ABSTRACT

We examined the Supreme Court’s workplace and educational gender-discrimination cases from the 1970s to the present, assessing how they discuss women, their status, and workplace and educational experiences. Our study is situated in scholarship on status hierarchies, gendered cultural frameworks, and sociolegal understandings of the role of justice ideology and social movement influences on court decision making. We used a novel method for assessing court opinions, a combination of computerized text and qualitative analysis, to distill distinct vocabulary and meanings articulated in opinions decided in favor of and against the original female plaintiffs. We found pronounced differences in the court’s discourse, with women centered in pro-plaintiff opinions, where decisions rely on an egalitarian gender framework, and decentered in pro-opponent opinions that draw on a traditional framework. These gender ideological frameworks remain largely stable over time, albeit with some changes, revealing an ongoing discursive struggle over women’s status in the court.

Scholars in recent years have explored the lack of feminist language in U.S. Supreme Court opinions (Neumeister Citation2017). Some have also investigated how a range of court decisions grappling with gender inequality might be different if written from a perspective where women’s experiences and the harms of gender inequality and inequity were given more serious attention (Stanchi, Berger, and Crawford Citation2016). Our research adds to this important conversation by focusing on how the court, in the written language of its opinions, discusses women and how it responds to women’s claims of discrimination. The Supreme Court, as an elite institution defining law, helps shape broad cultural views by articulating and legitimating understandings of women, their legal rights, and their status in societal institutions. Given its importance, we assessed the court’s discourse as it socially constructs women and their experiences through an examination of workplace and educational gender-discrimination cases since the early 1970s.

To discern how the Supreme Court considers women, we focused on the court’s discussions of women generally, the specific female litigants, and the possible harms experienced by women. Comparing the justices’ opinions in favor of the original female plaintiffs and those in favor of their opponents, we discerned the distinct language in these two types of judgments. Our methodological approach used a novel combination of computerized word-embeddings and nearest-neighbors analysis and qualitative analysis. The computerized method revealed use of distinct words by the two sides. The qualitative analysis then relied on this distinct vocabulary to explore meaning making using the distinct words. This approach allowed us to see an ongoing discursive struggle in the court’s opinions, between two differing views of women and their status in workplaces and educational institutions, specifically, egalitarian and traditional views. Ours was not, then, an analysis of legal doctrine, concepts, and precedent but rather of the court’s articulation of its understanding of women, their status, and their experiences with discrimination.

We bring into conversation several scholarly literatures, including sociological conceptions of status and gender hierarchies, empirical studies of gender bias on the Supreme Court, feminist theorizing of differing gender cultural frameworks, and sociolegal research on the role ideologies play in judicial reasoning and possible social movement influence as a force of change in elite institutions (Chamallas Citation2013; Eskridge Citation2001; Patton and Smith Citation2017; Ridgeway Citation2019). We also add to the extensive literature in sociology that considers workplace and educational gender discrimination (Wynn and Correll Citation2018). While our systematic examination of 50 years of court opinions uncovered competing gendered cultural frameworks, both egalitarian and traditional views, we found the court’s discourse rarely, if ever, ventures beyond these frameworks to engage with a rich array of feminist theoretical views exploring more complex understandings of women’s experiences with discrimination and law.Footnote1

CONCEPTUAL ANCHORS

Recent studies in political science reveal gender bias at the level of the Supreme Court. Patton and Smith (Citation2017) documented that conservative justices during oral arguments interrupt female lawyers more than male lawyers. Jacobi and Schweers (Citation2017) showed that male justices interrupt their female colleagues on the bench more than their male colleagues. Szmer, Sarver, and Kaheny’s (Citation2010) analysis revealed that, during oral arguments, female attorneys have difficulty convincing conservative justices, unless the case involves a “women’s issue.” While evidence of the court’s gender bias is growing, our survey of the literature shows that the court’s discourse, contained in the written text of its opinions, has not been a focus of these recent investigations. On the other hand, feminist legal scholars (Brake Citation2008; Pino Citation2018) provide detailed consideration of the court’s opinions, often centered on close readings of one or a few rulings. These appraisals reveal significant shortcomings in the court’s treatment of women. As we explore below, feminist legal scholars demonstrate myriad ways in which the justices’ statements can perpetuate gender stereotypes or provide limited understandings of discrimination, inequality, and inequity and their harms.

The Supreme Court, as the highest U.S. judicial authority, exercises substantial power in its legal decision making, articulating opinions that can promote equality and equity for women, or reinforce hurdles and differential treatment that maintain male status primacy and power. Not only does the court’s discourse fundamentally shape law, but it can impact societal culture more broadly, through what Smart (Citation1989:4) referred to as law’s “power to define” culture, beliefs, and ideas, through portrayals of women and understandings of what qualifies as unfair workplace and educational treatment. As scholars (e.g., Dahl Citation1957) have long asserted, the court’s “power to define” works largely through legitimacy, that is, the court’s ability to “create acceptance of policy among those who oppose or are neutral about its substance and heighten acceptance among those already committed to its content” (Adamany Citation1973:802). While the court’s capacity to shift broader culture is not absolute, Ura and Higgins Merrill (Citation2017) reported that empirical research suggests the reach of the court’s influence on societal culture.

The Supreme Court plays an important cultural role in society. Sociologists, however, infrequently focus on the court rulings as a site of study (for important exceptions, see Brewer and Heitzeg Citation2008; Lee Citation2021). We situated our study in sociological theorizing of status beliefs and egalitarian and traditional gender ideologies. As Ridgeway (Citation2019:70) told us, status beliefs are “a form of cultural ‘common knowledge’” that “allow actors to coordinate their status-related judgments of ‘value.’” Status, according to Ridgeway (Citation2019:1), is “the social esteem, honor, and respect” we assign to individuals and groups. Substantial scholarship tracks individual-level egalitarian and traditional gender ideologies (Scarborough, Sin, and Risman Citation2019). Sociologists (Crossley Citation2017; Kalev and Deutsch Citation2018; Wynn and Correll Citation2018) provide rich literature on workplace and educational gender inequalities. Bringing Supreme Court opinions, with their power to shape cultural beliefs, into this inequality scholarship is a less common step (although see, for instance, Edelman Citation2016; Saguy, Williams, and Rees Citation2020).

Scholars (Broverman et al. Citation1972; Ridgeway Citation2011) have long studied cultural understandings of women and women’s status in society. The “separate spheres” idea is a common theme in these discussions, that is, the traditional belief that women’s appropriate role is in the domestic sphere, rearing children and managing households, while men’s place is in arenas of paid work and politics. Separate spheres thinking underpins traditional gendered assumptions that, while men are legitimate actors in workplaces and education, this is less true for women (Acker Citation1990). While many demonstrate the limits of the actual practice of separate spheres, particularly for working-class women and women of color who historically have participated heavily in workplace settings (Warren Citation2007), the separate-spheres cultural belief continues to have potency through the period we examined, in workplaces, educational settings, and the law (Berggren Citation2008; DeWelde and Stepnick Citation2014; Williams Citation2000), and, as we show, in the court’s discourse. As legal scholars (Harris and Sen Citation2019) explained, such gendered political ideologies can play a substantial role in shaping judicial decision making.

Sociolegal scholarship (Eskridge Citation2001; Siegel Citation2006), however, recognizes that the judiciary can embrace ideas articulated by social movements, including the women’s movement. Investigation of the movement against workplace pregnancy discrimination reveals instances when the court accepted feminist movement norms (Dinner Citation2010). When the Court echoes claims made by social movements espousing more egalitarian frameworks, we see evidence that movement ideation can flow into the court’s discourse and its opinions can elevate women’s status by recognizing the harms gender discrimination imposes on women and articulating instead a gender equality framework.

We studied the court’s discourse in its workplace and educational gender opinions to add to these various literatures, showing two ways the court understands women and their experiences with discrimination. We find egalitarian and traditional gender ideologies in the court’s discourse. When the Supreme Court articulates an egalitarian view of women as full-status actors, recognizing women in workplaces and educational institutions as participants meriting equal treatment relative to men and acknowledging harm to women resulting from discriminatory practices, the court challenges a broader, longstanding cultural system of male privilege, where women’s injuries are often unnoticed (Wildman, Forell, and Matthews Citation2000). With this view, the court is critical of the disadvantages confronted by women. A defining feature of this view, we find, is that it centers women and their experiences with discrimination, including the injuries they encounter.

When the Court, instead, does not validate women’s status as equals or deserving of equal or equitable treatment and fails to acknowledge harm to women due to unjust treatment, even when indications of discrimination’s harms exist, the court reinforces a traditional belief system in which women and their experiences are undervalued and not given the same attention as those of men. This view reasserts a hierarchical and patriarchal gendered status order (Berrey, Nelson, and Nielsen Citation2017). A defining trait, we find, in the traditional framework is that it decenters women, typically not recognizing and often erasing the harm women confront when experiencing discrimination, even when injuries are evident in the case. Instead, the court turns to other emphases, elevating organizational practices or male workers.

Feminist legal scholarship provides a rich and varied set of theoretical perspectives to understand how law can disadvantage women (Chamallas Citation2013; West and Bowman Citation2019). Liberal-equality feminism, epitomized by Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s strategic efforts in litigation to win equal protection rights for women, elevates the importance of equal legal treatment for women relative to men. This egalitarian framework, our analysis shows, often appears in the justices’ discourse when decisions favor female plaintiffs, with assertions of the justness of equal treatment of women in workplace and educational settings. Yet, other feminist frameworks, relational feminism (emphasizing human connection and caring and calling for workplace law that, for instance, recognizes and values the needs of pregnant workers and those caring for dependents), intersectional feminism (identifying intersecting oppressions, not only sexism, but racism, classism, heteronormativity, and xenophobia, to name just some), and postmodern feminism (helping us replace the gender binary with a fluid and inclusive understanding of gender as a broad continuum) remain virtually absent in the cases we study, as we will show. In the pregnancy cases, in particular, we often find explicit resistance to a relational-feminist approach of addressing gender inequities by recognizing that for women “disadvantage [comes] from identical treatment” to men (Chamallas Citation2013:55). In the end, our analysis uncovers, for the most part, only two basic types of gender ideation in the court’s discourse, a finding revealing the limits of the court’s conceptualizations of women.

DATA AND METHODS

We used computerized-text analysis and qualitative examination of the Supreme Court’s majority and concurring opinions for workplace and educational gender-discrimination cases. Combining the computerized and qualitative approaches allowed us to accomplish two steps. First, our computerized analysis systematically distilled the distinct vocabulary characterizing cases decided in favor of the female plaintiffs and those in favor of their opponents, as these opinions discuss women. Second, our qualitative investigation then used this distinct vocabulary to explore meanings associated with the words by examining the discussions in the opinions where the vocabulary resides. One might envision our method overall by imagining a Venn diagram, with our focus on the words in the diagram’s nonoverlapping portions.

We included in our analysis all the workplace and educational gender discrimination cases decided by the Supreme Court from 1965 to 2022 with a few exceptions, with cases spanning 1974 to 2015.Footnote2 The cases were of three types: a) exclusion of women from jobs, positions as students, and workplace promotions (our barriers cases); b) workplace wages-and-benefits inequality between women and men; and c) unfair treatment of pregnant workers (Lens Citation2004). In most of the legal cases, opponents were educational institutions or employers. In the 25 cases in our analysis, eight were barriers, eight wages-and-benefits, and nine pregnancy-discrimination cases (see ). These make up all the Supreme Court cases with female plaintiffs for the three types of cases we consider. Most of our cases (23) were workplace cases; two were educational decisions.Footnote3

Table 1. Workplace and Education Discrimination Cases Involving Female Plaintiffs by Case and Opinion Type, 1965–2020a

We included the majority and concurring opinions (both offer the court’s rationales for its decisions) but not dissenting opinions or opinions involving both concurrence and dissent, given that dissents can and typically do contain different rhetoric and often target different audiences than majority and concurring opinions (Gibson Citation2006; Sharp Citation2013).Footnote4

In examining the legal texts, we focused on specific portions of the court’s opinions, in two ways. First, we examined the segment of the opinion where the justices developed their reasoning in the case, which was our focus. We excluded from our analysis discussions in the opinions’ front ends where the justices review the history of the case, lower court decisions, and litigant arguments. In most decisions, it was straightforward to locate the point where the court began articulating its reasoning. In some opinions, portions of the text were mixed; that is, the discussion contained both a position taken by a litigant and the court’s response to it. In such instances, we included these mixed discussions in our analysis because they contain the court’s reasoning.

Second, we analyzed the court’s wording around the word “women” and other wording the court uses to reference women, including “woman,” “plaintiff,” “appellees” or “petitioners” (for cases where original plaintiffs are appellees or petitioners), plaintiff proper names, etc., given our interest in learning how the court understands women in its opinions. The word “women” (and all its referents) then was our target word, that is, the word for which we examined the words and meanings around it.

In the computerized portion of our investigation, we used word-embeddings and nearest-neighbors analysis (WE/NN) (Rodriguez, Spirling, and Stewart Citation2023). We began by computing word embeddings that are mathematical representations of words. These embeddings are estimated such that words with similar meaning in language will have similar numerical representations. We constructed both general and context-specific word embeddings, which we then used in our computation of the nearest-neighbors vocabulary. The general word-embedding estimates used machine learning algorithms, in our case, GloVe, and a large corpus of over 30,000 Supreme Court opinions (Fiddler Citation2021; Pennington, Socher, and Manning Citation2014). GloVe discerned the global meaning of words, by associating words frequently found near each other across the thousands of court opinions, and then computed a general word-embedding measure for each word found in these opinions (Pennington et al. Citation2014). We used this GloVe step to generate standard legal meanings for our analysis.

Following Rodriguez and colleagues (Citation2023), we estimated context-specific word embeddings for our target word, “women” (and its synonyms); that is, these word embeddings were estimated using the local word context for “women” within the court opinions in our analysis. The local context in which a target word appears, defined as the words nearby the target word in a text of interest, can change the meaning of that word. We built a context-specific word embedding for any single instance of our target word by averaging the GloVe pre-trained embeddings for each word in the local context of the instance of “women” (Khodak et al. Citation2018; Rodriguez et al. Citation2023).

To estimate the context-specific word embeddings, we located all references to “women” in the opinions. We also located the words adjacent to each instance of “women,” which defined the context-specific word-embedding window for each reference to “women.” Given that windows between sizes five and ten words tend to capture more topical and semantic information about target words (Levy and Goldberg Citation2014), we selected the eight words on either side of each reference to “women” to define the context window. A context-specific word embedding was then estimated by a linear combination and transformation of the 16 word embeddings in the context window (Khodak et al. Citation2018).

We compared the wording around “women” in cases decided in favor of female plaintiffs and those decided for their opponents, doing this separately for the barriers, wages-and-benefits, and pregnancy cases.Footnote5 We averaged all single-instance embeddings of “women” to create two word-embeddings for “women” for each case type, one representing references to “women” in decisions supporting women and one representing references in decisions supporting their opponents.

We then computed the nearest neighbors to each of these word embeddings. The nearest neighbors are the words characterizing the way the court discusses women in each of the two opinion types (pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent). We found these nearest neighbors by computing the cosine similarity between the GloVe embeddings for each word appearing in our local word-window contexts and each average embedding for “women.” Cosine similarity represented the distance between two word embeddings, with smaller distances indicating that the words have similar meanings or are used in similar contexts. For example, if the word “stereotyping” appeared in barriers cases decided in favor of women, we computed the cosine similarity between the GloVe embedding for “stereotyping” and both the pro-plaintiff embedding and the pro-opponent embedding for “women” for the barriers cases. Using these two values, we calculated the cosine similarity ratio. If the cosine similarity ratio was significantly smaller than one, we said that the meaning or use of “stereotyping” was more similar to the court’s characterization of women in the pro-plaintiff than the pro-opponent barriers cases (Rodriguez et al. Citation2023). Similarly, if the ratio was significantly greater than one for another word, the word use aligned better with the pro-opponent discussion.

Our figures (in the results discussion below) show statistically significant, distinct nearest neighbors for the embeddings of references to women in our pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent decisions. In the figures, we provide separate graphs for the barriers, wages-and-benefits, and pregnancy cases. The x-axes represent the cosine similarity ratio for the distinct words. Words are arranged in order of their cosine similarity. Those near the bottom of the graph are more distinct to the vocabulary of opinions in favor of female plaintiffs (left-hand side) or that of opinions in favor of their opponents (right-hand side). While there is some “noise” in these figures, that is, words that do not contribute to our overall interpretation (see Part II of the Appendix for a discussion of these), a pattern in the distinct wording of differing gendered views emerges.

As we present our computerized results in graph form, we also return to the legal opinions themselves, placing the distinct pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent vocabularies back in their textual contexts. We read these passages in the opinions closely and provide a detailed discussion of the meanings conveyed by these distinct words. That is, we discuss how women and their experiences in workplaces and educational settings are discussed in these passages. From this we distill the differing gendered views in the pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent opinions.

RESULTS

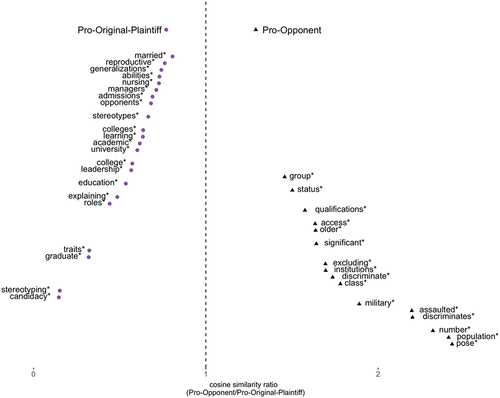

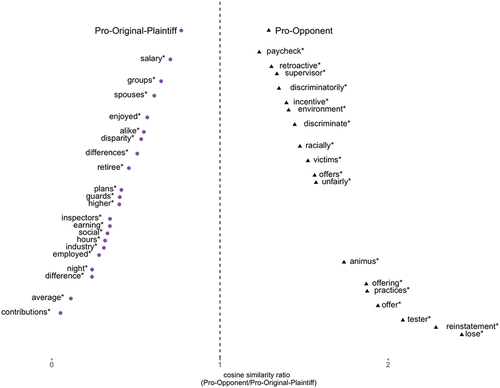

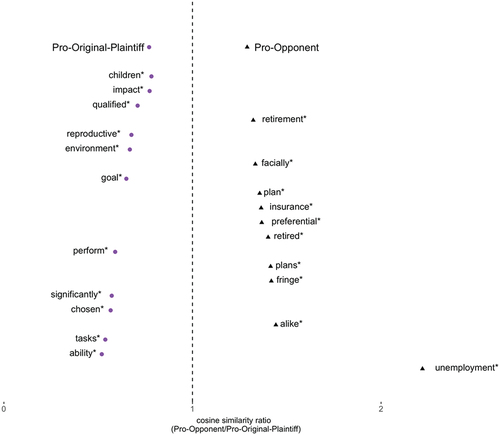

lists the three types of Supreme Court decisions we considered: barriers, wages-and-benefits, and pregnancy. Cases are listed for each type along with decision years, with pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent decisions in separate rows. The different vocabularies for opinions favoring women and those favoring their opponents appear in . For each type of case in our discussion below, we begin with the results from the WE/NN analysis and then turn to the qualitative findings.

Figure 1. Distinct Language Characterizing “Women” in Pro-Original-Plaintiff vs. Pro-Opponent Barriers Opinions

Figure 2. Distinct Language Characterizing “Women” in Pro-Original-Plaintiff vs. Pro-Opponent Wages- and Benefits Opinions

Figure 3. Distinct Language Characterizing “Women” in Pro-Original-Plaintiff vs. Pro-Opponent Pregnancy Opinions

Barriers in Workplaces and Education

The Supreme Court barriers cases consider hurdles confronting women as they attempt to enter higher education and workplaces and attain employment promotions. The right-hand side of portrays the results of our WE/NN analysis showing the distinct justice vocabulary in cases not decided in favor of the women. The results reveal that these Supreme Court opinions, significantly more so than those decided in favor of women, embed discussions of women in language referring to the barriers themselves, using the words “class,” “excluding,” “access,” “qualifications,” “status,” and “group.” Words such as “class,” “status,” and “group” point to the distinctions and groupings that workplace policies creating barriers generate. For instance, in Personnel Administrator of Massachusetts v. Feeney (442 U.S. 256 [1979]; see Appendix Part I for all case citations) when Massachusetts gives preference to veterans in hiring, the policy constructs nonveteran and veteran “classes,” groups that reside on either side of the barrier. The Feeney justices ruled in favor of a Massachusetts policy giving preference to veterans in state hiring, when women’s entry into the military was strictly limited. Women then have difficulty traversing the preference barrier because the preferred group in hiring—veterans—contains few women (Feeney 1979).

Not only is there a focus on the distinctions and groupings in the pro-opponent barriers opinions, but we also find that often in its discourse, as the court acknowledges the existing barrier, it then accepts the gender inequality, stating, for example, “[t]o the extent that the status of veteran is one that few women have been enabled to achieve, every hiring preference for veterans, however, modest or extreme, is inherently gender-biased” (Feeney 1979:276–77). The Feeney majority then states, “the history of discrimination against women in the military is not on trial” (p. 278). Gender bias is a result, but the court’s opinion only recognizes it and does not challenge it. In fact, use of the distinct word “military” in stems from Feeney discussions of women where the court accepts discrimination against women in the military. While the word “military” itself does not connote this acceptance, in its Feeney word contexts, the court uses the word in statements where there is no resistance to the barrier imposed by the Massachusetts law; it is simply accepted.

Elsewhere in these pro-opponent opinions, the discussions of women take a further step and explicitly defend gender barriers, with statements along the lines of, a “neutral law that casts a greater burden upon women as a group than upon men as a group” contains a preference for men and “the goals of the preference hav[e] been found worthy” by past court rulings (Feeney 1979:277–78). Here, the defense of the barrier is legal precedent. Discussions in Dothard v. Rawlinson (433 U.S. 321 [1977]) provide another example of the court defending a barrier, specifically Regulation 204 (a bona fide occupational qualification [BFOQ]) instituted by the Alabama Board of Corrections, which held that women cannot serve as prison guards in maximum-security male prisons. The court’s rationale is that “inmates deprived of a normal heterosexual environment, would assault women guards because they were women” and “there is a basis in fact for expecting that sex offenders who have criminally assaulted women in the past would be moved to do again if access to women were established within the prison” (Dothard 1977:335; using distinct word “assaulted”).

In defining the prison space as dangerous to women, the court declares that the danger stems from the guards’ own “womanhood” (p. 335). As Powers (Citation1979:1294) pointed out, this conceptualization of the female prison guard portrays her as “an unwitting seductress,” whose presence the opinion emphasizes, will “pose a real threat … to the basic control of the penitentiary” (Dothard 1977:336; the word “pose” in is used in this same way numerous times. The court’s stereotyping of women as sexual object entails an assumption that female prison guards are unable to maintain order and are not capable and competent prison employees. Here, importantly, in defending the barrier, the court presents an image of women that undermines women’s status as capable workers.

Not only does the woman’s womanhood put her in danger, but the dominant concern in the court’s upholding of Regulation 204 is maintaining order in the prison. The court states, “[t]he employee’s very womanhood would thus directly undermine her capacity to provide security that is the essence of a correctional counselor’s responsibility” (Dothard 1977:336). The judicial emphasis is on prison “institutions,” another distinct word in , and possible harm to these organizations.

Importantly, the emphasis is not on women’s experiences of exclusion from the prison jobs, employment known to pay well, offer benefits, and provide an economically secure future (Thomas Citation2016). Rather, the justices focus on harm to the prison. The court ignores evidence presented by the plaintiff that prison-guard training and use of methods to diffuse conflict are more important than gender or strength in maintaining order in correctional facilities (Thomas Citation2016). Likewise, in Feeney, as stated, “discrimination against women in the military is not on trial in this case” (Feeney 1979:278; the word “number,” also in the graph, is used similarly, to assert, for instance, that while a large “number” of women are excluded, the policy itself is neutral regarding gender). The court defines the root cause of Helen Feeney’s complaint—exclusion from public-sector employment—as beyond the purview of the case, rendering the consequence for the plaintiff irrelevant. This decentering of women’s experience of workplace exclusion diminishes the status of women as workers, by erasing their injury. We acknowledge, however, that Dothard and Feeney are both early cases. Among the barriers cases going forward, female plaintiffs have won at the level of the Supreme Court (see ). Furthermore, as we will see in discussions of later, wages-and-benefits and pregnancy cases, references to the incompetent female worker recede.Footnote6

We turn now to the left-hand portion of for barriers opinions decided in favor of women, which shows that as the court references “women,” its language is significantly more likely to utilize the words “stereotyping,” “stereotypes,” and the “traits,” “roles,” “abilities,” and “generalizations” involved in such stereotyping. Our examination of the meaning of these words in their contexts reveals discussions critical of invoking traditional beliefs about women in employment or educational settings, discussions that are particularly prominent in two of the later pro-plaintiff barriers cases: Price Waterhouse v. Hopkins (490 U.S. 228 [1989]), a case in which a woman was not promoted to partner in an accounting firm because the senior partners relied on gender stereotypes in their evaluation of her for promotion, and United States v. Virginia (518 U.S. 515 [1996]), a case challenging women’s exclusion from the state-funded Virginia Military Institute.

Price Waterhouse and Virginia develop detailed refutations of use of gender stereotypes to deny women equality in the workplace. In these opinions, we see the influence of second-wave liberal feminism and denouncements of classifying individuals, based on their biological sex, as capable or incapable workers or students. In Price Waterhouse, the court cites Title VII to rule that “[i]n the specific context of sex stereotyping, an employer who acts on the basis of a belief that a woman cannot be aggressive, or that she must not be, has acted on the basis of gender” and “gender must be irrelevant to employment decisions” (Price Waterhouse 1989:250, 240). Such statements illustrate egalitarian feminism, that women and men should be treated equally, and use of traditional stereotypes promote unequal treatment. The court gives attention to women’s experiences with discrimination, revealing its understanding of the complex situations women can find themselves in when gender stereotypes are used against them. The court remarks that “[a]n employer who objects to aggressiveness in women but whose positions require this trait places women in an intolerable and impermissible catch 22: out of a job if they behave aggressively and out of a job if they do not” (Price Waterhouse 1989:251). This double bind, the court concludes, excluded the plaintiff, Ann Hopkins, from promotion.Footnote7

The distinct vocabulary in these later pro-plaintiff opinions draws on words such as “generalizations” and “stereotypes” to challenge the very kinds of traditional views expressed in the pro-opponent opinions. The court in Virginia asserts that “the United States [as plaintiff] emphasizes that time and again since this Court’s turning point decision in Reed v. Reed … we have cautioned reviewing courts to take a ‘hard look’ at generalizations or ‘tendencies’ of the kind pressed by Virginia … . State actors controlling gates to opportunity, we have instructed, may not exclude qualified individuals based on ‘fixed notions concerning the roles and abilities of males and females’” (Virginia 1996:541).Footnote8 In both Price Waterhouse and Virginia, the court pushes back against gender stereotypes, working to dismantle discriminatory practices by pointing out that these outmoded beliefs undermine women’s status, limit their access to workplaces and educational institutions, and produce unequal and unfair treatment.

In Price Waterhouse and Virginia, the justices center their discussions of women on women’s experiences with discrimination, including the harms these experiences pose. Price Waterhouse focuses on Ann Hopkins’ denied partnership. In Virginia, the court points to missed opportunities experienced by women not able to receive “leadership” training or to “graduate with the advantage of a VMI [Virginia Military Institute] degree” (Virginia 1996:552; using distinct words “leadership” and “graduate”). In Virginia, the justices go on to say, “[h]er diploma does not unite her with the legions of VMI graduates who have distinguished themselves in military and civilian life” (p. 552) or of “all the opportunities and advantages withheld from women who want a VMI education” (p. 555; using word “education”). The decisions’ distinct vocabulary does not erase the injuries experienced by women but rather elevates them.

In Virginia, Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg, author of the majority opinion, takes the logic of challenging stereotypes in law a step further, introducing what Gibson (Citation2006:141) refers to as a “more complex understanding of women.” In describing women’s capacity to succeed at VMI, Ginsburg stresses that some women are fully capable of succeeding in the institute’s rigorous leadership training program. Ginsburg states,

’some women … do well under [the] adversative model’ … ; “some women, at least, would want to attend [VMI] if they had the opportunity,” … “some women are capable of all of the individual activities required of VMI cadets,” and “can meet the physical standards [VMI] now impose[s] on men” (Virginia 1996:550).

As Gibson (Citation2006:148) tells us, Ginsburg moves away from a “monolithic understanding of ‘woman,’” drawing our attention instead to women’s differing abilities and objectives. The opinion, then, works to make women as a group more complex, and in doing so heightens attention to women and elevates their status by asserting and even normalizing the idea that some women are highly capable of the rigorous VMI training.

Notable among the pro-plaintiff barriers cases is the development over time of this resistance of gendered stereotypes used to treat women and men unequally. That is, an egalitarian-feminist understanding appears to strengthen over time. In Cannon v. University of Chicago (441 U.S. 677 [1979]) and Hishon v. King & Spalding (467 U.S. 69 [1984]), the earliest two barriers cases decided in favor of the female plaintiffs (), the court offers limited recognition of gender discrimination. Cannon involves the court deciding in favor of a private remedy under Title IX. The decision refers to “victims of discrimination” (Cannon 1979:709) but offers limited discussion of educational gender discrimination. In a footnote, the opinion describes how medical schools’ age policies (not admitting applicants over 30 years old) impact women, who may delay their “education” (a distinct word in ) because of childbearing. The court, however, does not rule on such policies but simply acknowledges this experience of women (Cannon 1979:680 n.2). Hishon, too, barely discusses gender-based workplace discrimination.

As the later cases unfold, however, the court expands its understanding of gender bias. In Anderson v. City of Bessemer (470 U.S. 564 [1985]), the court’s attention to gender inequality expands, as the justices delve into the differential treatment of a female job candidate compared to her male counterparts, concluding that “only petitioner had been seriously questioned about her family’s reaction” (Anderson 1985:570). The court accepts that “the male [hiring] committee members believed women had special family responsibilities that made certain forms of employment inappropriate” (p. 570). Anderson does not use the word “stereotype,” but its attention to the problem of invoking a belief that women have “special family responsibilities” to determine hiring reveals the court’s understanding that such gendered beliefs can result in discrimination.Footnote9 Price Waterhouse and Virginia, then, elevate the court’s resistance of gendered stereotypes considerably further.

Desert Palace v. Costa (539 U.S. 90 [2003]) presents an exception to this progression in that while the decision favored the plaintiff, as Mann (Citation2020:32–33) describes, it presents a “sanitization” of the facts and “Ms. Costa and her experience are relegated to the background.” This may be because Justice Clarence Thomas, a conservative, authored the opinion. While our WE/NN text analysis uncovers a sharper distinction between wording in the pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent opinions than between opinions written by liberal and conservative justices, we note that in most cases (17 of 25) liberal justices author pro-plaintiff decisions and conservative pro-opponent. Among the eight decisions where this does not hold true, six are pro-plaintiff decisions authored by conservative justices, and all but one of these occurs in earlier years (). The ideologies of the justices clearly overlap with the pro-plaintiff and pro-opponents’ decisions, with conservative justices authoring more pro-opponent and liberal more pro-plaintiff decisions. The lack of alignment is more prominent in the earlier years (six out of eight in the 1970s and 1980s). It may be that, during these earlier years, when the case evidence clearly indicates gender discrimination and legal arguments convincingly define how the law is violated, conservative justices support a ruling in favor of women. In recent years, perhaps with growing polarization on the court (Devins and Baum Citation2019), a compelling set of facts pointing to discrimination, as we see in Ledbetter v. Goodyear (550 U.S. 618 [2007]) and Wal-Mart v. Dukes (603 U.S. 571 [2011]), do not necessarily result in decisions favoring more equal treatment of women.

WAGES-AND-BENEFITS INEQUALITY

provides our WE/NN graph for the wages-and-benefits Supreme Court decisions. Here, again, we find meaningful differences in the justices’ vocabulary in deciding for and against the female plaintiffs. On ’s left-hand side, where distinct words characterizing the court’s opinions favoring women are listed, we see the justices relying on language referencing pay and benefits, including earnings and benefits disparities between women and men, using the words “contributions,” “difference(s),” “earning,” “higher,” “plans,” “disparity,” and “salary.” This vocabulary emphasizes women’s experiences and the harm to women. For example, Corning Glass v. Brennan (417 U.S. 188 [1974]) involves a case in which employers pay female employees less than male employees, with no difference in their jobs other than the time of their shifts. In this victory for the female plaintiffs, the court uses language focused on the wage inequality experienced by women, stating, in response to a step taken by the employer to ameliorate the pay disparity, that “Corning’s action still left the inspectors on the day shift—virtually all women—earning a lower base wage than the night shift of [male] inspectors because of a differential initially based on sex and still not justified by any other consideration” (Corning 1974:207–8). Additionally, when viewed in their specific word contexts, other distinct words on ’s left-hand side (“average,” “alike,” and “enjoyed”) are shown to be part of this emphasis on a key egalitarian-feminist concern of female-male pay and benefits disparities.

County of Washington v. Gunther (452 U.S. 161 [1981]), another pro-plaintiff wages-and-benefits case, also considers pay inequality, this time for prison guards. The Gunther justices, ruling in favor of the female guards, criticize the employer’s narrow interpretation of the Equal Pay Act’s meaning of “equal work,” by focusing on women’s experience under such an approach, stating that an underpaid woman “could obtain no relief—no matter how egregious the discrimination might be—unless her employer also employed a man in an equal job in the same establishment, at a higher rate of pay” (p. 178).

These opinions use vocabulary centered on the inequalities experienced by women. Like the barriers decisions favoring women, this centering of women’s experience elevates women’s status by recognizing the harms gender discrimination imposes on women. The Corning majority also moves beyond simply acknowledging women’s lower wages, noting that “many families [are] dependent on the income of working women” and, additionally, stating that “depress[ing] wages and living standards for [female] employees” ultimately impacts “their health and efficiency” (Corning 1974:206). While the court does not refer to “stereotypes” in its decision, one can see egalitarian-feminist pushback in this early decision against traditional beliefs that women’s pay is inconsequential to families.

The justices’ distinct language in the pro-plaintiff wages-and-benefits cases also allows us to see their insights into posited solutions to workplace gender inequality. The Corning majority, with Justice Thurgood Marshall writing the opinion, uses its distinct language to indicate a liberal-feminist formal-equality remedy to the problem of pay inequality, stating, “[t]he objective of equal pay legislation … is not to drag down men workers to the wage levels of women, but to raise women to the level enjoyed by men” (Corning 1974:207). Women’s status as workers, as defined by their pay, should be equal to that of men. In City of LA v. Manhart (435 U.S. 702 [1977]), the court explores a more complex solution. Manhart entails a Los Angeles Department of Water and Power requirement that female employees pay a larger amount than male employees into the Department’s pension fund, because women on average have longer life spans. The court resolves that compelling any individual female employee to contribute more than her male counterpart is a violation of workplace anti-discrimination law: the law “precludes treatment of individuals as simply components of a racial, religious, sexual, or national class. If height is required for a job, a tall woman may not be refused employment merely because, on the average, women are too short” (Manhart 1977:708). Simply, an actual average group characteristic cannot be used to make workplace decisions regarding an individual group member. One might describe this as exhibiting “classic” liberal feminism (Chamallas Citation2013:47), with its focus on individuals rather than group differences.

On ’s right-hand side, the results show, in opinions where it rules against women, the court’s distinct language takes a different form. The pattern at first is not fully evident but becomes clear once we consider the words in their contexts. As the court refers to women, it focuses on the employers and their “practices,” rather than women’s experiences. In Ford v. EEOC (458 U.S. 219 [1982]), for instance, the justices decenter women by focusing on circumstances providing employers or managers with an “incentive” to voluntarily comply with the law, hire the Title VII claimants, and provide them with seniority. The attention is away from women and rather centers on how to incentivize employer or manager actions. In Ledbetter, a case concerning male-female pay inequality, the court again hones in on employers and managers, using, for instance, the distinctive word “supervisor,” stating that a “single Goodyear supervisor” (Ledbetter 2007:15) was responsible for the discriminatory behavior many years before, effectively absolving Goodyear, the company, of current blame in the case and minimizing the harm to plaintiff Lilly Ledbetter.

Using another distinctive word, “unfairly,” the Ford court additionally focuses on male employees, continuing the pattern of limited concern for female workers’ harm. Here, the court suggests male employees will lose employment and “be unfairly laid off” and “the established seniority hierarchy” will be disrupted if the case favors female workers. The concern is with possible subversion of the gender-status hierarchy, with the “innocent [male] employees” losing out “because a Title VII claimant unfairly has been granted seniority” (Ford 1982:241). We note that implicit in the characterization of the male employees as “innocent” is a portrayal of the female claimants as agents who harm these innocent employees, by litigating and challenging the existing system. The harm narrative is flipped, and, rather, women harm men.

While much of the distinct language in the pro-employer wages-and-benefits opinions focuses on employers and male employees, sometimes the distinct words are used to reject the plaintiffs’ arguments, in particular, using “lose” and variations on “discriminate.” Both Lorance v. AT&T (490 U.S. 900 [1989]) and Ledbetter cite case precedent for time limits on discrimination claims, to refuse female workers’ assertions that prior employer acts that “discriminatorily dismissed the plaintiff” (Lorance 1989:907) or that caused the plaintiff to “lose” benefits (Ledbetter 2007:637) would permit current claims of workplace discrimination. The focus continues in these discussions on employer actions but with the important aim of rebutting the plaintiffs’ arguments and instead defining the employers’ current treatment of female workers as nondiscriminatory.

Another example from Ledbetter reveals use of an additional distinct word, “animus.” Here again, the court denies the claim that the employer acted with a discriminatory “animus” (Ledbetter 2007:637). The focus continues to be on employer actions and in doing so provides little attention to Ledbetter’s own experience at Goodyear. As Ginsburg’s dissent (p. 649) points out, in describing the “realities of the workplace,” Ledbetter had no way of knowing her pay was less than her male counterparts early in her tenure at Goodyear and the inequality continued for many years. Ledbetter only found out much later, after legal time limits had expired, when she received an anonymous note revealing the substantial pay disparity (Ledbetter Citation2012). Ginsburg’s dissenting point is that the court failed to recognize Ledbetter’s experience and how workplace gender discrimination operates. The Ledbetter majority, with its emphasis on Goodyear’s actions, concludes instead that, even with a history of pay inequality, no “animus” in Goodyear’s treatment of Ledbetter occurred.

In Wal-Mart, an opinion authored by Justice Antonin Scalia, we see a similar discussion. Distinct wording in Wal-Mart as it discusses women is, again, centered on employer “practices.” The court concludes, after analyzing Wal-Mart’s employment practices, there are no grounds for a class-action lawsuit for gender discrimination regarding pay and promotions, asserting, “there is nothing to unite all of the plaintiffs’ claims, since … the same employment practices do not “touch and concern all members of the class”” (Wal-Mart 2011:359 n.10). The majority articulates its disbelief that gender bias permeates the workplace and shapes decisions about male and female employees. Scalia states, “[i]n a company of Wal-Mart’s size and geographical scope, it is quite unbelievable that all managers would exercise their discretion in a common way without some common direction” (p. 356). The court dismisses statistical evidence and the social science expert testimony regarding gender bias in workplace organizational norms, where, as substantial research shows (Wynn and Correll Citation2018), unless employers routinely take active steps, implicit bias enters into subjective workplace decisions, including those involving wages.

The focus of the distinct language in these pro-employer wages-and-benefits opinions as they reference women remains largely centered on the employers’ and their managers’ actions, with the court asserting employers and supervisors are not for the most part discriminating against female employees. More so in the later Ledbetter and Wal-Mart decisions, the court uses this focus on employers to refute plaintiff claims that discrimination against female employees occurs through gendered beliefs factoring into workplace decision making, even when the evidence suggests discrimination occurred (Brake Citation2008; Paetzold and Rholes Citation2017). We see this culminating in Wal-Mart, where the court appears incredulous that widespread and often unconscious gender bias exists.

Pregnancy in the Workplace

When we compare pregnancy-discrimination cases decided in favor and against pregnant workers, differences also emerge. On the left-hand side of , we find that when the justices decide in favor of pregnant employees, as they discuss women, they invoke distinct words including “ability,” “tasks,” and “perform,” which, viewed in their word contexts, reveal the justices acknowledging the ability of pregnant workers to perform work tasks while pregnant. For instance, in the early Cleveland v. LaFleur (414 U.S. 632 [1974]) decision, the court rules against school boards compelling teachers to take a mandatory eight-month pregnancy leave, stating, “[w]hile the medical experts in these cases differed on many points, they unanimously agreed on one—the ability of any particular pregnant women to continue at work past any fixed time in her pregnancy is very much an individual matter” (p. 645). Throughout much of the period we examine, the court’s decisions favoring pregnant workers recognize their ability to work and, by doing so, help normalize pregnancy in the workplace, raising pregnant women’s status as legitimate workers (Lens Citation2004).

In discussing this ability, the court also often acknowledges harms to women when employers do not recognize this ability. In LaFleur (1974:414), the justices see the injury of denying work to these employees, calling it discriminatory, and they resist stereotypes by stating that broad and “factually unsupported assumptions” about pregnant workers cannot be used to compel teachers to cease work five months prior to their due dates and not return until three months after. The LaFleur opinion also goes further and asserts encroachments by workplace pregnancy policies on teachers’ individual rights to due-process liberty. In fact, the LaFleur court bases its opinion in favor of the pregnant teachers on the need to give women the right to make decisions about when to bear a child (using distinct word “children,” ), rather than compelling them to make the choice based on employment considerations (Dinner Citation2010).

This theme repeats in International Union v. Johnson Controls (499 U.S. 187 [1991]), another pro-plaintiff pregnancy case, where the court reiterates that “[d]ecisions about the welfare of future children must be left to the parents” (p. 206). In Johnson Controls, a case involving an employer policy denying women of childbearing age and pregnant workers access to jobs using lead in production, the justices use other distinct words, “reproductive” and “environment,” similarly. The court holds that employers cannot treat women differently simply because they have “reproductive” capacities and they cannot exclude women from a certain workplace “environment” because of this.

While the distinct words are varied, when viewed in their discursive contexts, our results show the justices in these pro-plaintiff decisions focus on the injuries experienced by women when employers do not permit them to make their own decisions about combining pregnancy and work. By attending to how workplace policies excluding pregnant workers harm women and by asserting women’s rights, the court centers women and elevates their status, considering them as workers with a legitimate claim to self-determination.

A liberal-feminist egalitarian perspective is, again, evident, emphasizing individual rights and pregnant workers’ (equal) ability to work. Limited in this vocabulary is a relational-feminist view where the distinct needs of a pregnant body in the workplace become centered (Chamallas Citation2013). This view does surface in the 1987 California Federal Savings v Guerra (479 U.S. 272 [1987]) opinion, where the court approves a California law providing pregnant employees leave time (although not mandatory leave) and reinstatement following the leave. Employers challenged the law for granting greater protection (and thus preferential treatment for pregnant workers) than specified under federal law. In the opinion, authored by Marshall, the distinct word “goal” is used to emphasize “Title VII’s goal of equal employment opportunity” (p. 283), to “remove barriers that have operated in the past to favor an identifiable group of … employees over other employees” (p. 288), the “barrier” here being an absence of employer policy providing leave time to give birth and the right to job reinstatement. While the opponents argue this is preferential treatment, the Guerra opinion upholds California’s policy for pregnant workers with the goal of achieving equality. Thus, we see protection of the specific needs of pregnancy (using a relational view), however, with continuing emphasis on the overarching goal of equality (an egalitarian view).

By Young v. UPS (575 U.S. 206 [2015]), a pro-plaintiff decision, more than two decades later, the court shifts its approach. In Young, the justices compare pregnant and other similarly situated, temporarily disabled workers and the workplace accommodations received by the two groups. The court states plainly that “an employer who disfavored pregnant women relative to other workers of similar ability or inability to work … engaged in pregnancy discrimination” (Young 2015:1353). Young’s emphasis, then, is on determining the appropriate comparison group among the other workers. Unlike earlier decisions, Young has little to say about the harm experienced by pregnant workers confronted with unfavorable rules, although the court briefly acknowledges that Peggy Young was compelled during her pregnancy to “stay[] home without pay” and without health insurance (p. 1344).

The court rather moves in a different direction, stating, “[w]e doubt that Congress [in the Pregnancy Discrimination Act] intended to grant pregnant workers an unconditional most-favored-nation status” (Young 2015:1350). The court reduces its focus on pregnant workers and their experiences and places more emphasis instead on employer accommodations, endorsing limits on pregnancy accommodations. If another group of similarly situated workers is not receiving an accommodation, then, according to Young, the law does not promise pregnant workers the accommodation, including accommodations that pregnant individuals may specifically need (e.g., additional bathroom breaks, limits on lifting). This is an important step away from the earlier Guerra ruling. While Young is a win for pregnant workers in that the court held that UPS’s accommodation policy, granted to other workers, must be extended to pregnant employees, it is a muted victory. The court is not willing to ensure that pregnant workers receive equity in the form of workplace accommodations they need, a position in line with a relational-feminist framework. In the end, a full normalizing of pregnancy in the workplace espoused by the relational-legal feminists is not achieved.

The results on ’s right-hand side list the distinct words where the justices rule against pregnant workers. The word “preferential” is important in this distinctive vocabulary, as the justices discuss women. The court is concerned with compelling employers to grant pregnant workers “preferential” or “special treatment,” over and above that of other workers, as also surfaced in Young’s “most-favored-nation status.” The pro-opponent decisions (and Young), then, do not elevate pregnant workers’ status through validation of their experiences and the harms they confront in the absence of pregnancy accommodations. Rather, these opinions focus on concern that employers are being compelled to give pregnant workers more than is fair, and the attention shifts to seeming disadvantages experienced by others, particularly male workers. This is resistance to a relational-feminist view, with the contention over what constitutes a neutral policy. Relational theory holds, on the other hand, that a policy giving pregnant workers needed accommodations produces a neutral outcome, one where pregnant workers are not disadvantaged (Chamallas Citation2013).

Resistance to such “preferential” treatment for pregnant workers occurs routinely in the pro-opponent pregnancy cases. Where the justices reference both “plan(s)” and “insurance” in their discussions of women (i.e., employers’ benefits plans or disability insurance related to pregnancy), we find the court discussing workplace advantages of pregnant workers. In the early Geduldig v. Aiello (417 U.S. 484 [1974]) case, the court summarizes evidence that “women contribute about 28 percent of the total disability insurance fund and receive back about 38 percent” (p. 497 n.21). Such assertions work to establish an “us versus them” framework between other workers (who are largely men) and pregnant workers (Lens Citation2004) and indicate that pregnant workers are being unfairly elevated above that of the male workers, which would, as emerged in some wages-and-benefits cases, disrupt the traditional gender workplace hierarchy. Additionally, other distinct words evident in (“alike,” “fringe,” and “facially”) appear in discussions of women where, for instance, the justices rule out including pregnancy in a disability plan, saying this would “destroy the presumed parity of the benefits, accruing to men and women alike” (General Electric v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125 [1976:138]).

Workplace policies, long defined in terms of male norms, as Manian (Citation2016:188) stated, “enshrine[e] male biology” and ignore the biology of workers who become pregnant. Relational theorists argue that equitable workplace policy and law must recognize that pregnant workers require workplace rules that fairly address their needs and experiences. The early Geduldig and Gilbert opinions rejected the notion that policies excluding pregnant workers produced gender discrimination. In both cases, employer policy excluded pregnant workers from disability coverage. As the Gilbert majority states, “[t]he [disability] ‘package’[,] going to relevant identifiable groups we are presently concerned with [for] GE’s male and female employees[,] covers exactly the same categories of risk, and is facially nondiscriminatory in the sense that ‘[t]here is no risk from which men are protected and women are not’” (Gilbert 1976:138). This response assumes that this mode of equal treatment will result in an equal outcome, that such a “neutral” policy is fair (Bartlett Citation1991:381), when, in fact, given the realities of pregnancy and childbirth, pregnant workers require benefits coverage and accommodations that other workers do not. Without such provisions they experience harm.

Resistance to “preferential” treatment for pregnant workers gained momentum in the pro-opponent pregnancy decisions in the 1980s and illustrates the focus of these decisions on employer policy rather than harm to those experiencing pregnancy. In Wimberly v. Labor and Industrial Relations Commission of Missouri (479 U.S. 511 [1987]; see also AT&T v. Hulteen, 556 U.S. 701 [2009], for similar logic), a 1987 case involving a J.C. Penney employee requesting a leave to give birth, the company granted the leave but provided no right to reinstatement following the leave, highlighting the problem of job rights for pregnant workers. When the plaintiff, Linda Wimberly, less than one month after giving birth, requested to return to her job, her employer told her no work was available. She applied for unemployment benefits but the state denied the benefits because Missouri’s plan did not extend to “a claimant who ‘has left his work voluntarily’” (Wimberly 1987:513).

In deciding the case, the Wimberly court repeatedly refers to “preferential treatment,” ultimately denying the unemployment benefits because, according to the court, the federal standard governing state unemployment policy “does not require states to afford preferential treatment to women on account of pregnancy” (p. 522).Footnote10 While the federal standard states, “no person shall be denied compensation under such State law solely on the basis of pregnancy or termination of pregnancy” (p. 514), Missouri’s provision, the court concluded, was a neutral policy excluding “all persons … unless they leave for reasons directly attributable to the work or to the employer,” J.C. Penney’s lack of reinstatement rights for pregnant workers notwithstanding. Again, the court considers the policy neutral and fair because it treats all workers the same. This runs contrary to the insights of relational-feminist theorizing, which does not decenter the harms to pregnant workers by endorsing such “neutral” policy. The court’s discourse of resistance of presumed preferential treatment centers, rather, on employer policy (and not compelling employers to provide policies supporting pregnant workers), ignoring the detrimental impact for pregnant women.

CONCLUSION

Extensive research in sociology (Crossley Citation2017; Kalev and Deutsch Citation2018; Wynn and Correll Citation2018) investigates workplace and educational gender discrimination. While the Supreme Court establishes law governing these domains and can shape broader societal gendered cultural norms, few sociological researchers focus on the court to understand how this elite institution conceptualizes women and gender discrimination (although, see Edelman Citation2016; Saguy et al. Citation2020). We investigated Supreme Court discourse as it discusses women across 50 years of workplace and educational gender-discrimination cases. Using word-embeddings and nearest-neighbors computerized text analysis combined with close qualitative readings of the opinions, we uncovered how the court socially constructs women, their status, and their experiences. We compared decisions favoring the original plaintiffs with those favoring their opponents and discerned two basic gender cultural status frameworks at work, each with a pronounced presence throughout the period of our analysis.

The distinct vocabulary in the opinions favoring the original female plaintiffs reveals an egalitarian view, often invoking liberal-feminist principles of equal opportunity and individual rights. The justices refute traditional stereotypes, assert women’s competence and equal ability in workplaces and higher education, help normalize women’s presence in these arenas, and declare women’s liberty right to make decisions for themselves about combining work and childbearing. Here, the court centers its discussions on women, describing their experiences and the harms discrimination imposes. Centering women in these ways augments women’s status in workplaces and higher education and resists a gender hierarchy (Ridgeway Citation2011).

The unique wording in the pro-opponent decisions, on the other hand, decenters women, typically by elevating instead organizational practices or male workers, even as the court discusses women. The lack of focus on women does not enhance women’s status and reveals a traditional gender approach with the justices showing little regard for women’s experiences in these settings, which can erase the harms discrimination imposes. The court often focuses on employer practices, by accepting that these practices perpetuate gender inequality, by defending their lack of gender equality, or by validating existing practices deeming them neutral and nondiscriminatory, even when evidence to the contrary exists (Brake Citation2008; Paetzold and Rholes Citation2017). We also find that the court elevates the interests of male workers. For instance, in the pro-opponent pregnancy-discrimination opinions, the court decenters women by focusing on how policies offering pregnancy accommodations disadvantage male workers, with “preferential” treatment for pregnant workers. As legal scholars (Manian Citation2016) assert, labeling pregnancy accommodations as “preferential” adheres to long-held patriarchal assumptions that workplaces should be governed by norms designed for biologically male bodies.

Other researchers (Scarborough et al. Citation2019) track egalitarian and traditional cultural gender frameworks in individual attitudes, showing an increase in the public’s acceptance of egalitarianism. We contribute to this research by using both computerized and qualitative methods to trace the Supreme Court’s use of these ideologies and the basic contours of its articulation of them, specifically, that the court expresses the traditional view by decentering women and the egalitarian view by centering women. These expressions reveal the court’s varied views regarding the status of women in workplace and educational settings. We find continued presence of both frameworks in the court’s opinions and posit an ongoing discursive struggle on the court between the traditional and egalitarian views. This suggests that as public views shift to be more egalitarian, the court is not shifting as well. Additionally, while legal scholars (Neumeister Citation2017) demonstrate limited use of feminist language by the court, our research adds further nuance to this scholarship, showing the pronounced presence of the feminist egalitarian framework by the court.

One development noticeably lacking in the court’s discourse is the adoption of a rich variety of other feminist theoretical frameworks. We find little evidence of relational, intersectional, and postmodern legal feminism in the court’s discourse, and, in fact, we find resistance of relational feminism especially strong in more recent workplace pregnancy discrimination cases.

Scholars (Patton and Smith Citation2017) have documented gender bias at the Supreme Court, and we contribute to this literature with a systematic study of the discourse of the court’s discrimination opinions, as these opinions discuss women. Where other scholars show variation in the court’s gender bias associated with the political ideology or the gender of the justices (Jacobi and Schweers Citation2017; Patton and Smith Citation2017), we show variation linked to the direction of the case’s decision, with pro-opponent decisions relying on a traditional gender cultural framework and decisions favoring the original female plaintiffs using an egalitarian, often liberal-feminist framework. These cultural views are not only evident among the justices, our research shows, they are woven into legal reasoning to justify case outcomes.

While the egalitarian and traditional cultural gender-status frameworks have a stable presence through the period we study, we also find changes in the court’s formulations over time. We see change, for instance, between the earlier and later pro-plaintiff cases, with the later cases’ more explicit embrace of egalitarian-feminist reasoning to support the decisions. Additionally, we see movement in the pro-opponent opinions, particularly comparing the early and later workplace barriers cases. In early cases, the justices judge women as incompetent to carry out necessary duties, concluding that women would cause havoc in workplaces, as in Dothard when the court warned of the detrimental effects if women served as guards in male prisons. The image of incompetent women, however, is rare in the distinct language in later pro-opponent opinions, signaling that this mode of diminishing women’s status, through reliance on traditional stereotypes of women as unfit for workplaces and education (Ridgeway Citation2011), has diminished—substantially, in fact.

However, the court continues to exhibit limited perception of women’s lived experiences and the harm they confront in later pro-opponent cases, and in doing so continues to assert a traditional gender hierarchy. In Wal-Mart, the court viewed statistical evidence of widespread inequality in the company’s wages and promotions yet remained unconvinced women were treated differently than men. In the later pregnancy discrimination cases (including the recent Young case decided in favor of the plaintiff), accommodations for pregnant workers are viewed skeptically, as possibly harming the organization (echoing the concerns about organizational harm voiced earlier in Dothard) by giving “preferential” treatment to pregnant workers, elevating their status above that of non-pregnant (largely male) workers. Thus, while there is change in the traditional cultural framework, women’s experiences are still not on par with those of men. This status distinction, with women’s experiences decentered, resides at the heart of gender bias on the Court today among these pro-opponent opinions.

Given that we compare the justices’ decisions in favor of the original female plaintiffs and those in favor of their opponents, one might argue that differences in the opinions simply grow from the cases’ factual evidence and legal arguments. We acknowledge that to some extent this is the case. That is, pro-opponent opinions are what they are because evidence and application of law do not favor the female claimants. However, we believe there is more to the story, for various reasons. First, our analysis shows that gendered meanings in the way women and their experiences are understood vary in these opinions. The pro-opponent decisions carry more traditional gendered views, where the justices articulate a gender hierarchy of male privilege. In the pro-plaintiff decisions, we find resistance to this gender-status hierarchy and an incorporation of the progressive gender-equality ideation of the women’s movement. In short, more than simple differences in case facts and legal logics occur between the two types of opinions; there are core differences in understandings of gender status.

Second, for some of the pro-opponent decisions, scholars (Paetzold and Rholes Citation2017) remark on the strength of the factual evidence in the cases substantiating discrimination against women. Researchers conclude that, even in the face of compelling evidence, the court rules against women, invoking a traditional gender framework to support the decision. Finally, as noted, substantial empirical support shows that judges and justices bring ideological viewpoints to bear in their decision making and cases are not simply decided based on case facts and legal logic (Harris and Sen Citation2019). Ultimately, our study supports and adds to theorizing regarding gender-status frameworks (Ridgeway Citation2011), empirical gender bias research in the court (Patton and Smith Citation2017), and the presence of egalitarian and traditional gender frameworks (Scarborough et al. Citation2019). We find gender status very much in play in the court’s discourse, albeit in varying ways.

While the analysis we present is limited in that, because the court’s rulings do not incorporate more complex understandings of women, we do not incorporate them here (for instance, utilizing a non-binary gender approach, although see Bostock v Clayton County (590 U.S. __ [2020]), or invoking intersectional understandings of women), we end our discussion with encouragement to scholars interested in using this combination of computerized and qualitative methods. Scholars might pursue other areas of jurisprudence to discern the judiciary’s social construction of other groups, for instance, racial, ethnic, citizenship, and, perhaps going forward, gender-identity groups. Moreover, while our research discerns some shifts in these gendered frameworks over time, researchers might also consider using the approach with repeated analyses through time to trace the emergence, flow, and decline of discursive themes in judicial discourse. The method should prove beneficial in systematically discerning ideas in our judicial system, ideas often at the core of cultural understandings.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Holly J. McCammon

Holly J. McCammon is a professor and Cornelius Vanderbilt Chair of Sociology at Vanderbilt University. She publishes on women’s activism with a focus on legal mobilization. Her work appears in the American Journal of Sociology, American Sociological Review, Social Forces, and Law & Social Inquiry. Her book, The U.S. Women’s Jury Movements and Strategic Adaptation: A More Just Verdict, was published by Cambridge University Press.

Amanda Konet

Amanda Konet is a data scientist at RTI International and holds a master’s degree in data science from Vanderbilt University. Her research interests include collective action, reproductive rights, and social movements.

Notes

1 The court is firmly anchored in a gender-binary conceptualization of gender, and thus we rely on this conceptualization, focusing on inequality between women and men and conceptualizing workers and students as female or male (although see Bostock v. Clayton County 2020). This leads us to use the word “gender” (e.g., “gender discrimination”) narrowly, referencing discrimination between women and men.

2 We located the cases using a wide variety of sources (including Mezey Citation2011; Spaeth et al. Citation2022). We exclude cases with male plaintiffs or plaintiff organizations opposing gender-equality law (e.g., in Grove College v. Bell 1984 the college challenges Title IX) to focus on women’s claims of unfair treatment. Given a virtual absence of race/ethnicity-gender intersectionality in these opinions, we are unable to consider women’s racial and ethnic backgrounds. Finally, we exclude sexual-harassment cases because they merit their own in-depth treatment to consider the roles of dominance and intersectionality theory (Carbado and Harris Citation2019; Crenshaw Citation1989). All legal citations appear in the Appendix.

3 Cannon v. University of Chicago (1979) and United States v. Virginia (1996) are education cases, considering women’s admission into higher education, constituting the population of such education cases. While there were just two education cases, we included them because of their importance. Virginia, for instance, provides a critical articulation of the court’s logic regarding removing access barriers for women.

4 Greenhouse (Citation2020) provides a useful general guide to the workings of the Supreme Court.

5 We also contrasted opinions by conservative and liberal justices. The patterns we observed were distinctly sharper comparing pro-plaintiff and pro-opponent decisions.

6 We include Wal-Mart v. Dukes (603 U.S. 571 [2011]) with the wages-and-benefits cases. This pro-opponent case considers claims of both wage inequality and gender bias in workplace promotions. When we add Wal-Mart to the barriers analysis, the main patterns in our findings do not change.

7 Additionally, we find that the word “managers” in Price Waterhouse, another distinct word in , is used to discuss flawed stereotypical assumptions by the employer that women are “not even capable of functioning as senior managers” (Price Waterhouse 1989:236).

8 The word “nursing” in the graph also invokes a stereotype, as the majority warns that the state should not assume there is no interest among men in nursing educations.

9 Anderson also uses the word “married” (another distinct word, ) to dismiss the opponent’s claim that, because the male committee members were “married” to women who worked beyond the home, they would not discriminate against a woman. This distinct word, then, is also part of the court’s resistance of traditional gendered beliefs.

10 The federal standard stems from the Federal Unemployment Tax Act.

References

- Acker, Joan. 1990. “Hierarchies, Jobs, Bodies: A Theory of Gendered Organizations.” Gender & Society 4(2):139–58. doi:10.1177/089124390004002002.

- Adamany, David. 1973. “Legitimacy, Realigning Elections, and the Supreme Court.” Wisconsin Law Review 1973(3):790–846.

- Bartlett, Katharine T. 1991. “Feminist Legal Methods.” Pp. 370–403 in Feminist Legal Theory: Readings in Law and Gender, edited by K. T. Bartlett and R. Kennedy. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

- Berggren, Heidi M. 2008. “U.S. Family-Leave Policy: The Legacy of ‘Separate Spheres’.” International Journal of Social Welfare 17(4):312–23. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2397.2008.00554.x.

- Berrey, Ellen, Robert L. Nelson, and Laura Beth Nielsen. 2017. Rights on Trial: How Workplace Discrimination Law Perpetuates Inequality. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Brake, Deborah L. 2008. “What Counts as Discrimination in Ledbetter and the Implications for Sex Equality Law.” South Carolina Law Review 59(4):657–72.

- Brewer, Rose M., and Nancy A. Heitzeg. 2008. “The Racialization of Crime and Punishment: Criminal Justice, Color-Blind Racism, and the Political Economy of the Prison Industrial Complex.” American Behavioral Scientist 51(5):625–44. doi:10.1177/0002764207307745.

- Broverman, Inge K., Susan Raymond Vogel, Donald M. Broverman, Frank E. Clarkson, and Paul S. Rosenkrantz. 1972. “Sex Role Stereotypes: A Current Appraisal.” Journal of Social Issues 28(2):59–78. doi:10.1111/j.1540-4560.1972.tb00018.x.

- Carbado, Devon W., and Cheryl I. Harris. 2019. “Intersectionality at 30: Mapping the Margins of Anti-Essentialism, Intersectionality, and Dominance Theory.” Harvard Law Review 132(8):2193–239.

- Chamallas, Martha. 2013. Introduction to Feminist Legal Theory. 3rd ed. New York: Wolters Kluwer Law & Business.

- Crenshaw, Kimberlé. 1989. “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989(1989):139–68.

- Crossley, Alison Dahl. 2017. “Women’s Activism in Educational Institutions.” Pp. 582–601 in The Oxford Handbook of U.S. Women’s Social Movement Activism, edited by H. McCammon, V. Taylor, J. Reger, and R. Einwohner. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dahl, Robert A. 1957. “Decision-Making in a Democracy: The Supreme Court As a National Policy-Maker.” Journal of Public Law 6(2):279–95.