?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Objectives

To examine the long-term efficacy and side effects of antitumour necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF) therapy in patients with Crohn’s disease (CD), the need for surgery and the clinical outcome after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy.

Material and methods

Data were collected from the inflammatory bowel disease (IBD)-TNF register at Østfold Hospital Trust. Clinical and sociodemographic data were recorded for patients initiating anti-TNF therapy from January 2000 until December 2011. Follow-up was conducted until December 2017.

Results

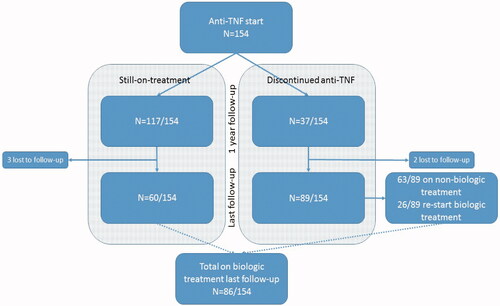

Complete remission (CR) was achieved in 40/154 (26%) patients at the last follow-up (median follow-up time 10 years). A total of 40 (26%) patients had to discontinue treatment due to serious side effects, and malignancy was recorded in 10 (6.5%) patients. Surgical resection was performed in 55 (36%) patients during follow-up. Patients with Montreal phenotype B2 before anti-TNF therapy were estimated to have a 2.54-fold greater risk of surgery than patients with phenotype B1 (p = .001). Of those with phenotype B1 before anti-TNF therapy, 19 (24%) of them developed stenosis in need of surgical resection (‘phenotype migration’). In patients followed up after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy (n = 89, median observational time six years), CR was achieved in most patients.

Conclusions

Long-term complete remission was achieved in only one in four patients receiving anti-TNF therapy, and one in four patients had to discontinue therapy due to side effects. Despite anti-TNF therapy, one in four patients with a baseline luminal disease phenotype needed subsequent surgical resection.

Introduction

Both infliximab and adalimumab are monoclonal antibodies directed against tumour necrosis factor alpha (anti-TNF). Randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have documented high short-term efficacy of anti-TNF for Crohn`s disease (CD) as well as for ulcerative colitis (UC) [Citation1–6].

There is, however, a lack of long-term observational studies on anti-TNF therapy in daily practice focusing on efficacy, adverse effects and safety [Citation7–12]. Moreover, recent studies have questioned the ability of anti-TNF to prevent the need for surgery in CD patients [Citation13–16], and only a few have reported on the long-term clinical course after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy either due to treatment failure, side effects, or remission [Citation17–21].

The primary aim of this observational study was to examine the efficacy and side effects of anti-TNF therapy in CD patients during an 18-year period. The secondary aims were to examine the long-term need for surgical resections after the initiation of anti-TNF therapy and explore the clinical outcome in individuals discontinuing anti-TNF therapies.

Materials and methods

Data were collected from the IBD-TNF register at Østfold Hospital Trust in the southeastern part of Norway – a hospital serving approximately 300,000 inhabitants. The register was established in 2009 and designed in accordance with the Danish prospective IBD register [Citation22]. The register contains clinical and sociodemographic data on all patients initiating anti-TNF therapy in the period from January 2000 until December 2011. Follow-up was conducted until December 2017. In this paper, we utilized data from the following: the one-year follow-up, last follow-up during anti-TNF therapy and last follow-up after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy.

Data description

Data including age, sex, smoking status, disease duration before anti-TNF therapy and history of surgical resection were recorded. The Montreal classification was used to classify disease location and behaviour [Citation23]. In addition, data concerning the type of anti-TNF therapy, concomitant immunomodulator or corticosteroids and faecal calprotectin levels were recorded. Dates of initiation of anti-TNF drug treatment, cause for discontinuation of anti-TNF drug treatment and surgical resection were also recorded.

Anti-TNF therapy – definitions

Patients receiving infliximab were treated either episodically or according to a specific schedule. Some patients started episodic treatment and later switched to a scheduled regimen. Any case of dose escalation was recorded. All patients on adalimumab were on a scheduled treatment regimen. Until 2013, the dose adjustment was largely based on a symptomatic response. Since 2014, trough levels have been used to optimize dosing.

A patient who switched to another anti-TNF therapy within four months of discontinuing the prior anti-TNF drug due to treatment failure or side effects was considered a case that was still receiving maintenance treatment. Patients restarting another biological drug after a period of more than four months were regarded as having anti-TNF treatment failures.

Scheduled follow-up

At one year and at the patient’s last follow-up appointment, data concerning efficacy and side effects were recorded based on medical records. Data on faecal calprotectin and relevant supplementary diagnostics were registered. The use of concomitant medication, side effects, surgical resections and mortality during the study period were also recorded.

Definition of disease activity

The overall composite assessment of treatment response/disease activity was based on Physician’s Global Assessment (PGA) of symptoms, faecal calprotectin values: <100 mg per kilo (negative value), 100–300 mg per kilo (limit value), >300 mg per kilo (elevated value), endoscopic findings, results of video capsule endoscopy, or radiological examinations – performed whenever clinically relevant and divided into the following categories:

Complete remission (CR) was consistent with a patient with no signs of Crohn’s disease activity based on a combination PGA of symptoms, negative calprotectin value < 100 mg per kilo and/or any other negative supplemental diagnostic test.

Partial response (PR) was consistent with a patient with mild disease activity based on a combination of PGA of symptoms, calprotectin ranging from 100 to 300 mg per kilo and/or mild disease activity confirmed by other diagnostic tests.

No response (NR) was consistent with a patient with moderate/severe disease activity based on a combination of PGA of symptoms, calprotectin value > 300 mg per kilo and/or moderate/severe disease activity confirmed by other diagnostic tests.

In cases of a discrepancy between the patient’s symptoms and calprotectin values, further diagnostic investigations, including endoscopy and/or relevant radiological examination, were used to conclude the therapeutic response/disease activity. In the early phase of the study, when calprotectin testing was not performed routinely, the patient’s response to therapy/disease activity status was based on symptoms and additional endoscopy/radiological examination.

Statistical analysis

Data are time-to-event data, where the event is considered to be a causative factor related to the discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy or surgical resection. Time was recorded from the start of anti-TNF therapy until the event or the time of last follow-up.

Discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy was stratified due to cause for discontinuation: treatment failure/side effects or complete remission. These are mutually contradictory causes and represent competing risks. This is handled in a multistate framework, which is an extension of conventional survival analyses with only two states [Citation24]. Transition probabilities from the ‘on-treatment’ state to each of the two discontinued states are estimated simultaneously along with transition-specific effects of covariates. The Kaplan–Meier plots used in conventional survival analyses were replaced by state-occupancy probability plots. The Cox proportional hazard model was employed to estimate hazards regarding both discontinuation from anti-TNF therapy and surgical resection.

Regarding discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy, we used age at diagnosis, age at start of anti-TNF treatment, smoking status (yes/no) and their pairwise interactions as covariates. For the surgery outcome, we used Montreal location and Montreal behaviour in addition to age at the start of anti-TNF treatment and smoking status. In addition, special combinations of location and behaviour were investigated for surgical resection. All Cox models were stratified by sex and transition. The models were estimated, and nonsignificant effects were removed one at a time, followed by re-estimation. This proceeded until all effects were significant.

All models were examined using residual plots.

We used R version 4.0.2 and the survival and mstate packages for all analyses.

Ethical considerations

Necessary approval was sought from the regional committee for medical and health research ethics. The study was, however, classified as a quality assurance study and was thus outside the committee's mandate. Approval was further obtained from the Norwegian Data Inspectorate.

Results

In total, the cohort included 154 CD patients. The main characteristics at baseline and during follow-up are presented in . At baseline, one-year, last follow-up during anti-TNF therapy and last follow-up after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy, calprotectin was available in 86%, 81%, 97% and 87% of patients, respectively.

Table 1. Baseline (n = 154) and follow-up characteristics of cohort.

Efficacy and side-effects of anti-TNF therapy

At one year and last follow-up (median follow-up time 10 years), complete remission (CR) was achieved in 66/154 (43%) and 40/154 (26%) patients, respectively. Furthermore, 20 patients (13%) were still on treatment and regarded as partial responders at the last follow-up. Three patients were lost to follow-up.

In those still on anti-TNF treatment at one year and at the last follow-up, 11% and 3% were on concomitant steroid use, respectively, whereas comparable figures for immunomodulators were 54% and 30%, respectively.

Registered side effects are presented in . In a total of 10 patients, malignancies were registered (). In those patients in whom malignancy was recorded, four had used azathioprine in addition to anti-TNF therapy. Moreover, two patients developed malignant melanoma 4 and 10 years after discontinuing anti-TNF, respectively (both on azathioprine).

Table 2. Registered side effects and malignancies during the follow-up period.

Surgical resection

Surgical resection was performed in 55/154 (36%) patients, of which 43/55 (78%) were surgically naïve. Twenty patients underwent surgery during anti-TNF therapy, and 35 patients underwent surgery shortly after discontinuation of anti-TNF therapy. The majority of patients had a limited surgical resection performed during follow-up (mostly an ileocecal resection), and in three patients intestinal stricturoplasty was performed in addition to resection.

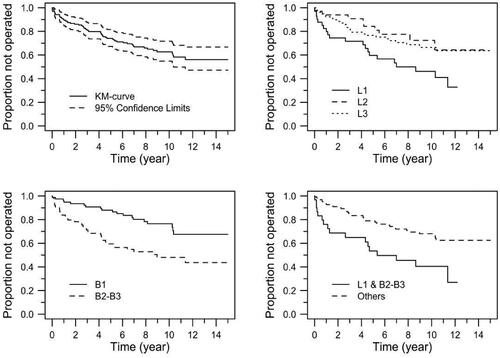

Of those with a B1 phenotype before anti-TNF therapy (n = 79, ), 24% developed stenosis and needed surgical resection (‘phenotype migration’), whereas 36/75 (48%) patients with a B2 or B3 phenotype needed surgical resection during the follow-up period. Patients with ileal disease location (n = 41) had the highest rate of surgery (n = 21 (51%)), and those in this group harbouring an additional B2 or B3 phenotype (n = 30) underwent surgical resection within 16 months (median).

The Cox models for risk factors for surgical resection considered the potential effects of Montreal behaviour (B1 vs. B2/B3) and location (L1 vs. L2/L3), smoking (y/n), age at start of anti-TNF therapy and age at diagnosis. After the removal of nonsignificant effects followed by re-estimation, only Montreal behaviour showed a significant effect (p = .001), with patients in the B2–B3 category having a 2.54 increased risk relative to B1 patients.

Montreal location showed, however, indications of significant differences between levels L1, L2 and L3 with respect to the risk of surgery. A model that only included this variable was consequently estimated. It estimated L2 and L3 to have 57% and 51% reduced risk of surgery, respectively, relative to L1 patients (p = .037 and .018, respectively). This model was, however, inferior to the first model, measured by Akaike’s Information Criteria (AIC).

A third model was motivated by an interest in the combination of location level L1 with behaviour classes B2 or B3. Thirty out of 154 patients (19%) were identified with this combination. These patients were estimated to have a 2.6-fold higher risk of surgery (p = .001) than patients outside this category (see and ).

Figure 1. Kaplan–Meier curves for the risk of surgical resection for various configurations. TL: overall; TR: location; BL: Behaviour; BR: L1 and B2–B3 vs. others.

Table 3. Models and estimates for risk of surgical resection.

Causes of discontinuation and follow-up after anti-TNF therapy

At the last follow-up, 91 patients (59%) had discontinued treatment, either due to treatment failure n = 43 (28%), side effects n = 40 (26%), clinical remission n = 19 (12%), or other reasons n = 16 (10%).

Of those who had eventually stopped anti-TNF therapy due to remission, six patients (32%) relapsed and were successfully retreated with the primary choice of anti-TNF therapy.

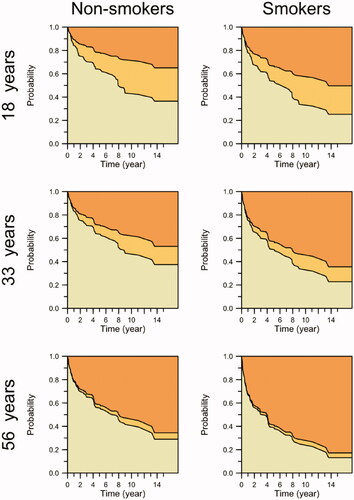

Based on estimates of transition-specific effects in a semiparametric Cox model, the risk of discontinuation due to treatment failure/side effects was estimated to increase by 1.9% for each year increase (p = .025). Smoking was estimated to increase the risk of discontinuation due to treatment failure/side effects by 65% (p = .05), whereas it had no effect on the chances of discontinuation due to remission. Age at the start of anti-TNF therapy was estimated to decrease the chances of discontinuation due to remission by 4.0% (p = .04) and increase the risk of discontinuation due to treatment failure/side effects by 1.8% (p = .02) for each year increase. All other effects tested were nonsignificant. The effects are illustrated in , and parameter estimates are shown in .

Figure 2. Estimated state probabilities by smoking status and age class. From bottom up: still on treatment, discontinuation due to remission, discontinuation due to treatment failure/side effects.

Table 4. Estimated effects for chance/risk of discontinuation due to opposing causes.

Eighty-nine patients who discontinued anti-TNF therapy were followed for a median observational time of six years. Of these, 10% were using corticosteroids and 42% were using an immunomodulator. In those on nonbiological therapy at the last follow-up, CR was achieved in 32 of 63 patients (51%). In those being operated during anti-TNF therapy (n = 20) or shortly after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy (n = 35), long-term CR was achieved in 31 of 55 patients (62%). In those with a non-obstructive phenotype before starting anti-TNF therapy, CR was achieved in 28 of 49 patients (57%). These subgroup rates of long-term CR are comparable to the overall success rate of 55% (n = 89) in patients who had previously discontinued anti-TNF therapy.

Altogether, 26/89 patients (29%) had restarted alternative biological therapy (vedolizumab n = 9, infliximab n = 8, adalimumab n = 6, ustekinumab n = 2 and certolizumab n = 1). Among re-starters (median time to re-start 36 months), 17 patients (65%) achieved CR (observational time after re-start, median 20 months) (). gives an overview of all patients in the cohort who were still on anti-TNF treatment or had stopped anti-TNF treatment, and summarizing all patients on biologic treatment at the final follow-up.

Table 5. Long-term outcome on biologics including biologic re-starters.

Discussion

In this unselected cohort of Crohn’s disease patients on long-term anti-TNF therapy, we observed a low number of patients still in complete remission as well as a high number of patients with ‘phenotype migration’ and a need for surgery. Interestingly, in those who had to discontinue anti-TNF therapy, a majority were in complete remission during long-term follow-up.

In the current study, a substantial drop in long-term ‘drug survival’ was demonstrated beyond the one-year follow-up, and the success rate was consequently lower than that of comparable observational studies by Schnitzler et al. [Citation9] and Eshuis et al. [Citation12]. Juillerat et al. [Citation11] found that 40% of the initial cohort continued infliximab after 10 years, which aligns with our results when partial responders were considered.

Faecal calprotectin has clearly been the most important diagnostic test guiding the principal investigator to correctly classify each patient’s disease activity/treatment response. Many have underlined the limitations of using symptom scores like CDAI to classify disease activity in Crohn’s disease as opposed to relying on biomarkers like faecal calprotectin and endoscopy to define more precisely the true disease activity [Citation25–27].

In comparison to our long-term complete remission rate of 26%, Kamm et al. [Citation28] and Panaccione et al. [Citation29] showed, in the CHARM/ADHERE study population, 23% and 20% steroid-free remission rate after three and four years of adalimumab treatment, respectively, in patients with Crohn`s disease. Long-term follow-up in the TAILORIX cohort comprising Crohn’s disease patients with a shorter disease duration before starting anti-TNF (median four months), demonstrated a steroid-free remission rate of 50% after five years follow-up [Citation30].

Our strict definition of complete remission includes both the absence of IBD-related symptoms and a negative calprotectin value < 100 mg per kilo and supportive supplemental diagnostics (endoscopy and radiological examination whenever indicated). The median value of calprotectin was 60 mg per kilo in those classified as being in long-term complete remission. At the last follow-up, two of 60 patients (3%) who were still receiving anti-TNF therapy were taking additional corticosteroids at a low dosage (< 10 mg per day). Hence, by definition, our patients who were assessed as being in long-term complete remission were in fact in steroid-free remission. By defining complete remission by using such a low cut-off value of calprotectin, it is suggestible that these patients also were in ‘deep remission’ (that is inactive endoscopic disease). The strong correlation between consecutive low calprotectin levels < 100 mg per kilo and inactive disease has been demonstrated in previous studies [Citation31–33].

We found that smoking, age at start of anti-TNF therapy and length of therapy were significant factors estimated to increase the risk of discontinuation due to treatment failure/side effects. This aligns with findings in previous publications [Citation10–12,Citation34,Citation35]. Gisbert et al. on the other hand conclude in a recent review that smoking has not been confirmed having a negative impact on the efficacy of anti-TNF therapy in Crohn’s disease [Citation36].

To fully recognize the side effects and safety profile of potent medical therapy, long-term observational studies may be more useful than randomized controlled studies with short-term follow-up. In our cohort 10 patients developed malignancies, of whom five died. These numbers are consequently worrisome, and only a minority had used azathioprine in addition to anti-TNF therapy. In addition, none of the patients who died used azathioprine in addition to anti-TNF therapy.

Lees et al. [Citation37] investigated the safety profile of long-term anti-TNF therapy in a cohort of 202 patients in Edinburgh, in which 3% were diagnosed with malignancy, whereas Fidder et al. [Citation38] in Leuven, Belgium reported that 2.8% in a cohort of 734 patients receiving infliximab developed malignancy. Karmiris et al. [Citation39] reported 7 cancers in 5 out of 148 adalimumab-treated patients (3.4%).

Altogether, one of the three patients underwent surgical resection during long-term follow-up, and the majority were ‘surgical naïve’. Not surprisingly, the majority of those who underwent surgery had an obstructive Crohn’s disease phenotype at the start of anti-TNF therapy. Other factors examined in the Cox regression analysis, such as smoking, age at diagnosis and age at start of anti-TNF therapy, did not seem to increase the risk of surgery. Patients with ileal disease (L1) had the highest operation rate, as well as the shortest interval from initiating anti-TNF therapy to surgery. Early ileocecal resection as an alternative therapeutic strategy to anti-TNF therapy in this subgroup of patients has recently been recommended in the LIR!C study [Citation40].

Notably, one in four patients with a luminal phenotype (B1) before anti-TNF therapy needed long-term subsequent surgical treatment (‘phenotype migration’). Indeed, recent studies have questioned the ability of anti-TNF therapy to prevent phenotype migration as well as repeated surgical resections in Crohn’s disease [Citation13–16]. Our rates of long-term surgery in Crohn’s disease are in concordance with rates shown in long-term follow-up in the IBSEN cohort in the prebiological era, thus suggesting a limited effect of anti-TNF therapy in preventing IBD-related surgery [Citation41].

In our cohort, a minority of patients had eventually stopped anti-TNF therapy due to remission, and after long-term observation, one of three relapsed and was successfully retreated with the primary choice of anti-TNF therapy. This is in accordance with data presented by Casanova et al. [Citation18] and long-term follow-up results of the STORI trial [Citation20].

There is a lack of data on long-term outcomes after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy. In our study, more than half of the patients who discontinued anti-TNF therapy, irrespective of ongoing therapy, were in complete remission, with a minority of 10% using concomitant corticosteroids. More precisely, at the last follow-up after discontinuing anti-TNF therapy, 61% of the patients had a calprotectin value < 100 mg pr kilo with a median value of 36 mg pr kilo in those classified as being in complete remission. This suggests that a high proportion of patients who initially needed intensified therapy might have a milder disease course long-term, achieving deep remission, without the need for potent long-term immunomodulators or biologics. Although not fully comparable, this phenomenon was also noticed in long-term follow-up of Crohn’s patients in the IBSEN cohort [Citation41].

This retrospective observational study has methodological weaknesses. First, the overall composite assessment of disease activity, performed exclusively by the PI, was based on data collection from electronic health records. Second, disease activity stratification was partly based on the physicians’ global assessment of symptoms (‘clinical judgement’) but strongly influenced by objective diagnostics, especially repeated faecal calprotectin testing, as recommended by international guidelines [Citation42]. At the last follow-up, nearly all patients had a representative calprotectin value to objectively determine disease activity and furthermore reduce any classification bias. Unlike most RCTs that have a short observation time, this patient population with long-term follow-up represents an unselected real-life cohort from a single hospital with a low dropout rate.

Conclusion

Long-term complete remission in patients receiving primary anti-TNF therapy was achieved in only one in four patients. Moreover, one in four patients had to discontinue therapy due to side effects. The combination of an ileal disease location and an obstructive phenotype increased the risk of surgery nearly threefold. Despite anti-TNF therapy, one in four patients with a baseline luminal disease phenotype needed subsequent surgical treatment. Of those discontinuing anti-TNF therapy, most were in complete remission six years later, and the majority were on nonbiological therapy without corticosteroids.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to MD Eva Günther for participation in data collection from electronic health records

Disclosure statement

Professor Jelsness-Jørgensen has served as a speaker for Ferring Pharmaceuticals and Takeda, as well as member of advisory board for Takeda. None of these were related to the submitted work. None of the other authors have any disclosures to report.

Data availability statement

Data is available from the first author

Additional information

Funding

References

- Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362(15):1383–1395.

- Rutgeerts P, Sandborn WJ, Feagan BG, et al. Infliximab for induction and maintenance therapy for ulcerative colitis. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(23):2462–2476.

- Danese S, Colombel JF, Reinisch W, et al. Review article: infliximab for Crohn's disease treatment-shifting therapeutic strategies after 10 years of clinical experience. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;33(8):857–869.

- Danese S, Vuitton L, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Biologic agents for IBD: practical insights. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;12(9):537–545.

- Nielsen OH, Ainsworth MA. Tumor necrosis factor inhibitors for inflammatory bowel disease. N Engl J Med. 2013;369(8):754–762.

- Hindryckx P, Vande Casteele N, Novak G, et al. The expanding therapeutic armamentarium for inflammatory bowel disease: how to choose the right drug[s] for our patients? J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(1):105–119.

- Sprakes MB, Ford AC, Warren L, et al. Efficacy, tolerability, and predictors of response to infliximab therapy for Crohn's disease: a large single centre experience. J Crohns Colitis. 2012;6(2):143–153.

- O'Donnell S, Murphy S, Anwar MM, et al. Safety of infliximab in 10 years of clinical practice. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;23(7):603–606.

- Schnitzler F, Fidder H, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in 614 patients with Crohn's disease: results from a single-centre cohort. Gut. 2009;58(4):492–500.

- Chaparro M, Panes J, Garcia V, et al. Long-term durability of infliximab treatment in Crohn's disease and efficacy of dose "escalation" in patients losing response. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2011;45(2):113–118.

- Juillerat P, Sokol H, Froehlich F, et al. Factors associated with durable response to infliximab in Crohn's disease 5 years and beyond: a multicenter international cohort. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21(1):60–70.

- Eshuis EJ, Peters CP, van Bodegraven AA, et al. Ten years of infliximab for Crohn's disease: outcome in 469 patients from 2 tertiary referral centers. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19(8):1622–1630.

- Burisch J, Kiudelis G, Kupcinskas L, et al. Natural disease course of Crohn's disease during the first 5 years after diagnosis in a European population-based inception cohort: an Epi-IBD study. Gut. 2019;68(3):423–433.

- Lo B, Vester-Andersen MK, Vind I, et al. Changes in disease behaviour and location in patients with Crohn's disease after seven years of follow-up: a Danish population-based inception cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2018;12(3):265–272.

- Jeuring SF, van den Heuvel TR, Liu LY, et al. Improvements in the long-term outcome of Crohn's disease over the past two decades and the relation to changes in medical management: results from the population-based IBDSL cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(2):325–336.

- Jeuring SFG, Biemans VBC, van den Heuvel TRA, et al. Corticosteroid sparing in inflammatory bowel disease is more often achieved in the immunomodulator and biological era-results from the dutch population-based IBDSL cohort. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(3):384–395.

- Buhl S, Steenholdt C, Rasmussen M, et al. Outcomes after primary infliximab treatment failure in inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(7):1210–1217.

- Casanova MJ, Chaparro M, García-Sánchez V, et al. Evolution after anti-TNF discontinuation in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: a multicenter long-term follow-up study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2017;112(1):120–131.

- Molander P, Farkkila M, Kemppainen H, et al. Long-term outcome of inflammatory bowel disease patients with deep remission after discontinuation of TNFα-blocking agents. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(3):284–290.

- Reenaers C, Mary JY, Nachury M, et al. Outcomes 7 years after infliximab withdrawal for patients with Crohn's disease in sustained remission. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(2):234–243.e2.

- Torres J, Boyapati RK, Kennedy N, et al. Systematic review of effects of withdrawal of immunomodulators or biologic agents from patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2015;149(7):1716–1730.

- Caspersen S, Elkjaer M, Riis L, et al. Infliximab for inflammatory bowel disease in Denmark 1999-2005: clinical outcome and follow-up evaluation of malignancy and mortality. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(11):1212–1217.

- Silverberg MS, Satsangi J, Ahmad T, et al. Toward an integrated clinical, molecular and serological classification of inflammatory bowel disease: report of a working party of the 2005 Montreal world congress of gastroenterology. Can J Gastroenterol. 2005;19 Suppl A (Suppl A):5A–36A.

- de Wreede LC, Fiocco M, Putter H. Mstate: an r package for the analysis of competing risks and multi-state models. J Stat Softw. 2011;38(7):1–30.

- Peyrin-Biroulet L, Reinisch W, Colombel JF, et al. Clinical disease activity, C-reactive protein normalisation and mucosal healing in Crohn's disease in the SONIC trial. Gut. 2014;63(1):88–95.

- Wong ECL, Buffone E, Lee SJ, et al. End of induction patient-reported outcomes predict clinical remission but not endoscopic remission in Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2021;15(7):1114–1119.

- Colombel JF, Panaccione R, Bossuyt P, et al. Effect of tight control management on Crohn's disease (CALM): a multicentre, randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2017;390(10114):2779–2789.

- Kamm MA, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, et al. Adalimumab sustains steroid-free remission after 3 years of therapy for Crohn's disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(3):306–317.

- Panaccione R, Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, et al. Adalimumab maintains remission of Crohn's disease after up to 4 years of treatment: data from CHARM and ADHERE. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2013;38(10):1236–1247.

- Laharie D, D’Haens G, Nachury M, et al. Steroid-Free deep remission at one year does not prevent Crohn's disease progression: long-term data from the TAILORIX trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2021.DOI:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cgh.2021.11.030.

- Schoepfer AM, Beglinger C, Straumann A, et al. Fecal calprotectin correlates more closely with the simple endoscopic score for Crohn's disease (SES-CD) than CRP, blood leukocytes, and the CDAI. Am J Gastroenterol. 2010;105(1):162–169.

- Mooiweer E, Severs M, Schipper ME, et al. Low fecal calprotectin predicts sustained clinical remission in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a plea for deep remission. J Crohns Colitis. 2015;9(1):50–55.

- Molander P, Kemppainen H, Ilus T, et al. Long-term deep remission during maintenance therapy with biological agents in inflammatory bowel diseases. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2020;55(1):34–40.

- Rudolph SJ, Weinberg DI, McCabe RP. Long-term durability of Crohn's disease treatment with infliximab. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53(4):1033–1041.

- Rozich JJ, Holmer A, Singh S. Effect of lifestyle factors on outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020;115(6):832–840.

- Gisbert JP, Chaparro M. Predictors of primary response to biologic treatment [anti-TNF, vedolizumab, and ustekinumab] in patients with inflammatory bowel disease: from basic science to clinical practice. J Crohns Colitis. 2020;14(5):694–709.

- Lees CW, Ali AI, Thompson AI, et al. The safety profile of anti-tumour necrosis factor therapy in inflammatory bowel disease in clinical practice: analysis of 620 patient-years follow-up. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29(3):286–297.

- Fidder H, Schnitzler F, Ferrante M, et al. Long-term safety of infliximab for the treatment of inflammatory bowel disease: a single-centre cohort study. Gut. 2009;58(4):501–508.

- Karmiris K, Paintaud G, Noman M, et al. Influence of trough serum levels and immunogenicity on long-term outcome of adalimumab therapy in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2009;137(5):1628–1640.

- Ponsioen CY, de Groof EJ, Eshuis EJ, et al. Laparoscopic ileocaecal resection versus infliximab for terminal ileitis in Crohn's disease: a randomised controlled, open-label, multicentre trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2017;2(11):785–792.

- Solberg IC, Vatn MH, Hoie O, et al. Clinical course in Crohn's disease: results of a Norwegian population-based ten-year follow-up study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5(12):1430–1438.

- Gomollon F, Dignass A, Annese V, et al. 3rd European evidence-based consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease 2016: part 1: diagnosis and medical management. J Crohns Colitis. 2017;11(1):3–25.