Abstract

The strong soil–peace link is governed by the need for finite, but essential, resources intricately connected with ecosystem services and functions. Access to adequate and nutritious food is essential to human wellbeing, peace and tranquillity. The relation between soil/environmental scarcity and conflict is complex, and security can only be universal, rather than local or regional, in the present era of globalization. Civil strife and conflict can be caused by both resource paucity and rapacity. Anthropogenic perturbations leading to soil degradation, climate volatility and growing human demands (e.g., food, energy, water, minerals) derived from soil are potential flash points triggering violence at local, regional and global scales. Among different types of drought, pedological and agronomic droughts are triggered by soil degradation, decline in available water capacity of the root zone and changes in the hydrological cycle. Several regions with unstable governments are prone to water scarcity and conflicts. Soil affects world peace through its impact on the quest for victuals, which enhances the relevance of the “Peak Soil” concept. Economic development and environmental enhancement must go hand in hand, and the highest priority must be given to development of the ecosphere. Depicting soil as a work of art for portraying cultural, aesthetical and ecological values can increase public awareness. A Greener Revolution can be ushered in through judicious soil and environmental governance. Maintaining peace and harmony necessitates that soil resources are used, improved, restored and never taken for granted.

INTRODUCTION

The Earth is one, but there are numerous worlds depicting diverse cultures and civilizations. However, soil is the common thread that unites numerous worlds into one Earth through peace and harmony. The term “peace” refers to a state of quiet, tranquillity and security, and a lack of disturbance and violence. It also implies harmony with the environment. Many ancient cultures value and cherish peace by greeting one another through peace-based salutations. The term “Shanti” in Hinduism and Buddhism refers to serenity, calmness and being at mental and spiritual peace rather than being under stress or anxiety. In Hebrew, the word “Shalom” implies peace, prosperity and completeness. In Islam, the greeting “Salaam” means “peace.” The Greek word “Eirene” is widely used in Christianity and Roman philosophy to indicate a state of calmness and tranquillity. Norman Borlaug stated that “If you desire peace, cultivate justice; but at the same time cultivate the fields (soil) to produce more bread; otherwise there will be no peace” (Borlaug Citation1970).

However, peace and tranquillity are being disturbed by drastic perturbation of the environment, inappropriate or excessive use of natural resources and human greed with utter disregard to the needs of the other 8.7 million species cohabiting the planet (Mora et al. Citation2011). Thus, there is a strong link between peace and human demand, both perceived and real. Access to adequate and healthy food is essential to human wellbeing and tranquillity, and is among the major concerns of the twenty-first century. The projected increase in population to 9.7 billion by 2050 and 11.2 billion by 2100 (UN Citation2015) has enhanced the challenges of increasing food production, mitigating climate change and restoring landscapes. The challenges are especially high because of the state of non-renewable resources (), which is being exacerbated by the warming climate, degrading soils, decreasing supply and quality of fresh water resources, dwindling biodiversity, increasing cost of energy, increasing conversion of farm land to urban and industrial uses, and growing preference for a meat-based diet especially in emerging economies (Jacobsen Citation2014). Under the existing state of ~795 million food-insecure people (FAO Citation2015), feeding a growing and increasingly affluent population will be a much bigger challenge. Closely linked with the issues of access to food is the scarcity of essential resources (e.g., land, water, forests, fish, energy). The scarcity can be absolute (finite limits), relative (sub-optimal allocation of resources), or political (lack of access, inequality, power struggle; Scoones et al. Citation2014).

There are two schools of thought regarding resources and human conflicts or peace. One states that resource scarcity can contribute to conflicts, civil unrest and political instability (Klare Citation2001; Mildner et al. Citation2011), because fighting over critical resources (e.g., food, land, water) is a human nature. The proponents of this school of thought argue that the probability of conflict is increased by ecological degradation (; de Cordier Citation1996). It is widely perceived that risks of global conflict are being aggravated in the present era because of resource and environmental scarcity (Homer-Dixon Citation1995). In direct relation to agricultural resources, it is also argued that most conflicts occur in regions with agrarian economies characterized by resource scarcity (de Soysa and Gleditsch Citation1999). For example, the 1994 genocide in Rwanda is linked to the scarcity of arable land and the utter lack of institutional support (Baechler Citation1999). Yet the flashpoint linking conflict and resource scarcity may be ignited by poverty, excessive taxation or environmental scarcity (Le Billon Citation2006). In The wealth of nations, Adam Smith (Citation1776) stated that “Poverty, though it does not prevent the generation, is extremely unfavorable to the rearing of children. The tender plant is produced, but in so cold a soil and so severe a climate, soon withers and dies” (p. 80). Further, it is also hypothesized that changes in population density, deforestation, land degradation and water scarcity all impact the number of battle deaths (Hauge and Ellingsen Citation1998). Shortfall in rainfall can also lead to an increase in armed conflicts (Miguel et al. Citation2004), but an increase in land degradation per se may not (Hendrix and Glaser Citation2007), because its short-term effects may be masked by technological inputs (e.g., fertilizers, irrigation, improved varieties, tillage). There are also confounding effects of population density, soil degradation and water scarcity (Raleigh and Urdal Citation2007), and climate change may aggravate these complexities (Reuveny Citation2007).

Table 1 Views on the resource scarcity-conflict relationship.

The second school believes that resource abundance can lead to conflicts, and calls it the “resource curse” (Collier and Hoeffler Citation1998). The “resource curse” theory states that the abundance of natural resources leads to greed-motivated rebellion (Ross Citation1999). The violence is motivated by rapacity rather than paucity. Webersik (Citation2001) argued that prolonged civil conflicts in Africa are caused not by environmental scarcity but by greed or desire for control over resources. This implies that “the true cause of much civil war is not the loud discourse of grievance but the silent force of greed” (Collier Citation2000; de Soysa Citation2002b). Such may be the case with the civil war in Nigeria over Biafra in the late 1960s. Thus, it is changes in access rather than levels of supply that are the prominent cause of small-scale conflicts, not international and large-scale civil wars (Theisen and Brandsegg Citation2007). A similar opinion was proposed by Jean Bodin (a French philosopher, 1530–1596) regarding soil: “Men of a fat and fertile soil are commonly effeminate and cowards; whereas contrariwise a barren country makes men temperate by necessity, and by consequence careful, vigilante, and industrious” (quoted in de Soysa Citation1999). While the Malthusian theory (Malthus Citation1798, Citation1826) states that the “growth of human population always tends to outstrip the productive capabilities of land resources,” the Boserpian (Boserup Citation1965, Citation1976, Citation1981) concept focuses on technology, especially the agricultural tools and innovations in relation to soil quality and climate. The Boserpian hypothesis states that intensification of agricultural land comes at a cost of labor. Adam Smith (Citation1776) stated that “whatever the soil, climate or extent of territory of any particular nation, the abundance or scantiness of its annual supply must, in that particular situation, depend on the particular circumstances,” or on the skills of its labor (de Soysa Citation2002a, Citation2002b). Floyd (Citation2008) and Johnson et al. (Citation2010) argue that the violence can be caused by: (1) “grievance” because of environmental degradation and scarcity (Homer-Dixon Citation1995), and /or (2) “greed” because of the localized abundance of non-renewable resources and competition to control them (de Soysa Citation2002a, Citation2002b).

Soil, a four-dimensional (length, breadth, depth and time) natural body formed by the transformation of parent material(s) through active (climate, biota, time) and passive (parent material, terrain) factors, is the essence of all terrestrial life through provisioning of numerous ecosystem services and functions. Soil resources are finite, non-renewable over the human time scale, unequally distributed among geographical regions and fragile to drastic perturbations by natural forces and anthropogenic activities (e.g., deforestation, drainage, tillage). Soil is a living entity, a habitat for 8.7 million species, and in dynamic equilibrium with its immediate environment. It is the drastic and rapid disturbance of this delicate equilibrium which leads to degradation [e.g., accelerated erosion by water and wind, salinization, depletion of soil organic matter (SOM) and nutrients, water-air imbalance manifested by drought or inundation, elemental imbalance leading to deficiency or toxicity, and decline in activity and species diversity of soil-based fauna and flora]. Fertile and well-managed soils were the cradle of numerous ancient civilizations (e.g., Mesopotamian, Indus, Mayan, Aztec). Severe soil degradation led to the collapse and extinction of such once thriving and powerful nations ().

Table 2 Collapse of historical civilizations.

The objective of this article is to deliberate on and explore the soil–peace nexus in the context of growing human demands. The importance of soil is presented in terms of the quality of environment, climate and natural resources (water, soil) which affect food production and access.

ENVIRONMENTAL SCARCITY AND PEACE

Any species of a large population (e.g., Homo sapiens) can be a major force in transforming the biosphere. Thus, the term “Anthropocene” was proposed by Crutzen (Citation2002). Humans are ecosystem engineers, use a wide array of powerful tools and as social animals are capable of collective action. Thus, the evolution of human systems had drastic impacts on the environment (). The environment or ecosphere consists of soil, climate, land, water, vegetation, fauna, biodiversity, etc. Soil is an important component of the land and, thus, of the ecosphere. It affects and is affected by the environment, and soil dynamics depend on natural or anthropogenic perturbations in the environment. Thus, environmental degradation leads to soil degradation, and, in severe cases, to civil strife and political unrest by some destabilizing social effects, which can trigger conflict and violence. The term “environmental scarcity” refers to declining availability of renewable natural resources including soil and fresh water supply (Kennedy Citation2001). The scarcity can be demand-induced (an increase in population which caused the genocide in Rwanda in 1994), supply-induced (environmental degradation, such as in Western China, Singhai-Tibet Plateau) or equity-induced (gender or class/caste issues, such as the apartheid regime in South Africa prior to 1990s), or might result from an interaction of these three factors (Kennedy Citation2001). Among specific examples of interaction are: (1) demand-induced × equity-induced, and (2) demand-induced × poverty-driven. The demand × poverty interaction may lead to ecological marginalization forcing a resource-poor population to move into ecologically sensitive ecoregions (e.g., steep lands, tropical rainforests). Examples of ecological marginalization leading to severe environmental degradation include those in sensitive regions such as the Amazon, Himalayan-Tibetan ecoregions, Andean region, Philippines, etc. The schematic linking environmental scarcity with violence is outlined in . Examples of environmental scarcity and conflicts include those in Chiapas (Mexico), Pakistan, Gaza, Rwanda, South Africa, Bangladesh, Senegal/Mauritania, El Salvador/Honduras, Haiti, Peru, the Philippines and the West Bank (Homer-Dixon Citation1994, Citation1996; Percival and Homer-Dixon Citation1998).

Table 3 Evolution of human systems.

Figure 2 Impact of environmental scarcity on decline in soil quality jeopardizing ecosystem functions and services.

In the modern era of globalization,

we cannot achieve security for one state at the expense of another. Security can only be universal, but security cannot only be political or military, it must also be ecological, economic, social, and ensure fulfillment of the aspirations of humanity as a whole. (Tomeshenko Citation1986)

Therefore, economic development and environmental maintenance must go hand in hand, but only by making development of the ecosphere the first priority. Economic goals are myopic, and short-term by nature. Thus, economic development must be secondary, and strictly guided by ecological standards (Rowe Citation1986). Environmental problems in China are an example of achieving economic development without giving a high priority to ecological standards (Liu and Diamond Citation2005). China’s environmental problems are also spilling over into other countries because of globalization. There exists a close link between democracy and environmental degradation. Trustily and rationally implemented, democracy can reduce human-induced environmental degradation [e.g., carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions, nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions, deforestation, soil/land degradation and water pollution; Li and Reuveny Citation2006]. Pope Francis has made many appeals in defense of the environment. In an address to the University of Molise, Italy, Pope Francis (Pullella Citation2014) said:

When I look at America, also my own homeland (South America), so many forests, all cut, that have become land—that can no longer give life. This is our sin, exploiting the earth and not allowing her to give us what she has within her.

CLIMATE VOLATILITY AND PEACE

Being an important and an active factor of soil formation, there exists a strong interaction between soil and climate (Jenny Citation1941; s = f (p (parent), cl (climate), r (relief), o (organism), t (time)…) Climate, an important component of the environment, is also linked with global peace and stability. Climate change is widely recognized as a threat to national and international security (McNeely Citation2011), and countries most vulnerable to climate change are those which have limited capacity to adapt. Historically, climate change has caused violent conflicts and the fall of once thriving civilizations (e.g., Indus Valley). Even during the Roman era, the regional phase of climate degradation in the middle and lower Rhone valley has been attributed to anthropogenic activities including deforestation for intensive cultivation of cereals, olives and wine for export to other parts of the Roman Empire (van der Leeuw Citation2005). Climate change also affects the supply and quality of other resources (e.g., water), and the effects are enhanced by demography (Lautze et al. Citation2005). The present-day climate change (e.g., drought, floods, extreme events), with increasing probability of conflict between farmers and pastoralists, can aggravate the food insecurity which already affects ~842 million people. Food production can be affected by climate change through soil degradation by erosion and soil organic carbon (SOC) mineralization, change in rainfall amount and distribution, frequency of drought and extreme events, and increase in temperature during the flowering/reproductive stage. Climate change can also lead to major changes in fresh water availability and soil quality, thereby increasing the risks of violent conflicts over scarce resources including soil and water (Raleigh and Urdal Citation2007).

The effects of climate change on food security may depend on soil, crops and ecoregions. While effects of global warming may even be positive for C3 plants (e.g., wheat (Triticum aestivum), barley (Hordeum vulgare), oats (Avena sativa), cotton (Gossipium hirsutum), sunflower (Hellianthus annuus), potato (Solanum tuberosum), tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), peanut (Arachis hypogea)) grown in northern latitudes, adverse impacts may likely prevail in C4 crops (e.g., maize (Zea mays), sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum), sorghum (Sorghum bicolor), millet (Pennisetum glaucum), amaranth (Amaranth spp.)). C4 crops are primarily grown in the tropics and sub-tropics where risks are high for the degradation of natural resources, food shortages, and population migration and dislocation (El-Sharkawy Citation2014). In addition to climate-induced food deficit, global warming may also lead to disruptive activities such as demonstrations, riots, strikes, communal conflict, and anti-government and organized rebellion violence (Hendrix and Salehyan Citation2012). Extreme deviations in rainfall variability can significantly impact political conflicts caused by environmental shocks (Theisen Citation2012). Indeed, large-scale intergroup violence in developing countries may be driven by climate change. For example, Burke et al. (Citation2009) hypothesized that warming increases the risk of civil war in Africa, and predicted a roughly 54% increase in armed conflict incidence in sub-Saharan Africa by 2030 due to climate change and increase in temperature. Furthermore, a purely technical/scientific understanding of adaptation is insufficient to cope with the socio-political and human dimensions of climate change (Tänzler et al. Citation2010). Ironically, ill-designed adaptation may even exacerbate the risks of conflict. So, it is important to identify conflict-sensitive approaches along with capacity-development measures (Tänzler et al. Citation2010). Climate change may also have important security implications (Gartzke Citation2012). Thus, strategies to curb climate change should pay specific attention to promoting clean development among middle-income states, because these are also the most conflict-prone states. However, stagnating economic development in middle-income states, caused by efforts to combat climate change, may actually realize the fears of climate-induced warfare (Gartzke Citation2012).

RESOURCE SCARCITY AND CONFLICT

There is a strong similarity between environmental scarcity and resource scarcity, and the relationship between natural resources and conflict is complex, because of the strong interaction with political, social, economic and ecological factors which can create aggressive behavior (Maphosa Citation2012). In general, resources and conflicts are causally linked (Solomon Citation2005), and renewable resources are linked to conflict via scarcity (Koubi et al. Citation2014). Increase in population and growing affluence are increasing resource use and causing scarcity. The per-capita resource scarcity in developing countries can lead to conflicts and destruction, degradation of scarce resources, and destabilization and collapse of a society (Maxwell and Reuveny Citation2000). Quite often, natural resources are not only the motivation but are also used to finance the conflict (Le Billon Citation2010). Conflicts characterized by the specific political economy of natural resources, and vulnerability, may depend on resource-dependence rather than on its scarcity (Le Billon Citation2001). In some situations, it is the resource abundance rather than scarcity which may create conflicts (Koubi et al. Citation2014; also see section on Environmental scarcity and peace). Bretthauer (Citation2014) applied a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis to assess the hypothesis of abundance vs. scarcity and observed that the economic situations of households and the levels of human ingenuity also matter. Specifically, high dependence on agriculture and low levels of tertiary education are important factors affecting local and regional conflicts.

WATER SCARCITY AND PEACE

Water is an important natural resource, and the green water supply (soil-water reserves for crop uptake) is an important factor affecting the vulnerability of crops and pastures to drought and extreme events in a changing and uncertain climate. Several global issues confronting humanity are related to water: desertification, eutrophication, salinization and waterlogging, and water-related conflicts (Falkenmark Citation1990). Water scarcity or drought can be of different types, each with its own potential to trigger conflict or violence: (1) meteorological drought caused by a long-term deficit in rainfall, (2) hydrological drought caused by long-term decline in river/stream flow, (3) pedological drought triggered by soil degradation (erosion) and severe decline in the plant-available water capacity in the root zone, (4) agronomic drought caused by the deficit in crop water requirements at critical stages (flowering and grain-filling) of crop growth, and (5) sociological drought caused by excessive use of water by a community (e.g., for lawn irrigation, recreational uses). These droughts in interaction with other factors (e.g., demographic, ethnic, cultural, religious) can trigger conflicts and violence.

Water scarcity occurs when the demand for fresh water exceeds the available supply. Being both a relative and a dynamic concept, water scarcity can occur at any level of supply and demand, and is strongly governed by prevailing economic policy, planning and management approaches (FAO Citation2012). Judicious management of water to minimize risks of scarcity must be based on a thorough understanding of the basic hydrological processes (FAO Citation2012), which state that water: (1) is a renewable resource (), (2) exists in a continuous state of flux in all phases (solid, liquid, gas), (3) balance is governed by the conservation of mass, (4) links all land units within a watershed, (5) pollution and eutrophication are increased by increase in use intensity, (6) use for human consumption in a judicious and rational manner sustains goods and services of aquatic ecosystems, (7) accounting is essential to any strategy of coping with water scarcity, and (8) audits are important to effective governance (FAO Citation2012). Growing demand for water in agriculture is a major factor in countries with predominantly agricultural economies (e.g., China, India, Egypt, Pakistan). Demand for water must be managed through: (1) reducing water losses, (2) increasing water productivity and (3) precedent reallocation (FAO Citation2012). Especially important is the need to reduce the water demand for irrigated agriculture by enhancing use-efficiency and decreasing losses such as by adopting drip sub-irrigation, deficit irrigation, dryland rice (Oryza sativa) (non-flooded) etc. The strategy is to enhance the green water supply and use efficiency. Specific attention must be placed on decision makers’ response to perceived rather than actual problems, administrative fragmentation, and the lack of a governing body which combines overall overview with overall responsibility (Falkenmark Citation1990).

Sixty percent of the world’s fresh water spans international boundaries. Thus, judicious governance of this water is essential to minimize risks of conflict or “water wars” (Chellaney Citation2013). Several regions with unstable governments are prone to water scarcity (e.g., Africa, Asia, the Middle East), and cross-border water disputes. That is why International Water Law provides a strong legal basis to assure the water rights and continuous use of water by downstream countries. An important example is that between US and Mexico over the Colorado River, which has been successfully resolved through bilateral agreement. Yet conflicts over water have involved states along the Nile Basin in Africa, along the Tigris-Euphrates Basin in the Middle East, and war in the Darfur region of Sudan (Chellaney Citation2013). Such conflicts may become more common as water is used as a weapon when an upstream country denies water to those in downstream areas (Chellaney Citation2013). Water can be a major source of conflict between Israel and its neighbors—Jordan, Palestine, Syria, Lebanon (Hillel Citation1994)—necessitating amicable allocation and prudential cooperation. Yet, thus far, water has not been a major catalyst for war in the Middle East (Haddadin Citation2002). Thus, development of the shared water resources of the Jordan and continuous water use in a program of regional cooperation can bring benefits to all partners (Shuval Citation2000), and must be institutionalized in the interest of peace. In addition, some argue a strong need for a policy shift to water-thrifty and salt-tolerant crops in the Jordan River Basin (Assaf Citation2007). It is important to conceptualize the linkages between hydropolitics and peace (Aggestam and Sundell-Eklund Citation2014).

FOOD AND PEACE

Whereas the “peace–bread” nexus is widely recognized (Granville Citation2010), the importance of the soil–food–peace nexus cannot be overemphasized in the present era of increasing demands, decreasing resources, and warming climate. Norman Borlaug, father of the Green Revolution, stated “let us never forget that the world peace will not be built on empty stomachs or human misery” (quoted in Ortiz Citation2011, p. 6). The Secretary General of the United Nations, Mr. Ban Ki Moon, warned in his message on the World Food Day (June 18, 2014) that “land degradation caused or made worse by climate change is not only a danger to livelihoods but also a threat to peace and stability.” He further noted, “we can avert the worst effects of climate change, produce more food and edge competition over resources by land restoration. We can preserve vital ecosystem services, such as water retention, which protects us from floods and drought.”

Thus, it is appropriate to address the major challenge of achieving sustainable global food security through “leverage points” (West et al. Citation2014). For example, Rehber (Citation2012) addressed food security in the context of four Ss with one F. These complementary and overlapping concepts are security, safety, sovereignty, and shareability of food. Poverty determines the accessibility, and soil quality and its management are important to eradicating the poverty of rural and urban populations. In addition to adequate calories, nutritional security is also important (Swaminathan Citation2014), for which the restoration of degraded soils and especially the SOC pool are essential. Yes, there exists a link between protein and peace (Clemens and Pressman Citation2010). Inadequate food nutrition and water are widely recognized as causes and effects of armed conflict, and hunger and thirst are also cause and effect of poverty and strife (; Clemens and Pressman Citation2010). The link between food and national security has become the cornerstone of foreign policy in many countries. A society can adapt to adverse conditions provided that there is peace and stability, which are essential to extending and preserving agriculture and land use even into marginal and climatically harsh areas (e.g., Israel). On the other hand, political instability and sectoral threats are linked to stagnating agriculture, soil degradation, large yield gaps, declining per-capita land, and land grabbing.

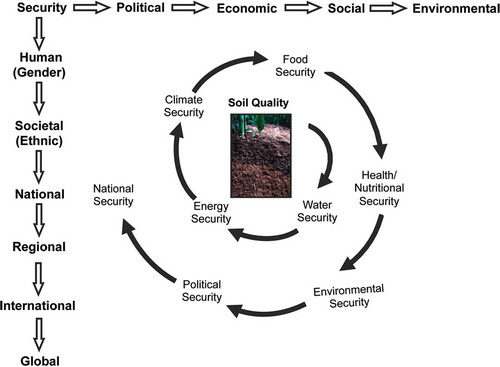

Soil is not just an economic development or an environmental/health concern; it is also a peace and security issue (). Densely populated regions (China, India, etc.) have low and shrinking per-capita arable land area. Scarcity of good-quality soil/land can increase the risk of instability, land grabbing and state failure, and can exacerbate regional and international tensions. Land grabbing, presently estimated at ~200 Mha between 2000 and 2010, can be a future threat to peace and stability. There are about 300,000 specific soil series worldwide. These series are affected by metapedogenesis and anthropedogenesis (e.g., drainage, terracing, erosion).

Figure 4 Securitization of food and the environment through soil sustainability. Updated from Lal (Citation2012).

Public Law 480 (July 10, 1954, Eisenhower) renamed “Food for Peace” (1961, Kennedy), and the Global Food Security Act (Lugar Citation2009) recognized the food–peace nexus. On September 24, 2009, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton made “food security” a key component of US foreign policy and recognized that hunger threatens the stability of governments, societies and borders. US Vice President Biden stated on October 28, Citation2011: “Investments made to ward off food insecurity and prevent its recurrence can prevent the vicious cycles of rising extremism, armed conflict and state failure.”

SOIL AND PEACE

The importance of a strong link between soil health and human health cannot be overemphasized. Indeed, the quality of the surface layer (~30 cm) is the foundation of peace and prosperity, because a degraded and diminished soil also starves ecosystems and creates miseries for those dependent on it. Kaplan (Citation1994) stated appropriately:

It is time to understand the ‘environment’ for what it is: the national security issues of the early 21st century—surging populations, spreading diseases, deforestation and soil erosion, water depletion, air pollution, and possibly rising sea levels—will be the core foreign policy challenges from which most others will ultimately emanate.

Soil–climate–water–biodiversity are interactively linked with peace and tranquillity. Thus, the complex and interactive effects of climate change and environmental scarcity on national security are difficult to separate (Madsen Citation2012; Dabelko et al. Citation2013). Therefore, a Greener Revolution may be ushered in through environmental governance (Agrawal and Lemos Citation2007). The vicious cycle of soil diminishment–hunger/thirst–poverty/domestic tension–weak government–severe soil diminishment () must be broken. In addition to working with environmentalists, soil scientists must also interact with farmers (Carr and Wilkinson Citation2005) to ensure the long-term global availability of food (Koning et al. Citation2008), and with policy makers to promote national security and global peace (Falcon and Naylor Citation2005).

Figure 5 The vicious cycle of soil diminishment, hunger/thirst, poverty and strife. Soil degradation is an “ecological plague” that is impacting several nations in the developing world.

On the other end of the spectrum that impacts foreign policy lies the vision of “soil” in a scientific meaning as an independent work of art (Feller et al. Citation2009), which is also useful to bridge the communication gap and enhance awareness in the general public about the importance of soil. Art can be used to reclaim the image of soil and enhance awareness about its cultural, aesthetical and ecological values (Toland and Wessolek Citation2010). Several essential ecosystem services of soil (e.g., growth medium, habitat, archive, geomembrane, filter of pollutants) are now widely used as a matter of artistic expression and public discourse, and for promoting cultural values (Toland and Wessolek Citation2010; Feller et al. Citation2009). The emerging concept of “Peak Soil” (Leahy Citation2008) is based on the probabilistic model of the Hubbert Curve (Michel Citation2011). Thus, land/soil degradation is an underestimated threat amplifier globally (Schaik and Dinnisen Citation2014), and regionally (Pritchard Citation2013).

CONCLUSION

A healthy soil, being a living entity and the essence of all terrestrial life, is the foundation of peace, prosperity, ecosystem functions and services. Soil scarcity, the lack of access to an adequate area of high-quality soil for provisioning of essential ecosystem services, can lead to civil strife, tensions and violence at local, regional and global scales. Thus, a high priority must be given toward the restoration of degraded soils, protection of soils under natural ecosystems for nature conservancy, transformation of soils of managed ecosystems, and enhancement of resilience against climate change and anthropogenic perturbations (e.g., urban encroachment, competing uses), which is essential to reducing risks of violence and unrest. In addition to soil per se, other resources closely interlinked with it (e.g., water, climate, energy, biodiversity) must also be used judiciously, protected appropriately and conserved meticulously.

Myths about the importance of soil must be replaced by facts through research programs which create a strong and credible database. I wish it could be said that all is known about the soils which support us, but it can’t be. Alas, all interconnectivities and nexuses between soil and ecosphere are not understood. Mechanisms and processes governing soil resilience against climate volatility and anthropogenic perturbations are just beginning to be realized. Communications with policy makers are essential to comprehending the importance of soil to global peace and security. The awareness of the importance of soil by media and the general public must be enhanced regarding the soil–peace nexus. Curricula of grades 2 to 12 must embrace soil as an essential part of basic education.

Yet there lies a bright future for soil science. Through commitment and cooperation with other disciplines and with legislators and policy makers, the International Union of Soil Science (IUSS) can make the dreams of realizing global peace and prosperity through soil management come true.

REFERENCES

- Aggestam K, Sundell-Eklund A 2014: Situating water in peacebuilding: revisiting the Middle East peace process. Water Int., 39, 10–22. doi:10.1080/02508060.2013.848313

- Agrawal A, Lemos MC 2007: A greener revolution in the making? Environmental governance in the 21st century. Environment, 49, 36–45. doi:10.3200/ENVT.49.5.36-45

- Assaf SA 2007: A water for peace strategy for the Jordan River Basin by shifting cropping patterns. In Water Resources in the Middle East, Eds. Shuval H, Dweikm H, pp. 79–85. Springer-Verlag, Berlin.

- Baechler G 1999: Violence through Environmental Discrimination: Causes, Rwanda Arena, and Conflict Model, 321 pp. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht.

- Biden J 2011: Remarks by Vice President Biden at the World Food Program USA Leadership Award Ceremony. https://www.whitehouse.gov/the-press-office/2011/10/24/remarks-vice-president-biden-world-food-program-usa-leadership-award-cer

- Borlaug N 1970: The Green Revolution, Peace and Humanity. Nobel Lecture, Stockholm, December 11, 1970.

- Boserup E 1965: The Conditions of Agricultural Growth: The Economics of Agrarian Change under Population Pressure, 122 pp. Earthscan, New York.

- Boserup E 1976: Environment, population and technology in primitive societies. Popul. Environ. Rev., 2, 21–36.

- Boserup E 1981: Population and Technology Change: A Study of Long-Term Trends, 255 pp. University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

- Boserup E 1990: Economic and Demographic Relationships in Development, 307 pp. John Hopkins Press, Baltimore.

- Bretthauer JM 2014: Conditions for peace and conflict: applying a fuzzy-set qualitative comparative analysis to cases of resource scarcity. J. Conflict Resolut. doi:10.1177/0022002713516841

- Buhaug H, Rød JK 2006: Local determinants of African civil wars, 1970–2001. Polit. Geogr., 25, 315–335. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2006.02.005

- Burke MB, Miguel E, Satyanath S, Dykema JA, Lobell DB 2009: Warming increases the risks of civil war in Africa. Pnas, 106, 20670–20674. doi:10.1073/pnas.0907998106

- Carr A, Wilkinson R 2005: Beyond participation: boundary organizations as a new space for farmers and scientist to interact. Soc. Nat. Resour.: Int. J., 18, 255–265. doi:10.1080/08941920590908123

- Chellaney B 2013: Water, Peace, and War: Confronting the Global Water Crisis, 424 pp. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Lanham, MD.

- Clemens R, Pressman P 2010: Protein and peace: the stabilizing power of food and nutrition. Food Technol., 64, 23.

- Collier P 2000: Rebellion as a quasi criminal activity. J. Conflict Resolut., 44, 839–853. doi:10.1177/0022002700044006008

- Collier P, Hoeffler A 1998: On economic causes of civil war. Oxf. Econ. Pap., 50, 563–573. doi:10.1093/oep/50.4.563

- Collier P, Hoeffler A 2004: Greed and grievance in civil war. Oxf. Econ. Pap., 56, 563–595. doi:10.1093/oep/gpf064

- Crutzen P 2002: Geology of mankind: the Anthropocene. Nature, 415, 23–23. doi:10.1038/415023a

- Dabelko GD, Herzer L, Null S, Parker M, Sticklor R 2013: Backdraft: the Conflict Potential of Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation. Environmental Change and Security Program, ECSP Report 14:2. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/backdraft-the-conflict-potential-climate-change-adaptation-and-mitigation (August 4, 2014).

- de Cordier B 1996: Conflits ethniques et dégradation écologique en Asie centrale. La vallée de Ferghana et le nord du Kazakhstan. Centr. Asian Surv., 15, 399–411. (in French). doi:10.1080/02634939608400959

- de Soysa I 1999: The resource curse: are civil wars driven by rapacity or paucity? In Greed and Grievance: Economic Agendas In Civil Wars, Eds. Berdal MR, Malone D, pp. 113–135. Lynne Rienner, Boulder, CO.

- de Soysa I 2002a: Ecoviolence: shrinking pie, or honey pot? Glob. Environ. Polit., 2, 1–34. doi:10.1162/152638002320980605

- de Soysa I 2002b: Paradise is a bazaar? Greed, creed, and governance in civil war, 1989–99. J. Peace Res., 39, 395–416. doi:10.1177/0022343302039004002

- de Soysa I, Gleditsch NP 1999: To cultivate peace: agriculture in a world of conflict. Environ. Change Sec. Project Rep., 5, 15–25.

- El-Sharkawy MA 2014: Global warming: causes and impacts on agroecosystems productivity and food security with emphasis on cassava comparative advantage in the tropics/subtropics. Photosynthetica, 52, 161–178. doi:10.1007/s11099-014-0028-7

- Etsy DC, Goldstone JA, Gurr TR, Harff B, Levy M, Dabelko GD, Surko PT, Unger AN 1999: State failure task force report: phase II findings. ECSP Rep., 5, 49–72.

- Falcon WP, Naylor RL 2005: Rethinking food security for the twenty-first century. Am. J. Agric. Econ., 87, 1113–1127. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8276.2005.00797.x

- Falkenmark M 1990: Global water issues confronting humanity. J. Peace Res., 27, 177–190. doi:10.1177/0022343390027002007

- FAO 2012: Coping with Water Scarcity: An Action Framework for Agriculture and Food Security. http://www.fao.org/docrep/016/i3015e/i3015e.pdf ( August 4, 2014).

- FAO 2015: The State of Food Insecurity in the World. FAO/IFAD/WFP. FAO, Rome, Italy (ISBN 978-92-5-108785-5), 58 pp.

- Feller C, Chapuis-Lardy L, Ugolini F 2009: The representation of soil in the Western Art: from genesis to pedogenesis. In Soil and Culture, Eds. Landa ER, Feller C, pp. 3–21. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Floyd R 2008: The environmental security debate and its significance for climate change. Int. Spect., 43, 51–65. doi:10.1080/03932720802280602

- Gartzke E 2012: Could climate change precipitate peace? J. Peace Res., 49, 177–192. doi:10.1177/0022343311427342

- Granville J 2010: “Ask for bread, not peace”: reactions of Romanian workers and peasants to the Hungarian Revolution of 1956. East Eur. Polit. Soc., 24, 543–571. doi:10.1177/0888325410376790

- Haddadin MJ 2002: Water in the Middle East peace process. Geogr. J., 168, 324–340. doi:10.1111/j.0016-7398.2002.00059.x

- Hauge W, Ellingsen T 1998: Beyond environmental scarcity: causal pathways to conflict. J. Peace Res., 35, 299–317. doi:10.1177/0022343398035003003

- Hegre H, Sambanis N 2006: Sensitivity analysis of empirical results on civil war onset. J. Conflict Resolut., 50, 508–535. doi:10.1177/0022002706289303

- Hendrix CS, Glaser SM 2007: Trends and triggers: climate, climate change and civil conflict in Sub-Sarahan Africa. Polit. Geogr., 26, 695–715. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.06.006

- Hendrix CS, Salehyan I 2012: Climate change, rainfall, and social conflict in Africa. J. Peace Res., 49, 35–50. doi:10.1177/0022343311426165

- Hillel D 1994: Rivers of Eden: the Struggle for Water and the Quest for Peace in the Middle East, 355pp. Oxford University Press, New York, NY.

- Homer-Dixon TF 1994: Environmental scarcities and violent conflict: evidence from cases. Int. Secur., 19(1), 5–40.

- Homer-Dixon TF 1995: The ingenuity gap: can poor countries adapt to resource scarcity? Popul. Dev. Rev., 21(3), 587–612.

- Homer-Dixon TF 1996: Environmental Scarcity and Violent Conflict: The Case of Chiapas, Mexico. Occasional Paper Project on Environment, Population and Security Washington, D.C.: American Association for the Advancement of Science and the University of Toronto. 42 pp. http://www2.uah.es/tiscar/Complem_EIA/Chiapas.pdf ( August 4, 2014).

- Jacobsen R 2014: Has mean met its match? Ensia, Summer, 2014, 8–15.

- Jenny H 1941: Factors of Soil Formation, 281 pp. McGraw Hill, New York, NY.

- Johnson VCA, Floyd R, Fitzpatrick I, White L 2010: What is the Evidence that Scarcity and Shocks in Freshwater Resources Cause Conflict Instead of Promoting Collaboration? Systematic Review No. 10010. Collaboration for Environmental Evidence 23pp. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk/PDF/Outputs/SystematicReviews/nef_conflict_cooperation_protocol_221110.pdf (June 18, 2015).

- Kaplan RD 1994: The coming anarchy. http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1994/02/the-coming-anarchy/304670/ ( August 4, 2014).

- Kennedy B Jr. 2001: Environmental Scarcity and the Outbreak of Conflict. http://www.prb.org/Publications/Articles/2001/EnvironmentalScarcityandtheOutbreakofConflict.aspx ( August 4, 2014).

- Ki-moon B 2014: Secretary General's message for 2014. World Day to Combat Desertification, 17 June 2014.

- Klare MT 2001: The New Geography of Conflict. Foreign Affairs, 80 http://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/57030/michael-t-klare/the-new-geography-of-conflict ( August 4, 2014).

- Klare MT 2013: Tomgram: Michael Klare, The Coming Global Explosion. http://www.tomdispatch.com/blog/175690/ ( August 4, 2014).

- Koning NBJ, Van Ittersum MK, Becx GAet al. 2008: Long-term global availability of food: continued abundance or new scarcity? NJAS - Wageningen J. Life Sci., 55, 229–292. doi:10.1016/S1573-5214(08)80001-2

- Koubi V, Spilker G, Böhmelt T, Bernauer T 2014: Do natural resources matter for interstate and intrastate armed conflict. J. Peace Res., 51, 227–243. doi:10.1177/0022343313493455

- Lal R 2012: World Soils and the Carbon Cycle in Relation to Climate Change and Food Security. Global Soils Week, Issue Paper, 52pp. http://www.ibrarian.net/navon/paper/World_Soils_and_the_Carbon_Cycle_in_Relation_to_C.pdf?paperid=18849413 ( June 18, 2015).

- Lautze J, Reeves M, Vega R, Kirshen P 2005: Water allocation, climate change, and sustainable peace: the Israeli Proposal. Water Int., 30, 197–209. doi:10.1080/02508060508691860

- Le Billon P 2001: The political ecology of war: natural resources and armed conflicts. Polit. Geogr., 20, 561–584. doi:10.1016/S0962-6298(01)00015-4

- Le Billon P 2006: Fatal transactions: conflict diamonds and the (anti)terrorist consumer. Antipode, 38, 778–801. doi:10.1111/anti.2006.38.issue-4

- Le Billon P 2010: Oil and armed conflicts in Africa. Afr. Geogr. Rev., 29, 63–90. doi:10.1080/19376812.2010.9756226

- Leahy S 2008: Peak soil: the silent global crisis. Earth Island Journal. http://stephenleahy.net/2008/09/14/peak-soil-the-silent-global-crisis/ ( August 19, 2014).

- Li Q, Reuveny R 2006: Democracy and environmental degradation. Int. Stud. Quart., 50, 935–956. doi:10.1111/isqu.2006.50.issue-4

- Liu J, Diamond J 2005: China’s environment in a globalizing world. Nature, 435, 1179–1186. doi:10.1038/4351179a

- Lugar D 2009: Lugar-Casey Food Security Act, March 31, 2009. http://thomas.loc.gov/cgi-bin/query/z?c111:S.384 ( June 18, 2015).

- Madsen EL 2012: Afghanistan, Against the Odds: A Demographic Surprise. Environmental Change and Security Program, ECSP Report 14:1. http://www.wilsoncenter.org/publication/afghanistan-against-the-odds-demographic-surprise-0 ( August 4, 2014).

- Malthus C 1798: An Essay on the Price of the Principle of Population. J Johnson, 148 pp. St. Paul’s Churchyard, London, UK.

- Malthus T 1826: An Essay on the Principle of Population, 430 pp. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge.

- Maphosa SB 2012: Natural resources and conflict: Unlocking the economic dimension of peace-building in Africa. Aisa Policy Brief, 74, 1–8.

- Maxwell JW, Reuveny R 2000: Resource scarcity in developing countries. J. Peace Res., 37, 301–322. doi:10.1177/0022343300037003002

- McNeely JA 2011: Climate change, natural resources, and conflict a contribution to the ecology of warfare. In Warfare Ecology, Eds. Machlis GE, Hanson T, Špirić Z, McKendry JE, pp. 43–53. Springer, Dordrecht.

- Michel B 2011: Oil production: A probabilistic model of Hubbert curve. Appl. Stochastic Models Bus. Ind., 27, 434–449. doi:10.1002/asmb.851

- Miguel E, Satyanath S, Sergenti E 2004: Economic shocks and civil conflict: an instrumental variables approach. J. Polit. Econ., 112, 725–753. doi:10.1086/jpe.2004.112.issue-4

- Mildner SA, Lauster G, Widni W 2011: Scarcity and abundance revisited: A literature review on natural resources and conflict. Int. J. Conflict Viol., 5, 155–172.

- Mora C, Tittensor PE, Adl S, Simpson AGB, Worm B 2011: How many species are there on earth and ocean? Plos Biol, 9. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.1001127

- Ortiz R 2011: Revisiting the green revolution: seeking innovations for a changing world. Chronic Horticult., 51, 6–11. doi:10.1016/j.scienta.2011.09.020

- Percival V, Homer-Dixon TF 1998: Environmental scarcity and violent conflict: the case of South Africa. J. Peace Res., 35, 279–298. doi:10.1177/0022343398035003002

- Pritchard MF 2013: Land, power and peace: tenure formalization, agricultural reform, and livelihood insecurity in rural Rwanda. Land Use Policy, 30, 186–196. doi:10.1016/j.landusepol.2012.03.012

- Pullella P 2014: Pope calls exploitation of nature a sin of our time. http://uk.reuters.com/article/2014/07/05/uk-pope-environment-idUKKBN0FA0BC20140705

- Raleigh C, Urdal H 2007: Climate change, environmental degradation and armed conflict. Polit. Geogr., 26, 674–694. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.06.005

- Rehber E 2012: Food for thought: “four Ss with one F”: security, safety, sovereignty, and Shareability of food. Br. Food J., 114, 353–371. doi:10.1108/00070701211213465

- Reuveny R 2007: Climate change-induced migration and violent conflict. Polit. Geogr., 26, 656–673. doi:10.1016/j.polgeo.2007.05.001

- Ross ML 1999: The political economy of resource curse. World Polit., 51, 297–322. doi:10.1017/S0043887100008200

- Rowe S 1986: Saskatchewan Environmental Society. WCED Public Hearing, Ottawa, 26–27 May 1986.

- Schaik LV, Dinnisen R 2014: Terra incognita: Land Degradation as Underestimated Threat Amplifier. Netherland Institute of International Relations, Clingendael Report http://www.clingendael.nl/sites/default/files/Terra%20Incognita%20-%20Clingendael%20Report.pdf ( August 4, 2014).

- Scoones I, Smalley R, Hall R, Tsikata D 2014: Narratives of scarcity: Understanding the ‘global resource grab’. PLAAS Working Paper 076 http://www.plaas.org.za/plaas-publication/FACwp76 ( August 4, 2014).

- Shuval HI 2000: Are the conflicts between Israel and her neighbors over the waters of the Jordan river basin an obstacle to peace? Israel-Syria as a case study. Water Air, Soil Pollut., 123, 605–630. doi:10.1023/A:1005285504188

- Simon JL 1989: Lebensraum: paradoxically, population growth may eventually end wars. J Conflict Resolut, 33, 164–180. doi:10.1177/0022002789033001007

- Smith A 1776: The Wealth of Nations: Nature and Causes. A Landmark Classic, 1264 pp. Thrifty Book, Blacksburg, VA.

- Solomon R 2005: Compare How the Supply and the Scarcity of Natural Resources Influences the Conduct of Contemporary Conflict. IR5001, http://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/itsold/papers/public/miscellaneous/printingproblems/Draft%205.doc ( August 4, 2014).

- Suhkre A 1997: Environmental degradation, mitigation, and the potential for violent conflict. In Conflict and the Environment, Ed.. Gleditsch NP, pp. 255–272. Kluwer Academic, Dordrecht.

- Swaminathan MS 2014: Zero hunger. Science, 345, 491–491. doi:10.1126/science.1258820

- Tänzler D, Maas A, Carius A 2010: Climate change adaptation and peace. Adelphi, 1, 741–750.

- Theisen OM 2008: Blood and soil? Resource scarcity and internal armed conflict revisited. J. Peace Res., 45, 801–818. doi:10.1177/0022343308096157

- Theisen OM 2012: Climate clashes? Weather variability, land pressure, and organized violence in Kenya, 1989–2004. J. Peace Res., 49, 81–96. doi:10.1177/0022343311425842

- Theisen OM, Brandsegg KB 2007: The Environment and Non-State Conflicts. International Studies Association 48th Annual Convention, Chicago, Illinois, 28 February 2007.

- Tiffen M, Mortimore M, Gichuki F 1994: More People, Less Erosion: environmental Recovery in Kenya, 309 pp. ACTS Press, Kenya.

- Toland AR, Wessolek G 2010: Soil art: bridging the communication gap. In Berliner Geographische Arbeiten 117; Boden des Jahres 2010 – Stadtböden, Eds. Makki M, Frielinghaus M, pp. 126–134. Humboldt Universität, Berlin.

- Tomeshenko AS 1986: Institute of State and Law. USSR Academy of Sciences, WCED Public Hearing, Moscow, 11 December 1986.

- UN 2015: World Population Prospects: Key Findings and Advances Tables, 2015 Revision. Department of Economics and Social Affairs, Population Division. ESA/P/WP. 241, New York, USA, 60 pp.

- Urdal H 2005: People vs. Malthus: population pressure, environmental degradation, and armed conflict revisited. J. Peace Res., 42, 417–434. doi:10.1177/0022343305054089

- Urdal H 2008: Population, resources, and political violence: a subnationals study of India, 1956−2002. J. Conflict Resolut., 52, 590–617. doi:10.1177/0022002708316741

- van der Leeuw SE 2005: Climate, hydrology, land use and environmental degradation in the lower Rhone Valley during the Roman period. CR Geosci., 337, 9–27. doi:10.1016/j.crte.2004.10.018

- Webersik C 2001: Reinterpreting environmental scarcity and conflict: evidence from Somalia. Paper presented at the 4th Pan-European International Relations Conference 8–10 September 2001, Canterbury, UK. http://www.mbali.info/doc347.htm ( August 4, 2014).

- West PC, Gerber JS, Engstrom PM et al. 2014: Leverage points for improving global food security and the environment. Science, 345, 325–328. doi:10.1126/science.1246067