Abstract

Background and aims: Quality of care is important in lifelong illnesses such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). Valid, reliable and short questionnaires to measure quality of care among persons with IBD are needed. The aim of this study was to develop a patient-derived questionnaire measuring quality of care in persons with IBD.

Methods and results: The development of the questionnaire The Quality of Care -Questionnaire (QoC-Q) was based on a literature review of studies measuring quality of care, and the results of two qualitative studies aiming to identify the knowledge need and perception of health care among persons with IBD. Further development and evaluation was done by focus groups, individual testing and cognitive interviews with persons with IBD, as well as evaluation by a group of professionals. After the development, the questionnaire was tested for validity and test–retest reliability in 294 persons with IBD.

Conclusions: The QoC-Q is showing promising validity and reliability for measuring the subjective perception of quality of care. Further testing in clinical practice is suggested to assess if the QoC-Q can be used to evaluate care and areas of improvement in health care for persons living with IBD.

Introduction

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) comprises several diseases, the most common ones being ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. IBD often has an early onset in life and intermittent periods of flare-ups [Citation1]. For the person living with IBD, the disease is associated with bothersome and sometimes debilitating symptoms causing a decrease in health-related quality of life, including effects on family and work [Citation2]. Lifelong contact with health care services is often needed when living with a chronic condition such as IBD [Citation1,Citation2]. Frequent contacts with health care are crucial to obtain and maintain remission and prevent complications to disease and treatment. For the health care organization, IBD is associated with high costs and demanding resource utilization [Citation3].

The quality of health care is important both for the person living with IBD and for the health care organization [Citation4,Citation5]. Quality of care can be assessed in numerous ways, such as measuring the structure, the process and the outcomes of health care [Citation6,Citation7]. Structural measures are characteristics of the setting in which care is delivered. Process measures indicate the steps taken by health care providers in the care of an individual person. Outcome measures describe the results of the care given [Citation6]. One aspect of outcome of quality of care is the patients’ experiences of the health care they receive. When evaluating quality of health care, there are sometimes discrepancies between the perception of the person receiving care and the perception of health care professionals [Citation8]. The view of the person living with the disease is therefore important in order to achieve quality assessments from all perspectives, and to be able to develop a person-centered health care. In order to evaluate the patients’ perspective on health care, patient-reported experience measures (PREM) are required. However, despite an increasing awareness of the potential value, and in contrast to some other chronic diseases such as cancer and nephrology [Citation9,Citation10], patients’ experiences of health care are currently not routinely assessed among patients with IBD. In fact, the use of PREMs to evaluate the quality of care remains a challenge for health care in IBD.

Based on the ‘structure-process-outcome’ approach mentioned above, the Netherlands Institute for Health Services Research (NIVEL) has developed a series of questionnaires that measure quality of care from a patient perspective (QUOTE) [Citation11]. As far as we know, it is the only disease specific questionnaire measuring patient-reported quality of care in patients with IBD. The instrument comprises two types of items; Importance (I), i.e., the importance that the patient contributes to various care aspects (23 items), and Performance (P), i.e. the patient´s experience of each aspect of care (23 items). Importance (I) and performance (P) are then combined to a Quality Impact value [Citation11,Citation12]. The QOUTE-IBD was originally developed for use in clinical practice. However, none of the previous validation studies using QOUTE-IBD have reported on user feasibility [Citation11,Citation13]. One problem with using the QOUTE-IBD in clinical practice is that it is rather lengthy and unpractical.

In 2013, a workshop was organized in Oxford by the IBD2020 group, aiming to improve future health care in IBD. The participants concluded that studies focusing on quality of care and IBD are limited and that more research is needed. They also highlighted the importance of patient participation when formulating research questions [Citation14]. The respondent’s perspective is important when determining the use of appropriate questionnaires [Citation15], meaning that the questionnaire should contain questions that are important to the respondents. Ideally, survey questions should be designed to make every part of the cognitive response process as easy as possible for the respondent [Citation16]. The questionnaire should also be relevant to the respondents and they should be able to answer it without too much effort in a reasonable time [Citation17,Citation18]. As a short, respondent-focused questionnaire was lacking, there was a need to develop a questionnaire evaluating quality of care from the perspective of persons with IBD. Therefore, we initiated the current study.

Aim

The aim of this study was to develop a patient-derived questionnaire measuring quality of care among persons with IBD.

Methods and results

Questionnaire development and evaluation

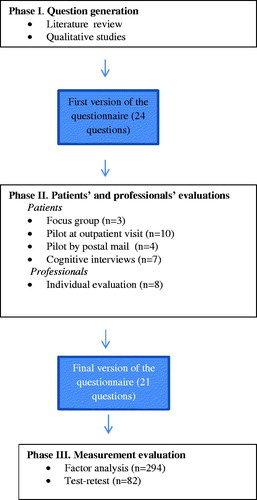

The development and evaluation process was performed in three phases ().

Phase I—question generation

A literature review of studies measuring quality of care in IBD was performed in order to identify aspects of importance related to quality of care [Citation19] (). Furthermore, two qualitative studies were performed aiming to identify the knowledge need and perception of health care among persons living with IBD [Citation8,Citation20]. These studies showed that trust and respect, shared decision-making, information, continuity of care, access to care and satisfaction with health care as a whole were the most important perceptions of health care among persons living with the disease [Citation8] (). The results from the qualitative studies [Citation8,Citation20] generated dimensions for perceptions of HC. The different dimensions varied in how the patient perceived how important they were. The number of questions in the questionnaire for each dimension reflects the patient's perception of how important they were, subsequently forming the basis for the QoC-Q (). The research group met several times to discuss the content, layout, and response options. The first version of the questionnaire consisted of 24 questions, six in the dimension trust and respect, five in access to care, four in decision-making, three in continuity of care, three in information, two in competence, and one in satisfaction with the care as a whole (). For all questions in the questionnaire (except the one on overall satisfaction), the respondent was first asked how important the question was to them and then how they experienced the performance (). The response options to the performance questions in the first version were ‘totally agree’, ‘agree to a great extent’, ‘agree to some extent’ and ‘do not agree’. The response options to the importance questions in the first version were ‘extremely important’, “important”, ‘fairly important’ and ‘not important’.

Figure 2. Dimensions important for quality care from the perspective of persons living with IBD. Number of questions in the final version of the QoC-Q in each dimension. Number of questions in the first version of the questionnaire in brackets.

Table 1. First version of the QoCQ.

Phase II—patients’ and professionals’ evaluations

The first version of the quality of care questionnaire (QoC-Q), consisting of 24 questions, was evaluated in phase II by patients with IBD and health care professionals (). The purpose of phase II was to test the question's function and measurement capabilities through several different steps and methods such as cognitive interviews, focus group interviews and expert review.

The patients were recruited in the various phases of the evaluation to be representative to the IBD population at large—i.e. patients with mild, moderate and active disease, extensive versus limited disease, complicating disease versus uncomplicated and a mix with an equal distribution between the diagnosis ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease.

Step I, phase II

In the first step, the questionnaire was tested by a focus group interview held by the first author. The aim of the focus group was to ensure face validity. The focus group consisted of three persons with IBD, two women and one man of different ages and with different experiences of living with the disease. The result of the focus group was that the questions covered the area of quality of care as a whole. They thought it was unnecessary to ask both for importance and performance on each questions. They thought the timeframe of thinking back on the last year was too long period of time, they thought 6 months would be appropriate. Further on they thought that it would be beneficial to combine the questionnaire with a questionnaire measuring symptom burden and disease activity.

Step II, phase I

Thereafter, the questionnaire was pilot tested by 10 patients diagnosed with IBD who had a scheduled visit at the gastroenterology department during March 2015. The aim of the outpatient pilot was to evaluate the patients’ experience of the relevance of the questions and the feasibility to answer the questions. The patients were asked to complete the questionnaire directly after their visit at the clinic and had an opportunity to ask questions or make comments, both orally and in writing, after they had answered the questionnaire. After completing the questionnaire, they were asked whether they experienced any problems with the wording and whether they found any question difficult to respond to. They were also asked if they thought that any question was irrelevant or if any important aspects of quality of care were missing. Thereafter, the questionnaire was pilot tested by mailing it to four other persons with IBD, who were asked to answer and return it to the first author. The aim of the mail pilot was to evaluate the function of the questionnaire when respondents answered it at home, without any help or instructions from health care personnel. In the questionnaire, they had an opportunity to write comments about the relevance of the questions and whether they found it difficult to answer the questionnaire.

All participants, in the pilot test, felt that the questions were easy to understand and that the questions covered the area of quality of IBD health care. However, they also thought that it was unnecessary to ask about importance for each question as they were all important for the perception of quality of care. The only exceptions were the patients disagreed on the relevance of having questions both on importance and performance were the questions on decision-making and continuity of care. Some patients commented that they did not consider themselves competent to make decisions, but would rather trust the clinical experts, and that it was not so important to meet the same health care personnel when they were just in for a routine checkup. It was therefore decided to only ask about importance for these two questions. Some other changes were made, such as reformulating the statements to questions and changing the layout from a grid format to a single question format.

Step III, phase II

Step III and the last part of the patient evaluation in phase II was cognitive interviews (n = 7) performed by the fifth author (MW) and the first author, in order to evaluate the questionnaire’s cognitive function, respondent-friendliness and ensure face validity. The aim was to find out if the questionnaire was easy to understand and answer. Four women and three men with IBD participated, and the interviews were performed according to the method ‘think aloud’, followed by retrospective probes such as ‘Can you tell me more about…’, in order to clarify or explore responses during the interviews [Citation21]. The first two interviews were held in a care situation, which was bothersome for the patients. Therefore, the following five interviews were performed in a more neutral situation in a conference room. The interviews lasted between thirty and sixty minutes. Some difficulties understanding concepts emerged and a few questions were reformulated. Examples of what was said in the cognitive interviews are expressed below.

For example, a definition of a care plan was added, based on comments such as:

”I don’t know- This word is really difficult [individual care plan]. It makes me think of care plans like the ones in elderly care where I work. For instance, we make a plan with a doctor for residents whose condition deteriorates to see if they should stay [scores “don’t know” and skips the follow-up question]. Care plan is a hard word that is used for all sorts, but I can’t think of anything better right now.” (woman born in 1952).

”You might not understand what is intended. Maybe it would be better if it said ’follow-up’ or ’plan’. It’s important that you know what it is (woman born 1991)

A question regarding the possibility to have an acute appointment was changed into an opportunity for the patients to contact the clinic when their disease worsened. The word ‘acute’ was perceived very differently by the patients. For some it meant having an appointment the same day, while for others it meant having an appointment within three days. The heading about perception of health care in general was changed to perception of care at the gastroenterology department. One question about easy telephone access to the clinic was clarified so that it became obvious that it meant access to the nurse’s counseling telephone line, as the persons with IBD expressed that this was of the greatest importance. The participants in the cognitive interviews also provided positive feedback on the questions, such as the open-ended question at the end of the questionnaire. Here, they were able to express themselves freely about anything that they thought was missing in the questionnaire or matters they felt should be explained more thoroughly. They also appreciated being able to express that continuity was not as important in all situations, which supported the decision to keep the importance questions regarding continuity of care (examples of what was said during the cognitive interviews are shown in the quotations below).

It is nice to meet the same person, but the years pass and physicians come and go. I wouldn’t expect to meet the same one each time. I have had different [doctors] at each visit. (Man born 1932)

I know it is difficult to get the same one, but I wish I could. You don’t know if they have all the information, but at the same time, I’m not that ill – (Woman born 1952).

Step IV, phase II

The last part of phase II was an evaluation by a group of professionals (expert group) (n = 8). The aim of allowing an independent expert group to assess the relevance of each question in the questionnaire was to ensure content validity. The questionnaire was sent to health care professionals who were familiar with IBD or questionnaire development; three gastroenterologists, two nurses specialized in IBD, one statistician and two people with experience in questionnaire construction. The questionnaire was sent by mail and the health care professionals were asked to return their comments and evaluation to the first author. In the questionnaire, they could write comments about the relevance of the questions. The comments mostly dealt with the layout and the way the questions were asked. Therefore, changes were made in, for example, the color and size of the headings. The boxes where the respondents are to note their response were also changed from circles to squares.

All steps in phase II resulted in a new draft consisting of five questions about trust and respect, four questions about decision-making, three about information, two about continuity, one question about access to care, including six subqueries, and finally one question about satisfaction with health care as a whole. In total, there were 21 questions (appendix). Each question had four response options, except the question on overall satisfaction, where the response options ranged between 1 and 10 (Appendix). All questions on importance except the ones on decision making and continuity of care were excluded.

Phase III—measurement evaluation

Phase III aimed to test the function of the questionnaire in a real setting and to test reliability. Six hundred people with a confirmed diagnosis of IBD, who had received care at the IBD clinic at a university hospital in south-east Sweden between September 2014 and September 2015 were invited to participate in the study (). The sample size was based on an expected response rate of 50% and the possibility to measure differences in health care experience between subgroups, such as gender, age and diagnoses (Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis).

Table 2. Demographic characteristics of the study population and non-responders in phase III, the evaluation of the Quality of Care questionnaire in IBD (QoCQ).

Table 3. Test–retest for the QoCQ.

The participants received information about the study through an information letter. The questionnaire QoC-Q (appendix), the QOUTE-IBD, and a pre-paid envelope were sent by post mail. The recipients were asked to answer the questionnaires and return them if they consented to participate in the study. They received information that they could withdraw from the study at any given time and that their participation vas confidential. One reminder was sent after four weeks. In all, 294 patients (49%) returned the questionnaires. Demographics for the respondents and non-responders are presented in . Medical records of all participants were checked for diagnosis and disease duration. To determine test–retest reliability between the two measurements, all participants were asked if they would consider answering the questionnaires once more. Out of the 294 respondents, 141 replied that they were willing to do so and they were therefore sent the second questionnaire one week later. For the assessment of test–retest reliability, a time-interval of 2–14 days is often considered long enough to prevent recall bias and too short for relevant change to occur in chronic disease [Citation22]. Test–retest reliability was computed as the intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) between the two sets of questionnaires. An ICC of 0.80 was considered the required minimum for good reliability [Citation22]. In total, 83 patients returned the second questionnaire within a 2-week span.

Acceptability

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the distribution of responses to questions and patterns of missing data. SPSS Statistics 22.0 was used for statistic calculation. The question non-response of the QoC-IBD was between 0.7 and 3.9%. The question with the highest non-response rate was number nine, which deals with individual care need. In the QUOTE-IBD, the question non- response was between 1.0 and 6.5% for the importance questions and 27.6–40.5% for the performance questions. The questions with the highest non- response rates were number four on performance ‘should allow the patients to have input in decisions regarding treatment received’, and question 10 on performance ‘In case of acute problems a doctor should be available within 24 hours’.

Reliability

Test–retest reliability for the QoC-Q was analyzed with Spearman’s correlation and is shown in . Test–retest for the QOUTE-IBD importance questions is shown in and the performance questions in . Internal consistency reliability tested with Cronbach’s α for the QoC-Q was α = 0.811. For QoC-Q, ICC was 0.80. Cronbach’s α for the importance questions in the QUOTE-IBD was α = 0.908.

Table 4. Test–retest for the QOUTE-IBD importance questions.

Table 5. Test–retest of the QOUTE-IBD Performance questions.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was obtained by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Linköping, Sweden (Dnr 2013/426-32). The study was carried out in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (WMA, 2013).

Discussion

In this study, we developed the QoC-Q aiming to measure quality of care among persons living with IBD. To ensure high trustworthiness, efforts were made to involve persons with IBD in all phases of the development process. The items in the QoC-Q emerged from the literature review and the results from two qualitative interview studies [Citation8,Citation20], assuring the persons’ living with IBD perspective of quality of care.

The initial aim was to develop an IBD specific questionnaire for assessment of the quality of care. Although no IBD specific questions from the qualitative studies [Citation8,Citation20] emerged. The main findings from the qualitative study exploring the patients’ perceptions of health care [Citation8] showed that ‘professional attitudes of HC staff’ and ‘structure of the HC organization’ were the most important aspects of HC. ‘Professional attitudes of HC staff’ meant being encountered with respect and mutual trust, receiving information at the right time, shared decision-making, competence and communication, while the ‘structure of the HC organization’ involved access to care, accommodation, continuity of care and the pros and cons of specialized care. These findings are consisting with areas of importance for other chronic diseases and quality of care as well [Citation23].

The wording of each question was adapted in order to use expressions as close to the participants’ statements in the focus groups and cognitive interviews. This development and evaluation procedure generated a questionnaire that shows promising validity and reliability. Content and face validity was achieved by assuring that the questions were perceived as adequate by persons with IBD and health care professionals. The questionnaire was perceived as easy to understand and answer, and can be considered as feasible. Including persons with IBD in evaluations is something that has been neglected in the past when developing questionnaires measuring quality of care in IBD (e.g. the Quote-IBD) [Citation11,Citation24]. This is an important step in the direction of evaluating health care in a person-centered way, as health care organizations strive for a person-centered approach in every part of health care [Citation25].

One important aspect when using questionnaires to measure patient- reported experience is the burden posed on the patients when asking them to answer questions that are not relevant [Citation26]. The QOUTE-IBD, which combines the assessment of Importance and Performance for all the 23 items, poses an extra burden on the respondent [Citation11]. Our results conclude that all questions (except two) in the QOUTE were given the highest rating of importance by all patients in the pilot study. This is not surprising as the questions were included in the questionnaire because they are known to be of importance to patients. It should therefore not be necessary to repeat the importance questions for each aspect in the questionnaire. This was further strengthened by the focus group interviews which showed that the respondents found it unnecessary to ask for importance aspects that are obviously of great importance. However, in matters where patients find an aspect to be different, the question on importance plays an important role. The questions about importance were therefore excluded, except for the two questions on decision-making and continuity of care. This diversity on the importance of decision-making is supported in the literature [Citation27–29]. Keatinge et al. (2002), Caress et al. (2002) and Efraimsson et al. (2004) [Citation27–29] have identified several obstacles for shared decision-making, including health personnel’s communication skills and lack of time. Younger patients have been shown to prefer more collaboration with physicians in decision-making, whereas older patients wanted the physician to make decisions independently of the patient [Citation30,Citation31]. In addition, Henderson and Shum [Citation31] have shown that patients wish for more participation in the decision-making process if the medical condition is assessed as less severe. Patients with a high-level education preferred a more active participatory role in medical decision-making [Citation30].

Cognitive interviews can reveal how survey questions are interpreted and how responses are delivered from a respondent’s perspective [Citation32]. In this study, the interviews revealed that there were problems understanding the concept of a care plan and a definition was therefore added in the questionnaire. As a result of the cognitive interviews, question relevance and clarity was also improved, thus increasing the validity of the questionnaire [Citation21]. This process can also help detect potential sources of error in survey questions [Citation32], such as the question on the possibility to have an acute appointment, which was changed into opportunity to come to the clinic when the patients themselves felt that their disease worsened. The question about having enough access to the clinic by telephone was too unspecific and was therefore clarified to having access to the nurse’s counseling telephone line. Receiving such feedback allows the researcher to gain an insight into problems that may not have been anticipated prior to the distribution of the questionnaire. It can then be ensured that the majority of the respondents will interpret the questions in a similar way [Citation21,Citation32]. In this study, seven cognitive interviews were performed, leading to the development of an effective and comprehensive questionnaire. Recommended numbers of interviews are usually 5–7 [Citation21].

The question non-response rate in the QoC-Q was low, 0.7–3.9%, with the highest rate in the question about individual care need. It might be difficult to understand what individual care need means, and in future versions of the questionnaire this question might need to be defined in another way. In the QOUTE-IBD, all questions on Importance had a question non-response rate between 1 and 6.5%, although for Performance, the question non-response rate was 27–40%. This is similar to the Portuguese validation study of the QOUTE-IBD, where 92% of the patients answered all questions on Importance, but only 59% completed all the questions in the QOUTE-IBD [Citation33]. In our study, the high response rate in the QoC-Q indicates good acceptability. There are problems concerning acceptability in the QOUTE-IBD due to the low response rate in the performance questions. In our study, as well as in other studies, the reason for the high question non-response rate in the QUOTE-IBD may be due to the fact that several questions are specific to the interaction with a special group of professionals or a specific health care situation. This makes a question hard to answer if you as a patient have not experienced a specific event in the past 12 months. The low response rate in the performance questions also complicates the calculation of the quality impact of the QUOTE-IBD.

Strengths and limitations

The patients with IBD were part of the whole development and testing process of the questionnaire, which strengthens the results. The cognitive interviews are particularly important as they provide extra time for conversation and evaluation with the patients. Another strength of the study is that we made a comparison with the QUOTE-IBD, the previously only known instrument measuring quality of care in patients with IBD. A limitation in the study may be the response rate of 49% in phase III, the measurement evaluation phase. Still, response rates to surveys are declining in many countries [Citation34,Citation35], particularly among the young [Citation36]. Two reminders could have been sent instead of one, but we only had ethical approval for one reminder. The validation process may not be affected by the low response rate but if the aim had been to describe the population, generalization of the results might have been more sensitive to a low response rate. Another limitation is the fact that the questionnaire was developed and designed for a Swedish care context, where it is common to organize IBD care with IBD nurses and multidisciplinary teams. If the questionnaire is to be used in another context, cultural adaptation might be needed. We suggest further testing in clinical practice to assess if the QoC-Q can be used to evaluate care and areas of improvement in health care for persons living with IBD, as well as translation and cultural adaption to other countries carrying for persons with IBD.

Conclusions

The QoC-Q is a new, short, self-administered questionnaire with promising validity and reliability, measuring the subjective experience of quality of care in persons with IBD. It was designed in close collaboration with patients to really capture their perception of quality of care. The QoC-Q seems to be easy to use for persons with IBD, and it can enable clinicians and researchers to identify targets for improvement. As good quality of care is essential in chronic diseases, the QoC-Q could become an important tool in addition to other methods for optimizing health care for IBD patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge all persons with IBD who participated in the study, contributing colleagues, and funding from Ferring Pharmaceuticals and the County Council of Östergötland, Linköping, Sweden, that made it possible to carry out and complete the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Ghosh S, Mitchell R. Impact of inflammatory bowel disease on quality of life: results of the European Federation of Crohn's and Ulcerative Colitis Associations (EFCCA) patient survey. J Crohn's Colitis. 2007;1:10–20.

- Pihl-Lesnovska K, Hjortswang H, Ek AC, et al. Patients' perspective of factors influencing quality of life while living with Crohn disease. Gastroenterol Nurs. 2010;33:37–44.

- Kappelman MD, Rifas-Shiman SL, Porter CQ, et al. Direct health care costs of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis in US children and adults. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:1907–1913.

- Kappelman MD, Palmer L, Boyle BM, et al. Quality of care in inflammatory bowel disease: a review and discussion. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2010;16:125–133.

- Loftus EV, Jr., Schoenfeld P, Sandborn WJ. The epidemiology and natural history of Crohn's disease in population-based patient cohorts from North America: a systematic review. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:51–60.

- Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed?. JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748.

- Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. 1966. Milbank Q. 2005;83:691–729.

- Lesnovska KP, Hollman Frisman G, Hjortswang H, et al. Healthcare as perceived by persons with inflammatory bowel disease - a focus group study. J Clin Nurs. 2017;26:3677–3687.

- Breckenridge K, Bekker HL, Gibbons E, et al. How to routinely collect data on patient-reported outcome and experience measures in renal registries in Europe: an expert consensus meeting. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2015;30:1605–1614.

- Tremblay D, Roberge D, Berbiche D. Determinants of patient-reported experience of cancer services responsiveness. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:425.

- van der Eijk I, Sixma H, Smeets T, et al. Quality of health care in inflammatory bowel disease: development of a reliable questionnaire (QUOTE-IBD) and first results. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:3329–3336.

- Eijk I. Quality of health care in inflammatory bowel disease: developement of a reliable questionnaire (QUOTE-IBD) and first results. 2001;96:3329–3336.

- Pallis AG, Vlachonikolis IG, Mouzas IA. Validation of a reliable instrument (QUOTE-IBD) for assessing the quality of health care in Greek patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Digestion. 2003;68:153–160.

- Kairos F. IBD2020 Survey. Verlag and Supria; 2013.

- Dunderdale K, Thompson DR, Miles JN, et al. Quality-of-life measurement in chronic heart failure: do we take account of the patient perspective?. Eur J Heart Failure. 2005;7:572–582.

- Sudman S, Bradburn NM, Schwartz N. Thinking about answers: The application of cognitive process to survey methodology. 1st ed. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass Publisher; 1996.

- Kim MY, Dahlberg A, Hagell P. Respondent burden and patient-perceived validity of the PDQ-39. Acta Neurol Scand. 2006;113:132–137.

- Wenemark M, Hollman Frisman G, Svensson T, et al. Respondent satisfaction and respondent burden among differently motivated participants in a health-related survey. Field Methods. 2010;22:378–390.

- Polit DF, Beck CT. Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice. 9th ed. 2012.

- Lesnovska KP, Borjeson S, Hjortswang H, et al. What do patients need to know? Living with inflammatory bowel disease. J Clin Nurs. 2014;23:1718–1725.

- Collins D. Cognitive interviewing practice. London: SAGE Publications Ltd; 2014

- Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales—A practical guide to their development and use: Oxford Scholarship Online: September 2009; 2008.

- Wilde Larsson B, Larsson G. Development of a short form of the quality from the Patient's Perspective (QPP) questionnaire. J Clin Nurs. 2002;11:681–687.

- Larsson G, Larsson BW, Munck IM. Refinement of the questionnaire 'quality of care from the patient's perspective' using structural equation modelling. Scand J Caring Sci. 1998;12:111–118.

- Ekman I, Wolf A, Olsson LE, et al. Effects of person-centred care in patients with chronic heart failure: the PCC-HF study. Eur Heart J. 2012;33:1112–1119.

- Hagell P, Westergren A. The significance of importance: an evaluation of Ferrans and Powers' Quality of Life Index. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:867–876.

- Caress AL, Luker K, Woodcock A, et al. A qualitative exploration of treatment decision-making role preference in adult asthma patients. Health Expect. 2002;5:223–235.

- Keatinge D, Bellchambers H, Bujack E, et al. Communication: principal barrier to nurse-consumer partnerships. Int J Nurs Pract. 2002;8:16–22.

- Efraimsson E, Sandman PO, Hyden LC, et al. Discharge planning: "fooling ourselves?"-patient participation in conferences. J Clin Nurs. 2004;13:562–570.

- Frosch DL, Kaplan RM. Shared decision making in clinical medicine: past research and future directions. Am J Prev Med. 1999;17:285–294.

- Henderson A, Shum D. Decision-making preferences towards surgical intervention in a Hong Kong Chinese population. Int Nurs Rev. 2003;50:95–100.

- Drennan J. Cognitive interviewing: verbal data in the design and pretesting of questionnaires. J Adv Nurs. 2003;42:57–63.

- Soares JB, Nogueira MC, Fernandes D, et al. Validation of the Portuguese version of a questionnaire to measure Quality of Care Through the Eyes of Patients with Inflammatory Bowel Disease (QUOTE-IBD). Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;27:1409–1417.

- Tolonen H, Helakorpi S, Talala K, et al. 25-year trends and socio-demographic differences in response rates: Finnish adult health behaviour survey. Eur J Epidemiol. 2006;21:409–415.

- Curtin R, Presser S, Singer E. Changes in telephone survey nonresponse over the past quarter century. Public Opin Quart. 2005;69:87–98.

- Ekholm O, Hesse U, Davidsen M, et al. The study design and characteristics of the Danish national health interview surveys. Scand J Public Health. 2009;37:758–765.