). Routledge.

- Freire, P. (1970, 2007). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Modern Classics.

- Freire, P. (1998a). The adult literacy process as cultural action for freedom. Harvard Educational Review, 68(4), 480–498. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.68.4.656ku4.7213445042

- Freire, P. (1998b). Cultural action and conscientization. Harvard Educational Review, 68(4), 499–521. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.68.4.656ku47213445042

- Freire, P., & Faundez, A. (1992). Learning to question. Continuum.

- Ganzen, V. A. (1984). Сиcтемные описания в психологии [System’s descriptions in psychology]. Leningrad University Press.

- Garland-Thomson, R. (2002). Integrating disability, transforming feminist theory. NWSA Journal, 14(3), 1–32. https://doi.org/10.2979/NWS.2002.14.3.1

- Ghai, A. (2012). Engaging with disability with postcolonial theory. In D. Goodley, B. Hughes, & L. Davis (Eds.), Disability and social theory (pp. 270–286). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Glass, R. D. (2001). On Paulo Freire’s philosophy of praxis and the foundations of liberation education. Educational Researcher, 30(2), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X030002015

- Goodley, D. (2017). Dis/Entangling critical disability studies. In A. Waldschmidt, H. Berressem, & M. Ingwersen (Eds.), Culture–theory–disability: Encounters between cultural studies and disability studies (pp. 81–97). Tanscript-Verlag.

- Grech, S. (2009). Disability, poverty and development: Critical reflections on the majority world debate. Disability & Society, 24(6), 771–784. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687590903160266

- Haegele, J., Hersman, B., Hodge, S., Lee, J., Samalot-Rivera, A., Saito,E Silva, A. C. (2017). Students with disabilities in Brazil, Japan, South Korea, and the United States. In A. J. S. Morin, C. Maiano, D. Tracey, & R. G. Craven (Eds.), Inclusive physical activities: International perspectives (pp. 287–307). Information Age Publishing.

- Haslett, D., & Smith, B. (2020). Viewpoints toward disability: Conceptualizing disability in adapted physical education. In J. A. Haegele, S. A. Hodge, & D. R. Shapiro (Eds.), Routledge handbook of adapted physical education (pp. 48–64). Routledge.

- Hollinsworth, D. (2013). Decolonizing indigenous disability in Australia. Disability & Society, 28(5), 601–615. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2012.717879

- Kim, E. (2017). Curative violence: Rehabilitating disability, gender, and sexuality in modern Korea. Duke University Press.

- Krane, V. (2001). One lesbian feminist epistemology: Integrating feminist standpoint, queer theory and cultural studies. The Sport Psychologist, 15(4), 401–411. https://doi.org/10.1123/tsp.15.4.401

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lieblich, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis, and interpretation. Sage.

- McGannon, K. R., & Smith, B. (2015). Centralizing culture in cultural sport psychology research: The potential of narrative inquiry and discursive psychology. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 17, 79–87. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2014.07.010

- McRae, L. (2018). Disciplining disability: Intersections between critical disability studies and cultural studies. In K. Ellis, R. Garland-Thomson, M. Kent, & R. Robertson (Eds.), Manifestos for the future of critical disability studies (pp. 217–229). Routledge.

- Meekosha, H. (2004). Drifting down the gulf stream: Navigating the cultures of disability studies. Disability & Society, 19(7), 721–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/0968759042000284204

- Meekosha, H. (2011). Decolonising disability: Thinking and acting globally. Disability & Society, 26(6), 667–682. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.602860

- Meekosha, H., & Shuttleworth, R. (2009). What’s so ‘critical’ about critical disability studies? Australian Journal of Human Rights, 15(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/1323238X.2009.11910861

- Miller, A. S., & Kanazawa, S. (2000). Order by accident: The origins and consequences of conformity in contemporary Japan. Routledge.

- Nguyen, X. T. (2018). Critical disability studies at the edge of global development: Why do we need to engage with southern theory? Canadian Journal of Disability Studies, 7(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.15353/cjds.v7i1.400

- North, J. (2013). Philosophical underpinnings of coaching practice research. Quest, 65(3), 278–299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2013.773524

- Peers, D., Spencer-Cavaliere, N., & Eales, L. (2014). Say what you mean: Rethinking disability language in adapted physical activity quarterly. Adapted Physical Activity Quarterly, 31(3), 265–282. https://doi.org/10.1123/apaq.2013-0091

- Qi, J., & Ha, A. S. (2012). Inclusion in physical education: A review of literature. International Journal of Disability Development and Education, 59(3), 257–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2012.697737

- Richardson, L. (2000). Evaluating ethnography. Qualitative Inquiry, 6(2), 253–255. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040000600207

- Riddell, S., & Watson, N. (2007). Disability, Culture and Identity. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Ryba, T. V., & Schinke, R. J. (2009). Methodology as a ritualized Eurocentrism: Introduction to the special issue. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(3), 263–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671909

- Ryba, T. V., Schinke, R. J., & Tenenbaum, G. (2010). The cultural turn in sport psychology. Fitness Information Technology.

- Ryba, T. V., Stambulova, N. B., Si, G., & Schinke, R. J. (2013). ISSP position stand: Culturally competent research and practice in sport and exercise psychology. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(2), 123–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2013.779812

- Ryba, T. V., & Wright, H. K. (2005). From mental game to cultural praxis: A cultural studies model’s implications for the future of sport psychology. Quest, 57(2), 192–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2005.10491853

- Ryba, T. V., & Wright, H. K. (2010). Sport psychology and the cultural turn: Notes toward cultural praxis. In T. V. Ryba, R. J. Schinke, & G. Tenanbaum (Eds.), The cultural turn in sport psychology (pp. 3–28). Fitness Information Technology.

- Schinke, R. J., McGannon, K. R., Parham, W. D., & Lane, A. M. (2012). Toward cultural praxis and cultural sensitivity: Strategies for self-reflexive sport psychology practice. Quest, 64(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/00336297.2012.653264

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/1750984X.2017.1317357

- Sparkes, A. C., & Smith, B. (2009). Judging the quality of qualitative inquiry: Criteriology and relativism in action. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 10(5), 491–497. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2009.02.006

- Spencer, N. L. I., Peers, D., & Eales, L. (2020). Disability language in adapted physical education: What is the story? In J. A. Haegele, S. A. Hodge, & D. R. Shapiro (Eds.), Routledge handbook of adapted physical education (pp. 131–144). Routledge.

- Thambinathan, V., & Kinsella, E. A. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies in qualitative research: Creating spaces for transformative praxis. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 20, 16094069211014766. https://doi.org/10.1177/16094069211014766

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Waldschmidt, A. (2017). Disability goes cultural. In A. Waldschmidt, H. Berressem, & M. Ingwerser (Eds.), Culture-theory-disability (pp. 19–28). Transcript-Verlag.

- Watson, N., & Vehman, S. (2020). Routledge handbook of disability studies (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Willig, C. (2019). What can qualitative psychology contribute to psychological knowledge? Psychological Methods, 24(6), 796–804. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000218

- Xu, S. (2002). The discourse of cultural psychology. Culture & Psychology, 8(1), 65–78.