ABSTRACT

We explore the making, unmaking and remaking of social infrastructure (SI) in ‘left-behind places’ (LBPs) through a case study a former mining village in northern England. We address the understudied affective dimensions of ‘left-behindness’. Seeking to move beyond a narrowly economistic of reading LBPs, our framework: strongly emphasises the importance of place attachments and the consequences of their disruption; considers LBPs as ‘moral communities’, seeing the making of SI as an expression of this; views the unmaking of SI through the lens of ‘root shock’; and explains efforts at remaking SI in terms of the articulation of ‘radical hope’.

1. INTRODUCTION

This paper develops a framework for understanding the making, unmaking and remaking of social infrastructure (SI) in ‘left-behind places’ (LBPs). While acknowledging its limitations as a descriptor, Pike et al. (Citation2023) suggest the term ‘left-behind places’ at least promises a modification of our understanding of longstanding geographical inequalities because it implies, first, a relational and agency-sensitive understanding of geographically uneven development; second, a reframing of the problem beyond solely economic considerations; and, finally, a re-evaluation of what we mean by ‘development’ when the economy grows but some places are ‘left-behind’ (see also MacKinnon et al., Citation2022). In particular, they identify how the discourse of LBPs links established economic concerns to questions of place attachment and belonging. Residents feel ‘left behind’ and express this feeling in terms of abandonment or neglect, fuelling discontent and dissatisfaction with the unfairness of the prevailing economic, social and political situation, expressed at the ballot box in many countries (Rodríguez-Pose, Citation2018).

People feel ‘left-behind’ because they perform not merely as mobile factors of production responding to market signals, but as social and political actors reflecting their membership of communities located in places that affect belonging and attachments. Places are a focus for identities that residents feel are denigrated or under threat. The importance of belonging and place attachments though scarcely figures in academic debates about LBPs, nor more broadly in urban and regional studies (for an exception, see Butzin & Terstriep, Citation2022). Yet, as we show, there are compelling reasons to give them serious consideration.

In the context of this ‘affective turn’ in the study of LBPs, growing attention has been given to the role of SI in shaping place attachments and the contribution this makes to human welfare. Although imprecisely or inconsistently deployed in academic and policy debates, Klinenberg (Citation2019, p. 5) defines SI as ‘the physical places and organisations that shape the way people interact’. He offers a capacious definition that includes ‘libraries, schools, playgrounds, parks, athletics field and swimming pools’, as well as ‘sidewalks, courtyards, community gardens, and other green spaces that invite people into the public realm’. He also counts ‘community organisations, including churches and civic associations’ and ‘regularly scheduled markets’ that allow people to assemble and socialise. A wider definition would include, less visible, more intangible aspects, that is, ‘the networks of formal and informal groups, organisations, partnerships, activities and initiatives that both benefit from and sustain the physical and social fabric of a place’ (All Party Parliamentary Group on Left Behind Neighbourhoods, Citation2020, n.p.). SI may take a range of forms, but its purpose is to provide opportunities for gathering, sociality and the formation of attachments, creating spaces for differences to be aired civilly, disputes resolved and collective action agreed upon.

The loss of SI in LBPs is now the focus of research and policy and is discussed in more detail below. Klinenberg (Citation2019, p. 151) maintains that ‘As the factories shuttered, so too did the union halls, taverns, restaurants and civic organisations that glued different groups together’, so the loss of SI is felt disproportionately in LBPs and is reflected in working class political disenchantment. A growing body of research suggests that LBPs are comparatively underserved with respect to SI (see Tomaney et al., Citation2023, ch. 2, for a review). In the UK, the All Party Parliamentary Group on Left Behind Neighbourhoods (Citation2020) suggests LBPs experience a ‘social infrastructure deficit’. Addressing failures in provision of SI is now a policy objective in the UK, although practical measures to this end remain difficult to discern (Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities, Citation2022). As we show below, this loss of SI in LBPs is all the more striking because many were once richly endowed with it. This paper contributes to an emerging academic literature on SI (Urban Geography, Citation2022; Urban Planning, Citation2022) but addresses a question that has received limited attention in the debate about SI, namely, what are the conditions under which it is made, unmade and remade, especially in LBPs.

We achieve our aim through a detailed case study of one village, a former coal mining community in northern England. We develop a framework that allows us to develop a historical and relational account of SI, describing the conditions under which it is produced, its contribution to local development and how it is lost. We emphasise the importance of place attachments and the ways these affect commitments to place that are the source of civic action. We see LBPs not merely as bundles of social and economic indicators but, using Wuthnow’s (Citation2018) formulation, as ‘moral communities’, whose identity is given expression, inter alia, in the making of SI. We adopt Fullilove’s (Citation2016) concept of ‘root shock’ to understand the effects of its loss. We employ Lear’s (Citation2008) concept of ‘radical hope’ to describe the conditions under which people act to (re)make SI.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The following section sets out our framework. Next, we briefly outline our mixed methods informed by an ethnographic sensibility which we see as appropriate to capturing the quality of place attachments and the ways these shape efforts to provision SI. We then introduce and describe our extended case study of a County Durham mining village. We conclude by emphasising the value of our framework and methods for understanding the making, unmaking and remaking of SI.

2. A FRAMEWORK FOR UNDERSTANDING THE MAKING, UNMAKING AND REMAKING OF SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE IN LEFT-BEHIND PLACES

Communities enact attachments but, according to Prendergast (Citation2021, n.p.), economic restructuring has led to the ‘destruction of belonging in our communities’. Attachment theory considers the importance of connectedness between people in shaping patterns of human development (Bowlby, Citation1973, Citation1980, Citation1999; Kraemer & Roberts, Citation1996). Damaged human attachments result in trauma, can arouse feelings of loss and grief, and may create long-term psychological stress. The importance of place attachments has received attention in academic literature (Devine-Wright & Howes, Citation2010; Manzo & Devine-Wright, Citation2013) although it has had comparatively little influence on the debate about LBPs. But the disruption of place attachments can engender collective feelings of loss, akin to bereavement (Marris, Citation1986). Residents narrate the loss of local industry, and the society in which it was embedded, using the language of loss and grief, while simultaneously expressing a sense of belonging partly derived from an identity linked to a distinctive industrial past (see Mattinson, Citation2020; and Silver et al., Citation2020, for evidence).

For Wuthnow (Citation2018, p. 56), the closure of a major employer can induce ‘a sense of loss, a feeling of grief’ within communities. Prendergast (Citation2021) points to how men who lost their jobs following the closure of a 250-year-old paper mill in western England articulated this not in terms of economics but of the moral value their past employment gave to their lives. Some broader consequences of deindustrialisation have been identified by Case and Deaton (Citation2015) who seek to explain rising morbidity and mortality among white non-Hispanic groups in the United States in terms of the prevalence of ‘diseases of despair’: alcohol and narcotic overdose, suicide, and alcoholic liver disease. Angus Deaton has suggested that white working class men are especially susceptible to ‘diseases of despair’ because they have ‘lost the narrative of their lives – meaning something like a loss of hope, a loss of expectations of progress’ (quoted in Belluz, Citation2015, n.p.).

Although LBPs commonly are presented as aggregates of economic and social statistics, according to Wuthnow, we should see them as ‘moral communities’ which embody distinctive values that produce strong attachments, a sense of belonging, and ‘stories about their history that help them make sense of their present’ (Wuthnow, Citation2018, p. 96). In one reading, this is a recipe for an unproductive nostalgia. But nostalgia has useful psychological attributes: it generates positive affect, raises self-esteem, fosters social connections and alleviates perceived existential threat (Sedikides et al., Citation2008). For Teti (Citation2018, p. 11), nostalgia can express both hope and remembrance and be mobilised in the (re)invention of a new identities. A collective history provides the foundations of ‘communities of hope’ (Bellah et al., Citation2007) which connect current and individual efforts to a larger common good. Memory and hope provide the frameworks in which ‘practices of commitment’ define ‘the patterns of loyalty and obligation that keep the community alive’ (Bellah et al., Citation2007, p. 152). As Teti (Citation2018, p. 192) observes, communities are subject to constant change, but stories are heritable: ‘The only thing that remains are stories and with them the people who live to tell them.’ Collective memory is a foundation for local attachments, the key to the mobilisation of civic resources (Olick et al., Citation2011) providing ‘resources of hope’ (Williams, Citation1989).

Once we consider this affective dimension – which otherwise barely figures in our understanding of local and regional development – the idea of LBPs as ‘moral communities’ comes sharply into focus and allows a deeper understanding of their crisis. Fullilove generates the concept of ‘root shock’ to describe the trauma of disruptive socio-economic change, deriving it from her study of the African American experience of ‘urban renewal’, which often resulted in the complete displacement of communities. Root shock represents ‘the traumatic stress reaction to the destruction of all or parts of one’s emotional ecosystem’ (Fullilove, Citation2016, p. 11) It ‘undermines trust, increases anxiety, about letting loved ones out of one’s sight, destabilises relationships, destroys social, emotional and financial resources, and increases the risk for every kind of stress-related disease, from depression to heart attack’ (p. 14).

These problems are compounded in LBPs because, often, the story is not just of ‘economic decline’ but the end of a way of life. This ending may have happened in a previous generation, but its effects reverberate through time as a crisis of ‘moral community’. The loss of SI can disrupt local attachments in much the same way as the closure of a place-defining local employer. Findings from the Pew Research Centre, based on focus groups in the US and UK, show that a sense of being ‘left behind’ was informed by experiences of industrial restructuring, but also by the decline of high streets and the closure of pubs and clubs, which were described as key community-building institutions. Pubs were viewed as gathering spaces for people to build relationships. Bolet (Citation2021) demonstrates that pub closures in England – disproportionately concentrated in LBPs (Qureshi & Fyans, Citation2021) – were associated with higher levels of support for the populist United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) in the run up to the Brexit referendum. Youth clubs played a similar socialising role and their closure was seen as pushing young people onto the streets to engage in antisocial activity or crime (Silver et al., Citation2020).

Fullilove emphasises the critical role of the ruin of the built environment in causing ‘root shock’ (see also Mah, Citation2012, for a somewhat similar argument). The destruction of familiar buildings and spaces, street scenes and ‘desire paths’ can cause disorientation, especially when it occurs on a large scale, because these structures provide the scaffolding of everyday life. The street is a locus of collective memory (Hebbert, Citation2005). Historic buildings, especially, give tangibility to people’s sense of local identity (Public First, Citation2022). This is not so much a product of the architectural merit of individual buildings but more the result of the role they play in connecting people with their civic, family and local histories. Everyday buildings used by the mass of people hold greatest significance, reminding people of their communal past. When well-loved buildings fall into ruination this can be experienced as a loss of civic pride. Attributes of the built environment that are attached to industrial heritage most strongly contribute to local identity and the stories people tell about the history of their family and place, not just by older people but also by younger generations (Grimshaw & Mates, Citation2021). In this sense the loss of SI can generate a similar sense of bereavement as the closure of a factory, shipyard or mine.

Why stay in an LBP? Wuthnow draws on hundreds of interviews in small communities in ‘left-behind’ America, to answer this question. He suggests stayers, ‘recognise the disadvantages of living where they do, and yet they weigh these disadvantages of living where they do against the obligations they feel to their children and, perhaps to aging parents, and to themselves’ (Wuthnow, Citation2018, p. 69). For many, strong attachments underpin active decisions to stay and make commitments to their place, even in the face of population decline, a lack of (good) jobs, brain drain and increasing social problems. Drawing on the experience of the Calabrian village where he grew up, which has experienced population loss through emigration, the Italian anthropologist Teti (Citation2018) concludes that staying behind is not an easy decision but a purposive and difficult process. In the work of the Foundational Economy Research Ltd (FERL) (Citation2022) on a declining Welsh slate mining village, stayers explain their decision using a narrative of attachment, albeit one open to the necessity of change. Lear (Citation2008) is concerned with finding an ethical base for social action in the face of cultural devastation. In these conditions, he suggests that social alternatives arise from acts of ‘radical hope’ – practical responses to the end of a way of life – that are the product of a sense of belonging and deep attachments, that both draw upon and produce commitments to place but are founded on flexibility and openness. Radical hope is ‘directed toward a future goodness that transcends the current ability to understand what it is’ and ‘anticipates a good for which those who have hope as yet lack the appropriate concepts with which to understand it’. It is a weapon against despair, a means to survive the end of your world. The (re)making of SI is almost always an exercise in radical hope.

Existing research on SI either attempts to measure, quantify, index its (non-) provision or sketch cases studies of its effects in LBPs (see Tomaney et al., Citation2023, p. 16, for a review). For LBPs, efforts have been made to calculate the return on investment in SI, to measure its contribution to the production of social capital, or to improve health outcomes. Deficiencies in SI in LBPs, increasingly, are considered a component of urban and regional inequality. Andy Haldane, former chief economist of the Bank England, argues that when SI is lost, social capital depreciates ‘and [offers] another reason to feel left-behind’ (Haldane, Citation2019, p. 16). But assessing the value of SI is bedevilled because its affordances are several, escaping the calculus of conventional benefit–cost ratios: a public library can simultaneously be repository of books and a place of learning, a source of commercial support for small businesses and somewhere to keep warm or overcome loneliness. Moreover, most studies do not address the main questions which are the focus of this paper, namely under what conditions is SI made, unmade and remade.

We have established a framework for investigating the making, unmaking and remaking of SI in LBPs. This recognises the importance of place attachments, the formation of LBPs as ‘moral communities’ and the making of SI as the result of local commitments and an expression to local identity as well as meeting material needs. The unmaking of SI, especially where it involves the ruination of the built environment, represents a form of ‘root shock’ that disrupts place attachments. The production of stories about place is key to the formation LBPs as moral communities. In turn, stories provide the resources for ‘radical hope’ that underpins the (re)making of SI.

3. UNDERSTANDING SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE IN LEFT-BEHIND PLACES USING NOVEL MIXED-RESEARCH METHODS AND AN ETHNOGRAPHIC SENSIBILITY

As Star (Citation1999) notes, infrastructure has a number of characteristics that lend themselves to research using an ethnographic approach because it is embedded in broader social arrangements and, typically, is a longstanding feature of the bult environment. It extends beyond a single episode and is shaped by the conventions of a community of practice, builds on installed bases and does not grow de novo but is fixed in modular increments, and becomes politically visible upon breakdown. Moreover, ‘the state of our SI and how we use and experience it can tell us a lot about the places in which we go about our everyday lives’ (Yarker, Citation2021, p. 5). Ethnography offers the opportunity to ‘ground’ theory – in this case of SI – in lived experiences. Attention to LBPs in terms the attachments, practices, perspectives and aspirations they generate, ‘produces an analysis that challenges the dominant instrumental view of urban planning’ (Koster, Citation2020, p. 197). Mattilia et al. (Citation2022) make a strong case for using ethnographic methods in urban and regional planning as a means of breaching the gap between communicative methods that seek to elicit intersubjective consensus (participatory planning) and ‘knowledge-based’ approaches (oriented toward quantitative analysis and the production of abstract or generic place-based data). Ethnographic approaches promise insights into the temporalities and geographies of SI, the contribution of local actors to its production, the nature of any conflicts such as the gendered character of access to it (Hall, Citation2020). Above all, an ethnographic sensibility makes us alert to the affective dimensions of social and economic disruption.

These observations seem pertinent in the case of SI. Frankenberg’s (Citation1957) classic study of the village of ‘Pentrediwaith’ in north Wales shows that activities that begin for the purposes of recreation – a choir, brass band, dramatic society, football club, carnival – symbolise the desire for community and offer a means to express local identity. These activities are contested and involve both the creation, abandonment and reconstitution of activities – the making, unmaking and remaking of SI – but constitute the basis of a ‘moral community’. As a foundational text in the ‘Manchester School of Anthropology’, Frankenberg’s study pioneered the ‘extended case method’, which according to Burawoy (Citation1998, p. 5) ‘applies reflexive science to ethnography in order to extract the general from the unique, to move from the “micro” to the “macro”, and to connect the present to the past in anticipation of the future, all by building pre-existing theory’. To achieve this, fieldwork must combine historical and documentary analysis, interviews and observations, to elucidate social processes in bounded communities, albeit in a global context, providing insights into the lived experience of social change (Burawoy et al., Citation2000). We use this method inductively to advance a theory of SI that emphasises the importance of place attachments, drawing on concepts of ‘moral communities’, ‘root shock’ and ‘radical hope’.

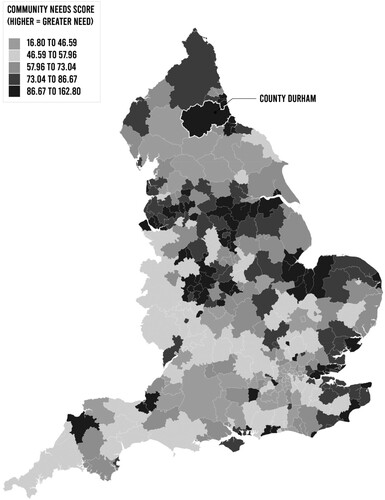

Informed by an ‘ethnographic sensibility’ (Burawoy et al., Citation2000), we deploy a set of mixed methods to investigate our site, the former coal mining village of Sacriston in County Durham, England. This study was conducted with the Durham Miners’ Association (DMA), employing an embedded researcher. County Durham contains a comparatively high proportion of LBPs, as measured by the UK government’s index of multiple deprivation, and is deficient in SI, according to the analysis undertaken by Local Trust/Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI) () (Local Trust, Citation2019). The village has a population of 6000 and lies 6.5 km north-west of Durham city. The findings reported here form part of an ongoing study, based on relationships with local actors, many of whom are involved in the production and maintenance of the SI we describe. We trace the making, unmaking and remaking of SI in Sacriston. Our analysis reveals that Sacriston was once richly endowed with SI, but much of this has been lost, yet the processes which produced this outcome are complex. Moreover, we reveal efforts to remake SI. To this end, we integrate a range of data, including archival and oral history; focus groups with government and other agencies, community organisations and school children; in-depth interviews with key actors in the village; and cartographic representations to provide a narrative of the making, unmaking and remaking of SI (see Tomaney et al., Citation2023, ch. 3, for more detail on the methods). Participants in the research gave written informed consent to their involvement and, where identified below, participants gave their explicit written permission for their testimony to be used in this paper.

Figure 1. Community needs index: community needs score (higher = greater need), showing all areas at local authority level with County Durham highlighted.

Source: Oxford Consultants for Social Inclusion (OCSI)/Local Trust – Local Insight. https://ocsi.uk/2019/10/21/community-needs-index-measuring-social-and-cultural-factors/ (adapted by the authors).

4. SACRISTON, COUNTY DURHAM: THE MAKING, UNMAKING AND REMAKING OF SOCIAL INFRASTRUCTURE

Sacriston exists because of coal. Although mining had taken place on a very small scale there for generations, the sinking of a shaft 200 m below ground in 1839, to access the rich Victoria seam, transformed this corner of County Durham, creating a new industrial society. By 1850, Sacriston was a tiny village, comprising a handful of insanitary and overcrowded terraced cottages, hastily erected by the coal company to accommodate its new workforce. Migrants flocked to the village take advantage of the new employment opportunities in the mine. Employment at Sacriston colliery peaked at about 950 men during the interwar period, by which the village had grown to accommodate them and their families. Alongside the pits, a wave of SI building began in the mining villages of County Durham, in large part organised and resourced by miners and their families themselves via their collective associations. The creation of SI was contested and produced exclusions as well as inclusions. Religious buildings catered to segregated communities, who lived together in different parts of the village. The village experienced religious sectarianism following mass Irish immigration in the 1850s and 1860s. Access to SI was also highly gendered in a society focused on an exclusively male industry. Nevertheless, as the Durham miner, turned writer, Sid Chaplin, put it, ‘each village was, in fact, a sort of self-constructed, do-it-yourself counter-environment. … The people had built it themselves’ (Chaplin, Citation1978, pp. 80–81). It was a world that emphasised ‘neighbourhood, mutual obligation, and common betterment’ (Williams, Citation1989, p. 96), as expressed through its collective and cooperative institutions.

Conditions in the both the mine and the village were harsh. Although Sacriston largely avoided the major underground disasters experienced by some nearby collieries, mining work was difficult, dirty, dangerous and periodically deadly. Miners organised in order to improve workplace conditions, culminating in the formation of the DMA in 1869. Major strikes, above all, in 1926, caused immense hardship. The leadership of the DMA pursued a distinctive politics of moderation and conciliation with the mine owners through most of this period. Local branches of the DMA (‘Lodges’) were key institutions in village life and became involved in the battle to improve social conditions beyond the workplace. Lodge banners, paraded annually at the Durham Miners’ Gala, were treated with reverence and became symbols of village identity and the strong attachments which underpinned it (Tomaney, Citation2020). In short, Sacriston emerged as a distinctive ‘moral community’, with the provisioning of SI giving expression to this.

4.1. Making social infrastructure, 1850–1950

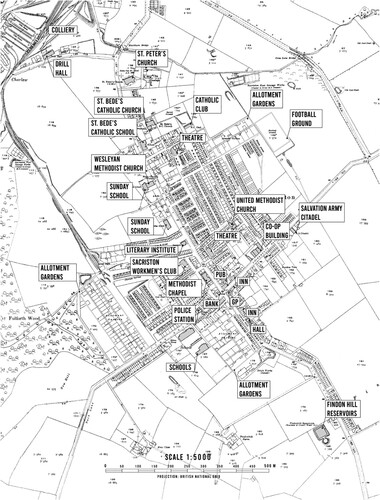

To begin with, Sacriston, like other coalfield villages, lacked even basic infrastructure and services. Housing conditions were dreadful, disease was rife, medical care was rudimentary, water and sanitation provision comprised, at best, standpipes and dry closets, while roads were unpaved and street lighting non-existent. The earliest forms of SI came in the shape of religious institutions and buildings. By 1890, as attested by business directories, villagers had built Wesleyan and Primitive Methodist chapels, a Catholic church – to accommodate Irish migrants – and an Anglican church. Other Methodist sects built chapels, along with the Plymouth Brethren, and the Salvation Army opened a citadel in the village. These were not simply places of Christian worship but were also centres for social action. The Anglicans and Catholics built schools, while a Sunday school tradition developed among the Methodists. Alongside religious buildings, a working men’s club opened in 1902. A Literary Institute, built by the colliery company, catered to autodidacts. Almost all this SI was funded from resources generated within the village itself. Fr. Lenders, reflecting in 1930 on 70 years of Catholic SI building in the village – which included a Catholic church, presbytery, League of the Cross clubhouse, school and cemetery, noted that it had been funded by ‘the pennies and sixpences’ of Irish miners (Lenders, Citation1930, p. 29). The village also contained several pubs, which provided opportunities for men to socialise outside the home. maps the provision of SI in the village in 1910, although there were important additions after this date, notably the Memorial Hall, discussed below.

Figure 2. Social infrastructure in Sacriston, County Durham, UK, 1910.

Note: Scale = 1:5000.

Source: Digimap Historic Roam, https://digimap.edina.ac.uk/historic (downloaded on 1 October 2021) (adapted by the authors).

In this milieu, local traditions of cooperation and mutualism emerged. Two clear examples are provided by the village Co-op (or the ‘Store’, as it was universally known) and the Durham Aged Mineworkers’ Homes Association (DAMHA). In 1897, the Annfield Plain Industrial Co-operative Society Ltd opened a branch in Sacriston in a prominent position in the centre of the village (Ross & Stoddart, Citation1921). The Society was one of several formed across County Durham during last quarter of the 19th century to improve the quality of retail services in mining villages. County Durham had the highest cooperative society membership rate in Britain by 1940 (29%) – twice that of south-east England (Cole, Citation1944). (The rate of membership in Sacriston itself likely was higher still.) The Society’s profit – or ‘surplus’ as it was known – was shared among the members in the form of a ‘Dividend’. The opening of the Sacriston branch of the Co-op was a major event and contemporary reports lauded its opulence. On the first floor was a meeting hall which could accommodate 700 people and the ‘Store Hall’ became an important location for social and political activities. McCullough Thew (Citation1985, p. 71), who grew up in mining village in the adjacent Northumberland coalfield and later worked in the local Co-op, described the moral community in which ‘the Store’ was embedded:

My family, the church, the school, the pit and the store. These were woven into the fabric of my life from the beginning. Allegiance to the church might waver, schools change, our stay in various houses be short-lived, work at the pit be unpredictable but our attitude to the store was steadfast. It claimed our wholehearted fealty and esteem.

The Labour Party emerged in the first decade of 20th century as the vehicle to advance working-class interests in County Durham. Branches were formed across the county and a long campaign led the DMA to switch allegiance from the Liberals to Labour. A key moment occurred in the 1906 General Election when John Wilkinson Taylor, backed by the DMA, defeated both the Liberal and Conservative candidates, and was elected as Labour MP for the Chester-le-Street parliamentary constituency, of which Sacriston was part. Labour has represented the constituency uninterrupted, in its various guises, since then. At a local scale, Labour also began to win representation on parish and district councils and boards of poor law guardians, setting about improvements to housing, health, water and sanitation, and education. In 1919, Labour won control of Durham County Council. After briefly losing its majority but remaining the largest party, Labour recaptured the County Council in 1923. Politics was a male-dominated world but, in Annie Errington (1882–1959), a Labour councillor, Sacriston produced an outstanding political leader who was at the forefront of campaigns for more and better SI (Tomaney, Citation2023). County Durham experienced major social advances, such as rapid reductions in child mortality, and a rate of council house building at twice the national average, consolidating the party’s hegemony. Labour from 1906 onwards provided the connective tissue that linked political, industrial and social action, enabling conditions for the creation of SI (Tomaney, Citation2018). But although Sacriston remains represented by Labour, after a century, the party lost control of Durham County Council in 2021, an event which occurred in the context of a broader loss of electoral support in its ‘heartlands’ (e.g., Mattinson, Citation2020).

4.2. Unmaking social infrastructure, 1950–2000

Sacriston colliery closed in 1985, part of the death throes of the Durham coalfield, which had employed 175,000 men at its peak. This event accelerated the restructuring of SI but was not its sole cause. Austerity, likewise, was an important – but not the only – factor reshaping SI in Sacriston after 2008. The decline of SI was part of longer term processes, affected by broader socio-economic and governance changes that can go unacknowledged. The era of SI building in Sacriston, from the mid-19th to the mid-20th centuries, described above, bequeathed community assets and rich social networks, but these were already being transformed before the pit closed.

Major transformations in village life occurred in the post-war period. In 1947, the coal industry was nationalised, removing ownership and control of the pit from the village. The pit was now managed by a bureaucracy headquartered in London. Locally operated infrastructure and services increasingly came under the purview of the national government, as the welfare state expanded. Successive waves of local government reform centralised decision-making, rendering political power more remote and inaccessible. This was the era of ‘high modernist planning’ (Scott, Citation1998) that brought improvements in many aspects of living conditions but at the cost of institutional and administrative centralisation and the erosion of local control of SI that placed limits on the adaptive capacity of the village (see Pike et al., Citation2010, for a discussion of adaptive capacity to resilience of local economies).

In the 1950s–70s, however, Sacriston was a thriving place. Economic and community vitality were inextricably linked; most people were far from wealthy, but fulltime work for men was plentiful, wages were rising, work – particularly part-time work – was increasingly available for women, and young families were moving from substandard colliery housing into new, modern council and owner-occupied homes. A strong local economy and full employment, based on the pit, underpinned a strong community. In her memoir, There Is Nothing For You Here, the County Durham-born US national security official, Fiona Hill, who, as the daughter of a coal miner, spent her childhood in a Durham mining community, states, ‘In the 1950s, the Durham miners thought they had made it’ (Hill, Citation2021, p. 25) This period is still within living memory in a village like Sacriston, even the if these memories are fading.

Families continued to spend their money and their leisure time mainly in the community where they lived. There was the Memorial Institute, built shortly after the First World War, which contained a reading room, the working men’s club and the Catholic Club. There was a dance hall, a bowling green, a library, cinemas and several pubs: ‘The Robin Hood, George & Dragon, Colliery Inn, The Queen’s Head, The Three Horse Shoes’ (Hughie Dixon, Sacriston Parish Council). Religious observance remained high in the 1950s and 1960s, albeit attendances began to fall in the 1970s. Shopping in the Front Street and the home were the main sites of women’s socialisation, although the churches and chapels hosted women’s organisations, such as the Catholic Women’s League, and the Cooperative Women’s Guild was also present in the village. The village was characterised by a high level of conviviality and strong local attachments: ‘Everybody knew everybody, you knew who lived here and there’ (Derek Robson, Parish Council, Fulforth Community Centre). A rich endowment of SI supported a wide range of sociality.

So, we had all of these social spaces but then we also had lots of activities going on. We had the Brownies and Guides, the Salvation Army, the church hall, Fyndoune. We had a thriving Cubs and Scouts group … So lots of things to do, regular jumble sales, coffee mornings, fairs, Christmas fairs, Christmas Carol services, all that sort of thing.

(Heather Liddle, Sacriston Enterprise Workshops/Sacriston Youth Group)

The closure of the pit, however, was a watershed that transformed conditions in the village:

There was a lot of money in the village when the pit was open, shops were thriving, I mean it was good. I can remember the old co-op and thankfully that’s been revived. With the pits closing it sort of dragged the village down. I would personally like to see the Front Street a lot livelier … the village suffered; the shops suffered. You know the new superstores have affected all the general stores in the village and changed the whole aspect. Even the pubs … they’ve all closed.

(Keith Allen, Sacriston Colliery Cricket Club)

A change I have seen is people moving into the village who don’t actively socialise … some people do engage a bit, but we know how much the village has changed in the last ten or fifteen years. A lot of people you can see just drive out to go to work, drive back in.

(Keith Allen, Sacriston Colliery Cricket Club)

what these people do is, they go to Tesco for a pint of milk on their way home. They don’t go to the library. They don’t go to the independent shops because they don’t have that connection, that’s the divide.

(Gemma O’Brien, Sacriston Youth Group)

Klinenberg (Citation2009) identifies the importance of SIs used by young people, although their perspectives and experiences are rarely considered in these debates. Schools, for instance, are discussed primarily in terms of educational quality and individual student achievement, but they are also places where democratic practices are established, civic skills learned, and local commitments practiced. In the case of Sacriston, the closure of the local secondary school was experienced as grievous blow by the local community – a classic ‘root shock’ that disrupted well worn ‘desire lines’. Pupils must now travel to a school in Durham City. In focus groups, we found young people from Sacriston have a strong awareness of the strengths and weaknesses of village SI and have critical awareness of past and present place identities and gaps in provision. Even during their lifetimes, they sense a decline in the quality of SI and are aware of – and endorse – rebuilding efforts.

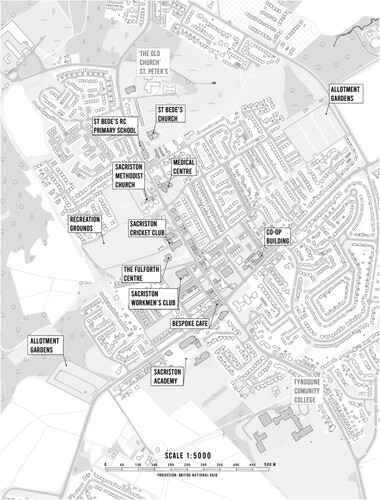

4.3. Remaking social infrastructure, 2000–22

Maintaining and developing SI in difficult circumstances has been a struggle undertaken by committed citizens, exhibiting the attributes of ‘radical hope’. Compared with 1915, SI by the 21st century was much denuded (). Major recent losses include St Peter’s Church – due to falling attendances – and Fyndoune School, both of which are vacant and unused at the time of writing. Austerity has accelerated an incipient crisis. A popular children’s centre, established under the then Labour government’s ‘Sure Start’ programme, was opened in 2010, only to be closed in 2015. But the village has experienced two contemporary episodes which reveal the promise and challenges of SI building in LBPs. First, the Memorial Institute, which had been a centre of village activity for generations, was in poor repair by the 1990s and did not meet modern safety and accessibility requirements. Proposals for its future proved contentious. Some in the village wanted the building modernised because it symbolised a historic identity, but it was deemed cheaper to demolish and rebuild and it was replaced by a new building known as the Fulforth Centre. The effort to raise the funds for this purpose was a long one with original plans scaled back but the centre is now the base for the activities of a number of village groups.

Figure 3. Social infrastructure in Sacriston, County Durham, UK, 2022.

Scale = 1:5000.

Source: Digimap Ordnance Survey, https://digimap.edina.ac.uk/os (downloaded on 28 September 2021) (adapted by the authors).

Second, the Co-op building, which was used for various activities following the closure of the branch, had stood largely empty for 15 years, was repurposed and brought back into use after 2019. Again, it was a struggle. An early problem was that the legal ownership of the building was unclear for some time. Eventually, a new ‘Community Interest Company’, ‘Sacriston Enterprise Workshops’, was established and the building was leased to it by Durham County Council in 2019 for a nominal sum. The Co-op building, now refurbished, houses four independent organisations, although there is a high degree of cooperation between them and plans to attract others. Sacriston Woodshed Workshop is a social enterprise that trains young people, who are not in education, employment or training, in woodworking skills. It designs and creates wood furniture and products through the use of reclaimed, recycled, reused and ethically, sustainably and locally sourced wood. The young people trained at Woodshed typically are highly vulnerable and have not flourished in the school system. ‘Recycld’ runs a shop that sells reclaimed wood products. ‘Sacriston Youth Project’ provides out-of-school activities for children and young people who would not otherwise have access to them, filling a gap left by the closure of the Sure Start centre. ‘Live Well North East’ provides a range of health-related activities. The Co-op building is now a hive of activity and symbol of self-improvement in the village: ‘It’s the sense of ownership. It’s the sense of belonging. The space is yours. And I think that’s what works’ (Gemma O’Brien, Sacriston Youth Group). Funding these activities requires constant effort in an era of austerity. Local authorities are viewed as remote, inflexible and bureaucratic. For instance, when the local secondary school closed, the parish council wanted to develop the site as a home for a local football club, but the plans failed. Typically, where support is offered, it is for capital projects rather than ongoing running costs. SI (re)makers have become adept at overcoming these obstacles. For instance, Sacriston Youth Project has struck up relationship with a private foundation that has supported its activities in ways government funders seem unable to.

What accounts for this new wave of SI building in Sacriston in conditions that in many ways are hostile? One important aspect of answer to this question concerns strong local attachments, a powerful sense of belonging and deep commitment to place. The chairperson of the Fulforth Centre states categorically, ‘I run the centre because of a love for Sacriston’ (Linda Surtees, Fulforth Centre). Those involved in the provision of SI make long commitments, ‘I’ve been here that long now that at the presentation evening for the seniors, I remembered them when they were titchies [young children]’ (Keith Allen, Sacriston Colliery Cricket Club). Sacriston Cricket Club is more than a sporting venue. It is a space for growing up in the village and during the COVID-19 pandemic was involved in the provision of food to the housebound. Place attachments foster commitments and furnish the ‘local knowledge’ that helps identify unmet needs and offer practical solutions to them:

there’s your connection to place and I’ll work with people from our area … and probably tolerate far more than I should actually tolerate because I’m more drawn to the stories of the people I work with, and I get more actively involved because I'm from this place. I really employ from the local pool … all DH7 [Sacriston postcode], brought up in and around here and that’s probably as much training as you need with it! If you have lived experience with this area and you’ve got different approaches to it, you know.

(Nathan Hopkins, Sacriston Enterprise Workshops/Woodshed)

Some SI (re)makers articulate their activities in terms of the reinvention of the civic and political traditions of the village, an expression of collective memory and productive nostalgia underpinning ‘radical hope’.

I think we have a very, very different project to many youth projects because we’re not really a youth project, we’re a community service disguised as a youth project. So, most youth projects will do from like age 11 to like 16. Whereas we do from like pre-birth to death. Which is the Co-op ethos – cradle to the grave.

(Gemma O’Brien, Sacriston Youth Group)

5. CONCLUSIONS

This paper has considered the making, unmaking and remaking of SI in a LBP. It contributes first to the emerging literature on SI, which, hitherto, has tended to neglect its role in LBPs and overlooks the conditions under which it is made, unmade and remade. Second, it contributes to the literature on LBPs, which tends to neglect the affective dimension of ‘left-behindness’. Regional studies typically, has been concerned with the ‘drivers’ of growth such as innovation, physical infrastructure and the structure of employment. Urban sociology, meanwhile, has tended to focus on neighbourhood scale, examining patterns of inclusion and exclusion. But the emergence of the ‘left-behind’ places phenomenon and the persistence of concentrated disadvantage suggests that this intellectual division of labour does not help our understanding. To address these lacunae, we used mixed methods informed by an ‘ethnographic sensibility’ to deepen and extend our understanding the role of SI and LBP, through an extended case study of one village. Our theorisation is inductive, drawing on what we observe in the village to develop a framework for its understanding.

Our approach focuses on LBPs as ‘moral communities’ (Wuthnow, Citation2018), founded on place attachments, whose identity is expressed, crucially, in the provisioning of SI. The loss of SI, we show, is a complex process, lengthier than often understood. In his novel The Sun Also Rises (Citation1926, p. 141), Ernest Hemingway has two of his characters discuss how one lost his fortune:

‘How did you go bankrupt?’ Bill asked.

‘Two ways,’ Mike said. ‘Gradually and then suddenly.’

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are grateful to Sarah Chaytor, Siobhan Morris, Katherine Welch and Julie Hipperson at UCL for their help in developing and managing the projects. The research was conducted in partnership with the Durham Miners' Association. Thanks to our collaborators in County Durham, especially Ross Forbes at the Durham Miners' Association, Heather Wood at Sacriston Youth Project and Nathan Hopkins at Woodshed Workshop. Thanks also to Fiona Thompson at Framwellgate School. We are grateful to Stefan Noble and Kimberley Gregory at OCSI for permission to use the data reported in Figure 1. The ideas in this paper were developed through discussions at: Regional Studies Association Conference, June 2021; JUC Public Administration Committee, Leicester, September 2021; Wales Institute of Social and Economic Research and Data, Cardiff, September 2021; Seoul National University, September 2021; University College London, October 2021; Hughes Hall, Cambridge, January 2022; Royal Geographical Society Annual Conference, Newcastle upon Tyne, August 2022, Centre for Urban and Regional Development Studies, Newcastle University, February 2023, and Regional Studies Association Policy Expo, May 2023. For comments, advice and/or helpful discussions, we thank especially Charlotte Carpenter, Estelle Evrard, Maurice Glasman, Patsy Healey, Yunji Kim, Danny Mackinnon, Kevin Morgan, Emma Ormerod, Andy Pike, Jonathan Rutherford, Natasha Vall, Karel Williams and Jane Wills.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

REFERENCES

- All Party Parliamentary Group on Left Behind Neighbourhoods. (2020). Communities of trust: why we must invest in the social infrastructure of ‘left behind’ neighbourhoods. https://www.appg-leftbehindneighbourhoods.org.uk/publication/communities-of-trust-why-we-must-invest-in-the-infrastructure-of-left-behind-neighbourhoods/

- Bellah, R., Madsen, R., Sullivan, W., Swidler, A., & Tipton, S. (2007). Habits of the heart. Individualism and commitment in American life (Revd edn). University of California Press.

- Belluz, J. (2015). Nobel winner Angus Deaton talks about the surprising study on white mortality he just co-authored. Vox, 7 November. https://www.vox.com/2015/11/7/9684928/angus-deaton-white-mortality

- Bolet, D. (2021). Drinking alone: Local socio-cultural degradation and radical right support – The case of British pub closures. Comparative Political Studies, 54(9). https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414021997158

- Bowlby, J. (1973). Separation: Anxiety & anger. Attachment and loss (Vol. 2). Hogarth.

- Bowlby, J. (1980). Loss: Sadness & depression. Attachment and loss (Vol. 3). Hogarth.

- Bowlby, J. (1999). Attachment. Attachment and loss (Vol. 1) (2nd ed.). Basic.

- Bunting, M. (2020). Labours of love. The crisis of care. Granta.

- Burawoy, M. (1998). The extended case method. Sociological Theory, 16(1), 4–33. https://doi.org/10.1111/0735-2751.00040

- Burawoy, M., Blum, J., George, S., Gille, Z., & Thayer, M. (Eds.). (2000). Global ethnography forces, connections, and imaginations in a postmodern world. University of California Press.

- Butzin, A., & Terstriep, J. (2022). Strengthening place attachment through place-sensitive participatory regional policy in a less developed region. European Planning Studies. 10.1080/09654313.2022.2156274

- Case, A., & Deaton, A. (2015). Rising morbidity and mortality in midlife among white non-Hispanic Americans in the 21st century. PNAS, 112(49). https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1518393112

- Chaplin, S. (1978). Durham mining villages. In M. Bulmer (Ed.), Mining and social change. Durham county in the twentieth century (pp. 95–94). Croom Helm.

- Cole, G. D. H. (1944). A century of cooperation. George Allen & Unwin.

- Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities. (2022). Levelling up the United Kingdom (CP604). HMSO. https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/levelling-up-the-united-kingdom

- Devine-Wright, P., & Howes, Y. (2010). Disruption to place attachment and the protection of restorative environments: A wind energy case study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(3), 271–280. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.01.008

- Durham Aged Mineworkers’ Homes Association (DAMHA). (1909). An appreciation of the life of Joseph Hopper. Pioneer of the Durham Aged Mineworkers’ Homes Association.

- Foundational Economy Research Ltd (FERL). (2022). A way ahead? Empowering Restanza in a slate valley. FERL. https://foundationaleconomycom.files.wordpress.com/2022/04/restanza-english-version-as-of-7-feb-2022.pdf

- Frankenberg, R. (1957). Village on the border. A social study of religion, politics and football in a North Wales community. Cohen & West.

- Fullilove, M. T. (2016). Root shock. How tearing up city neighborhoods hurts America, and what we can do about it. NYU Press.

- Grimshaw, L., & Mates, L. (2021). ‘It’s part of our community, where we live’: Urban heritage and children’s sense of place. Urban Studies, 57, 1334–1352. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980211019597

- Haldane, A. (2019). Ashington – Speech given at St. James’ Park, Newcastle upon Tyne, 24 September. https://industrialstrategycouncil.org/sites/default/files/2019-09/Ashington%20-%20Andrew%20G%20Haldane%20speech%20(24%20September%202019).pdf

- Hall, S. (2020). Social reproduction as social infrastructure. Soundings, 76(76), 82–94. https://doi.org/10.3898/SOUN.76.06.2020

- Hebbert, M. (2005). The street as locus of collective memory. Environment & Planning D: Society & Space, 23(4), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1068/d55j

- Hemingway, E. (1926). The sun also rises. Scribner & Sons. https://gutenberg.ca/ebooks/hemingwaye-sunalsorises/hemingwaye-sunalsorises-00-h.html

- Hill, F. (2021). There is nothing for you here: Finding opportunity in the twenty-first century. Mariner.

- Klinenberg, E. (2019). Palaces for the people. How social infrastructure can help fight inequality, polarization, and the decline of civic life. Vintage.

- Koster, M. (2020). An ethnographic perspective on urban planning in Brazil: Temporality, diversity and critical urban theory. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 44(2), 185–199. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2427.12765

- Kraemer, S., & Roberts, J. (Eds.). (1996). The politics of attachment: Towards a secure society. Free Association Books.

- Lamb, J., & Warre, S. (1990). The people’s store. A guide to the north eastern Co-op’s family tree. North Eastern Co-operative.

- Lear, J. (2008). Radical hope. Ethics in the face of cultural devastation. Harvard University Press.

- Lenders, J. (1930). History of the Parish of Sacriston. Gruuthuuse.

- Local Trust. (2019). Left behind? Understanding communities on the edge. https://localtrust.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/local_trust_ocsi_left_behind_research_august_2019.pdf

- MacKinnon, D., Kempton, L., O’Brien, P., Ormerod, E., Pike, A., & Tomaney, J. (2022). Reframing urban and regional ‘development’ for ‘left behind’ places. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 15(1), 39–56. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsab034

- Mah, A. (2012). Industrial ruination, community, and place. Toronto University Press.

- Manzo, L., & Devine-Wright, P. (Eds.). (2013). Place attachment. Advances in theory, methods and applications. Routledge.

- Marris, P. (1986). Loss and change (Revd edn). Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Mattilia, H.,Olssoon, P., Lappi, T.-R., & Ojanen, K. (2022). Ethnographic knowledge in urban planning – Bridging the gap between theories of knowledge-based and communicative planning. Planning Theory and Practice, 23(1), 11–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649357.2021.1993316

- Mattinson, D. (2020). Beyond the Red Wall: Why Labour lost, how the Conservatives won and what will happen next? Biteback.

- McCullough Thew, L. (1985). The pit village and the store. The portrait of a mining past. Pluto.

- Olick, J., Vinitzky-Seroussi, V., & Levy, D. (Eds.). (2011). The collective memory reader. Oxford University Press.

- Oxley, J. (1924). The birth of a movement. A tribute to the memory of Joseph Hopper. Gateshead District Aged Mineworkers Homes.

- Pike, A., Béal, V., Cauchi-Duval, N., Franklin, R.,; Kinossian, N., Lang, T., Leibert, T., MacKinnon, D., Rousseau, M., Royer, J., Servillo, L., Tomaney, J., & Velthuis, S. (2023). ‘Left behind places’: A geographical etymology. Regional Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343404.2023.2167972

- Pike, A., Dawley, S., & Tomaney, J. (2010). Resilience, adaptation and adaptability. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 3(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsq001

- Prendergast, J. (2021). Attachment economics: Everyday pioneers for the next economy. https://medium.com/onioncollective/attachment-economics-everyday-pioneers-for-the-next-economy-d0a9ac20080

- Priestley, C. (2021). Closure order on Sacriston House which plagued community. Northern Echo, 15 December. https://www.thenorthernecho.co.uk/news/19785719.closure-order-sacriston-house-plagued-community/

- Public First. (2022). Heritage and civic pride. Report for Historic England. https://www.publicfirst.co.uk/heritage-and-civic-pride-public-first-report-for-historic-england.html

- Qureshi, Z., & Fyans, J. (2021). The power of pubs. Protecting social infrastructure and laying the groundwork for levelling up. Localis. https://localis.org.uk/research/the-power-of-pubs/

- Rodríguez-Pose, A. (2018). The revenge of the places that don’t matter (and what to do about it). Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 11(1), 189–209. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsx024

- Ross, T., & Stoddart, A. (1921). Jubilee history of Annfield Plan Industrial Cooperative Society Ltd, 1870–1920. Co-operative Wholesale Printing Works.

- Scott, J. (1998). Seeing like a state: How certain schemes to improve the human condition have failed. Yale University Press.

- Sedikides, C., Wildschut, T., Arndt, J., & Routledge, C. (2008). Nostalgia: Past, present, and future. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 17(5), 304–307. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2008.00595.x

- Silver, L., Schumacher, S., Mordecai, M., Greenwood, S., & Keegan, M. (2020). In U.S. and UK, globalization leaves some feeling ‘left behind’ or ‘swept up’. https://www.pewresearch.org/global/2020/10/05/in-u-s-and-uk-globalization-leaves-some-feeling-left-behind-or-swept-up/

- Star, S. (1999). The ethnography of infrastructure. American Behavioural Scientist, 43(3), 377–391. https://doi.org/10.1177/00027649921955326

- Teti, V. (2018). Stones into bread, trans. F. Lorrigio & D. Pietropaolo. Guernica.

- Tomaney, J. (2018). The lost world of Peter Lee. Renewal: A Journal of Social Democracy, 26(1), 78–82.

- Tomaney, J. (2020). After coal: Meanings of the Durham Miners’ Gala. Frontiers in Sociology, 5, 13pp. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2020.00032

- Tomaney, J. (2023). Mrs Anne Errington of Sacriston: A Durham miners' wife between the wars. Unpublished paper, Bartlett School of Planning, University College London.

- Tomaney, J., Blackman, M., Natarajan, L., Panayotopoulos-Tsiros, D., Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, F., & Taylor, M. (Forthcoming 2023). (Re)making social infrastructure in ‘left behind’ places. Taylor & Francis.

- Tronto, J. (2015). Who cares? How to reshape a democratic politics. Cornell University Press.

- Urban Geography. (2022). Urban Geography, special issue: Social Infrastructure, 43(5). https://www.tandfonline.com/toc/rurb20/43/5

- Urban Planning. (2022). Urban Planning, special issue: Localizing Social Infrastructures: Welfare, Equity, and Community, 7(4).

- Williams, R. (1989). Resources of hope. Culture, democracy, socialism. Verso.

- Wuthnow, R. (2018). The left behind: Decline and rage in small-town America. Princeton University Press.

- Yarker, S. (2021). Creating spaces for an ageing society: The role of critical social infrastructure. Emerald.