ABSTRACT

A fireplace represents one of the most fundamental and time-transgressive gathering points for humans. However, when situated in pits that are organized in lines running sometimes hundreds of metres, fire pits represent a significant challenge in terms of interpretation, and may evidence a particular perception of space. This paper argues that in a Bronze Age context, pits associated with fire remains marked out directionality and axiality in the landscape as part of ceremonial events of a temporary nature. Adopting a landscape approach and going beyond regional and chronological borders, the authors argue that in northwestern Europe such events took place in relation to unbounded barrow landscapes in open spaces and could often be linked to the orchestration of funerary events. In some regions, the depositional activities evident in relation to these aligned pits have added significance. Furthermore, the authors argue that the aligning of fire pits is incompatible with divided or parcelled landscapes, thus challenging interpretations of pitted lines as territorial and field boundaries.

Introduction

Linear rows of pits filled with fire-cracked stones, usually referred to as ‘cooking pit lines’ or ‘fire pit alignments’, are increasingly uncovered by development-led excavations across northern Europe. The archaeological evidence indicates that they represent significant places and events in the life of late prehistoric people, as some of these pitted lines can have lengths of more than 400 m (e.g. Margrethehåb, Denmark – Christensen [Citation1986]), and others appear in linear arrangements of more than a thousand fire pits (e.g. Rønninge Søgård, Denmark – Thrane [Citation1974]; Thörn [Citation2005]). So far, discussions have focused particularly on the precise functions of the pits.

Some are considered as evidence for collective cooking and feasting activities (Lerche Citation1969; Henriksen Citation2005, 92, 97; see also Fendin Citation2005, 408); others are just thought of as pits in which hearth remains were deposited later for other reasons (Martens Citation2005, 51). Some scholars suggest that the fire-cracking of stones is more likely to result from steam production, as a result of spectacular ceremonial performances or due to their use in sweat lodges (Gustafson Citation2005, 125; Martens Citation2005, 52; see also Ó Drisceoil [Citation1988]).

Furthermore, significant progress has been made in interpreting their situation in the landscape with their frequent proximity to running water and wetland areas now noticed by several researchers (e.g. Heidelk-Schacht [Citation1989]; Henriksen [Citation2005, 85, 89]; Kristensen [Citation2008, 38]). In this sense, they are comparable to the burnt mounds or ‘fulachtaí fiadh’ from Britain and Ireland that are known from the Middle to Late Bronze Age (Hawkes Citation2014; Brown et al. Citation2016).

When it comes to their linear organization, however, very few explanations have been given and curiously, this characteristic is rarely addressed. Some explanations of the fire pit lines draw parallels with linear territorial markers, such as field and land boundaries. We, however, want to explore this puzzling question and ask why prehistoric people created lines of pits of such lengths (cf. Seeberg and Olsen [Citation1971]; Thrane [Citation1974]; Heidelk-Schacht [Citation1989]; Lundin [Citation1992]; Sjösvärd and Sjöström [Citation1993]; Thörn [Citation1996]), and how are we to understand the emergence of similar pitted lines in different parts of Europe at different times?

This paper aims to show that there is much to be gained by taking a landscape approach, and we argue that fire pit lines represent a different form of spatial organization from the solid boundaries and fences that are more typical for the Iron Age sedentary landscapes of Northern Europe. Represent repetitive depositional actions that mark out connections and directionality, and potentially signify the assembly of people in these predominantly unbounded landscapes. In this sense, the fire pit lines are comparable to other early forms of linear landscape markers such as stone rows, avenues and post alignments.

About lines

At the outset, there are two aspects that need to be emphasized. The first is that we are dealing with large numbers of pits in which fires were lit or pits in which the remnants of fires were placed. The second is that these pits were positioned in lines. There may be practical reasons for lighting a fire in a pit, however, a new pit for every new fire was certainly not a necessity, and the spatial organization of such pits we must assume could have taken any form relevant to necessary function. How then should this persistent habit of organizing these pits in lengthy lines be interpreted?

Artificial lines are structures that are deeply cognitively and culturally salient. They signal intentionality (Tversky Citation2016, 240), in that lines contrast with random patterns of nature. This makes them obvious as commonly recognized, semiotic structures. Humans can recognize repetitive spatial structures relatively easily (e.g. Dennett [Citation1996, 138–9]; Hutchins [Citation1995, 155]) and have an automatic preference for phenomena that follow a certain pattern (Sommerhoff Citation1990, 100–2; see also Lynch [Citation1960]). Periodic repetitions or regular forms such as lines, circles or repeated symmetrical intervals will thus have a high conceptual salience. Furthermore, spatial lines are strong Gestalten for the eye (Tversky Citation2016, 240) and play a crucial role in the ways in which humans orient themselves in space, and how well we remember things (Julian et al. Citation2016; Spier Citation2016).

Humans instinctively tend to use and perceive lines in two fundamentally different ways, depending on the context and direction of motion: as boundaries and as axes. Whereas the first of these ways of experiencing space has been studied and described in depth in archaeological research of Bronze Age and Iron Age landscapes (e.g. Field [Citation2008]; Fink [Citation1992]; Johnston [Citation2013]), the second has received very little focus. In many situations in our everyday lives, however, lines are used in ways that are different from that of boundaries and enclosures (Sheets-Johnstone [Citation2011]). In many hospital corridors, for example, coloured lines are used as directional markers to find a given section. On the New York City Subway, lines indicate the connections between different places in the urban landscape. In semantics, diagrammatology and schematizing, lines are used to indicate a given line of reasoning, or to indicate the ways in which one object leads to others (see Ingold [Citation2007, Citation2015]). In many cases, then, lines are used more as ‘pointers’, ‘connectors’ or ‘lines of orientation’. These ways of using and perceiving lines can essentially be compared with Deleuze and Guattari’s concept of a line within a ‘smooth’, affective and nomadic space as opposed to a ‘striped’, sedentary space (Deleuze and Guattari [Citation1980] 2005, 617–52). In the former, the line appears as a vector and a direction rather than a metric spatial device (ibid., 623). As a consequence, the cooking pits would represent points situated on a line rather than a line drawn between two points (ibid., 622, 626). Also, if the intention is to repeat things that had been done before (which must be the case for some of the sites under discussion here), a line provides a means of ordering: a line can be easily lengthened. With a line there is a clear ‘before’ and an ‘after’ without substantially changing the overall outlook, nature or order. It is these concepts of lines that are by far the least investigated avenues of enquiry that can help, perhaps, to make sense of many of the fire pit alignments that cannot be understood as boundaries.

Fire pit lines: a brief survey

‘Fire pits’ are frequently discovered on archaeological excavations in Northern Europe. They are usually understood to contain large amounts of fire-cracked stones, and sometimes charcoal and artefacts. In the Bronze Age they often appear at settlement sites, sometimes within houses, where they are typically ascribed to everyday household activities (cf. Henriksen [Citation2005, 97]). They also occur in large clusters (Bradley Citation2007, 243–5; Kruse and Matthes Citation2012) as well as at Iron Age burial sites (Henriksen Citation2005, 95; Lorange Citation2015) as well as off-site at some distance away from settlement and burial sites (Holst and Rasmussen Citation2013, 109).

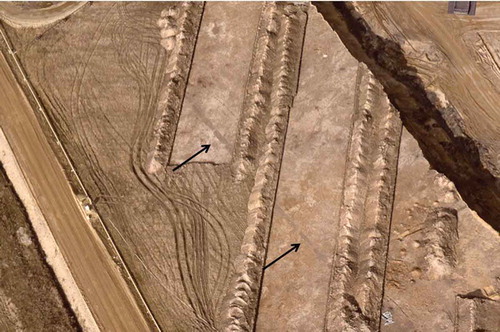

The phenomenon of placing such features in linear arrangements is less frequently attested, however, and it is this phenomenon that is central to our commentary ().

Figure 1. Fire pit line from Roskilde, Denmark, looking southwest. Photograph reproduced with the permission of Roskilde Museum.

There has been a tendency to see aligned fire pits as a phenomenon tied to the Nordic realm in the Late Bronze Age and early Pre-Roman Iron Age (Martens Citation2005, 43; Risbøl Citation2005). But a range of related forms of pitted lines are known from several north-western European countries beyond these regions, and some that pre-date the Late Bronze Age and others that post-date the Pre-Roman Iron Age ().

Figure 2. Distribution map of (fire) pit alignments known from northern Europe, including Britain, the Netherlands, Germany, Denmark and Sweden. The features vary in date, from the Late Neolithic to the Early Iron Age. Based on Heidelk-Schacht (Citation1989), Lütjens (Citation1999) and Kristensen (Citation2008) with additions.

In Denmark, southern Sweden (Scania/Halland) and north-west Poland, pitted lines occur frequently as both single and multiple ‘fire pit lines’ (). The fire pits are represented by oval pit features with ample amounts of fire-cracked stones and compact layers of charcoal, suggesting that fire was indeed, in many cases, lit in the pits themselves (Kristensen Citation2008). Remains from ceramics, bones or artefacts are found only rarely. A relatively large proportion of the fire pit lines have been 14C-dated (for the most recent overview, see Kristensen [Citation2008]). The dates tend to concentrate in the Late Bronze Age and the very Early Pre-Roman Iron Age (Henriksen Citation1999, Citation2005); however, linear arrangements of fire pits are also known from later times (Larsson Citation1982).

Figure 3. Fire pit line at Brokbakken III, Denmark (Kristensen Citation2008, Figure 13).

In northern Germany fire pit lines are discovered relatively frequently (Thörn Citation1996; Lütjens Citation1999; Schmidt and Forler Citation2004). Most are single pit lines containing fire-cracked stones. Although in some cases it is clear that material was burnt in the pit (e.g. Freudenberg [Citation2012]), this is rarely the case. For an extensive line like one from Seddin with 162 pits, fires were lit at ground level alongside and the remnants were placed in the pit afterwards (; see also May and Hauptmann [Citation2012, 86]). Cases of multiple pit lines are known but rare, as are examples of accompanying rows of posts and palisades (cf. Heske, Lüth, and Posselt [Citation2012, 321]). The three-pit line from Hüsby is older than most in Scandinavia (Freudenberg Citation2012), but generally the German examples also date to the Late Bronze Age/Early Iron Age (Heske, Lüth, and Posselt Citation2012, 320–1). In Saxony the pits tend to be shaped as elongated, almost rectangular, and do not contain fired stones (Stäuble Citation2002; Randsborg Citation2008, 247); they are therefore not classified as ‘fire pit alignments’. Hence, these latter forms of pit lines remain secondary to our study.

Figure 4. Pit line at Seddin, Germany (Brunke et al. Citation2016, Figure 12). Scale in metres.

In the Netherlands, only one single pit line has been discovered so far () (Louwen and Fontijn Citation2019). It consists of rounded pits with broken, probably fire-cracked, stones and very tiny amounts of charcoal; these are flanked by some pits containing pottery sherds. This site, Apeldoorn, dates to the earlier Bronze Age (seventeenth–sixteenth century BC).

Figure 5. Fire pit line from Apeldoorn, the Netherlands (Louwen and Fontijn Citation2019).

In Britain, late Neolithic pit alignments are known, but most examples are Late Bronze Age/Iron Age in date (cf. Bradley [Citation2007, 244–5]; Rylatt and Bevan [Citation2007]). They are typically constructed as single lines of soil-filled pits. Their fills usually do not contain fire-cracked stones or charcoal and are therefore not classified as ‘fire pit alignments’; as a result these too are secondary to the study presented here.

Overall, linear fire pit arrangements seem to be concentrated in the Nordic regions, but they are also known from surrounding areas and there are large variations in terms of their contents and organization. Their dating also tends to differ from region to region, with early examples known from areas beyond the Nordic realm.

A landscape-oriented approach

A landscape-oriented approach to fire pit lines was introduced almost 30 years ago by Heidelk-Schacht (Citation1989) and formed a stepping-stone for later research (e.g. Thörn [Citation1996]; Kristensen [Citation2008]). He and several other authors have noticed the association between fire pit alignments and particular landscape characteristics such as ridges and watercourses. However, as fire pit lines have been increasingly found on archaeological excavations, they are now harder to make sense of in this ‘typological’ way. Every time a pit line meets one of Heidelk-Schacht’s criteria, there will also be exceptions. Moreover, given the paucity of understanding regarding other types of linear landscape feature, the linear arrangement of pits and fire pits has been interpreted as an activity comparable to that of creating territorial markers and land divisions (Rylatt and Bevan Citation2007, 221; Kristensen Citation2008, 39; Randsborg Citation2008, 247, 249).

Our survey shows instead that the linear arrangement of fire pits or pits with stones cannot be completely reduced to a single culturally or a chronologically well-defined phenomenon. With regard to the landscape setting, current interpretations remain rather generic and unspecific. In our survey, we propose alternative ways of looking at these features, in relation to how past populations organized and perceived the landscape. In developing such an approach, we argue that behind the admittedly broad variety of functions and dates, there is a central organizing principle: in all cases and in all countries mentioned, we are dealing with depositional activity placed in a line. It is this process of alignment in the landscape in particular that in our view requires more attention. Why would something that seems so ‘mundane’ as a fire pit be dug in often lengthy lines, particularly when located outside settlements?

A landscape perspective: fire pit lines as axes for special activities

Directionality

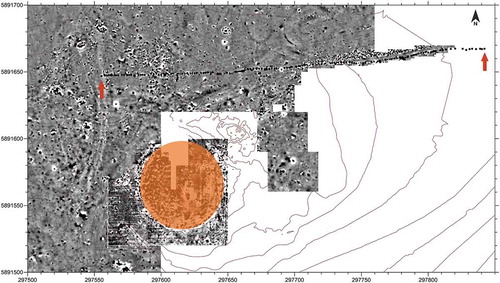

First of all, the fire pit alignments show a concern with laying out a particular axis or direction in the landscape. At Brokbakken III in Denmark (), several strings of fire pit lines run parallel to each other, yet connect to the same point of departure. Comparable multi-stringed examples are known from Løvel I-II and Rønninge Søgaard (Denmark), and Ringarekullen and Stretered (Sweden). This confirms that a specific direction was an essential feature common to every pit line.

In both Denmark (Løvschal Citation2013, 236ff) and Sweden (Björk Citation1998; Rudebeck and Ödman Citation2000, 215; Björhem Citation2001; Nordqvist Citation2001), a connection between fire pit lines and potential Bronze Age roads has been observed. Furthermore, the emphasis on specific directionality may have created a temporal, yet possibly spectacular, effect, especially if a row of fires were ignited at one event. Even in cases where remains were buried in pits, these may have been visible as lines of individual depressions on closer approach.Footnote1 Fire pit lines may thus have marked directionality in very specific ways.

In an open landscape with barrows

It is therefore an interesting observation that as far as we know the fire pit lines do not occur in environments where there are other kinds of artificially constructed linear boundaries. In those cases where we have information on the environment, they seem to have been intentionally created in open areas like heathland and sandy plateaus where there are often barrows and other burial sites in the vicinity. These landscapes are generally characterized as inhabited by relatively small communities involved in farming, herding and the grazing of livestock (Fleming Citation1971; Cunliffe Citation2010; Doorenbosch Citation2013; Holst and Rasmussen Citation2013). In such landscapes, movement would have been crucial on several scales, from local and regional patterns of herding and transhumance to the long-distance exchange of knowledge and goods.

From Denmark, there are examples of fire pit lines running between or along pairs of barrows (e.g. Kildehuse II – Runge [Citation2012, Figure 13]; Kolsbæk, GIM 4043), or in the same direction as a cluster of barrows (Frammerslev – Kristensen [Citation2002, Citation2008]). In several cases, fire pit lines have been constructed in close proximity to contemporary or near-contemporary linear barrow cemeteries, such as in Nørreådalen and Ravnstrup Mølle in Denmark (Frost Citation2008; Løvschal Citation2011). At Frammerslev, the linear courses of the barrows, the fire pit line and the post alignment appear to follow the same direction (Kristensen Citation2008; –). At Fosie in Scania, a line of 13 fire pits from c.1100–840 BC appear to align roughly with a burial mound of ‘Grötehög’ (Thörn Citation2005, 71). In Germany and the Netherlands, there are examples where they are physically linked to one particular barrow e.g. Hüsby, Germany (Freudenberg Citation2012, 627) and Apeldoorn, Netherlands (Louwen and Fontijn Citation2019), or where they provide an axis running to the entrance of a special barrow, e.g. the monumental Late Bronze Age elite barrow of Seddin in Germany (May and Haptmann Citation2012). Similar observations of fire pit alignments ‘connecting’ or ‘pointing’ towards neighbouring burial mounds have been discovered at a vast number of sites, including Foulum and Kolsbæk both in Denmark, at Malmö in Sweden and at Schwissel in Germany.

We therefore hypothesize that fire pit lines represent events that created or confirmed direction and axiality in otherwise unbounded landscapes. The evidence we have so far for the different regions of northern Europe suggests that they were often related to activities in the funerary sphere and provided links to either one specific or groups of visible burial mounds. It is also worth noting that many fire pit lines were constructed by relatively mobile communities and herding groups (cf. the discussion of nomadic space by Deleuze and Guattari Citation2005 [1980], 617ff). The existence of less sedentary life forms has been discussed widely in connection with the linear monuments and cemeteries for Britain (Fleming Citation1971; Woodward and Woodward Citation1996) and recently also in a southern Scandinavian context (Holst and Rasmussen Citation2013). In these landscapes, the seasonal movement of livestock as well as people was key to the socio-economic cohesion. Therefore, it is also likely that the marking of directions, trajectories and axes in the landscape played a radically different role than in areas that were completely parcelled out and enclosed.

With repeated fires and depositions

Thirdly, pit lines show a strong concern with depositional activity as a means of creating axes in the landscape. In all regions, they are the end result of a widely shared practice of what might be called an ‘elemental’ ritual. Particular places in the landscape were temporarily, but repeatedly, marked with fire, smoke or steam. These landscape lines had centripetal rather than centrifugal affordances: the lines acted as focal lines or axes for repeated events, rather than physical obstructions. It was considered relevant to include the burnt remains in the earth – so the act of deposition was crucial. This is true both for sites where just remnants of fires were deposited (cf. May [Citation2017]) and those which show evidence of fires being set in the pits, as pit-digging, after all, is not essential for making fires.

Particularly in Denmark (Kristensen Citation2008), but also in northern Germany (cf. overview by Heske, Lüth, and Posselt [Citation2012, 318–22]), there are many examples of burnt soils and layers of charcoal, indicating that fires had been burning in the fire pits (Kristensen’s type 1 pits). However, less attention has been paid to the large numbers of pits that contain fire-cracked stones without indication that these pits were places where fires were lit (ibid., type 2). This is the case for the extensive Seddin pit line (Heisig Citation2017; May 2017, 49) and for all pits at Apeldoorn. The fire pit line of Frammerslev contains both types with many pits that are not properly speaking ‘fire pits’ (Kristensen Citation2008; –). Kristensen (Citation2008, 16–17) tends to resolve this by seeing type 2 pits as ‘intended’ fire pits, but this is not an entirely satisfactory explanation. The German and Dutch examples mentioned may serve to indicate instead that the burial of stones in pits was a practice in its own right. The observation that some of the buried stones seem to be fire-cracked implies that the buried material could have been used for similar activities to that evident in the ‘true’ fire pits. A related observation has been put forward by Martens (Citation2005, 50–1), who argues that the lack of red burnt clay on the edges of the pits at Glumslöv Bakker, Sweden, is the result of the lighting of fire or cooking taking place in other features (see also Kristensen [Citation2008, 16–17]).

Regardless of whether the burning did or did not take place in the pit, one thing that apparently mattered to people was that material related to this activity was located in a particular place in the landscape, buried in a specific spatial relation to where comparable activities had taken place before in an aligned arrangement. This suggests that the pits placed in these alignments must reflect related depositional acts of a particular and selective kind.

In some cases, there is evidence that artefacts were deposited. This is particularly true for the German and the Dutch cases. At Hüsby, Germany, fragments of grinding stone/slabs were placed in one of the pits (Freudenberg Citation2012, 627), whereas in Apeldoorn the fragment of a rare amber spacer was placed in the largest known pit of the line (Louwen and Fontijn Citation2019). At Hünenburg, Germany, two Late Bronze Age metalwork hoards were deposited in a marshy area. At the transition from this wetland to the dry land where people lived, there were multiple series of parallel pit lines. Although they are different from the single lines discussed here, we seem to be dealing with a similar kind of connecting element, in this case depositions demarcating landscape and settlement (Heske, Lüth, and Posselt Citation2012). From Gwithian, Cornwall, a pit alignment is known with four pits, each containing the burnt remains of a human adult and animal bones (Nowakowski Citation2009, 121). In Denmark, it is relatively rare for other materials to be deposited in the fire pits. Examples include ceramic sherds, burnt animal remains, grinding stones (Henriksen Citation2005, 95–6) and a bronze tweezer (Thrane Citation1974). There thus seems to be a difference between Scandinavian and other cases: in Scandinavia pit alignments were foci of burning performance but elsewhere they tended to be locations for the deposition of remnants of such events. The fact that other artefacts were sometimes included as well suggests that the depositional activities in their own right may have mattered most.

The digging of pits and the lighting of fires or the deposition of related material in them were actions that were repeated several times, resulting in lengthy pit lines. In many cases it is clear that many people must have been participating in pit-digging and fire lighting activities: the fire pit lines represent the remains of communal events, involving the coming together of people for special activities. When carrying out such acts, it was apparently also important to relate one’s contribution to those of predecessors. Importantly, these links with previous actions were visually expressed by placing pits in a linear arrangement aligned with existing cultural markers and topographical points of orientation in the landscape.

Fire pit lines as a time-transgressive concept of landscape

Fourth, and finally, the time-transgressive nature of this pit-line phenomenon seems difficult to understand. However, if the idea is correct that there is a relationship between such lines and the creation of barrows and monuments, then it makes sense that these pit lines might be created at different points in time because barrow building was equally varied, with different monuments in a landscape built at different times. The date for the Apeldoorn pit line is early if compared Danish examples (seventeenth/sixteenth century BC cal), but corresponds well with the dates of the barrows to which the pit row is linked (Citation2019). It is also perhaps no surprise that the majority of dates for fire pit lines in Scandinavia succeed an unprecedented phase of barrow building (fiteenth–thirteenth century BC cal; Holst Citation2013).

It has been suggested that the fire pit lines disappear from northern Europe during the Iron Age or are turned into very different arrangements, such as fire pit clusters and ‘specialised fire pit concentrations’ (e.g. Hvass [Citation1985]; Henriksen [Citation1999]). Examples are known from settlement sites on Funen where they are used as fence-like features (Henriksen Citation2005, 93ff). One is Fraugde Radby in Denmark, where the pits make a rectilinear enclosure of a farmstead, comparable to later forms of fencing (Henriksen Citation2005, Figure 19). Another Danish example is Kellebyvej Syd, where a line of fire pits aligns with a presumably contemporary house construction (Henriksen Citation2005, Figure 18). If this is consistently true, then this confirms our general hypothesis that the linear fire pit arrangements predominantly predate later forms of artificially enclosed and bounded landscapes in northern Europe, and represent a different form of spatial organization. So far observations suggest a mutually exclusive relationship existed between these ‘lines in the landscape’ and later forms of linear boundary demarcations. Although fire pit lines sometimes occur within Celtic fields in Denmark (here dating to c.800 BC–AD 200), none to date have been shown to be part of an alignment that corresponds with these field systems. In regions where pitted lines are endemic, there also seems to be a general change in their use: for example in Late Bronze Age/Later Iron Age Saxony and Britain pit lines do appear to be compatible with coinciding forms of landscape division ().

Discussion: lines as directionality and orientation

So why arrange pits in lines? Earlier in this paper, we introduced the notion of two fundamentally different categories for lines in the landscape: lines as boundaries and lines as connections and directions. This fundamental difference in organization can be identified in the archaeological record. The first function is represented by fire pit alignments that seem to mirror other forms of landscape compartment such as enclosing fences and field systems. They divide the landscape into large blocks of land and occur alongside other forms of tenurial boundaries (cf. lines in a ‘sedentary space’). These lines are used as a way of solving a communication and tenure issues, for negotiating and allocating land, but are not perhaps a means of ritually assembling people. This landscape organization is typical for the Saxonian and British Iron Age pit alignments (e.g. Stäuble [Citation2002]; Rylatt and Bevan [Citation2007]; Knight [Citation2007, 210]; Randsborg [Citation2008]). In these areas and in southern Scandinavia, they tend to succeed earlier axial forms of landscape lines.

Lines acting as connections and directions are represented by the fire pit alignments that apparently have no explicit delimiting function in the landscape (cf. lines in a ‘smooth space’). These do act as focal gathering points and are lines that often ‘point towards’ or connect with watercourses or older barrows. This landscape organization is typical for southern Scandinavia and the North Sea coast and features in Neolithic Britain, and these types of alignment tend to precede later forms of linear, artificial boundaries.

To identify all fire pit lines as ‘boundaries’ or ‘territorial demarcations’ would thus be to oversimplify the issue. Fire pit lines were not boundaries that operated like fences or earthen or stone walls (cf. Løvschal Citation2014, 73). Nor are they comparable to ditches that might present a physical obstruction. Instead we are dealing with features that testify to events that were affective and engaging and may have involved group/community activity and assembly in an open, unbounded environment marked by burial monuments. They offered an axial structure for acts of repetition engagement with particular places. By using these linear structures to link with, connect and ‘point towards’ significant places in the landscape (e.g. barrows, ridges and watercourses), a visual relationship between past and present landscapes may well have been emphasized by such events.

This way of conceptually linking pit-digging with linear structures seems older than instances of aligned pits that operated as boundary-like features. Ideas of direction and connection may have been most relevant to the linear orientation of these features (e.g. Løvschal [Citation2014, 730]) and in this sense, they seem to mirror the position of stone rows (Bender, Hamilton, and Tilley Citation2007, 90–100; Owoc Citation2005), fire ditches, aligned funerary structures and post alignments. The latter are types of monuments and activities that have also been associated with gatherings and assemblies and have been connected as well with watercourses and barrows. In particular, the placement near and along rivers might be argued as a strong indication that such features and activities were connected to movement and directionality relevant to travel on foot or by water. This aspect can also be seen reflected in the repeated depositional practices taking place in particular zones of rivers and valleys (Frost Citation2013). Such concerns are typical for the Scandinavian landscape and relevant to northern Germany, and Neolithic and Early Bronze Age pit alignments in Britain (Pollard et al. Citation1996; Wigley Citation2007, 120).

Thus in summary, fire pit lines seem to represent lines that point towards particular places or areas of the landscape and are also linear features that show a concern with existing monuments and other features ‘linking’ or ‘connecting’ with them. Moreover, they functioned as axes in the landscape, guiding repeated activity and communal ritual engagement. This was different from linear boundaries that represented a division of space into enclosed units or areas; instead we suggest they were centripetal, a product of gatherings and features that guided movement and connected landscape markers and features.

Why a particular direction was chosen is not always clear. At Apeldoorn, the line is physically linked to one of three barrows. This happens to be a special example, as it is the only one built upon a much older (late Neolithic) monument (Louwen and Fontijn Citation2019). The Seddin pit line also led to a special barrow, the so-called King’s grave which is the largest and most lavish barrow in the area (May and Haptmann Citation2012). More frequently the directionality, as at Brokbakken III, remains enigmatic (), but the repeated endorsement of a single particular direction shows that people clung to these axial and linear arrangements and used new acts to confirm them. In numerous cases (cf. Hünenburg, Germany – Heske, Lüth, and Posselt [Citation2012]), fire pit lines were aligned towards or constructed along a watercourse or wetland area, emphasizing flow and movement rather than operating as any kind of solid impediment.

Concluding remarks

In this paper we have taken a step away from searching for essentialist explanations for these landscape features. Instead we have re-framed them as a reflection of a particular spatial logic or perception of the landscape based on the communal act of creating and assembling along lines in the landscape, in places partly detached from the domestic sphere.

By organizing fire pits in lines towards or along a watercourse or wetland area, people were underlying their association with an equivocal character as a transcendental limit ‘towards’ rather than a solid impediment ‘across’. This logic seems comparable to the thinking and processes argued as affective stimuli for other Neolithic/Early Bronze Age linear features, such as stone rows and linear barrow cemeteries (Fleming Citation1971) or post alignments.

We have suggested as a point for future debate that the fire pit lines brought people together, not only to dig them, and light fires and deposit burnt material, but for the purpose of creating visual spectacles and participating in activities aimed at marking time and linking existing monuments and landscape features perhaps to reinforce lines of movement in the landscape. The scarcity of systematic dating for these fire pits and their contents means that the chronological development of each feature still remains open to question. Were multiple pits created as part of the same event, or did people repeatedly come back to these locations to add on or more new pits? In addition, the surroundings of pitted lines seem relevant – simply following them with archaeological trenches seems unhelpful for improving our understanding of their role. Indeed exploring to what degree these apparently invisible structures were something that structured subsequent long-term patterns of human activity and movementFootnote2 may well lead to a fuller understanding of these prehistoric phenomena.

Acknowledgements

A big thanks to Joanna Brück, Lise Frost, Sarah Semple and Andy Wigley for comments on an earlier draft of this paper and two anonymous reviewers. Thanks to Ole Kastholm, Arjan Louwen, Jens May, Robert Reiss and Harald Stäuble for providing figures and information.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Mette Løvschal

Mette Løvschal is assistant professor in the department of Archaeology and Heritage Studies, Aarhus University. She works at the interface between landscape archaeology and social anthropology, and has published on Bronze Age land bounding, spatial perception and Iron Age sacrificial traditions.

David Fontijn

David Fontijn is professor in the archaeology of early Europe at the Faculty of Archaeology, University of Leiden. His current research is on the enigmatic ‘economies of destruction’ in prehistoric Europe, the deliberate sacrifice of crucial valuables and materials in the landscape.

Notes

1. In regards to Late Iron Age pit alignments in England, it is argued that such depressions may have been visible too, standing in contrast to the surrounding environment (Rylatt and Bevan Citation2007, 220).

2. As suggested by sites such as Fosie, where the rows of fire pits coincided with phases of Iron Age and Viking Age activity (Thörn Citation2005, 71–2).

References

- Bender, B., S. Hamilton, and C. Tilley. 2007. Stone Worlds: Narrative and Reflexivity in Landscape Archaeology. Walnut Creek, CA: Left Coast Press.

- Björhem, N. 2001. “En (för)historisk väg.” In Kommunikation i tid och rum (Report Series 82), edited by L. Larsson, 61–72. Lund: University of Lund, Institute of Archaeology.

- Björk, T. 1998. “Härdar på Rad. Om Spåren efter en kultplats från Bronsåldern.” Fornvännen 93 (2): 73–79.

- Bradley, R. 2007. The Prehistory of Britain and Ireland. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, A. G., S. R. Davis, J. Hatton, C. O’Brien, F. Reilly, K. Taylor, K. E. Dennehy, et al. 2016. “The Environmental Context and Function of Burnt-Mounds: New Studies of Irish Fulachtaí Fiadh.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 82 (2016): 259–290. doi:10.1017/ppr.2016.7.

- Brunke, H., E. Bukowiecki, E. Cancik-Kirschbaum, R. Eichmann, M. van Ess, A. Gass, M. Gussone, et al. 2016. “Thinking Big. Research in Monumental Constructions in Antiquity.” eTopoi. Journal for Ancient Studies 6: 250–305.

- Christensen, T. 1986. “En Lang Historie.” ROMU Årsskrift for Roskilde Museum, (1986): 27–32.

- Cunliffe, B. 2010. Iron Age Communities in Britain: An Account of England, Scotland and Wales from the Seventh Century BC until the Roman Conquest. 4th ed. London: Routledge.

- Deleuze, G., and F. Guattari. [1980] 2005. Tusind Plateauer: Kapitalisme og Skizofreni. Translated by Niels Lyngsø. Copenhagen: Det Kongelige Danske Kunstakademis Billedkunstskoler.

- Dennett, D. 1996. Kinds of Minds: Towards an Understanding of Consciousness. New York: Basic Books.

- Doorenbosch, M. 2013. “A History of Open Space. Barrow Landscapes and the Significance of Heaths—The Case of the Echoput Barrows.” In Beyond Barrows—Current Research on the Structuration and Perception of the Prehistoric Landscape through Monuments, edited by D. Fontijn, A. J. Louwen, S. van der Vaart, and K. Wentink, 197–223. Leiden: Sidestone.

- Fendin, T. 2005. “De rituella fälten på Glumslövs backar.” In Bronsåldersbygd 2300-500 f.Kr. Skånske spor – arkeologi längs Västkustbanan, edited by P. Lagerås and B. Strömberg, 367–419. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- Field, D. 2008. “Development of an Agricultural Countryside.” In Prehistoric Britain (Blackwell Studies in Global Archaeology 11), edited by J. Pollard, 202–224. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Fink, H. 1992. “Om Grænsers Måde at Være Grænser På.” In Grænser, edited by F. Stjernfelt and A. Troelsen, 9–31. Aarhus: Center for Kulturforskning, Aarhus Universitetsforlag.

- Fleming, A. 1971. “Territorial Patterns in Bronze Age Wessex.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 37 (1): 138–166. doi:10.1017/S0079497X00012792.

- Freudenberg, M. 2012. “Grab und kultanlage der älteren bronzezeit von hüsby, kreis Schleswig-Flensburg.” In Gräberlandschaften der Bronzezeit (Bodenaltertümer Westfalens 51), edited by D. Bérenger, J. Bourgeois, M. Talon, and S. Wirth, 619–639. Darmstadt: Von Zabern.

- Frost, L. 2008. “Depotfundene i Himmerlands yngre bronzealder i et landskabsarkæologisk perspektiv.” PhD diss., Aarhus: Aarhus University, Department of Prehistoric Archaeology.

- Frost, L. 2013. River finds – Bronze Age depositions from the River Gudenå. Germania 91, 39–87.

- Gustafson, L. 2005. “Kokegroper i utmark.” In De Gåtefulle Kokegroper; Kokegropseminaret 31. November 2001 (Varia 58), edited by L. Gustafson, T. Heibreen, and J. Martens, 207–222. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Fornminneseksjonen, University of Oslo.

- Hawkes, A. 2014. “The Beginnings and Evolution of the Fulacht Fia Tradition in Early Prehistoric Ireland.” Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Vol 114C, 89–139. DOI: 10.3318/PRIAC.2014.114.02

- Heidelk-Schacht, S. 1989. “Jungbronzezeitliche und früheisenzeitliche Kultfeuerplätze im Norden der DDR.” In Religion und kult in ur-und frühgeschichtliche zeit. 13. Tagung der fachgruppe ur- und Frühgeschichte, edited by F. Schlette, 225–240. Berlin: Akademie-Verlag.

- Heisig, S. 2017. “Mehr als heisse Seine? Digitale dreidimensionale Rekonstruktion von Teilen der Steingrubenreihe in Seddin, Lkr. Prignitz.” Archaeologie in Brandenburg 2015: 50–52.

- Henriksen, M. B. 1999. “Bål i lange baner – om brugen af kogegruber i yngre bronzealder og Ældre jernalder.” Fynske Minder 1999: 93–128.

- Henriksen, M. B. 2005. “Danske kogegruber og kogegrubefelter fra yngre bronzealder og Ældre jernalder.” In De Gåtefulle Kokegroper; Kokegropseminaret 31. November 2001 (Varia 58), edited by L. Gustafson, T. Heibreen, and J. Martens, 77–102. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Fornminneseksjonen, University of Oslo.

- Heske, I., P. Lüth, and M. Posselt. 2012. “Deponierungen, Gargruben und ein Verfüllter Wasserlauf. Zur Infrastruktur der Hüneburg-Aussensiedlung bei Watenstedt Lkr Helmstedt. Vorbericht Über die Grabung 2011.” Praehistorische Zeitschrift 87 (2): 308–337. doi:10.1515/pz-2012-0018.

- Holst, M. K. 2013. “South Scandinavian Early Bronze Age Barrows - a Survey.” In Skelhøj and the Bronze Age Barrows of Southern Scandinavia. Vol. I. The Bronze Age Barrow Tradition and the Excavation of Skelhøj, edited by M. K. Holst and M. Rasmussen, 27–128. Højbjerg: Jutland Archaeological Society.

- Holst, M. K., and M. Rasmussen. 2013. “Herder Communities: Longhouses, Cattle and Landscape Organisation in the Nordic Early and Middle Bronze Age.” In Counterpoint: Essays in Archaeology and Heritage Studies in Honour of Professor Kristian Kristiansen, edited by S. Bergerbrant and S. Sabatini, 99–110. Oxford: BAR International Series.

- Hutchins, E. 1995. Cognition in the Wild. Bradford: MIT Press.

- Hvass, S. 1985. Hodde. Et Vestjysk Landsbysamfund fra Ældre Jernalder (Arkæologiske Studier 7). Copenhagen: Akademisk Forlag.

- Ingold, T. 2007. Lines: A Brief History. London: Routledge.

- Ingold, T. 2015. The Life of Lines. London: Routledge.

- Johnston, R. 2013. “Bronze Age Fields and Land Division.” In Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, edited by H. Fokkens and A. F. Harding, 311–327. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Julian, J. B., J. Ryan, R. H. Hamilton, and R. A. Epstein. 2016. “The Occipital Place Area Is Causally Involved in Representing Environmental Boundaries during Navigation.” Current Biology 26: 1104–1109. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.066.

- Knight, D. 2007. “From Open to Enclosed: Iron Age Landscapes of the Trent Valley.” In The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond, edited by C. Haselgrove and T. Moore, 190–218. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Kruse, P., and L. Matthes 2012. “Brinde/ Egelund: Materiel kultur og social organisation i bronzealderen.” In Bebyggelsen i yngre bronzealders lokale kulturlandskab (Yngre bronzealders kulturlandskab vol. 3), edited by S. Boddum, M. Mikkelsen and N. Terkildsen, 25-40. Viborg, Holstebro: Viborg Museum, Holstebro Museum.

- Kristensen, I. K. 2002. “Frammerslev.” Arkæologiske udgravninger i Danmark 2002, nr. 296. Accessed 12 October 2017. http://slks.dk/publikationer/publikationsarkiv-kulturarvsstyrelsen/singlevisning/artikel/arkaeologiske_udgravninger_i_danmark/

- Kristensen, I. K. 2008. “Kogegruber – i klynger eller på rad og Række.” Kuml 2008: 9–57.

- Larsson, L. 1982. “Gräber und Siedlungsreste der Jüngeren Eisenzeit bei Önsvala im Südwestlichen Schonen, Schweden.” Acta Archaeologica 52: 129–196.

- Lerche, G. 1969. “Kogegruber i Ny Guineas højland.” Kuml 1969: 195–210.

- Lorange, T. 2015. “Det sakrale landskab ved Årre: Landskabets hukommelse gennem 4.000 års gravriter.” In De dødes landskab. Grav og gravskik i Ældre jernalder i Danmark. Beretning fra et colloquium i ribe 19. −20. Marts 2013, edited by P. Foss and N. A. Møller, 21–36. Copenhagen: SAXO-Institute, Copenhagen University.

- Louwen, A. J., and D. R. Fontijn. 2019. Death Revisited. The Excavation of Three Bronze Age Barrows and Surrounding Landscape at Apeldoorn-Wiesselseweg. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Løvschal, M. 2011. “Mellem høj og hjulspor: Landskabsarkæologiske perspektiver på vejene i viborg-området i yngre bronzealder.” In Depotfund i yngre bronzealders lokale kulturlandskab. Seminarrapport fra seminaret “depotfund i yngre bronzealders lokale kulturlandskab”, afholdt i Viborg, 4. Marts 2010 (Yngre bronzealders kulturlandskab vol. 2), edited by S. Boddum, M. Mikkelsen, and N. Terkildsen, 81–96. Viborg, Holstebro: Viborg Museum, Holstebro Museum.

- Løvschal, M. 2013. “Ways of Wandering: In the Late Bronze Age Barrow Landscape of the Himmerland-Area, Denmark.” In Barrows and Beyond: Current Research on the Structuration and Perception of the Prehistoric Landscape through Monuments, edited by D. Fontijn. Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Løvschal, M. 2014. “Emerging Boundaries. Social Embedment of Landscape and Settlement Divisions in Northwestern Europe during the First Millennium BC.” Current Anthropology 55 (6): 725–750. doi:10.1086/678692.

- Lundin, K. 1992. “Kokgropar i Norrbottens Kustland. Ett försök till Tolkning av Kokgroparnas Function.” Arkeologi i Norr 3: 139–174.

- Lütjens, I. 1999. “Langgestreckte Steingruben auf einem jungbronzezeitlichen Siedlungplatz bei Jürgenshagen, Kreis Güstrow.” Offa 56: 21–44.

- Lynch, K. 1960. The Image of the City. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Martens, J. 2005. “Kogegruber i syd og nord – Samme Sag? Består Kogegrubefelter bare af Kogegruber?” In De Gåtefulle Kokegroper; Kokegropseminaret 31. November 2001 (Varia 58), edited by L. Gustafson, T. Heibreen, and J. Martens, 37–56. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Fornminneseksjonen, University of Oslo.

- May, J. 2017. “Das Königsgrab von Seddin. Archaeologie, Denkmalschutz und Tourismus 2012 bis 2015.” Archaeologie in Berlin und Brandenburg 2015: 44–50.

- May, J., and T. Haptmann. 2012. “Das “Köningsgrab” von Seddin und sein engeres umfeld im Spiegel neuer Feldforschungen.” In Gräberlandschaften der bronzezeit (Bodenaltertümer Westfalens 51), edited by D. Bérenger, J. Bourgeois, M. Talon, and S. Wirth, 77–104. Darmstadt: Von Zabern.

- Nordqvist, B. 2001. “En Kultplats vid Stretered.” In Möten med Forntiden: Arkeologiska Fynd År 2000, edited by L. Flodin and A. Modig, 45–47. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- Nowakowski, J. A. 2009. “Living in the Sands: Bronze Age Gwithian, Cornwall, Revisited.” In Land and People: Papers in Memory of John G. Evans, edited by M. J. Allen, N. Sharples, and T. O’Connor, 115–125. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Ó Drisceoil, D. A. 1988. “Burnt Mounds: Cooking or Bathing?” Antiquity 62: 671–680. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00075062.

- Owoc, M. A. 2005. “From the Ground Up: Agency, Practice, and Community in the Southwestern British Bronze Age.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 12 (4): 257–281. doi:10.1007/S10816-005-8449.

- Pollard, J., V. Fryer, P. Murphy, M. Taylor, and P. Wiltshire. 1996. “Iron Age Riverside Pit Alignments at St Ives, Cambridgeshire.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Vol 62, 93–115.

- Randsborg, K. 2008. “Permanent Lines: Registered Territoriality in the Bronze Age.” Acta Archaeologica 79: 246–249. doi:10.1111/aar.2008.79.issue-1.

- Risbøl, O. 2005. “Kokegroper i røyk og damp - et kokegropfelt i gårds- og landskapsperspektiv.” In De Gåtefulle Kokegroper; Kokegropseminaret 31. November 2001 (Varia 58), edited by L. Gustafson, T. Heibreen, and J. Martens, 155–165. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Fornminneseksjonen, University of Oslo.

- Rudebeck, E., and C. Ödman. 2000. Kristineberg: En Gravplats under 4500 År. Malmö: Stadsantikvariska Avdelingen, Kultur Malmö.

- Runge, M. 2012. “Yngre bronzealders bebyggelse indenfor et 350 hektar stort undersøgelsesområde sydøst for odense.” In Bebyggelsen i yngre bronzealders kulturlandskab. Seminarrapport fra seminariet “Bebyggelsen i yngre bronzealders lokale kulturlandskab” afholdt i holstebro, 10. Marts 2011 (Yngre bronzealders kulturlandskab vol. 2), edited by S. Boddum, M. Mikkelsen, and N. Terkildsen, 113–139. Viborg, Holstebro: Viborg Museum, Holstebro Museum.

- Rylatt, J., and B. Bevan. 2007. “Realigning the World. Pit Alignments and Their Landscape Context.” In The Later Iron Age in Britain and Beyond, edited by C. Haselgrove and T. Moore, 219–234. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Schmidt, J. P., and D. Forler. 2004. “Ergebnisse der Archäologischen Untersuchungen in Jarmen, Lkr. Demmin. Die Problematik der Feuerstellenplätze in Norddeutschland und im süDlichen Skandinavien.” Bodendenkmalpflege in Mecklenburg-Vorpommern 51: 7–79.

- Seeberg, P., and A. Olsen. 1971. “Storudvinding Af Trækul.” MIV I: 48–51.

- Sjösvärd, L., and U. Sjöström. 1993. “Härdgropssystem i gottörra – kokgruber? Processionsväg?” In Långhundraleden – en seglats tid och rum. 50 bidrag om den gamla vattenleden från Trälhavet till Uppsala Genom årtusendena, edited by A. Långhundraleden, 132–135. Uppsala: Arbetsgruppen Långhundraleden.

- Sheets-Johnstone, M. 2011. The Imaginative Consciousness of Movement: Linear Quality, Kinaesthesia, Language and Life. In Redrawing Anthropology 115–128.

- Sommerhoff, G. 1990. Life, Brain, and Consciousness: New Perceptions through Targeted Systems Analysis (Advances in Psychology 63). Amsterdam: North-Holland.

- Spier, H. J. 2016. “Spatial Cognition: Finding the Boundary in the Occipital Place Area.” Current Biology: Dispatches 26 (8): 323–325. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2016.02.049.

- Stäuble, H. 2002. “Lineare Gräben Und Grubenreichen in Nordwestsachsen. Eine Übersicht.” Arbeits-Und Forschungsberichte Zur Sächsischen Bodendenkmalpflege 44: 9–49.

- Thörn, R. 1996. “Rituella Eldar. Linjäre, konkava och konvexa spår efter ritualer inom nord och centraleuropeiska brons- och järnålderskulturer.” In Religion från stenålder till medeltid. Artiklar baserade på religionsarkeologiska nätverksgruppens konferens på lövstadbruk den 1-3 December 1995 (Arkeologiska Undersökningar 19), edited by K. Engdahl and A. Kaliff, 135–148. Stockholm: Riksantikvarieämbetet.

- Thörn, R. 2005. “Kokgropsrelationer.” In De Gåtefulle Kokegroper; Kokegropseminaret 31. November 2001 (Varia 58), edited by L. Gustafson, T. Heibreen, and J. Martens, 67–76. Oslo: Kulturhistorisk Museum, Fornminneseksjonen, University of Oslo.

- Thrane, H. 1974. “Hundredvis Af Energikilder Fra Yngre Bronzealder.” Fynske Minder 1974: 96–114.

- Tversky, B. 2016. “Lines: Orderly and Messy.” In Complexity, cognition, urban planning and design: Post-proceedings of the 2nd Delft International Conference, edited by J. Portugali and E. Stolk, 237–250. Switzerland: Springer.

- Wigley, A. 2007. “Pitted Histories: Early First Millennium BC Pit Alignments in the Central Welsh Marches.” In The Earlier Iron Age in Britain and the near Continent, edited by C. Haselgrove and R. Pope, 119–134. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Woodward, A. B., and P. J. Woodward 1996. “The Topography of Some Barrow Cemeteries in Bronze Age Wessex.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society. Vol 62, 275–291.