?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Drawing upon Marxian and regulation theory, this article seeks to identify key dynamics and contradictions of capitalist accumulation in China between 1995 and 2015 and to explain these in their institutional context. To this end, data from national accounts and input-output tables is re-mapped to estimate Marxian categories such as the rates of surplus value and profit. The article demonstrates how the transformation of the wage relation and an increase in the rate of surplus value lie at the core of a predominantly extensive accumulation regime that enabled rapid and uncoordinated growth facilitated by world market integration. In the wake of the global crisis, however, a confluence of contradictions has led to over-accumulation and a decline in profitability, clear symptoms of exhaustion of the accumulation regime that explain the current slowdown under the “New Normal.” The underlying contradictions are rooted in the institutional context of the “Socialist Market Economy,” but especially in the wage relation, which no longer supports sufficient increases in the rate of surplus value or a regular pace of accumulation.

Around the turn of the first decade of this century, the Chinese economy transited from a period of rapid accumulation with an average growth rate of almost 10% a year between 1995 and 2010, to the current period of economic slowdown, with GDP in 2019 approaching its slowest growth in almost 30 years. The slowdown reveals a number of structural problems and crisis symptoms in the Chinese economy, which was characterised as “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated, and unsustainable” by former Premier Wen Jiabao as early as 2007, the year before the global financial crisis (GFC) also affected China (China Daily, March 16, 2007). The domestic problems, identified as over-reliance on investments and insufficient household consumption, have been compounded by fundamental changes in the world market in the wake of the GFC, of which China’s economy has become an integral part.

To the Communist Party of China (CPC), the end of the period of rapid accumulation, officially called the “New Normal,” presents substantial political challenges. The legitimacy of the Party’s authoritarian rule depends, in its own eyes, on its continued ability to deliver economic development and prosperity and to manage the transition to a new development model, while remaining on a path towards the “great rejuvenation of the Chinese nation.” This “rejuvenation” entails achieving a per capita national income comparable to that of the most economically advanced countries by mid-century, which requires China’s economy to continue to grow at a relatively faster pace.

However, attempts to “rebalance” growth have been curtailed by lagging household consumption and global demand, prompting the Party-state to repeatedly return to tried methods of mobilising investment to achieve targeted growth rates. Generally, on its way to finding a new growth model, the Party attempts to suppress any unfolding of contradictions into open class struggles and crisis, which is evident, for example, in an increasingly repressive stance against labour under Xi Jinping.

Against this background, given the potential challenges posed to socio-economic development and CPC rule, the economic slowdown in the Chinese economy after 2010 prompts research and theorisation of the underlying processes.

Research on China’s political economy has produced a wealth of detailed knowledge and important insights about the actors and institutions underlying the rapid changes observed in recent decades. To adequately account for the arguably idiosyncratic features of China’s historic experience and the heterogeneity of local and regional conditions for development, the China studies field has preferred to turn its focus to social phenomena on the micro-level (see Shambaugh 2009). This focus, however, has turned attention away from identifying the defining features of China’s socio-economic order at the macro-level, the driving forces and dynamics of its rapid economic development and transformation and the contradictions that underlie the turn towards a “New Normal.”

Against this background, Fligstein and Zhang (2011) argue that the Chinese case should be analysed through the economic sociology and comparative capitalism literatures. However, as Peck and Zhang (2013) point out, attempts to analyse China through frameworks such as the Varieties of Capitalism approach, have tended to produce ahistorical results by applying ideal-typical concepts developed from Western cases. Recently, however, a growing literature has addressed these shortcomings, with one of the most comprehensive and systematic approaches developed by ten Brink (2019), who analyses the specific institutional configurations of China’s socio-economic order and their integration into a “state-capitalist dispositive” facilitating rapid accumulation.

While we thus have a fuller and historically more accurate picture of China’s socio-economic order from a comparative capitalism perspective, ten Brink (2019, 248) points out that it is “self-evident that more research on the rebalancing of the Chinese economy and destabilising dynamics is required.” This requires an approach different from the predominantly institutionalist comparative frameworks of studying capitalism as these are largely unable to account for the changes and contradictions produced by capitalist accumulation (for detailed critiques, see Coates 2005; Streeck 2011). These evidently play a central role in the rapid processes of social transformation in emerging economies or the eruption of economic crises.

Thus, to understand the process of capitalist transformation in China as a dynamic and contradictory process, this article proposes an approach informed by regulation theory in its Marxian origins, specifically as developed in Aglietta’s (1979) work. Combined with an economic method that is suited to operationalise Marxian categories, by analysing the dynamics and contradictions of accumulation within the institutional context of the so-called Socialist Market Economy, the aim is to explain the foundations of rapid accumulation and to qualify whether it is justified to speak of the post-2010 conjuncture in the Chinese economy as a crisis. The approach thus offers a macro-view of China’s capitalist development that takes into account its specific historic features by drawing on and seeking to be complimentary to the rich institutionalist literature on China’s political economy. To measure accumulation empirically, the method developed by Shaikh and Tonak (1994) to estimate Marxian economic categories from Chinese statistics is used. This approach has recently been applied by Jeong and Jeong (2020) to the South Korean case.

For both methodological and historical reasons, the article focuses on the period from the mid-1990s until 2015. Historically, the Chinese economy becomes comprehensively capitalist only in the 1990s, when state-socialist employment relations (the so-called iron rice bowl) are completely dissolved, commodified wage labour becomes dominant in the economy, and all production becomes commodity production in a unified market and price system (see Bramall 2008). In terms of method, the estimation of Marxian categories relies on data according to the UN System of National Accounts and on input-output tables, which have been published by the National Bureau of Statistics (NBS) only since the 1990s.

For the period of rapid accumulation, it is shown how the transformation of the wage relation has created a predominantly extensive accumulation regime, whose inherent tendency towards an uneven development of the departments of production was partially compensated by China’s integration into the world market. While the increases in the rate of surplus value produced by this transformation provided the foundations for rapid accumulation, its inherent limits became apparent even before the Chinese economy felt the impact of the GFC.

The discussion of the New Normal then highlights how in the relationship of global crisis and domestic contradictions the tendency to over-accumulation has been laid bare and reinforced, leading to a decline in the profit rate. Furthermore, the conditions of the wage relation are analysed to show how they present a clear obstacle for a return to a similarly rapid or only regular pace of accumulation.

Regulation Theory and the Problem of Capitalist Reproduction

The aim of this theoretical discussion is to elucidate the relationship of capitalism as a mode of production and the analysis of concrete historical cases of capitalist transformation. Informed by the regulation approach, it shows how historical cases of capitalist development can be understood in terms of the mediation of the contradictions of capitalist reproduction, by focusing the analysis on the relationship of accumulation and institutions.

Regulation theory starts from the problem of the inherent instability of capitalist accumulation, which can be defined in the following sense. Capitalist accumulation produces transformations of the wage relation that in turn produce changes in the rate of surplus value. These changes in the rate of surplus value simultaneously transform several constraints on the social reproduction of capital and the full realisation of value produced. Firstly, it changes the determination of the profitability of capitalist production measured against the value composition of capital. Secondly, changes in the rate of surplus value change the proportions in which the value product needs to exchange between the departments of production (department I, producing the means of production, and department II, producing consumption goods). Finally, the rate of surplus value determines the proportion of final consumption in the forms of capitalist investment and working-class consumption. Aglietta (1979, 87) describes surplus value as “the pivot of capitalist accumulation,” precisely because the problem of capitalist reproduction is hinged on the historical forms of social transformations producing changes in the rate of surplus value, and how these integrate production and circulation within capitalist reproduction.

Contrary to neo-classical economics, Marxian and regulation theory do not assume the existence of general equilibrium conditions that would lead to a co-ordination of changes to these constraints in a non-contradictory way. Indeed, the decisions of decentralised units of accumulation in competition are divorced from any consideration of the cumulative and transformative effects of their actions on these constraints. Additionally, the conditions of exploitation are subject to the class struggle. Workers’ struggles for higher real wages, shorter working hours and, generally, better conditions of employment meet capital’s pursuit of a higher rate of exploitation. The constraints imposed upon reproduction and the full social validation of past investments thus shift permanently, leading to intermittent disruptions or outright crises in the accumulation process.

Given the problematic nature of capitalist reproduction, regulation theory asks how extended periods of sustained and regular accumulation historically come about by investigating the role of institutions in mediating the contradictory requirements of the accumulation process. As Westra (2019, 141–144) points out, there is some uncertainty as to how specifically these intermediate concepts relate to the properties of capital in general so that in the following, the nature of these relationships is elaborated for the present analysis.

The concept of accumulation regime describes a transformation of the wage relation, wherein, for a certain period, increases in relative surplus value co-ordinate with changes in the patterns of investment and consumption, enabling accumulation to proceed relatively smoothly, usually between structural crises (Lipietz 1988, 23; Jessop 2013). Aglietta (1979, 68–72) logically derives two forms of accumulation regime, the predominantly extensive and intensive.

The extensive accumulation regime describes a transformation based on the quantitative expansion of the wage relation, an expansion of capitalist production relations per se, a process often creating hybrid forms of social reproduction in which the reproduction of wage labour is still supported by non-capitalist social relations, especially in agriculture. Technological innovation plays a subordinate role in this transformation as the production of surplus value is increased by an absolute expansion of hours worked for capital. Due to, on the one hand, the quantitative expansion of capitalist production relations and, on the other, the limited role of worker consumption, extensive accumulation is bound to suffer from regular obstructions and stoppages due to the disconnected nature of the development of the departments of production. As the impulse of accumulation is concentrated in department I, typically over-accumulation will materialise when the extensive expansion of the wage relation meets its limits in a dwindling supply of surplus labour.

An intensive accumulation regime is marked by the complete integration of social reproduction into the commodity-producing capitalist economy and an ongoing revolution in the relations of production through technological innovation, predominantly increasing surplus value by a relative expansion of hours worked for capital. As a pre-condition, working-class consumption is fully integrated into the social reproduction of capital. Institutional forms governing the wage relation and competition are such that they provide some degree of cohesion for the expansion of the two departments of production while ongoing transformations in the relations of production produce increases in relative surplus value through the continuous cheapening of labour power. Accumulation can thus proceed in a relatively regular pace.

The accumulation regime is understood to be an analytical concept that intermediates between the general laws of capitalist accumulation and the analysis of concrete historical processes in the following sense: it is a macro-economic concept measuring social transformation in terms of Marxian categories and relationships. This, however, does not assume a simple determination of the transformations measured by the most general laws defining capitalism as a mode of production, but involves the over-determination of this process by historic ensembles of institutions produced by class and other political struggles.

These institutional forms provide rules, norms, coercion and incentives, regulating production relations, labour markets, and consumption norms, setting standards for the allocation and validation of capital, competition and so on, facilitating the emergence and reproduction of certain patterns of accumulation and distribution in an accumulation regime. The regulation approach has come to typically discern five institutional forms: the wage relation, forms of competition, forms of money and credit, forms of state, and the world market (Boyer 1990, 37–42). This article follows Aglietta (1979, 79) in that the wage relation takes priority in an analysis of capitalist development as its transformation most immediately concerns the production and distribution of surplus value and thus the general relationships and contradictions that distinguish capitalism as a mode of production. Also useful is Jessop (2013, 11–13) in indicating the relevance of other institutional forms that should be considered based on their role in temporarily mediating and sharpening the contradictions in a given accumulation regime, which includes their role in creating specific crisis tendencies. The mediation of contradictions may also be analysed as a displacement of these contradictions in space or time, what Harvey (2001) calls spatial and temporal fixes, for example in the form of global trade or debt.

The focus on the problem of the co-ordination of the departments of production and worker consumption as a circuit of capitalist reproduction in Aglietta and following work in the regulation approach has drawn criticism of their corresponding treatment of capitalist crises, for example, in Brenner and Glick (1991, 78), who allege that an “underconsumptionist theory provides the basis for … their institutional-historical theory of capitalist development in general,” by which they mean that the approach privileges the problem of realisation at the expense of the problem of profitability. In my view, this critique is based on a too abridged reading that ignores a main concern of Aglietta, namely, that historical analysis requires an integrated treatment of the problem of production and distribution. As such, social transformations causing changes in the rate of surplus value are the pivot on which hinge interdependent changes in the relations of production and distribution that temporarily stabilise accumulation but ultimately lead to a crisis of over-accumulation. This is discussed by Aglietta (1979, 353–356) as a combined articulation of a transgression of the constraints for realisation of the value in the relationship of the departments of production (i.e. aided by credit) and a decline in the profit rate.

In the approach used here, the concepts provided by the regulation approach primarily serve to structure an analysis of the relationship of accumulation and institutions in a historical period of social transformation. Based on the problematique of capitalist reproduction identified by regulation theory, the analysis will observe the patterns in the accumulation regime that emerged in the institutional context of the Socialist Market Economy, for example, how the institutions governing the wage relation facilitated a rise in the rate of surplus value, as well as the distributional consequences caused by these processes. This includes tendencies and contradictions within the accumulation regime, that potentially serve to undermine it. While this article presents a single case-study, the conceptual framework may still help to better understand Chinese capitalism relative to other cases.

Method: Measuring Marxian Categories

The analysis of the accumulation regime requires the estimation of economic data in terms of Marxian categories. To this end, based on the method of Shaikh and Tonak (1994), data from national income and production accounts (NIPA) and input-output tables to estimate these for the Chinese economy are remapped. As Chinese statistics lack the detailed data on occupation and working hours available, for example, in South Korea, the estimation method employed here lacks some of the refinement and detail demonstrated by Jeong and Jeong (2020). Instead, the analysis here profits from aligning with the adaptation of Shaikh and Tonak’s method by Maniatis (2005) for estimating Marxian categories in the Greek economy.

The estimation procedure firstly requires creation of a coherent data set from Chinese economic statistics and secondly differentiation between production and non-production activities in the data (for details see the Methodological Appendix below).

Regarding the latter, in line with the assumptions of neoclassical economics, NIPA define all non-consumption activity as production activity. Contrary to these assumptions, both classical and Marxian economics share a more restrictive definition of production and a broader definition of consumption, including activities such as circulation and social reproduction. Measuring Marxian categories thus requires the preparation of national accounts data to differentiate between production and non-production sectors as well as between productive labour and unproductive labour in the production sector for estimates to be representative of labour value.

Based on these procedures, the data are remapped to Marxian categories as follows.

Marxian Value Added (VA)

VA is defined as the value of all labour that creates use values, that is, it produces commodities and renders services for productive and final consumption, net of depreciation. On the production side, VA is the value product of the production sector. This requires accounting not only for the net product of the production sector as recorded in national accounts, but also for intermediate consumption of the non-production sectors, not appearing in national accounts, and for value appropriated for services rendered by the non-production sector, recorded in national accounts as a share of the product of those sectors. VA is then estimated from national accounts as the sum of value added net depreciation in the production (VAp) and trade (VAtt) sector, intermediate inputs to the trade sector from the production sector (Mtt), and royalty payments, recorded as intermediate inputs from the production and trade sectors to the financial sector (royalties), RYp and RYtt.

VA = VAp + VAtt+ Mtt+ RYp + RYtt

Details on the estimation of each variable can be found in the Appendix.

Value and Surplus Value

On the income side, VA in a purely capitalist economy is defined as the sum of the value of labour power (V) equal to the wages of productive workers in the production sector, and surplus value (S), the value of surplus labour appropriated by capital. In a real economy, V and S will also include wage-like income resp. profit-like income of the self-employed and small business owners, yielding modified variable capital (V*) and surplus value (S*).

VA = V* + S*

Finally, with estimates of VA and V*, S* can be estimated as

S* = VA – V*

V is defined as the share of productive labour within the production sector. To estimate the share of V in the total wage bill, given as total compensation of employees in national income accounts, wages paid in the production sector need to be differentiated from wages paid in the non-production sector, and wages paid to productive labour in the production sector from wages paid to unproductive labour within the production sector, with details of the procedure in the Appendix.

Surplus value can now be calculated as S* = VA – V* and the rate of surplus value (rate of exploitation) as

e’ = S*/V*

Stock of Capital, Mass and Rates of Profit

The estimate of the stock of capital (K) is taken from Holz and Sun (2018), with the data available online at their website (see article).

The rate of profit is measured as its general rate p’ and its net rate r’. Whereas the general rate delineates the upper boundary of the profitability determined by the cost of capital, the net rate of profit measures actual average profitability by considering the costs of circulation and reproduction, expressed in the cost of non-production labour, the royalties sector, trade, and taxes (T). T includes business tax, corporate income tax and tariffs from the China Statistical Yearbook (National Bureau of Statistics of China various years).

The mass of profit is the numerator in the equation above, namely the mass of surplus value S* minus the total cost of reproduction (U), which are equal to .

The Period of Rapid AccumulationAn Extensive Transformation Wage Relation

Anticipating the following analysis, the transformation of the wage relation in China can be characterised as predominantly extensive in the sense that it is driven not by a qualitative transformation of existing capitalist relations of production in a fully commodified economy, but rather by a quantitative expansion of capitalist production relations based on retrenchment and commodification of labour in the state sector, internal mass migration and partial commodification of migrant labour, which, combined with an expansion of the average working day, substantially increase hours of surplus labour worked for capital, producing a rise in the rate of surplus value. This transformation is embedded in an institutional ensemble that facilitates exploitation by undermining workers’ ability to organise and claim the rights formally granted to them by law.

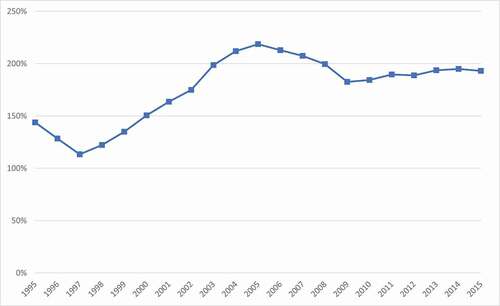

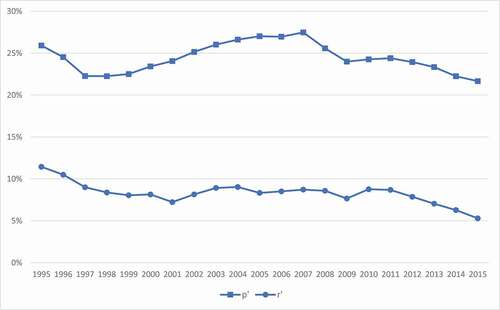

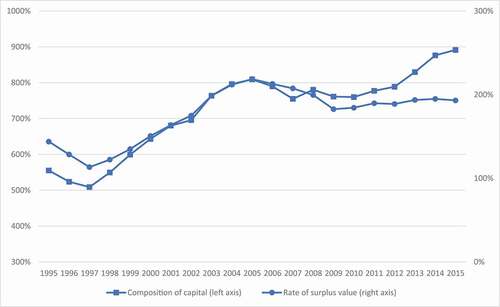

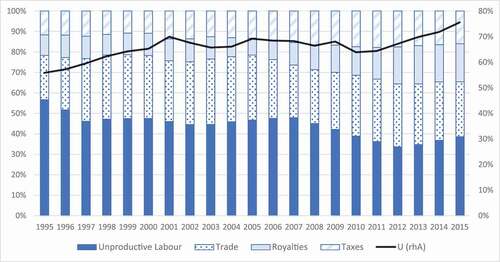

As a result, the rate of surplus value has increased from a low of 113% in 1997 to almost double, reaching 219% in 2005 (see ). The development in the rate of surplus value shows that the extensive accumulation process has exhibited first signs of exhaustion starting as early as 2006, before China was impacted by the fallout of the GFC. Modest increases after 2008 are unable to return the rate of surplus value to its 2005 peak.

In the state sector, the process of commodification of labour began in the 1980s but unfolded fully in the late 1990s after the CPC had violently reasserted its rule in the political crisis of the late 1980s, which created the pretext for severing its relationship with the urban working class and generally redefining class relations in the following years. In the second half of the 1990s, reforms dissolved the socialist labour relations system and expelled surplus labour from the state sector. Knight and Song (2005, 117–128) estimate the total number of jobs cut at up to 60 million, or about 30% of the total urban labour force, with widespread unemployment leading to a depression of workers’ earnings after their re-employment outside the state sector.

The so-called floating population (liudong renkou) of rural migrants seeking employment as wage laborers in the urban centres more than tripled from about 69 million to 244 million between 1995 and 2014.Footnote1 Under the hukou system, about one-third of the urban population hold an agricultural household registration, which restricts their access to social services and education in cities. Workers with a non-local hukou receive lower wages for equal work, work longer hours, and have limited access to public services and social insurance (Song 2014).

Related to lower wages, the social reproduction of migrant workers’ labour power relies in part on familial linkages to the rural economy. The hukou system has thus created a distinct and large segment of the working class whose reproduction is not fully commodified and integrated into capitalist reproduction. This makes them subject to systematic over-exploitation, which, on the one hand, limits their role in capitalist consumption, and, on the other, reduces wage-driven pressures for industrial upgrading of productivity (Chan 2009; Li and Qi 2014; Westra 2018).

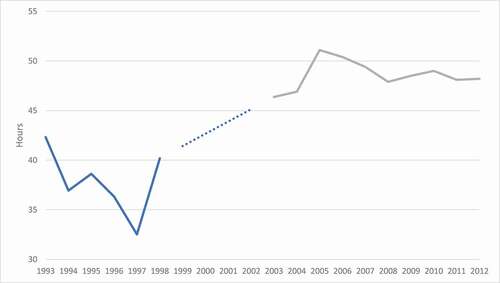

In addition to a large-scale transfer of labour from non-capitalist into capitalist production relations, an increase in the production of surplus value was also achieved by an extension of the average working day. Unfortunately, official statistics on hours worked and hourly wages are fragmented and incomplete. However, a comparison of the fragmented official figures that are available for manufacturing employment shows a clear trend towards prolongation of the working day (see ). Additionally, survey data that differentiate between formal and informal employment show that migrant and informal workers work hours far in excess of the legal limit (see ).

Table 1. Working Time according to China Urban Labour Force Survey (CULS) (hours/week)

It is reasonable to assume that the extensive transformation of the wage relation has had a repressive effect on wages growth. This is masked to a certain extent by official statistics reporting high real-wage increases. For example, NBS figures on real wages of employees in urban non-private enterprises show an average increase of some 10% annually between 1995 and 2015 (NBS via CEIC Data). However, a real-wage index is not available for other ownership types where most workers are employed. More importantly, to this day, no comprehensive statistics on hourly wages are published by the NBS. A significant part of annual wage increases might thus be explained by an increase in hours worked.

Labour laws – the Labour Law of 1995 and the Labour Contract Law of 2008 – nominally grant substantial rights and protections to workers, including the right to a written contract, a work week not exceeding 44 hours, a requirement for employers to contribute to social security payments, as well as provisions for unionisation, collective bargaining and collective contracts. Within the context of China’s authoritarian labour relations system that forbids autonomous class organisations, growth coalitions between local states and capital, a system of individualised mediation of labour disputes, as well as the divisions and stratification created by China’s system of permanent internal migration undermine class formation and enforcement of these laws (Friedman and Lee 2010). The limited enforcement of legal standards combined with the expansion of the wage labour pool has facilitated a predominance of informal employment, which Zhou (2013, 361) estimates makes up 60.4% of urban employment in 2009 and Huang (2017, 3) estimates makes up 75% in 2015.

The accumulation process can thus be described as predominantly extensive because it relies on an absolute expansion of total hours worked for capital, based on labour transfers and an expansion of the working day. The institutional context of the hukou and authoritarian labour relations systems facilitate the informalisation of labour increasing exploitation by undermining the nominal protections afforded to workers by law. These conditions allowed for a strong divergence in the development of labour productivity and wages that underlies the upwards trend of the rate of surplus value (on manufacturing see Liu and Zhang 2012).

Competition and the Patterns of Accumulation

The following discussion of the forms of competition considers how these integrate with the extensive transformation of the wage relation as well as the distributional patterns arising therefrom in the regime of accumulation. By proxy, these patterns give insight into the relationship of the departments of production, which for theoretical reasons is not directly observable.

The absorption of additional labour and expansion of capitalist relations of production goes hand in hand with a rapid transformation of the organisational structure of capital in the course of accumulation. The share of private, shareholding, mixed ownership, limited liability and foreign invested companies in industrial output has risen from 43% in 1999 to 87% in 2011 (the period for which these data are available), while the share of the outright state-controlled sector, collective and co-operative enterprises has declined accordingly. Likewise, private and foreign-invested enterprises have made the greatest contributions to employment growth, with their collective share of urban employment rising from 21% to 58%, while that of the state-controlled and collective sectors fell from 46% to 20% (NBS via CEIC Data).

While these numbers illustrate the rapid process of industrial transformation, they do not adequately reflect the heterogenous forms of local entanglements of state and capital. Here, with an at best fragmented enforcement of common legal standards, the absence of a collective and somewhat unified system of industrial relations and a high degree of informalisation, the extensive transformation of the wage relation allows for the emergence of a variety of new types of production regimes in, both, the private sector and the diminished state sector, replacing former state-bureaucratic arrangements with more exploitative and flexible regimes of production (Lüthje 2013).

As ten Brink (2019, 148) argues, the unifying factor in this heterogeneity is a “state-capitalist dispositif” where competition between firms is embedded in and superseded by competition between local states. These seek to mobilise resources such as land and capital in search of accumulation strategies, creating a complex “hybridity” of Party-state and capital (Ngo 2018, 59–63). Fiscal decentralisation and a cadre evaluation system that emphasises measurable economic performance have provided incentives for competition between localities. These fiscal requirements and political incentives are conducive to policies facilitating local accumulation through measures supporting very high rates of investment for the build-up of industry, infrastructure construction, and urbanisation. The investment drive by local states facilitates and compliments that of corporations. In fact, accumulation was profitable enough for corporations to finance a majority of their investments from retained earnings. This allowed the share of self-raised and other funds as a financial source of total fixed asset investment in the urban economy to rise from 65% in 1995 to 84% in 2015 (NBS via CEIC Data; see also Aziz 2006, 19).

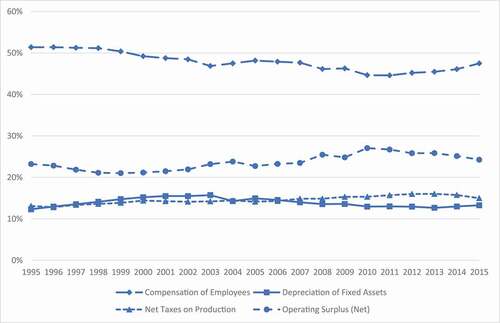

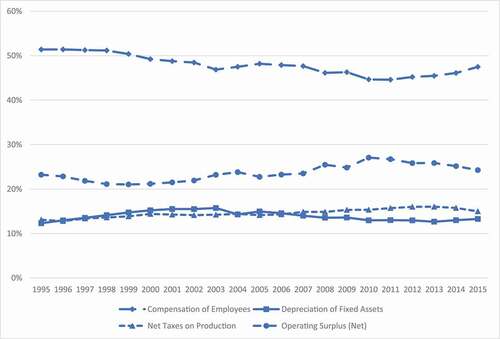

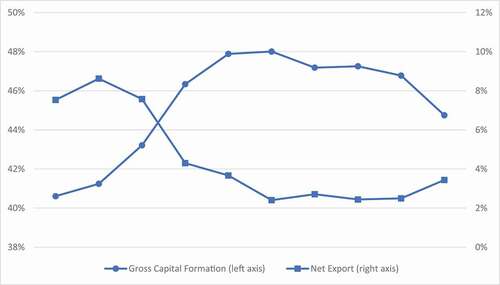

Arguably, the highly competitive character of local state capitalism has created developmental incentives and results (ten Brink 2019, 95). However, at the same time, the economy’s fragmentation into local models and centres of accumulation may also compound a tendency towards over-investment and over-accumulation that is emergent in the rapid profit- and investment-led build-up of industry and infrastructure absorbing a large pool of surplus labour (Hung 2008, 158; ten Brink 2019, 165). This process is primarily led by the expansion of department I, which is by proxy visible in national accounts and the changing composition of the GDP. On the income side of GDP, we see an increase in the share of operating surplus (profits) rising from 21% in 1999 to 27% in 2010 (see ). On the expenditure side, gross capital formation (investment) is the leading component of GDP growing from 34% in 2000 to 48% in 2011 (). As its flipside, the linkages between extensive transformation of the wage relation, labour exploitation, profits and investment caused a decline of labour’s share of national income and household expenditure (see Bai and Qian 2009; Wang and Xu 2013).

Related to its effect on primary distribution at the national level, extensive accumulation also increased income inequality between households, with the rising share of profits going to high income households (Molero-Simarro 2015, 451). Income inequality in China has grown to one of the highest levels internationally, with the Gini co-efficient reaching its peak of 0.491 in 2008, then declining to 0.462 in 2015 before rising again to 0.468 in 2018 (NBS vis CEIC Data). This income inequality is not exclusively caused by uneven regional development, which contributes less than half to the overall trend, but rather the growing income inequality between households within regions (Jain-Chandra et al. 2018). This in turn underlies an increasing inequality in household consumption (Zhao, Wu, and He 2017).

In the contexts of their respective institutional frameworks, the extensive transformation of the wage relation and competition in local state contexts combine into an extensive process of accumulation. Increases in the rate of surplus value based on the integration of highly exploitable labour go hand-in-hand with a rapid investment- and profit-led build-up of industry. The distributional effects on the national and household level bear witness to a highly uneven development of the departments of production. The same factors that enable the rapid accumulation and expansion of department I supress the growth of worker consumption, a channel for the reproduction of capital and a proportional expansion of department II. Despite the apparently uncoordinated development of the departments of production and the Chinese case exhibiting typical features of an extensive accumulation regime, accumulation has proceeded rapidly and with relatively few interruptions since the late 1990s. This then poses the question of how increases in the rate of surplus value co-ordinate with the development of the departments of production I and II, or how these constraints are lifted, to allow for the rapid and uninterrupted pace of accumulation observed in China. Given the heterogeneous accumulation strategies of competing localities and the absence of institutions and norms that would allow the wage relation to co-ordinate this relationship, this role falls to the world market.

The World Market Fix to Extensive Accumulation

China’s integration into global capitalism was initially aided by the creation of special economic zones, which facilitated the global relocation of labour-intensive production to China in the 1980s and 1990s as well as the subsequent inflow of FDI, which not only provided capital, but also technological and organisational knowledge. China’s 2001 entry into the World Trade Organization significantly lowered tariff barriers, ushering in a decade of rapid increases in the export share of GDP and consistent export surpluses. Before the GFC, from 1995 to 2007, China’s exports compared to the size of its GDP grew from about 20% to 35% (NBS via CEIC Data). While a moderate net export surplus of 1% to 4% of GDP had developed since the 1990s, this later rapidly expanded to a peak of 9% between 2004 and 2007 (see ).

Previous analyses have argued that the economic disproportionalities emerging from accumulation in China are potentially disruptive and unsustainable (see, for example, Hung 2008; Wang and Xu 2013; Zhu and Kotz 2011). Broadly generalising, according to these analyses, China’s asymmetric integration into the world market has compensated the shortfall in demand of domestic, predominantly working-class consumption caused by the profit and investment-led accumulation process. The low wage regime that contributes significantly to the competitiveness of China’s products on the world market, reinforces its dependence on exports and has made it vulnerable to “external” shocks as caused by the 2008 crisis.

However, the relevance of world market integration lies not exclusively in solving a net supply and demand problem. Accumulation does not rely on an expansion of working-class consumption as a source of demand per se. Indeed, increases in surplus value sustaining accumulation imply a relative decline in working-class consumption of total value produced. Rather, the significance of consumption lies in its role of being a constraint on the co-ordinated expanded reproduction of the departments of production. Following Aglietta’s treatment of extensive accumulation, the impulse for accumulation originating in department I by the absorption of surplus labour would override any co-ordinated development and proportionate expansion of the two departments of production, leading to frequent disruptions and a stuttered pace of accumulation. However, despite the extensive nature of the accumulation regime, the Chinese economy has undergone a rapid and relatively uninterrupted process of accumulation for over a decade since the mid-1990s, a period comparable in length with the post-war boom in the USA.

Against this background, the significance of China’s world market integration lies not exclusively in providing surplus demand for a surplus of goods produced, but in enabling an uncoordinated development of the departments of production, in the sense that changes in the rate of surplus value do not immediately impose new constraints in terms of the proportions in which the product and wages of departments I and II exchange domestically. This then enables a protracted over-accumulation of capital in department I that is not immediately checked. China’s world market integration can thus be understood in terms of a “spatial fix” mediating the contradictions of its extensive accumulation regime. It is thus no coincidence that in the Chinese case the disappearance of the world market fix reveals the effects of over-accumulation on the profit rate, as will be discussed in the following.

The New Normal

In the current phase of economic development in China, dubbed the “New Normal” in official political parlance, the end of the rapid phase of accumulation is marked by a confluence of domestic over-accumulation and the impact and aftermath of the GFC. These crisis tendencies are evident in the development of the rates of surplus value and profit, but also, absent the world market fix, in the limited ability of the existing institutions, especially those defining the wage relation, to continue mediation of the contradictions emerging in the course of extensive accumulation. As will be argued below, the New Normal presents the transition from an accumulation regime “en regulation” (Jessop 2013), where its institutional forms produce a degree of structural cohesion that is conducive to a relatively uninterrupted process of accumulation, to the exhaustion and possibly crisis of this regime, where the same institutional forms now undermine the regulated reproduction of contradictions in capitalist accumulation.

The Wage Relation under the New Normal

As the pace of accumulation begins to outpace the supply of surplus labour, the development in the rate of surplus value after 2005 reveals the limits of the extensive transformation of the wage relation. As the production of surplus value relied predominantly on the transfer of surplus labour into capitalist production relations, rather than on technological advances, these structural changes ended the decade-long rapid rise in the rate of surplus value and caused an intermittent decline. With accumulation in full swing in the middle of the 2000s, the supply changes in the labour market increased labour’s structural power and allowed workers to retain a larger share of value produced as wages rose more quickly. Labour shortages have been reported in the Pearl River Delta as early as 2003 and in other coastal and inland regions in subsequent years (Wang and Gao 2008; Wu 2007). This structural shift in labour market conditions favourable to workers was accompanied by a rise in militancy and increased attempts by non-governmental organisations to help workers bring about more equitable labour relations.

Initially, under the leadership of President and CPC General Secretary Hu Jintao, 2002–2012, these developments were met by the Party-state with efforts to regularise wage determination, reduce informal employment, reduce labour conflict, and to integrate the reform of labour relations into the overall goal of “rebalancing” an overheating economy towards domestic consumption. These aims were addressed by both legal and organisational measures like the 2008 Labour Contract Law and the trial of collective bargaining practices by the state-affiliated All-China Federation of Trade Unions.

However, as Lee (2016) argues, these developments did not represent a fundamental change in the Party’s relation with the working class or the empowerment of workers as a class for themselves. Indeed, after the turn of the decade, the economic slowdown has produced a heightened sense of threat in the Party leadership, and the overriding macro-economic policy goal is to secure high levels of employment (China Daily, March 15, 2019). In terms of labour relations, the Party-state again seeks “encapsulating” control and restricts collective bargaining in favour of the mediation of capital–labour relations by Party-led trade unions (Howell and Pringle 2019, 224). Policies to improve the condition of the working class, including the enforcement of labour laws and regulations, thus remain subordinate to the overarching goal of creating social stability through economic growth.

Against his background, it appears highly likely that the norms and institutions governing the wage relation, affecting wage determination and other conditions of employment, will remain subordinate to the heterogenous strategies of accumulation developed in local state–capital nexuses. Consequently, instead of a fundamental shift away from the conditions created by the extensive transformation of the wage relation in the 1990s and 2000s, we see instead these conditions carried forward into the New Normal of slower economic growth, with sustained processes of informalisation and processes of industrial upgrading that perpetuate and exploit these conditions:

The weakness of collective labor standards and the scattered character of collective mobilizations around basic issues of wages and working conditions, as well as the underlying social cleavages of the workforce explain to a large degree why the upgrading of products, production technologies and organization in the wake of the 2008–09 global recession has not resulted in major restructuring of production regimes and work practices (Lüthje 2014, 18–19).

Industries upgraded by automation and digitalisation continue to make use of a low-skilled, low-wage labour force, supported by only a small segment of high-skilled workers in high-tech industries (Butollo 2014). Automation goes hand-in-hand with a confirmation of existing neo-Taylorist forms of work organisation, reducing the need for skilled work while allowing an intensification of unskilled labour. At the same time, automation and digitalisation are linked to highly flexible supply chains, relying on equally flexible – that is, precarious – labour relations (Butollo and Lüthje 2017).

While the manufacturing share of total employment has begun to decline since 2012, employment growth in the service sector has accelerated significantly. Here, the rapidly growing urban “sharing economy” (gongxiang jingji) employs, amongst others, migrant workers who no longer find employment in manufacturing. In 2017, it provided about 70 million jobs (about 15% of urban employment) of which, however, only 10% were jobs with sharing economy platform providers themselves, that is, in management, marketing and software development (Sharing Economy Research Center of the Government Information Center 2018). The remainder are likely precarious and labour-intensive jobs in the service economy, such as in food delivery, passenger transport and courier services.

Overall, the trend towards informalisation continues, with Liang, Appleton, and Song (2016, 14) referring to a “dramatic switch from formal to casual employment” around the turn of the last decade. As mentioned above, the share of informal work in urban employment was up to 75% in 2017. This shift encompasses all sectors of the economy, including “manufacturing, real estate, hotel and catering, wholesale and retail, and all sorts of public services … all of which saw reductions in probabilities of formal employment” including industries previously known for more stable employment relations (Liang, Appleton, and Song 2016, 20). The Labour Contract Law has contributed to this rise by formally legalising the use of dispatch work (Huang 2017, 4). This provides a legal framework for the already widespread use of informal next to formal labour in industry, as analysed, for example, by Zhang (2015) in her study of “labour force dualism” in the automotive industry.

The wage relation under the New Normal thus continues to reproduce the highly precarious labour market conditions and production relations that underlie the rapid period of extensive accumulation. These developments have reversed an intermittent fall in the rate of surplus value from 2006 to 2009 and have subsequently produced a modest cumulative increase in the rate of surplus value of 10% between 2009 and 2015. Despite an average increase in real wages and a modest increase in the labour income share of GDP in recent years, the conditions of the wage relation continue to reproduce the stark divisions in household income and consumption inequality that have been characteristic of the accumulation process.

In the absence of more comprehensive changes to the wage relation, two problems emerge. Firstly, as the following analysis will show, the modest increase in the rate of surplus value is insufficient to avert a fall in the rate of profit. Secondly, with a diminishing role for the world market and the spatial fix it provides, the fragmented and heterogenous forms of co-ordination of the wage relation are unlikely to be conducive to a co-ordinated expansion of the departments of production.

Global Crisis and Domestic Over-accumulation

The spatial fix provided by China’s integration into the world market has at the same time exposed the economy to the ostensibly external shock of the GFC and its aftermath – ostensibly external in so far as the economy’s insertion into the world market has been integral to developments that have contributed to the crisis in the first place (see Hung 2008; Helleiner 2011; Pettis 2013).

The GFC has had a long-lasting impact on the world market. The value of global trade compared to global GDP, which rose from about 18% in the mid-1980s to almost 31% in 2008, has since stagnated (World Bank 2019). A similar shift is underway within China. Not only did the Chinese economy see a rapid contraction of its export surplus after 2007, but also a decade-long relative decline in the volume of exports from 35.4% of GDP to only 19.5% in 2018 (World Bank 2019). Similar tendencies are observable for imports.

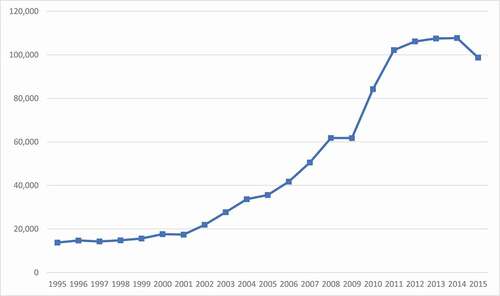

Reacting to the GFC, the government implemented a stimulus programme in 2009 and 2010 that helped to maintain high growth rates and employment. The stimulus was designed to work through the established institutions of the local state–capital nexus reinforcing the investment-driven nature of China’s accumulation regime, with a 5% increase in the investment share of GDP from 2008 to 2010 making up for a corresponding decline of the export surplus ().

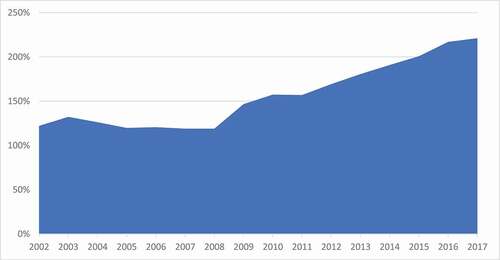

The original stimulus of RMB 4 trillion was financed by local governments through off-balance sheet vehicles. By 2015, local governments may have raised up to 48 trillion in debt through these vehicles to invest in real estate, infrastructure and other capital-intensive projects (Bai, Hsieh, and Song 2016, 152). Such leveraging has directly contributed to the rapid expansion of shadow banking through off-balance sheet lending and borrowing by local governments, banks, and corporations, which in turn facilitated a similarly rapid expansion of debt in the corporate sector (Chen, He, and Liu 2018; Tsai 2015 ). Non-financial corporate debt rose from 97.5% of GDP in 2008 to 158.3% in 2015 (Bank of International Settlements 2019). Overall, according to the People’s Bank of China’s measurement of total debt, total social financing, China’s debt to GDP ratio, which declined to a value of 119% of GDP until 2008, subsequently rose to 221% in 2017 (see ). Non-official estimates were at just under 300% of GDP in the same year (Financial Times, June 24, 2018).

Within the structural constraints of the extensive regime of accumulation, the stimulus programme and subsequent expansion of debt thus served as a stand-in for the spatial fix previously provided by the world market, lifting the constraint for the co-ordinated development of the departments of production by shifting the problem to a complex of local state and financial systems that provides a temporal debt-fix to the problem. However, sustaining the rapid pace of accumulation in this way has exacerbated the tendency towards over-accumulation in department I, which now makes itself felt as a decline in the rates of profit.

Over-accumulation and Profitability

presents a measurement of the general rate of profit p’ and its net rate r’. Whereas p’ delineates the upper boundary of profitability determined by the ratio of total surplus value produced and the cost of constant fixed capital K, r’ measures actual average profitability by additionally considering how surplus value has been shared between productive and non-production activities. The tendency of the rates of profit to fall in the current period, while differing in terms of values, confirms the general trend exhibited by estimations of the profit rate based on different methodological approaches, for example Li (2017), Li (2020) and Qi (2018).

The general rate of profit (p’) reached its peak in 2007 at 27% before it declined in two steps to about 22% in 2015, wiping out the gains made during the previous decade. As p’ simply measures the ratio of surplus value produced against the cost of constant capital, it makes sense to observe the rate of surplus value against the development of the composition of capital, that is, the ratio of the value of constant capital and the value of labour power in reproduction, which in the course of accumulation has increased from 555% in 1995 to 891% in 2015 (see ).

Until 2007 the increase in the rate of profit reflects the fact that during the period of rapid accumulation, the rise in the composition of capital mostly keeps pace with a rise in the rate of surplus value, indicating a close link between the pace of accumulation and the transfer of surplus labour into capitalist production relations. As both slow in growth towards the turn of the last decade, the initial fall in the rate of profit after 2007 is attributable to the combined effect of the changes in the structural bargaining power of labour, causing a decline in the rate of surplus value and the immediate impact of the GFC on exports, significantly reducing the ability of capital to realise a share of value produced.

Starting in 2010, the composition of capital grows significantly faster than the rate of surplus value leading to a further decline in the rate of profit due to the rise in the composition of capital exceeding the rise in the production of surplus value. In the wake of the GFC, driven by the stimulus programme and a rapid expansion of debt that sustain the extensive accumulation regime and its uncoordinated development, this finally reveals a state of over-accumulation that directly impacts profitability.

Contrary to p’, the net rate of profit (r’) is on average relatively stable in the period under observation, but almost halves between 2011 and 2015 due to the combined impact of the cost of capital and an increase in the share of surplus value consumed by non-production activities, such as the circulation of capital and commodities, or social reproduction. Roughly speaking, the aggregated share of surplus value consumed by these activities (U) increases from 56% in 1995 to 76% in 2015 (). This increase takes place in two pushes. The first, between 1995 and 2001, is caused predominantly by an increase in the share of surplus value appropriated by the trade sector as profit from the circulation of commodities, which at that point in time likely results from the ongoing commercialisation of the economy.

After 2010, in the second push, half of the 10% increase in U can be explained by an increase of the share of surplus value appropriated as profit by the financial sector, which results from the expansion of the financial sector in the wake of the government stimulus. The rest is almost completely due to an increase in the consumption of surplus value by non-production labour, reversing a trend of a relative decline of this variable since 1995. Previously, this trend had prevented a decline of the net rate of profit due to the rate of surplus value falling after 2005. However, under the New Normal, the share of manufacturing activities has decreased, whereas the services sector, where much of the labour of circulation and reproduction is found, expands more quickly.

Significantly, in addition to the rates of profit, the mass of profit accrued to the production sector of the economy stagnates after 2011 and slightly declines after 2014, revealing clear material limitations to the continued reproduction of the accumulation regime. Under current conditions, the increases in the rate of surplus value achieved are insufficient to sustain the pace of accumulation and profitability.

The decline not only in the rates of profit, but also in the mass of profit accrued to the production sector presents a clear potential for crisis, which in the case of the Chinese economy takes the form of a protracted slow-down supported by an accumulation of debt.

Conclusion

The regulated reproduction of the Chinese accumulation regime is now impeded by an open emergence of the contradictions that have developed in the process of extensive accumulation. With the diminished ability of the world market to provide a spatial fix after 2008, the extensive accumulation process, relying on the uncoordinated and rapid expansion of department I, now only continues without interruptions because the restraints on the realisation of value imposed by the relation of the departments of production are lifted by a rapid increase in debt. At the same time, extensive accumulation has exhausted itself as a means to increase the rate of surplus value through a predominantly quantitative expansion of the wage relation. Continued accumulation in department I thus manifests as over-accumulation and a pronounced fall in the rates of profit, which can be attributed to an accelerated rise in the composition of capital. In addition, a greater share of surplus value is appropriated by finance and by the labour of distribution in the expanding service and “sharing” economy. The institutional conditions of the wage relation that previously caused a rise in the rate of surplus value, now are not only no longer facilitative to such a rise, but instead facilitate a redistribution of value from production to non-production activities.

With Aglietta (1979, 353–356), these tendencies can then be interpreted as the historically necessarily combined articulation of a transgression of the constraints of realisation and over-accumulation causing a decline in the profit rate. Fundamentally, they are the result of a breakdown in the extensive accumulation regime’s ability to mediate its contradictions by allowing the accumulation process to systematically transgress the constraints normally imposed by the combined development of the departments of production, by displacing these constraints in time (debt) or space (world market).

If we disregard the possibility of another fundamental change in the mode of production in China, the conditions of the wage relation, originally underlying rapid accumulation, now present obstacles to producing social transformations that may, in whatever limited fashion, overcome the problems of uncoordinated development of the departments of production and over-accumulation in a changed regime of accumulation.

The ongoing processes of industrial upgrading exploit the existing conditions of the wage relation rather than transform them. The informalisation of work continues within low-wage regimes of production embedded in the heterogenous contexts of competing local strategies of accumulation. Breaking out from these local contexts to a certain extent may be the national oligopolistic structures developed by sharing economy service providers, which, however, also drive informalisation and precaritisation in the urban economy.

On the one hand, these processes of industrial transformation are apparently unable to produce increases in the rate of surplus value that are sufficient to avert a fall in the rate of profit. On the other hand, absent the enforcement of labour standards and established mechanisms for sectoral collective bargaining and given the heterogeneity of production regimes, the institutions governing the wage relation are unable to provide mechanisms to co-ordinate the development of the departments of production in a way that would allow for relatively uninterrupted accumulation. Both problems are furthermore exacerbated by the highly unequal distribution of incomes and consumption, as, from a regulation theoretical perspective, it hinders the establishment of a broad norm of consumption that would underlie both the production of relative surplus value as well as co-ordinated reproduction. Given the conjunction of both a deterioration in economic fundamentals as well as the apparent inability of the wage relation and other institutional forms to continue to mediate their underlying contradictions, it appears justified to speak of a moment of structural crisis signalling an exhaustion of the accumulation regime.

As the discussion of the New Normal has shown, the possibilities for a fundamental transformation of the wage relation are furthermore constrained by questions of political rule and legitimacy, which come together in the CPC’s self-prescribed role as the ultimate arbiter of class relations and provider of “social stability.” The CPC will thus avoid significantly undershooting targeted growth rates or allowing high open unemployment to emerge, and, as its tightening grip on labour relations shows, it will attempt to suppress autonomous class organisation and conflict. It thus seeks to suppress two of the most important factors that have historically driven transformative change in capitalism, the disruptions caused by crises and the political changes caused by the class struggle. It appears likely that the CPC will attempt to moderate labour-capital relations in ways that secure employment and accumulation under the given conditions, while seeking for a reform path compatible with its own political aspirations. Meanwhile, the imperative to allow accumulation to continue at a sufficient pace to, on the one hand, secure employment and wages, and, on the other, income from profits, will likely have to be bought at the expense of debt and other monetary measures to further loosen the constraints for the realisation of value. For the great difficulties inherent in transitioning away from a model of rapid extensive accumulation, the history of the East Asian “developmental states,” which relied on similar patterns of accumulation as China has, is instructive in this regard (see Pirie 2018).

These difficulties are apparent in the Party’s ad hoc management of the current economic downturn. After the expansion of debt in the first half of the decade, it has become official policy to restrain credit growth in an effort to enforce the social validation of investments and to increase efficiency in the economy (that is, Xi’s supply-side reforms). However, whenever growth rates appear to miss the official targets set, for example, when, as in 2018, the limited ability of household consumption to support the pace of economic expansion becomes apparent, the government responds with new stimulus, new debt and looser monetary policy (Financial Times, November 14, 2018). What these interventions serve to alleviate are precisely the difficulties that, according to Aglietta, characterise extensive accumulation, the problem of the co-ordinated expansion of the departments of production inhibiting a regular pace of accumulation.

Given these difficulties, a protracted period of “muddling through” characterised by ad hoc crisis management appears as likely as the successful transition to a new growth model. What effectively amounts to a suppression of the contradictions of capital accumulation of course only means their displacement in space and time, or the shifting around of the burdens they impose on society. It is thus no coincidence that under Xi Jinping the Party’s control over all aspects of life has extended and intensified. In a 2019 address to the Central Party School, Xi warned that, at this point in time, China’s development had accumulated and concentrated various risky challenges, emphasising the need for unity in the economic and political “struggles” (douzheng) confronting the Party (Xinhua 2019).

Methodological Appendix

The method relies on input-output tables, which have been published for the years 1995, 1997, 2000, 2002, 2005, 2007, 2010, 2012, and 2015 on production approach measurements of GDP available from the NBS (via CEIC Data), and on national income statistics (National Bureau of Statistics 1995, 1997, 2019).

Official Chinese economic data are often viewed with suspicion regarding their accuracy, because of methodological shortcomings and because of the political significance attached to the official figures. While several methodological and institutional problems exist, negatively affecting data quality, Holz (2014, 324) finds no evidence of falsification. In any case, NIPA data, while possibly inaccurate in absolute levels, appear to accurately reflect relative movements. As this analysis does not crucially rely on absolute numbers, but rather on the relative movement of categories, the quality of Chinese statistical data appears to be sufficient.

Details on Differentiating Productive and Non-productive Activities

As discussed in the article, measuring Marxian categories requires the preparation of national accounts data to differentiate between production and non-production sectors as well as between productive labour and unproductive labour in the production sector for estimates to be representative of labour value.

Firstly, this involves remapping the 42-column input-output tables (33 columns in 1995, 40 in 1997) to differentiate between the production sector (producing commodities and services for intermediate or final consumption) and the non-production sector of the economy (Table A1). The following categories were dropped entirely due to their small size and because they can be assumed to not be engaged in the production or circulation of value: water, environmental and public facilities management; education; health and social work; culture, sports and entertainment; public administration, social security and social organisation.

Secondly, productive and unproductive labour in the production sector are differentiated based on occupational statistics from the 2000 population census. The data lists numbers of employees in occupational groups for different industrial sectors. The groups are: (i) state, Party and enterprise cadres; (ii) professional and technical personnel; (iii) clerical workers and associated staff; (iv) commercial and service workers; (v) agriculture, forestry, animal husbandry, fisheries and water conservancy production personnel; (vi) production, transport equipment operators and related workers; and (vii) others. Categories (i), (ii) and (iv) as unproductive labour and the rest as productive labour and can thus calculate ratios of productive workers of industries within the production sector. With more detailed occupational data not available, this is an imperfect method, as the ratio of productive and unproductive labour is held constant over the years. However, it appears a sensible assumption that the share of non-production labour usually rises in the course of industrial development, so that, if more recent data were available, this would confirm the trends in Marxian categories observed in the analysis in terms of surplus value and profitability.

Details on Preparing NIPA Data

Unfortunately, income approach data are only made available as provincial data. Constructing a coherent income accounts series requires that: (i) provincial data are made to correspond to national data; and (ii) methodological changes made by the NBS between years are accounted for. On (i), while the NBS does not publish national income accounts, it does provide provincial data. In theory, the aggregate of provincial income accounts should be identical to national production accounts. However, aggregate gross value added of provincial income accounts regularly surpasses that of national production accounts by several percentage points. Because certain categories from income accounts and others from production accounts are estimated, this deviation needs to be corrected for by dividing gross value added of national production accounts by the share of the components of aggregated provincial income accounts for each year, thus constructing a compatible data series.

On (ii), the methods used by the NBS to estimate income approach components of GDP have undergone revisions in the wake of the 2004 and 2008 national economic censuses. Both have affected the measurement of the share of compensation of employees and operating surplus in GDP. Until and including 2003, the NBS treated the income of self-employed proprietors as wages and has added it to the labour income share. Beginning in 2004, their income has instead been treated as profit-like income and added to the profit share. Without corrections, the data records a steep 5% drop in labour income share between 2003 and 2004 and a corresponding increase in the profit share. This change is rolled back by Zhou, Xiao and Yao’s (2010) method. After 2008, the NBS made an about-turn in their method of calculating profit- and wage-like income of the self-employed in national income (Xu 2011), so that the post 2008 data is methodologically similar to pre 2004 data and left untouched.

Details on the Estimation of Marxian CategoriesEstimating VAp + VAtt+ Mtt+ RYp + RYtt

VAp is the sum of the production sector’s value added in input-output tables. VAtt is the sum of the trade sector’s value added in input-output tables and represents value produced in the production sector and appropriated by the trade sector in exchange for its services. Taxes paid by these sectors are included as they represent transfers of value produced in the production sector to the state. Depreciation is not included as it represents the replacement costs of existing capital stock and thus does not add to value.

In the System of National Accounts, gross value added of the trade sector is usually recorded as the trade margin appropriated by that sector and this is also true in the Chinese case (Shaikh and Tonak 1994, 23; National Bureau of Statistics of China 2009; OECD 2000). Thus, VAtt excludes that share of value produced in the production sector that has been appropriated and used for intermediate consumption. This is accounted for in Mtt, intermediate inputs of the trade sector, value created in the production sector and consumed in the process of distribution, which does not show up as a share of GDP in national accounts, but is a share of value produced and thus needs to be included in VA. Mtt is estimated based on the trade sector’s intermediate inputs to the production sector in input-output tables.

The royalties paid by the production and trade sectors to finance, RYp and RYtt, also present transfers of value produced in the production sector to the non-production sectors of the economy, in part via a detour through the trade sector. To estimate VA, intermediate inputs of finance, which are discounted from GDP in national accounts, must be included.

As input-output tables are only published in certain years, input-output data for VAp, VAtt, Mtt, RYp, and RYtt are joined with GDP data from the China Statistical Yearbook to construct a continuous and coherent annual series (for an analogous Greek calculation, see Maniatis 2005, 499).

The procedure for VAp and VAtt: For each year available in the 1995–2015 period, the ratio of VA in input-output tables to VA in annual GDP is calculated. This ratio is linearly interpolated between missing years. The resulting ratios are then multiplied with the current NBS GDP series at a continuous data series.

The procedure for Mtt, RYp, and RYtt: For each year available in the 1995–2015 period, the ratio of total intermediate inputs of the trade sector to total value-added of the trade sector in GDP is calculated and the ratio is linearly interpolated for the missing years in the period. The resulting ratios are then multiplied with the current NBS GDP series, which provides a continuous data series, to estimate intermediate inputs. The procedure employed to calculate RYtt and RYp is analogous to the one for Mtt.

Estimating V

Firstly, for each industry in the production sector, its ratio of productive to unproductive labour is multiplied with wages paid, found in input-output tables for benchmark years. In the aggregate this yields the wage bill of productive workers in the production sector. Dividing the wage bill of productive workers in the production sector by the total wage bill given in input-output tables for benchmark years yields the ratio of productive workers’ wages to unproductive workers’ wages in the total wage bill. This ratio is used to make up for missing values for 1995–2015 and can be multiplied with total compensation of employees given in the income accounts data to find V, total wages paid to productive workers in the production sector for each year and its counterpart, the wages of unproductive labour (Wul). It should be noted that this procedure assumes that the average wage of non-production workers is equal to the average wage of production workers, likely over-estimating V.

Secondly, wage-like income of the self-employed and small proprietors is either originally or due to our adjustments already included in total compensation of employees, so that the data fits the definition of V*. This also means, however, that due to the estimation procedure, I discount a certain share of wage-like income as unproductive labour, which is an unfortunate necessity due to the limited availability of wages data and employment figures.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank anonymous reviewers for their constructive and detailed comments and critique and Dr Michael Connors for his invaluable support.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1. Estimated as the difference of the surveyed urban population and population registered with non-agricultural hukou, with data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China Statistical Yearbook and China Population and Employment Statistics Yearbook (various years).

References

- Aglietta, M. 1979. A Theory of Capitalist Regulation: The US Experience. London: Verso.

- Aziz, J. 2006. “Rebalancing China’s Economy: What Does Growth Theory Tell Us?” Washington, DC: IMF Working Paper WP/06/291.

- Bai, C., C.-T. Hsieh, and Z. Song. 2016. “The Long Shadow of China’s Fiscal Expansion.” In Brookings Papers on Economic Activity: Fall 2016, edited by J. Eberly and J. Stock, 129–181. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press.

- Bai, C. and Z. Qian. 2009. “Guomin shouru de yaosu fenpei: tongji shuju beihou de gushi” [Factor Income Share in China: The Story Behind the Statistics]. Jingji Yanjiu [Economic Research] 9 (3): 27–41.

- Bank of International Settlements. 2019. Total Credit to Non-Financial Corporations (Core Debt). Retrieved October 29 2019, . https://stats.bis.org/statx/srs/table/f4.1.

- Boyer, R. 1990. The Regulation School: A Critical Introduction. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bramall, C. 2008. Chinese Economic Development. London: Routledge.

- Brenner, R., and M. Glick. 1991. “The Regulation Approach: Theory and History.” New Left Review 188: 45–119.

- Butollo, F. 2014. The End of Cheap Labour? Industrial Transformation and “Social Upgrading” in China. Frankfurt: Campus.

- Butollo, F., and B. Lüthje. 2017. “‘Made in China 2025’: Intelligent Manufacturing and Work.” In The New Digital Workplace. How New Technologies Revolutionise Work, edited by K. Briken, S. Chillas, M. Krzywdzinski, and A. Marks, 42–61. London: Palgrave.

- Cai, F., Y. Du, and M. Wang. 2010. Employment and Inequality Outcomes in China. Paris: OECD. Accessed August 23, 2014. http://www.oecd.org/employment/emp/42546043.pdf.

- Chan, K. 2009. “The Chinese Hukou System at 50.” Eurasian Geography and Economics 50 (2): 197–221.

- Chen, Z., Z. He, and C. Liu. 2018. “The Financing of Local Government in the People’s Republic of China: Stimulus Loan Wanes and Shadow Banking Waxes.” Manila: ADBI Working Paper Series 800.

- Coates, D. 2005. “Paradigms of Explanation.” In Varieties of Capitalism, Varieties of Approaches, edited by D. Coates, 1–26. London: Palgrave.

- Fligstein, N., and J. Zhang. 2011. “A New Agenda for Research on the Trajectory of Chinese Capitalism.” Management and Organization Review 7 (1): 39–62.

- Friedman, E., and C. Lee. 2010. “Remaking the World of Chinese Labour: A 30 Year Retrospective.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 48 (3): 507–533.

- Harvey, D. 2001. “Globalization and the Spatial Fix.” Geographische Revue 2 (3): 23–31.

- Helleiner, E. 2011. “Understanding the 2007–2008 Global Financial Crisis: Lessons for Scholars of International Political Economy.” Annual Review of Political Science 14: 67–87.

- Holz, C. 2014. “The Quality of China’s GDP Statistics.” China Economic Review 30: 309–338.

- Holz, C., and Y. Sun. 2018. “Physical Capital Estimates for China’s Provinces, 1952–2015 and Beyond.” China Economic Review 51: 342–357.

- Howell, J., and T. Pringle. 2019. “Shades of Authoritarianism and State-Labour Relations in China.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 57 (2): 223–246.

- Huang, P. 2017. “China’s Informal Economy, Reconsidered: An Introduction in Light of Social-Economic and Legal History.” Rural China 14: 1–17.

- Hung, H.-F. 2008. “Rise of China and the Global Overaccumulation Crisis.” Review of International Political Economy 15 (2): 149–179.

- Jain-Chandra, S., N. Khor, R. Mano, J. Schauer, P. Wingender, and J. Zhuang. 2018. “Inequality in China–Trends, Drivers and Policy Remedies.” Washington, DC: IMF Working Paper WP/18/127.

- Jeong, G., and S. Jeong. 2020. “Trends of Marxian Ratios in South Korea, 1980–2014.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (2): 260–283.

- Jessop, B. 2013. “Revisiting the Regulation Approach: Critical Reflections on the Contradictions, Dilemmas, Fixes and Crisis Dynamics of Growth Regimes.” Capital & Class 37 (1): 5–24.

- Knight, J., and L. Song. 2005. Towards a Labor Market in China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Lee, C. 2016. “Precarization or Empowerment? Reflections on Recent Labor Unrest in China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 75 (2): 317–333.

- Li, M. 2017. “Profit, Accumulation, and Crisis: Long-Term Movement of the Profit Rate in China, Japan, and the United States.” The Chinese Economy 50 (6): 381–404.

- Li, M. 2020. “The Future of the Chinese Economy: Four Perspectives.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (2): 228–247.

- Li, Z., and H. Qi. 2014. “Labor Process and the Social Structure of Accumulation in China.” Review of Radical Political Economics 46 (4): 481–488.

- Liang, Z., S. Appleton, and L. Song. 2016. “Informal Employment in China: Trends, Patterns and Determinants of Entry.” Bonn: Institute of Labor Economics, IZA Discussion Paper Series No. 10139.