Abstract

Purpose

The Swedish National Patient Register (SNPR) is frequently used in studies of colonic diverticular disease (DD). Despite this, the validity of the coding for this specific disease in the register has not been studied.

Methods

From SNPR, 650 admissions were randomly identified encoded with ICD 10, K572-K579. From the years 2002 and 2010, 323 and 327 patients respectively were included in the validation study. Patients were excluded prior to, or up to 2 years after a diagnosis with IBD, Celiac disease, IBS, all forms of colorectal cancer (primary and secondary), and anal cancer. Medical records were collected and data on clinical findings with assessments, X-ray examinations, endoscopies and laboratory results were reviewed. The basis of coding was compared with internationally accepted definitions for colonic diverticular disease. Positive predictive values (PPV) were calculated.

Results

The overall PPV for all diagnoses and both years was 95% (95% CI: 93–96). The PPV for the year 2010 was slightly higher 98% (95% CI: 95–99) than in the year 2002, 91% (95% CI: (87–94) which may be due to the increasing use of computed tomography (CT).

Conclusion

The validity of DD in SNPR is high, making the SNPR a good source for population-based studies on DD.

Introduction

Colonic diverticular disease (DD) is one of the most common gastrointestinal diseases. A diverticulum is caused by a herniation of the mucosa through the muscular layer at the place of penetration of vessels [Citation1,Citation2]. Inflammation is the most common complication and less than 5% of patients with diverticulosis develop diverticulitis [Citation3,Citation4]. Approximately 12% of patients with diverticulitis present with complicated disease [Citation5].

Typical clinical manifestations of acute diverticulitis are abdominal pain often localized to the left lower quadrant [Citation6], low-grade fever [Citation7] and usually elevated Leucocytes and C-reactive protein (CRP) [Citation6]. Seriously ill patients are treated in hospital, occasionally requiring antibiotics or emergency surgery [Citation8]. The most severe complications, such as perforation and peritonitis, are associated with a substantial risk of morbidity and mortality. Other significant manifestations of DD are bleeding, fistulae formation and stenosis leading to obstruction.

The Swedish National Patient Register (SNPR), lists all inpatient care in Sweden since the year 1987 [Citation9]. The diagnosis is reported to the register with clinical findings at the time of care. Although many ICD codes in SNPR have been shown to have very high validity (e.g., IBD), there is no such validation for the DD diagnosis. No study has addressed the reliability of the register in DD. The present study aims to assess the validity of the quality of registered ICD-codes of inpatients with diverticular disease in the Swedish National Patient Register.

Materials and methods

The Swedish National Patient Register

The SNPR contains information about inpatient care since 1964, nationwide since 1987 and with 99% coverage. The data was supplemented with the Swedish personal identity number from the period 1984–86 and onwards [Citation9,Citation10]. All hospitals in Sweden report to the register. The register contains information on dates of admissions, discharges, diagnosis and surgical procedures. The reliability of diagnoses in the SNPR varies but is generally regarded as high [Citation9,Citation10].

Patients

A representative random sample of admissions encoded with International Classification of Disease (ICD) 10 K572, K573, K574, K575, K578, and K579 () [Citation11], were randomly identified in SNPR. Half of the admissions were retrieved from year 2002 (n = 323) and half from 2010 (n = 327) respectively, in order to see if there were any differences in the validity of coding over time. There was an unequal distribution in a number of diagnoses for the three-digit codes of DD (K57, ICD-10) which was accounted for when we randomly selected patients to validate. For each of the more uncommon diagnosis (K574, K575, and K578) we aimed for at least ten patients randomly selected for each diagnosis in order to make an adequate validation. From the years 2002 and 2010, 16 (2.46%) and 17 (2.62%) out of 650 requested inpatient care episodes were validated.

For the more common diagnosis, K572, K573 and K579: 275 (42.3%) inpatient care patients, from the year 2002 and 276 (42.5%) inpatient care episodes from the year 2010 were randomly identified.

Exclusion

When applying for randomly identified patients with a primary discharge diagnosis of DD, K572-9 from the register, patients were excluded if prior to, or up to 2 years after diagnosis they received any of these diagnoses (as the main or co-diagnosis): Colitis (K52.0 – K52.9), Celiac disease (K90.0– K90.9), Irritable bowel syndrome (K58.0 and K58.9), Ulcerative colitis (UC) (K51.0– K51.9), Crohn’s disease (CD) (K50.0–K50.9), malignant tumor of the colon or rectum (C18.0–C20.9), malignant tumour in anus (C21.0 –C20.9), secondary malignant tumour of the colon and rectum C78.5, previous medical history of malignant tumour in the gastrointestinal tract (Z85.0), in situ cancer of the colon (D01.0) and in situ cancer of the rectosigmoidal border zone (D01.1).

Validation

To validate the primary diagnosis of DD, registered in SNPR, information from hospital records (clinical findings and assessments, X-ray and endoscopy examination reports, laboratory results, surgical reports, and hospital discharge summaries), were collected from the involved hospitals. Written letters were sent to all seventy Swedish hospitals to obtain medical records for each hospital visit. The data was then used to put a validation diagnosis in relation to internationally accepted classification for diverticular disease [Citation12,Citation13].

Every record was validated by one investigator MWM, author and several parameters were explored to assess if the registered ICD 10-code from the inpatient admission in the SNPR was correctly set or not. The presence of diverticular disease (DD) were confirmed by; A. computed tomography (CT) and/or x-ray of the colon with findings of diverticula and/or acute diverticulitis B. previously known DD. C. Findings of DD during endoscopy D. Signs of acute diverticulitis (defined as pain in the left lower abdominal pain, findings of elevated C-reactive protein (CRP) combined with lack of vomiting E. surgical findings and pathology report from surgery [Citation12,Citation14,Citation15].

Additionally, an internal validation was performed in 50 randomly selected inpatient visits, by an additional author (CH), unaware of the results of the primary assessment.

Statistics

Rational for sample size: In the years 2002 and 2010, approximately 8600 respectively 11,900 inpatient admissions were reported in Sweden coded with diverticular disease (K57) as the main or contributory-diagnostic listing. With a 95% confidence level (alpha = 0.05) and an assumption of 75% probability for a correct diagnosis, 286 admissions encoded with DD were warranted. PPV of the diagnosis was examined overall and over two periods, the years of 2002 and 2010 respectively. Therefore, 564 (282 × 2) admissions were needed to be validated to ensure enough power. To guarantee a sufficient number of complete patient files, medical records from 650 inpatient care visits were requisitioned from SNPR.

PPV was calculated for diverticular disease (two-digit coding, K57) and for each individual diagnostic code (three-digit coding) and subgroups with perforation and/or abscess (K572, K574, K578) or without perforation/abscess (K573, K575, K579) by comparing the ICD-10 code and the diagnosis determined from the patient file data. For each PPV, we estimated the corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CIs) using the method for binominal proportions.

Interobserver variation was calculated using Cohens Kappa statistics.

Results

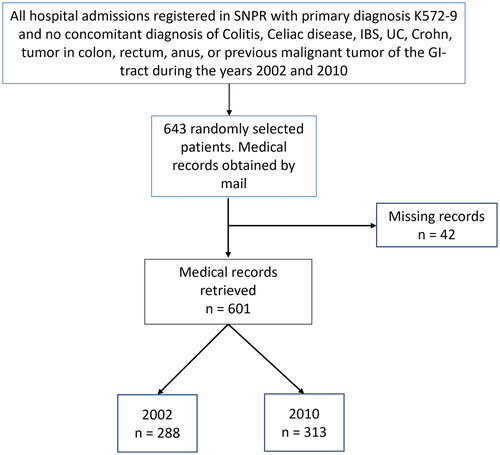

In all, data on 643 inpatients admissions were obtained from SNPR. Despite repeated communication and efforts to retrieve as many medical records as possible, 42 records were not able to be located. In total 601 records were obtained, 288 records from year 2002 and 313 records from year 2010 ().

Basic characteristics of the 601 patients showed no main differences in patient between 2002 and 2010 (), according to sex, age, type of hospital and department or rate of surgery (with and without pathology report). There were 65.4% women in the overall cohort Most of the patients were admitted to a surgical department (90.7%) and the rate of surgery rate was low as expected (). There were 20 patients that had the diagnosis based on only endoscopic examination.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of 601 patients with a diagnosis of diverticular disease (K57.2–K57.9) in the Swedish Patient Register in the years 2002 and 2010: distribution according to sex, age, type of hospital, department, rate of surgery, rate of surgery with pathology report and examinate with computed tomography (CT).

Distribution of complications or other manifestations of diverticular disease according to ICD 10 coding and findings during review of medical records are displayed in . The most common complications to DD are diverticulitis without abscess or perforation (55.2%).

Distribution of findings of DD according to diagnose coding and diagnostic modality are seen in . A high number of DD patients had abdominal pain (64.9%), in particular patients with abscess and/or perforation. The most common methods used to examine DD was computed tomography (CT) (47.1%) and colonoscopy (26.9%). There were 33 out of 601 patients that received the diagnosis based on clinical symptoms only. The clinical symptoms were based the criteria by Laméris (based on a combination of direct tenderness only in the left lower quadrant, the absence of vomiting, and an elevated C-reactive protein).

Table 2a. Distribution of complications or other manifestations of diverticular disease according to ICD 10 coding and findings during review of medical records by experienced surgeon.

Table 2b. Distribution of findings of DD according to ICD 10 and diagnostic modality (colonoscopy, CT, colon x ray), clinical diagnosis, surgical findings, or pathology report after surgery.

Positive Predictive values according to medical chart review

The total PPV in the cohort for all diagnoses and both years was as high as 95% (95% CI: 93–96). There was a difference in PPV between the year 2002, 91% (95% CI: 87–94) and 2010, 98% (95% CI: 95–99), . PPV for three-digit coding varies between years 2002, 78% (95% CI: 73–83) and 2010, 88% (95% CI: 84–92). The PPV in total for the three-digit ICD-code is 84% (95% CI: 80–87), .

Table 3. Positive Predictive values after validation of 601 patients with diagnos diverticular disease (K57.2–K57.9) in the Swedish Patient Register in the years 2002 and 2010.

The total PPV for the diagnosis K572 (Diverticulosis, diverticulitis coli with perforation and abscess) and K573 (Diverticulosis, diverticulitis coli without perforation or abscess) was 81% (95% CI: 72–88) vs 90% (95% CI: 86–93).

Internal validation

PPV for internal validation of 50 records was as high as 100%. Inter-observer agreement (Cohens Kappa) was 1.

Discussion

This study reports the validity for all diagnosis of diverticular disease (K572-K579) in the Swedish National Patient Register the years 2002 and 2010 to be high (PPV = 95%) for the two-digit coding (K57) and for three-digit coding, PPV varied between year 2002 (78%) and 2010 (88%).

Additionally, we found an overall higher PPV for the year 2010 compared with 2002. We believe that this is mainly due to the increasing use of computed tomography scan (CT) in the later period. CT was the most common diagnostic modality in the cohort during the year 2002, 30.2% of the patients underwent CT compared to 74.1% in year 2010 (). Of note, the ICD 10-codes K57 do not distinguish between diverticulosis and diverticulitis [Citation16]. It describes the presence of diverticula and its location with or without complications like perforation and abscess.

There are not many studies that have validated the diagnostic coding for DD. In a previous smaller Danish study with 100 patients [Citation17] on the diagnostic coding for diverticular disease (K57) the PPV for the overall diagnosis (K57) was 98% (95% CI: 93–99). For the more detailed subgroups that indicates the presence or absence of complications (K573–K579) the PPVs ranged from 67% (95% CI: 9- 99) to 92% (95% CI: 52–100). In the present study, a somewhat lower overall PPV 95% (95% CI: 93-96) were calculated compared to the Danish study. The range of the detailed subgroups that indicates the presence or absence of complications (K573–K579) was also somewhat lower trend was observed, the PPVs ranged from 45% (95% CI: 24 – 68) to 90% (95% CI: 86 – 93). However, as the confidence intervals overlap, no significant difference is found between the two studies. The current study verifies the results from the Danish study with a larger patient cohort.

Previous studies have examined the validity of several other diagnoses in the SNPR. A Swedish validation of the diagnosis of UC, CD, and IBD in the SNPR, revealed that the validity for those diagnosis is high in SNPR (PPV 93% for any IBD) [Citation18]. Likewise, another study validated IBD related surgical procedures and showed that in total, 158 surgical procedure codes were registered in SNPR. Of the validated codes there was a high concordant with the patient charts, corresponding to a PPV of 96.8% [Citation19]. These studies together with the present study support a high validity of diagnostic codes in SNPR.

A strength of the present study is the nationwide design, with random selection of a large number of patients. Another strength is the high retrieval rate of patient files from other hospitals.

Moreover, all medical records were retrospectively reviewed by an experienced GI- surgeon (MWM). Also, the internal blinded validation of 50 cases showed an PPV of 100% between the two surgeons’ assessments.

The patients were sampled from the SNPR including both regional hospitals and University Hospitals, regardless of disease severity and residence. The most common complications in the present report are diverticulitis, 68% (410 of 610). Most of them had uncomplicated diverticulitis but 35% of them (146 of 410) had complicated diverticulitis.

The present study included only hospital-treated patients and not outpatients diagnosed in primary care, therefore, the proportion of uncomplicated diverticulitis should maybe be higher than described in this study. Furthermore, the rather high proportion of patients with perforation in this study displays that the whole study population was treated as inpatients. Patients with milder symptoms are most likely treated in primary care to a higher extent.

Our diagnostic criteria for patients who have not been investigated radiologically or endoscopically were the same as those by Laméris et al. [Citation13], which reduces the risk of misclassification.

There are some limitations with the study, the study period is at least a decade old, reviewing cohorts of 2002 and 2010, and the process of diagnosis may have changed since then. However, if something has changed, most probably, the validity may have further improved. Another limitation is that the missing records were unevenly distributed between 2002 and 2010. Thus 35 of the 42 missing records were from 2002 and only 7 records from 2010 which may have affected the result of 2002 more than 2010.

In conclusion, our study shows that the ICD-10 K572-9 codes has high validity in the Swedish National Patient Register and can, with a high degree of validity, be used to identify diverticular disease.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Karolinska Institutet (2010/1111-31/2) and (2013/603-32).

Acknowledgments

No acknowledgements.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Walker MM, Harris AK. Pathogenesis of diverticulosis and diverticular disease. Minerva Gastroenterol Dietol. 2017;63(2):99–109. doi: 10.23736/S1121-421X.16.02360-6.

- Wan D, Krisko T. Diverticulosis, diverticulitis, and diverticular bleeding. Clin Geriatr Med. 2021;37(1):141–154. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2020.08.011.

- Shahedi K, Fuller G, Bolus R, et al. Long-term risk of acute diverticulitis among patients with incidental diverticulosis found during colonoscopy. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;11(12):1609–1613. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.020.

- Strate LL, Morris AM. Epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment of diverticulitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(5):1282–1298.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2018.12.033.

- Kaiser AM, Jiang J-K, Lake JP, et al. The management of complicated diverticulitis and the role of computed tomography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2005;100(4):910–917. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2005.41154.x.

- Swanson SM, Strate LL. Acute colonic diverticulitis. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(9):Itc65–itc80. doi: 10.7326/AITC201805010.

- Jacobs DO. Clinical practice. Diverticulitis. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(20):2057–2066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp073228.

- Chabok A, Påhlman L, Hjern F, et al. Randomized clinical trial of antibiotics in acute uncomplicated diverticulitis. Br J Surg. 2012;99(4):532–539. doi: 10.1002/bjs.8688.

- Ludvigsson JF, Andersson E, Ekbom A, et al. External review and validation of the swedish national inpatient register. BMC Public Health. 2011;11(1):450. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-450.

- www.socialstyrelsen.se.

- https://icd.codes/.

- Laméris W, van Randen A, van Gulik TM, et al. A clinical decision rule to establish the diagnosis of acute diverticulitis at the emergency department. Dis Colon Rectum. 2010;53(6):896–904. doi: 10.1007/DCR.0b013e3181d98d86.

- Lauscher JC, Lock JF, Aschenbrenner K, et al. Validation of the german classification of diverticular disease (VADIS)-a prospective bicentric observational study. Int J Colorectal Dis. 2021;36(1):103–115. doi: 10.1007/s00384-020-03721-9.

- Feuerstein JD, Falchuk KR. Diverticulosis and diverticulitis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2016;91(8):1094–1104. doi: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2016.03.012.

- Peery AF, Shaukat A, Strate LL. AGA clinical practice update on medical management of colonic diverticulitis: expert review. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(3):906–911.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2020.09.059.

- Cirocchi R, Popivanov G, Corsi A, et al. The trends of complicated acute colonic Diverticulitis-A systematic review of the national administrative databases. Medicina. 2019;55(11):744. doi: 10.3390/medicina55110744.

- Erichsen R, Strate L, Sørensen HT, et al. Positive predictive values of the international classification of disease, 10th edition diagnoses codes for diverticular disease in the danish national registry of patients. Clin Exp Gastroenterol. 2010;3:139–142. doi: 10.2147/CEG.S13293.

- Jakobsson GL, Sternegård E, Olén O, et al. Validating inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) in the Swedish National Patient register and the Swedish Quality Register for IBD (SWIBREG). Scand J Gastroenterol. 2017;52(2):216–221. doi: 10.1080/00365521.2016.1246605.

- Forss A, Myrelid P, Olén O, et al. Validating surgical procedure codes for inflammatory bowel disease in the swedish national patient register. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2019;19(1):217. doi: 10.1186/s12911-019-0948-z.