ABSTRACT

In recent decades, a new generation of greenbelts has developed that are embedded within dynamic regionalism processes. Governance of these greenbelts is increasingly being challenged by institutional arrangements requiring coordination across multiple policy fields, territorial jurisdictions and policy levels – complexities that are not yet reflected within the literature. The paper explores how vertical, horizontal and territorial coordination problems shape the development of greenbelts in southern Ontario (Canada) and the Frankfurt region (Germany). It is concluded that regional greenbelts need new policy approaches and institutional reforms to manage the governance challenges facing this new generation of greenbelts.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

The greenbelt concept has evolved since its introduction more than a century ago, taking on new meanings, influenced by evolving planning discourses. Greenbelt policies from the late 19th and early 20th centuries were based on an industrial heritage and created city–hinterland divisions. The greenbelt concept spread internationally from England after the Second World War (Sturzaker & Mell, Citation2017), and cities implemented these policies with diverse results (Han & Go, Citation2019). In recent decades, a new generation of greenbelts has emerged. Contemporary greenbelt policies often address regionalized suburbanization and pursue multifunctional policy goals, including economic development, nature protection and growth containment. Similarly, as the greenbelt concept has shifted, regional governance structures have evolved in recent decades faced with territorial competition and state deregulation (Keil et al., Citation2017). These coevolving trends and societal shifts create new challenges to govern greenbelts and raise questions about how best to manage greenbelts in today’s changing urban regions.

As greenbelt policies have become more ambitious in addressing multiple policy goals and reaching far into urban regions, we argue that greenbelts are now implanted into complex regional governance arrangements shaping wider socio-spatial relationships. However, managing regional greenbelts involves considerable institutional complexities and governance challenges. Greenbelt policy implementation requires coordination across several policy fields such as housing, farming and nature conservation (horizontal coordination), across numerous policy levels (vertical coordination) and multiple administrative jurisdictions (territorial coordination). Being situated within these increasingly complex institutional environments raises questions about whether new-generation greenbelt policies can deliver on their promises.

Greenbelt policies inherited from previous eras are partially seen as anachronistic (Sturzaker & Mell, Citation2017), and in response, alternative greenspace protection models such as green infrastructure have become popular (Lennon, Citation2015). Recent greenbelt approaches often involve flexible governance arrangements with actors from multiple sectors and territorial jurisdictions. Yet, the institutional complexities and governance challenges involved in managing new-generation greenbelts are not well reflected within the literature. To explore the challenges involved in regional greenbelt governance, we selected two examples of greenbelts in southern Ontario (Canada) and the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region (Germany). Both greenbelts were established within the past 25 years under different governance models. Ontario’s Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) greenbelt policies reflect a top-down approach, while the Frankfurt Rhine-Main greenbelt is managed by a public–private partnership (PPP). Comparing these greenbelts’ different institutional designs allows for an examination of the governance challenges involved in greenbelt management under different institutional settings. In this paper, we analyse how the institutional and governance arrangements in southern Ontario and the Frankfurt region impact greenbelt management. How is greenbelt implementation in both regions coordinated across numerous territorial jurisdictions, policy domains and policy levels, and how could it be more effectively governed?

The paper is structured as follows. The methodology section outlines the case study selection rationale. The paper then reviews greenbelt debates from a governance and institutional perspective and discusses the conceptual framework being applied to this research. This is followed by an overview of the GGH and Frankfurt regions and their respective greenbelts. Finally, the paper discusses the governance challenges of managing both greenbelts, structured along the dimensions of vertical, horizontal and territorial coordination. Through a comparative analysis of the cases, it is found that the GGH greenbelt policies have effectively halted growth within the greenbelt, yet have encouraged leapfrog development. The Rhine-Main region’s greenbelt policies have stimulated tourism promotion, but hardly provide an effective mechanism for growth containment. Thus, it is concluded that while the GGH greenbelt has been more effective in achieving more ambitious policy goals, both cases have mixed outcomes.

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This research responds to calls for comparison across diverse urban contexts (Robinson, Citation2011). Based upon a literature review, it builds a typology of greenbelt planning signalling a shift from traditional models from the late 19th century to a new generation of greenbelts. This paper focuses on a 15-year period (2003–18) in the GGH region under a provincial Liberal government. The Frankfurt case reflects a similar timeframe (2005–18), beginning with the establishment of a regional greenbelt agency: the Regionalpark Ballungsraum Rhein-Main GmbH. The empirical research is based on 79 interviews: 42 within the GGH region (August 2014–June 2019) and 37 within the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region (September 2017–July 2019). Interviews were held with representatives from municipal, regional and provincial governments, environmental activists, farmers and academics. Interview participants were selected to include major stakeholder groups responsible for greenbelt management. The interviews focused on how greenbelt implementation has been coordinated across multiple policy levels, stakeholders and municipalities. This was complemented by a review of government policy documents and non-governmental organization (NGO) reports from both cases. Using our conceptual framework, the interview transcripts were analysed to identify how each case’s institutional environment impacts greenbelt implementation.Footnote1

The case study selection rationale was that the GGH greenbelt and Frankfurt’s regional greenbelt, the Regionalpark RheinMain, share various commonalities. Both are examples of the new generation of greenbelts: they have a regional scope, their policies are set by provincial or state governments, and their implementation requires coordination between numerous stakeholders in various policy domains, at multiple policy levels and across municipalities. However, these cases exhibit different institutional designs of greenbelt management (see above). By comparing the different institutional arrangements, we reflect on governance challenges involved in greenbelt implementation.

THE EVOLUTION OF GREENBELTS: FROM TRADITIONAL MODELS TO A NEW GENERATION OF GREENBELTS

Greenbelts are one of the most well-known planning approaches to control urban growth. Their purposes and governance complexities have evolved since their origin over a century ago ().Footnote2 While the greenbelt concept is associated with numerous greenspace projects in the late 19th and early 20th centuries (Freestone, Citation2002), greenbelts are most strongly connected to UK planning and the Garden City movement. Traditional greenbelts were developed before the Second World War in response to problems associated with industrialization, largely implemented in top-down planning systems. Introduced by national or local governments, traditional greenbelt policies were designed to protect farmland, provide greenspaces for urban residents and reinforce city–countryside divisions (Sturzaker & Mell, Citation2017). However, this top-down approach creates challenges as municipalities often take discretion in applying higher level government policies, resulting in inconsistent greenbelt implementation.

Table 1. Typology of greenbelts.

Following the Second World War until the late 1970s, the greenbelt concept reached peak popularity in planning discourses, spreading internationally based on the UK model. Modernist greenbelts diverged from their traditional counterparts as cities adapted greenbelt policies to their needs, resulting in multiple spatial forms and diverse policy goals (Amati, Citation2008). However, compared with the previous period, greenbelts established after 1945 often displayed a restrictive planning approach with their main purpose being urban growth containment (Hall, Citation2007). Greenbelt policies adopted during the early post-Second World War years reflected modernist planning principles, based on an assumption that other jurisdictions could apply the greenbelt model as effectively as in England (Amati, Citation2008). However, international greenbelt examples achieved mixed results (Han & Go, Citation2019). The traditional top-down approach evolved during this time to include increased state and regional government involvement and more decentralized governance models, including increasing civil society influence on greenbelt planning. Also, during this period, planning deregulation forced some governments to alter their greenbelt policies (Amati, Citation2008).

Since the 1990s, a new generation of greenbelts has emerged, with the greenbelt concept being rethought to reflect more complex thinking about urban regions. Traditional post-Second World War suburbs have evolved towards regionalized in-between cities (Sieverts, Citation2003) or post-suburban forms of regional urbanization (Phelps & Wu, Citation2011), requiring new governance arrangements (Hamel & Keil, Citation2015). Reflecting the shifts in urban regions in recent decades (Paasi & Metzger, Citation2017), greenbelts are now embedded within regionalized suburban landscapes, reflected in adaptations to greenbelt planning. While this new generation of greenbelts continues to pursue policy goals such as urban growth containment and farmland protection, they go beyond their modernist predecessors to include new objectives such as providing ecosystem services, contributing to economic development, and climate mitigation and adaptation. Also, given the popularity of smart-growth planning principles (Filion & McSpurren, Citation2007), greenbelts are now key components of integrated land-use planning frameworks designed to manage regional development better (Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012). However, the larger number of policy fields incorporated into greenbelt policies increases the number of stakeholders at multiple policy levels involved in policy implementation, subsequently increasing the governance complexities involved in their management. Compared with modernist greenbelts, however, these recent greenbelts often have flexible governance approaches, with less higher level government involvement and an increased role of special-purpose bodies and NGOs in greenbelt management, reflecting current environmental planning trends.

THE INSTITUTIONAL DIMENSIONS OF THE GOVERNANCE OF REGIONAL GREENBELTS

As the new generation of greenbelts often cross administrative boundaries and are shaped by multiple stakeholders, we argue that applying a regional governance lens is necessary in order to analyse regional greenbelt implementation. Greenbelt development has evolved as the state itself has reorganized (Jessop, Citation2000) and traditional forms of spatial planning led by municipalities prove insufficient to tackle complex public responsibilities. Similar to other regional development processes, the governance of regional greenbelts happens through ‘network-like coordination … processes and comprises vertical and horizontal coordination of state and non-state actors in a functional space’ (Willi et al., Citation2018, p. 12). Greenbelt decision-making also increasingly involves civil society groups and special-purpose bodies, reflecting recent trends to delegate public service provision to the private sector (Stoker, Citation1998). New-generation greenbelts are often regional in spatial scope, thus involving multiple municipal and regional jurisdictions. While greenbelts are now embedded within these complex governance and institutional structures, these greenspaces are not highlighted within regional governance debates. Some literature explores the regionalism of greenbelts (Addie & Keil, Citation2015; Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012). However, the institutional challenges of regional governance are often not addressed, with some exceptions (Röhring & Gailing, Citation2005). Some literature compares greenbelt practices in several countries (Amati, Citation2008; Carter-Whitney, Citation2010), yet these hardly analyse the institutional dimensions of greenbelt governance.

As greenbelt development reflects the institutional environments in which they were established (Pond, Citation2009), we argue that an institutional perspective is needed to understand greenbelt governance. Han and Go (Citation2019) find that institutional structures play a key role in shaping greenbelt policies and determine the greenbelt governance model applied in each case. The types of planning regulations available to establish a greenbelt such as a designation or zone depend on that location’s land-use planning regime (Taylor, Citation2019a), contributing to the variation seen in international greenbelt examples. Greenbelt governance is structured by institutions, which we define as rules and practices embedded within structures of meaning that are fairly resistant to changing circumstances (March & Olsen, Citation2011). Institutions thus enable and constrain actors, distribute power relations, create order (March & Olsen, Citation2011), and represent the structures necessary for governing processes.Footnote3 The main institutional perspectives within the literature includes historical institutionalism, rational choice institutionalism and sociological institutionalism (Lowndes, Citation2010; Peters, Citation2019), with each approach explaining processes of institutional stability and change, and the interaction between institutions and individuals in change processes (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996). Within (urban and) regional governance debates, institutions are viewed as essential for spatial development, as the design of institutions structures the governance of cities and regions and defines (sub)urbanization (Taylor, Citation2019b). There is discussion within the literature about how best to govern urban regions, with prominent institutional approaches including the metropolitan reform school, the public choice model and new regionalism (Glass, Citation2018; Nelles, Citation2012). Apart from these different approaches to institutional reforms in regional governance, academic debates have also addressed alleged shifts away from formal institutional frameworks towards more flexible, soft spaces of governance (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009). Once established, urban and regional planning institutions are often resistant to change or develop in a path-dependent way. Given their longevity and path dependency, institutional arrangements in greenbelt governance can impact stakeholders’ behaviour who anticipate the continuance of greenbelt institutions, adjusting their actions accordingly (Mace, Citation2018).

By applying an institutional perspective to greenbelt planning, we introduce three institutional dimensions influencing the effectiveness of regional greenbelt governance: vertical, horizontal and territorial coordination.Footnote4 A key concern impacting greenbelt management is the vertical coordination of greenbelt policies between stakeholders at multiple policy levels (e.g., municipal, regional, provincial or state). Greenbelt policies often have a vertical institutional design where legislation is set by higher levels of government and its implementation is overseen by lower level authorities, resulting in coordination challenges (Carter-Whitney, Citation2010). How greenbelt policies are framed by senior government authorities is important, as it structures local stakeholders’ responses to these policies (Han & Go, Citation2019).

At the same time, effective greenbelt management necessitates horizontal coordination across multiple policy domains at the same level – nature conservation, agriculture and housing – with the private and civil society stakeholders shaping those domains. Greenbelt implementation is often influenced by dominant groups such as developers (Cadieux et al., Citation2013), causing politics and stakeholders’ self-interests to impact policy outcomes.

Finally, regional greenbelt management requires territorial coordination across multiple municipalities. However, administrative jurisdictions rarely match a greenbelt’s spatial scope, resulting in institutional ‘misfits’ and coordination problems (Young, Citation2002). Local authorities often take discretion in greenbelt policy application, resulting in uneven greenbelt implementation. Bringing together these three forms of institutional coordination allows for an analysis of the institutional complexities of greenbelt governance to examine the difficulties of new-generation greenbelt management, which will be discussed below.

TWO DIFFERENT INSTITUTIONAL MODELS OF REGIONAL GREENBELT PLANNING

This section provides an overview the GGH and the Frankfurt Rhine-Main regions’ institutional contexts and their greenbelts. These two regions share geographical and governance similarities to anchor this comparative research. Both global city regions are financial centres, characterized by strong demographic growth and regionalized suburbanization (Keil et al., Citation2017). These regions also share common governance characteristics including being in a federal country, a history of contentious institutional reforms and fragmented public service provision (Nelles, Citation2012). However, these regions also differ in institutional features: Ontario has a two-tiered government structure between the provincial government and municipalities, while the Frankfurt region’s institutions include municipalities, intermunicipal authorities at various regional scales and a two-tiered state government (Land). As outlined below, both regions have adopted regional greenbelts in recent decades, while each has pursued different approaches to achieve its policy goals.

The GGH greenbelt: a top-down approach to greenbelt planning

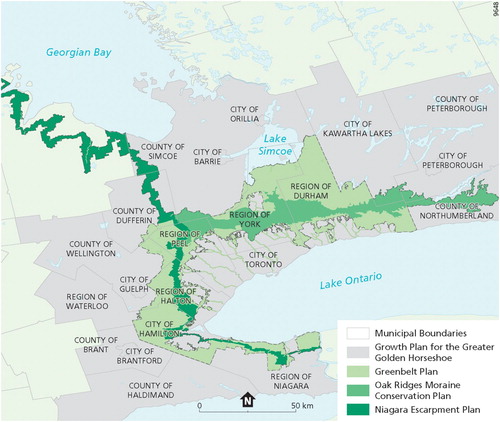

As Ontario’s economic engine, the GGH region covers approximately 32,000 km2 and includes large cities, towns and rural areas including 110 municipalities () (Allen & Campsie, Citation2013). In 2016, the GGH had a population of 9 million, which is expected to grow to 13.48 million residents by 2041 (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Citation2019). The GGH has complex institutional structures including the Ontario provincial government, a municipal level divided between upper, lower and single-tier municipalities and numerous special-purpose organizations.

Figure 1. The Greater Golden Horseshoe (GGH) region, Canada.

Sources: Ministry of Municipal Affairs (Citation2017); Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing (Citation2019).

The greenbelt is part of an ambitious regional planning framework introduced by a Liberal provincial government (2003–18) designed to rethink how residents live and work within the GGH for future generations. The greenbelt legislation went far beyond traditional greenbelt policy goals: as a state spatial strategy, it generated new forms of regional governance (Macdonald & Keil, Citation2012). In 2005, the Greenbelt Act passed by the provincial government (referred to herein as the Province) allowed for the creation of a Greenbelt Plan, also released that year. Spanning approximately 7200 km2 across the GGH, the greenbelt’s policy goals include protecting farmland and environmentally sensitive areas, providing recreational spaces and mitigating and adapting to climate change (Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Citation2017). Billed as the largest permanently protected greenbelt in the world, the GGH greenbelt contains some of Canada’s most productive farmland. Building upon nature conservation areas such as the Oak Ridges Moraine and the Niagara Escarpment, the greenbelt’s primary land-uses include agriculture, a natural heritage system and rural settlement areas. The Province created two organizations to support policy implementation: first, the Greenbelt Council comprised stakeholders that provide advice to government about plan implementation; and second, the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation promote the greenbelt through educational activities. Because the greenbelt has a vast territorial scope and includes multiple land-uses, the Greenbelt Plan intersects with several provincial plans and policies from conservation authorities, municipalities and the federal government. Thus, the Greenbelt Plan is read in conjunction with other policies related to agriculture, nature conservation and infrastructure, resulting in its implementation being influenced by a complex policy environment involving stakeholders at numerous policy levels. When it was introduced, the Greenbelt Plan was contested, as farmers, developers and municipalities resented the development restrictions imposed by the plan. Over time, however, many of these stakeholders’ original concerns have shifted to the acceptance of the Greenbelt Plan (interviews 1 and 2), reflecting the now wide public support for these policies.

The Greenbelt Plan was designed together with the ‘Places to Grow’ legislation to manage regional development. The greenbelt creates an urban containment boundary, with the Growth Plan directing development into built-up areas. The Places to Grow Act allowed for the preparation of growth plans, and in 2006 the first plan for the GGH was released. This 25-year growth plan was designed to manage regional growth until 2031 (which was extended until 2041), secure economic prosperity and encourage urban intensification (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Citation2019). The Greenbelt and Growth Plans are to be reviewed by the provincial Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing every decade to assess their effectiveness, and revised versions of these plans were released in 2017. During this review process is the only time that the Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing can make amendments to the greenbelt’s protected areas. However, these changes cannot decrease the greenbelt’s total area (Ministry of Municipal Affairs, Citation2017).

The Greenbelt and Growth Plans rely on an institutional design based on a vertical hierarchical structure, reflecting Ontario’s provincially led land-use planning system (). The province sets the direction for land-use planning through the Planning Act and the Provincial Policy Statement. Certain areas of Ontario have provincial plans with more detailed policies such as the Greenbelt Plan. Municipalities are then responsible for implementing provincial policies through their official plans and must make their planning decisions conform with provincial interests. However, if there are disagreements regarding local planning decisions, then appeals can be made to the Local Planning Appeal Tribunal (LPAT). The LPAT is a provincially appointed tribunal that makes decisions regarding municipal land-use planning matters, providing an important dispute resolution mechanism in the land-use planning system. Thus, Ontario’s greenbelt policies display a top-down approach to greenbelt planning, with its implementation being impacted by provincial–municipal relations and coordination problems between local stakeholders, which will be explored below.

Table 2. Land-use planning system in Ontario.

The Regionalpark RheinMain: a decentralized model of greenbelt planning

The Frankfurt Rhine-Main region is embedded within a complex institutional structure. At its core lies the Greater Frankfurt region, which is a politically defined territory of a network of urban centres and towns, with the city of Frankfurt as its largest urban node. It includes 2.34 million residents and 75 municipalities (Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain, Citation2018). In this suburbanized region, municipal land-use planning has been upscaled to the level of the Regional Authority Frankfurt RheinMain. The Greater Frankfurt Area is the urbanized core of the larger Frankfurt Rhine-Main Metropolitan region, which has 5.7 million inhabitants and stretches over three federal states (Länder) (). Greater Frankfurt has experienced strong population growth in recent years and is predicted to grow by 191,000 residents by 2030 (Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain, Citation2018). It is known as a transportation hub, a global financial centre and is shaped by strong functional interdependencies between its core cities and their surrounding region.

Figure 2. The Frankfurt Rhine-Main Metropolitan Region and the Greater Frankfurt Region, Germany.

Source: Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain (Citation2018).

Regional greenspace management in Greater Frankfurt is influenced by complex institutional structures and partially overlapping spatial planning authorities at the municipal, intermunicipal, regional and Länder level, by specific institutional arrangements in nature conservation and by multiple special-purpose bodies ().

Table 3. Spatial planning system in the Frankfurt Rhine-Main region.

In Germany’s federal system, the main institutional resources and operational tasks in spatial planning rest with the Länder and the municipalities. In line with the ‘counterflow principle’, each level is responsible for planning on its level, but it must consider or integrate plans of the super- and subordinate levels (Schmidt, Siedentop, & Fina, Citation2018). It thus combines top-down and bottom-up approaches. In Hesse, a Länder development plan (Landesentwicklungsplan) sets general objectives, which are then specified in the regional plan for South Hesse (Regionalplan). Municipalities exercise their constitutional right to planning by preparing a two-tier system of land-use plans: a (preparatory) land-use plan outlining all types of land-uses for the municipality and legally binding zoning plans for settlement areas that regulate the amount and type of building activity. Apart from six cities in the Ruhr region, Greater Frankfurt is the only German region where a regionalized land-use plan (regionaler Flächennutzungsplan) has been adopted. The Regional Authority (Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain), which is responsible for development in the whole metropolitan region, prepares such a regionalized land-use plan for its urban core, that is, its 75 member municipalities in Greater Frankfurt. Both the regionalized land-use plan as well as the regional plan prioritize the confinement of development along growth corridors and within existing urban areas, greenspace preservation and the Regionalpark RheinMain’s expansion (Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain, Citation2010). However, as continuing suburban growth demonstrates, planning goals to contain peripheral growth can be undermined by municipalities seeking to boost tax revenues by attracting investment in local development (Monstadt & Meilinger, Citation2020).

The spatial plans at the different levels integrate sectoral plans for nature conservation and development at the Länder, regional and municipal level (Landschaftsplanung), which promote greenspace protection and green corridor development. These plans are complemented by various types of nature conservation areas that protect specific spaces within the Regionalpark from development. Finally, the national nature conservation law provides financial compensation schemes for the destruction of natural areas. Here, the Regionalpark has benefited from such a financial compensation by the Frankfurt airport operator who had to transfer an amount of €800,000 per year since 1997 to the Regionalpark RheinMain agency, with these funds being used to develop park projects (Dettmar, Citation2012; Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). Apart from its complex spatial planning and nature conservation arrangements, the Frankfurt region is also known for its delegation of public tasks to numerous special-purpose organizations (Hoyler et al., Citation2006). This is also the case for the development of the regional greenbelt, which has been delegated from the Regional Authority to a special greenbelt agency: the Regionalpark Ballungsraum Rhein-Main GmbH. Thus, this greenbelt agency is embedded within a fragmented regional institutional environment, influenced by various spatial planning and nature conservation authorities and other special-purpose bodies operating at different spatial scales.

Similar to many other German regions, Frankfurt’s regional greenbelt is termed a regional park. Introduced in the 1990s with little national policy guidance, regional parks take a flexible governance approach involving state, regional and municipal authorities (Siedentop, Fina, & Krehl, Citation2016; Gailing, Citation2007). Established in 1994, the Regionalpark RheinMain is currently 4463 km2 and was designed as a regional greenspace network, including the Frankfurt and Offenbach’s municipal greenbelts, the Hessische Ried agricultural area and the Nature Park Hochtaunus. Similar to the Ontario case, the Regionalpark has multifunctional policy goals including greenspace protection, providing recreational areas and promoting regional identity (Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain, Citation2010). The Regionalpark is also meant to control the direction of regional development patterns and its primary land-uses are agriculture, forestry, recreation and nature conservation areas. Following an initial period of management by the Regional Authority’s predecessor, the Greater Frankfurt planning association, a regional greenbelt agency was founded in 2005 (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). Thus, the park is managed by a special-purpose body which is organized as a PPP with its implementation delegated to six intermunicipal implementation bodies responsible for developing subprojects. This greenbelt agency is supported by 15 shareholders, including 123 municipalities, the Regional Authority and the State of Hessen (Dettmar, Citation2012). In contrast to the GGH greenbelt, the Regionalpark is weakly protected. Apart from single areas protected by nature conservation law, its only formal protection is under the ‘regional green corridors’ (Grünzüge) land-use category in the regional plan and the State Development Plan Hesse. Generally, there is broad public and political support for the Regionalpark’s policy goals (interview 3). However, regarding implementation, the greenbelt agency has no effective mechanisms for allocating land-uses and municipalities’ membership within the Regionalpark is voluntary. Thus, the redistribution of land-use rights happens through the regionalized land-use plan and nature conservation laws. This process results in implementation problems such as creating land-use conflicts and opportunities for regional growth politics to undermine the Regionalpark’s goals.

To summarize, both regional greenbelts reflect a new generation of greenbelt planning with their multiple policy goals and diverse stakeholder involvement. However, their institutional design differs considerably: while the GGH greenbelt is supported by strong policy protection and a regional growth plan, the Regionalpark RheinMain benefits from protection through the spatial plans’ promotion of a greenspace network and the designation of single nature conservation areas. The following sections will analyse and compare the governance challenges involved in developing regional greenbelts in the GGH and the Frankfurt metropolitan region’s institutional environments.

INSTITUTIONAL COMPLEXITIES AND GOVERNANCE CHALLENGES OF THE NEW GENERATION OF GREENBELTS

In this section, we examine how greenbelt policy implementation in both cases is coordinated between stakeholders across multiple policy levels, policy fields and numerous jurisdictions. The analytical framework of vertical, horizontal and territorial coordination allows one to discuss the advantages and disadvantages of each greenbelt planning approach and to analyse the governance challenges involved in managing new-generation greenbelts.

Vertical coordination

Greenbelt policies are often set by higher level of governments and should then be implemented by lower policy levels (Carter-Whitney, Citation2010). Often, the advantages of top-down approaches are highlighted as they give municipalities’ clear direction for greenbelt policy implementation (Han & Go, Citation2019). However, these top-down models do not guarantee compliance, as municipalities often attempt to circumvent such regulations unless effective evaluation and sanctioning mechanisms are present.

In Ontario, greenbelt policies are implemented through a top-down institutional design, with plan implementation strongly influenced by provincial–municipal relations. Ontario’s provincial–municipal relationship is shaped by legislation that formally limits municipal autonomy, placing municipalities in a subordinate position to the provincial government. Provincial–municipal relations are characterized by some municipalities’ resistance to provincial initiatives, a history of shifting provincial involvement in local matters and contentious institutional reforms (Côté & Fenn, Citation2014). Tensions within this relationship are reflected in municipal non-compliance with provincial policies. Many municipalities have supported the Greenbelt and Growth Plans, while others have framed both plans as restrictions placed upon them. During the plans’ initial implementation phase (2005–15), municipalities took diverse approaches to achieve or circumvent these policy goals (Burchfield, Citation2016), resulting in inconsistent plan implementation.

A weakness of the top-down greenbelt approach is its dependence on consistent higher level government mechanisms of support, evaluation and sanctioning in cases of non-compliance. In Ontario, not all these support systems have been continuously applied to ensure greenbelt implementation. Compared with other international cases, the GGH greenbelt has one of the strongest legal frameworks (Carter-Whitney, Citation2010) and its policies are regularly reviewed. While municipalities lacked clear provincial guidance during the Greenbelt and Growth Plans’ initial implementation phase (Burchfield, Citation2016), the Province took a proactive approach during the 2015 policy review (interview 4). While there are no specific non-compliance measures of the Greenbelt Plan, all land-use planning (non)conformity matters are governed by the provincial Planning Act. Under this Act, the Province has tools available to override municipal non-decisions, yet these sanctions are rarely invoked.Footnote5 While the Liberals committed to a regional planning agenda, Frisken (Citation2001) finds the Ontario government has a record of fluctuating involvement in regional affairs. This raises concerns about what happens to greenbelt planning when government priorities’ shift, as these policies are susceptible to reform when political climates evolve. While the Liberals upscaled land-use planning to the new policy level of the GGH, they failed to establish a GGH regional government.Footnote6 This lack of formal regional institutions has been a persistent problem for decades. Indeed, the Liberals assumed the role of regional government in absentia, as has happened throughout Ontario’s history of regional governance (Frisken, Citation2001). Thus, while Ontario’s top-down approach should in theory promote compliance of greenbelt implementation, these problems challenge its vertical institutional design’s effectiveness.

In contrast, the Frankfurt region’s greenbelt has a more decentralized approach. Policy formulation and implementation are loosely coordinated by the Regionalpark agency and municipalities having flexibility with implementation. The State of Hesse has a limited role in greenbelt planning, as the State Development Plan Hesse and the regional plan provide only general guidance on greenspace protection. By contrast, the Regional Authority has more involvement in Regionalpark planning through its planners’ collaboration with the greenbelt agency’s staff on relevant activities (interview 3). However, the greenbelt agency’s policies provide limited guidance to municipal land-use planning, making the greenbelt vulnerable to local self-interests. Thus, apart from some protected areas under nature conservation law, greenbelt management has been delegated to a weakly institutionalized special-purpose body. The greenbelt agency has no spatial planning authority over its territory, limited staff capacity, faces financial uncertainty and must consult with multiple government and private sector organizations to complete its initiatives. Owing to its limited planning jurisdiction, this agency’s primary mandate shifted from its initial growth containment ambitions in 2008 to tourism promotion (Rautenstrauch, Citation2015). Given these constraints, the effectiveness of the greenbelt agency is limited.

When analysing the vertical institutional design of our cases, Ontario’s top-down model provides stronger greenbelt policy protection compared with the Regionalpark’s decentralized approach. However, Ontario’s vertical institutional structure faces coordination difficulties at the local level, which will be explored in the next section.

Horizontal coordination

In both cases, greenbelt policy implementation happens at the municipal level and is influenced by challenges of coordinating multiple policy fields and their stakeholders. In Ontario, greenbelt policies stimulated better governance practices by facilitating stakeholder collaboration. Many municipalities have supported the Greenbelt Plan by developing projects with local partners (Hertel & Markovich, Citation2015). The Greenbelt Plan also supported some municipalities’ efforts to move away from greenfield development, because as a municipal politician said ‘the greenbelt has reinforced and built on [our] perspective [of] what we were already doing, and has given it another level of protection and a regulatory regime’ (interview 1). The greenbelt policies have benefited from dedicated leaders that advocate for its protection. New organizations were established that increase stakeholders’ participation opportunities such as the Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. Through this foundation and civil society groups’ efforts to promote the GGH greenbelt, it has broad public support, which is essential to a greenbelt’s long-term success (Carter-Whitney, Citation2010). The success of the popularization of greenbelt sensitivities through these planning mechanisms can be measured over time by the increased community support in and around the greenbelt for the project overall.Footnote7

A persistent challenge, however, is that municipal growth politics may still undermine greenbelt policy objectives. Some municipalities ‘look at the greenbelt largely as an impediment to their economic viability, they feel hemmed-in, they feel they can’t attract new residential and non-residential development. They’re just surrounded by the greenbelt, which is strangling them’ (interview 1). These municipalities want to continue their business-as-usual development practices and can be influenced by growth coalitions comprised of politicians and developers. Ontario’s development industry has a major impact on municipal politics through contributions to local election campaigns. Indeed, the development industry is a key sponsor of political candidates which significantly influences local election results through donations, creating councils that favour developers’ interests (Campaign Fairness Ontario, Citation2016). These pro-development councils in some municipalities continue to reproduce low-density development patterns, undermining the Greenbelt and Growth Plans’ ambitions. While these municipalities must respect provincial planning legislation, they still may not fully embrace these policies. For example, during the first 10 years of the Growth Plan’s implementation, most municipalities used the lowest possible intensification targets allowed under the plan (Burchfield, Citation2016). Thus, due to the diverse municipal responses to these plans and delays in updating local official plans to conform to provincial policies (Burchfield, Citation2016), these plans’ initial implementation had problems, resulting in inconsistent policy application.

In the Frankfurt region, the Regionalpark facilitates better governance practices. For example, a university-based researcher said that the Regionalpark has been successful at

bringing together a lot of politicians of different colors, [giving] them the opportunity to discuss and to develop together something because all of them, [it] does not matter if they are Conservative, or Liberal or Social Democrats, are interested in keeping the value of [the] landscape. This is the connecting thing. All of them are interested in giving people [the] possibility for recreation and discovering landscape because this is very much asked [for] by the people.

Moreover, the Regionalpark’s weak institutional design combined with regional growth politics could undermine the greenbelt policies’ effectiveness. Despite the strong spatial planning system and regionalized land-use planning promoting compact development, growth coalitions and intermunicipal competition influence regional growth resulting in continued suburbanization (Monstadt & Meilinger, Citation2020). Likewise, the greenbelt agency has no capacity to shape regional growth patterns, rather focusing on easy-to-manage tourism goals that do not face resistance from growth coalitions. Politicians have mostly respected the greenbelt policies as a former staff member of the greenbelt agency stated that within the past 25 years, ‘there was no, or very few cases, where land that is a Regionalpark route or part of [a route] was lost to development. The Regionalpark policy of channelling the development on the whole [has been] moderately successful’ (interview 6). However, this greenspace’s policies can still be undermined by regional growth politics.

To conclude, both greenbelt policies have increased governance capacity by strengthening partnerships. However, the increased multifunctionality of greenbelt policies results in intersections with diverse policy fields and their stakeholders, thus creating conflicts. In both cases, greenbelt management has been influenced by powerful interests such as developers and private funders that strongly shape and partially restrict greenbelt policy implementation.

Territorial coordination

Effective regional greenbelt implementation requires coordination across numerous territorial jurisdictions. Within urban regions, however, there are often mismatches between administrative and functional boundaries, causing institutional ‘misfits’ and coordination challenges (Young, Citation2002). Greenbelt policies are designed to prevent urban development within the greenbelt’s boundaries. As a result, urban growth often gets displaced elsewhere resulting in leapfrog development, which is characterized by development jumping over a greenbelt to farmland on the other side. Leapfrog development is problematic as it involves constructing roadways across a greenbelt that fragments greenspaces (Tomalty & Komorowski, Citation2011). In Ontario, the Greenbelt Plan has been effective in directing development to cities and away from farmland within the greenbelt (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Citation2015). According to planners, farmers and environmental activists (interviews 7–9), greenbelt policies have stimulated leapfrog development. However, our research indicates that this situation is more complex. The Greenbelt and Growth Plan work together to enable this low-density development to occur. While the Greenbelt Plan provides strong protection for farmland within its boundaries, growth pressures are offset elsewhere and farmland outside of these policies within the GGH can be vulnerable to development. Growth Plan implementation problems such as municipalities adopting low intensification targets and plan amendments allowing low-density development in Simcoe County, have encouraged suburbanization beyond the greenbelt (Tomalty, Citation2015). However, while land speculation beyond the greenbelt is common, there is limited statistical information to confirm the scale of these practices within the GGH, as governments do not keep these records (Tomalty, Citation2015). Regardless, the explosive growth of some communities outside of the greenbelt has created problems including agricultural de-investment (interview 8) and coordination challenges with regional public service provision (interview 9). Also, these development practices particularly impact farmers, as a representative from an agricultural organization said that these landowners

who are in long-term career farming with the intent to pass the operation down [to their children], feel that particularly in those areas, there is a lot of pressure and probably [the] same as in the past, worrying about land being bought by speculators for future growth because it’s outside the greenbelt. It’s sort of fair game. And what’s the long-term meaning of that and what are the long-term implications if we just allow development to jump over and carry on?

In the Frankfurt region, the greenbelt’s implementation is affected by problems related to coordination challenges between different administrative jurisdictions. As an example of an institutional misfit, the Regionalpark is situated within a multilayered territorial structure with the regional planning authority of South Hesse, the Regional Authority of Greater Frankfurt and municipalities operating at different territorial scales than the greenbelt agency, whose jurisdiction is defined by the park’s boundaries (). This complex institutional environment creates challenges for the greenbelt agency to effectively manage the park. For example, for this agency to promote its activities, staff must contact eight different tourism organizations overlapping the park’s area, making it challenging to deliver a consistent greenbelt strategy (interview 5). Due in part to the challenges associated with navigating this institutional complexity, park project development has been delegated to municipalities. Intermunicipal implementation bodies are responsible for delivering park projects, which facilitate governance processes by providing stakeholder engagement opportunities for park users (Krause, Citation2014). However, the delegation of greenbelt implementation to municipalities through small-scale projects prevents the creation of a comprehensive regional greenbelt. These localized initiatives cannot effectively manage regional growth pressures, nor were they designed to do so.

In summary, both cases show that regional greenbelt policy implementation requires coordination across multiple municipalities, producing impacts beyond a greenbelt’s boundaries. Indeed, effective regional greenbelt management requires municipal cooperation to implement policies. While cooperation is a strategy to address coordination problems, both cases are well known for their difficulties with intermunicipal coordination at a regional scale (Nelles, Citation2012), which surely influences greenbelt implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Through a comparative analysis of institutional arrangements of greenbelt management in two regions, this paper explored the governance challenges involved in new-generation greenbelts. By tracing the evolution of greenbelt development, we showed the considerable shifts in the greenbelt concept since its introduction more than a century ago. We analysed how these regions’ institutional environments have impacted their greenbelts’ implementation and pointed to challenges in vertical, horizontal and territorial coordination. While greenbelt policies have facilitated the consolidation of greenbelts in both cases, varied results were achieved in meeting policy goals. In Ontario, for example, greenbelt policies have halted farmland conversions within the greenbelt and directed growth towards cities (Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing, Citation2015), yet stimulated leapfrog development according to stakeholder groups. In the Frankfurt region, the regional greenbelt agency has shifted away from focusing on core greenbelt policy goals such as growth control to promoting tourism, thus hardly providing an effective mechanism in addressing suburbanization. Thus, while our comparative analysis shows that the GGH greenbelt has been more ambitious in achieving multiple greenbelt policy goals such as farmland protection and growth containment, both cases have produced mixed outcomes.

Another result of our research highlights that the complexity of both cases poses serious problems for policy implementation. As our study indicates, there are considerable challenges that come with the multiple policy goals and the regional scope of the recent generation of greenbelts. These greenbelts require policy-makers to collaborate across policy domains and municipalities, while also restricting municipalities and investors’ development interests. Local planners face challenges in implementing these recent greenbelt policies often resulting in inconsistent municipal policy implementation (interview 7). While recent greenbelt policies have surely raised greater awareness of policy interconnectivity and of the need for more integrated greenbelt projects, they also require a high governance capacity to coordinate efforts to confine urban development. Thus, this requires a reprioritization of greenbelt policy goals, with urban growth containment and nature conservation as key concerns. In addition, ongoing monitoring is needed to evaluate the effectiveness of greenbelt policies in achieving their goals and these policies need to be updated regularly to reflect changing regional conditions. Finally, greenbelt policies need to be supported by other policies such as a regional growth plan. Such integrated frameworks are necessary to effectively address regional growth management concerns.

In addition to these policy developments, the effective governance of new-generation greenbelts requires institutional reforms. As regional planning evolves, there is an increased emphasis on flexible institutional approaches including soft governance spaces (Allmendinger & Haughton, Citation2009), the use of special-purpose bodies for public service provision (Lucas, Citation2013), and regional partnerships (Nelles, Citation2012). However, these special-purpose agencies and voluntary arrangements often have limited authority, can only encourage stakeholder collaboration and cannot overcome institutional fragmentation in urban regions. Our research indicates that these collaborative approaches as seen in the Frankfurt case do not ensure effective regional greenbelt policy implementation. Instead, as our Ontario case reflects, greenbelt planning should be integrated into provincial governments or state planning authorities, as these are the most suitable institutions to manage new-generation greenbelts. Senior levels of government have the required statutory powers to establish greenbelt legislation, confine regional growth (Pond, Citation2009) and have jurisdiction over the appropriate territorial scope for regional greenbelt management. Higher levels of government have also been viewed as being more effective at coordinating public policy implementation (Nelles, Citation2012), as these authorities have more resources available than special-purpose bodies to support policy implementation and can enforce compliance mechanisms, if municipalities try to circumvent these regulations. Thus, despite the popularity of flexible greenspace protection approaches (Lennon, Citation2015), regional greenbelts require institutional reforms and new policy developments to effectively manage the institutional complexity and governance challenges facing new-generation greenbelts.

In an era of global suburbanization and climate change, policy-makers must make decisions about how to best govern urban regions in today’s new urban world. Greenbelts are increasingly important for planning regional futures, as, for example, the GGH greenbelt builds resiliency against environmental threats by providing ecosystem services (Green Analytics, Citation2016). The Ontario and Frankfurt cases add a new chapter to greenbelt debates, illustrating that new-generation greenbelts require different institutional structures than their traditional predecessors did to enable their effective governance. Thus, the institutional arrangements supporting regional greenbelts need to be updated to reflect the current complexity of urban regions, so that these greenspaces can be better governed to continue providing the valuable environmental assets needed by urban regions.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (14.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the editors, anonymous reviewers, Roger Keil, Jörg Dettmar, Douglas Young, Valentin Meilinger, Michael Collens and Rebeca Dios for valuable feedback on earlier drafts of this paper. An early version of the paper was presented at a Regional Studies Association (RSA) conference (Spain, 2019) and the authors thank the session participants for helpful comments. Finally, the authors thank the numerous interview partners for their support, as well as Maximilian Hellriegel for assistance with research for the Frankfurt case.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. For the interviewees, see Appendix A in the supplemental data online.

2. distinguishes between three types of greenbelts that are characteristic for a specific period. However, these are ideal types and traditional or modernist greenbelts could be developed today.

3. Within institutionalism, a distinction is made between formal and informal institutions. Formal institutions include constitutions, laws and regulations, while informal institutions include traditions and conventions (Hall & Taylor, Citation1996).

4. For similar analytical categories, see Röhring and Gailing (Citation2005) and Young (Citation2002).

5. The Planning Act requires that municipal plans be consistent with the Provincial Policy Statement and plans issued under it, including the Greenbelt Plan. It also requires municipalities to update their official plans to conform with provincial plans according to sections 3.5 and 26.1 of the Planning Act (Citation1990). The Minister of Municipal Affairs and Housing can remove the approval powers of any delegated municipalities due to contraventions of those policies according to section 4.5 of the Planning Act.

6. A regional government refers to a formal level of government situated between the GGH’s single-, lower and upper tier municipalities and the provincial government.

7. The greenbelt’s popular support showed in the broad rejection that now Premier Doug Ford experienced during the 2018 provincial election campaign concerning his proposed plans to soften the land-use controls put in place by the greenbelt legislation (Gray, Citation2018).

REFERENCES

- Addie, J. P., & Keil, R. (2015). Real existing regionalism: The region between talk, territory and technology. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 39(2), 407–417. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12179

- Allen, R., & Campsie, P. (2013). Implementing the growth plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Has the strategic regional vision been compromised? Neptis Foundation. http://www.neptis.org/publications/implementing-growth-plan-greater-golden-horseshoe

- Allmendinger, P., & Haughton, G. (2009). Soft spaces, fuzzy boundaries, and metagovernance: The new spatial planning in the Thames Gateway. Environment and Planning A, 41(3), 617–633. https://doi.org/10.1068/a40208

- Amati, M. (ed.). (2008). Urban green belts in the twenty-first century. Ashgate.

- Amati, M., & Taylor, L. (2010). From green belts to green infrastructure. Planning Practice and Research, 25(2), 143–155. https://doi.org/10.1080/02697451003740122

- Burchfield, M. (2016). Province must embrace its role as regional planner for Growth Plan to succeed. Neptis Foundation. http://www.neptis.org/latest/news/province-must-embrace-its-role-regional-planner-growth-plan-succeed

- Cadieux, K. V., Taylor, L. E., & Bunce, M. F. (2013). Landscape ideology in the Greater Golden Horseshoe Greenbelt Plan: Negotiating material landscapes and abstract ideals in the city’s countryside. Journal of Rural Studies, 32, 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2013.07.005

- Campaign Fairness Ontario. (2016). If it’s broke, fix it. A report on the money in municipal campaign finances of 2014. Campaign Fairness Ontario.

- Carter-Whitney, M. (2010). Ontario’s greenbelt in an international context. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. https://www.greenbelt.ca/ontario_s_greenbelt_in_an_international_context2010.

- Côté, A., & Fenn, M. (2014). Provincial–municipal relations in Ontario: Approaching an inflection point. Institute on Municipal Finance and Governance. https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/imfg/uploads/275/1560_imfg_no_17_online_full_colour.pdf

- Dettmar, J. (2012). Weiterentwicklung des Regionalparks RheinMain. In J. Monstadt, B. Schönig, K. Zimmermann, & T. Robischon (Eds.), Die diskutierte Region: Probleme und Planungsansätze der Metropolregion Rhein-Main (pp. 231–254). Campus.

- Filion, P., & McSpurren, K. (2007). Smart growth and development reality: The difficult co-ordination of land use and transport objectives. Urban Studies, 44(3), 501–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/00420980601176055

- Freestone, R. (2002). Greenbelts in city and regional planning. In K. Parsons, & D. Schuyler (Eds.), From garden city to green city: The legacy of Ebenezer Howard (pp. 67–98). Johns Hopkins.

- Frisken, F. (2001). The Toronto story: Sober reflections on fifty years of experiments with regional governance. Journal of Urban Affairs, 23(5), 513–541. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2166.00104

- Gailing, L. (2007). Regional parks: Development strategies and intermunicipal cooperation for the urban landscape. German Journal of Urban Studies, 46(1), 68–84.

- Glass, M. (2018). Navigating the regionalism–public choice divide in regional studies. Regional Studies, 52(8), 1150–1161. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1415430

- Gray, J. (2018, May 1). Doug Ford recants vow to allow Greenbelt development. The Globe and Mail. https://www.theglobeandmail.com/canada/toronto/article-doug-ford-recants-vow-to-allow-greenbelt-development/.

- Green Analytics. (2016). Ontario’s good fortune: Appreciating the greenbelt’s natural capital. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. https://d3n8a8pro7vhmx.cloudfront.net/greenbelt/pages/2825/attachments/original/1485878510/OP_20_Web_version_2017.pdf?1485878510

- Hall, P. (2007). Rethinking the mark three green belt. Town and Country Planning, 76(8), 229–231.

- Hall, P. A., & Taylor, R. C. (1996). Political science and the three new institutionalisms. Political Studies, 44(5), 936–957. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9248.1996.tb00343.x

- Hamel, P., & Keil, R. (eds.). (2015). Suburban governance: A global view. University of Toronto Press.

- Han, A. T., & Go, M. H. (2019). Explaining the national variation of land use: A cross-national analysis of greenbelt policy in five countries. Land Use Policy, 81, 644–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2018.11.035

- Hertel, S., & Markovich, J. (2015). Local leadership matters: Ontario municipalities taking action to strengthen the greenbelt. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. https://www.greenbelt.ca/local_leadership_matters_greenbelt2015

- Hoyler, M., Freytag, T., & Mager, C. (2006). Advantageous fragmentation? Reimagining metropolitan governance and spatial planning in Rhine-Main. Built Environment, 32(2), 124–136. https://doi.org/10.2148/benv.32.2.124

- Jessop, B. (2000). The crisis of the national spatio-temporal fix and the tendential ecological dominance of globalizing capitalism. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 24(2), 323–360. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00251

- Keil, R., Hamel, P., Boudreau, J. A., & Kipfer, S. (2017). Governing cities through regions: Canadian and European perspectives. Wilfrid Laurier University Press.

- Krause, R. (2014). Placemaking in the RhineMain Regionalpark [Master’s thesis]. Blekinge Institute of Technology. Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.se/smash/get/diva2:832027/FULLTEXT01.pdf

- Lennon, M. (2015). Green infrastructure and planning policy: A critical assessment. Local Environment, 20(8), 957–980. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549839.2014.880411

- Lowndes, V. (2010). The institutional approach. In D. March, & G. Stoker (Eds.), Theory and methods in political science (3rd Ed.) (pp. 67–98). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lucas, J. (2013). Hidden in plain view: Local agencies, boards, and commissions in Canada (IMFG Perspectives No. 4). Retrieved from https://munkschool.utoronto.ca/imfg/uploads/253/imfg_1453hiddeninplainview_final_web.pdf

- Macdonald, S., & Keil, R. (2012). The Ontario Greenbelt: Shifting the scales of the sustainability fix? Professional Geographer, 64(1), 125–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330124.2011.586874

- Mace, A. (2018). The metropolitan green belt, changing an institution. Progress in Planning, 121, 1–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.progress.2017.01.001

- March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (2011). Elaborating the ‘new institutionalism’. In R. Goodin (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of political science (pp. 159–175). Oxford University Press.

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs. (2017). Greenbelt plan, 2017. Retrieved from http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/Page13783.aspx

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. (2015). Performance indicators for the Greenbelt Plan. Part 1, 2015. Retrieved from http://www.mah.gov.on.ca/AssetFactory.aspx?did=10850

- Ministry of Municipal Affairs and Housing. (2019). Growth Plan for the Greater Golden Horseshoe, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.placestogrow.ca/index.php?option=com_content&task=view&id=9&Itemid=14

- Monstadt, J., & Meilinger, V. (2020). Governing suburbia through regionalized land-use planning? Experiences from the Greater Frankfurt Region. Land Use Policy, 91, 104300. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landusepol.2019.104300

- Nelles, J. (2012). Comparative metropolitan policy: Governing beyond local boundaries in the imagined metropolis. Routledge.

- Paasi, A., & Metzger, J. (2017). Foregrounding the region. Regional Studies, 51(1), 19–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1239818

- Peters, B. G. (2019). Institutional theory in political science: The new institutionalism (4th Ed.). Edward Elgar.

- Phelps, N., & Wu, F. (eds.). (2011). International perspectives on suburbanization: A post-suburban world? Palgrave Macmillan.

- Planning Act. (1990). (ON). s.3.5, 4.5, 26.1 (CA). Retrieved from https://www.ontario.ca/laws/statute/90p13

- Pond, D. (2009). Institutions, political economy and land-use policy: Greenbelt politics in Ontario. Environmental Politics, 18(2), 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644010802682619

- Rautenstrauch, L. (2015). Regionalpark RheinMain – Die Geschichte einer Verführung. Regionalpark RheinMain Ballungsraum GmbH. Societaets.

- Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain. (2010). Regionalplan Südhessen/Regionaler Flächennutzungsplan, Allgemeiner Textteil of October 17, 2010.

- Regionalverband FrankfurtRheinMain. (2018). Regionales Monitoring 2018. Daten und Fakten – Metropolregion FrankfurtRheinMain.

- Robinson, J. (2011). Cities in a world of cities: The comparative gesture. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00982.x

- Röhring, A., & Gailing, L. (2005). Institutional problems and management aspects of shared cultural landscapes. Leibniz Institute for Regional Development and Structural Planning (IRS), Erkner.

- Schmidt, S., Siedentop, S., & Fina, S. (2018). How effective are regions in determining urban spatial patterns? Evidence from Germany. Journal of Urban Affairs, 40(5), 639–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/07352166.2017.1360741

- Siedentop, S., Fina, S., & Krehl, A. (2016). Greenbelts in Germany's regional plans – An effective growth management policy? Landscape and Urban Planning, 145, 71–82.

- Sieverts, T. (2003). Cities without cities: An interpretation of the Zwischenstadt. Routledge.

- Stoker, G. (1998). Governance as theory: Five propositions. International Social Science Journal, 50(155), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2451.00106

- Sturzaker, J., & Mell, I. (2017). Green belts: Past; present; future?. Routledge.

- Taylor, L. (2019a). The future of green belts. In M. Scott, N. Galant, & M. Gkartzios (Eds.), Routledge companion to rural planning (pp. 458–468). Routledge.

- Taylor, Z. (2019b). Shaping the metropolis: Institutions and urbanization in the United States and Canada. McGill-Queen’s Press.

- Tomalty, R. (2015). Farmland at risk: How better land use planning could help ensure a healthy future for agriculture in the Greater Golden Horseshoe. Ontario Federation of Agriculture and Environmental Defense. Retrieved from https://environmentaldefence.ca/2015/11/24/ontario-farmland-at-risk-better-land-use-planning-can-help-save-the-family-farm/

- Tomalty, R., & Komorowski, B. (2011). Inside and out: Sustaining Ontario’s greenbelt. Friends of the Greenbelt Foundation. Retrieved from http://www.greenbelt.ca/inside_and_out_sustaining_ontario_s_greenbelt2011

- Willi, Y., Pütz, M., & Müller, M. (2018). Towards a versatile and multidimensional framework to analyse regional governance. Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 36(5), 775–795. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654418760859

- Young, O. (2002). The institutional dimensions of environmental change: Fit, interplay, and scale. MIT Press.