ABSTRACT

Agency-based approaches represent a fundamental advance in how researchers and policymakers can address questions of place-based industrial strategy, including issues of governance, leadership, new technology and regional assets. However, these approaches can be advanced further by recognizing the centrality of discourse in regional change. This paper does this by synthesizing two conceptual frameworks: Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s trinity of change agency and Moulaert et al.’s framework of Agency Structure Institutions Discourse (ASID). Deploying two Australian case studies to shed light on drivers of change at the local scale, this paper demonstrates that discourse is a necessary component of transformative regional processes. Furthermore, it contends that successful transformation is presupposed by the extent to which local discourse overlaps with local opportunity spaces and forms of agency. Successful place-based industrial strategies need to mobilize these multiple elements of regional change in order to maximize their potential for success.

JEL:

INTRODUCTION

Globally, regions and industries have been threatened by disruption, including shocks associated with the rise of leading-edge technologies, international competition and the economic crisis generated by the Covid-19 pandemic. The latter threatens to worsen the consequences of uneven development, with too many regions ‘left behind’ and struggling to manage problems of industrial or demographic decline (Reckien & Martinez-Fernandez, Citation2011; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018). Such events threaten regions with new ‘critical junctures’, or moments which portend adverse transformations (Grillitsch & Sotarauta, Citation2020). The challenges of policy have been reflected in increased academic attention to the need for local industrial strategies (Bailey et al., Citation2019; Nurse & Sykes, Citation2020). Researchers have argued these strategies can be a catalyst for better regional futures through a focus on the creation and local capture of value. Specific actions include the diagnosis of current and future competitive advantages; the identification of key ‘vehicles’ for growth such as multinational firms as ‘anchor’ tenants; establishing a branding strategy; developing a niche within global production networks; and focusing on small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) to ensure a fair distribution of the benefits arising from policy intervention (Bailey et al., Citation2018; Beer et al., Citation2020). These policies seek to address ‘systematic and market failures … to create an environment (or stable/seedbed) from which “winners” may arise’ (Bailey et al., Citation2019b, p. 177).

However, evidence to date has been suggestive rather than definitive. The conditions that allow place-based industrial strategies to be successful are not fully understood (Miörner, Citation2020; Oinas et al., Citation2018). Questions remain about the dependence of new, more prosperous, economic trajectories on the adoption of emerging technologies (Bailey et al., Citation2018), the quality of local governance (Charron et al., Citation2014; Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013), the intrinsic resources of the region including human capital; and the capacities of local leadership (Sotarauta, Citation2018). Growth also needs to be inclusive, and Lee (Citation2019) has discussed how this concept draws attention to distributional outcomes and the broader intent of development.

This paper has three goals. First, it looks to advance recent contributions on the role of agency amongst local and regional actors attempting to influence economic pathways. While there is substantial scholarship on the preconditions and dynamics that favour path reconfiguration (Henning et al., Citation2013; Miörner, Citation2020), path transformation (MacKinnon et al., Citation2009; MacKinnon et al., Citation2019; Steen, Citation2016) and the emergence of new pathways post-transition (Binz & Gong, Citation2021), these perspectives are disparate and often contested (Boschma et al., Citation2017; Hassink et al., Citation2019; Isaksen et al., Citation2018). In attempting to advance debate about agency, this paper sheds light on the moments and processes of change that result in a city or region either carving out a new development trajectory, or failing to transform – risking slower growth or decline (Isaksen et al., Citation2018). The paper advances the literature by strengthening our understanding of the role of discourse in shaping the vision or set of expectations for a region (Steen, Citation2016), thereby enabling the creation of new paths. These narratives of change enable the mobilization of resources towards a specific path.

The paper explores this question of path realization or regional agility (Sorensen et al., Citation2018) conceptually and empirically by seeking to draw together two distinct, but complementary, explanations of regional dynamics: the Agency, Structure, Institutions and Discourse (ASID) framework of Moulaert et al. (Citation2016), on the one hand, and Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) ‘trinity’ of change agency, on the other. In integrating these approaches, we emphasize that the discourse of local actors constructs an interpretive framework which enables actors to reinterpret the past, spurring local leaders to respond to moments of potential crisis. Third, the paper sets out to better understand the contribution these perspectives on path creation and path adjustment make to the advancement of place-based industry policy.

To highlight the role of discourse and its interaction with the structural conditions surrounding regions and their development, the paper draws evidence from two Australian case studies: the city of Whyalla in South Australia and south-eastern Melbourne, Victoria. These examples shed light on the role of discourse as one of the drivers of place-based industrial change and the part played by local strategy in facilitating transformation. We establish a framework for understanding the processes that enable regions, cities and communities to establish a new economic trajectory (Hassink et al., Citation2019), and the contribution place-based industrial strategy can make to that rejuvenation.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. It briefly reiterates the significance of an agency-led approach to regional transformation and explains the facilitative role discourse can play. The paper outlines a comparative methodology that focuses on the role of discourse and agency in transforming places with radically different characteristics. It examines the way economic change has been enacted in the steel-making city of Whyalla, while it then focuses on the response of south-east Melbourne to the demise of automotive manufacturing in Australia. The final substantive section discusses the findings and their implications for our knowledge of regional processes and place-based industry policy.

FRAMING REGIONAL CHANGE: DISCOURSE AS A COMPLEMENT TO AGENCY AND OPPORTUNITY SPACE

Several bodies of literature have provided insights into the causative processes behind regional economic growth or decline. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020, p. 2) note two dominant theoretical traditions that address questions of path development: Evolutionary Economic Geography (EEG) and institutional theory.

EEG is a theoretical framework, an approach to the analysis of economic geography that highlights the importance of dynamic approaches, path dependency and ongoing learning in the evolution of regions. It comprehends the development of a regional industrial path as a process (Martin, Citation2020). As Boschma and Martin (Citation2007, p. 536) argue, evolutionary theories of path development are ‘dynamical’, deal with ‘irreversible processes’ and ‘cover the generation and impact of novelty as the ultimate source of self-transformation’.Footnote1 In their work on the stages of regional industrial path transformation, Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. (Citation2021, p. 2) acknowledge the centrality of innovation and adaptation which they interpret as pathway-shaping, place-dependent phenomena. In this framework, ‘assets, skills, and competencies developed in the past’ influence ‘past, present and future choices’. Historically derived, local structures shape the possibilities available to regions (Martin & Sunley, Citation2006). In common with Martin (Citation2010), Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. (Citation2021) recognize a duality at the core of regional evolution, with both gradual and disruptive change possible, though steady adaptation is considered the norm and emerges as latent potential is valorized (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. (Citation2021) noted critiques of EEG-based explanations, especially their silence on the role of agents other than firms. These alternative actors include potentially powerful forces including institutions such as universities (Njøs et al., Citation2020). Moreover, EEG provides few insights into how planning for the future reshapes local industry and awards little priority to the purposive action of governments or communities (Hassink et al., Citation2019).

Other researchers have examined how multiple new paths may emerge in a single region (Frangenheim et al., Citation2020) or the ways in which EEG can be integrated with global production network approaches (MacKinnon et al., Citation2019). Boschma et al. (Citation2017) drew on the transition studies literature but located their highly influential work on related and unrelated diversification within EEG. Researchers have also considered the role of purposeful strategy, as well as bricolage – improvization – in the development of new trajectories (Boschma et al., Citation2017; Garud & Karnøe, Citation2003). Binz and Gong (Citation2021) examined the legitimation dynamics associated with industrial path development, while Miörner (Citation2020, p. 4) focused on how existing conditions ‘selectively reinforce some forms of action and dampen others’. Drawing upon the sociology of expectations, Steen (Citation2016) highlighted the roles of intentionality and choice in the development of new technologies and industries, as well as the ‘sense of collective expectation’ (p. 1611) that drives strategy formation and change. Henning et al. (Citation2013) observed the rapid growth in research articles focused on questions of path dependence but noted significant gaps in the literature. These included difficulties in operationalizing the concept empirically; too strong a focus on understanding a single path in a single region; and the failure to shed light on the development trajectories not followed.

EEG-based explanations of regional growth argue previous events determine likely future outcomes. As Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) observe, this makes for a relatively rigid set of pathways that cannot be redirected easily. Evolutionary perspectives shed little light on micro-level processes, that is, the detail of how and where decisions were taken at the regional scale, or where events unfolded to create a new future.

The second main theoretical tradition of institutional theory follows the work of North (Citation1990) and Amin (Citation1999) and acknowledges that ‘some regions grow significantly more than could be expected, given their preconditions, while the opposite is true for other regions’ (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013, p. 1036; Streeck & Thelen, Citation2005). Much of the focus is upon regions achieving the ‘right’ mix of institutions to thrive (Safford, Citation2004) or in having appropriate institutions for the needs of the region (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2013). Institutional perspectives are open to the prospect of disruptive change. Streeck and Thelen (Citation2005, p. 31) have noted that processes of displacement, layering, drift, conversion and exhaustion alter long-established pathways and usher in fundamental change. As well as pointing to insufficient clarity about the configuration of institutional structures that best ‘fits’ individual regions, Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) argue that institutional approaches offer:

a dearth of knowledge about what actors do to create and exploit opportunities … and why the effects of such efforts differ between apparently similar places … the blind spot is the role of agency and its relationship to structure.

Grillitsch and Sotarauta identify three types of change agency: innovative entrepreneurship which serves as the path-breaking trigger for innovations that generate new economic opportunities; institutional entrepreneurship where key actors seek to change institutions and challenge the status quo; and place-based leadership where groups work together to combine competencies and resources (Sotarauta, Citation2016, Citation2018). Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) also identify three types of opportunity space which shape and constrain possible options for regional and local actors: time specific – what is possible given the current stock of global knowledge, institutions and resources; region specific – reflecting regional preconditions; and agent specific – the differentiated opportunities and capacities of individual agents to bring about change.

This combination of agency and opportunity space forms a ‘trinity’ of change potential that works at a microlevel to reshape development pathways. This observation resonates with Hassink et al.’s (Citation2019) contention that new industrial pathways can potentially emerge from diverse actors. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) argue the capacity to reconfigure local economic conditions resides in multiple sources of change, including the private sector, public institutions and government agencies, and communities. Importantly, they differentiate their analytical framework from others by focusing on concrete processes shaping regional outcomes. They argue that too much conceptualization has taken place at an abstract level, making the translation from theory to practice difficult. Theirs is a bottom-up perspective which emphasizes the need to embrace the messy complex of factors reshaping regions and the ways in which actors make sense of change. As they argue:

empirical studies should not only aim at describing how regional paths evolve but also at unveiling to what extent, why and how a multitude of actors shaped this evolution … empirical studies need to zoom in also on the ‘subjective’ stories of individuals, and grasp their perceptions, intentions and change strategies.

Moulaert et al. offer a broad, meta-theoretical framework known as Agency, Structure, Institutions, Discourse (ASID) that transcends a simple categorization into either an institutional or evolutionary perspective, with the authors acknowledging the integration of several established theories. As they argued:

For an adequate account of socio-economic development processes one must refer to the actions that steer or influence development processes, the structures that both constrain and enable action, the institutions that guide or hamper actions and mediate the relation between structures and action, and the discourses and discursive practices that are part of these agencies.

To begin with, the two approaches have mutually cognisant understandings of agency. Moulaert et al. (Citation2016, p. 169) frame agency as ‘meaningful human behaviour’, with a focus on actions with strategic intent; for instance, the creation or adaptation of institutions and discourses. Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) have a similar view of agency, which is framed at a very broad level, at the more precise scale of regional pathways: ‘a regional growth path can hence be seen as the nexus of intentional, purposive and meaningful actions of many actors, and the intended and unintended consequences of these actions’ (p. 4).

Similarly, Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s notion of opportunity space resonates with Moulaert et al.’s (Citation2016) heuristic deployment of structure and institutions. Structure is defined by the latter as a very broad category which limits the power of agents in ‘the short-to-medium run’ – that is, it determines what actors cannot do – whereas institutions are understood as ‘socialised structures’ which comprise ‘more or less coherent, interconnected [sets] of routines, organizational practices, conventions, rules, sanctioning mechanisms, and practices … ’ (Moulaert et al., Citation2016, p. 169). Just as Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) specify agency in a precise way, they also deploy the constraining influences of structure and institutions within their concept of opportunity space, which is present in a city or region at a defined point in time. Opportunity space acknowledges what is possible with respect to prevailing social and economic structures and institutions, established regional conditions, the global stock of knowledge and technology, and the capability of local actors. The concept forces researchers to consider the realm of possibilities available to a region and how those opportunities are shaped by history, infrastructure, natural assets, national and global economic conditions.

Grillitsch and Sotarauta make little explicit reference to discourse. This is a notable point of difference with Moulaert et al. (Citation2016, p. 167), for whom agency itself is seen to be ‘discursively and materially reproduced and transformed’. Discourse is taken to be ‘the production of intersubjective sense or meaning-making. It is an essential moment of action (as meaningful behaviour)’ (p. 169).

We argue the incorporation of discourse into Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) trinity of change offers a significant advance in agency-based approaches to regional change. The argument place-based change is made possible by how meaning is constructed resonates with the substantial body of work on transformational place leadership (Collinge & Gibney, Citation2010), and the role of place leaders in developing and communicating a common understanding of future possibilities. It is consistent with the priority afforded to regional plans or ‘visions’ by Baumgartinger-Seiringer et al. (Citation2021) and Steen (Citation2016), where such future-focused statements constitute a form of discourse. There is also congruence with scholarship emphasizing ‘joint expectations’ and ‘conventions’ amongst private firms and public institutions as a basis for collaborative action (Hassink et al., Citation2019). A further advantage is Moulaert et al.’s (Citation2016, p. 175) acknowledgment of discourse as an iterative process. They noted the ASID framework:

adopts an evolutionary perspective to examine the variation, selection and retention of specific discourses and therefore highlights the semiotic factors that makes some discourses more resonant than others, more likely to be selected as the basis for strategic action and policy making, and more likely to be institutionalised.

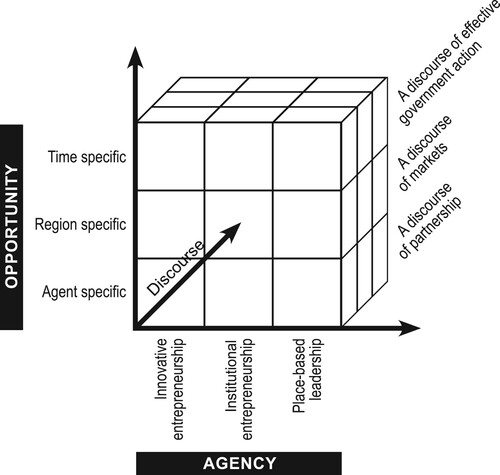

In our analysis, the inclusion of discourse adds a third axis of change to Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) framework. adds the dimension of discourse which interacts with various forms of agency and dimensions of opportunity space. Different combinations of agency and opportunity space interact with different types of discourse to produce the complex outcomes we witness around the globe. Depending upon conditions in each place and at each moment of time, different discourses emphasize either the relative importance of the state (discourse of effective government action), private business (discourse of markets) or partnerships that span industry, governments and the community (discourse of partnership).

The explicit recognition of discourse as a process and driver of change at critical junctures enhances the model developed by Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020). In earlier work, Sotarauta (Citation2016, p. 73) observed that interpretive power – alongside network power – was one of the most important forms of influence available to place leaders. Interpretive power includes the encouragement of other actors through writings and presentations; the representations of alternative futures and the promotion of the region; influencing others by bringing forth new knowledge; and affecting public sentiment via the media. Dinmore and Beer (Citation2021) have further extended this argument, drawing attention to the narrative devices deployed by leaders and how they reshape the perspectives of individuals and communities.

The remainder of this paper seeks to test this framework empirically through its application to the comparison of two regions which needed to respond urgently to industrial transformation. In both instances we apply the conceptual framework developed above and presented graphically in . It serves as a set of organizing principles driving the examination of change, and the part played by context, agents and discourses in justifying, and making sense of, new path creation. As the case studies suggest, not all dimensions of agency, opportunity space and discourse are significant in each instance. However, each is latent – a potential driver of transformation if the appropriate conditions arise. For example, place leadership may be critical where institutional agency or entrepreneurial agency is underdeveloped (Beer, Citation2014), while a discourse of partnership may be necessary if governments or the private sector are unwilling to act alone.

METHODOLOGY

This paper compares two urban areas in Australia. Australian cities exhibit different economic profiles to European or North American cities because of their relative isolation from global production networks and the comparatively weak fiscal role of municipal government. In Australia’s federal system, policymaking at the federal and state level is dominant.

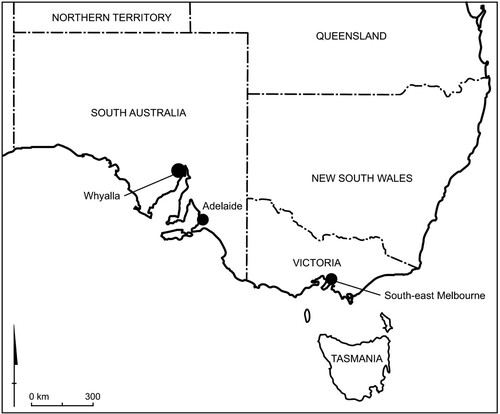

To draw out the impact of local agency and discourse, as well as the opportunity spaces evident in each region, we selected regions which experienced comparable outcomes despite their very different circumstances: south-east Melbourne and Whyalla (). South-east Melbourne is one of the most densely populated and economically important centres within Australia’s second largest metropolis, whereas Whyalla is a small, and relatively remote, city on South Australia’s coast. Actors in both regions were confronted by a critical juncture in their economies: In south-east Melbourne, the winding down and demise of automotive manufacturing and, in Whyalla, a crisis in steel making. As we demonstrate, diverse interventions have made possible new futures.

Our approach draws upon the comparison of ‘most different’ cases with a ‘similar outcome’ (or MDSO), a methodology devised originally from Mill’s (Citation1843) ‘indirect method of difference’. This research deploys a paired case design in which many characteristics, such as population size, economic output, industry profile and geographical isolation, differ but where at least one common causal mechanism – an urgent and concerted response to industrial transformation – can be identified (Berg-Schlosser & De Meur, Citation2009; Rihoux, Citation2006).

In comparing these case studies, the research deploys the model developed above (cf. ). This means focusing first on the transformation of opportunity spaces in each location; second, on local change agency; and third, the shifts in discourse among local leaders which empowered and provided a context for the development of agency. In each place, we deployed semi-structured interviews based on a list of up to 12 questions designed to elicit responses around the opportunity spaces evident when the city was confronted by crisis. We examined the types of agency evident during that process of change and the narratives used by leaders to make sense of transformative action.

Four in-depth interviews were undertaken in Whyalla and seven in south-east Melbourne, with interviewees including business leaders, the media, local government officers and elected officials. Interviews were recorded, transcribed and analysed to draw out key themes with open coding (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1998). Axial coding was then used to cross match themes with our core research questions about agency and discourse in response to critical junctures. Our analysis uncovered a shift in narrative among interview participants which emerged as responses to local crises evolved. Where necessary, participant identities have been anonymised.

ECONOMIC TRANSITION AND INDUSTRY IN WHYALLA

Opportunity space

Whyalla is a small city in South Australia located on the Eyre Peninsula near the head of the Spencer Gulf, 237 km from Adelaide (). It remains on the periphery of the Australian economy, surrounded by desert and located on the traditional lands of the Barngala people. The population has declined for decades, from a peak in the mid-1970s of 33,000 to 20,114 at the 2016 Census.

Whyalla was born as an industrial town. It was established in 1901 (as Hummock Hill) as a shipping port for iron ore from the mine at nearby Iron Knob, part of the Middleback Range. Broken Hill Pty Ltd (BHP) opened a blast furnace for the production of iron and steel in 1941 and also began building ships for the Royal Australian Navy. In 1944 a water pipeline was completed, removing a major constraint on industrial development and population growth. By 1968, BHP had opened an integrated steel works. During this period the population grew by 3000 annually, many of whom were migrants from Europe. BHP’s workforce in steel production and shipbuilding reached nearly 7000 by 1970. The shipyards closed in 1978, a critical juncture which brought several decades of remarkable growth to an end. Since then, the city has experienced several more critical junctures as steel production has continued to decline. The most recent shock occurred in 2016 when the Whyalla Steelworks – which BHP had transferred to a spin-off company, OneSteel (later renamed Arrium) in 2000 – went into administration in the face of mounting debts. The steelworks, which had remained the centrepiece of the city economy, had come under increased pressure after 2008 because of greater competition from lower cost competitors in Asia, weak demand after the global recession of 2008/09 and the challenges of operating a relatively small steelworks using out-of-date technology. By the time the steelworks confronted bankruptcy in 2016 the opportunity space for local actors was severely constrained by decades of deindustrialization, exposing the city’s dependence on steel production and compounding the risks of its geographical isolation from key nodes in global production networks. Its circumstances were worsened further by the fiscal weakness of local governments in Australia’s federal system.

Agency

The responses of the Whyalla City Council to these critical junctures, including the 2016 events, were constrained by the city’s limited resources. Lacking a strong revenue base, it was unable to act decisively and was forced to rely on support from the South Australian and Australian governments. In the 1990s the city sought to improve Whyalla’s liveability and attractiveness to investors and potential investors, directing Australian government-provided funds to beautify the foreshore and improve overall amenity. But such investments could not reverse the overall trend of decline, which continued into the 2000s. Furthermore, the small pool of SMEs in the region remained dependent on the steelworks and were unable to overcome economic challenges without external assistance.

Economic crisis in 2016 was transformed by the intervention of an external multinational with an expansive global production network. In 2017, Whyalla’s steelworks were bought by the British-based industrialist Sanjeev Gupta, through his company Liberty Steel. This purchase heralded a programme to transform the city. Gupta separated the steel making and mining activities previously undertaken by Arrium, with Liberty Steel undertaking the former and a separate company, SIMEC, the latter, with the two coming together under the banner of the GFG Alliance. Gupta also purchased a majority shareholding in a local firm – Zen Energy – as a vehicle for securing renewable energy into his businesses.

Gupta’s purchase of the Whyalla operations and the associated plans for reinvestment attracted considerable media attention. This was heightened by high-profile events featuring the Australian Prime Minister, the South Australian Premier, Gupta and executives from European and other companies. Shortly after taking control, parent company, Liberty House, announced plans that included a A$600 million upgrade of steel making facilities to boost annual production to 1.8 million tonnes per annum and advance investment in renewable energy, including a 280 MW solar farm and substantial battery storage. These interventions had a transformative impact on local views about the economic viability of the city. However, these perspectives were cognisant of the city’s ongoing dependence on external forces – in this case, the core agency of Liberty Steel and its global production network. The possibility for generating new types of local agency were framed by the development of a dominant discourse about Whyalla’s place in global and national political economies.

Discourse

Industrial and demographic decline have become part of Whyalla’s development narrative since the 1970s (Beer & Keane, Citation2000). But the discourse that emerged in response to the 2016 critical juncture among local government and business leaders can be divided into two periods. The first brief period, which came in the immediate aftermath of Liberty’s purchase of the Whyalla Steelworks in 2017, was characterized by a strong discourse of private sector action rejuvenating Whyalla’s economy where earlier public sector programmes had failed. The view was that prior government neglect had failed to provide Whyalla with direct benefits from Australia’s mineral resource boom in the 2000s, including minimal benefits from BHP’s expansion of its copper/gold/uranium mine at Olympic Dam, some 400 km to the north-east, or the anticipated development of mines in the Gawler Craton to Whyalla’s north and west.

Whyalla’s integration into Gupta’s global production network was initially framed as a substantial local opportunity. Two years after buying the Whyalla facility, Gupta purchased a further seven steel plants in Europe, with facilities located in Macedonia, Romania, Italy and the Czech Republic. This acquisition made Liberty Steel–GFG Alliance the third largest steel producer in Europe, with the Whyalla plant potentially benefitting from the marketing, technological development and industry linkages of this global enterprise. The new renewable energy programme was framed locally as the ‘ultimate liberator for Australian industry’ (Puddy, Citation2018), breaking the reliance on fossil fuels and providing low-cost electricity for the foreseeable future. This vision of a new and resurgent Whyalla was to be supported by new, local investment in tourism and hospitality, as well as modest government grants, parallel Chinese investment in horticulture, and the development of a new recycling business. Government press announcements underscored the depth and breadth of this transformation by forecasting growth of Whyalla’s population to 70,000 within 15 years, while the prime minister labelled Whyalla the nation’s ‘comeback city’ (Fedorowytsch & Keane, Citation2018).

The second phase of this discourse, which emerged over the two years following Gupta’s initial buyout, was a story of Whyalla as a work in progress with mixed perspectives on the likelihood of success. For some, the injection of additional investment and the embrace of renewable technologies was a chance to capitalize on the emergence of cost-effective clean energy production (as a time-specific opportunity), ready access to high-grade iron ore (as a region-specific opportunity), and the potential created through integration into a global manufacturing enterprise (an agent specific opportunity). As one entrepreneur working in the renewable energy sector commented:

I think Whyalla as a community has an exciting future. … But it’s not just the steelworks – it’s everything else … rather than digging up and exporting the raw product we’ll be able to value add to all these things now which will be a huge benefit.

It won’t enable change by itself – the actual resource and low-cost energy will enable the change – but it [Gupta’s leadership] offers benefits and it will attract companies.

He’s done a lot of media. I guess it depends what your view is of him. I think everyone wants him to succeed but there are people who doubt him. This is sort of his bread and butter. This is what he does. He goes into places that are really struggling and he turns them around.

From my perspective … there has not been a lot of progression with the actual upgrade of the steelworks itself. … [The] steelworks are still in a bad spot. It’s still losing money. [Gupta is] still trying to turn that around … .

These reservations appear justified given requests by GFG Group for further financial assistance from the South Australian government (Marchant, Citation2020) and ongoing cost pressures within the enterprise (Siebert & Marchant, Citation2020). There is also a sense that the ‘opportunity space’ represented by Gupta’s involvement with Whyalla may be time limited: in mid-2020, GFG sold Zen Energy (Martin, Citation2020), the company it purchased to deliver renewable energy into its plant back to its original owners, while investing in a manganese alloy smelter in Tasmania (Champ, Citation2020). These actions suggest there is uncertainty around Gupta’s reinvestment in Whyalla’s steelmaking capacity. From 2016 to 2021, discussions around Whyalla and its future have been dominated by the perceived leadership and potential impact of a single private sector actor, with relatively small convergences between the discourse of leadership and the realization of opportunities. The small cohort of firms involved in regeneration and the limited investment by the Australian Government have made for a narrow channel for the emergence of a new Whyalla.

ECONOMIC TRANSITION AND INDUSTRY IN SOUTH-EAST MELBOURNE

Opportunity space

South-east Melbourne is one of Australia’s most populous urban areas with around 1.2 million residents and over 500,000 in paid work. It is one of Australia’s most important manufacturing centres. Over 100,000 people, or around 17% cent of people in paid work, are engaged in manufacturing, with most concentrated in Dandenong and adjacent suburbs (SEM, Citation2020). By comparison, only 7% of the labour force worked in manufacturing Australia-wide (Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), Citation2020).

Historically, manufacturing in south-east Melbourne has been focused on the automotive industry. In recent decades, Australia’s largest group of auto supply chain firms clustered in this area. By 2013, around 120 auto firms were based there. These ranged from multinational firms supplying car manufacturers directly, through to mid-sized firms, as well as smaller family-owned firms. However, this concentration has been challenged over time by the demise and eventual disappearance of domestic auto manufacturing. Conditions of trade liberalization, which began in the early 1980s, ultimately led to a succession of closures. In south-east Melbourne, Nissan closed its assembly plant in 1992 after 26 years of local production. General Motors Holden (GMH) closed its local assembly plant in 1996 after 40 years of production. In 2013 and 2014, Australia’s last three carmakers – Ford, Toyota and GMH – progressively announced their intention to close their remaining Australian assembly plants, generating a critical juncture for south-east Melbourne’s auto manufacturing suppliers.

Unlike Whyalla, no external industry leaders intervened to rescue south-east Melbourne from its dependence on auto manufacturing. There was no ‘saviour’ in the shape of a Sanjeev Gupta or similar. Instead, the region had to rely on prevailing regional assets. Transition was made possible by the combination of region-specific opportunities arising from being located at the core of the national economy; time-specific opportunities as firms were able to reposition in a period of steady – albeit modest – economic growth; and agent specific opportunities as central governments took advantage of their budgetary power to fund significant programmes.

Agency

The critical juncture represented by the automotive closure announcements in 2013–14 spurred local policymakers to take advantage of a range of programmes at the Federal and State Government level, including subsidies for supply chain firms and incentives to encourage diversification into manufacturing outside the auto industry. This urgency reflected initial fears that firm closures would significantly damage the area. Early studies anticipated 40,000–50,000 jobs would be lost nationwide due to the final closure (Productivity Commission, Citation2014). At least half the national total – around 25,000 job losses – was expected to occur in Victoria. Around 80% of these were expected in the supply chain, with most in south-east Melbourne.

Although fiscally much weaker than these higher tiers of government, the intervention of local government actors, alongside local business networks, enhanced the effectiveness of programmes set up and designed to assist smaller supply chain firms. Around 80% of local manufacturers employed fewer than 20 people and 90% employed fewer than 30 people. These firms commonly lacked the R&D capabilities, staffing or expertise needed to transition into new markets.

Local business networks facilitated knowledge transfer to hundreds of firms seeking support. This included the Committee for Dandenong which represented local firms across multiple industries; the South East Business Network (SEBN) which formed as a local manufacturing network in the early 1990s and later became incorporated within the structure of local government; and the South East Melbourne Manufacturing Alliance which represented over 200 manufacturing firms.

These interventions helped many businesses recover. A dozen companies that obtained direct assistance from local government were able to diversify into new areas, joining the majority of supply chain firms in the region which also survived. Most firms abandoned their auto industry origins to focus on business in aerospace, construction, mining, defence, railways or food processing. Several firms were also able to benefit from ongoing local manufacturing in trains and trams/streetcars (Bombardier), trucks (Iveco and Kenworth/Paccar), trailers (Vawdrey), caravans (Jayco), cranes (Altec) as well as major casting plants (Nissan and AW Bell).

Discourse

Two successive types of discourse emerged among leading local actors over the period from 2014 to 2018 in response to the looming closure of auto manufacturing. First, there was a strongly developed discourse of an impending jobs crisis which provided the foundation for urgent action. This narrative of crisis was dominant from immediately after the closure announcements in 2013–16.

This initial fear-driven narrative was reflected in interviews with local policymakers:

[What] we’re facing here in south-east Melbourne is very considerably higher unemployment and a pretty dismal future for the current workforce. … I am concerned for a workforce that’s in its 40s and 50s, with potentially 10–20 years productive work life left, who ought to be given a chance … .

[There is] nervousness, by and large … [and] a fair bit of anxiety. … Everyone can see [the closure of auto manufacturing] is looming. Everyone has great concerns … about what it all means for the future of industry and for workers.

[Some] companies … are having a terrible time. … They are in crisis-mode. … [The] councillors were very concerned. In March [2015], the councillors had heard figures of around 4000 job losses [projected for this area]. They wanted to do something.

We have always made companies aware of the federal and state assistance programs that are around. … [But when] we talked to the State [Government], we said that some of them aren’t in a position to take up this assistance. … To look at diversification requires levels of resources that these businesses just don’t have because they have to plough everything into maintaining the businesses that they’ve got. … Some companies need more of the hand-holding support that we’ve been able to [provide].

Manufacturing has a great future in this region. … [If] you look at the manufacturing precinct in Dandenong South, there are massive opportunities to diversify into other manufacturing areas. … [We] have quite a big transport manufacturing hub in Dandenong South where trains, trams, trucks and buses are made. You name it, if it’s on wheels or tracks, we make it. There’s a perceived crossover there where a lot of the skills coming out of auto [manufacturing] might be transferred to these other areas. But equally there’s a growing emphasis on advanced manufacturing. … Manufacturing is still seen in general as a good opportunity … .

DISCUSSION

One of the goals of this paper is to better understand the contribution emerging perspectives on path creation make to the advancement of place-based industry policy. Value-capture strategies which break down barriers to knowledge flows across, and through, business networks are a core issue if place-based industry policy is to generate benefits locally. Bailey et al. (Citation2018) have argued more effective information exchange can be achieved in several ways, including the introduction of ‘anchor tenants’ into regions. These are firms which are capable of sharing technology and thereby diffusing the benefits of engagement with the knowledge economy. Their presence generates externalities which raise local productivity. Anchor tenants, which can be private sector firms, including multinationals, or public institutions such as universities, perform an important bridging role within places.

More broadly, Bailey et al. (Citation2018) argued strategies need to balance actions that incentivise firm growth and innovation with those that maximize the local benefits of value creation. They suggest this regional ‘stickiness’ can be achieved through the creation of clusters, the co-location of activities and the building of regional ecosystems. Regions also need to identify their competitive advantages and establish ‘place renewing leadership’ (p. 11). Public agencies can assist in this endeavour by shaping economic development policies that are synchronized with broader structural change within the economy.

The successful implementation of place-based industrial policy seeks to implement a transition in regional economies. It represents one instance of the broader processes of path reshaping. Critically, this focus on economic transition redirects the analysis away from the articulation of the outcomes to be achieved (Bailey et al., Citation2018) to a focus on how positive change can be implemented. This article complements these claims with its focus on the roles of discourse, narrative and interpretive power in establishing goals and objectives locally. Its analytical focus on agency, opportunity space and discourse draws attention to the multiple and overlapping drivers of change at the scale of cities and regions and their intersection with industry. Importantly, the paper shows that the power of discourse to induce new path development is not a function of the extent of the crises; rather, it is a function of institutional strength, the number and types entrepreneurs involved, and the capacity to move into new opportunity spaces.

Both south-east Melbourne and Whyalla were confronted by critical junctures – the impact of the closure of the Australian car industry in the former case, and the potential collapse of steelmaking in the latter. Change was inevitable for both, but the nature, pace and direction of change was uncertain. The most critical drivers of transformation in south-east Melbourne were institutional support and leadership provided by SME-oriented business and government networks. In Whyalla, change was a product of the opportunities opened up by innovation in low-cost renewable energy and the arrival of an entrepreneurial investor with a global network.

In terms of opportunity space, south-east Melbourne’s time-specific opportunity found expression in the imperative to act expeditiously as automotive manufacturing closed and associated assistance programmes remained available. The area also possessed region-specific assets in the form of manufacturing nodes in tram, train and truck manufacturing. It also held significant human capital in the form of SME entrepreneurs and skilled employees. There were agent-specific opportunities generated by responsive and pragmatic policymakers. These advantages were magnified by the area’s proximity to the city of Melbourne as a centre of commercial and financial power. In Whyalla, a time-specific opportunity was generated by the emergence of renewable energy technologies that significantly reduced costs and could be implemented at scale. Whyalla also possessed region-specific assets in the form of mineral wealth and fixed assets in steel manufacturing. These overlapped with the agent-specific opportunity created by Gupta’s engagement with the city.

The agency of change differed significantly between Whyalla and south-east Melbourne. Given Sanjeev Gupta’s transformation of local steel manufacturing, innovative entrepreneurship was the central form of agency in Whyalla. In south-east Melbourne, by contrast, there was a combination of all three forms of entrepreneurship identified by Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020), including forward planning and diversification by SMEs (innovative entrepreneurship), significant resource mobilization and collaboration by federal, state and local governments (institutional entrepreneurship), and cooperation between governments and local business networks in enabling SMEs to access support (place-based leadership). Most of these features were not evident in Whyalla, which depended overwhelmingly upon the timely integration of local assets with an expanding global production network.

While there are clear differences between south-east Melbourne and Whyalla in terms of agency and opportunity space, the discourse of change was critical for both. This emphasizes the ways in which discourse is pivotal to understanding how cities and regions move to a new pathway, it also informs the implementation of place-based industry policy. In this research, discourse manifested itself as a sequence of narratives that shaped attitudes among local business leaders and policymakers. It exerted a powerful influence in providing an interpretative framework for crises of industrial transformation.

It is important to also recognize the intersections between agency, opportunity space and discourse. Change is not a matter of selecting one factor, such as the intervention of key leaders, the development of new markets or technologies, or the outcome of an enabling rhetoric but, rather, it is the product of a matrix of interactive factors, each of which has multiple dimensions. Positive outcomes are most likely to emerge where there is significant convergence between new opportunities, a commitment by key actors from across a number of sectors to mobilize change and a positive – and well informed – narrative on the process for achieving a better future ().

Table 1. Drivers of change in the economic pathways of south-east Melbourne and Whyalla.

In south-east Melbourne, the extent of this overlap was much greater than in Whyalla. This meant discourse could become more than simply an interpretive framework for local actors; it also became a framework for action. An initial rhetoric of fear over potentially devastating plant closures and job losses spurred local businesses and policymakers into action, enabling more firms to survive the crisis. Early successes also shifted the terrain of discourse from trepidation to a cautious optimism. A similar narrative of measured hope also emerged in Whyalla after 2017 but, unlike south-east Melbourne, discourse did not ‘feedback’ to incentivise collaboration among local agents who, in turn could generate a new, widened, opportunity space. The optimism of Whyalla was, instead, coloured by underlying concern about dependence on a single entrepreneur and the vulnerability of the city to future shocks.

The findings of this paper encourage both academics and policymakers to consider multidimensional factors of change. Core components of place-based industrial strategy, including the need to identify competitive advantages and growth mechanisms like foreign direct investment, integration into global production networks, branding strategies, or the integration of SMEs into economic development (Bailey et al., Citation2018), can be readily understood with reference to the model outlined here. Place-based industrial strategies that focus on region- or time-specific opportunities will be stronger if they consider questions of discourse, especially if regional or local narratives provide a framework that empowers local actors. This analytical framework also highlights the points of overlap or intersection between the three determinants of economic change; that narratives for change, not simply narratives of change, can both become influential when these elements reinforce each other. South-east Melbourne demonstrates how such an intersection can lead to impactful local action. By contrast, Whyalla demonstrates how the absence of such an intersection – and an over-dependence on external economic and political forces – contributes to an ongoing narrative of vulnerability and pessimism.

CONCLUSIONS

Understanding how regions change is a fundamental challenge for regional researchers and policymakers. Over the past two decades significant advances have been made in EEG, institutional theory, place leadership and broader meta-theoretical paradigms. Recent contributions by Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020) represent a major turning point in these debates. This paper has sought to further our understanding in this field by inserting discourse as an active element in change-making, and emphasizing interaction effects in shaping regional transformations. The paper established three objectives. First, it looked to advance recent contributions on the role of agency amongst local and regional actors attempting to influence economic pathways. Second, it sought to explore the question of path realization or regional agility, drawing together two distinct, but complementary, explanations of regional dynamics: the ASID framework of Moulaert et al. (Citation2016) and Grillitsch and Sotarauta’s (Citation2020) ‘trinity’ of change agency. Third, the paper set out to better understand the contribution these emerging perspectives on path creation and path adjustment could make to place-based industry policy. Following Grillitsch and Sotarauta (Citation2020), the paper acknowledged the limitations of established theoretical positions based on EEG or institutional theory and the centrality of agency in regional transformations. It advanced their agency-centric interpretation of regional dynamics by drawing on the work of Moulaert et al. (Citation2016), which recognized discourse as an active element in the reconfiguration of local economies. The two case studies highlighted the prominent role of discourse in empowering action, but how it also served as a force for change in, and of, itself. This represents a fundamental advance conceptually.

The findings inform policymakers on how to construct place-based industrial strategies that are more likely to succeed. The scale of analysis and theorization that underpins this model better informs place-based industrial strategy: it is sensitive to context, cognizant of the interlinkages that exist at the regional or city scale and able to articulate goals that relate to the growth and prosperity of specific places. Importantly, the findings of this paper emphasize the need for place-based industrial strategy to step beyond a focus on enhancing the opportunities available to a region through technological upgrading. A multifaceted approach is called for, one that is able to mobilize leadership in all its forms, establish a framework for envisaging positive change and creating the business opportunities that will shape a new future. This perspective has the potential to reshape industry policy in a way that is more place sensitive (Iammarino et al., Citation2017).

Increasingly policymakers seek to encourage more balanced and inclusive growth, with this imperative gaining impetus as economies recover from the impacts of the Covid-19 pandemic. Nations realize that economic recovery cannot be limited to a small number of sectors or regions, and that policy tools are needed that can foster growth across diverse contexts (Andrews, Citation2020). And, as Lee (Citation2019) observed, there is a need to find models of inclusive growth that resonate at the local level. The post-Covid world represents a new set of opportunity spaces and the potential to develop a forward-looking narrative of sustainable growth, supported by diverse actors. The approach to path creation outlined in this paper has the potential to transform regional pathways and ensure the inclusion of all. Nations will only be able to deliver inclusive growth when they have policy frameworks that are fit for purpose, and this includes strategies that enable cities and regions to ‘pivot’ their economies and secure prosperity in the face of adversity.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Original emphasis.

REFERENCES

- Amin, A. (1999). An institutionalist perspective on regional economic development. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 23(2), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.00201

- Andrews, K. (2020, October 1). Transforming Australian manufacturing to rebuild our economy. Ministry for Industry, Science and Technology. https://www.minister.industry.gov.au/ministers/karenandrews/media-releases/transforming-australian-manufacturing-rebuild-our-economy

- Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS). (2020). Labour force, Australia. ABS. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/[email protected]/DetailsPage/6291.0.55.003Feb%202020?OpenDocument

- Bailey, D., Glasmeier, A., & Tomlinson, P. (2019a). Industrial policy back on the agenda: Putting industrial policy in its place. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12, 319–326. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsz018

- Bailey, C., Galsmeier, A., Tomlinson, P., & Tyler, P. (2019b). Industrial policy: New technologies and transformative innovation policies? Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 12, 169–177. doi:10.1093/cjres/rsz006

- Bailey, D., Pitelis, C., & Tomlinson, C. (2018). A place-based developmental regional industrial strategy for sustainable capture of co-created value. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 42(6), 1521–1542. https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bey019

- Baumgartinger-Seiringer, S., Miörner, J., & Trippl, M. (2021). Towards a stage model of regional industrial path transformation. Industry and Innovation, 28(2), 160–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/13662716.2020.1789452

- Beer, A. (2014). Leadership and the governance of rural communities. Journal of Rural Studies, 34, 254–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2014.01.007

- Beer, A., & Keane, R. (2000). Population decline and service provision in regional Australia. People and Place, 8(2), 69–76.

- Beer, A., McKenzie, F., Blažek, J., Sotarauta, M., & Ayres, S. (2020). Every place matters. Taylor & Francis.

- Berg-Schlosser, D., & De Meur, G. (2009). Comparative research design. In B. Rihoux, & C. R. Ragin (Eds.), Configurational comparative methods (pp. 19–32). Sage.

- Binz, C., & Gong, H. (2021). Legitimation dynamics in industrial path development: New-to-the-world versus new-to-the-region industries. Regional Studies, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1861238

- Boschma, R., Coenen, L., Frenken, K., & Truffer, B. (2017). Towards a theory of regional diversification: Combining insights from evolutionary economic geography and transition studies. Regional Studies, 51(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2016.1258460

- Boschma, R., & Martin, R. (2007). Editorial: Constructing an evolutionary economic geography. Journal of Economic Geography, 7(5), 537–548. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbm021

- Champ, M. (2020, August 13). Sanjeev Gupta’s GFG alliance to buy Tasmania’s TEMCO smelter from South32. ABC Online.

- Charron, N., Dijkstra, L., & Lupente, V. (2014). Regional governance matters: Quality of government within European Union member states. Regional Studies, 48(1), 68–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2013.770141

- Collinge, C., & Gibney, J. (2010). Connecting place, policy and leadership. Policy Studies, 31(4), 379–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442871003723259

- Dinmore, H., & Beer, A. (2021). Narrative and leadership: Lessons for policy and place leadership. In M. Sotarauta, & A. Beer (Eds.), Handbook of city and regional leadership (pp. 43–60). Edward Elgar.

- Fedorowytsch, T., & Keane, D. (2018, December 10). Whyalla population set to boom as billionaire Sanjeev Gupta outlines steelworks vision. ABC Online.

- Frangenheim, A., Trippl, M., & Chlebna, C. (2020). Beyond the single path view: Interpath dynamics in regional contexts. Economic Geography, 96(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2019.1685378

- Garud, R., & Karnøe, P. (2003). Bricolage versus breakthrough: Distributed and embedded agency in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 32(2), 277–300. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(02)00100-2

- Grillitsch, M., & Sotarauta, M. (2020). Trinity of change agency, regional development paths and opportunity spaces. Progress in Human Geography, 44(4), 704–723. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132519853870

- Hassink, R., Isaksen, A., & Trippl, M. (2019). Towards a comprehensive understanding of new regional industrial path development. Regional Studies, 53(11), 1636–1646. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2019.1566704

- Henning, M., Stam, E., & Wenting, R. (2013). Path dependence research in regional economic development: Cacophony or knowledge accumulation?. Regional Studies, 47(8), 1348–1362. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.750422

- Iammarino, S., Rodríguez-Pose, A., & Storper, M. (2017). Why regional development matters for Europe’s economic future (WP No. 07/2017). European Commission.

- Isaksen, A., Jakobsen, A., Njøs, R., & Normann, R. (2018). Regional industrial strategy resulting from individual and system agency. Innovation, 31(1), 48–65. https://doi.org/10.1080/13511610.2018.1496322

- Lee, N. (2019). Inclusive growth in cities: A sympathetic critique. Regional Studies, 53(3), 424–434. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1476753

- MacKinnon, D., Cumbers, A., Pike, A., Birch, K., & McMaster, R. (2009). Evolution in economic geography: Institutions, political economy, and adaptation. Economic Geography, 85(2), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01017.x

- MacKinnon, D., Dawley, S., Pike, A., & Cumbers, A. (2019). Rethinking path creation: A geographical political economy approach. Economic Geography, 95(2), 113–135. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1498294

- Marchant, G. (2020, October 6). Documents reveal Whyalla steelworks owner GFG made surprise request for financial backing. ABC News online.

- Martin, P. (2020, August 12). Billionaire Whyalla steelworks owner Sanjeev Gupta sells Zen Energy back to Ross Garnaut. ABC Online.

- Martin, R. (2010). Rethinking regional path dependence: Beyond lock-in to evolution. Economic Geography, 86(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-8287.2009.01056.x

- Martin, R., & Sunley, P. (2006). Path dependence and regional economic evolution. Journal of Economic Geography, 6(4), 395–437. https://doi.org/10.1093/jeg/lbl012

- Mill, J. S. (1843). A system of logic, volume 1. John W. Parker.

- Miörner, J. (2020). Contextualizing agency in new path development: How system selectivity shapes regional reconfiguration capacity. Regional Studies, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2020.1854713

- Moulaert, F., Jessop, B., & Mehmood, A. (2016). Agency, Structure, Institutions and Discourse (ASID) in urban and regional development. International Journal of Urban Sciences, 20(2), 167–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/12265934.2016.1182054

- Njøs, R., Sjøtun, S. G., Jakobsen, S.-E., & Fløysand, A. (2020). Expanding analyses of path creation: Interconnections between territory and technology. Economic Geography, 96(3), 266–288. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1756768

- North, D. C. (1990). Institutions, institutional change, and economic performance. Cambridge University Press.

- Nurse, A., & Sykes, O. (2020). Place-based vs. place blind? – Where do England’s new local industrial strategies fit in the ‘levelling up’ agenda? Local Economy, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.117/026909422095513

- Oinas, P., Trippl, M., & Höyssä, M. (2018). Regional industrial transformations in the interconnected global economy. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(2), 227–240. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy015

- Productivity Commission. (2014). Australia’s automotive manufacturing industry (Inquiry Report No. 70).

- Puddy, R. (2018, August 15). Gupta’s billion-dollar renewables program the ‘ultimate liberator’ for Australian Industry. ABC Online.

- Reckien, G., & Martinez-Fernandez, C. (2011). Why do cities shrink? European Planning Studies, 19(8), 1375–1397. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2011.593333

- Rihoux, B. (2006). Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and related systematic comparative methods. International Sociology, 21(5), 679–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580906067836

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2013). Do institutions matter for regional development? Regional Studies, 47(7), 1034–1047. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2012.748978

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Safford, S. (2004). Why the Garden Club couldn’t save Youngstown (Working Paper No. IPC-04-002). Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT).

- SEM. (2020). South East Melbourne. http://southeastmelbourne.org/

- Siebert, B., & Marchant, G. (2020, June 10). Whyalla steelworks ‘financially challenged’, Sanjeev Gupta says, but union confident of no cuts. ABC Online.

- Sorensen, A., Eversole, R., & Pugalis, L. (2018, December). Regional agility: A preliminary framework for cultivating future-ready regions. Paper presented at the Australia and New Zealand Regional Science Association International (ANZRSAI) Conference, Canberra, ACT.

- Sotarauta, M. (2016). Leadership and the city. Routledge.

- Sotarauta, M. (2018). Smart specialization and place leadership: Dreaming about shared visions, falling into policy traps? Regional Studies, Regional Science, 5(1), 190–203. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2018.1480902

- Steen, M. (2016). Reconsidering path creation in economic geography: Aspects of agency, temporality and methods. European Planning Studies, 24(9), 1605–1622. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2016.1204427

- Strauss, A. L., & Corbin, J. (1998). Basics of qualitative research. Sage.

- Streeck, W., & Thelen, K. A. (2005). Beyond continuity: Institutional change in advanced political economies. Oxford University Press.