Abstract

Objectives

The aim of this study was to investigate the potential correlation between muscle mass/muscle quality and risk of complications or recurrence in patients presenting with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. It was also to study if low muscle mass/quality correlated to prolonged hospital stay.

Materials and methods

The study population comprised 501 patients admitted to Helsingborg Hospital or Skåne University Hospital between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017, who had been diagnosed with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis and undergone computed tomography upon admission. The scans were used to estimate skeletal muscle mass and muscle radiation attenuation (an indicator for muscle quality). Skeletal muscle index was obtained by adjusting skeletal muscle mass to the patients’ height. Values of below the fifth percentile of a normal population were considered low.

Results

There were no differences between the patients with normal versus those with low skeletal muscle mass, skeletal muscle index or muscle radiation attenuation regarding risk of complications or recurrence of diverticular disease. However, as only 11 patients had complications, no conclusion as to a potential correlation can be made. Low muscle quality correlated to longer hospital stay, also when adjusting for other potential confounders.

Conclusions

Muscle mass/quality do not seem to serve as predictor of risk for recurrent disease in patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. However, low muscle radiation attenuation was associated with prolonged hospital stay. This indicates that muscle quality, assessed by computed tomography scan, might be used in clinical practise to identify patients at risk of longer hospitalisation.

Introduction

Acute uncomplicated diverticulitis is defined as clinical and radiological signs of inflammation around a part of bowel with diverticula, without signs of complications, such as abscess or fistula formation, perforation, obstruction or stricture [Citation1]. It is a common condition in patients visiting surgical emergency departments. Treatment with antibiotics is often redundant and most patients can safely be treated in an out-patient setting [Citation1–3]. However, some patients presenting with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis develop complicated disease. In addition, some are burdened by recurrent disease and would benefit from a sigmoid resection.

Earlier identification and prediction of patients at risk of complications and recurrent disease would enable treatment optimisation and a more individualised follow-up.

Muscle mass has been put forward as a potential predictor for clinical outcome and gained increasing interest, especially in geriatric [Citation4,Citation5] and oncological cohorts [Citation6,Citation7]. Low muscle mass has been related to adverse outcome after emergency surgery in acute diverticulitis [Citation8] and after cancer surgery [Citation9]. A low muscle mass may emanate from cachexia associated with an underlying disease, alternatively be a consequence of sarcopenia. Sarcopenia is characterised by loss of muscle mass and function related to aging, but may also affect younger individuals [Citation10].

When a patient presents at the emergency department, computed tomography (CT) imaging is recommended to confirm first time diverticulitis diagnosis and discriminate between uncomplicated from complicated diverticulitis [Citation1]. A single abdominal cross-sectional CT image can be used to estimate the total-body skeletal muscle volume and the muscle quality [Citation11,Citation12].

The main objective of this study was to investigate if measurements indicative of low muscle mass or low muscle quality correlate with the occurrence of complications and recurrence in patients presenting with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. A secondary aim was to assess if such measurements correlate to prolonged hospital stay.

Materials and methods

The study cohort was a sub-set from a previous study on the use of antibiotics in the treatment of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis [Citation13]. The larger original cohort included adult (≥18 yrs) patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis admitted to Helsingborg Hospital and Skåne University Hospital between 1 January 2015 and 31 December 2017. The patients had been identified from the discharge registry by the ICD-10 code K57.3 and subsequently scrutinized for inclusion. Ongoing pre-admission antibiotic treatment and immunosuppressant treatment were exclusion criteria.

Eligible patients for inclusion in the present study were those with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis as the principal diagnosis, the absence of signs of complicated diverticulitis upon admission and a correctly performed abdominal CT-scan.

The CT scans had been performed according to local radiology protocols: supine patient position with elevated arms, a craniocaudal scan direction and slice thickness of 1, 2, or 5 mm. Intravenous contrast was administered when kidney function was adequate, the standard dose was 500 mg iodine per kilogram, using Omnipaque 350 mg/ml injected during 25 s if the glomerular filtration rate was normal.

Medical records were reviewed for clinical and demographic information. The Charlson comorbidity index was calculated based on intercurrent diseases [Citation14]. The duration of hospital stay (days) and occurrence of complications were recorded. A long hospital stay was defined as being above the median hospital stay for the investigated cohort. Medical charts were checked for follow-up information on complications and recurrence of diverticulitis for 12 months following discharge. Complications were defined as perforation, abscess, obstruction or fistula. Recurrence was defined as a new episode of diverticulitis >30 days from index admission.

The CT scans performed at admission were retrieved from the Picture Archiving and Communications System. A cross-sectional abdominal slice in axial projection at the level of the upper plate of the third lumbar vertebra from each included patient was analysed for muscle mass and muscle quality using ImageJ which is an image processing open source software for scientific image analysis (https://imagej.nih.gov).

Each cross-sectional image was analysed for total body skeletal muscle mass and muscle radiation attenuation. Relevant muscle tissue (psoas, erector spinae, quadratus lumborum, transverse abdominis, external and internal obliques, and rectus abdominis) was delineated to avoid analysis of abdominal content, bone, subcutaneous fat and skin. The threshold values −29 through +150 Hounsfield Units (HU) were applied for muscle tissue as described previously [Citation12]. Hereafter, the software calculated the skeletal muscle mass and mean HU (muscle radiation attenuation). The latter is a surrogate measure for muscle quality, as lower radiation attenuation indicate higher amount of muscle mass fat infiltration [Citation4]. Relative total skeletal muscle mass, i.e., skeletal muscle index was derived by dividing skeletal muscle mass with the patient’s squared height (m2).

Cut-off values for a low skeletal muscle mass, skeletal muscle index and muscle radiation attenuation were defined and tested using two different approaches. Both approaches have been proposed by van der Werf et. al. based on measurements from a healthy population of potential kidney donors [Citation15]. For the simpler approach gender specific skeletal muscle mass, skeletal muscle index and muscle radiation attenuation low-cut-off values were solely based on whether a value was below the fifth percentile (men: skeletal muscle mass 134 cm,2 skeletal muscle index 41.6 cm2/m,2 muscle radiation attenuation 29.3 HU; women: skeletal muscle mass 89.2 cm,2 skeletal muscle index 32 cm2/m,2 muscle radiation attenuation 22 HU) [Citation15]. For the more compound approach, which required data on height and weight, cut-off values (based on the lower fifth percentile) for specific age and body mass index (BMI)-intervals were used [Citation15]. Our rationale for deploying both approaches is the lack of a gold standard. Gender-based cut-off values are presumably easier to implement in clinical practise but by including age and BMI the predictive potential may be more precise.

The study was approved by the Regional Ethics Committee in Southern Sweden (Dnr 2018/980).

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 25.

Clinical and demographic patient variables are presented as median values and interquartile range (IQR). Primary outcome was complication and recurrence of diverticulitis. Secondary outcome was long hospital stay. The outcomes were analysed in relation to low/normal muscle mass and low/normal muscle quality and presented in cross tabulations. The Chi square-test was used to test statistical significance. Due to multiple comparisons, a p-value <0.01 was considered statistically significant.

Values statistically significant in the cross-tabulation were analysed with logistic regression analyses, resulting in odds ratios (OR) with confidence intervals (CI). The analyses were adjusted for C-reactive protein, white blood cell count and Charlson morbidity index.

Levels of inflammatory markers (C-reactive protein and white blood count) for the patients who had complications and those with recurrence were compared with those who had uncomplicated disease without recurrence. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to test for statistical significance.

Results

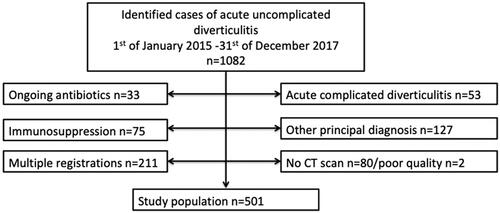

In all, 1082 admissions were coded with the discharge code K57.3. Of these, 211 individuals were admitted multiple times and were thus only included at index admission, leaving 871 potentially suitable patients for study inclusion. After exclusion according to the above mentioned exclusion criteria, 501 constituted the final study population ().

Characteristics of the study population are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of the study population, values are presented as median (interquartile range).

In 63 patients data on weight were missing in medical records and/or data on height in 39. Thus, BMI could not be calculated in 74 patients and skeletal muscle index could not be calculated in 39 patients.

Approximately 10–20% of the study population were assessed to have low muscle mass or muscle quality ().

Table 2. Proportions of patients with low versus normal muscle mass and muscle quality.

Eleven (2.2%) of 501 patients developed complication to acute uncomplicated diverticulitis (abscess n = 4, perforation and abscess n = 4, fistula n = 1, other n = 1) and 112 (22.3%) patients had recurrence of disease during the 12-month follow up. In all, 215 patients (43%) had stayed in hospital longer than three days.

At admission, the patients with complications had a median C-reactive protein of 193 (IQR 128–299) and white blood count of 13.8 (IQR 11.3–15.8) compared with patients without complications 126 (IQR 80–183; p = 0.063) and 12.3 (IQR 10.3–14.6; p = 0.052). Those with recurrence had median C-reactive protein of 117 (IQR 67–165) and white blood count of 12.4 (IQR 10.1–14.3) compared with patients without recurrence 129 (IQR 83–190; p = 0–35) and 12.3 (IQR 10.3–14.9; p = 0.51).

Cross-tabulations showing proportions of patients with low versus normal muscle mass (skeletal muscle mass/skeletal muscle index) and low muscle quality (muscle radiation attenuation) in relation to complications, recurrence of disease, and hospital duration over three days are presented in .

Table 3. Muscle mass/quality in relation to complications, recurrences and length of hospital stay.

No difference was observed for complications or recurrence of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis in patients with low skeletal muscle mass/skeletal muscle index/muscle radiation attenuation. Patients with low skeletal muscle mass had significantly more often longer hospital duration when using the simpler low-cut-off value approach for skeletal muscle mass. However, the difference did not remain when using the age and BMI adjusted cut-off for skeletal muscle mass.

A low muscle radiation attenuation based on the age and BMI adjusted cut-off was on the other hand associated with longer hospital stay (p-value 0.001). Logistic regression analysis adjusted for C-reactive protein, white blood cell count, and Charlson morbidity index resulted in an OR of 2.95 (CI 1.39–6.24).

Discussion

In this study, no association was detected between low muscle mass or low muscle quality and the development of complications or recurrence in patients presenting with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. However, as only 11 patients had complicated disease, no conclusion concerning the association with this outcome can be made. It was observed that patients with low muscle quality on a whole were hospitalised for a longer period of time, also after adjusting for confounders.

To our knowledge, no previous study has analysed muscle mass and muscle quality by using CT scan in a population presenting with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. We hypothesised that low skeletal muscle mass, skeletal muscle index and muscle radiation attenuation could be risk factors for developing a complicated course of disease and/or recurrence but this could not be shown. Since the incidence of complications (n = 11) was low, there is a risk of type II error. However, the incidence of recurrent disease was high and if low muscle mass or muscle quality were predictive of recurrence it should have been evident in this study.

The only previous published study focusing on muscle mass and patients with diverticulitis is by Matsushima et. al. [Citation8] which included 89 patients who had undergone emergency surgery due to acute diverticulitis. They assessed muscle mass by measuring the cross-sectional area and the transverse diameter of the psoas muscles and reported that patients with lower cross-sectional area and transverse diameter were at higher risk of major complications and surgical site infections. Comparisons between the study by Matsushima and our present study are difficult due to several reasons. The patients in the study cohorts had differing disease course and no one in our study needed emergency surgery. Also, the studies diverged in methods of measuring muscle mass. Although Matsushima et. al. restricted muscle mass measurements to the area and diameter of the psoas muscle, we estimated the total body muscle mass, which is the most common method when researching body composition [Citation10].

Another difficulty when comparing studies is the different use of cut-off values when defining low versus normal muscle mass. In the study by Matsushima, as in several other studies [Citation6], cut-off values were relative and based on the values of the examined study population. This makes it challenging to compare results between different cohorts and studies, but also to assess how generalizable the results are to the population at large.

Most previous studies investigating muscle mass and muscle quality, using the same cut-off methodology [Citation15] as we did, were performed on geriatric populations or patients with malignancies [Citation5,Citation16–18]. Our study cohort was neither defined by age nor defined by a cancer diagnosis but comprised of consecutive patients presenting with symptoms of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis at the emergency department.

Since the population in the present study comprised neither geriatric nor oncological patients, cut-off values from a healthy population of potential kidney donors published by van der Werf et. al. were used. Nevertheless, the patients in the present study were older and had higher BMI than in the study by van der Werf et. al. (mean age was 53 compared with 61 and mean BMI 25.7 compared to 27.7) [Citation15]. This could explain the higher proportion of patients with low muscle mass and muscle quality in the present study.

The identified association between low muscle quality (muscle radiation attenuation) and a prolonged hospital stay is interesting. A low muscle radiation attenuation indicates an increased level of muscle fat infiltration [Citation19] and previous studies have concluded that a low muscle radiation attenuation increase the risk of mobility limitations [Citation4,Citation20]. Whether low muscle radiation attenuation evaluated by CT scan can be a useful predictor of prolonged hospital stay and to identify patients at risk, requires further research.

Limitations of the present study include its retrospective design, where the ability to collect data was dependant on the completeness of the medical records. Due to missing data on weight and height, a proportion of the patients could not be analysed using the BMI adjusted cut-offs. As data on smoking status and alcohol intake could not be retrieved, results could not be adjusted for these potential confounding factors. Furthermore, results are only generalizable to immunocompetent patients.

Another limitation is the relatively low incidence of complications (2.2%), which is a result in line with previous studies on acute uncomplicated diverticulitis [Citation2,Citation3]. The investigated cohort would have had to be larger to yield conclusive results as to whether muscle mass and quality can predict the development of complications.

Since the follow-up was limited to scrutinization of medical journals at the two hospital where patients presented on their index admission there is a risk of missing relevant follow up information, e.g., if a patient sought primary care. This risk is however small since complications requiring intravenous antibiotics, drainage and/or surgical interventions are treated exclusively in hospitals.

Despite the study limitations, we consider the results to be of value. Measurements of muscle mass and muscle quality do not appear to enhance the predictability of which patients with acute uncomplicated diverticulitis, who present at the emergency room, are at risk of recurrence of diverticulitis. As the incidence of complications was low, a potential association between complications and measurements of muscle mass and muscle quality cannot be concluded in this study. However, the observation that muscle quality is correlated to prolonged hospital stay, regardless of age, comorbidity, and disease severity, may be useful for physicians. If patients with increased risk of prolonged hospital stay can be identified at admission, measures might be taken to optimize care and adjustable factors to enable an earlier discharge.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Schultz JK, Azhar N, Binda GA, et al. European society of coloproctology: guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the Colon. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(Suppl 2):5–28.

- Daniels L, Unlu C, de Korte N, Dutch Diverticular Disease (3D) Collaborative Study Group, et al. Randomized clinical trial of observational versus antibiotic treatment for a first episode of CT-proven uncomplicated acute diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2017;104(1):52–61.

- Chabok A, Pahlman L, Hjern F, AVOD Study Group, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(4):532–539.

- Visser M, Goodpaster BH, Kritchevsky SB, et al. Muscle mass, muscle strength, and muscle fat infiltration as predictors of incident mobility limitations in well-functioning older persons. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2005;60(3):324–333.

- Baumgartner RN, Koehler KM, Gallagher D, et al. Epidemiology of sarcopenia among the elderly in New Mexico. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147(8):755–763.

- Rier HN, Jager A, Sleijfer S, et al. The prevalence and prognostic value of low muscle mass in cancer patients: a review of the literature. Oncologist. 2016;21(11):1396–1409.

- Shachar SS, Williams GR, Muss HB, et al. Prognostic value of sarcopenia in adults with solid tumours: a meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur J Cancer. 2016;57:58–67.

- Matsushima K, Inaba K, Jhaveri V, et al. Loss of muscle mass: a significant predictor of postoperative complications in acute diverticulitis. J Surg Res. 2017;211:39–44.

- Xia L, Zhao R, Wan Q, et al. Sarcopenia and adverse health-related outcomes: An umbrella review of meta-analyses of observational studies. Cancer Med. 2020;9(21):7964–7978.

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2, et al. Sarcopenia: revised european consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019;48(1):16–31.

- Heymsfield SB, Wang Z, Baumgartner RN, et al. Human body composition: advances in models and methods. Annu Rev Nutr. 1997;17:527–558.

- Shen W, Punyanitya M, Wang Z, et al. Total body skeletal muscle and adipose tissue volumes: estimation from a single abdominal cross-sectional image. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2004;97(6):2333–2338.

- Azhar N, Aref H, Brorsson A, et al. Management of acute uncomplicated diverticulitis without antibiotics: compliance and outcomes -a retrospective cohort study. BMC Emerg Med. 2022;22(1):28.

- Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, et al. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383.

- van der Werf A, Langius JAE, de van der Schueren MAE, et al. Percentiles for skeletal muscle index, area and radiation attenuation based on computed tomography imaging in a healthy caucasian population. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(2):288–296.

- Dunne RF, Roussel B, Culakova E, et al. Characterizing cancer cachexia in the geriatric oncology population. J Geriatr Oncol. 2019;10(3):415–419.

- Gingrich A, Volkert D, Kiesswetter E, et al. Prevalence and overlap of sarcopenia, frailty, cachexia and malnutrition in older medical inpatients. BMC Geriatr. 2019;19(1):120.

- Kazemi-Bajestani SM, Mazurak VC, Baracos V. Computed tomography-defined muscle and fat wasting are associated with cancer clinical outcomes. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2016;54:2–10.

- Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Thaete FL, et al. Skeletal muscle attenuation determined by computed tomography is associated with skeletal muscle lipid content. J Appl Physiol (1985). 2000;89(1):104–110.

- Visser M, Kritchevsky SB, Goodpaster BH, et al. Leg muscle mass and composition in relation to lower extremity performance in men and women aged 70 to 79: the health, aging and body composition study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50(5):897–904.