ABSTRACT

Many countries in the Mediterranean region face the enormous challenge of conserving detached mosaics abandoned in storage for decades without any re-backing support and with only their facings to hold the tesserae in place. As part of the MOSAIKON initiative's technician training courses, sustainable techniques have been developed to address this problem, providing national authorities with the skills and knowledge to begin to provide proper long-term storage for the significant backlog of detached mosaics under their care. Mosaics in storage at the sites of Volubilis in Morocco and Sidon in Lebanon have provided the opportunity to develop new documentation and treatment methodologies. Low–cost techniques were sought using purpose-built, locally-constructed shelving structures and lime-based mortar re-backing supports which allow the removal of deteriorated facings and the identification and stabilization of the mosaics for long-term storage or eventual display in a museum or re-laying on site when more substantial funding is available. In both cases, the absence of sufficient storage facilities nearby the sites led to the lifted mosaics’ transportation to other locations within the country, highlighting the lack of planning when the excavations took place. Lack of surviving documentation about the mosaics has in both cases necessitated a treatment and storage approach which favors reversibility, accessibility and portability.

Introduction

The Getty Conservation Institute (GCI), has addressed the conservation of ancient mosaics from the earliest years. Since 2000, it has focused on building the capacity of government conservation authorities in the Mediterranean region through multi-year training courses aimed at creating site-based teams of a new job profile of mosaic conservation technician for in situ mosaics (Roby, Alberti, and Ben Abed Citation2005; Roby et al. Citation2008). In the past year, in the context of the MOSAIKON Initiative (Dardes et al. Citation2010; Teutonico and Friedman Citation2017; Teutonico and Friedman Citation2018), the GCI’s technician training has also addressed, in collaboration with the Direction du Patrimoine Culturel of Morocco, the conservation of detached mosaics, both those left in storage without backings, and those re-laid on concrete panels on site. This training has been done in response to the increasing threat to their conservation throughout the Mediterranean region, caused by the decades-long practice of preserving mosaics by detaching them. This practice has created an enormous backlog of deteriorating, unbacked mosaics in storage (Al-Azm Citation2008), as well as many mosaics re-laid on concrete on sites requiring new beddings after decades of exposure and structural deterioration of their support panels.

In the fall of 2018 at the World Heritage Site of Volubilis, practical training over six weeks was provided to technicians from North African countries who had previously received GCI training in the conservation of mosaics still in situ. They obtained experience in re-laying a mosaic on a new foundation of layers of lime mortar after removing the old concrete backing. The training also provided on-site experience with the long-term storage of mosaics which had been lifted from a different site decades earlier in 1965, and left on wooden boards face-down on the facings used to lift them without providing a new backing (Thouvenot and Luquet Citation1951; Ponsich Citation1960; Belkamel and Qninba Citation2011).Footnote1 Lack of financial resources, trained personnel, plus poor storage conditions had left the mosaics from Banasa in Morocco after decades in perilous condition with their facings and wooden support panels disintegrating or lost. This is a common storage situation found in all parts of the Mediterranean region, and solutions need to be found to provide inexpensive backings so that the mosaic fragments can have their facings removed, be identified, documented and stored properly for the long term, while allowing the possibility for selected mosaics to be reassembled and re-laid back in situ or presented in a museum context. This paper presents the sustainable approach and methodology adopted during the training course in Volubilis for the long-term storage of mosaics, and how it can be adapted to other similar storage situations such as at Sidon in Lebanon.

Documentation

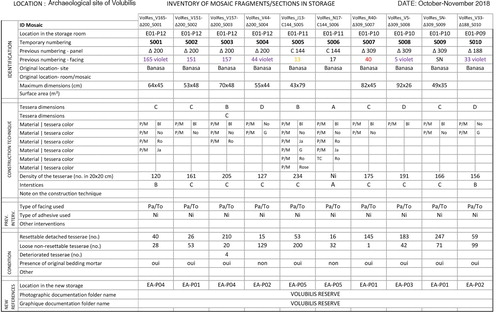

As is often the case with detached mosaics left in storage for many years, no documentation was found in the archives at the time of the training to identify the fragments or sections of the mosaics detached and moved from the site of Banasa, except for the numbers and letters written on each of the wooden panels which had been laid in stacks in no discernable order (), and for the numbers sometimes found on the facings. The panels had been moved to locations at Volubilis over the years and in many cases, more than one fragment of mosaic was found on a single wooden panel. Therefore, it was necessary as a first step of their documentation to create an identification system which preserves the old surviving documentation, where it still exists, and includes a new sequential numbering to facilitate the eventual re-grouping of fragments together as a pavement. The mosaic identification starts with the color and number (V(violet) 33) found on the facing, then the letter/number found on the panel (C144). The previous documentation is then followed by a temporary identification number which was given to each fragment/section (S(section/fragment)001, S002, etc.): V33_C144_S012. In addition to this mosaic ID, the location of each panel in each stack was documented (E01-P12, Etagere01-Panneau 12) to aid in the eventual identification of which fragments belong to which pavement, as was the storage location (VolRes, Volubilis Reserve). A mosaic inventory and data form was created to compile all the pertinent information about each mosaic, including its construction technique, previous interventions and condition ((a)). Before commencing with the treatment of each fragment, an orthogonal image was taken of the reverse side of the mosaic and thus a set of images was prepared for carrying out graphic documentation of conditions and treatments.

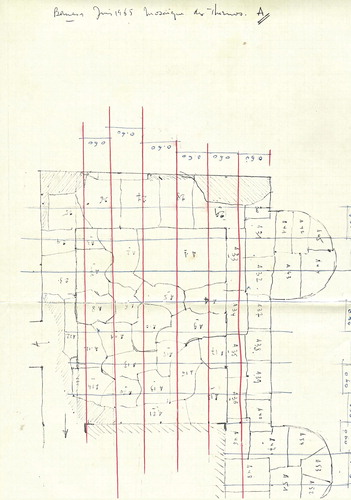

Subsequent to the training session, archival documentation at the site of Volubilis was re-discovered, showing the plans of the mosaics and the numbering of the sections when they were cut and detached in 1965 ((b)), and how they correspond to the wooden panels used to store them. This new previous treatment and storage information will now make their recording far easier, and their eventual re-laying in situ back in buildings at the site of Banasa a real possibility.

Treatment for long-term storage

In many cases, the facing of the mosaic fragments, consisting of a double layer of paper and probably cotton cloth, and an unknown adhesive, was in poor condition and many tesserae were found no longer attached to it. The first treatment step was then to re-adhere the detached tesserae, using a locally-available commercial vinyl resin adhesive, when their original location was known, otherwise the loose tesserae were collected and placed in a labeled plastic containers and stored.

Once the detached tesserae were re-adhered or removed, each mosaic fragment was cleaned mechanically by brush, scalpel and vacuum cleaner. In order to safely turn over each mosaic fragment and remove the deteriorated facing, a layer of clay was applied to the reverse and sides of the mosaic to hold the tesserae in place. A panel of wood has been placed on top of the clay layer to form a sandwich with the panel underneath the mosaic, and then the panels are held together by four vise grip clamps before turning the sandwich over. An orthogonal image was then taken of the facing and the front of each mosaic. Any guide or reference lines on the facing used during the lifting were reproduced on the mosaic surface by pencil at the two ends of the fragment before removing the facing and adhesive with the help of a cloth, sponge and hot water. After photographic and graphic documentation of the condition of the front of each mosaic, it was cleaned mechanically as well as with water, brush and sponge before the surface was re- faced, this time with a layer of cotton gauze and a mixed cotton-synthetic cloth adhered with the vinyl resin. The fragment was then sandwiched as before and turned back on the front, and the clay layer temporary backing was removed with the help of dental pick tools and a moist brush and sponge.

The back of each mosaic was then prepared for applying the new backing that will be used for the fragment’s long-term storage. The type of backing was chosen following tests of different materials and re-enforcement, but they were all lime mortar-based, because of the importance of using inexpensive, easily reversible and compatible materials which are available locally in order to insure the sustainability of future conservation work on the stored mosaics by local personnel. First, the areas of loss (lacunae) were filled with a 1:2.5 lime mortar mix (0.5 parts lime putty, 0.5 parts hydraulic lime (Interchaux NHL 3.5), 1.5 parts sand (0–0.5 mm), and 1.0 parts stone powder (0.5–3 mm). Then a lime-rich, fine, 1:1.5 lime mortar mix (2 parts lime putty, 1.5 parts sand (0–0.5 mm) and 1.5 parts stone powder (0–0.5 mm)) was applied to the reverse of the mosaic and in the interstices. A second, reinforced layer of lime mortar was then applied to the back, consisting of 0.5 parts lime putty, 0.5 parts hydraulic lime (Interchaux NHL 3.5), 1.5 parts sand (0–0.5 mm), and 1.5 parts stone powder (0.5–3 mm). Hemp fibers, 1–3 cm in length, were added 10 g/L to the mix to insure greater flexibility and tensile strength for the mortar during the future manipulation of the mosaic fragments.

After the setting of the mortar, a layer of protection was applied to the mosaic edges using gauze and vinyl resin as well as a piece of cloth for labeling the mosaic fragment with its ID number. For additional protection of the mortar, a layer of burlap fabric was attached to it using an adhesive paste made of 1 part vinyl resin, 4 parts lime putty and 2 parts yellow sand (0–0.5 mm). Finally, each fragment was turned over face-up so that the new facing can be removed with hot water, and the mosaic surface cleaned by brush and sponge (). Once the mortar has set, each newly backed fragment can then be safely moved and carried on a panel to the storage area.

Storage structure prototype

For long-term storage, it was determined that a metal structure with horizontal shelves would be preferable because it would not be compromised by varying humidity over time as with wood. Painted iron has been chosen for the structural elements to keep costs down, while aluminum was chosen for the shelves for its lightness. The dimensions of the structure (1 m x 1.5 m x 1.5 m) were determined by the average dimensions of the fragments, which were quite small (generally 60 × 40 cm). The structure was made modular in order to keep initial costs down and to allow for additional structures to be constructed year-by-year. It was considered advantageous to be able to slide the shelves in and out of the structure to effortlessly access and examine each mosaic, rather than forcibly drag each heavy shelf, loaded with one or more fragments. Therefore, a roller system was devised, using inexpensive nylon rollers, so that each shelf could easily be extracted ((a)). Given the purpose-built nature of the shelving structure, a local metal working shop was identified to construct the shelving structure prototype. By using a local company to construct the prototype, the costs have been kept low and additional structures can more easily be constructed and cheaply delivered to the site as budget becomes available in the future. After the final image was taken of the front of each newly backed mosaic, it was then slid onto an aluminum shelf placed next to it which was then lifted and slid into the iron structure on rollers on each shelf level of the structure ((b)).

Storage training results

Over three weeks, 12 trainees had the experience of backing 18 mosaic fragments/sections, and about half a stack of deteriorated plywood panels had been replaced by a metal structure which allows the mosaics to be safely viewed and studied, and to remain in stable condition for many years despite the currently uncontrolled environment. This was accomplished using low-cost, compatible, local materials to insure that the trainees will have a sustainable methodology to continue the work. When the other mosaics in storage from Banasa are eventually backed, the fragments can then be re-organized, as needed, according to the pavement they belong to. Ultimately the fragments can still be reassembled and either put back on site in their original location on new lime mortar beddings after removing their new lime mortar backings for storage, or selected mosaics could be chosen for future presentation in a museum.

Future training in Lebanon

A similar mosaic storage situation has been encountered in Sidon, Lebanon, and plans are currently underway to organize a course to train Lebanese and other personnel from nearby countries to address the conservation problems posed by unbacked detached mosaics. Although the mosaics in Sidon were detached much more recently than those stored in Volubilis, there is very little documentation about them either, in the archives of the Directorate General of Antiquities (DGA) of Lebanon. The mosaics at Sidon are almost entirely from the salvage excavations of ancient Berytus in the central district of Beirut in the 1990s. Conservation in situ of the mosaics was not acceptable to the developer, Solidere. As a result, teams of workers were brought in to quickly remove the mosaics from various ancient Roman buildings, generally by using a rubber contact adhesive, Pattex, and cotton cloth for facing, and then detaching the mosaics by hammering the mosaic surface.

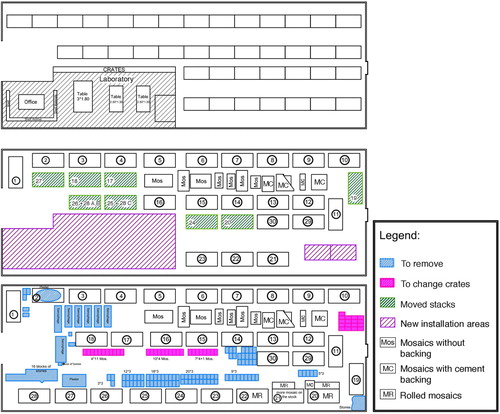

Because the DGA did not have sufficient storage space in Beirut for the over 800 square meters of mosaics from the Beirut excavations, nor available land in the city to construct a structure, it built a new facility on their land in the city of Sidon. In 1998, the piles of unbacked mosaics in temporary storage in one of the last war-damaged buildings to be demolished by Solidere were stabilized and placed on individual wooden panels, then lifted by crane in stacks on to flat-bed trucks and transported to the new storage facility in Sidon (Skaf and Roby Citation2003), thereby saving them from certain destruction. Since the arrival of the mosaics at the Sidon facility, the mosaics have not been touched, and additional archaeological materials from other excavations have been placed in both the main storage hangar and the adjacent planned laboratory, occupying the space originally left to move and work on the mosaics. In addition, lack of maintenance on the structure and insufficient drainage has contributed to rainwater entering the rooms through windows and walls, which over the years has caused the deterioration and partial collapse of some of the stacks of mosaics ((a)). Necessary repairs to the structure have been made by the DGA in recent years, and plans are being developed to prepare part of the storage area to house a laboratory and the equipment needed to carry out a training course and the subsequent work of the DGA to properly document and store the mosaics for the long term ((b)).

Figure 5. (b) Plan of mosaic storage in Sidon with current situation (below), proposed re-organization for training course (middle), and future storage (top).

The history of the mosaics in storage at Volubilis and Sidon are quite similar, except for the fact that the mosaics currently at Volubilis were not the consequence of a salvage excavation. Poor storage conditions in the past have in both cases threatened the survival of the mosaics due to the deterioration of many of the wooden support panels under the mosaics and the facings holding the tesserae in place. The condition of the actual mosaics is, however, worse in the case of the Sidon mosaics, in large part because of the way that they were detached, using hammers on the faced surface of the mosaics, resulting in many of the tesserae being fractured into pieces, or in only the face of each tessera left adhered to the facing. The use of the commercial adhesive Pattex to face the mosaics, being largely irreversible, also makes removal of the facings difficult and time-consuming.

The other main difference between the two storage situations is the size of the mosaics, both the size of the fragments or sections and their wooden support panels, and the size of the tesserae themselves. The mosaics in Sidon are much larger and therefore heavier, and their movement, manipulation and long-term storage will be more challenging and will necessitate a different technical response.

However, to ensure that the conservation work on the mosaics will continue after the training, a similar approach and methodology to that used in Volubilis will be employed in Sidon, using locally available and inexpensive materials and equipment. A metal shelving structure will be designed and constructed locally to accommodate the dimensions of the largest available plywood panels (1.22 × 2.44 m). 40 structures will be needed to accommodate all of the more than 800 square meters of mosaics, to be arranged 1 m from the walls of the storage hangar in rows so that they can be easily accessed in the future and avoid exposure to rainwater ingress. Although the removal of the facings will require in most cases a combination of mechanical means and solvents due to the nature of the adhesive used, the new backings will be lime mortar-based, reinforced with natural fibers as employed in Volubilis, or using synthetic fibers found locally. Tests will be carried out using the different reinforcement materials found in Lebanon to back the generally larger mosaic fragments/sections in Sidon. The additional complication at Sidon presented by the many fractured tesserae will require testing of locally-available adhesives to re-adhere the fragments.

Despite the greater challenges presented by the condition, size and previous interventions of the Sidon mosaics, the best chance of preserving the surviving remnants of the mosaics of Beirut, as in Volubilis, is by developing simple, inexpensive and sustainable treatment methodologies for their long-term storage. All countries in the Mediterranean face the increasingly severe problem of expanding collections of detached mosaics left in storage on sites and in museums, often left rolled up without any backing. In the past, the alternative solutions were using inexpensive local concrete to back them, or relying on foreign assistance and imported materials such as Aerolam panels and epoxy resins. This paper presents two critical, yet common, situations which demonstrate that addressing the backlog of detached mosaics throughout the Mediterranean can be achieved through training programs for conservation technicians to follow simple documentation protocols, mosaic backing treatment methods using locally available lime-based mortar materials, and locally manufactured metal shelving structures to create sustainable long-term storage for mosaics.

Supplemental Material

Download MP4 Video (422.2 MB)Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge the support and logistical assistance of all the staff of the Conservation of the Site of Volubilis in preparing and equipping the training worksite in their teaching and storage rooms so that the course was efficiently and successfully completed. They include Omar Bouka, Fatima Zahrae Cadi and Abdelilah Sguiri. We also are grateful for the assistance provided by the staff of the Sidon office of the DGA, including Ghida Osman, who reproduced the storage reorganization plan drawing in digital form ((b)).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Unpublished archival document from the archives of the archaeological site of Volubilis.

References

- Al-Azm, A. N. al M. 2008. “Conservation and preservation of mosaics in Syria: The case for a multidisciplinary approach–or new strategies for old problems.” In Lessons Learned: Reflecting on the Theory and Practice of Mosaic Conservation: Proceedings of the 9th ICCM Conference, Hammamet, Tunisia, November 29 – December 3, 2005 / Leçons retenues: Les enseignements tirés des expériences passées dans le domaine de la conservation des mosaïques: Actes de la 9e conférence de l'ICCM, Hammamet, Tunisie, 29 novembre - 3 décembre 2005, Proceedings of the 9th ICCM Conference, 2005, ed. A. Ben Abed, M. Demas, and T. Roby, 139–143. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/lessons_learned_reflecting.html.

- Belkamel, B., and Z. Qninba. 2011. “Les mosaïstes et la décoration des thermes en Tingitane.” Asinag: Institut royal de la culture amazighe=Asinak 6: 59–66. http://www.ircam.ma/sites/default/files/doc/revueasing/bidaouia_qninba_asng6_fr.pdf.

- Dardes, K., J. M. Teutonico, C. Antomarchi, and Z. Aslan. 2010. “Building Capacity for the Conservation of Mosaics in the Mediterranean: The MOSAIKON Initiative.” In Conservation and the Eastern Mediterranean: Contributions to the Istanbul Congress, 20 – 24 September 2010, ed. C. Rozeik, A. Roy, and D. Saunders, Studies in Conservation 55 (Supp2): 30–34. London: IIC.

- Ponsich, M. 1960. “Technique de la dépose, repose et restauration des mosaïques romaines.” Mélanges d'archéologie et d'histoire 72: 243–252. http://www.persee.fr/web/revues/home/prescript/revue/mefr. doi: 10.3406/mefr.1960.7468

- Roby, T., L. Alberti, and A. Ben Abed. 2005. “Training of Technicians for the Maintenance of Mosaics in Situ: A Tunisian Experience.” In 8o Synedrio Diethnous Epitropes gia te Synterese ton Psephidoton (ICCM): Entoichia kai Epidapedia Psephidota: Synterese, Diaterese, Parousiase Thessalonike, 29 Oktovriou – 3 Noemvriou 2002: Praktika / VIIIth Conference of the Internation al Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics (ICCM): Wall and Floor Mosaics: Conservation, Maintenance, Presentation: Thessaloniki, 29 Oct – 3 Nov 2002: Proceedings of the 8th ICCM conference, 2002, ed. C. Bakirtzis, 347–357. Thessaloniki: Europaiko Kentro Vyzantinon kai Metavyzantinon Mnemeion. https://www.iccrom.org/publication/conference-viiith-international-committee-conservation-mosaics-iccm-wall-and-floor.

- Roby, T., L. Alberti, E. Bourguignon, and A. Ben Abed. 2008. “Training of technicians for the maintenance of in situ mosaics: An assessment of the Tunisian Initiative after three years.” In Lessons Learned: Reflecting on the Theory and Practice of Mosaic Conservation: Proceedings of the 9th ICCM Conference, Hammamet, Tunisia, November 29 – December 3, 2005 / Leçons retenues: Les enseignements tirés des expériences passées dans le domaine de la conservation des mosaïques: Actes de la 9e conférence de l'ICCM, Hammamet, Tunisie, 29 novembre - 3 décembre 2005, Proceedings of the 9th ICCM conference, 2005, edited by A. Ben Abed, M. Demas, and T. Roby, 258–264. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/pdf_publications/lessons_learned_reflecting.html.

- Skaf, I., and T. Roby. 2003. “The preservation of detached mosaics: Addressing storage and transportation problems resulting from the large-scale re-development of the central district of Beirut.” In Les mosaïques: Conserver pour présenter? / Mosaics: Conserve to Display?: Actes = Proceedings, VIIème conférence du Comité international pour la conservation des mosaïques, 22 – 28 novembre 1999, Musée de l'Arles antique et Musée archéologique de Saint Romain – en – Gal / VIIth Conference of the International Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics, Proceedings of the 7th ICCM conference, 1999, ed. P. Blanc, and V. Blanc-Bijon, 221–228. Arles: Musée de l'Arles et de la Provence antiques.

- Teutonico, J. M., and L. Friedman. 2017. “The MOSAIKON Initiative for the Conservation of Mosaics in the Mediterranean Region: An Update on Activities.” In Managing Archaeological Sites with Mosaics: From Real Problems to Practical Solutions: The 11th Conference of the International Committee for the Conservation of Mosaics, Meknes, October 24 – 27, 2011, Proceedings of the 11th ICCM conference, 2011, edited by D. Michaelides, and A. M. Guimier-Sorbets, 365–374. Firenze: Edifir edizioni. https://iccm-mosaics.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/MEKNES-Proceedings.pdf.

- Teutonico, J. M., and L. Friedman. 2018. “MOSAIKON 2008–2018: Objectives, Outcomes, Opportunities.” Conservation Perspectives: The GCI Newsletter 33 (1 Spring): 10–12. http://www.getty.edu/conservation/publications_resources/newsletters/33_1/.

- Thouvenot, R., and A. Luquet. 1951. “Les Thermes de Banasa.” Publications du Service des antiquités du Maroc 9: 9–62.