?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Religious doctrines may guide individual attitudes and preferences, including risk behaviour among others. We estimate the effect of religion on the willingness to take risk amongst 1209 rural women in Ghana, and observe that, whereas religious affiliation influences the decision to engage in risk, it does not in any way influence the level of risk taking thereafter. Specifically, we find that relative to the non-religious, religious affiliation of a woman influences her willingness to engage in risk negatively; however, we find very little difference in such willingness to engage in risk between the different religious groups.

KEYWORDS:

1. Introduction

Risk behaviour is fundamental in explaining individual, household and firm-level decisions, and in predicting responses to various policy interventions, such as portfolio choice, education, occupation, livelihood, health insurance among others. An individual's attitude towards risk plays an important role in his/her economic decision making in any situation that involves uncertainty around a future outcome. Understanding individual attitudes towards risk is thus critical in predicting economic behaviour (Bhandari & Kundu, Citation2014; Dohmen et al., Citation2011), and thus for prescribing policy.

Religious doctrines (beliefs, attitudes, values, norms, tenets, etc.) may guide individual attitudes and preferences, including diet, marriage, investment, risk-seeking propensity among others. Inzlicht, McGregor, Hirsh, and Nash (Citation2009) assert that religious beliefs may provide the basis for understanding and acting within one's environment; and for that matter, can influence individual preferences in general. Borrowing from the ‘social identity theory’ and ‘identity theory’ in social Psychology (Greenfield & Marks, Citation2007; Stets & Burke, Citation2000; Tajfel, Citation1972),Footnote1 it can be argued that individuals belonging to a religious group behave in a particular way. Consequently, religion may lead to heterogeneity in individual attitudes, preferences and traits. Thus, risk behaviour of an individual may differ based on his or her religious affiliation.

Generally, it is believed that the non-religious are not influenced by any risk-limiting religious dogmas; hence, they may be more willing to take risk than the religious. Most religious denominations promote individual risk-averse behaviour, especially with respect to decisions about money/finance. Almost all religious doctrines in one way or the other have a strong opposition to engaging in any form of financial decisions which may be associated with high level of uncertainty, especially gamblingFootnote2 of any form such as a lottery or other games of chance. Adherents of most religions may, therefore, think about the moral or ethical implication of participating in lotteries. For instance, Islamic teachings tend to condition its followers to be risk averse in financial matters, since Qur’an 5:90Footnote3 prohibits games of chance (maysir) and speculative behaviour (Gharar). El Massah and Al-Sayed (Citation2013) argue that, Islamic finance discourages hoarding and prohibits transactions featuring extreme uncertainties and gambling. Also, trading or investing in highly risky assets due to uncertainty, and taking interest (Riba)Footnote4 are forbidden (haram) in Islam. According to some authors (Bohnet, Benedikt, & Zeckhauser, Citation2010; Hassan & Dridi, Citation2010; Hassan & Kayed, Citation2009), the Qur’an and the Islamic Law (Sharia) also discourage people (and businesses) from engaging in excessive risk-taking transactions. Hence, as a matter of principle, Sharia encourages the pursuance of risk-sharing strategies by individuals and businesses through the usage of less risky financial instruments.

Similarly, the Bible discourages adherents of the Christian faith from investing in assets which the investor sees as uncertain (Proverbs 19:2).Footnote5 Thus, indirectly the Bible promotes risk-averse behaviour. It is worth emphasizing however that the Bible does not explicitly speak against risk; and unlike the Qu’ran, the Bible does not explicitly mention betting or engaging in a lottery and it also does not specifically condemn betting or engaging in a lottery. Indeed, a couple of verses in the Bible encourage risk taking (Ecclesiastes 11:4–6, Matthew 25:14–30, 2nd Kings 7:4). Ecclesiastes 11:4Footnote6 criticizes those who are overly cautious and want to play it safe by not taking risk.

Doctrinal differences between various Christian denominations, in particular, between Catholics and Protestants with regards to gambling, may also lead to heterogeneity in individual risk behaviour. Though the current study does not focus on gambling in the strict sense, it is worth emphasizing that the divergent views on gambling/lotteries held by Catholics and Protestants may go a long way to influencing risk behaviour of the adherents of Catholicism and Protestantism. Whereas, CatholicismFootnote7 tolerates gambling activities, ProtestantsFootnote8 and PentecostalsFootnote9 have a strong moral opposition to lotteries of any form. Also as asserted by Friedman (Citation2001), Judaism makes reference to the importance of diversification. This is contained in the Talmud (Babylonian Talmud, Bava Metzia 42a).Footnote10

Notwithstanding the plethora of empirical literature on the effects of risk preferences on behaviour, Dohmen et al. (Citation2011) emphasize that risk behaviour itself still remains to a large extent, a ‘black box’, in the sense that, relatively little is known about the factors influencing risk-seeking behaviour. Though there are several empirical studies on individual risk-taking preferences, only a few include cultural factors as determinants of risk preferences (Bartke & Schwarze, Citation2008; Benjamin, Choi, & Fisher, Citation2013; Dohmen et al., Citation2011; Haneishi, Takagaki, & Kikuchi, Citation2014; Köbrich León & Pfeifer, Citation2017; Liebenehm & Waibel, Citation2014; Renneboog & Spaenjersy, Citation2012; Weber, Citation2013). What is more, very few studies on correlates of risk behaviour include religion as an explanatory variable; and those that do focus on the developed country context (For the US: Benjamin, Choi, & Strickland, Citation2010, Citation2013; Halek & Eisenhauer, Citation2001; Hilary & Hui, Citation2009; For Germany: Dohmen et al., Citation2011; Köbrich León & Pfeifer, Citation2017; Weber, Citation2013; For the Netherlands: Renneboog & Spaenjersy, Citation2012).

Halek and Eisenhauer (Citation2001), using US data, find that relative to traditional religions, being a Catholic or a Jew increases one's level of risk aversion. Bartke and Schwarze (Citation2008) analysed two possible determinants of individual risk attitudes for German individuals: nationality and religion, and found that while nationality does not significantly determine risk behaviour, religion is a significant determinant of risk behaviour. They report that religious affiliation matters, and that in religious individuals Muslims are more risk averse than Christians. Benjamin et al. (Citation2010) report that in the US, Catholics are less risk averse than Protestants and Jews. In a lottery experiment of 450 adults in Germany, Dohmen et al. (Citation2011) report that only Protestants and atheists significantly influence risk-seeking behaviour with respect to financial risk, with Protestants willing to take less risk than atheists. With respect to general risk, their results indicate that atheists are less risk averse than Protestants. In a Dutch study of religion and risk, Noussair, Trautmann, van de Kuilen, and Vellekoop (Citation2012) report a positive correlation between religiosity and risk aversion. Additionally, they report Catholics to be less risk averse than Protestants. They also report that, respondents who pray more than once a week are more risk averse, relative to those praying less frequently. However, they found no significant effect of the strength of religious beliefs on risk aversion. In another study in the Netherlands, Renneboog and Spaenjersy (Citation2012) used data from the annual Dutch National Bank (DNB) Household Survey and found a positive relationship between being Catholic and risk aversion. In an incentive-compatible experimental choice to evaluate risk aversion among a sample of 827 Cornell University students in the US, Benjamin et al. (Citation2013) examined whether there are religion-induced differences in financial risk taking. The authors show that, whereas being a Protestant reduces risk-taking propensity, risk-taking propensity increases with Catholics. In a study of cultural differences in risk tolerance in Germany, Weber (Citation2013) revealed that both religion and nationality matter for risk aversion. In particular, he concludes that Protestants and atheists are less risk averse than individuals belonging to other denominations. Köbrich León and Pfeifer (Citation2017) report a negative and significant relationship between general risk-taking propensity and religiosity in Germany, suggesting that, in general, religiosity is associated with higher risk aversion. In particular, their results revealed that Catholics, Protestants and Muslims are less risk tolerant. In terms of the effect of religious affiliation on individual financial risk attitude, they found no significant relationship among Catholics and Protestants. However, they found Muslims and traditional believers to be significantly less willing to take financial risk.

Generally, very little empirical work on risk behaviour exists in developing countries relative to developed countries (Bhandari & Kundu, Citation2014; Chinwendu, Chukwukere, & Remigus, Citation2012; Dadzie & Acquah, Citation2012; Haneishi et al., Citation2014; Liebenehm & Waibel, Citation2014; Wik, Kebede, Bergland, & Holden, Citation2004). This is particularly so in the area of religion and risk behaviour. An extensive literature search revealed very few empirical studies (in fact only two so far: Haneishi et al., Citation2014; Liebenehm & Waibel, Citation2014) in a developing country context that include religion as a covariate in explaining risk behaviour. In a field experiment conducted in Mali and Burkina Faso, Liebenehm and Waibel (Citation2014) indicate that, risk preferences are correlated with religion. In particular, the authors find that time spent in a Quaranic school is positively related to greater risk-seeking behaviour. In a study of risk attitude of farmers in Uganda, Haneishi et al. (Citation2014), included religion as part of their explanatory variables and found religion to be significant and positively correlated with risk aversion. The authors report that Muslims are more risk averse than Christians.

Aside from the fact that there is very little empirical work on the effect of religion on risk preferences, particularly in the developing country context (Haneishi et al., Citation2014; Liebenehm & Waibel, Citation2014), it is also worth emphasizing that heterogeneity in the risk preference of women, in particular, merits further examination. Although various studies have established that, women generally are less willing to take risk relative to men (Bhandari & Kundu, Citation2014; Charness & Gneezy, Citation2012; Hanewald & Kluge, Citation2014; Hryshko, Luengo-Prado, & Sørensen, Citation2011; Weber, Citation2013; West & Worthington, Citation2015), it is interesting to note that, to our knowledge no study has focused exclusively on the heterogeneity of risk preferences among women. An extensive literature search depicts a dearth of empirical evidence on using economic experiments (risk games with real monetary pay-offs) to assess the risk behaviour of rural women in general and in particular, to evaluate to what extent religion influences risk behaviour. Our current study, therefore, contributes to the literature by trying to assess the risk behaviour of rural Ghanaian women, with a focus on whether religion plays a role in explaining heterogeneity in individual risk-seeking propensity.

Analysing the effect of religion on risk behaviour of Ghanaian women in this current study makes our study unique in more ways than one. Firstly, very little empirical work on risk behaviour exists on Ghana, especially risk-taking behaviour among rural dwellers. This is particularly evident in using risk games with real pay-offs. The few studies (Dadzie & Acquah, Citation2012) that exist use hypothetical measures of risk which is not incentive compatible, hence, may not reveal true risk preferences. Our study is presumably the first to use real pay-offs to measure risk behaviour in a large sampleFootnote11 of rural Ghanaian individuals. Secondly, while various studies have looked at gender differences in risk-taking behaviour (Bhandari & Kundu, Citation2014; Charness & Gneezy, Citation2012; Hanewald & Kluge, Citation2014; Hryshko et al., Citation2011; Weber, Citation2013; West & Worthington, Citation2015), this is presumably the first study to focus exclusively on women, and in particular on rural women, when looking at heterogeneity in risk preferences. Consequently, our current study is unique owing to its gender specificity. Thirdly, this is the first study to look at the effect of religion on risk preferences, both in a developing country context, and amongst women. Lastly, we expand the set of personal and household characteristics that may influence individual risk behaviour by including social capital as part of our control variables.

While Ghana is a multicultural society with a mixture of both ethnic/tribal as well as religious groups, the International Religious Freedom Report (Citation2015), notes that, there is no significant link between ethnicity and religion in Ghana. Further, the literature has found that Ghanaians identify themselves more by their religious affiliation than by their ethnic affiliation. Langer (Citation2010) found, after conducting a general survey in Ghana that, when considering many factors including gender, language, nationality, religion, ethnicity, region of origin, ideology, locality and occupation, most Ghanaians considered religion most important in terms of their own self-perception. In fact, religion was more important than ethnicity in terms of their identity. This result is confirmed by Mc Cauley (Citation2016) who found that religious divisions in Ghana are more important than ethnic ones. In so far as it is religion that seems most important to Ghanaians’ identity, it seems plausible that their religious affiliation will influence many aspects of their decision making, be it consciously or subconsciously.

The rest of the paper is structured as follows: In the next section (Section 2), we present the methodology which looks at the data and experimental design, as well as the estimation strategy. We then present and discuss the results in Section 3. Section 4 concludes the study.

2. Methodology

2.1. Data and research setting

We use data from the Socio-economics Studies arm of the International Lipid based Nutrient Supplement Study (iLiNS) in Ghana, herein referred to as iLiNS Dyad-G-SES. The iLiNS Dyad-G-SES study is a collaborative research project between the University of Ghana and the University of California, Davis. Enrollment of women and their households into the iLiNS study was on a rolling basis over a two year period from December 2009 to December 2011. As part of the eligibility criteria into the iLiNS study, women should be at least 18 years of age and resident in the Lower Manya Krobo or Yilo Krobo districts in the Eastern Region of Ghana (the iLiNS Project site) throughout the study period. In line with the objectives of the current study, we use the Risk Aversion data and the Household Socio-economic Characteristics data on 1209 women from the iLiNS DYAD-G-SES study. The risk behaviour data were generated from a risk aversion game (RAG), immediately after the household socio-economic characteristics survey on the same day.

2.2. Experimental design: RAG

Data on individual risk behaviourFootnote12 were collected using experimental economics games (RAG) with real monetary pay-offs. The game was designed to learn something about a woman's risk behaviour, by asking her to take decisions about how much money she would like to bet. Depending on the choices the woman makes and the outcome of those choices, she will either double her bet or lose half of her bet. The game was explained to participants as not being a form of gambling or a lottery (as they would understand it in the strict sense), but rather, as a means of learning how they take decisions in the face of uncertainty. The initial approach to use the toss of a coin to determine the outcome of the game was replaced with the dice. This was because the toss of a coin was seen to be synonymous with gambling (which is normally frowned upon in typical Ghanaian societies), while the roll of a dice was acceptable as people in the area were familiar with the popular game called Ludo (a game of chance based on roll of a dice).

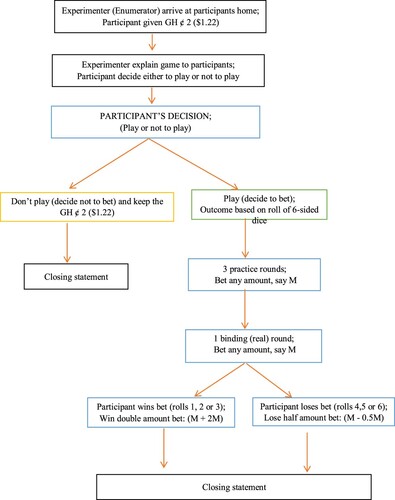

The RAG was designed as follows.

Upon arrival at the subject's home, the experimenter reminded subjects of the confidentiality of the data. The experimenter began by giving the subject GH2 (approximately $1.22, using 2011 annual average exchange rates) and informed her that the money was hers to keep. The game was explainedFootnote13 to the participant and at the end of the explanation she could either choose to play the game (decide to bet) or choose not to play the game (decide not to bet) and keep the GH

2. If the subject indicated that she was not willing to play the game, the experimenter told her the GH

2 was for her to keep, and then proceeded to the closing statement. If the subject wanted to play the game, then, in the remainder of the game the experimenter asked her to indicate how much of the GH

2 she wanted to bet (subjects could choose to bet GH

0, GH

2, or any amount in between their endowment). After she stated her bet, the experimenter asked her to roll a six-sided die to determine the outcome of her bet. Depending on her choice and the outcome from rolling the dice, the participant either doubled her bet or lost half of her bet. If she rolled a one, two, or three, she was given double the amount of money she bet. If she rolled a four, five or six, she lost half of her bet. In order to help the subject fully understand the game, the experimenter leads the respondent through three practiceFootnote14 rounds before conducting the real round. The experimenter then concluded the game by giving the subject the money she won or took back the money she lost and told her that the money she was left with was hers to keep. A flow diagram summarizing the experimental procedure is presented in Figure A1 (see Appendix).

2.3. Summary statistics

presents the sample mean (count and percentages for dummy variables), standard deviation, as well as, the minimum and maximum for individual and household characteristics, including our main variables of interest: risk preference and religion.

Table 1. Summary statistics and variable definitions.

Study participants’ age and years of schooling are on average 27 and 7 years, respectively. In terms of marital status; approximately 37% are married, 62% are in loose union and just 1% are not married (single, separated, widowed and divorced). About 20% of the sample are unemployed; and average monthly income from main economic activity is GH89 ($54). Additionally, 14% of the women are household heads; and in terms of social capital, approximately 53% are members of at least one group or association. On average, there are four people in a household, with an average dependency ratio of 0.7. In terms of household wealth, a mean score of −0.01539 was recorded for household asset index (a proxy measure of household wealth), and an average per-capita income of approximately 84 ($51). Also, roughly 13% indicated that their households were in debt.

Table A1 (Appendix) shows the cross-tabulation of religious affiliation and ethnicity. In terms of religious affiliation, with approximately 67%, Pentecostals constitute the largest religious group. This is followed by Protestants (18%) and Catholics (9%). Respondents of the Islamic faith constitute approximately 3%, and about 3% also belong to the traditional religion. Those who do not profess to any religion constitute 1%.

In terms of ethnicity,Footnote15 the bulk of the sample (76.3%) belongs to the Krobo tribe/ethnic group. Ewes and Akans make up 11.6% and 7.2%, respectively, with less than 1% (0.6%) from the Ga tribe. The remaining 4.4% belong to other tribes. It is not surprising that a greater proportion of the study women and their households are Krobos, since the survey area is part of the Krobo land of South Eastern Ghana. All the ethnic groups/tribes, except other tribes have more than half of the sample women belonging to the Pentecostal faith, followed by protestants, Catholics, Muslims, traditional and no religion, in that order. For instance, in Table A1 we see that the largest tribe, Krobo, has approximately 69% of women being Pentecostals. Protestants, Catholics and Muslims, as well as traditionalist and women not affiliated to any religion constitute about 18%, 8%, 8%, 4% and 1%, respectively, within the Krobo tribe.

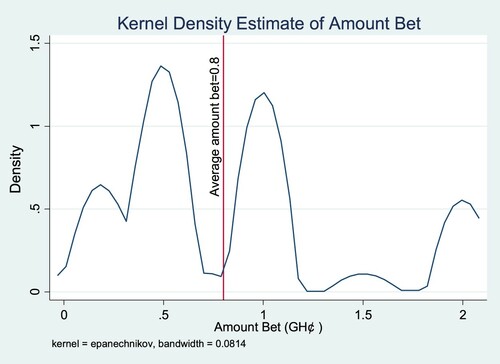

Out of the total 1209 participants, 96% chose to play the game (). In terms of individual risk behaviour; approximately 4% are categorized as ‘Not Willing to Take Risk’ (NWTR), 52% as ‘Willing to Take Moderate Risk’ (WTMR) and 44% are ‘Willing to Take High Risk’ (WTHR), respectively. As indicated earlier, NWTR women are participants who chose not to play the RAG at all. WTMR women did play the game; but their bets were below the mean amount bet. WTHR women bet either the mean amount or higher. On average, amount bet by participants was GH0.83 ($0.50), with a range of GH

0.05 to GH

2 ($0.03–$1.2). Also, less than 1% (0.6%) and 13% of respondents bet the minimum and the maximum amount respectively. The distribution of amount bet is illustrated by the kernel density in Figure A2 (see Appendix).

Table 2. Risk behaviour by religious affiliation.

2.4. Econometric framework

2.4.1. Effect of religion on the willingness to take risk

An individual's decision to play (bet) the RAG or not in itself is seen as a measure of risk behaviour. A person who is NWTR will decide not to play the game and then keep the GH2. Someone who is willing to take risk, will however, decide to play or bet in the game, and may either win or lose more money, based on the outcome of the game. Since the decision to bet or not is binary, the basic econometric estimation framework to model the effect of religion on risk-seeking behaviour is indicated as a latent variable model below:

(1)

(1)

where

is an indicator of willingness to take risk, as a binary outcome (

= 1 if an individual is willing to play/bet, otherwise, 0). Religion represents a vector of variables related to religious affiliation (Pentecostal, Protestant, Catholic, Muslim, Traditional religion and No religion). The coefficient,

measures the effect of religion on risk behaviour (willingness to take risk).

represents a vector of control variables – individual, household and other characteristics – such as; age, education, marital status, unemployment, income, wealth, social capital, household size, and previous luck, believed to influence risk-seeking behaviour. The parameter,

, signifies the strength of the impact of the control variables;

and

, are the intercept and error term, respectively. The error term is normally distributed and is independent of the covariates, summarizing all unobserved factors that affect risk behaviour with mean zero and a unity variance.

In the binary probit model, the coefficient of religion has a qualitative effect on (the dependent variable). Therefore, quantitative predictions are made only on the basis of the marginal effects of the repressors, which are derived from the estimated coefficient. In our current study since our dependent variable is

and our independent variable of interest is Religion, the marginal effect is as follows:

(2)

(2)

where

is the cumulative distribution function (CDF) of the normal distribution.

2.4.2. Effect of religion on the level of risk behaviour

As explained earlier, study participants had the choice to play (bet) in the RAG or not to play (not bet). The decision to bet, or not to bet, may result in more than two possible ordered multinomial outcomes; and hence, different risk-seeking behaviour categories. In the case of our current study, we consider three categories of risk behaviour, namely, NWTR, WTMR and WTHR. As indicated earlier, NWTR subjects did not play the RAG, and hence did not bet at all. WTMR subjects played the RAG but bet below the mean amount bet. WTHR subjects played the RAG and bet either exactly the mean or above the mean.

We assume an unobserved latent variable , corresponds to the individual risk behaviour category in the game. The effect of religion on risk behaviour for individual i =1, 2, … , is therefore given by the following equation:

(3)

(3)

where

are unobserved or latent risk behaviour categories, signifying NWTR (0), WTMR (1) and WTHR (2). Hence, the higher the value of

, the more likely the individual is willing to take risk, and vice versa. All the other variables (

, Religion,

,

and

) are as explained earlier.

As is the case of all discrete choice models, in the ordered probit model, the coefficient of the explanatory variables have a qualitative effect. Therefore, quantitative predictions are made only on the basis of the marginal effects of the regressors, which are different from the coefficients. In our case of three categories, the marginal effects of changes in the regressors are as follows:

(4)

(4)

(5)

(5)

(6)

(6)

2.4.3. Effect of religion on amount of risk (bet)

How much a woman is willing and able to bet, is also, an indication of her risk-seeking behaviour. But because some subjects chose not to bet, estimating the effect of religion on risk behaviour using the amount bet as the dependent variable will mean that, there will be a problem of censoring. Hence a tobit regression is considered appropriate for the situation. The amount risk () indicate different levels of risk behaviour, where the higher the amount the more willingness to take risk and vice versa. For individual i=1, 2, … ,; we estimate the model below:

(7)

(7)

where

is the amount bet which represents the unobserved or latent risk behaviour. The other variables are as explained earlier.

It is worth noting that we observe the variable which is defined to be equal to the unobservable or latent variable

, whenever the unobserved variable is above zero, and zero otherwise:

(8)

(8)

The estimated coefficients of the tobit regression are the marginal effects of a change in Religion on the observed variable (

) as depicted below:

(9)

(9)

As a starting point, we first show the results for an ordinary least square (OLS) regression, using the amount risk as the dependent variable, and then, show the tobit results as an alternative model which accounts for censoring. As a robustness check, we also estimate a Heckman selection two-step model.

2.5. Definition of variables and expected signs

presents the definitions (and the expected signs) of both the dependent and explanatory variables used in modelling the effect of religion on risk behaviour.

2.5.1. Dependent variables

Risk behaviour: We have three dependent variables, because we use three different estimations (binary probit, ordered probit and tobit). The dependent variable for the binary probit, WTR, is a binary or dichotomous variable, where; WTR = 1 if the subject is willing to take risk, otherwise WTR = 0. The dependent variable for the ordered probit, Risk, is a multinomial ordered categorical measure of risk where, 0 signifies NWTR (subjects who did not bet at all), 1 for WTMR (subjects who bet below the mean amount bet) and 2 for WTHR (subjects who bet either the mean or above the mean). The dependent variable for tobit, AMTrisk, is a continuous variable indicating the total amount bet by participants in the game.

2.5.2. Main explanatory variable of interest

Religion: With respect to religion, our main explanatory variable of interest, subjects are grouped based on their adherence to the major religious groups in Ghana. To capture the effect of religion on risk behaviour, we use six different dummy variables (= 1 if woman is a member of the religious group and 0 otherwise) to represent various religious group affiliations. These classifications are guided by the Ghana Statistical Service (GSS)Footnote16 groupings, based on how close the beliefs and or doctrines of the various religious denominations are. The religious affiliation variables used in this current study include Pentecostals (Pentecost and Charismatics), Protestants (Methodist, Presbyterian and Anglican), Catholics, Muslims, Traditional religion and No religion. Adherents of various religious faiths may internalize the doctrines of their respective religions. In this regard, since almost all the various religious groups in one way or the other have strong opposition to engaging in any form of highly risky and speculative ventures because of uncertainty in outcomes (lotteries, speculative investments, etc.), we expect religious affiliation to be negatively related to willingness to take risk, relative to the non-religious. However, we expect adherents of the Islamic faith to be relatively less willing to take risk compared with the others (Pentecostals, Protestants, Catholics and traditionally religious). This is because Islamic law (Sharia) and the Qu’ran take a much stricter stand against speculative behaviour, especially in financial matters.

2.5.3. Control variables

Age: A subject's age is measured in completed years as a continuous variable. Generally, risk-seeking behaviour is considered to decrease with age as explained within the context of the lifecycle risk aversion hypothesis. The life cycle hypothesis posits that the further a person is from retirement, the more risk he or she is willing to take in their investments. After retirement, labour income is replaced by assets income and a person is not willing to take more investment risks (Bellante & Saba, Citation1986; Lin & Grace, Citation2007). Other studies that show that risk-seeking behaviour decreases with age are: Hira, Loibl, and Schenk (Citation2007); Chinwendu et al. (Citation2012) and Weber (Citation2013). There is also evidence that risk-taking behaviour increases with age. As noted by Dadzie and Acquah (Citation2012) older women are more likely to have accumulated more wealth than younger ones and are also likely to have a wider or greater social network, which can serve as a source of fallback strategies or traditional insurance in the process of decision making. Studies such as Hryshko et al. (Citation2011); Dadzie and Acquah (Citation2012); Hanewald and Kluge (Citation2014); West and Worthington (Citation2015) show an increase in risk-seeking behaviour with age.

Marital status: Three different dummy variables (married, loose union and not married)Footnote17 are used to represent marital status, where ‘not married’ is the base category. There are two schools of thought about the nature of the relationship between marital status and risk attitude. One school of thought asserts that married individuals have greater risk-taking propensities, while another suggests the opposite (Becker, Citation1974; Becker, Landes, & Michael, Citation1977; Jianakoplos & Bernasek, Citation1998; Roszkowski, Snelbecker, & Leimberg, Citation1993). The marriage search-theoretic models explain that where individuals view marriage as a way to self-insure against income risks, risk-loving individuals would marry later relative to risk-averse individuals. As argued by Bhandari and Kundu (Citation2014) marital status risk attitude relationship is ambiguous, hence, it is expected that there will be either a positive or a negative effect of marital status on risk-seeking behaviour.

Education: Education is measured by the number of completed years of schooling in formal education. Education is expected to be positively correlated with willingness to take risk, ceteris paribus. Generally, educated individuals show a lower level of risk aversion as postulated by Shaw (Citation1996) in his human capital theory; where he suggests that human capital acquisition is an inverse function of risk aversion.

Unemployment: A dummy variable is used to represent the unemployment status of a woman (1 = unemployed and 0, otherwise). The unemployed have higher income uncertainties and lower disposable income. Therefore, a negative effect of unemployment on willingness to take risk is hypothesized, ceteris paribus.

Income: Two income variables have been used in this study. The first income variable is individual income, measured as a continuous variable of the total monthly income of the women participating in the risk behaviour game. The second income variable is the household income variable, measured using per-capita income, also as a continuous variable. Theoretically, attitudes to risk are expected to increase with income (Grable, Lytton, & O’Neill, Citation2004; Riley & Chow, Citation1992), hence, income is expected to be positively correlated with willingness to take risk.

Household wealth: The household asset indexFootnote18 is used as a proxy measure of household socio-economic status, based on ownership of a set of assets. The asset index was constructed using principal component analysis (CPA) of household ownership of a set of assets such that a higher score indicates a better relative socio-economic status (Vyas & Kumaranayake, Citation2006). Just like income, theoretically attitudes to risk are seen to increase with wealth (Grable et al., Citation2004; Riley & Chow, Citation1992). Hence, household wealth is expected to be positively correlated with the willingness to take risk.

Household head: A dummy variable is used to represent household headship (= 1 if a woman household head, 0 otherwise). The study hypothesizes a positive relationship between household headship and being willing to take risk. Household heads are generally considered to be risk-loving because being a household head entails taking certain stringent and risky decisions and having responsibilities on behalf of all other household members.

Social capitalFootnote19: Social capital is measured as a dummy variable, where, 1 means being in a group or association and 0 otherwise. Social capital may serve as a means of traditional insurance, diversification, fallback strategies or coping opportunities. Therefore, it was expected that social capital would be positively correlated with being willing to take risk.

Household debts: Generally, debt tends to make an individual behave in a conservative manner especially in relation to financial matters; this study, therefore, hypothesizes household debt would decrease willingness to take risk. Household debtFootnote20 is measured using a dummy variable of whether the household borrowed money or not.

Household sizeFootnote21: Household size is a continuous variable, and is measured as the total number of members in a participant's household. The total number of household members may represent labour force for the household, and hence could be viewed as a wealth variable, providing insurance, and would thus have a positive effect on risk-seeking behaviour. Alternatively, a larger household size means higher consumption needs and more people to feed, which may decrease risk-seeking behaviour. Consequently, the study expected household size to have an ambiguous (negative or positive) effect on risk behaviours. As such, household size is included in the regression without any a priori expectation of the sign.

Dependency ratio: Age dependency ratioFootnote22 is also measured as a continuous variable. In the study, a negative effect between dependency ratio and willingness to take risk was expected because higher dependency ratio means more people to feed, which therefore may decrease risk seeking.

Previous luck: It is believed that past experiences would influence current or future preferences, including risk preferences. Hence, a participant's previous risk-seeking experience was expected to influence her bet in the final or actual round of the risk behaviour game. To ascertain whether past risk-seeking experience has a significant effect on current risk behaviour, a previous lack variable was included as a proxy for previous risk-seeking experience. Previous luck is measured using the outcome of the last (third) practice round before the actual or final round of the RAG. The third practice round was used because the last practice round would be a good indication of accumulated learning or experience. The previous luck variable takes a value of −1 when the subject bets and loses in the third practice round; 1 when she bets and wins; and 0 when she does not bet at all. Past risk-seeking experience is hypothesized to influence willingness to take risk, ceteris paribus, positively. An earlier study in India by Binswanger (Citation1980) and a much later one by Wik et al. (Citation2004) in Zambia are the only studies found in the literature to have included a previous luck variable. Both studies also found a positive effect of previous risk-seeking experience on risk behaviour.

Ethnicity/tribe: The relationship between risk and religion may potentially be affected by tribal/ethnic identity, since the lines between religious and tribal identity are often vague. Hence, in order to assume away the influence of tribal identity, we included an ethnicity dummy in all our regressions estimations. We choose the Krobo tribe as the reference group simply because it is the largest tribe.

3. Results and discussion

Before we move on to our main regression results it important to have a look at bivariate relationships between risk behaviour and religion.

3.1. Risk behaviour by religious affiliation

shows the risk behaviour categories (WTHR, WTMR and NWTR) of the study women per their religious affiliation. A greater proportion of Pentecostals are WTMR (53.0%), followed by WTHR Pentecostals (43%) and then NWTR (4%). It can be seen that an equal proportion of Protestants (48%) are WTMR or WTHR. Exactly half (50%) of Catholics are WTMR and about 46% are WTHR. For adherents of the Islamic faith, 57% are WTMR, followed by WTHR (37%) and NWTR Muslims (7%). Similarly, for women belonging to a traditional religion, a little over half (54%) are WTMR. Traditionalists who are WTHR and NWTR constitute 44% and 3%, respectively. It is interesting to note that, none (0%) of the non-religious women are NWTR. The shares of women that are WTMR and WTHR among non-religious women are equal (50% each). It is also evident from that on the whole, the proportion of women NWTR professing the Islamic faith (7%) are more than those in the other groups (Pentecostals, Protestants, Catholics, traditionally religious and non-religious). Additionally, the proportion of Catholics that are NWTR (4%) are more than Protestants (3%), but lower than Pentecostals (5%). In the same vein, in terms of WTMR, the proportion of Muslims (57%) are more than any of the Christian denominations (Pentecostals, Protestants and Catholics), as well as, the traditionally religious and non-religious. Conversely, a lesser proportion of Muslims (37%) are WTHR, compared with Pentecostals (43%); traditionally religious (44%), Catholics (46%); Protestants (48%) and non-religious (50%).

3.2. Endogeneity and estimation issues

Before we present and discuss our regression results, we wish to comment on a few estimation issues relating to endogeneity concerns and the specification of our models.

An individual's religious affiliation is mostly inherited from previous generations (mostly parents); and fundamentally remain unchanged (Guiso, Paola, & Luigi, Citation2006; Köbrich León & Pfeifer, Citation2017). We wish to emphasize that this is true for Ghana, where, religion for the vast majority is inherited from birth. Hence, in Ghana religious affiliation is typically constant overtime and the effect of religious conditioning is strong and lifelong. Individuals are born into various religious groups, and most often do not change such affiliations. Therefore, we assume religion to be exogenous.

A test of the specification of our binary probit and ordered probit models using the Ramsey's Regression Equation Specification Error Test (RESET) indicate that both models are correctly specified. With respect to our tobit model, the link test confirms that there is no misspecification.

3.3. Regression results

Because the results of the binary probit, ordered probit and tobit regression coefficients just give a qualitative effect, in presenting and discussing our results, we focus on the average marginal effects () which enables us to give quantitative effects. We use six categories of religious affiliation in our estimation namely; Pentecostal, Protestants, Catholics, Muslims, Traditional and Non-religious. In all our estimations the Non-religious are the reference category.

Table 3. Effect of religion on risk-seeking behaviour (with controls).

As expected, the binary probit results (, column 1) indicate that religion has a statistically significant negative effect on the likelihood of a woman's willingness to take risk (WTR). In particular, relative to a non-religious woman, being a Pentecostal decreases the likelihood of WTR by 28.2 percentage points. Likewise, relative to the non-religious, the WTR of Protestants and Catholics are 26.2 and 27.1 percentage points lower respectively. Also, being a Muslim decreases WTR by 27.1 percentage points relative to the non-religious. With respect to adherents of a traditional religion, we find a 26.5 percentage point decrease in willingness to take risk relative to the non- religious. It is evident from that all the religious groups show a statistically significant negative effect on WTR, with no significant difference in this regard between the various religious groups.

Our results corroborate earlier studies that also observed various religious denominations to be less willing to take risk (Bartke & Schwarze, Citation2008; Köbrich León & Pfeifer, Citation2017; Noussair et al., Citation2012; Renneboog & Spaenjersy, Citation2012).

Columns 2, 3 and 4 of show the ordered probit regression results. In our ordered probit regression, the dependent variable comprised of three ordered multinomial risk behaviour categories 0, 1 and 2; signifying NWTR, WTMR and WTHR, respectively. The results (, columns 2–4) depict that none of the religious affiliations variables are statistically significant. This is an indication that degree or levels of risk behaviour (NWTR, WTHR and WTMR) is not in any way explained by religious affiliation, at least, in the context of our ordered probit estimation.

As indicated earlier, conditioned on a subject's decision to play the RAG; we ask how much a woman is willing to risk (AMTRisk) as an indicator of her willingness to take risk. Hence, we also use the amount bet as a measure of risk behaviour. As a starting point, we show the results for an OLS regression (column 5), and then, as a robustness check, we account for censoring by estimating a tobit regression (column 6) and then, a Heckman two-stage regression as a further check (column 7). It is worth noting that the OLS specifications are robust, at least qualitatively, to using the alternative tobit specification. It is interesting to note that the results of all the three estimated models (OLS, tobit and Heckman selection) show that none of our religious affiliation variables are statistically significant; implying that, again, religion does not explain the degree or level of risk behaviour (the amount risk). Given the very small number of zeros in the data (few individuals who chose not to play the game); it is not surprising that the OLS results are very close to the tobit results.

In summary, our results show that religion is statistically significant in explaining risk behaviour only in our binary probit model, but not in our ordered probit, tobit, OLS and Heckman regressions. This implies that whereas religion influences willingness to take risk, it does not in any way influence the degree or level of risk behaviour once the decision to engage in risk has been taken.

3.4. Effect of other individual and household characteristics on risk behaviour

Although religion is not statistically significant in explaining risk behaviour in our ordered probit, OLS, tobit and Heckman models, it is clear from the results that other covariates (control variables) significantly explain the degree or level of risk taking. Thus, the effect of religious affiliation on willingness to take risk, as well as, the degree or level of risk taking depends on certain individual and household characteristics.

Turning to our control variables, the results in depict that whereas age is not statistically significant in explaining risk behaviour in our binary probit (column 1) or the OLS, tobit and Heckman models (columns 5, 6 and 7), in the ordered probit, age has a significant positive effect on risk behaviour (columns 2, 3 and 4). Age increases the probability of being WTHR by about 4.06 percentage points. Thus, as age increases by one unit an individual is more likely to have a higher risk-taking propensity. As noted by Dadzie and Acquah (Citation2012) older women are more likely to have accumulated more wealth than younger ones and are also likely to have a wider or greater social network, which can serve as a source of fallback strategies or traditional insurance in the process of decision making. Whereas our results confirm earlier studies (Dadzie & Acquah, Citation2012; Hanewald & Kluge, Citation2014; Hryshko et al., Citation2011; West & Worthington, Citation2015), it also conflicts with others studies with respect to age (Chinwendu et al., Citation2012; Hira et al. Citation2007; Weber, Citation2013).

The ordered probit and tobit results also depict a statistically significant non-linear effect of age on risk-taking behaviour, though the magnitude is very small (less than 0.1% in all cases). This is indicated by a negative significant marginal effect for WTHR (0.08 percentage points decrease). It is interesting to note that, although age is not statistically significant in our OLS, tobit and Heckman regressions, age squared has a significant negative effect (at 10% level) on the amount bet in the tobit regression. Notwithstanding the fact that the effect size of the age squared variable is very small, the results imply that ceteris paribus; the effect of age on willingness to take risk decreases as age increases. Just as we find in our current study, Bhandari and Kundu (Citation2014) also found a positive but non-significant effect of age on risk-seeking behaviour and a negative significant effect of age squared on risk-seeking behaviour. Other studies that also found similar results include Cohen and Liran (Citation2007), Faff, Mulino, and Chai (Citation2008), Lin (Citation2009), Picazo-Tadeo and Wall (Citation2011).

Our marital status variables are statistically significant in explaining risk-seeking behaviour only in the binary probit regression, but not in the ordered probit, OLS, tobit and Heckman regressions. From (column 1) married women and those in informal union are respectively 30.75 and 31.27 percentage points less likely to be willing to take risk relative to unmarried women. Our study substantiates earlier studies that report that married individuals are less likely to be risk loving (Grable & Roszkowski, Citation2007; Hanewald & Kluge, Citation2014; Weber, Citation2013).

In terms of the employment status of women, we find a statistically significant effect of unemployment in the ordered probit, OLS, tobit and Heckman regressions; but not in the binary probit regression. Generally, it is assumed that unemployed individuals are less risk seeking since they have lower disposable income and higher income uncertainties (Anbar & Eker, Citation2010; Weber, Citation2013). However, contrary to the general belief, our results indicate that unemployed women are more willing to take risk as indicated by a positive significant coefficient for risk-seeking propensity in both the ordered probit and tobit regressions. Our results confirm the job search-theoretic model (Feinberg, Citation1977; Lippman & McCall, Citation1976; Pissarides, Citation1974), which predict a positive (negative) relation between willingness to take risk (NWTR) and unemployment; implying that the unemployed are more likely to take risk. Unemployment is sure to have immense sociological as well as psychological impact on those experiencing it (Diaz-Serrano & O’Neill, Citation2004). Hence, the current results can also be explained by the fact that the unemployed experience adverse situations (the experience of challenging life events and circumstances), thereby conditioning them to be willing to take risk. Further, because of the uncertainties in future income, the unemployed bet more (higher) relative to the employed, because intuitively, the unemployed see the lottery as a chance to get more money so they try to bet higher thinking they might be lucky.

As expected, both our ordered probit and OLS, tobit and Heckman results show a positive statistically significant effect of social capital on willingness to take risk (). The ordered probit results depict that social capital increases the propensity to take risk by 6.57 percentage points. Our present study arguably is the first in the empirical literature to establish a significant effect or relationship between social capital and willingness to take risk.

Household headship is also seen to be statistically significant in all our regression estimations. In the binary probit results, being a household head increases the probability of willingness to take risk by 9.67 percentage points. If a woman is a household head she is 7.72 percentage points more willing to take risk as indicated by the ordered probit results (column 2). Similarly, the tobit regression results (column 6), depicts a positive significant effect of household headship on being willing to take risk. All things being equal, if a woman is a household head, she bets 0.103 more; implying that, ceteris paribus, being a household head increases risk-seeking propensity. This is not surprising, because, position of authority enables a person to take risky decisions compared to those who do not have authority.

Turning to household characteristics, dependency ratio is statistically significant only in the binary probit regression, with a 2.20 percentage point decrease in the probability of willingness to take risk. This indicates that women from households with a higher proportion of dependents are less willing to take risk, compared with those from households with fewer dependents. Household size is positive and statistically significant in the binary probit and tobit regressions. The reason for the positive effect of household size on risk-seeking behaviour can be explained by the fact that the total number of household members may represent labour force for the household, and hence could be viewed as a wealth variable, providing insurance, diversification and or coping opportunities.

We control for previous luck only in the ordered probit, OLS, tobit and Heckman models as the variable is not available for those who chose not to play the RAG. The results (columns 2–7) indicate that previous luck is statistically significant in explaining the level of risk behaviour. These results are an indication that individuals who won in the last practice round are more willing to take risk, all things being equal. The expected positive significant effect of previous luck may suggest that participants who won in previous rounds are updating their subjective probabilities in favour of winning as they move to the final round of the game. It is interesting to note that the previous luck variable was highly significant (at 1% level), and has the largest impact as indicated by the large marginal effects in the regressions compared with all other covariates in our current study. This, therefore, is suggestive of a strong impact of previous luck on risk-seeking behaviour. It is worth highlighting that an extensive literature search revealed very little empirical work that included previous luck variable in explaining the correlates of risk-seeking behaviour. Only the earlier study in India by Binswanger (Citation1980) and a much later one by Wik et al. (Citation2004) in Zambia were found in the literature to have included a previous luck variable. Both studies also found a similar positive effect of previous risk-seeking experience on risk behaviour.

3.5. Sample limitations

We wish to emphasis that, this study is not without limitations. Hence, before concluding and discussing the implications of our results, we highlight the limitations of the study. First, the study population in our risk behaviour game comprised of women who were recruited as part of the iLiNS Dyad Ghana nutritional intervention trial. One of the main inclusion criteria for a woman to be part of iLiNS Dyad Ghana study is that, she should be in her reproductive years (18 years and above) and also resident in the Yilo and Lower Manya Krobo districts of Ghana. Thus, our study population is certainly not a random sample of women in Ghana as a whole. Hence, to the extent that subjects who participated in the RAG were exclusively women recruited from just two districts out of the current total of 216 districts in Ghana, caution must be exercised in attempting to generalize these results to the entire women population of Ghana. Finally, since by design the sample was restricted to a rural population, it is not clear whether the results might be similar or different if urban women were included in our sample. Consequently, these limitations may have implications for the generalizability of our result. Hence, we do not seek to make generalizations of our findings, as external validity is not possible, since the sample is not a representation of all women in Ghana.

4. Conclusions

With the earlier external validity concerns and other limitations notwithstanding, we wish to highlight that important inferences can be made from our findings; which may provide valuable insights into heterogeneity of risk behaviour of rural women. It is worth emphasizing that one of the strengths of our current study lies in its gender specificity, owing to the fact that we focus on risk behaviour of rural women. Most risk preference studies are not gender specific, as they either focus on both men and women or on a particular group of people (farmers, managers, household heads, etc.).

We find robust evidence that religion, measured by religious affiliation, is negatively correlated with the decision to engage in risk, but not in determining the level or degree of risk taking once the decision has been made to engage in risk. With respect to the decision to engage in risk, while religious women are less willing than non-religious women to engage in risk, the differences between the various religious groups in this regard are not significant. Overall, the result of this study has important implications for understanding and predicting the effect of religion on individual economic behaviour among women in the study area, especially with respect to risk-related decision making. We, therefore, contribute to the existing empirical literature by providing evidence on the effect of religion in explaining heterogeneity of risk-seeking behaviour of women. Arguably, as far as we are concerned, our study is one of the few in a developing country context, if any at all, that principally focuses on the effect of religion on risk behaviour; and in particular risk behaviour of women.

Our results have implications for policy and future research. Religious beliefs normally shape individual values and economic behaviour, and in the long run affect the macro economy. Therefore, any policy design and implementation process that are seen to be risk induced such as uptake of public health insurance schemes among others, may affect individual economic behaviour and outcomes; and therefore should take into consideration the religious background of women. Additionally, as suggested by Cox and Harrison (Citation2008), it is recommended that governments and NGOs contemplating the design and implementation of new interventions especially targeted at women such as public health insurance enrollment, employment schemes, new preventative health products, savings or investment products should take into consideration religious affiliation. Aside from religion, other individual and household factors such as age, marital status, employment status, household headship, dependency ratio, household size, social capital and previous experience should also be taken into consideration in coming out with policies and programmes that are indirectly or directly influenced by risk and uncertainty.

Also, we aim in future studies to further explore the evidence that social capital and previous luck influence risk behaviour to ascertain the veracity of our results. Also, as indicated earlier in our current study our measure of religion is religious affiliation. An individual's level of risk could be determined by his or her level of religiosity. Hence, future studies could, therefore, explore religiosity variables such as frequency of prayer, specific believes, religious organizational membership, commitment and participation in religious activities.

Acknowledgements

We thank the iLiNS DYAD-G management team and the iLiNS Steering Committee for allowing us to use the data. Besides, we wish to acknowledge the work of the iLiNS SES Team especially Travis Lybbert and Katherine Adams for assisting with the study design, the iLiNS DYAD-G SES enumerators for their work in the field, as well as, the data entry personnel. Lastly, we thank the women who participated in the study. All authors listed have contributed sufficiently in the planning, execution and analysis of the study to be included as authors and all authors have read and approved the final version submitted. All errors are those of the authors alone.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Emmanuel Ayifah

Dr. Emmanuel Ayifah is an Economist with remarkable experience in research, monitoring and evaluation, project cycle management, as well as development cooperation; and with field experience in Afghanistan, Burkina Faso, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and South Africa. He received his PhD from the University of Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. He is currently the Deputy Country Director of SEND GHANA, a policy research and advocacy organization. Prior to his current position, he served as a Postdoctoral Researcher/Monitoring and Evaluation Specialist at the Chair of Econometrics/Center for Evaluation and Development (C4ED), Department of Economics, University of Mannheim, Germany. His research interest is in Development Economics, Health Economics, Behavioral and Experimental Economics, as well as policy/programme evaluation. He has published in accredited journals such as agricultural economics, Journal of nutrition, Maternal and child nutrition, Malaysian journal of public health medicine, Retrioviology among others.

Aylit Tina Romm

Dr. Aylit Tina Romm is a senior lecturer in the School of Economics and Finance at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. She received her BSc degree in Mathematics and Economics, Bcom (hons) and Master's degree in Economics all from the University of the Witwatersrand. She received her Phd in Economics from the University of Cape Town in 2011. Her research interests include Life cycle savings behavior, the economics of retirement, all areas of behavioural economics and decision theory. She has published academic articles both in the applied and theoretical domains of economics and prides herself on her capabilities in both these areas.

Umakrishnan Kollamparambil

Prof Umakrishnan Kollamparambil is the Head of the School of Economics and Finance (SEF), University of the Witwatersrand. She obtained her doctoral degree in Economics from the Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU), New Delhi in 2004. She is as a Development Economist with research interest in Subject Wellbeing, Migration and Inequality in the South African context. She has published widely in esteemed international journals like the Journal of Development Studies, Journal of Happiness Studies, Development Policy Review, International Migration, Development Southern Africa, Journal of Public Health, African Development Review etc. She is engaged in teaching Econometrics at both under-grad and post-grad levels and also offers a Masters level course on Development Economics. Prof Umakrishnan Kollamparambil is endowed with rich experiences in research supervision having successfully supervised to completion 4 PhD candidates and over 20 Masters students. She is on the editorial board of the African Review of Economics and Finance. She holds membership of the Economics Society of South Africa (ESSA) and The Society for the Study of Economic Inequality (ECINEQ). She lives in Johannesburg with her husband and seven year old son.

Stephen A. Vosti

Prof. Stephen A. Vosti is Adjunct Professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics at the University of California, Davis. He received his PhD in economics from the University of Pennsylvania, and was a Postdoctoral Fellow with the Rockefeller Foundation in Brazil. He was a Research Fellow at the International Food Policy Research Institute, where he managed international research projects aimed measuring the effects of changes in land use and land cover on poverty, economic growth and environmental sustainability, and on identifying the roles of public policy in managing these trade-offs/synergies. Vosti currently leads a team comprised of nutritionists, geographers, and economists in developing tools to enhance the cost-effectiveness of micronutrient intervention programs and policies in developing countries, with special focus on Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ethiopia, Haiti, Nigeria and Senegal. Vosti has substantial field-based research experience in Bangladesh, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Ecuador, Ethiopia, Ghana, Kenya, Malawi and Pakistan.

Notes

1 Stets and Burke (Citation2000) posit that social identity theory emphasizes one's identification or association with a particular group, while identity theory examine the roles or behaviors persons enact as members of a group.

2 In general gambling is frowned upon by all religions: Budhism advocates six evil consequences for indulging in gambling; Although the Bible does not explicitly say, ‘thou shall not gamble’, Christians also consider gambling to be based on the love of money and the promise of quick, easy riches; therefore, condemn the act. Engaging in any form gambling result in punishment under Islamic law, since gambling is considered ‘haram’ (forbidden) in Islam.

3 ‘O you who believe, intoxicants, and gambling, and the altars of idols, and the games of chance are abominations of the devil; you shall avoid them, that you may succeed’ (Qur’an 5:90.013).

4 Riba, in Islam is seen as a form of extortion, hence forbidden . Literally, it means ‘an excess’ and interpreted as ‘any unjustifiable increase of capital whether in loans or sales’ (El Massah & Al-Sayed, Citation2013).

5 ‘Desire without knowledge is not good, and whoever makes haste with his feet misses his way’ (Proverbs 19:2).

6 ‘He who watches the wind will not sow and he who looks at the clouds will not reap’(Ecclesiastes 11:4).

7 The position of the Catholic Church on gambling is summarized in the New Catholic Encyclopedia: ‘A person is entitled to dispose of his own property as he wills … so long as in doing so he does not render himself incapable of fulfilling duties incumbent upon him by reason of justice or charity. Gambling, therefore, though a luxury, is not considered sinful except when the indulgence in it is inconsistent with duty’ (Gale Group, Citation2003).

8 The United Methodist Church’s 2004 Book of Resolutions stated its views on gambling which is typical of many Protestant churches: ‘Gambling is a menace to society, deadly to the best interests of moral, social, economic, and spiritual life, and destructive of good government. As an act of faith and concern, Christians should abstain from gambling and should strive to minister to those victimized by the practice’.

9 The general Board of the united Pentecostal church international in 1994 issued a position paper on gambling: Biblical faith with its emphasis on loyalty to God and it calls to a life trust tolerates no bowing of the knee to luck and no dependence on chance.

10 Diversification- dividing one's assets into thirds: one third in land, one third in business, and one third kept liquid: Talmud (Babylonian Talmud, Bava Metzia 42a).

11 The large sample also gives a good statistical power as most experimental risk studies with real monetary payoff often use smaller samples because it is expensive to undertake.

12 The current paper assumes that individuals have a certain degree of risk aversion and a propensity to risk-taking. Following from the mainstream literature on experimental studies (Andersen, Harrison, Lau, & Rutstrom, Citation2008; Chuang & Schechter, Citation2015; Drichoutis & Vassilopoulos, Citation2016), in this study, we assume stability of individual risk preference (constant risk behaviour). In a field experiment to examine temporal stability of risk preferences, Andersen et al. (Citation2008) reported that generally risk attitudes did not change over a 17-month span after a repeated risk aversion elicitation task. Also, in a panel of subjects over a three-year period, Drichoutis and Vassilopoulos (Citation2016) found aggregate stability of six measures of risk over time, and also showed remarkably high individual stability over the examined period. Thus, in concert with the theoretical assumptions and earlier studies, this current study assumes that a woman's risk-taking propensity is the same across the entire period of data collection. Again, the assumption of constant risk over time could be seen in the light of the relationship between risk behaviour and religious affiliation. It is worth noting that religious affiliation, which is typically constant over time, is a relevant instrument for risk-taking propensity. Individuals are born into various religious groups, and most often do not change such affiliations. Indeed, the effect of religious conditioning is strong and lifelong; hence, individuals are forever bound and influenced by religious teachings and tenets. The current results show that generally religion influences risk behaviour. Therefore, to the extent that religion is lifelong, and individuals generally do not change their religion of birth, it is reasonable to assume that risk behaviour would be constant over time. However, it is possible that people make different kinds of decisions depending on the sphere in which they make decisions, and on the amounts of gains and losses. For instance, some people may buy lottery tickets, but be very risk averse in, say, major life decisions. Chuang and Schechter (Citation2015) note that, theoretically, individual preferences are assumed constant; and if preferences do vary over time, then it is because of shocks faced by the individual. We acknowledge that this is an issue that the current paper cannot address.

13 According to the principle of Salience in experimental design (Smith, Citation1976, Citation1982) the connection between actions and payoffs should be clear to subjects. Therefore, in order to ensure maximum comprehension the experimenter (enumerator) takes time to clearly explain the game to the subject. The experimenter will also demonstrate that the roll of the die is random (50/50 chance of winning or losing a bet) by rolling the die about 10 times in a row, each time declaring the outcome of the roll (the number on top).

14 In experimental designs, it is very important to use repetition of task in order to maximize subject comprehension (Friedman Citation1998).

15 The sample data do not have ethnicity/tribe data. However, we have information on the main language spoken in the household. Since most tribes are grouped along ethnolinguistic lines in Ghana, and tribal identity determines language, we use the main language spoken in the household as proxy for ethnicity.

16 Generally the main classification of religious groups in Ghana according to the Ghana Statistical Service include Catholics, Protestants (Methodist, Presbyterian and Anglican), Pentecostals (include charismatics), Muslims, Other Christian (Adventists, Later day Saints, Jehovah Witnesses, etc.), Traditional religion, other religion (Hindus, Budhist, Eckhankar, Jews etc.) and No religion.

17 It is worth noting that most empirical studies only use just one dummy variable to represent marital status (mostly 1 for married, 0 otherwise). We wish to state that it is very common to find people in a long-term relationship (even to the extent of raising children together) though they may not be legally married (either by ordinance or customary). This is commonly so in the study area for this current study, but it is not typical of the general Ghanaian society. Hence, it is important to separate these two categories of marital status (married and loose union) as strictly or technically speaking they do not mean the same. Marriage by ordinance or customary is more binding and hence, cannot be easily dissolved (this would require the legalities of either divorce or separation) compared with a situation where people might be in less legally binding long-term relationships. Most studies fail to use these categories of marital status in their regressions possibly because of data limitations. Respondents were asked to indicate whether they are actually married, or in a loose union or divorce, separated etc. Hence, three different dummy variables for marital status (married, loose union, and not married) are included in this study.

18 The assets included in the index were radio, television, refrigerator, cell phone, stove, lighting source, drinking water supply, sanitation facilities, and flooring materials.

19 Respondents were ask to indicate which of the following associations or groups they belong to: Susu, , Farmer's Association, sewing, singing, music, church, informal traders’, income-earning, mothers/men's support groups.; School, developmental committees; , Queen Mother's Association; Market Association.

20 For household debt, the following question was asked: ‘Over the past twelve months, did you or anyone else in your household borrow on credit from someone outside the household or from an institution?’.

21 Following the Ghana Statistical Service definition as used in various surveys (GLSS, GDHS, MICS, etc.), household members are defined as people who have been regularly sleeping in the same dwelling and sharing food from the same cooking pots for at least the last three months.

22 Age dependency ratio: measured by the ratio of number of dependants (below 18 years + above 60 years) and non-dependants (18–60 years).

References

- Anbar, A., & Eker, M. (2010). An empirical investigation for determining of the relationship between personal financial risk tolerance and demographic characteristics. Ege Academic Review, 10(2), 503–523.

- Andersen, S., Harrison, G. W., Lau, M. I., & Rutstrom, E. E. (2008). Lost in state space: Are preferences stable? International Economic Review, 49(3), 1091–1112. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2354.2008.00507.x

- Bartke, S., & Schwarze, R. (2008). Risk-averse by nation or by religion? Some insights on the determinants of individual risk attitudes. The German Socio-Economic Panel Study (SOEP) papers on Multidisciplinary Panel Data Research, 131, DIW, Berlin. ISSN: 1864-6689.

- Becker, G. S. (1974). A theory of marriage. In T. W. Schultz (Ed.), The economics of the family: Marriage, children, and human capital (pp. 299–344). Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Becker, G. S., Landes, E. M., & Michael, R. T. (1977). An economic analysis of marital instability. Journal of Political Economy, 85, 1141–1188. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/260631

- Bellante, D., & Saba, R. (1986). Human capital and life-cycle effects on risk aversion. Journal of Financial Research, 9(1), 41–51. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6803.1986.tb00434.x

- Benjamin, D., Choi, J., & Fisher, G. (2013). Religious identity and economic behavior (NBER Working Papers No. 15925). Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Benjamin, D. J., Choi, J. J., & Strickland, A. (2010). Social identity and preferences. American Economic Review, 100(4), 1913–1928. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.4.1913

- Bhandari, A. K., & Kundu, A. (2014). Microfinance, risk-taking behaviour and rural livelihood. Springer. ISBN 978-81-322-1283-6, ISBN 978-81-322-1284-3 (eBook).

- Binswanger, H. P. (1980). Attitudes toward risk: Experimental measurement in rural India. American Journal of Agricultural Economics, 62(3), 395–407. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1240194

- Bohnet, I., Benedikt, H., & Zeckhauser, R. (2010). Trust and the reference points for trustworthiness in Gulf and Western countries. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 125(2), 811–828. doi: https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2010.125.2.811

- Charness, G., & Gneezy, U. (2012). Strong evidence for gender differences in risk-taking. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 83, 50–58. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2011.06.007

- Chinwendu, A., Chukwukere, A. O., & Remigus, M. (2012). Risk attitude and insurance: A causal analysis. American Journal of Economics, 2(3), 26–32. doi: https://doi.org/10.5923/j.economics.20120203.01

- Chuang, Y., & Schechter, L. (2015). Stability of experimental and survey measures of risk, time, and social preferences: A review and some new results. Journal of Development Economics, 117(7), 151–170. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jdeveco.2015.07.008

- Cohen, A., & Liran, E. (2007). Estimating risk preferences from deductible choice. American Economic Review, 97(3), 745–788. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.3.745

- Cox, J. C., & Harrison, G. W. (2008). Risk aversion in experiments: An introduction. In J. C. Cox & G. W. Harrison (Eds.), Risk aversion in experiments (Research in experimental economics, Volume 12) (pp. 1–7). Bingley: Emerald.

- Dadzie, S. K. N., & Acquah, H. d.-G. (2012). Attitudes toward risk and coping responses: The case of food crop farmers at Agona Duakwa in Agona East District of Ghana. International Journal of Agriculture and Forestry, 2(2), 29–37. doi: https://doi.org/10.5923/j.ijaf.20120202.06

- Diaz-Serrano, L., & O'Neill, D. (2004). The relationship between unemployment and risk-aversion. IZA discussion paper no. 1214.

- Dohmen, T., Falk, A., Huffman, D., Sunde, U., Schupp, J., & Wagner, G. G. (2011). Individual risk attitudes: Measurement, determinants and behavioral consequences. Journal of the European Economic Association, 9(3), 522–550. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774.2011.01015.x

- Drichoutis, A. C., & Vassilopoulos, A. (2016). Intertemporal stability of survey-based measures of risk and time preferences over a three-year course (MPRA Paper No. 73548). Retrieved from https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/73548/

- El Massah, S., & Al-Sayed, O. (2013). Risk aversion and Islamic finance: An experimental approach. International Journal of Information Technology and Business Management, 16(1). ISSN 2304-0777.

- Faff, R., Mulino, D., & Chai, D. (2008). On the linkage between financial risk tolerance and risk aversion. Journal of Financial Research, 31(1), 1–23. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6803.2008.00229.x

- Feinberg, R. (1977). Risk-aversion, risk and the duration of unemployment. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 59(3), 264–271. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/1925044

- Friedman, D. (1998). Monty Hall’s three doors: Construction and deconstruction of a choice anomaly. American Economic Review, 88(4), 933–946.

- Friedman, H. H. (2001). Ideal occupations: The Talmudic perspective. In Jewish law articles: Examining Halacha, Jewish issues and secular Law. Retrieved from http://www.jlaw.com/Articles/idealoccupa.html

- Gale Group. (2003). The new Catholic encyclopedia (2nd ed. Vol. 6: Fri-Hoh). Catholic University of America.

- Grable, J. E., Lytton, R. H., & O’Neill, B. (2004). Projection bias and financial risk tolerance. Journal of Behavioral Finance, 5(3), 142–147. doi: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427579jpfm0503_2

- Grable, J. E., & Roszkowski, M. J. (2007). Self-assessments of risk tolerance by women and men. Psychological Reports, 100, 795–802. doi: https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.100.3.795-802

- Greenfield, E. A., & Marks, N. E. (2007). Religious social identity as an explanatory factor for associations between more frequent formal religious participation and psychological well-being. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 17(3), 245–259. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/10508610701402309

- Guiso, L., Paola, S., & Luigi, Z. (2006). Does culture affect economic outcomes? Journal of Economic Perspectives, 20(2), 23–48. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.20.2.23

- Halek, M., & Eisenhauer, J. G. (2001). Demography of risk aversion. The Journal of Risk and Insurance, 68(1), 1–24. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/2678130