Abstract

A sample of 219 bird bones, from the Late Neolithic levels at Tell Sabi Abyad, located in the Balikh Valley, Northern Syria, was analysed. These remains informed about the ecological setting of the site, showing it to be permanently occupied, rather than used only seasonally. The practice of fowling at Tell Sabi Abyad was investigated, and both the economic and cultural importance of the birds through time is discussed. The recovery of avifaunal remains from certain phases of occupation, along with their low quantities or absence in others, might reflect changes in subsistence taking place at Tell Sabi Abyad around 6300 BC. This small, but important, sample of bird bones adds to the limited published data available on the avifauna of the Late Neolithic of Northern Syria.

Introduction

Information about the avifauna present in the Balikh Valley in the Late Neolithic is very limited. The number of avian bones recovered from archaeological sites in the Near East is highly variable due to differences in both excavation methods and preservation. The quantity of bird bones found is usually very small in comparison with mammal bones, even when very accurate excavation methods are used (Gál Citation2006: 50). The scarcity of large avian bone assemblages published, may, in part, be due to this lack of excavated material. Another issue that could limit the reporting of bird bone assemblages is access to a good reference collection to identify the avifauna. Nevertheless, bird remains can provide us with valuable information. Birds were used in antiquity for food, tools, feathers, as well as for their symbolic significance (Serjeantson Citation2009).

In addition to the information that can be garnered regarding human exploitation of birds in antiquity, bird remains are increasingly used to obtain information about the environmental setting of the archaeological site where they were found. The varying ecological requirements of the different species can provide information about the environment close to the site at the time of deposition (Ericson Citation1987). In order to make an ecological reconstruction based on ancient bird remains, one must assume that the niche of modern birds is the same as their predecessors. This assumption is supported by palaeontological data and it is, therefore, possible to infer relatively safe conclusions about past environments based on the avifauna present (Gál Citation2006: 51).

Syria lies on one of the most important migration routes in the world; seeing millions of birds migrating between Europe and Africa every autumn and spring (Baumgart Citation1995; Porter et al. Citation1996). The presence of certain avifauna can potentially, therefore, be used to study seasonality. The results of research into the avifauna present in the Late Neolithic levels at the site of Tell Sabi Abyad, Northern Syria, are presented in this paper: this is one of only a few studies undertaken on avian bones from this period and region. The avifauna of the Balikh are of interest because they can, potentially, tell us much about both past environments and the role these animals played in culture and economy.

The site and its environment

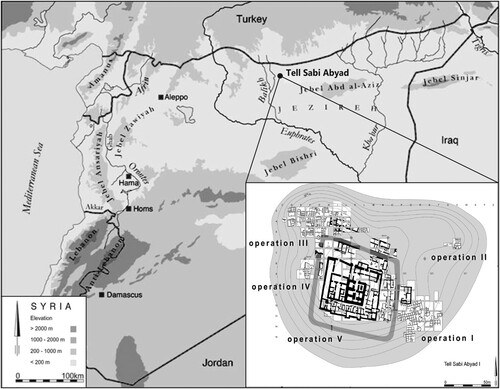

The site of Tell Sabi Abyad is situated in the Balikh Valley in Northern Syria, approximately 30 km from the Syro-Turkish border and about 2 km south of the modern village of Hammam et-Turkman (). The site is part of a cluster of mounds, locally known as Khirbet Sabi Abyad, dating back to the 7th and 6th millennium BC. It is the excavation of the largest of these mounds, known as Tell Sabi Abyad I (henceforth Tell Sabi Abyad) and more specifically, an area on the north-western part of this mound known as Operation III (), which provided the bird bones for this study. Excavations in this section began in 1988 and ended in 2011 following the abrupt onset of war in Syria. Large areas have been exposed and excavated, often to some metres in depth. These carefully excavated areas have produced some of the most comprehensive data sets in Syria, giving an insight into life there during the Late Neolithic.

Figure 1 Site location, with detail of the operations in mound Tell Sabi Abyad I (adapted from Nieuwenhuyse et al. Citation2015: 55, 57).

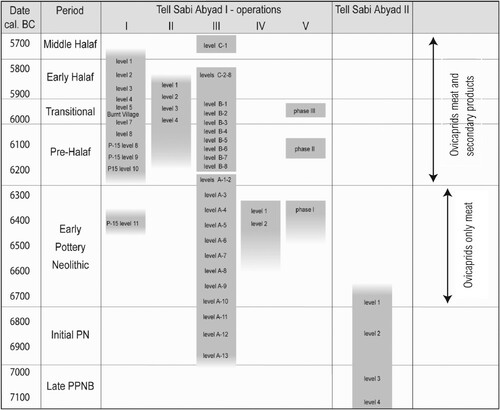

The site represents a continuous sequence of permanent settlement, consisting of a small number of family units, totalling perhaps only a few dozen people (Akkermans et al. Citation2006). The size of the site today is somewhat misleading, as only small areas, of a few hectares, were ever occupied at any one time. The location of the settlement shifted through time, the result of a very small-scale form of local mobility, building up the large mound seen today. There are, broadly speaking, three periods of tell formation. These are known as tell ‘A’ (c. 7000–6200 BC), ‘B’ (6200–5900 BC) and ‘C’ (Halaf c. 5900–5700 BC). Within these periods 22 levels of occupation were identified ().

Figure 2 The chronology of Tell Sabi Abyad I and Tell Sabi Abyad II, showing culture-historical terminology and absolute dates cal. BC (adapted from Nieuwenhuyse et al. Citation2010: 78).

The site is located in an area known as the Jazirah, a relatively flat area of semi-arid steppe, bounded by the Euphrates and Tigris rivers to the west and east respectively, and the Asia Minor mountains to the north (Akkermans and Schwartz Citation2003; Wilkinson Citation1990). Meandering through this area is the Balikh River, a small stream bordered by gravel terraces and Holocene deposits of brown fluviale-aeolithic loams (Boerma Citation1988; Copeland Citation1979; Mulders Citation1969: 54; van Zeist Citation1988). Today the site sits between the 300 mm and 200 mm isohyets (the limit of dry farming), making the area rather marginal for dry farming, and crop failures are quite common (Beaumont Citation1996; Wilkinson Citation1990; Citation1998; van Zeist Citation1988). The Balikh Valley is characterized by low annual precipitation; summers are generally very dry and hot, and winters relatively cool, with the rainy season lasting from the end of October until April (de Moulins Citation1997: 9; Mulders Citation1969: 96; Wilkinson Citation1990). The area is located in the Irano-Turanian phytogeographic zone and is dominated by large open areas of xeromorphic dwarf shrub-land and desert steppe, with some river valley vegetation such as poplar, willow and tamarix (Bocherens et al. Citation2005; Mulders Citation1969: 96; van Zeist and Bottema Citation1991: 32).

Modern distribution of birds in the Balikh Valley

Up until the late 20th century the riverine landscape consisted of a complex web of canals, river beds and marshes, the Balikh receiving water from the springs of ‘Ain al-Arous and Sabi Abyad (Wilkinson Citation1998). Excessive modern day demands for irrigation water have resulted in drastically lowered water tables and the modest flow of the Balikh has become almost entirely dry (Wilkinson Citation1998). There were extensive areas of marsh in the lower reaches of the Balikh until fairly recently, when they were drained and the water diverted into irrigation canals. Only 70 years ago Mallowan (Citation1946) describes the abundance of wild fowl and other animals in these marshes, giving a glimpse of what must, potentially, have been a rich hunting ground in the Neolithic. The ornithology of the area today is relatively unknown (Gourichon Citation2004: 133). The oldest descriptions of birds in the Near East were recorded by travellers, explorers and traders of past decades, but this was well before the advent of the scientific discipline of ornithology we know today (Gourichon Citation2004: 133). Some information about breeding and wintering birds in the area was gathered during the 1960s and 1970s, but Syria did not receive the same attention as its neighbours Turkey, Israel and Jordan (Gourichon Citation2004: 133).

Syria has a rich avifauna due to its diverse environments and its location between three continents, Africa, Asia and Europe. It is an important region in the migration routes of numerous Palaearctic avifauna, with birds migrating to Africa in the autumn and back to their breeding grounds in the spring. The decimation of natural habitats by man and the unchecked hunting of many species has led to a reduction in the number of bird species seen today. Wintering species in the 1970s and early 1980s included a diversity of waterfowl, such as the greater white-fronted goose (Anser albifrons) and the common crane (Grus grus). Ducks were reported to be present in both in the summer and winter months, with many water birds migrating over the area in the autumn. Until the 1970s the great bustard Otis tarda, was a resident of the area (BirdLife Citation2020).

Material and methods

The osteological analysis of the avian bones from Tell Sabi Abyad

The avian bone material analysed in this study came from excavations undertaken between 2003–2007. All the material was hand-collected, no sieving was undertaken at the time of excavation. All the faunal material was stored in museum boxes at the Museum of Antiquities, Raqqa, Syria until 2008, when the avifauna were sorted out from the rest of the material and brought back to the University of Leiden, The Netherlands, for identification. The osteological analysis was carried out with the help of the reference collection in the Zooarchaeology Department of the Faculty of Archaeology, University of Leiden, the reference collection in the Zooarchaeological Institute, the State University of Groningen and the museum collections of avifauna at the Naturalis Museum, Leiden.

Bones were identified, where possible, to skeletal element and species, genus or family. Skeletal elements that could not be identified to species include phalanges, vertebrae and ribs. The NISP (number of fragments identified to species) was calculated for each species by level and context.

Results

Bird species from Tell Sabi Abyad

A total of 219 bird bones or fragments were analysed, 166 (75.8%) could be identified as a specific skeletal element and 79 (36.1%) could be identified to species or genus ( and ). Sixteen different taxa were identified, 63.5% of the fragments could only be identified as ‘aves’.

Table 1 NISP by broad period

Table 2 Skeletal Element NISP by species

Out of the 14 species or genus of bird identified, the most common was columba livia (Rock Dove) — 19.2% of the assemblage. The high proportion of this species is due to the presence of two bone concentrations, most likely representing two articulated carcasses. The second most common species was the great bustard, of which there were nine bone fragments — 4.1% of the assemblage. Many species were represented by a single bone fragment.

It is important to note that the presence of some identified species may be questionable, or unusual for the time period. The grey partridge (Perdix perdix) has not been observed in Syria during the two last centuries, though it was present at the end of the Pleistocene at Mureybet (Pichon Citation1984), in the Middle Euphrates Valley. Another unexpected identification is that of a gull (Larus sp.), since it is unlikely that it would travel so far inland. This might indicate that the Balikh was a relatively large river during the Late Neolithic.

Temporal changes

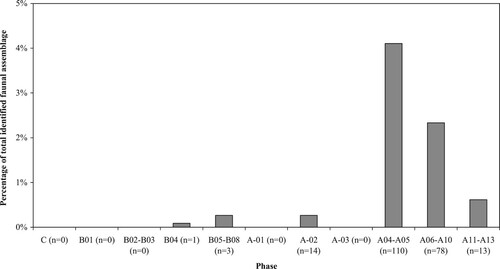

No avifauna were recovered from the ‘C’ Levels and only in the ‘A’ Levels were avifauna present to any degree (), even then they made up only a very small percentage of the total faunal remains. The stratigraphic levels were grouped into phases based on the trends seen in the faunal assemblage (Russell Citation2010), the total percentage of avifauna was calculated for each of these phases ().

Two things are clear: that avifauna represent a very low percentage of the total number of identified faunal remains recorded; and that their importance changed through time. Birds are most prominent in the oldest levels, reaching a peak of 4.1% in phase A04–A05 before almost entirely disappearing from the assemblage.

Element representation

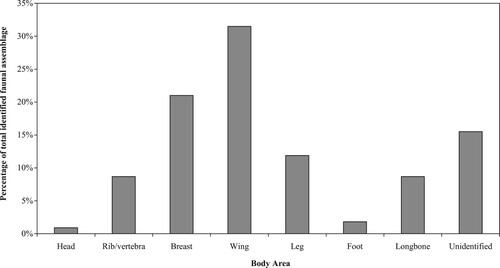

All elements of the avian skeleton were recognized in the Tell Sabi Abyad material. The most common elements were the sternum, ulna, radius and humerus (). When grouped into general body parts it is evident that wing elements are, by far, the most common, followed by breast elements (). Breast elements may have been selected for their meat, as has been recorded at other sites in the Near East (Tchernov Citation1994). Wing elements have less meat and may, therefore, have been selected for other reasons (see discussion below). It should be noted that wing long bones and breast bones are more common in the bird skeleton than leg bones.

Modifications

Cut marks were seen on only two bone fragments, both from the great bustard. These consisted of fine cut marks on a tarsometatarsus and a tibiotarsus. Gnawing was present on just one unidentified bird humerus, the culprit being a rodent. Signs of burning were noticeable on five bone fragments including one Anser species ulna, an unidentified bird coracoid, two unidentified bird bone fragments and one unidentified bird long bone that was burnt at such a high temperature that it was calcined.

Discussion

Taphonomy

Interpretation of the avifaunal assemblage must include consideration of the processes that could have affected the deposition and preservation of the bones (Livingston Citation1989). The low abundance of avian remains may not accurately reflect their actual contribution to the prehistoric diet, but may, instead, reflect the method of excavation (no sieving was undertaken which perhaps led to the under-representation of smaller birds) and the vulnerability of bird bones to taphonomic effects (Higgins Citation1999). Although relatively few bird bones were recovered from the site, 84.6% were recorded as having good levels of surface preservation, this, plus the recovery of some of the smallest bird bones, suggests that in general bird bone preservation was good. Far more wings than legs are present in the avifaunal sample, this could, in part, be due to the differential preservation of these elements (Higgins Citation1999; Livingston Citation1989). Legs have considerably more available meat than wings, which might result in the selection of these elements for food, resulting in these fragments being subjected to higher levels of breakage.

Fowling

The processes by which bird remains become incorporated into archaeological deposits can be more complicated than for fish and mammals; as many birds can fly this extends the number of ways in which they can be incorporated into a context (Serjeantson Citation1997). As such, it is more difficult to determine those present through natural causes and those present through anthropogenic activity. This is particularly relevant when discussing how important birds were to the economy and culture of a past settlement, but less so when discussing the palaeoenvironment; the presence of certain bird species can be very informative with regard to nearby habitats, regardless of whether humans or natural causes brought them to the site. Long distance exchange cannot be ruled out, but there is no direct evidence of this at Tell Sabi Abyad.

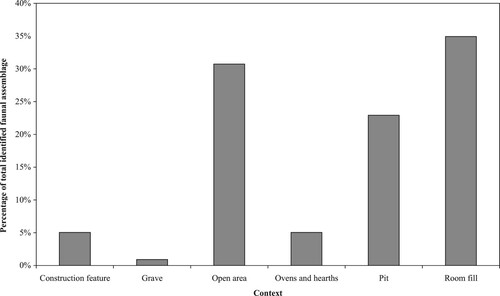

A researcher can only be entirely sure that bird bones have derived from human activity when the bones have been butchered, burnt, or otherwise handled in a way that could only have been done by man (Ericson Citation1987). Whether or not a bone is naturally or culturally deposited remains a qualitative decision and is, therefore, subjective (Thomas Citation1971). With the exception of the two associated bone clusters of rock dove, it is assumed that all the avifauna in this analysis were present as a result of human activities, for example hunting and trapping for food or other products, such as feathers. Given that the majority of avian bones were found in contexts within cultural layers with rich artefact assemblages and features, such as pits and hearths, this is probably a safe assumption (). It is possible, however, that some of the bird remains were brought onto the site in the clay collected to make mudbricks, or, that they were hunted by domestic cats and dogs resident at the site. The human utilization of birds at Tell Sabi Abyad is indicated through cutmarks, traces of burning, and the use of bird bones to make objects such as beads and needles (Akkermans et al. Citation2006).

If bird bone finds are abundant in contexts in which other food remains have been discarded, it can be assumed that these birds were used as a food source (Serjeantson Citation1997: 256). Whether or not wild birds were an important food source, depends on the availability of other food sources. In the case of Tell Sabi Abyad, with its well-established herds of domestic sheep and goat, as well as cattle and pigs, birds did not form an important part of the subsistence economy. It has been hypothesized that observing many more leg elements than wing elements is a sign that birds were used for food (Higgins Citation1999: 1455). This is not the case at Tell Sabi Abyad where wing elements outnumber all other body parts. Elements from around the breast area were, however, relatively common and may suggest a preference for meat from this muscular area. The burned and butchered bones suggest that at least the great bustard and Anser species were eaten, although all bird species found at the site could have been used for food.

The number of bird bones at Tell Sabi Abyad suggests that fowling was not widely practiced in any level, particularly not in the ‘C’ and ‘B’ Levels. This is not surprising considering the increasing reliance on domestic mammals at the site. While faunal assemblages at Tell Sabi Abyad are dominated by domestic caprines prior to 6300 BC, the following Pre-Halaf period is characterized by a reliance on sheep and goat for secondary products in addition to meat (Nieuwenhuyse et al. Citation2010; Russell Citation2010). This change seems to coincide with a decline in avifauna exploitation at Tell Sabi Abyad. If birds were already only occasionally hunted during earlier occupation levels, a shift in diet towards an increased reliance on domestic mammals and related secondary products would have reduced overall hunting activities, and thereby occasional fowling further. This may also be related to a more general change in human-animal relations during the Neolithic, and, in particular, notions about the symbolic or nutritional value of birds (which are further addressed below). In other words, the decline in hunting activities during the Halaf period seems to be correlated with reduced fowling, which may, in turn, have had implications for the perception of birds.

Environment

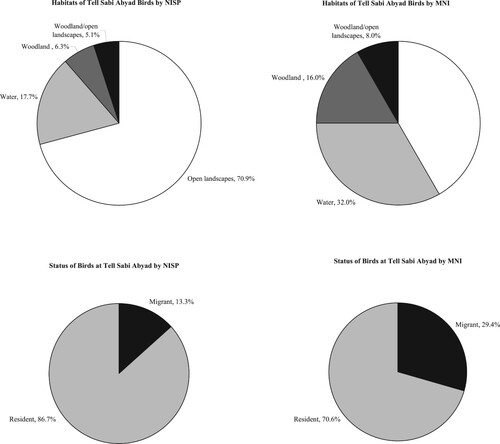

The potential for using bird bone evidence for reconstructing the environment around a site can be as useful, if not more useful, than other sources of environmental evidence (Serjeantson Citation1997: 258). An analysis of the known habitats of modern versions of the species identified three broad habitat types: open steppe, woodland and water (). The predominant environment around the site in the Late Neolithic was, apparently, one of large open areas of steppe, with some water (the Balikh River) and woodland (riverine forest) within a reasonable distance from the site. This conclusion is mirrored in analyses of the palaeobotanical material at the site (van Zeist and Waterbolk-van Rooijen Citation1989; Citation1996).

Seasonality

The majority of the remains were derived from bird species resident in the Balikh all year round, with only 13.3% of the bird bone fragments coming from migrant species. This suggests that local birds were exploited throughout the year with migrant birds being exploited when they were in the area, though season fowling cannot be excluded. There is no evidence that the site was abandoned at any time of the year.

Culture

Both the utilitarian and symbolic significance of birds to the people of the Late Neolithic must be considered. Ethnographic studies have shown that birds have almost always had a symbolic role among human societies (Dirrigl et al. Citation2020; Serjeantson Citation1997). All over the world people have used feathers for decoration, display and social signalling. Birds might have been considered special because of the pleasure that can be derived from their song, colour and ability to fly, while their appearance in myths and legends suggests they also enjoyed a spiritual importance in many cultures (Dirrigl et al. Citation2020 and references therein; Gál Citation2006; Serjeantson Citation1997). At Çatalhöyük it has been hypothesized that crane wings were used in ritual dances (Russell and McGowan Citation2003), and evidence from several Epipalaeolithic sites in the Levant points to the use of raptors’ wings and feathers for ornamental or ceremonial purposes (Martin et al. Citation2013; Yeomans and Richter Citation2018). There is no direct evidence of similar activities taking place at Tell Sabi Abyad, although wing elements are the most common parts of birds present at the site. Wing feathers could also have been used in the fletching of arrows, which appear to have been in use, at least in the 6th millennium BC, given the depictions of hunting with arrows on pottery from this period (Bréniquet Citation1992; Nieuwenhuyse Citation2007: 20). There is some evidence for the cultural significance of birds, with birds depicted on painted sherds of pottery first appearing in the Late Neolithic (). Interestingly, these images appear at a time when the physical remains have almost completely disappeared from the assemblage.

Figure 7 Late Neolithic painted pottery fragment from Tell Sabi Abyad Operation III showing a design with birds represented.

One can only speculate about the nature of the relationship between the decline in avifauna, increase in the reliance on domesticates and the presence of bird depictions on pottery sherds during the Late Neolithic at Tell Sabi Abyad. Could a change in subsistence have affected human interaction with birds during this period? Whether one sees domestication as a process driven by human intention or as more of a symbiosis, the impact it had on the animal-human relationship is undeniable (Marciniak Citation2005; Russell Citation2011). The increasing reliance on animal husbandry and the exploitation of secondary products during the Neolithic resulted in a higher energy efficiency of animal products (Greenfield Citation2005; Sherratt Citation1981; Vigne and Helmer Citation2007). The pattern seen at Tell Sabi Abyad suggests that this might be correlated to a reduced consumption of avifauna, which may be linked to a change in the perception of birds by the inhabitants of the site during this period.

Site comparisons

Comparative data from Late Neolithic sites in Northern Syria are very scarce. Only six sites had comparative data available: Tell Sabi Abyad Operation I (Cavallo Citation2000), Tell Sabi Abyad Operation II (Wijngaarden-Bakker and Maliepaard Citation2000), Bouqras (Buitenhuis Citation1988), Dja’de el-Mughara, Qdeir I and El Kown 2 (Gourichon Citation2004). Many of the species recorded in this study were also present at the comparative sites (). The large number of species recovered from Dja’de el-Mughara is probably due to the earlier date of the layers from which bird remains were retrieved (EPPNB) and the systematic use of sieving at this site. That some of the species found at Tell Sabi Abyad I, Tell Sabi Abyad II and Bouqras were not found in this study is probably due to taphonomic bias, selection bias, or a combination of these two factors, rather than any true environmental differences, but with such small samples available it is difficult to say.

Table 3 Site comparisons (species in bold are also present in this study)

Conclusions

Wild birds have been exploited throughout human history, by hunter-gatherers as well as sedentary farming communities, but have usually been a relatively unimportant source of food compared to medium/large mammals (Serjeantson Citation1997). The analysis of the avifauna at Tell Sabi Abyad shows that birds were exploited at very low levels in the Late Neolithic period. They were hunted from the desert steppe surrounding the site and in the nearby riverine forest and waters of the Balikh River. Cut marks and evidence of burning, together with the presence of bird bones in ovens and features containing other food remains, suggest that the birds were eaten.

Birds were only retrieved from the oldest levels at the site and disappear from the faunal assemblage from Level A03 onwards. The increasing reliance on domestic mammals and derived secondary products may have reduced the need for meat from small game, and perhaps even changed notions about birds. This small but important data set, adds to the limited knowledge available about the avifauna of the Late Neolithic of Northern Syria, and their economic and possible symbolic importance. Further analysis of bird bone assemblages from Neolithic sites in this region are needed in order to determine the relationship between changing lifestyles, the reliance on domesticates and the exploitation of local avifauna.

Acknowlegements

The authors would like to thank the Zooarchaeological Institutes at Leiden University, the State University of Groningen and the Naturalis Museum for the use of their reference collections.

References

- Akkermans, P. M. M. G. and Schwartz, G. M. 2003. The Archaeology of Syria: from Complex Hunter-gatherers to Early Urban Societies (c. 16,000–300 BC). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Akkermans, P. M. M. G., Cappers, R., Cavallo, C., Nieuwenhuyse, O., Nilhamn, B. and Otte, I. N. 2006. Investigating the early pottery Neolithic of northern Syria: new evidence of Tell Sabi Abyad. Americal Journal of Archaeology 110: 123–56.

- Baumgart, W. 1995. Die Vögel Syriens: eine Ubersicht. Heidelberg: Max Kasparek verlag.

- Baumgart, W. 1995. Die Vögel Syriens: eine Übersicht. Heidelberg: Max Kasparek verlag.

- Beaumont, P. 1996. Agricultural and environmental changes in the upper Euphrates and catchment of Turkey and Syria and their political and economic implications. Applied Geography 16(2): 137–57.

- BirdLife International. 2020. BirdLife’s World Bird Database: The Site for Bird Conservation. Version 2.1 Cambridge, UK: BirdLife International [online]. Available at: http://www.birdlife.org [accessed 6th July 2020].

- Bocherens, H., Mashkour, M., Drucker, D. G., Moussa, I. and Billiou, D. 2005. Stable isotope evidence for palaeodiets in southern Turkmenistan during historical period and Iron Age. Journal of Archaeological Science 33(2): 253–64.

- Boerma, J. A. K. 1988. Soils and environment of tell Hammam et-Turkman. In, Van Loon, M. N. (ed.), Hamman et-Turkman I: Report on the University of Amsterdam’s 1981–1984 Excavations in Syria: 1–11. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

- Bréniquet, C. 1992. À propos du vase halafian de la Tombe G2 de Tell Arpachiyah. Iraq 54: 69–78.

- Buitenhuis, H. 1988. Archaezoölogisch Onderzoek Langs de Midden-Eufraat. PhD. Rijksuniversiteit Groningen.

- Cavallo, C. 2000. Animals in the Steppe: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Later Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad, Syria. BAR International Series 891. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Copeland, L. 1979. Observations on the prehistory of the Balikh Valley, Syria, during the 7th to 4th millennium BC. Paléorient 5: 251–75.

- Dirrigl, F. J., Brush, T., Morales-Muñiz, A., Bartosiewicz, L. 2020. Prehistoric and historical insights in avian zooarchaeology, taphonomy and ancient bird use. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 12(57): 1–8.

- Ericson, P. G. P. 1987. Interpretations of archaeological bird remains: a taphonomic approach. Journal of Archaeological Science 14: 65–75.

- Gál, E. 2006. The role of archaeo-ornithology in environment and animal history studies. In, Jerem, E., Mester, Z. and Benczes, R. (eds), Archaeological and Cultural Heritage Preservation within the Light of New Technologies: Selected Papers from the Joint Archaeolingua-EPOCH Workshop: 49–61. Budapest: Archaeolingua.

- Gourichon, L. 2004. Faune et Saisonnalité: L’organisation temporelle des activités de subsistance dans L’Epipaléolithique et le Néolithique précéramique du Levanr nord (Syrie). PhD. University of Lyon.

- Greenfield, H. J. 2005. A reconsideration of the Secondary Products Revolution in south-eastern Europe: on the origins and use of domestic animals for milk, wool and traction in the central Balkans. In, Mulville, J. and Outram, A. K. (eds), The Zooarchaeology of Fats, Oils, Milk and Dairying: 14–31. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Higgins, J. 1999. Túnel: a case study of avian zooarchaeology and taphonomy. Journal of Archaeological Science 26: 1449–57.

- Livingston, S. D. 1989. The taphonomic interpretation of avian skeletal part frequencies. Journal of Archaeological Science 16: 537–47.

- Mallowan, M. 1946. Excavations in the Balikh Valley, 1938. Iraq 8: 11–159.

- Marciniak, A. 2005. Placing Animals in the Neolithic: Social Zooarchaeology of Prehistoric Farming Communities. London: UCL Press.

- Martin, L., Edwards, Y. and Garrard, A. 2013. Broad spectrum or specialised activity? Birds and tortoises at the Epipalaeolithic site of Wadi Jilat 22 in the eastern Jordan steppe. Antiquity 87: 649–65.

- de Moulins, D. 1997. Agricultural Changes at Euphrates and Steppe Sites in the Mid-8th to 6th Millennium BC. BAR International Series 683. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Mulders, M. A. 1969. The Arid Soils of the Balikh Basin (Syria). PhD. Rijksuniversiteit te Utrecht.

- Nieuwenhuyse, O. P. 2007. Plain and Painted Pottery. Brepols: Turnhout.

- Nieuwenhuyse, O. P., Akkermans, P. M. M. G., Van der Plicht, J. 2010. Not so coarse, nor always plain. The earliest pottery of Syria. Antiquity 84: 71–85.

- Nieuwenhuyse, O. P., Roffet-Salque, M., Evershed, R. P., Akkermans, P. M. M. G. and Russell, A. 2015. Tracing pottery use and the emergence of secondary product exploitation through lipid residue analysis at Late Neolithic Tell Sabi Abyad (Syria). Journal of Archaeological Science 64: 54–66.

- Pichon, J. 1984. L’avifaune natoufienne du Levant. Université Pierre et Marie Curie (Paris VI): Thèse de 3ème Cycle.

- Porter, R. F., Christensen, S. and Schiermacker-Hansen, P. 1996. Field Guide to the Birds of the Middle East. London: T. and D. Poyser.

- Russell, A. 2010. Retracing the Steppes: A Zooarchaeological Analysis of Changing Subsistence Patterns in the Late Neolithic at Tell Sabi Abyad, Northern Syria, c. 6900 to 5900 BC. PhD. Leiden University.

- Russell, N. 2011. Social Zooarchaeology: Humans and Animals in Prehistory. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Russell, N. and McGowan, K. J. 2003. Dance of the cranes: crane symbolism at Çatalhöyük and beyond. Antiquity 77(297): 445–55.

- Serjeantson, D. 1997. Subsistence and symbol: the interpretation of bird remains in archaeology. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 7: 255–59.

- Serjeantson, D. 2009. Birds. Cambridge Manuals in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sherratt, A. G. 1981. Plough and pastoralism: aspects of the secondary products revolution. In, Hodder, I., Issac, G. and Hammond, N. (eds), Patterns of the Past: Studies in Honour of David Clarke: 261–305. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tchernov, E. 1994. An Early Neolithic Village in the Jordan Valley, Part II: The Fauna of Netiv Hagdud. American School of Prehistoric Research Bulletin 44. Harvard University: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology.

- Thomas, D. H. 1971. On distinguishing natural from cultural bone in archaeological sites. American Antiquity 36(3): 366–71.

- Wijngaarden-Bakker, L. H. and Maliepaard, R. 2000. The animal remains. In, Verhoeven, M. and Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (eds), Tell Sabi Abyad II: The Pre-Pottery Neolithic B Settlement: 147–71. Istanbul: Netherlands Historich-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

- Wilkinson, T. J. 1990. Soil development and early land use in the Jazira region, upper Mesopotamia. World Archaeology 22(1): 87–103.

- Wilkinson, T. J. 1998. Water and human settlement in the Balikh Valley, Syria: investigations from 1992–1995. Journal of Field Archaeology 25(1): 63–87.

- Yeomans, L. and Richter, T. 2018. Exploitation of a seasonal resource: bird hunting during the Late Natufian at Shubayqa 1. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 28(2): 95–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/oa.2533.

- van Zeist, W. 1988. Some notes on the plant husbandry of Tell Hammam et-Turkman. In, Van Loon, M. N. (ed.), Hamman et-Turkman I: Report on the University of Amsterdam’s 1981–1984 Excavations in Syria: 705–15. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

- van Zeist, W. and Bottema, S. 1991. Late Quaternary Vegetation of the Near East. Wiesbaden: Reichert.

- van Zeist, W. and Waterbolk-van Rooijen, W. 1989. Plant Remains from Tell Sabi Abyad. Excavations at Tell Sabi Abyad Operation I. BAR International Series 468: 325–35. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- van Zeist, W. and Waterbolk-van Rooijen, W. 1996. The cultivated and wild plants. In, Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (ed.), Tell Sabi Abyad: The Late Neolithic Settlement: 521–41. Istanbul: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

- Vigne, J.-D. and Helmer, D. 2007. Was milk a ‘secondary product’ in the Old World Neolithisation process? Its role in the domestication of cattle, sheep and goats. Anthropozoologica 42(2): 9–40.