?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The objective of this article is to investigate cross-border real economic convergence, defined as the process of reducing the asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border areas in the conditions of European (territorial) integration. The analysis applies the relative asymmetry index which compares the level of regional gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (purchasing power standards – PPS) of neighbouring border areas. Its results confirm the occurrence of σ-convergence (in the periods 1980–85, 1985–94 and 2004–15) and absolute cross-border β-convergence (in different subperiods in the period 1980–2015). The obtained results also suggest that cross-border convergence generally progresses slower than convergence at the international level.

1. INTRODUCTION

National borders constitute a barrier hindering the course of socio-economic interactions (Rietveld, Citation2012). Therefore, they negatively affect the development of areas traditionally perceived as peripheral, backward and lagging in economic terms. Due to a whole array of geographical, historical, socio-economic and institutional conditions, Europe still exhibits considerable disproportions in the level of economic development between particular states, something especially evident in cross-border areas. This is because borders – as the ‘scars of history’ (Hiepel, Citation2016, p. 263) – are an important separating factor, conserving the existing developmental differences between neighbouring areas.

High hopes for overcoming this situation are sought in the process of European integration and – more specifically – European territorial integration, which have meaningfully progressed over the last several decades (Anderson et al., Citation2003; Kolosov & Więckowski, Citation2018; Nelles & Walther, Citation2011). Being a rather general and multifaceted process driven mainly by national states (Zielonka, Citation2017), European integration has led to the harmonization of policies of European states in multiple dimensions (political, economic, social, cultural, institutional, etc.). Motivated, inter alia, by the establishment of a Single European Market, European integration has made great efforts to promote economic integration and reduce the negative effects of borders by encouraging the free movement of goods, persons, services and capital across national borders, as well as promoting European Monetary Union (Nelles & Walther, Citation2011). European territorial integration, oriented more towards spatial-related aspects, leads to a gradual elimination of barriers resulting from the existence of traditional national borders and differences related, inter alia, to the functioning of separate economic, administrative, legal, fiscal, infrastructural and socio-cultural systems (Medeiros et al., Citation2022). Implying the involvement of a complex network of territorial actors in jointly coordinating policies, European territorial integration fosters greater homogeneity in the European space through increased interdependencies and interactions in cross-border regions (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999; Durand et al., Citation2020; Durand & Decoville, Citation2020; Medeiros, Citation2018a; Sohn, Citation2014; Sohn & Licheron, Citation2018; Sohn & Reitel, Citation2016; Sohn et al., Citation2009). Due to these factors, the internal borders of the EU are becoming increasingly ‘invisible’, and their importance is diminishing. Although the process of European integration is very advanced, it cannot be considered complete and its effects on border areas are determined by the alternating de-bordering and re-bordering processes (Decoville & Durand, Citation2019). Similarly, the process of European territorial integration is bringing territories closer together, but this does not follow a uniform pattern everywhere (Medeiros, Citation2018b). In fact, borders in the EU still matter, and their impact on the economic development of border areas remains significant (Bergs, Citation2012; Capello et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018c).

Studies on border regions have been gaining momentum in recent years, particularly in the field of regional studies and regional science (Makkonen & Williams, Citation2016). Research is being conducted into the effect of opening borders and cross-border cooperation on the economic performance of border areas (Basboga, Citation2020; Niebuhr, Citation2004; Petrakos & Topaloglou, Citation2008; Sohn & Licheron, Citation2018; Topaloglou et al., Citation2005). Nonetheless, a throughout investigation of the effect of the increased permeability of national borders within the EU on the process of reducing the asymmetry of economic development in cross-border areas is missing – and thus so are clear-cut findings in this regard (Bergs, Citation2012; Jakubowski, Citation2020). Nor has this question been satisfactorily addressed in the rich literature on regional convergence, motivated by the willingness to understand the relationship between the processes of European (territorial) integration, Cohesion Policy and the evolution of inter- and intra-national inequalities. Works in this regard usually neglect the criterion of near-border location and thus do not explain whether convergence occurs at the level of regions at the interface between EU countries. The issue therefore requires explanation, especially as it is of high importance in the context of the effects of EU Cohesion Policy, which is aimed at a reduction of disproportions in the levels of development of different regions and backwardness of least privileged regions (EU, Citation2012, Art. 174), including cross-border regions.

In light of the above, the primary objective of this article is to investigate the effect of the EU’s policy to reduce barriers that result from the existence of traditional national borders on the process of changing relations at the developmental level of border regions. This process can be described as cross-border real economic convergence (divergence) (further, cross-border convergence/divergence). More specifically, the paper provides evidence on the long-term development of inequalities (asymmetries) among neighbouring border regions in the EU by addressing the following research questions:

Does the level of the asymmetry in economic development of cross-border areas reduce over time?

What is the relationship between the direction and pace of this process and the initial level of imbalance?

Is the evolution of disparities between border areas independent of changes in imbalances between the bordering states in which they are located?

To answer the above questions, this paper employs the Cambridge Econometrics dataset to analyse the evolution of the cross-border regional disparities in 33 pairs of EU border areas for the period 1980–2015. The study uses a relative asymmetry index to compare regional gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (purchasing power standards – PPS) in two neighbouring border regions from different countries. The concepts of σ- and absolute β-convergence are applied. The article contributes to the body of literature by providing further evidence on cross-border economic asymmetries’ trends in Europe over past decades based on the updated data and a large number of case studies. As such, it can also be useful for the implementation of policy tools aiming to foster development of cross-border areas in Europe.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section reviews the literature. The third section describes the materials used and the applied research method. The fourth section gives the results, while the fifth section discusses them by referring to the current state of knowledge. The final section concludes and recommends directions for further studies regarding the problem of cross-border convergence.

2. LITERATURE REVIEW

2.1. The cross-border asymmetry of economic development

Due to their geographical proximity, shared historical experience and cross-border cooperation, many cross-border regions show certain common features (Krätke, Citation1999; Perkmann, Citation2003). Considerably more frequently, however, areas extending over both sides of an international border differ in terms of size, population density, administrative system, culture and language, economic system, and the level of economic development (Holly et al., Citation2003). These differences are shaped by a group of conditions of various character: historical, geographical, socio-cultural, psychological, or related to changes in the permeability and function of the border (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999; Krätke, Citation1999). Irrespective of their type, character and degree of intensity, they have substantial consequences for the prospects of bilateral cooperation and the development of border regions (Clement, Citation1997; Laine, Citation2012). Some of the most evident differences that have a particularly strong effect on shaping cross-border relations and the development of cross-border cooperation relate to the level of economic development (Decoville et al., Citation2013; Durand & Decoville, Citation2020; Sohn, Citation2014).

The issues of differences in the level of economic development of cross-border areas have become the subject of numerous studies. In this literature, the phenomenon is described as economic disparity (Clement, Citation1997; Laine, Citation2012), imbalance (Comerio et al., Citation2021; Decoville et al., Citation2013), discontinuity (Pászto et al., Citation2019) or asymmetry (Decoville et al., Citation2013; Dołzbłasz, Citation2015; Jakubowski, Citation2018, Citation2020; Laine, Citation2012). The term ‘asymmetry’ is usually defined in a negative way as ‘a lack of symmetry’, characterized by ‘correspondence in size, shape, and relative position of parts on opposite sides of a dividing line or median plane or about a centre or axis’ (Merriam-Webster, Citation2020, s.v.). In the case of cross-border regions, the axis is the interstate border. In regional studies and border studies, research on asymmetry ‘rarely refers to any specific understanding, conceptualisation or theoretisation of this category and is used as an equivalent of imbalance’ (Jańczak, Citation2018, p. 513).

The asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border areas generates considerable, although difficult to conclusively assess, consequences. They can become a factor stimulating cross-border functional relations, including cross-border trade (Bergs, Citation2012) and population mobility (Comerio et al., Citation2021; Decoville & Durand, Citation2019). Therefore, they can contribute to the development of both the complementarity of the economic systems of areas located on either side of the border and their synergic development, or lead to the petrification of the existing disproportions (Knippschild & Schmotz, Citation2018; Laine, Citation2012).

The asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border areas can also cause substantial challenges and threats for cross-border socio-economic systems (Agnew, Citation2008; Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999; Sohn, Citation2014). The existing disproportions can constitute a barrier that is difficult to overcome, one limiting the development of advanced forms of cross-border cooperation, the coherence of cross-border regions and cross-border integration (Knippschild & Schmotz, Citation2018; Perkmann, Citation2003). From the perspective of residents of border regions within the EU, economic disparities are perceived as one of the primary border obstacles – next to legal and administrative barriers, language barriers, and difficult physical access (European Commission (EC), Citation2016).

2.2. Borders and economic development

One of the most important factors affecting the course of developmental processes in border regions is their near-border location, traditionally perceived as a source of peripherality in geographical terms that translates into peripherality in socio-economic terms (Hansen, Citation1977). Interest in the impact of borders on socio-economic processes has led to numerous empirical works seeking to capture and measure the so-called ‘border effects’. The first contributions in this scope drew on the theoretical conceptualization proposed by McCallum (Citation1995), employing gravity models to determine the effect of borders on trade flows reduction (Anderson & van Wincoop, Citation2003; Evans, Citation2003). Further developments of this strand of the international trade literature have broadened our understanding of ‘border effects’ by including the impact of different types of barriers and proximities, such as language, culture or business norms (Konya, Citation2006; Rauch, Citation1999). While these studies viewed the negative impact of borders on economic growth in a reduced market, that is, lower demand (Capello et al., Citation2018b), Melitz (Citation2003) turned the spotlight on the supply side, initiating a series of studies on the ‘border effects’ on firm productivity.

Borders and their effects, however, should be perceived in multiple dimensions. Due to their multifaceted nature, they create barriers of differing character (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999), limiting the possibilities of utilizing various growth assets. Based on this assumption, more recent approaches decompose the ‘border effects’ and look at their impact on aggregate economic performance (Capello et al., Citation2018a, Citation2018b, and Citation2018c). The empirical analyses representing this strand of research not only proved that different types of barriers create obstacles for different growth assets, but also linked ‘border effects’ directly to the issue of the development of border areas. According to Capello et al. (Citation2018a), border regions suffer predominantly due to efficiency needs, as due to the proximity of the border and related physical, institutional and socio-cultural obstacles, they are not able to use their resources as efficiently as other regions. Recent research also confirms that among the main factors hampering the economic performance of border regions are existing legal and administrative barriers (Camagni et al., Citation2019), which lay behind the untapped potential due to the inefficient exploitation of regional growth assets (Caragliu, Citation2022).

Although the presence of borders is commonly perceived as a barrier to development, it can also become a potential development factor and source of competitive advantage (Anderson & O’Dowd, Citation1999). Consideration of the ambivalent nature of borders was reflected in the approach proposed by Sohn and Licheron (Citation2018), where the decomposition of ‘border effects’ distinguished between factors that can positively affect regional development and those that may have negative consequences. The condition for revealing the positive developmental factors resulting from the existence of national borders, however, is an increase in their permeability. Only open (Ratti, Citation1993) and integrative borders (Martinez, Citation1994) that show a sufficiently high degree of permeability (such as those within the EU and the Schengen Zone) provide the basis for faster growth due to access to the market and better exploitation of various growth assets.

The assumption that the economic effects of opening borders and integration can accumulate in border regions has contributed to considerably increased interest in the issue of their development in the EU (Niebuhr & Stiller, Citation2002). Niebuhr (Citation2004), following the classical international economics approach to ‘border effects’, evidenced that regions located on internal EU borders achieve above-average integration results (higher economic growth) due to the reduction of border barriers and change in market access. Recently Basboga (Citation2020) showed that opening national borders is correlated with an increase in regional gross value added (GVA) per capita of border regions by 2.7%. The study also indicated the positive effect of cross-border cooperation on the economic growth of areas located along the internal borders of the EU, suggesting the efficiency of EU support for cross-border integration via greater use of the potential of cross-border regions (EC, Citation2017a). Taking a different methodological approach considering the complex nature of borders and their ambivalent impact on development, Sohn and Licheron (Citation2018) suggest that it is the metropolitan areas recently integrated into the EU that enjoy their border setting and benefit most from open borders.

The findings presented in this section generally confirm the thesis that European (territorial) integration and the opening of national borders reduce border obstacles and thus dynamize the economic development of border regions. They do not provide the answer, however, whether and to what degree eliminating barriers resulting from the existence of borders leads to the equalization of the level of economic development of cross-border regions.

Having this in mind, the present study takes a side-step from recent contributions by looking not at the impact of the integration process and the mitigation of ‘border effects’ on the economic growth of border regions, but at the impact of integration on the reduction of existing disparities in the level of development of border areas. The paper merges the studies on border regions with the branch dealing with inter-state and regional convergence. This approach is grounded in the fact that border regions represent special cases where ‘border effects’ are most evident and the potential consequences of integration may be the strongest. As a result, economic convergence within cross-border regions may differ from inter-state convergence.

2.3. Cross-border economic convergence

Studies on the economic effects of integration are most often built on theories of convergence referring to classical and neoclassical theories of international trade (the Ricardian principle of comparative advantage, Solow model, Heckscher–Ohlin–Samuelson model, etc.). According to the theorem of factor price equalization, integration should lead to the reduction of differences in factor prices through the mobility of capital, labour and entrepreneurial resources and thus lead to convergence (Balassa, Citation1961; Barro & Sala-i-Martin, Citation1992; Camagni et al., Citation2020; Solow, Citation1956). Drawing on the expected positive effects of integration on intercountry disparities, at a theoretical level the cross-border economic convergence should also stem from: (1) the enlargement of market size and increase in economies of scale (Niebuhr & Stiller, Citation2004); (2) the increase of cross-border trade through changes in market access and lower transaction costs (Monfort & Nicolini, Citation2000); (3) the labour cost advantage for less advanced border regions and related inflow of the foreign direct investment (FDI) (Casi & Resmini, Citation2014; Petrakos, Citation2000); (4) cross-border spillovers, that is, positive effects of flows from neighbouring countries (Decoville et al., Citation2013; Sohn & Licheron, Citation2018); (5) the diffusion of technological, managerial and organizational knowledge from stronger to weaker border regions through geographical proximity (Camagni et al., Citation2020); and (6) the access of the less developed border regions to the EU Structural Funds (Mohl & Hagen, Citation2010).

The theories do not deny, however, that integration can also contribute to an increase in existing disparities. According to New Economic Geography models, border regions benefit from increasing market access but also face growing competition (Brülhart et al., Citation2004; Cappellano et al., Citation2022). In open cross-border spaces, more advanced border regions may be in a better position to compete, while less favoured ones can turn into their market outlets (Camagni et al., Citation2020; Petrakos et al., Citation2011) or fall into a vicious circle of out-migration, reduced demand and investment, and economic regression according to the cumulative causation argument (Myrdal, Citation1957).

The few empirical studies to date also provide no satisfactory and clear-cut answer regarding the effect of opening borders and economic integration on reducing the developmental disparities between border regions. Building on the theory of the New Economic Geography, Niebuhr (Citation2008) point to the faster income growth in border areas of new member states in comparison with the border areas of countries belonging to the EU since before 2004. This should contribute to the economic cohesion of cross-border areas in the EU-27. Less unambiguous conclusions result from the typology developed by Topaloglou et al. (Citation2005), although they suggested that the border regions of new member states should benefit from EU expansion more than the neighbouring border regions of the EU-15 states. Wassman (Citation2016) showed that EU enlargement generally had no negative effect on the growth of border regions of old member states located at new internal borders, while Sohn and Licheron (Citation2018) proved that the performance of cross-border metropolitan areas in terms of open borders is generally in favour of strengthening cross-border disparities rather than lessening them.

Based on the theoretical expectations presented in this section, we assume that European (territorial) integration results in a decrease in the level of the sealedness of national borders, and in an increase in cross-border relations, which should lead to the reduction of disproportions (asymmetry) in the economic development of cross-border regions at the European scale. Therefore, we may hypothesize the following:

Hypothesis 1: EU cross-border areas are subject to the phenomenon of cross-border σ-convergence observed for the relative asymmetry index.

Hypothesis 2: EU cross-border areas are subject to the phenomenon of absolute cross-border β-convergence observed for the relative asymmetry index.

Hypothesis 3: The convergence in cross-border regions (cross-border convergence) observed for the relative convergence index occurs faster than at the scale of countries in which such regions are located.

3. EXAMINING CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIC CONVERGENCE: DATA AND METHODS

The study covered cross-border regions at internal EU borders so designated based on statistical units NUTS-3 adjacent to a national border. Only land borders were taken into account, given the much weaker impact of border and scale of cross-border relations in the case of marine borders. NUTS-3 units that share a border with more than one region in another EU country have been considered as parts of two or more border areas, according to their status. The analyses excluded cross-border areas covering Luxembourg due to its specific character (NUTS-3 unit constituting the core of a large metropolitan area with an impact considerably exceeding the territory of the country). The analysis eventually covered 33 cross-border areas within the EU, including 66 border regions. The study covered changes in the level of the economic development of these border regions from 1980 to 2015, each time for the current range of the European Communities and EU, expanding the coverage of the studied cross-border regions in accordance with subsequent stages of the process of EU enlargement. Such a time framework allowed us to take better account of a wide scope of developments (among them six processes of EU enlargement) and the benefits of European (territorial) integration in the long-run without limiting the effects of EU support for the development of cross-border cooperation associated with the introduction of the INTERREG-A programme in 1990.

Data on GDP (in nominal terms, constant prices from 2005) and population size for NUTS-3 units used in the study were obtained from the European Regional Database (European Commission – Joint Research Centre & Cambridge Econometrics, Citation2018). The obtained results were converted based on purchasing power parity (PPP) conversion rates and historical national currency exchange rates (Eurostat, Citation2020; International Monetary Fund (IMF), Citation2020; Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), Citation2020). There is some criticism towards GDP per capita as a measure, which is insufficient to capture the multidimensional nature of regional development. However, its numerous advantages, such as universality, relative ease of interpretation, relative comparability in time and space, and availability of data in long time series, make it the most popular measure used in similar studies.

The basis for the analysis of cross-border convergence in the study is the index of relative asymmetry of economic development (DI) comparing the level of regional GDP per capita (PPS) in two neighbouring border regions from different countries. It reflects the disproportion in the level of the economic development of the border region of one country against the neighbouring region of another. It is calculated as the absolute difference of GDP per capita in both regions referred to the sum of those values (additionally multiplied by 100). Taking into account the total GDP per capita of both regions in the denominator permits the standardization and comparability of the index values across cross-border systems in relative terms also in the case of the high disproportion of the economic potential of regions. The use of the asymmetry index results from the general inspiration over the approach of Bergs (Citation2012). The applied formula is approximate to the formula for the adjusted mean absolute percentage error (AMAPE) applied to the assessment of quality of forecasts. Similar measures of asymmetry are widely used in medical research (Wu & Wu, Citation2015). The formula for the relative asymmetry index in the pair of neighbouring regions i and j is described as follows:

(1)

(1) where yi is GDP per capita value (PPS) for border region i; and yj is the analogous value for the neighbouring border region j. The index is calculated for each pair of border regions located in different EU states.

The analysis of the occurrence of cross-border σ-convergence, that is, the reduction of the level of relative asymmetry of economic development of cross-border regions with time, is based on the following trend model:

(2)

(2) where:

(3)

(3) and

is the average value of the relative asymmetry index calculated for all the analysed pairs of border regions in period t. A negative and statistically significant coefficient

will denote the occurrence of cross-border convergence; a positive and statistically significant coefficient

will point to the occurrence of divergence; and a not statistically significant estimate means lack of convergence and divergence.

The analysis of (absolute) cross-border β-convergence aims to capture dependencies between the rate of economic growth and the level of wealth in the initial year. It is based on the assumption that the GDP per capita growth rate in less developed countries should be higher than the GDP per capita growth rate in better developed ones, leading to gradual equalization of their level of development. The process should be reflected through the reduction of values of the analysed relative asymmetry index. The investigation of the occurrence of absolute cross-border β-convergence for the relative asymmetry index employed the following formula:

(4)

(4) where

is the value of the index of relative asymmetry of economic development for the pair of border regions i and j in year t; and

is the value of the analogous index in the initial year of the analysis. A negative and statistically significant coefficient β will denote the occurrence of cross-border convergence; a positive and statistically significant coefficient β will point to the occurrence of divergence; and a not statistically significant estimate means lack of convergence and divergence. However, a negative coefficient β could indicate that the increase in the difference of GDP per capita between two border regions is smaller for those region pairs that show a large initial difference in GDP per capita. At the same time, the differences between all border regions might increase. This should not be called convergence. To avoid incorrect reasoning about convergence, one should make sure that the dependent variable (change of the relative asymmetry index) takes negative values at least for some border regions. Therefore, when discussing the results of estimation of equation (4), we report the share of negative values of the dependent variable.

Moreover, the relationship was analysed between the average annual rate of changes in the index of relative asymmetry of the economic development of border regions and the rate of changes of the analogous index calculated at the national level (equation 5). The inspiration for this part of the analysis was the one-factor capital asset pricing model (CAPM) used in finance for modelling the relationship between returns of a selected stock and returns of a broad market portfolio:

(5)

(5) where

and

have analogous meaning as above; and

is the value of the index of relative asymmetry of economic development calculated at the national level for a pair of countries i and j in year t; and

is the value of the analogous index in the initial year. In the above model, coefficient

shows the degree to which cross-border convergence is related to convergence at the national level. A coefficient above (below) one will mean that convergence in border regions occurs faster (slower) than at the level of countries in which the regions are located. A statistically significant value of coefficient

will show what part of changes in the asymmetry index in border regions is intrinsic – independent from the convergence of the level of development between the countries.

4. CROSS-BORDER ECONOMIC CONVERGENCE: RESULTS OF THE EMPIRICAL STUDY

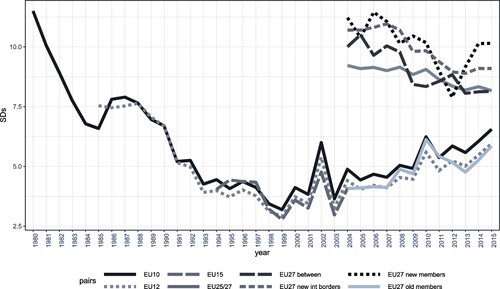

The first stage of the analysis was the investigation of disproportions in relative asymmetry index values in time (cross-border σ-convergence). The results of the analysis for the period 1980–2015 are presented in . The results of the estimation of equation (2) concerning the trend analysis for σ-convergence in different spatial scales – covering border regions in different groups of EU states, and temporal scales – covering subsequent stages of EU expansion are presented in .

Figure 1. Standard deviation of the relative asymmetry index in the period 1980–2015 in different spatial scales.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on the European Regional Database Citation2017 (European Commission – Joint Research Centre & Cambridge Econometrics, Citation2018).

Table 1. Results of the analysis of σ-convergence of the relative asymmetry index by enlargements of the EU.

The analysis of subsequent stages of EU enlargement shows that in the period 1980–85, among the EU-10 states, disproportions in the wealth of cross-border regions plainly decreased. The trend was maintained, and even slightly intensified, also after the accession of Spain and Portugal to the EU (1985–94). It was, however, the last period of decreasing disproportions at the scale of all pairs of EU cross-border regions. In the period 1994–2004, cross-border inequalities stabilized, and in the period 2004–15 it started to increase again. The obtained results prove, however, that the phenomenon of opening borders generally contributed to faster convergence. In the period 1985–94, cross-border σ-convergence in the scope including ‘new’ states (EU-12) was (slightly) faster than in the EU-10. Also in the period 2004–15, despite the lack of convergence in border regions of the old EU states (irrespective of the considered scope – EU-10, EU-12, EU-15), the phenomenon of convergence occurred in the group of cross-border regions covering new member states (EU-27).

More detailed analyses for the period after 2004 and a group of cross-border areas of the EU-27 indicate that the newly opened borders contributed to the reduction of cross-border differences in the level of wealth (EU-27 new internal borders). The phenomenon of reducing cross-border asymmetry was moreover demonstrably stronger on borders between old and new member states (EU-27 between), although it also occurred on borders between new member states (EU-27 new members). In the case of borders between old EU states (EU-27 old members), throughout the period 2004–15, divergence occurred. Regressions for the 2004–08 and 2008–15 sub-periods to capture the effect of the 2008 economic crisis do not provide statistically significant results.

Another stage of the analysis was verification of the relationship between the rate of changes in values of the relative asymmetry index and its initial value, that is, application of the analysis of absolute cross-border β-convergence. The results of the estimation of equation (4) in analogous spatial and temporal scales as for σ-convergence are presented in . In addition, as discussed above in each case, the share of the negative values of the dependent variable is reported.

Table 2. Results of the analysis of absolute β-convergence of the relative asymmetry index by enlargements of the EU.

Conclusions from the analysis of absolute β-convergence are analogous to observations based on the analysis of the measure of dispersion in cross-border systems. According to the analysis of subsequent stages of EU expansion, in the initial years 1980–85, disproportions in the wealth of cross-border regions decreased among EU-10 states. This trend was maintained also after the EU’s expansion to Spain and Portugal (1985–94), and for the EU-15 also after another expansion in the period 1994–2004. The results of the analysis of β-convergence confirm that the phenomenon of opening borders contributed to faster convergence. In the period 1985–94, cross-border convergence in the context considering new states (EU-12) was (slightly) higher than in the old EU-10. In the period 1994–2004 in cross-border regions of the EU-10 and EU-12, differences in wealth of cross-border regions were stable, but after including the new states, cross-border convergence occurred within the EU-15. Analogously, in the period 2004–15, despite a lack of convergence in the border regions of the old EU states (irrespective of the situation – EU-10, EU-12, EU-15), the phenomenon occurred in a group of cross-border regions including new member states (EU-27). The results are illustrated in .

Figure 2. Asymmetry and cross-border convergence in the EU in 1980–85, 1985–94, 1994–2004 and 2004–15.

Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on European Regional Database Citation2017 (European Commission – Joint Research Centre & Cambridge Econometrics, Citation2018).

The last part of shows more detailed analyses for the period after 2004 and the group of border regions of the EU-27. They show that the newly opened borders contributed to the reduction of cross-border differences in wealth (convergence on EU-27 new internal borders). The regressions for cross-border regions between the old and new (EU-27 between), and between new EU states (EU-27 new members) show the expected negative sign, but are statistically insignificant, probably due to the small sample. In the case of borders between old EU member states (EU-27 old members), throughout the period 2004–15, neither convergence nor divergence occurred.

The last stage of the analysis aimed at the investigation of the relationship of the rate of cross-border convergence with the rate of convergence between states in which the compared cross-border regions are located. The results of the estimation of the additional model described with equation (5) are presented in . In order to facilitate the interpretation of results, the comparison includes values of the β-coefficient showing the occurrence of absolute cross-border convergence or divergence (cf. ).

Table 3. Results of the estimation of the model explaining the rate of changes in the relative asymmetry index in border regions by means of rate of changes in the analogical index at the national level.

The analysis results show that cross-border convergence (divergence), if it occurs, is either equally fast or slower than convergence at the national level (β-coefficient from the CAPM model such as in the majority of cases is not statistically different from 1, and when different it is lower than 1). The lack of significant difference from 1 is partially caused by small sample sizes. There are, however, cases with a coefficient higher than 1. The largest value is observed for a group of cross-border regions between new and old member states (EU-27 between) in the period 2004–15 (coefficient of 1.217). This result reflects a positive effect of opening borders between the old and new EU states. The correlation between cross-border and national convergence for EU-27 states was also relatively strong in the period 2004–15 on new internal borders, and on borders between new member states. In these cases, the value of the coefficient was at 0.903 and 0.751, respectively, that is, lower than at the national level.

5. DISCUSSION

Earlier papers have pointed to the positive effect of the process of opening national borders on the economic growth of border regions (Basboga, Citation2020; Bergs, Citation2012; Niebuhr, Citation2004, Citation2008). What remained unclear was the effect of eliminating barriers resulting from the existence of traditional borders on the process of overcoming the asymmetrical economic development of cross-border areas and dynamizing the development of less developed border regions vis-à-vis their better developed neighbours. In order to investigate this phenomenon, the study involved analysis of EU cross-border regions in terms of the occurrence of cross-border σ- and absolute β-convergence in the period 1980–2015 based on the value of the index of relative asymmetry of economic development (DI) comparing the level of regional GDP per capita (PPS) in two neighbouring border regions from different countries.

The obtained results generally remain in line with theoretical expectations. They confirm the occurrence of cross-border σ- and absolute β-convergence in cross-border regions in the EU (earlier European Communities), and allow for associating the phenomenon with the process of European (territorial) integration, including the binding of the four freedoms of the Common Market and regime of the Schengen Zone (Niebuhr, Citation2008). The study primarily permitted positive verification of Hypothesis 1. In the context of the obtained results, cross-border σ-convergence was observed at least from the beginning of the 1980s until the mid-1990s, leading to considerable reduction of the development disproportions and an increase in the coherence of cross-border regions in the economic dimension. The fourth EU enlargement to three highly developed states (Austria, Sweden and Finland) commenced almost a decade of slowing down this process. Cross-border convergence in the EU intensified due to the greatest enlargement in 2004 to states characterized by a significantly lower level of GDP per capita than in the EU-15. From that moment on – and particularly from 2008 (global economic crisis, enlargement of the Schengen Zone) – an evident division occurred into cross-border regions located at old and new EU internal borders, and cross-border convergence was primarily observed on borders between new and old EU member states (catch-up effect).

Hypothesis 2 was also verified positively. Absolute β-convergence occurred in all periods corresponding with subsequent EC/EU enlargements in the group of all cross-border regions included in the EC/EU in a given period. Slowing down the convergence processes, or even the appearance of a trend for divergence in cross-border regions between old member states primarily results from the fact that the majority of regions on EU-15 internal borders have achieved a considerable level of economic cohesion over the last several decades (Jakubowski, Citation2020). Therefore, further convergence is more difficult to achieve, and sometimes impossible.

Convergence (divergence) processes in EU cross-border regions are, however, a phenomenon diverse in both spatial and temporal terms. The situation is caused by the heterogeneity of the space itself, as well as by the different degrees to which regions submit to the effect of economic integration (Konecka-Szydłowska et al., Citation2019). Therefore, the direction and intensity of convergence (divergence) in particular cross-border regions and in different periods remain dependent on the context – geographical conditions (Topaloglou et al., Citation2005), history of mutual relations, degree of advancement of bilateral cooperation, structure of the economy or the existing barriers (Camagni et al., Citation2019; Capello et al., Citation2018c). The dynamization of the development of less developed border regions, however, is certainly not a consequence of only market forces. As pointed out by Decoville et al. (Citation2013, p. 222), ‘the development of cross-border regions shows that the relationship between interactions and convergence is far from being automatic’. According to Topaloglou et al. (Citation2005), it primarily depends on the balance and synergy between the market dynamics and public intervention, supporting relevant factors of development under the influence of integration processes. It therefore appears that the positive effect of the opening of borders on cross-border convergence occurs mainly in the short and medium terms. As strong interactions between border regions are an insufficient condition for the process of cross-border convergence (Decoville et al., Citation2013; Sohn, Citation2014) in strongly integrated cross-border areas it may depend in the long-run on a model of cross-border integration. According to Sohn (Citation2014, p. 587), integration based ‘on the mobilization of the border as a differential benefit’ that ‘aims to generate value out of asymmetric cross-border interactions’ (co called ‘geo-economic model’) probably contributes to an increase in cross-border disparities. The second model, called the ‘territorial project’, is based on the logic of ‘cross-border hybridization’ and may lead to the comprehensive convergence of areas located on either side of a border (Sohn, Citation2014).

The economic strength of the region on the other side of the border is also of importance, confirming the significance of ‘who neighbours whom’ (Basboga, Citation2020). The research results reveal that cross-border convergence primarily occurs when and where border regions show considerable disproportions in the level of development (asymmetry). The effect of opening borders itself and the related convergence process is subject to gradual phasing out, and with time to a progressing reduction of disproportions in the level of economic development and increase in cross-border economic cohesion. Therefore, cross-border convergence in the EU is observed particularly in the period of the first several to dozen years from the moment of opening borders (accession to the EU), and its rate is especially high on the borders of new member states.

The study did not permit positive verification of Hypothesis 3. In the context of the obtained results, cross-border convergence generally occurred more slowly than inter-state convergence. This may result from the existing differences in the level of developmental disproportions at the level of countries and cross-border regions. On the internal borders of old member states, the relative diversification of the level of economic development between countries was usually (considerably) lower throughout the analysed period than between cross-border regions. Nonetheless, the rate of inter-state convergence was generally faster than cross-border convergence. This means that the positive effects of European (territorial) integration contributed to a greater extent to the reduction of developmental disproportions at the level of countries. Therefore – despite the occurrence of the actual cross-border convergence – petrification occurred, or even intensification of the peripheral status of border regions in less developed countries. After 2004, the situation on the internal borders in the group of new EU member states was similar. The obtained results therefore suggest the general economic weakness of cross-border regions, and their peripherality. According to the Seventh Report on Economic and Social Cohesion (EC, Citation2017b), convergence in the EU occurs mainly at the inter-state level, and polarization is observed at the regional level, primarily due to the dynamic growth of capital regions and metropolitan areas. Because the growth of border regions is generally slower than at the national level, so is the rate of cross-border convergence. The obtained results may stem from the fact that border barriers are after all stronger, and the benefits of opening borders is lower than we expected.

In this context, cross-border areas between old and new EU member states stand out. In that group, the level of the relative asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border regions was generally (considerably) lower than at the level of neighbouring states. Cross-border convergence also occurred faster here than inter-state convergence. This suggests that less developed border regions in this group (located in new EU member states) benefitted from the proximity of the EU ‘Core’ and the existing comparative advantages of the neighbouring regions of the old EU members. Such an observation confirms the earlier presumptions of Topaloglou et al. (Citation2005) that the new member states’ border regions bordering the old member states should be the main winners of the integration process.

To sum up this part of the discussion, cross-border convergence does occur in the area of the EU, but it corresponds to a broader context of more general patterns of regional development in the EU, including the economic shift from the old core countries to new member states, and the catch up effect between regions of Central and Eastern Europe and the EU-15 states. Cross-border convergence also generally occurs more slowly than the analogous process at the level of countries, pointing to the maintained negative consequences of the so-called ‘border effect’ on the growth of border regions.

The above findings are of high importance from the point of view of programming and implementing the Cohesion Policy and supporting the development of cross-border cooperation. On the one hand, the asymmetry of the socio-economic development of cross-border regions is a factor substantially limiting the possibilities of cross-border cooperation (EC, Citation2016). On the other hand, cross-border cooperation is a necessary condition and one of the basic tools for overcoming asymmetry, and a tool compensating for ‘the border effect’ (Basboga, Citation2020). According to Mykhnenko and Wolff (Citation2019), the considerable progress of the EU in the scope of convergence results not only from free market forces, but also active regional policy, directing assistance to regions lagging behind. Therefore, pursuant to the suggestion of Wassman (Citation2016), regional policies accompanying economic integration in cross-border regions should aim at territorially oriented solutions, considering the specificity of particular regions, and at maximizing sustainable use of the territorial capital of neighbouring border regions. Therefore, further efforts are necessary, not only towards reducing border barriers and development of cross-border cooperation, but also support of more balanced regional development of cross-border regions, pursuant to the assumptions of the document Boosting Growth and Cohesion in EU Border Regions (EC, Citation2017a) and Territorial Agenda 2030 (Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community of Germany, Citation2020).

6. CONCLUSIONS

The asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border regions revealed in the context of European (territorial) integration processes becomes a source of both opportunities and challenges and threats. The phenomenon affects many spheres of socio-economic life. Therefore, its consequences in various spheres can be simultaneously positive and negative. Asymmetry is also a dynamic phenomenon. This means that its level changes depending on the set of internal and external factors. On the one hand, the main theories and scientific debates on European (territorial) integration point to the positive effects of integration and the advantages for less developed regions, of which border regions. On the other hand, empirical studies prove that in the EU ‘disparities continuously reappear in different forms and spatial levels, transmitting a sense of inescapable normality’ (Camagni et al., Citation2020, p. 131).

These research results shed new light on the issue of the effect of European (territorial) integration on the economic development of border regions in the long-run (1980–2015) through answering the question whether the process also involves reduction of disproportions of economic development in cross-border arrangements. The results obtained confirm the occurrence of cross-border economic convergence (both σ- and absolute β-convergence), especially in the first few years of EC/EU membership. However, the positive effect of open borders on cross-border convergence is reduced over time. In the long term, disparities in the level of development of cross-border areas may increase again, even if they were already decreasing for several years. The results obtained also suggest that cross-border convergence generally progresses slower than convergence at the international level.

It is necessary to point out that the conclusions of this work must be assessed in the light of its limitations that likewise offer opportunities for new research work. First, the preliminary analysis of cross-border convergence for particular multiannual financial frameworks of the EU points to different effects of public intervention in the scope of particular EU budgets on the Cohesion Policy, and of particular editions of the Interreg programme on the processes of reducing the development disproportions of cross-border regions. This issue requires further research.

Second, the limitations of the available resources have meant that the analysis has been restricted to the GDP per capita as a measure of the wealth of regions. The proposed methodology based on the index of relative asymmetry allows, however, examining cross-border disparities and convergence also in other main territorial development dimensions, providing a more complete picture on the cross-border development asymmetries trends in Europe. Therefore, it appears reasonable to extend the conducted research using other measures of development.

Finally, the study provides a reference point for further quantitative and qualitative research on the economic development of cross-border regions in terms of regional studies and regional science, as well as border studies, in the scope of analyses of conditional cross-border economic β-convergence. Therefore, more thorough research is also required regarding the issue of the dependencies of the processes of cross-border convergence on diverse geographical, historical, structural or cultural factors.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors are grateful for the helpful comments provided by the three anonymous reviewers and editor.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- Agnew, J. (2008). Borders on the mind: Re-framing border thinking. Ethics & Global Politics, 1(4), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3402/egp.v1i4.1892

- Anderson, J. E., & van Wincoop, E. (2003). Gravity with gravitas: A solution to the border puzzle. American Economic Review, 93(1), 170–192. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803321455214

- Anderson, J., & O’Dowd, L. (1999). Borders, border regions and territoriality: Contradictory meanings, changing significance. Regional Studies, 33(7), 593–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078648

- Anderson, J., O’Dowd, L., & Wilson, T. M. (Eds.). (2003). New borders for a changing Europe: Cross-border cooperation and governance. Routledge.

- Balassa, B. (1961). Towards a theory of economic integration. Kyklos, 14(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6435.1961.tb02365.x

- Barro, R. J., & Sala-i-Martin, X. (1992). Convergence. Journal of Political Economy, 100(2), 223–251. https://doi.org/10.1086/261816

- Basboga, K. (2020). The role of open borders and cross-border cooperation in regional growth across Europe. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 7(1), 532–549. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2020.1842800

- Bergs, R. (2012). Cross-border cooperation, regional disparities and integration of markets in the EU. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 27(3), 345–363. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2012.751710

- Brülhart, M., Crozet, M., & Koenig, P. (2004). Enlargement and the EU periphery: The impact of changing market potential. The World Economy, 27(6), 853–875. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2004.00632.x

- Camagni, R., Capello, R., & Caragliu, A. (2019). Measuring the impact of legal and administrative international barriers on regional growth. Regional Science Policy & Practice, 11(2), 345–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/rsp3.12195

- Camagni, R., Capello, R., Cerisola, S., & Fratesi, U. (2020). Fighting gravity: Institutional changes and regional disparities in the EU. Economic Geography, 96(2), 108–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2020.1717943

- Capello, R., Caragliu, A., & Fratesi, U. (2018a). Measuring border effects in European cross-border regions. Regional Studies, 52(7), 986–996. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1364843

- Capello, R., Caragliu, A., & Fratesi, U. (2018b). Compensation modes of border effects in cross-border regions. Journal of Regional Science, 58(4), 759–785. https://doi.org/10.1111/jors.12386

- Capello, R., Caragliu, A., & Fratesi, U. (2018c). Breaking down the border: Physical, institutional and cultural obstacles. Economic Geography, 94(5), 485–513. https://doi.org/10.1080/00130095.2018.1444988

- Cappellano, F., Makkonen, T., Kaisto, V., & Sohn, C. (2022). Bringing borders back into cross-border regional innovation systems: Functions and dynamics. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 54(5), 1005–1021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X221073987

- Caragliu, A. (2022). Better together: Untapped potentials in Central Europe. Papers in Regional Science, 101(5), 1051–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12690

- Casi, L., & Resmini, L. (2014). Spatial complexity and interactions in the FDI attractiveness of regions. Papers in Regional Science, 93, S51–S78. https://doi.org/10.1111/pirs.12100

- Clement, N. (1997). The changing economics of international borders and border regions. In P. Ganster, A. Sweedler, J. W. Scott, & W.-D. Eberwein (Eds.), Borders and border regions in Europe and North America (pp. 47–63). San Diego University Press, Institute for Regional Studies of the Californias.

- Comerio, N., Minelli, E., Sottrici, F., & Torchia, E. (2021). Cross-border commuters: How to segment them? A framework of analysis. International Migration, 59(1), 74–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/imig.12720

- Decoville, A., & Durand, F. (2019). Exploring cross-border integration in Europe: How do populations cross borders and perceive their neighbours? European Urban and Regional Studies, 26(2), 134–157. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776418756934

- Decoville, A., Durand, F., Sohn, C., & Walther, O. (2013). Comparing cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: Towards a functional typology. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 28(2), 221–237. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2013.854654

- Dołzbłasz, S. (2015). Symmetry or asymmetry? Cross-border openness of service providers in Polish–Czech and Polish–German border towns. Moravian Geographical Reports, 23(1), 2–12. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2015-0001

- Durand, F., & Decoville, A. (2020). A multidimensional measurement of the integration between European border regions. Journal of European Integration, 42(2), 163–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2019.1657857

- Durand, F., Decoville, A., & Knippschild, R. (2020). Everything all right at the internal EU borders? The ambivalent effects of cross-border integration and the rise of Euroscepticism. Geopolitics, 25(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2017.1382475

- European Commission (EC). (2016). Overcoming obstacles in border regions, summary report on the online public consultation on border obstacles.

- European Commission (EC). (2017a). Boosting growth and cohesion in EU border regions, communication from the commission to the council and the European parliament (COM(2017) 534 final).

- European Commission (EC). (2017b). Seventh report on economic, social and territorial cohesion.

- European Commission – Joint Research Centre & Cambridge Econometrics. European Regional Database 2017. (2018). http://urban.jrc.ec.europa.eu/t-pedia/#/

- European Union. (2012). Treaty on European Union and the treaty on the functioning of the European Union. Official Journal, C 326, 26 October, P. 0001-0390. European Union. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=celex%3A12012E%2FTXT

- Eurostat. (2020). Eurostat database. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/data/database

- Evans, C. L. (2003). The economic significance of national border effects. American Economic Review, 93(4), 1291–1312. https://doi.org/10.1257/000282803769206304

- Federal Ministry of the Interior, Building and Community of Germany. (2020). Territorial Agenda 2030: A Future for All Places. https://www.territorialagenda.eu/files/agenda_theme/agenda_data/Revisions%20-%20Draft%20documens/TerritorialAgenda2030_201201.pdf

- Hansen, N. (1977). Border regions: A critique of spatial theory and a European case study. The Annals of Regional Science, 11(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01287245

- Hiepel, C. (2016). ‘Borders are the scars of history’? Cross-border co-operation in Europe – The example of the EUREGIO. Journal of European Integration History, 22(2), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.5771/0947-9511-2016-2-263

- Holly, W., Nekvapil, J., Scherm, I., & Tiserova, P. (2003). Unequal neighbours: Coping with asymmetries. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 29(5), 819–834. https://doi.org/10.1080/1369183032000149587

- International Monetary Fund (IMF). (2020). Implied PPP conversion rate.

- Jakubowski, A. (2018). Asymmetry of economic development of cross-border areas in the context of perception of near-border location. Barometr Regionalny. Analizy i Prognozy, 16(2), 123–131. https://doi.org/10.56583/br.373

- Jakubowski, A. (2020). Asymmetry of the economic development of cross-border areas in the European Union: Assessment and typology. Europa XXI, 39, 45–62. https://doi.org/10.7163/Eu21.2020.39.6

- Jańczak, J. (2018). Symmetries, asymmetries and cross-border cooperation on the German–Polish border. Towards a new model of (de)bordering. Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(3), 509–527. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.518

- Knippschild, R., & Schmotz, A. (2018). Border regions as disturbed functional areas: Analyses on cross-border interrelations and quality of life along the German–Polish border. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 33(3), 371–391. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2016.1195703

- Kolosov, V., & Więckowski, M. (2018). Border changes in Central and Eastern Europe: An introduction. Geographia Polonica, 91(1), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.7163/GPol.0106

- Konecka-Szydłowska, B., Churski, P., Herodowicz, T., & Perdał, R. (2019). Europejski kontekst wpływu współczesnych megatrendów na rozwój społeczno-gospodarczy. Ujęcie syntetyczne [The European context of the impact of contemporary megatrends on socio-economic development. A synthetic approach]. Przegląd Geograficzny, 91(2), 39–59. https://doi.org/10.7163/PrzG.2019.2.3

- Konya, I. (2006). Modeling cultural barriers in international trade. Review of International Economics, 14(3), 494–507. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9396.2006.00626.x

- Krätke, S. (1999). Regional integration or fragmentation? The German-Polish border region in a New Europe. Regional Studies, 33(7), 631–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343409950078675

- Laine, J. (2012). Border paradox: Striking a balance between access and control in asymmetrical border settings. Eurasia Border Review, 3(1), 51–79.

- Makkonen, T., & Williams, A. M. (2016). Border region studies: The structure of an ‘offbeat’ field of regional studies. Regional Studies, Regional Science, 3(1), 355–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/21681376.2016.1209982

- Martinez, O. J. (1994). The dynamics of border interaction. New approaches to border analysis. In C. Schofield (Ed.), Global boundaries I: World boundaries. Routledge.

- McCallum, J. (1995). National borders matter: Canada–U.S. regional trade patterns. American Economic Review, 85(3), 615–623.

- Medeiros, E. (2018a). The role of European territorial cooperation (ETC) in EU cohesion policy. In E. Medeiros (Ed.), European territorial cooperation. Theoretical and empirical approaches to the process and impacts of cross-border and transnational cooperation in Europe (pp. 467–491). Springer.

- Medeiros, E. (2018b). Should EU cross-border cooperation programmes focus mainly on reducing border obstacles? Documents d’Anàlisi Geogràfica, 64(3), 467. https://doi.org/10.5565/rev/dag.517

- Medeiros, E., Ramírez, M. G., Dellagiacoma, C., & Brustia, G. (2022). Will reducing border barriers via the EU’s b-solutions lead towards greater European territorial integration? Regional Studies, 56(3), 504–517. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2021.1912724

- Melitz, M. J. (2003). The impact of trade on intra-industry reallocations and aggregate industry productivity. Econometrica, 71(6), 1695–1725. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0262.00467

- Merriam-Webster. (2020). Asymmetry. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/asymmetry

- Mohl, P., & Hagen, T. (2010). Do EU structural funds promote regional growth? New evidence from various panel data approaches. Regional Science and Urban Economics, 40(5), 353–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.regsciurbeco.2010.03.005

- Monfort, P., & Nicolini, R. (2000). Regional convergence and international integration. Journal of Urban Economics, 48(2), 286–306. https://doi.org/10.1006/juec.1999.2167

- Mykhnenko, V., & Wolff, M. (2019). State rescaling and economic convergence. Regional Studies, 53(4), 462–477. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2018.1476754

- Myrdal, G. (1957). Economic theory and underdeveloped regions. University Paperbacks.

- Nelles, J., & Walther, O. (2011). Changing European borders: From separation to interface? An introduction. Articulo, 6. https://doi.org/10.4000/articulo.1658

- Niebuhr, A. (2004). Spatial effects of European integration: Do border regions benefit above average? (discussion Paper). Hamburg Institute of International Economics (HWWA).

- Niebuhr, A. (2008). The impact of EU enlargement on European border regions. International Journal of Public Policy, 3(3/4), 163. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2008.019065

- Niebuhr, A., & Stiller, S. (2002). Integration effects in border regions – A survey of economic theory and empirical studies (Discussion Paper No. 179). Hamburg Institute of International Economics (HWWA).

- Niebuhr, A., & Stiller, S. (2004). Integration effects in border regions – A survey of economic theory and empirical studies. Review of Regional Research, 24, 3–21.

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2020). PPPs and exchange rates. https://stats.oecd.org/OECDStat_Metadata/ShowMetadata.ashx?Dataset=SNA_TABLE4&ShowOnWeb=true&Lang=en

- Pászto, V., Macků, K., Burian, J., Pánek, J., & Tuček, P. (2019). Capturing cross-border continuity: The case of the Czech–Polish borderland. Moravian Geographical Reports, 27(2), 122–138. https://doi.org/10.2478/mgr-2019-0010

- Perkmann, M. (2003). Cross-border regions in Europe: Significance and drivers of regional cross-border cooperation. European Urban and Regional Studies, 10(2), 153–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776403010002004

- Petrakos, G. (2000). The spatial impact of East–West integration in Europe. In G. Petrakos, G. Maier, & G. Gorzelak (Eds.), Integration and transition in Europe: The economic geography of interaction (pp. 38–68). Routledge.

- Petrakos, G., Kallioras, D., & Anagnostou, A. (2011). Regional convergence and growth in Europe: Understanding patterns and determinants. European Urban and Regional Studies, 18(4), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776411407809

- Petrakos, G., & Topaloglou, L. (2008). Economic geography and European integration: The effects on the EU’s external border regions. International Journal of Public Policy, 3(3/4), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPP.2008.019064

- Ratti, R. (1993). Spatial and economic effect of frontiers. Overview of traditional and new approaches and theories of border area development. In R. Ratti & S. Reichmann (Eds.), Theory and practice of transborder cooperation (pp. 23–53). Helbing & Lichtenhahn.

- Rauch, J. E. (1999). Networks versus markets in international trade. Journal of International Economics, 48(1), 7–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0022-1996(98)00009-9

- Rietveld, P. (2012). Barrier effects of borders: Implications for border crossing infrastructures. European Journal of Transport and Infrastructure Research, 12(2), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.18757/EJTIR.2012.12.2.2959

- Sohn, C. (2014). Modelling cross-border integration: The role of borders as a resource. Geopolitics, 19(3), 587–608. https://doi.org/10.1080/14650045.2014.913029

- Sohn, C., & Licheron, J. (2018). The multiple effects of borders on metropolitan functions in Europe. Regional Studies, 52(11), 1512–1524. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2017.1410537

- Sohn, C., & Reitel, B. (2016). The role of national states in the construction of cross-border metropolitan regions in Europe: A scalar approach. European Urban and Regional Studies, 23(3), 306–321. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969776413512138

- Sohn, C., Reitel, B., & Walther, O. (2009). Cross-border metropolitan integration in Europe: The case of Luxembourg, Basel, and Geneva. Environment and Planning C: Government and Policy, 27(5), 922–939. https://doi.org/10.1068/c0893r

- Solow, R. M. (1956). A contribution to the theory of economic growth. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 70(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

- Topaloglou, L., Kallioras, D., Manetos, P., & Petrakos, G. (2005). A border regions typology in the enlarged European Union. Journal of Borderlands Studies, 20(2), 67–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865655.2005.9695644

- Wassman, P. (2016). The economic effects of the EU eastern enlargement on border regions in the old member states (Hannover Economic Papers No. 582). Leibniz Universität Hannover.

- Wu, J., & Wu, B. (2015). The novel quantitative technique for assessment of gait symmetry using advanced statistical learning algorithm. BioMed Research International, 2015, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/528971

- Zielonka, J. (2017). The remaking of the EU’s borders and the images of European architecture. Journal of European Integration, 39(5), 641–656. https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2017.1332059