The physician must … have two special objects in view with regard to disease, namely, to do good or to do no harm.

A landmark study entitled “To err is human: building a safer health system” (Donaldson et al. Citation2000), reported on the extent of harm caused by clinical errors in the health system in the United States of America. Up until this time, the discussion of clinical errors in the medical system occurred mainly behind closed doors, and systems that recorded these events and attempted to minimise these errors were largely non-existent. There was a wide-spread culture of shaming clinicians who admitted making errors and, when coupled with the risk of litigation, this meant that mistakes were not acknowledged, or were deliberately hidden from patients and other staff.

We can learn by analysing and reflecting on our errors, by building safer processes, improving our knowledge and increasing our vigilance. However, there is also a need to acknowledge the effects that making an error can have on our sense of confidence, self-worth and professional competence. As working veterinarians we must build our resilience so that, whilst working to minimise the risk of clinical errors, we can acknowledge and learn from them when they occur. For those of us training students and more junior veterinary staff, how we respond to our own mistakes is as important as how we respond to theirs.

The scale of clinical errors in human medical and veterinary practice

The World Health Organisation estimates that 12.7% (lower to middle income countries) to 14.2% (higher income countries) of hospitalised patients throughout the world will experience an adverse event when hospitalised (Jha et al. Citation2013). Using a conservative approach, the authors estimated that there are at least 43 million injuries each year due to medical care. The types of errors identified include improper transfusions, falls, pressure ulcers, burns, wrong-site surgery, restraint-related injuries or death, and adverse drug events (including dose, type and frequency of administration) (Athanasakis Citation2019).

The scale of clinical errors in veterinary hospitals is much more difficult to establish due to a widespread lack of reporting systems. In a review of clinical records from three veterinary hospitals in Europe (two small, one large) a total of 560 events were recorded over 3 years, equating to 5.3 errors per 1000 patient visits. Drug errors were the most frequently reported incident in all three hospitals, followed by failures of communication, and 15% of all incidents resulted in patient harm (Wallis et al. Citation2019). These figures are the only clear evidence we have of the type and frequency of clinical errors in veterinary practice. It is clear that a “blame and shame” culture around medical errors is still prevalent in the veterinary profession (Oxtoby and Mossop Citation2019).

The proximate causes of clinical error

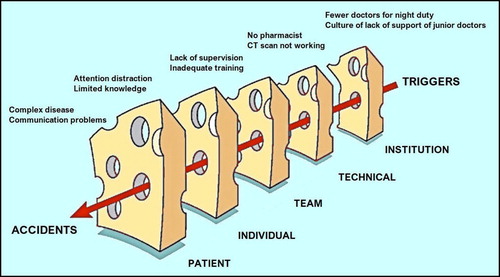

A popular model to help understand and analyse the causes of clinical errors is the Swiss cheese model (Reason Citation2000). This proposes that in any complex organisation or structure there are multiple barriers to the occurrence of errors (the slices of cheese), but there are often defects in these defences (holes in the cheese). When a series of triggers, events or circumstances align the holes (), then errors result, leading to patient harm. See for an example of this model as applied to human medicine.

Figure 1. An example of the Swiss cheese model for understanding accident causation as it relates to human medicine. Adapted from Reason (Citation2000).

This approach is most often used at an organisational level to promote multiple layers of safe practice to minimise the risk of errors causing harm. The review of a clinical error needs to encompass both the active errors of the individuals involved and the latent failures of the organisation, facility, equipment or culture.

Safe working environments that are likely to reduce the frequency of errors include competent management systems, good equipment that is well maintained and reliable, skilled and knowledgeable teams, good communication protocols especially at handovers, reasonable work schedules, and well-designed jobs with clear guidance on desired and undesired performance. All team members need to be working together to prevent one another’s mistakes. However, for this to work there has to be a culture of good teamwork operating, and all staff need to be empowered to speak out and be heard. As reported in a review of human surgical and anaesthesia teams, psychological barriers, such as professional silos and hierarchies, can increase the chance of communication failures within teams resulting in patient harm (Weller et al. Citation2014).

There are many types of clinical errors. Cognitive error, not lack of knowledge, is the leading cause of human medical mistakes (Goh Citation2019). These cognitive errors may be due to a variety of unconscious biases in the attending clinician. Further, cognitive error is exacerbated by the stress response leading to constrained thinking. The fear of making a further mistake compounds the problem creating repetitive thinking rather than problem solving. Cognitive biases are the mental short cuts we take that aid our decision making that sometimes lead us astray. These include a reliance on pattern recognition, diagnosis momentum (failure to re-examine an existing diagnosis), confirmational bias (remembering a similar presentation), and search satisfying bias; that is, stopping at the first plausible explanation (O’Sullivan and Schofield Citation2018). There are several constraints on diagnostic procedures that render veterinarians more susceptible to cognitive bias in their clinical reasoning. These include the size of patients, clients' financial resources and limited availability of diagnostic tests.

The clinician’s response to error

As individuals we need to acknowledge and reflect on our own errors if we are to improve. However, there are internal and external barriers to this. Inherently, none of us like to admit to ourselves that we were wrong. Further we worry about what the error will mean for our reputation with colleagues and clients. If we are working in a large institution, we may also be concerned about possible disciplinary proceedings. Errors can make us question our competence and strengthen feelings of imposter syndrome (Wu Citation2000).

Based on these factors, it is not surprising to discover that many medical errors are not disclosed to colleagues, clients or to employers. In the human medical sector, estimates of under-reporting of clinical errors range from 50 to 90%. In the veterinary profession, the underlying attitude to clinical errors is still mired in the “blame and shame” approach or a tendency to deny that these errors occur.

Failing to acknowledge our fallibility puts more at stake than our patients’ safety and our own learning. Even if we hide these errors from others, they can cause deep wounds to our own sense of competency and self-worth. Wu (Citation2000) describes some of the consequences on his colleagues to include anger, defensiveness, callousness or distress. In the long run, some clinicians can be deeply wounded, lose their nerve, burn out, or seek solace in alcohol or drugs.

Veterinary staff are perhaps more susceptible to the damaging psychological effects of clinical practice because of their relative isolation, smaller support teams, and lack of time for strategic planning and formal debriefing in comparison to their colleagues in human health. A counter-argument to this is that well-functioning small teams can enhance comradery and provide an excellent environment where social support and other tools used effectively can reduce damaging effects and enhance resilience (Holcombe et al. Citation2016).

Disclosing errors to clients

In human medical practice, disclosure of mistakes is encouraged, as in the long term it results in fewer medical malpractice suits and increased patient satisfaction. People are more likely to pursue legal action if they feel there has been an attempt to cover up an error.

There is controversy around disclosure strategies. For example, many clinicians feel that an error that results in no clinical harm should not be disclosed. Similarly, there is often consideration given to partial disclosure rather than a full explanation of events. The idea of incremental disclosure is that information about the mistake should be explained slowly, ensuring the client understands the previous information before adding further detail. This approach allows the client some absorption time to comprehend that a mistake has been made, and is designed to proceed on the client’s time scale, rather than the clinician’s desire to get the disclosure over with quickly. One key component of disclosure is that a detailed revelation of the harm associated with the mistake needs to be conveyed (Petronio et al. Citation2013).

Most people expect an apology when a mistake has been made, but many insurers actively discourage such apologies as an admission of liability. It is clear from the medical literature that withholding an apology when disclosing a mistake is more likely to increase client dissatisfaction with the process. The two components of an apology should be to convey the clinician’s wish to provide emotional support and to acknowledge that the clinician/hospital have learnt from the mistake and will take steps to ensure it doesn’t happen again. Petronio et al. (Citation2013) state that a full apology should convey accountability and culpability, a promise of corrective actions, and an explanation of the circumstances that lead to the mistake. Apologies should not include justifications that may be interpreted as denials of fault, and there should be no requests for forgiveness within the apology, which has the effect of shifting focus from the needs of the client to those of the clinician.

How we respond to others’ mistakes

As we progress through our careers, we take responsibility for teaching and supervising others, whether they be colleagues, team members or students. How we respond to their mistakes, as well as our own, can have a profound impact on the future careers and well-being of these people. A study of medical supervisors found that their initial corrective responses were based on reducing the likelihood of the specific error recurring, but also extrapolating the lesson to prevent or reduce the incidence of similar errors (Mazor et al. Citation2005). This involved bringing the error to the trainees’ attention, and encouraging them to recognise and assume appropriate responsibility for the mistake. This usually involved a one-on-one discussion about how and why the error occurred and checking the trainee understood the procedures or protocols that should have been followed to prevent the error. However, most supervisors judged that their main role was in helping the trainees to address the emotional impact of the mistake on their esteem and sense of competence.

Several barriers to the teaching opportunities that arise when mistakes are made were identified by the supervisors. These included a lack of time or opportunity, or an unwillingness to confront the trainee with their mistake due to the emotional reactions that might ensue. Many of these issues relate to the supervisors’ own experiences with management of medical errors as well as the personality of the trainee involved.

These processes are most appropriate in situations when there are genuine errors from otherwise competent and ethical trainees. It should be acknowledged that these processes will not help when a trainee or clinician is truly incompetent or unethical. Mazor et al. (Citation2005) state that this small subset of people should be managed through formal human resources processes designed to remove them from situations where they may cause harm.

How can we build and model resilience to clinical errors?

Many authors acknowledge that clinical errors can erode the self-confidence and competence of clinicians, leading to maladaptive coping strategies such as alcoholism, drug addiction and other forms of self-abuse. There are disproportionately high levels of anxiety and depression among veterinary professionals and much higher suicide rates than for the general population (Waters Citation2019). A survey by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention of >10,000 veterinarians in the United States of America in 2014 determined that more than 1 in 6 veterinarians had thought about suicide and nearly 1 in 10 had ongoing serious psychological distress (Moses et al. Citation2018). The psychological distress caused by clinical errors is likely to be one factor among many that contribute to these statistics.

The concept of physician self-care along with social support (Gardner and Hini Citation2006) is emerging as a way to reduce these statistics. Most veterinarians have no formal training in self-care or recognising the symptoms of maladaptive behaviours (Moses et al. Citation2018). The basis of self-care for clinicians is developing a spectrum of knowledge, skills, and attitudes including self-reflection and self-awareness, recognising appropriate professional boundaries, and developing skills to cope with grief and bereavement (Sanchez-Reilly et al. Citation2013). While these tools are useful, we should consider other evidence-based techniques that can be imbedded in our workplaces to complement self-care strategies (Yeung, et al., Citation2017).

A useful technique for assessing how well-balanced your current life is a “Wellness Wheel” which allows you to reflect on different aspects of your life. Alternatively there are on-line assessment tools such as PROqol which investigates professional quality of life for to people with careers in the helping professions, and can be accessed through the AVMA website (https://www.avma.org/ProfessionalDevelopment/PeerAndWellness/Pages/assess-your-wellness.aspx).

Veterinary associations, including those in New Zealand and Australia, have recognised the need for support networks for veterinarians and provided free counselling sessions (https://www.nzva.org.nz/professionals/wellbeing-resources/; https://www.ava.com.au/member-services/vethealth/). Members of the NZVA can also access a useful toolkit of resources for self-care including courses and webinars on well-being, stress, resilience and workplace culture. https://www.nzva.org.nz/professionals/wbhub/. There is also growth in more informal peer support groups such as The Riptide Project which focus on peer support and mentoring within the veterinary profession (https://www.theriptideproject.com/).

The veterinary profession, both veterinarians and veterinary nurses, need to be more open to adopting strategies used by our human medical counterparts. Tools to develop resilience in the profession may contribute to a stronger, mentally healthier workforce.

Conclusions

The veterinary profession needs a more mature approach to its handling of clinical errors, including recognition of their multifactorial causes. As a profession, as employers and as supervisors, we need to move away from the “blame and shame” model of response to clinical errors. As individuals we need to accept our fallibility, strive to learn compassionately from our own mistakes, but also build our own resilience to the effects of making clinical errors. Organisational and professional communication tools can be implemented in workplaces to create a culture of safe disclosure, and discussion and reflection techniques promoting resilience. A system for reporting clinical errors across the veterinary profession would allow us to identify and correct common errors, but there are significant cultural and logistical hurdles to implementing such a system. Perhaps the easiest place to start is by beginning to talk about our own mistakes.

References

- Athanasakis E. A meta-synthesis of how registered nurses make sense of their lived experiences of medication errors. Journal of Clinical Nursing 28, 3077–3095, 2019

- *Donaldson MS, Corrigan JM, Kohn LT. To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press, Washington, DC, USA, 2000

- Gardner DH, Hini D. Work-related stress in the veterinary profession in New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 54, 119–24, 2006

- Goh RLZ. To err is human: an ACEM trainee’s perspective on clinical error. Emergency Medicine Australasia 31, 665–6, 2019

- Holcombe TM, Strand EB, Nugent WR, Ng ZY. Veterinary social work: practice within veterinary settings. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment 26, 69–80, 2016

- Jha AK, Larizgoitia I, Audera-Lopez C, Prasopa-Plaizier N, Waters H, Bates DW. The global burden of unsafe medical care: analytic modelling of observational studies. BMJ Quality and Safety 22, 809–15, 2013

- Mazor KM, Fischer MA, Haley HL, Hatem D, Quirk ME. Teaching and medical errors: primary care preceptors’ views. Medical Education 39, 982–90, 2005

- Moses L, Malowney MJ, Wesley Boyd J. Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: a survey of North American veterinarians. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 32, 2115–22, 2018

- O’Sullivan ED, Schofield JS. Cognitive bias clinical medicine. Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh 48, 225–32, 2018

- Oxtoby C, Mossop L. Blame and shame in the veterinary profession: barriers and facilitators to reporting significant events. Veterinary Record 184, 501, 2019

- Petronio S, Torke A, Bosslet G, Isenberg S, Wocial L, Helft PR. Disclosing medical mistakes: a communication management plan for physicians. The Permanente journal 17, 73–9, 2013

- Reason J. Human error: models and management. British Medical Journal 320, 768–70, 2000

- Sanchez-Reilly S, Morrison LJ, Carey E, Bernacki R, O’Neill L, Kapo J, Periyakoil VS, deLima Thomas J. Caring for oneself to care for others: physicians and their self-care. Journal of Supportive Oncology 11, 75–81, 2013

- Wallis J, Fletcher D, Bentley A, Ludders J. Medical errors cause harm in veterinary hospitals. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 6, 12, 2019

- Waters A. Depression and the importance of hope. Veterinary Record 184, 457, 2019

- Weller J, Boyd M, Cumin D. Teams, tribes and patient safety: overcoming barriers to effective teamwork in healthcare. Postgraduate Medical Journal 90, 149–54, 2014

- Wu AW. Medical error: the second victim. British Medical Journal 320, 726–7, 2000

- Yeung P, White B, Chilvers BL. Exploring wellness of wildlife carers in New Zealand: a descriptive study. Anthrozoös 30, 549–63, 2017

- * Non-peer-reviewed.