ABSTRACT

We analysed 90,000 contracts involving UK local authorities between 2015 and 2019 to examine patterns and potential drivers of regional sourcing. We found councils in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are much more likely to select suppliers based within their regions compared with their counterparts in England. We found no discernible trend of English councils increasingly preferring regional suppliers, and no correlation between party-political control and regional sourcing. We suggest contrasting institutional and political contexts determine these territorial differences and present a framework to explain supplier selection in these terms, incorporating a territorial dimension alongside more traditional left–right ideological factors.

1. INTRODUCTION

There is growing academic and practitioner interest in how governments could use public procurement to further political objectives such as tackling poverty, promoting sustainability and fostering regional economic development (Morgan, Citation2008; Preuss, Citation2009; Erridge & Hennigan, Citation2012; Alkadry et al., Citation2019; Lerusse & van de Walle, Citation2021). This chimes with a longstanding call to make procurement more strategic and involve politicians in supplier selection, service model design and contract management (Murray, Citation2007), and more recent legal changes that make it easier for public bodies to take account of non-cost factors when judging bids (UK Government, Citation2012; European Commission, Citation2014).

Writing in this journal, Day and Merkert (Citation2021) recently argued that public procurement could help to stimulate regional economic development by supporting manufacturing clusters, echoing the ‘new municipalist’ and ‘buy local’ policies that some high-profile cities have adopted to try to stimulate multiplier effects in the local economy (Uyarra et al., Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2020). This fits with broader ‘community wealth-building’ narratives that propose (re)orienting the procurement strategies of ‘anchor institutions’ (primarily municipal governments, education institutions and other public bodies) around local supply chains to try to retain wealth, power and ownership in local communities (Dubb, Citation2016; Wontner et al., Citation2020).

However, this literature has focused overwhelmingly on the potential impact of such sourcing policies. There have been far fewer studies into the reasons why public bodies might prefer to ‘buy local’. This is surprising, because adopting such a strategy could restrict the pool of potential providers (possibly excluding specialist suppliers that are located elsewhere), make markets less competitive and, ultimately, increase prices. Research into public service outsourcing has highlighted how public authorities controlled by left-wing parties face a similar conflict between political preferences and price, given their ideological opposition to awarding contracts to private suppliers (Schoute et al., Citation2018; Alonso et al., Citation2016; Eckersley et al., Citation2021). Qualitative studies into municipalities with ‘buy local’ policies have focused largely on cities or states controlled by left-wing political parties (Nijaki & Worrel, Citation2012; Thompson et al., Citation2020), and the community wealth-building movement has aligned itself explicitly with left-of-centre politicians and agendas (Kelly & McKinley, Citation2015; Howard, Citation2019; Brown, Citation2022). However, there have been few large-N studies that examine the extent of this phenomenon, compare it across different jurisdictions or study the factors that lead to public bodies preferring suppliers based within their territories. Such factors may be institutional, political, financial, economic or embedded within wider national or regional policy frameworks.

The UK represents an interesting case to examine in this context. Governments at both the UK level and in the devolved nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland have reformed procurement regulations in recent years to allow public bodies to prioritize suppliers based on factors such as their embeddedness in the region or their commitment to social responsibility and environmental protection (UK Government, Citation2012; Scottish Government, Citation2014; Welsh Government, Citation2015). At the regional level within England, the spread of ‘metro-mayors’ and combined authorities, which were established to provide strategic leadership across local authority areas (Giovannini, Citation2021), together with the UK government’s professed desire to ‘level up the economy’ by investing in regions outside of London (Tomaney & Pike, Citation2020), might also be leading to a more territorial approach to public procurement. The UK’s recent withdrawal from the European Union (EU) and its Single Market has added salience to these issues.

We examine the extent to which UK local authorities favour suppliers based within their territories, and test various organizational, political and institutional determinants of regional sourcing. Due to their comparable sizes but contrasting institutional contexts, we compare the approaches of ‘top-tier’ councils situated in the nine regions of England with the approaches of all municipalities in the devolved nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We carried out the analysis using a dataset of over 90,000 contracts agreed between 2015 and 2019. To our knowledge, the output from this paper contains the first quantitative assessment of the extent and causes of regional sourcing by public bodies.

We show that Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish councils are much more likely to select suppliers based within their territories compared with their counterparts in England. This suggests that devolved governments may help to leverage procurement for regional development, and there could be scope for local government in England to adopt a more territorial approach to sourcing. Indeed, we find that those councils with an explicit regional sourcing policy are more likely to rely on suppliers based within their territories than municipalities with no such policy. As such, we build on previous studies into the impact of political ideology on the type of supplier that public sector organizations prefer – whether for-profit or non-profit – by suggesting that procurement decisions also take territorial factors into account. We draw on these findings to propose a new framework to characterize supplier selection within public bodies, incorporating a territorial dimension (upon which we can map a contracting authority’s preference for suppliers based in the same region or nation) alongside the traditional left–right ideological dimension (whereby centre-left parties prefer non-profit providers).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. In the next section we review the literature on public procurement and regional sourcing. We then explain why local government in the UK represents a useful case for examining regional sourcing patterns and set out our hypotheses on their determinants in the UK context. We then describe our method and data collection strategy before setting out the results and discussing their implications. Finally, we summarize our key findings, alongside suggesting further lines of scholarly enquiry and policy recommendations.

2. PUBLIC PROCUREMENT AND REGIONAL SOURCING

In recent years, scholars have begun to examine how governments can use their purchasing spend to pursue such policy objectives as innovation and industrial development (Uyarra et al., Citation2020; Day & Merkert, Citation2021), small and medium-sized enterprise (SME) competitiveness (Pickernell et al., Citation2011; Loader, Citation2007; Flynn, Citation2018) and sustainability (Preuss, Citation2009; Testa et al., Citation2012; Hsueh et al., Citation2020). These research trajectories reflect policy and practitioner interest in the strategic potential of public procurement (Murray, Citation2007), in that it might extend beyond cost considerations to encompass economic, social and environmental objectives (Meehan & Bryde, Citation2011). Given that public procurement averaged 12% of gross domestic product (GDP) and 29% of public spending in advanced economies before the Covid-19 pandemic (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2019) – and the UK government alone spent £290 billion annually on goods and services (UK Government, Citation2020) – it is easy to see why there is such interest in its use as a policy lever.

Much research into the socio-economic potential of public procurement includes a regional or spatial dimension. This is evident in its focus on how contract awards can be used to support local firms (Cabras, Citation2011; Meehan & Bryde, Citation2015), strengthen regional agri-supply chains (Morgan, Citation2008; Lehtinen, Citation2012; Bloomfield, Citation2015), create apprenticeship opportunities for local job seekers (Erridge & Hennigan, Citation2012) and foster industry clusters in economically underperforming zones (Uyarra et al., Citation2020; Day & Merkert, Citation2021). Like regional sourcing by multinational corporations (Crone & Watts, Citation2003), these studies underline the potential of public procurement to act as a demand-side stimulant for employment creation and business growth at the regional level. Local government, health authorities, education institutions and other public service providers are among the biggest economic actors in their regions – local authorities alone account for 23% of regional expenditure in the UK (HM Treasury, Citation2021). As such, their procurement decisions have ramifications for the dynamism of the surrounding business ecosystem (Pickernell et al., Citation2011).

Its potential notwithstanding, there are various barriers to using public procurement for policy goals such as regional development or sustainability. In particular, there is the possibility of tension between minimizing upfront purchasing costs, on the one hand, and taking a holistic view of ‘value for money’ that considers socio-economic and environmental aspects when selecting suppliers, on the other (Loader, Citation2007; Preuss, Citation2009; Bloomfield, Citation2015). This could mean choosing between a lower priced national supplier (which might be a large operator with specialist skills or experience that benefits from economies of scale) and a higher priced local supplier that provides employment, pays local business taxes and purchases from other firms in the region. In such circumstances, cost minimization in the short-run generally takes precedence over whole-life costing because public bodies face perennial pressure to stay within budget (Loader, Citation2007).

While there are several in-depth case studies of sustainable procurement in local government (Lehtinen, Citation2012; Nijaki & Worrel, Citation2012; Gelderman et al., Citation2015), quantitative-based investigations into its organizational and environmental determinants are few. Nonetheless, Lerusse and van de Walle (Citation2021) found that left-wing politicians in Belgium had a stronger preference for pro-social supplier options than right-wing politicians. This is consistent with survey evidence from the United States that has reported that higher levels of sustainable procurement are found in Democratic-leaning constituencies (Opp & Saunders, Citation2013; Alkadry et al., Citation2019).

In addition, top management support and strategic policy intent on the part of the organization, together with change agents who drive initiatives forward, are important factors in realizing green and sustainable public procurement (Meehan & Bryde, Citation2015). Even though regional sourcing has become part of the debate over sustainability in public procurement, gaps remain in our understanding of this area. Scholars have tended to discuss regional sourcing as a by-product of supporting SMEs, creating social value or ‘greening’ the public sector supply chain, rather than as a standalone phenomenon (e.g., Loader, Citation2007; Preuss, Citation2009; Pickernell et al., Citation2011). With a few exceptions (Cabras, Citation2011; Eckersley et al., Citation2021), there is limited insight into the particularities of councils and other public sector organizations sourcing from within their own region, and almost no empirical testing of the factors that support or inhibit this process. This stands in contrast to the predictive studies that have been carried out on ‘green’ public procurement (Testa et al., Citation2012; Lindström et al., Citation2022). As part of redressing this imbalance, our paper puts forward a set of organizational, political and institutional determinants that are germane to explaining regional sourcing. Before setting out the hypotheses, we describe the research context.

3. RESEARCH CONTEXT

For several reasons, local government in the UK represents an interesting context for examining regional sourcing behaviour. The first relates to fiscal constraint. Councils across the UK have experienced significant reductions in their budgets since 2010. Between 2010 and 2018, the UK government reduced its annual funding to English local authorities by a total of £16 billion (49%), with these cuts being largely ‘front-loaded’, in that the largest reductions occurred at the beginning of the decade (National Audit Office (NAO), Citation2018). Although cuts to council budgets in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland were not quite on the same scale, they were nonetheless substantial (Gray & Barford, Citation2018). Such a tight fiscal context makes it difficult to incorporate non-cost factors into procurement decisions (Bloomfield, Citation2015; Flynn, Citation2018). Nonetheless, municipalities such as Preston and Knowsley in the Liverpool city-region have used procurement as a way of stating their overt independence from, and resistance to, central government austerity policies (Thompson et al., Citation2020). Municipal interventions of this kind fit within a wider narrative of community wealth-building, an international civic society movement that promotes local-centred approaches to economic development and community empowerment, partly by (re)focusing the purchasing strategies of anchor institutions around local supply chains to facilitate ‘trickle-up economics’ (Dubb, Citation2016; Kelly & McKinley, Citation2015; Howard, Citation2019; Wontner et al., Citation2020).

Second, policy and legislative initiatives from the UK and devolved governments have encouraged public bodies to consider non-cost factors in procurement decisions. These include the UK Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012, which affects English councils, the Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014, and the Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. Relatedly, the rise in national identities within Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland since devolution at the turn of the millennium could be reflected in a preference for local suppliers (Paun & Macrory, Citation2019).

Alongside these legislative changes in the devolved nations, governance rescaling in England may also be contributing towards regionality in local government procurement. Assertive regional leadership from recently installed metro mayors, such as Andy Burnham in Greater Manchester and Ben Houchen in the Tees Valley, could be leading some areas to adopt overtly localized procurement strategies (Giovannini, Citation2021). These local leaders have tapped into the UK government’s idea to ‘level up’ the country and reduce the wealth gap between the north and south of England. Although critics have argued that this ‘levelling-up’ policy is more sloganeering than any real strategy (Tomaney & Pike, Citation2020), it nonetheless signifies a shift in thinking towards more balanced regional development.

Hence, rescaling and fragmentation of the traditional unitary UK state, alongside broader trends in political populism and the development of new political cleavages aligned with territorial identities, may be resulting in a shift towards regionally and nationally focused public procurement. We consider these issues in our hypotheses.

4. HYPOTHESES

4.1. Regional sourcing policy

Public sector organizations are increasingly adopting policies that favour suppliers capable of supporting social and environmental goals such as employing underrepresented groups and reducing CO2 emissions (Erridge & Hennigan, Citation2012; Lehtinen, Citation2012; Hsueh et al., Citation2020), and/or that aim to facilitate greater SME, third-sector and local firm participation in their supply chains (Meehan & Bryde, Citation2015; Flynn, Citation2018). While sustainable procurement policies do not always translate into practice (Meehan & Bryde, Citation2011), the evidence suggests that the adoption of such policies is associated with improved sustainability performance (Lindström et al., Citation2022). This is explainable by the fact that policies are statements of intent that guide employee behaviour and publicly commit the organization to certain courses of action. We expect that local authorities with written procurement policies on regional sourcing will be more likely to source from suppliers located in their region.

Hypothesis 1: Councils that explicitly refer to local or regional sourcing in their procurement policy, or that have a standalone sustainable procurement policy, will award a relatively higher proportion of their contracts to regional suppliers.

4.2. Political control

As well as organizational-level policy, there is reason to believe that the political group leading the council – whether Conservative, Labour, Independents or No Single Party (NSP) – will have a bearing on the extent to which it prefers regional suppliers. The effect that partisan politics can have on outsourcing and supplier selection decisions in a local government context is firmly established in the literature (Bel & Fageda, Citation2017). Such partisan politics may also influence decisions over the spatial distribution of local authority contracts (Eckersley et al., Citation2021). In line with the community wealth-building narrative, recent qualitative studies into cities with ‘buy local’ policies have focused on municipalities controlled by left-wing parties (Thompson et al., Citation2020). Examples include the city of New Orleans setting a target for sourcing at least half of its goods and services from locally owned businesses, public authorities in Cleveland engaging with worker-owned Evergreen cooperatives instead of multinationals, and Preston council selecting a local contractor for the refurbishment of its landmark Harris Museum (Kelly & McKinley, Citation2015; Howard, Citation2019; Brown, Citation2022). Furthermore, Labour-controlled (i.e., centre-left) councils in England experienced more severe funding cuts than those controlled by other parties from 2010 onwards, and these municipalities are also more likely to be located in deprived parts of the country (Gray & Barford, Citation2018). This should mean that ‘buy local’ policies have greater potential to improve regional economies in such places, and therefore we expect that Labour councils are more likely to contract with suppliers based in their regions or nations than councils controlled by other parties.

Hypothesis 2: Councils controlled by centre-left parties are more likely to award contracts to regional suppliers than councils controlled by either centre-right parties, independents or no single party.

4.3. National context

At national level, the political drive from devolved governments for greater autonomy from Westminster, a growth in national identities and the existence of Scottish- and Welsh-specific sourcing policies could be leading local authorities in Scotland and Wales to purchase more from suppliers based within their territories. Illustrative of the latter, the Scottish Parliament’s Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act 2014 imposes a sustainability duty on contracting authorities by making them consider how their procurement processes can ‘improve the economic, social, and environmental wellbeing of the authority’s area’ (Scottish Government, Citation2014, p. 4). The Welsh government’s Wellbeing of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015 does something similar, requiring public bodies to support the economic, social, environmental and cultural well-being of Wales through their operations, which includes objective setting for sustainable procurement (Welsh Government, Citation2015). Although these legislative drivers are not as apparent in Northern Ireland, geographical and logistical factors make it more practical for Northern Irish councils to do business with Northern Irish suppliers rather than those located in mainland Great Britain.

England’s dominance within the four nations – it accounted for 84% of the UK population in 2020 (Office for National Statistics (ONS), Citation2021) – means that procurement behaviour by English councils needs to be considered within the nine constituent regions of England to ensure that we are comparing units of comparable size and supplier base to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Like Scotland and Wales, England has encouraged sustainable procurement through the Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012 (UK Government, Citation2012) and the Public Contracts Regulations 2015 (UK Government, Citation2015). Both require contracting authorities to assess how the economic, environmental and social well-being of their catchment area may be improved by the goods or services they are procuring. However, due to England’s lack of a devolved assembly, and its patchwork devolution of powers to ‘metro mayors’ in some areas but not others, these institutional pressures for sustainable procurement are likely to be diffuse and, therefore, exert less influence on contracting authorities in England compared with Scotland or Wales. This leads to the following hypothesis:

Hypothesis 3: Councils in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are more likely to contract with suppliers located in their respective nations than councils in England are to contract with suppliers located in their respective regions.

5. METHODS

5.1. Research parameters

We examined over 90,000 contracts that councils in Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland and the 150 ‘upper tier’ authorities in England awarded between May 2015 and March 2019. We chose the 2015–19 timeframe for two reasons. First, UK public bodies were legally required to publish details of their contracts online from May 2015,Footnote1 which ensured that our dataset encompassed all local authorities. Second, the UK was originally scheduled to leave the EU on 29 March 2019, after which it would no longer be subject to EU procurement regulations. Although Brexit was ultimately delayed until January 2020, and the UK’s formal exit from the EU’s internal market did not take place until the end of that year, we felt that the uncertain legal context for procurement during these subsequent months would have added another variable into our model over which we had little control.

As such, we decided to focus solely on this period, comprising almost four full financial years (annual budgets in UK local government run from early April), to try to identify patterns and trends in procurement behaviour, specifically the extent to which councils buy goods, services, works and supplies from providers located in the same territory (the nine regions of England and the three nations of Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland). To give a sense of their relative size and economic weight, total expenditure on services by local councils in each of the nine regions of England, in addition to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, is listed in .

Table 1. Total local government identifiable expenditure on services by country and region, 2019–20.

5.2. Data sources

Our data come from publicly available secondary sources, including the official web portal for government contracts in the UK (Contracts Finder), the ONS and its associated Nomis database, council procurement policies/strategies and local media. We used these secondary data sources to measure our dependent, predictor and control variables. Summary detail on the operationalization and measurement of all variables is provided in .

Table 2. Operationalization and measurement of variables.

5.3. Dependent variable

The dependent variable in this study is the proportion of contracts awarded to firms that are based in the same territory (devolved nation or English region) as the council. Data for the dependent variable were harvested from contract award notices published on Contracts Finder. We paid Tussell, a market intelligence and data analytics firm, to provide details on all service contracts awarded by UK councils between 2015 and 2019. Their dataset contained information on over 120,000 contracts, which we reduced to approximately 90,000 after deleting cases that involved ‘lower-tier’ district councils in England, special purpose bodies such as transport authorities, fire and rescue services or police forces, and those tenders for which no supplier information was available. For each contract awarded, we had information on council name, council address, contract description, date when contract was awarded, awardee name, awardee address, and awardee legal form.

Data relating to the value and length of the contract were missing in many cases. This meant that we were unable to identify the share of procurement spend directed by councils at regional suppliers. As an alternative, we examined the percentage of contracts that each council signed with providers that were based in the same territory as them, based on the address of the supplier. We then determined the percentage of contract awards made by the 215 councils to regional suppliers for each of the four years and calculated their overall average.

5.4. Predictor variables

5.4.1. Regional sourcing policy

Regional sourcing policy is a binary variable. Councils with a procurement policy that explicitly refers to supporting local and regional suppliers, or that have a standalone sustainable sourcing policy or equivalent,Footnote2 are coded 1. Councils with a procurement policy that does not explicitly refer to supporting local and regional suppliers or that have no procurement policy are coded 0. Data for this variable was obtained by the research team visiting the website of each council, locating their business section, and reviewing their procurement policies and strategy statements where available. Approximately 69% of councils were coded as 1 and 31% coded as 0.

5.4.2. Political control

Political control is a four-category variable containing Conservative-controlled councils, Labour-controlled councils, Independent-controlled councils and NSP-controlled councils. Conservative and Labour are the two biggest political parties in the UK at local and national level, and proxy the right–left split normally used when modelling the effect of partisan politics on outsourcing and supplier selection decisions (Schoute et al., Citation2018). Independents are elected officials who are not aligned to any political party but come together to form a ruling group.Footnote3 The NSP category refers to councils where neither Conservatives, Labour, nationalist parties such as Scottish National Party (SNP) and Plaid Cymru (Wales) or Independents had a controlling majority for the entire 2015–19 period. Figures for the political control of the 215 UK councils in this study are 21.9% for Conservative, 34.9% for Labour, 2.3% for Independents and 40.9% for NSP. Data on political control were obtained from council websites and media sources.

5.4.3. Nation

Nation is the other four-category predictor variable. It is made up of the four nations of the UK: England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Scotland and Wales have devolved parliaments, and Northern Ireland has a devolved assembly. Each of the three devolved administrations is responsible for local government in their territories. There is no equivalent parliament exclusively for England. Out of the 215 councils, 150 are in England (69.7%), 32 are in Scotland (14.8%), 22 are in Wales (10.2%) and 11 are in Northern Ireland (5.1%).

5.5. Control variables

There are five control variables in this study. The first is the total number of service contracts awarded by councils over the 2015–19 period. Some councils issue contracts at a greater frequency and in smaller lots than others, which could make them more winnable for local firms. The second control variable is the size of the council, which we measure using resident population. Size could make it more likely that councils look beyond the local and regional supply marketplace to find a suitable contractor. Councils with bigger populations may perceive that only national-level operators have the requisite organizational capacity and technical expertise for delivering public and social services on their behalf. In addition, larger, national-level suppliers may be less interested in bidding for work with smaller councils, which would leave the field more open for local or regional players.

Studies into sustainable public procurement indicate that there may be a relationship between socio-economic conditions and procurement priorities at local government level (Preuss, Citation2009; Cabras, Citation2011; Erridge & Hennigan, Citation2012). We therefore control for affluence and job density in each council area. Affluence is measured as median weekly earnings. In less affluent areas, councils have a vested interest in supporting local enterprises and maximizing the economic multiplier effect that comes from trading locally. Job density is the level of jobs per resident in the council area. There is evidence that councils with low job density prioritize spend with local and regional firms as part of sustaining existing employment and creating new employment opportunities (Preuss, Citation2009). We control for a similar effect in our study.

The final control variable relates to business density in regions and nations of the UK. The opportunity for councils to source regionally depends on the availability of businesses within the region – what Crone and Watts (Citation2003) label ‘regional supply potential’. A high density of businesses increases the likelihood that councils will be able to source within their own region. Business density is a standardized measure, calculated as the number of firms per 10,000 of the adult population for each region of the UK.

5.6. Analytical approach

The model was tested using multiple linear regression in IBM SPSS Statistics. The estimation technique was ordinary least squares (OLS). Data were available for all variables except job density figures for Northern Ireland councils (n = 11). We used the mean value of job density for UK local government areas as a replacement variable. The dependent variable is the percentage of contracts awarded to suppliers located in the same region as the local authority. The predictors and controls in our model are made up of categorical variables (regional sourcing policy, political control, nation) and scale variables (total contracts, population, earnings, job density, business density). We entered the variables block by block. The five control variables were the first block (model 1a). Regional sourcing variable was the second block (model 1b). Political control was the third block (model 1c). Nation was the fourth block (model 1d). Diagnostic checks for multi-collinearity were carried out as part of the analysis. Variance inflation factors (VIFs) did not go above 1.8. Tolerance values (TVs) did not go below 0.53. These values confirmed that multi-collinearity was not a problem in the dataset. contains descriptive statistics and correlation coefficients for all variables.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and correlations for all variables.

6. RESULTS

6.1. Descriptive analysis

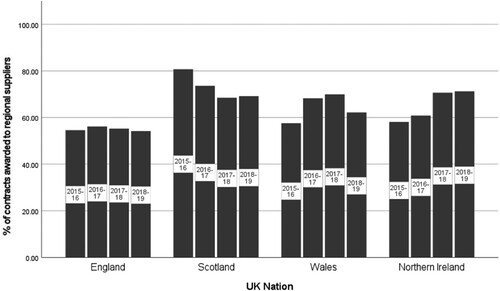

Variation exists in the extent to which councils across the four UK nations source from suppliers located in their own territory (). Councils in England have a comparatively low rate of regional sourcing. The percentage of contracts awarded by English councils to suppliers in their own region averaged 56% between 2015 and 2019. There was no significant increase or decrease on this rate over this time period, and no clear pattern in regional sourcing across English councils. Some councils increased the proportion of contracts awarded to suppliers within their territories, whereas others decreased the proportion.

Councils in the other three UK nations have higher rates of regional sourcing than England. Scottish councils have, on average, the highest rate. Approximately 78% of the contracts they awarded went to Scottish-based providers. While the rate dropped between 2015 and 2019, it remained the highest of the four UK nations. Councils in Wales and Northern Ireland awarded, on average, 69% and 64% of contracts to suppliers in their own regions between 2015 and 2019, respectively. Regional sourcing by councils in both these nations has also increased over time.

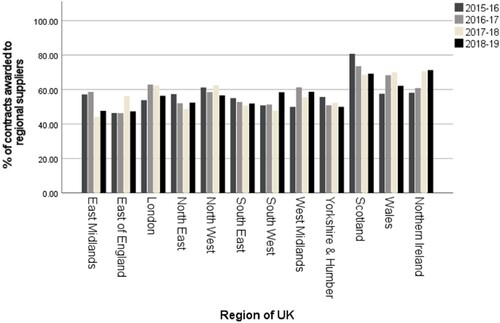

Further disaggregation of the data shows that the share of regional sourcing in none of the nine English regions equals the figures for Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland (). Even councils in the economically strongest English regions (London, West Midlands and the North West) have lower rates of regional sourcing than councils in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Only councils in London and the North West have averaged above 60% of contract awards to their own region suppliers; for the other seven English regions the corresponding figures were between 50% and 59%.

6.2. Predictive analysis

The results offer satisfactory support to the model and to the hypothesized relationships. The model is statistically significant (p < 0.01) and accounts for approximately one-third variance in the proportion of contract awards made by UK councils to regional suppliers (adjusted R2 = 0.348, R2 = 0.385). The addition of each block of variables led to a positive change in the adjusted R2. The biggest positive change resulted from the variable ‘nation’. It increased the adjusted R2 number by 0.14. The other blocks resulted in smaller positive changes. The regression results, broken down block by block, are reproduced in .

Table 4. Determinants of contract awards made by councils to suppliers in their own region.

Hypothesis 1 predicted that councils with a policy commitment to regional sourcing would award a higher proportion of their contracts to their own region firms. In other words, we expected policy intention to be a predictor of procurement action. Support is returned for Hypothesis 1. Councils with such a policy commitment, whether written into their existing procurement policy or formalized in a stand-alone sustainable sourcing policy, are statistically more likely to contract with regional suppliers than councils without such a policy commitment. There is a diminution in effect after the political and nation variables are added to the model, going from β = 0.141 p < 0.05 to β = 0.116, p = 0.59. Nonetheless, the policy variable remains at least partially significant and so we accept Hypothesis 1.

Hypothesis 2 predicted that political control of councils influences the geographical destination of contracts. Specifically, we reasoned that Labour-controlled councils would award a greater proportion of their contracts to regional suppliers compared with Conservative-, NSP- or Independent-controlled councils. Qualitative studies have highlighted how some left-wing councils in the UK and internationally have made concerted attempts to ‘buy local’, and the community wealth-building narrative has been influential within social democratic circles. These councils are also more likely to be located in deprived parts of the country, meaning that stimulating local supply chains through public procurement could be a higher political priority in these areas. However, Labour-controlled councils are not more likely than Conservative-controlled councils to award contracts to suppliers based within their regions. In fact, Labour-controlled councils are statistically less likely to source from regional suppliers than NSP- or Independent-controlled councils. As such, Hypothesis 2 is rejected. As we will see next, the effects of NSP- and Independent-controlled councils on regional sourcing disappear when nation is taken into account.

Hypothesis 3 was based on the a priori assumption that councils in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland would exhibit higher levels of regional sourcing than those in England. In the cases of Scotland and Wales, this was because their political and institutional contexts have been more proactive in directing them to use procurement for national economic development; for Northern Irish councils it was due to its geographical separation from mainland Great Britain. By contrast, there are no similar devolved institutions pushing for regional procurement in England, and no comparable geographical obstacles to realizing it. Strong support was forthcoming for this hypothesis. Councils in Scotland (β = 0.515 p < 0.01), Wales (β = 0.275 p < 0.01) and Northern Ireland (β = 0.210 p < 0.01) are statistically more likely to award contracts to suppliers in their own territories than councils in England.

Apart from the main predictor variables, the results show that larger councils are statistically less likely to engage suppliers from their own region (β = –0.179 p < 0.05) and that the total number of contracts put out to tender by councils is positively associated with the proportion won by regional suppliers (β = 0.295 p < 0.01). The remaining control variables are not statistically significant.

7. POLICY IMPLICATIONS

Despite recent policy shifts and the UK’s various governments being much more explicit about their desire for public bodies to use procurement to stimulate local economic development, we found limited evidence that municipalities are increasingly relying on suppliers based within their regions or nations. Councils in Wales and Northern Ireland did increase their share of contracts agreed with providers located within their respective territories, but there is no clear trend in this direction in England, and regional sourcing fell slightly in Scotland (albeit from a much higher base).

English councils are significantly less likely to contract with suppliers based in their territories than their Scottish, Welsh and Northern Irish counterparts. As such, there may be scope for them to increase this practice and reap potential benefits in terms of local economic development. With this in mind, recent subnational governance rescaling within England and the election of ‘metro mayors’ who seek to champion their local areas (Giovannini, Citation2021), together with the fact that councils such as Preston are embracing community wealth-building (Brown, Citation2022), could lead to more widespread adoption of local sourcing as a public procurement strategy.

Indeed, and notwithstanding the possibility that fiscal constraints might prevent Labour councils from pursuing procurement approaches that fit with their political priorities around community wealth-building, we suggest that territorial political factors can influence supplier selection. Although left–right ideologies did not explain any preference for regional or national suppliers in our study, stronger territorial identities – particularly if they are mobilized through specific political parties such as the SNP or Plaid Cymru, or Sinn Féin in Northern Ireland, and expressed through powerful devolved institutions – may help to explain any preference for suppliers located nearby. Local elections in Scotland and Northern Ireland use the single transferable vote system, which could mask how this dimension operates within the UK, because it meant that nearly all the councils in these two countries were not under the control of a single political party during our period of analysis. If, for example, the SNP had controlled a substantial proportion of councils in Scotland, its ideological agenda of independence from the UK may have contributed towards even higher rates of sourcing goods and services from Scottish suppliers.

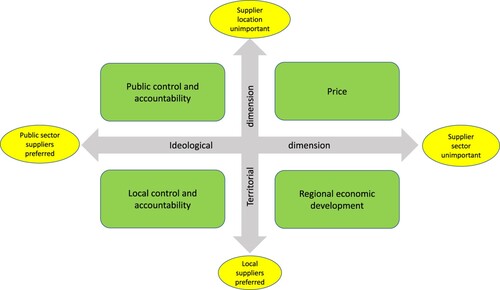

With this in mind, we propose that two different dimensions can shape supplier selection. Alongside left–right ideological distinctions that influence whether a public body prefers to buy from the private or public sectors (Bel & Fageda, Citation2017), some organizations may also take account of territorial factors – whether a supplier is based within their region or not – when awarding contracts (Day & Merkert, Citation2021). These territorial factors will probably be more influential where devolved institutions represent the region in question, and particularly where political leaders seek to champion the area through explicit ‘buy local’ policies. We plot these two dimensions to create a framework for examining local government sourcing (), highlighting how the procurement approach of any public body could be underpinned by different principles. Since external factors (such as the financial health of the organization and the legal context within which it operates) will also shape decision-making, the framework represents an ideal situation in which political priorities can be expressed through supplier selection. On this basis, municipalities located in each of the quadrants may exhibit the following characteristics – particularly in states with strong territorial identities:

Top-left: public control of public services is a key factor, and therefore public sector suppliers are preferred, but the location in which they are located is less important. Likely to be led by left-wing political parties with a national focus.

Top-right: price is the overriding priority: the sector and location of a supplier is unimportant. Likely to be led by right-wing political parties with a national focus.

Bottom-left: local public control of public services is very important, and therefore the organization prefers to contract with public sector suppliers based in the same territory. Likely to be led by left-wing political parties with a regional or secessionist focus.

Bottom-right: local economic development is the key priority; it is less important whether suppliers are non-profit organizations or private companies. Likely to be led by right-wing political parties with a regional or secessionist focus.

In addition, the legislative and policy changes precipitated by Brexit could accelerate a trend towards more regional sourcing in the UK. Since leaving the European Single Market at the end of 2020, the UK has not been subject to EU procurement regulations, and in a recent Green Paper the UK government sought ‘to send a clear message that commercial teams do not have to select the cheapest bid and that they can design evaluation criteria to include wider economic, social or environmental benefits’ (UK Government, Citation2020, p. 34). Legislation to set these principles in law featured in the 2022 Queen’s Speech.

Moreover, post-Brexit trade rules implemented under the Trade and Cooperation Agreement (TCA) resulted in a 25% drop in UK imports from EU countries in 2021 and a simultaneous decline in the export of low value products by UK firms to EU countries (Freeman et al., Citation2022). This points to opportunities for domestic firms to replace EU companies as business-to-government (B2G) contractors. Some export firms may also pivot towards the home market as EU customers become less commercially attractive. In this sense, the interests of public sector buyers and domestic suppliers may be brought closer together over the coming years. Therefore, although Brexit will almost certainly have a negative impact on trade flows, it could have a silver lining in the form of greater local sourcing and its attendant business, employment, social, ethical and environmental gains. The Northern Ireland protocol, which introduced customs checks on imports into Northern Ireland from the rest of the UK following Brexit, may also have affected sourcing strategies in that part of the UK. Durparc-Portier and Figus (Citation2021) highlight how Northern Irish firms are likely to reduce their trade with mainland Great Britain and replace it with imports from the Republic of Ireland, other EU countries and the rest of the world – a prediction that has thus far been borne out in terms of food imports and exports (Central Statistics Office Ireland (CSO), Citation2021). Although the future of the protocol remains uncertain in autumn 2022, we might nonetheless expect to find a similar trend in public procurement.

Furthermore, recent international events are combining to create a political and economic environment that favours local sourcing in the rest of the UK. The Covid-19 pandemic and latterly the war in Ukraine have exposed the fragility of global value chains and caused significant disruption to public and private sector supply lines (Craighead et al., Citation2020). As a result, resilience and security have moved centre stage in supply chain management (OECD, Citation2020). Stock buffers and national borders are back on the business agenda as part of a shift towards de-globalization (Brakman et al., Citation2020) or ‘slowbalization’ (Gong et al., Citation2022). As with Brexit, this bodes well for domestic suppliers because re-localizing supply chains and reshoring production is one way to mitigate the risks of business interruption from exogeneous shocks. This localization shift dovetails with the philosophy of community wealth-building, which believes that bottom-up economic development creates resilient organizations and societies that are better able to cope with the vagaries of the modern economy (Howard, Citation2019). At the same time, however, public bodies that operate within severe financial constraints may find it difficult to embrace regional sourcing if leads to less competitive markets and therefore higher costs.

8. CONCLUSIONS

We found that an organizational commitment to regional or sustainable sourcing means councils are more likely to purchase from suppliers based in their territories. Given that municipal governments are hierarchical and bureaucratic organizations, we assume that the causal relationship operates in this direction (i.e., procurement staff buy more from regional suppliers because executives have asked them to do so, rather than the policy reflecting existing practices). Although perhaps expected, this is nonetheless a notable finding: it shows that senior decision-makers within local government can influence procurement policy in those areas where they have made their preferences clear. As such, it contributes to existing literature on the drivers of sustainable public procurement (Opp & Saunders, Citation2013; Alkadry et al., Citation2019; Lerusse & van de Walle, Citation2021) and has implications for practice: namely that introducing such policies does affect organizational activity. By extension, it also has implications for other sectors where high-profile local policy announcements have often been dismissed as symbolic, such as climate change emergency declarations (Ruiz-Campillo et al., Citation2021).

Also noteworthy is the lack of an obvious party-political dimension to local sourcing. Despite previous qualitative studies focusing on the local sourcing strategies of predominantly left-wing municipalities (e.g., Thompson et al., Citation2020), we found no correlation between Labour Party control and a preference for suppliers located in the same region or nation as the council. This might reflect the fact that Labour councils in England experienced deeper funding cuts from 2010 onwards compared with their counterparts in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland (Gray & Barford, Citation2018), and therefore may wish to prioritize costs rather than the potential social outcomes of procurement decisions. By minimizing procurement expenditure in this way, these municipalities could be able to protect budgets for essential services – another policy priority that is often associated with centre-left parties.

In addition, given that English authorities experienced very deep cuts in the early 2010s, after which annual percentage reductions in their funding were less severe, we suggest that this initial period of substantial austerity was influential in shaping their sourcing strategies over the medium term. Indeed, Eckersley et al. (Citation2021) argue that these fiscal constraints meant Labour councils in England were less likely to contract with non-profit suppliers than they hypothesized at the outset of their study. Although left-wing municipalities might wish to avoid contracting with private companies, and also prefer to buy from providers based within their territories, such political preferences may be overridden by the desire to maximize the number of potential bidders in order to obtain lower prices. These findings build on previous studies that have examined local government supplier selection from a political perspective, and which have returned mixed results (Alonso et al., Citation2016; Zafra-Gomez et al., Citation2016; Schoute et al., Citation2018).

Most studies in this area have focused on the potential benefits and challenges of regional sourcing, rather than its political, institutional and/or territorial drivers (Morgan, Citation2008; Cabras, Citation2011; Lehtinen, Citation2012; Bloomfield, Citation2015). Our paper therefore represents an important contribution to the literature in this respect, and our framework could serve as a starting point to organize and direct future research. Given the growth in nationalism, secessionism and populism over recent years in many countries, this may be a more fruitful avenue for studies that seek to identify the political dynamics of regional sourcing and the role of institutional actors below the level of federal or central governments. We did not find evidence of other studies in the literature and would strongly encourage research into jurisdictions that have comparable territorial political cleavages, such as Catalonia, the Basque Country, Quebec or Flanders, to identify whether similar dynamics are in place elsewhere. It would be particularly interesting to examine cases in which a larger proportion of municipalities are run by executive mayors or councillors from secessionist parties within such territories. If councils in such contexts operate within fewer financial constraints than they do in England, we might also expect such political priorities to be more evident in sourcing strategy and supplier selection.

Although our dataset provides a comprehensive picture of all the contracts involving top-tier UK local authorities between 2015 and 2019, it also has some limitations because it lacked sufficient information about the length and value of many contracts. Therefore, we were unable to identify the share of each council’s procurement spend that was directed at nearby suppliers. There is an opportunity for other scholars to extract data on contract value from sites like Contracts Finder and extend our study by examining the share of procurement spend won by local suppliers on a region/nation basis and whether this has changed since Brexit and the Covid-19 pandemic. Information about the specific location of each supplier, rather than simply the region or nation within which it is located, may have also revealed more about the extent to which councils ‘buy local’; unfortunately, however, examining each of the 90,000 lines of data would be an extremely resource-intensive exercise. Another line of future enquiry relates to the impacts of local sourcing on firm-level performance. Consistent with the procurement literature, our assumption is that public contracts offer tangible and intangible benefits to suppliers. These include guaranteed payment, customer diversification, reputation enhancement and organizational learning (Loader, Citation2007; Preuss, Citation2009; Cabras, Citation2011). This finds support in the economics field, where public contract awards have been shown to lead to improvements in profitability, productivity, staff numbers and sales growth, sometimes over the duration of the contract and sometimes beyond it (Fadic, Citation2020; Ravenda et al., Citation2022). We encourage further research into firm- and industry-level impacts resulting from the award of local government contracts. In respect of the latter, for example, studies might examine whether changes in the volume and value of public contracts awarded by councils have knock-on effects for regional businesses.

Qualitative studies are also necessary to gauge the extent to which any such central policy or legislative shift is responsible for a change in local decision-making, or whether other factors (such as cost, the desire to protect budgets for essential services from cuts, local political influence, or – particularly in the case of Northern Ireland – the prospect of regulatory barriers) may be more influential. While Murray (Citation2007) and Gelderman et al. (Citation2015) have undertaken qualitative investigations into sustainable procurement in local government, the inter-play between local government and devolved administrations remains a grey area in research. Nonetheless, we hope that our study provides a useful starting point and reflection of the ‘state of play’ of regional sourcing within UK local government, and may help subsequent research to delve more deeply into these issues.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We thank the anonymous reviewers and journal editors for their constructive comments on previous versions of this article.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. On the website www.gov.uk/contracts-finder/.

2. Equivalents include both social value procurement and responsible procurement policies.

3. One council, Sutton, in England was controlled by the Liberal Democrats between 2015 and 2019. It was included as one of the five independent-controlled councils.

REFERENCES

- Alkadry, M. G., Trammell, E., & Dimand, A.-M. (2019). The power of public procurement: Social equity and sustainability as externalities and as deliberate policy tools. International Journal of Procurement Management, 12(3), 336–362. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPM.2019.099553

- Alonso, J. M., Andrews, R., & Hodgkinson, I. R. (2016). Institutional, ideological and political influences on local government contracting: Evidence from England. Public Administration, 94(1), 244–262. https://doi.org/10.1111/padm.12216

- Bel, G., & Fageda, X. (2017). What have we learned from the last three decades of empirical studies on factors driving local privatisation? Local Government Studies, 43(4), 503–511. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2017.1303486

- Bloomfield, C. (2015). Putting sustainable development into practice: Hospital food procurement in Wales. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 2(1), 552–558. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2015.1100094

- Brakman, S., Garretsen, H., & van Witteloostuijn, A. (2020). The turn from just-in-time to just-in-case globalization in and after times of COVID-19: An essay on the risk re-appraisal of borders and buffers. Social Sciences & Humanities Open, 2(1), 100034. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2020.100034

- Brown, M. (2022). Preston is putting socialist policies into practice. Tribune, January 20. https://tribunemag.co.uk/2022/01/community-wealth-building-preston-trade-unions-labour-party

- Cabras, I. (2011). Mapping the spatial patterns of public procurement: A case study from a peripheral local authority in Northern England. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 24(3), 187–205. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551111121338

- Central Statistics Office Ireland (CSO). (2021). Food and agriculture: A value chain analysis. CSO. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/fp/p-favca/foodandagricultureavaluechainanalysis/effectofbrexitontrade/

- Craighead, C. W., Ketchen Jr, D. J., & Darby, J. L. (2020). Pandemics and supply chain management research: Toward a theoretical toolbox. Decision Sciences, 51(4), 838–866. https://doi.org/10.1111/deci.12468

- Crone, M., & Watts, H. D. (2003). The determinants of regional sourcing by multinational manufacturing firms: Evidence from Yorkshire and Humberside, UK. European Planning Studies, 11(6), 717–737. https://doi.org/10.1080/0965431032000108387

- Day, C. J., & Merkert, R. (2021). Unlocking public procurement as a tool for place-based industrial strategy. Regional Studies, https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1956682

- Dubb, S. (2016). Community wealth-building forms: What they are and how to use them at the local level. Academy of Management Perspectives, 30(2), 141–152. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2015.0074

- Durparc-Portier, G., & Figus, G. (2021). The impact of the new Northern Ireland protocol: Can Northern Ireland enjoy the best of both worlds? Regional Studies, 56(8), 1404–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1994547

- Eckersley, P., Flynn, A., Ferry, L., & Lakoma, K. (2021). Austerity, political control and supplier selection in English local government: Implications for autonomy in multi-level systems. Public Management Review, https://doi.org/10.1080/14719037.2021.1930122

- Erridge, A., & Hennigan, S. (2012). Sustainable procurement in health and social care in Northern Ireland. Public Money & Management, 32(5), 363–370. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2012.703422

- European Commission. (2014). Directive 2014/24/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council. EUR-Lex-32014L0024-EN-EUR-Lex (europa.eu).

- Fadic, M. (2020). Letting luck decide: Government procurement and the growth of small firms. The Journal of Development Studies, 56(7), 1263–1276. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220388.2019.1666979

- Flynn, A. (2018). Investigating the implementation of SME-friendly policy in public procurement. Policy Studies, 39(4), 422–443. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442872.2018.1478406

- Freeman, R., Manova, K., Prayer, T., & Sampson, T. (2022). Unravelling deep integration: UK trade in the wake of Brexit (Discussion Paper No. 1847). Centre for Economic Performance (CEP). https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/dp1847.pdf

- Gelderman, C. J., Semeijn, J. & Bouma, F. (2015). Implementing sustainability in public procurement: The limited role of procurement managers and party-political executives. Journal of Public Procurement, 15(1), 66–92. 10.1108/JOPP-15-01-2015-B003

- Giovannini, A. (2021). The 2021 metro mayors elections: Localism rebooted? The Political Quarterly, 92(3), 474–485. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.13036

- Gong, H., Hassink, R., Foster, C., Hess, M., & Garretsen, H. (2022). Globalisation in reverse? Reconfiguring the geographies of value chains and production networks. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(2), 165–181. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsac012

- Gray, M., & Barford, A. (2018). The depths of the cuts: The uneven geography of local government austerity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(3), 541–563. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsy019

- HM Treasury. (2021). Public expenditure statistical analyses 2021. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1003755/CCS207_CCS0621818186-001_PESA_ARA_2021_Web_Accessible.pdf

- Howard, T. (2019). Trickle-up economics: How Cleveland, Ohio, and Preston, Lancashire, are bringing it all back home. Prospect Magazine, July 13. https://www.prospectmagazine.co.uk/sponsored/trickle-up-economics

- Hsueh, L., Bretschneider, S., Stritch, J. M., & Darnall, N. (2020). Implementation of sustainable public procurement in local governments: A measurement approach. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(6/7), 697–712. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-09-2019-0233

- Kelly, M., & McKinley, S. (2015). Cities building community wealth. Democracy Collaborative. https://democracycollaborative.org/learn/publication/cities-building-community-wealth

- Lehtinen, U. (2012). Sustainability and local food procurement: A case study of Finnish public catering. British Food Journal, 114(8), 1053–1071. https://doi.org/10.1108/00070701211252048

- Lerusse, A., & van de Walle, S. (2021). Local politicians’ preferences in public procurement: Ideological or strategic reasoning? Local Government Studies, 48(4), 680–703. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2020.1864332

- Lindström, H., Lundberg, S., & Marklund, P. O. (2022). Green public procurement: An empirical analysis of the uptake of organic food policy. Journal of Purchasing and Supply Management, 28(3), 1007–1052. 10.1016/j.pursup.2022.100752

- Loader, K. (2007). The challenge of competitive procurement: Value for money versus small business support. Public Money and Management, 27(5), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9302.2007.00601.x

- Meehan, J., & Bryde, D. (2011). Sustainable procurement practice. Business Strategy and The Environment, 20(2), 94–106. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.678

- Meehan, J., & Bryde, D. J. (2015). A field-level examination of the adoption of sustainable procurement in the social housing sector. International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 35(7), 982–1004. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-07-2014-0359

- Morgan, K. (2008). Greening the realm: Sustainable food chains and the public plate. Regional Studies, 42(9), 1237–1250. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400802195154

- Murray, J. G. (2007). Strategic procurement in UK local government: The role of elected members. Journal of Public Procurement, 7(2), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOPP-07-02-2007-B003

- National Audit Office (NAO). (2018). Financial sustainability of local authorities 2018. https://www.nao.org.uk/report/financial-sustainability-of-local-authorities-2018/

- Nijaki, L., & Worrel, G. (2012). Procurement for sustainable local economic development. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 25(2), 133–153. https://doi.org/10.1108/09513551211223785

- Office of National Statistics (ONS). (2021). Population estimates for the UK, England and Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland: Mid-2020. https://www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/populationandmigration/populationestimates/bulletins/annualmidyearpopulationestimates/mid2020

- Opp, S. M., & Saunders, K. L. (2013). Pillar talk: Local sustainability initiatives and policies in the United States—finding evidence of the ‘three E’s’: economic development, environmental protection, and social equity. Urban Affairs Review, 49(5), 678–717. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087412469344

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2019). Government at a glance 2019. OECD Publ. https://doi.org/10.1787/8ccf5c38-en

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). Covid-19 and global value chains: Policy options to build more resilient production networks. https://www.oecd.org/coronavirus/policy-responses/covid-19-and-global-value-chains-policy-options-to-build-more-resilient-production-networks-04934ef4/

- Paun, A., & Macrory, S. (2019). Has devolution worked? The first 20 years. Institute for Government. https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/has-devolution-worked-essay-collection-FINAL.pdf

- Pickernell, D., Kay, A., Packham, G., & Miller, C. (2011). Competing agendas in public procurement: An empirical analysis of opportunities and limits in the UK for SMEs. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 29(4), 641–658. https://doi.org/10.1068/c10164b

- Preuss, L. (2009). Addressing sustainable development through public procurement: The case of local government. Supply Chain Management, 14(3), 213–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/13598540910954557

- Ravenda, D., Melina Valencia-Silva, M., Maria Argiles-Bosch, J., & García-Blandón, J. (2022). Effects of the award of public service contracts on the performance and payroll of winning firms. Industrial and Corporate Change, 31(1), 186–214. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dtab067

- Ruiz-Campillo, X., Castán Broto, V., & Westman, L. (2021). Motivations and intended outcomes in local governments’ declarations of climate emergency. Politics and Governance, 9(2), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.17645/pag.v9i2.3755

- Schoute, M., Budding, T., & Gradus, R. (2018). Municipalities’ choices of service delivery modes: The influence of service, political, governance, and financial characteristics. International Public Management Journal, 21(4), 502–532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10967494.2017.1297337

- Scottish Government. (2014). Procurement Reform (Scotland) Act. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/asp/2014/12/contents

- Testa, F., Iraldo, F., Frey, M., & Daddi, T. (2012). What factors influence the uptake of GPP (green public procurement) practices? New evidence from an Italian survey. Ecological Economics, 82, 88–96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecolecon.2012.07.011

- Thompson, M., Nowak, V., Southern, A., Davies, J., & Furmedge, P. (2020). Re-grounding the city with Polanyi: From urban entrepreneurialism to entrepreneurial municipalism. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(6), 1171–1194. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19899698

- Tomaney, J., & Pike, A. (2020). Levelling up? The Political Quarterly, 91(1), 43–48. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-923X.12834

- UK Government. (2012). Public Services (Social Value) Act 2012. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2012/3/enacted

- UK Government. (2015). Public contracts regulations 2015. https://www.legislation.gov.uk/uksi/2015/102/contents/made

- UK Government. (2020). Transforming public procurement. https://www.gov.uk/government/consultations/green-paper-transforming-public-procurement

- Uyarra, E., Zabala-Iturriagagoitia, J. M., Flanagan, K., & Magro, E. (2020). Public procurement, innovation and industrial policy: Rationales, roles, capabilities and implementation. Research Policy, 49(1), 103844. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2019.103844

- Welsh Government. (2015). Well-being of Future Generations (Wales) Act 2015. https://www.futuregenerations.wales/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/WFGAct-English.pdf

- Wontner, K. L., Walker, L., Harris, I., & Lynch, J. (2020). Maximising ‘community benefits’ in public procurement: Tensions and trade-offs. International Journal of Operations and Production Management, 40(12), 1909–1939. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOPM-05-2019-0395

- Zafra-Gómez, J. L., López-Hernández, A. M., Plata-Díaz, A. M., & Garrido-Rodríguez, J. C. (2016). Financial and political factors motivating the privatisation of municipal water services. Local Government Studies, 42(2), 287–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/03003930.2015.1096268