ABSTRACT

This study examines protests targeting Multilateral Economic Institutions (MEIs), namely the WTO, IMF, and World Bank from 1995 to 2018 across a large sample of countries using data drawn from media reports. We consider conventional social movement arguments regarding domestic and international resources and political opportunities, as well as economic threats, integration into the global economy, and the effects of international lending. Hypotheses are evaluated using negative binomial panel regression models of annual country protest counts. Results are consistent with several arguments. Recessions and high unemployment are associated with the number of anti-MEI protests, and countries that receive large IMF loans also tend to have more protests. Moreover, we observe a globalization of the political landscape itself. International sites, such as the locations of WTO, IMF, and World Bank summits, serve as powerful magnets for protest. Finally, we note a decline in anti-globalization protests in recent years. We suspect that this reflects the weakening of MEIs, which have seen their influence wane amidst diminished enthusiasm for globalization. As the neo-liberal agenda stalls, MEIs lose salience and social movements have shifted their attention elsewhere.

Introduction

The “Battle of Seattle” brought protests against multilateral economic institutions (MEIs) such as the WTO, World Bank, and IMF into the global spotlight. In the period leading up to the 1999 WTO summit, activists in progressive social movement organizations and labor unions worked tirelessly to consolidate a broad protest coalition. International diplomats and financiers, expecting minor demonstrations, instead peered out their hotel windows onto crowded streets of tens of thousands of ordinary citizens gathered to challenge them. Activists demanded that WTO policymakers, who had been advancing a business-friendly neoliberal agenda, fashion world trade policy to strengthen labor unions, improve working conditions in the Global South, protect the environment, and address other social justice-oriented issues. The ensuing actions involved days of violent clashes between protesters and police and captivated global attention.

The Battle of Seattle was a landmark moment in the anti-globalization movement (Smith Citation2001, Citation2020). However, it was just one instance of a much broader transnational phenomenon of activists targeting international governance institutions that are key agents of economic globalization. In addition to the WTO, protesters have targeted the World Bank and International Monetary Fund, two international financial institutions that provide loans to developing countries, often contingent on their adoption of structural adjustments to their economies (Wood Citation2013). Together, these three organizations have been considered primary vessels of the neoliberal economic agenda, constituting an “unholy trinity” that has drawn the ire of activists worldwide (Peet Citation2003).

The anti-globalization movement arguably peaked during the early 2000s, when large coalitions of progressive groups organized actions during several summits of major MEIs in European or American cities, drawing a great deal of media and scholarly attention (Almeida and Lichbach Citation2003). Though protest actions in the affluent West garnered the most attention, many actions against MEIs have occurred in the Global South, often as one facet of larger and more complex national and international movements (Almeida Citation2014; Walton and Ragin Citation1990; Walton and Seddon Citation1994).

The present study seeks to expand our understanding of the anti-globalization movement by systematically studying the occurrence of anti-MEI protests around the world. We evaluate arguments that may explain cross-national and longitudinal variation in protests against the core neoliberal governance institutions: the WTO, IMF, and World Bank. We constructed a new dataset on anti-MEI protest events over the period 1995–2018 from a machine-coded event dataset collected by the ICEWS project (described below). Negative binomial regressions are used to examine the role of resources, economic threats, and political opportunities as potential explanatory factors. We also consider global factors, such as a country’s integration into the world economy, their receipt of IMF-sponsored loans, and foreign direct investment.

The results support multiple arguments. Domestic and international economic pressures, such as recessions and high unemployment rates are, associated with more protests against MEIs. Countries that received large sums of IMF structural adjustment loan money also experienced more protests. In addition, international summits of the WTO, IMF, or World Bank served as a powerful magnet for protests, suggesting a globalization of political opportunity structures. Lastly, we note that the recent decline in protests against these institutions tracks strongly with declining discursive attention to them. In other words, as globalization has garnered less attention in recent years, social movements are simultaneously targeting the institutions associated with globalization less frequently.

Opposition to Globalization

Globalization refers to the ongoing expansion of international economic interactions, information exchange, and cultural ties between countries, firms, and people. Economically, the total volume of services, data, and physical goods being traded across borders has soared (Ortiz-Ospina and Beltekian Citation2014). Globalization has also entailed the spread of increasingly common cultural and political norms across borders. Overall, these processes have had far-reaching cultural, economic, and political consequences.

As the Battle of Seattle and other anti-MEI protests illustrate, globalization has prompted substantial criticism and resistance (e.g., Almeida Citation2014; Smith Citation2020). The expansion of globalization has been guided by neoliberal policies of deregulated trade and minimal barriers to foreign investment. Critics charge that this agenda has undermined social welfare programs, prioritized the desires of multinational corporations over those of workers, and encouraged a “race to the bottom” whereby developing countries compete to lower worker safety standards and wages to attract foreign business (Rudra Citation2008; Stiglitz Citation2006). Scholars have also raised concerns regarding the governance of globalization, which may be disproportionately influenced by affluent nations and fail to address the needs and interests of vast populations, sometimes termed democratic deficits (Held and Koenig-Archibugi Citation2005).

In addition, economic disruptions associated with globalization have spurred social and political actors to react, often offering remedies to economic dispossessions or loss of status. Research has accumulated on how globalization plays a role in shaping social movement activity, diffusion, and targets (for a review, see Almeida and Chase-Dunn Citation2018). Influxes of foreign investment have been found to increase labor unrest (Robertson and Teitelbaum Citation2011), and the loss of manufacturing jobs in US states due to outsourcing drove the 1990s right-wing militia movement (Van Dyke and Soule Citation2002). The pressures and dislocations associated with globalization have also been cited as a reason for the rise of contemporary populist parties (Mughan, Bean, and McAllister Citation2003; Rodrik Citation2021).

Popular resistance to neoliberalism has been frequent and has taken a multiplicity of forms – often as one facet of complex multisectoral struggles (Almeida Citation2014; Almeida and Martín Citation2022). Smith et al. (Citation2018) find that since the 1950s, transnational social movement organizations (TSMOs) have proliferated worldwide, attracting greater participation in peripheral countries and enhancing cross-national ties. The World Social Forum (WSF), an annual meeting of progressive social movements that at most attracted 90,000 participants, was one of the most noteworthy manifestations of transnational activism (Baiocchi Citation2005:61). Some note that the WSF represented a desire for activists to shift focus from purely oppositional protests against international institutions to articulating a shared vision of the future (Smith and Reese Citation2008; Smith Citation2008; Smith et al. Citation2015).

The appearance of the Global Justice Movement (GJM) in the late 1990s, sometimes considered synonymous with the anti-globalization movement, was a key development in transnational organizing against globalization. The Global Justice Movement has been described as “the loose network of organizations (with varying degrees of formality and even including political parties) and other actors engaged in collective action of various kinds, on the basis of the shared goal of advancing the cause of justice (economic, social, political, and environmental) among and between peoples across the globe” (della Porta Citation2007:6). The GJM differed from the more isolated, sporadic protests that occurred as reactions to IMF or World Bank structural adjustment policies in that it was characterized by significant networking, sharing of tactics, and solidarity events with fellow activists across borders. Within the larger GJM, civil society groups such as Peoples’ Global Action helped provide networks for activists from the Global North and Global South (Wood Citation2005a).

Among the notable events in this vein of activism were a series of demonstrations that targeted MEIs, such as the World Trade Organization, International Monetary Fund and World Bank. Since the 1970s, these three organizations have served to anchor and propagate liberal economic policies, sometimes encroaching on national sovereignty in doing so. Given their hegemonic role over the world economy, they were perceived by GJM activists as pertinent targets (Almeida and Lichbach Citation2003). Arguably the defining moments of the GJM were large rallies at major international summits of MEIs that drew thousands of participants, such as the 1999 WTO meeting in Seattle and the 2000 IMF-World Bank meeting in Washington DC. This followed a trend in recent decades whereby conferences of intergovernmental organizations have become important sites of contention for activists (Smith and Wiest Citation2012). Actions at MEI conferences themselves were often accompanied by solidarity mobilizations worldwide (Almeida and Lichbach Citation2003). The coalitions that came together to demonstrate against MEIs were highly diverse, with major differences in ideology and preferred protest tactics (Levi and Murphy Citation2006).

While protests at summits of MEIs garnered a global media spotlight for anti-globalization activism in the 1990s and 2000s, protests against IMF and World Bank-sponsored programs were already common in the Global South. There have been a number of studies homing in on these movements against international lenders in regions of the Global South (Almeida Citation2007; Ortiz and Béjar Citation2013; Walton and Seddon Citation1994), and numerous case studies on national manifestations of the Global Justice Movement exist as well (della Porta, Citation2007). Other studies have shed light on the profiles of anti-globalization protesters (Cameron and Nickerson Citation2009; Fisher et al. Citation2005) and the organizing frames they employ (Ayers Citation2004; Chesters and Welsh, Citation2004).

Patterns of Protests Against the WTO, IMF, and World Bank

While case studies on anti-globalization activism are bountiful, the present study will seek to explain broad historical and comparative patterns of anti-globalization protest targeting MEIs. In the following, we discuss general arguments that may explain variation in protest drawn from various bodies of literature, and later turn to a cross-national and longitudinal statistical analysis of protest.

Anti-MEI protests are only one facet of broader mobilization against neoliberal globalization (Almeida Citation2014; Wood Citation2005b). Yet, they are of substantive and theoretical importance for several reasons. Protest against global governance represents an upward shift in the level of protest activity – one that is relatively new and rarely studied with quantitative data (but see Podobnik Citation2005). By contrast, large literatures address the emergence of protest against national/local governance and private firms. The study provides an opportunity to evaluate whether conventional arguments apply to global governance protest and also allow us to test some distinctive arguments pertaining to the globalization of political opportunities (below). Moreover, Wood (Citation2005b) finds that anti-MEI protests constitute a large proportion of protests against neo-liberal globalization, highlighting their substantive importance. We recognize that our study does not encompass the full scope of protests against globalization; but within that broader movement, anti-MEI protest represents a theoretically and substantively significant phenomenon.

Resource Mobilization

Classic work in social movements literature argues that resources like wealth and education facilitate social movement actors’ capacity to initiate contentious action (McCarthy and Zald Citation1977). Long-term economic development can afford citizens greater time, money, and civic skills, which are crucial in facilitating protest participation (Brady, Verba, and Scholzman Citation1995). Meyer and Tarrow (Citation1998) interpret the ubiquity of protest activity in developed countries as evidence of a “social movement society.” With regards to the anti-globalization movement, many of the most noteworthy moments, such as the protests during summits of MEIs, occurred in affluent Western countries.

H1:

Countries with greater economic resources will experience more anti-MEI protests.

Domestic Political Opportunity: Democracy & Repression

A second conventional theme in social movements literature shifts attention toward the broader political context that provides constraints and opportunities for contentious actors to mobilize (Amenta Citation2006; McAdam Citation1982; Meyer Citation2004). Most importantly, the level of overall state repression has a very large impact on protest activities. More democratic regimes tend to tolerate political dissent in the form of protests, while autocratic regimes typically are inclined to repress contentious action.

H2:

Democratic countries will experience more anti-MEI protests.

Domestic and Global Economic Pressures

In recent years, there has been renewed interest in economic adversity among social movement scholars (Azedi Citationforthcoming; Caren, Gaby, and Herrold Citation2017; della Porta Citation2015; Kern, Marien, and Hooghe Citation2015; Kurer et al. Citation2019; Quaranta Citation2016). Economic hardships arising from mass unemployment, recessions, or economic crises, can represent “threats” that generate discontent, and ultimately, collective action (Almeida Citation2018; Dodson Citation2016; Gillham et al. Citation2019). Indeed, during periods of poor economic performance, countries often experience greater volume of protest events (Caren, Gaby, and Herrold Citation2017; Quaranta Citation2016). Bergstrand (Citation2014) notably shows that the threat of potential losses are more likely to generate stronger emotions and motivate participation in activism than the prospect of new gains.

We extend these ideas to the case of anti-globalization protests, which often center around economic concerns and injustices. We hypothesize that periods of intensified economic difficulty in a country introduce an element of threat, prompting people to participate in anti-globalization protest.

H3:

Countries experiencing economic adversity will have more anti-MEI protests.

Additionally, a country’s integration into the global economy may spur protest, both because globalization may directly generate new economic changes and because economic integration may lead people to focus their ire on international economic institutions they see as disruptive to their national economic affairs. Economic globalization entails an increase trade and foreign investment, which can disturb established local economic routines for a population. This can create benefits and costs of globalization are unevenly distributed. Economic changes enhance wages and standards of living for some, but erode them for others, generating “winners” and “losers” of globalization (O’Brien and Leichenko Citation2008). This cleavage can be the source of tensions that generate social and political conflicts. Trade shocks have been shown to be consequential for political outcomes, such as increased support for radical political figures (Autor et al. Citation2020; Rodrik Citation2021). With regards to the effect of globalization on protest, existing studies have produced divergent results. Some studies show foreign direct investment tends to stoke labor strikes (Robertson and Teitelbaum Citation2011) while others show that trade activity and FDI tamp down protest expansion (Dodson Citation2015).

We explore the possibility that economic integration may spur anti-globalization protest. In particular, the expansion of trade and investment likely increases a population’s awareness of the effects of globalization on their daily lives. Globalization and the MEIs associated with it may thereby become more salient in people’s political worldview. Social movements, moreover, may be able to more easily frame globalization as a purveyor of undesirable economic changes. Thus, we propose:

H4:

Countries that are more integrated into the global economy experience more anti-MEI protests.

We further consider the specific role of IMF and World Bank structural adjustment programs in stoking unrest in the Global South. Loans from both international financial institutions (IFIs) frequently involve “conditionalities” whereby the recipient country must implement neoliberal economic policies – including privatization, spending cuts/“austerity,” or currency devaluations – to receive cash (Babb Citation2005).

There have been three waves of popular resistance to the IMF and World Bank. The first took place between 1976–1992, the second in the late 1990s mainly in Latin America, and the third after the 2008 crisis, mostly in Eastern Europe and the Philippines (Wood Citation2013). Studies of the “first wave” of anti-IMF protests show that countries with greater urbanization, civil society networks, and higher unionization rates were more likely to experience anti-IMF unrest (Walton and Ragin Citation1990; Walton and Seddon Citation1994). Ortiz and Béjar (Citation2013) show that contentious action is more common in Latin America when a country accepts a loan, and propose the link is driven by an interpretation among civil society that accepting loans damages national sovereignty. Loans can also lead to outcomes like reduced economic growth (Przeworski and Vreeland Citation2000), governmental crisis (Dreher and Gassebner Citation2012), and diminished human rights situations (Abouharb and Cingranelli Citation2006). Drawing on this prior research, we expect:

H5:

Countries whose governments have received structural adjustment loans will experience more anti-MEI protests.

Transnational Movements, Advocacy Networks, and INGOs

Scholars in political science, social movements, and the world society tradition have pointed to ways that international institutions, norms, movements, and organizations support domestic social movements (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998; Olzak Citation2006; Smith Citation2002; Tsutsui Citation2018; Tsutsui and Smith Citation2018). A variety of dynamics have been suggested and studied. Tsutsui (Citation2018), for instance, systematically unpacks the multiplicity of ways that international institutions and norms create and propagate new frames and political opportunities for domestic movements. Others have offered images of the “boomerang” or “sandwich” to highlight the ways that local movements and various global actors may play off each other to put pressure on states (Keck and Sikkink Citation1998; Tsutsui et al. Citation2018).

A central theme across this multidisciplinary literature is the idea that international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) play an important role in supporting domestic movement activity. First, a significant subset of INGOs are themselves transnational social movement organizations and may be directly involved in supporting protest actions across the globe (Smith Citation2002). More generally, scholars in the world society tradition have focused on ways that INGOs are purveyors of global norms related to the environment, human rights, women’s rights and the like, diffusing and legitimating frames for potential movement activity (Boyle Citation2002; Evans, Schofer, and Hironaka Citation2020; Tsutsui Citation2018). Human rights norms, embodied in global institutions and transmitted via INGOs and other intermediaries, have proved an important frame for galvanizing social justice movements worldwide (Tsutsui Citation2018), and may serve as an important complement or alternative to frames involving economic threat. Finally, INGOs are often quite directly involved in supporting protest actions. For instance, environmental INGOs such as Greenpeace and Rainforest Action Network actively diffuse protest repertoires and engage in capacity-building that increases protest among domestic environmental groups, particularly in the global South and non-democratic contexts (Evans, Schofer, and Hironaka Citation2020). Thus, we expect:

H6:

Countries with strong connections to international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) will experience more anti-MEI protests.

Global Political Opportunity Structure (International Summits, MEI Headquarters)

Globalization, which involves invisible flows of trade and investment, is a highly diffuse phenomenon that cannot be easily boiled down to any specific location. However, Multilateral Economic Institutions such as the WTO have been recognized as the “face” of economic globalization. Summits of intergovernmental organizations represent short-term windows of opportunity to protest a target that is otherwise intangible (Kolb, Citation2006), and activists have exploited these opportunities to organize mass actions (Almeida and Lichbach Citation2003; Bédoyan, Aelst, and Walgrave Citation2004; Smith and Wiest Citation2012). Along with the 1999 protests in Seattle, anti-globalization activists mobilized during joint IMF-World Bank summits in Berlin in 1988 (Gerhards and Rucht Citation1992) and Prague in 2000, among others. In addition to international summits, the headquarters of these international organizations may also attract anti-globalization protesters. Just as political protests often target centers of political power (e.g., Washington DC, Paris, London) both as a strategy to influence policymakers and garner media attention, we suggest that the emergence of global governance institutions may produce a shift in protest toward the centers of policymaking. The headquarters of international financial institutions provide an alternative to international summits as a permanent, physical locus where globalization policies are shaped. Thus, we propose:

H7:

International summits of MEIs will attract anti-MEI protests.

H8:

Countries that host the headquarters of MEIs will experience more anti-MEI protests.

Discursive Attention to Globalization: Salience Over Time

It is widely acknowledged that the discursive frames social movement actors employ are critical to mobilizing supporters and attracting bystander sympathy (Benford and Snow Citation2000; Snow and Benford Citation1988). To be effective, a frame must resonate with individuals as an issue that is important and worthy of action. Across time, certain issues can ebb and flow in their salience for populations and their ability to attract willing participants to mobilize around them. Issues and framing strategies that attracted followers to social movements in previous historical periods may lose relevance as political, economic, and social realities change.

There appears to be evidence that the salience of globalization-related topics has fluctuated over time in scholarly discourse and news media. In particular, the 1990s saw large increases in attention to globalization, as neo-liberal policies reached their apex (e.g., Fukuyama Citation1992). In the late 2000s, by contrast, many elements of globalization have become static. The World Trade Organization agenda largely stalled in the Doha round of negotiations in 2001 and failed to produce a resolution for over a decade after (Smythe Citation2015). After questionable decisions and a series of similar unfruitful negotiations, many began to see the WTO as ineffective (Stockman Citation2020). The World Bank and IMF both have come under increasing criticism for harsh structural adjustment policies that effectively handed the economic management of nations to effectively un-democratic international technocrats. The 2008 crisis raised profound questions about the stability of global free market capitalism, and economists have grown skeptical of the supposed universal benefits of unrestricted free trade (Saval Citation2017). Together, these changes have arguably weakened multilateral economic institutions and rendered them less relevant. We propose a corresponding decline in attention to these institutions in global discourse and suggest that this may reduce their salience for social movement actors.

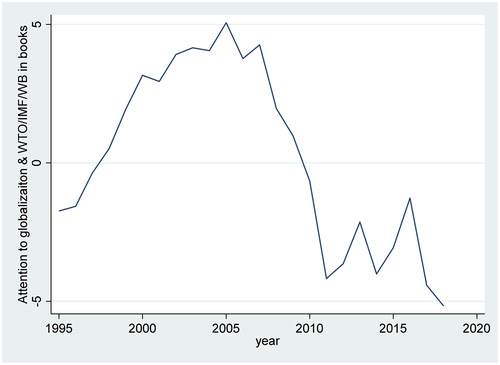

To address this possibility, we present a simple measure of “globalization salience,” based on different measures of popular discourse (See ). We use these measures to explore trends in discourse over time, and later construct an index that we include in our statistical analyses of anti-globalization protest. The measure is based on two sources: the Google N-gram application and the Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS) dataset. Details of the measure are discussed below, in Data and Method. displays a timeline of attention to globalization and its related organizations in books since 1995. Attention to globalization and its related international institutions in books accumulated during the 1990s, was highest approximately between 2000 and 2006, and fell precipitously until 2010, and has remained relatively low since, despite limited spikes in 2013 and 2016.

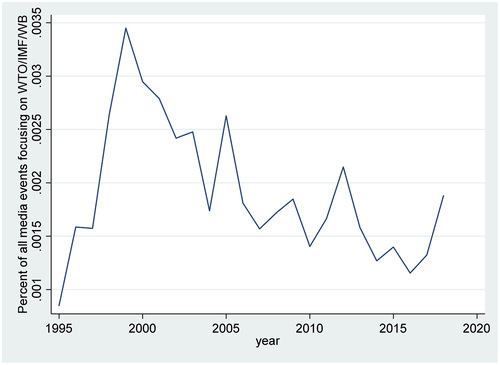

The prominence of the IMF, World Bank, and WTO in news media has declined as well. Using combined data from ICEWS, we track the proportion of total news media events which are directed toward the WTO, IMF, or World Bank. These events can originate from civil society, governments, prominent figures, or other intergovernmental organizations, and thus represent an aggregate view of their salience in global affairs. illustrates how these institutions were highly referenced by global actors in the late 1990’s but were much less prominent throughout the 2010s. Thus, it appears that as globalization decelerates, it is also failing to retain global attention.

As globalization becomes less prominent, the focus of social movement actors may shift away from MEIs. With this in mind, we propose the following:

H9:

Discursive attention to MEIs and globalization will be positively associated with anti-MEI protests.

Data and Method

We analyze country counts of protest targeting major Multilateral Economic Institutions, measured annually between 1995 and 2018, using the country-year as the unit of analysis. The cross-national and longitudinal dataset includes 150 countries and 3,249 country-year observations. We use negative binomial panel regressions, as these models are appropriate for count outcomes such as protest that contain non-negative integers prone to overdispersion. A Hausman specification test indicated that country random effects yielded results consistent with country fixed effects. Consequently, we use the more efficient random effects estimator (Wooldrige Citation2002). displays descriptive statistics for the variables described below.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Dependent Variable

Our goal is to measure citizen protest directed toward MEIs that have facilitated globalization. Following other authors (Peet Citation2003; Podobnik Citation2005), we focus on three key MEIs that have attracted the brunt of grassroots anti-globalization protest: the World Trade Organization (WTO), International Monetary Fund (IMF), and the World Bank. Protests against the WTO, IMF and World Bank have occurred under a variety of contexts. Those that occurred in the Global North, often happening at major summits, sometimes garnered solidarity actions from other countries or from other locations within the same country, constituting “Global Days of Action” (Almeida and Lichbach Citation2003; Wood Citation2005b). Protests against international lenders (IMF and World Bank) were more common in the Global South – where the bulk of loans were distributed – and typically represented national struggles confined to one country. Despite differences in the dynamics behind each individual event, we consider anti-WTO, anti-IMF, and anti-World Bank actions to still be relevant expressions of anti-MEI, and ultimately anti-globalization, protest.

We employ a conventional conceptualization of protest, as involving a set of individuals engaging in contentious collective acts with the intent of opposing authorities and/or producing social change (Tarrow Citation1994). Thus, we are uninterested in protest that is purely rhetorical or virtual (e.g., letters of protest, tweets), actions taken by states/leaders, terrorism, or acts of lone individuals.

We measure the total number of protests against the WTO, IMF, and World Bank occurring in each country-year based on media reports that have been aggregated and coded in the ICEWS (Integrated Crisis Early Warning System) dataset (Boschee et al. Citation2015). ICEWS, building on similar efforts, is the latest project meant to develop automated coding of media reports aggregated from international wire services (Reuters, AP, Agence France-Presse, Xinhua, and the like). Prior efforts in this vein include GDELT (Global Database of Events, Language, and Tone), WHIV (World Handbook of Political Indicators IV), and the KEDS/PANDA (Kansas Events Dataset/Protocol for the Analysis of Non-violent Direct Action) project. Each of these produce data that are commonly used in empirical work to model protest events (Kadivar Citation2017; Massoud, Doces, and Magee Citation2019; Quaranta Citation2016; Sommer Citation1996).

Automated coding of media reports are capable of distilling a list of underlying political events, which are then categorized by type and location. To develop ICEWS, Boschee et al. (Citation2015) employ BBN ACCENT (an automated coding procedure) and the CAMEO (Conflict and Mediation Event Observation) event typology. This is a set of coding procedures that distills media reports down to specific events and seeks to discern the main actor involved (a state, company, group, person), a primary action (e.g., supporting, attacking, protesting, etc), and a target of the action (typically another actor). The coding scheme, developed to study generalized interactions among political actors of all types, is extremely elaborate and includes categories that specifically single out civil society protest events that target specific intergovernmental organizations such as the UN, EU, WTO, and the like. The CAMEO coding scheme includes the name of the institution that was targeted by each media report. Thus, we are able to identify who or what each protest event was directing its complaint toward. We further select out only events that target our MEIs of interest and events that fall in the CAMEO protest category including “Demonstrate,” “Rally,” “Strike,” “Obstruct Passage,” “Violent Protest” and the like, for the purpose of “Policy Change,” “Leadership Change,” “Change in Institutions/Regime,” “Rights,” etc. The resulting dataset includes 290 cases of protest events targeting the IMF, World Bank, or WTO from 1995–2018.

Protest datasets derived from media reports have limitations, the subject of much discussion (Biggs Citation2016; Earl et al. Citation2004; Myers and Caniglia Citation2004). Protest counts typically include events that media outlets considered worthy to report and can undercount protests surrounding certain issues (McCarthy, McPhail and Smith Citation1996; Smith Citation2001). Large, violent protests occurring in central locations and involving timely policy issues are more apt to be reported. International press also cover only a portion of protests covered by national press (Herkenrath and Knoll Citation2011). Thus, our dependent variable must be interpreted with these limitations in mind, as an indication of “globally visible” protest (Evans, Schofer, and Hironaka Citation2020). The automated coding of media events is imperfect, but much better than in the past. ICEWS coding system is robust, coding events identified with 80% accuracy (Lockheed Martin Citation2022). The error rate of CAMEO coding is non-trivial, but low enough that we were encouraged to pursue this study – there is a substantial “signal” in the data, even if a portion of protest events are miscoded or overlooked.

Independent Variables

International Media Coverage

Studies of protest events coded from media sources must control for the general propensity of some countries to garner more international media coverage than others. A host of factors may cause some countries (or particular country-years) to garner more coverage than others: global centrality (the US garners more coverage than peripheral nations); the location of media infrastructure (for instance, countries in Sub-Saharan Africa with press offices get more coverage than countries without), language bias (Anglophone and Francophone nations tend to get more global media coverage), the occurrence of other major global events such as wars that draw international media attention, and so on.

To address this, we control for the total number of media reports in each country-year coded by the ICEWS database on all topics. The measure is logged to reduce skewness.

Democracy

We use Polity IV data, which assesses a regime’s level of democracy on a scale from −10 to 10. Low scores indicate autocratic regimes while high scores indicate democratic ones.

Economic Adversity

We employ two measures of economic adversity in a country: recent recessions and unemployment rates. First, there is the possibility that poor national economic growth may generate economic grievances that spur contentious action (Caren, Gaby, and Herrold Citation2017). We consider economic recessions by looking for countries that experienced a negative GDP growth rate in its recent history. Because GDP shocks may be economically disruptive for some time, we coded a dummy variable as 1 if such a recession had occurred in the last three years. Additionally, we consider unemployment rates. While GDP growth measure national economic standing, unemployment rates may more directly capture the financial well-being of the country’s citizenry. Previous research shows perceptions of economic insecurity track with unemployment rates, and this insecurity is felt by unemployed and employed citizens (Burchell Citation1993; Gallie et al. Citation1998; Green Citation2009). We use the unemployment rate available from the World Bank’s World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2021).

Global Economic Integration

We consider two common measures of global economic integration: trade and foreign direct investment. Trade is measured as the sum of imports plus exports as a proportion of the country’s total GDP. This figure represents the volume of trading and investment the country experiences relative to its economic productive capacity. Foreign direct investment is measured as net inflows, again as a percentage of national GDP. Both measures are taken from the World Development Indicators (World Bank Citation2021).

IMF loan disbursements (log). The IMF’s website contains data on loan arrangements provided to each country. For each loan we determine the amount given to a country each year over the life of the loan, measured in US dollars. If countries received multiple loans in a given year, we total the annual disbursements. Finally, some loans were arranged but not disbursed or only partly disbursed; these are excluded from our totals. We take the log of this measure, which is otherwise highly skewed.

Global Political Opportunities

We operationalize two forms of global political opportunities: the locations that host MEI headquarters, and sites that hosted their international summits. First, we create a dummy variable corresponding to the presence of the headquarters of the WTO, IMF, or World Bank. Geneva, Switzerland hosts the WTO headquarters building, while Washington D.C. hosts the IMF and World Bank headquarters, so this variable is only coded “1” in these two countries. We create a second measure of global political opportunities by measuring the presence of international summits. An example would be the WTO meetings in Seattle in 1999; the United States was coded as 1 for that year. Specifically, we coded a dummy variable representing the presence of a major international meeting of the WTO, IMF, or World Bank in a country-year.

INGO Membership

Prior work observes that international non-governmental organizations (INGOs) provide resources and support for domestic protest (Evans, Schofer and Hironaka Citation2020; Olzak Citation2006). We measure the influence and activities of INGOs with an aggregate measure of total INGO memberships held by citizens of each country, logged to reduce skewness. The measure is coded from the Yearbook of International Associations, which lists INGOs and their country membership ties (UIA 1990–2018; see Schofer et al. Citation2021).

Discursive Attention to Globalization

General attention to globalization is operationalized as the extent to which MEIs, as well as the generalized term “globalization” appear in books and media. We use two measures, which we combine into an index. First, we use Google’s N-gram to identify the percentage of books published each year which mention “International Monetary Fund,” “World Bank,” “World Trade Organization,” or “globalization” in the text. We standardize each measure of these four keywords over time using z-scores, then sum the components to create a measure representing attention to globalization and its related institutions in books. The yearly change in this variable was presented in above. Next, we use ICEWS data, which contains over 18 million news articles from 1995–2018, to find the yearly percentage of news articles that involve any source, which can include prominent world figures, governments, other intergovernmental organizations, or activists initiating some action (positive or negative) directed toward the IMF, World Bank, or WTO. The timeline for this variable was also displayed in above. The measure is also standardized and then averaged with our n-gram measure. The resulting index represents aggregate attention to globalization in both books and news media over time.

Geographic Region

We include dichotomous variables for geographic region to control for additional unmeasured regional differences around the globe (Eastern Europe and Central Asia, sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, Middle East and North Africa, and East and South Asia). These regional groupings were chosen based on the similar historic experiences of the countries within them, rather than the more arbitrary distinction of the continent they are located in. The reference group thus will be the affluent Western countries of North America, Western Europe, Australia, and New Zealand.

Results

displays the results of negative binomial panel regression models with country random effects examining the relationship between economic, socio-political, and regional variables and the incidence of anti-globalization protests. All models include a control for the total volume of media coverage in each country-year to account for the fact that some countries get systematically greater attention (e.g., due to language, location of major media offices, etc). The effect of media coverage is large and highly significant in all models, consistent with prior studies: protests are more likely to be reported in countries (and times) that see high levels of media attention. We also include controls for region in all models. We do not find large regional differences, presumably because we control for relevant factors such as economic development.

Table 2. Negative binomial regressions testing determinants of anti-globalization protests.

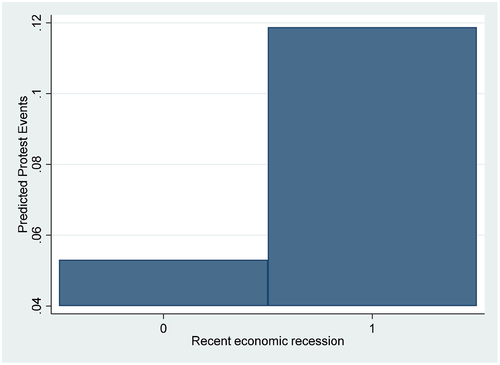

Model 1 examines the effects of domestic and international economic factors on anti-MEI protests. GDP per capita captures a country’s overall level of affluence and reflects people’s resources and leisure time to engage in social movement activities. GDP has a positive but non-significant association with protest. Next, we examine two measures that capture potential domestic economic threats: the occurrence of an economic recession in the previous three years and the country’s current unemployment rate. Both have positive and significant effects on country-year protest counts. This supports classic ideas about economic disruption and precarity as sources of threat, which may be channeled into the anti-globalization movement.

Model 1 also addresses international economic variables that may affect anti-globalization protest. Trade as a percentage of GDP captures a country’s integration into the global economy. To the extent that economic integration drives social problems (e.g., de-industrialization, loss of high-quality employment, etc.), one may expect a positive association with protest. However, in Model 1 (and subsequent analyses) we do not observe a significant association between trade and protest. Other measures of economic integration, such as Foreign Direct Investment also yield no significant effects.

Finally, Model 1 includes a measure of IMF money a given country accessed, one measure of external pressures to participate in Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). SAPs often included harsh and unpopular austerity measures, and their external imposition by unelected global technocrats was seen to highlight democratic deficits. Indeed, we observe that IMF loan disbursements are positively and significantly associated with protest.

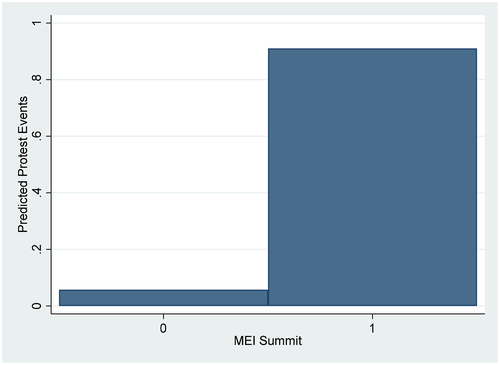

Model 2 adds a series of socio-political variables. Three of these can be classified as political opportunities that facilitate contentious action: a country’s level of democracy, the presence of a WTO, IMF, or World Bank global summit, and the countries that host these institutions’ headquarters. Democracy was positively associated with anti-globalization protest, but the effect is not statistically significant. For global summits, the effect is extremely large and positive. Summits in effect become a magnet for protests as they offer opportunities for protesters to disrupt global governance.

We also examined a dichotomous measure indicating the country headquarters of key international institutions. This measure is negatively associated with protest but not significant. Whereas summits are a magnet for protest, the main MEI headquarters apparently are not as important. Next, we look at country embeddedness in international NGOs. International organizations sometimes act as transnational advocacy networks or transnational movement organizations, engaging in protest themselves or supporting local movement organizations. In the case of anti-MEI protest, however, we do not find evidence that INGOs play a supporting role.

Model 3 introduces one final variable: global attention to international organizations associated with globalization, as captured by Google’s N-gram and the ICEWS data. The variable is positively associated with anti-globalization protests, suggesting that resistance to Multilateral Economic Institutions corresponds to the extent to which these institutions appear in global discourse. During periods where these institutions are highly salient, contentious actors view them as more appropriate targets.

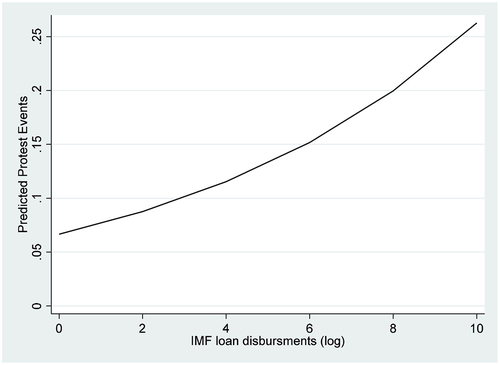

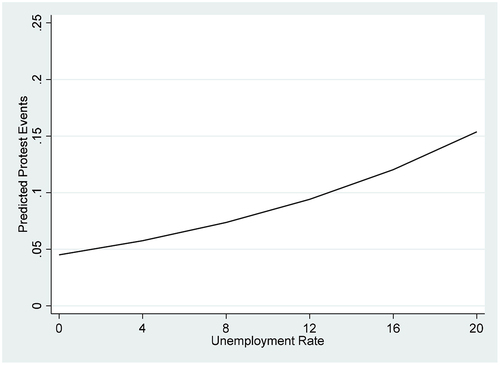

We exponentiate the coefficients from this model to provide greater clarity on how the effect sizes of the variables compare to one another. We find the model predicts that having a recent recession would increase anti-MEI protest in a country-year by 2.2 times, essentially doubling the amount of protest. The effect of unemployment rate is somewhat weaker but still significant: each unit increase corresponds to 1.06 times more protest. A large 10% point increase in unemployment, for instance, magnifies protest by a factor of 1.8 times. Each unit increase in log IMF loan money was associated with 1.14 times more protest. A typical-sized IMF loan corresponds to a 36% greater protest count. Results further suggest that MEI summits have a very powerful effect: we see a 15-fold increase in anti-MEI protest in country-years with summits. Finally, with each point increase in our index of discursive attention to globalization, 1.66 times more protest could be expected. Inverting this ratio shows that each unit decline reduces protest by a factor of .6, a decrease of 40%. The secular decline in discursive attention since 2005 corresponds to an expected 90% decline in protests. display the effect of selected independent variables on predicted protest events.

In model 4, we control for year fixed effects, which addresses potential omitted variables associated with time. This requires dropping country-invariant measures – in this case our time-varying “discursive attention to globalization” index. Results in model 4 are broadly similar, but we see some differences: MEI headquarters becomes significant (B = 1.06; p = .045), unemployment falls to marginal significance (B = .049; p = .068), and IMF loan money becomes slightly more significant (B = .241; p = .000). We present year fixed-effects to address concerns about omitted variable bias, but the addition of year fixed effects actually worsens model fit on indices such as AIC & BIC compared to prior models. Arguably the more parsimonious Model 3 is preferable. The key takeaway appears to be that when year effects are accounted for, the findings are broadly consistent, but we do see some support for the argument that MEI headquarters are a global magnet for protest.

Robustness Checks

We conducted a variety of robustness checks to assess the stability of our findings. First, we addressed the possibility that outlier cases of country-years with a large number of protests disproportionately drive the findings (e.g., Seattle in 1999). However, excluding several outlier country-years did not notably alter our results.

We next added a variable for past anti-MEI protest, the cumulative number of previous protests against MEIs the country had experienced to that point. Protests against MEIs confer valuable strategic experience movements can draw upon to successfully mobilize again (Almeida and Martín Citation2022:14). When added to the models, the coefficient was negative and significant in some of our models but did not change the overall findings. We attribute this finding to the sporadic and extremely skewed distribution of protests. Years of high levels of protest – often linked to exogenous factors such as MEI ministerial conferences – are typically followed by relative quiescence. Nonetheless, in the full model with past protest included (cumulative or prior annual count), our main findings do not change.

One could argue that the processes giving rise to protest might differ between industrialized Western countries and the countries of the global South. To address this, we examined a series of interaction between our key variables and a dummy variable for the Global South (not presented; available on request). Interactions between Global South and unemployment, IMF loan money,Footnote1 recessions, trade volume, and FDI, respectively, produce no significant effects. The interaction term between Global South and summit was positive and significant. While MEI summits are associated with protest generally, the effect is larger in the Global South. This result is likely attributable to the fact that fewer anti-MEI protests occurred in the Global South to begin with. Thus, what anti-MEI protest did occur in the Global South was more highly concentrated in country-years of summits.

In addition, we explored independent variables to address additional economic factors influencing anti-globalization protests. In particular, we constructed a more precise measure of IMF loans with structural adjustment conditionalities (not presented; available on request). Conditionalities attached to loans from international financial institutions often entail major economic restructuring policies that can disrupt the well-being of working populations, such as privatization and cuts to social services. Using IMF data, we identified which IMF loans contained conditions and then calculated the total amount of conditional loans active in a country at a time. Data on conditions was only available from 2006–2018. When used in a model in place of the total amount of IMF loan money, the coefficient for the total amount of conditional loans active in a country was positive and significant. When conditional loans and total loan money were used in the same model, both were significant. This shows the importance of IMF loans, and particularly loans with conditionalities, in stoking protest.

Next, we noticed that discursive attention to globalization bore a yearly pattern that roughly resembled the expansion and decline of economic globalization itself. Attention to globalization increased rapidly throughout the 1990s and peaked in the early- and mid-2000s but has been far lower after roughly 2008. The rate at which global trade expanded and slowed occurred at approximately similar time points, accelerating throughout the 1990s and early 2000s, and failing to keep pace after 2008 (WTO Citation2022). Thus, it is possible the significant effect of discursive attention on protest seen in might be better explained by an aggregate measure of actual economic globalization. The KOF globalization index provides a yearly aggregate measure of global economic connectedness (Dreher Citation2006). We experimented in several ways with this measure, using the raw yearly figures, the percentage change per year, and a moving average of the previous three and five years. In no scenario was the KOF index variable significant for protest. We interpret this to further suggest that popular attention to globalization was more important in explaining protest than material expansion and contractions in globalization.

Finally, we examined panel regression models with country fixed-effects. This reduced our sample, as countries experiencing no protests were necessarily excluded. Though the large reduction in cases resulted in diminished the statistical significance levels of all variables, global summits, recessions, and attention to international economic organizations all remained positive and significant at least at the p < .05 level. Unemployment rate, IMF loan value, and total media coverage were at the border of significance. This indicates a generally consistent pattern across fixed and random effects models. A Hausman specification test indicated that our original random effects model was preferred to the less-parsimonious fixed effects model.

Overall, robustness checks affirm our core finding that economic threats, political opportunities, and global discourse around globalization are the key drivers of anti-globalization protest.

Discussion and Conclusion

Globalization has entailed that the management of economic affairs has shifted from national to supranational, and the influence of Multilateral Economic Institutions such as the WTO, IMF, and World Bank represent arguably the most conspicuous example of this. Simultaneously, social movement actors have adapted, utilizing new repertoires of contention and expanding networks across borders to meet the challenge presented by the internationalization of power structures.

Research on anti-globalization protests have explored the movement’s coalitions (Levi and Murphy Citation2006), frames (Ayers Citation2004; Chesters and Welsh Citation2004), networks (Smith and Weist Citation2012; Smith et al. Citation2018), geographic distribution (Podobnik Citation2005) and characteristics of individual participants (Cameron and Nickerson Citation2009). This paper advances the literature by providing a systematic global study of protests directed toward the institutions of global economic governance. Our analysis of anti-globalization protest finds support for classic traditions of social movement studies: those that emphasize economic adversity and political opportunities. Further, we find that a worldwide spotlight on globalization, as reflected in its coverage in media and books, influences the extent to which social movements organize anti-globalization protests. Of course, the usual caveats apply. Our study is based on protest data derived from media reports, which does not represent the full universe of protest events. In particular, our findings may not apply to small, peaceful protests, which may be undercounted in such datasets. Moreover, our study is observational. We control for some relevant confounders, but our correlations are just that – correlations.

We observe that protests are more frequent in societies experiencing economic hardship, such as recessions and high levels of unemployment, consistent with a recent reinvigoration of social movement scholarship on economic precarity and threats (Caren, Gaby and Herrold Citation2017; Kurer et al. Citation2019; Quaranta Citation2016). In addition, we see a clear association between international lending and protest; protests were more frequent when countries received large amounts of loan disbursements from the IMF. Corollary analyses of more recent years suggest that conditional loans that entail structural adjustment programs are especially important. This is consistent with the idea that international neoliberal structural adjustment policies – oftentimes associated with harsh austerity and the erosion of national sovereignty – propelled mobilization against these institutions. Together, these findings suggest that populations are responsive to material economic conditions they are enduring, and often direct frustration with poor conditions against international agents of globalization.

Next, our findings are consistent with the argument that international summits of the WTO, IMF, and World Bank serve as short-term windows of opportunity for social movement actors to challenge concepts like neoliberal globalization, which are typically abstract and intangible (Kolb Citation2006:115). Our models suggest that social movements have indeed set their sights on the institutions of global governance, and most obviously, their international meetings. Additional analyses find that among affluent countries protest occurs more often in countries that are home to the headquarters of major MEIs. This represents an internationalization of the contentious arena, whereby activists direct their organizing efforts to global gatherings of their targets.

Lastly, our study shows anti-globalization actions were more common during periods that the IMF, World Bank, and WTO were pursuing a highly active international agenda and garnered a great deal of discursive attention – namely, the 1990s and early 2000s. Since then, the neo-liberal project has arguably lost steam and globalization has become less prominent in news media and books. Moreover, after a period of dominance, the global neoliberal order has seen increased scrutiny. Once widely lauded among economists, far fewer scholars are enthusiastic about unfettered free trade and its downsides are now more widely acknowledged (Ostry, Loungani, and Furceri Citation2016; Saval Citation2017; Stiglitz Citation2006)

The durability of the liberal international order has become questionable at best. Nonetheless, the fading enthusiasm for neoliberal globalization has not fueled resurgent protest movements against the IMF, World Bank and WTO. Rather, we see the opposite. Protests against these institutions were far more prevalent during the “golden age” of globalization but fell off dramatically since. Some have argued that a more hostile environment emerged for anti-globalization activists following the 9/11 attacks, leading to a more difficult organizing atmosphere (Wood Citation2014), but others document that 9/11 only caused a brief pause in protest after which global justice protests continued (Podobnik Citation2005). The drop-off in protest against MEIs may also be a case of activists shifting priorities or targets. The World Social Forum, for instance, was conceived by French and Brazilian activists largely as a response to criticisms that protests against MEIs were purely oppositional and lacked a coherent alternative to neoliberalism (Smith Citation2008).

Our findings suggest an additional factor: falling attention to globalization, among the media and broader public, may contribute to the decline of anti-globalization protest. Globalization was, for a time, a phenomenon that captured world attention both among its proponents and detractors. Progressive activists in the 1990s and early 2000s understood globalization and the institutions that sponsored it as preeminent sources of injustice and inequality in the world. As the 2000s and 2010s progressed, other salient issues displaced globalization, such as the US war in Iraq (see Hadden and Tarrow Citation2008), the 2008 global financial crisis, racial justice (e.g., Black Lives Matter), and the rise of the far-right, and activists fixated on new targets. Though neoliberal globalization continues today, albeit at a slower pace, the WTO, IMF, and World Bank – institutions that once dominated global economic affairs – have somewhat faded from the radars of social movement actors.

Acknowledgement

We thank the Jack W. Peltason Center for the Study of Democracy at the University of California, Irvine for supporting this research. We also thank the Editors and anonymous reviewers for extremely helpful comments and suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Arman Azedi

Arman Azedi is a PhD candidate in the Sociology department at the University of California, Irvine. His research focuses on social movements, political sociology, populism, and the Middle East.

Evan Schofer

Evan Schofer is Professor of Sociology at the University of California, Irvine. His research seeks to understand the forces propelling social change on a global scale. Much of his work addresses the influence of international organizations and institutions on national policies and outcomes. More recently, his scholarship addresses populism and other oppositions to globalization. In other work, he examines the global expansions of environmentalism, science, and educational systems, and their effects on society. Much of his work seeks to develop and extend world society theory, to better understand global patterns of social change. His work has appeared in journals including the American Sociological Review, American Journal of Sociology, International Organization, and Social Forces. He received his PhD in Sociology from Stanford University.

Notes

1. The great majority of IMF loans were disbursed to the global South, but some were also given to middle income countries (e.g., in Eastern Europe) that fall within our “West” category. We observed a positive, significant effect of loans on protest in both the industrialized West and global South.

References

- Abouharb, M. Rodwan and David L. Cingranelli. 2006. “The Human Right Effects of World Bank Structural Adjustment, 1981–2000.” International Studies Quarterly 50(2): 233–62. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00401.x.

- Almeida, Paul. 2007. “Defensive Mobilization: Popular Movements Against Economic Adjustment Policies in Latin America.” Latin American Perspectives 34(3): 123–39. doi: 10.1177/0094582X07300942.

- Almeida, Paul. 2014. Mobilizing Democracy: Globalization and Citizen Protest. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Almeida, Paul. 2018. “The Role of Threat in Collective Action.” Ch. 2 in Wiley-Blackwell Companion to Social Movements, 2nd ed., edited by David A. Snow, Sarah A. Soule, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Holly J. McCammon.

- Almeida, Paul and Chris Chase-Dunn. 2018. “Globalization and Social Movements.” Annual Review of Sociology 44(1): 189–211. doi: 10.1146/annurev-soc-073117-041307.

- Almeida, Paul and Mark Lichbach. 2003. “To the Internet, from the Internet: Comparative Media Coverage of Transnational Protests.” Mobilization 8(3): 249–72. doi: 10.17813/maiq.8.3.9044l650652801xl.

- Almeida, Paul and Amalia Pérez Martín. 2022. Collective Resistance to Neoliberalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Amenta, Edwin. 2006. When Movements Matter: The Townsend Plan and the Rise of Social Security. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Autor, David, David Dorn, Gordon Hanson, and Kaveh Majlesi. 2020. “Importing Political Polarization? The Electoral Consequences of Rising Trade Exposure.” The American Economic Review 110(10): 3139–83. doi: 10.1257/aer.20170011.

- Ayers, Jeffrey M. 2004. “Framing Collective Action Against Neoliberalism: The Case of the Anti-Globalization Movement.” Journal of World-Systems Research 10(1): 11–34. doi: 10.5195/jwsr.2004.311.

- Azedi, Arman. forthcoming. “Does Job Insecurity Motivate Protest Participation? A Multilevel Analysis of Working-Age People from 18 Developed Countries.” Sociological Perspectives.

- Babb, Sarah. 2005. “The Social Consequences of Structural Adjustment: Recent Evidence and Current Debates.” Annual Review of Sociology 31: 199–222.

- Baiocchi, Gianpaolo. 2005. “The Workers’ Party and the World Social Forum: Challenges of Building a Just Social Order.” Pp. 83–94 in Transforming Globalization: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-9/11 Era, edited by Bruce Podobnik and Thomas Reifer. Boston: Brill.

- Bédoyan, Isabelle, Peter Aelst, and Stefaan Walgrave. 2004. “Limitations and Possibilities of Transnational Mobilization: The Case of EU Summit Protesters in Brussels, 2001.” Mobilization 9(1): 39–54. doi: 10.17813/maiq.9.1.d599r28j75356jp1.

- Benford, Robert D. and David A. Snow. 2000. “Framing Processes and Social Movements: An Overview and Assessment.” Annual Review of Sociology 26(1): 611–39. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.26.1.611.

- Bergstrand, Kelly. 2014. “The Mobilizing Power of Grievances: Applying Loss Aversion and Omission Bias to Social Movements.” Mobilization 19(2): 123–42. doi: 10.17813/maiq.19.2.247753433p8k6643.

- Biggs, Michael. 2016. “Size Matters: Quantifying Protest by Counting Participants.” Sociological Methods & Research 47(3): 351–83. doi: 10.1177/0049124116629166.

- Boschee, Elizabeth, Jennifer Lauteschlager, Sean O’Brien, Steve Shellman, James Starz, and Michael Ward. 2015. “ICEWS Coded Event Data.” doi: 10.7910/DVN/28075.

- Boyle, Elizabeth. 2002. Female Genital Cutting: Cultural Conflict in the Global Community. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Brady, Henry E., Sidney Verba, and Kay Lehman Scholzman. 1995. “Beyond SES: A Resource Model of Political Participation.” The American Political Science Review 89(2): 271–94. doi: 10.2307/2082425.

- Burchell, Brendan. 1993. “A New Way of Analyzing Labour Market Flows Using Work History Data.” Work, Employment and Society 7(2): 237–58. doi: 10.1177/095001709372004.

- Cameron, J. E. and S. L. Nickerson. 2009. “Predictors of Protest Among Anti-Globalization Demonstrators.” Journal of Applied Social Pscyhology 39(3): 734–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1559-1816.2009.00458.x.

- Caren, Neal, Sarah Gaby, and Catherine Herrold. 2017. “Economic Breakdown and Collective Action.” Social Problems 64(1): 133–55. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spw030.

- Chesters, Graeme and Ian Welsh. 2004. “Rebel Colours: ‘Framing’ in Global Social Movements.” The Sociological Review 52(3): 314–35. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-954X.2004.00482.x.

- della Porta, Donatella, ed. 2007. The Global Justice Movement: Cross-National and Transnational Perspectives. New York, NY: Taylor and Francis.

- della Porta, Donatella. 2015. Social Movements in Times of Austerity: Bringing Capitalism Back into Protest Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley and Sons.

- Dodson, Kyle. 2015. “Globalization and Protest Expansion.” Social Problems 62(1): 15–39. doi: 10.1093/socpro/spu004.

- Dodson, Kyle. 2016. “Economic Threat and Protest Behavior in Comparative Perspective.” Sociological Perspectives 59(4): 873–91. doi: 10.1177/0731121415608508.

- Dreher, Axel. 2006. “Does Globalization Affect Growth? Evidence from a New Index of Globalization.” Applied Economics 38(10): 1091–110. doi: 10.1080/00036840500392078.

- Dreher, Axel and Martin Gassebner. 2012. “Do IMF and World Bank Programs Induce Government Crises? An Empirical Analysis.” International Organization 66(2): 329–58. doi: 10.1017/S0020818312000094.

- Earl, Jennifer, Andrew Martin, John D. McCarthy, and Sarah A. Soule. 2004. “The Use of Newspaper Data in the Study of Collective Action.” Annual Review of Sociology 30(1): 65–80. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110603.

- Evans, Erin M., Evan Schofer, and Ann Hironaka. 2020. “Globally Visible Environmental Protest: A Cross-National Analysis, 1970-2010.” Sociological Perspectives 63(5): 786–808. doi: 10.1177/0731121420908899.

- Fisher, Dana R., Kevin Stanley, David Berman, and Gina Neff. 2005. “How Do Organizations Matter? Mobilization and Support for Participants at Five Globalization Protests.” Social problems 52(1): 102–21. doi: 10.1525/sp.2005.52.1.102.

- Fukuyama, Francis. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. New York: Free Press.

- Gallie, Duncan, Michael R. M. White, Yuan Cheng, and Mark Tomlinson. 1998. Restructuring the Employment Relationship. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Gerhards, Jürgen and Dieter Rucht. 1992. “Mesomobilization: Organizing and Framing in Two Protest Campaigns in West Germany.” The American Journal of Sociology 98(3): 555–96. doi: 10.1086/230049.

- Gillham, Patrick F., Nathan C. Lindstedt, Bob Edwards, and Erik W. Johnson. 2019. “The Mobilizing Effects of Economic Threats and Resources on the Formation of Local Occupy Wall Street Protest Groups in 2011.” Sociological Perspectives 62(4): 433–54. doi: 10.1177/0731121418817249.

- Green, Francis. 2009. “Subjective Employment Insecurity Around the World.” Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 2(3): 343–63. doi: 10.1093/cjres/rsp003.

- Hadden, Jennifer and Sidney Tarrow. 2008. “Spillover or Spillout? The Global Justice Movement in the United States After 9/11.” Mobilization 12(4): 359–76. doi: 10.17813/maiq.12.4.t221742122771400.

- Held, David and Mathias Koenig-Archibugi. 2005. Global Governance and Public Accountability. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Herkenrath, Mark and Alex Knoll. 2011. “Protest Events in International Press Coverage: An Empirical Critique of Cross-National Conflict Databases.” International Journal of Comparative Sociology 52(3): 163–80. doi: 10.1177/0020715211405417.

- Kadivar, Mohammad A. 2017. “Preelection Mobilization and Electoral Outcome in Authoritarian Regimes.” Mobilization: An International Quarterly 22(3): 293–310. doi: 10.17813/1086-671X-22-3-293.

- Keck, M. and K. Sikkink. 1998. Activists Beyond Borders: Advocacy Networks in International Politics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Kern, Anna, Sofie Marien, and Marc Hooghe. 2015. “Economic Crisis and Levels of Political Participation in Europe (2002-2010): The Role of Resources and Grievances.” West European Politics 38(3): 465–90. doi: 10.1080/01402382.2014.993152.

- Kolb, Felix. 2006. “The Impact of Transnational Protest on Social Movement Organizations: Mass Media and the Making of ATTAC Germany.” Pp. 95–120 in Transnational Protest and Global Activism, edited by Sidney Tarrow and Donatella Della Porta. Lanham, Maryland: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Kurer, Thomas, Silja Housermann, Bruno Wuest, and Matthias Enggist. 2019. “Economic Grievances and Political Protest.” European Journal of Political Research 58(3): 866–92. doi: 10.1111/1475-6765.12318.

- Levi, Margaret and Gillian H. Murphy. 2006. “Coalitions of Contention: The Case of the WTO Protests in Seattle.” Political Studies 54(4): 651–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9248.2006.00629.x.

- Lockheed Martin. 2022. “Integrated Crisis Early Warning System (ICEWS).” Lockheed Martin. Retrieved November 19, 2022. (https://www.lockheedmartin.com/en-us/capabilities/research-labs/advanced-technology-labs/icews.html).

- Massoud, Tansa G., John A. Doces, and Christopher Magee. 2019. “Protests and the Arab Spring: An Empirical Investigation.” Polity 51(3): 429–65. doi: 10.1086/704001.

- McAdam, Doug. 1982. Political Process and the Development of Black Insurgency, 1930–1970. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- McCarthy, John D., C. McPhail, and Jackie Smith. 1996. “Images of Protest: Selection Bias in Media Coverage of Washington, D.C. Demonstrations.” American Sociological Review 61(3): 478–99. doi: 10.2307/2096360.

- McCarthy, John D., and Mayer N. Zald. 1977. “Resource Mobilization and Social Movements: A Partial Theory.” The American Journal of Sociology 82(6): 1212–41. doi: 10.1086/226464.

- Meyer, David S. 2004. “Protest and Political Opportunities.” Annual Review of Sociology 30(1): 125–45. doi: 10.1146/annurev.soc.30.012703.110545.

- Meyer, David S. and Sidney Tarrow. 1998. The Social Movement Society: Contentious Political for a New Century. Oxford, England: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Mughan, Anthony, Clive Bean, and Ian McAllister. 2003. “Economic Globalization, Job Insecurity, and the Populist Reaction.” Electoral Studies 22(4): 617–33. doi: 10.1016/S0261-3794(02)00047-1.

- Myers, Daniel J. and Beth S. Caniglia. 2004. “All the Rioting That’s Fit to Print: Selection Effects in National Newspaper Coverage of Civil Disorders, 1968-1969.” American Sociological Review 69(4): 519–43. doi: 10.1177/000312240406900403.

- O’Brien, Karen and Robin M. Leichenko. 2008. “Winners and Losers in the Context of Global Change.” Nature and Society 93(1): 89–103. doi: 10.1111/1467-8306.93107.

- Olzak, Susan. 2006. The Global Dynamics of Racial and Ethnic Mobilization. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Ortiz, David and Sergio Béjar. 2013. “Participation in IMF-Sponsored Economic Programs and Contentious Collective Action in Latin America, 1980-2007.” Conflict Management and Peace Science 30(5): 492–515. doi: 10.1177/0738894213499677.

- Ortiz-Ospina, Esteban and Diana Beltekian. 2014. “Trade and Globalization.” Our World in Data. Retrieved September 25, 2021. (https://ourworldindata.org/trade-and-globalization).

- Ostry, Jonathan D., Prakash Loungani, and Davide Furceri. 2016. “Neoliberalism: Oversold?” Finance & Development June, 38–41.

- Peet, Richard. 2003. Unholy Trinity: The IMF, World Bank and WTO. London: Zed Books.

- Podobnik, Bruce. 2005. “Resistance to Globalization: Cycles and Trends in the Globalization Protest Movement.” Pp. 51–68 in Transforming Globalization: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-9/11 Era, edited by Bruce Podobnik and Thomas Reifer. Boston: Brill.

- Przeworski, Adam and James R. Vreeland. 2000. “The Effects of the IMF on Economic Growth.” Journal of Development Economics 62(2): 384–421. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3878(00)00090-0.

- Quaranta, Mario. 2016. “Protesting in ‘Hard Times’: Evidence from a Comparative Analysis of Europe, 2000–2014.” Current Sociology 64(5): 736–56. doi: 10.1177/0011392115602937.

- Robertson, Graeme B. and Emmanuel Teitelbaum. 2011. “Foreign Direct Investment, Regime Type, and Labor Protest in Developing Countries.” American Journal of Political Science 55(3): 665–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5907.2011.00510.x.

- Rodrik, Dani. 2021. “Why Does Globalization Fuel Populism? Economics, Culture, and Rise of Right-Wing Populism.” Annual Review of Economics 13:133–70.

- Rudra, Nita. 2008. Globalization and the Race to the Bottom in Developing Countries. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Saval, Nikil. 2017. “Globalisation: The Rise and Fall of an Idea That Swept the World.” The Guardian. Retrieved September 25, 2021. (https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/jul/14/globalisation-the-rise-and-fall-of-an-idea-that-swept-the-world).

- Schofer, Evan, Francisco Ramriez, and John W. Meyer. 2021. “The Societal Consequences of Higher Education.” Sociology of Education 94(1): 1–19.

- Smith, Jackie. 2001. “Globalizing Resistance: The Battle of Seattle and the Future of Social Movements.” Mobilization 6(1): 1–19. doi: 10.17813/maiq.6.1.y63133434t8vq608.

- Smith, Jackie. 2002. “Bridging Global Divides?: Strategic Framing and Solidarity in Transnational Social Movement Organizations.” International Sociology 17(4): 505–28.

- Smith, Jackie. 2008. “Promoting Multilateralism: Social Movements and the UN System.” Pp. 89–107 in Social Movements for Global Democracy, edited by Jackie Smith. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Smith, Jackie. 2020. “Making Other Worlds Possible: The Battle of Seattle in World-Historical Context.” Socialism and Democracy 34(1): 114–37. doi: 10.1080/08854300.2019.1676030.

- Smith, Jackie, Scott Byrd, Ellen Reese, and Elizabeth Smythe. 2015. “Introduction: Learning from the World Social Forums.” Pp. 1–10 in Handbook on World Social Forum Activism, edited by Jackie Smith, Scott Byrd, Ellen Reese, and Elizabeth Smythe. New York: Routledge.

- Smith, Jackie, Basak Gemici, Samantha Plummer, and Melanie M. Hughes. 2018. “Transnational Social Movement Organizations and Counter-Hegemonic Struggles Today.” Journal of World-Systems Research 24(2): 372–403. doi: 10.5195/jwsr.2018.850.

- Smith, Jackie, John D. McCarthy, Clark McPhail, and Boguslaw Augustyn. 2001. “From Protest to Agenda Building: Description Bias in Media Coverage of Protest Events in Washington, D.C.” Sociology and Criminology 79(4): 1397–423. doi: 10.1353/sof.2001.0053.

- Smith, Jackie and Ellen Reese. 2008. “Editor’s Introduction: Special Issue on the World Social Forum Process.” Mobilization 13(4): 349–52. doi: 10.17813/maiq.13.4.r57126g147204524.

- Smith, Jackie and Dawn Wiest. 2012. Social Movements in the World-System: The Politics of Crisis and Transformation. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Smythe, Elizabeth. 2015. “Our World is Not for Sale: The World Social Forum Process and Transnational Resistance to International Trade Agreements.” Pp. 166–189 in Handbook on World Social Forum Activism, edited by Jackie Smith, Scott Byrd, Ellen Reese, and Elizabeth Smythe. New York: Routledge.

- Snow, David A. and Robert D. Benford. 1988. “Ideology, Frame Resonance, and Participant Mobilization.” International Social Movement Research 1: 197–218.

- Sommer, Henrik. 1996. “From Apartheid to Democracy: Patterns of Violent and Nonviolent Direct Action in South Africa, 1984-1994.” Africa Today 43(1): 53–76.

- Stiglitz, Joseph. 2006. Making Globalization Work. New York and London: W.W. Norton.

- Stockman, Farah. 2020. “The WTO is Having a Midlife Crisis.” The New York Times. December, 17. Retrieved July 5, 2022. (https://www.nytimes.com/2020/12/17/opinion/wto-trade-biden.html).

- Tarrow, Sidney. 1994. Power in Movement: Social Movements, Collective Action, and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tsutsui, Kiyoteru. 2018. Rights Make Might: Global Human Rights and Minority Social Movements in Japan. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Tsutsui, Kiyoteru and Jackie Smith. 2018. “Human Rights and Social Movements: From the Boomerang Pattern to a Sandwich Effect.” in Pp. 586–601 in Wiley Blackwell Companion to Social Movements Editor, 2nd ed, edited by David Snow, Sarah Soule, Hanspeter Kriesi, and Holly J McCammon. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

- Van Dyke, N. and Soule, S. A. 2002. “Structural Social Change and the Mobilizing Effect of Threat: Explaining Levels of Patriot and Militia Organizing in the United States.” Social Problems 49(4): 497–520. doi: 10.1525/sp.2002.49.4.497.

- Walton, John and Charles Ragin. 1990. “Global and National Sources of Political Protest: Third World Responses to the Debt Crisis.” American Sociological Review 55(6): 876–90. doi: 10.2307/2095752.

- Walton, John and David Seddon. 1994. Free Markets and Food Riots: The Politics of Global Adjustment. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Wood, Lesley. 2005a. “Bridging the Chasms: The Case of Peoples’ Global Action.” Pp. 95–120 in Coalitions Across Borders: Transnational Protest and the Neoliberal Order, edited by Joe Bandy and Jackie Smith. Oxford: Rowman and Littlefield.

- Wood, Lesley. 2005b. “Taking to the Streets Against Neoliberalism: Global Days of Action and Other Strategies.” Pp. 69–82 in Transforming Globalization: Challenges and Opportunities in the Post-9/11 Era, edited by Bruce Podobnik and Thomas Reifer. Boston: Brill.

- Wood, Lesley. 2013. “Anti World Bank and Anti IMF Riots.” in The Wiley-Blackwell Encyclopedia of Social and Political Movements, edited by David A. Snow, Donatella Della Porta, Bert Klandermans, and Doug McAdam. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley Blackwell.

- Wood, Lesley. 2014. Direct Action, Deliberation, and Diffusion: Collective Action After the WTO Protests in Seattle. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wooldrige, Jeffrey N. 2002. Econometric Analysis of Cross Section and Panel Data. London, England: MIT Press.

- World Bank Open Data. 2021. (http://data.worldbank.org/).

- WTO. 2022. “Evolution of Trade Under the WTO: Handy Statistics.” World Trade Organization. Retrieved July 5, 2022. (https://www.wto.org/english/res_e/statis_e/trade_evolution_e/evolution_trade_wto_e.htm).