At a coffee shop in my neighborhood, I overhear one man say to another, “Everyone has an inheritance story to tell, their own or somebody else’s.” I walk home with that thought. At home, I read Alexander Chee’s essay, “Inheritance.”Footnote1 Chee (Citation2018) wrote about several of the things he inherited since childhood, none of which he actively sought, waited for, or had known in advance. For example, at the age of 18, he inherited a trust fund from his late father’s estate. Writing about this trust fund, he describes what he did with it and what it did for him. With it, he paid for his tuition, bought a car, and covered some dental and health expenses. “I used that money not just for my tuition costs,” he wrote, “but to turn myself from a student into a writer” (p. 177). In his essay, it is not the monetary value of the trust fund on which he reflects. Rather, what is of interest to Chee is how the trust fund (his inheritance), when put to work in a particular manner, animated a form of life, a way of occupying the world, that permitted him to bring aspects of that world to others through his writing and teaching.

In directing our attention to what this inheritance did for him and what he, in turn, did with it, Chee quickly establishes that an inheritance is more than a self-contained form that remains intact as it is passed from one person to another, from one generation to the next. Instead, it shows up and appears in the uses to which it is put. And, for the most part, it carries with it certain hopes and expectations as well as obligations and responsibilities. Like the epigraph above from Seamus Heaney’s poem, “The Settle Bed” (Citation2014), Chee’s essay reveals, “[W]hatever is given/Can always be reimagined.” In large part, his essay offers several insights into the nature of inheritance, both as a concept and as a practice. It suggests that an inheritance can encourage one to imagine and pursue a way of life that seems unattainable without it, and entertain possibilities for actions that might not otherwise be possible.

For Chee, while his inheritance could never bring his father back, and while it reminded him of what he had lost and of what had to pass for something else to come about, his inheritance enabled something else to occur. Also, as his account reveals, an inheritance can generate feelings of accountability, responsibility, obligation, even dread and anxiety, as well as hypervigilance. One feels obliged to do something with an inheritance; to use it well, to put it to good use. On other occasions, depending on the circumstances of giving and receiving and the perceived value of what is given or denied, an inheritance can generate feelings of disappointment, of envy, of being undervalued, or not being valued at all. “Nothing destroys a family like an inheritance,” wrote Chee (Citation2018, p. 179). And yet an inheritance carries with it a sense of hope for a time yet to come, a possibility, or a potentiality even.

As I walked home thinking about what I had overheard at the coffee shop, I began to think about how inheritance plays a critical role in how the field of art education, a finite field, continues. And how inheritance also plays a critical role in the forms that art education takes. As educators, scholars, researchers, and art practitioners, we inherit things from working in the field. We inherit things from the times in which we are working. But, you might ask, what do we inherit? When do we inherit? How do we inherit? What do we do with the things we inherit? To what extent are the things we believe in, work for, or rally against inherited from the field of art education or adjacent fields?

It seems to me that these are some of the questions and concerns that guide the authors and articles in this issue of Studies in Art Education, even if they are not posed or articulated in the same manner in which I have presented them here. These questions and concerns permeate and seep through the four research articles, two media reviews, and one commentary in this first issue of volume 61. Without declaring it, the contributions to this issue seem to say that it is not easy to articulate precisely what weFootnote2 inherit in and from the field. But they suggest that we inherit much. Perhaps one might say we inherit ways of doing and saying, ways of seeing and thinking, modes of inquiry and representation, means of evaluation, judgment and discernment, practices of framing and sense making, and ways of organizing and representing thought that contribute to the field’s distinctiveness and give it, to some degree, character.

Of course, in the field of art education, we inherit a host of obligations, responsibilities and values, and titles and rituals and offices. We inherit ways of working with and for others. From others, those who have gone before us and those who currently surround us, we inherit histories of the field; multiple histories, and accounts of how those others contributed to its advancement that are animated anew by our arrival and our interest. We inherit paradigms and principles, ways of establishing what is relevant to know and do at a given time. We inherit sets of texts and the ideas contained within them along with the ideas that emerge in the act of reading them. Perhaps we also inherit the expectations that others might have for how we ought to spend our time in the field and the types of investments we should make. Thus, our inheritance comes to us as we participate in the field. And, much like Chee, we inherit without being told what to do with what we receive and with what shows up and becomes possible through our involvement in the field. Thus, an inheritance is not given inasmuch as it is achieved in its interpretation.

To be actively engaged in the field of art education is, it seems, to be in relation, at all times, to what the field offers and bequeaths. Some might argue though that to acknowledge our inheritances and to work with them renders possible the reproduction of the field, most especially the reproduction of some of its exclusionary and oppressive aspects. But, one could also say, as Heaney’s epigraph above reminds us, “[W]hatever is given/Can always be reimagined.” Equally, while an inheritance can be given to make something else possible, something decided in advance, it does not follow that what is hoped for will be realized or actualized.

For instance, in his book, Returning to Reims (Citation2013), Didier Eribon reflects on his escape from his inheritance—his family, the working-class environment into which he was born, his father’s deep-seated homophobia, and the culture of homophobia in the larger milieu in which he had grown up. His escape to Paris, the big city, from a small provincial city, Reims, and from a form of life that his family and the environment of his youth had imagined for him in order “to live out [his] homosexuality” and to learn “what it means to be gay by discovering the gay world that already exists, inventing himself as gay on the basis of that discovery” (p. 29) put him in contact with another form of life with its own inheritances and expectations, just as his escape to Paris to become an intellectual and writer did. By refusing the inheritance into which he was born, Eribon intended to interrupt the logic that “the places allocated to us [in society] have been defined and delimited by what has come before us: the past of the family and the surroundings into which we are born” (p. 53).

All contributions to this issue share in common their concern for the types of educative experiences created and curated in art teacher education programs in the United States and in the practice of educational research more generally—these experiences and practices that are imagined and inherited to a degree, but that can also be thought otherwise. The opening article, titled “Educating for Social Change Through Art: A Personal Reckoning,” was first delivered by its author, Dipti Desai, as the 2019 Studies in Art Education Lecture at the National Art Education Association (NAEA) Convention in Boston, Massachusetts. Desai uses the opportunity to write and deliver her article to critically reflect on the commitments she has made, the actions she has taken, and the frameworks for understanding that she has inherited, worked with, and worked against as a social justice educator, activist, and director of the Art and Education Program at New York University (NYU) over the past several years. Aware that the concepts and categories of social justice art education, social change, activism, and art are, to a large extent, inherited ones, in her article, Desai interrogates, in particular, “the classificatory lens and logics of social justice art education.” As she explains, in becoming a scholar, activist, and educator, and in living her life in and between these different commitments and modes of identification and action, she has inherited and taken up certain assumptions about seeing, doing, acting, and talking that are also shaped by her social position, location, and history.

Attending to some of the assumptions, obligations, expectations, demands, and fantasies of social justice art education, which one tends to inherit when one commits to this vision of education in and through art, Desai shares examples of projects, events, art activist interventions, and happenings that she and her students at NYU initiated and led. She shares accounts of these projects, not with the purpose of providing examples of social practice art and education projects, but more as opportunities to think through what these projects were doing in their actualization, oftentimes refusing an inheritance that would frame them as this or that type of project. Describing the nature of her engagement with students as collective pedagogy, Desai reminds us that practices of working with materials, ideas, situations, and places and with a commitment to organizing and building alliances, all with the intent of extending what previously was considered a limit, that art processes and artworks bring about a particular form of consciousness of local, national, and global issues. In many respects, if one replaces the word art in the following statement by the artist Ernesto Pujol (Citation2012) with the word education, Pujol’s statement points to some of the commitments that Desai perhaps seeks to honor in her article: “It takes the passage of time, sometimes a lifetime, for an art practice to mature, to know itself, to reveal its secret depths and complexities… ” (p. 9).

In “Holding Paradox: Activating the Generative (Im)possibility of Art Education Through Provocative Acts of Mentoring With Beginning Art Teachers,” the second article in this issue, Christina Hanawalt and Brooke Anne Hofsess, both of whom identify as art teacher educators, take their reader inside their collaborative and experimental arts-based inquiry of mentoring practices with becoming and beginning art teachers. Rather than assume the position of the all-knowing and all-telling educator with solutions ready at hand to answer the questions of becoming and beginning teachers or to quell their concerns, for this study, Hanawalt and Hofsess conceptualized and staged a number of discrete events, happenings, and projects. It was these events, happenings, and projects within which questions and concerns emerged that had to do with the experience of living a teaching life while negotiating inherited expectations embedded in certain traditions and images of teaching.

Departing from inherited ways of engaging with and studying mentoring practices without dismissing such practices, Hanawalt and Hofsess’s study contributes novel insights and models of mentoring practice to an already large body of literature on this subject. Their intention, they write, is “to envision an alternative approach to mentoring beginning art teachers.” And this is what they achieve in their study by becoming unfaithful to inherited frameworks for thinking, inquiring into, and representing mentoring relationships. Further, the forms of mentoring that arose in this study seemed possible or imaginable only within the milieu of an arts-based inquiry. Their findings, which they refer to as sparks, “to emphasize the tentative shifting and relational qualities” of what they came to observe and understand, reveal how expectations and responsibilities of becoming and beginning teachers, which are inherited by assuming the position of teacher and art teacher in particular, show up in conversations, in attempts to make art and respond to researchers’ prompts, as well as in acts of figuring out ways to live a teaching life.

Joy G. Bertling and Tara C. Moore’s article, titled “U.S. Art Teacher Education in the Age of the Anthropocene,” shares outcomes from a large-scale national study that was motivated by the authors’ desire to gather data that reveal the extent to which “ecological/environmental art pedagogies” feature (and are supported) in teacher education programs in the United States. Through their study, the authors seek to establish the extent to which becoming art teachers are encouraged to think critically and imaginatively about how art education can function as a unique force for addressing some of the ecological and environmental challenges that we face at the current time. The ecological and environmental conditions that we have inherited, and to which we contribute by the choices we make in the lives that we live, can, as the article suggests, be reimagined, and art education, according to the authors, has a critical role to play in that reimagining process. Drawing on inherited understandings of what art can do, Bertling and Moore argue that art education is uniquely positioned to extend and deepen ecological literacies.

Jaehan Bae’s article shares outcomes from a study of how the Educative Teacher Performance Assessment (edTPA) informs and shapes the curriculum and pedagogical choices and practices of 10 art educators working in public universities in the state of Wisconsin. Now used in more than 800 teacher education programs across 41 states and the District of Columbia (Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity, Citation2019), the edTPA is a performance-based subject-specific assessment, developed by Stanford University faculty and staff at the Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity (SCALE). For the administration and scoring of the assessment, SCALE has partnered with Pearson Education, Inc. As an art educator who prepares his students to take the edTPA, Bae is very familiar with some of the challenges and limitations as well as with the educative possibilities of this inherited assessment tool and process. His experience of working with the edTPA process seems to have motivated this study, in which he invites other art teacher educators to reflect on their experiences (positive and negative) of this assessment tool and process. The invitation to participants to reflect on how the edTPA influences and animates their work with becoming teachers brought them face-to-face with their beliefs, values, expectations, and fantasies concerning teacher education and teacher practice, which are most likely inherited from what they have come to understand through their research and study as well as through their current and past experiences of teaching and being taught. Bae’s article offers much-needed research on how the edTPA is being understood and adopted within the field of art education, and it adds to an emerging body of scholarship in the field that critically engages with the edTPA and its effects on art teacher education.

Two book reviews appear in this issue, one written by Shari L. Savage and the other by Dana Carlisle Kletchka. Savage offers a review of Terry Barrett’s most recent book, Crits: A Student Manual, while Kletchka reviews Olga Hubard’s 2015 book, Art Museum Education: Facilitating Gallery Experiences. Both reviews, and by implication both books, remind us of the central role that the studio critique and the museum visit play in our experience of becoming educated in art. Both reviews also remind us that, while we inherit these forms of pedagogy and sites of education from past art educational practices, they remain relevant and valuable for art learning and teaching today. In working with these inherited forms, but in doing something with them that honors the circumstances of the present, something else is revealed about the way in which the “crit” and the museum visit offer distinct opportunities for learning to live well in the world in the company of art. Both reviews reminded me of my own experience of these two forms of art education pedagogy and sites of learning. During my elementary education in Ireland in the mid-1980s, the “crit” and museum visits formed a critical component of my art education, especially in the senior years of elementary school. Both were valued and valuable pedagogical events and sites of education.

This issue ends with a commentary written by Angela M. La Porte. Like the other authors in this issue, La Porte is curious about what informs, regulates, and shapes educators’ decision-making processes regarding curriculum content and pedagogical approaches as they work with and respond to the singularity of each student in their classes and within systems of education that demand particular forms of accountability. Influenced by Dewey’s (Citation1938) writings, especially his ideas concerning experience and what experience does, La Porte encourages readers to be vigilant of the types of experiences that are typically made available to becoming teachers during their preparation. She argues, “Preservice teacher programs should diversify the educational experiences they offer students” and seek to complicate inherited understandings of inclusion and disability. For her, both concepts require more situated and in-depth study that is not bound by how the concepts have been theorized in the past and thus passed on. In her commentary, La Porte shares an account of her work with becoming teachers at the University of Arkansas, where she has developed a pedagogical approach, an orientation to learning and teaching in educational sites that she calls “inverse inclusion.” She explains, “Inverse inclusion is an experience where preservice teachers rotate among multiple roles in a community-based service learning course, learning as a student alongside people with disabilities, as an art teacher, as a teacher’s assistant, and as an observer.” Critically engaging her students with some of the biases that they may carry with them about disability and inclusion, La Porte argues, “Inverse inclusion experiences offer transformative possibilities in art teacher education, moving education away from prescribed illusions and biases that often surround disability and inclusion praxis.” Her commentary reminds me of Chee’s argument that what we do with our inheritance matters for what it can animate and bring about.

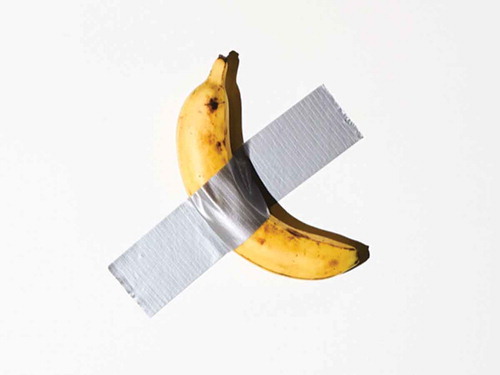

With this issue, I begin my 2-year term as senior editor, and in doing so, I would like to take this moment to acknowledge those who have gone before me and from whom I have inherited this responsibility and opportunity. Through their work (writing, reviewing, and editing manuscripts for the journal), they have ensured that Studies in Art Education has become the journal that it is today, with its distinguished reputation and history. Most especially, I want to extend my deepest thanks to B. Stephen Carpenter II, who mentored me into this role with utmost thoughtfulness, encouragement, and gentleness. Working closely with him over the past 2 years, I observed his unparalleled commitment to authors, which he enacted with remarkable grace and wisdom. My thanks to Amy Barnickel, assistant editor, with whom I also had the good fortune to work closely over the past 2 years and with whom I will continue to work with during the next 2. Amy’s generosity is remarkable; her knowledge of all and every aspect of Studies is second to none. For the support that she has offered me in my transition into this role, I am most grateful. To the new associate editor, Robert W. Sweeny, I extend my gratitude and appreciation for his generous support and good counsel. I look forward to the editorial work that we will do together over the coming 2 years. Kryssi Staikidis and Ryan M. Patton have also joined the editorial team as the commentary editor and the media review editor, respectively. I very much appreciate the opportunity to work with them as we create conditions for critical engagement with ideas that matter and conversations with and between texts, scholars, and inherited modes of narrating the field. To the members of the Editorial Advisory Board, past and current, for your work in assisting authors in the development and representation of their ideas, thank you. And to Janice Hughes and the publications team at the NAEA office as well as the production team at Taylor & Francis, most notably, Nathan Clark, I extend my thanks. You do a significant amount of invisible work during the production and publication process. Finally, my thanks to photographer, Rhona Wise, for granting us permission to use her photograph of Maurizio Cattelan’s conceptual work, Comedian, on the front cover of this issue of Studies in Art Education. My thanks also to the artist Maurizio Cattelan and the Perrotin Gallery for permitting us to include an image of the artwork, which was shown at Art Basel Miami Beach in early December 2019. It has been described as the most talked about artwork of 2019. When I first encountered Comedian and, subsequently, as I followed the media coverage that it generated, along with the responses and reactions of the public toward it, including New York-based performance artist, David Datuna, eating part of it, I could not not think of how inheritance shows up and works in the art world—in the making of art and the writing about it—intentionally or otherwise. It is unlikely that any art educator can view Cattelan’s Comedian without being reminded of Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)—a work that was produced a century ago. Perhaps one work animates the other anew. But, neither are determined by nor reducible to each other.

In closing, I should say that my title for this editorial, “Inheriting Art Education,” is offered neither with the belief nor with the intention of suggesting that art education is easily achieved, assumed, or adopted. I am not suggesting that the field is available and ready for the taking in a coherent, cohesive, and easily understood form. There is never one single inheritance bequeathed to all. Indeed, each contribution to this issue confirms this. In working with what they inherit, the authors of the articles that follow do not simply repeat it, but rather, they think it anew, channeling it into other thought spaces and actions. What they inherit makes them hospitable to ideas that are thought in ways not considered previously. Thus the contributions to this issue show that we should never feel bound by what we inherit. Nor should we feel obliged to remain faithful to it. To remain faithful to what we inherit is to be unfaithful to its intentions, wishes, and hopes for a time yet to come.

1. Maurizio Cattelan. Comedian, Citation2019. Banana, duct tape. Courtesy of Maurizio Cattelan and Perrotin.

Notes

1 This essay appears in Alexander Chee’s most recent book, How to Write an Autobiographical Novel: Essays (Citation2018). I wish to thank my friend Dr. Alyson Hoy who recommended this book of essays to me.

2 In my use of the pronouns “we” and “us,” I am referring to educators, scholars, and researchers who identify as art educators, but I am not assuming that they think, do, and act in the same manner; share the same curiosities; or subscribe to the same intellectual tradition and histories.

REFERENCES

- Chee, A. (2018). How to write an autobiographical novel: Essays. New York, NY: Mariner Books.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York, NY: MacMillan.

- Eribon, D. (2013). Returning to Reims (M. Lucey, Trans.). Pasadena, CA: Semiotext(e).

- Heaney, S. (2014). Seamus Heaney: New selected poems, 1988–2013. London, England: Faber and Faber.

- Maurizio, Cattelan. (2019). Comedian, Banana, duct tape. Courtesy of Maurizio Cattelan and Perrotin.

- Pujol, E. (2012). Sited body, public visions: Silence, stillness and walking as performance practice. New York, NY: McNally Jackson Books.

- Stanford Center for Assessment, Learning and Equity. (2019). About edTPA. Retrieved from https://scale.stanford.edu/teaching/edtpa