ABSTRACT

Contemporary art conservation is constantly facing challenges relating to materials of poor stability that artists incorporate in their practice, the obsolescence of technological elements within artworks, as well as the multitude of ethical issues that these artworks raise. With the conceptual aspect of artworks often being given emphasis, questions about what values exist within the context and content of the artwork, its universe, is becoming critically important. These questions have become even more complicated since the introduction of replicas created with the use of digital reproduction tools; 3D scanning, 3D printing, digital image capturing and reproduction, and wiki-style documentation methods. Using philosophical frameworks, an attempt is being made to clarify what form replicas of contemporary artworks can take and what conservators should be aware of. The analysis of the values associated with these replicas is illustrated by three case studies; street art, a time-based media artwork, and the work of an artist who specialises in 3D assisted creations. The influence of replicas of contemporary artworks in the decision-making process through their values and interaction with the original amplifies the conservator’s feeling of responsibility.

Introduction

The field of contemporary art conservation is constantly faced with a number of hitherto unprecedented ethical challenges, especially when devising conservation approaches appropriate for their often contradictory needs. Ephemerality, unstable materials, rapid obsolescence of technological elements and components that need constant reinterpretation are but a few examples of how contemporary artistic expression is in a state of flux (Chiantore and Rava Citation2012, 14–16; Marçal Citation2012, 3, 41; Engel and Phillips Citation2019, 192). Undoubtedly, the most impactful change can be attributed to the emphasis given to the conceptual side of the artworks, which not only creates a different sensory experience but also guides the conservation approach. Thanks to this, the perception of ‘uniqueness’ of the artwork derived from the originality of its material elements is put into question, with the importance of the idea behind it being emphasised.

Changes in the very identity of the artwork, which often demand each viewer’s individual interpretation and interaction to exist (Frasco Citation2009, 12), challenge conventional notions of authenticity and affect the values that conservators try to assess during the decision-making process. Different manifestations such as replicas of artworks add an extra layer of nuance on the subject of authenticity, which is a heavily debated term amongst academics that gives rise to a multitude of philosophical conundra (Bery Citation2007; Hermens and Fiske Citation2009; Gordon, Hermens, and Lennard Citation2014; Hermens and Robertson Citation2016). Through the presentation of three examples, an attempt will be made to identify the values derived from the different types of artworks’ replicas and explain some of the ways these values impact the choices made by conservators dealing with contemporary artworks.

Where contemporary replicas meet philosophy

The ontology of an artwork refers to both material and immaterial aspects that are context-dependent and bound to each interpreter’s background, biases and relative intentions. This interaction between subjects and objects leads to what Umberto Eco called ‘the open work of art’ (Eco [Citation1964] Citation1989, 4). Indeed, the sphere where the ontology of the artwork lies is not fixed space. It is an ever-expanding area, dynamically influenced by these interpretations and encompassing all the data generated by the interpreters. The Benjaminian aura as a ‘unique manifestation of a remoteness, no matter how near it may be’ (Benjamin [Citation1935] Citation2008, 39), alludes to a unique quality of the original artwork which is entangled with its authenticity. It is not lost but divided and redistributed into the different aspects of each artwork’s area of context and content, its universe. A constellation of facets exists in the artwork’s universe, containing amongst others its manifestations depending on the different instantiations of its condition, the artist’s intention, the aforementioned interpretations by stakeholders, and the multitude of potential replica manifestations.

Replica in this article is every manifestation of the artwork, be it tangible or not, that resembles the artwork enough to make it recognisable. Defining what can constitute a replica is not independent of personal experience, cognitive biases, intentions, and levels of engagement with the artwork. Nevertheless, avoiding the pitfalls of an outright relativistic approach is crucial, meaning that a certain level of critical thinking is necessary for the contemporary art conservator to assess the importance of replicas when they appear. It is not uncommon for the terms ‘replica’, ‘reproduction’, and ‘copy’ to be used interchangeably. To investigate their significance and try to understand their subtle differences, it would be useful to anchor our thinking in terms of a philosophical analysis. For the purposes of this article, borrowing the structure of Jean Baudrillard on the notion of a ‘simulacrum’ can act as a guiding light.

Baudrillard divided simulacra into three orders, depending on their levels of connection with the natural world. In his 1976 book, Symbolic Exchange and Death, he wrote:

The first-order simulacrum never abolishes the difference [between being and appearance]: it presupposes the dispute always in evidence between the simulacrum and the real. The second-order simulacrum simplifies the problem by the absorption of appearances, or by the liquidation of the real. (Baudrillard [Citation1976] Citation1993, 52)

it is a matter of a reversal of origin and end, since all forms change from the moment that they are no longer mechanically reproduced, but conceived according to their very reproducibility, their diffraction from a generative core called a ‘model’’.

From Baudrillard’s analysis, one way of drawing a parallel would be if contemporary artworks are seen as associated with the first-order simulacra by acting as a faithful copy derived from an element of the natural world, in this case, the idea that the artist is aiming to convey through her creation. The replica of an artwork could be seen as belonging to second-order simulacra by hinting at the symbolism within the artwork but failing to represent the natural in a faithful manner. The evaluation of third-order simulacra is not as straightforward as the previous orders; by eliminating a clear, direct or indirect reference to the original, they become symbols in themselves and therefore lose immediate connection to the object of focus for contemporary art conservators, that is the artwork. It is these types of replicas that are hard to assess for significance and relevance to conservation but, fuelled by the embracement of technology in our society and a move towards total immersion within its realm, this assessment is becoming increasingly complex. In a somewhat dystopian view of the matter, it could be suggested that the presence of third-order simulacra signifies a direction towards the death of an artwork but not in its conventional conception (Kapelouzou Citation2010, 153–156; Scott Citation2016, 49) – an idea equally unnerving and important for contemporary art conservators to consider.

The format of the replicas that contemporary artworks manifest can vary, and in the case, they take the form of third-order simulacra, it would be almost impossible to be recognised as such. In their second-order division, they always act as a symbol of and coexist with the original in the universe of the artwork. The relationship between original and replica is strong yet flexible, with the ontology of the artwork being constantly redefined through this co-dependent exchange of meaning and significance. The replicas this article will focus on are the ones created by means of digital reproduction tools, such as 3D scanning, 3D printing, digital image capturing and reproduction, and wiki-style documentation methods.

All hail technology

Fast-paced technological advancements have facilitated access to devices that capture and duplicate the visual, audio, and tactile characteristics of an artwork, more often than not in a resolution so high that subtle discrepancies from the original are not perceivable by the audience (Latour and Lowe Citation2011, 276–277). The distribution of the artworks’ audio-visual characteristics are promoted through social media platforms but also through the databases and websites of various cultural institutions. Consequently, an enormous archive of artworks’ characteristics is constantly generated and disseminated, often freely and instantaneously, in every part of the globe through the internet. Furthermore, material manifestations of replicas of artworks, such as the end-product of 3D printed objects, are slowly but steadily infiltrating museums in the form of gift shop commodities, exhibition copies, and educational aids. Replicas created with the use of digital tools and shaped by the interpretations made by various stakeholders, while inextricably linked to their ‘parent-original’, maintain the potential to acquire a unique identity and evolve independently (Norton Citation2016).

It is crucial to highlight the agency that the intention behind replica creation bears. As the movement of post-phenomenology suggests, technology has a profound function in mediating our relations with the world (de Boer, te Molder, and Verbeek Citation2018, 740). Therefore, the impact that technology has had in shaping the society we inhabit is informing the purposes of making reproductions of contemporary artworks. This is a subject fairly well researched in the field of philosophy of technology, where influential thinkers have been warning about the dangers of technological use without the necessary moral underpinnings and guidance (Heidegger [Citation1954] Citation1996, 16, 33; Bunge Citation1977, 99; Jonas Citation1979, 41; Floridi Citation2003, 464–465). Some of the replicas may be created with the benign purpose of educating the public or safeguarding the condition of a fragile artwork, as in the case of exhibition copies (Nagy Citation2021). Others may carry dangers of skewing the artist’s intent as in the case of musealised (Adorno [Citation1967] Citation1996, 175) ephemeral artworks, for example, a number of unauthorised Banksy works that have been forcefully removed from their initial locations and placed in stable environmental conditions indoors, possibly disassociated from their original context, when the information on attribution is inaccurate. Furthermore, let us not forget the forewarnings of Benjamin on the power that reproductions can enforce upon society when the political authorities that create and use them in the form of propaganda have ethically questionable motivations (Benjamin [Citation1935] Citation2008, 36–38, 50).

In a similar political vein, it is only fair to acknowledge that conservation decisions are likewise politically charged. The power of reproductions is politically charged through the means of propaganda or marketing. The conservation process includes decisions over what is considered a ‘conservation object’ important enough to be preserved (Muñoz Viñas Citation2005, 30 defined this term), which is also political action. Choosing which artwork will be treated, how, and for whom always carries significance that goes beyond the site of practice, in spatial, temporal, and sociological terms. Furthermore, with the abundance of replicas in their various forms questioning the feasibility and sustainability of storing all this material and immaterial information, conservators find themselves in positions where they are called upon to make executive decisions over the replicas that can impact the artwork’s meaning, biography, and also environment. Solving the storage issue will become a more pressing matter as the need for information inclusion increases. Thankfully, positive steps in this direction, such as DNA storage which is currently gaining traction (Tabatabaei et al. Citation2020), give signs of hope for resolving the issue while limiting risks pertaining to obsolescence. Nevertheless, choosing which of the replicas of an artwork are considered important to preserve, as in the case of social media-generated documentation, often comes down to authoritative decision-making processes which lie in the very core of preservation practice. In addition, the cultural institutions that are the conservator’s natural habitat also play an important political role in such decisions, so this requires careful attention. It is now more clear and overt that conservation, contemporary art, its replicas, technology, and politics are all intertwined.

Values and replicas

The stakeholders attributing values to artworks can be, amongst others, the artist or her estate, the owner or custodian, and the audience. Nevertheless, it is another stakeholder, the conservator, who is called upon to assess these values with the aim of meeting an objective such as taking action in order to preserve the artwork’s meaning. The original maintains values that may include: aesthetic, age, research, historical, sentimental, newness, and educational ones (Appelbaum Citation2007, 208–209). Some of them are lessened due to the existence of replicas, while others are amplified; this relies on each stakeholder’s attribution as well as the relative time frame in which the assessment takes place. Rarity is a prime example of a value that can be lowered, whereas monetary value can be heightened, especially through promotion. Some of the values migrate to an extent into the artwork’s various replicas and coexist through the associative link between them and the original. Moreover, replicas themselves carry values that require the conservator’s attention and thoughtful consideration. These values become palpable especially when conservators, alongside the various stakeholders, are called upon to consider and evaluate not only the preservation but also the presentation of artworks, a step that lies in the very core of the decision-making model developed by the Stichting Behoud Moderne Kunst and the Cologne Institute for Conservation Science (SBMK and TH Köln Citation2019). This model, even before its 2019 revision, has been proven to be the contemporary art conservation framework par excellence. Replicas shape the procedure of decision-making by bringing their own idiosyncratic characteristics and mandating a reconsideration of the original’s very essence. The existence of values attributed to originals and replicas constructs a dynamic system where they interact, overlap and sometimes conflict with each other.

The expanded concept of the replica as proposed in this paper creates the need for its inclusion in the universe of contemporary artworks, more specifically in the examination of the constellation of values that need to be documented and then preserved on a case-by-case basis. In this universe, authenticity does not maintain the significance it once had as a property closely related to the value of the artwork’s original manifestation (Jokilehto Citation1995, 30, 32; Jadzińska Citation2011, 27; Chiantore and Rava Citation2012, 45). The evaluative framework for assessing this significance emerges from the added values that are encountered in the artwork’s universe, especially the ones related to its replicas. Their importance is often pointed out in the wider discussion about replicas in contemporary art conservation, but these have yet to be critically appraised, and their place has not been legitimately established in contemporary ethical codes of practice, such as the Venice Charter (ICOMOS Citation1964 article 9, 11) or the Burra Charter (ICOMOS Citation2013 article 13, 24). Even the 1994 Nara Document, which is the pre-eminent international charter regarding authenticity and replication, does not extend to include modern replicas (ICOMOS Citation1994 article 11, appendix 1). In talking about codes of practice, a distinction has to be made between the top-down guidelines, as introduced by international institutions and charters, and the bottom-up approach closely related conceptually with what van de Vall called ‘a moral taxonomy’, meaning ‘a compilation of collection of cases and their comparison’ (van de Vall Citation1999, 198). Both are equally important in recognising the significant impact that contemporary artworks’ replicas have in the process of evaluating the ontology of an artwork.

Case study: street art

Street art is part of a scene that has witnessed a cataclysmic rise in popularity and has drawn public attention and admiration. Its audience plays a crucial role in the longevity of artworks, especially by creating digital replicas in the form of photographic recordings that capture their visual characteristics and their dynamic relationship with their environment. The work becomes known, attracts interest and creates an impact within minutes of its creation through its digital replicas. It is true that for the vast majority of street artworks, their admirers will never have the chance to interact with the mural in person, thus creating a hybrid relationship between the work and its spectators. These replicas eventually become the only surviving tangible aspect of the artwork when its ephemeral nature comes into effect. They replace the physical work in the original audience’s collective remembrance, allowing artworks that have ceased to exist in the natural world to continue influencing their viewers in a way that contrasts with the images of museum artworks. This dissimilarity lies in the digital life of the artworks on various websites, blogs, and social media platforms (Merrill Citation2015, 383; Edwards-Vandenhoek Citation2015, 84–87; MacDowall and de Souza Citation2018, 6).

However, not all replicas are of the same quality. The quantity of replicas generated, especially thanks to social media, further highlights the significance of their quality which, alongside the resolution, can include the frame, angle, colour saturation and possible image distortions. The audience as co-producer of the artwork’s universe influences heavily the attribution of values upon the artwork. The co-existence of the artworks in their natural and digital form, even for a short period of time before the original artworks vanish, offers a thus far little exploited tool for documentation in the hands of contemporary art conservators. Moreover, it opens up the concept of street art’s preservation, since its expanding universe not only contains these replicas but argues for their safeguarding, as will be illustrated further through the example that follows. The artwork’s importance is inevitably documented through the totality of its sphere of influence, in both the natural and the virtual space, and it is this new reality that conservation is obliged to take into account. This especially holds truth for digital replicas created by the artists themselves immediately after the completion of the artwork, as a means for publicising their creation and attracting audiences. In this way, the artists set their own rules for public engagement.

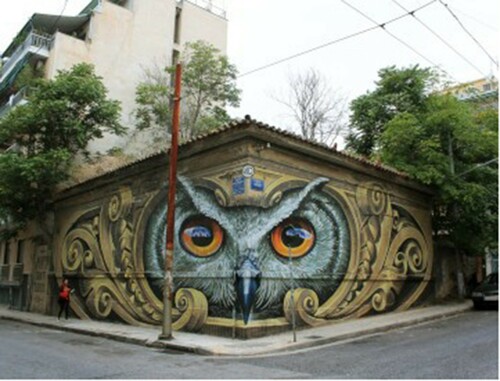

Knowledge speaks, Wisdom listens (2016) () by Balinese street artist Wild Drawing is an artwork that became viral on the internet soon after its creation, facilitated both by conventional media and by social media platforms. The hype from this mass-production of replicated images had two major consequences; it enhanced the audience’s accessibility to and involvement with the artwork but it instigated acts of vandalism that dramatically altered the artwork’s appearance. The pressure on the different stakeholders involved with the artwork was further heightened by its popularity and the social importance of the wall painting within its community and neighbourhood. The St.A.Co. (Street Art Conservators) team, which is a group consisting of volunteer students and staff of the Department of Conservation of Antiquities and Works of Art at the University of West Attica, was called upon to offer solutions that would restore the aesthetic value of the artwork (). Alongside this, its social value was also amplified, as it was evident from the community’s reactions before, during and after the conservation process. Moreover, the artwork’s research and educational values after the vandalism were revealed through the creation of its replicas, following which the artwork was the centre of focus for a number of educational programmes and dissertations by students of the University of West Attica and the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens (Oreianou Citation2018; Mini and Fragkiskou Citation2019; Chatzidakis Citation2020, 133–143). It could be argued that by this, ‘migration of the aura’ from the first-order simulacrum (the mural) to the second-order (the replicated digital images), the amplification of existing values and generation of new ones necessitated serious consideration during the decision-making process.

Figure 1. Wild Drawing, Knowledge speaks, Wisdom listens, Athens, Greece, 2016. © WD, 2016 http://wdstreetart.com/street.html.

Case study: time-based media

The documentation of time-based media artworks often challenges our understanding of their ontology and our ability to safely define which are aspects in need of preservation are. These aspects, Laurenson’s ‘work-defining properties’ (Laurenson Citation2006), are sought after by conservators in order to address issues related to their maintenance and create innovative tools that could assist with this aim. Material and immaterial elements of these works deteriorate or become obsolete faster than our ability to keep up with these changes. Conservation practices are therefore required to be constantly evolving in order to meet the needs of these types of artworks.

Before delving into the second case study, we will first take a look at the special characteristics of the category it belongs to. Net art, which developed in the mid-1990s, involves the use of software and the internet in creating artistic projects (Ippolito Citation2002, 486). Its core behavioural elements are interactivity, iterativity, and context-dependency. The iterativity gives rise to questions regarding its authenticity, which further complicates the issue of the valuation and assessment of replicas. Authenticity in the context of net art is intrinsically linked to versioning, multiple authorship, and processuality (Dekker Citation2015a). In order to pay respect to these characteristics, conservators dealing with the preservation of net artworks need to reconfigure the traditional object-focused, time-arresting perspective into one which accepts, stewards and enables change. This, of course, holds true for a number of other artworks inherently in flux, such as the ones that are the research focus of the Variable Media Network (Jones Citation2004). The conservator becomes a manager of the processuality of the artwork, documenting its evolution through time and brokering collaborations (Falcão and Ensom Citation2019, 14).

The artwork Naked on Pluto (2010-2013) () was created by de Marloes de Valk, Aymeric Mansoux, and Dave Griffiths as an online game that engaged users in utilising Facebook data, in an attempt to highlight issues regarding privacy policies and the invasion of social media platforms in our daily lives. This interactive work was originally produced in 2010–2011 but continued to develop through workshops and exhibitions long after its game form ceased to be functional (Barok, Boschat Thorez, and Mansoux Citation2020). This was a result of an anticipated change in Facebook’s API (Dekker Citation2015b, 128) which occurred in 2013 and re-presented the software part of the game to ‘a relic’ that can be neither operated nor restored (Barok, Boschat Thorez, and Mansoux Citation2020). In order to document the artwork, the Amsterdam-based digital art foundation Li-MA commissioned a preservation research project, whose team had to first identify what exactly needed to be documented and the means through which this could be achieved. The artwork’s dependence on interactivity clearly demonstrated its dynamic character, the role that contributors play in shaping the artwork’s identity which required out-of-the-box solutions for documentation purposes.

To this end, the wiki-style publishing platform Monoskop was used, which facilitated the documentation, preservation and presentation of the artwork’s distinctive characteristics. Wiki is a website and writing platform that provides easy linking of pages and documents and can be collaboratively edited by anyone with access to it (Paul Citation2015, 260). Given that Naked on Pluto is a research-based work meant that its various manifestations, alongside the software, needed to be identified and integrated into the documentation. The latter resulted in being firstly a kind of replica symbol that one could refer to and use in order to engage with the original. Eventually, it acquired the status of being part of the artwork itself, according to the artists. In this process, the conservator assumes the role of ‘content manager’ (Barok, Noordegraaf, and de Vries Citation2019, 473) confronted with challenges related to multiple authorship, and increasingly integrating curatorial and archival practices for the epistemic analysis as well as the safeguarding the ontology of the artwork.

Case study: 3D reproduction

Modern tools of reproduction, such as 3D design, scanning, photogrammetry, and printing, have enhanced the speed and accuracy of replica creation. Although seemingly different in character, they maintain the possibility of copying the artwork's characteristics to the extent that the replica potentially becomes indistinguishable from it. These techniques present challenges, some of which can be fairly well understood, while others are hardly foreseeable. The ones that conservators are currently dealing with, namely the ethics of reprinting versus repairing (van de Braak et al. Citation2017), are heavily influenced by factors such as patina, the artist’s intention, and the lack of historic distance from the moment of their creation. Corrupted design files or non-repairable hardware malfunctions bring about conservation issues and can potentially hinder the faithful representation and even realisation of the artist’s idea (Madsack Citation2011). Nevertheless, the profound speed of technological evolution provides artists with an awareness of infrastructural change, which facilitates the freedom of their concepts’ manifestation to evolve in tandem with the tools at their disposal.

The last example revolves around the oeuvre of Cosmo Wenman. While some of Wenman’s artworks involve the 3D printed creation of replicas of ancient sculptures, others are printed objects of his own design () and even reinterpretations of famous artworks. In his view, the 3D reproductions do not compete with the original despite the similar response they attract from the audience. The function for his replicas is that of a new way to experience the artwork. Wenman is a particularly interesting case of an artist-activist-advocate for public enjoyment of art. His strong views over the responsibility of cultural institutions in the dissemination of digital replicas of cultural objects in their collections bring home the recurrent inconsistencies found in the mission statements of museums. In a presentation at the Los Angeles Country Museum of Art, he said

The fact is that right now people can absolutely make crude to medium quality copies of things using very inexpensive equipment. And that capability is only going to get more powerful and diffuse. That is all very much going to be on the table here, how museums deal with these issues. […] The real opportunity is with others’ 3D printers, with the manufacturing capability that is going to be in more and more people’s hands, outside of the museum. And the way to communicate with them is to share the data – to collect the data and freely share it with them. (Wenman Citation2014)

Wenman’s replicas require a semantic reference to their ‘parent-original’ in order to sustain their status. Simultaneously, they create a more tangible link to the audience by getting closer to it. The increased proximity is related to the fact that replicas can travel through the internet to any museum that has access to the appropriate printer. Furthermore, it also refers to the elimination of physical distance between visitors and replica. The traditional view of the visitor required to get closer to the artwork is reversed when touching the object is not reserved only for a few privileged conservators. In addition, replicas can enhance accessibility to the artworks by visitors with visual impairment, who would be otherwise unable to experience the artworks in the conventional ‘watch from a distance’ manner. Thanks to the mere existence of the replicas, the artworks acquire levels of significance for a number of people who would otherwise not have the chance to experience in such an interactive way, if at all. How does one approach the issue of conserving a replica which is meant to be frequently handled, often deteriorating quickly due to unstable materials, but might eventually become an artwork in its own right? What if it already is one by virtue of being part of the original?

The replica as an epistemological tool

In finding answers to these questions, one needs to consider in what way the values carried by replicas of contemporary artworks might affect the conservation decision-making process. In other words, through the process of determining which parts of the replicas’ ontology are important for the conservator to take into account, she begins to get a grasp of the ever-changing relationship between them and the originals. This is a far from an easy task to undertake, since this relationship is evaluated and assessed only in a specific context and moment in time. It is for this reason that a flexible approach and collaboration with the various stakeholders involved is essential.

Understandably, the expanding universe that exists around the artwork can make the conservator feel confused when weighing and prioritising the values in order to choose the appropriate course of action. Replicas can bring into this universe their own unique values, notably longevity value in the cases of street art and net art, but also accessibility value, be it referring to physical or geographical proximity to the audience. This could lead towards a democratisation of art, especially when it helps people with disabilities or those that cannot afford the trip to the museum housing the original, to have an intimate experience with the artworks through their 3D printed replicas. The educational value of an artwork can be amplified when replicas can be handled by museum visitors in order to engage with the artwork in a more personal way. The tendency of contemporary artworks to be influenced by their stakeholder-created replicas further complicates the process of decision-making and amplifies the conservator’s feeling of responsibility.

Conclusion

Organising and weighing the values brought about by replicas of contemporary artworks, as well as how they influence the values belonging to the original, is not one-size-fits-all. Every case will require careful consideration of its context and thorough reflection from the conservator regarding decision-making practices and constant updating of the available tools. It will not be long before we are faced with new types of replicas, most probably bringing with them an array of new types of values. Foresight is invaluable yet unattainable; however, proactivity is our duty. Another important aspect of preserving the values carried by artworks and their replicas, whether material or immaterial in nature, is the question of sustainability with regard to time, money and energy resources invested. It goes without saying that the mere existence of replicas questions the rigid framework and definition of the museum’s role and world, related to its social, educational and political commitments.

Acknowledgement of the shortcomings existing in current decision-making processes is paramount to relinquishing the guilt left behind by these ‘painful decisions’ (van de Vall Citation1999). In assessing the nature and importance of replicas, philosophical frameworks can play an indispensable role. Contemporary art conservators have a heightened necessity to keep up with the advancement of technology, which can indeed become overwhelming when moments of disconnection from it are imperative. On top of this, they should have an awareness that updating practices through the work of colleagues dealing with issues similar in nature (Foster and Jones Citation2019) is another pressing issue. Inter-disciplinary collaboration can provide different perspectives and a spectrum of expertise and experience. Although these problems may appear more demanding in the world of contemporary art, the truth is that they are overarching challenges in the world of conservation in general. We are all in the same boat, so we should strive towards helping and learning from each other by bridging our communication gaps.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers as well as Dr Joyce H. Townsend and Dr René Peschar for their valuable contributions during the editing process. Special thanks to Prof. David Scott, Ellie Sweetnam and the IIC for organising the symposium Conservation and Philosophy: Intersections and Interactions, which prompted the research that led to this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adorno, T. (1967) 1996. “Valery Proust Museum.” In Prisms, Translated by Samuel and Sherry Weber, 175–185. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Appelbaum, B. 2007. Conservation Treatment Methodology. Amsterdam; Boston: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Barok, D., J. Boschat Thorez, and A. Mansoux. 2020. “Naked on Pluto/Preservation”. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://monoskop.org/Naked_on_Pluto/Preservation.

- Barok, D., J. Noordegraaf, and A. P. de Vries. 2019. “From Collection Management to Content Management in Art Documentation: The Conservator as an Editor.” Studies in Conservation 64: 472–489. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2019.1603921.

- Baudrillard, J. (1976) 1993. Symbolic Exchange and Death: Theory, Culture and Society. London: Sage.

- Benjamin, W. (1935) 2008. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. London: Penguin.

- Bery, B. 2007. Inherent Vice: The Replica and its Implications in Modern Sculpture. Tate Papers 8. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/08/inherent-vice.

- Bunge, M. 1977. “Towards a Technoethics.” Bioethics and Social Responsibility 60 (1): 96–107.

- Chatzidakis, M. 2020. “Street art Conservation: Non-formal Education for Nonformal Art.” In The Impact of Conservation-Restoration Education on the Development of the Profession, edited by W. Baatz, N. Broers, and A. Hola, 126–143. Turin: ENCoRE and Centro Conservazione Restauro Venaria Reale.

- Chiantore, O., and A. Rava. 2012. Conserving Contemporary Art: Issues, Methods, Materials, and Research. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- de Boer, B., H. te Molder, and P. P. Verbeek. 2018. “The Perspective of the Instruments: Mediating Collectivity.” Foundations of Science 23 (4): 739–755. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10699-018-9545-3.

- Dekker, A. 2015a. “Authenticity in the Post-Digital Age, Your Time Is Now My.” Panel discussion with E. Balsom, A. Dekker, D. Jablonowski, and T. Vermeulen, June 21 2015, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam and De Appel Curatorial Program. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://vimeo.com/144351144.

- Dekker, A. 2015b. “The Challenge of Open Source for Conservation”. Performing Documentation in the Conservation of Contemporary Art, Revista de História da Arte 4: 124–132. Accessed January 30, 2021. http://revistaharte.fcsh.unl.pt/rhaw4/RHAw4.pdf.

- Eco, U. (1964) 1989. The Open Work, tr. Anna Cancogni. Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Edwards-Vandenhoek, S. 2015. “You Aren’t Here: Reimagining the Place of Graffiti Production in Heritage Studies.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies 21 (1): 78–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856514560309.

- Engel, D., and J. Phillips. 2019. “Applying Conservation Ethics to the Examination and Treatment of Software- and Computer-based art.” Journal of the American Institute for Conservation 58 (3): 180–195. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01971360.2019.1598124.

- Falcão, P., and T. Ensom. 2019. “Conserving Digital Art.” In Museums and Digital Culture: New Perspectives and Research, edited by T. Giannini and J. P. Bowen, 231–251. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-97457-6_11.

- Floridi, L. 2003. “Two Approaches to the Philosophy of Information”. In Minds and Machines 13: 459–469. Amsterdam: Kluwer Academic Publishers. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026241332041.

- Foster, S. M., and S. Jones. 2019. “The Untold Heritage Value and Significance of Replicas.” Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites 21 (1): 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13505033.2019.1588008.

- Frasco, L. 2009. “The Contingency of Conservation: Changing Methodology and Theoretical Issues in Conserving Ephemeral Contemporary Artworks with Special Reference to Installation Art”. In: Undergraduate Humanities Forum 2008–09: Change, 12. Accessed January 30, 2021. http://repository.upenn.edu/uhf_2009/12.

- Gordon, R., E. Hermens, and F. Lennard. 2014. Authenticity and Replication: The ‘Real Thing’ in Art and Conservation. London: Archetype Publications.

- Heidegger, M. (1954) 1996. The Question Concerning Technology and Other Essays. New York: Harper and Row.

- Hermens, E., and T. Fiske. 2009. Art, Conservation and Authenticities: Material, Concept, Context. London: Archetype Publications.

- Hermens, E., and F. Robertson. 2016. Authenticity in Transition: Changing Practices in Contemporary Art Making and Conservation. London: Archetype Publications.

- ICOMOS. 1964. The Venice Charter: International Charter for the Conservation and Restoration of Monuments and Sites. Venice: ICOMOS. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.icomos.org/charters/venice_e.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 1994. The Nara Document on Authenticity Nara: ICOMOS. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://www.icomos.org/charters/nara-e.pdf.

- ICOMOS. 2013. The Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance. Burwood, Australia: ICOMOS. Accessed June 22, 2021. https://australia.icomos.org/wp-content/uploads/The-Burra-Charter-2013-Adopted-31.10.2013.pdf.

- Ippolito, J. 2002. “Ten Myths of Internet Art.” Leonardo 35 (5): 485–498. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/002409402320774312.

- Jadzińska, M. 2011. “The Lifespan of Installation Art.” In Inside Installations: Theory and Practice in the Care of Complex Artworks, edited by T. Scholte and G. Wharton, 21–30. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Jokilehto, J. 1995. “Authenticity: a General Framework for the Concept.” In Proceedings of the Nara Conference on Authenticity, edited by K. E. Larsen, 17–34. Trondheim: Tapir Publishers.

- Jonas, H. 1979. “Toward a Philosophy of Technology.” The Hastings Center Report 9 (1): 34–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/3561700.

- Jones, C. 2004. “Seeing Double: Emulation in Theory and Practice. The Erl King Case Study.” Lecture, Annual Meeting of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works, Electronic Media Group, Portland, Oregon, June 2004.

- Kapelouzou, I. S. 2010. Harming Works of Art: The Challenges of Contemporary Conceptions of the Artwork. Unpublished doctoral thesis, Royal College of Art, London.

- Latour, B., and A. Lowe. 2011. “The Migration of the Aura, or How to Explore the Original Through its Facsimiles.” In Switching Codes: Thinking Through Digital Technology in the Humanities and the Arts, edited by T. Bartscherer and R. Coover, 275–297. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Accessed January 30, 2021. http://legacy.humanities.ufl.edu/pdf/latour_migration-of-aura.pdf.

- Laurenson, P. 2006. “Authenticity, Change and Loss in the Conservation of Time-Based Media Installations.” Tate Papers, 6. Accessed January 30, 2021. https://www.tate.org.uk/research/publications/tate-papers/06/authenticity-change-and-loss-conservation-of-time-based-media-installations.

- MacDowall, L. J., and de Souza Poppy. 2018. “‘I’d Double Tap That!!’: Street art, Graffiti, and Instagram Research.” Media, Culture and Society 40 (1): 3–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0163443717703793.

- Madsack, D. 2011. “Rapid Prototyping – Rapid Aging? Technology and Ageing Properties of Contemporary Art and Design Objects Made by Rapid Prototyping Technologies.” Lecture given at the Future Talks 011 conference, Munich 2011.

- Marçal, H. P. 2012. Embracing Transience and Subjectivity in the Conservation of Complex Contemporary Artworks: Contributions from Ethnographic and Psychological Paradigms. Unpublished masters thesis, Universidade Nova de Lisboa, Lisbon.

- Merrill, S. 2015. “Keeping it Real? Subcultural Graffiti, Street art, Heritage and Authenticity.” International Journal of Heritage Studies 21 (4): 369–389. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2014.934902.

- Mini, E., and S. Fragkiskou. 2019. The Conservation/Restoration of the Public Mural Knowledge Speaks, Wisdom listens by Wild Drawing (WD). Unpublished bachelors thesis, Department of Conservation of Antiquities and Works of Art, University of West Attica, Athens. [In Greek].

- Muñoz Viñas, S. 2005. Contemporary Theory of Conservation. Oxford: Butterworth-Heinemann.

- Nagy, E. E. 2021. “The Making of Mike Kelley's The Wages of Sin's Exhibition Copy: Replication as a Means of Preservation.” Studies in Conservation. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2021.1911095.

- Norton, A. 2016. “Migrating Facsimiles: When Copies Disappear from Conservation Control.” Studies in Conservation 61 (sup 2): 160–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00393630.2016.1181926.

- Oreianou, K. 2018. The Science of Conservation of Antiquities and Works of Art, the City as an Open-air Museum of Visual Creation, and Challenges of Social Inclusion: an Ooutreach Programme for Individuals in Drug Rehabilitation Process. Unpublished masters thesis, National Kapodistrian University of Athens. [In Greek].

- Paul, C. 2015. Digital Art. 3rd ed. London: Thames and Hudson.

- SBMK and TH Köln. 2019. The Decision-making Model for Contemporary Art Conservation and Preservation, 1–36. Accessed 20 June 2021. https://www.th-koeln.de/mam/downloads/deutsch/hochschule/fakultaeten/kulturwissenschaften/f02_cics_gsm_fp__dmmcacp_190613-1.pdf.

- Scott, D. A. 2016. Art: Authenticity, Restoration, Forgery. Los Angeles: UCLA.

- Tabatabaei, S. K., B. Wang, N. B. M. Athreya, B. Enghiad, A. G. Hernandez, C. J. Fields, J. P. Leburton, D. Soloveichik, H. Zhao, and O. Milenkovic. 2020. “DNA Punch Cards for Storing Data on Native DNA Sequences Via Enzymatic Nicking.” Nature Communications 11: 1742. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15588-z.

- van de Braak, K., E. Snijders, S. de Groot, H. van Keulen, and N. Krumperman. 2017. “The Effect of Materials and Production Processes Used in Selective Laser Sintering on the Durability and Appearance of Rapid-prototyped Art Objects”. In: ICOM-CC 18th Triennial Conference Preprints Copenhagen, ed. J. Bridgland, art. 0912. Paris: ICOM. ICOM-CC Publications Online (icom-cc-publications-online.org).

- van de Vall, R. 1999. “Painful Decisions: Philosophical Considerations on a Decision-making Model.” In Modern Art: Who Cares?, edited by I. Hummelen and D. Sillé, 196–200. Amsterdam: Foundation for the Conservation of Modern Art and Netherlands Institute for Cultural Heritage.

- Wenman, C. 2014. “3D Printing, 3D Capture, and Opportunities for Design Custodians”. Adapted from a presentation by Cosmo Wenman to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, Los Angeles. Accessed January 31, 2021. https://medium.com/@CosmoWenman/3d-printing-3d-capture-and-opportunities-for-design-custodians-7985097d2ac4.