Abstract

Background

Diverticulitis and colorectal cancer (CRC) share epidemiological characteristics, but their relationship remains unknown. It is unclear if prognosis following CRC differ for patients with previous diverticulitis compared to those with sporadic cases and patients with inflammatory bowel disease or hereditary syndromes.

Aim

The aim was to determine 5-year survival and recurrence after colorectal cancer in patients with previous diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease and hereditary colorectal cancer compared to sporadic cases.

Methods

Patients <75 years of age diagnosed with colorectal cancer at Skåne University Hospital Malmö, Sweden, between January 1st 2012 and December 31st 2017 were identified through the Swedish colorectal cancer registry. Data was retrieved from the Swedish colorectal cancer registry and chart review. Five-year survival and recurrence in colorectal cancer patients with previous diverticulitis were compared to sporadic cases, inflammatory bowel disease associated and hereditary colorectal cancer.

Results

The study cohort comprised 1052 patients, 28 (2.7%) with previous diverticulitis, 26 (2.5%) IBD, 4 (1.3%) hereditary syndromes and 984 (93.5%) sporadic cases. Patients with a history of acute complicated diverticulitis had a significantly lower 5-year survival rate (61.1%) and higher recurrence rate (38.9%) compared to sporadic cases (87.5% and 18.8% respectively).

Conclusion

Patients with acute complicated diverticulitis had worse 5-year prognosis compared to sporadic cases. The results emphasize the importance of early detection of colorectal cancer in patients with acute complicated diverticulitis.

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common form of cancer and the fourth leading cause of death related to cancer worldwide [Citation1–3]. In most CRC cases (75–80%), there is no identifiable underlying cause [Citation1–3], and the cancer is interpreted as sporadic. Approximately one out of five people with CRC has a genetic predisposition, the most widely known being Lynch syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) [Citation1–4]. Chronic inflammation has a well-known neoplastic effect which can lead to tumour development, for instance in patients suffering from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis [Citation2,Citation5–9]. Due to the increased risk of CRC, patients with IBD, Lynch syndrome and FAP undergo surveillance colonoscopies [Citation8–10].

Diverticulitis is another common inflammatory intestinal disease in the industrialized world [Citation11–13]. The acute form can be divided into either uncomplicated (AUD) or complicated diverticulitis (ACD), where the former is the most common presentation [Citation13]. The classification of ACD vs AUD is commonly made using the modified Hinchey classification by Wasavary et al. and sometimes by computed tomography (CT) findings by Kaiser et al. [Citation13,Citation14]. The different Hinchey stages modified by Wasavary et al. are defined as follows: 0 (Mild clinical diverticulitis, Ia (Confined pericolic inflammation or phlegmon), Ib (Pericolic or mesocolic abscess), II (Pelvic, distant intraabdominal, or retroperitoneal abscess), III (Generalized purulent peritonitis) and IV (Generalized faecal peritonitis) [Citation14].

After an episode of diverticulitis, guidelines recommend a follow-up colonic examination with either colonoscopy or CT-colonography with rigid sigmoidoscopy to rule out CRC [Citation15,Citation16]. It is unclear how a history of diverticulitis affects long-term outcomes after CRC [Citation12,Citation17–19].

The aim of this study was to study survival and recurrence rates in CRC patients with a history of diverticulitis and to compare outcomes with sporadic CRC, IBD and Lynch/FAP-associated CRC.

Material and methods

Patients ≤75 years of age diagnosed with a primary CRC diagnosis at Skåne University Hospital Malmö, Sweden, between January 1st 2012 and December 31st 2017 were identified through the Swedish Colorectal Cancer Registry (SCRCR). Inclusion criteria were stage I-III CRC and radical resection (<R0). Hence, patients with an unknown resection margin (R1 + R2) or no resection (laparotomy without resection, local excision, or transanal endoscopic microsurgery) were excluded.

SCRCR is a national mandatory registry covering 98.8% of CRC patients and with a variable agreement of 90% [Citation20]. Patient, tumour, and treatment characteristics were retrieved from the SCRCR. Medical charts were reviewed to establish if the CRC was sporadic or associated with previous diverticulitis, heredity or IBD, and to validate information about oncological outcomes such as date of death or recurrences. Cause of death was not documented why only overall survival and not cancer specific mortality was described.Furthermore, the medical charts were scrutinised for definition of previous diverticulitis as AUD or ACD confirmed by computed tomography (CT).

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were made using IBM SPSS version 28. Numerical data were reported as means with a 95% confidence interval (CI), while categorial numbers were presented as numbers and proportions in percentages. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse distribution of patient characteristics using Pearson’s Chi-square test for numbers with proportions and Fischer’s Exact test for comparisons with <5 patients in each cell. For means, One Way ANOVA was used. Post hoc analyses when appropriate. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to calculate and present survival. Level of significance was set to <0.05.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval was granted by the Swedish Ethical Review Authority (Dnr 2022-04832-01).

Results

Clinical characteristics

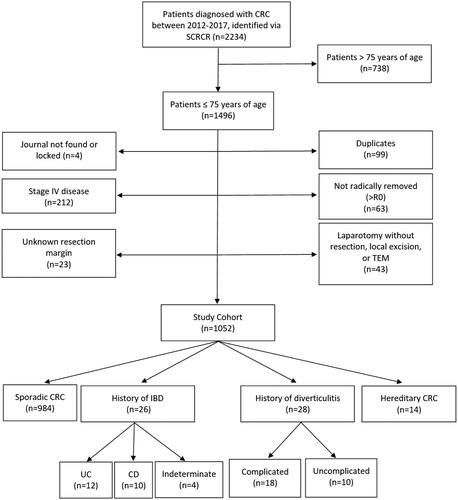

In total, 2234 patients diagnosed with CRC at Skåne University Hospital, Malmö, were identified through the SCRCR. In all, 1496 were ≤75 years of age (n = 1496) and eligible for the study. After exclusion according to predetermined criteria, 1052 patients constituted the study cohort (). Of these, 28 (2.7%) had a history of diverticulitis, 26 (2.5%) IBD and 14 (1.3%) Lynch or FAP. In 984 (93.5%) cases the CRC was considered sporadic.

Figure 1. Flow chart of the study cohort. CRC: Colorectal Cancer; TEM: Transanal Endoscopic Microsurgery; IBD: Inflammatory Bowel Disease; UC: Ulcerative Colitis; CD: Crohn’s Disease.

Mean age in the study cohort was 64.1 (63.5–64.6) years. The vast majority was between 50 and 75 years of age, only 86 (8.2%) were <50 years of age. presents patient, tumour, and treatment characteristics of the study cohort, with sporadic CRC, diverticulitis, IBD and hereditary CRC presented separately.

Table 1. Clinical characteristics of the study cohort.

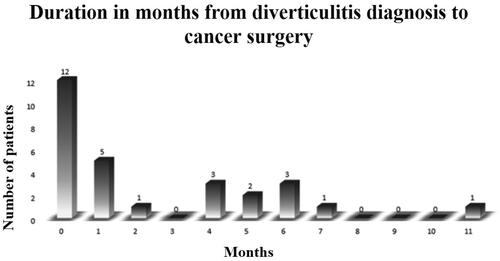

Among the 28 patients diagnosed with CT-verified diverticulitis, 18 (64.3%) had ACD and 10 (35.7%) had AUD ( and ). For diverticulitis patients, time from diverticulitis diagnosis to surgery varied between 0–11 months, and 12 (42.9%) had their cancer surgery either during the same hospital stay or less than a month from diverticulitis diagnosis (). Emergency surgery was performed in 36% of patients with a history of diverticulitis, compared to 10% among sporadic cases p < 0.001 (). Diverticulitis location was the sigmoid colon in 26 (92.9%) of the cases (). Among the CRC-patients with previous diverticulitis, 21 (75%) had sigmoid tumours. Two patients with previous diverticulitis (7.1%) had cancer located in the recto sigmoidal transition zone and were diagnosed as rectal cancers (data not shown).

Long-term outcomes

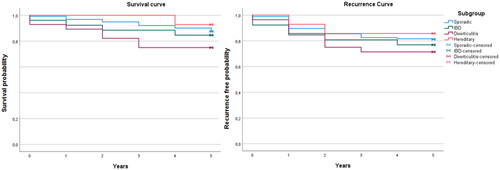

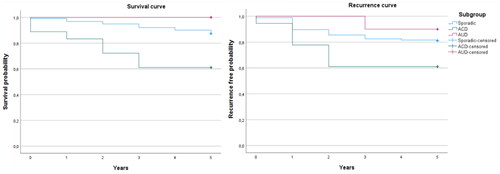

For the entire study population, the 5-year mortality rate was 135 (12.8%) and the recurrence rate was 96 (9.1%) with no significant differences between the four subgroups. However, patients with ACD had a higher mortality rate compared to sporadic cases of 7 (38.9%) (cumulative proportion (Cum-P) surviving: 0.61 (0.39–0.82)) vs 123 (12.5%) (Cum-P surviving: 0.85 (0.83–0.87)) among sporadic cases, (p = 0.002, Log rank <0.001) as well as a higher 5-year recurrence rate of 7 (38.9%) (Cum-P recurrence free: 0.61 (0.39–0.82)) vs 185 (18.8%) (Cum-P recurrence free: 0.81 (0.79–0.83)) (p = 0.032, Log rank = 0.047). These results are visualised in Kaplan Meier curves ( and ) and numbers are presented in and .

Figure 3. Outcome curves comparing 5-year survival and recurrence free patients between the 4 subgroups of CRC. IBD: Inflammatory bowel disease.

Figure 4. 5-year survival and recurrence free patients for the groups ACD and AUD compared to Sporadic cases of CRC. ACD: Acute Complicated Diverticulitis; AUD: Acute Uncomplicated Diverticulitis.

Table 2. Five-year oncological outcomes compared between the four subgroups.

Table 3. Five-year oncological outcomes in patients with ACD, AUD and sporadic CRC.

Discussion

This study showed a higher rate of recurrences and worse survival in patients with CRC and a history of ACD compared to patients with sporadic CRC.

Previous studies have suggested that delayed diagnosis in conjunction with risk of perforation with contamination of tumour cells and more frequent emergency surgery could contribute to the worse oncological outcome for ACD patients [Citation15,Citation21,Citation22]. An association between diverticulitis and CRC has been reported in several studies [Citation23–25], especially the link to interval cancers although more so in the proximal part of the colon [Citation26]. On the contrary, some studies show that there is no link between CRC and diverticulitis [Citation19,Citation27]. Azhar et al. pointed out that this discrepancy and possible association may represent misdiagnosis of CRC as ACD or AUD [Citation15]. Additional studies suggested similar conclusions [Citation12,Citation28]. In our study all diverticulitis patients developed CRC within one year after the diverticulitis episode and the majority demonstrated both diagnoses in the sigmoid colon. Further, these patients had a higher frequency of emergency surgery and ACD patients had a significantly poorer outcome than sporadic cases. This possibly indicates a high level of misdiagnosis of CRC as ACD during the first examination, resulting in a delayed diagnosis and thus a worse outcome. Besides in ACD, no impaired 5-year survival and recurrence rate were observed for the whole group of diverticulitis patients compared to sporadic cases which is consistent with previous research [Citation28].

For IBD patients, no significant difference could be detected for 5-year outcomes compared to sporadic cases [Citation29,Citation30]. However, the survival rate for CRC patients with IBD was 84.6% which is higher than historic studies reporting survival rates varying between 50–77% [Citation5,Citation10,Citation31]. For hereditary CRC, 5-year survival in our study was approximately 92.9% which correlates well with previous studies revealing 90% and 98% respectively in Lynch patients [Citation32,Citation33].

Limitations

This study has limitations, the first being its retrospective character which is associated with a higher risk of selection bias. As only patients admitted to hospital during the study period were included, patients with AUD may have been missed. Secondly, this study relied on accurate and consistent record keeping over many years and subsequently some missing data was recorded. Thirdly, this study is limited by sample size especially regarding subgroup analysis of diverticulitis and being a single center cohort. However, despite these restraints significant results were found.

Conclusion

In summary, patients with ACD had a significantly lower 5-year survival rate and a higher recurrence rate compared to sporadic cases. The results emphasize the importance of early detection of CRC in patients with ACD.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Fischer J, Walker LC, Robinson BA, et al. Clinical implications of the genetics of sporadic colorectal cancer. ANZ J Surg. 2019;89(10):1224–1229.

- Yamagishi H, Kuroda H, Imai Y, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of sporadic colorectal cancers. Chin J Cancer. 2016;35:4.

- Carr PR, Alwers E, Bienert S, et al. Lifestyle factors and risk of sporadic colorectal cancer by microsatellite instability status: a systematic review and meta-analyses. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(4):825–834.

- Medina Pabón MA, Babiker HM. A review of hereditary colorectal cancers. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Dyson JK, Rutter MD. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: what is the real magnitude of the risk? World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(29):3839–3848.

- Stidham RW, Higgins PDR. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2018;31(3):168–178.

- Bae SI, Kim YS. Colon cancer screening and surveillance in inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Endosc. 2014;47(6):509–515.

- Keller DS, Windsor A, Cohen R, et al. Colorectal cancer in inflammatory bowel disease: review of the evidence. Tech Coloproctol. 2019;23(1):3–13.

- Ekbom A, Helmick C, Zack M, et al. Increased risk of large-bowel cancer in crohn’s disease with colonic involvement. Lancet. 1990;336(8711):357–359.

- Rhodes JM, Campbell BJ. Inflammation and colorectal cancer: IBD-associated and sporadic cancer compared. Trends Mol Med. 2002;8(1):10–16.

- Hawkins AT, Wise PE, Chan T, et al. Diverticulitis: an update from the age old paradigm. Curr Probl Surg. 2020;57(10):100862.

- Wong ER, Idris F, Chong CF, et al. Diverticular disease and colorectal neoplasms: association between left sided diverticular disease with colorectal cancers and right sided with colonic polyps. Asian Pac J Cancer Prev. 2016;17(5):2401–2405.

- Welbourn HL, Hartley JE. Management of acute diverticulitis and its complications. Indian J Surg. 2014;76(6):429–435.

- Klarenbeek B, de Korte N, Peet D, et al. Review of current classifications for diverticular disease and a translation into clinical practice. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2012;27(2):207–214.

- Azhar N, Buchwald P, Ansari HZ, et al. Risk of colorectal cancer following CT-verified acute diverticulitis: a nationwide population-based cohort study. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(10):1406–1414.

- Schultz JK, Azhar N, Binda GA, et al. European society of coloproctology: guidelines for the management of diverticular disease of the Colon. Colorectal Dis. 2020;22(Suppl 2):5–28.

- Ekbom A. Is diverticular disease associated with colonic malignancy? Dig Dis. 2012;30(1):46–50.

- Viscido A, Ciccone F, Vernia F, et al. Association of colonic diverticula with colorectal adenomas and cancer. Medicina (Kaunas). 2021;57(2):108.

- Lam TJ, Meurs-Szojda MM, Gundlach L, et al. There is no increased risk for colorectal cancer and adenomas in patients with diverticulitis: a retrospective longitudinal study. Colorectal Dis. 2010;12(11):1122–1126.

- Moberger P, Sköldberg F, Birgisson H. Evaluation of the swedish colorectal cancer registry: an overview of completeness, timeliness, comparability and validity. Acta Oncol. 2018;57(12):1611–1621.

- Asano H, Kojima K, Ogino N, et al. Postoperative recurrence and risk factors of colorectal cancer perforation. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(3):419–424.

- Jörgren F, Lydrup ML, Buchwald P. Impact of rectal perforation on recurrence during rectal cancer surgery in a national population registry. Br J Surg. 2020;107(13):1818–1825.

- Mortensen LQ, Burcharth J, Andresen K, et al. An 18-Year nationwide cohort study on the association between diverticulitis and Colon cancer. Ann Surg. 2017;265(5):954–959.

- Meyer J, Buchs NC, Ris F. Risk of colorectal cancer in patients with diverticular disease. World J Clin Oncol. 2018;9(6):119–122.

- Choi YH, Koh SJ, Kim JW, et al. Do we need colonoscopy following acute diverticulitis detected on computed tomography to exclude colorectal malignancy? Dig Dis Sci. 2014;59(9):2236–2242.

- Singh S, Singh PP, Murad MH, et al. Prevalence, risk factors, and outcomes of interval colorectal cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109(9):1375–1389.

- Meurs-Szojda MM, Terhaar Sive Droste JS, Kuik DJ, et al. Diverticulosis and diverticulitis form no risk for polyps and colorectal neoplasia in 4,241 colonoscopies. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2008;23(10):979–984.

- Granlund J, Svensson T, Granath F, et al. Diverticular disease and the risk of Colon cancer - a population-based case-control study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2011;34(6):675–681.

- Reynolds IS, O’Toole A, Deasy J, et al. A meta-analysis of the clinicopathological characteristics and survival outcomes of inflammatory bowel disease associated colorectal cancer. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2017;32(4):443–451.

- Vitali F, Wein A, Rath T, et al. The outcome of patients with inflammatory bowel disease-associated colorectal cancer is not worse than that of patients with sporadic colorectal cancer-a matched-pair analysis of survival. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2022;37(2):381–391.

- Kiran RP, Khoury W, Church JM, et al. Colorectal cancer complicating inflammatory bowel disease: similarities and differences between crohn’s and ulcerative colitis based on three decades of experience. Ann Surg. 2010;252(2):330–335.

- Toh JWT, Hui N, Collins G, et al. Survival outcomes associated with lynch syndrome colorectal cancer and metachronous rate after subtotal/total versus segmental colectomy: meta-analysis. Surgery. 2022;172(5):1315–1322.

- Xu Y, Li C, Zheng CZ-L, et al. Comparison of long-term outcomes between lynch sydrome and sporadic colorectal cancer: a propensity score matching analysis. BMC Cancer. 2021;21(1):45.