Abstract

The transition between the Early Bronze Age IV and the Middle Bronze Age in the southern Levant remains poorly understood, stemming in part from traditional approaches to the problems that frame it in terms of exogenous cultural origins and disjuncture versus indigenous growth and continuity of development. However, the growing range of diversity of data relating to both eras increasingly mitigates against such monocausal interpretations. Instead, assessment and analysis of different strands of evidence such as settlement patterns, subsistence practices and mortuary traditions, together with accompanying physical material culture, indicate that the transition between eras in the southern Levant was a complex and variable process that included considerable inter-regional variation, and incorporated both external influence and internal developments.

Introduction

Analysis of the transition from the Early Bronze Age IV (EB IV) to the Middle Bronze Age (MBA) has suffered from frequent shifts in perspective, differences in academic approach, and a constantly changing and dynamic body of evidence. To date, no consensus exists for the nomenclature for either of these two eras, nor on the chronological dates in which to place them, while ongoing excavation continues to provide ever more archaeological data that require categorization into typological sequences and contextualization within historical and archaeological interpretations. The more complex, varied and numerous these data become, the more difficult it is to find a single interpretation and methodological approach that successfully accounts for all of them, and depending on the evidence discussed, the scholarly view of this transition varies considerably. The result of this lack of terminological, chronological, archaeological and analytical consensus is that the transition between these eras, and, by extension, the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age, remains poorly understood and subject to near-constant reassessment.

The perennial debate between exogenous influence or indigenous development as the prime mover for the beginning of the MBA further compounds the problem, as the historical scholarly tendency to grant causal primacy to the one or the other has resulted in monocausal interpretations and overarching explanations for the start of the era. While these increasingly have proved to be inadequate to account for the complex archaeological remains found in the southern Levant, many current analyses of the beginning of the MBA may still be found pitting indigenous progress against exogenous stimulus, and vice versa (e.g., Burke Citation2014; Citation2021; Homsher and Cradic Citation2017; for a welcome exception to this bifurcated approach, see Greenberg Citation2019: 188–207). By contrast, most recent studies of the EB IV have, instead, called for consideration of multi-variant approaches (e.g., D’Andrea Citation2018; Kennedy Citation2015; Citation2016; and most recently, see the collections of essays in Richard Citation2020; and Dever and Long Citation2021). Acknowledging the increasing complexity of data that mitigate against single explanatory understandings, these studies provide contemporary interpretations of EB IV that allow for regional variation and diversity in development.

The difficulty of finding a holistic explanation for the EB IV–MBA transition and subsequent start of the Middle Bronze Age that works at all levels and that incorporates all available evidence, suggests that perhaps there ought not to be one, especially given the clear regionalism increasingly apparent in both eras. Consequently, universal and sweeping explanations applied indiscriminately across the entire southern Levant, whether they rely on wholly exogenous factors such as ‘Amorites’ (e.g., Burke Citation2021), or focus on predominantly indigenous developments as explanatory prime movers (e.g., Homsher and Cradic Citation2017) should be avoided. Instead, the transition between the EB IV and the MBA in the southern Levant may best be addressed by acknowledgement of the range of regional variation, together with the corresponding complexity of evidence, and the multiple trajectories of development, interactions and interconnections suggested by significantly diverse data. Assessment of multiple strands of evidence for both the EB IV and the MBA, ranging from such basics as terminology, to the more complex and complicated issues of structural organization and physical remains, given that these are expressed differently in different regions, may then lead to a greater understanding of both the transition and the forces that influenced it.

Terminology

At present, there is no scholarly consensus for the nomenclature for either the final phase of the Early Bronze Age, or the first phase of the Middle Bronze Age; competing terms for both eras exist. This situation results from the historical development of the archaeological study of both eras, as initial terminological choices were largely based on the observable degree of continuity, or lack thereof, in the ceramic sequence at specific sites, an approach that from the outset indelibly linked nomenclature with perspectives of transition. The ensuing terminological muddle thus represented the outward manifestation of an inward lack of consensus regarding the development of the southern Levant from the end of EB III until the later phases of the Middle Bronze Age.

For example, Albright’s analysis of surface material from Bab edh Dhra led him to first identify an ‘EB IV’ for the material after Early Bronze Age III; however, he also suggested ‘MB I’ for similar material from excavations at Tell Beit Mirsim. In both cases, he then used ‘MB IIA’ to indicate the beginning of the following cultural era (Albright Citation1933; Citation1938; Citation1966). By contrast, following her excavations at Jericho (1960), Kenyon adopted ‘Intermediate’ to reflect her interpretation of the post-EB III material found there, and used ‘MB I’ for the beginning of the following era.

Continued excavation provided increased numbers of types and forms of ceramics, leading to additional permutations in the uses and applications of ‘EB IV’ and ‘MB I’ as scholars sought to identify the eras they represented and the relationships between them (see discussion in Cohen Citation2002: 11; and Gerstenblith Citation1983: 2–3, table 1) (). These efforts resulted in the use of variations of both ‘EB IV’ and ‘MB I’ for the earlier period, including a combination of the two as ‘EB IV/MB I’, followed, variously, by either ‘MB I’ or ‘MB IIA’ for the ensuing era (see discussion in Dever Citation1973). More recently, analysis has included not only examination of ceramic development, but also issues of stratigraphic sequences, occupational continuity and other concerns (see, e.g., D’Andrea Citation2014a; Citation2020; Citation2021; Falconer and Fall Citation2021: 187–89; Kennedy Citation2015; Citation2020, among others), bringing a greater degree of analytical sophistication to this problem. While many of these studies now prefer ‘EB IV’ for the earlier era, followed by ‘MB I’, a complete terminological consensus has yet to be established. At present, therefore, different nomenclature remains in contemporary use for both the earlier period — ‘EB IV’ (frequently subdivided), ‘Intermediate’, and ‘MB I’ — as well as the beginning of the next — ‘MB I’ and ‘MB IIA’ (see ).

Table 1 Overview of historic terminology and nomenclature and showing the sequences in contemporary usage

The goal here is not to argue for or against a specific terminological sequence, or reiterate detailed arguments supporting one or the other, but rather to outline this historical development of the nomenclature for these eras, as that provides explanatory context for the current situation and its plethora of competing terminologies. This paper uses Early Bronze IV (EB IV), followed by Middle Bronze I (MB I), and Middle Bronze II/III (MB II/III). The former terminology acknowledges that most recent studies of the earlier era prefer EB IV, while use of MB I for the first phase of the Middle Bronze Age then logically begins the following period with the numeral I rather than II.

Chronology

In addition to the problem of what to call each era, the equally significant and ongoing debate that hinders examination of the EB IV–MB I transition revolves around the question of when it took place. The higher end date for EB III established by the ‘New Chronology’ results in a span of at least half a millennium, from c. 2500–2000 BCE, for the EB IV (Regev et al. Citation2012), rather than a shorter span of c. 350 years, as understood by earlier scholarship. This broad range may be further subdivided into two, creating an early and later phase for EB IV (D’Andrea Citation2018: 83), with the break between the two sub-periods roughly at 2300 BCE. While it is the date of the end of the era and, correspondingly, the beginning of MB I, that is of relevance here, the greater length of the EB IV holds ramifications for its development and character that subsequently affects examination of the transition to MB I.

While most EB IV studies conventionally end the era at 2000 BCE, this is not universally accepted as the beginning date for MB I. Instead, disagreement regarding the start of the Middle Bronze Age involves three competing sets of chronologies: 1) the older traditional and conventional date of c. 2000 BCE (e.g., Dever Citation1992; 2) the low chronology provided by the excavations at Tell ed-Daba, which begins the MB I at c. 1900 BCE (e.g., Bietak Citation2013); and 3) the dates provided by recent radiocarbon data that place the transition between 2000/1950 BCE (Höflmayer Citation2017). Depending on the choice of chronological schema, therefore, the beginning of the MB I may vary by up to a century.

This study uses the radiocarbon-backed dates of 2000/1950 BCE for the beginning of MB I. As well as being results of the most recent analyses and bolstered by scientific data, these dates provide flexibility in chronological scope, such that the MB I begins over the course of half a century. Such a chronological range represents what have been called ‘sloping horizons’ (D’Andrea Citation2014a: 33; Nigro Citation2003: 139) between eras. Rather than applying a single date across an entire geographic area, sloping chronological horizons acknowledge that different parts of the southern Levant — and elsewhere — developed differently, in keeping with the variable nature of transition itself.

Transition

As noted in the introduction, most analyses of the EB IV/MB I transition, as well as of the subsequent rise of Middle Bronze Age urban culture, tend to grant causal primacy to either exogenous influence or indigenous development (see overviews in Buck Citation2020: 31–48; Cohen Citation2002: 14–16; D’Andrea Citation2014a: 278–79). Most frequently referencing directionality from the northern Levant, exogenous explanation has looked to such varied causes as population movements encompassing invasion, infiltration, immigration and refugees (e.g., Burke Citation2021; Kenyon Citation1966), or alternatively, more oblique means such as cultural diffusion and trade (e.g., Gerstenblith Citation1983). By contrast, the indigenous approach emphasizes local trajectories of development for everything from settlement patterns and urbanism (e.g., Falconer Citation1994) to more amorphous concepts of social and political organization and interactions (e.g., Ilan Citation1998). Regardless of specific approach, whether presented as any of the various iterations of the ‘Amorite Hypothesis’ or as identification of ‘trait lists’ of local developments, examination of the beginning of Middle Bronze Age society in the southern Levant tends to fall behind one perspective or the other (e.g., Burke Citation2014; Homsher and Cradic Citation2017), with the historically earlier exogenous approach and accompanying views of greater discontinuity largely more common, especially in more general works (e.g., Burke Citation2014; Dever Citation1987; Mazar Citation1990). Indeed, the suggestion that Middle Bronze Age southern Levantine society derived from purely exogenous influence, based on a repackaged concept of Amorite movements in the ancient Near East, is currently making a renewed comeback (e.g., Burke Citation2021).

Nonetheless, by definition transition is change, and change, by definition, is mutable and unfixed. Tracking transition, therefore, is to follow developments that are in flux, and thus manifest in different ways, and may appear differently in individual areas and regions at different times, in keeping with the perspective of ‘sloping horizons’ cited above. Archaeologically, this may include, variously, recognition of antecedents of material culture in previous eras, or in other regions, together with the appearance and/or disappearance of new forms and styles, means and methods of transmission, the identification of stratigraphic shifts in occupation, or evidence for the establishment of new social and economic practices or systems.

These archaeological data that inform transition may be divided into two categories: 1) those that reveal shifts in systemic social or economic organization and structure; and 2) those regarding changes and developments in the physical material culture used in those systems. The former includes patterns of settlement and occupation, subsistence practices and evidence for diet and consumption of both food and drink, and mortuary customs, while material remains, such as ceramics and architecture, comprise the latter category. Examination of these different categories of data from each era, both systemic and material, allows for assessment and analysis of the scope, nature and character of the EB IV–MB I transition in the southern Levant.

Spatial structure: settlement and occupation

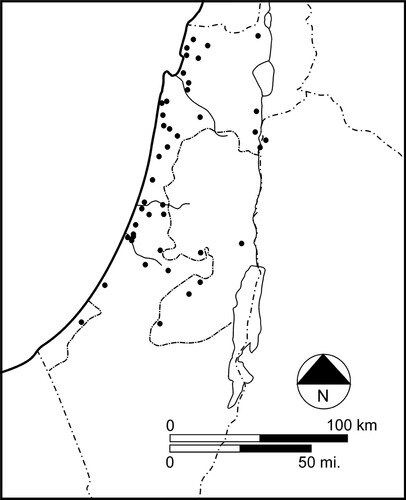

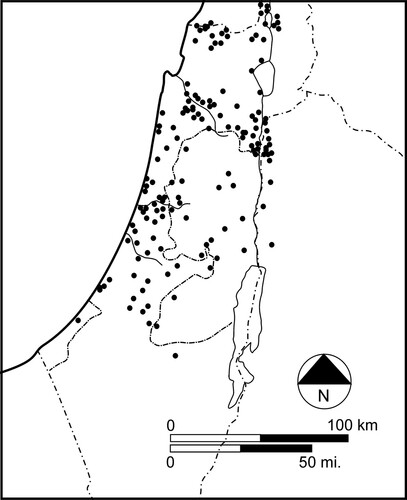

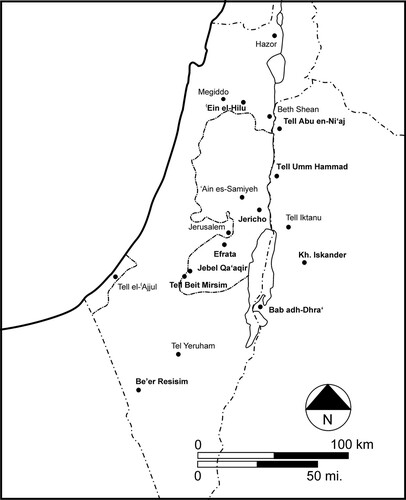

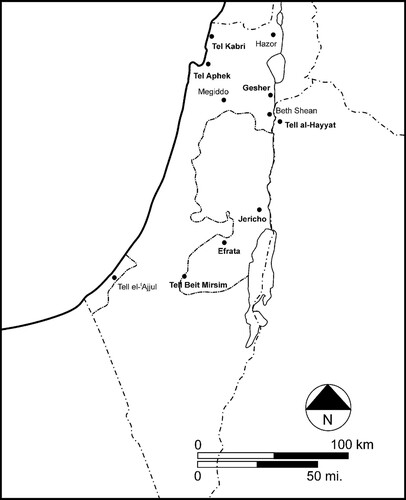

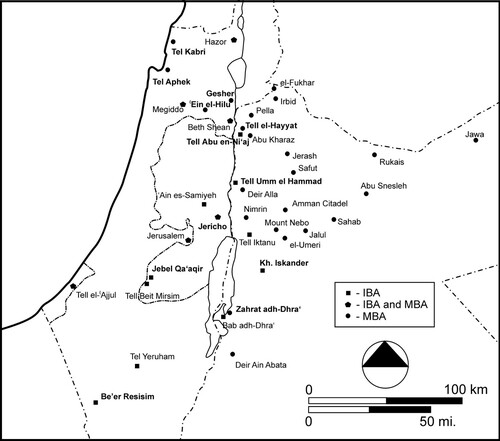

An initial examination of settlement patterns suggests disjunction between eras; simply put, few sites exhibit occupational continuity between EB IV and MB I. Further, the primary areas of settlement in both eras are located in different regions. Although EB IV occupation has been identified throughout the southern Levant, the greatest concentrations of settlement exist in the central and northern Jordan Valley, and are characterized by smaller, rural sites () (D’Andrea Citation2014a: fig. 1; MacDonald Citation2021: fig. 17.1). By contrast, distinctive Middle Bronze Age settlement is most notable on the coastal plain, in the north, and along east–west transportation routes; these locations also have higher numbers of large, urban and fortified sites () (Cohen Citation2002).

Figure 1 Map of EB IV settlement in the southern Levant, with sites mentioned in the text marked in bold. Map by W. Więckowski.

Figure 2b Map of MB I settlement in the southern Levant, with sites mentioned in the text marked in bold. Map by W. Więckowski.

This visual disconnect is even more striking in the more marginal areas of the southern Levant, such as the Dead Sea Plain and the Negev. In the former, sites occupied in EB IV were abandoned at the end of the era (for recent discussions of EB IV settlement see Falconer and Fall Citation2021; MacDonald Citation2021) and not occupied in MB I, and while there is significant settlement in the northern Negev in EB IV, settlement in those regions is conspicuously absent in the Middle Bronze Age, although it should be noted that the general sparsity of material culture and generic nature of the material found there makes precise chronological identification difficult. Pollen data suggest that climate may have influenced changes in settlement patterns in these regions. Broadly speaking, the EB IV experienced moderate conditions, MB I had a considerably drier climate, while the following MB II/III was comparably wetter (Langgut et al. Citation2014: 297, table 3). This situation may support and help explain the lack of MB I settlement in these marginal areas: regions that were habitable under moderate climatic conditions would be the first affected adversely by a drier climate.

Overall, however, even outside the more environmentally marginal regions, the spatial distribution of sites in EB IV and MB I point to different, and contrasting, patterns of settlement. Further, for MB I, these patterns also create the impression that certain regions in the southern Levant were largely ‘empty’ during early phases of the era (Cohen Citation2002: figs 12–13, 16–17). Thus, the lack of occupational continuity, different regional settlement concentration and highly different patterns of development, all suggest significant disjunction between EB IV and MB I.

Closer examination, however, fuelled by data provided from continued excavation and survey, clearly shows that regions in southern Palestine and Transjordan that originally appeared ‘empty’ in the early MB I were not, in fact, devoid of settlement in the Middle Bronze Age () (Bourke Citation2014: 465, fig. 31.1; Cohen Citation2016: 82, fig. 6.7; Greenberg Citation2019: 188–90; Maeir Citation2010: 136–39, figs 58–59). Notably, these areas exhibit a dense occupational pattern composed predominately of smaller, rural sites. When this more up-to-date spatial distribution of MB I settlement is juxtaposed against current knowledge of EB IV settlement, and settlement from both eras is viewed together (), the regional continuity between EB IV and MB I in the central and northern Jordan Valley stands out clearly. Further, it has long been noted that social and economic organization in these areas in EB IV and MB I is largely indistinguishable (Cohen Citation2009; Citation2015; D’Andrea Citation2014b; Citation2021; Falconer and Fall Citation2006; Greenberg Citation2002: 105; Citation2019: 189; Maeir Citation2010). Overall, the character of settlement in these regions differs from that seen along the coast and major east–west transportation routes, where earlier EB IV settlement is sparser, and show stronger external and northern orientation.

Figure 4 Map showing both EB IV and MB I sites in the inland regions of the southern Levant. Map by W. Więckowski.

Fundamentally, the apparent disconnect in settlement between EB IV and MB I is neither simple nor as clear-cut as may be perceived initially. Instead, current data reveal two different but contemporaneous spatial patterns in MB I in the southern Levant: 1) inland settlement in the Jordan Valley made up predominately of a dense network of smaller sites that indicates regional occupational continuity; and 2) a more discontinuous and externally oriented northern and coastal settlement that developed along east–west trajectories, which includes a higher number of larger, and often fortified, centres. Other data from these different but contemporary spatial patterns, ranging from economic and social structure to material culture, also reflect elements of both continuity and disjuncture between EB IV and MB I.

Economic structure: consumption and subsistence

Consumption of both food and drink, as seen archaeologically in faunal and floral remains, reflects underlying subsistence strategies, adaptations to change (e.g., economic, social, environmental, etc.), as well as regional economic patterns. Comparison of available floral and faunal data from EB IV and MB I sites thus informs regarding economic structural organization in both eras, as well as during the transition between them.

Early Bronze Age IV

Data from EB IV sites throughout the southern Levant indicate that subsistence strategies differed regionally (Cohen Citation2019; Citation2021). While the inhabitants of all southern Levantine sites relied on a mixture of animal husbandry and various agricultural practices for their sustenance and subsistence, variations in focus and organization between them also stemmed from geographic location and accompanying economic and environmental concerns. For example, higher numbers of pigs and cattle are attested at sites in the upper Jordan Valley, such as Ein el-Hilu (Covello-Paran Citation2009), and Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj (Fall et al. Citation1998), whereas remains from both these animals are less frequent at Khirbet Iskander (Metzger Citation2010: 143), further south and east on the Transjordanian plateau, while faunal remains from Be’er Resisim, located considerably further south and in far more marginal environmental circumstances, included little to no pig or cattle remains at all (Hakker-Orion Citation2014: 312–13). Evidence further indicates that gazelle, rabbit or bird, that would have been hunted in the surrounding areas, augmented subsistence at Beer Resisim, while taxa from wild game were infrequent at sites in the more sedentary regions.

Published data on floral remains from the EB IV are few. Those from Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj in the Jordan Valley indicate a predominance of barley, supplemented by regular use of other cereal crops, legumes and orchard crops, such as olive, grape and fig (Falconer and Magness-Gardiner Citation1989: table 3, and see page 341; Fall et al. Citation1998: 118–19). Again, as with the faunal remains, this contrasts sharply with the evidence — although quite limited — from Be’er Resisim, where the inhabitants appear to have practiced no systemic agriculture and may have partially relied on small quantities of locally growing flora for subsistence (Danin Citation2014). Unfortunately, there is insufficient floral data from a larger number of EB IV sites to provide further analysis. While remains of grinding installations and mortars at Ein el-Hilu (Covello-Paran Citation2009: 11) and various groundstone implements from occupational contexts at Khirbet Iskander (Forsen and Rowan Citation2010) may indicate the importance of grain preparation, these provide no information regarding the type of grains or cereals ingested by the sites’ inhabitants, or the subsistence strategies behind their production.

Middle Bronze Age I

Faunal evidence from MB I sites indicates little difference in basic animal husbandry strategies from those practiced during the EB IV. All sites, regardless of their location, whether in the inland areas that exhibit regional continuity in occupation, or situated in the more disjunctive externally-oriented settlement patterns that developed along the coast, relied on caprine herding, with additional focus on cattle and pigs, as demonstrated by the faunal remains from sites such as Tell el-Hayyat in the Jordan Valley (Fall and Metzger Citation2006: 73), and Tel Kabri and Tel Aphek in the coastal settlement regions (Hellwing Citation2000: 312–13; Horwitz and Mienis Citation2002: 400; Marom Citation2020: 297).

As with the earlier era, however, the variations in subsistence patterns that do exist appear linked to environmental conditions found in the different geographic regions, rather than to any change between eras (Cohen Citation2021), a development most visible in the frequency of pig remains. For example, at Kabri, faunal evidence indicates some exploitation of pig, both wild and domestic, for meat, a phenomenon directly attributed to specific conditions at the site (Horwitz and Mienis Citation2002: 400). Notably, pig is less frequent than other taxa in the remains associated with the palace, although it is likely that the faunal remains found in the palace are not representative of the overall faunal corpus, and hence associated subsistence strategies, of the general population of the site (cf. Marom Citation2020: 297).

At Aphek, located further south and slightly more inland, pig is considerably less well represented in the faunal data, likely because the surrounding region is far less suitable for the animal (Hellwing Citation2000: 312–13). By contrast, faunal remains from the intermittent agrarian settlement Zahrat adh-Dhra’1, located further south in the environmentally marginal Dead Sea region, included almost no pig or domestic taxa other than caprine, reflecting occupational patterns in keeping with the site’s geographic location (Fall et al. Citation2019: 7), much like the environmentally marginal Be’er Resisim in the EB IV.

As with the EB IV, floral data for MB I also are extremely limited, hampering analysis of subsistence practices and diet based on agricultural and horticultural practices. Floral assemblages from the MB I phases at Tell el-Hayyat include cereals, orchard fruits, legumes and wild species, thus suggesting activities associated with a sedentary village with an agrarian subsistence base (Fall and Metzger Citation2006; Fall et al. Citation1998: 116). These data are largely the same as those at the nearly EB IV village site of Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj, and appear to reflect similar subsistence strategies, and accordingly, the inhabitants’ diet and consumption practices (Falconer and Magness-Gardner Citation1989: 340; Fall et al. Citation1998: 116). Only in the later Middle Bronze Age phases at Tell el-Hayyat do the floral remains show a shift in emphasis from barley to wheat, suggesting shifts in economic strategies (Fall and Metzger Citation2006: 72; Fall et al. Citation1998: 120).

The floral data from Zahrat adh-Dhra’1 likewise included cereals, legumes and some fruit crops. The range of cultigens is, however, considerably smaller, and they occur in lower frequencies than those recorded at Tell el-Hayyat. By contrast, the number of wild taxa from Zahrat adh-Dhra’1 is nearly double that found at the Jordan Valley site (Fall et al. Citation2019: 11–14), analogous to the practices of consuming wild flora noted in the EB IV at Be’er Resisim.

Comparison – economic structure

Faunal remains from EB IV and MB I occupational strata reveal little major difference in the subsistence patterns, animal economies and subsequent diet based on animal remains, indicating the continuation of common subsistence strategies between eras. Likewise, comparison between floral remains and the subsistence practices they likely represent, reveal more similarities than differences between the EB IV and early MB I phases. The most visible variation — differences in relative frequencies of pigs and consumption of wild taxa, both faunal and floral — are better attributed to regional factors, such as geographical location and accompanying environmental suitability (e.g., materials from Beer Resisim and Zahrat adh-Dhra’1 in the EB IV and MB I, respectively), and associated patterns of occupation and settlement, rather than chronological era; regarding subsistence as it informs the EB IV–MBA transition, the available data indicate evidence for considerable continuity in economic structure and organization. In fact, in terms of subsistence patterns and underlying economic structure, both faunal and floral evidence indicate greater difference in production and subsistence in the later phases of the Middle Bronze Age (MB II/III) than those observed between the EB IV and MB I (Cohen Citation2021).

Social structure: mortuary traditions

Burial practices, encompassing both placement of the deceased and the objects interred with them, reflect beliefs held by the living population. Food and drink offerings found with the dead provide evidence concerning belief and custom, and serve as an indication of social patterns, as do the traditions of the so-called ‘warrior burials’. Comparison of these data from both EB IV and MBA mortuary sites, as with subsistence patterns, informs concerning social structure in both eras and the nature of transition between them.

Food offerings

Food offerings found in mortuary contexts represent deposits either made by the living in the process of commemorating the dead (e.g., feasting) or provided by the living for consumption by or use by the dead (to eat as food or use as offerings in post-mortem ritual). In either case, food offerings represent (idealized) practices of consumption that reflect accompanying beliefs and/or social customs of the living population. Significantly, the practice of providing food offerings — of similar type and style — crosses the chronological boundaries between the EB IV and MB I. Found in all regions throughout the southern Levant in both eras, in graves associated with both large and small sites, the practice of interring the deceased with food speaks to a common belief held by the communities of the living that buried the dead, and a common belief likewise implies continuity of population and accompanying social organization. Data from faunal deposits (sheep and/or goat) found with the dead in both eras, from sites such as Jebel Qa’aqir (Horwitz Citation2014: 246), Jericho (Grosvenor Ellis and Westley Citation1965: 701), Gesher (Horwitz Citation2007: 128–29), and Efrata (Horwitz Citation2001: 116), indicate that what differences existed may be better linked to the social and economic organization of the living population that buried the dead, rather than to the chronological era in which they lived (see discussion in Cohen Citation2021); the ubiquity of the offering itself, as just noted, reflects a similar commonality of underlying belief.

Drinking

In contrast to food offerings in mortuary contexts, contemporaneous evidence for drinking customs associated with the dead exhibit considerable change between eras, as well as marked external influence. Based on the appearance of cups and teapots in the ceramic assemblages, Bunimovitz and Greenberg (Citation2004; Citation2006) argued for a shift from communal feasting in the EB III to drinking in the EB IV in the southern Levant, resulting from elite emulation of northern customs. Later assessment by Kennedy (Citation2020) pushed this argument further, suggesting that ruralized settlement, together with accompanying changes in drinking customs in EB IV, reflect a shift back to greater emphasis on the individual, a reaction to the communalism that resulted from the agglomeration of population in EB III. Finally, additional re-examination of this topic on a broader pan-Levantine scale by Vacca and D’Andrea (Citation2020) led them to suggest that traditions of both feasting and drinking in the EB III and EB IV southern Levant were influenced by north–south directions of interaction, with the Orontes Valley acting as a ‘crossroads of exchange’ (Citation2020: 139) for the transmission of different cultural information.

Regardless of the specific details of interpretation, this highly visible and distinctive change in drinking practices reveals significant social transformation between the EB III and the EB IV, expressed through modifications in the material culture associated with them. Therefore, by logical extension, if the appearance of material objects such as cups and teapots in the EB IV are the physical results of social change between EB III and the EB IV, the disappearance of these same objects in MB I, must, likewise, indicate another social and/or structural change between EB IV and MB I (see discussion in Cohen Citation2021: 21). This is not to suggest that drinking disappeared during MB I, but rather, that the specific practices and/or social customs associated with drinking may have changed, and that this social shift is made visible by the accompanying changes in material culture. It is then tempting to suggest that the type of beverage itself also shifted between eras, in keeping with changes in the social practices associated with the act of drinking, resulting in a different set of associated material culture — perhaps suggested by the bone beverage strainers found in the MB I cemetery at Gesher (Maeir Citation2007; see also Cohen Citation2021) — but insufficient data exists at this time to evaluate this hypothesis in further detail.

‘Warrior burials’

In addition to offerings of food and drink, offerings with the dead, the so-called ‘warrior burials’ (see Kletter and Levy Citation2016 for recent discussion of, and challenge to, this term) — interments of male individuals with weaponry — may inform regarding the transition between eras. Found throughout the ancient Near East from the EBA through MB I, the very longevity and geographic range of the practice speaks to continuity, not only between eras, but also to connectivity between the southern Levant and other regions across the ancient Near Eastern world (Garfinkel Citation2001; Garfinkel and Cohen Citation2007), perhaps even reaching as far as southern Arabia (e.g., Hausleiter et al. Citation2018).

Burials with weaponry are found in all regions and in different urban and rural settings throughout the southern Levant — again providing a level of continuity and cultural continuum that crosses urban and rural boundaries, as well as regional ones. While changes in weapon typology reflect northern influences, the mix in metallurgic composition of the weapons themselves also suggests elements of local development (Cohen Citation2009: 7–8, and see discussion in Cohen Citation2012). Further, as with subsistence and diet, greater differences in interment practices involving weaponry are found between EB IV and MB II/III, than between EB IV and MB I, as the frequency, use and placement of weapons, as well as their metallurgical composition, changes more significantly in the later eras (Cohen Citation2012).

Comparison – mortuary practices

Remains from mortuary contexts from both EB IV and MBA burials suggest elements of both continuity and disjuncture, as well as indigenous development and external influences. The ‘warrior burials’, together with the general practice of interment of the human body with deposits related to food and drink, provide clear indications of continuity of belief; differences in the food offerings with the dead — as with food for the living — may be more properly linked to economic circumstances rather than chronological era. By contrast, drinking practices — or at least the items associated with drinking that inform knowledge of those practices — exhibit greater disjuncture between eras, as well as evidence for northern, external influences (e.g., Bunimovitz and Greenberg Citation2004; Citation2006; Vacca and D’Andrea Citation2020).

Physical material culture

Observable changes in material culture are commonly used to identify transition. However, while typological differences in material culture provide the physical evidence for change, shifts in type, form, decoration, composition, or appearance and/or disappearance of material culture more properly represent the visible manifestation of change. In many cases, it may be argued that actual structural or systemic transformation itself — whether social, economic, or political — takes place prior to the observable material and tangible adaptations to it. A brief examination of two categories of the highly visible material culture typically associated with the Middle Bronze Age — ceramics and fortifications — serve to further illustrate this point and inform concerning the transition between EB IV and MB I.

Ceramics

The distinctiveness of both EB IV and Middle Bronze Age ceramics is well-known. In their fully developed forms, the differences between these two corpora are readily apparent on multiple levels, such as manufacturing technique, surface treatment and decoration, and form. As a full analysis of both EB IV and early MB I ceramics is beyond the scope of this article (for detailed treatments of both EB IV and MB I ceramic corpora, see, respectively: D’Andrea Citation2014a; Citation2014b; Citation2020; and Ilan and Marcus Citation2019), only a few observations that relate directly to the transition between eras are presented here.

Many recent works have provided close analysis of EB IV ceramics with attention to both local regional development and northern connections (D’Andrea Citation2012; Citation2014a; Citation2018; Citation2020; Kennedy Citation2015; Citation2020; Richard Citation2020; Vacca and D’Andrea Citation2020). For the MB I, an initial establishment of four basic phases of ceramic development based on the pottery sequence found at Tel Aphek (Beck Citation2000a; Citation2000b; Citation2000c) served to provide a broad outline of ceramic development for the period (see Cohen Citation2002). More recent comprehensive analysis of Middle Bronze Age ceramics from the southern Levant provides clear discussion of the significant features of these materials and note that Middle Bronze Age ceramics exhibit a ‘substantial departure’ from those of the preceding era, citing differences in production, form and appearance (Ilan and Marcus Citation2019: 9–10).

However, while much of the MB I ceramic corpus indeed suggests clear discontinuity and shows few — if any — similarities with earlier EB IV pottery, some of the ceramics from those same regions that show occupational continuation, such as the northern and central Jordan Valley (see and ), do exhibit different patterns. Ceramics transitional in both shape and form, as well as in decorative elements, are attested from EB IV sites such as Tell Umm Hammad (Kennedy Citation2015: passim and fig. 4) and Khirbet Iskander (Richard Citation2010), as well as MBA sites like the the Gesher cemetery (Cohen Citation2009: 5; Cohen and Bonfil Citation2007) and the earliest occupational phases (Phase 5) at Tell el-Hayyat (Falconer and Fall Citation2006: fig. 4.2), all of which suggests continuity in ceramic material culture between EB IV and the MBA. At the same time, both EB IV and MB I ceramics also exhibit external, northern influences (e.g., Cohen and Bonfil Citation2007: 97–99; Kennedy Citation2020; Richard Citation2010). Increasingly, ongoing analysis points to broader regional and pan-Levantine connections between eras (see discussions on north–south interconnectivity in D’Andrea Citation2020; and Vacca and D’Andrea Citation2020), and overall, the ceramic corpus of the early MB I evinces the same admixture of continuity and discontinuity, internal and external development, expressed regionally, as suggested by the settlement patterns.

Fortifications

Monumental fortifications stand out as perhaps the most visible feature of the Middle Bronze Age in the southern Levant (Burke Citation2008; Citation2021; Dever Citation1987). While fortified EB IV sites are attested, such as Khirbet Iskander and Tall Hamman, among others (MacDonald Citation2021), the scope, size and overall character of the Middle Bronze Age fortifications set them apart and alters the landscape significantly between the EB IV and the Middle Bronze Age. Serving as unequivocal evidence for external influence on the development of the Middle Bronze Age, these structures provide perhaps the clearest visual expression of disjuncture and change between eras, reflecting not only physical material change, but likely also significant social and political change whereby the peoples of the MB I southern Levant saw the need to create such constructions (for interpretations of the social and political function of fortifications, ranging from physical defence to expressions of social power, see Bunimovitz Citation1992; Burke Citation2008).

Such highly visible markers as monumental architecture also illustrate the relationship between systemic change and the physical evidence of change. Monumental constructions require certain preconditions for building them: sufficient population to do the work, requisite social and/or political structure to oversee or organize their construction, sufficient capital (to apply a modern term to ancient economies), ample resources and the necessary knowledge of engineering/physics (again to use modern terms) to construct them. In short, fortifications, even if they seem simply to appear on the landscape, practically speaking, cannot in fact do so. Although it has been proposed that a workforce derived from corveé labour would have allowed fortifications to be completed in a span of 1–5-year projects (Burke Citation2008: 152), this suggestion assumes a set population, along with numerous other social and political prerequisites not necessarily universally applicable across the southern Levantine landscape, and timeframe of construction may have varied. Rather than a single sweeping imposition on the landscape, these structures may better be understood within their individual geographic location, and social and cultural milieu (Homsher and Cradic Citation2017: 274), and which, as noted throughout, includes regional variation.

Discussion — physical material culture

As with settlement and subsistence, the physical material culture briefly discussed here — ceramics and fortifications — reflects regional variability and evidence for both internal development and external influences in the early MB I. The strongest evidence for ceramic continuity appears in the same regions that exhibit occupational continuity (e.g., the northern and central Jordan Valley) (see and ), while the ceramic corpus that suggests the most difference predominates in those areas with more visible breaks in settlement patterns (e.g., coastal regions, urban centres on major transportation routes). In both cases, significant evidence for external northern influence exists (e.g., Ilan and Marcus Citation2019; Kennedy Citation2020; Vacca and D’Andrea Citation2020). Likewise, the fortifications of the Middle Bronze Age clearly exhibit external influences in form, and suggest significant disjuncture or restructuring in political concerns and social and economic organization throughout the EB IV–MB I transition. As the visible results of the economic and social restructuring that preceded them, and which progressed differently throughout various parts of the southern Levant, these may also indicate some degree of regionalism.

Summary and conclusions

The regionalism of the EB IV is well-known, and all current evidence to date reinforces this perspective (e.g., Cohen Citation2019; D’Andrea Citation2014a; Citation2018; Kennedy Citation2015; Citation2016; Citation2020; Prag Citation2014; and see the collections of essays in Richard Citation2020; and Dever and Long Citation2021). It follows, therefore, that the beginning of the next era, together with the evidence that reveals it, is also highly differentiated. The more complex the EB IV is revealed to be, the equally complicated continues to be the understanding of the transition to the MB I.

In part, the continued debate regarding the beginning of the Middle Bronze Age as either exogenous or indigenous, stems from adherence to previous intellectual constructs that focused predominantly on one or the other. When current data — with all their variability — are considered, as outlined above, it is clearly no longer possible to assign the beginnings of an era to individual causal explanations, as they do not adequately represent the complexity of the material. This variability of evidence then hampers, if not precludes outright, the adherence to monocausal interpretations of fully exogenous or indigenous development, as this creates a false dichotomy that can no longer be considered an effective approach to understanding this transition. It cannot be claimed that there was little to no external direction provided by people and/or ideas from the northern Levant (e.g., Homsher and Cradic Citation2017: 276) — such an assertion disregards the clear northern antecedents of different aspects of Middle Bronze Age culture. However, the contention that MB I arose solely from external influence (e.g., Burke Citation2021: 233, 359) is equally patently false and simplistic, as that ignores the clear evidence that shows continuity from the EB IV.

Instead, flexibility and variability in the transition from the EB IV to MB I is apparent in all categories of data, ranging from social and economic structural organization to physical material culture. Subsistence strategies, and the diet resulting from them, maintain considerable continuity across temporal boundaries while exhibiting greater intra-regional variation based on geography, environment and local economic considerations. Settlement pattern and organization at the beginning of MB I in inland regions retained elements of continuity with the preceding era, whereas the coastal areas exhibited greater disjuncture; these patterns are reflected in the ceramic corpus. Likewise, burial patterns exhibit a mix of both continuity and cultural change, with the former seen in commonality of the so-called ‘warrior burials’ together with the basic practice of interment of both the human body and the accompanying material culture, of providing food, and the associated belief(s) accompanying these actions, while the decline of such distinctive ceramic forms as cups and teapots along with accompanying changes in drinking practices, illustrate the latter. Finally, the appearance of the monumental architecture of the Middle Bronze Age presents what is perhaps one of the most visible aspects of discontinuity between eras and evidence of external influence, whether via population movement or more removed cultural connectivity and transmission, as the preconditions necessary for the construction of that architecture, as discussed above, clearly suggest significant social and economic change or restructuring.

Examination of the diversity of evidence regarding organization and physical material culture leads to the following observations regarding the transition between EB IV and MB I in the southern Levant: 1) not all categories of data exhibit significant change between eras; 2) some of the most striking differences follow along regional and economic lines rather than temporal divisions between eras; 3) like that observed for EB IV, early Middle Bronze Age development exhibits distinctly different regional patterns, drawing on both indigenous and exogenous forces for development; and 4) some of the greatest distinctions are found between EB IV and MB II/III rather than EB IV and MB I.

These observations illustrate the complexity of the EB IV–MB I transition, as well as contribute to general knowledge of the nature of archaeological transition. Rarely completely clear-cut, transitions follow individualized and flexible pathways, along sloping chronological lines, and draw on multiple lines of influence and development, with final resultant change — what may be identifiable as a new ‘era’ — only fully realized or unambiguously visible after the fact. Analysis of the transition between the EB IV and the Middle Bronze Age in the southern Levant and the materials used to assess it must recognize the variability and regionalism, elements of continuity and discontinuity, and numerous trajectories of development that exist, and the multiplicity of reasons for them. This diversity of data shows that MB I culture derived both from internal continuity with the EB IV as well as from external influences, and developed regionally along different lines over a span of time. It was not until the later MB II that a more pan-regional homogenization and standardization in settlement, organization and material culture developed, creating the highly visible and classic Middle Bronze Age II/III culture of the southern Levant.

References

- Albright, W. F. 1933. The Excavations of Tel Beit Mirsim IA: The Bronze Age Pottery of the Fourth Campaign. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 13. New Haven, CT: ASOR.

- Albright, W. F. 1938. The Excavations of Tel Beit Mirsim II: The Bronze Age. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 17. New Haven, CT: ASOR.

- Albright, W. F. 1966. Remarks on the chronology of Early Bronze IV–Middle Bronze IIA in Phoenicia and Syria-Palestine. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 184: 26–35.

- Beck, P. 2000a. Area B: pottery. In, Kochavi, M., Beck, P. and Yadin, Y. (eds), Aphek-Antipatris I. Excavation of Areas A and B. The 1972–1976 Seasons: 93–133. Monograph Series No. 19. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Beck, P. 2000b. Area A: Middle Bronze Age IIA pottery. In, Kochavi, M., Beck, P. and Yadin, Y. (eds), Aphek-Antipatris I. Excavation of Areas A and B. The 1972–1976 Seasons: 173–238. Monograph Series No. 19. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Beck, P. 2000c. The Middle Bronze Age IIA pottery repertoire: a comparative study. In, Kochavi, M., Beck, P and Yadin, Y. (eds), Aphek-Antipatris I. Excavation of Areas A and B. The 1972–1976 Seasons: 239–54. Monograph Series No. 19. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Bietak, M. 2013. Antagonisms in historical and radiocarbon chronology. In, Shortland, A. and Bronk-Ramsay, C. (eds), Radiocarbon and the Chronologies of Ancient Egypt: 79–109. Oxford: Oxbow.

- Bourke, S. 2014. The southern Levant (Transjordan) during the Middle Bronze Age. In, Steiner, M. L. and Killebrew, A. E. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant, c. 8000–332 BCE: 465–81. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Buck, M. 2020. The Amorite Dynasty of Ugarit. Historical Implications of Linguistic and Archaeological Parallels. Leiden: Brill.

- Bunimovitz, S. 1992. Middle Bronze Age fortifications in Palestine as a social phenomenon. Tel Aviv 19: 221–33.

- Bunimovitz, S. and Greenberg, R. 2004. Revealed in their cups: Syrian drinking customs in Intermediate Bronze Age Canaan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 334: 19–31.

- Bunimovitz, S. and Greenberg, R. 2006. Of pots and paradigms: interpreting the Intermediate Bronze Age in Israel/Palestine. In, Gitin, S., Wright, J. and Dessel, J. P. (eds), Confronting the Past. Archaeological and Historical Essays on Ancient Israel in Honor of William G. Dever: 23–31. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Burke, A. 2008. ‘Walled up to Heaven’. The Evolution of Middle Bronze Age Fortification Strategies in the Levant. Harvard Semitic Museum Publications. Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant 4. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Burke, A. 2014. Introduction to the southern Levant during the Middle Bronze Age. In, Steiner, M. and Killebrew, A. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant c. 8000–332 BCE: 403–13. Oxford: Oxford University.

- Burke, A. 2021. The Amorites and the Bronze Age Near East. The Making of a Regional Identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohen, S. 2002. Canaanites, Chronology, and Connections: The Relationship of Middle Bronze Age IIA Canaan to Middle Kingdom Egypt. Harvard Semitic Museum Publications. Studies in the History and Archaeology of the Levant 3. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Cohen, S. 2009. Continuities and discontinuities: a re-examination of the Intermediate Bronze Age–Middle Bronze Age Transition in Canaan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 243: 1–13.

- Cohen, S. 2012. Weaponry and warrior burials: patterns of disposal and social change in the southern Levant. In, Matthews, R. and Curtis, J. (eds), The 7th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, 12–16 April 2010: 307–19. London: The British Museum and University College London.

- Cohen, S. 2015. Periphery and core: the relationship between the southern Levant and Egypt in the early Middle Bronze Age. In, Mynářová, J., Onderka, P. and Pavúk, P. (eds), There and Back Again—the Crossroads II: Proceedings of an International Conference Held in Prague, September15–18, 2014: 245–64. Prague: Charles University.

- Cohen, S. 2016. Peripheral Concerns. Urban Development in the Bronze Age Southern Levant. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Cohen, S. 2019. Continuity, innovation, and Change: the Intermediate Bronze Age in the southern Levant. In, Cline, E., Yasur-Landau, A. and Rowan, Y. (eds), Cambridge Social Archaeology of the Eastern Mediterranean: Israel, Palestine, and Jordan: 183–198. Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press.

- Cohen, S. 2021. Diet, drink, and death: the transition from the Intermediate Bronze Age to the Middle Bronze Age in the southern Levant. In, Dever, W. G. and Long, J. (eds), Transitions, Urbanism, and Collapse in the Bronze Age. Essays in Honor of Suzanne Richard: 15–25. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Cohen, S. and Bonfil, R. 2007. Chapter 5—The pottery. In, Garfinkel, Y. and Cohen, S. (eds), The MB IIA Cemetery at Gesher: Final Report: 77–99. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 62. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Covello-Paran, K. 2009. Socio-economic aspects of an Intermediate Bronze Age village in the Jezreel Valley. In, Parr, P. (ed.), The Levant in Transition. Proceedings of a Conference Held at the British Museum on 20–21 April 2004: 9–20. Palestine Exploration Fund Annual 9. Leeds: Maney.

- D’Andrea, M. 2012. The Early Bronze IV period in south-central Transjordan. Reconsidering chronology through ceramic technology. Levant 44: 17–50.

- D’Andrea, M. 2014a. The Southern Levant in Early Bronze IV: Issues and Perspectives in the Pottery Evidence. Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale XVII. Rome: Università degli Studi di Roma La Sapienza.

- D’Andrea, M. 2014b. ‘Townships or villages?’ Remarks on the Middle Bronze IA in the southern Levant. In, Bieliński, P., Gawlikowski, M., Koliński, R., Ławecka D. Sołtysiak, A. and Wygnańska, Z. (ed), Proceedings of the 8th ICAANE, 30 April–4 May 2012, University of Warsaw. Vol. I: 151–72. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- D’Andrea, M. 2018. The EB–MB transition in the southern Levant: contacts, connectivity and transformations. In, Horejs, B. and Schwall, C. (eds), Transformation and Migration. Proceedings of the 10th International Congress on the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East, Vol. I: 81–96. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- D’Andrea, M. 2020. About stratigraphy, pottery, and relative chronology: some considerations for a refinement of the archaeological periodization of the southern Levantine Early Bronze Age IV. In, Richard, S. (ed.), New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV of the Levant: 376–416. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns.

- D’Andrea, M. 2021. Urbanism, collapse and transitions: considerations on the EB III/V and the EB IV/MB I nexuses in the southern Levant. In, Dever, W. G. and Long, J. (eds), Transitions, Urbanism, and Collapse in the Bronze Age. Essays in Honor of Suzanne Richard: 27–50. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Danin, A. 2014. Appendix IIB: vegetation. In, Dever, W. G. (ed.), Excavations at the Early Bronze IV Sites of Jebel Qa‘aqir and Be‘er Resisim: 293–97. Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant 6. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Dever, W. G. 1973. The EB IV–MB I horizon in Transjordan and southern Palestine. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 210: 37–63.

- Dever, W. G. 1987. The Middle Bronze Age: the Zenith of the urban Canaanite Era. Biblical Archaeologist 50: 149–77.

- Dever, W. G. 1992. The chronology of Syria-Palestine in the second millennium BCE: a review of current issues. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 288: 1–25.

- Dever, W. G. and Long, J. C. (eds). 2021. Transitions, Urbanism, and Collapse in the Bronze Age. Essays in Honor of Suzanne Richard. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Falconer, S. E. 1994. The development and decline of Bronze Age civilization in the southern Levant: a reassessment of urbanism and ruralism. In, Mathers, C. and Stoddart, S. (eds), Development and Decline in the Mediterranean Bronze Age: 305–33. Sheffield: J. R. Collis.

- Falconer, S. E. and Fall, P. L. 2006. Bronze Age Rural Ecology and Village Life at Tell el-Hayyat, Jordan. BAR International Series 1586. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Falconer, S. E. and Fall, P. L. 2021. EB IV settlement, chronology and society along the Jordan Rift. In, Dever, W. G. and Long, J. (eds), Transitions, Urbanism, and Collapse in the Bronze Age. Essays in Honor of Suzanne Richard: 187–200. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Falconer, S. and Magness-Gardiner, B. 1989. Bronze Age village life in the Jordan Valley: archaeological investigations at Tell el-Hayyat and Tell Abu en-Ni‘aj. National Geographic Research 5: 335–47.

- Fall, P. L. and Metzger, M. 2006. Chapter 5: economy and subsistence at Tell el-Hayyat. In, Falconer, S. E. and Fall, P. L. (eds), Bronze Age Rural Ecology and Village Life at Tell el-Hayyat, Jordan: 65–82. BAR International Series 1586. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Fall, P. L., Falconer, S. E. and Porson, S. 2019. Archaeobotanical inference of intermittent settlement and agriculture at Middle Bronze Age Zahrat adh-Dhra’1, Jordan. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 26: 1–17. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.101884>.

- Fall, P. L, Lines, L. and Falconer, S. E. 1998. Seeds of civilization: Bronze Age rural economy and ecology in the southern Levant. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 88: 107–25.

- Forsen, J. and Rowan, Y. 2010. Ground stone and small artifacts from Area C. In, Richard, S., Long, J., Holdorf, P. and Peterman, G. (eds), Khirbat Iskandar: Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C ‘Gateway’ and Cemeteries: 145–58. Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and Its Environs, Jordan, Vol. 1. American Schools of Oriental Research Archaeological Reports 14. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Garfinkel, Y. 2001. Warrior burial customs in the Levant during the early second millennium BC. In, Wolff, S. (ed.), Studies in the Archaeology of Israel and Neighboring Lands: in Memory of Douglas L. Esse: 143–61. Studies in Ancient Oriental Civilization, Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago 59. American Schools of Oriental Research 5. Chicago: Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Garfinkel, Y. and S. Cohen 2007. The burials. In, Garfinkel, Y. and Cohen, S. (eds), The Middle Bronze Age Cemetery at Gesher: Final Report: 15–68. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Gerstenblith, P. 1983. The Levant at the Beginning of the Middle Bronze Age. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series 5. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Greenberg, R. 2002. Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative, London: Leicester University.

- Greenberg, R. 2019. The Archaeology of the Bronze Age Levant. From Urban Origins to the Demise of City-States, 3700–1000 BCE. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Grosvenor Ellis, A. and Westley, B. 1965. Preliminary report on the animal remains in the Jericho tombs. In, Kenyon, K. (ed.), Excavations at Jericho II. The Tombs excavated in 1955–58: 694–701. London. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Hakker-Orion, D. 2014. The faunal remains from Be’er Resisim. In, Dever, W. G. (ed.), Excavations at the Early Bronze IV Sites of Jebel Qa’aqir and Be’er Resisim: 311–17. Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant 6. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Hausleiter, A., D’Andrea, M., and Zur, A. 2018. The transition from Early to Middle Bronze Age in northwest Arabia: bronze weapons from burial contexts at Tayma, Arabia and comparative evidence from the Levant. Zeitschrift für Orient-Archäologie 11: 412–36.

- Hellwing, S. 2000. Faunal remains. In, Kochavi, M., Beck, P. and Yadin, E. (eds), Aphek-Antipatris I. Excavation of Areas A and B. The 1972–1976 Seasons: 293–314. Monograph Series No. 19. Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Höflmayer, F. 2017. A radiocarbon chronology for the Middle Bronze Age southern Levant. Journal of Egyptian Interconnections 13: 20–33.

- Homsher, R. and Cradic, M. 2017. The Amorite problem: resolving an historical dilemma. Levant 49: 259–83.

- Horwitz, L. 2001. Animal remains from Efrata. In, Gonen, R. (ed.), Excavations at Efrata. A Burial Ground from the Intermediate and Middle Bronze Ages: 110–18. IAA Reports 12. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Horwitz, L. 2007. The faunal remains. In, Garfinkel, Y. and Cohen, S. (eds), The Excavations at the MB IIA Cemetery at Gesher: Final Report: 125–29. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 62. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Horwitz, L. 2014. Faunal remains from Jebel Qa’aqir. In, Dever, W. G. (ed.), Excavations at the Early Bronze IV Sites of Jebel Qa’aqir and Be’er Resisim: 243–48. Studies in the Archaeology and History of the Levant 6. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Horwitz, L. and Mienis, H. 2002. Archaeozoological remains. Animal bones. In, Kempinski, A. (ed.), Tel Kabri. The 1986–1993 Excavations Seasons: 395–440. Monograph Series No. 20. Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Ilan, D. 1998. The dawn of internationalism — the Middle Bronze Age. In, Levy, T. (ed.), The Archaeology of Society on the Holy Land: 297–319. London: Leicester University Press.

- Ilan, D. and Marcus, E. 2019. Middle Bronze Age IIA. In, Gitin, S. (ed.), The Ancient Pottery of Israel and Its Neighbors from the Middle Bronze Age through the Late Bronze Age: 9–75. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Kennedy, M. 2015. Assessing the Early Bronze–Middle Bronze Age transition in the southern Levant in light of a transitional ceramic vessel from Tell Umm Hammad, Jordan. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 373: 199–216.

- Kennedy, M. 2016. The end of the 3rd millennium BC in the Levant: new perspectives and old ideas. Levant 48: 1–32.

- Kennedy, M. 2020. Horizons of cultural connectivity: north–south interactions and interconnections during the Early Bronze Age IV. In, Richard, S. (ed.), New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV of the Levant: 327–46. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns.

- Kenyon, K. 1960. Excavations at Jericho. Vol. I: The Tombs Excavated in 1952–54. British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem. London: Harrison.

- Kenyon, K. 1966. Amorites and Canaanites. The Schweich Lectures of the British Academy. London: Oxford University.

- Kletter, R. and Levy, Y. 2016. Rishon Le-Zion. Vol. I. The Middle Bronze Age II Cemeteries. Volume I/2: Finds and Conclusions. Ägypten und Altes Testament 88. Münster: Zaphon.

- Langgut, D., Neumann, F. H., Stein, M., Wagner, A., Kagan, E. J., Boaretto, E. and Finkelstein, I. 2014. Dead Sea pollen record and history of human activity in the Judean Highlands (Israel) from the Intermediate Bronze into the Iron Ages (∼2500–500 BCE). Palynology 38: 280–302.

- MacDonald, B. 2021. A survey of the EB IV presence in Jordan. In, Dever, W. G. and Long, J. (eds), Transitions, Urbanism, and Collapse in the Bronze Age. Essays in Honor of Suzanne Richard: 259–72. Sheffield: Equinox.

- Maeir, A. 2007. Chapter 9 — The bone beverage strainers. In, Garfinkel, Y. and Cohen, S. (eds), The MB IIA Cemetery at Gesher: Final Report: 119–23. Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 62. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Maeir, A. 2010. In the Midst of the Jordan: The Jordan Valley during the Middle Bronze Age (circa 2000–1500 BCE). Wien: Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften.

- Marom, N. 2020. Faunal remains from the 2005–2011 seasons. In, Yasur-Landau, A. and Cline, E. (eds), Excavations at Kabri. The 2005–2011 Seasons: 277–317. Culture and History of the Ancient Near East, Volume III. Leiden: Brill.

- Mazar, A. 1990. Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000–586 BCE. New York: Doubleday.

- Metzger, M. 2010. Faunal remains from Area C. In, Richard, S., Long, J., Holdorf, P. and Peterman, G. (eds), Khirbat Iskandar: Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C ‘Gateway’ and Cemeteries: 141–43. Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and Its Environs, Jordan, Vol. 1. American Schools of Oriental Research Archaeological Reports 14. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Nigro, L. 2003. Tell es-Sultan in the Early Bronze Age IV (2300–2000) BC. Settlement vs Necropolis — a stratigraphic periodization. In, Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale IX: 121–58. Rome: Università Degli Studi di Roma «La Sapienza».

- Prag, K. 2014. The southern Levant during the Intermediate Bronze Age. In, Steiner, M. and Killebrew, A. (eds), The Archaeology of the Levant c. 8000–332 BCE: 388–400. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Regev, J., de Miroschedji, P., Greenberg, R., Braun, E., Greenhut, Z. and Boaretto, E. 2012. Chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the southern Levant: new analysis for a high chronology. Radiocarbon 54: 526–66.

- Richard, S. 2010. The Area C Early Bronze IV ceramic assemblage. In, Richard, S., Long, J., Holdorf, P. and Peterman, G. (eds), Khirbat Iskandar: Final Report on the Early Bronze IV Area C ‘Gateway’ and Cemeteries: 69–111. Archaeological Expedition to Khirbat Iskandar and its Environs, Jordan, Vol. 1. American Schools of Oriental Research Archaeological Reports 14. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research.

- Richard, S. (ed.) 2020. New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV of the Levant. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns.

- Vacca, A. and D’Andrea, M. 2020. The connections between the northern and southern Levant during Early Bronze Age III: re-evaluations and new vistas in the light of new data and higher chronologies. In, Richard, S. (ed.), New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV of the Levant: 120–45. University Park, PA: Eisenbrauns.