Abstract

Objective: To determine overall long-term patient and graft survival rates among the recipients liver transplanted due to acute liver failure (ALF). Secondary aims included assessment of whether diagnosis, donor-recipient blood group compatibility and time-era of transplantation affected the outcome, and whether prescription-free availability of acetaminophen increased the need for liver transplantation (LTx).

Materials and Methods: A Retrospective cohort study of 78 patients who underwent LTx for ALF at Karolinska University Hospital 1984–2014. Patients were divided into two cohorts according to two 15-year periods: early cohort transplanted 1984–1999 (n = 40) and late cohort transplanted 2000–2014 (n = 38). Survival rates were established using Kaplan-Meier analyses.

Results: ALF patient survival rates for 1-year, 5-years, 10-years and 20-years were 71%, 63%, 52% and 40%, respectively. Survival for the late cohort at 1, 5 and 10 years was 82%, 76% and 71%, respectively. A high early mortality rate was noted during the first three months after transplantation when compared to LTx patients with chronic disease. Long-term survival rates were comparable between patients with ALF and chronic liver disease. Prescription-free access to acetaminophen did not increase the need for LTx. There was a strong trend towards improved survival in blood group identical donor-recipient pairs and blood group O recipients may have benefitted from this.

Conclusions: The high early mortality rate most likely reflects the critical pre-transplant condition in these patients and the urgent need to sometimes accept a marginal donor liver. Long-term survival improved significantly over time and variation in patient access to acetaminophen did not influence the rate of LTx in our region.

Introduction

Acute liver failure (ALF) is a life-threatening condition that is clinically characterized by jaundice, coagulopathy and hepatic encephalopathy (HE). The swift degradation of liver function may, not uncommonly, affect patients with no previous history of liver disease [Citation1–4]. Disseminated intravascular coagulopathy, infection and cerebral edema are common causes of death when liver function is severely impaired [Citation5,Citation6]. When conventional intensive care treatment fails, and the chance of spontaneous liver function recovery is no longer deemed plausible, liver transplantation (LTx) is the only remaining treatment option [Citation7].

In the Nordic countries, patients may be waitlisted for a highly urgent liver transplantation through the organ exchange organization Scandiatransplant. This highly urgent listing gives the transplantation center unconditional priority to any blood-group compatible liver graft within Scandiatransplant for 72 hours from the time of listing [Citation8]. Only patients with acute liver failure without previously known liver disease and patients with a primary nonfunctioning liver within 14 days after transplantation may be listed for this indication. In recent years about 160–180 patients have undergone liver transplantation each year in Sweden, of whom about 10% were diagnosed with ALF of various etiologies [Citation9]. The mean LTx rate in Sweden was (96.1 ± 48.4) per year during the study period.

It has previously been noted that there is a difference in waiting time depending on ABO blood group [Citation9]. Although patients with blood group A undergo LTx to a greater extent than patients with blood group O (across all indications for LTx), and patients with blood group O are waitlisted the longest, the ABO group does not seem to impact outcome [Citation9]. It is unknown whether this affects ALF patients.

Acetaminophen is the most common cause for ALF, accounting for 42% of cases [Citation10]. Other idiosyncratic drug reactions and toxins may also cause liver failure and account for about 15% of ALF cases in Sweden [Citation10]. Viral hepatitis, death cap mushroom intoxication, HELLP (Hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, low platelets-count), acute Mb Wilson and Budd-Chiari syndrome are examples of other less common causes [Citation5,Citation6,Citation10–12]. The King’s College Hospital Criteria (based on serum INR, bilirubin, creatinine, pH and the presence of HE) for ALF has a high negative predictive value [Citation13] and is used together with clinical experience when hepatologists and transplant surgeons assess whether a patient with ALF should be accepted on the LTx waitlist or not.

In 2009, the Swedish Medical Products Agency (MPA) authorized certain over-the-counter drugs, including acetaminophen, for sale outside of pharmacies [Citation14]. Only a few years later, in 2013, the Swedish Poisons Information Centre reported that there had been a surge in calls regarding acetaminophen intoxication [Citation15], most likely linked to the increased availability of acetaminophen at that time [Citation14]. For this reason, the MPA decided to forbid the sale of acetaminophen in tablet form outside the pharmacies from November 2015 [Citation16]. However, it is not known if liver transplantation rates due to acetaminophen-induced ALF have increased during the same period.

This study is based on a 30-year, single-center experience and serves as an updated appraisal of LTx as the treatment of choice for patients with ALF, and of the long-term patient and graft survival for the patient group.

Materials and methods

Study design

All liver transplantations performed at Karolinska University Hospital with the indication ALF between 1 January 1984 to 31 December 2014 were included in this retrospective database cohort study (n = 78). The recipients were subsequently divided into two cohorts according to two 15-year time periods: early cohort transplanted 1984–1999 (n = 40), and late cohort transplanted 2000–2014 (n = 38). The Regional Ethical Review Board in Stockholm, Sweden, approved the study (dnr: 2017/267-31/4).

Data collection

Recipient and donor pre-, peri- and post-operative demographics were collected from the Karolinska electronic registry (Ekvator) and archived hard copy medical records, and included: age, sex, clinical examination results, past medical history, chemistry, viral serologies, date of transplantation, deceased date, operation technique (whole liver, reduced, split or in situ split), cold ischemia time, blood group compatibility, vascular complications, graft rejection, graft function, and overall survival. Waitlisted dates were obtained from the Scandiatransplant registry (Aarhus, Denmark, www.scandiatransplant.org).

Statistical analysis

ALF patient and graft survival outcomes were assessed with Kaplan-Meier estimate, first, for all included patients, then individually for the subdivided cohorts. These estimates were compared with patients who underwent liver transplantation at our center for other indications (tumors and chronic liver diseases, respectively) during the same period. Mantel-Haenszel test for equality of survival curves was performed to determine significant differences. Descriptive parameters were assessed using Mann-Whitney U test, Fischer’s exact test and Pearson’s chi-square test, and assumed equal distribution between both cohorts. Besides the Kaplan-Meier curves presented, we have also performed: i) a univariate analysis using the Cox proportional hazards regression for patient survival including transplantation period (−1999 and 2000+) as a fixed factor in the model and ii) a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression including transplantation period, recipient age (<25, 26–50, >50 year), blood group compatibility, gender as fixed factors into the model. In the multiple modeling data was first analyzed using a stepwise forward regression model and second a model including all covariates in the same model. A hazard ratio, HR, =1 corresponds to no difference between transplantation periods. An HR >1 is in a benefit for the 2000 + period (worse survival for the reference group of -1999). Calculations were performed using MEDLOG release 2015-1 (Medlog Systems, Crystal Bay, NV, USA), GraphPad Prism 6 for OS X (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego, CA, USA) and Microsoft Excel for Mac 2011 version 14.2.4 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A p-value <.05 was considered significant. Data are expressed as average ± standard deviation (SD) throughout the manuscript unless stated otherwise.

Results

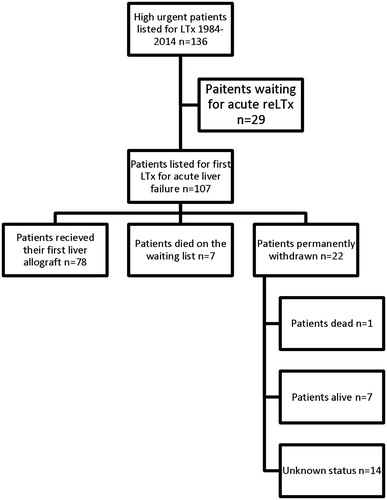

According to Scandiatransplant, 136 patients were waitlisted for highly urgent liver transplantation at Karolinska University Hospital, due to either ALF (n = 107) or the need for early re-transplantation (n = 29), between January 1984 and December 2014. An overview of the relationship between waitlisted patients and actual transplanted patients (recipients) is shown in .

Figure 1. Overview of acute liver failure patients waitlisted through Scandiatransplant and status one year after listing. ALF: acute liver failure; LTx: liver transplantation; reLTx: re-transplantation of liver.

During the 30-year period, 1984–2014, a total of 78 patients (58% female) received a first liver allograft for the indication ALF. The mean age was 34 years (±19.3). A total of 19 patients (24.4%) were pediatric (<18 years old) with a median age of 5 years. There was no significant difference between the early and late cohort with regards to age, gender or etiology of ALF. Patient baseline characteristics are presented in the Supplemental online material. In 42.3% of the cases, no etiology to ALF could be determined. The most common determined etiology to ALF was acetaminophen (n = 11, 14.1%), all of whom were women. Disulfiram was the second most common drug (n = 4, 5.1%), while no other drug was found to have caused more than one case of ALF.

During the period that acetaminophen was widely available prescription-free outside of pharmacies in Sweden until the decision to limit the availability (2009–2013), a total of 14 LTx were performed for the indication ALF, of which three were acetaminophen-induced. Notably, in 2008, the year before acetaminophen was allowed to be sold outside of pharmacies there were three LTx for acetaminophen-induced ALF. Thus, there was no significant (p = .40) increase in LTx for acetaminophen-induced ALF 2009–2013.

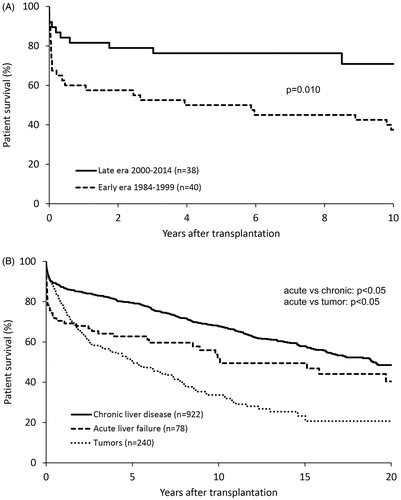

The overall patient survival rates for all transplanted ALF patients during the study period were 71% at 1 year, 63% at 5 years, 52% at 10 years and 40% at 20 years. Corresponding 1-year, 5-year and 10-year patient survival rates for the late cohort were 82%, 76% and 71%, respectively. The graft survival rates for all grafts during the study period were 67% at 1 year, 59% at 5 years, 48% at 10 years and 29% at 20 years. Corresponding 1-year, 5-year and 10-year graft survival rates for the late cohort were 79%, 71%, and 66%, respectively. The difference between patient and graft survival rates reflects the requirement for re-transplantation among those patients with graft failure. There was a significant improvement in the late cohort patient survival rate compared to the early cohort (). The univariate Cox proportional hazard regression model reveals that the hazard ratio (HR) was 2.36, which corresponds to a 2.36 times worse survival for the transplantation period up to 1999 compared to subjects in the period from 2000 and forward (p = .018). In the multivariate stepwise forward regression, the model stopped after including transplantation period and recipient age into the model. The estimate of the HR between transplantation periods was somewhat larger than in the univariate model, HR = 2.72, (p = .017). In the multivariate regression including transplantation period, recipient age, blood group compatibility and gender into the model, the estimate for the difference between the transplantation period was HR = 2.64 (p = .008). The number of re-transplantations was 16 (20%), 13 of which were during the early period, and constitutes a higher re-transplant rate than seen in the chronic liver disease.

Figure 2. Survival rates after liver transplantation for acute liver failure. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival rates subdivided according to the two 15-year time periods. (B) Patient Kaplan–Meier estimates of survival rates following liver transplantation (year 1984–2014) subdivided according to liver disease category.

When comparing patients transplanted for ALF with all other indications, there was a significant difference in patient survival rates. The 1-year, 5-year, 10-year and 20-year patient survival rates for patients with chronic liver diseases were 87%, 79%, 68% and 49%, respectively. Corresponding survival rates for recipients with tumors were 76%, 51%, 34% and 21%. The most dramatic drop in recipient survival was seen during the first three months in both ALF cohorts, after which they plateaued with a slow and gradual decrease over time. Survival rates subdivided according to liver disease category are shown in .

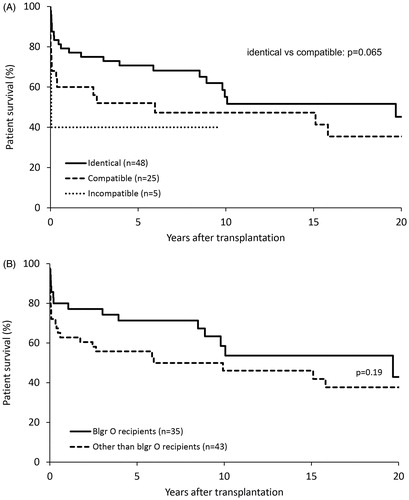

The most common blood group for both recipient and donor was blood group O (n = 35, 44.9% and n = 52, 66.7%) followed by blood group A (n = 32, 41% and n = 21, 26.9%) indicating that several O donor livers were used by other blood group recipients. The majority of patients (n = 73, 94%) received a liver graft from a donor with either an identical or compatible blood group. Blood groups of recipients, donors and recipient-donor blood group compatibility are summarized in .

Table 1. Blood group compatibility and baseline characteristics.

Time on the waiting list before transplantation was dependent on the patient’s blood group. For recipients with blood group A, the average waiting time for any compatible or identical graft was 3.14 days (±6.45). For recipients with blood group O, the average waiting time was 2.75 days (±2.1), of which 25% (n = 7) waited more than three days. There was no significant difference between the early and late cohort with regard to blood group distribution (p = .75) or blood group compatibility (p = .22). There was a trend of better outcomes among blood group identical transplants (p = .065), as well as for blood group O recipients (p = .19) ().

Figure 3. Impact of recipient-donor blood group compatibility on patient survival. (A) Kaplan-Meier survival estimates subdivided according to blood group compatibility between donor and recipient. (B) Survival estimates for recipients with blood group O compared to recipients with other blood groups. Acute liver failure patients depicted.

Discussion

The mortality rate was relatively high during the first three months post-transplant in both the early and late patient cohorts. This was perhaps not unexpected, possibly reflecting the peri-operative and early post-operative complications known for ALF patients [Citation17,Citation18]. Patients transplanted during the late era did significantly better than patients from the early era (). Results from the univariate and multivariate models of survival showed that the estimates for the difference between transplantation period was in favor of the latter period of 2000 and forward. The estimate of the HR was slightly larger after adjusting for other factors. This reflects no adverse negative impact on the significant findings of the model variables (age, gender, blood group). The early survival rate after LTx for ALF is thus inferior to that with other LTx indications but, encouragingly, improves in relation to other indications over time. This may in part be related to the younger age of patients with ALF compared to other indications (). Potential factors that have improved over time, and constitute either distinct or continuous separators between the two studied cohorts, include: availability of liver dialysis, increased use of early acetylcysteine [Citation19] treatment, shortened mean cold ischemia time, improved critical care, more efficient and wider variety of immunosuppression regimens [Citation20,Citation21], and the use in part of non-heart-beating donors during the early era.

Based on this single-center experience, the difficulty of choosing the most suitable recipient to be waitlisted and the timing thereof still remains, and a similar dilemma is found in multiple reports on ALF [Citation7,Citation8,Citation22]. In a study similar to ours, Brandsaeter and colleagues [Citation22] included 229 patients over 12 years, without identifying any specific risk factors that enabled outcome prediction, and with comparable patient survival rates.

The 2012 Nordic Liver Transplant Registry annual report [Citation23] showed results similar to the present study: survival rates for patients transplanted for ALF between 2003–2012 were comparable at 1 year and 5 years [Citation18,Citation23]. In general, ALF patients excluded, patients with blood group A have a shorter median waitlist time compared to patients with blood type O, which was not seen in our study of ALF patients in which waitlist time was similar between the two blood groups. However, Brandsaeter et al [Citation22] reported a difference in waitlist time. In their study, for all highly urgent recipients with blood group A, the mean waiting time was 3.8 days and 24% of those patients waited >3 days. For blood type O the mean waiting time was 6.6 days and 36% waited >3 days. These waitlist times are considerably longer than those in the present study. The Brandsaeter study contained 61 listed Stockholm patients between 1990–2001. This current study adds the experience from an additional 46 patients through 2002–2014, and a much-extended follow-up period on the first 61 patients (n = 107 in total).

Although acetaminophen was authorized to be sold more liberally in 2009 outside the pharmacies, and likely led to the surge of acetaminophen intoxication reports in Sweden [Citation14,Citation15,Citation24], we conclude that this was not linked to increased LTx rates at our center during five years of follow-up. We are humble to the fact that the number of patients with acetaminophen-induced ALF (n = 11) is quite small in our study, and thus, this finding has yet to be confirmed on a nationwide level.

Most types of acute and chronic end-stage liver disease can potentially be considered for liver transplantation, and a variety of predictive scores and selection criteria are used at different centers. It is important to continuously evaluate the outcome within these different groups, especially among high-risk ALF patients, to appraise the best possible treatment regimens. Our data support that LTx is indeed a durable procedure for ALF, which is a patient category that is otherwise associated with high mortality rates.

In conclusion, recipients of livers due to ALF demonstrated a higher mortality rate in the first three months compared to other indications. There was a significant improvement in ALF patient survival during the latter 15-year period. Transplantation, where recipient and donor have identical blood groups, seems favorable in terms of overall survival, especially in the most recent 15-year period. Finally, variations in patient access to acetaminophen did not influence the rate of LTx in our region.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (16.6 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank Jan Kowalski (JK Biostatistics AB) for assistance with statistical analyses.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Shalimar, Acharya SK. Management in acute liver failure. J Clin Exp Hepatol. 2015;5:S104–S115.

- Lee WM, Squires RH Jr, Nyberg SL, et al. Acute liver failure: summary of a workshop. Hepatology. 2008;47:1401–1415.

- Lee WM, Larson AM, Stravitz RT. AASLD position paper: the management of acute liver failure [Internet]; 2011. Available from: https://www.aasld.org/sites/default/files/guideline_documents/alfenhanced.pdf.

- Lee WM, Stravitz RT, Larson AM. Introduction to the revised American Association for the study of liver diseases position paper on acute liver failure 2011. Hepatology. 2012;55:965–967.

- Ostapowicz G, Fontana RJ, Schioødt FV, et al. Results of a prospective study of acute liver failure at 17 tertiary care centers in the United States. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137:947–954.

- Lee WM. Acute liver failure. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1862–1872.

- O’Grady J. Liver transplantation for acute liver failure. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2012;26:27–33.

- Bjoro K, Kirkegaard P, Ericzon BG, et al. Is a 3-day limit for highly urgent liver transplantation for fulminant hepatic failure appropriate, and is the diagnosis in some cases incorrect? Transplant Proc. 2001;33:2511–2513.

- Melum E. The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR) Annual report 2015 [Internet]; 2016 Available from: http://www.scandiatransplant.org/members/nltr/TheNordicLiverTransplantRegistryANNUALREPORT2015.pdf/at_download/file

- Wei G, Bergquist A, Broome U, et al. Acute liver failure in Sweden: etiology and outcome. J Intern Med. 2007;262:393–401.

- Gill RQ, Sterling RK. Acute liver failure. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33:191–198.

- Lee WM. Etiologies of acute liver failure. Semin Liver Dis. 2008;28:142–152.

- O'Grady JG, Alexander GJM, Hayllar KM, et al. Early indicators of prognosis in fulminant hepatic failure. Gastroenterology 1989;97:439–445.

- Gedeborg R. Paracetamol poisoning. Medical Products Agency; 2014. Available from: https://lakemedelsverket.se/Alla-nyheter/NYHETER-2014/Forsaljning-av-paracetamol-i-tablettform-tillats-endast-pa-apotek/

- Höjer J, Karlson-Stiber C, Landgren A, et al. [Paracetamol poisoning increasingly common. Poisons Information Centre sound the alarm - high time for countermeasures] Stockholm: Läkartidningen; 2013;10:CFW3. (Swedish).

- [Sale of paracetamol in tablets in retail stores cease November 1] [Internet]; 2015. (Swedish). Available from: https://lakemedelsverket.se/Alla-nyheter/NYHETER-2015/Forsaljning-av-paracetamol-i-tablettform-i-detaljhandeln-upphor-1-november/

- Bernal W, Lee WM, Wendon J, et al. Acute liver failure: a curable disease by 2024? J Hepatol. 2015;62:S112–S120.

- Fosby B, Melum E, Bjoro K, et al. Liver transplantation in the Nordic countries - An intention to treat and post-transplant analysis from The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry 1982–2013. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2015;50:797–808.

- Keays R, Harrison PM, Wendon JA, et al. Intravenous acetylcysteine in paracetamol induced fulminant hepatic failure: a prospective controlled trial. Bmj. 1991;303:1026–1029.

- Feng S, Goodrich NP, Bragg-Gresham JL, et al. Characteristics associated with liver graft failure: the concept of a donor risk index. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:783–790.

- Aberg F, Gissler M, Karlsen TH, et al. Differences in long-term survival among liver transplant recipients and the general population: a population-based Nordic study. Hepatology 2015;61:668–677.

- Brandsaeter B, Hockerstedt K, Friman S, et al. Fulminant hepatic failure: outcome after listing for highly urgent liver transplantation - 12 years experience in the nordic countries. Liver Transpl. 2002;8:1055–1062.

- Karlsen TH. The Nordic Liver Transplant Registry (NLTR) Annual report 2012 [Internet]; 2013. Available from: http://www.scandiatransplant.org/members/nltr/ANNUAL_REPORT_2012_NLTR.pdf/at_download/file

- Hojer J, Karlsson-Stiber C, Landgren A, et al. Paracetamol poisoning becoming more common [Internet]; 2015. (Swedish). Available from: http://www.lakartidningen.se/Klinik-och-vetenskap/Rapport/2013/10/Paracetamolforgiftningar-allt-vanligare/