Appointed Director-General of the Department of Antiquities of Jordan on two occasions, Ghazi Bisheh had an indelible impact on the fields of archaeology, history, numismatics and cultural heritage as practiced in Jordan. Appreciated internationally, his enduring legacy prepared Jordan for the challenges of the 21st century by modernizing the department and broadening its purpose. He upgraded the terms and regulatory rules binding archaeological excavations, tightened export permits, encouraged local research and publication, and promoted outreach initiatives on the archaeological and cultural heritage of Jordan at home and abroad. His erudition on Jordan’s past established, beyond doubt, that the culture of the country was historically distinctive and displayed long-standing local traits as revealed in the archaeological record, thereby imbuing the department with contemporary relevance, a sense of value among staff, and greater advocacy. When faced with adversity, Ghazi was resolute in his determination and pragmatic in his responses. An intuitive reformer, critic and mentor, Ghazi was foremost a scholar of Islamic architecture, archaeology and heritage who earned an international reputation of the highest rank. At the local level and worldwide, he spearheaded the discrediting of a persistent colonial belief — still rampant in the 1980s — that Jordan after the arrival of Islam (c. 7th–11th centuries CE) became impoverished and soon abandoned, that error being upended in the 1990s with a more nuanced longue durée view on social and economic continuities in early Islamic times. By the early 21st century, the pioneering work instigated by Ghazi had radiated well beyond Jordan, deeply influencing approaches, attitudes and historical narratives in neighbouring countries and throughout the region.

Ghazi was the child of the Circassian community in ꜤAmmān, born there in 1944 and forever a citizen of that city. Following his childhood schooling, Ghazi attended Jordan University in the 1960s before undertaking a Master’s degree at the University of Michigan in the United States. He returned to Michigan for his doctoral studies under Professor Priscilla Soucek’s guidance, graduating in 1979. His subject was an architectural study on the Mosque of the Prophet at al-Madīnah, with a focus on the influential interventions under the Umayyad caliph Al-Walīd I (d. AH 96/715 CE) between AH 88–91/707–10 CE. Ghazi brought a fresh, distinctly religious perspective to the debated meaning of many new elements introduced under Al-Walīd, emphasizing their spiritual connotations. Even at this early stage, Ghazi displayed an original and questioning style of scholarship that was to guide him during the rest of his academic life — and to inspire and encourage others.

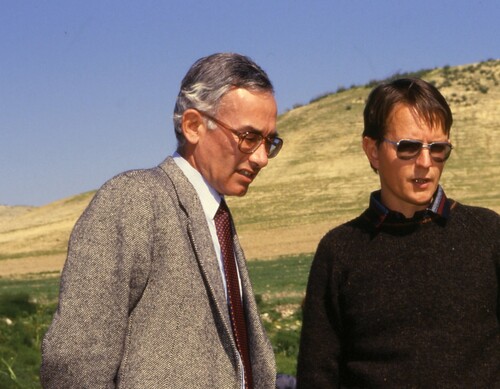

During much of the 1980s, Ghazi served as Deputy Director-General in charge of excavations at the Department of Antiquities. An onerous job, Ghazi’s trademark was visiting as many active projects as duties and time allowed; his ability to look at an excavation and pose tough questions could be daunting, although in a positive way. To this I was not immune. However, the position also allowed Ghazi to follow his own research interests into the ill-fittingly named ‘desert castles’ of the Jordanian steppe. Since the early 20th century, Western scholarship was tantamount obsessed with these enigmatic structures of early Islamic date, delivering at times fanciful if not ludicrous interpretations on why they existed and what function they served — practically and politically. Ghazi took a life-long interest in them as architectural wonders, but also looked to finding deeper meaning in their underlying purpose as aspirational mediators for the Umayyad dynasty through the spirited and eloquent socio-political messages broadcast in their imagery. As the 1980s progressed, Ghazi undertook strategic excavations and published research papers on signature sites in the steppe: Qaṣr al-Ḥallābāt, Ḥammām al-Ṣarāḥ, Qaṣr al-Mushattā, Qaṣr Mshāsh and Qaṣr ꜤAyn al-Sil, not simply as stand-alone monuments but also enhancing their significance when placed within an extended environmental, socio-economic and historic context.

Ghazi’s promotion within the Department of Antiquities just happened to coincide with the commencement of excavations by an Australian mission, co-directed by Basil Hennessy and Tony McNicoll, at Ṭabaqat Faḥl (Pella, Fiḥl) in the north Jordan Valley. I can recall excited talk in ꜤAmmān about the return of a Jordanian Islamic archaeologist, a doctoral graduate of a prestigious American university, to the Department of Antiquities. It turned out to be a decisive homecoming that promoted serious interest in the study of Jordan’s Islamic material culture, finally viewed as worthy in its own right. Unlike the desert palaces, little archaeological interest had been shown in what happened elsewhere in the 8th and later centuries in Jordan; that is, the nature of life as lived in towns, villages and the countryside. Only preliminary work had begun to address this void, such as Jim Sauer’s headlining pottery research, as part of the major excavations at Tall Ḥisbān, and the long-standing archaeological and architectural work on the Islamic-period palatial complex atop the ꜤAmmān Citadel. But change was in the air. With Ghazi’s support and enthusiasm, Islamic archaeology advanced ‘big time’ in Jordan in little more than a decade (the 1980s). Projects with a late antique to Islamic focus started up at, for example, Udhruḥ, Ṭabaqat Faḥl (Pella), Khirbat Fāris, Umm al-Raṣāṣ–Kastron Mafa‘a and Aylah (al-ꜤAqabah), while other existing projects warmed to an Islamic presence. Surveys with an active interest in Islamic settlement profiles also became a feature, such as the work of Geoffrey King and Cherie Lenzen in the bādiyah and Lenzen again with Alison McQuitty in the Irbid–Bayt Rās region. Looking back, this was not just change, nor even a transition. Rather, a transformation in purpose was taking place in Jordanian archaeology, with Ghazi at the forefront.

In part, the speed of change can be observed across the first four seasons at Ṭabaqat Faḥl (1979–82), the accelerant being the unprecedented discovery of crumpled housing units simultaneously ravaged, burying their contents both intact and shattered, in the severe earthquake of the north Jordan Valley in 749 CE. The Australian delegations of 1980 and 1982 at Ṭabaqat Faḥl were especially privileged by the appointment of Ghazi to the team. In my expanded role from 1980 as field director of the excavations, I was in daily contact with Ghazi, the student (me) observing and learning at a frenetic rate. In the 1980 winter season, one tormented by heavy rain and bitterly cold winds, Ghazi expertly excavated rooms that constituted part of a residential building later deemed ‘House G’. While the ground floor walls of cut stone remained mostly standing, the upper level of unbaked brick had fallen into the rooms below, capturing household belongings such as stylishly decorated pottery, metal vessels, stone architectural features, coins and glass, while entombing costly farm animals stabled on the ground floor along with, nearby, the ill-fated residents who owned all this. Initially destined to be removed, the contribution of these discoveries to understanding the scale and complexity of urban settlement in early Islamic Jordan resulted in a change of excavation policy in favour of retention, consolidation and presentation of the excavated houses. Furthermore, the richness of the discoveries of mid-8th century date raised another question: could it be true that Fiḥl was suddenly abandoned after the earthquake, and not reoccupied until centuries later? It seemed not. With Ghazi’s excavation of a mid-13th century mosque in the 1982 season — part of a bigger settlement — we resolved that the sole obstacle to disproving ‘abandonment’ was an absence of evidence for 9th to 11th century settlement; it just had to be found. That happened in 1985 with the excavation of a double building complex rich in objects from the 9th and 10th centuries CE.

In 1989, Ghazi was appointed Director-General of the Department of Antiquities. Almost immediately he faced an enormous challenge — war between Iraq and Kuwait. Jordan was understandably gripped by the likelihood of an all-out conflict between its opposing neighbours Iraq and Israel, with the threats of wayward scud missiles to invasion ever present. Travelling to Jordan in August of 1990 I found that, while a state of anxiety was palpable in ꜤAmmān, the Department of Antiquities was functioning close to normal, if a little feverishly. With Ghazi’s support and that of regional officers, the dig house at Ṭabaqat Faḥl, positioned only four kilometres away from Israel’s border, was secured, and it stayed that way until the return of an Australian team.

Upon ‘release’ from the Department of Antiquities in 1992, Ghazi was appointed Associate Professor at Yarmouk University and soon returned to the field as co-director on a joint Jordanian-United States heritage project commissioned to present and preserve the heart of historic Mādābā. As with football and his beloved club Al-Ahlī, Ghazi was never happier than when out in the field, conducting excavations and keeping abreast of current work. Increasingly, raising an awareness of archaeological sites as valuable cultural assets, along with fostering their social and economic role in modern Jordan became core values for Ghazi, because he saw heritage as a crucial national resource worth protecting. Initiatives were implemented to encourage local communities to engage with the past and to take cultural ownership of their heritage sites, to that end plans were devised to develop archaeological assets both tangibly and didactically, and to enhance their economic potential locally. One step in successfully implementing this goal came from Ghazi’s active involvement in the community-based organization the Friends of Archaeology.

Even with Ghazi’s surprise reappointment to the post of Director-General (1995–1999), the 1990s and 2000s were a most productive time for him. Over these two decades Ghazi produced a variety of publications. Outstanding were his contributions to the objectives of the Museum With No Frontiers, as captured in the book The Umayyads, the Rise of Islamic Art (2000), in a core chapter on the Umayyads in Discover Islamic Art in the Mediterranean (2007), and 26 authoritative entries for the ‘Discover Islamic Art’ web page (https:/islamicart.museumwnf.org/). Other publications dealt with Mādābā (notably the ‘Burnt Palace’), Qaṣr al-Ḥallābāt, the enigmatic paintings of Quṣayr ꜤAmra, Qaṣr al-Mafraq, the early minaret of al-Qasṭal, Qaṣr al-Mushattā, Ḥisbān, and Khirbat al-Mafjar. The major publications of the department — the Annual of the Department of Antiquities and Studies in the History and Archaeology of Jordan — were boosted by Ghazi’s involvement and editorial reforms. In recognition of his heritage achievements, Ghazi was appointed as Deputy Director of the International Council of Museums (Arab Countries). While his 1995 return to administrative duties was arduous, Ghazi made the most of the opportunity to increasingly emphasize the practical meaning of the inextricable and mutually beneficial connection between archaeological objectives and social responsibility. By the dawn of the new millennium, the practice and purpose of archaeology in Jordan had fundamentally diverged from its colonial origins, with Ghazi being a primary protagonist in achieving this much-needed rupture. Satisfyingly, in recent years this movement has continued its growth amongst Jordanian scholars.

Ghazi was an inspiration and a shield to many. He was generous with his time, keenly hospitable, unfailingly trustworthy and, most of all, a person of profound integrity. An attentive listener and endless in his encouragement, Ghazi was astutely aware of professional validation as a legitimizing agent in framing an Islamic archaeology for Jordan. By applying this strategy, Ghazi almost single-handedly facilitated the disposal of colonial-period paradigms that had throttled any meaningful understanding of settlement profiles and cultural identities in Jordan’s Islamic past, promoting instead fresh contemporary narratives written from the results of a new generation of surveys and excavations. The entrenched habit of mindlessly, sometimes deliberately, discarding evidence by clearing the Islamic ‘overburden’ of a site was over, resulting in the infilling of a fictitious gap in the archaeology of Jordan that continues today. Going forward, this will likely stand as Ghazi’s greatest legacy to his country and to scholarship.

I would like to thank Alison McQuitty, Barbara Porter and Khairieh ‘Amr for sharing their insights into the life and times of Ghazi, and to acknowledge the many people who communicated their admiration of Ghazi on social media platforms. Any mistakes or omissions are entirely mine.