Introduction

In February 1777, Imbert de St Paul, the French government’s inspector of manufactures at Nimes, witnessed a spinning jenny at work for the first time. An experienced member of the state industrial bureaucracy, he had already heard about the jenny, which had been introduced into France by one of his colleagues in 1771. Nevertheless, he had to confess it ‘is a very ingenious machine, though very simple, and seeing it work, we were all simply astonished we had failed to guess its secret’.Footnote1 Invented in England in the mid-1760s by the Lancashire weaver James Hargreaves, this simple but ingenious machine remains a familiar icon of the Industrial Revolution, its origins and its impact repeatedly interrogated in the search for explanations of Britain’s eighteenth-century economic transformation.Footnote2

The jenny features as a key technical breakthrough — a ‘macroinvention’ — in the two most influential recent interpretations of the Industrial Revolution: Robert Allen’s The British Industrial Revolution in Global Perspective and Joel Mokyr’s The Enlightened Economy: An Economic History of Britain, 1700–1850.Footnote3 For Allen the spinning jenny was a macroinvention because it was a new technology with big effects. Its importance lies in its impact, setting in train a long trajectory of advance that resulted in huge increases in productivity. It is ‘the industrial revolution in miniature’, the machine that exemplifies Allen’s argument that the demand for technological innovation was shaped by the relative prices of factors of production — for the jenny, principally labour and capital — in an eighteenth-century English economy characterised by high wages, but cheap capital.Footnote4

Mokyr, by contrast, insists that macroinventions are only very weakly related to economic forces, if at all, and that their precise timing is difficult, perhaps impossible, to explain. He presents them as radical new ideas that emerge without clear precedent, but have dramatic economic consequences.Footnote5 Less invested than Allen in the economic theory of induced innovation, he presents the jenny as just one of a cluster of macroinventions in cotton spinning that emerged in Lancashire between 1760 and 1780, a cluster that included Richard Arkwright’s water frame and Samuel Crompton’s spinning mule, ‘the ultimate spinning machine’.Footnote6 Insofar as Mokyr explores the particular causes and timing of these three inventions, he invokes not the narrowly specified economic variables addressed by Allen, but rather the general economic circumstances of the eighteenth-century cotton industry in Lancashire. To explain why the three emerged in cotton textile manufacturing and not in Britain’s staple woollen textile industry, which in the mid-eighteenth century was several times larger, Mokyr insists that cotton was more suited to mechanical spinning than other fibres.Footnote7 Of the three inventions, the jenny, described as ‘small and cheap’, receives the least attention, perhaps because its history reveals fewer traces of those linkages between artisanal knowledge and elite science that inform Mokyr’s broader interpretation of the Industrial Revolution.Footnote8

Does the jenny deserve its status as one of the key technical breakthroughs of the Industrial Revolution, as a macroinvention? In origin, it was, as Mokyr points out, a small, inexpensive, hand-powered machine, designed for use in a domestic setting. It could spin only weft yarn. Even in its later, larger, more technically sophisticated variants it was not powered by water or steam. Its contribution to the development of the Lancashire cotton industry was short-lived. By the early nineteenth century it was in rapid decline, confined to spinning the coarsest cotton yarns, though it enjoyed a much longer life in the woollen industry.Footnote9 Yet as Imbert de St Paul, the French inspector of manufactures, appreciated on first seeing it at work, the jenny combined simplicity, ingenuity and originality. That originality lay in the way it replaced the fingers of the human spinner with an inanimate mechanism, allowing the machine to incorporate multiple spindles controlled by a single operator.

In eliminating the need for the spinner’s fingers, the jenny had a parallel in Arkwright’s water frame and the earlier spinning machine patented in 1738 by Lewis Paul, on which Arkwright’s frame drew. However, the method used to replace the fingers was not the same. Hargreaves’ jenny and Arkwright’s frame differed fundamentally in the relationship between the process of spinning — drawing out the fibres and twisting them into yarn — and the process of winding — collecting the yarn on a spool once spun. In Arkwright’s machine the two processes were continuous. Spinning and winding took place at the same time, but the machine produced only a high twist yarn, most suited to warp. In the spinning jenny, the two processes were discontinuous, the machine alternating between spinning and winding. The result was a softer, lower twist yarn, suitable only for weft. The difference reflected the machines’ contrasting technical genealogies among hand spinning wheels and other earlier yarn-processing devices. The precursors of the continuous process employed in Arkwright’s water frame lay in silk throwing machinery and the flyer spinning wheel, mainly used for spinning flax. The model for the discontinuous process employed in the jenny was the simple spindle spinning wheel, used predominantly for spinning wool and cotton.Footnote10

Neither Mokyr nor Allen devote much attention to these genealogies, technical or material. For Mokyr, explaining precisely how and why each machine emerged is not a priority; for Allen, explanation lies in a narrow set of economic inducements. Nevertheless, the timing of the machines’ invention remains something of a mystery. The traditional explanation, dating from the mid-nineteenth century and still often repeated today, follows the logic of challenge and response.Footnote11 It holds that John Kay’s flying shuttle, patented in 1733, distorted the relationship between the spinning and weaving processes in cotton manufacture. By radically increasing output per weaver, the flying shuttle is said to have put unprecedented pressure on the supply of yarn, which relied on women working at the hand spinning wheel. The result was a bottleneck in the supply of yarn and increases in spinning wages, which encouraged labour-saving inventions.Footnote12 This explanation is inadequate, both chronologically and technically. The flying shuttle was little used in Lancashire cotton weaving prior to the invention of the jenny in the mid-1760s. Even then, its productivity benefits for cotton fabrics were limited, because most were less than a yard and a quarter wide, woven on narrow looms.Footnote13

Robert Allen highlights wages in his application of the theory of induced innovation to Hargreaves’ invention, but his emphasis is less on the earnings of Lancashire spinners, and more on the relationship between the costs of labour, capital and other factors of production across the British economy as a whole, which he characterises as a high wage economy. Insofar as Allen uses spinning wages to explain the timing of the invention of the spinning jenny, it is in terms of centuries rather than years or decades. He offers only six estimates for real English spinning wages between 1580 and 1767, all but one drawn from the evidence provided by contemporary commentators and none of them for spinning cotton in Lancashire. On the basis of this evidence, he concludes that ‘a woman earned one-third as much as a man at the end of the sixteenth century or in the first half of the seventeenth. By 1750 her earnings had jumped to two-thirds of male earnings’.Footnote14 He suggests these earnings were very high compared to those in other countries, offering an especially detailed comparison with France. His analysis has been challenged for employing questionable assumptions about earnings in both countries, as well as for its assumptions about working practices.Footnote15

Questionable, too, is Mokyr’s suggestion that special characteristics of cotton fibres made their mechanical spinning an easier problem to solve than mechanically spinning flax or wool. In fact, the opposite was true. John Platt of Platt Brothers, the great Oldham textile machinery firm, noted in 1866 ‘the special difficulties of dealing by machinery with so delicate and irregular a material as the raw cotton fibre’.Footnote16 Indeed, spinning cotton by hand is also considered to require more technical skill than spinning long-staple wool and flax, because of its shorter fibre length.Footnote17 However, the materiality, immediate circumstances and timing of invention are not Mokyr’s focus. He is more concerned to trace the roots of the key macroinventions of the British Industrial Revolution in what he calls ‘the great synergy of the Enlightenment: the combination of the Baconian program in useful knowledge and the recognition that better institutions created better incentives’.Footnote18

This article argues the origins and timing of one of the classic inventions of the British Industrial Revolution can be explained. To do so it adopts an explicitly comparative approach. It follows Robert Allen in offering an international comparison between the cotton industries of England and France.Footnote19 In addition, it employs a local comparison between the different textile industries of eighteenth-century Lancashire, which included not only cottons, but also worsteds, woollens, linens, silks and smallwares, in what was one of the nation’s most vibrant industrial regions. These comparisons are not confined to the relative prices of factors of production, the key issue for the economic theory of induced innovation. They extend to the organisation of work, the changing shape of product markets and the materiality of tools, machines, raw cotton, yarns and finished products.Footnote20

The article is divided into three sections. The first argues that, between the 1660s and the 1760s, the Lancashire cotton industry differed from its equivalents in continental Europe in ways that were crucially important for the invention of the spinning jenny. The second proposes that the invention of the jenny was, in part, a response to difficulties in the market for spinning labour, but only in one specific branch of Lancashire cotton manufacturing. The third and final section contends that, although the jenny was conceived as a domestic machine to be worked by women and children, it soon came to be enlarged and installed in workshops, where it was often worked by men. Its use in domestic settings was in rapid decline from the mid-1780s.

The Peculiarities of Lancashire’s Cotton Industry, 1660–1760

Between the twelfth-century beginnings of fustian manufacturing in Italy and the onset of the Industrial Revolution, usually dated to about 1760, cotton spinning spread across many parts of western Europe.Footnote21 A large but difficult-to-judge proportion of the yarn produced was destined for candlewicks, for which cotton was the best, though most expensive material available, coarse spun from the cheapest, low grade, raw cottons.Footnote22 Of the rest of the cotton yarn produced, the majority went to serve as weft in mixed fabrics, mainly those, like fustians, where it was combined with linen or hemp warps. In English, these mixed fabrics came increasingly to be referred to simply as ‘cottons’.

Large-scale fustian manufacture began in Britain around the turn of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, principally in Lancashire. Lancashire fustians copied fabrics already being made in northern Italy and southern Germany, largely in the twill weave so characteristic of fustian.Footnote23 The manufacture of similar mixed cotton-linen fustians was introduced into various cities in France about the same time. Roughly a century later, cotton wefts and linen warps began to be combined in lighter, plain-weave fabrics, particularly stripes and checks, a response to rapidly growing imports of all-cotton textiles from India. In Britain this new manufacture of lighter cotton-linens developed principally in Lancashire, alongside the established production of fustians such as thicksets, pillows and jeans.Footnote24 In France, its major centre was Rouen in Normandy, which had not previously been a centre for the manufacture of fustians on any scale.Footnote25 By the 1720s, Lancashire was producing plain-weave, unbleached cotton-linen fabrics known as Blackburn greys, for printing with Indian colour-fast techniques.Footnote26 France’s 1686 ban on printed fabrics inhibited an equivalent development in Normandy, but it did occur in other continental European centres, for example in Switzerland.

As far as fibre-mix and product-mix are concerned, therefore, the manufacture of cottons in Lancashire between 1660 and 1760 shared important features with other centres of cotton manufacturing in Europe. In other crucial respects, Lancashire was different, especially with regard to spinning. In spinning, there were three broad areas of divergence.

(i) Raw Materials

Lancashire was the only major European centre of cotton manufacturing before the mid-1730s to use predominantly New World raw cotton ().Footnote27 Other centres, including Switzerland, relied principally on raw cotton from the eastern Mediterranean — often termed Levant cotton — and continued to do so into the late eighteenth century.Footnote28 The main exception was Normandy, but it began to import large quantities of raw cotton from the French West Indian islands only in the late 1730s and thereafter suffered severe supply interruptions during the wars of the mid-eighteenth century. Normandy remained heavily reliant on Levant cotton. In war years it largely replaced New World cotton, while even in the years of peace during the early 1750s it accounted for close to 40% of the region’s raw cotton supply. Indeed, imports of Levant raw cotton to France saw dramatic growth between the start of the eighteenth century and the 1780s, mainly in return for exports of French woollen textiles, which increasingly dominated Ottoman markets.Footnote29

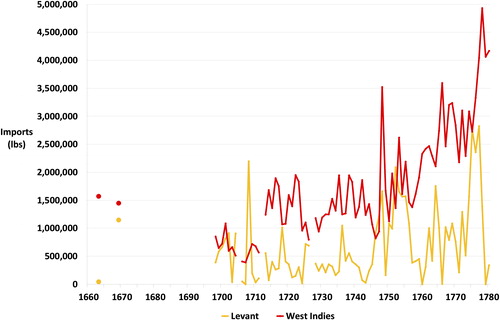

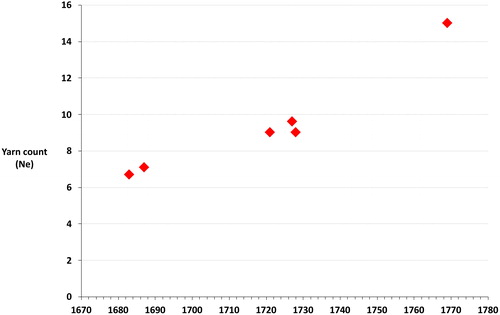

Fig. 1. Imports of raw cotton by origin, England, 1660–1780. Sources: A. P. Wadsworth and J. de L. Mann, The Cotton Trade and Industrial Lancashire, 1600–1780 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1965), pp. 520–21; British Library, Add. MS 36,785: ‘Accompt of the exports from and imports into the City of London’, 1663 and 1669.

England, by contrast, started importing New World cotton from Barbados during the 1630s, in what Russell Menard calls the island’s ‘cotton boom’, which preceded the more familiar Barbados sugar boom of the 1640s and 1650s.Footnote30 After 1660 Jamaica and other British Caribbean islands also began to supply raw cotton. Available statistics for the later seventeenth century are incomplete, but across the period 1660 to 1780 the available data shows that imports of West Indian raw cotton were almost always larger, and often very much larger, than those of Levant cotton. Imports of spun cotton yarn were small and declining. New World raw cotton was especially important in Lancashire. In the mid-1760s, it was estimated that 82% of the raw cotton used in Lancashire came from the New World and only 18% from the Old World. In these years Lancashire consumed three-quarters of English raw cotton imports from the Caribbean, but only a third of those from the Levant.Footnote31

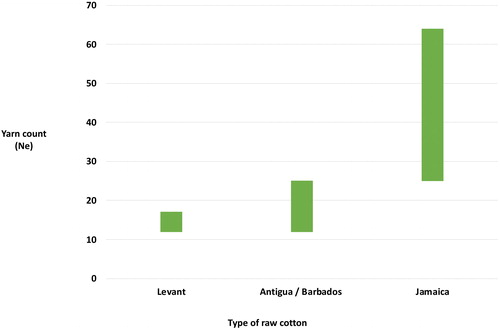

West Indian cotton outpaced Levant cotton in Britain despite being consistently more expensive (see ). The cost differential reflected the superior quality of New World cotton, which lay principally in the length of its cotton fibres, but also in their strength and fineness. The two American species of cotton both have longer fibres (staples) than the two Old World species, which make them more suitable for finer yarns (). These differences emerge clearly in modern studies of cotton biology, but they were already familiar in the eighteenth century. When the trainee French Inspector of Manufactures, François Latapie, asked a Rouen merchant about the cottons available in 1773, he was told that cottons from the French Caribbean territories of Cayenne (now French Guiana) and St Domingue (now Haiti) were considered the best, for their pure white colour, lustre, suppleness and ease of spinning, but they were scarce. Most plentiful was cotton from the Caribbean island of Guadeloupe, but it was redder and somewhat shorter in staple. Levant cotton he dismissed as ‘the type that is least valued. It is short and hard.’Footnote32

Table 1. Average Fibre Length in the Four Cultivated Species of Cotton (Genus Gossypium)

(ii) Industrial Organisation

Across early modern Europe, spinning textile yarns was undertaken by women and children in their homes and, to a lesser extent, in welfare institutions. There was a markedly gendered division of labour, with weaving of the yarn into fabric being undertaken mainly by men. This manner of organising industrial work was predominantly domestic, but there was no single domestic system.Footnote33 When spinning was undertaken in the spinner’s household, the flow of materials into and out of the spinner’s hands could be organised in a variety of ways.

Sourcing of raw fibre could take three broad forms. First, the spinner might spin a fibre such as flax, hemp or wool grown on her household’s farm or plot. In most of western Europe, this was not an option for cotton, because it was not grown. Second, as was the case for other textile fibres, the spinner might buy small quantities of raw cotton to spin on her own account. The spinner then had the option of either household autoconsumption — putting the yarn to use in her own household — or securing an income in money or in kind by selling the yarn to an outsider, who might be a local village weaver, but might equally be a heavily capitalised yarn merchant or manufacturer. Third, in the more industrialised parts of Europe, the spinner often had the option of spinning yarn in her own home for a wage, usually calculated at a piece rate, from an employer who supplied the raw fibre under the putting-out system.

Examples of all three modes of organisation could be found among spinners of various fibres in both Britain and France. However, during the eighteenth century there was a marked contrast between the principal cotton spinning regions in the two countries — Lancashire and Normandy. In Lancashire, from at least the 1680s, most spinning of cotton was organised on a putting-out basis, generally by agents employed by medium- and large-scale manufacturers, who then received back the yarn and put it out to be woven into fabric by weavers who did not necessarily live in the same locality as the spinner.Footnote34 In Normandy, by contrast, cotton spinning was generally a separate, small-scale commercial activity, conducted by women who spun on their own account. John Holker, the Lancashire Jacobite émigré who became one the French government’s industrial inspectors, recommended in the early 1750s that Rouen manufacturers should buy the raw cotton themselves and use putting-out agents in the places spinning was done, instead of relying on people ‘who buy cotton wool and resell it in small lots to the spinners’. Nevertheless, thirty years later, in the 1780s, the English agricultural journalist Arthur Young noted that spinners in Normandy continued to ‘buy their cotton, spin it, and then sell the yarn’.Footnote35 The same was true in a number of other regions of France which subsequently developed cotton spinning in the course of the eighteenth century, although there were exceptions, as in the vicinity of Lille.Footnote36

(iii) Processes and Techniques

Spinning was not simply a matter of sitting at a spinning wheel and turning raw cotton into yarn. The raw cotton, which arrived in western Europe in large, tightly packed bales or bags weighing more than 150 lb, had to be opened, loosened out, cleaned of any dirt, seeds and other impurities, carded by wooden cards studded with metal teeth into a consistent form that the spinner’s fingers could draft, spun at a spinning wheel or with a hand spindle, then prepared into hanks or skeins for delivery into the weaving process. If we examine these different processes, we discover, once again, a marked contrast between mid-eighteenth-century Lancashire and Normandy.

In both Lancashire and Normandy, spinners received raw cotton already broken down into small parcels, weighing two or three pounds. This cotton usually required additional loosening and cleaning. From that stage onwards English and French practice diverged. In Lancashire, the cotton was first washed with soap, which dampened and oiled it, making it easier to card.Footnote37 For carding, two hand cards were used to form the cotton into a loose mass that was consistent and of the correct density for spinning. The Lancashire cotton cards had short, sharp, half-hooked teeth, all of equal length, made from iron wire with hand-operated machines. These teeth were mounted diagonally at equal intervals in supple leather to provide elasticity. The slots for the teeth were also made by a hand-operated machine, which ensured uniformity.Footnote38 These cotton cards were expensive. During the 1740s and 1750s, the Latham family of Scarisbrick in west Lancashire paid 30d a pair, compared to only 15d a pair for cards for sheep’s wool.Footnote39

At the end of the carding process, the loose mass of cotton was formed into tubes or slivers, which were joined together. These tubes were transformed into a roving or slubbing — a loosely spun, but very coarse proto-yarn — by the carder on a hand spinning wheel. This roving was then spun a second, final time into finished yarn of the required fineness by ‘another woman who perfects it … according to what is necessary to use it in the fabric for which it is intended and to avoid spoiling the spinner’s hand’.Footnote40 The spinning wheel used for cotton spinning in Lancashire was a small, non-flyer 20-inch wheel with an expensive steel spindle, known as a fustian or cotton wheel, at which the spinner could sit as she spun ().Footnote41 The ratio of carders to final spinners was described by John Holker in 1755: ‘There have always been for 3 [final spinners] one who cards and begins to spin coarse … The 3 each pay her a third of their earnings’.Footnote42

Fig. 2. Carding, roving and spinning cotton by hand in Lancashire, as illustrated in Richard Guest, A Compendious History of the Cotton Manufacture (Manchester, 1823), pl. 3. Note: Two hand cards lie on the floor. The woman on the right is spinning coarse rovings from carded raw cotton. The woman on the left is spinning the coarse rovings into fine yarn.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The finished yarn was spooled on the spinning wheel and then removed to be reeled into hanks. Reeling was a means of arranging the yarn into convenient bundles, but it could also be a way of measuring and policing its fineness, and hence its quality. If a reel was of a standard length or circumference, and a hank consisted of a standard number of turns, then the number of hanks per pound weight provided a measure of the yarn’s fineness, termed its count. Reels were adapted to enhance this process. Circular snap reels made a sound after a certain number of revolutions, while clock reels had a clock-like face with a pointer indicating the number of revolutions.Footnote43 This was the system that prevailed in the Lancashire cotton industry by the later seventeenth century, although the use of industry-wide standard reels in English textile manufacture can be traced back to the new worsted manufactures established in eastern England during the second half of the sixteenth century.Footnote44 Lancashire cotton yarn was reeled on a 54-inch circumference reel. A hank consisted of 560 turns of the reel, in other words 840 yards. The count of a cotton yarn was the number of these hanks per pound weight. Under this measuring system, the higher the number, the finer the yarn. It came to be known in eighteenth-century France as ‘le tarif anglois’ and remains in international use as English cotton count, with the letter symbol Ne.Footnote45

Whereas Lancashire cotton spinning was broken down into an extended series of separate tasks, each employing specialised equipment and labour, hand cotton spinning in Normandy involved fewer tasks, less labour and less costly equipment. The raw cotton was not washed before carding. French cards were hand-made, and their wire teeth were cut irregularly, aligned inconsistently and mounted rigidly. A mid-eighteenth-century French report concluded, ‘French cards are very inferior in all respects to cards from Holland and England’, but they were cheaper.Footnote46 The raw cotton was carded less thoroughly than in England, but more quickly, because French cards could be loaded with more cotton. After carding, it was taken directly off the cards as loquettes (short cardings or slivers) and given its final spinning in that state, without the intermediate step of coarse spinning into rovings. The spinning wheel employed was the large great or walking wheel with an iron spindle, otherwise used for spinning sheep’s wool, at which the spinner stood upright ().Footnote47

Fig. 3. Hand-spinning cotton on a great wheel, Normandy, 1773. Source: Archives Nationales (France), F12/560: M. Latapie, ‘Réflexions préliminaires’, 1773.

After spinning, the yarn was reeled, but into hanks of a variety of lengths. There was no industry-wide standard or regulation for either the dimensions of the reel, or for how many turns of the reel comprised a hank. In 1773 an inspector of manufactures visiting Rouen noted, ‘not all the reels are of the same size, which results in considerable variation in the hanks’.Footnote48 Twenty years previously, the Lancastrian John Holker had been more blunt, complaining that the cotton spinners in Normandy simply spun the yarn as they pleased (‘à leur fantaisie’).Footnote49

At the heart of these contrasts between mid-eighteenth-century cotton spinning in Lancashire and Normandy was quality, for which the most important consideration was cotton fibre length. Lancashire’s long-established use of long-staple, New World cotton allowed finer, more expensive, higher-count yarns to be spun (). Using finer yarns resulted in final products that were superior in quality and commanded a higher price.

Fig. 4. Yarn counts spun from different types of raw cotton, Lancashire, c. 1752. Source: ‘Tarif des differents prix que l’on paye en Angleterre aux fileuses pour chaque livre de coton, eû égard à la grosseur ou à la finesse de chaque livre de fil, filé’, in Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris, 2723/5: ‘Mémoire sur les filatures de coton en Angleterre, par Holker, traduction de Morel’, fols 129–33.

At Rouen in 1750, just over a decade after the town began to receive large imports of New World cotton, it was the soft and silky cottons from the French West Indian islands that were ‘destined for the manufacture of goods of superior quality’. As for cottons from the Levant, ‘consisting of a hard, short wool, their spinning can be neither beautiful nor even, so they are normally used in common siamoises [cotton-linen stripes and checks] and other coarse manufactures’.Footnote50

Quality also depended on processes and techniques. The stiff, rough, irregular cotton cards used in Normandy tore the fibres, compromising their quality, especially the quality of the longer-staple New World cottons, and produced a hairy, uneven yarn.Footnote51 In France, uneven yarn also resulted from the failure to coarse spin the cardings into rovings before the final spinning, as well as from the use of the great wheel rather than the smaller English cotton wheel.Footnote52 Crucially, the lack of a standard reel for cotton in Normandy made it difficult to secure the specific yarn counts required for different fabrics, or to pay for spinning according to the fineness of the yarn, incentivising the spinners to spin higher, more valuable counts.

The difficulty was exacerbated by the way spinning was organised in Normandy. In the absence of standard measurements, specification of fibre quality and yarn quality, as well as the challenge of policing specifications, was managed through a series of market transactions between spinners, yarn dealers and the manufacturers who arranged the weaving of the yarn into finished fabric. Under the putting-out system that prevailed in Lancashire, these transactions were internal to the manufacturing firm, making it simpler to align fibre quality with yarn quality and with spinners’ skill and remuneration, all regulated according to the industry-wide yarn quality measure.

Why the Spinning Jenny?

The distinctive characteristics of the early modern Lancashire cotton yarn production system underpinned the invention of the spinning jenny. Nevertheless, understanding the precise form taken by the jenny and the timing of its invention also requires attention to its immediate Lancashire context, specifically to the Lancashire industry’s performance in the middle decades of the eighteenth century and to local circumstances in the vicinity of Oswaldtwistle, where James Hargreaves lived, worked and constructed his first jenny.

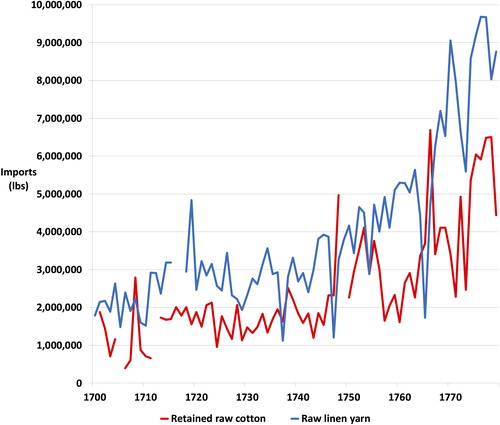

The 1750s and 1760s, when the jenny was conceived and initially developed, emerge as particularly challenging decades for the Lancashire cotton industry, due to a combination of unprecedented expansion and unprecedented obstacles. It was an industry producing fabrics made overwhelmingly from combinations of cotton yarn and linen yarn. Both were largely imported. Raw cotton came predominantly from the West Indies, and to a limited extent from the Levant, to be spun locally. Linen yarn arrived, ready-spun, from the Baltic, from Ireland and, to a lesser extent, from Scotland. The best statistical indicator of the industry’s fortunes is therefore provided by the quantities of these two materials imported from overseas, considered together (). A large proportion of both the raw cotton and the linen yarn imported into Britain was employed in Lancashire.

Fig. 5. Imports of raw cotton and linen yarn, England, 1700–1779. Sources: The National Archives, CUST 3/70-9; E. Schumpeter, English Overseas Trade Statistics, 1697–1808 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1960), table 16.

Between the 1720s and the 1740s, both domestic and overseas demand were fairly stagnant, although the period saw developments in plain-weave lighter fabrics such as stripes, checks and Blackburn greys for printing. From the late 1740s, however, imports of raw materials increased. There was strong growth in the domestic market for the industry’s traditional and especially its newer products. At the same time, novel opportunities arose overseas among the rapidly growing populations of the British North American colonies and also in the African slave trade. A combination of contracting Indian supply and rising Indian prices enabled Lancashire manufacturers to establish a strong presence in the West African market with cotton-linen versions of Indian all-cotton checks and stripes, even though Indian fabrics continued to be preferred by African traders supplying slaves.

The capacity of Lancashire manufacturers to respond to these opportunities was hampered by rising costs, both for spinning labour and for raw and intermediate materials. Labour costs are especially difficult to gauge, because no sustained runs of wages actually paid to Lancashire hand cotton spinners survive. However, the long-term trajectory of labour costs in Lancashire across the century before 1770 can be reconstructed, using Lancashire manufacturers’ business records and probate inventories.

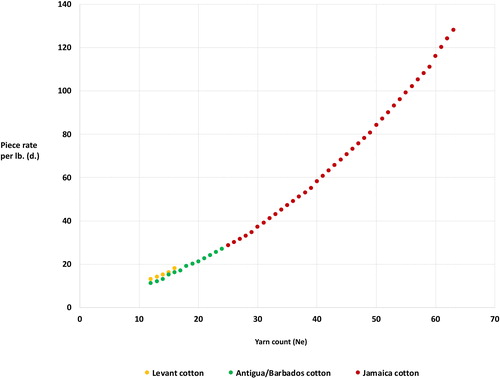

Labour costs increased during that century, for two reasons. First, the average count of the cotton yarn being spun increased, from a very coarse average count of Ne 7 during the late seventeenth century, to between Ne 9 and Ne 10 in the 1720s, to over Ne 15 by the late 1760s ().Footnote53 This increase in the fineness of yarn partly reflected the industry’s shift to lighter fabrics, especially stripes, checks and Blackburn greys, but there may also have been a shift towards lighter versions of traditional fustians. The shift to lighter fabrics brought about an increase in labour costs because, in Lancashire, where yarn was reeled to a fixed standard, every increase in the yarn count earned an increase in the piece rate per pound spun. The rate of increase was steep. For the more commonly used yarns in the 1750s, an increase of one in the yarn count secured an increase of about a penny per pound on the rate. So while spinning a pound of West Indian cotton to Ne 12 earned 11d for each pound spun, spinning it to Ne 24 secured 27d. Spinning finer counts took considerably more time and skill than spinning coarser counts. Nevertheless, spinners had an incentive to climb the quality ladder ().

Fig. 6. Average yarn count of cotton weft spun for six Lancashire manufacturers, 1683–1769. Note: The Ne values plotted here are weighted averages of the Ne values of the various counts held by each manufacturer. Sources: see Appendix.

Fig. 7. Piece rates for spinning cotton according to yarn count, Lancashire, c. 1752.

Source: ‘Tarif des differents prix que l’on paye en Angleterre aux fileuses pour chaque livre de coton, eû égard à la grosseur ou à la finesse de chaque livre de fil, filé’, in Bibliothèque Mazarine, Paris, 2723/5: ‘Mémoire sur les filatures de coton en Angleterre, par Holker, traduction de Morel’, fols 129–33.

In addition, there appears to have been an upward shift in the level of piece rates overall. As was often the case with eighteenth-century wage payments, customary piece rates for cotton spinning remained stable for long periods, but were subject to short-term adjustments — deductions or advances — depending on trade conditions. As a consequence, establishing long-term trends from spot prices is perilous.Footnote54 However, the rates paid for spinning cotton in Lancashire do appear to have undergone a long-term increase across the century up to 1770, by as much as 50%, which is probably too large a change to be accounted for by short-term adjustments alone. In the 1680s each one count increase in the fineness of a typical coarse yarn was worth an additional 0.75d on the piece rate per pound. By the 1740s and early 1750s it was worth approximately 1d extra. By 1769 it was worth 1.25d.Footnote55

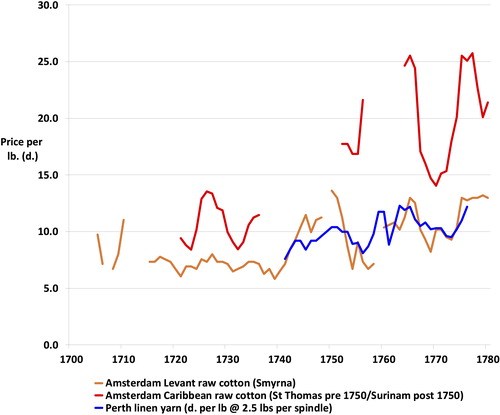

Cost pressures on Lancashire’s cotton manufacturers in the mid-eighteenth century were not confined to wages. There were also dramatic increases in the prices of materials. There are no surviving local price series for either raw cotton or linen yarn. Both commodities were, however, sourced at a distance and widely traded internationally, so available price series from Scotland and Amsterdam can provide evidence of trends, even if the prices they quote were not those actually paid in Lancashire ().Footnote56 Amsterdam raw cotton prices doubled in the course of the 1740s. They were subsequently extremely volatile, with very high peaks. Scottish linen yarn prices rose, too, especially in the 1740s and the later 1750s, following the same trajectory as raw cotton, but less dramatically. Nevertheless, linen yarn continued to be substantially cheaper than cotton yarn, selling at around half of its price per pound, or less.

Fig. 8. Raw cotton prices at Amsterdam, the Netherlands, and linen yarn prices at Perth, Scotland, 1700–1780. Sources: Cotton: MEMDB, Prices (Posthumus) and Harvard Business School, Baker Library, Kress Collection, ‘Notitie der prysen van diverse waaren’, Amsterdam, 1709–1787, vols 1 and 2; Linen: A. Bald, The Farmer and Corndealer’s Assistant (Edinburgh, 1780).

An expanding, higher-quality product range, increasing demand, rising labour costs, soaring material costs — were these the short-term economic inducements that impelled James Hargreaves to invent the spinning jenny in the mid-1760s? The limited evidence available indicates the Lancashire cotton industry produced a number of attempts in this period to develop multi-spindle machines for spinning cotton, although interest in Britain in mechanical cotton spinning was not new. It dated back to the less economically pressured environment for cotton manufacturing of the 1720s and 1730s.Footnote57 Some of the same pressures, moreover, affected other textile industries in the 1750s and 1760s, especially worsteds and sailcloth in the north of England, without inducing technical innovation.Footnote58 In order to understand the precise form taken by James Hargreaves’ invention, we need to consider how the impact of the economic pressures of those decades on the Lancashire cotton industry varied according to the material make-up of its products and the ways work was organised. Technical innovation was not necessarily the appropriate response.

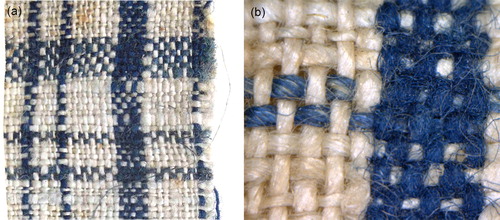

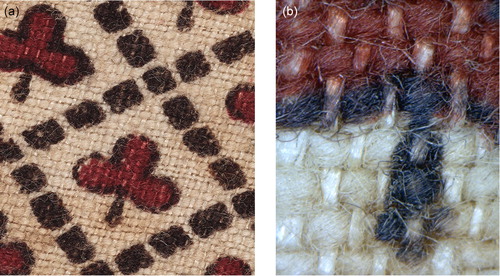

As we have seen, the vast majority of the textiles that comprised the Lancashire ‘cotton’ industry before 1770 were mixtures of cotton and linen. However, the ratio of cotton yarn to linen yarn was not fixed. Many of the checks and stripes, for example, contained a good deal more linen than cotton. The survival of five thousand fabric swatches left with babies at the London Foundling Hospital between 1742 and 1760, consisting largely of the newer, lighter, plain-weave cotton-linen fabrics of the types manufactured in Lancashire, enables us to employ microscopic analysis to assess the fibre content of a significant proportion of the Lancashire industry’s output on the eve of the Industrial Revolution ().Footnote59 Most of the mixed-fibre checks and stripes contained more linen yarn than cotton yarn. In checks and stripes, often it was only the more richly coloured yarns that were cotton, while all the rest were linen (). Among the Foundling Hospital’s cotton textiles, it is only the Blackburn greys, the fabrics produced in Lancashire for printing with wooden blocks in the printing works that ringed London, that have an exclusively 50:50 ratio of cotton yarns to linen yarns.

Fig. 9. Cotton-linen check, 1759: (a) photograph, (b) micrograph captured with a Dino-Lite AM7013MZT portable microscope at ×60 magnification. Note: All the white yarns and the horizontal blue yarns are smooth linen. Only the vertical blue yarns are fluffier cotton. The take-up of the blue dye on the horizontal linen stripes is poor, in contrast to the deep blue of the wider vertical stripes, which are cotton. Source: London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/9/1/149: Foundling Hospital, Billet book, July 1759, Foundling no. 13416.

Image copyright London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. © Coram.

Table 2. Yarn Fibre Combinations in Printed, Checked and Striped Fabrics Made From Cotton and/or Linen, London Foundling Hospital Billet Books, July 1759 and January 1760

Where a strict 50:50 ratio between the two fibres was not essential, trade-offs were possible. Any inducement to cut costs by technical innovation was reduced. Linen yarn prices rose from the later 1740s at the same time as the prices of raw cotton, but the increase in linen yarn prices was more muted. Linen yarn remained substantially cheaper than cotton yarn. Indeed, the cost of spun linen yarn suitable for many Lancashire fabrics was close to that of unspun, low-quality Levant cotton (). So, for fabrics like checks and stripes where the cotton:linen ratio varied, substitution of cheaper linen yarn for costlier cotton was a feasible cost-reduction strategy. According to the Manchester merchant and checkmaker Samuel Touchet, in 1750 ‘the high price of cotton had obliged them to use coarse linen instead’. Consequently, one type of fabric, ‘which used to be made all of cotton one way, was now made not above ¼ part cotton: and in another species, ¼ part less cotton was used than formerly’. Wholesale purchasers were all too aware of this tactic. A Manchester merchant partnership was informed in 1772 that a New York purchaser had ‘complained of the checks having some threads of blue linen mixed with the cotton, but [I] told him there certainly was as much cotton in them as could be afforded for the price.’Footnote60

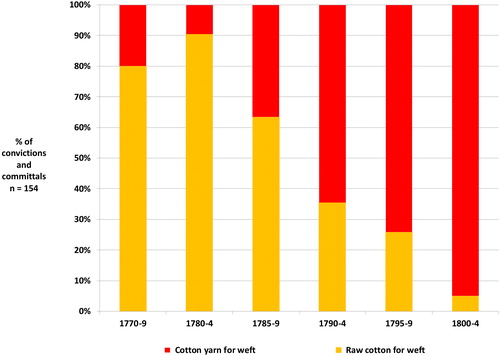

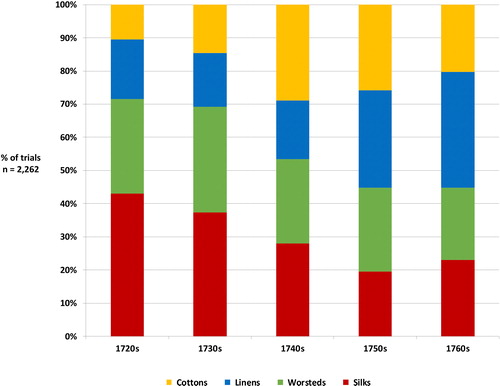

This option was not available to manufacturers of Blackburn greys for printing. A 50:50 cotton to linen ratio, with a thick, fluffy, richly coloured cotton weft and a finer, smoother and less visible linen warp, was essential for producing the desired printed finish (). Linen yarns absorbed dyes less well than cotton yarns. The combination of a thick cotton weft and a fine linen warp was contrived to minimise the visual impact of this difference. Reducing the proportion of cotton yarn in each piece of cloth any further would have given the pattern an unbalanced, more speckled appearance.Footnote61 A similar obstacle to reducing the 50:50 ratio of cotton weft to linen warp applied to many of the older, heavy fustians characterised by a cut and raised surface, which relied on their cotton weft.Footnote62 Yet during the middle decades of the eighteenth century Blackburn greys were the more successful product, the British-made substitute for the Indian all-cotton calicoes that were the base material for Indian chintzes, banned in Britain. It was estimated in the mid-1760s that Blackburn greys accounted for 18% of the output of the expanding Lancashire cotton industry, even though they had not existed at the start of the eighteenth century.Footnote63 Trials for theft at the Old Bailey, the principal criminal court for London, suggest printed Blackburn greys and other cotton-linen gown fabrics took a huge bite out of the market for women’s gowns during the 1730s and 1740s, but as raw cotton prices rose in the 1750s the progress of gowns made with cotton stalled. Prints on cheaper Irish or German all-linen fabrics ate into their market, despite inferior colouring ().

Fig. 10. Printed cotton-linen fabric (Blackburn grey), 1760: (a) photograph, (b) micrograph captured with a Dino-Lite AM7013MZT portable microscope at ×60 magnification. Note: The take-up of the colours on the vertical linen warp yarns is poor, producing a speckled effect. Source: London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/9/1/166: Foundling Hospital Billet Books, January 1760, Foundling no. 15149.

Image copyright London Metropolitan Archives, City of London. © Coram.

Fig. 11. Gown fabrics in criminal trials at the Old Bailey, London, 1720–1769. Source: Old Bailey Proceedings (http://www.oldbaileyonline.org). Keyword searches for gowns and bed gowns identified by the following textile names (and alternative spellings): cotton, fustian, linen, lawn, Holland, worsted, stuff, camblet, calamanco, serge, poplin, crape, grogram, russel, silk, satin, tabby, lustring, velvet, paduasoy, silk damask, shagreen.

The production of Blackburn greys was highly localised. According to John Holker, Blackburn, ‘with its neighbourhood … is the only town where these goods are made, which are sent to London, there to be sold, bleached and printed’.Footnote64 They were the principal fabric woven at Oswaldtwistle, only three miles from Blackburn, where James Hargreaves worked as a cotton weaver for most of the 1750s and 1760s. During these decades, the impact of rising input prices on their manufacture was not confined to the cost of materials. Blackburn greys faced another pressure, an acute shortage of spinning labour, as a result of the way the textile industries had developed in Lancashire during the first half of the eighteenth century.

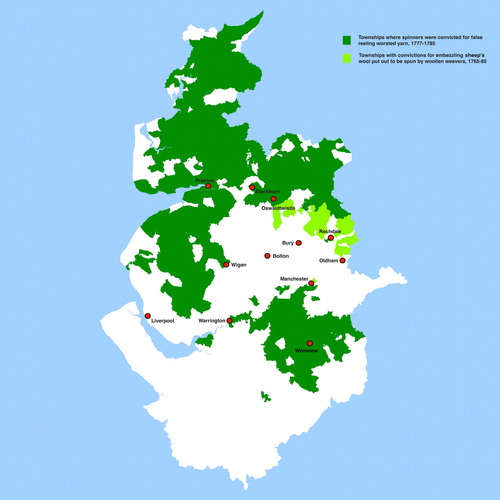

Spinners were predominantly female. Systematic evidence about women’s employment in the eighteenth century is notoriously poor. Consequently, establishing the geographical incidence of any one type of spinning often can be done only indirectly. The only systematic sources for the geographical distribution of spinning in Lancashire and Cheshire from 1765 to 1789 derive from two sets of convictions for summary offences — frauds in yarn measurement by spinners of worsted yarn and embezzlement of short-staple sheep’s wool put out to spin to clothiers and weavers in the Rossendale area of Lancashire. There are no equivalent sources for cotton or flax spinning. Nevertheless, convictions of worsted and woollen spinners make it clear that the core area of Lancashire’s cotton industry, between Blackburn, Wigan, Manchester and Oldham, was hemmed in to the north, the west and the south (as well as over the Yorkshire border to the east) by areas where worsted and woollen spinning offered an alternative employment for women at attractive wages (). To the south-west there was also flax and hemp spinning, especially around Warrington for its sail-making manufactory. Nationally insignificant before 1740, sail-making in south-west Lancashire burgeoned during the 1740s and 1750s, benefiting from the growth of the port of Liverpool, from naval demand during the wars of the mid-eighteenth century and from state encouragement for the manufacture of sails in Britain. By 1756, nearly a third of the Navy’s orders for sailcloth went to Warrington, with most of the yarn spun either in or near Warrington, or in the surrounding districts.Footnote65

Fig. 12. Lancashire and Cheshire townships with convictions for frauds in worsted or woollen spinning, 1765–1785. Sources: Lancashire Record Office, QSB/1: Lancashire Quarter Sessions Recognisance Rolls, summary convictions for embezzlement and associated offences, 1765–1786; Greater Manchester Record Office, GB 127.MS f 338.4 W1: ‘An Account of Frauds and Embezzlements Committed by the Spinners and Others Employed in the Worsted Manufactory’, 1778–1783.

Like cotton, these were buoyant, rapidly expanding industries. Indeed, worsted manufacturing, with its core weaving area over the Yorkshire border around Halifax, was a more recent arrival in the north of England than cotton. Whereas Lancashire started making fustians with cotton at the end of the sixteenth century, worsteds emerged in Yorkshire on any scale only at the end of the seventeenth.Footnote66 Predominantly an export industry, Yorkshire worsteds grew very rapidly during the first half of the eighteenth century, probably faster than Lancashire cottons. They boomed during the 1750s and early 1760s. By the 1770s they accounted for half of Britain’s output of worsted fabrics and nearly 20% of all British woollen textile production.Footnote67 In 1772 it was estimated that the annual output of the Yorkshire worsted industry was worth £1.4 million, more than the £1.2 million estimated for the Lancashire cotton industry less than a decade before. Yet the Yorkshire worsted industry had hardly existed seventy years earlier.Footnote68

In worsteds the ratio of spinners to weavers was especially high, so to secure a supply of yarn the Yorkshire manufacturers were obliged to source yarn from an enormous area up to 50 miles away across the West and North Ridings of Yorkshire, as well as adjacent parts of Lancashire and Cheshire.Footnote69 This was a dynamic process. In the course of the eighteenth century, the worsted spinning frontier expanded further and further from the core weaving area in Yorkshire. Competition for labour, arising from ‘the great number of the master manufacturers and the rivalship consequential thereon’, boosted worsted spinners’ wages and perquisites, although piece rates at the frontier remained lower than those at the core.Footnote70 The landowner and miniature painter Samuel Finney, looking back in 1785 at the history of his native township of Wilmslow in Cheshire, recalled that earlier in the eighteenth century the women and children were employed in making silk- and mohair-covered buttons. As fabric-covered buttons became less fashionable around mid-century, the work was replaced by worsted spinning introduced by manufacturers from Yorkshire.Footnote71 Yet Wilmslow was only 10 miles south of Manchester, the capital of the Lancashire cotton trade.

We may lack direct evidence about the precise extent of cotton spinning in Lancashire in the 1760s and 1770s. Nevertheless, the distribution of woollen and worsted spinning, combined with what we know about flax spinning around Wigan and Warrington, indicates that the area devoted exclusively to cotton spinning was hemmed in and surprisingly small. The reason is simple. As we have seen, the vast majority of the textiles that comprised the Lancashire ‘cotton’ industry before 1780 consisted mainly, or at least half, of linen yarn. By the 1750s, little of the linen yarn used in these Lancashire-woven fabrics was spun by Lancashire women. Most was sourced in Ireland, on the shores of the eastern Baltic, or to a much lesser extent in Scotland. As a consequence, the geography of spinning for the Lancashire industry was very different from the Yorkshire worsted industry. In Lancashire, less than half the yarn woven (the cotton) was spun within the region, so the spinning field was geographically far less extensive at any level of output than that of the Yorkshire worsted industry, which sourced almost all its yarn, both warp and weft, locally.

Hemmed in by spinning for these other, successful textile industries, a new way of organising the spinning of cotton yarn emerged in the middle decades of the eighteenth century, as production expanded, raw cotton prices rose and spinning labour became increasingly scarce. About 1750, manufacturers of fustians and Blackburn greys began to put out raw cotton for spinning to their weavers each time the weaver received a ready-spun linen warp.Footnote72 The weaver was expected not only to weave the cloth, but also to arrange the spinning of the cotton weft yarn. The model here may have been practice in the neighbouring Rochdale bay trade. Bays were woollen textiles made with long-staple worsted warps and short-staple carded wefts. Baymakers often put out ready-spun worsted warps to their weavers, while supplying them with short-staple sheep’s wool to be spun for the weft.Footnote73 In a region where manufacturing zones for different textiles bordered each other, techniques employed in one could easily spillover to another.

Spinning weft required less labour than spinning warp, especially the loosely spun weft characteristic of many Lancashire cotton-linen fabrics. Consequently, it was feasible for a weaver to have the cotton weft spun locally, often mainly by his own family. This new variant on the putting-out system was not suitable for making fabrics with coloured or bleached yarns, such as checks or stripes, where the yarn had to return to the manufacturer for dyeing and bleaching before being put out to be woven.Footnote74 But it became widespread in the manufacture of Blackburn greys, which were neither loom-patterned nor used bleached cotton yarn.

Oswaldtwistle was at the northern extremity of Lancashire’s core cotton district, where it overlapped with the worsted spinning zone (). In this liminal area, wages for worsted spinning offered an attractive alternative to spinning cotton, just as they did to button-making at roughly the same period at Wilmslow, 30 miles to the south. At Clitheroe, nine miles north of Oswaldtwistle, the poor had spun flax in the 1690s, but by 1751 they were spinning worsted. At Whalley, five miles to the north, it was also worsted that was spun in 1751.Footnote75 Immediately adjacent to Oswaldtwistle, in the townships of Rishton and Great Harwood, which separated it from Whalley, cotton spinning and worsted spinning intermingled. A 1767 census of these townships’ Catholic minority, which listed women’s occupations, identified nine spinners of worsted, but also three spinners of cotton. Among the worsted spinners, three had husbands who wove cotton check.Footnote76 At Oswaldtwistle it was weavers of Blackburn greys who confronted the challenge posed by local demand for worsted spinners during the 1750s and 1760s. These weavers now bore the responsibility for having their employer’s raw cotton spun into weft. Hargreaves was probably one of them, given his close association with the Blackburn manufacturer, Robert ‘Parsley’ Peel, who lived less than three miles away and in the mid-1760s established at Oswaldtwistle the first of the Peel family’s cotton printing works.Footnote77

As initially conceived, Hargreaves’ spinning jenny spun only weft, it was domestic in scale and it was optimised for use by children; indeed, it was physically difficult for many adults to use. It did away with the need for skilled fingers — what John Holker termed ‘the spinner’s hand’ — to control the drafting of the fibre. A wooden clasp held the rovings as they were drawn out and spun. Other multi-spindle, hand-cranked spinning machines invented in the 1760s (mainly for spinning linen yarn) were designed to make work for very young pauper children. They did so by eliminating the physical effort of turning a spinning wheel, but still required each thread to be drafted by the fingers of a single child.Footnote78 The jenny, by contrast, facilitated the employment of younger, less dexterous workers by eliminating the need for hard-won manual drafting skills altogether. In the face of competition for spinning labour in the locality, it was a perfectly contrived response by a male head of household to the new, weaver-centred system for organising weft spinning. It allowed weavers to rely more exclusively on family labour to process the raw cotton their employers obliged them to convert into yarn.Footnote79 At the same time it provided them with direct control over yarn quality, an important consideration in weaving. Hargreaves’ concern with retaining yarn preparation within the household is confirmed by a previous invention credited to him earlier in the 1760s, a method of carding with multiple cards so that ‘one woman could perform twice as much work, and with greater ease than she could do before in the common way’.Footnote80

Ironically, in view of Robert Allen’s focus on the cost of factors of production to explain the emergence of the jenny, under this system spinning labour was not directly priced. A notional payment for the spinning undertaken by a family’s women and children was simply bundled into the weaver’s contract for each piece of fabric. Allen is right to argue that James Hargreaves’ invention of the spinning jenny was an innovation associated with pressure in the market for spinning labour. Yet that pressure was not, as Allen would have us believe, an epiphenomenon of a distinctively British high wage economy extending to women’s and children’s earnings across the country. English spinning costs were indeed sometimes higher than those elsewhere in Europe. The huge quantities of relatively coarse grades of linen and worsted yarn imported into England during the eighteenth century reflected lower spinning costs for those yarns in Ireland and the eastern Baltic. Yet little cotton yarn was imported, even though pressure on spinning piece rates in Lancashire in the 1760s coincided with increasing use of imported yarns elsewhere, particularly in the Norwich worsted industry, where imports of Irish worsted yarn facilitated cuts in local spinning wages.Footnote81 Spinning labour markets, like the industries they served, were often markedly local or regional in character. The shortage of spinners in mid-eighteenth-century Lancashire emerged in a specific locality at a specific moment. It affected spinners of a range of fibres, among whom those who spun cotton were not the most numerous. The genesis of Hargreaves’ invention cannot be understood simply by considering the relative costs of capital and labour at a national level.Footnote82 The key inducements to innovation were the costs of labour and raw materials as they impacted the local production system for a relatively new fabric with distinctive material characteristics — the 50:50 ratio, unbleached, cotton-linen Blackburn greys, which supplied the London textile printing industry.

The very different characteristics of the eighteenth-century cotton industry in France meant an invention along the lines of the spinning jenny was most unlikely. Few of the inducements to invent or to take up the jenny observed in Lancashire were present in Normandy. There were three main reasons.

The Normandy cotton industry grew exceptionally quickly in the 1730s and 1740s, but the product mix was different from Lancashire. There was no large-scale production of either heavy fustians, or of plain, unbleached fabrics for printing, at least before the 1760s. The dominant product (siamoise) was a loom-patterned fabric incorporating dyed and bleached yarns.Footnote83

The spinning labour market in Normandy was not organised under the putting-out system. There was no particular incentive to combine spinning and weaving as part of an integrated family textile economy. Cotton spinning was divided into fewer specialised tasks than in Lancashire, used cheaper equipment and did not face local competition for spinning labour from other fibres. Indeed, in Normandy it was the spinning of non-cotton fibres, such as woollen yarn for cloth manufacturers at Darnétal and Elbeuf, that was threatened by cotton.Footnote84

In Normandy the practice of spinning was plagued with quality problems. Levant cotton, which could be spun only to low counts, was widely used. Carding was poor, spinning wheels were unsuitable for finer yarns, and there was no pre-spinning of coarse rovings. The failure to employ a standard measuring reel resulted in high transaction costs for matching yarn quality to the finished product and ill-defined incentives to improve quality.

For France the consequence was a predominance of low count, coarse, inconsistent, ill-spun cotton yarns. When the jenny was introduced there in the 1770s, these quality issues were to prove major obstacles to its use. It was John Holker’s son who brought the jenny to France in 1771. He and his father went on to construct jennies to spin fine cotton for their cotton velvet manufactories at Rouen in Normandy and at Sens, south-east of Paris. Powerful patrons then pressured the Holkers to supply jennies to other centres of cotton spinning. They included Villefranche sur Sâone, north of Lyon, where a manufactory of printed cottons was established after the ending of their prohibition in 1759. The younger Holker complied, though reluctantly. ‘The machine may not be suitable for this manufacture, any more than for all the others of the same kind which only print on common coarse fabrics, similar to those from Switzerland in quality. It is only advantageous for the spinning of fine cottons’.Footnote85 The printing fabrics made at Villefranche and in nearby centres in Burgundy during the 1760s and 1770s were all-cotton garas (gurrahs), copies of Indian and Swiss cottons used in the cheap prints smuggled into France before 1759. Their yarn was spun from Levant cotton and was coarse.

Louis-Casimir Brown, inspector of manufactures for Picardy, agreed with Holker. In 1779 he reported on the use of a jenny to spin very fine yarn for cotton velvets at Amiens.

It is necessary to choose the longest, softest and most consistent [cotton] wools, known by the names of Maraignan [Maranhão, Brazil] and Cayenne, because the finest qualities come from those regions. At a pinch, the cotton which comes to us from St Domingue and Martinique could also be used, but an inferior yarn would be the result. The cotton which comes to us from the Levant, known by the name of Smyrna cotton, should be avoided. Its fibres are too short, too dry, too brittle. Yarn made from it would be too coarse and would not repay the costs of the work. There is no benefit from spinning with this machine except when the yarn is very fine.Footnote86

To work without breakages, the jenny required careful preparation of the raw cotton, including carding with well-made cards appropriate for the count of yarn to be spun, followed by pre-spinning into rovings. Despite savings in the final spinning, these additional preparatory stages rendered the economics of the jenny unviable for spinning low count, low value yarns from the inferior Levant cotton so widely employed in France, even in Normandy. In Lancashire, where higher quality, New World cottons predominated, these preparatory processes were already well established. Without them, it is hard to imagine the jenny could have been developed, let alone widely adopted. In France, where low-quality Levant raw cotton set the standard, preparatory processes were correspondingly cruder. Coarse yarn spun from Levant raw cotton, whether by hand or on the jenny, was unlikely to repay the cost or effort of the English preparatory sequence — washing with soap, slow carding with expensive, time-consuming cards, pre-spinning into rovings. At Rouen in 1773, twenty years after the English techniques were first publicised, it was still ‘rare to see the manufacturers making use of the English cards’, because they were more expensive and did ‘half as much work as is done with the ordinary cards, a disadvantage which, according to them, cannot be outweighed by the perfect regularity of the carding’.Footnote87 Any cost advantage the jenny offered in the final spinning of cheaper, short-staple cottons was nullified by the expense of following the English mode of preparation.

According to John Holker, the maximum yarn count produced on a hand spinning wheel with Levant cotton was Ne 16. The majority of counts spun from Levant cotton must have been a good deal coarser, too coarse for the jenny. A 1793 report on the record of spinning machines in France concluded that jennies ‘have not enjoyed success nor been profitable to the manufacturers, except for yarns between no. 15 up to no. 24’.Footnote88 It was estimated in 1781 that there were more than 1,200 jennies in use in France, but most were probably larger machines with thirty spindles or more, spinning New World cottons in workshops to high counts for speciality fabrics, such as cotton velvets.Footnote89 When employed in the manufacture of coarser fabrics, they failed. At Noyon in Picardy in the 1780s, forty jennies were distributed to spin yarn for the manufacture of coarse cotton-linen fabrics. By 1789, only six remained in use. ‘Their shortcomings have become clear and now only the great wheel is used’.Footnote90

Domestic Machines?

The jenny was conceived in the mid-1760s as a machine to be used in James Hargreaves’ own household by his wife and his children, a number of whom were of an appropriate age during the mid-1760s. Hargreaves’ first jenny had only eight spindles. The slightly larger version he patented in 1770, after his move to Nottingham, still had only sixteen. Despite initial hostility among Hargreaves’ neighbours in the vicinity of Oswaldtwistle, fearful of cuts in piece rates due to the increased output per worker on the new machines, these small jennies soon came to be widely used in the locality.Footnote91 They were ‘altogether simple and easy to build’, essentially multiplications of the spindle spinning wheel set in a wooden frame.Footnote92 Spindle wheels for spinning cotton bought by the Latham family in west Lancashire between 1739 and 1754 cost 2s each, less than half the cost of flyer wheels the family bought for spinning flax.Footnote93 John Holker reported in 1773 that a jenny ‘with 25 to 30 spindles at a time and as many threads … does not cost more than twenty ordinary spinning wheels’. Two jennies acquired in 1774 and 1777 by the overseers of Worsley and Swinton in Lancashire for paupers to spin cotton in their homes cost 34s and 36s each. If, as Holker suggested, the cost per spindle was slightly less than an ordinary spinning wheel, then these jennies are unlikely to have had more than twenty-four spindles.Footnote94 These were small machines constructed mainly from wood, smaller than a loom and not much more expensive. The sixteen-spindle jenny at the Science Museum in London, reconstructed from Hargreaves patent drawings of 1770, is only 3 feet 9 inches long by 4 feet 5 inches wide (1.15 metres by 1.35 metres) ().

Fig. 13. A sixteen-spindle spinning jenny, reconstructed from James Hargreaves’ 1770 patent drawings, Science Museum, London, 1970-0174.

Science Museum/Science and Society Picture Library.

Nevertheless, within a very few years of the jenny’s invention, jennies were being acquired not just by working weavers, but also by their employers — cotton manufacturers — who began to bring them together in workshops. Robert Peel may have done so as early as 1768. In 1769, manufacturers at Bolton, Turton and Bury owned jennies, and one of them had five jennies on his premises. At about the same time James Hargreaves himself installed several sixteen spindle jennies in a workshop at Nottingham, producing cotton yarn for sale to stocking knitters.Footnote95

From shortly after its invention, therefore, the jenny came to be used in two different ways. The first simply reproduced Hargreaves’ original practice, disseminating the way the jenny was used in his family to other putting-out households weaving plain fabrics. As we have seen, from the 1740s, manufacturers of Blackburn greys and plain fustians had adopted the practice of putting out ready-spun linen warps to households in combination with raw cotton to be spun into the corresponding weft, paying a single, unified wage to the head of household for all the different stages of work required to produce the woven fabric.

The second was more radical, transcending the context in which the jenny was first devised to apply it in ways Hargreaves may not have originally intended. It dispersed the jenny’s productivity gains across all the Lancashire cotton industry’s varied products, recasting it as the region’s standard spinning tool for cotton weft. Used in this manner, yarn spun on the jenny was not woven within the household where it was spun. Instead it was passed or sold on to be processed elsewhere, often after it had been bleached, dyed, or twisted for use in fabrics such as dimities, checks or cotton velvets. Jennies used in this second manner might be either domestic, located in households, or non-domestic, concentrated in specialist workshops. Irrespective of whether the setting was domestic or a workshop, the spinner who worked the jenny was paid a wage, although whether that wage included the cost of carding and roving must have depended on the setting.Footnote96

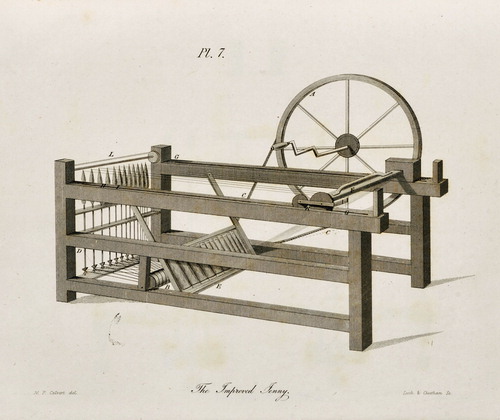

A shift towards workshops was encouraged by the progressive refinement of the jenny and associated equipment during the 1770s. Refinements to the jenny included replacing the horizontal drive wheel with a vertical wheel, making it easier for adults to use, and replacing direct cord drives to each spindle with a wooden or tin roller. These and associated changes made the ‘improved jenny’ more complex to construct and more expensive, increasingly beyond the resources of a working family unless a putting-out master provided the machine along with the raw cotton.Footnote97 The improvements made it possible to extend the jenny laterally. The familiar illustrations of the improved jenny, published early in the nineteenth century and often reproduced since, depict machines with only twelve or sixteen spindles ().Footnote98 They are misleading. Already, by the early 1780s, improved jennies with eighty spindles or more were coming into use, which could be operated by a single, though often male, worker.Footnote99 These were not domestic machines. Even fifty or sixty spindle jennies were 13 feet (4 metres) or more in width. The house at Stanhill, Oswaldtwistle where James Hargreaves is said to have invented the jenny was only about 18 feet by 19 feet (5.5 metres by 5.8 metres). It was typical of workers’ housing in the mid-Pennines and Rossendale.Footnote100 The larger improved jennies would not have fitted, even if they had been affordable.

Fig. 14. ‘The Improved Jenny’, as illustrated in Richard Guest, A Compendious History of the Cotton Manufacture (Manchester, 1823), pl. 7.

Reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library.

The invention, spread and refinement of the jenny was accompanied by a progressive reconstitution of the division of labour in spinning and associated preparatory processes. The labour requirement for final spinning was reduced, but techniques for carding and coarse spinning of rovings on the hand wheel remained the same, at least initially. As a result, labour was re-allocated towards the preparatory processes, which required even more care than before, because ill-prepared rovings resulted in yarn breakages on the jenny. At the same time, there was a move towards the employment of children to work the early jennies, which, as we have seen, were optimised for their use.Footnote101

Evidence compiled as jennies were introduced in France and Spain allows us to gauge the changes. In hand spinning in Lancashire, according to John Holker in 1755, carding and roving had accounted for 33% of the cost of making the yarn and the final spinning for 67%. The equivalent costs for a thirty-spindle jenny in a French workshop in 1779 were 43% for carding and roving and 57% for the final spinning. This change can also be observed in the numbers employed. In 1786, at the Spanish Royal Spinning Company’s workshop in Barcelona, the ratio of preparatory workers to jenny spinners was 5:4, very different from the 1:3 ratio of preparatory workers to hand spinners reported by John Holker for pre-jenny Lancashire. The Barcelona workshop used 36 spindle jennies, but traditional, non-mechanised carding and roving.Footnote102 The shift in the balance of labour costs towards preparatory processes led to further concentration of jennies in workshops. In a challenge and response sequence of capital-intensive labour-saving innovations, a series of hand-powered preparatory machines were introduced alongside arrays of spinning jennies — willows for cleaning and opening the raw cotton, carding machines and large roving jennies, also known as slubbing jennies.Footnote103

Lancashire cotton workers were well aware of the difference between smaller domestic jennies and larger workshop jennies. Many prospered during the 1770s by using domestic jennies. ‘What a prodigious difference have our machines made in the gains of the females in a family’, insisted a Lancashire magistrate in 1780.

Formerly, the chief support of a poor family arose from the loom. A wife could get comparatively but little, on her single spindle. But, for some years, a good spinner has been able to get as much, or more than a weaver … the gains of an industrious family have been, upon the average, much greater than they were before these inventions.Footnote104

Those who benefited resented growing competition from larger, more productive and more expensive hand-driven machines in the workshops of well-capitalised manufacturers. They considered the viability of the small, domestic jenny to be threatened by its larger, workshop-based rivals. When in the autumn of 1779 they rioted against machinery during a downturn in the industry associated with the American War of Independence, they destroyed spinning and preparatory machines of various kinds, both water-driven and hand-driven, but jennies with twenty-four spindles or less were spared.Footnote105

What remains uncertain, however, is how much additional income, if any, Lancashire spinners secured as a result of the introduction of the domestic spinning jenny. Robert Allen suggests spinners’ earnings did not increase at all, because their labour supply curve was backward-bending. He argues they responded to the jenny’s superior productivity by working less, remaining satisfied with their accustomed level of income and consumption.Footnote106 This is implausible. The available contemporary estimates for the differential between spinners’ earnings at the wheel and at the jenny all derive from the debate for and against mechanisation that followed the 1779 riots. Both sides in the debate agreed that domestic jenny spinners earned more, although estimates of the premium they initially secured varied wildly, from 20% to 400%, while the relationship between payments for fibre preparation and for final spinning was never specified.Footnote107 The best-documented eighteenth-century Lancashire hand-spinning family of the pre-jenny era, the Lathams of Scarisbrick, certainly displayed no reluctance to take on additional spinning when opportunity arose, expanding their consumption accordingly, dramatically so for clothing.Footnote108

The number of domestic jennies actually used in the Lancashire cotton industry also remains uncertain. No one ever walked the lanes and moorland paths of Lancashire and Cheshire counting spinning jennies in scattered cottages. The available evidence is contradictory. Two estimates were made in the 1780s (). The most frequently repeated is the estimate by the Scottish merchant and statistician, Patrick Colquhoun, in 1788. Colquhoun, who was new to Lancashire, insisted his estimate was ‘the result of a very accurate enquiry made at Manchester on the 6 March 1788’. He listed 20,070 hand jennies in use, 15,000 used to spin weft for weaving with cotton warps spun on Arkwright water frames (which were rapidly replacing linen warps) and 5,070 ‘spinning independently’ for other unstated purposes. Colquhoun does not specify ownership or location, but a good proportion of the former would have consisted of smaller jennies installed in weaving households. Colquhoun’s figures were probably exaggerated. He assumed the average number of spindles per jenny was eighty, but it is inconceivable that the 15,000 jennies used to spin weft for use with machine-spun warps had anywhere close to eighty spindles if sited in cottages like Hargreaves’. At the time, Colquhoun was a paid lobbyist on behalf of one interest group among the Lancashire cotton manufacturers — the calico- and muslin-makers — in its dispute with the East India Company. So he had an interest in exaggerating the size of the industry and the numbers of workers threatened by imports of calicoes from India.

Table 3. Estimates of the Number of Spinning Jennies in Use in the Lancashire Cotton Industry, 1784 and 1788

The second estimate was made four years earlier, in 1784, by Richard Arkwright, the inventor of the water frame. He, too, had an axe to grind — he was promoting the idea of a tax on machinery as an alternative to the government’s new excise taxes on cotton fabrics — but he also had a much more intimate, long-standing acquaintance with Lancashire cotton manufacturing than Colquhoun. His planned machinery tax was criticised as self-serving by other cotton manufacturers, because it threatened to lock-in the advantage in cotton warp spinning Arkwright already enjoyed from his (disputed) patent rights. However, it is hard to see any benefit to Arkwright from manipulating the numbers of domestic jennies, because he acknowledged that their owners would not be able to afford anything more than a small, one-off licence fee. He estimated there were 5,333 domestic jennies, ‘the property of the lower class who possess not more than one jenny each, and who only spin the cotton they receive for the purpose of weaving it in their own families’. In addition, he estimated there were 2,667 jennies ‘which are the property of persons possessing more than one, or which are worked for hire’. His estimate for the average number of spindles per jenny was more realistic than Colquhoun’s, up to thirty for the domestic jennies and seventy-four for the others, which suggests the latter were mostly workshop jennies.

Colquhoun and Arkwright were offering informed guesses. Their estimates can both be correct only if there was an increase of two and a half times in the number of jennies over the four intervening years, 1784 to 1788. This seems unlikely, at a time when spinning mules were taking off.Footnote109 Arkwright displayed more awareness of the types of jennies in use and probably came nearer the truth than Colquhoun.Footnote110 If so, then already, in 1784, more than half of all jenny spindles were concentrated in workshops, although the majority of jennies remained domestic. The workers who rioted in 1779 in defence of small, domestic jennies were right to fear the growing competition of big machines in workshops and factories.

By the second half of the 1780s, the practice of putting out raw cotton and spun warps to be processed together in a weaver’s household was in retreat. We can trace its decline in summary convictions and committals for embezzlement (). Embezzlement of materials by outworkers was a specific offence distinct from theft of materials by workers in workshops, factories or warehouses.Footnote111 The records of convictions and committals allow us to observe the changing relative numbers of cases where a warp and raw cotton were put out jointly to a weaver for processing, as opposed to cases where a warp was put out to a weaver in combination with ready-spun weft. The former would usually involve the use of a domestic jenny to spin the raw cotton, the latter would not. In the 1770s (when the number of cases was relatively small) and the early 1780s, over 80% of these cases saw raw cotton supplied to be spun on a domestic jenny. By the start of the nineteenth century less than 5% did, and after 1804 none.Footnote112 In less than two decades, the domestic spinning jenny had largely disappeared from the Lancashire cotton industry. Some coarse cotton weft yarn went on being spun commercially on large jennies housed in workshops, but increasingly it was the jenny’s progeny, the factory-based spinning mule, with its finer and more regular yarn, that predominated.

Conclusion

The rise and fall of the domestic spinning jenny in the Lancashire cotton industry spanned a mere forty years. Nevertheless, the jenny remains one of the key technical innovations of the Industrial Revolution, original and Janus-faced. In conception and operation, it was embedded in the material and technical divisions of labour distinctive to domestic cotton spinning in Lancashire during the previous century. Yet, once in use, it was rapidly re-engineered as a larger, more costly machine installed in non-domestic, proto-factories, while the discontinuous mode of operation it borrowed from hand spinning was reproduced in the spinning mule of 1779 by its inventor, Samuel Crompton, who had worked at a jenny in his youth. The mule would dominate Lancashire cotton spinning for the next century and a half.